Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

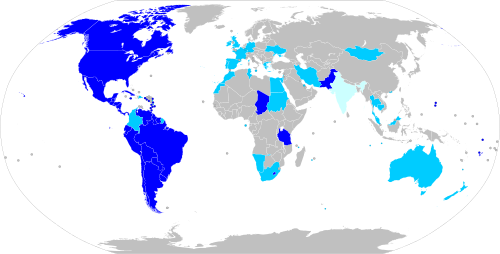

Multiple citizenship

View on Wikipedia

| 2 years 2.5 years 3 years 4 years 5 years 7 years | 8 years 9 years 10 years 12 years 14 years 15 years | 20 years 25 years 30 years 35 years No naturalization allowed Not stated by law or varies No data |

Multiple citizenship (or multiple nationality) is a person's legal status in which a person is at the same time recognized by more than one country under its nationality and citizenship law as a national or citizen of that country. There is no international convention that determines the nationality or citizenship status of a person, which is consequently determined exclusively under national laws, which often conflict with each other, thus allowing for multiple citizenship situations to arise.

A person holding multiple citizenship is, generally, entitled to the rights of citizenship in each country whose citizenship they are holding (such as right to a passport, right to enter the country, right to work, right to own property, right to vote, etc.) but may also be subject to obligations of citizenship (such as a potential obligation for national service, becoming subject to taxation on worldwide income, etc.).

Some countries do not permit dual citizenship or only do in certain cases (e.g., inheriting multiple nationalities at birth). This may be by requiring an applicant for naturalization to renounce all existing citizenship, or by withdrawing its citizenship from someone who voluntarily acquires another citizenship. Some countries permit a renunciation of citizenship, while others do not. Some countries permit a general dual citizenship while others permit dual citizenship but only of a limited number of countries.

A country that allows dual citizenship may still not recognize the other citizenship of its nationals within its own territory (e.g., in relation to entry into the country, national service, duty to vote, etc.). Similarly, it may not permit consular access by another country for a person who is also its national. Some countries prohibit dual citizenship holders from serving in their armed forces or on police forces or holding certain public offices.[1]

History

[edit]Up until the late 19th century, nations often decided whom they claimed as their citizens or subjects and did not recognize any other nationalities they held. Many states did not recognize the right of their citizens to renounce their citizenship without permission because of policies that originated with the feudal theory of perpetual allegiance to the sovereign. This meant that people could hold multiple citizenships, with none of their nations recognizing any other of their citizenships. Until the early modern era, when levels of migration were insignificant, this was not a serious issue. However, when non-trivial levels of migration began, this state of affairs sometimes led to international incidents, with countries of origin refusing to recognize the new nationalities of natives who had migrated, and, when possible, conscripting natives who had naturalized as citizens of another country into military service. The most notable example was the War of 1812, triggered by British impressment into naval service of US sailors who were alleged to be British subjects.[2][3]

In the aftermath of the 1867 Fenian Rising, Irish-born naturalized American citizens who had gone to Ireland to participate in the uprising were caught and charged with treason, as the British authorities considered them to be British subjects. This outraged many Irish-Americans, to which the UK responded by pointing out that, just like British law, US law also recognized perpetual allegiance.[2] As a result, Congress passed the Expatriation Act of 1868, which granted Americans the right to freely renounce their US citizenship. The UK followed suit, and starting from 1870 British subjects who naturalized as US citizens lost their British nationality. During this time, diplomatic incidents had also arisen between the US and several other European countries over their tendency to conscript naturalized US citizens visiting their former homelands. In addition, many 19th century European immigrants to the United States eventually returned to their homelands after naturalizing as US citizens and in some cases then attempted to use their US citizenship for diplomatic protection. The US State Department had to decide which US citizens it should protect and which were subjected to local law, resulting in tensions with immigrant communities in the US and European governments. In 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant, in his annual message to Congress, decried the phenomenon of people "claiming the benefit of citizenship, while living in a foreign country, contributing in no manner to the performance of the duties of a citizen of the United States, and without intention at any time to return and undertake those duties, to use the claims to citizenship of the United States simply as a shield from the performance of the obligations of a citizen elsewhere." The US government negotiated agreements with various European states known as the Bancroft Treaties from 1868 to 1937, under which the signatories pledged to treat the voluntary naturalization of a former citizen or national with another sovereign nation as a renunciation of their citizenship.[2][3][4]

The theory of perpetual allegiance largely fell out of favor with governments during the late 19th century. With the consensus of the time being that dual citizenship would only lead to diplomatic problems, more governments began prohibiting it and revoking the nationality of citizens holding another nationality. By the mid-20th century, dual nationality was largely prohibited worldwide, although there were exceptions. For example, a series of United States Supreme Court rulings permitted Americans born with citizenship in another country to keep it without losing their US citizenship.[2][5] Most nations revoked the nationality of their citizens who naturalized in another nation, as well as if they displayed significant evidence of political or social loyalty to another nation such as military service, holding political office, or even participating in elections. In some cases, naturalization was conditional on renunciation of previous citizenship. Many nations attempted to resolve the issue of dual citizenship emanating from people born in their territory but who inherited citizenship under the laws of another nation by requiring such individuals to choose one of their nationalities upon reaching the age of maturity. The US State Department, invoking provisions of the Bancroft treaties, systematically stripped US citizenship from naturalized US citizens who returned to live in their native countries for extended periods of time. However, in the absence of multilateral cooperation regarding dual nationality, enforcement was leaky. Many individuals continued to hold dual nationality by circumstance of birth, including most children born in the US to non-citizen parents.[6][3][2]

At the League of Nations Codification Conference, 1930, an attempt was made to codify nationality rules into a universal worldwide treaty, the 1930 Hague Convention, whose chief aims would be to completely abolish both statelessness and dual citizenship. The 1930 Convention on Certain Questions Relating to the Conflict of Nationality Laws proposed laws that would have reduced both but, in the end, were ratified by only 20 nations.[2] One significant development that emerged was the Master Nationality Rule, which provided that "a State may not afford diplomatic protection to one of its nationals against a state whose nationality such person also possesses."

Although fully eliminating dual nationality proved to be legally impossible during this time, it was subjected to fierce condemnation and social shaming. It was framed as disloyalty and widely compared to bigamy.[3] George Bancroft, the American diplomat who would later go on to negotiate the first of the Bancroft treaties, which were named for him, stated in 1849 that nations should "as soon tolerate a man with two wives as a man with two countries; as soon bear with polygamy as that state of double allegiance."[4] In 1915, former US President Theodore Roosevelt published an article deriding the concept of dual nationality as a "self-evident absurdity." Roosevelt's article was spurred by the case of P.A. Lelong, a US citizen born in New Orleans to French immigrant parents. He had planned to travel to France on business but had been warned that he might be conscripted to fight in World War I, and when he contacted the State Department for assurances that "my constitutional privileges as an American citizen follow me wherever I go", he was informed that France would regard him as a citizen under its jus sanguinis laws, and that the State Department could give no assurances regarding his liability for military service if he voluntarily placed himself in French jurisdiction.[2]

However, the consensus against dual nationality began to erode as a result of changes in social mores and attitudes. By the late 20th century, it was becoming gradually accepted again.[2] Many states were lifting restrictions on dual citizenship. For example, the British Nationality Act 1948 removed restrictions on dual citizenship in the UK, the 1967 Afroyim v. Rusk ruling by the US Supreme Court prohibited the US government from stripping citizenship from Americans who had dual citizenship without their consent, and the Canadian Citizenship Act, 1976, removed restrictions on dual citizenship in Canada. The number of states allowing multiple citizenships further increased after a treaty in Europe requiring signatories to limit dual citizenship lapsed in the 1990s, and countries with high emigration rates began permitting it to maintain links with their respective diasporas.[7]

Types of laws

[edit]

Each country sets its own criteria for citizenship and the rights of citizenship, which change from time to time, often becoming more restrictive. For example, until 1982, a person born in the UK was automatically a British citizen; this was subjected to restrictions from 1983. These laws may create situations where a person may satisfy the citizenship requirements of more than one country simultaneously. This would, in the absence of laws of one country or the other, allow the person to hold multiple citizenships. National laws may include criteria as to the circumstances, if any, in which a person may concurrently hold another citizenship. A country may withdraw its own citizenship if a person acquires a citizenship of another country, for example:

- Citizenship by descent (jus sanguinis). Historically, citizenship was traced through the father, but today, most countries permit the tracing through either parent and some also through a grandparent. Today, the citizenship laws of most countries are based on jus sanguinis. In many cases, this basis for citizenship also extends to children born outside the country, and sometimes even when the parent has lost citizenship.

- Citizenship by birth on the country's territory (jus soli). The US, Canada, and many Latin American countries grant unconditional birthright citizenship. To stop birth tourism, most countries have abolished it; while Australia, France, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa, and the UK have a modified jus soli, which requires at least one parent to be a citizen of the country (jus sanguinis) or a legal permanent resident who has lived in the country for several years. In the majority of such countries—for example, in Canada—children born to diplomats and to people outside the jurisdiction of the soil are not granted citizenship at birth. It is usually conferred automatically on the children once one of the parents obtains citizenship.[8][failed verification]

- Citizenship by marriage (jus matrimonii). Some countries routinely give citizenship to spouses of its citizens or may shorten the time for naturalization but only in a few countries is citizenship granted on the wedding day (e.g., Iran).[9] Some countries have regulations against sham marriages (e.g., the US), and some revoke the spouse's citizenship if the marriage terminates within a specified time (e.g., Algeria).

- Citizenship by naturalization.

- Citizenship by adoption. A minor adopted from another country when at least one adoptive parent is a citizen.[10]

- Citizenship by investment. Some countries give citizenship to people who make a substantial monetary investment in their country.[11] There are two countries in the European Union where this is possible: Malta and Cyprus; as well as the five Caribbean countries of Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Dominica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Saint Lucia. Additionally, the countries of Vanuatu, Montenegro, Turkey, and Jordan offer citizenship by investment programs. Most of these countries grant citizenship immediately, provided that due diligence is passed, without a requirement for any physical presence in the country. Malta requires one year of residency before citizenship can be given. Portugal offers a permanent residence program by investment, but there is a five-year timeline with periodic short visits in order to be eligible to obtain citizenship. Cambodia has laws enacted that allow foreigners to obtain citizenship through investment, but it is difficult to receive without fluency in Khmer.[12] The countries of Comoros, Nauru, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Tonga, and Moldova previously had citizenship by investment programs; however, these programs have been suspended or discontinued.

- Some countries grant citizenship based on ethnicity and on religion: Israel gives all Jews the right to immigrate to Israel, by the Law of Return, and fast-tracked citizenship. Dual citizenship is permitted, but, when entering the country, the Israeli passport must be used.[13]

- Citizenship by holding an office (jus officii). In the case of Vatican City, citizenship is based on holding an office, with Vatican citizenship held by the Pope, cardinals residing in Vatican City, active members of the Holy See's diplomatic service, and other directors of Vatican offices and services. Vatican citizenship is lost when the term of office comes to an end, and children cannot inherit it from their parents. Since Vatican citizenship is time-limited, dual citizenship is allowed, and persons who would become stateless because of loss of Vatican citizenship automatically become Italian citizens.[14]

Once a country bestows citizenship, it may or may not consider a voluntary renunciation of that citizenship to be valid. In the case of naturalization, some countries require applicants for naturalization to renounce their former citizenship. For example, the US Chief Justice John Rutledge ruled "a man may, at the same time, enjoy the rights of citizenship under two governments",[15] but the US requires applicants for naturalization to swear to an oath renouncing all prior "allegiance and fidelity" to any other nation or sovereignty as part of the naturalization ceremony.[16] However, some countries do not recognise one of its citizens renouncing their citizenship. Effectively, the person in question may still possess both citizenships, notwithstanding the technical fact that they may have explicitly renounced one of the country's citizenships before officials of the other. For example, the UK recognizes a renunciation of citizenship only if it is done with competent UK authorities.[17][18] Consequently, British citizens naturalized in the US remain British citizens in the eyes of the UK government even after they renounce British allegiance to the satisfaction of US authorities.[14]

Irish nationality law applies to the whole of the island of Ireland, which at present is divided politically between the sovereign Republic of Ireland, which has jurisdiction over the majority of Ireland, and Northern Ireland, which consists of six of the nine counties of the Irish province of Ulster, and is part of the United Kingdom. People in Northern Ireland are therefore "entitled to Irish, British, or both" citizenships.

Between 1999 and 24 June 2004, anyone born on the island of Ireland was entitled to Irish citizenship automatically. Since 24 June 2004 Irish citizenship has been granted to anyone born on the island of Ireland who has one, or both, parents who; are Irish citizens or British citizens, were entitled to live in Ireland without any residency restrictions, or was legally resident on the island of Ireland for three out of the four years immediately before their birth (excluding residence on a student visa, awaiting an international protection decision or residence under a declaration of subsidiary protection).[19][14]

Prevention of multiple citizenship

[edit]Some countries may take measures to avoid creation of multiple citizenship. Since a country has control only over who has its citizenship but has no control over who has any other country's citizenship, the only way for a country to avoid multiple citizenship is to deny its citizenship to people in cases when they would have another citizenship. This may take the following forms:

- Automatic loss of citizenship if another citizenship is acquired voluntarily, such as Austria,[20] Azerbaijan,[21] Bahrain, China (with the exception of Hong Kong and Macau, which allow multiple citizenship in parallel with Chinese citizenship, but prevent consular protection of the involved nation in their own and also in Mainland China),[22] India,[23] Indonesia,[24] Japan,[25] Kazakhstan,[26] Malaysia,[27] Nepal,[28] and Singapore.[29] Saudi Arabian citizenship may be withdrawn if a Saudi citizen obtains a foreign citizenship without the permission of the Prime Minister.[30] The Netherlands, which have some exceptions to dual citizenship's admission, such loss, in practice, is not automatic and may depend on the knowledge and the initiative of the executive power to take place.

- Possible (but not automatic) loss of citizenship if another citizenship is acquired voluntarily, such as South Africa.[31]

- Possible (but not automatic) loss of citizenship if people with multiple citizenships do not renounce their other citizenships after reaching the age of majority or within a certain period of time after obtaining multiple citizenships, such as Indonesia,[24] Japan,[32] and Montenegro (where such loss is automatic but with some exceptions).[33]

- Denying automatic citizenship by birth if the child may acquire another citizenship automatically at birth.

- Requiring applicants for naturalization to apply to renounce their existing citizenship(s) and provide proof from those countries that they have renounced the citizenship.

Multiple citizenship not recognized

[edit]A statement that a country "does not recognize" multiple citizenship is confusing and ambiguous. Often, it is simply a restatement of the Master Nationality Rule, whereby a country treats a person who is a citizen of both that country and another in the same way as one who is a citizen only of the country. In other words, the country "does not recognize" that the person has any other citizenship for the purposes of the country's laws. In particular, citizens of a country may not be permitted to use another country's passport or travel documents to enter or leave the country, or be entitled to consulate assistance from the other country.[34] Also, the dual national may be subject to compulsory military service in countries where they are considered to be nationals.[35]

Complex laws on dual citizenship

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

Some countries have special rules relating to multiple citizenships, such as:

- Some countries allow dual citizenship but restrict the rights of dual citizens:

- in Egypt and Armenia, dual citizens cannot be elected to Parliament.

- in Israel, diplomats and members of Parliament must renounce any other citizenship before assuming their job.

- in Colombia, dual citizens cannot be Ministers of foreign affairs and of defense.

- in Australia, dual citizens cannot be elected to federal Parliament.[36] In the 2017–18 Australian parliamentary eligibility crisis, 15 members of Parliament were found to have been ineligible for election due to holding another citizenship, although most had not been aware of the fact. In many instances,[37] the affected members of Parliament subsequently renounced any other citizenships, before contesting again in subsequent by-elections (that were triggered by their own prior ineligibility) or general elections.

- in New Zealand, dual citizens may be elected to Parliament, but MPs once elected may not voluntarily become a citizen of another country, or take any action to have their foreign nationality recognised such as applying for a foreign passport. However, the only person to recently violate this, Harry Duynhoven, was protected by the passage of retroactive law.

- in the Philippines, dual citizens by naturalization cannot run for any local elective office. However, dual citizens by birth are eligible to run and be elected.[38]

- in the independent states of the Commonwealth Caribbean, nationals of any Commonwealth country who meet local residency requirements are eligible to vote in elections and run for parliament, with one complicated caveat. Each of those countries has a provision barring anyone who "is by virtue of his own act, under any acknowledgment of allegiance, obedience or adherence to a foreign power or state" (to quote a representative provision from the constitution of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines[39]) from becoming a member of parliament. The precise meaning of those provisions is disputed and is the subject of separate ongoing legal disputes in the countries.[40][41][42]

- in Kenya, dual citizens may not be elected or appointed to any state office or serve in the armed forces unless their second citizenship was obtained involuntarily, without the ability to opt out.[43]

- Austria permits dual citizenship only for persons who had obtained another citizenship by birth.[44] Austrians can apply for special permission to keep their citizenship (Beibehaltungsgenehmigung) before taking a second one (for example, both Austria and the US consider Arnold Schwarzenegger a citizen). In general, however, any Austrian who takes up second citizenship will automatically lose Austrian citizenship.

- Until June 26, 2024, Germany restricted dual citizenship. Since August 2007, in cases of naturalization, Germany accepted dual citizenship if the other citizenship was either one of an EU member country or Swiss citizenship so that permission was not required anymore in these cases, and in some exceptional cases, non-EU and non-Swiss citizens can keep their old citizenship when they become citizens of Germany. For more details, see German nationality law § Dual citizenship. Owing to changes of the German law on dual citizenship, children of non-EU legal permanent residents can have dual citizenship if they were born and grew up in Germany (the foreign-born parents usually cannot have dual citizenship themselves).[citation needed] As of June 27, 2024, an Act to modernize the Nationality Act (StARModG) provides that Germany now accepts dual citizenship in all cases. German citizens no longer lose their citizenship if they acquire a foreign one and foreigners who choose to become German are no longer required to give up ties to their home country.[45] However, the new law is not retroactive and does not automatically restore citizenship to anyone who lost it because of dual citizenship restrictions under the previous law.[46]

- Acquisition of the nationality of Andorra, France, Portugal, the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea or Iberoamerican countries, is not sufficient to cause the loss of Spanish nationality by birth.[47] Spain has dual citizenship treaties with Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela; Spaniards residing in these countries or territories do not lose their rights as Spaniards if they adopt that nationality.[48] For all other countries, Spanish citizenship is lost three years after the acquisition of the foreign citizenship unless the individual declares officially their will to retain Spanish citizenship (Spanish nationality law).[49] Upon request Spain has allowed persons from Puerto Rico to acquire Spanish citizenship.[50][51] On the other hand, foreign nationals who acquire Spanish nationality must relinquish their previous nationality, unless they are natural-born citizens of an Iberoamerican country, Andorra, the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea or Portugal even if these countries do not grant their citizens a similar treatment, or Sephardi Jews. See also the section on "dormant" citizenship.[citation needed]

- Prior to 2011, South Korea did not permit multiple nationalities and for such a person, the nationality was stripped after that person became the age of 22. Since 2011, a person can hold multiple nationalities if they have multiple nationalities by birthright (i.e. not by naturalization) and explicitly takes an oath not to exercise the other nationality inside the jurisdiction of South Korea.[52] For details, see South Korean nationality law § Dual citizenship.

- South Africa has required its citizens to apply for, and obtain, permission from the Minister of Home Affairs to retain their citizenship prior to acquiring the citizenship of another country via any voluntary and formal act (other than marriage) if over the age of majority, and failure to do so has resulted in the automatic loss of South African citizenship upon acquiring another country's citizenship.[53] On 13 June 2023, the Supreme Court of Appeal struck down the relevant legislation as being inconsistent with the Constitution of South Africa and ordered the reinstatement of South African citizenship for those who lost their citizenship in this manner;[54] the judgement however requires confirmation by the Constitutional Court,[55] which is pending as of July 2023.

- Turkey requires Turkish citizens who apply for another nationality to inform Turkish officials (the nearest Turkish embassy or consulate abroad) and provide the original naturalization certificate, Turkish birth certificate, marriage certificate (if applicable) and two photographs. Dual nationals are not compelled to use a Turkish passport to enter and leave Turkey; it is permitted to travel with a valid foreign passport and the Turkish national ID card.[56]

- Pakistan allows dual citizenship on an inclusionary basis since 1951 with 20 countries: Australia, Bahrain, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Jordan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[57]

- In contrast, Bangladesh allows dual citizenship on an exclusionary basis – only with Non-Resident Bangladeshis who are not previously citizens of SAARC countries.[58]

- In Poland, a Polish citizen who is a dual national of another country is legally treated in the same way as a Polish citizen with one nationality. They cannot exercise additional rights and duties that come from their second citizenship in relation to the Polish government. However, submitting a passport of another country to the border guards is not forbidden and there are no penalties in the law. If the citizen does so, they are going to be treated as a citizen of another country. However, when the border guards find out that the person also has Polish citizenship, they are going to treat them as a Polish citizen only, and they are not going to be able to leave (or enter) Poland only using their foreign passport. Since then, they are obliged to show them their Polish passport.[59]

- The same principle as Poland is enforced in France, but when being in one of the country they are citizen of, the plural-national is not allowed to request French consular help. For example, a citizen of both France and Italy, they cannot request help from French consulate in Italy and they cannot request Italian consular help in France.[60]

Partial citizenship, and residency

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

Many countries allow foreigners or former citizens to live and work. However, for voting, being voted and working for the public sector or the national security in a country, citizenship of the country concerned is almost always required.

- Since 2008, Poland has granted the "Polish Card" (Karta Polaka) to ethnic Poles who can prove they have Polish ancestors and knowledge of the Polish language and declare their Polish ethnicity in written form. Holders of the Card are not regarded as citizens, but enjoy some privileges other foreigners do not, e.g. entry visa, right to work, education, or healthcare in Poland. As stated above, Poland currently has no specific laws on dual citizenship; second citizenship is tolerated, but not recognized.

- Turkey allows its citizens to have dual citizenship if they inform the authorities before acquiring the second citizenship (see above), and former Turkish citizens who have given up their Turkish citizenship (for example, because they have naturalized in a country that usually does not permit dual citizenship, such as Germany, Austria or the Netherlands) can apply for the "Blue Card" (Mavi Kart), which gives them some citizens' rights back, e.g. the right to live and work in Turkey, the right to possess land or the right to inherit, but not, for example, the right to vote.

- Overseas citizenship of India (OCI): The Indian government introduced OCI in 2005. The OCI is applicable to people who fall in the category of Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) and migrated from India acquiring citizenship of a foreign country apart from Pakistan and Bangladesh. They are eligible for OCI after renouncing their Indian citizenship as long as their home country allows dual citizenship in some form or other under their relevant national laws.[61][62][63] The Constitution of India does not permit dual citizenship or dual nationality, except for minors where the second nationality was involuntarily acquired. Indian authorities interpreted this to mean a person cannot have another country's passport while simultaneously holding an Indian one, even for a child claimed by another country as its citizen, who may be required by the laws of this country to use the corresponding passports for foreign travel (such as a child born in the United States to Indian parents). Indian courts have given the executive branch wide discretion over this matter. The OCI does not grant political rights to the holder.[64][65]

- In 2005, India amended the 1955 Citizenship Act to introduce a form of overseas citizenship,[66] which stops just short of full dual citizenship and is, in all aspects, like permanent residency. Such overseas citizens are exempt from the rule forbidding dual citizenship; they may not vote, run for office, join the army, or take up government posts, though these evolving principles are subject to revolving political discretions [clarification needed] for those born in India with birthrights. Moreover, people who have acquired citizenship in Pakistan or Bangladesh are not eligible for overseas citizenship. Indian citizens do not need a visa to travel to and work in Nepal or Bhutan (and vice versa), but none of the three countries allow dual citizenship.[67]

- Many countries (e.g. United States, Canada, all EU countries and Switzerland, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore) issue permanent residency status to foreigners deemed eligible. This status generally authorises a person to live and work in the issuing country indefinitely. There is not always any right to vote in the host country, and there may be other restrictions (no consular protection) and rights (not subject to military conscription). Permanent residents may usually apply for citizenship after several years of residency. Depending both on the home country and the guest country, dual citizenship may or may not be permitted.

- Some countries have concluded treaties regulating travel and access to employment: A citizen of an EU country can live and work indefinitely in other EU countries and the four EFTA countries, and citizens of the EFTA countries can live and work in EU countries. Such EU citizens can vote in EU elections, but not national elections, though permitted to vote in local elections where they reside permanently. The Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement between Australia and New Zealand allows their citizens to live and work in the other country.

- A citizen of a GCC member state (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates) can live and work in other member states, but dual citizenship (even with another GCC state) is not allowed. In 2021, UAE approved amendments in the Emirati Nationality Law to allow investors, professionals, special talents and their families to acquire the Emirati nationality and passport under certain conditions.[68][69]

Dominant and effective nationality

[edit]The potential issues that dual nationality can pose in international affairs have long been recognized, and as a result, international law recognizes the concept of "dominant and effective nationality", under which a dual national will hold only one dominant and effective nationality for the purposes of international law to one nation that holds their primary national allegiance, while any other nationalities are subordinate. The theory of dominant and effective nationality emerged as early as 1834. Customary international law and precedent have since recognized the idea of dominant and effective nationality, with the Nottebohm case providing an important shift.

The International Court of Justice defines effective nationality as a "legal bond having as its basis a social fact of attachment, a genuine connection of existence, interests and sentiments, together with the existence of reciprocal rights and duties". International tribunals have adopted and used the principle. Under customary international law, tribunals dealing with questions involving dual nationality must determine the effective nationality of the dual national by determining to which nation the individual has more of a "genuine link". Unlike dual nationality, one may only be the effective national of a single nation, and different factors are taken into consideration to determine effective nationality, including habitual residence, family ties, financial and economic ties, cultural integration, participation in public life, armed forces service, and evidence of sentiment of national allegiance.[70]

Countries that do not allow renunciation of citizenship

[edit]Source: German Federal Government (as of July 2023)

- Africa: Algeria, Angola, Eritrea, Morocco, Nigeria, and Tunisia

- The Americas: Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Uruguay

- Asia: Afghanistan, Iran, Lebanon, Syria, and Thailand

Citizens of these countries may keep their old citizenship if naturalizing in a country that forbids dual citizenship[vague] or that country may refuse their naturalization.

Dormant citizenship and right of return

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

The concept of a "dormant citizenship" means that a person has the citizenships of two countries, but as long as while living permanently in one country, their status and citizen's rights in the other country are "inactive". They will be "reactivated" when they move back to live permanently in the other country. This means, in spite of dual citizenship, only one citizenship can be exercised at a time.

The "dormant citizenship" exists, for example, in Spain: Spanish citizens who have naturalized in an Iberoamerican country and have kept their Spanish citizenship are dual citizens, but have lost many of the rights of Spanish citizens resident in Spain—and hence the EU—until they move back to Spain. Some countries offer former citizens or citizens of former colonies of the country a simplified (re-)naturalization process. Depending on the laws of the two countries in question, dual citizenship may or may not be allowed. For details, see right of return.[71]

Another example of "dormant citizenship" (or "hidden citizenship") occurs when a person is automatically born a citizen of another country without officially being recognized. In many cases, the person may even be unaware that they hold multiple citizenship. For example, because of the nationality law in Italy, a person born in Canada to parents of Italian ancestry may be born with both Canadian and Italian citizenship at birth. Canadian citizenship is automatically acquired by birth within Canada. However, that same person may also acquire Italian citizenship at birth if at least one parent's lineage traces back to an Italian citizen. The person, their parent, grandparent, great-grandparent, and great-great-grandparent may have all transmitted the Italian citizenship to the next child in the line without even knowing it. Therefore, even if the person in this case may have been four generations removed from the last Italian-born (and therefore recognized) citizen, the great-great-grandparent, they would still be born with Italian citizenship. Even though the person may not even be aware of the citizenship, it does not change the fact that they are a citizen since birth. Therefore, the second citizenship (in this case, the Italian citizenship) is "dormant" (or "hidden") because the person does not even know they are a citizen and/or does not have official recognition from the country's government. That person would therefore have to gather all necessary documents and present them to the Italian government so that their "dormant" or "hidden" citizenship will be recognized. Once it is recognized, they will be able to do all of the things that any citizen could do, such as apply for a passport.

Automatic multiple citizenship

[edit]Countries may bestow citizenship automatically (i.e., "by operation of law"), which may result in multiple citizenships, in the following situations:

- Some countries automatically bestow citizenship on a person whose parent holds that country's citizenship. If they have different citizenships or are multiple citizens themselves, the child may gain multiple citizenships, depending on whether and how jus soli and jus sanguinis apply for each citizenship.

- Some countries (e.g., Canada, the US, and many other countries in the Americas) regard all children born there automatically to be eligible to be citizens (jus soli) even if the parents are not legally present. For example, a child born in the US to Austrian parents automatically has dual citizenship with the US and Austria, even though Austria usually restricts or forbids dual citizenship. There are exceptions, such as the child of a foreign diplomat living in the US. Such a child would be eligible to become a lawful permanent resident, but not a citizen, based on the US birth.[72]This has led to birth tourism, so some countries have abolished jus soli or restricted it (i.e., at least one parent must be a citizen or a legal, permanent resident who has lived in the country for several years). Some countries forbid their citizens to renounce their citizenship or try to discourage them from doing so.[14][relevant?]

- Changes in the political status of a nation can render its people involuntary holders of citizenship from multiple countries.For example, if a belligerent state were to successfully invade another sovereign nation, seize and occupy that nation's territory by force, control the movement of people in that territory, and then declare all residents of occupied territory to be citizens of the occupying state.

Some countries are more open to multiple citizenship than others, as it may help citizens travel and conduct business overseas. Countries that have taken active steps towards permitting multiple citizenship in recent years include Switzerland (since January 1, 1992) and Australia (since April 4, 2002).[73][74]

Subnational citizenship

[edit]- Under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. Certain rights accrue as an incident of state citizenship and access to federal courts can sometimes be determined on State citizenship. In addition, Native American tribal sovereignty affords members ("citizens") of federally recognized tribes ("nations") special rights and privileges that derive from federal recognition of customs that predate colonization and rights secured in federal treaties.

- Switzerland has a three-tier system of citizenship – Confederation, canton and commune (municipality).

- Although considered part of the United Kingdom for British nationality purposes, the Crown Dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man have local legislation restricting certain employment and housing rights to those with "local status". Although the British citizenship of people from these islands gives them full citizenship rights when in the United Kingdom, it did not give them the rights that British citizenship generally conferred prior to 2021 when in other parts of the European Union (for example, the right to reside and work). In a similar way, a number of British Overseas Territories have a concept of "belonger status" for their citizens, in addition to their existing British citizenship.

- Citizens of the People's Republic of China may be permanent residents of the Hong Kong or Macau Special Administrative Regions, or have household registration (hukou) somewhere in mainland China. School enrollment, work permission, and other civic rights and privileges (such as whether one may apply for a Hong Kong SAR passport, Macau SAR passport, or People's Republic of China passport are tied to the region in which the citizen has permanent residence or household registration. Although within mainland China the hukou system has loosened in recent years, movement between Macau, Hong Kong, and the mainland remains controlled. Mainland Chinese who migrate to Hong Kong on one-way permits have their mainland hukou cancelled,[75] while children born in Hong Kong to visiting mainland parents cannot receive mainland hukou unless they cancel their Hong Kong permanent residence status.[citation needed]

- People from Åland have joint regional (Åland) and national (Finnish) citizenship. People with Ålandic citizenship (hembygdsrätt) have the right to buy property and set up a business on Åland, but Finns without regional citizenship cannot. Finns can get Ålandic citizenship after living on the islands for five years, and Ålanders lose their regional citizenship after living on the Finnish mainland for five years.[76][77]

- The territorial government of Puerto Rico began issuing Puerto Rican citizenship certificates in September 2007 after Juan Mari Brás, a lifelong supporter of independence, won a successful court victory that validated his claim that Puerto Rican citizenship was valid and can be claimed by anyone born on the island or with at least one parent who was born there.[78]

- In Bosnia and Herzegovina, citizens hold also citizenship of their respective entity, generally that in which they reside. This citizenship can be of the Republika Srpska or of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. One must have citizenship of at least one, but cannot hold both entity citizenships simultaneously.[79]

- In Malaysia, a federation of thirteen states, each state gives certain benefits such as baby bonus, education loans and scholarships to children born in the state (or born to parents who were born in the state) and/or residing in the state. The states of Sabah and Sarawak in East Malaysia each has their own immigration control and permanent residency system; citizens from Peninsular Malaysian states are subject to immigration control in the two states.

- People from the Cook Islands and Niue have New Zealand citizenship, along with a local status that is not extended to other New Zealanders.[80][81][82]

Former instances

[edit]- Germany had state citizenships before these were subsumed into a German national citizenship by the Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich in 1934.

- The use of internal passport to restrict residency and movement in the Soviet Union and in apartheid-era South Africa had the effect of tying local "citizens" to their assigned administrative entity (titular nations and bantustans, respectively).

- Following the federalization of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Czechoslovak citizens also possessed an internal citizenship of either Czechia or Slovakia. Upon the nation's peaceful dissolution in 1993, this was used to determine whether they ought to receive Czech or Slovak citizenship.

- Before the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991, Yugoslav citizens possessed an internal citizenship of their own republic (Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, North Macedonia, Montenegro) as well as Yugoslav citizenship. In Serbia and Montenegro, this system was in effect until 2006.[83]

- When Singapore joined Malaysia in 1963, all Singapore citizens were granted Malaysian citizenship. Singapore citizenship continued to exist as a subnational citizenship, and continued to be legislated by the Legislative Assembly of Singapore subject to the approval of the Parliament of Malaysia. Upon Singapore's independence from Malaysia in 1965, Malaysian citizenship was withdrawn from Singapore citizens, and all Singapore citizens became citizens of the new Republic of Singapore.

- The constitution of Jammu and Kashmir allowed on citizens of the state special privileges i.e. purchase of property, government jobs etc. However, the Government of India revoked article 370 in 2019, providing uniform status of citizenship across the entire nation.

Supra-national citizenship

[edit]- In European Union law, there is the concept of EU citizenship, which flows from the Maastricht Treaty, establishing a legal identity for the European Community. Such citizenship does not replace the member state's citizenship, but is additive in nature, generally conferring rights under EU law and guaranteeing fair treatment broadly equivalent to the treatment a member state's own citizen would receive. However, member states can restrict certain rights, such as voting in national elections and holding specific public roles, to their own citizens. EU citizens can freely live and work in another member state indefinitely. In exceptional cases, a member state may deport or deny entry to citizens of other EU states. Temporary transitional restrictions on free movement rights for citizens of newly admitted states may be imposed for up to 2 years, extendable by an additional 3 years, with an extra 2 years being possible in case of serious labor market disruption. Currently, no such provisions are in effect for any EU member state, though they were previously applied to Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia.[84]

- Mercosur citizenship allows free movement, residence, and work within member countries (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, with Bolivia in accession). Citizens can obtain temporary residency and later apply for permanent status, gaining labor rights, social security, and healthcare access. While political rights are limited, direct voting for the Mercosur Parliament has already been implemented in some member countries. Efforts continue to improve labor mobility and recognize academic qualifications. Mercosur citizens and those from associated states (Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru) do not need a passport or visa to travel around the region, with only a national identity card or other document being required.

- The Nordic Passport Union, containing Denmark (including the Faroe Islands and Greenland, unlike the EU), Sweden, Iceland, Norway (including Svalbard Islands) and Finland, allow citizens of members to travel across their borders without requiring any travel documentation, although this has previously been temporarily suspended in response to the European migrant crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Citizens of members are often eligible for fast track processing to citizenships of other Members, with varying degrees of recognition/tolerance of dual citizenship among the states.

- The United Kingdom recognises a Commonwealth citizenship for the citizens of the member states of the Commonwealth of Nations. The United Kingdom allows non-nationals who are Commonwealth citizens to vote and stand for election while resident there, while most other Commonwealth countries make little or no distinction between citizens of other Commonwealth nations and citizens of non-Commonwealth nations. Notably Commonwealth citizenship no longer imparts a right of residence in the UK.

- Commonwealth of Independent States nations (some republics of the former Soviet Union) are often eligible for fast track processing to citizenships of other CIS countries, with varying degrees of recognition/tolerance of dual citizenship among the states.

Effects and issues

[edit]It is often observed that dual citizenship may strengthen ties between migrants and their countries of origin and increase their propensity to remit funds to their communities of origin.[85]

Qualitative research on the effect of dual citizenship on the remittances, diaspora investments, return migration, naturalization and political behavior finds several ways in which multiple citizenship can affect these categories. As a bundle of rights, dual citizenship (a) enables dual citizens by granting special privileges, (b) affects their expectations about privileges in the decision-making process, and (c) eases the transaction process and reduces costs and risks, for example in the case of investing and conducting business. In addition, a dual legal status can have positive effects on diasporic identification and commitment to causes in the homeland, as well as to a higher naturalization rate of immigrants in their countries of residence.[86]

Dual suffrage

[edit]Multiple citizenship can result in dual transnational voting in contrast to the principle of one man, one vote.[87]

National cohesiveness

[edit]A study published in 2007 in The Journal of Politics explored questions of whether allowing dual citizenship impedes cultural assimilation or social integration, increases disconnection from the political process, and degrades national or civic identity/cohesiveness.[88]

Stanley Renshon, writing for the anti-immigration think tank Center for immigration studies, cites what he views as a rise in tension between mainstream and migrant communities as evidence of the need to maintain a strong national identity and culture. He asserts that the fact that a second citizenship can be obtained without giving anything up (such as the loss of public benefits, welfare, healthcare, retirement funds, and job opportunities in the country of origin in exchange for citizenship in a new country) both trivializes what it means to be a citizen.[89]

In effect, this approach argues that the self-centered[neutrality is disputed] taking of an additional citizenship contradicts what it means to be a citizen, in that it becomes a convenient[citation needed] and painless means of attaining improved economic opportunity without any real consequences and can just as easily be discarded when it is no longer beneficial.[90] Proponents argue that dual citizenship can actually encourage political activity providing an avenue for immigrants who are unwilling to forsake their country of origin either out of loyalty or based on a feeling of separation from the mainstream society because of language, culture, religion, or ethnicity.[91]

A 2007 academic study concluded that dual citizens had a negative effect on the assimilation and political connectedness of first-generation Latino immigrants to the United States, finding dual citizens:[92]

- 32% less likely to be fluent in English

- 18% less likely to identify as "American"

- 19% less likely to consider the US as their homeland

- 18% less likely to express high levels of civic duty

- 9% less likely to register to vote

- 15% less likely to have ever voted in a national election

The study also noted that although dual nationality is likely to disconnect immigrants from the American political system and impede assimilation, the initial signs suggest that these effects seem to be limited almost exclusively to the first generation (although it is mentioned that a full assessment of dual nationality beyond the first generation is not possible with present data).[92]

Concern over the effect of multiple citizenship on national cohesiveness is generally more acute in the United States. The reason for this is twofold:

- The United States is a "civic" nation and not an "ethnic" nation. American citizenship is not based on belonging to a particular ethnicity but on political loyalty to American democracy and values. Regimes based on ethnicity, which support the doctrine of perpetual allegiance as one is always a member of the ethnic nation, are not concerned with assimilating non-ethnics since they can never become true citizens. In contrast, the essence of a civic nation makes it imperative that immigrants assimilate into the greater whole as there is not an "ethnic" cohesiveness uniting the populace.[93]

- The United States is an immigrant nation. As immigration is primarily directed at family reunification and refugee status rather than education and job skills, the pool of candidates tends to be poorer, less educated,[94] and consistently from less stable countries (either non-democracies or fragile ones) with less familiarity or understanding of American values, making their assimilation both more difficult and more important.[93]

The degree of angst over the effects of dual citizenship seemingly corresponds to a country's model for managing immigration and ethnic diversity:

- The differential exclusionary model, which accepts immigrants as temporary "guestworkers" but is highly restrictive with regard to other forms of immigration and to naturalisation of immigrants. Many countries in Asia such as Japan, China, Taiwan, Singapore and the countries of the Middle East tend to follow this approach.[citation needed]

- The assimilationist model, which accepts that immigrants obtain citizenship, but on the condition that they give up some or all cultural, linguistic, or social characteristics that differ from those of the majority population. Europe is the primary example of this model, where immigrants are usually required to learn the official language, and cultural traditions such as Islamic dress are often barred in public spaces (see Immigration to Europe).[95][96]

- The multicultural model grants immigrants access to citizenship and to equal rights without demanding that they give up cultural, linguistic, or intermarriage restrictions or otherwise pressure them to integrate or inter-mix with the mainstream population. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States have historically taken this approach, as exemplified by the fact that the United States has no official language, allowing official documents such as election ballots to be printed in a variety of languages.[97] (See Immigration to the United States.)

Appearance of foreign allegiance

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2009) |

People with multiple citizenship may be viewed as having dual loyalty, having the potential to act contrary to a government's interests, and this may lead to difficulties in acquiring government employment where security clearance may be required.

In the United States, dual citizenship is associated with two categories of security concerns: foreign influence and foreign preference. Contrary to common misconceptions, dual citizenship in itself is not the major problem in obtaining or retaining security clearance in the United States. As a matter of fact, if a security clearance applicant's dual citizenship is "based solely on parents' citizenship or birth in a foreign country", that can be a mitigating condition.[98] However, taking advantage of the entitlements of a non-US citizenship can cause problems. For example, possession or use of a foreign passport is a condition disqualifying one from security clearance and "is not mitigated by reasons of personal convenience, safety, requirements of foreign law, or the identity of the foreign country" as is explicitly clarified in a Department of Defense policy memorandum which defines a guideline requiring that "any clearance be denied or revoked unless the applicant surrenders the foreign passport or obtains official permission for its use from the appropriate agency of the United States Government".[99]

This guideline has been followed in administrative rulings[100] by the United States Department of Defense (DoD) Defense Office of Hearings and Appeals[101] (DOHA) office of Industrial Security Clearance Review[102] (ISCR), which decides cases involving security clearances for Contractor personnel doing classified work for all DoD components. In one such case, an administrative judge ruled that it is not clearly consistent with US national interest to grant a request for a security clearance to an applicant who was a dual national of the U.S. and Ireland, despite the fact that it has with good relations with the US.[103] In Israel, certain military units, including most recently the Israeli Navy's submarine fleet, as well as posts requiring high security clearances, require candidates to renounce any other citizenship before joining, though the number of units making such demands has declined. In many combat units, candidates are required to declare but not renounce any foreign citizenship.[104]

On the other hand, Israel may view some dual citizens as desirable candidates for its security services because of their ability to legitimately enter neighbouring states which are closed to Israeli passport holders. The related case of Ben Zygier has caused debate about dual citizenship in Australia.[105]

Multiple citizenship among politicians

[edit]This perception of dual loyalty can apply even when the job in question does not require security clearance. In the United States, dual citizenship is common among politicians or government employees. For example, Arnold Schwarzenegger retained his Austrian citizenship during his service as a Governor of California[106] while US Senator Ted Cruz renounced his Canadian citizenship birthright on 14 May 2014.[107][108]

In 1999, the US Attorney General's office issued an official opinion that a statutory provision that required the Justice Department not to employ a non-"citizen of the United States"[109] did not bar it from employing dual citizens.[110]

In Germany, politicians can have dual citizenship. David McAllister, who holds British and German citizenship, was minister president of the State of Lower-Saxony from July 1, 2010, to February 19, 2013. He was the first German minister president to hold dual citizenship.

A small controversy arose in 2005 when Michaëlle Jean was appointed the Governor General of Canada (official representative of the Queen). Although Jean no longer holds citizenship in her native Haiti, her marriage to French-born filmmaker Jean-Daniel Lafond allowed her to obtain French citizenship several years before her appointment. Article 23-8[111] of the French civil code allows the French government to withdraw French nationality from French citizens holding government or military positions in other countries and Jean's appointment made her both de facto head of state and commander-in-chief of the Canadian forces. The French embassy released a statement that this law would not be enforced because the Governor General is essentially a ceremonial figurehead. Nevertheless, Jean renounced her French citizenship two days before taking up office to end the controversy about it.[112]

However, former Canadian Prime Minister John Turner was born in the United Kingdom and still retained his dual citizenship. Stéphane Dion, former head of the Liberal Party of Canada and the previous leader of the official opposition, holds dual citizenship with France as a result of his mother's nationality; Dion nonetheless indicated a willingness to renounce French citizenship if a significant number of Canadians viewed it negatively.[113] Thomas Mulcair, former Leader of the New Democratic Party and former leader of the Official Opposition in the Canadian House of Commons also holds dual citizenship with France.

In Egypt, dual citizens cannot be elected to Parliament.[citation needed]

The Constitution of Australia, in Section 44(i), explicitly forbids people who hold allegiance to foreign powers from sitting in the parliament of Australia.[114] This restriction on people with dual or multiple citizenship being members of parliament does not apply to the state parliaments, and the regulations vary by state. A court case (see Sue v Hill) determined that the UK is a foreign power for purposes of this section of the constitution, despite Australia holding a common nationality with it at the time that the Constitution was written, and that Senator-elect Heather Hill had not been duly elected to the national parliament because at the time of her election she was a subject or citizen of a foreign power. However, the High Court of Australia also ruled that dual citizenship on its own would not be enough to disqualify someone from validly sitting in Parliament. The individual circumstances of the non-Australian citizenship must be looked at although the person must make a reasonable effort to renounce their non-Australian citizenship. However, if that other citizenship cannot be reasonably revoked (for example, if it is impossible under the laws of the other country or impossible in practice because it requires an extremely difficult revocation process), then that person will not be disqualified from sitting in Parliament.[115] In the 2017 Australian parliamentary eligibility crisis, the High Court disqualified Australia's Deputy Prime Minister and four senators because they held dual citizenship, despite being unaware of their citizenship status when elected.

In New Zealand, controversy arose in 2003 when Labour MP Harry Duynhoven applied to renew his citizenship of the Netherlands. Duynhoven, the New Zealand-born son of a Dutch-born father, had possessed dual citizenship from birth but had temporarily lost his Dutch citizenship as a result of a change in Dutch law in 1995 regarding non-residents.[116] While New Zealand's Electoral Act allowed candidates with dual citizenship to be elected as MPs, Section 55[117] of the Act stated that an MP who applied for citizenship of a foreign power after taking office would forfeit his/her seat. This was regarded by many as a technicality, however; and Duynhoven, with his large electoral majority, was almost certain to re-enter Parliament in the event of a by-election. As such, the Labour Government retrospectively amended the Act, thus enabling Duynhoven to retain his seat. The amendment, nicknamed "Harry's Law",[118] was passed by a majority of 61 votes to 56.[119] The revised Act allows exceptions to Section 55 on the grounds of an MP's country/place of birth, descent, or renewing a foreign passport issued before the MP took office.[120]

Both the former Estonian president Toomas Hendrik Ilves and the former Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus had been naturalized US citizens prior to assuming their offices. Both have renounced their US citizenships: Ilves in 1993 and Adamkus in 1998. This was necessary because neither individual's new country permits retention of a former citizenship. Adamkus was a high-ranking official in the Environmental Protection Agency, a federal government department, during his time in the United States. Former Latvian president Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga relinquished Canadian citizenship upon taking office in 1999.[121]

Taxation

[edit]

In some cases, multiple citizenship can create additional tax liability. Almost all countries that impose tax normally base tax liability on source or residency. A very small number of countries tax their non-resident citizens on foreign income; examples include the United States, Eritrea, and the Philippines[122][123]

- Residency: a country may tax the income of anyone who lives there, regardless of citizenship or whether the income was earned in that country or abroad (most common system);

- Source: a country may tax any income generated there, regardless of whether the earner is a citizen, resident, or non-resident; or

- Citizenship: a country may tax the worldwide income of its citizens, regardless of whether they reside in that country or whether the income was sourced there (as of 2012: only the United States and Eritrea).[122] A few other countries tax based on citizenship in limited situations: Finland,[citation needed] France,[citation needed] Hungary,[citation needed] Italy,[citation needed] and Spain.

Under Spanish tax law, Spanish nationals and companies still have tax obligations with Spain if they move to a country that is in the list of tax havens[124] and cannot justify a strong reason, besides tax evasion. They are required to be residents of that country for a minimum of 5 years; after which they are free from any tax obligations.

U.S. persons living outside the United States are still subject to tax on their worldwide income, although U.S. tax law provides measures to reduce or eliminate double taxation issues for some, namely exemption of earned income (up to an inflation-adjusted threshold which, as of 2023, is $120,000[125]), exemption of basic foreign housing,[126] as well as foreign tax credits. It has been reported that some US citizens have relinquished US citizenship in order to avoid possible taxes, the expense and complexity of compliance, or because they have been deemed unacceptable to financial institutions in the wake of FATCA.[127][128][129]

A person with multiple citizenship may have a tax liability to their country of residence and also to one or more of their countries of citizenship; or worse, if unaware that one of their citizenships created a tax liability, that country may consider the person to be a tax evader. Many countries and territories have signed tax treaties or agreements for avoiding double taxation.

Still, there are cases in which a person with multiple citizenship will owe tax solely on the basis of holding one such citizenship. For example, consider a person who holds both Australian and United States citizenship, and lives and works in Australia. They would be subject to Australian taxation, because Australia taxes its residents, and they would be subject to U.S. taxation because they hold U.S. citizenship. In general, they would be allowed to subtract the Australian income tax they paid from the U.S. tax that would be due. In addition, the U.S. will allow some parts of foreign income to be exempt from taxation; for instance, in 2018 the foreign earned income exclusion allowed up to US$103,900 of foreign salaried income to be exempt from income tax (in 2020, this was increased to US$107,600).[125] This exemption, plus the credit for foreign taxes paid mentioned above, often results in no U.S. taxes being owed, although a U.S. tax return would still have to be filed. In instances where the Australian tax was less than the U.S. tax, and where there was income that could not be exempted from U.S. tax, the U.S. would expect any tax due to be paid.

The United States Internal Revenue Service has excluded some regulations such as Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) from tax treaties that protect double taxation. [citation needed] In its current format even if U.S. citizens are paying income taxes at a rate of 56%, far above the maximum U.S. marginal tax rate, the citizen can be subject to US taxes because the calculation of the AMT does not allow full deduction for taxes paid to a foreign country. Other regulations such as the post date of foreign mailed tax returns are not recognized and can result in penalties for late filing if they arrive at the IRS later than the filing date. However, the filing date for overseas citizens has a two-month automatic extension to June 15.[130]

"If you are a U.S. citizen or resident alien residing overseas, or are in the military on duty outside the U.S., on the regular due date of your return, you are allowed an automatic 2-month extension to file your return and pay any amount due without requesting an extension. For a calendar year return, the automatic 2-month extension is to June 15. If you are unable to file your return by the automatic 2-month extension date, you can request an additional extension to October 15 by filing Form 4868 before the automatic 2-month extension date. However, any tax due payments made after June 15 will be subject to both interest charges and failure to pay penalties." (IRS, 2012)[citation needed]

Issues with international travel

[edit]Many countries, even those that permit multiple citizenship, do not explicitly recognise multiple citizenship under their laws: individuals are treated either as citizens of that country or not, and their citizenship with respect to other countries is considered to have no bearing. This can mean (in Iran,[131] Mexico,[132] many Arab countries, and former Soviet republics) that consular officials abroad may not have access to their citizens if they also hold local citizenship. Some countries provide access for consular officials as a matter of courtesy but do not accept any obligation to do so under international consular agreements. The right of countries to act in this fashion is protected via the Master Nationality Rule.[citation needed]

Multiple citizens who travel to a country of citizenship are often required to enter or leave the country on that country's passport. For example, a United States Department of State web page on dual nationality contains the information that most US citizens, including dual nationals, must use a US passport to enter and leave the United States.[133] Under the terms of the South African Citizenship Act, it is an offence for someone aged at least 18 with South African citizenship and another citizenship to enter or depart the Republic of South Africa using the passport of another country.[134] Individuals who possess multiple citizenships, may also be required, before leaving a country of citizenship, to fulfill requirements ordinarily required of its resident citizens, including compulsory military service or exit permits. An example of this occurs in Israel, which permits multiple citizenships whilst also requiring compulsory military service for its citizens.

In accordance with the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS), the EU citizens who have multiple nationalities will be obliged to use the passport issued by an EU Member State for entering the Schengen area.[135]

Military service

[edit]

Military service for dual nationals can be an issue of concern. Several countries have entered into a Protocol relating to Military Obligations in Certain Cases of Double Nationality established at The Hague, 12 April 1930. The protocol states "A person possessing two or more nationalities who habitually resides in one of the countries whose nationality he possesses, and who is in fact most closely connected with that country, shall be exempt from all military obligations in the other country or countries. This exemption may involve the loss of the nationality of the other country or countries." The protocol has several provisions.[136]

Healthcare

[edit]The right to healthcare in countries with a public health service is often discussed in relation to immigration but is a non-issue as far as nationality is concerned. The right to use public health services may be conditioned on nationality and/or on legal residency. For example, anyone legally resident and employed in the UK is entitled to use the National Health Service; non-resident British citizens visiting Britain do not have this right unless they are UK state pensioners who hold a UK S1 form.[citation needed]

By region

[edit]Africa

[edit]Dual citizenship is allowed in Angola, Burundi, Comoros, Cabo Verde, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe; others restrict or forbid dual citizenship. Lesotho observes dual citizenship,[citation needed] as well as jus soli. There are problems regarding dual citizenship in Namibia.[137] Eritreans,[citation needed] Egyptians,[citation needed] and South Africans[31] wanting to take another citizenship need permission to maintain their citizenship, though multiple citizenship acquired from birth is not affected. Eritrea taxes its citizens worldwide, even if they have never lived in the country.[138] Equatorial Guinea does not allow dual citizenship, but it is allowed for children born abroad, if at least one parent is a citizen of Equatorial Guinea.[139] Tanzania and Cameroon do not allow dual citizenship.[140]

The Americas

[edit]Most countries in the Americas allow dual citizenship, some only for citizens by descent or with other countries, usually also in the region with which they have agreements. Some countries (e.g., Argentina, Bolivia) do not allow their citizens to renounce their citizenship, so their nationals retain it even when naturalizing in a country that forbids dual citizenship. Most countries in the region observe unconditional jus soli, i.e. a child born there is regarded as a citizen even if the parents are not. Some countries, such as the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Uruguay, allow renunciation of citizenship only if it was involuntarily acquired by birth to non-citizen parents.

Dual citizenship is restricted or forbidden in Cuba, Suriname, Panama,[141] and Guyana.

- Colombia's Constitution gives every Colombian the right to have more than one nationality.[142] It does not, however, grant automatic birthright citizenship.[143] To obtain Colombian nationality at birth, a person must have at least one parent who is a national or legal resident of Colombia. A child born outside Colombia who has at least one Colombian parent can be registered as a Colombian national by birth, either upon returning to Colombia (for residents) or at a consulate abroad (for non-residents).[143]

- Venezuela allows dual nationality as stated in Article 34 of the Constitution of Venezuela.[144] The only requirement for citizens with dual nationality to enter Venezuelan territory is to present documents proving their Venezuelan nationality (even if they have expired).[145] Venezuelans who possess dual citizenship have the same rights and duties as Venezuelans who do not possess dual citizenship.

- United States law does not mention dual nationality or require a person to choose one nationality or another. A U.S. citizen may naturalize in a foreign state without any risk to their U.S. citizenship.[146] The United States also permits the formal renunciation of U.S. citizenship.[147]

Asia and Oceania

[edit]Most countries in Asia restrict or forbid dual citizenship.[citation needed] In some of these countries (e.g. Iran, North Korea, Kuwait), it is very difficult or even impossible for citizens to renounce their citizenship, even if a citizen is naturalized in another country.[citation needed]

- Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Philippines, South Korea, Tonga, Vanuatu, and Vietnam allow dual citizenship.[148][149][150] Australia's constitution does not permit dual nationals to be elected to the federal Parliament. The issue of multiple citizenship caused a parliamentary eligibility crisis.

- Cambodia allows dual citizenship and observes jus soli for children born to legal permanent residents born in Cambodia or to children whose parents are unknown. In 2021 Cambodia banned dual citizenship for prime minister, presidents of the National Assembly, Senate and the Constitutional Council.[151][152]

- Hong Kong and Macau allow dual citizenship for citizens by birth but do not permit applicants for naturalization to retain their prior citizenship. However, there is no such thing as Hong Kong and Macau citizenship. The nationality law of the People's Republic of China (CNL) has been applied in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Macau Special Administrative Region since 1 July 1997 and 20 December 1999 respectively. Hong Kong and Macau residents who are Chinese citizens holding foreign passports must make a declaration of change of nationality to the HKSAR Immigration Department or MSAR Identification Services Bureau in order to be regarded as foreign nationals. Foreign nationals or stateless persons can apply for naturalisation as a Chinese national provided that they are Hong Kong or Macau residents and meet the requirements under CNL.[153][154]

- South Korea allows dual citizenship for certain groups of overseas Koreans who acquired foreign citizenship at birth. In general, Korean nationals born with other foreign nationality must declare an intention to renounce foreign nationality or refrain from exercising foreign nationality while in the Republic of Korea, or risk losing Korean nationality at age 22 for women, and age 18 for men. Foreign nationals who naturalize must renounce former nationality as precondition.

- Taiwan[155] allows dual citizenship for citizens by birth or for its own citizens but do not permit foreign applicants for naturalization to retain their prior citizenship unless they are senior professionals or have made outstanding contributions to Taiwan. This restriction does not apply to Hong Kong and Macau residents who do not possess a foreign nationality. Naturalised citizens may apply for resumption of their original citizenship following renunciation and granting of Republic of China (Taiwan) citizenship.[a]