Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Estrogen

View on Wikipedia

| Estrogen | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

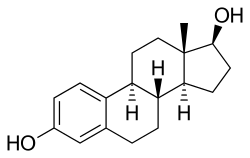

Estradiol, the major estrogen sex hormone in humans and a widely used medication | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Contraception, menopause, hypogonadism, transgender women, prostate cancer, breast cancer, others |

| ATC code | G03C |

| Biological target | Estrogen receptors (ERα, ERβ, mERs (e.g., GPER, others)) |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D004967 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Estrogen (also spelled oestrogen in British English; see spelling differences) is a category of sex hormone responsible for the development and regulation of the female reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics.[1][2] There are three major endogenous estrogens that have estrogenic hormonal activity: estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3).[1][3] Estradiol, an estrane, is the most potent and prevalent.[1] Another estrogen called estetrol (E4) is produced only during pregnancy.

Estrogens are synthesized in all vertebrates[4] and some insects.[5] Quantitatively, estrogens circulate at lower levels than androgens in both men and women.[6] While estrogen levels are significantly lower in males than in females, estrogens nevertheless have important physiological roles in males.[7]

Like all steroid hormones, estrogens readily diffuse across the cell membrane. Once inside the cell, they bind to and activate estrogen receptors (ERs) which in turn modulate the expression of many genes.[8] Additionally, estrogens bind to and activate rapid-signaling membrane estrogen receptors (mERs),[9][10] such as GPER (GPR30).[11]

In addition to their role as natural hormones, estrogens are used as medications, for instance in menopausal hormone therapy, hormonal birth control and feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women, intersex people, and nonbinary people.

Synthetic and natural estrogens have been found in the environment and are referred to as xenoestrogens. Estrogens are among the wide range of endocrine-disrupting compounds and can cause health issues and reproductive dysfunction in both wildlife and humans.[12][13]

Types and examples

[edit]The four major naturally occurring estrogens in women are estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4). Estradiol (E2) is the predominant estrogen during reproductive years both in terms of absolute serum levels as well as in terms of estrogenic activity. During menopause, estrone is the predominant circulating estrogen and during pregnancy estriol is the predominant circulating estrogen in terms of serum levels. Given by subcutaneous injection in mice, estradiol is about 10-fold more potent than estrone and about 100-fold more potent than estriol.[14] Thus, estradiol is the most important estrogen in non-pregnant females who are between the menarche and menopause stages of life. However, during pregnancy this role shifts to estriol, and in postmenopausal women estrone becomes the primary form of estrogen in the body. Another type of estrogen called estetrol (E4) is produced only during pregnancy. All of the different forms of estrogen are synthesized from androgens, specifically testosterone and androstenedione, by the enzyme aromatase.[citation needed]

Minor endogenous estrogens, the biosyntheses of which do not involve aromatase, include 27-hydroxycholesterol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), 7-oxo-DHEA, 7α-hydroxy-DHEA, 16α-hydroxy-DHEA, 7β-hydroxyepiandrosterone, androstenedione (A4), androstenediol (A5), 3α-androstanediol, and 3β-androstanediol.[15][16] Some estrogen metabolites, such as the catechol estrogens 2-hydroxyestradiol, 2-hydroxyestrone, 4-hydroxyestradiol, and 4-hydroxyestrone, as well as 16α-hydroxyestrone, are also estrogens with varying degrees of activity.[17] The biological importance of these minor estrogens is not entirely clear.

Biological function

[edit]

The actions of estrogen are mediated by the estrogen receptor (ER), a dimeric nuclear protein that binds to DNA and controls gene expression. Like other steroid hormones, estrogen enters passively into the cell where it binds to and activates the estrogen receptor. The estrogen:ER complex binds to specific DNA sequences called a hormone response element to activate the transcription of target genes (in a study using an estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell line as model, 89 such genes were identified).[19] Since estrogen enters all cells, its actions are dependent on the presence of the ER in the cell. The ER is expressed in specific tissues including the ovary, uterus and breast. The metabolic effects of estrogen in postmenopausal women have been linked to the genetic polymorphism of the ER.[20]

While estrogens are present in both men and women, they are usually present at significantly higher levels in biological females of reproductive age. They promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts, darkening and enlargement of nipples,[21] and thickening of the endometrium and other aspects of regulating the menstrual cycle. In males, estrogen regulates certain functions of the reproductive system important to the maturation of sperm[22][23][24] and may be necessary for a healthy libido.[25]

| Ligand | Other names | Relative binding affinities (RBA, %)a | Absolute binding affinities (Ki, nM)a | Action | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα | ERβ | ERα | ERβ | |||

| Estradiol | E2; 17β-Estradiol | 100 | 100 | 0.115 (0.04–0.24) | 0.15 (0.10–2.08) | Estrogen |

| Estrone | E1; 17-Ketoestradiol | 16.39 (0.7–60) | 6.5 (1.36–52) | 0.445 (0.3–1.01) | 1.75 (0.35–9.24) | Estrogen |

| Estriol | E3; 16α-OH-17β-E2 | 12.65 (4.03–56) | 26 (14.0–44.6) | 0.45 (0.35–1.4) | 0.7 (0.63–0.7) | Estrogen |

| Estetrol | E4; 15α,16α-Di-OH-17β-E2 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 19 | Estrogen |

| Alfatradiol | 17α-Estradiol | 20.5 (7–80.1) | 8.195 (2–42) | 0.2–0.52 | 0.43–1.2 | Metabolite |

| 16-Epiestriol | 16β-Hydroxy-17β-estradiol | 7.795 (4.94–63) | 50 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 17-Epiestriol | 16α-Hydroxy-17α-estradiol | 55.45 (29–103) | 79–80 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 16,17-Epiestriol | 16β-Hydroxy-17α-estradiol | 1.0 | 13 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestradiol | 2-OH-E2 | 22 (7–81) | 11–35 | 2.5 | 1.3 | Metabolite |

| 2-Methoxyestradiol | 2-MeO-E2 | 0.0027–2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Hydroxyestradiol | 4-OH-E2 | 13 (8–70) | 7–56 | 1.0 | 1.9 | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestradiol | 4-MeO-E2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestrone | 2-OH-E1 | 2.0–4.0 | 0.2–0.4 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Methoxyestrone | 2-MeO-E1 | <0.001–<1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Hydroxyestrone | 4-OH-E1 | 1.0–2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestrone | 4-MeO-E1 | <1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 16α-Hydroxyestrone | 16α-OH-E1; 17-Ketoestriol | 2.0–6.5 | 35 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 2-Hydroxyestriol | 2-OH-E3 | 2.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| 4-Methoxyestriol | 4-MeO-E3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol sulfate | E2S; Estradiol 3-sulfate | <1 | <1 | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol disulfate | Estradiol 3,17β-disulfate | 0.0004 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 3-glucuronide | E2-3G | 0.0079 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 17β-glucuronide | E2-17G | 0.0015 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estradiol 3-gluc. 17β-sulfate | E2-3G-17S | 0.0001 | ? | ? | ? | Metabolite |

| Estrone sulfate | E1S; Estrone 3-sulfate | <1 | <1 | >10 | >10 | Metabolite |

| Estradiol benzoate | EB; Estradiol 3-benzoate | 10 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Estradiol 17β-benzoate | E2-17B | 11.3 | 32.6 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Estrone methyl ether | Estrone 3-methyl ether | 0.145 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| ent-Estradiol | 1-Estradiol | 1.31–12.34 | 9.44–80.07 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Equilin | 7-Dehydroestrone | 13 (4.0–28.9) | 13.0–49 | 0.79 | 0.36 | Estrogen |

| Equilenin | 6,8-Didehydroestrone | 2.0–15 | 7.0–20 | 0.64 | 0.62 | Estrogen |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin | 7-Dehydro-17β-estradiol | 7.9–113 | 7.9–108 | 0.09 | 0.17 | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydroequilin | 7-Dehydro-17α-estradiol | 18.6 (18–41) | 14–32 | 0.24 | 0.57 | Estrogen |

| 17β-Dihydroequilenin | 6,8-Didehydro-17β-estradiol | 35–68 | 90–100 | 0.15 | 0.20 | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydroequilenin | 6,8-Didehydro-17α-estradiol | 20 | 49 | 0.50 | 0.37 | Estrogen |

| Δ8-Estradiol | 8,9-Dehydro-17β-estradiol | 68 | 72 | 0.15 | 0.25 | Estrogen |

| Δ8-Estrone | 8,9-Dehydroestrone | 19 | 32 | 0.52 | 0.57 | Estrogen |

| Ethinylestradiol | EE; 17α-Ethynyl-17β-E2 | 120.9 (68.8–480) | 44.4 (2.0–144) | 0.02–0.05 | 0.29–0.81 | Estrogen |

| Mestranol | EE 3-methyl ether | ? | 2.5 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Moxestrol | RU-2858; 11β-Methoxy-EE | 35–43 | 5–20 | 0.5 | 2.6 | Estrogen |

| Methylestradiol | 17α-Methyl-17β-estradiol | 70 | 44 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Diethylstilbestrol | DES; Stilbestrol | 129.5 (89.1–468) | 219.63 (61.2–295) | 0.04 | 0.05 | Estrogen |

| Hexestrol | Dihydrodiethylstilbestrol | 153.6 (31–302) | 60–234 | 0.06 | 0.06 | Estrogen |

| Dienestrol | Dehydrostilbestrol | 37 (20.4–223) | 56–404 | 0.05 | 0.03 | Estrogen |

| Benzestrol (B2) | – | 114 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Chlorotrianisene | TACE | 1.74 | ? | 15.30 | ? | Estrogen |

| Triphenylethylene | TPE | 0.074 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Triphenylbromoethylene | TPBE | 2.69 | ? | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Tamoxifen | ICI-46,474 | 3 (0.1–47) | 3.33 (0.28–6) | 3.4–9.69 | 2.5 | SERM |

| Afimoxifene | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen; 4-OHT | 100.1 (1.7–257) | 10 (0.98–339) | 2.3 (0.1–3.61) | 0.04–4.8 | SERM |

| Toremifene | 4-Chlorotamoxifen; 4-CT | ? | ? | 7.14–20.3 | 15.4 | SERM |

| Clomifene | MRL-41 | 25 (19.2–37.2) | 12 | 0.9 | 1.2 | SERM |

| Cyclofenil | F-6066; Sexovid | 151–152 | 243 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Nafoxidine | U-11,000A | 30.9–44 | 16 | 0.3 | 0.8 | SERM |

| Raloxifene | – | 41.2 (7.8–69) | 5.34 (0.54–16) | 0.188–0.52 | 20.2 | SERM |

| Arzoxifene | LY-353,381 | ? | ? | 0.179 | ? | SERM |

| Lasofoxifene | CP-336,156 | 10.2–166 | 19.0 | 0.229 | ? | SERM |

| Ormeloxifene | Centchroman | ? | ? | 0.313 | ? | SERM |

| Levormeloxifene | 6720-CDRI; NNC-460,020 | 1.55 | 1.88 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Ospemifene | Deaminohydroxytoremifene | 0.82–2.63 | 0.59–1.22 | ? | ? | SERM |

| Bazedoxifene | – | ? | ? | 0.053 | ? | SERM |

| Etacstil | GW-5638 | 4.30 | 11.5 | ? | ? | SERM |

| ICI-164,384 | – | 63.5 (3.70–97.7) | 166 | 0.2 | 0.08 | Antiestrogen |

| Fulvestrant | ICI-182,780 | 43.5 (9.4–325) | 21.65 (2.05–40.5) | 0.42 | 1.3 | Antiestrogen |

| Propylpyrazoletriol | PPT | 49 (10.0–89.1) | 0.12 | 0.40 | 92.8 | ERα agonist |

| 16α-LE2 | 16α-Lactone-17β-estradiol | 14.6–57 | 0.089 | 0.27 | 131 | ERα agonist |

| 16α-Iodo-E2 | 16α-Iodo-17β-estradiol | 30.2 | 2.30 | ? | ? | ERα agonist |

| Methylpiperidinopyrazole | MPP | 11 | 0.05 | ? | ? | ERα antagonist |

| Diarylpropionitrile | DPN | 0.12–0.25 | 6.6–18 | 32.4 | 1.7 | ERβ agonist |

| 8β-VE2 | 8β-Vinyl-17β-estradiol | 0.35 | 22.0–83 | 12.9 | 0.50 | ERβ agonist |

| Prinaberel | ERB-041; WAY-202,041 | 0.27 | 67–72 | ? | ? | ERβ agonist |

| ERB-196 | WAY-202,196 | ? | 180 | ? | ? | ERβ agonist |

| Erteberel | SERBA-1; LY-500,307 | ? | ? | 2.68 | 0.19 | ERβ agonist |

| SERBA-2 | – | ? | ? | 14.5 | 1.54 | ERβ agonist |

| Coumestrol | – | 9.225 (0.0117–94) | 64.125 (0.41–185) | 0.14–80.0 | 0.07–27.0 | Xenoestrogen |

| Genistein | – | 0.445 (0.0012–16) | 33.42 (0.86–87) | 2.6–126 | 0.3–12.8 | Xenoestrogen |

| Equol | – | 0.2–0.287 | 0.85 (0.10–2.85) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Daidzein | – | 0.07 (0.0018–9.3) | 0.7865 (0.04–17.1) | 2.0 | 85.3 | Xenoestrogen |

| Biochanin A | – | 0.04 (0.022–0.15) | 0.6225 (0.010–1.2) | 174 | 8.9 | Xenoestrogen |

| Kaempferol | – | 0.07 (0.029–0.10) | 2.2 (0.002–3.00) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Naringenin | – | 0.0054 (<0.001–0.01) | 0.15 (0.11–0.33) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| 8-Prenylnaringenin | 8-PN | 4.4 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Quercetin | – | <0.001–0.01 | 0.002–0.040 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Ipriflavone | – | <0.01 | <0.01 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Miroestrol | – | 0.39 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Deoxymiroestrol | – | 2.0 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| β-Sitosterol | – | <0.001–0.0875 | <0.001–0.016 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Resveratrol | – | <0.001–0.0032 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| α-Zearalenol | – | 48 (13–52.5) | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| β-Zearalenol | – | 0.6 (0.032–13) | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Zeranol | α-Zearalanol | 48–111 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Taleranol | β-Zearalanol | 16 (13–17.8) | 14 | 0.8 | 0.9 | Xenoestrogen |

| Zearalenone | ZEN | 7.68 (2.04–28) | 9.45 (2.43–31.5) | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Zearalanone | ZAN | 0.51 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Bisphenol A | BPA | 0.0315 (0.008–1.0) | 0.135 (0.002–4.23) | 195 | 35 | Xenoestrogen |

| Endosulfan | EDS | <0.001–<0.01 | <0.01 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Kepone | Chlordecone | 0.0069–0.2 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| o,p'-DDT | – | 0.0073–0.4 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| p,p'-DDT | – | 0.03 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Methoxychlor | p,p'-Dimethoxy-DDT | 0.01 (<0.001–0.02) | 0.01–0.13 | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| HPTE | Hydroxychlor; p,p'-OH-DDT | 1.2–1.7 | ? | ? | ? | Xenoestrogen |

| Testosterone | T; 4-Androstenolone | <0.0001–<0.01 | <0.002–0.040 | >5000 | >5000 | Androgen |

| Dihydrotestosterone | DHT; 5α-Androstanolone | 0.01 (<0.001–0.05) | 0.0059–0.17 | 221–>5000 | 73–1688 | Androgen |

| Nandrolone | 19-Nortestosterone; 19-NT | 0.01 | 0.23 | 765 | 53 | Androgen |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone | DHEA; Prasterone | 0.038 (<0.001–0.04) | 0.019–0.07 | 245–1053 | 163–515 | Androgen |

| 5-Androstenediol | A5; Androstenediol | 6 | 17 | 3.6 | 0.9 | Androgen |

| 4-Androstenediol | – | 0.5 | 0.6 | 23 | 19 | Androgen |

| 4-Androstenedione | A4; Androstenedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| 3α-Androstanediol | 3α-Adiol | 0.07 | 0.3 | 260 | 48 | Androgen |

| 3β-Androstanediol | 3β-Adiol | 3 | 7 | 6 | 2 | Androgen |

| Androstanedione | 5α-Androstanedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| Etiocholanedione | 5β-Androstanedione | <0.01 | <0.01 | >10000 | >10000 | Androgen |

| Methyltestosterone | 17α-Methyltestosterone | <0.0001 | ? | ? | ? | Androgen |

| Ethinyl-3α-androstanediol | 17α-Ethynyl-3α-adiol | 4.0 | <0.07 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Ethinyl-3β-androstanediol | 17α-Ethynyl-3β-adiol | 50 | 5.6 | ? | ? | Estrogen |

| Progesterone | P4; 4-Pregnenedione | <0.001–0.6 | <0.001–0.010 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Norethisterone | NET; 17α-Ethynyl-19-NT | 0.085 (0.0015–<0.1) | 0.1 (0.01–0.3) | 152 | 1084 | Progestogen |

| Norethynodrel | 5(10)-Norethisterone | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | <0.1–0.22 | 14 | 53 | Progestogen |

| Tibolone | 7α-Methylnorethynodrel | 0.5 (0.45–2.0) | 0.2–0.076 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Δ4-Tibolone | 7α-Methylnorethisterone | 0.069–<0.1 | 0.027–<0.1 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| 3α-Hydroxytibolone | – | 2.5 (1.06–5.0) | 0.6–0.8 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| 3β-Hydroxytibolone | – | 1.6 (0.75–1.9) | 0.070–0.1 | ? | ? | Progestogen |

| Footnotes: a = (1) Binding affinity values are of the format "median (range)" (# (#–#)), "range" (#–#), or "value" (#) depending on the values available. The full sets of values within the ranges can be found in the Wiki code. (2) Binding affinities were determined via displacement studies in a variety of in-vitro systems with labeled estradiol and human ERα and ERβ proteins (except the ERβ values from Kuiper et al. (1997), which are rat ERβ). Sources: See template page. | ||||||

| Estrogen | Relative binding affinities (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | AR | PR | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG | |

| Estradiol | 100 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.13 | 8.7–12 | <0.1 |

| Estradiol benzoate | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | <0.1–0.16 | <0.1 |

| Estradiol valerate | 2 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Estrone | 11–35 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 2.7 | <0.1 |

| Estrone sulfate | 2 | 2 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Estriol | 10–15 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Equilin | 40 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 0 |

| Alfatradiol | 15 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | ? | ? |

| Epiestriol | 20 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | ? | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | 100–112 | 1–3 | 15–25 | 1–3 | <1 | 0.18 | <0.1 |

| Mestranol | 1 | ? | ? | ? | ? | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Methylestradiol | 67 | 1–3 | 3–25 | 1–3 | <1 | ? | ? |

| Moxestrol | 12 | <0.1 | 0.8 | 3.2 | <0.1 | <0.2 | <0.1 |

| Diethylstilbestrol | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Notes: Reference ligands (100%) were progesterone for the PR, testosterone for the AR, estradiol for the ER, dexamethasone for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, dihydrotestosterone for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: See template. | |||||||

| Estrogen | Other names | RBA (%)a | REP (%)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | ERα | ERβ | ||||

| Estradiol | E2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Estradiol 3-sulfate | E2S; E2-3S | ? | 0.02 | 0.04 | ||

| Estradiol 3-glucuronide | E2-3G | ? | 0.02 | 0.09 | ||

| Estradiol 17β-glucuronide | E2-17G | ? | 0.002 | 0.0002 | ||

| Estradiol benzoate | EB; Estradiol 3-benzoate | 10 | 1.1 | 0.52 | ||

| Estradiol 17β-acetate | E2-17A | 31–45 | 24 | ? | ||

| Estradiol diacetate | EDA; Estradiol 3,17β-diacetate | ? | 0.79 | ? | ||

| Estradiol propionate | EP; Estradiol 17β-propionate | 19–26 | 2.6 | ? | ||

| Estradiol valerate | EV; Estradiol 17β-valerate | 2–11 | 0.04–21 | ? | ||

| Estradiol cypionate | EC; Estradiol 17β-cypionate | ?c | 4.0 | ? | ||

| Estradiol palmitate | Estradiol 17β-palmitate | 0 | ? | ? | ||

| Estradiol stearate | Estradiol 17β-stearate | 0 | ? | ? | ||

| Estrone | E1; 17-Ketoestradiol | 11 | 5.3–38 | 14 | ||

| Estrone sulfate | E1S; Estrone 3-sulfate | 2 | 0.004 | 0.002 | ||

| Estrone glucuronide | E1G; Estrone 3-glucuronide | ? | <0.001 | 0.0006 | ||

| Ethinylestradiol | EE; 17α-Ethynylestradiol | 100 | 17–150 | 129 | ||

| Mestranol | EE 3-methyl ether | 1 | 1.3–8.2 | 0.16 | ||

| Quinestrol | EE 3-cyclopentyl ether | ? | 0.37 | ? | ||

| Footnotes: a = Relative binding affinities (RBAs) were determined via in-vitro displacement of labeled estradiol from estrogen receptors (ERs) generally of rodent uterine cytosol. Estrogen esters are variably hydrolyzed into estrogens in these systems (shorter ester chain length -> greater rate of hydrolysis) and the ER RBAs of the esters decrease strongly when hydrolysis is prevented. b = Relative estrogenic potencies (REPs) were calculated from half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) that were determined via in-vitro β‐galactosidase (β-gal) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) production assays in yeast expressing human ERα and human ERβ. Both mammalian cells and yeast have the capacity to hydrolyze estrogen esters. c = The affinities of estradiol cypionate for the ERs are similar to those of estradiol valerate and estradiol benzoate (figure). Sources: See template page. | ||||||

| Estrogen | ER RBA (%) | Uterine weight (%) | Uterotrophy | LH levels (%) | SHBG RBA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | – | 100 | – | 100 | – |

| Estradiol (E2) | 100 | 506 ± 20 | +++ | 12–19 | 100 |

| Estrone (E1) | 11 ± 8 | 490 ± 22 | +++ | ? | 20 |

| Estriol (E3) | 10 ± 4 | 468 ± 30 | +++ | 8–18 | 3 |

| Estetrol (E4) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | ? | Inactive | ? | 1 |

| 17α-Estradiol | 4.2 ± 0.8 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 2-Hydroxyestradiol | 24 ± 7 | 285 ± 8 | +b | 31–61 | 28 |

| 2-Methoxyestradiol | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 101 | Inactive | ? | 130 |

| 4-Hydroxyestradiol | 45 ± 12 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 4-Methoxyestradiol | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 260 | ++ | ? | 9 |

| 4-Fluoroestradiola | 180 ± 43 | ? | +++ | ? | ? |

| 2-Hydroxyestrone | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 130 ± 9 | Inactive | 110–142 | 8 |

| 2-Methoxyestrone | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 103 ± 7 | Inactive | 95–100 | 120 |

| 4-Hydroxyestrone | 11 ± 4 | 351 | ++ | 21–50 | 35 |

| 4-Methoxyestrone | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 338 | ++ | 65–92 | 12 |

| 16α-Hydroxyestrone | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 552 ± 42 | +++ | 7–24 | <0.5 |

| 2-Hydroxyestriol | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 302 | +b | ? | ? |

| 2-Methoxyestriol | 0.01 ± 0.00 | ? | Inactive | ? | 4 |

| Notes: Values are mean ± SD or range. ER RBA = Relative binding affinity to estrogen receptors of rat uterine cytosol. Uterine weight = Percentage change in uterine wet weight of ovariectomized rats after 72 hours with continuous administration of 1 μg/hour via subcutaneously implanted osmotic pumps. LH levels = Luteinizing hormone levels relative to baseline of ovariectomized rats after 24 to 72 hours of continuous administration via subcutaneous implant. Footnotes: a = Synthetic (i.e., not endogenous). b = Atypical uterotrophic effect which plateaus within 48 hours (estradiol's uterotrophy continues linearly up to 72 hours). Sources: [26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34] | |||||

Overview of actions

[edit]- Musculoskeletal

- Anabolic: Increases muscle mass and strength, speed of muscle regeneration, and bone density, increased sensitivity to exercise, protection against muscle damage, stronger collagen synthesis, increases the collagen content of connective tissues, tendons, and ligaments, but also decreases stiffness of tendons and ligaments (especially during menstruation). Decreased stiffness of tendons gives women much lower predisposition to muscle strains but soft ligaments are much more prone to injuries (ACL tears are 2-8x more common among women than men).[35][36][37][38]

- Reduce bone resorption, increase bone formation[39][40]

- In mice, estrogen has been shown to increase the proportion of the fastest-twitch (type IIX) muscle fibers by over 40%.[41]

- Metabolic

- Anti-inflammatory properties

- Accelerate metabolism

- Gynoid fat distribution: increased fat storage or estrogenic fat in some body parts such as breasts, buttocks, and legs but decreased abdominal and visceral fat (androgenic obesity).[42][43][44]

- Estradiol also regulates energy expenditure, body weight homeostasis, and seems to have much stronger anti-obesity effects than testosterone in general.[45]

- Inhibition of ferroptosis by hydroxyoestradiol derivatives.[46]

- Other structural

- Maintenance of vessels and skin

- Protein synthesis

- Increase hepatic production of binding proteins

- Increase production of the hepatokine adropin.[47]

- Suppress the transcription of ether-lipid pathway proteins.[46]

- Coagulation

- Increase circulating level of factors 2, 7, 9, 10, plasminogen

- Decrease antithrombin III

- Increase platelet adhesiveness

- Increase vWF (estrogen -> Angiotensin II -> Vasopressin)

- Increase PAI-1 and PAI-2 also through Angiotensin II

- Lipid

- Increase HDL, triglyceride

- Decrease LDL, fat deposition

- Fluid balance

- Melanin

- Estrogen is known to cause darkening of skin, especially in the face and areolae.[50] Pale skinned women will develop browner and yellower skin during pregnancy, as a result of the increase of estrogen, known as the "mask of pregnancy".[51] Estrogen may explain why women have darker eyes than men, and also a lower risk of skin cancer than men; a European study found that women generally have darker skin than men.[52][53]

- Lung function

- Kidney function

- Protects from acute kidney injury in females.[46]

- Sexual

- Mediate formation of female secondary sex characteristics

- Stimulate endometrial growth

- Increase uterine growth

- Increase vaginal lubrication

- Thicken the vaginal wall

- Uterus lining

- Estrogen together with progesterone promotes and maintains the uterus lining in preparation for implantation of fertilized egg and maintenance of uterus function during gestation period, also upregulates oxytocin receptor in myometrium

- Ovulation

- Surge in estrogen level induces the release of luteinizing hormone, which then triggers ovulation by releasing the egg from the Graafian follicle in the ovary.

- Sexual behavior

- Estrogen is required for female mammals to engage in lordosis behavior during estrus (when animals are "in heat").[55][56] This behavior is required for sexual receptivity in these mammals and is regulated by the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus.[57]

- Sex drive is dependent on androgen levels[58] only in the presence of estrogen. Without estrogen, free testosterone level actually decreases sexual desire (instead of increasing sex drive), as demonstrated for those women who have hypoactive sexual desire disorder, and the sexual desire in these women can be restored by administration of estrogen (using oral contraceptive).[59]

Female pubertal development

[edit]Estrogens are responsible for the development of female secondary sexual characteristics during puberty, including breast development, widening of the hips, and female fat distribution. Conversely, androgens are responsible for pubic and body hair growth, as well as acne and axillary odor.

Breast development

[edit]Estrogen, in conjunction with growth hormone (GH) and its secretory product insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), is critical in mediating breast development during puberty, as well as breast maturation during pregnancy in preparation of lactation and breastfeeding.[60][61] Estrogen is primarily and directly responsible for inducing the ductal component of breast development,[62][63][64] as well as for causing fat deposition and connective tissue growth.[62][63] It is also indirectly involved in the lobuloalveolar component, by increasing progesterone receptor expression in the breasts[62][64][65] and by inducing the secretion of prolactin.[66][67] Allowed for by estrogen, progesterone and prolactin work together to complete lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy.[63][68]

Androgens such as testosterone powerfully oppose estrogen action in the breasts, such as by reducing estrogen receptor expression in them.[69][70]

Female reproductive system

[edit]Estrogens are responsible for maturation and maintenance of the vagina and uterus, and are also involved in ovarian function, such as maturation of ovarian follicles. In addition, estrogens play an important role in regulation of gonadotropin secretion. For these reasons, estrogens are required for female fertility.[citation needed]

Neuroprotection and DNA repair

[edit]Estrogen regulated DNA repair mechanisms in the brain have neuroprotective effects.[71] Estrogen regulates the transcription of DNA base excision repair genes as well as the translocation of the base excision repair enzymes between different subcellular compartments.

Brain and behavior

[edit]Sex drive

[edit]Estrogens are involved in libido (sex drive) in both women and men.

Cognition

[edit]Verbal memory scores are frequently used as one measure of higher level cognition. These scores vary in direct proportion to estrogen levels throughout the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause. Furthermore, estrogens when administered shortly after natural or surgical menopause prevents decreases in verbal memory. In contrast, estrogens have little effect on verbal memory if first administered years after menopause.[72] Estrogens also have positive influences on other measures of cognitive function.[73] However the effect of estrogens on cognition is not uniformly favorable and is dependent on the timing of the dose and the type of cognitive skill being measured.[74]

The protective effects of estrogens on cognition may be mediated by estrogen's anti-inflammatory effects in the brain.[75] Studies have also shown that the Met allele gene and level of estrogen mediates the efficiency of prefrontal cortex dependent working memory tasks.[76][77] Researchers have urged for further research to illuminate the role of estrogen and its potential for improvement on cognitive function.[78]

Mental health

[edit]Estrogen is considered to play a significant role in women's mental health. Sudden estrogen withdrawal, fluctuating estrogen, and periods of sustained low estrogen levels correlate with a significant lowering of mood. Clinical recovery from postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause depression has been shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized and/or restored.[79][80][81] Menstrual exacerbation (including menstrual psychosis) is typically triggered by low estrogen levels,[82] and is often mistaken for premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[83]

Compulsions in male lab mice, such as those in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), may be caused by low estrogen levels. When estrogen levels were raised through the increased activity of the enzyme aromatase in male lab mice, OCD rituals were dramatically decreased. Hypothalamic protein levels in the gene COMT are enhanced by increasing estrogen levels which are believed to return mice that displayed OCD rituals to normal activity. Aromatase deficiency is ultimately suspected which is involved in the synthesis of estrogen in humans and has therapeutic implications in humans having obsessive-compulsive disorder.[84]

Local application of estrogen in the rat hippocampus has been shown to inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin. Contrarily, local application of estrogen has been shown to block the ability of fluvoxamine to slow serotonin clearance, suggesting that the same pathways which are involved in SSRI efficacy may also be affected by components of local estrogen signaling pathways.[85]

Parenthood

[edit]Studies have also found that fathers had lower levels of cortisol and testosterone but higher levels of estrogen (estradiol) than did non-fathers.[86]

Binge eating

[edit]Estrogen may play a role in suppressing binge eating. Hormone replacement therapy using estrogen may be a possible treatment for binge eating behaviors in females. Estrogen replacement has been shown to suppress binge eating behaviors in female mice.[87] The mechanism by which estrogen replacement inhibits binge-like eating involves the replacement of serotonin (5-HT) neurons. Women exhibiting binge eating behaviors are found to have increased brain uptake of neuron 5-HT, and therefore less of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the cerebrospinal fluid.[88] Estrogen works to activate 5-HT neurons, leading to suppression of binge like eating behaviors.[87]

It is also suggested that there is an interaction between hormone levels and eating at different points in the female menstrual cycle. Research has predicted increased emotional eating during hormonal flux, which is characterized by high progesterone and estradiol levels that occur during the mid-luteal phase. It is hypothesized that these changes occur due to brain changes across the menstrual cycle that are likely a genomic effect of hormones. These effects produce menstrual cycle changes, which result in hormone release leading to behavioral changes, notably binge and emotional eating. These occur especially prominently among women who are genetically vulnerable to binge eating phenotypes.[89]

Binge eating is associated with decreased estradiol and increased progesterone.[90] Klump et al.[91] Progesterone may moderate the effects of low estradiol (such as during dysregulated eating behavior), but that this may only be true in women who have had clinically diagnosed binge episodes (BEs). Dysregulated eating is more strongly associated with such ovarian hormones in women with BEs than in women without BEs.[91]

The implantation of 17β-estradiol pellets in ovariectomized mice significantly reduced binge eating behaviors and injections of GLP-1 in ovariectomized mice decreased binge-eating behaviors.[87]

The associations between binge eating, menstrual-cycle phase and ovarian hormones correlated.[90][92][93]

Masculinization in rodents

[edit]In rodents, estrogens (which are locally aromatized from androgens in the brain) play an important role in psychosexual differentiation, for example, by masculinizing territorial behavior;[94] the same is not true in humans.[95] In humans, the masculinizing effects of prenatal androgens on behavior (and other tissues, with the possible exception of effects on bone) appear to act exclusively through the androgen receptor.[96] Consequently, the utility of rodent models for studying human psychosexual differentiation has been questioned.[97]

Skeletal system

[edit]Estrogens are responsible for both the pubertal growth spurt, which causes an acceleration in linear growth, and epiphyseal closure, which limits height and limb length, in both females and males. In addition, estrogens are responsible for bone maturation and maintenance of bone mineral density throughout life. Due to hypoestrogenism, the risk of osteoporosis increases during menopause.[98]

Cardiovascular system

[edit]Women are less impacted by heart disease due to vasculo-protective action of estrogen which helps in preventing atherosclerosis.[99] It also helps in maintaining the delicate balance between fighting infections and protecting arteries from damage thus lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease.[100] During pregnancy, high levels of estrogens increase coagulation and the risk of venous thromboembolism. Estrogen has been shown to upregulate the peptide hormone adropin.[47]

| Absolute incidence of first VTE per 10,000 person–years during pregnancy and the postpartum period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swedish data A | Swedish data B | English data | Danish data | |||||

| Time period | N | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate (95% CI) | NФВяы | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate (95% CI) |

| Outside pregnancy | 1105 | 4.2 (4.0–4.4) | 1015 | 3.8 (?) | 1480 | 3.2 (3.0–3.3) | 2895 | 3.6 (3.4–3.7) |

| Antepartum | 995 | 20.5 (19.2–21.8) | 690 | 14.2 (13.2–15.3) | 156 | 9.9 (8.5–11.6) | 491 | 10.7 (9.7–11.6) |

| Trimester 1 | 207 | 13.6 (11.8–15.5) | 172 | 11.3 (9.7–13.1) | 23 | 4.6 (3.1–7.0) | 61 | 4.1 (3.2–5.2) |

| Trimester 2 | 275 | 17.4 (15.4–19.6) | 178 | 11.2 (9.7–13.0) | 30 | 5.8 (4.1–8.3) | 75 | 5.7 (4.6–7.2) |

| Trimester 3 | 513 | 29.2 (26.8–31.9) | 340 | 19.4 (17.4–21.6) | 103 | 18.2 (15.0–22.1) | 355 | 19.7 (17.7–21.9) |

| Around delivery | 115 | 154.6 (128.8–185.6) | 79 | 106.1 (85.1–132.3) | 34 | 142.8 (102.0–199.8) | –

| |

| Postpartum | 649 | 42.3 (39.2–45.7) | 509 | 33.1 (30.4–36.1) | 135 | 27.4 (23.1–32.4) | 218 | 17.5 (15.3–20.0) |

| Early postpartum | 584 | 75.4 (69.6–81.8) | 460 | 59.3 (54.1–65.0) | 177 | 46.8 (39.1–56.1) | 199 | 30.4 (26.4–35.0) |

| Late postpartum | 65 | 8.5 (7.0–10.9) | 49 | 6.4 (4.9–8.5) | 18 | 7.3 (4.6–11.6) | 319 | 3.2 (1.9–5.0) |

| Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of first VTE during pregnancy and the postpartum period | ||||||||

| Swedish data A | Swedish data B | English data | Danish data | |||||

| Time period | IRR* (95% CI) | IRR* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI)† | IRR (95% CI)† | ||||

| Outside pregnancy | Reference (i.e., 1.00)

| |||||||

| Antepartum | 5.08 (4.66–5.54) | 3.80 (3.44–4.19) | 3.10 (2.63–3.66) | 2.95 (2.68–3.25) | ||||

| Trimester 1 | 3.42 (2.95–3.98) | 3.04 (2.58–3.56) | 1.46 (0.96–2.20) | 1.12 (0.86–1.45) | ||||

| Trimester 2 | 4.31 (3.78–4.93) | 3.01 (2.56–3.53) | 1.82 (1.27–2.62) | 1.58 (1.24–1.99) | ||||

| Trimester 3 | 7.14 (6.43–7.94) | 5.12 (4.53–5.80) | 5.69 (4.66–6.95) | 5.48 (4.89–6.12) | ||||

| Around delivery | 37.5 (30.9–44.45) | 27.97 (22.24–35.17) | 44.5 (31.68–62.54) | –

| ||||

| Postpartum | 10.21 (9.27–11.25) | 8.72 (7.83–9.70) | 8.54 (7.16–10.19) | 4.85 (4.21–5.57) | ||||

| Early postpartum | 19.27 (16.53–20.21) | 15.62 (14.00–17.45) | 14.61 (12.10–17.67) | 8.44 (7.27–9.75) | ||||

| Late postpartum | 2.06 (1.60–2.64) | 1.69 (1.26–2.25) | 2.29 (1.44–3.65) | 0.89 (0.53–1.39) | ||||

| Notes: Swedish data A = Using any code for VTE regardless of confirmation. Swedish data B = Using only algorithm-confirmed VTE. Early postpartum = First 6 weeks after delivery. Late postpartum = More than 6 weeks after delivery. * = Adjusted for age and calendar year. † = Unadjusted ratio calculated based on the data provided. Source: [101] | ||||||||

Immune system

[edit]The effect of estrogen on the immune system is in general described as Th2 favoring, rather than suppressive, as is the case of the effect of male sex hormone – testosterone.[102] Indeed, women respond better to vaccines, infections and are generally less likely to develop cancer, the tradeoff of this is that they are more likely to develop an autoimmune disease.[103] The Th2 shift manifests itself in a decrease of cellular immunity and increase in humoral immunity (antibody production) shifts it from cellular to humoral by downregulating cell-mediated immunity and enhancing Th2 immune response by stimulating IL-4 production and Th2 differentiation.[102][104] Type 1 and type 17 immune responses are downregulated, likely to be at least partially due to IL-4, which inhibits Th1. Effect of estrogen on different immune cells' cell types is in line with its Th2 bias. Activity of basophils, eosinophils, M2 macrophages and is enhanced, whereas activity of NK cells is downregulated. Conventional dendritic cells are biased towards Th2 under the influence of estrogen, whereas plasmacytoid dendritic cells, key players in antiviral defence, have increased IFN-g secretion.[104] Estrogen also influences B cells by increasing their survival, proliferation, differentiation and function, which corresponds with higher antibody and B cell count generally detected in women.[105]

On a molecular level estrogen induces the above-mentioned effects on cell via acting on intracellular receptors termed ER α and ER β, which upon ligation form either homo or heterodimers. The genetic and nongenetic targets of the receptors differ between homo and heterodimers.[106] Ligation of these receptors allows them to translocate to the nucleus and act as transcription factors either by binding estrogen response elements (ERE) on DNA or binding DNA together with other transcriptional factors e.g. Nf-kB or AP-1, both of which result in RNA polymerase recruitment and further chromatin remodelation.[106] A non-transcriptional response to oestrogen stimulation was also documented (termed membrane-initiated steroid signalling, MISS). This pathway stimulates the ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways, which are known to increase cellular proliferation and affect chromatin remodelation.[106]

Associated conditions

[edit]Researchers have implicated estrogens in various estrogen-dependent conditions, such as ER-positive breast cancer, as well as a number of genetic conditions involving estrogen signaling or metabolism, such as estrogen insensitivity syndrome, aromatase deficiency, and aromatase excess syndrome.[citation needed]

High estrogen can amplify stress-hormone responses in stressful situations.[107]

Biochemistry

[edit]Biosynthesis

[edit]

Estrogens, in females, are produced primarily by the ovaries, and during pregnancy, the placenta.[109] Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates the ovarian production of estrogens by the granulosa cells of the ovarian follicles and corpora lutea. Some estrogens are also produced in smaller amounts by other tissues such as the liver, pancreas, bone, adrenal glands, skin, brain, adipose tissue,[110] and the breasts.[111] These secondary sources of estrogens are especially important in postmenopausal women.[112] The pathway of estrogen biosynthesis in extragonadal tissues is different. These tissues are not able to synthesize C19 steroids, and therefore depend on C19 supplies from other tissues[112] and the level of aromatase.[113]

In females, synthesis of estrogens starts in theca interna cells in the ovary, by the synthesis of androstenedione from cholesterol. Androstenedione is a substance of weak androgenic activity which serves predominantly as a precursor for more potent androgens such as testosterone as well as estrogen. This compound crosses the basal membrane into the surrounding granulosa cells, where it is converted either immediately into estrone, or into testosterone and then estradiol in an additional step. The conversion of androstenedione to testosterone is catalyzed by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD), whereas the conversion of androstenedione and testosterone into estrone and estradiol, respectively is catalyzed by aromatase, enzymes which are both expressed in granulosa cells. In contrast, granulosa cells lack 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase, whereas theca cells express these enzymes and 17β-HSD but lack aromatase. Hence, both granulosa and theca cells are essential for the production of estrogen in the ovaries.[citation needed]

Estrogen levels vary through the menstrual cycle, with levels highest near the end of the follicular phase just before ovulation.

Note that in males, estrogen is also produced by the Sertoli cells when FSH binds to their FSH receptors.

| Sex | Sex hormone | Reproductive phase |

Blood production rate |

Gonadal secretion rate |

Metabolic clearance rate |

Reference range (serum levels) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI units | Non-SI units | ||||||

| Men | Androstenedione | –

|

2.8 mg/day | 1.6 mg/day | 2200 L/day | 2.8–7.3 nmol/L | 80–210 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | –

|

6.5 mg/day | 6.2 mg/day | 950 L/day | 6.9–34.7 nmol/L | 200–1000 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | –

|

150 μg/day | 110 μg/day | 2050 L/day | 37–250 pmol/L | 10–70 pg/mL | |

| Estradiol | –

|

60 μg/day | 50 μg/day | 1600 L/day | <37–210 pmol/L | 10–57 pg/mL | |

| Estrone sulfate | –

|

80 μg/day | Insignificant | 167 L/day | 600–2500 pmol/L | 200–900 pg/mL | |

| Women | Androstenedione | –

|

3.2 mg/day | 2.8 mg/day | 2000 L/day | 3.1–12.2 nmol/L | 89–350 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | –

|

190 μg/day | 60 μg/day | 500 L/day | 0.7–2.8 nmol/L | 20–81 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | Follicular phase | 110 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 110–400 pmol/L | 30–110 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 260 μg/day | 150 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 310–660 pmol/L | 80–180 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 40 μg/day | Insignificant | 1610 L/day | 22–230 pmol/L | 6–60 pg/mL | ||

| Estradiol | Follicular phase | 90 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 1200 L/day | <37–360 pmol/L | 10–98 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 250 μg/day | 240 μg/day | 1200 L/day | 699–1250 pmol/L | 190–341 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 6 μg/day | Insignificant | 910 L/day | <37–140 pmol/L | 10–38 pg/mL | ||

| Estrone sulfate | Follicular phase | 100 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 700–3600 pmol/L | 250–1300 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 180 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 1100–7300 pmol/L | 400–2600 pg/mL | ||

| Progesterone | Follicular phase | 2 mg/day | 1.7 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 0.3–3 nmol/L | 0.1–0.9 ng/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 25 mg/day | 24 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 19–45 nmol/L | 6–14 ng/mL | ||

Notes and sources

Notes: "The concentration of a steroid in the circulation is determined by the rate at which it is secreted from glands, the rate of metabolism of precursor or prehormones into the steroid, and the rate at which it is extracted by tissues and metabolized. The secretion rate of a steroid refers to the total secretion of the compound from a gland per unit time. Secretion rates have been assessed by sampling the venous effluent from a gland over time and subtracting out the arterial and peripheral venous hormone concentration. The metabolic clearance rate of a steroid is defined as the volume of blood that has been completely cleared of the hormone per unit time. The production rate of a steroid hormone refers to entry into the blood of the compound from all possible sources, including secretion from glands and conversion of prohormones into the steroid of interest. At steady state, the amount of hormone entering the blood from all sources will be equal to the rate at which it is being cleared (metabolic clearance rate) multiplied by blood concentration (production rate = metabolic clearance rate × concentration). If there is little contribution of prohormone metabolism to the circulating pool of steroid, then the production rate will approximate the secretion rate." Sources: See template. | |||||||

Distribution

[edit]Estrogens are plasma protein bound to albumin and/or sex hormone-binding globulin in the circulation.

Metabolism

[edit]Estrogens are metabolized via hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP1A1 and CYP3A4 and via conjugation by estrogen sulfotransferases (sulfation) and UDP-glucuronyltransferases (glucuronidation). In addition, estradiol is dehydrogenated by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase into the much less potent estrogen estrone. These reactions occur primarily in the liver, but also in other tissues.[citation needed]

Estrogen metabolism in humans

|

Excretion

[edit]Estrogens are inactivated primarily by the kidneys and liver and excreted via the gastrointestinal tract[114] in the form of conjugates, found in feces, bile, and urine.[115]

Medical use

[edit]Estrogens are used as medications, mainly in hormonal contraception, hormone replacement therapy,[116] and to treat gender dysphoria in transgender women and other transfeminine individuals as part of feminizing hormone therapy.[117]

Chemistry

[edit]The estrogen steroid hormones are estrane steroids.[citation needed]

History

[edit]In 1929, Adolf Butenandt and Edward Adelbert Doisy independently isolated and purified estrone, the first estrogen to be discovered.[118] Then, estriol and estradiol were discovered in 1930 and 1933, respectively. Shortly following their discovery, estrogens, both natural and synthetic, were introduced for medical use. Examples include estriol glucuronide (Emmenin, Progynon), estradiol benzoate, conjugated estrogens (Premarin), diethylstilbestrol, and ethinylestradiol.

The word estrogen derives from Ancient Greek. It is derived from "oestros"[119] (a periodic state of sexual activity in female mammals), and genos (generating).[119] It was first published in the early 1920s and referenced as "oestrin".[120] With the years, American English adapted the spelling of estrogen to fit with its phonetic pronunciation.

Society and culture

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The name estrogen is derived from the Greek οἶστρος (oîstros), literally meaning "verve" or "inspiration" but figuratively sexual passion or desire,[121] and the suffix -gen, meaning "producer of".

Environment

[edit]A range of synthetic and natural substances that possess estrogenic activity have been identified in the environment and are referred to xenoestrogens.[122]

- Synthetic substances such as bisphenol A as well as metalloestrogens (e.g., cadmium).

- Plant products with estrogenic activity are called phytoestrogens (e.g., coumestrol, daidzein, genistein, miroestrol).

- Those produced by fungi are known as mycoestrogens (e.g., zearalenone).

Estrogens are among the wide range of endocrine-disrupting compounds because they have high estrogenic potency. When an endocrine-disrupting compound makes its way into the environment, it may cause male reproductive dysfunction to wildlife and humans.[12][13] The estrogen excreted from farm animals makes its way into fresh water systems.[123][124] During the germination period of reproduction the fish are exposed to low levels of estrogen which may cause reproductive dysfunction to male fish.[125][126]

Cosmetics

[edit]Some hair shampoos on the market include estrogens and placental extracts; others contain phytoestrogens. In 1998, there were case reports of four prepubescent African-American girls developing breasts after exposure to these shampoos.[127] In 1993, the FDA determined that not all over-the-counter topically applied hormone-containing drug products for human use are generally recognized as safe and effective and are misbranded. An accompanying proposed rule deals with cosmetics, concluding that any use of natural estrogens in a cosmetic product makes the product an unapproved new drug and that any cosmetic using the term "hormone" in the text of its labeling or in its ingredient statement makes an implied drug claim, subjecting such a product to regulatory action.[128]

In addition to being considered misbranded drugs, products claiming to contain placental extract may also be deemed to be misbranded cosmetics if the extract has been prepared from placentas from which the hormones and other biologically active substances have been removed and the extracted substance consists principally of protein. The FDA recommends that this substance be identified by a name other than "placental extract" and describing its composition more accurately because consumers associate the name "placental extract" with a therapeutic use of some biological activity.[128]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Huether SE, McCance KL (2019). Understanding Pathophysiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 767. ISBN 978-0-32-367281-8.

Estrogen is a generic term for any of three similar hormones derived from cholesterol: estradiol, estrone, and estriol.

- ^ Satoskar RS, Rege N, Bhandarkar SD (2017). Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 943. ISBN 978-8-13-124941-3.

The natural estrogens are steroids. However, typical estrogenic activity is also shown by chemicals which are not steroids. Hence, the term 'estrogen' is used as a generic term to describe all the compounds having estrogenic activity.

- ^ Delgado BJ, Lopez-Ojeda W (20 December 2021). "Estrogen". StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30855848.

Estrogen is a steroid hormone associated with the female reproductive organs and is responsible for the development of female sexual characteristics. Estrogen is often referred to as estrone, estradiol, and estriol. ... Synthetic estrogen is also available for clinical use, designed to increase absorption and effectiveness by altering the estrogen chemical structure for topical or oral administration. Synthetic steroid estrogens include ethinyl estradiol, estradiol valerate, estropipate, conjugate esterified estrogen, and quinestrol.

- ^ Ryan KJ (August 1982). "Biochemistry of aromatase: significance to female reproductive physiology". Cancer Research. 42 (8 Suppl): 3342s – 3344s. PMID 7083198.

- ^ Mechoulam R, Brueggemeier RW, Denlinger DL (September 2005). "Estrogens in insects". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 40 (9): 942–944. doi:10.1007/BF01946450. S2CID 31950471.

- ^ Burger HG (April 2002). "Androgen production in women". Fertility and Sterility. 77 (Suppl 4): S3 – S5. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)02985-0. PMID 12007895.

- ^ Lombardi G, Zarrilli S, Colao A, Paesano L, Di Somma C, Rossi F, et al. (June 2001). "Estrogens and health in males". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 178 (1–2): 51–55. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00420-8. PMID 11403894. S2CID 36834775.

- ^ Whitehead SA, Nussey S (2001). Endocrinology: an integrated approach. Oxford: BIOS: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-85996-252-7. PMID 20821847.

- ^ Soltysik K, Czekaj P (April 2013). "Membrane estrogen receptors – is it an alternative way of estrogen action?". Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 64 (2): 129–142. PMID 23756388.

- ^ Micevych PE, Kelly MJ (2012). "Membrane estrogen receptor regulation of hypothalamic function". Neuroendocrinology. 96 (2): 103–110. doi:10.1159/000338400. PMC 3496782. PMID 22538318.

- ^ Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA (February 2007). "GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 265–266: 138–142. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. PMC 1847610. PMID 17222505.

- ^ a b Wang S, Huang W, Fang G, Zhang Y, Qiao H (2008). "Analysis of steroidal estrogen residues in food and environmental samples". International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry. 88 (1): 1–25. Bibcode:2008IJEAC..88....1W. doi:10.1080/03067310701597293. S2CID 93975613.

- ^ a b Korach KD (1998). Reproductive and developmental toxicology. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-585-15807-X. OCLC 44957536.

- ^ A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 548–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

- ^ Baker ME (March 2013). "What are the physiological estrogens?". Steroids. 78 (3): 337–340. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2012.12.011. PMID 23313336. S2CID 11803629.

- ^ Miller KK, Al-Rayyan N, Ivanova MM, Mattingly KA, Ripp SL, Klinge CM, et al. (January 2013). "DHEA metabolites activate estrogen receptors alpha and beta". Steroids. 78 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2012.10.002. PMC 3529809. PMID 23123738.

- ^ Bhavnani BR, Nisker JA, Martin J, Aletebi F, Watson L, Milne JK (2000). "Comparison of pharmacokinetics of a conjugated equine estrogen preparation (premarin) and a synthetic mixture of estrogens (C.E.S.) in postmenopausal women". Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation. 7 (3): 175–183. doi:10.1016/s1071-5576(00)00049-6. PMID 10865186.

- ^ Häggström M (2014). "Reference ranges for estradiol, progesterone, luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone during the menstrual cycle". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.001. ISSN 2002-4436.

- ^ Lin CY, Ström A, Vega VB, Kong SL, Yeo AL, Thomsen JS, et al. (2004). "Discovery of estrogen receptor alpha target genes and response elements in breast tumor cells". Genome Biology. 5 (9) R66. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r66. PMC 522873. PMID 15345050.

- ^ Darabi M, Ani M, Panjehpour M, Rabbani M, Movahedian A, Zarean E (2011). "Effect of estrogen receptor β A1730G polymorphism on ABCA1 gene expression response to postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy". Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 15 (1–2): 11–15. doi:10.1089/gtmb.2010.0106. PMID 21117950.

- ^ Lauwers J, Shinskie D (2004). Counseling the Nursing Mother: A Lactation Consultant's Guide. Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7637-2765-9. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Raloff J (6 December 1997). "Science News Online (12/6/97): Estrogen's Emerging Manly Alter Ego". Science News. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ Hess RA, Bunick D, Lee KH, Bahr J, Taylor JA, Korach KS, et al. (December 1997). "A role for oestrogens in the male reproductive system". Nature. 390 (6659): 509–512. Bibcode:1997Natur.390..509H. doi:10.1038/37352. PMC 5719867. PMID 9393999.

- ^ "Estrogen Linked To Sperm Count, Male Fertility". Science Blog. Archived from the original on 7 May 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2008.

- ^ Hill RA, Pompolo S, Jones ME, Simpson ER, Boon WC (December 2004). "Estrogen deficiency leads to apoptosis in dopaminergic neurons in the medial preoptic area and arcuate nucleus of male mice". Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 27 (4): 466–476. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2004.04.012. PMID 15555924. S2CID 25280077.

- ^ Martucci C, Fishman J (March 1976). "Uterine estrogen receptor binding of catecholestrogens and of estetrol (1,3,5(10)-estratriene-3,15alpha,16alpha,17beta-tetrol)". Steroids. 27 (3): 325–333. doi:10.1016/0039-128x(76)90054-4. PMID 178074. S2CID 54412821.

- ^ Martucci C, Fishman J (December 1977). "Direction of estradiol metabolism as a control of its hormonal action--uterotrophic activity of estradiol metabolites". Endocrinology. 101 (6): 1709–1715. doi:10.1210/endo-101-6-1709. PMID 590186.

- ^ Fishman J, Martucci C (December 1978). "Differential biological activity of estradiol metabolites". Pediatrics. 62 (6 Pt 2): 1128–1133. doi:10.1542/peds.62.6.1128. PMID 724350. S2CID 29609115.

- ^ Martucci CP, Fishman J (December 1979). "Impact of continuously administered catechol estrogens on uterine growth and luteinizing hormone secretion". Endocrinology. 105 (6): 1288–1292. doi:10.1210/endo-105-6-1288. PMID 499073.

- ^ Fishman J, Martucci CP (1980). "New Concepts of Estrogenic Activity: the Role of Metabolites in the Expression of Hormone Action". In Pasetto N, Paoletti R, Ambrus JL (eds.). The Menopause and Postmenopause. pp. 43–52. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-7230-1_5. ISBN 978-94-011-7232-5.

- ^ Fishman J, Martucci C (September 1980). "Biological properties of 16 alpha-hydroxyestrone: implications in estrogen physiology and pathophysiology". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 51 (3): 611–615. doi:10.1210/jcem-51-3-611. PMID 7190977.

- ^ Martucci CP (July 1983). "The role of 2-methoxyestrone in estrogen action". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 19 (1B): 635–638. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(83)90229-7. PMID 6310247.

- ^ Fishman J, Martucci C (1980). "Dissociation of biological activities in metabolites of estradiol". In McLachlan JA (ed.). Estrogens in the Environment: Proceedings of the Symposium on Estrogens in the Environment, Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S.A., September 10-12, 1979. Elsevier. pp. 131–145. ISBN 9780444003720.

- ^ Kuhl H (August 2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324.

- ^ Chidi-Ogbolu N, Baar K (2018). "Effect of Estrogen on Musculoskeletal Performance and Injury Risk". Frontiers in Physiology. 9 1834. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01834. PMC 6341375. PMID 30697162.

- ^ Lowe DA, Baltgalvis KA, Greising SM (April 2010). "Mechanisms behind estrogen's beneficial effect on muscle strength in females". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 38 (2): 61–67. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181d496bc. PMC 2873087. PMID 20335737.

- ^ Max SR (December 1984). "Androgen-estrogen synergy in rat levator ani muscle: glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 38 (2–3): 103–107. doi:10.1016/0303-7207(84)90108-4. PMID 6510548. S2CID 24198956.

- ^ Koot RW, Amelink GJ, Blankenstein MA, Bär PR (1991). "Tamoxifen and oestrogen both protect the rat muscle against physiological damage". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 40 (4–6): 689–695. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(91)90292-d. PMID 1958566. S2CID 44446541.

- ^ Gavali S, Gupta MK, Daswani B, Wani MR, Sirdeshmukh R, Khatkhatay MI (2019). "LYN, a key mediator in estrogen-dependent suppression of osteoclast differentiation, survival, and function". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1865 (3): 547–557. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.12.016. PMID 30579930.

- ^ Gavali S, Gupta MK, Daswani B, Wani MR, Sirdeshmukh R, Khatkhatay MI (2019). "Estrogen enhances human osteoblast survival and function via promotion of autophagy". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1866 (9): 1498–1507. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.06.014. PMID 31255720.

- ^ Haizlip KM, Harrison BC, Leinwand LA (January 2015). "Sex-based differences in skeletal muscle kinetics and fiber-type composition". Physiology. 30 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1152/physiol.00024.2014. PMC 4285578. PMID 25559153. "Supplementation with estrogen increases the type-IIX percentage composition in the plantaris back to 42%. (70)"

- ^ Frank AP, de Souza Santos R, Palmer BF, Clegg DJ (October 2019). "Determinants of body fat distribution in humans may provide insight about obesity-related health risks". Journal of Lipid Research. 60 (10): 1710–1719. doi:10.1194/jlr.R086975. PMC 6795075. PMID 30097511.

- ^ Brown LM, Gent L, Davis K, Clegg DJ (September 2010). "Metabolic impact of sex hormones on obesity". Brain Research. 1350: 77–85. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.056. PMC 2924463. PMID 20441773.

- ^ Janssen I, Powell LH, Kazlauskaite R, Dugan SA (March 2010). "Testosterone and visceral fat in midlife women: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) fat patterning study". Obesity. 18 (3): 604–610. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.251. PMC 2866448. PMID 19696765.

- ^ Rubinow KB (2017). "Estrogens and Body Weight Regulation in Men". Sex and Gender Factors Affecting Metabolic Homeostasis, Diabetes and Obesity. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1043. Springer. pp. 285–313. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_14. ISBN 978-3-319-70177-6. PMC 5835337. PMID 29224100.

- ^ a b c Tonnus W, Maremonti F, Gavali S, Schlecht MN, Gembardt F, Belavgeni A, et al. (September 2025). "Multiple oestradiol functions inhibit ferroptosis and acute kidney injury". Nature. 645 (8082): 1011–1019. Bibcode:2025Natur.645.1011T. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09389-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 12460175. PMID 40804518.

- ^ a b Stokar J, Gurt I, Cohen-Kfir E, Yakubovsky O, Hallak N, Benyamini H, et al. (June 2022). "Hepatic adropin is regulated by estrogen and contributes to adverse metabolic phenotypes in ovariectomized mice". Molecular Metabolism. 60 101482. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101482. PMC 9044006. PMID 35364299.

- ^ Frysh P. "Reasons Why Your Face Looks Swollen". WebMD.

- ^ Stachenfeld NS (July 2008). "Sex hormone effects on body fluid regulation". Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 36 (3): 152–159. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e31817be928. PMC 2849969. PMID 18580296.

- ^ Pawlina W (2023). Histology: A Text and Atlas: With Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology. Wolters Kluwer Health. p. 1481. ISBN 978-1-9751-8152-9. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Greenberg J, Bruess C, Oswalt S (2014). "Conception, Pregnancy, and Birth". Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-4496-4851-0. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Researchers discover genetic causes of higher melanoma risk in men". ScienceDaily.

- ^ Hernando B, Ibarrola-Villava M, Fernandez LP, Peña-Chilet M, Llorca-Cardeñosa M, Oltra SS, et al. (18 March 2016). "Sex-specific genetic effects associated with pigmentation, sensitivity to sunlight, and melanoma in a population of Spanish origin". Biology of Sex Differences. 7 (1) 17. doi:10.1186/s13293-016-0070-1. PMC 4797181. PMID 26998216. "The results of this study suggest that there are indeed sex-specific genetic effects in human pigmentation, with larger effects for darker pigmentation in females compared to males. A plausible cause might be the differentially expressed melanogenic genes in females due to higher oestrogen levels. These sex-specific genetic effects would help explain the presence of darker eye and skin pigmentation in females, as well as the well-known higher melanoma risk displayed by males."

- ^ Massaro D, Massaro GD (December 2004). "Estrogen regulates pulmonary alveolar formation, loss, and regeneration in mice" (PDF). American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 287 (6): L1154 – L1159. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00228.2004. PMID 15298854. S2CID 24642944. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2019.

- ^ Christensen A, Bentley GE, Cabrera R, Ortega HH, Perfito N, Wu TJ, et al. (July 2012). "Hormonal regulation of female reproduction". Hormone and Metabolic Research. 44 (8): 587–591. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1306301. PMC 3647363. PMID 22438212.

- ^ Handa RJ, Ogawa S, Wang JM, Herbison AE (January 2012). "Roles for oestrogen receptor β in adult brain function". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 24 (1): 160–173. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02206.x. PMC 3348521. PMID 21851428.

- ^ Kow LM, Pfaff DW (May 1998). "Mapping of neural and signal transduction pathways for lordosis in the search for estrogen actions on the central nervous system". Behavioural Brain Research. 92 (2): 169–180. doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(97)00189-7. PMID 9638959. S2CID 28276218.

- ^ Warnock JK, Swanson SG, Borel RW, Zipfel LM, Brennan JJ (2005). "Combined esterified estrogens and methyltestosterone versus esterified estrogens alone in the treatment of loss of sexual interest in surgically menopausal women". Menopause. 12 (4): 374–384. doi:10.1097/01.GME.0000153933.50860.FD. PMID 16037752. S2CID 24557071.

- ^ Heiman JR, Rupp H, Janssen E, Newhouse SK, Brauer M, Laan E (May 2011). "Sexual desire, sexual arousal and hormonal differences in premenopausal US and Dutch women with and without low sexual desire". Hormones and Behavior. 59 (5): 772–779. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.03.013. PMID 21514299. S2CID 20807391.

- ^ Brisken C, O'Malley B (December 2010). "Hormone action in the mammary gland". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (12) a003178. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003178. PMC 2982168. PMID 20739412.

- ^ Kleinberg DL (February 1998). "Role of IGF-I in normal mammary development". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 47 (3): 201–208. doi:10.1023/a:1005998832636. PMID 9516076. S2CID 30440069.

- ^ a b c Johnson LR (2003). Essential Medical Physiology. Academic Press. p. 770. ISBN 978-0-12-387584-6.

- ^ a b c Norman AW, Henry HL (30 July 2014). Hormones. Academic Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-08-091906-5.

- ^ a b Coad J, Dunstall M (2011). Anatomy and Physiology for Midwives, with Pageburst online access,3: Anatomy and Physiology for Midwives. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-7020-3489-3.

- ^ Haslam SZ, Osuch JR (1 January 2006). Hormones and Breast Cancer in Post-Menopausal Women. IOS Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-58603-653-9.

- ^ Silbernagl S, Despopoulos A (1 January 2011). Color Atlas of Physiology. Thieme. pp. 305–. ISBN 978-3-13-149521-1.

- ^ Fadem B (2007). High-yield Comprehensive USMLE Step 1 Review. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 445–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7427-7.

- ^ Blackburn S (14 April 2014). Maternal, Fetal, & Neonatal Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-323-29296-2.

- ^ Strauss JF, Barbieri RL (13 September 2013). Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-1-4557-2758-2.

- ^ Wilson CB, Nizet V, Maldonado Y, Remington JS, Klein JO (24 February 2015). Remington and Klein's Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-0-323-24147-2.

- ^ Zárate S, Stevnsner T, Gredilla R (2017). "Role of Estrogen and Other Sex Hormones in Brain Aging. Neuroprotection and DNA Repair". Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 9 430. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2017.00430. PMC 5743731. PMID 29311911.

- ^ Sherwin BB (February 2012). "Estrogen and cognitive functioning in women: lessons we have learned". Behavioral Neuroscience. 126 (1): 123–127. doi:10.1037/a0025539. PMC 4838456. PMID 22004260.

- ^ Hara Y, Waters EM, McEwen BS, Morrison JH (July 2015). "Estrogen Effects on Cognitive and Synaptic Health Over the Lifecourse". Physiological Reviews. 95 (3): 785–807. doi:10.1152/physrev.00036.2014. PMC 4491541. PMID 26109339.

- ^ Korol DL, Pisani SL (August 2015). "Estrogens and cognition: Friends or foes?: An evaluation of the opposing effects of estrogens on learning and memory". Hormones and Behavior. 74: 105–115. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.06.017. PMC 4573330. PMID 26149525.

- ^ Au A, Feher A, McPhee L, Jessa A, Oh S, Einstein G (January 2016). "Estrogens, inflammation and cognition". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 40: 87–100. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2016.01.002. PMID 26774208.

- ^ Jacobs E, D'Esposito M (April 2011). "Estrogen shapes dopamine-dependent cognitive processes: implications for women's health". The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (14): 5286–5293. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6394-10.2011. PMC 3089976. PMID 21471363.

- ^ Colzato LS, Hommel B (1 January 2014). "Effects of estrogen on higher-order cognitive functions in unstressed human females may depend on individual variation in dopamine baseline levels". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 8: 65. doi:10.3389/fnins.2014.00065. PMC 3985021. PMID 24778605.

- ^ Hogervorst E (March 2013). "Estrogen and the brain: does estrogen treatment improve cognitive function?". Menopause International. 19 (1): 6–19. doi:10.1177/1754045312473873. PMID 27951525. S2CID 10122688.

- ^ Douma SL, Husband C, O'Donnell ME, Barwin BN, Woodend AK (2005). "Estrogen-related mood disorders: reproductive life cycle factors". ANS. Advances in Nursing Science. 28 (4): 364–375. doi:10.1097/00012272-200510000-00008. PMID 16292022. S2CID 9172877.

- ^ Osterlund MK, Witt MR, Gustafsson JA (December 2005). "Estrogen action in mood and neurodegenerative disorders: estrogenic compounds with selective properties-the next generation of therapeutics". Endocrine. 28 (3): 235–242. doi:10.1385/ENDO:28:3:235. PMID 16388113. S2CID 8205014.

- ^ Lasiuk GC, Hegadoren KM (October 2007). "The effects of estradiol on central serotonergic systems and its relationship to mood in women". Biological Research for Nursing. 9 (2): 147–160. doi:10.1177/1099800407305600. PMID 17909167. S2CID 37965502.

- ^ Grigoriadis S, Seeman MV (June 2002). "The role of estrogen in schizophrenia: implications for schizophrenia practice guidelines for women". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 47 (5): 437–442. doi:10.1177/070674370204700504. PMID 12085678.

- ^ "PMDD/PMS". The Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women's Mental Health. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Hill RA, McInnes KJ, Gong EC, Jones ME, Simpson ER, Boon WC (February 2007). "Estrogen deficient male mice develop compulsive behavior". Biological Psychiatry. 61 (3): 359–366. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.012. PMID 16566897. S2CID 22669945.

- ^ Benmansour S, Weaver RS, Barton AK, Adeniji OS, Frazer A (April 2012). "Comparison of the effects of estradiol and progesterone on serotonergic function". Biological Psychiatry. 71 (7): 633–641. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.023. PMC 3307822. PMID 22225849.

- ^ Berg SJ, Wynne-Edwards KE (June 2001). "Changes in testosterone, cortisol, and estradiol levels in men becoming fathers". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 76 (6): 582–592. doi:10.4065/76.6.582. PMID 11393496.

- ^ a b c Cao X, Xu P, Oyola MG, Xia Y, Yan X, Saito K, et al. (October 2014). "Estrogens stimulate serotonin neurons to inhibit binge-like eating in mice". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (10): 4351–4362. doi:10.1172/JCI74726. PMC 4191033. PMID 25157819.

- ^ Jimerson DC, Lesem MD, Kaye WH, Hegg AP, Brewerton TD (September 1990). "Eating disorders and depression: is there a serotonin connection?". Biological Psychiatry. 28 (5): 443–454. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(90)90412-u. PMID 2207221. S2CID 31058047.

- ^ Klump KL, Keel PK, Racine SE, Burt SA, Burt AS, Neale M, et al. (February 2013). "The interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on changes in emotional eating across the menstrual cycle". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 122 (1): 131–137. doi:10.1037/a0029524. PMC 3570621. PMID 22889242.

- ^ a b Edler C, Lipson SF, Keel PK (January 2007). "Ovarian hormones and binge eating in bulimia nervosa". Psychological Medicine. 37 (1): 131–141. doi:10.1017/S0033291706008956. PMID 17038206. S2CID 36609028.

- ^ a b Klump KL, Racine SE, Hildebrandt B, Burt SA, Neale M, Sisk CL, et al. (September 2014). "Ovarian Hormone Influences on Dysregulated Eating: A Comparison of Associations in Women with versus without Binge Episodes". Clinical Psychological Science. 2 (4): 545–559. doi:10.1177/2167702614521794. PMC 4203460. PMID 25343062.

- ^ Klump KL, Keel PK, Culbert KM, Edler C (December 2008). "Ovarian hormones and binge eating: exploring associations in community samples". Psychological Medicine. 38 (12): 1749–1757. doi:10.1017/S0033291708002997. PMC 2885896. PMID 18307829.

- ^ Lester NA, Keel PK, Lipson SF (January 2003). "Symptom fluctuation in bulimia nervosa: relation to menstrual-cycle phase and cortisol levels". Psychological Medicine. 33 (1): 51–60. doi:10.1017/s0033291702006815. PMID 12537036. S2CID 21497515.

- ^ Wu MV, Manoli DS, Fraser EJ, Coats JK, Tollkuhn J, Honda S, et al. (October 2009). "Estrogen masculinizes neural pathways and sex-specific behaviors". Cell. 139 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.036. PMC 2851224. PMID 19804754.

- ^ Rochira V, Carani C (October 2009). "Aromatase deficiency in men: a clinical perspective". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 5 (10): 559–568. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2009.176. hdl:11380/619320. PMID 19707181. S2CID 22116130.

- ^ Wilson JD (September 2001). "Androgens, androgen receptors, and male gender role behavior" (PDF). Hormones and Behavior. 40 (2): 358–366. doi:10.1006/hbeh.2001.1684. PMID 11534997. S2CID 20480423. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2019.

- ^ Baum MJ (November 2006). "Mammalian animal models of psychosexual differentiation: when is 'translation' to the human situation possible?". Hormones and Behavior. 50 (4): 579–588. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.003. PMID 16876166. S2CID 7465192.

- ^ Cheng CH, Chen LR, Chen KH (25 January 2022). "Osteoporosis Due to Hormone Imbalance: An Overview of the Effects of Estrogen Deficiency and Glucocorticoid Overuse on Bone Turnover". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (3): 1376. doi:10.3390/ijms23031376. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8836058. PMID 35163300.

- ^ Rosano GM, Panina G (1999). "Oestrogens and the heart". Therapie. 54 (3): 381–385. PMID 10500455.

- ^ Nadkarni S, Cooper D, Brancaleone V, Bena S, Perretti M (November 2011). "Activation of the annexin A1 pathway underlies the protective effects exerted by estrogen in polymorphonuclear leukocytes". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 31 (11): 2749–2759. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.235176. PMC 3357483. PMID 21836070.

- ^ Abdul Sultan A, West J, Stephansson O, Grainge MJ, Tata LJ, Fleming KM, et al. (November 2015). "Defining venous thromboembolism and measuring its incidence using Swedish health registries: a nationwide pregnancy cohort study". BMJ Open. 5 (11) e008864. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008864. PMC 4654387. PMID 26560059.

- ^ a b Foo YZ, Nakagawa S, Rhodes G, Simmons LW (February 2017). "The effects of sex hormones on immune function: a meta-analysis" (PDF). Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 92 (1): 551–571. doi:10.1111/brv.12243. PMID 26800512. S2CID 37931012.

- ^ Taneja V (27 August 2018). "Sex Hormones Determine Immune Response". Frontiers in Immunology. 9 1931. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01931. PMC 6119719. PMID 30210492.

- ^ a b Roved J, Westerdahl H, Hasselquist D (February 2017). "Sex differences in immune responses: Hormonal effects, antagonistic selection, and evolutionary consequences". Hormones and Behavior. 88: 95–105. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.11.017. PMID 27956226. S2CID 9137227.

- ^ Khan D, Ansar Ahmed S (6 January 2016). "The Immune System Is a Natural Target for Estrogen Action: Opposing Effects of Estrogen in Two Prototypical Autoimmune Diseases". Frontiers in Immunology. 6: 635. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00635. PMC 4701921. PMID 26779182.

- ^ a b c Kovats S (April 2015). "Estrogen receptors regulate innate immune cells and signaling pathways". Cellular Immunology. 294 (2): 63–69. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.01.018. PMC 4380804. PMID 25682174.

- ^

Prior JC (2018). Estrogen's Storm Season: stories of perimenopause. Vancouver, British Columbia: CeMCOR (Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research). ISBN 978-0-9738275-2-1. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

[...] high estrogen amplifies your stress hormone responses to stressful things [...]

- ^ Häggström M, Richfield D (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 2002-4436.

- ^ Marieb E (2013). Anatomy & physiology. Benjamin-Cummings. p. 903. ISBN 978-0-321-88760-3.

- ^ Hemsell DL, Grodin JM, Brenner PF, Siiteri PK, MacDonald PC (March 1974). "Plasma precursors of estrogen. II. Correlation of the extent of conversion of plasma androstenedione to estrone with age". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 38 (3): 476–479. doi:10.1210/jcem-38-3-476. PMID 4815174.

- ^ Barakat R, Oakley O, Kim H, Jin J, Ko CJ (September 2016). "Extra-gonadal sites of estrogen biosynthesis and function". BMB Reports. 49 (9): 488–496. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.9.141. PMC 5227141. PMID 27530684.

- ^ a b Nelson LR, Bulun SE (September 2001). "Estrogen production and action". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 45 (3 Suppl): S116 – S124. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117432. PMID 11511861.

- ^ Labrie F, Bélanger A, Luu-The V, Labrie C, Simard J, Cusan L, et al. (1998). "DHEA and the intracrine formation of androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: its role during aging". Steroids. 63 (5–6): 322–328. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(98)00007-5. PMID 9618795. S2CID 37344052.

- ^ Schreinder WE (2012). "The Ovary". In Trachsler A, Thorn G, Labhart A, Bürgi H, Dodsworth-Phillips J, Constam G, Courvoisier B, Fischer JA, Froesch ER, Grob P (eds.). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 530. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Fuentes N, Silveyra P (2019). "Estrogen receptor signaling mechanisms". Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. Vol. 116. Elsevier. pp. 135–170. doi:10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.01.001. ISBN 978-0-12-815561-5. ISSN 1876-1623. PMC 6533072. PMID 31036290.

Physiologically, the metabolic conversion of estrogens allows their excretion from the body via urine, feces, and/or bile, along with the production of estrogen analogs, which have been shown to present antiproliferative effects (Tsuchiya et al., 2005).

- ^ Kuhl H (August 2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 (Suppl 1): 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324.

- ^ Wesp LM, Deutsch MB (March 2017). "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 40 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- ^ Tata JR (June 2005). "One hundred years of hormones". EMBO Reports. 6 (6): 490–496. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400444. PMC 1369102. PMID 15940278.

- ^ a b "Origin in Biomedical Terms: oestrogen or oestrogen". Bioetymology. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry". Journal of the American Medical Association. 107 (15): 1221–3. 1936. doi:10.1001/jama.1936.02770410043011.