Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Germans

View on Wikipedia

Germans (German: Deutsche) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language.[1][2] The constitution of Germany, implemented in 1949 following the end of World War II, defines a German as a German citizen.[3] During the 19th and much of the 20th century, discussions on German identity were dominated by concepts of a common language, culture, descent, and history.[4] Today, the German language is widely seen as the primary, though not exclusive, criterion of German identity.[5] Estimates on the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 to 150 million, most of whom live in Germany.[6]

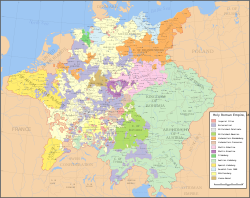

The history of Germans as an ethnic group began with the separation of a distinct Kingdom of Germany from the eastern part of the Frankish Empire under the Ottonian dynasty in the 10th century, forming the core of the Holy Roman Empire. In subsequent centuries the political power and population of this empire grew considerably. It expanded eastwards, and eventually a substantial number of Germans migrated further eastwards into Eastern Europe. The empire itself was generally decentralized and politically divided between many small princedoms, cities and bishoprics, while the idea of unified German state came later. Following the Reformation in the 16th century, many of these states found themselves in bitter conflict concerning the rise of Protestantism.

In the 19th century, the Holy Roman Empire dissolved, and German nationalism began to grow. At the same time however, the concept of German nationality became more complex. The multiethnic Kingdom of Prussia incorporated most Germans into its German Empire in 1871, and a substantial additional number of German speakers were in the multiethnic kingdom of Austria-Hungary. During this time, a large number of Germans also emigrated to the New World, particularly to the United States. Large numbers also emigrated to Canada and Brazil, and they established sizable communities in New Zealand and Australia. The Russian Empire also included a substantial German population.

Following the end of World War I, Austria-Hungary and the German Empire were partitioned, resulting in many Germans becoming ethnic minorities in newly established countries. In the chaotic years that followed, Adolf Hitler became the dictator of Nazi Germany and embarked on a genocidal campaign to unify all Germans under his leadership. His Nazi movement defined Germans in a very specific way which included Austrians, Luxembourgers, eastern Belgians, and so-called Volksdeutsche, who were ethnic Germans elsewhere in Europe and globally. However, this Nazi conception expressly excluded German citizens of Jewish or Roma background. Nazi policies of military aggression and its persecution of those deemed non-Germans led to World War II and the Holocaust in which the Nazi regime was defeated by allied powers, including the United States, United Kingdom, and the former Soviet Union. In the aftermath of Germany's defeat in the war, the country was occupied and once again partitioned. Millions of Germans were expelled from Central and Eastern Europe. In 1990, West Germany and East Germany were reunified. In modern times, remembrance of the Holocaust, known as Erinnerungskultur ("culture of remembrance"), has become an integral part of German identity.

Owing to their long history of political fragmentation, Germans are culturally diverse and often have strong regional identities. Sixteen Länder (states) make up modern Germany. Arts and sciences are an integral part of German culture, and the Germans have been represented by many prominent personalities in a significant number of disciplines, including Nobel prize laureates where Germany is ranked third among countries of the world in the number of total recipients.

Names

[edit]The English term Germans is derived from the ethnonym Germani, which was used for Germanic peoples in ancient times.[7][8] Since the early modern period, it has been the most common name for the Germans in English, being applied to any citizens, natives or inhabitants of Germany, regardless of whether they are considered to have German ethnicity.

In some contexts, people of German descent are also called Germans.[2][1] In historical discussions the term "Germans" is also occasionally used to refer to the Germanic peoples during the time of the Roman Empire.[1][9][10]

The German endonym Deutsche is derived from the Old High German term diutisc, which means "ethnic" or "relating to the people". This term was used for speakers of West-Germanic languages in Central Europe since at least the 8th century, after which time a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge among at least some them living within the Holy Roman Empire.[7] However, variants of the same term were also used in the Low Countries, for the related dialects of what is still called Dutch in English, which is now a national language of the Netherlands and Belgium.

History

[edit]

Ancient history

[edit]

The first information about the peoples living in what is now Germany was provided by the Roman general and dictator Julius Caesar, who gave an account of his conquest of Gaul in the 1st century BC. He used the term Germani to describe the Germanic peoples living on both sides of the Rhine river, which he defined as a boundary between geographical Gaul and Germania. He emphasized that the Germani originated east of the river, and that this river border needed to be defended in order to avoid dangerous incursions. Archaeological evidence shows that at the time of Caesar's invasion, both Gaul and Germanic regions had long been strongly influenced by the same celtic La Tène culture.[11] However, the Germanic languages associated with later Germanic peoples are indeed believed to have been entering the Rhine area from the east in this period.[12] The resulting demographic situation reported by Caesar was that migrating Celts and Germanic peoples were moving into areas which threatened the Alpine regions and the Romans.[11]

The modern German language is a descendant of the Germanic languages which spread during the Iron Age and Roman era. Scholars generally agree that it is possible to speak of Germanic languages existing as early as 500 BCE.[13] These Germanic languages are believed to have dispersed towards the Rhine from the direction of the Jastorf culture, which was itself a Celtic influenced culture that existed in the Pre-Roman Iron Age, in the region near the Elbe river. It is likely that first Germanic consonant shift, which defines the Germanic language family, occurred during this period.[14] The earlier Nordic Bronze Age of southern Scandinavia also shows definite population and material continuities with the Jastorf Culture,[15] but it is unclear whether these indicate ethnic continuity.[16]

Under Caesar's successors, the Romans began to conquer and control the entire region between the Rhine and the Elbe which centuries later constituted the largest part of medieval Germany. These efforts were significantly hampered by the victory of a local alliance led by Arminius at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, which is considered a defining moment in German history. While the Romans were nevertheless victorious, rather than installing a Roman administration they controlled the region indirectly for centuries, recruiting soldiers there, and playing the tribes off against each other.[11][17] The early Germanic peoples were later famously described in more detail in Germania by the 1st century Roman historian Tacitus. He described them as a diverse group, dominating a much larger area than Germany, stretching to the Vistula in the east, and Scandinavia in the north.

Medieval history

[edit]

German ethnicity began to emerge in medieval times among the descendants of those Germanic peoples who had lived under heavy Roman influence between the Rhine and Elbe rivers. This included Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringii, Alemanni and Baiuvarii – all of whom spoke related dialects of West Germanic.[11] These peoples had come under the dominance of the western Franks starting with Clovis I, who established control of the Romanized and Frankish population of Gaul in the 5th century, and began a process of conquering the peoples east of the Rhine. The regions long continued to be divided into "Stem duchies", corresponding to the old ethnic designations.[12] By the early 9th century AD, large parts of Europe were united under the rule of the Frankish leader Charlemagne, who expanded the Frankish empire in several directions including east of the Rhine, consolidating power over the Saxons and Frisians, and establishing the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III in 800.[12]

In the generations after Charlemagne the empire was partitioned at the Treaty of Verdun (843), eventually resulting in the long-term separation between the states of West Francia, Middle Francia and East Francia. Beginning with Henry the Fowler, non-Frankish dynasties also ruled the eastern kingdom, and under his son Otto I, East Francia, which was mostly German, constituted the core of the Holy Roman Empire.[18] Also under control of this loosely controlled empire were the previously independent kingdoms of Italy, Burgundy, and Lotharingia. The latter was a Roman and Frankish area which contained some of the oldest and most important old German cities including Aachen, Cologne and Trier, all west of the Rhine, and it became another Duchy within the eastern kingdom. Leaders of the stem duchies which constituted this eastern kingdom — Lotharingia, Bavaria, Franconia, Swabia, Thuringia, and Saxony ― initially wielded considerable power independently of the king.[12] German kings were elected by members of the noble families, who often sought to have weak kings elected in order to preserve their own independence. This prevented an early unification of the Germans.[19][20]

A warrior nobility dominated the feudal German society of the Middle Ages, while most of the German population consisted of peasants with few political rights.[12] The church played an important role in the Holy Roman Empire in the Middle Ages, and competed with the nobility for power.[21] Between the 11th and 13th centuries, German speakers from the empire actively participated in five Crusades to "liberate" the Holy Land.[21] From the beginnings of the kingdom, its dynasties also participated in a push eastwards into Slavic-speaking regions. At the Saxon Eastern March in the north, the Polabian Slavs east of the Elbe were conquered over generations of often brutal conflict. Under the later control of powerful German dynasties it became an important region within modern Germany, and home to its modern capital, Berlin. German population also moved eastwards from the 11th century, in what is known as the Ostsiedlung.[20] Over time, Slavic and German-speaking populations assimilated, meaning that many modern Germans have substantial Slavic ancestry.[18] From the 12th century, many German speakers settled as merchants and craftsmen in the Kingdom of Poland, where they came to constitute a significant proportion of the population in many urban centers such as Gdańsk.[18] During the 13th century, the Teutonic Knights began conquering the Old Prussians, and established what would eventually become the powerful German state of Prussia.[20]

Further south, Bohemia and Hungary developed as kingdoms with their own non-German speaking elites. The Austrian March on the Middle Danube stopped expanding eastwards towards Hungary in the 11th century. Under Ottokar II, Bohemia (corresponding roughly to modern Czechia) became a kingdom within the empire, and even managed to take control of Austria, which was German-speaking. However, the late 13th century saw the election of Rudolf I of the House of Habsburg to the imperial throne, and he was able to acquire Austria for his own family. The Habsburgs would continue to play an important role in European history for centuries afterwards. Under the leadership of the Habsburgs the Holy Roman Empire itself remained weak, and by the late Middle Ages much of Lotharingia and Burgundy had come under the control of French dynasts, the House of Valois-Burgundy and House of Valois-Anjou. Step by step, Italy, Switzerland, Lorraine, and Savoy were no longer subject to effective imperial control.

Trade increased and there was a specialization of the arts and crafts.[21] In the late Middle Ages the German economy grew under the influence of urban centers, which increased in size and wealth and formed powerful leagues, such as the Hanseatic League and the Swabian League, in order to protect their interests, often through supporting the German kings in their struggles with the nobility.[20] These urban leagues significantly contributed to the development of German commerce and banking. German merchants of Hanseatic cities settled in cities throughout Northern Europe beyond the German lands.[22]

Modern history

[edit]

The Habsburg dynasty managed to maintain their grip upon the imperial throne in the early modern period. While the empire itself continued to be largely de-centralized, the Habsburgs' personal power increased outside of the core German lands. Charles V personally inherited control of the kingdoms of Hungary and Bohemia, the wealthy Low Countries (roughly modern Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands), the Kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Sicily, Naples, and Sardinia, and the Dukedom of Milan. Of these, the Bohemian and Hungarian titles remained connected to the imperial throne for centuries, making Austria a powerful multilingual empire in its own right. On the other hand, the Low Countries went to the Spanish crown and continued to evolve separately from Germany.

The introduction of printing by the German inventor Johannes Gutenberg contributed to the formation of a new understanding of faith and reason. At this time, the German monk Martin Luther pushed for reforms within the Catholic Church. Luther's efforts culminated in the Protestant Reformation.[21]

Religious schism was a leading cause of the Thirty Years' War, a conflict that tore apart the Holy Roman Empire and its neighbours, leading to the death of millions of Germans. The terms of the Peace of Westphalia (1648) ending the war, included a major reduction in the central authority of the Holy Roman Emperor.[23] Among the most powerful German states to emerge in the aftermath was Protestant Prussia, under the rule of the House of Hohenzollern.[24] Charles V and his Habsburg dynasty defended Roman Catholicism.

In the 18th century, German culture was significantly influenced by the Enlightenment.[23]

After centuries of political fragmentation, a sense of German unity began to emerge in the 18th century.[7] The Holy Roman Empire continued to decline until being dissolved altogether by Napoleon in 1806. In central Europe, the Napoleonic wars ushered in great social, political and economic changes, and catalyzed a national awakening among the Germans. By the late 18th century, German intellectuals such as Johann Gottfried Herder articulated the concept of a German identity rooted in language, and this notion helped spark the German nationalist movement, which sought to unify the Germans into a single nation state.[19] Eventually, shared ancestry, culture and language (though not religion) came to define German nationalism.[17] The Napoleonic Wars ended with the Congress of Vienna (1815), and left most of the German states loosely united under the German Confederation. The confederation came to be dominated by the Catholic Austrian Empire, to the dismay of many German nationalists, who saw the German Confederation as an inadequate answer to the German Question.[24]

Throughout the 19th century, Prussia continued to grow in power.[25] In 1848, German revolutionaries set up the temporary Frankfurt Parliament, but failed in their aim of forming a united German homeland. The Prussians proposed an Erfurt Union of the German states, but this effort was torpedoed by the Austrians through the Punctation of Olmütz (1850), recreating the German Confederation. In response, Prussia sought to use the Zollverein customs union to increase its power among the German states.[24] Under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, Prussia expanded its sphere of influence and together with its German allies defeated Denmark in the Second Schleswig War and soon after Austria in the Austro-Prussian War, subsequently establishing the North German Confederation. In 1871, the Prussian coalition decisively defeated the Second French Empire in the Franco-Prussian War, annexing the German speaking region of Alsace-Lorraine. After taking Paris, Prussia and their allies proclaimed the formation of a united German Empire.[19]

In the years following unification, German society was radically changed by numerous processes, including industrialization, rationalization, secularization and the rise of capitalism.[25] German power increased considerably and numerous overseas colonies were established.[26] During this time, the German population grew considerably, and many emigrated to other countries (mainly North America), contributing to the growth of the German diaspora. Competition for colonies between the Great Powers contributed to the outbreak of World War I, in which the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires formed the Central Powers, an alliance that was ultimately defeated, with none of the empires comprising it surviving the aftermath of the war. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires were both dissolved and partitioned, resulting in millions of Germans becoming ethnic minorities in other countries.[27] The monarchical rulers of the German states, including the German emperor Wilhelm II, were overthrown in the November Revolution which led to the establishment of the Weimar Republic. The Germans of the Austrian side of the Dual Monarchy proclaimed the Republic of German-Austria, and sought to be incorporated into the German state, but this was forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles and Treaty of Saint-Germain.[26]

What many Germans saw as the "humiliation of Versailles",[28] continuing traditions of authoritarian and antisemitic ideologies,[25] and the Great Depression all contributed to the rise of Austrian-born Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, who after coming to power democratically in the early 1930s, abolished the Weimar Republic and formed the totalitarian Third Reich. In his quest to subjugate Europe, six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. WWII resulted in widespread destruction and the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians, while the German state was partitioned. About 12 million Germans had to flee or were expelled from Eastern Europe.[29] Significant damage was also done to the German reputation and identity,[27] which became far less nationalistic than it previously was.[28]

The German states of West Germany and East Germany became focal points of the Cold War, but were reunified in 1990. Although there were fears that the reunified Germany might resume nationalist politics, the country is today widely regarded as a "stablizing actor in the heart of Europe" and a "promoter of democratic integration".[28]

Language

[edit]

German is the native language of most Germans, and historically many northern Germans spoke the closely related language Low German. The German language is the key marker of German ethnic identity.[7][17] German and Low German are West Germanic languages closely related to Dutch, Frisian languages (in particular North Frisian and Saterland Frisian), Luxembourgish, and English.[7] Modern Standard German is based on High German and Central German, and is the first or second language of most Germans, but notably not the Volga Germans.[30]

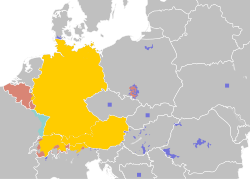

Geographic distribution

[edit]It is estimated that there are over 100 million Germans today, most of whom live in Germany, where they constitute the majority of the population.[31] There are also sizable populations of Germans in Austria, Switzerland, the United States, Brazil, France, Kazakhstan, Russia, Argentina, Canada, Poland, Italy, Hungary, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Paraguay, and Namibia.[32][33]

Culture

[edit]

The Germans are marked by great regional diversity, which makes identifying a single German culture quite difficult.[34] The arts and sciences have for centuries been an important part of German identity.[35] The Age of Enlightenment and the Romantic era saw a notable flourishing of German culture. Germans of this period who contributed significantly to the arts and sciences include the writers Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, Johann Gottfried Herder, Friedrich Hölderlin, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Heinrich Heine, Novalis and the Brothers Grimm, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, the painter Caspar David Friedrich, and the composers Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn, Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert, Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner.[34]

Popular German dishes include brown bread and stew. Germans consume a high amount of alcohol, particularly beer, compared to other European peoples. Obesity is relatively widespread among Germans.[34]

Carnival (German: Karneval, Fasching, or Fastnacht) is an important part of German culture, particularly in Southern Germany and the Rhineland. An important German festival is the Oktoberfest.[34]

A steadily shrinking majority of Germans are Christians. About a third are Roman Catholics, while one third adheres to Protestantism. Another third does not profess any religion.[17] Christian holidays such as Christmas and Easter are celebrated by many Germans.[36] The number of Muslims is growing.[36] There is also a notable Jewish community, which was decimated in the Holocaust.[37] Remembering the Holocaust is an important part of German culture.[25]

Identity

[edit]A German ethnic identity began to emerge during the early medieval period.[38] These peoples came to be referred to by the High German term diutisc, which means "ethnic" or "relating to the people". The German endonym Deutsche is derived from this word.[7] In subsequent centuries, the German lands were relatively decentralized, leading to the maintenance of a number of strong regional identities.[19][20]

The German nationalist movement emerged among German intellectuals in the late 18th century. They saw the Germans as a people united by language and advocated the unification of all Germans into a single nation state, which was partially achieved in 1871. By the late 19th and early 20th century, German identity came to be defined by a shared descent, culture, and history.[4] Völkisch elements identified Germanness with "a shared Christian heritage" and "biological essence", to the exclusion of the notable Jewish minority.[39] After the Holocaust and the downfall of Nazism, "any confident sense of Germanness had become suspect, if not impossible".[40] East Germany and West Germany both sought to build up an identity on historical or ideological lines, distancing themselves both from the Nazi past and each other.[40] After German reunification in 1990, the political discourse was characterized by the idea of a "shared, ethnoculturally defined Germanness", and the general climate became increasingly xenophobic during the 1990s.[40] Today, discussion on Germanness may stress various aspects, such as commitment to pluralism and the German constitution (constitutional patriotism),[41] or the notion of a Kulturnation (nation sharing a common culture).[42] The German language remains the primary criterion of modern German identity.[4]

See also

[edit]- Anti-German sentiment – Opposition to Germany, its inhabitants and culture

- Demographics of Germany

- Die Deutschen – ZDF's documentary television series

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- German diaspora – Group of ethnic germans

- Germanophile – Someone with a strong interest in or love of German people, culture, and history

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "German Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ a b "German". Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. 2010. p. 733. ISBN 978-0199571123. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz (ed.). "Article 116". Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

Unless otherwise provided by a law, a German within the meaning of this Basic Law is a person who possesses German citizenship or who has been admitted to the territory of the German Reich within the boundaries of 31 December 1937 as a refugee or expellee of German ethnic origin or as the spouse or descendant of such person.

- ^ a b c Moser 2011, p. 172. "German identity developed through a long historical process that led, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to the definition of the German nation as both a community of descent (Volksgemeinschaft) and shared culture and experience. Today, the German language is the primary though not exclusive criterion of German identity."

- ^ Haarmann 2015, p. 313. "After centuries of political fragmentation, a sense of national unity as Germans began to evolve in the eighteenth century, and the German language became a key marker of national identity."

- ^ Moser 2011, p. 171. "The Germans live in Central Europe, mostly in Germany... Estimates of the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 million to 150 million, depending on how German is defined, but it is probably more appropriate to accept the lower figure."

- ^ a b c d e f Haarmann 2015, p. 313.

- ^ Hoad, T. F. (2003). "German". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001. ISBN 9780192830982. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Germans". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Drinkwater, John Frederick (2012). "Germans". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 613. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001. ISBN 9780191735257. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Heather, Peter. "Germany: Ancient History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Within the boundaries of present-day Germany... Germanic peoples such as the eastern Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringians, Alemanni, and Bavarians—all speaking West Germanic dialects—had merged Germanic and borrowed Roman cultural features. It was among these groups that a German language and ethnic identity would gradually develop during the Middle Ages.

- ^ a b c d e Minahan 2000, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Steuer 2021, p. 32.

- ^ Steuer 2021, p. 89, 1310.

- ^ Timpe & Scardigli 2010, p. 636.

- ^ Todd 1999, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Moser 2011, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Haarmann 2015, pp. 313–314.

- ^ a b c d Haarmann 2015, p. 314.

- ^ a b c d e Minahan 2000, pp. 289–290.

- ^ a b c d Moser 2011, p. 173.

- ^ Minahan 2000, p. 290.

- ^ a b Moser 2011, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b c Minahan 2000, pp. 290–291.

- ^ a b c d e Moser 2011, p. 174.

- ^ a b Minahan 2000, pp. 291–292.

- ^ a b Haarmann 2015, pp. 314–315.

- ^ a b c Haarmann 2015, p. 316.

- ^ Troebst, Stefan (2012). "The Discourse on Forced Migration and European Culture of Remembrance". The Hungarian Historical Review. 1 (3/4): 397–414. JSTOR 42568610.

- ^ Minahan 2000, p. 288.

- ^ Moser 2011, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Haarmann 2015, p. 313. "Of the 100 million German speakers worldwide, about three quarters (76 million) live in Germany, where they account for 92 percent of the population. Populations of Germans live elsewhere in Central and Western Europe, with the largest communities in Austria (7.6 million), Switzerland (4.2 million), France (1.2 million), Kazakhstan (900,000), Russia (840,000), Poland (700,000), Italy (280,000), and Hungary (250,000). Some 1.6 million U.S. citizens speak German as their first language, the largest number of German speakers overseas."

- ^ Moser 2011, pp. 171–172. "The Germans live in Central Europe, mostly in Germany... The largest populations outside of these countries are found in the United States (5 million), Brazil (3 million), the former Soviet Union (2 million), Argentina (500,000), Canada (450,000), Spain (170,000), Australia (110,000), the United Kingdom (100,000), and South Africa (75,000). "

- ^ a b c d Moser 2011, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2005, pp. 334–335.

- ^ a b Moser 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Minahan 2000, p. 174.

- ^ Haarmann 2015, p. 313 "Germans are a Germanic (or Teutonic) people that are indigenous to Central Europe... Germanic tribes have inhabited Central Europe since at least Roman times, but it was not until the early Middle Ages that a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge."

- ^ Rock 2019, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Rock 2019, p. 33.

- ^ Rock 2019, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Rock 2019, p. 34.

Bibliography

[edit]- Haarmann, Harald (2015). "Germans". In Danver, Steven (ed.). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. pp. 313–316. ISBN 978-1317464006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Moser, Johannes (2011). "Germans". In Cole, Jeffrey (ed.). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 171–177. ISBN 978-1598843026. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Minahan, James (2000). "Germans". One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 287–294. ISBN 0313309841. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Steuer, Heiko (2021). Germanen aus Sicht der Archäologie: Neue Thesen zu einem alten Thema. de Gruyter.

- Timpe, Dieter; Scardigli, Barbara; et al. (2010) [1998]. "Germanen, Germania, Germanische Altertumskunde". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. pp. 363–876. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- Todd, Malcolm (1999). The Early Germans (2009 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-3756-0. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2005). "Germans". Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. pp. 330–335. ISBN 1438129181. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Craig, Gordon Alexander (1983). The Germans. New American Library. ISBN 0452006228. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Elias, Norbert (1996). The Germans. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231105630. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- James, Harold (2000). A German Identity (2 ed.). Phoenix Press. ISBN 1842122045. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Mallory, J. P. (1991). "Germans". In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames & Hudson. pp. 84–87. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Rock, Lena (2019). As German as Kafka: Identity and Singularity in German Literature around 1900 and 2000. Leuven University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvss3xg0. ISBN 9789462701786. JSTOR j.ctvss3xg0. S2CID 241563332.

- Todd, Malcolm (2004a). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405117142. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Wells, Peter S. (2011). "The Ancient Germans". In Bonfante, Larissa (ed.). The Barbarians of Ancient Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–232. ISBN 978-0-521-19404-4. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

Germans

View on GrokipediaTheir defining language, German, is a West Germanic tongue spoken as a first language by approximately 95–97 million people globally, with native speakers concentrated in Germany (78%), Austria (8%), Switzerland (6%), and smaller communities elsewhere.[4] [1]

Historically, these tribes evolved through migrations and interactions with the Roman Empire, coalescing into medieval stem duchies and the decentralized Holy Roman Empire (962–1806), which laid foundations for a shared cultural and linguistic identity amid feudal fragmentation.

In the modern era, Germans achieved national unification in 1871 under Prussian leadership, rapidly industrialized to become Europe's economic powerhouse by the early 20th century, and contributed foundational advancements in philosophy (e.g., Kant's critiques of reason, Nietzsche's critiques of morality), science (e.g., Einstein's relativity, Planck's quantum theory), and engineering (e.g., diesel engine, electron microscope).[5] [6]

However, the 20th century saw catastrophic militarism under the Wilhelmine Empire and Nazi regime, culminating in World War II defeats, the Holocaust's systematic genocide of six million Jews and millions of others, and postwar division into democratic West Germany and communist East Germany until reunification in 1990.

Today, Germans maintain the world's fourth-largest economy by nominal GDP, characterized by high productivity, export-oriented manufacturing in automobiles and chemicals, and a social market system, though facing challenges from below-replacement fertility rates (1.4 children per woman), an aging population, and recent net immigration altering ethnic composition.[7][1]

Terminology and Ethnonymy

Etymology and Exonyms

The ethnonym Germani first appears in the historical record in Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, written between 58 and 50 BCE, where it refers to tribes inhabiting territories east of the Rhine River, distinguishing them from the Celts (Gauls) to the west.[8] Caesar likely adopted the term from local Celtic or indigenous usage to describe a specific tribal group, subsequently generalizing it to broader Germanic populations encountered during Roman campaigns.[9] The precise origin of Germani remains uncertain, with proposed derivations including a connection to Proto-Germanic *gēr- or *gaizaz ("spear"), implying "spear-men" or warriors armed with spears, consistent with archaeological evidence of early Germanic weaponry; alternative Celtic roots like *gair- ("neighbor") have been suggested but lack strong attestation.[10] [11] Exonyms for Germans in other languages often stem from Roman or medieval encounters with particular Germanic tribes rather than a unified ethnonym, reflecting fragmented tribal identities before modern national consolidation. In Romance languages, derivatives of Latin Germani persist, such as Italian germani or Spanish alemanes (influenced by Alamanni); French allemand and Allemagne, however, trace to the Alamanni confederation defeated by the Franks in the 5th century CE.[8] Germanic languages outside High German frequently use forms related to Old High German diutisc ("of the people"), yielding Dutch Duits and Danish tysk. Slavic exonyms like Polish Niemcy or Russian nemtsy derive from Proto-Slavic němьcь ("mute" or "incomprehensible"), arising from linguistic barriers during eastward migrations around the 6th–9th centuries CE.[12] In Finnic languages, Saksa references the Saxons, prominent in Viking-era interactions. These divergent terms underscore the absence of a single external designation until Roman Germania influenced cartography and diplomacy from the 1st century BCE onward.[12]Endonyms and Historical Self-Designations

The ancient Germanic tribes, spanning from the late Bronze Age through the Roman era (circa 1200 BCE to 500 CE), did not employ a unified endonym to describe themselves collectively as a distinct ethnic or linguistic group; instead, they identified primarily by specific tribal names, such as Sweboz (ancestral to Suebi, implying "free" or "self-ruling" in Proto-Germanic) or localized kin groups like the Cherusci and Marcomanni, reflecting decentralized social structures without overarching self-conception beyond immediate alliances.[13] This tribal fragmentation is evidenced in Roman accounts cross-corroborated by archaeological distributions of Jastorf culture artifacts, which show no pan-Germanic nomenclature in runic inscriptions or early Germanic linguistics.[14] The emergence of a broader self-designation occurred during the Early Middle Ages with the Old High German term diutisc (or theudisk), first attested around 786 CE in the Indiculus de correctionibus Franconicis linguamque Franconicam by an East Frankish cleric, denoting "of the people" or "vernacular" in contrast to Latin (lingua romana).[15] Derived from Proto-Germanic *þiudiskaz, rooted in PIE *teutéh ("tribe" or "folk"), it initially described the Germanic speech of the Frankish and Alemannic realms rather than ethnicity, evolving by the 9th century to encompass speakers as Theodisci in Latin texts, distinguishing them from Romance-speaking Franks.[16][17] By the 10th century, amid the Ottonian dynasty's consolidation (919–1024 CE), diutsc and variants like teutsch solidified as an ethnic-linguistic endonym for inhabitants of the East Frankish Kingdom, later the Holy Roman Empire's German-speaking core, as seen in chronicles like Widukind of Corvey's Res gestae Saxonicae (circa 968 CE), where it denoted the "German" nation (natio Teutonica).[18] This usage persisted through the medieval period, with the Imperial Diet referring to the "Teutsche Nation" by the 15th century, emphasizing linguistic continuity over Roman-imposed exonyms.[14] In contemporary usage, "Deutsche" serves as the standard endonym for Germans, reflecting this historical trajectory from tribal particularism to a folk-based collective identity tied to the High German dialect continuum.[15]Origins and Anthropology

Genetic and Archaeological Evidence

Archaeological evidence for the early Germanic peoples is primarily associated with the Pre-Roman Iron Age cultures in northern Central Europe, particularly the Jastorf culture (c. 600 BCE to 1 CE), which spanned modern-day northern Germany, Jutland, and parts of Poland. This culture is characterized by cremation burials in urn fields, iron weapons such as swords and spears, agricultural tools like sickles, and fibulae for clothing fastening, indicating settled farming communities with emerging social hierarchies and trade networks.[19] These material remains correlate with linguistic reconstructions of Proto-Germanic speech, emerging around 500 BCE in southern Scandinavia and northern Germany, distinct from contemporaneous Celtic Hallstatt culture to the south. Earlier precursors include the Nordic Bronze Age (c. 1700–500 BCE), with its single-grave mound burials containing bronze razors, axes, and lurs (ritual horns), reflecting a maritime-oriented warrior society in southern Scandinavia and northern Germany that shows continuity in settlement patterns and artifact styles into the Iron Age.[20] Human presence in the territory of modern Germany dates to the Middle Paleolithic, with remains of Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals, followed by modern humans (Homo sapiens) arriving during the Upper Paleolithic around 45,000 years ago, represented by Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) populations adapted to post-glacial environments. The Mesolithic period saw continued WHG dominance in northern Europe. Around 5500 BCE, the Neolithic transition introduced Early European Farmer (EEF) migrants from Anatolia, who admixed with local hunter-gatherers; late Neolithic Central European farmers, including in Germany, carried approximately 25% WHG ancestry.[21] A profound genetic shift occurred around 3000–2500 BCE with the arrival of Western Steppe Herder (WSH) ancestry linked to Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures, with initial proportions up to 60% declining to 25–35% over subsequent centuries through admixture with local groups.[22] Genetic studies of ancient DNA confirm that the ancestors of Germanic peoples incorporated significant steppe pastoralist ancestry during the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age, primarily through the Corded Ware culture (c. 2900–2350 BCE) in northern and central Europe. Individuals from Corded Ware sites in Germany carried approximately 75% ancestry genetically similar to Yamnaya steppe herders from the Pontic-Caspian region (c. 3300–2600 BCE), who migrated westward introducing Indo-European linguistic elements and Y-chromosome haplogroups like R1a and R1b subclades (e.g., R1b-U106 prevalent in later Germanic groups). This admixture combined steppe DNA with local Western Hunter-Gatherer and Early European Farmer components, forming the genetic foundation for subsequent cultures like the Nordic Bronze Age, where ancient genomes show persistent high levels of this steppe heritage alongside local continuity.[23] The Iron Age saw the emergence of Celtic (Hallstatt and La Tène) and Germanic tribal groups, with genetic continuity from Bronze Age populations and regional clines: higher steppe and WHG ancestry in the north, more EEF in the south. Roman influence in southern and western Germany introduced limited Mediterranean gene flow, primarily through military presence, with overall minor genetic impact. Ancient DNA from Iron Age and early medieval sites further demonstrates genetic continuity for northern Germanic populations, with Late Iron Age individuals in northern Europe clustering closely with modern North Germans and Scandinavians, characterized by elevated steppe ancestry (around 40–50% in contemporary Germans) and haplogroups such as I1-M253.[20] In contrast, southern German regions exhibit greater admixture from Bell Beaker and Hallstatt Celtic groups, reflecting regional heterogeneity before Roman-era influences, though early medieval Bavarian samples associated with Germanic speakers show a resurgence of northern European ancestry profiles.[24] Overall, these data indicate that Germanic ethnogenesis involved demographic expansions from a northern core, with minimal disruption in genetic structure from the Bronze Age onward, challenging narratives of wholesale population replacement in favor of elite-driven cultural and linguistic shifts.[25]Proto-Germanic Tribes and Early Settlements

The speakers of Proto-Germanic, the common ancestral language of all later Germanic tongues, inhabited a homeland spanning southern Scandinavia (including Denmark and southern Sweden) and the northern coastal regions of present-day Germany during the late Nordic Bronze Age and early Pre-Roman Iron Age, roughly from 500 BCE onward. This linguistic community arose through sound shifts and innovations distinguishing it from other Indo-European branches, with archaeological correlates in the transition from bronze-working societies to iron-using ones centered around the Jutland Peninsula and the lower Elbe River basin. Genetic and material evidence indicates continuity from earlier Corded Ware and Battle Axe culture descendants, with settlements featuring clustered farmsteads, longhouses, and subsistence based on mixed agriculture, animal husbandry, and coastal fishing.[26][27] The Jastorf culture, dated approximately 600 BCE to 1 CE, represents the primary archaeological manifestation of these early Proto-Germanic groups, extending from Holstein and Mecklenburg in northern Germany northward into Jutland and eastward toward the Oder River. Characterized by distinctive cremation burials in urn fields, iron tools, and pottery with cord-impressed designs, this culture reflects a semi-nomadic to sedentary tribal society organized in kin-based clans, with evidence of fortified hilltop settlements emerging by the 4th century BCE in response to inter-group conflicts and resource pressures. Population estimates for these regions suggest densities of 5-10 individuals per square kilometer, supported by rye and barley cultivation alongside livestock rearing, though climatic cooling around 300 BCE prompted southward expansions into unoccupied lands east of the Elbe.[27][28] Early tribal divisions among Proto-Germanic speakers remained fluid, without the fixed confederations recorded later by Roman authors, but linguistic reconstructions imply dialectal clusters that foreshadowed North, East, and West Germanic branches: coastal "Ingaevonic" groups along the North Sea, inland "Hermionic" ones near the Elbe, and potentially "Istvaeonic" variants in the Rhine fringes. These proto-tribes engaged in limited trade with Celtic neighbors to the south, exchanging amber and furs for bronze and salt, while maintaining oral traditions of heroic sagas and rune precursors etched on artifacts by the 1st century BCE. Settlement patterns emphasized defensible riverine and coastal sites, with bog offerings of weapons and tools indicating ritual practices tied to fertility and warfare deities.[29][28]Historical Development

Ancient Germanic Peoples and Roman Interactions

The Germanic peoples emerged as a distinct Indo-European linguistic and cultural group during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, with archaeological evidence linking them to the Jastorf culture, which flourished from approximately 600 BC to 1 AD across northern Germany, Jutland, and parts of Poland. This culture is characterized by urnfield burials, iron tools, and settlements indicating a shift toward sedentary farming communities supplemented by herding and raiding, marking the material basis for Proto-Germanic speakers who expanded from southern Scandinavia and the North Sea coast.[30][29] Initial Roman interactions with Germanic tribes occurred during Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars, where in 55 BC he confronted the Suebi under Ariovistus, defeating them but halting further incursions across the Rhine. Systematic Roman expansion into Germania Magna began under Augustus, aiming to secure the Elbe River as the northeastern frontier. Nero Claudius Drusus launched campaigns from 12 to 9 BC, crossing the Rhine to subdue the Sugambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri, advancing northward to subjugate the Frisians and Chauci, and reaching the Elbe by constructing canals and fleets for logistics. His brother Tiberius continued operations in 8–7 BC and resumed in 4–5 AD, consolidating control over tribes like the Chatti and Marcomanni through punitive expeditions and alliances.[31][32] The pivotal event disrupting Roman ambitions was the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in September 9 AD, where Arminius, a Cheruscan noble educated as a Roman auxiliary and married to the daughter of Segestes, orchestrated an ambush against Publius Quinctilius Varus's three legions (XVII, XVIII, XIX) and auxiliaries, totaling around 15,000–20,000 troops. Over three to four days in dense terrain, the Germanic coalition exploited poor weather, supply issues, and Varus's overreliance on local guides, annihilating the forces and preventing recovery of the eagles until partial retrieval under Germanicus in 15–16 AD. This disaster prompted Augustus's lament, "Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!", and led to the abandonment of conquest east of the Rhine, establishing it as the limes Germanicus.[33][32] Post-Teutoburg, interactions shifted to defensive frontier management, trade via the Rhine, and incorporation of Germanic foederati as auxiliaries, though raids persisted from tribes like the Alemanni and Franks. Publius Cornelius Tacitus's Germania (c. 98 AD) provides ethnographic insights, portraying the Germans as indigenous to their lands with uniform physical traits—fierce blue eyes, reddish hair, and robust builds—organized in tribal kingships tempered by assemblies, valuing freedom, martial prowess, and simple agrarian life without urban decadence or hereditary nobility. Tacitus notes their warfare tactics emphasizing infantry shields and spears, women's roles in battle encouragement, and customs like communal decision-making, though modern analysis suggests his account idealizes them as a foil to Roman corruption.[34][35]Migration Period and Early Medieval Kingdoms

The Migration Period, roughly 375–568 AD, saw massive displacements of Germanic tribes, driven primarily by Hunnic incursions from the east, alongside demographic pressures and the weakening of Roman frontiers.[36] The Visigoths, fleeing Hunnic domination, crossed the Danube into Roman territory in 376 AD, culminating in their victory over Roman Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople on August 9, 378 AD, which killed Valens and exposed Roman vulnerabilities.[36] This event marked a turning point, enabling further Germanic incursions; Alaric's Visigoths sacked Rome in 410 AD, though they sought federation rather than conquest.[36] Simultaneously, in 406 AD, Vandals, Suebi, and Alans crossed the frozen Rhine into Gaul, fragmenting Roman control and leading to Vandal settlements in Spain and eventual migration to North Africa by 429 AD under Geiseric.[36] Among tribes ancestral to later Germans, the Franks expanded from the lower Rhine, with the Salian Franks under Childeric and Clovis conquering Roman Gaul. Clovis defeated the last Roman official Syagrius at Soissons in 486 AD, subdued the Alemanni around 496 AD, and incorporated Burgundian territories by 534 AD, unifying much of Gaul under Merovingian rule.[37] His conversion to Nicene Christianity circa 496 AD aligned the Franks with the Gallo-Roman population, distinguishing them from Arian Goths and facilitating consolidation.[37] The Alemanni, confederated in the upper Rhine region since the 3rd century AD, persisted in what became Swabia despite defeats, while Bavarians—likely amalgamations of Roman provincials and Marcomannic remnants—emerged as a distinct group in the southeast by the 6th century AD.[38] Saxons, originating from northern coastal regions, conducted raids into Britain from the 5th century but maintained strongholds in modern northern Germany and the Netherlands, resisting southern expansion.[39] Transitioning to early medieval kingdoms, the Carolingian dynasty supplanted the Merovingians; Pepin the Short deposed Childeric III in 751 AD, and his son Charlemagne (r. 768–814 AD) vastly expanded the realm. Charlemagne's Saxon Wars (772–804 AD) involved brutal campaigns against pagan Saxons, including the Massacre of Verden in 782 AD where 4,500 were executed, culminating in forced Christianization and incorporation into the Frankish orbit.[39] He also subdued the Bavarians under Tassilo III in 788 AD and defeated the Avars in the 790s, securing the eastern marches.[40] Crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day 800 AD, Charlemagne's empire fragmented after his death; the Treaty of Verdun in 843 AD divided it among his grandsons, with Louis the German receiving East Francia, encompassing core Germanic territories east of the Rhine.[41] In East Francia, stem duchies coalesced around tribal identities by the late 9th century: Saxony under Liudolfings, Franconia from Frankish heartlands, Swabia from Alemanni, Bavaria from Baiuvarii, and Lorraine as a buffer.[42] These duchies provided military leadership against Magyar raids, with Duke Henry of Saxony elected king in 919 AD, initiating the Ottonian dynasty and stabilizing the realm as the precursor to the Holy Roman Empire.[40] This period solidified Germanic political structures, blending tribal customs with Roman administrative legacies and Christian institutions.[38]Holy Roman Empire and Feudal Fragmentation

The Holy Roman Empire emerged in 962 when Otto I, Duke of Saxony and King of the East Franks since 936, was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope John XII on February 2, establishing a continuity with the Carolingian imperial tradition while centering authority on German rulers.[43] [44] This polity primarily comprised German-speaking territories in Central Europe, evolving from the East Frankish realm partitioned under the Treaty of Verdun in 843, with subsequent kings from the Saxon dynasty (919–1024) consolidating power against Magyar incursions and internal rivals.[45] The empire's structure as an elective monarchy, where the king—upon election by leading princes—sought imperial coronation, inherently limited centralized control, as emperors depended on noble consensus rather than hereditary absolutism.[46] Successive dynasties, including the Franconians (1024–1125) under Henry II and Conrad II, further entrenched feudal decentralization, with power devolving to stem duchies like Saxony, Bavaria, Swabia, and Franconia, alongside ecclesiastical principalities and free imperial cities.[47] The Investiture Controversy (1075–1122), pitting Emperor Henry IV against Pope Gregory VII over the appointment of bishops—who controlled vast lands and served as imperial administrators—exacerbated fragmentation by empowering secular princes who allied with the papacy to curb royal authority, culminating in the Concordat of Worms that restricted lay investiture and affirmed ecclesiastical autonomy.[48] [49] This conflict, rooted in the dual role of church offices as both spiritual and temporal fiefs, weakened the emperor's ability to enforce cohesion, allowing local rulers to extract concessions and fortify hereditary domains. By the 14th century, feudal particularism dominated, with over 300 semi-autonomous entities by 1500, including principalities, counties, and bishoprics, governed through assemblies like the Imperial Diet but lacking a standing army or uniform taxation under the emperor.[46] The Golden Bull of 1356, promulgated by Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg, formalized this by enshrining the election of the emperor by seven prince-electors—three ecclesiastical (Mainz, Trier, Cologne archbishops) and four secular (Bohemia, Palatinate, Saxony, Brandenburg)—bypassing papal veto and granting electors hereditary privileges, thus institutionalizing oligarchic checks on imperial power.[50] [51] This framework perpetuated economic and political balkanization among German lands, fostering regional identities and rivalries that impeded national unification until the 19th century, as emperors prioritized dynastic interests over imperial reform.[52]Reformation, Wars of Religion, and Absolutism

The Protestant Reformation originated in the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire when Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and theology professor at the University of Wittenberg, publicly challenged Catholic doctrines on October 31, 1517, by posting his Ninety-Five Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Saxony.[53] Luther's critiques targeted the sale of indulgences, papal authority, and perceived corruptions, sparking widespread debate amplified by the printing press, which disseminated his ideas rapidly across German territories. By the 1520s, electoral Saxony and other northern principalities adopted Lutheranism, while Luther's German translation of the Bible (New Testament 1522, full 1534) standardized the emerging High German language and reinforced a sense of shared cultural identity among German speakers, distinct from Latin ecclesiastical traditions.[54] The Reformation fragmented religious unity, leading to the formation of the Schmalkaldic League of Protestant princes in 1531 and conflicts with Catholic Habsburg Emperor Charles V, whose enforcement of the 1521 Edict of Worms against Luther deepened princely resistance. Religious tensions escalated into the Wars of Religion, culminating in the Schmalkaldic War (1546–1547), where Charles V initially defeated Protestant forces but failed to restore Catholic dominance, prompting the Peace of Augsburg on September 25, 1555. This treaty established cuius regio, eius religio, granting territorial rulers the right to impose Lutheranism or Catholicism on subjects, excluding Calvinism and Anabaptists, and providing for ecclesiastical reservation to protect church lands.[55] While temporarily stabilizing the Empire, the settlement fueled further unrest, as Calvinism spread in the Palatinate and elsewhere, violating the peace. The Bohemian Revolt and Defenestration of Prague in 1618 ignited the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), a multifaceted conflict blending religious strife, Habsburg imperial ambitions, and interventions by Sweden, France, and Denmark, which devastated German territories through mercenary armies, famine, and disease.[56] Estimates place total deaths at 4.5 to 8 million, with German population losses reaching 20–40% in affected regions like the Palatinate and Württemberg, reducing overall Empire population from about 20 million in 1618 to 12–15 million by 1648.[56] The Peace of Westphalia, signed on October 24, 1648, in Münster and Osnabrück, ended the war by recognizing Calvinism, affirming territorial sovereignty under the cuius regio principle extended to include Reformed churches, and granting Sweden and France gains at the Empire's expense, while indemnifying Protestant princes for seized ecclesiastical properties.[56] This accord weakened the Holy Roman Emperor's authority, elevating over 300 semi-autonomous German states and free cities, and shifted power toward stronger principalities. In the ensuing absolutist era, rulers like Frederick William, the Great Elector of Brandenburg-Prussia (r. 1640–1688), centralized authority by creating a permanent standing army of 30,000 by 1688, funded through excise taxes and noble obedience, transforming Brandenburg-Prussia into a militarized absolutist state despite its fragmented holdings.[57] Similarly, Habsburg Austria under Leopold I (r. 1658–1705) pursued absolutism through reconquest of Hungary and suppression of Protestantism, though multi-ethnic composition limited uniformity, while Bavarian and Saxon electors also consolidated domestic control, laying foundations for emerging great powers amid persistent imperial decentralization.[58]19th-Century Nationalism and Unification

The dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 under French pressure from Napoleon Bonaparte marked the end of medieval German political unity, paving the way for fragmented states amid the Napoleonic Wars.[59] The Congress of Vienna in 1815 reorganized Central Europe, creating the German Confederation as a loose association of 39 sovereign states, with Austria presiding over the federal diet at Frankfurt and Prussia emerging as a counterweight.[60] This structure suppressed liberal and national aspirations while aiming to balance power between Austria and Prussia, but it fostered resentment against foreign domination and internal disunity.[61] German nationalism gained momentum in the early 19th century, drawing on cultural and linguistic ties emphasized by Romantic thinkers like Johann Gottfried Herder and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who in his 1808 Addresses to the German Nation urged resistance to French occupation and revival of a shared German identity.[62] The Wars of Liberation (1813–1815), where Prussian-led forces defeated Napoleon at Leipzig in October 1813 and Waterloo in June 1815, galvanized patriotic fervor, though the Vienna settlement disappointed nationalists by rejecting unification.[59] Student movements like the Burschenschaften and the 1817 Wartburg Festival symbolized demands for a single German state, but conservative repression via the Carlsbad Decrees of 1819 curtailed such activities.[62] Economic integration advanced through the Prussian-initiated Zollverein customs union, formalized on January 1, 1834, which abolished internal tariffs among participating states and imposed a uniform external tariff, excluding Austria and boosting Prussian industrial dominance.[63] By 1840, the Zollverein encompassed most German states except Austria, fostering trade growth—Prussian exports rose significantly—and laying groundwork for political cohesion by demonstrating practical benefits of unity under Prussian leadership.[64] This economic framework contrasted with the Confederation's political inertia, highlighting Prussia's capacity to lead integration. The Revolutions of 1848 exposed nationalist tensions, as uprisings across German states demanded constitutional government and unification. The Frankfurt National Assembly, convened on May 18, 1848, drafted a federal constitution adopted on March 28, 1849, offering the imperial crown to Prussian King Frederick William IV, who rejected it as deriving from a "rump parliament" lacking monarchical legitimacy.[65] The assembly's failure, amid Prussian military suppression of radicals and Austrian reconquest of its territories, underscored the limits of liberal nationalism without great-power support, shifting momentum toward authoritarian paths.[66] Otto von Bismarck, appointed Prussian minister-president in September 1862, pursued unification through "blood and iron" realpolitik, engineering wars to isolate rivals and consolidate Prussian hegemony. The Second Schleswig War (1864) against Denmark, allied with Austria, annexed Schleswig-Holstein after Prussian-Austrian victory at Dybbøl in April 1864.[67] The Austro-Prussian War (June–August 1866) ended decisively at Königgrätz on July 3, 1866, dissolving the German Confederation and forming the North German Confederation under Prussian control by August 18, 1866.[67] The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) sealed unification: Bismarck manipulated the Ems Dispatch in July 1870 to provoke French declaration of war, leading to Prussian victories including the capture of Napoleon III at Sedan on September 2, 1870, and the siege of Paris until January 1871.[67] On January 18, 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor, with the German Empire comprising 25 states (excluding Austria) formalized by April 16, 1871. This Kleindeutsche Lösung prioritized Protestant Prussian leadership over a Grossdeutsche including Catholic Austria, achieving unity through military prowess rather than democratic consensus.[67]German Empire, World War I, and Weimar Republic

The German Empire was proclaimed on 18 January 1871 in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, following Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), with King Wilhelm I of Prussia assuming the title of German Emperor under a federal constitution drafted by Otto von Bismarck.[68] This unification consolidated 25 states and three free cities into a hereditary monarchy dominated by Prussia, featuring a bicameral legislature with the Bundesrat representing states and the Reichstag elected by universal male suffrage, though real power rested with the chancellor and emperor.[69] The empire pursued Weltpolitik, acquiring colonies in Africa and the Pacific totaling about 1 million square miles by 1914, while Bismarck's alliance system aimed to isolate France.[70] Under Wilhelm II, who dismissed Bismarck in 1890 and ruled until 1918, the empire experienced explosive industrialization during the Second Industrial Revolution, with steel production rising from 0.7 million tons in 1870 to 17 million tons by 1913, surpassing Britain's output.[71] Population grew from 41 million in 1871 to 64.6 million by 1910, driven by high birth rates and rural-to-urban migration, with urban dwellers comprising 60% by 1910 and cities over 100,000 inhabitants housing one-fifth of the populace.[72] [73] This economic ascent, fueled by tariffs, cartels, and innovations in chemicals and electricity, positioned Germany as Europe's leading industrial power, but naval expansion challenging British supremacy and rigid military planning heightened continental tensions.[74] World War I erupted after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914, prompting Austria-Hungary—backed by Germany's "blank check" assurance of support—to issue an ultimatum to Serbia, leading to partial mobilization and the July Crisis.[75] Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August 1914 following Russian general mobilization, on France on 3 August, and invaded neutral Belgium on 4 August to execute the Schlieffen Plan for a rapid western victory, drawing Britain into the conflict via treaty obligations.[76] The war devolved into trench stalemate on the Western Front, with Germany achieving initial gains like the Schlieffen sweep's modification but failing to capture Paris; total mobilization yielded 13 million German troops, suffering 2 million deaths and 4.2 million wounded by 1918.[77] Unrestricted submarine warfare from 1917 provoked U.S. entry in April 1917, while internal strains from the British blockade—causing 750,000 civilian deaths from starvation—culminated in the Spring Offensive's failure and Allied counteroffensives, forcing armistice negotiations.[78] The armistice took effect at 11:00 a.m. on 11 November 1918 in Compiègne Forest, with Germany retaining its government but facing immediate evacuation of occupied territories and surrender of naval and air assets.[79] The Weimar Republic emerged from the November Revolution amid naval mutinies in Kiel and worker-soldier councils, with Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicating on 9 November 1918 and Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert becoming provisional president.[80] The National Assembly convened in Weimar on 6 February 1919, adopting a democratic constitution on 11 August 1919 that established a parliamentary system with proportional representation, universal suffrage for men and women over 20, and a strong presidency, though Article 48 allowed emergency decree powers that later enabled authoritarianism.[81] The Treaty of Versailles, signed 28 June 1919, imposed Article 231's war guilt clause, obliging Germany to cede 13% of its territory (including Alsace-Lorraine to France, Eupen-Malmédy to Belgium, and the Polish Corridor), lose 10% of its population, demilitarize the Rhineland, cap its army at 100,000 troops without air force or submarines, and pay reparations initially set at 132 billion gold marks (later adjusted).[70] [82] Economic woes defined Weimar's fragility: French-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr in January 1923 over missed reparations payments prompted passive resistance and currency printing, sparking hyperinflation that peaked in November 1923 with exchange rates hitting 4.21 trillion marks per U.S. dollar, eroding middle-class savings and fueling social unrest.[83] Stabilization via the Rentenmark in late 1923 and the Dawes Plan's 1924 reparations restructuring enabled brief recovery, with U.S. loans supporting growth until the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 triggered the Great Depression.[84] Unemployment soared to 6 million by 1932 (30% of the workforce), industrial production halved, and 40 governments formed between 1919 and 1933 amid street violence between communists and nationalists, with proportional representation fragmenting the Reichstag and empowering extremists.[85] [86] President Paul von Hindenburg's increasing use of Article 48 decrees underscored the republic's inability to resolve polarization rooted in Versailles resentments and economic volatility.Nazi Era and World War II

The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party, gained prominence in the economically distressed Weimar Republic amid hyperinflation and the Great Depression, achieving 37.3% of the vote in the July 1932 Reichstag elections, making it the largest party.[87] On January 30, 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor in a coalition government, reflecting elite miscalculations that the Nazis could be controlled.[88] The Reichstag Fire on February 27, 1933, enabled the Enabling Act of March 23, which granted Hitler dictatorial powers, effectively ending democracy and establishing a one-party state by July 1933.[87] Nazi domestic policies emphasized racial purity and authoritarian control, with the Nuremberg Laws enacted on September 15, 1935, stripping Jews of citizenship, prohibiting marriages between Jews and non-Jews, and defining Jewishness by ancestry rather than religion.[89] These measures institutionalized antisemitism, building on earlier boycotts and violence like Kristallnacht in November 1938, which destroyed synagogues and Jewish businesses with state complicity. Rearmament violated the Treaty of Versailles, expanding the Wehrmacht to over 1 million men by 1935, fueled by public enthusiasm for restoring national pride amid unemployment reductions from 6 million in 1932 to under 1 million by 1938 through public works and military spending.[90] Expansionist aggression began with the remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936, followed by the Anschluss with Austria on March 12, 1938, and the Munich Agreement on September 30, 1938, annexing the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia without resistance. World War II commenced on September 1, 1939, with the invasion of Poland using Blitzkrieg tactics, prompting declarations of war by Britain and France. German forces swiftly conquered Denmark and Norway in April 1940, the Low Countries and France by June 1940, and achieved initial successes in North Africa and the Balkans.[91] The invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa, launched on June 22, 1941, with over 3 million Axis troops, initially advanced deep into Soviet territory but stalled due to overextended supply lines, harsh winter conditions, and Soviet resilience, marking a strategic failure by December 1941 despite capturing vast areas.[92] Parallel to military campaigns, the Nazi regime implemented the Holocaust, a systematic genocide orchestrated by German state apparatus including SS units and Einsatzgruppen, resulting in approximately 6 million Jewish deaths through mass shootings, ghettos, and extermination camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau, where Zyklon B gas chambers enabled industrialized killing from 1942 onward.[93] An additional 5-6 million non-Jews, including Roma, Poles, Soviet POWs, and disabled individuals, perished under Nazi racial policies.[94] German society exhibited broad acquiescence to Nazi rule, with historical analyses indicating that while active resistance groups like the White Rose were marginal and suppressed, a majority accepted core racial and authoritarian tenets, evidenced by sustained electoral support and minimal widespread opposition until late-war defeats.[95] Churches and military elites largely conformed, though pockets of dissent existed, such as the July 20, 1944, bomb plot by officers including Claus von Stauffenberg. The home front shifted to total war under Joseph Goebbels' 1943 call, mobilizing women and resources, but endured severe Allied strategic bombing; campaigns like the RAF's area bombing killed an estimated 500,000 German civilians, devastating cities such as Dresden in February 1945, where firestorms caused 25,000 deaths.[96] Military defeats mounted after Stalingrad in February 1943, where the Sixth Army surrendered with 91,000 survivors from 300,000, and the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944. Total German military deaths reached approximately 5.3 million, with civilian losses around 1-2 million from bombing and expulsions. Berlin fell on May 2, 1945, followed by Hitler's suicide on April 30 and unconditional surrender on May 8, ending the Nazi era amid widespread devastation and the regime's collapse.Post-1945 Division, Denazification, and Reunification

At the conclusion of World War II, Nazi Germany's unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, led to its division into four occupation zones administered by the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Soviet Union, as agreed at the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences.[97][98] The western zones encompassed roughly two-thirds of Germany's pre-war territory, while the Soviet zone covered the eastern third; Berlin, deep within the Soviet sector, was similarly partitioned into four sectors. This arrangement, intended as temporary, solidified amid emerging Cold War tensions, with the Soviets extracting reparations estimated at $14 billion in industrial assets and forcing labor from their zone.[97] Between 1944 and 1950, approximately 12 million ethnic Germans were expelled or fled from territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, including Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the Baltic states, resulting in 500,000 to 2 million deaths from violence, disease, and exposure during chaotic transfers approved at Potsdam but poorly managed.[99][100] These displacements, driven by Allied policies to redraw borders and homogenize populations, overwhelmed receiving zones and contributed to postwar demographic strains. Denazification, a core Allied objective, sought to eradicate Nazi ideology from German institutions through purges, trials, and re-education. Implemented via the 1945 Control Council Law No. 10, it required questionnaires assessing individuals' Nazi involvement, processing over 8.5 million in the western zones by 1946.[101] Categories ranged from major offenders (tried at Nuremberg) to nominal party members, with initial internments of 100,000 in the West, though many were released by 1948 amid labor shortages and Cold War realignments.[102] Soviet efforts emphasized class-based purges but selectively retained ex-Nazis for anti-Western roles, such as in the Stasi; overall, the process proved uneven and incomplete, with estimates that 20-30% of West German civil servants had Nazi ties by the 1950s, reflecting pragmatic reintegration over ideological purity.[101][102] Western leniency, criticized in some historical analyses for prioritizing reconstruction, allowed figures like Hans Globke—a drafter of Nuremberg Laws—to hold senior positions, underscoring causal trade-offs between de-Nazification rigor and economic recovery. By 1949, ideological divides prompted separate state formations: the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) on May 23, under the Grundgesetz (Basic Law), establishing a parliamentary democracy with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, and the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany) on October 7 as a Soviet satellite.[103][104] The FRG's social market economy, pioneered by Ludwig Erhard via 1948 currency reform and price liberalization, ignited the Wirtschaftswunder, with annual GDP growth averaging 8% from 1950-1960, industrial output quadrupling, and unemployment falling from 10% to under 1% by 1960.[105] In contrast, the GDR's centralized planning and collectivization yielded stagnation, with living standards 40-50% below the West by the 1950s, fueling a brain drain of 3.5 million refugees to the FRG by 1961—20% of the East's population.[105] To stem this exodus, GDR leader Walter Ulbricht ordered the Berlin Wall's construction on August 13, 1961, erecting barbed wire and concrete barriers enclosing West Berlin, fortified by a 100-meter "death strip" patrolled by guards. Over 28 years, at least 140 people died attempting crossings, including shootings and drownings, symbolizing communist repression. Cracks emerged in 1989 amid Gorbachev's perestroika, economic collapse, and mass protests; Erich Honecker resigned in October, and on November 9, Politburo member Günter Schabowski announced open borders, leading to the Wall's breaching by jubilant crowds.[106] Reunification accelerated post-Wall: GDR elections in March 1990 favored pro-unity parties, followed by monetary union in July adopting the Deutsche Mark, and the Unification Treaty on August 31 integrating the East into the FRG's system.[107] The Two Plus Four Treaty on September 12 ended Allied rights, confirmed Oder-Neisse borders, and limited Bundeswehr to 370,000 troops, enabling sovereignty.[108] Effective October 3, 1990, reunification joined 16 million East Germans to the West, costing the FRG over 2 trillion Deutsche Marks in transfers by 2000 for infrastructure equalization, though East-West productivity gaps persist, with eastern GDP per capita at 75% of western levels as of 2020.[107] This process, driven by economic disparity and Soviet withdrawal rather than conquest, marked the Cold War's end in Europe without widespread violence.[108]Federal Republic from 1990 to Present