Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hominidae

View on Wikipedia

| Hominidae[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| The eight extant hominid species, one row per genus (humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Parvorder: | Catarrhini |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea |

| Family: | Hominidae Gray, 1825[2] |

| Type genus | |

| Homo Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subfamilies | |

|

sister: Hylobatidae | |

| |

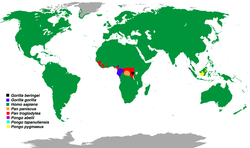

| Distribution of great ape species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Hominidae (/hɒˈmɪnɪdiː/), whose members are known as the great apes[note 1] or hominids (/ˈhɒmɪnɪdz/), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: Pongo (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); Gorilla (the eastern and western gorilla); Pan (the chimpanzee and the bonobo); and Homo, of which only modern humans (Homo sapiens) remain.[1]

Numerous revisions in classifying the great apes have caused the use of the term hominid to change over time. The original meaning of "hominid" referred only to humans (Homo) and their closest extinct relatives. However, by the 1990s humans and other apes were considered to be "hominids".

The earlier restrictive meaning has now been largely assumed by the term hominin, which comprises all members of the human clade after the split from the chimpanzees (Pan). The current meaning of "hominid" includes all the great apes including humans. Usage still varies, however, and some scientists and laypersons still use "hominid" in the original restrictive sense; the scholarly literature generally shows the traditional usage until the turn of the 21st century.[5]

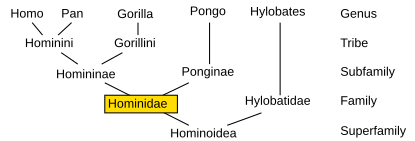

Within the taxon Hominidae, a number of extant and extinct genera are grouped with the humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas in the subfamily Homininae; others with orangutans in the subfamily Ponginae (see classification graphic below). The most recent common ancestor of all Hominidae lived roughly 14 million years ago,[6] when the ancestors of the orangutans speciated from the ancestral line of the other three genera.[7] Those ancestors of the family Hominidae had already speciated from the family Hylobatidae (the gibbons), perhaps 15 to 20 million years ago.[7][8]

Due to the close genetic relationship between humans and the other great apes, certain animal rights organizations, such as the Great Ape Project, argue that nonhuman great apes are persons and should be given basic human rights. Twenty-nine countries have instituted research bans to protect great apes from any kind of scientific testing.[9]

Evolution

[edit]

In the early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, there were many species of tree-adapted primitive catarrhines from East Africa; the variety suggests a long history of prior diversification. Fossils from 20 million years ago include fragments attributed to Victoriapithecus, the earliest Old World monkey. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa.

At sites far distant from East Africa, the presence of other generalized non-cercopithecids, that is, non-monkey catarrhines, of middle Miocene age—Otavipithecus from cave deposits in Namibia, and Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus from France, Spain and Austria—is further evidence of a wide diversity of ancestral ape forms across Africa and the Mediterranean basin during the relatively warm and equable climatic regimes of the early and middle Miocene. The most recent of these far-flung Miocene apes (hominoids) is Oreopithecus, from the fossil-rich coal beds in northern Italy and dated to 9 million years ago.

Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons (family Hylobatidae), the "lesser apes", diverged from that of the great apes some 18–12 million years ago, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae) diverged from the other great apes at about 12 million years. There are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a still-unknown South East Asian hominoid population; but fossil proto-orangutans, dated to around 10 million years ago, may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey.[10] Species close to the last common ancestor of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans may be represented by Nakalipithecus fossils found in Kenya. Molecular evidence suggests that between 8 and 4 million years ago, first the gorillas (genus Gorilla), and then the chimpanzees (genus Pan) split off from the line leading to humans. Human DNA is approximately 98.4% identical to that of chimpanzees when comparing single nucleotide polymorphisms (see human evolutionary genetics).[11] The fossil record, however, of gorillas and chimpanzees is limited; both poor preservation—rain forest soils tend to be acidic and dissolve bone—and sampling bias probably contribute most to this problem.

Other hominins probably adapted to the drier environments outside the African equatorial belt; and there they encountered antelope, hyenas, elephants and other forms becoming adapted to surviving in the East African savannas, particularly the regions of the Sahel and the Serengeti. The wet equatorial belt contracted after about 8 million years ago, and there is very little fossil evidence for the divergence of the hominin lineage from that of gorillas and chimpanzees—which split was thought to have occurred around that time. The earliest fossils argued by some to belong to the human lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma), followed by Ardipithecus (5.5–4.4 Ma), with species Ar. kadabba and Ar. ramidus.

Taxonomy

[edit]Terminology

[edit]

The classification of the great apes has been revised several times in the last few decades; these revisions have led to a varied use of the word "hominid" over time. The original meaning of the term referred to only humans and their closest relatives—what is now the modern meaning of the term "hominin". The meaning of the taxon Hominidae changed gradually, leading to a modern usage of "hominid" that includes all the great apes including humans.

A number of very similar words apply to related classifications:

- A hominoid, sometimes called an ape, is a member of the superfamily Hominoidea: extant members are the gibbons (lesser apes, family Hylobatidae) and the hominids.

- A hominid is a member of the family Hominidae, the great apes: orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans.

- A hominine is a member of the subfamily Homininae: gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans (excludes orangutans).

- A hominin is a member of the tribe Hominini: chimpanzees and humans.[12]

- A homininan, following a suggestion by Wood and Richmond (2000), would be a member of the subtribe Hominina of the tribe Hominini: that is, modern humans and their closest relatives, including Australopithecina, but excluding chimpanzees.[13][14]

- A human is a member of the genus Homo, of which Homo sapiens is the only extant species, and within that Homo sapiens sapiens is the only surviving subspecies.

A cladogram indicating common names (cf. more detailed cladogram below):

| Hominoidea |

| ||||||

| hominoids, apes |

Extant and fossil relatives of humans

[edit]

Hominidae was originally the name given to the family of humans and their (extinct) close relatives, with the other great apes (that is, the orangutans, gorillas and chimpanzees) all being placed in a separate family, the Pongidae. However, that definition eventually made Pongidae paraphyletic because at least one great ape species (the chimpanzees) proved to be more closely related to humans than to other great apes. Most taxonomists today encourage monophyletic groups—this would require, in this case, the use of Pongidae to be restricted to just one closely related grouping. Thus, many biologists now assign Pongo (as the subfamily Ponginae) to the family Hominidae. The taxonomy shown here follows the monophyletic groupings according to the modern understanding of human and great ape relationships.

Humans and close relatives including the tribes Hominini and Gorillini form the subfamily Homininae (see classification graphic below). (A few researchers go so far as to refer the chimpanzees and the gorillas to the genus Homo along with humans.)[15][16][17] But, those fossil relatives more closely related to humans than the chimpanzees represent the especially close members of the human family, and without necessarily assigning subfamily or tribal categories.[clarification needed][18]

Many extinct hominids have been studied to help understand the relationship between modern humans and the other extant hominids. Some of the extinct members of this family include Gigantopithecus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and the australopithecines Australopithecus and Paranthropus.[19]

The exact criteria for membership in the tribe Hominini under the current understanding of human origins are not clear, but the taxon generally includes those species that share more than 97% of their DNA with the modern human genome, and exhibit a capacity for language or for simple cultures beyond their "local family" or band. The theory of mind concept—including such faculties as empathy, attribution of mental state, and even empathetic deception—is a controversial criterion; it distinguishes the adult human alone among the hominids. Humans acquire this capacity after about four years of age, whereas it has not been proven (nor has it been disproven) that gorillas or chimpanzees ever develop a theory of mind.[20] This is also the case for some New World monkeys outside the family of great apes, as, for example, the capuchin monkeys.

However, even without the ability to test whether early members of the Hominini (such as Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, or even the australopithecines) had a theory of mind, it is difficult to ignore similarities seen in their living cousins. Orangutans have shown the development of culture comparable to that of chimpanzees,[21] and some[who?] say the orangutan may also satisfy those criteria for the theory of mind concept. These scientific debates take on political significance for advocates of great ape personhood.

Description

[edit]

The great apes are tailless primates, with the smallest living species being the bonobo at 30 to 40 kilograms (66 to 88 lb) in weight, and the largest being the eastern gorillas, with males weighing 140 to 180 kilograms (310 to 400 lb). In all great apes, the males are, on average, larger and stronger than the females, although the degree of sexual dimorphism varies greatly among species. Hominid teeth are similar to those of the Old World monkeys and gibbons, although they are especially large in gorillas. The dental formula is 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. Human teeth and jaws are markedly smaller relative to body size compared to those of other apes. This may be an adaptation not only to the extensive use of tools, which has supplanted the role of jaws in hunting and fighting, but also to eating cooked food since the end of the Pleistocene.[22][23]

Behavior

[edit]Although most living species are predominantly quadrupedal, they are all able to use their hands for gathering food or nesting materials, and, in some cases, for tool use.[24] They build complex sleeping platforms, also called nests, in trees to sleep in at night, but chimpanzees and gorillas also build terrestrial nests, and gorillas can also sleep on the bare ground.[25]

All species are omnivorous,[26] although chimpanzees and orangutans primarily eat fruit. When gorillas run short of fruit at certain times of the year or in certain regions, they resort to eating shoots and leaves, often of bamboo, a type of grass. Gorillas have extreme adaptations for chewing and digesting such low-quality forage, but they still prefer fruit when it is available, often going miles out of their way to find especially preferred fruits. Humans, since the Neolithic Revolution, have consumed mostly cereals and other starchy foods, including increasingly highly processed foods, as well as many other domesticated plants (including fruits) and meat.

Both chimpanzees and humans are known to wage wars over territories and resources.[27]

Gestation in great apes lasts 8–9 months, and results in the birth of a single offspring, or, rarely, twins. The young are born helpless, and require care for long periods of time. Compared with most other mammals, great apes have a remarkably long adolescence, not being weaned for several years,[28] and not becoming fully mature for eight to thirteen years in most species (longer in orangutans and humans). As a result, females typically give birth only once every few years. There is no distinct breeding season.[24]

Gorillas and chimpanzees live in family groups of around five to ten individuals, although much larger groups are sometimes noted. Chimpanzees live in larger groups that break up into smaller groups when fruit becomes less available. When small groups of female chimpanzees go off in separate directions to forage for fruit, the dominant males can no longer control them and the females often mate with other subordinate males. In contrast, groups of gorillas stay together regardless of the availability of fruit. When fruit is hard to find, they resort to eating leaves and shoots.

This fact is related to gorillas' greater sexual dimorphism relative to that of chimpanzees; that is, the difference in size between male and female gorillas is much greater than that between male and female chimpanzees. This enables gorilla males to physically dominate female gorillas more easily. In both chimpanzees and gorillas, the groups include at least one dominant male, and young males leave the group at maturity.

Legal status

[edit]Due to the close genetic relationship between humans and the other great apes, certain animal rights organizations, such as the Great Ape Project, argue that nonhuman great apes are persons and, per the Declaration on Great Apes, should be given basic human rights. In 1999, New Zealand was the first country to ban any great ape experimentation, and now 29 countries have currently instituted a research ban to protect great apes from any kind of scientific testing.

On 25 June 2008, the Spanish parliament supported a new law that would make "keeping apes for circuses, television commercials or filming" illegal.[29] On 8 September 2010, the European Union banned the testing of great apes.[30]

Conservation

[edit]The following table lists the estimated number of great ape individuals living outside zoos.

| Species | Estimated number |

Conservation status |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bornean orangutan | 104,700 | Critically endangered | [31] |

| Sumatran orangutan | 6,667 | Critically endangered | [32] |

| Tapanuli orangutan | 800 | Critically endangered | [33] |

| Western gorilla | 200,000 | Critically endangered | [34] |

| Eastern gorilla | <5,000 | Critically endangered | [35] |

| Chimpanzee | 200,000 | Endangered | [36][37] |

| Bonobo | 10,000 | Endangered | [36] |

| Human | 8,211,817,000 | N/A | [38][39] |

Phylogeny

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

Taxonomy of Hominoidea (emphasis on family Hominidae): After an initial separation from the main line by the Hylobatidae (gibbons) some 18 million years ago, the line of Ponginae broke away, leading to the orangutan; later, the Homininae split into the tribes Hominini (led to humans and chimpanzees) and Gorillini (led to gorillas).

Below is a cladogram with extinct species.[40][41][42][failed verification] It is indicated approximately how many million years ago (Mya) the clades diverged into newer clades.[43]

| Hominidae (18) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extant

[edit]There are eight living species of great ape which are classified in four genera. The following classification is commonly accepted:[1]

- Family Hominidae: humans and other great apes; extinct genera and species excluded[1]

- Subfamily Ponginae

- Tribe Pongini

- Genus Pongo

- Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus

- Northwest Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus

- Northeast Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus morio

- Central Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii

- Sumatran orangutan, Pongo abelii

- Tapanuli orangutan, Pongo tapanuliensis[44]

- Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus

- Genus Pongo

- Tribe Pongini

- Subfamily Homininae

- Tribe Gorillini

- Genus Gorilla

- Western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Western lowland gorilla, Gorilla gorilla gorilla

- Cross River gorilla, Gorilla gorilla diehli

- Eastern gorilla, Gorilla beringei

- Mountain gorilla, Gorilla beringei beringei

- Eastern lowland gorilla, Gorilla beringei graueri

- Western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Genus Gorilla

- Tribe Hominini

- Subtribe Panina

- Genus Pan

- Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes

- Central chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes troglodytes

- Western chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus

- Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes ellioti

- Eastern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

- Bonobo, Pan paniscus

- Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes

- Genus Pan

- Subtribe Hominina

- Genus Homo

- Human, Homo sapiens

- Anatomically modern human, Homo sapiens sapiens

- Human, Homo sapiens

- Genus Homo

- Subtribe Panina

- Tribe Gorillini

- Subfamily Ponginae

Fossil

[edit]

In addition to the extant species and subspecies, archaeologists, paleontologists, and anthropologists have discovered and classified numerous extinct great ape species as below, based on the taxonomy shown.[45]

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family Hominidae

- Subfamily Ponginae[46]

- Tribe Lufengpithecini †

- Lufengpithecus

- Lufengpithecus lufengensis

- Lufengpithecus keiyuanensis

- Lufengpithecus hudienensis

- Meganthropus

- Meganthropus palaeojavanicus

- Lufengpithecus

- Tribe Sivapithecini†

- Ankarapithecus

- Ankarapithecus meteai

- Sivapithecus

- Sivapithecus brevirostris

- Sivapithecus punjabicus

- Sivapithecus parvada

- Sivapithecus sivalensis

- Sivapithecus indicus

- Gigantopithecus

- Gigantopithecus bilaspurensis

- Gigantopithecus blacki

- Gigantopithecus giganteus

- Ankarapithecus

- Tribe Pongini

- Tribe Lufengpithecini †

- Subfamily Homininae[47][48]

- Tribe Dryopithecini † (placement disputed)

- Kenyapithecus (placement disputed)

- Kenyapithecus wickeri

- Danuvius

- Danuvius guggenmosi

- Pierolapithecus (placement disputed)

- Pierolapithecus catalaunicus

- Ouranopithecus

- Ouranopithecus macedoniensis

- Otavipithecus

- Otavipithecus namibiensis

- Morotopithecus (placement disputed)

- Morotopithecus bishopi

- Oreopithecus (placement disputed)

- Oreopithecus bambolii

- Nakalipithecus

- Nakalipithecus nakayamai

- Anoiapithecus

- Anoiapithecus brevirostris

- Hispanopithecus (placement disputed)

- Hispanopithecus laietanus

- Hispanopithecus crusafonti

- Dryopithecus

- Rudapithecus (placement disputed)

- Rudapithecus hungaricus

- Samburupithecus

- Samburupithecus kiptalami

- Graecopithecus (placement disputed)

- Graecopithecus freybergi

- Kenyapithecus (placement disputed)

- Tribe Gorillini

- Chororapithecus † (placement debated)

- Chororapithecus abyssinicus

- Chororapithecus † (placement debated)

- Tribe Hominini

- Subtribe Panina

- Subtribe Hominina

- Sahelanthropus†

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis

- Orrorin†

- Orrorin tugenensis

- Orrorin praegens

- Ardipithecus†

- Kenyanthropus†

- Kenyanthropus platyops

- Australopithecus†

- Paranthropus†

- Homo – close relatives of modern humans

- Homo gautengensis† (probable H. habilis specimens)

- Homo rudolfensis† (membership in Homo uncertain)

- Homo habilis† (membership in Homo uncertain)

- Homo naledi† (membership in Homo uncertain)

- Dmanisi Man, Homo georgicus† (probable early subspecies of Homo erectus)

- Homo ergaster† (African Homo erectus)

- Homo erectus†

- Homo erectus bilzingslebenensis †

- Java Man, Homo erectus erectus †

- Lantian Man, Homo erectus lantianensis †

- Nanjing Man, Homo erectus nankinensis †

- Peking Man, Homo erectus pekinensis †

- Solo Man, Homo erectus soloensis † (possible separate species)

- Tautavel Man, Homo erectus tautavelensis †

- Yuanmou Man, Homo erectus yuanmouensis †

- Flores Man or Hobbit, Homo floresiensis† (membership in Homo uncertain)

- Homo luzonensis † (membership in Homo uncertain)

- Homo antecessor†

- Homo heidelbergensis†

- Homo cepranensis† (probable H. heidelbergensis specimens)

- Homo helmei† (probable early H. sapiens specimens)

- Denisovans (scientific name not yet assigned, may include Penghu 1)†

- Neanderthal, Homo neanderthalensis†

- Homo rhodesiensis† (probable late H. heidelbergensis specimens)

- Modern human, Homo sapiens (sometimes called Homo sapiens sapiens)

- Sahelanthropus†

- Tribe Dryopithecini † (placement disputed)

See also

[edit]- Bili ape

- Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS film)

- Great ape language

- Planet of the Apes franchise

- Great Ape Project

- Great ape research ban

- Great Apes Survival Partnership

- International Primate Day

- Kinshasa Declaration on Great Apes

- List of human evolution fossils

- List of individual apes

- Monkeys and apes in space

- Oldest hominids

- Prehistoric Autopsy (2012 BBC documentary)

- Primate cognition

- The Mind of an Ape

- Timeline of human evolution

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Great ape" is a common name rather than a taxonomic label, and there are differences in usage, even by the same author. The term may or may not include humans, as when Dawkins writes "Long before people thought in terms of evolution ... great apes were often confused with humans"[3][better source needed] and "gibbons are faithfully monogamous, unlike the great apes which are our closer relatives."[4][better source needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 181–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (1825). "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into Tribes and Families, with a list of genera apparently appertaining to each Tribe". Annals of Philosophy. New Series. 10: 337–334.

- ^ Dawkins, R. (2005). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life (p/b ed.). London, England: Phoenix (Orion Books). p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7538-1996-8.

- ^ Dawkins (2005), p. 126.

- ^ Morton, Mary. "Hominid vs. hominin". Earth Magazine. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Andrew Hill; Steven Ward (1988). "Origin of the Hominidae: The Record of African Large Hominoid Evolution Between 14 My and 4 My". Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 31 (59): 49–83. Bibcode:1988AJPA...31S..49H. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330310505.

- ^ a b Dawkins R (2004) The Ancestor's Tale.

- ^ "Query: Hominidae/Hylobatidae". TimeTree. Temple University. 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "International Bans | Laws | Release & Restitution for Chimpanzees". releasechimps.org. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Srivastava, R. P. (2009). Morphology of the Primates And Human Evolution. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 978-81-203-3656-8. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Chen, Feng-Chi; Li, Wen-Hsiung (15 January 2001). "Genomic Divergences between Humans and Other Hominoids and the Effective Population Size of the Common Ancestor of Humans and Chimpanzees". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 444–456. doi:10.1086/318206. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1235277. PMID 11170892.

- ^ B. Wood (2010). "Reconstructing human evolution: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (Suppl 2): 8902–8909. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8902W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001649107. PMC 3024019. PMID 20445105.

- ^ Wood, Bernard; Richmond, Brian G. (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.. In this suggestion, the new subtribe of Hominina was to be designated as including the genus Homo exclusively, so that Hominini would have two subtribes, Australopithecina and Hominina, with the only known genus in Hominina being Homo. Orrorin (2001) has been proposed as a possible ancestor of Hominina but not Australopithecina.Reynolds, Sally C.; Gallagher, Andrew (29 March 2012). African Genesis: Perspectives on Hominin Evolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107019959.. Designations alternative to Hominina have been proposed: Australopithecinae (Gregory & Hellman 1939) and Preanthropinae (Cela-Conde & Altaba 2002); Brunet, M.; et al. (2002). "A new hominid from the upper Miocene of Chad, central Africa" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969. Cela-Conde, C.J.; Ayala, F.J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". PNAS. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185. Wood, B.; Lonergan, N. (2008). "The hominin fossil record: taxa, grades and clades" (PDF). J. Anat. 212 (4): 354–376. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00871.x. PMC 2409102. PMID 18380861.

- ^ "GEOL 204 The Fossil Record: The Scatterlings of Africa: The Origins of Humanity". www.geol.umd.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ Pickrell, John (20 May 2003). "Chimps Belong on Human Branch of Family Tree, Study Says". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 1 June 2003. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ "Relationship Humans-Gorillas". berggorilla.de. 21 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 November 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Watson, E. E.; et al. (2001). "Homo genus: a review of the classification of humans and the great apes". In Tobias, P. V.; et al. (eds.). Humanity from African Naissance to Coming Millennia. Florence: Firenze Univ. Press. pp. 311–323.

- ^ Schwartz, J.H. (1986). "Primate systematics and a classification of the order". In Swindler, Daris R.; Erwin, J. (eds.). Comparative Primate Biology. Vol. 1: Systematics, evolution, and anatomy. New York: Wiley-Liss. p. 1–41. ISBN 978-0-471-62644-2.

- ^ Schwartz, J.H. (2004). "Issues in hominid systematics". Paleoantropología (4). ALCALA DE HENARES: 360–371.

- ^ Heyes, C. M. (1998). "Theory of Mind in Nonhuman Primates" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 21 (1): 101–14. doi:10.1017/S0140525X98000703. PMID 10097012. S2CID 6469633. bbs00000546.

- ^ Van Schaik C.P.; Ancrenaz, M; Borgen, G; Galdikas, B; Knott, CD; Singleton, I; Suzuki, A; Utami, SS; Merrill, M (2003). "Orangutan cultures and the evolution of material culture". Science. 299 (5603): 102–105. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..102V. doi:10.1126/science.1078004. PMID 12511649. S2CID 25139547.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; Mahler, Paul Emil (1971). "Post-Pleistocene changes in the human dentition" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 34 (2): 191–203. Bibcode:1971AJPA...34..191B. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330340205. hdl:2027.42/37509. PMID 5572603.

- ^ Wrangham, Richard (2007). "Chapter 12: The Cooking Enigma". In Charles Pasternak (ed.). What Makes Us Human?. Oxford: Oneworld Press. ISBN 978-1-85168-519-6.

- ^ a b Harcourt, A.H.; MacKinnon, J.; Wrangham, R.W. (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 422–439. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ^ Hernandez-Aguilar, R. Adriana; Reitan, Trond (2020). "Deciding Where to Sleep: Spatial Levels of Nesting Selection in Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Living in Savanna at Issa, Tanzania". International Journal of Primatology. 41 (6): 870–900. doi:10.1007/s10764-020-00186-z. hdl:10852/85314.

- ^ Alina, Bradford (29 May 2015). "Facts About Apes". livescience.com. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "Scientists observe chimpanzees using human-like warfare tactic". Reuters. 3 November 2023.

- ^ Hamilton, Jon (17 May 2017). "Orangutan Moms Are The Primate Champs Of Breast-Feeding". NPR. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Spanish parliament to extend rights to apes". Reuters. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ "New EU rules on animal testing ban use of apes". Independent.co.uk. 12 September 2010.

- ^ "Bornean Orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus". New England Primate Conservancy. 29 October 2021. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ An estimate of the number of wild orangutans in 2004: "Orangutan Action Plan 2007–2017" (PDF). Government of Indonesia. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2024.

Pada IUCN Red List Edisi tahun 2002 orangutan sumatera dikategorikan Critically Endangered, artinya sudah sangat terancam kepunahan, sedangkan orangutan kalimantan dikategorikan Endangered atau langka.

- ^ "Tapanuli Orangutan, Pongo tapanuliensis". New England Primate Conservancy. 30 October 2021. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

- ^ "Gorillas on Thin Ice". United Nations Environment Programme. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ IUCN (2 August 2018). Eastern Gorilla: Gorilla beringei Plumptre, A., Robbins, M.M. & Williamson, E.A.: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T39994A115576640 (Report). doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2019-1.rlts.t39994a115576640.en. Archived from the original on 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b Vigilant, Linda (2004). "Chimpanzees". Current Biology. 14 (10): R369 – R371. Bibcode:2004CBio...14.R369V. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.006. PMID 15186757.

- ^ "Chimpanzees". WWF. 28 May 2024. Archived from the original on 14 August 2024. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "U.S. and World Population Clock". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Worldometer world population clock".

- ^ Grabowski, Mark; Jungers, William L. (2017). "Evidence of a chimpanzee-sized ancestor of humans but a gibbon-sized ancestor of apes". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 880. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..880G. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00997-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5638852. PMID 29026075.

- ^ Nengo, Isaiah; Tafforeau, Paul; Gilbert, Christopher C.; Fleagle, John G.; Miller, Ellen R.; Feibel, Craig; Fox, David L.; Feinberg, Josh; Pugh, Kelsey D. (2017). "New infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape evolution". Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..169N. doi:10.1038/nature23456. PMID 28796200. S2CID 4397839.

- ^ "Hominidae | primate family". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Malukiewicz, Joanna; Hepp, Crystal M.; Guschanski, Katerina; Stone, Anne C. (1 January 2017). "Phylogeny of the jacchus group of Callithrix marmosets based on complete mitochondrial genomes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (1): 157–169. Bibcode:2017AJPA..162..157M. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23105. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 27762445. Fig 2: "Divergence time estimates for the jacchus marmoset group based on the BEAST4 (Di Fiore et al., 2015) calibration scheme for alignment A.[...] Numbers at each node indicate the median divergence time estimate."

- ^ Nater, Alexander; Mattle-Greminger, Maja P.; Nurcahyo, Anton; et al. (2 November 2017). "Morphometric, Behavioral, and Genomic Evidence for a New Orangutan Species". Current Biology. 27 (22): 3487–3498.e10. Bibcode:2017CBio...27E3487N. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.047. hdl:10230/34400. PMID 29103940.

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko (14 January 2005). "Hominoidea". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko (4 February 2004). "Pongidae". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko (14 January 2005). "Hominoidea". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko (10 November 2007). "Hominidae". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

External links

[edit]- The Animal Legal and Historical Center at Michigan State University College of Law, Great Apes and the Law (archived 13 April 2011)

- NPR News: Toumaï the Human Ancestor

- Hominid Species at TalkOrigins Archive

- For more details on Hominid species, including photos of fossil hominids (archived 30 April 2013)

- Scientific American magazine (April 2006 Issue) Why Are Some Animals So Smart? (archived 14 October 2007)

- A new mediterranean hominoid-hominid link discovered, Anoiapithecus brevirostris, "Lluc": A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Link to graphical reconstruction

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

Hominidae

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Classification

Defining Characteristics

Hominidae, comprising humans and the great apes, are defined by several key morphological synapomorphies distinguishing them from other primates, including the complete absence of an external tail in adults.[1] This tailless condition contrasts with tailed monkeys and lesser apes. They exhibit large body sizes, typically exceeding 20 kg in adults, with robust builds and elongated forearms adapted for suspensory locomotion in non-human members.[1] [8] Cranially, hominids possess relatively enlarged brains, with endocranial volumes averaging 300-500 cm³ in great apes and up to 1,350 cm³ in modern humans, far exceeding those of other primates relative to body mass.[9] [1] Dentally, they share the Y-5 cusp pattern on lower molars, featuring five cusps linked in a Y-shaped groove, a derived trait from the more primitive quadrate pattern.[8] Postcranially, the family is marked by broad chests, flexible shoulder girdles enabling extensive arm rotation, and opposable pollex (thumb) and hallux (big toe), though humans have reduced hallux opposition adapted for bipedalism.[1] These features support advanced manipulative abilities and, in varying degrees, knuckle-walking or bipedal locomotion, with humans uniquely obligately bipedal.[1] While behavioral traits like tool use and self-recognition in mirrors are observed across the family, they are not strictly definitional but correlate with the anatomical substrate.[10] Genetic and fossil evidence reinforces these traits as clade-specific, emerging around 14-16 million years ago in Miocene ancestors.[11]Historical Taxonomy

The taxonomic history of Hominidae reflects shifting understandings of primate relationships, initially emphasizing human exceptionalism and later incorporating evolutionary and molecular evidence. In 1758, Carl Linnaeus established the order Primates, placing humans (Homo sapiens) alongside apes due to shared anatomical traits such as forward-facing eyes and grasping hands, though he distinguished humans in the genus Homo while assigning known apes (orangutans and chimpanzees) to genera like Simia. [12] [13] This grouping acknowledged morphological similarities but maintained hierarchical separations rooted in pre-evolutionary paradigms. By the 19th century, as formalized systems evolved, Hominidae emerged to denote exclusively humans and their presumed ancestors, segregated from Pongidae, which housed great apes (orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees); this bifurcation underscored anthropocentric views prioritizing intellectual and bipedal distinctions over phylogenetic continuity. [14] [1] Charles Darwin's The Descent of Man (1871) argued for a common ancestry between humans and apes based on comparative anatomy and embryology, yet taxonomic practice lagged, retaining Hominidae for humans alone amid sparse fossil evidence. [15] Early 20th-century discoveries, such as Raymond Dart's 1924 description of Australopithecus africanus, expanded Hominidae to include bipedal hominins as transitional forms, but great apes stayed in Pongidae, reflecting a grade-based classification that grouped taxa by adaptive similarity rather than strict ancestry. [16] This era's taxonomy, influenced by figures like William King Gregory, prioritized morphological grades over monophyly, with Hominidae embodying "higher" primates defined by upright posture and tool use. [2] Mid-20th-century biochemical analyses began eroding these divisions; Morris Goodman's 1963 serum protein studies revealed humans clustered more closely with chimpanzees and gorillas than expected, challenging Pongidae's coherence. [17] By the 1970s, cladistic principles—emphasizing shared derived traits (synapomorphies) over overall similarity—combined with emerging DNA hybridization data, prompted Goodman and others to advocate an expanded Hominidae encompassing all great apes and humans as a monophyletic clade, abolishing Pongidae as paraphyletic. [18] This shift gained traction in the 1980s–1990s through mitochondrial DNA and nuclear sequence phylogenies, confirming African apes as human sisters within subfamily Homininae, with orangutans in Ponginae; by 2000, most authorities adopted this structure, reflecting causal realism in descent rather than adaptive typology. [19] [20] Such revisions prioritized empirical genetic divergence times (e.g., human-chimp split ~6–7 million years ago) over traditional morphological weighting. [21]Modern Classification

The modern taxonomic classification of Hominidae, established through cladistic analysis integrating molecular phylogenetics and comparative morphology, recognizes the family as comprising humans and the great apes, excluding gibbons which form the sister family Hylobatidae within superfamily Hominoidea.[1] This framework, formalized in sources such as the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), divides Hominidae into two subfamilies: Ponginae and Homininae.[22] The Ponginae subfamily is monotypic at the genus level, containing only Pongo (orangutans), while Homininae encompasses Gorilla (gorillas), Pan (chimpanzees and bonobos), and Homo (humans).[23] Extant species within Hominidae total eight, distributed as follows:| Subfamily | Genus | Species Count | Species Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ponginae | Pongo | 3 | P. pygmaeus, P. abelii, P. tapanuliensis (recognized as distinct since 2017 based on genomic divergence)[3] |

| Homininae | Gorilla | 2 | G. gorilla, G. beringei |

| Homininae | Pan | 2 | P. troglodytes, P. paniscus |

| Homininae | Homo | 1 | H. sapiens |

Extant Taxa

The family Hominidae includes four extant genera—Pongo, Gorilla, Pan, and Homo—encompassing eight species of great apes, with humans (Homo sapiens) as the sole surviving member of the genus Homo.[24] These taxa are divided into two subfamilies: Ponginae (orangutans) and Homininae (African great apes and humans), reflecting phylogenetic divergence estimated at 12–16 million years ago based on molecular clock analyses.[25] All non-human species face severe threats from habitat loss, poaching, and disease, with global populations critically low as of 2024 assessments.[26] The genus Pongo comprises three species of orangutans, all endemic to Indonesia and critically endangered: the Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus), Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii), and Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), the latter described in 2017 from genetic and morphological evidence in Sumatra's Batang Toru forests.[27] Each species exhibits arboreal lifestyles in peat swamp and rainforest habitats, with P. pygmaeus further subdivided into three subspecies based on Bornean island populations.[28] The genus Gorilla includes two species, both in the Congo Basin and East African highlands: the western gorilla (G. gorilla) and eastern gorilla (G. beringei), each with two subspecies—western: Cross River (G. g. diehli) and western lowland (G. g. gorilla); eastern: mountain (G. b. beringei) and Grauer's/eastern lowland (G. b. graueri).[29] Western gorillas number around 360,000 individuals but declined 60% from 1983–2016 due to Ebola and hunting, while eastern populations, totaling under 6,000, are fragmented by conflict and deforestation.[26] The genus Pan contains two species confined to Central Africa: the common chimpanzee (P. troglodytes) and bonobo (P. paniscus), diverged approximately 1–2 million years ago south of the Congo River.[30] Chimpanzees inhabit savanna-woodland mosaics and forests across four subspecies, with populations estimated at 170,000–300,000 but declining 6% annually; bonobos, restricted to the Democratic Republic of Congo's rainforests, number fewer than 50,000 and exhibit matrilineal social structures distinct from chimpanzee fission-fusion groups.[31]| Hominidae Genus | Extant Species | Habitat Range |

|---|---|---|

| Pongo | P. abelii, P. pygmaeus, P. tapanuliensis | Indonesia (Sumatra, Borneo) |

| Gorilla | G. gorilla (2 subspecies), G. beringei (2 subspecies) | Central/West Africa |

| Pan | P. troglodytes, P. paniscus | Central Africa |

| Homo | H. sapiens (sole species) | Global (origins in Africa) |

Taxonomic Debates

The classification of Hominidae has shifted from a traditional Linnaean approach, where the family encompassed only humans and their bipedal ancestors, to a cladistic framework incorporating all great apes based on shared ancestry and molecular evidence, a change formalized in the late 20th century.[32] This lumping of humans with chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans as "great apes" emphasizes monophyly but sparks debate over human exceptionalism, particularly given the threefold larger human brain size enabling advanced cognition absent in other members.[33] Critics argue that without extant sister taxa to Homo sapiens— the last non-sapiens Homo species extinct around 13,000 years ago—such grouping obscures key divergences like bipedalism and cultural complexity, proposing instead a split to highlight hominid uniqueness.[33] Subfamily divisions within Hominidae remain contentious, with consensus placing orangutans in Ponginae and the African apes plus humans in Homininae, further subdivided into tribes Gorillini (Gorilla) and Hominini (Pan and Homo).[32] Some taxonomists advocate elevating Gorillini to subfamily Gorillinae, citing morphological distinctions like gorillas' specialized folivory and silverback social structure, though molecular data supports retention within Homininae due to closer genetic affinity to Hominini than to Ponginae.[2] Fringe proposals suggest unifying all great apes under genus Homo to eliminate paraphyletic groupings, but this lacks empirical support from phylogenetic analyses and risks distorting divergence timelines estimated at 12-16 million years for Pongo-Homininae split.[34] At the species level, debates persist among extant taxa; for instance, orangutans were long treated as one species (Pongo pygmaeus) until genetic divergence exceeding 3-4% between Bornean and Sumatran populations prompted recognition of two in the 1990s, with a third, P. tapanuliensis, proposed in 2017 based on cranial morphometrics, behavior, and 817 single-nucleotide variants from a single specimen.31245-9) Skeptics question the Tapanuli elevation due to limited sample size and hybridization potential, favoring subspecies status amid ongoing gene flow.[35] Similar lumping-versus-splitting occurs for gorilla subspecies, with eastern (G. beringei) and western (G. gorilla) as full species in some schemes, driven by 0.4% genetic difference and ecological isolation, though IUCN retains subspecies pending fuller genomic data.[32] Fossil assignments fuel further controversy, as in Gigantopithecus blacki, known from Pleistocene teeth in Asia and classified in Ponginae as a sister to Pongo due to shared megadontia and folivorous adaptations, yet some analyses posit closer ties to early hominins via robust jaw similarities, challenging its strict pongine status without postcranial evidence.[36] Within Hominini, early taxa like Australopithecus afarensis face genus reclassification proposals (e.g., to Praeanthropus) based on mosaic traits blurring Homo ancestry, compounded by high intraspecific variation exceeding modern benchmarks and interbreeding signals like 4% Neanderthal admixture in non-African humans.[32] These debates underscore systematics challenges from fragmentary fossils and reticulate evolution, prioritizing molecular clocks over morphology alone.[32]Phylogeny

Molecular Evidence

Molecular analyses, including DNA hybridization and sequencing of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, have provided robust evidence for the phylogenetic relationships within Hominidae, consistently supporting a clade comprising humans (Homo sapiens), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), bonobos (Pan paniscus), gorillas (Gorilla spp.), and orangutans (Pongo spp.), with gibbons (Hylobatidae) as the sister group to this family.[37] Early protein and DNA studies divided Hominidae into Ponginae (orangutans) and Homininae (African apes and humans), a topology reinforced by multi-locus sequence data showing high congruence across independent genomic regions.[38] Within Homininae, molecular evidence places gorillas as basal to a Hominini clade uniting humans and the genus Pan, with bonobos and chimpanzees forming a sister subclade to humans based on shared derived nucleotide substitutions and linkage disequilibrium patterns.[38] Genome-wide comparisons reveal sequence divergences that align with these relationships: human-chimpanzee nucleotide differences average 1.23% in alignable regions, human-gorilla at 1.62%, and human-orangutan at approximately 3.1%, excluding insertions/deletions (indels) which add 3-4% further divergence when factored into total genomic similarity.[39] Including indels and structural variants reduces overall human-chimpanzee similarity to about 96%, highlighting functional differences in non-coding regions despite high coding sequence conservation.[40] These patterns, derived from aligned orthologous sequences, underscore Pan as the closest living relatives to humans, with shared synapomorphies in retrotransposon insertions and gene family expansions distinguishing Hominini from Gorillini.[41] Divergence time estimates from molecular clocks, calibrated against fossil constraints and mutation rates, indicate the human-orangutan split at 12-16 million years ago (mya), gorilla divergence from Pan-human lineage at 8-10 mya, and human-chimpanzee/bonobo split at 5-7 mya, though rate heterogeneity across lineages introduces uncertainty, with some analyses pushing the Pan-human divergence to 12 mya under variable clock models.[42][43] These timelines rely on assumptions of neutral evolution and are cross-validated by ancient DNA from archaic hominins, which confirm deep Pan-human separation without evidence of recent admixture beyond known Neanderthal-Denisovan introgression in humans.[44] Discrepancies between molecular and fossil dates persist, attributed to incomplete lineage sorting and ancestral polymorphism rather than systematic clock violations.[45]Morphological and Fossil Evidence

Morphological synapomorphies defining Hominidae include taillessness, large body sizes from 48 to 270 kg with pronounced sexual dimorphism, a short and broad lumbar region, broadened iliac blades, and enhanced shoulder mobility for suspensory behaviors.[1][8] These traits, evident in both extant and fossil forms, support the monophyly of great apes distinct from hylobatids.[46] Internal phylogenetic relationships receive mixed morphological support. Distance-based morphometric analyses of cranial, mandibular, and postcranial elements consistently recover a Pan-Homo clade excluding gorillas and orangutans, aligning with molecular data through shared features like wrist joint morphology adapted for climbing and suspension.[47][48] However, character-based cladistic methods on discrete traits often yield alternative topologies, such as gorilla-human grouping, due to convergence in robust cranial features or homoplasy in locomotion-related adaptations like knuckle-walking in African apes.[6][49] The fossil record provides chronological brackets for divergences but limited resolution for crown Hominidae due to poor preservation in tropical habitats. Middle Miocene taxa like Pierolapithecus catalaunicus (12.4 million years ago) exhibit early great ape thoracic and limb morphologies suggesting a common ancestor with arboreal suspensory locomotion.[46] Pongine fossils, including Sivapithecus (≈12.5 million years ago) with orangutan-like facial prognathism and thick enamel, indicate an Asian divergence around 14-16 million years ago.[5] For Homininae, Late Miocene forms such as Nakalipithecus nakayamai (10 million years ago) from Kenya display dental traits bridging African ape lineages, potentially near the gorilla split estimated at 8-10 million years ago.[50] Hominin fossils provide denser evidence post-7 million years ago, with Sahelanthropus tchadensis showing anteriorly placed foramen magnum indicative of upright posture, marking early post-orangutan divergence.[5] Yet, confirmed fossils for chimpanzee and gorilla crowns are virtually absent—only isolated Pan-attributed teeth exist—underscoring reliance on stem hominines and the erosive bias of forested environments against bone preservation.[51] This paucity limits morphological corroboration of recent splits, contrasting with abundant hominin transitions toward bipedalism and encephalization.[6]Phylogenetic Controversies

One longstanding debate concerns the branching order within the African great apes clade (Homininae), where molecular data predominantly support a closer relationship between humans (Homo sapiens) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes and P. paniscus) than either is to gorillas (Gorilla gorilla and G. beringei), forming a ((human, chimpanzee) gorilla) topology.[52] This resolution emerged from early protein and DNA studies in the 1960s–1980s, contrasting with morphological assessments that often depicted humans as equidistant or closer to gorillas based on cranial and skeletal traits like robusticity.[53] Incomplete lineage sorting (ILS), where ancestral polymorphisms persist through speciation, explains genomic discordance: approximately 30% of the gorilla genome shows gorilla closer to humans or chimpanzees than the latter are to each other, though this is less frequent near coding regions, suggesting selection preserved the canonical tree in functional areas.[52][54] Such ILS, combined with potential ancient gene flow—evidenced by shared haplotypes across species—challenges strict bifurcating models, with simulations indicating reticulate evolution in up to 11–15% of loci favoring alternative topologies like (human, gorilla) chimpanzee.[55][56] Divergence timing estimates reveal further tensions between molecular clocks and paleontological data, particularly for Homininae splits. Fossil-calibrated molecular clocks initially overestimated the human-chimpanzee split at 10–13 million years ago (Ma), conflicting with hominin fossils like Sahelanthropus tchadensis (dated ~7 Ma) implying a 6–7 Ma divergence; revisions incorporating wild generation times (shorter than captive estimates) in chimpanzees (~22–25 years) and gorillas (~25–30 years) yield earlier dates aligning closer to fossils, around 6–8 Ma for human-chimp and 8–10 Ma for gorilla splits.[57][58] Orangutan divergence (~12–16 Ma) shows less discordance, supported by Southeast Asian fossil apes, but overall, molecular rates vary by locus and calibration, with unlinked genomic regions producing ranges of 5–13 Ma for key nodes, underscoring clock relaxation and substitution rate heterogeneity.[59][60] Fossil evidence integration amplifies controversies, as hominid bones exhibit low heritability and plasticity-induced homoiologies—environmentally driven resemblances mimicking homology—that mislead cladistic analyses; for instance, convergent robusticity in gorillas and early hominins complicates subfamily assignments.[61][62] Extinct taxa like Gigantopithecus blacki (~2 Ma–300 ka) are debated as Hominidae basal to orangutans or convergent pongines, based on dental morphology versus sparse craniodental fossils lacking definitive postcrania.[6] These issues highlight phylogeny reconstruction's sensitivity to data type: while whole-genome phylogenomics favor molecular topologies, fossil-scarce windows (e.g., pre-7 Ma Homininae) limit testing, prompting calls for multi-omic approaches over singular reliance on either dataset.[63][64]Physical Characteristics

Morphology and Anatomy

Hominidae exhibit a tailless body plan, orthograde posture, and a transversely broad thorax, which facilitate suspensory locomotion and distinguish them from other catarrhine primates.[65] These features reflect adaptations for arboreal suspension, with the shoulder girdle and wrist showing enhanced mobility, including modifications enabling greater forearm rotation up to 180 degrees via the hominoid elbow and wrist joint complex.[2] [66] Non-human members display elongated forelimbs relative to hindlimbs, curved phalanges for grasping, and short hands in genera like Gorilla and Homo, contrasting with more elongated cheiridia in Pongo and Pan for clambering.[65] Cranially, Hominidae possess enlarged braincases with increased encephalization quotients relative to body size, exceeding those of other primates; for instance, modern Homo sapiens average approximately 1350 cm³ cranial capacity, while non-human great apes range from 300-500 cm³.[2] The facial skeleton is reduced compared to earlier hominoids, with dental arcades following the formula 2.1.2.3 and molars featuring a bilophodont structure with Y-5 cusps, adaptations linked to folivorous and frugivorous diets.[2] Canine teeth are sexually dimorphic and project less than in cercopithecoids, though pronounced in males of Gorilla and Pongo.[2] Postcranially, the pelvis and lower limbs vary: non-human Hominidae retain flexible, compliant feet suited for knuckle-walking and climbing, with abducted halluces, while humans show derived bipedal traits like a short, broad pelvis, arched feet, and a centrally positioned foramen magnum for upright posture.[65] Sexual dimorphism is marked across the family, with males typically 1.5-2 times larger in body mass and canine size than females, as seen in Pan (males ~40-60 kg, females ~30-40 kg) and Gorilla (males up to 200 kg).[2] Musculature supports powerful upper body propulsion, with conserved hindlimb architecture across taxa enabling both terrestrial and arboreal competence.[65]Size, Variation, and Dimorphism

Hominidae encompass a broad spectrum of body sizes among extant species, ranging from humans averaging approximately 60-90 kg to male gorillas exceeding 200 kg in some subspecies.[67] [68] Sexual size dimorphism, typically quantified by male-to-female body mass ratios, peaks in gorillas (around 2:1) and orangutans, correlating with polygynous social structures and male contest competition for mates, while remaining modest in chimpanzees, bonobos, and especially humans (ratios of 1.1-1.3).[25] [69] In gorillas, adult males of the western lowland subspecies average 136 kg and can reach 227 kg, with females weighing 70-90 kg; mountain gorillas exhibit larger average sizes, with males up to 220 kg, reflecting intraspecific variation influenced by habitat and diet.[67] [68] [25] Chimpanzees show moderate dimorphism, with males ranging 34-70 kg and females 26-50 kg, alongside height estimates of about 120-170 cm when standing bipedally.[70] [71] Bonobos display slightly reduced dimorphism compared to chimpanzees, with males averaging 40-45 kg and females 30-35 kg.[72] Orangutans exhibit high dimorphism, with adult males substantially larger than females—often 1.5-2 times heavier—though precise wild averages vary by island populations (Bornean vs. Sumatran). Humans demonstrate the least dimorphism, with global male averages around 171 cm in height and 62-70 kg in mass, versus females at 159 cm and 55-60 kg, though regional nutrition and genetics drive wide intraspecific variation, such as taller statures in northern European populations.[73] [74] This reduced human dimorphism likely stems from shifts toward monogamous pair-bonding and reduced male-male agonism over evolutionary time.[69]| Genus/Species Example | Male-Female Mass Ratio | Key Variation Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Gorilla gorilla | ~2.0 | Subspecies (mountain > lowland), age, dominance status[68] |

| Pongo spp. | ~1.7-2.0 | Island populations, maturity (flanged males larger) |

| Pan troglodytes | ~1.3 | Geographic range, nutrition[70] |

| Pan paniscus | ~1.2 | Social group dynamics, habitat quality[72] |

| Homo sapiens | ~1.1-1.2 | Latitude (Bergmann's rule), socioeconomic factors[69] [74] |

Comparative Adaptations

Hominidae species display distinct locomotor adaptations reflecting their ecological niches. African great apes—chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas—employ knuckle-walking during terrestrial quadrupedalism, involving flexed wrist joints and weight-bearing on the dorsal surfaces of the middle phalanges, which facilitates efficient ground travel while preserving arboreal climbing capabilities derived from a shared suspensory ancestor.[75] Orangutans, conversely, emphasize orthograde suspension and cautious quadrupedalism in arboreal environments, with elongated forelimbs and hooked hands suited for below-branch progression rather than rapid terrestrial movement.[76] Humans uniquely exhibit obligate bipedalism, supported by a short, broad pelvis for weight transfer, an S-shaped vertebral column for balance, and elongated lower limbs with a valgus knee angle, enabling energy-efficient striding over long distances unattainable by other hominids.[77][78] These locomotor differences correlate with limb proportions and joint morphology. Non-human hominids feature relatively longer forelimbs and shorter hindlimbs, promoting intermembral indices above 100 that favor climbing and suspension, whereas human proportions reverse this pattern with hindlimb dominance (intermembral index around 70-80), optimizing for terrestrial endurance.[79] Biomechanical neck lengths in the femur are elongated in bipedal humans and suspensory apes compared to more quadrupedal primates, enhancing leverage for hindlimb propulsion.[79] Vertebral formulae have diverged from a long-backed common ancestor, with great apes shortening lumbar regions for stability during suspension and humans reducing thoracic vertebrae while stabilizing the lumbar curve against compressive forces.[80] Dietary adaptations manifest in craniofacial and gastrointestinal structures. Gorillas possess massive mandibles, procumbent incisors, and low-crowned molars with thick enamel for grinding fibrous folivores, complemented by enlarged salivary glands and a voluminous gut for fermenting low-quality vegetation.[81] Chimpanzees and bonobos, as opportunistic omnivores, retain honing canines for occasional meat processing and more flexible jaw mechanics for fruits and nuts, though their larger colons support plant-dominant diets.[82] Orangutans exhibit similar frugivorous dentition but with specialized cheek pouches for storing seeds. Humans, post-fire control around 1 million years ago, show reduced facial prognathism, smaller molars, and a simplified gut with expanded small intestine for nutrient absorption from cooked, higher-quality foods including increased animal protein, diverging from the folivorous extremes of other hominids.[82][83] Sensory and integumentary traits also vary adaptively. Great apes maintain dense pelage for thermoregulation in humid forests, with gorillas' sagittal crests anchoring temporalis muscles for mastication amid cooler highland ranges.[84] Humans have lost most body hair, evolving eccrine sweat glands across the skin for evaporative cooling during sustained activity in open environments, alongside a descended larynx facilitating complex vocalization absent in other Hominidae.[85] Olfactory capabilities remain acute in apes for detecting ripe fruits, but human trichromatic vision, enhanced by cone opsin genes shared with Old World primates, supports foraging in varied light conditions.[85]Behavior and Ecology

Social Organization

Hominidae exhibit diverse social structures adapted to ecological pressures, ranging from solitary living in orangutans to cohesive troops in gorillas and dynamic fission-fusion communities in chimpanzees and bonobos.[86] This variation reflects differences in resource distribution, predation risks, and reproductive strategies, with males generally competing for access to females across species.[87] Humans, as the sole surviving hominin, display pair-bonding and cooperative breeding systems that diverge from the multi-male, multi-female or harem structures of other great apes, facilitating biparental care and extended kin networks.[88] Orangutans (genus Pongo) maintain semi-solitary social organization, with adults largely independent except for mother-offspring bonds lasting up to eight years.[89] Flanged adult males defend large ranges and interact opportunistically with females for mating, while unflanged males roam widely with minimal group formation; this solitariness correlates with arboreal fruit foraging in low-density forests.[90] Gorillas (genus Gorilla) form stable, unimale or multimale troops averaging 5-30 individuals, typically led by a dominant silverback male who protects the group, directs movement, and monopolizes mating with 3-8 adult females and their offspring.[91] Silverbacks maintain cohesion through displays and aggression, with females transferring between groups; multimale units occur in some populations, reducing infanticide risks but increasing male competition.[92] Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan paniscus) both operate in fission-fusion societies, where communities of 20-150 members subdivide into fluid parties of 3-20 individuals that merge and split daily based on food availability and social needs.[86] In chimpanzees, male philopatry fosters coalitions for territory defense and dominance hierarchies, with alpha males gaining mating advantages through alliances and aggression.[93] Bonobo communities emphasize female alliances, where matrilineal kin and cross-sex bonds suppress male dominance via frequent sexual interactions, resulting in lower intergroup violence and higher female rank stability—females outrank most males through coalition frequency.[94][95] Human social organization centers on pair bonds, often supplemented by alloparental care from kin, contrasting the promiscuous or harem systems of other Hominidae; this shift likely evolved with provisioning demands of larger-brained offspring and reduced sexual dimorphism.[96] While ancestral hunter-gatherer bands numbered 20-50 with fluid alliances, modern variations include monogamous nuclear families and larger cooperative societies, underpinned by cultural norms rather than strict genetic imperatives.[88]Diet and Foraging

Members of Hominidae display dietary adaptations reflecting their ecological niches, with diets dominated by plant matter but varying in composition across genera. Gorillas primarily consume foliage, stems, and pith, with western gorillas incorporating fruit at up to 43% of intake during abundant seasons, while mountain gorillas rely more heavily on herbaceous vegetation comprising the bulk of their year-round diet.[97] [98] This high-volume, low-quality foraging supports their large body mass through continuous feeding, often exceeding 18 kilograms of material daily in adults.[99] Chimpanzees and bonobos, both in genus Pan, maintain omnivorous frugivorous diets, with ripe fruit accounting for approximately 59% of chimpanzee intake, young leaves 21%, and the remainder including seeds, flowers, insects, and meat from opportunistic hunts of small vertebrates.[100] [101] Bonobos exhibit similar proportions, consuming meat at frequencies comparable to chimpanzees, though their forested habitats may yield higher fruit availability.[102] [103] Foraging in these species involves group travel to fruiting trees, tool-assisted extraction of insects like termites, and seasonal adjustments to fallback foods such as leaves during scarcity.[104] Orangutans forage solitarily for fruit, which forms the core of their diet—up to 90% when seasonally plentiful—supplemented by bark, leaves, shoots, and minor animal items like insects.[105] Immature individuals learn these skills through prolonged maternal association, selectively processing over 300 plant species and employing tools sporadically for food access.[106] [107] In humans, dietary evolution from shared great ape ancestry incorporated greater animal protein and processing techniques, with isotopic evidence showing a shift toward C4 plants and meat consumption by 2.3 million years ago, though modern foraging remnants persist in some populations.[108] [109] Across Hominidae, foraging strategies are constrained by food distribution, prompting ranging patterns that balance energy gain against predation and competition risks.Cognitive and Tool-Use Capacities

Great apes demonstrate advanced cognitive capacities relative to other nonhuman primates, including causal understanding, episodic-like memory, and theory of mind elements such as deception and cooperation in problem-solving tasks.[110] [111] Chimpanzees and orangutans, in particular, excel in tasks requiring inhibitory control and quantity estimation, with performance comparable across species when adjusted for age and experience.[110] Mirror self-recognition, assessed via the mark test, has been reliably demonstrated in chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans, where individuals touch marked areas on their bodies visible only in reflection, indicating visual self-awareness emerging around 2-4 years of age.[112] [113] Gorillas exhibit inconsistent results, with multiple studies reporting failure at the species level despite occasional successes in captive individuals.[114] Tool use among great apes varies by species and context, with chimpanzees displaying the most sophisticated wild behaviors, including hierarchical combinations such as modifying sticks for termite fishing—probe modification followed by insertion—and nut-cracking sequences using selected stones as hammers against woody anvils, requiring foresight in material selection and force application.[115] [116] These behaviors, observed since Jane Goodall's 1960s reports at Gombe, involve sequential actions and are transmitted socially, as evidenced by over 39 behavioral variants differing across chimpanzee communities, such as nut-cracking prevalent in Taï Forest but absent in Gombe despite similar ecology.[117] [118] Bonobos engage in analogous tool use, including stick probing for insects, though wild documentation is sparser due to limited study sites; captive bonobos innovate tools comparably to chimpanzees.[115] Orangutans employ tools in Sumatran and Bornean habitats, such as leaf sponges for water extraction, branch hooks for fruit dislodgement, and seed-extraction tools from bark, with evidence of multi-step planning like transporting unfinished tools.[115] [119] Gorillas rarely use tools in the wild—fewer than 10 confirmed instances, including stick gauging of water depth or foraging probes—potentially linked to their folivorous diet and knuckle-walking reducing manual dexterity needs, though captive gorillas readily adopt simple tools.[120] [115] Across species, tool proficiency develops protractedly, extending into adulthood, with social learning from mothers enhancing efficiency in complex tasks like chimpanzee stick use.[121] These capacities reflect shared evolutionary foundations in Hominidae, enabling adaptive responses to environmental challenges through material intelligence and cultural conformity.[122]Distribution and Habitats

Current Ranges

Homo sapiens occupies a cosmopolitan range across all continents except Antarctica, with populations exceeding 8 billion individuals as of 2023, resulting from migrations out of Africa beginning approximately 60,000–100,000 years ago. Non-human Hominidae are confined to tropical regions of Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The orangutans (Pongo spp.), comprising the Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus), Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii), and Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), are endemic to Indonesia and Malaysia. The Bornean orangutan inhabits Borneo, spanning Indonesian provinces like West and Central Kalimantan and Malaysian Sarawak, primarily in lowland rainforests and peat swamps.[123] The Sumatran orangutan is restricted to northern Sumatra, mainly in Aceh and North Sumatra provinces, favoring highland forests up to 1,500 m elevation.[124] Gorillas (Gorilla spp.) are found exclusively in African forests. The eastern gorilla (G. beringei) includes the mountain gorilla subspecies (G. b. beringei), limited to the Virunga Mountains across Rwanda, Uganda, and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and the eastern lowland gorilla (G. b. graueri), distributed in eastern DRC lowlands, including Kahuzi-Biega and Maiko National Parks.[125] The western gorilla (G. gorilla) features the widespread western lowland gorilla (G. g. gorilla) in Cameroon, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, DRC, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Nigeria, alongside the rarer Cross River gorilla (G. g. diehli) in Nigeria and Cameroon border regions.[126] Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) range across equatorial Africa from Senegal in the west to western Uganda and Tanzania in the east, inhabiting forests, woodlands, and savannas in countries including Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Republic of the Congo, DRC, and Uganda.[127] Bonobos (P. paniscus), the closest relatives to chimpanzees, are restricted to the south bank of the Congo River in the DRC, within a fragmented area of approximately 500,000 km² covering lowland rainforests north of the Kasai and Sankuru Rivers.[128]| Species | Primary Geographic Range | Key Habitats |

|---|---|---|

| Pongo pygmaeus (Bornean orangutan) | Borneo (Indonesia: Kalimantan; Malaysia: Sabah, Sarawak) | Lowland dipterocarp forests, peat swamps |

| Pongo abelii (Sumatran orangutan) | Northern Sumatra (Indonesia: Aceh, North Sumatra) | Highland rainforests, peat forests |

| Gorilla beringei (Eastern gorilla) | Eastern DRC, Rwanda, Uganda | Montane cloud forests, lowland forests |

| Gorilla gorilla (Western gorilla) | West-central Africa (Cameroon to DRC) | Lowland rainforests, swamp forests |

| Pan troglodytes (Chimpanzee) | West to east equatorial Africa (Senegal to Tanzania) | Tropical forests, savannas, woodlands |

| Pan paniscus (Bonobo) | Southern DRC (Congo River basin) | Lowland rainforests south of Congo River |

Environmental Adaptations

Non-human members of Hominidae, including chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans, exhibit physiological and behavioral adaptations primarily suited to tropical forest habitats in Africa and Southeast Asia, where they navigate dense canopies and understories for foraging and predator avoidance. Orangutans demonstrate specialized arboreal traits, such as elongated forelimbs relative to hindlimbs and highly flexible shoulder joints, enabling efficient brachiation and suspension from branches to access fruit and foliage in the upper canopy layers of Bornean and Sumatran rainforests.[8] Chimpanzees and gorillas, while also forest-dwellers, incorporate semi-terrestrial strategies; chimpanzees use knuckle-walking for ground travel in savanna-woodland mosaics and employ tools like sticks for termite extraction, adapting to variable fruit availability and seasonal dry periods through flexible foraging patterns.[130] Gorillas, larger and more folivorous, have robust dentition and digestive systems optimized for processing fibrous vegetation on forest floors, with silverback males' size providing thermoregulatory benefits via reduced surface-to-volume ratios in humid, shaded environments.[1] Genetic evidence reveals local adaptations among wild chimpanzees to habitat variations, such as enhanced immune responses to pathogens like malaria in denser equatorial forests versus heat-tolerance traits in drier savanna fringes, reflecting ongoing natural selection pressures from ecological heterogeneity.[131] These adaptations underscore a reliance on stable, resource-rich tropical niches, with limited dispersal beyond forested zones due to physiological constraints like inefficient long-distance terrestrial locomotion and high water dependencies tied to frugivorous diets.[132] In humans, the sole Hominidae species with global distribution, environmental adaptations emphasize behavioral plasticity and cultural innovations over specialized morphology, enabling habitation from Arctic tundras to high-altitude plateaus and arid deserts since at least 3 million years ago. Physiological responses include eccrine sweat glands for evaporative cooling in hot climates, allelic variations like EPAS1 for hypoxia tolerance at elevations above 4,000 meters in Tibetan populations, and depigmented skin in northern latitudes to maximize vitamin D synthesis under low ultraviolet radiation.[133] [134] Technological mitigations, such as fire control for cooking and warmth (evident from 1.5-million-year-old hearths), insulated clothing from animal hides, and constructed shelters, have decoupled human physiology from climatic extremes, allowing persistence amid Pleistocene fluctuations in temperature and aridity.[135] This versatility, driven by cognitive capacities for planning and resource modification, contrasts with the niche conservatism of other Hominidae and correlates with expansions into biomes previously inhospitable to early hominins.[136]Historical Distributions from Fossils

The fossil record of Hominidae reveals an African origin during the late Oligocene to early Miocene, with the earliest definitive hominoid remains, such as those of Proconsul, discovered in East African sites like Kenya and Uganda, dating to approximately 23–17 million years ago (Ma). These primates inhabited forested environments across what is now eastern Africa, marking the initial diversification of the family before significant dispersals.[137][138] By the Middle Miocene, around 16–11 Ma, Hominidae expanded into Eurasia via hypothesized land bridges or dispersals from Africa, as evidenced by fossils of Dryopithecus in southern Europe (e.g., Spain, France, Germany) and Sivapithecus in northern India and Pakistan. These taxa, adapted to woodland habitats, indicate a broad Eurasian radiation, with Sivapithecus linked to the pongine lineage (orangutans) based on cranial and dental morphology. Further east, early Miocene to Middle Miocene forms appeared in Southeast Asia, though fragmentary.[139][140] Late Miocene developments, circa 11–5 Ma, featured a hominine radiation primarily in southern Europe and Anatolia, including Ouranapithecus from Greece (~9.6 Ma) and the recently identified Anadoluvius from Turkey (~8.7 Ma), suggesting these apes temporarily occupied Mediterranean woodlands before local extinctions around 9 Ma. Concurrently, African sites yielded Nakalipithecus in Kenya (~10 Ma) and other forms, underscoring ongoing continental presence amid climatic shifts toward drier conditions.[141][142] In the Pliocene (5.3–2.6 Ma) and Pleistocene (2.6 Ma–11,700 years ago), distributions contracted: European hominoids vanished, with no significant post-Miocene ape fossils there, while African great ape lineages left sparse dental remains, contrasting the proliferation of bipedal hominins in East and South Africa. Asian pongines endured, with Pongo fossils in southern China, Vietnam, and Indonesia (~2 Ma onward), and the giant Gigantopithecus blacki ranging across southern China, Vietnam, and possibly Thailand from ~2 Ma to ~300,000 years ago, exploiting bamboo-rich forests until late Pleistocene extinction. This pattern reflects habitat fragmentation and competition, with modern Hominidae distributions echoing these ancient vicariances.[6][143][51]Fossil Record

Miocene Origins