Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hanbok

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Material | Diverse |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Korea |

| Introduced | At latest the Goguryeo period |

| North Korean name | |

| Hangul | 조선옷 |

| Hanja | 朝鮮옷 |

| RR | joseonot |

| MR | chosŏnot |

| South Korean name | |

| Hangul | 한복 |

| Hanja | 韓服 |

| RR | hanbok |

| MR | hanbok |

The hanbok (Korean: 한복; Hanja: 韓服; lit. Korean dress) is the traditional clothing of the Korean people.

The term hanbok literally means Korean clothing. In South Korea and internationally, it is the standard term for the attire. North Koreans refer to the clothes as chosŏnot (조선옷; lit. Korean clothes).[1] The attire is also worn in the Korean diaspora.[2] Koryo-saram—ethnic Koreans living in the lands of the former Soviet Union—also retained a hanbok tradition.[3]

The hanbok is fundamentally composed of a jeogori (top), baji (trousers), chima (skirt), and the po (coat). While this core arrangement has remained consistent for a long time, its length, width, and shape have gradually changed over time.

Koreans have worn hanbok since antiquity. The earliest visual depictions of hanbok can be traced back to the Three Kingdoms of Korea period (57 BCE to 668 CE) with roots in the ancestors of the Koreanic peoples of what is now northern Korea and Manchuria. The clothes are also depicted on tomb murals from the Goguryeo period (4th to 6th century CE), with the basic structure of the hanbok established since by at least this time.[4] The ancient hanbok, like modern hanbok, consisted of a jeogori, baji, chima, and po.

Some interpretations suggest that certain elements of the hanbok, such as specific colors or patterns, were influenced by traditional folk beliefs or shamanism.[5] For thousands of years, many Koreans have preferred white hanbok, a color considered pure and symbolizing light and the sun.[6][7][8][9] In some periods, commoners (seomin) were forbidden from wearing certain colorful hanbok regularly.[10]: 104 [11][12] However, during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) and the Japanese occupation of Korea (1910–1945), there was also an attempt to ban white clothes and to encourage non-bleached dyed clothes, which ultimately failed.[13][14][15][16]

Modern hanbok are typically patterned after the hanbok worn in the Joseon period,[5] especially those worn by the nobility and royalty.[17]: 104 [11]

There is some regional variation in hanbok design between South Korea and North Korea, which arose from their relative isolation in the late 20th century. Communities of ethnic Koreans abroad, including those in China, also maintain their own hanbok traditions, all of which are rooted in the shared cultural heritage of Korea. Since the 1990s, increased cultural exchange has led to these different styles converging once again.

Nowadays, contemporary Koreans wear hanbok for formal or semi-formal occasions and for events such as weddings, festivals, celebrations, and ceremonies. In 1996, the South Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism established Hanbok Day to encourage South Korean citizens to wear the hanbok.[18]

Etymology

[edit]The term hanbok came into use relatively recently, beginning in the 1800s. It is connectedwith the historical context in which it appeared.

The term emerged in the late Joseon period, when the Empire of Japan and other western countries competed to place Korea under their own sphere of influence. The first known use of the term is in an 1881 document from the late Joseon period entitled Chŏngch'iilgi (《정치일기》).[19][20] There, hanbok is used to distinguish Korean clothing from Japanese and Western-style clothing. Hanbok was again used in an 1895 document to distinguish between Korean and Japanese clothing. These two usages predate the Korean Empire's popularization of the use of the hanja character Han (Hanja: 韓) to describe the Korean people.

Beginning in 1900, Korean newspapers used the hanja character Han in words that described Korean clothing, such as Han'gugŭibok (한국의복), Han'gugyebok (한국예복), and Taehannyŏbok (대한녀복). Hanbok was used in a 1905 newspaper article to describe the clothing of one of the righteous armies. Other words with similar meanings, such as uri-ot (우리옷) and chosŏn-ot (조선옷), were concurrently used.

Since the division of Korea, South Korea has preferred the term hanbok while North Korea has preferred the term Chosŏn-ot. This reflects the general trend of South Korea's preference for the term Han and North Korea's for Chosŏn.

Components and design

[edit]

- A diagram of the hanbok's anatomy

- 1. hwajang

- 2. godae

- 3. somae buri

- 4. somae

- 5. goreum

- 6. u

- 7. doryeon

- 8, 11. jindong

- 9. gil

- 10. baerae

- 12. git

- 13. dongjeong

For women, traditional hanbok consists of the jeogori (top) and the chima (skirt). The ensemble is often known as chima jeogori. For men, hanbok consist of jeogori and loose-fitting baji (trousers).[21]

There are also a variety of vests, jackets and coats on top of this ensemble. For women, there are Jangsam, Dansam, Wonsam, and more. For men, some examples are durumagi, dopo, Danryeong-ui, Joong-chimak, Sochang-ui, Daechang-ui, etc.

Jeogori

[edit]The jeogori (저고리) is the basic upper garment of the hanbok, worn by both men and women. It covers the arms and upper part of the wearer's body.[22][23]

There are various styles and types of jeogori varying in fabric, sewing technique, and shape.[24][25] The basic form of a jeogori consists of gil, git, dongjeong, goreum and sleeves. Gil (길) is the large section of the garment on both front and back sides, and git (깃) is a band of fabric that trims the collar. Dongjeong (동정) is a removable white collar placed over the end of the git and is generally squared off. The goreum (고름) are fabric-strings that tie the jeogori.[21] Women's jeogori may have kkeutdong (끝동), a different colored cuff placed at the end of the sleeves. Contemporary jeogori are presently designed with various lengths.

Goreum

[edit]Goreum (고름) refers to the strings that fasten clothes together.

Traditionally, there are many types of goreum. Fabric goreum was potentially used since Gojoseon. They were originally practical but often decorative. Silla had regulations against types of Dae (belts) and decorative goreum for each Golpoom. Southern parts of Korea, including Silla, had a colorful goreum on the front of the neck, which influenced Yayoi culture. Parts of Goguryeo style had a fabric goreum loop around the waist with a decorative ribbon to the side like a belt. Generally, thin and short ones were used on the inside and more decorative, colourful ones were used on the outside. Since the early form of the jeogori was usually wrapped across the front, the outside goreum was placed on the side of the wearer, below the underarm. Starting in Joseon dynasty, the goreum slowly moved to the front of the jeogori. In the 20th century, the goreum became the commonly known long and wide decorative ribbons on the front of the jeogori and was coined the Ot-goreum.

Danchu

[edit]Danchu (buttons) can also be used as an alternative to goreum.

There are many types of danchu. One example is the maedeup-danchu which was often used to keep symmetrical collars together in the front and used for practical uses on military uniforms and court uniforms. They have long horizontal lines on either side like Manchurian buttons or look like a ball and lasso. Magoja-danchu are often big decorative metal, gems or stones buttons usually on jjokki (vest).[26]

Chima

[edit]Chima (치마) refers to "skirt", and is also called sang (裳) or gun (裙) in hanja.[27][22][24] The underskirt, or petticoat layer, is called sokchima. Chima-malgi is the waistband that trims the top of the chima. Chima was typically made from rectangular panels that were pleated or gathered into the chima-malgi (waistband).[28] This waistband also had goreum strings for fastening the skirt around the body.[29] From the Goguryeo to Joseon periods, chima have been striped, pleated, patchworked, gored[22] and decorated with uniquely Korean geumbak(gold leaf) patterns. This traditional Korean technique of stamping gold leaf with woodblocks was applied to the garments of royalty and nobility and has its origins even before the Three Kingdoms period.[30]

Sokchima was largely made in a traditional way until the early 20th century when shoulder straps were added,[31] later developing into a sleeveless bodice or "reformed" petticoat called eokkaeheorichima.[32] By the mid-20th century, some outer chima also gained a sleeveless bodice, which was then covered by the jeogori.[33][unreliable source?][34][unreliable source?]

Baji

[edit]Baji (바지) refers to the bottom part of the men's hanbok. It is the term for "trousers" in Korean. Compared to western style pants, baji does not fit tightly. The roomy design is aimed at making the clothing ideal for sitting on the floor and an ethnic style that dates back to the Three Kingdoms period.[35]

It functions as modern trousers do and the term baji is commonly used in Korea to refer to every kind of pants.

The baji-malgi is a waistband of the baji that has a long string of goreum.

Baji can be unlined trousers, leather trousers, silk pants, or cotton pants, depending on the style of dress, sewing method, embroidery and so on.

Sokgot

[edit]Sokgot (속곳) is a collective noun for various types of traditional Korean undergarments. They were worn as part of a hanbok before the import of Western-style underwear. Women usually wore several layers of undergarments, the more layers they had the richer they were.[36] Undergarments were considered very important, thus it happened that the quality and material of the underwear were better than that of the visible outer layers.[37]

Deot-ot

[edit]Deot-ot refers to a category of outer layers worn on top of the jeogori. There are many varieties other than the ones listed here.

Po

[edit]Po (포; 袍) is a generic term referring to an outer robe or overcoat. There are two general types of po, the Korean type and the Chinese type.[38] The mainstream Korean type is a common style from the Three Kingdoms of Korea period, and it is used in the modern day.[22][38]

Durumagi is a type of po that was worn for protection against the cold. It has been widely worn as an outer robe over jeogori and baji. It is also called jumagui, juchaui, or juui.[27][22][39]

The word Durumagi in Korean means "closed all around." Originating from the clothing styles of northern peoples, it evolved from Korea's traditional Po (outer robe) system, which dates back to the Goguryeo Kingdom.

The Po of the Goguryeo era had a decorative seon (trim) and was fastened with a tti (belt), in accordance with the style of the time. In contrast, the later Durumagi has little difference except that it lacks the trim and is instead tied with chest goreum (ribbons).

The outer robes of the Baekje and Silla kingdoms were also similar to the Durumagi. Evidence of this can be seen in historical paintings, such as the depiction of a Baekje envoy in the Liang Dynasty's "Portraits of Periodical Offerings" and a Silla envoy in a mural of foreign envoys from the Tang Dynasty's Tomb of Li Xian. In these portraits, the envoys are wearing wide-sleeved robes that are slightly longer than a jeogori (upper jacket), indicating that all three kingdoms shared a similar style of garment.[40]

Baeja refers to sleeveless outer garments that are worn on top of inner garments. It can be different lengths, short to long. Kwaeja is interchangeable with baeja, but Kwaeja often refers to men's clothing. The Chinese type consist of different types of po from mainland China.[38]

Dapho

[edit]The dapho (답호; 褡護) is a short-sleeved men's outer garment, often part of military uniform or official uniform. It was adopted from the Mongol Yuan dynasty during the Goryeo period.

Bigap

[edit]A sleeveless outer garment that was derived from Mongolian clothing worn during the Goryeo period.[41]

Banbi

[edit]Banbi (반비; 半臂, lit. 'half sleeve') are a type Hanfu that originated from the Tang dynasty. Banbi refers to a variety of short-sleeved garments worn on top of inner garments, typically the Yuanling pao (Chinese: 圓領袍, 'round collar robe'). Numerous outer half-sleeved Banbi can be seen in ancient Tang-era paintings, murals, and statues.[42]

Magoja

[edit]Magoja (마고자) does not have a git, the band of fabric trimming the collar.[21] The magoja for men sometimes has seop (섶, overlapped column on the front) and is longer than women's magoja, with both sides open at the bottom. A magoja can be made of silk and often adorned with danchu which are usually made from amber. In men's magoja, buttons are attached to the right side, as opposed to the left as in women's magoja.[39]

It was introduced to Korea after Heungseon Daewongun, the father of King Gojong, returned from his political exile in Tianjin in 1887.[39][43] Long-sleeved magoja were derived from the magwae he wore in exile because of the cold climate there. Owing to its warmth and ease of wear, magoja became popular in Korea. It is also called "deot jeogori" (literally 'an outer jeogori') or magwae.[39]

Jokki

[edit]Jokki (조끼) is a type of vest, while magoja is an outer jacket. The jokki was created around the late Joseon dynasty, as Western culture began to affect Korea.

Children's hanbok

[edit]

Traditionally, Kkachi durumagi (literally 'a magpie's overcoat') were worn as seolbim (설빔), new clothing and shoes worn on the Korean celebration of Korean New Year, while at present, it is worn as a ceremonial garment for dol, the celebration for a baby's first birthday.[44][45] It is a children's colorful overcoat.[46] It was worn mostly by young boys.[47] The clothes is also called obangjang durumagi which means "an overcoat of five directions".[44] It was worn over jeogori (a jacket) and jokki (a vest), while the wearer could put jeonbok (a long vest) over it. Kkachi durumagi was also worn along with headgear such as bokgeon (a peaked cloth hat),[48][49] hogeon (peaked cloth hat with a tiger pattern) for young boys or gulle (decorative headgear) for young girls.[22][need quotation to verify][50]

Foreign influences in design

[edit]The clothing of Korea's rulers and aristocrats after CE 7, was influenced by both indigenous and foreign styles, including influences from various Chinese dynasties.

This led to the adoption of specific garments such as the simui, a robe for Confucian scholars, from the Song dynasty.[51]

The gwanbok (관복 or 단령), worn by male officials was generally adopted from or influenced by the court clothing system of the Tang,[52][53] Song,[53] and Ming dynasties.[54]

While most court clothing for royal women was indigenous, foreign influence can be seen in a few specific robes. For instance, the Dangui is considered a unique Joseon garment despite its name implying Tang origins, whereas the Wonsam was more clearly adapted from Ming dynasty styles. Both, however, were transformed to fit a distinctly Joseon aesthetic.

The cheollik , which originated in Mongolia, was described in 15th century Korea as gifts from the Ming dynasty or as military uniforms.[55]

The cultural exchange was also bilateral and Goryeo hanbok had a cultural influence on some clothing of Yuan dynasty worn by the upper class (i.e. the clothing worn by Mongol royal women's clothing[56] and in the Yuan imperial court[57]).[58]

Commoners were less influenced by these foreign fashion trends, and mainly wore a style of indigenous clothing distinct from that of the upper classes.[59]

Design and social position

[edit]

The choice of hanbok can also signal social position. Bright colors, for example, were generally worn by children and girls, and muted hues by middle-aged men and women. Unmarried women often wore yellow jeogori and red chima while matrons wore green and red, and women with sons donned navy. The upper classes wore a variety of colours. Contrastingly, commoners were required to wear white, but dressed in shades of pale pink, light green, gray and charcoal on special occasions.

The material of the hanbok also signaled status. The upper classes dressed in hanbok of closely woven ramie cloth or other high grade lightweight materials in warmer months and of plain and patterned silks throughout the remainder of the year. Commoners, in contrast, were restricted to cotton.

Patterns were embroidered on hanbok to represent the wishes of the wearer. Peonies on a wedding dress, represented a wish for honor and wealth. Lotus flowers symbolized a hope for nobility, and bats and pomegranates showed the desire for children. Dragons, phoenixes, cranes and tigers were only for royalty and high-ranking officials.[60] In addition, special variants were made for officials and shamans.[35]

History

[edit]Three Kingdoms of Korea

[edit]

The earliest visual depictions of hanbok can be traced back to the Three Kingdoms of Korea period (57 BCE to 668 CE).[61][62][63][64] The origin of ancient hanbok can be found in the ancient clothing of what is now today's Northern Korea and Manchuria.[65]

A prevailing theory traces the origin of the hanbok of antiquity to the nomadic clothing of the Eurasian Steppes (Iranian Scythian clothing), spanning across Siberia from western Asia to Northeast Asia, interconnected by the Steppe Route.[66][67][68] Reflecting its nomadic origins in western and northern Asia, ancient hanbok shared structural similarities with hobok type clothing of the nomadic cultures in East Asia, designed to facilitate horse-riding and ease of movement,[19][69][70] such as the use of trousers and jacket for male clothing and the use of left closure in its jacket.[71]

However, although the ancient hanbok reflects some similarity with the Iranian Scythian clothing, a number of differences between the two types of clothing have also been observed which led associated professor Youngsoo Chang from the Department of Cultural Properties in Gyeongju University in 2020 to argue that the theory about Iranian Scythian clothing being the archetype of the ancient hanbok, a theory accepted as common knowledge in Korean academia, may have to be revised.[71]

It is also important to note the evidence found in Goguryeo tomb murals. These murals from the ancient Korean kingdom were primarily painted in Jian and Pyongyang, the kingdom's second and third capitals, respectively, from the mid-fourth to the mid-seventh centuries. These murals vividly depict the people of Goguryeo on a grand scale and with unmatched detail.[72]: 15

Goguryeo tomb murals exhibit different characteristics by region. Murals found in Jian, Manchuria, the earlier capital, primarily depict Goguryeo's indigenous customs, morals, and daily life. In contrast, murals from Pyongyang on the Korean Peninsula, the later capital, reflect a broader cultural interaction. While these murals are fundamentally Goguryeo in character, they also contain depictions of Chinese figures in Han dynasty-style clothing, who are presumed to be linked to the Han commanderies that governed the region at the end of the Gojoseon period. Furthermore, certain elements, such as the costumes of the maids in the Gamsinchong tomb, show similarities to the attire of the northern conquest dynasties of China that were contemporary with Goguryeo, specifically during the Northern and Southern, Sui, and Tang periods.[72]: 15

Goguryeo

[edit]Early forms of hanbok can be seen in the art of Goguryeo tomb murals in the same period from the 4th to 6th century CE.[64][65][70][73] Trousers, long jackets and twii (a sash-like belt) were worn by both men and women. Women wore skirts on top of their trousers. These basic structural and features of hanbok remain relatively unchanged to this day,[74] except for the length and the ways the jeogori opening was closed as over the years.[63] The jeogori opening was initially closed at the center front of the clothing, similar to a kaftan or closed to the left, before closing to the right side eventually became mainstream.[63] Since the sixth century CE, the closing of the jeogori at the right became a standard practice.[63] The length of the female jeogori also varied.[63] For example, women's jeogori seen in Goguryeo paintings of the late 5th century CE are depicted shorter in length than the man's jeogori.[63]

In early Goguryeo, the jeogori jackets were hip-length Persian-styled Kaftan tunics belted at the waist, and the po overcoats were full body-length Kaftan robes also belted at the waist. The pants were roomy, bearing close similarities to the pants found at Xiongnu burial site of Noin Ula.[citation needed] Some Goguryeo aristocrats wore roomy pants with tighter bindings at the ankle than others, which may have been status symbols along with length, cloth material, and colour. Women sometimes wore pants or otherwise wore pleated skirts. They sometimes wore pants underneath their skirts.[75]

Two types of hwa (shoes) were used, one covering only the foot, and the other covering up to the lower knee.[citation needed]

During this period, the conical hat and its similar variants, sometimes adorned with long bird feathers,[76] were worn as headgear.[68] Bird feather ornaments, and bird and tree motifs of golden crowns, are thought to be symbolic connections to the sky.[citation needed]

-

A Goguryeo man in a hunting attire from Capital Cities and Tombs of the Ancient Koguryo Kingdom, 5th century CE, Jilin province, China

-

Goguryeo servants wearing a Chima (skirt) and a durumagi (over coat), Goguryeo mural paintings in Jilin province, China, 5th-century CE

-

A noblewoman in traditional Goguryeo hanbok. 5th century, Detail from a mural in the Susan-ri Tomb, Pyongyang.

-

The Goguryeo jeogori was a hip-length jacket with narrow sleeves. It had a straight, crossed collar and was tied shut with a belt at the waist. The collar and cuffs were often decorated with a different colored trim.

The Goguryeo period royal attire was known as ochaebok.[63] The precursor of what is now known as the durumagi was introduced during the Goguryeo period as a long coat worn by Northern peoples[63] Originally the durumagi was worn by the upper class of Goguryeo for various ceremonies and rituals. It was later modified and worn by the general population.[63] In Muyong-chong murals of Goguryeo, there are male dancers in short jeogori with long flexible sleeves and female dancers wearing a type of durumagi (a Korean over coat) with long flexible sleeves, all performing a dance.

North-South States period

[edit]In the North-South States Period (698–926 CE), the fundamental structure of clothing from the Three Kingdoms period was largely maintained.

Silla and Balhae adopted dallyeong, a circular-collar robe from the Tang dynasty of China.[77][78] The style itself was influenced by hobok(胡服), nomadic clothing from Western and Central Asia.

In Silla, the dallyeong was introduced by Muyeol of Silla in the second year of queen Jindeok of Silla.[78][52] The dallyeong style from China was used as gwanbok, a formal attire for government officials, grooms, and dragon robe, a formal attire for royalty until the end of Joseon.[78]

United Silla

[edit]In 668 CE, the Silla Kingdom unified the Three Kingdoms, though its control did not extend to the northern territories.

-

Reconstruction of Silla king's and queen's attire

-

Gold waist belt used by royalty of Silla.

-

Women figures wearing Tang-dynasty style clothing, Silla

The Unified Silla (668-935 CE) was the golden age of Korea. In Unified Silla, various silks, linens, and fashions were imported from Tang China and Persia. In the process, the latest fashion trends of Luoyang which included Xianbei-influenced dress styles, the second capital of Tang, were also introduced to Korea, where the Korean silhouette trended towards the Western Empire silhouette.[dubious – discuss]

King Muyeol of Silla personally travelled to the Tang dynasty to voluntarily request for clothes and belts; it is however difficult to determine which specific form and type of clothing was bestowed although Silla requested the bokdu (幞頭; a form of hempen hood during this period), danryunpo (團領袍; round collar gown), banbi, baedang (䘯襠), and pyo (褾).[52][dubious – discuss]

Based on archaeological findings, it is assumed that the clothing which was brought back during Queen Jindeok rule are danryunpo and bokdu.[52] The bokdu also become part of the official dress code of royal aristocrats, court musicians, servants during the reign of Queen Jindeok; it continued to be used throughout the Goryeo dynasty.[79] The general public of Silla continued to wear their own traditional clothing.[52]

In 664 CE, Munmu of Silla decreed that the costume of the queen should resemble the costume of the Tang dynasty; and thus, women's costume also accepted the costume culture of the Tang dynasty.[52] Women also sought to imitate the clothing of the Tang dynasty through the adoption of shoulder straps attached to their skirts and wore the skirts over the jeogori.[52][80] The influence of the Tang dynasty during this time was significant and the Tang court dress regulations were adopted in the Silla court.[75][81] The clothing of the Tang dynasty introduced in Silla made the clothing attire of Silla Court extravagant, and due to the extravagance, King Heundeog enforced the Tang clothing prohibition during the year 834 CE.[52]

Balhae

[edit]Balhae (698–926 CE) was a kingdom founded in Manchuria by the Goguryeo refugees and the Mohe people, a northern Tungusic group who were ancestors of the Jurchens.

Balhae imported many various kinds of silk and cotton cloth from the Tang and diverse items from Japan including silk products and ramie. In exchange, Balhae would export fur and leather.

The clothing culture of Balhae was heterogeneous; it was not only influenced by the Tang dynasty but also had inherited Goguryeo and indigenous Mohe people elements.[82]

Early Balhae officials wore clothing appeared to continue the Three Kingdoms period tradition.[82] However, after Mun of Balhae, Balhae started to incorporate elements from the Tang dynasty, which include the putou and round collared gown for its official attire.[82] Male everyday clothing was similar to Gogoryeo clothing in terms of its headgear; i.e. hemp or conical hats with bird feathers; they also wore leather shoes and belts.[82] Women clothing appears to have adopted clothing from Tang dynasty (i.e. upper garment with long sleeves which is partially covered by long skirts and shoes with curled tips to facilitate walking) but also wore the ungyeon (Yunjuan; a silk shawl) which started to appear after the demise of the Tang dynasty. The Ungyeon use is unique to late Balhae period and is distinctive from the shawl which was worn by the women of the Tang dynasty.[82]

People from Balhae also wore fish-skin skirts and sea leopard leather tops to keep warm.[82]

Goryeo dynasty

[edit]During the Goryeo period, the Tang-influenced style of wearing the skirt over the top started to fade, leading to the revival of the native Goguryeo style(wearing the top over the skirt) within the aristocrat class.[83][84] The way of wearing the top under the chima did not disappear in Goryeo and continued to coexist with the indigenous Goguryeo style of wearing of the top over skirt throughout the entire Goryeo dynasty; this Tang-style influenced fashion continued to be worn until the early Joseon dynasty.[85][dubious – discuss]

Hanbok went through significant changes under Mongol rule. After the Goryeo dynasty signed a peace treaty with the Mongol Empire in the 13th century, Mongolian princesses who married into the Korean royal house brought with them Mongolian fashion which began to prevail in both formal and private life.[52][67][86][87]

A total of seven women from the Yuan imperial family were married to the kings of Goryeo.[57] The Yuan dynasty princess followed the Mongol lifestyle who was instructed to not abandon the Yuan traditions in regards to clothing and precedents.[52] As a consequence, the clothing of Yuan was worn in the Goryeo court and impacted the clothing worn by the upper-class families who visited the Goryeo court.[52] The Yuan clothing culture which influenced the upper classes and in some extent the general public is called Mongolpung.[57]

And King Chungryeol, as an imperial son-in-law of the Mongol Empire, married the princess of Yuan announcing a royal edict directing the aristocracy to change into Mongol clothing.[52] After the fall of the Yuan dynasty, only Mongol clothing which were beneficial and suitable to Goryeo culture were maintained while the others disappeared.[52] As a result of the Mongol influence, the chima skirt was shortened, and jeogori was hiked up above the waist and tied at the chest with a long, wide ribbon, the goreumg (an extending ribbon tied on the right side) instead of the twii (i.e. the early sash-like belt) and the sleeves were curved slightly.[citation needed]

The cultural exchange was also bilateral and Goryeo had cultural influence on the Mongols court of the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368); one example is the influence of Goryeo women's hanbok on the attire of aristocrats, queens, and concubines of the Mongol court which occurred in the capital city, Khanbaliq.[88][89][90]However, this influence on the Mongol court clothing mainly occurred in the last years of the Yuan dynasty.[91][57]

According to Hyunhee Park: "Like the Mongolian style, it is possible that this Koryŏ style [Koryŏ yang] continued to influence some Chinese in the Ming period after the Ming dynasty replaced the Yuan dynasty, a topic to investigate further."[92]

This cultural phenomenon is strongly associated with the rise of the Goryeo-born Empress Gi, who held significant power during the Zhizheng era (1341–1370), the period specified in the text. Her influence and the large number of Goryeo court ladies she employed are considered key factors in the popularization of Goryeoyang within the Yuan elite.

This trend, particularly prominent in the late Yuan dynasty, is vividly documented in the Chinese historical record Xu Zizhi Tongjian (Volume 214). According to the text, the presence of numerous Goryeo women in the palace, from empresses to court servants, led to a situation where acquiring a Goryeo woman became a status symbol for a noble family. The record states that as a result of their widespread presence, "clothing, boots, hats, and other goods from all regions came to be modeled after the Goryeo style, creating a craze that swept the land."[93]

Throughout the Yuan dynasty, many people from Goryeo were forced to move into the Yuan; most of them were kongnyo (literally translated as "tribute women"), eunuchs, and war prisoners.[57][94] About 2000 women from Goryeo were sent to Yuan as kongnyo against their will.[57] Although women from Goryeo were considered very beautiful and good servants, most of them lived in unfortunate situations, marked by hard labour and sexual abuse.[57] However, this fate was not reserved to all of them; and one Goryeo woman became the last Empress of the Yuan dynasty; this was Empress Gi who was elevated as empress in 1365.[57] Most of the cultural influence that Goryeo exerted on the upper class of the Yuan dynasty occurred when Empress Gi came into power as empress and started to recruit many Goryeo women as court maids.[57]

The influence of Goryeo on the Mongol court's clothing during the Yuan dynasty was dubbed as Goryeoyang ("the Goryeo style") and was rhapsodized by the Late Yuan dynasty poet, Zhang Xu, in the form of a short banbi (半臂) with square collar (方領).[57][56] However, so far, the modern interpretation on the appearance of Mongol royal women's clothing influenced by Goryeo is based on authors' suggestions.[56]

The influence of Goryeo fashion was not limited to the Yuan dynasty; it also had a significant impact in Ming China. A notable example of this cultural transmission is the widespread popularity of the mamigun(horsehair skirt, 馬尾裙), a Joseon(Goryeo)-style petticoat designed to add volume to the outer skirt.

According to the Shu yuan za ji, a 15th-century text by the Ming scholar Lu Rong(陸容), the mamigun was first imported from Joseon and quickly became a highly sought-after fashion item in the capital. The record details its social diffusion, beginning with wealthy merchants and aristocrats before spreading to military officials and, by the late Chenghua era(1465–1487), becoming common attire even among the highest-ranking ministers of the Ming court.[95]

Lu Rong notes that the skirt was worn for its aesthetic appeal, creating a flared silhouette that was considered visually pleasing. The trend became so pervasive that some officials, such as Grand Secretary Wan An, wore it year-round. The text describes the fashion as "decadent and bizarre" (yao, 妖), and its popularity ultimately led to an official prohibition being enacted at the beginning of the Hongzhi era (1488–1505). This record from a Chinese source provides clear evidence of a "Joseon style" (Joseon-yang) creating a major fashion trend within Ming China's elite society.[96]

-

Details of the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara painting shows a group of nobles (possibly the donors) dress in court clothing, Goryeo painting[97]

-

Chima-jeogori, a noblewoman's attire in Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara, Goryeo dynasty painting, 1323 CE[98]

-

Court ladies wearing the Tang and Song dynasty style clothing, from the painting Royal Palace Mandala, late Goryeo

-

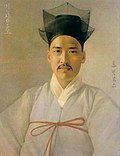

Portrait of Lady Jo ban (1341–1401 CE), Goryeo dynasty

-

Portrait of Yi Je-hyeon (1287–1367 CE) of the Goryeo dynasty, wearing simui

In Goryeo Buddhist paintings, the clothing and headwear of royalty and nobles typically follow the clothing system of the Song dynasty.[99] The Goryeo painting "Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara", for example, is a Buddhist painting which was derived from both Chinese and Central Asian pictorial references.[100] On the other hand, the clothing worn in Yuan dynasty rarely appeared in paintings of Goryeo.[99]

The Song dynasty system was later exclusively used by Goryeo Kings and Goryeo government officials after the period when Goryeo was under Mongol rule (1270 –1356).[98] However, even in the Buddhist painting of the late Goryeo, such as the Royal Palace Mandala, the courting ladies are depicted in Tang and Song dynasty-style court dress clothing, which is a different style from the Mongol Yuan court.[98]

Joseon dynasty

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

The hanbok of the Joseon period was fundamentally a continuation of the sartorial traditions established during the preceding Goguryeo and Goryeo dynasties. The basic structure, consisting of the jeogori (jacket), baji (trousers) for men, and chima (skirt) for women, was inherited and served as the foundation upon which Joseon-era styles evolved.[101]

Neo-Confucianism as the ruling ideology in Joseon was established by the early Joseon dynasty kings; this led to the dictation of clothing style worn by all social classes in Joseon (including the dress of the royals, the court members, the aristocrats and commoners) in all types of occasions, which included wedding and funerals.[102] Social values such as the integrity in men and chastity in women were also reflected in how people would dress.[102] After the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) or Imjin War, economic hardship on the peninsula may have influenced the closer-fitting styles that use less fabric.[103]

Women's everyday wear

[edit]Early Joseon continued the women's fashion for baggy, loose clothing, such as those seen on the mural from the tomb of Bak Ik (1332–1398);[104] the murals from the tomb of Bak Ik are valuable resources in Korean archaeology and art history for study of life and customs in early Joseon.[105] the women of the lower class generally imitated the upper-class women clothing.[106]

During the Joseon dynasty, the chima (skirt) adopted fuller volume, while the jeogori (upper garment) took a more tightened and shortened form, features quite distinct from the hanbok of earlier eras like Goguryeo and Goryeo, when the chima had a more natural A-line silhouette and the jeogori was baggy and long, reaching well below waist level.

In the 15th century, neo-Confucianism was very rooted in the social life of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries which led to the strict regulation of clothing (including fabric use, colours of fabric, motifs, and ornaments) based on status.[107] Neo-Confucianism also influenced women's wearing of full-pleated chima, longer jeogori, and multiple layers of clothing in order to never reveal skin.[108] In the 15th century, women started wearing full-pleated chima, which completely hid the body lines, and longer-length jeogori.[109][108][110] The 15th-century style was heavily influenced by the prevailing Neo-Confucian ideology from China.[108]

-

15th century lady

-

15th century lady

However, by the 16th century, the jeogori had shortened to the waist and appears to have become closer fitting, although not to the extremes of the bell-shaped silhouette of the 18th and 19th centuries.[111][112][103] In the 16th century, women's jeogori was long, wide, and covered the waist.[113] The length of women's jeogori gradually shortened: it was approximately 65 cm in the 16th century, 55 cm in the 17th century, 45 cm in the 18th century, and 28 cm in the 19th century, with some as short as 14.5 cm.[113] A heoritti (허리띠) or jorinmal (졸잇말) was worn to cover the breasts.[113] The trend of wearing a short jeogori with a heoritti was started by the gisaeng and soon spread to women of the upper class.[113]

During the 17th and 18th centuries the fullness of the skirt was concentrated around the hips, thus forming a silhouette similar to Western bustles. In the 18th century, the jeogori became very short to the point that the waistband of the chima was visible; this style was first seen on female entertainers at the Joseon court.[106] The jeogori continued to shorten until it reached modern times jeogori-length; i.e. just covering the breasts.[108] The fullness of the skirt reached its extreme around 1800. During the 19th century fullness of the skirt was achieved around the knees and ankles thus giving the chima a triangular or an A-shaped silhouette, which is still the preferred style to this day. Many undergarments such as darisokgot, soksokgot, dansokgot, and gojengi were worn underneath to achieve desired forms.

-

Women's hanbok consists of chima skirt and jeogori shirt by Shin Yunbok

-

Full skirt and tight jeogori were considered fashionable (18th century)

-

Soksokgot, similar to a petticoat, is shown under the woman's skirt (18th century)

-

Dancing together with two swords

-

Young people's outgoing

Late Joseon period, Among women of the common and lowborn classes, a practice emerged in which they revealed their breasts by removing a cloth to make breastfeeding more convenient.[114] As there was an excessive preference for boys in the Joseon dynasty, the deliberate exposure of breast eventually became a cultural practice and an indicator of women's pride and status symbol in having given birth to a son and thus she would "proudly bare her breasts to feed her child, deliberately provoking the envy of other women".[80]

At the end of the 19th century, as mentioned above, Heungseon Daewongun introduced magoja, a Manchu-style jacket, which is often worn over jeogori to this day.

A clothes reformation movement aimed at lengthening jeogori experienced wide success in the early 20th century and has continued to influence the shaping of modern hanbok. Modern jeogori are longer, although still halfway between the waistline and the breasts. Heoritti are sometimes exposed for aesthetic reasons.

Men's everyday wear

[edit]

Men's hanbok saw little change compared to women's hanbok. The form and design of jeogori and baji hardly changed.

In contrast, men's lengthy outwear, the equivalent of the modern overcoat, underwent a dramatic change. Before the late 19th century, yangban men almost always wore jungchimak when traveling. Jungchimak had very lengthy sleeves, and its lower part had split on both sides and occasionally on the back so as to create a fluttering effect in motion. To some this was fashionable, but to others, namely stoic scholars, it was nothing but pure vanity. Daewon-gun successfully banned jungchimak as a part of his clothes reformation program and jungchimak eventually disappeared.

Durumagi, which was previously worn underneath jungchimak and was basically a house dress, replaced jungchimak as the formal outwear for yangban men. Durumagi differs from its predecessor in that it has tighter sleeves and does not have splits on either side or back. It is also slightly shorter in length. Men's hanbok has remained relatively the same since the adoption of durumagi. In 1884, the Gapsin Dress Reform took place.[115] Under the 1884's decree of King Gojong, only narrow-sleeves traditional overcoats were permitted; as such, all Koreans, regardless of their social class, age and their gender started to wear the durumagi or chaksuui or ju-ui (周衣).[115]

Hats were an essential part of formal dress and the development of official hats became even more pronounced during this era due to the emphasis on Confucian values.[116] The gat was considered an essential aspect in a man's life. Joseon-era aristocrats also adopted a lot of hats which were introduced from China, such as the banggwan, sabanggwan, dongpagwan, waryonggwan, jeongjagwan, as well.[116] The popularity of those Chinese hats may have partially been due to the promulgation of Confucianism and because they were used by literary figures and scholars in China.[116] In 1895, King Gojong decreed adult Korean men to cut their hair short and western-style clothing were allowed and adopted.[115]

-

A man wearing jungchimak, 18th century

-

The "fluttering" effect, 18th century

-

Waryonggwan and hakchangui in 1863

-

Photograph taken in 1863

-

Photograph taken in 1863

-

Bokgeon and simui in 1880

-

Black bokgeon and blue dopo in 1880

-

Jeongjagwan on the head

-

A Korean in mourning clothes

-

Korean men, 1871

-

Young Korean man of the middle class, 1904

Material and color

[edit]

The upper classes wore hanbok of closely woven ramie cloth or other high-grade lightweight materials in warm weather and of plain and patterned silks the rest of the year. Commoners were restricted by law as well as resources to cotton at best.

The upper classes wore a variety of colors, though bright colors were generally worn by children and girls and subdued colors by middle-aged men and women. Commoners were restricted by law to everyday clothes of white, but for special occasions they wore dull shades of pale pink, light green, gray, and charcoal. The color of the chima showed the wearer's social position and statement. For example, a navy color indicated that a woman had a son(s). Only the royal family could wear clothing with geumbak-printed patterns (gold leaf) on the bottom of the chima.

Headdresses

[edit]Both men and women wore their hair in a long braid until they were married, at which time the hair was knotted. A man's hair was knotted in a topknot called sangtu (상투) on the top of the head, and the woman's hair was rolled into a ball-shaped form or komeori and was set just above the nape of the neck.

A long pin, or binyeo (비녀), was worn in women's knotted hair as both a fastener and a decoration. The material and length of the binyeo varied according to the wearer's class and status. Women also wore a ribbon known as a daenggi (댕기) to tie and decorate braided hair. Women wore a jokduri on their wedding day and wore an ayam for protection from the cold. Men wore a gat, which varied according to class and status.

Before the 19th century, women of high social backgrounds and kisaeng wore wigs (kach'e). Like their Western counterparts, Koreans considered bigger and heavier wigs to be more desirable and aesthetic. These became awkward to wear to the point that the government banned them in 1788.[117]

Owing to the influence of Neo-Confucianism, it was compulsory for women throughout the entire society to wear headdresses (nae-oe-seugae) to avoid exposing their faces when going outside. Those headdresses may include suegaechima (a headdress that looked like a chima but was narrower and shorter in style, worn by the upper-class women and later by all classes of people in late Joseon), the jang-ot, and the neoul (which was only permitted for court ladies and noblewomen).[118]

Later development

[edit]Modern hanbok is the direct descendant of hanbok patterned after those worn by aristocratic women or by the people who were at least from the middle-class in the Joseon period,[81][119] specifically the late 19th century. Hanbok had gone through various changes and fashion fads during the five hundred years under the reigns of Joseon kings and eventually evolved to what is now considered typical hanbok.

Beginning in the late 19th century, hanbok was largely replaced by new Western imports like the Western suit and dress. Today, formal and casual wear are usually based on Western styles. However, hanbok is still worn for traditional occasions, and is reserved for celebrations like weddings, the Lunar New Year, annual ancestral rites, or the birth of a child.

Modern usage

[edit]Hanbok was featured in international haute couture; on the catwalk, in 2015 when Karl Lagerfeld dressed Korean models for Chanel, and during Paris Fashion Week in photography by Phil Oh.[120] It has also been worn by international celebrities, such as Britney Spears and Jessica Alba, and athletes, such as tennis player Venus Williams and football player Hines Ward.[121][unreliable source]

Hanbok is also popular among Asian-American celebrities, such as Lisa Ling and Miss Asia 2014, Eriko Lee Katayama.[122] It has also made appearances on the red carpet, and was worn by Sandra Oh at the SAG Awards, and by Sandra Oh's mother who made fashion history in 2018 for wearing a hanbok to the Emmy Awards.[123]

South Korea

[edit]The South Korean government has supported the resurgence of interest in hanbok by sponsoring fashion designers.[124] Domestically, hanbok has become trendy in street fashion and music videos. It has been worn by prominent K-pop artists like Blackpink and BTS, notably in their music videos for "How You Like That" and "Idol."[125][unreliable source][126][unreliable source?]

In Seoul, tourist's wearing of hanbok makes their visit to the Five Grand Palaces (Changdeokgung, Changgyeonggung, Deoksugung, Gyeongbokgung and Gyeonghuigung) free of charge.

In Busan, the APEC South Korea 2005 provided hanbok for delegates of the 21 member economies of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

North Korea

[edit]Hanbok is also worn in present-day North Korea where it is known as chosŏnot (조선옷; 朝鮮옷).[127] The chosŏnot thus highlights the identity of the Korean ethnic and has been more actively promoted under the rule of Kim Jong Un.[127] The chosŏnot is currently typically worn during special occasions, e.g. weddings,[128]: 49 and when North Koreans celebrate the 60th, 70th, and 80th birthdays of their parents.[127] It is also mandated that women wear chosŏnot when attending National events, such as Kim Jong Il's birthday (16 February), International women's day (8 March), Kim Il Sung's birthday (15 April), Foundation Day (9 September).[128]: 78 White colored hanbok is often used as the color white has been the traditionally favored by the Korean people as the symbolism of pure spirit.[127]

The chima-jeogori remains the clothing of women, including female university students who are required to wear it as part of their university school uniforms.[127] The uniform of female university students has been a black-and-white chima-jeogori since the early to mid 2000s.[127] The chima can often be found at a length of about 30 cm from the ground for practical purposes in order to facilitate movements and to ensure that women could wear it during their daily workday with ease and comfort; this decrease in skirt length also gives a sense of modern style.[128]: 75

The chosŏnot patterns also have special meanings which are given by the North Koreans.[127] Generally, young people in North Korea like floral prints and bright colours, while the older generations favour simple styles of clothing and solid colours.[129]: 376 The chima-jeogori in North Korea is sometimes characterized by its use of floral patterns which are often added to the sleeves of the jeogori and to the chima.[127] Azaleas, in particular, are favoured in Yongbyon due to their association with the emotional poem Azaleas (《진달래꽃》) by Kim So-wol.[127] Men occasionally wear chosŏnot.[127]

However, chosŏnot are typically more expensive than ordinary clothing, and renting is available for people who cannot afford to purchase one; some are available for purchase at US$20 while the chosŏnot made in China with South Korean designs and fabrics are more expensive and can cost approximately US$3000.[127] The mid-2010s also saw the increased popularity of children dressing in chosŏnot by their parents.[127]

The custom of Korean costume was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage by North Korea in 2024.[130]

History in North Korea

[edit]The 1950s and 1960s also saw women from the upper-class wear chosŏnot made out of rayon while a black-and-white chima-jeogori consisting of a black long-length chima and white jeogori were used in the 1950s and 1960s where it was generally worn by women;[131] this style can, however, be traced to a typical clothing style used in the Joseon period.[127] This combination is still representative of the ideal woman and remains the official outfit for women in North Korea to this day.[128]: 77 In the 1980s, the chosŏnot became the official attire of women when attending ceremonies while western-style clothing became the everyday, ordinary clothing.[131]

After the mid-1990s due to extreme economic contractions, women could purchase their chosŏnot in private markets and were allowed to choose their desired colours and designs.[127]

In 2001, Lee Young-Hee, a South Korean hanbok designer visited Pyongyang to hold a fashion show at the Pyeongyang Youth Center on 4 and 6 June;[129]: 262 and since the 2002, North Korea have held their own fashion show in Pyongyang every spring.[131] Since 2001, there have been an increase of shops specialized in the customization of chosŏnot in Pyongyang which was reported by the KBCS.[129]: 261 This increase was due to a project implemented by the public service bureau of the Pyongyang People's Committee to increase chosŏnot tailoring shops.[129]: 262 These shops are typically found in large cities, such as Pyeongyang and Gaesong but are rarely found in small cities and villages.[129]: 262

Modern usage by Korean diaspora

[edit]China

[edit]

In China, the hanbok is referred as chaoxianfu (Chinese: 朝鮮服; 조선옷; 朝鮮옷; Joseon-ot) and is recognized as being the traditional ethnic clothing of chaoxianzu (simplified Chinese: 朝鲜族; traditional Chinese: 朝鮮族; pinyin: cháoxiǎnzú; lit. 'Joseon (Korean) ethnic group') in China. Chaoxianzu is an official term and is recognized as one of the official 55 ethnic minorities in China.[132] People of the chaoxianzu ethnic group are not recent immigrants to China, but have a long history having lived in China for generations.[133]: 240 They share the same ethnic identity as the ethnic Korean people in both North and South Korea, but are counted as Chinese citizens by nationality under the Constitution of China. Their traditions are not entirely the same due to their unique historical experiences, geographical location and mixed identities.[132] The term chaoxianzu literally corresponds to Chosŏnjok (조선족; 朝鮮族), a non-official derogatory term in South Korea, to refer to Hangukgye Junggugin (lit. 'Korean-Chinese'), which is the actual legal term in South Korea.[134] In the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, where most chaoxianzu reside,[132] the chaoxianfu was mostly worn on special occasions in the past;[133] however, by 2019, they had regained popularity and have become fashionable.[132]

Since the Chinese economic reform of China, there have been more exchanges with both Koreas leading to both the development and changes in chaoxianzu-style Chosŏn-ot in China;[132] some of designs of the chaoxianzu-style Chosŏn-ot have been influenced and inspired by both South Korean and North Korean hanbok designs.[133]: 246

Chaoxianzu people originally preferred to wear white as it represented cleanliness, simplicity, and purity; however, since the 20th century, the colours started to become brighter and more vivid as woven fabrics, such as polyester and nylon sateen, started to be introduced.[132] The "reform and opening up" of China also allowed for more exchanges with both Koreas, which lead to the both development and changes in the chaoxianfu of China.[132]

Following the chaoxianzu tradition, the chaoxianfu has an A-line in silhouette to give it the appearance of a mountain as per the tradition, women are the host of the family, and thus, women holding the household need to be stable; the chaoxianfu also covers the entire body.[132] The chaoxianzu have developed their own style of hanbok[135] due to the isolation for about 50 years from both North and South Korea.[133]: 240, 246 As a result, the styles of hanbok in South Korea, North Korea, and China, worn by the Korean people from these three countries have developed separately from each other. For example, Yemi Hanbok by Songok Ryu, an ethnic chaoxianzu from the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, is unique in both style and business model as it can operate in both South Korea and North Korea.[133]: 240, 246 In terms of chaoxianfu design, Yemi Hanbok designs are based on Chinese-style designs.[133]: 246 [dubious – discuss]

Over the years, the women's chaoxianfu also changed in length for the jeogori, git, and goreum and changed in width for the git, dong-jeong, sleeves, and goreum. The git and barae have evolved from straight to curve patterns. The wrinkle arrangement, length, and silhouette of the chima have also evolved; some of the skirts were sometimes decorated with gold embroidery or gold leaf at the bottom hem.[135] The colours used were also very varied; for example, feminine colours such as pink, yellow, and deep red could be used.[135] The 1990s saw the use of gold leaf, floral prints, embroidery on the women's chaoxianfu; the use of gradient colours also emerged.[135] For men, their jeogori, baji, and sleeves were made longer; their baji also became wider. The durumagi continues to be worn, and the baeja and magoja are worn frequently in present-days.[135]

On 7 June 2008, the chaoxianfu were approved by the State Council of China to be included in the second layer of national intangible cultural heritage.[132] In 2011, the chaoxianfu was officially designated as being part of the intangible cultural heritage of China by the Chinese government; while the announcement was welcomed by the chaoxianzu people in China as a proud indicator of their equal membership in a multi-ethnic and multicultural country such as China, it received negative criticism from South Koreans who perceived it as a "scandalous appropriation of the distinctive national culture of Koreans".[136]: 239 In 2022, a girl from the chaoxianzu ethnic group wore a chaoxianfu on the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics opening ceremony leading to an uproar from South Koreans who accused China of cultural appropriation.[134]

Social status

[edit]Especially from the Goryeo dynasty, the hanbok started to determine differences in social status (from people with the highest social status (kings), to those of the lowest social status (slaves)[137]) and gender through the many types, components,[137] colours,[138]: 132 and characteristics.[139] Although the modern hanbok does not express a person's status or social position, hanbok was an important element of distinguishment especially in the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties.[139] For example, farmers and commoners were not allowed to wear colour garments in their daily lives, excluding some categories of people, such as the shamans, gisaeng, and children, who were allowed to wear colourful clothing despite their social status.[138]: 132 Occasions when all people were allowed to wear colourful clothing were for special ceremonial occasions (e.g. wedding, birthday, holidays).[138]: 132

Clothes

[edit]Hwarot

[edit]Hwarot or hwal-ot was the full dress for a princess and the daughter of a king by a concubine, formal dress for the upper class, and bridal wear for ordinary women during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties.[140] Popular embroidered patterns on hwarot were lotuses, phoenixes, butterflies, and the ten traditional symbols of longevity: the sun; mountains; water; clouds; rocks/stone; pine trees; the mushroom of immortality; turtles; white cranes, and deer.[141] Each pattern represented a different role within society, for example: a dragon represented an emperor while a phoenix represented a queen; floral patterns represented a princess and a king's daughter by a concubine, and clouds and cranes represented high ranking court officials.[140] All these patterns throughout Korean history had meanings of longevity, good luck, wealth and honor.[140] Hwarot also had blue, red, and yellow colored stripes in each sleeve; a woman usually wore a scarlet-colored skirt and yellow or green-colored Jeogori, a traditional Korean jacket.[140] Hwarot was worn over the Jeogori and skirt.[140] A woman also wore her hair in a bun, with an ornamental hairpin and a ceremonial coronet.[140] A long ribbon was attached to the ornamental hairpin, the hairpin is known as Yongjam (용잠).[140] In more recent times, people wear hwarot on their wedding day, and so the Korean tradition survives in the present day.[140]

Wonsam

[edit]Wonsam was a ceremonial overcoat for a married woman in the Joseon dynasty.[142] The Wonsam was also adopted from China and is believed to have been one of the costumes from the Tang dynasty which was bestowed in the Unified Three Kingdoms period.[78] It was mostly worn by royalty, high-ranking court ladies, and noblewomen and the colors and patterns represented the various elements of the Korean class system.[142] The empress wore yellow; the queen wore red; the crown princess wore a purple-red color;[138]: 132 meanwhile a princess, a king's daughter by a concubine, and a woman of a noble family or lower wore green.[142] All the upper social ranks usually had two colored stripes in each sleeve: yellow-colored Wonsam usually had red and blue colored stripes, red-colored Wonsam had blue and yellow stripes, and green-colored Wonsam had red and yellow stripes.[142] Lower-class women wore many accompanying colored stripes and ribbons, but all women usually completed their outfit with onhye or danghye, traditional Korean shoes.[142]

Dangui

[edit]Dangui or tangwi were minor ceremonial robes for the queen, a princess, or wife of a high ranking government official while it was worn during major ceremonies among the noble class in the Joseon dynasty.[141] The materials used to make dangui varied depending on the season, so upper-class women wore thick dangui in winter while they wore thinner layers in summer.[143] The dangui came in many colors, but yellow and/or green were most common. However the emperor wore purple dangui, and the queen wore red.[143] In the Joseon dynasty, ordinary women wore dangui as part of their wedding dress.[143]

Myeonbok and Jeokui

[edit]Myeonbok

[edit]Myeonbok were the king's religious and formal ceremonial robes while jeokui were the queen's equivalent during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties.[144] Myeonbok was composed of Myeonryu-Gwan (면류관) and Gujang-bok (구장복).[144] Myonryu-Gwan had beads, which hung loose; these would prevent the king from seeing wickedness.[144] There were also wads of cotton in the left and right sides of Myeonryu-Gwan, and these were supposed to make the king oblivious to the influence of corrupt officials. Gujang-bok was black, and it bore nine symbols out of the Twelve ornaments, which all represented the king:[144]

- Dragon: A dragon's appearance paralleled how the king governed and subsequently brought balance to the world.[144]

- Fire: The king was expected to be intelligent and wise to govern the people effectively, like a guiding light represented by the fire.[144]

- Pheasant: The image of a pheasant represented magnificence.[144]

- Mountain: As a mountain is high, the king was on a par in terms of status and was deserving of respect and worship.[144]

- Tiger: A tiger represented the king's courage.[144]

- Monkey: A monkey symbolized wisdom.[144]

- Rice: As the people needed rice to live, the king was compared to this foodstuff as he had the responsibility of protecting their welfare.[144]

- Axe: This indicated that the king had the ability to save and take lives.[144]

- Water plant: Another depiction of the king's magnificence.[144]

Jeokui

[edit]Jeokui or tseogwi (Korean: 적의) was arranged through the use of different colors as a status symbol within the royal family.[145] The empress wore purple-red colored Jeokui, the queen wore pink, and the crown princess wore deep blue.[145] "Jeok" means pheasant, and so Jeokui often had depictions of pheasants embroidered onto it.[145]

Cheollik

[edit]

Cheollik (철릭) was a Korean adaptation of the Mongol tunic Terlig. The first recorded reference to the Terlig in Korea dates to the 15th century during the Joseon period. They were described as presents from the Ming dynasty or as military uniforms. A Joseon publication of a Goryeo period song Jeongseokga in the Akjang Gasa used the term Telik, referring to an officer's uniform. However, in surviving Goryeo literary sources, there is no reference to a term for clothing similar to Terlig in sound. Due to Mongol influence, some Korean vocabulary including official titles, falconry, and military terms originated in the Mongol language.[55]

The garment is presumed to have been worn from the mid-Goryeo period. By the early Joseon dynasty, it had already been adopted by various social strata for diverse functions, and it became widely popularized by the mid-Joseon period. While its applications changed thereafter, its most prevalent use until the end of the dynasty was as gongbok (official robes) for military officers and as siwibok (a uniform for royal escorts) during excursions outside the palace.[146]

The cheollik, unlike other forms of Korean clothing, is an amalgamation of a blouse with a kilt into a single item of clothing. The flexibility of the clothing allowed easy horsemanship and archery. During the Joseon dynasty, they continued to be worn by the king, and military officials for such activities. It was usually worn as a military uniform, but by the end of the Joseon dynasty, it had begun to be worn in more casual situations. A unique characteristic allowed the detachment of the cheollik's sleeves which could be used as a bandage if the wearer was injured in combat.[147]

Aengsam

[edit]Aengsam was the formal clothing for students during the national government exam and governmental ceremonies.[148] It was typically yellow, but for the student who scored the highest in the exam, they were rewarded with the ability to wear green Aengsam.[148] If the highest-scoring student was young, the king awarded him with red-colored Aengsam.[148] It was similar to the namsam but with a different colour.[149]

Accessories

[edit]

Binyeo

[edit]Binyeo was a traditional ornamental hairpin, and it had a different-shaped tip again depending on social status.[150] As a result, it was possible to determine the social status of the person by looking at the binyeo. Women in the royal family had dragon or phoenix-shaped binyeo while ordinary women had trees or Japanese apricot flowers.[151] Binyeo was a proof of marriage and considered a woman's expression of chastity and decency.[152]

Daenggi

[edit]Daenggi is a traditional Korean cloth ribbon used to tie and decorate braided hair.

Norigae

[edit]Norigae was a typical traditional accessory for women; it was worn by all women regardless of social ranks.[153][154] However, the social rank of the wearer determined the size and material of the norigae.[154]

Danghye

[edit]Danghye or tanghye (당혜) were shoes for married women in the Joseon dynasty.[155] Danghye were decorated with trees bearing grapes, pomegranates, chrysanthemums, or peonies: these were symbols of longevity.[156]

Danghye for a woman in the royal family were known as kunghye (궁혜), and they were usually patterned with flowers.[156]

Danghye for commoner women were known as onhye (온혜).[156]

Characteristics

[edit]Material

[edit]In Hanbok, various cotton fabrics are used as materials, and with the entry of Western civilization, the range of fabrics such as mixed fabrics has expanded. The use of materials also varies slightly depending on the jeogori and pants, and there is a big difference in the season.[157] In the case of jeogori, there are more than 10 types of general materials such as silk, jade, and general wool, and they use ramie or hemp in summer, and silk or Gapsa, Hangra, and Guksa cloth in spring and autumn.[158][159] The material used evenly throughout the four seasons was sesame, and silk, both ends, and silk were often used in the durumagi for adult men.[160] In the case of silk, which is one of the most widely used materials due to differences in lining and outer material, most of the silk jeogori was lined with silk, and if it was not possible, only the inside of the collar, the tip, and the sap were lined with silk. If this situation did not work out like this, the fine-grained cotton was used. In fact, more than half of the materials identified in the jeogori study were silk, followed by cotton and hemp.[161] In some cases, silk and cotton were lined with a mixture. When the jeogori was torn or broken, most of them were sewn with the same fabric, and a large piece was added to the elbow and sewn.[161] Just as in the fact that silk was used a lot in jeogori, silk, cotton, and literary arts were evenly used in various clothes, ranging from red ginseng, skirt, beoseon, and pants.

Misconception

[edit]Originally, hanbok chima(skirt) was worn with being tied around waist. It can be identified in paintings of Korea from 18th to 19th centuries.[162][163] Main misconception about hanbok is that hanbok has chima which resembled cloth for pregnant woman. This chima is not traditional hanbok. At about 1920, new chima was made to cover chest. This chima had strings which could be worn on the shoulder.[164][165] So this chima looked like that it started from over upper waist, almost from chest. This chima looked like cloth for pregnant woman. This chima did not exist in hanbok before about 1920. Traditional hanbok did not have this kind of chima before about 1920. Original hanbok chima was worn with being tied around waist.

-

Young people's outgoing, 19th century

-

Weaving a mat, 18th century

Hanbok Wave

[edit]The Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of South Korea, in partnership with the Korea Craft Design and Culture Promotion Agency, launched the Hanbok Wave initiative in 2020 to promote hanbok globally. In a statement, the ministry stated: "The interest in hanbok is rising around the world. Through collaborations with top Korean entertainers and artists who can showcase hanbok's traditional beauty and modern sensibility, we hope to make Korea’s traditional costume and hanbok-themed content more accessible and attractive."[166] The government will select four Korean hanbok makers to create designs inspired by the year's Hallyu Cultural Artist (muse). Once completed, the ministry will fund promotional campaigns, which will be featured on electronic billboards in Seoul and major cities abroad. Previous campaigns were held in cities such as New York, Paris and Milan.[166][167]

In 2025, the ministry appointed actor Park Bo-gum as the year's Hallyu Cultural Artist becoming the first male muse of the initiative.[169][170] The photos were unveiled during Chuseok with electronic billboards displayed in Myeongdong in Seoul, Times Square in Manhattan, Piazza del Duomo in Milan, Shinjuku in Tokyo, and Citadium Caumartin in Paris on October 6, 2025.[171][172] Harper's Bazaar Korea released four special edition covers featuring Park containing a 40-page pictorial of the actor wearing hanbok pieces designed by Dada Hanbok, OneOrigin, Mooroot, and Hanbok Moon.[173]

Hallyu Cultural Artists

[edit]- 2022: Yuna Kim, figure-skater[174]

- 2023: Bae Suzy, singer/actress[175]

- 2024: Kim Tae-ri, actress[176]

- 2025: Park Bo-gum, actor[177]

See also

[edit]- List of Korean clothing

- Hanfu - traditional Chinese clothing

- Vietnamese clothing - traditional Vietnamese clothing

- Wafuku - traditional Japanese clothing

References

[edit]- ^ Korean Culture and Information Service, 2018, Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea

- ^ "Minority Ethnic Clothing : Korean (Chaoxianzu) Clothing". 27 October 2022. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^

Ji-Yeon O. Jo (30 November 2017). "Koreans in the Commonwealth of Independent States". Homing: An Affective Topography of Ethnic Korean Return Migration. Nonolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780824872519. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

[...] Koryŏ Saram [...] did their best to maintain Korean traditions - for example, observing major Korean holidays, wearing hanbok (traditional Korean clothing) on culturally important days, playing customary Korean games, and making traditional rice cakes with traditional Korean tools that they had crafted in diaspora.

- ^ The Dreams of the Living and the Hopes of the Dead-Goguryeo Tomb Murals, 2007, Ho-Tae Jeon, Seoul National University Press

- ^ a b Flags, color, and the legal narrative : public memory, identity, and critique. Anne Wagner, Sarah Marusek. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. 2021. p. 125. ISBN 978-3-030-32865-8. OCLC 1253353500.

The basic structure of the Hanbok dress was designed to facilitate ease of movement, incorporating many shamanistic motifs.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "<Records of the Three Kingdoms>".

- ^ "<Book of Sui>". Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "History of Song".

- ^ "《고려도경》(高麗圖經)".

- ^ Passport to Korean culture. Haeoe Hongbowŏn. Seoul, Korea: Korean Culture and Information Service. 2009. ISBN 978-89-7375-153-2. OCLC 680802927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Gwak, Sung Youn Sonya (2006). Be(com)ing Korean in the United States: Exploring Ethnic Identity Formation Through Cultural Practices. Cambria Press. ISBN 9781621969723.

- ^ Lopez Velazquez, Laura (2021). "Hanbok during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasty". Korea.net. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ 백의민족 (白衣民族) - Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^ "Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty". Archived from the original on 20 June 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty". Archived from the original on 20 June 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty". Archived from the original on 20 June 2024. Retrieved 20 June 2024.

- ^ Passport to Korean culture. Haeoe Hongbowŏn. Seoul, Korea: Korean Culture and Information Service. 2009. ISBN 978-89-7375-153-2. OCLC 680802927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ 한복데이, 전국 5개 도시서 펼쳐진다. 쿠키뉴스 (in Korean). 15 September 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b 역사 속의 우리 옷 변천사, 2009, Chonnam National University Press

- ^ 김, 여경 (2010). 2000년 이후 인쇄매체에 나타난 한복의 조형미 연구. ScienceON (in Korean). Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ a b c "Traditional clothing". KBS Global. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f 저고리 (in Korean). Doosan Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 15 March 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ 저고리 (in Korean). Empas / Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 March 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ a b 치마 (in Korean). Nate / Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 March 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Jeogori Before 1910". Gwangju Design Biennale. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ^ 단추. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ a b 치마 (in Korean). Nate / EncyKorea. Archived from the original on 21 March 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Important Folklore Materials:117-23". Cultural Heritage Administration. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Important Folklore Materials: 229-1-4. Skirt belonging to a Jinju Ha clan woman, who died in 1646". Cultural Heritage Administration. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ 금박(in Korean) - Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture.

- ^ "World Underwear History: Enlightenment Era". Good People Co. Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "World Underwear History: Enlightenment Era". Good People Co. Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Recycle LACMA: Red Korean Skirt". Robert Fontenot. June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Recycle LACMA: Purple Korean Skirt". Robert Fontenot. June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Korea Information". Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ Voice, Ewha (1 September 2005). "Underwear Coming Out: No More a Taboo". Ewha Voice. Ehwa Voice. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "About hanbok". han-style.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ a b c 포 (袍) (in Korean). Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d 두루마기 (in Korean). Empas / Britannica. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "두루마기 (in Korean)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ 최, 해율 (2007). "A Study on the Design of Historical Costume for Making Movie & multimedia-Focused on rich women's costume of Goryeo-yang and Mongol-pung in Thirteenth to Fourteenth Century-". 한국복식학회. 57 (1): 176–186. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ^ Congwen Shen 沈從文. Research on Ancient Chinese Clothing 中國古代服飾研究.Hong Kong Publishing Company, 1981 香港:商務印書館,1981

- ^ "Men's Clothing". Life in Korea. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ a b 까치두루마기 (in Korean). Nate / EncyKorea. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "Geocities.com". Julia's Cook Korean site. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ^ 까치두루마기 (in Korean and English). Daum Korean-English Dictionary.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Encyber.com". Retrieved 8 October 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ The Groom's Wedding Attire Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Academia Koreana of Keimyung University

- ^ "What are the traditional national clothes of Korea?". Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "Hanboks (Traditional Clothing)". Headgear and Accessories Worn Together with Hanbok. Korea Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- ^ Kim, In-Suk (1977). 심의고(深依考). Journal of the Korean Society of Costume. 1: 101–117. ISSN 1229-6880.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Yu, Ju-Ri; Kim, Jeong-Mee (2006). "A Study on Costume Culture Interchange Resulting from Political Factors". Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles. 30 (3): 458–469.

- ^ a b Kyu-Seong, Choi (2004). "A Study of People's Lives and Traditional Costumes in Goryeo Dynasty". The Research Journal of the Costume Culture. 12 (6): 1060–1069. ISSN 1226-0401. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Fashion, identity, and power in modern Asia. Kyunghee Pyun, Aida Yuen Wong. Cham, Switzerland. 2018. p. 116. ISBN 978-3-319-97199-5. OCLC 1059514121.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Cho, Woohyun; Yi, Jaeyoon; Kim, Jinyoung (2015). "The dress of the Mongol Empire: Genealogy and diaspora of the Terlig". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 68 (3): 22–29. doi:10.1556/062.2015.68.3.2. ISSN 0001-6446.

- ^ a b c Choi, Hai-Yaul (2007). "A Study on the Design of Historical Costume for Making Movie & Multimedia -Focused on Rich Women's Costume of Goryeo-Yang and Mongol-Pung in the 13th to 14th Century-". Journal of the Korean Society of Costume. 57 (1): 176–186. ISSN 1229-6880. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kim, Jinyoung; Lee, Jaeyeong; Lee, Jongoh (2015). ""GORYEOYANG" AND "MONGOLPUNG" in the 13th-14th CENTURIES". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 68 (3): 281–292. doi:10.1556/062.2015.68.3.3. ISSN 0001-6446. JSTOR 43957480. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ 고려(高麗)의 원(元)에 대(對)한 공녀(貢女),유홍렬,震檀學報,1957

- ^ 옷의 역사 (in Korean). Daum / Global World Encyclopedia.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Misie Lander (January 2017). Hanbok: An Introduction to South Korea's National Dress

- ^ Myeong-Jong, Yoo (2005). The Discovery of Korea: History-Nature-Cultural Heritages-Art-Tradition-Cities. Discovery Media. p. 123. ISBN 978-8995609101.