Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Project management

View on Wikipedia

| Business administration |

|---|

Project management is the process of supervising the work of a team to achieve all project goals within the given constraints.[1] This information is usually described in project documentation, created at the beginning of the development process. The primary constraints are scope, time and budget.[2] The secondary challenge is to optimize the allocation of necessary inputs and apply them to meet predefined objectives.

The objective of project management is to produce a complete project which complies with the client's objectives. In many cases, the objective of project management is also to shape or reform the client's brief to feasibly address the client's objectives. Once the client's objectives are established, they should influence all decisions made by other people involved in the project– for example, project managers, designers, contractors and subcontractors. Ill-defined or too tightly prescribed project management objectives are detrimental to the decisionmaking process.

A project is a temporary and unique endeavor designed to produce a product, service or result with a defined beginning and end (usually time-constrained, often constrained by funding or staffing) undertaken to meet unique goals and objectives, typically to bring about beneficial change or added value.[3][4] The temporary nature of projects stands in contrast with business as usual (or operations),[5] which are repetitive, permanent or semi-permanent functional activities to produce products or services. In practice, the management of such distinct production approaches requires the development of distinct technical skills and management strategies.[6]

History

[edit]Prior to the year 1900, civil engineering projects were generally managed by creative architects, engineers, and master builders themselves, for example, Vitruvius (first century BC), Christopher Wren (1632–1723), Thomas Telford (1757–1834), and Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859).[7] In the 1950s, organizations started to apply project-management tools and techniques more systematically to complex engineering projects.[8]

As a discipline, project management developed from several fields of application including civil construction, engineering, and heavy defense activity.[9] Two forefathers of project management are Henry Gantt, called the father of planning and control techniques,[10] who is famous for his use of the Gantt chart as a project management tool (alternatively Harmonogram first proposed by Karol Adamiecki);[11] and Henri Fayol for his creation of the five management functions that form the foundation of the body of knowledge associated with project and program management.[12] Both Gantt and Fayol were students of Frederick Winslow Taylor's theories of scientific management. His work is the forerunner to modern project management tools including work breakdown structure (WBS) and resource allocation.

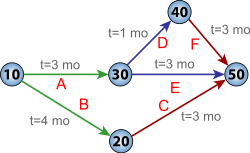

The 1950s marked the beginning of the modern project management era, where core engineering fields came together to work as one. Project management became recognized as a distinct discipline arising from the management discipline with the engineering model.[13] In the United States, prior to the 1950s, projects were managed on an ad-hoc basis, using mostly Gantt charts and informal techniques and tools. At that time, two mathematical project-scheduling models were developed. The critical path method (CPM) was developed as a joint venture between DuPont Corporation and Remington Rand Corporation for managing plant maintenance projects. The program evaluation and review technique (PERT), was developed by the U.S. Navy Special Projects Office in conjunction with the Lockheed Corporation and Booz Allen Hamilton as part of the Polaris missile submarine program.[14]

PERT and CPM are very similar in their approach but still present some differences. CPM is used for projects that assume deterministic activity times; the times at which each activity will be carried out are known. PERT, on the other hand, allows for stochastic activity times; the times at which each activity will be carried out are uncertain or varied. Because of this core difference, CPM and PERT are used in different contexts. These mathematical techniques quickly spread into many private enterprises.

At the same time, as project-scheduling models were being developed, technology for project cost estimating, cost management and engineering economics was evolving, with pioneering work by Hans Lang and others. In 1956, the American Association of Cost Engineers (now AACE International; the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering) was formed by early practitioners of project management and the associated specialties of planning and scheduling, cost estimating, and project control. AACE continued its pioneering work and in 2006, released the first integrated process for portfolio, program, and project management (total cost management framework).

In 1969, the Project Management Institute (PMI) was formed in the USA.[15] PMI publishes the original version of A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) in 1996 with William Duncan as its primary author, which describes project management practices that are common to "most projects, most of the time."[16]

In August 2021,the Project Management Institute (PMI) released the seventh edition of A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), marking a significant evolution in project management standards. Unlike previous editions, which emphasized a process-based framework, the seventh edition adopts a holistic, principle-based approach, aligning with the dynamic needs of modern project management. This shift integrates agile, hybrid, and predictive methodologies, reflecting the growing diversity of project delivery methods across industries.

A key feature of the seventh edition is the introduction of eight performance domains: Stakeholder, Team, Development Approach and Life Cycle, Planning, Project Work, Delivery, Measurement, and Uncertainty. These domains provide a comprehensive framework for effective project management, focusing on outcomes and adaptability rather than rigid processes. By emphasizing principles over prescriptive steps, the guide encourages practitioners to tailor practices to specific project contexts, enhancing flexibility and innovation. This transformative update, accompanied by The Standard for Project Management, underscores PMI’s commitment to addressing contemporary challenges and fostering value-driven project outcomes.

This shift in focus brings project management practitioners into the 21st century, opening up the door to a more holistic and people-centric approach.

Project management types

[edit]Project management methods can be applied to any project. It is often tailored to a specific type of project based on project size, nature, industry or sector. For example, the construction industry, which focuses on the delivery of things like buildings, roads, and bridges, has developed its own specialized form of project management that it refers to as construction project management and in which project managers can become trained and certified.[17] The information technology industry has also evolved to develop its own form of project management that is referred to as IT project management and which specializes in the delivery of technical assets and services that are required to pass through various lifecycle phases such as planning, design, development, testing, and deployment. Biotechnology project management focuses on the intricacies of biotechnology research and development.[18] Localization project management includes application of many standard project management practices to translation works even though many consider this type of management to be a very different discipline. For example, project managers have a key role in improving the translation even when they do not speak the language of the translation, because they know the study objectives well to make informed decisions.[19] Similarly, research study management can also apply a project manage approach.[20] There is public project management that covers all public works by the government, which can be carried out by the government agencies or contracted out to contractors. Another classification of project management is based on the hard (physical) or soft (non-physical) type.

Common among all the project management types is that they focus on three important goals: time, quality, and cost. Successful projects are completed on schedule, within budget, and according to previously agreed quality standards i.e. meeting the Iron Triangle or Triple Constraint in order for projects to be considered a success or failure.[21]

For each type of project management, project managers develop and utilize repeatable templates that are specific to the industry they're dealing with. This allows project plans to become very thorough and highly repeatable, with the specific intent to increase quality, lower delivery costs, and lower time to deliver project results.

Approaches of project management

[edit]A 2017 study suggested that the success of any project depends on how well four key aspects are aligned with the contextual dynamics affecting the project, these are referred to as the four P's:[22]

- Plan: The planning and forecasting activities.

- Process: The overall approach to all activities and project governance.

- People: Including dynamics of how they collaborate and communicate.

- Power: Lines of authority, decision-makers, organograms, policies for implementation and the like.

There are a number of approaches to organizing and completing project activities, including phased, lean, iterative, and incremental. There are also several extensions to project planning, for example, based on outcomes (product-based) or activities (process-based).

Regardless of the methodology employed, careful consideration must be given to the overall project objectives, timeline, and cost, as well as the roles and responsibilities of all participants and stakeholders.[23]

Benefits realization management

[edit]Benefits realization management (BRM) enhances normal project management techniques through a focus on outcomes (benefits) of a project rather than products or outputs and then measuring the degree to which that is happening to keep a project on track. This can help to reduce the risk of a completed project being a failure by delivering agreed upon requirements (outputs) i.e. project success but failing to deliver the benefits (outcomes) of those requirements i.e. product success. Note that good requirements management will ensure these benefits are captured as requirements of the project and their achievement monitored throughout the project.

In addition, BRM practices aim to ensure the strategic alignment between project outcomes and business strategies. The effectiveness of these practices is supported by recent research evidencing BRM practices influencing project success from a strategic perspective across different countries and industries. These wider effects are called the strategic impact.[24]

An example of delivering a project to requirements might be agreeing to deliver a computer system that will process staff data and manage payroll, holiday, and staff personnel records in shorter times with reduced errors. Under BRM, the agreement might be to achieve a specified reduction in staff hours and errors required to process and maintain staff data after the system installation when compared without the system.

Critical path method

[edit]Critical path method (CPM) is an algorithm for determining the schedule for project activities. It is the traditional process used for predictive-based project planning. The CPM method evaluates the sequence of activities, the work effort required, the inter-dependencies, and the resulting float time per line sequence to determine the required project duration. Thus, by definition, the critical path is the pathway of tasks on the network diagram that has no extra time available (or very little extra time)."[25]

Critical chain project management

[edit]Critical chain project management (CCPM) is an application of the theory of constraints (TOC) to planning and managing projects and is designed to deal with the uncertainties inherent in managing projects, while taking into consideration the limited availability of resources (physical, human skills, as well as management & support capacity) needed to execute projects.

The goal is to increase the flow of projects in an organization (throughput). Applying the first three of the five focusing steps of TOC, the system constraint for all projects, as well as the resources, are identified. To exploit the constraint, tasks on the critical chain are given priority over all other activities.

Earned value management

[edit]Earned value management (EVM) extends project management with techniques to improve project monitoring.[26] It illustrates project progress towards completion in terms of work and value (cost). Earned Schedule is an extension to the theory and practice of EVM.

Iterative and incremental project management

[edit]In critical studies of project management, it has been noted that phased approaches are not well suited for projects which are large-scale and multi-company,[27] with undefined, ambiguous, or fast-changing requirements,[28] or those with high degrees of risk, dependency, and fast-changing technologies. The cone of uncertainty explains some of this as the planning made on the initial phase of the project suffers from a high degree of uncertainty. This becomes especially true as software development is often the realization of a new or novel product.

These complexities are better handled with a more exploratory or iterative and incremental approach.[29] Several models of iterative and incremental project management have evolved, including agile project management, dynamic systems development method, and extreme project management.

Lean project management

[edit]Lean project management uses the principles from lean manufacturing to focus on delivering value with less waste and reduced time.

Project lifecycle

[edit]There are five phases to a project lifecycle; known as process groups. Each process group represents a series of inter-related processes to manage the work through a series of distinct steps to be completed. This type of project approach is often referred to as "traditional"[30] or "waterfall".[31] The five process groups are:

- Initiating

- Planning

- Executing

- Monitoring and Controlling

- Closing

Some industries may use variations of these project stages and rename them to better suit the organization. For example, when working on a brick-and-mortar design and construction, projects will typically progress through stages like pre-planning, conceptual design, schematic design, design development, construction drawings (or contract documents), and construction administration.

While the phased approach works well for small, well-defined projects, it often results in challenge or failure on larger projects, or those that are more complex or have more ambiguities, issues, and risks[32] - see the parodying 'six phases of a big project'.

Process-based management

[edit]The incorporation of process-based management has been driven by the use of maturity models such as the OPM3 and the CMMI (capability maturity model integration; see Image:Capability Maturity Model.jpg

Project production management

[edit]Project production management is the application of operations management to the delivery of capital projects. The Project production management framework is based on a project as a production system view, in which a project transforms inputs (raw materials, information, labor, plant & machinery) into outputs (goods and services).[33]

Product-based planning

[edit]Product-based planning is a structured approach to project management, based on identifying all of the products (project deliverables) that contribute to achieving the project objectives. As such, it defines a successful project as output-oriented rather than activity- or task-oriented.[34] The most common implementation of this approach is PRINCE2.[35]

Process groups

[edit]

Traditionally (depending on what project management methodology is being used), project management includes a number of elements: four to five project management process groups, and a control system. Regardless of the methodology or terminology used, the same basic project management processes or stages of development will be used. Major process groups generally include:[37]

- Initiation

- Planning

- Production or execution

- Monitoring and controlling

- Closing

In project environments with a significant exploratory element (e.g., research and development), these stages may be supplemented with decision points (go/no go decisions) at which the project's continuation is debated and decided. An example is the Phase–gate model.

Project management relies on a wide variety of meetings to coordinate actions. For instance, there is the kick-off meeting, which broadly involves stakeholders at the project's initiation. Project meetings or project committees enable the project team to define and monitor action plans. Steering committees are used to transition between phases and resolve issues. Project portfolio and program reviews are conducted in organizations running parallel projects. Lessons learned meetings are held to consolidate learnings. All these meetings employ techniques found in meeting science, particularly to define the objective, participant list, and facilitation methods.

Initiating

[edit]

The initiating processes determine the nature and scope of the project.[38] If this stage is not performed well, it is unlikely that the project will be successful in meeting the business' needs. The key project controls needed here are an understanding of the business environment and making sure that all necessary controls are incorporated into the project. Any deficiencies should be reported and a recommendation should be made to fix them.

The initiating stage should include a plan that encompasses the following areas. These areas can be recorded in a series of documents called Project Initiation documents. Project Initiation documents are a series of planned documents used to create an order for the duration of the project. These tend to include:

- project proposal (idea behind project, overall goal, duration)

- project scope (project direction and track)

- product breakdown structure (PBS) (a hierarchy of deliverables/outcomes and components thereof)

- work breakdown structure (WBS) (a hierarchy of the work to be done, down to daily tasks)

- responsibility assignment matrix (RACI - Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) (roles and responsibilities aligned to deliverables / outcomes)

- tentative project schedule (milestones, important dates, deadlines)

- analysis of business needs and requirements against measurable goals

- review of the current operations

- financial analysis of the costs and benefits, including a budget

- stakeholder analysis, including users and support personnel for the project

- project charter including costs, tasks, deliverables, and schedules

- SWOT analysis: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to the business

Planning

[edit]After the initiation stage, the project is planned to an appropriate level of detail (see an example of a flowchart).[36] The main purpose is to plan time, cost, and resources adequately to estimate the work needed and to effectively manage risk during project execution. As with the Initiation process group, a failure to adequately plan greatly reduces the project's chances of successfully accomplishing its goals.

Project planning generally consists of[39]

- determining the project management methodology to follow (e.g. whether the plan will be defined wholly upfront, iteratively, or in rolling waves);

- developing the scope statement;

- selecting the planning team;

- identifying deliverables and creating the product and work breakdown structures;

- identifying the activities needed to complete those deliverables and networking the activities in their logical sequence;

- estimating the resource requirements for the activities;

- estimating time and cost for activities;

- developing the schedule;

- developing the budget;

- risk planning;

- developing quality assurance measures;

- gaining formal approval to begin work.

Additional processes, such as planning for communications and for scope management, identifying roles and responsibilities, determining what to purchase for the project, and holding a kick-off meeting are also generally advisable.

For new product development projects, conceptual design of the operation of the final product may be performed concurrent with the project planning activities and may help to inform the planning team when identifying deliverables and planning activities.

Executing

[edit]

While executing we must know what are the planned terms that need to be executed. The execution/implementation phase ensures that the project management plan's deliverables are executed accordingly. This phase involves proper allocation, coordination, and management of human resources and any other resources such as materials and budgets. The output of this phase is the project deliverables.

Project documentation

[edit]Documenting everything within a project is key to being successful. To maintain budget, scope, effectiveness and pace a project must have physical documents pertaining to each specific task. With correct documentation, it is easy to see whether or not a project's requirement has been met. To go along with that, documentation provides information regarding what has already been completed for that project. Documentation throughout a project provides a paper trail for anyone who needs to go back and reference the work in the past. In most cases, documentation is the most successful way to monitor and control the specific phases of a project. With the correct documentation, a project's success can be tracked and observed as the project goes on. If performed correctly, documentation can be the backbone of a project's success

Monitoring and controlling

[edit]

Monitoring and controlling consist of those processes performed to observe project execution so that potential problems can be identified in a timely manner and corrective action can be taken, when necessary, to control the execution of the project. The key benefit is that project performance is observed and measured regularly to identify variances from the project management plan.

Monitoring and controlling include:[40]

- Measuring the ongoing project activities ('where we are');

- Monitoring the project variables (cost, effort, scope, etc.) against the project management plan and the project performance baseline (where we should be);

- Identifying corrective actions to address issues and risks properly (How can we get on track again);

- Influencing the factors that could circumvent integrated change control so only approved changes are implemented.

Two main mechanisms support monitoring and controlling in projects. On the one hand, contracts offer a set of rules and incentives often supported by potential penalties and sanctions.[41] On the other hand, scholars in business and management have paid attention to the role of integrators (also called project barons) to achieve a project's objectives.[42][43] In turn, recent research in project management has questioned the type of interplay between contracts and integrators. Some have argued that these two monitoring mechanisms operate as substitutes[44] as one type of organization would decrease the advantages of using the other one.

In multi-phase projects, the monitoring and control process also provides feedback between project phases, to implement corrective or preventive actions to bring the project into compliance with the project management plan.

Project maintenance is an ongoing process, and it includes:[37]

- Continuing support of end-users

- Correction of errors

- Updates to the product over time

In this stage, auditors should pay attention to how effectively and quickly user problems are resolved.

Over the course of any construction project, the work scope may change. Change is a normal and expected part of the construction process. Changes can be the result of necessary design modifications, differing site conditions, material availability, contractor-requested changes, value engineering, and impacts from third parties, to name a few. Beyond executing the change in the field, the change normally needs to be documented to show what was actually constructed. This is referred to as change management. Hence, the owner usually requires a final record to show all changes or, more specifically, any change that modifies the tangible portions of the finished work. The record is made on the contract documents – usually, but not necessarily limited to, the design drawings. The end product of this effort is what the industry terms as-built drawings, or more simply, "as built." The requirement for providing them is a norm in construction contracts. Construction document management is a highly important task undertaken with the aid of an online or desktop software system or maintained through physical documentation. The increasing legality pertaining to the construction industry's maintenance of correct documentation has caused an increase in the need for document management systems.

When changes are introduced to the project, the viability of the project has to be re-assessed. It is important not to lose sight of the initial goals and targets of the projects. When the changes accumulate, the forecasted result may not justify the original proposed investment in the project. Successful project management identifies these components, and tracks and monitors progress, so as to stay within time and budget frames already outlined at the commencement of the project. Exact methods were suggested to identify the most informative monitoring points along the project life-cycle regarding its progress and expected duration.[45]

Closing

[edit]

Closing includes the formal acceptance of the project and the ending thereof. Administrative activities include the archiving of the files and documenting lessons learned.

This phase consists of:[37]

- Contract closure: Complete and settle each contract (including the resolution of any open items) and close each contract applicable to the project or project phase.

- Project close: Finalize all activities across all of the process groups to formally close the project or a project phase

Also included in this phase is the post implementation review. This is a vital phase of the project for the project team to learn from experiences and apply to future projects. Normally a post implementation review consists of looking at things that went well and analyzing things that went badly on the project to come up with lessons learned.

Project control and project control systems

[edit]Project control (also known as Cost Engineering) should be established as an independent function in project management. It implements verification and controlling functions during the processing of a project to reinforce the defined performance and formal goals.[46] The tasks of project control are also:

- the creation of infrastructure for the supply of the right information and its update

- the establishment of a way to communicate disparities in project parameters

- the development of project information technology based on an intranet or the determination of a project key performance indicator system (KPI)

- divergence analyses and generation of proposals for potential project regulations[47]

- the establishment of methods to accomplish an appropriate project structure, project workflow organization, project control, and governance

- creation of transparency among the project parameters[48]

Fulfillment and implementation of these tasks can be achieved by applying specific methods and instruments of project control. The following methods of project control can be applied:

- investment analysis

- cost–benefit analysis

- value benefit analysis

- expert surveys

- simulation calculations

- risk-profile analysis

- surcharge calculations

- milestone trend analysis

- cost trend analysis

- target/actual comparison[49]

Project control is that element of a project that keeps it on track, on time, and within budget.[40] Project control begins early in the project with planning and ends late in the project with post-implementation review, having a thorough involvement of each step in the process. Projects may be audited or reviewed while the project is in progress. Formal audits are generally risk or compliance-based and management will direct the objectives of the audit. An examination may include a comparison of approved project management processes with how the project is actually being managed.[50] Each project should be assessed for the appropriate level of control needed: too much control is too time-consuming, too little control is very risky. If project control is not implemented correctly, the cost to the business should be clarified in terms of errors and fixes.

Control systems are needed for cost, risk, quality, communication, time, change, procurement, and human resources. In addition, auditors should consider how important the projects are to the financial statements, how reliant the stakeholders are on controls, and how many controls exist. Auditors should review the development process and procedures for how they are implemented. The process of development and the quality of the final product may also be assessed if needed or requested. A business may want the auditing firm to be involved throughout the process to catch problems earlier on so that they can be fixed more easily. An auditor can serve as a controls consultant as part of the development team or as an independent auditor as part of an audit.

Businesses sometimes use formal systems development processes. This help assure systems are developed successfully. A formal process is more effective in creating strong controls, and auditors should review this process to confirm that it is well designed and is followed in practice. A good formal systems development plan outlines:

Characteristics of projects

[edit]There are five important characteristics of a project:

(i) It should always have specific start and end dates.

(ii) They are performed and completed by a group of people.

(iii) The output is the delivery of a unique product or service.

(iv) They are temporary in nature.

(v) It is progressively elaborated.

Examples are: designing a new car or writing a book.

Project complexity

[edit]Complexity and its nature play an important role in the area of project management. Despite having a number of debates on this subject matter, studies suggest a lack of definition and reasonable understanding of complexity in relation to the management of complex projects.[51][52]

Project complexity is the property of a project which makes it difficult to understand, foresee, and keep under control its overall behavior, even when given reasonably complete information about the project system.[53]

The identification of complex projects is specifically important to multi-project engineering environments.[54]

As it is considered that project complexity and project performance are closely related, it is important to define and measure the complexity of the project for project management to be effective.[55]

Complexity can be:

- Structural complexity (also known as detail complexity, or complicatedness), i.e. consisting of many varied interrelated parts.[56] It is typically expressed in terms of size, variety, and interdependence of project components, and described by technological and organizational factors.

- Dynamic complexity refers to phenomena, characteristics, and manifestations such as ambiguity, uncertainty, propagation, emergence, and chaos.[53]

Based on the Cynefin framework,[57] complex projects can be classified as:

- Simple (or clear, obvious, known) projects, systems, or contexts. These are characterized by known knowns, stability, and clear cause-and-effect relationships. They can be solved with standard operating procedures and best practices.

- Complicated: characterized by known unknowns. A complicated system is the sum of its parts. In principle, it can be deconstructed into smaller simpler components. While difficult, complicated problems are theoretically solvable with additional resources, specialized expertise, analytical, reductionist, simplification, decomposition techniques, scenario planning, and following good practices.[58][59]

- Complex are characterized by unknown unknowns, and emergence. Patterns could be uncovered, but they are not obvious. A complex system can be described by Euclid's statement that the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

- Really complex projects, a.k.a. very complex, or chaotic: characterized by unknowables. No patterns are discernible in really complex projects. Causes and effects are unclear even in retrospect. Paraphrasing Aristotle, a really complex system is different from the sum of its parts.[60]

By applying the discovery in measuring work complexity described in Requisite Organization and Stratified Systems Theory, Elliott Jaques classifies projects and project work (stages, tasks) into seven basic levels of project complexity based on such criteria as time-span of discretion and complexity of a project's output:[61][62]

- Level 1 Project – improve the direct output of an activity (quantity, quality, time) within a business process with a targeted completion time up to 3 months.

- Level 2 Project – develop and improve compliance to a business process with a targeted completion time of 3 months to 1 year.

- Level 3 Project – develop, change, and improve a business process with a targeted completion time of 1 to 2 years.

- Level 4 Project – develop, change, and improve a functional system with a targeted completion time of 2 to 5 years.

- Level 5 Project – develop, change, and improve a group of functional systems/business functions with a targeted completion time of 5 to 10 years.

- Level 6 Project – develop, change, and improve a whole single value chain of a company with targeted completion time from 10 to 20 years.

- Level 7 Project – develop, change, and improve multiple value chains of a company with target completion time from 20 to 50 years.[63]

Benefits from measuring Project Complexity are to improve project people feasibility by matching the level of a project's complexity with an effective targeted completion time, with the respective capability level of the project manager and of the project members.[64]

Positive, appropriate (requisite), and negative complexity

[edit]

Similarly with the Law of requisite variety and The law of requisite complexity, project complexity is sometimes required in order for the project to reach its objectives, and sometimes it has beneficial outcomes. Based on the effects of complexity, Stefan Morcov proposed its classification as Positive, Appropriate, or Negative.[65][60]

- Positive complexity is the complexity that adds value to the project, and whose contribution to project success outweighs the associated negative consequences.

- Appropriate (or requisite) complexity is the complexity that is needed for the project to reach its objectives, or whose contribution to project success balances the negative effects, or the cost of mitigation outweighs negative manifestations.

- Negative complexity is the complexity that hinders project success.

Project managers

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

A project manager is a professional in the field of project management. Project managers are in charge of the people in a project. People are the key to any successful project. Without the correct people in the right place and at the right time a project cannot be successful. Project managers can have the responsibility of the planning, execution, controlling, and closing of any project typically relating to the construction industry, engineering, architecture, computing, and telecommunications. Many other fields of production engineering, design engineering, and heavy industrial have project managers.

A project manager needs to understand the order of execution of a project to schedule the project correctly as well as the time necessary to accomplish each individual task within the project. A project manager is the person accountable for accomplishing the stated project objectives on behalf of the client. Project Managers tend to have multiple years' experience in their field. A project manager is required to know the project in and out while supervising the workers along with the project. Typically in most construction, engineering, architecture, and industrial projects, a project manager has another manager working alongside of them who is typically responsible for the execution of task on a daily basis. This position in some cases is known as a superintendent. A superintendent and project manager work hand in hand in completing daily project tasks. Key project management responsibilities include creating clear and attainable project objectives, building the project requirements, and managing the triple constraint (now including more constraints and calling it competing constraints) for projects, which is cost, time, quality and scope for the first three but about three additional ones in current project management. A typical project is composed of a team of workers who work under the project manager to complete the assignment within the time and budget targets. A project manager normally reports directly to someone of higher stature on the completion and success of the project.

A project manager is often a client representative and has to determine and implement the exact needs of the client, based on knowledge of the firm they are representing. The ability to adapt to the various internal procedures of the contracting party, and to form close links with the nominated representatives, is essential in ensuring that the key issues of cost, time, quality and above all, client satisfaction, can be realized.

A complete project manager, a term first coined by Robert J. Graham in his simulation, has been expanded upon by Randall L. Englund and Alfonso Bucero. They describe a complete project manager as a person who embraces multiple disciplines, such as leadership, influence, negotiations, politics, change and conflict management, and humor. These are all "soft" people skills that enable project leaders to be more effective and achieve optimized, consistent results.

Multilevel success framework and criteria - project success vs. project performance

[edit]There is a tendency to confuse the project success with project management success. They are two different things. "Project success" has 2 perspectives:

- the perspective of the process, i.e. delivering efficient outputs; typically called project management performance or project efficiency.

- the perspective of the result, i.e. delivering beneficial outcomes; typically called project performance (sometimes just project success).[66][67][68][self-published source?]

Project management success criteria are different from project success criteria. The project management is said to be successful if the given project is completed within the agreed upon time, met the agreed upon scope and within the agreed upon budget. Subsequent to the triple constraints, multiple constraints have been considered to ensure project success. However, the triple or multiple constraints indicate only the efficiency measures of the project, which are indeed the project management success criteria during the project lifecycle.

The priori criteria leave out the more important after-completion results of the project which comprise four levels i.e. the output (product) success, outcome (benefits) success and impact (strategic) success during the product lifecycle. These posterior success criteria indicate the effectiveness measures of the project product, service or result, after the project completion and handover. This overarching multilevel success framework of projects, programs and portfolios has been developed by Paul Bannerman in 2008.[69] In other words, a project is said to be successful, when it succeeds in achieving the expected business case which needs to be clearly identified and defined during the project inception and selection before starting the development phase. This multilevel success framework conforms to the theory of project as a transformation depicted as the input-process / activity-output-outcome-impact in order to generate whatever value intended. Emanuel Camilleri in 2011 classifies all the critical success and failure factors into groups and matches each of them with the multilevel success criteria in order to deliver business value.[70]

An example of a performance indicator used in relation to project management is the "backlog of commissioned projects" or "project backlog".[71]

Risk management

[edit]The United States Department of Defense states that "Cost, Schedule, Performance, and Risk" are the four elements through which Department of Defense acquisition professionals make trade-offs and track program status.[72] There are also international standards. Risk management applies proactive identification (see tools) of future problems and understanding of their consequences allowing predictive decisions about projects. ERM system plays a role in overall risk management.[73]

Work breakdown structure and other breakdown structures

[edit]The work breakdown structure (WBS) is a tree structure that shows a subdivision of the activities required to achieve an objective – for example a portfolio, program, project, and contract. The WBS may be hardware-, product-, service-, or process-oriented (see an example in a NASA reporting structure (2001)).[74] Beside WBS for project scope management, there are organizational breakdown structure (chart), cost breakdown structure and risk breakdown structure.

A WBS can be developed by starting with the end objective and successively subdividing it into manageable components in terms of size, duration, and responsibility (e.g., systems, subsystems, components, tasks, sub-tasks, and work packages), which include all steps necessary to achieve the objective.[32]

The work breakdown structure provides a common framework for the natural development of the overall planning and control of a contract and is the basis for dividing work into definable increments from which the statement of work can be developed and technical, schedule, cost, and labor hour reporting can be established.[74] The work breakdown structure can be displayed in two forms, as a table with subdivision of tasks or as an organizational chart whose lowest nodes are referred to as "work packages".

It is an essential element in assessing the quality of a plan, and an initial element used during the planning of the project. For example, a WBS is used when the project is scheduled, so that the use of work packages can be recorded and tracked.

Similarly to work breakdown structure (WBS), other decomposition techniques and tools are: organization breakdown structure (OBS), product breakdown structure (PBS), cost breakdown structure (CBS), risk breakdown structure (RBS), and resource breakdown structure (ResBS).[75][60]

International standards

[edit]There are several project management standards, including:

- The ISO standards ISO 9000, a family of standards for quality management systems, and the ISO 10006:2003, for Quality management systems and guidelines for quality management in projects.

- ISO 21500:2012 – Guidance on project management. This is the first International Standard related to project management published by ISO. Other standards in the 21500 family include 21503:2017 Guidance on programme management; 21504:2015 Guidance on portfolio management; 21505:2017 Guidance on governance; 21506:2018 Vocabulary; 21508:2018 Earned value management in project and programme management; and 21511:2018 Work breakdown structures for project and programme management.

- ISO 21502:2020 Project, programme and portfolio management — Guidance on project management

- ISO 21503:2022 Project, programme and portfolio management — Guidance on programme management

- ISO 21504:2015 Project, programme and portfolio management – Guidance on portfolio management

- ISO 21505:2017 Project, programme and portfolio management - Guidance on governance

- ISO 31000:2009 – Risk management.

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 16326:2009 – Systems and Software Engineering—Life Cycle Processes—Project Management[76]

- Individual Competence Baseline (ICB) from the International Project Management Association (IPMA).[77]

- Capability Maturity Model (CMM) from the Software Engineering Institute.

- GAPPS, Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards – an open source standard describing COMPETENCIES for project and program managers.

- HERMES method, Swiss general project management method, selected for use in Luxembourg and international organizations.

- The logical framework approach (LFA), which is popular in international development organizations.

- PMBOK Guide from the Project Management Institute (PMI).

- PRINCE2 from AXELOS.

- PM2: The Project Management methodology developed by the [European Commission].[78]

- Procedures for Project Formulation and Management (PPFM) by the Indian Ministry of Defence [79]

- Team Software Process (TSP) from the Software Engineering Institute.

- Total Cost Management Framework, AACE International's Methodology for Integrated Portfolio, Program and Project Management.

- V-Model, an original systems development method.

Program management and project networks

[edit]Some projects, either identical or different, can be managed as program management. Programs are collections of projects that support a common objective and set of goals. While individual projects have clearly defined and specific scope and timeline, a program's objectives and duration are defined with a lower level of granularity.

Besides programs and portfolios, additional structures that combine their different characteristics are: project networks, mega-projects, or mega-programs.

A project network is a temporary project formed of several different distinct evolving phases, crossing organizational lines. Mega-projects and mega-programs are defined as exceptional in terms of size, cost, public and political attention, and competencies required.[60]

Project portfolio management

[edit]An increasing number of organizations are using what is referred to as project portfolio management (PPM) as a means of selecting the right projects and then using project management techniques[80] as the means for delivering the outcomes in the form of benefits to the performing public, private or not-for-profit organization.

Portfolios are collections of similar projects. Portfolio management supports efficiencies of scale, increasing success rates, and reducing project risks, by applying similar standardized techniques to all projects in the portfolio, by a group of project management professionals sharing common tools and knowledge. Organizations often create project management offices as an organizational structure to support project portfolio management in a structured way.[60] Thus, PPM is usually performed by a dedicated team of managers organized within an enterprise project management office (PMO), usually based within the organization, and headed by a PMO director or chief project officer. In cases where strategic initiatives of an organization form the bulk of the PPM, the head of the PPM is sometimes titled as the chief initiative officer.

Project management software

[edit]Project management software is software used to help plan, organize, and manage resource pools, develop resource estimates and implement plans. Depending on the sophistication of the software, functionality may include estimation and planning, scheduling, cost control and budget management, resource allocation, collaboration software, communication, decision-making, workflow, risk, quality, documentation, and/or administration systems.[81][82]. A comparison of project management software shows different features included in different software.

Virtual project management

[edit]Virtual program management (VPM) is management of a project done by a virtual team, though it rarely may refer to a project implementing a virtual environment[83] It is noted that managing a virtual project is fundamentally different from managing traditional projects,[84] combining concerns of remote work and global collaboration (culture, time zones, language).[85]

See also

[edit]Related fields

[edit]- Agile construction

- Architectural engineering

- Construction management

- Cost engineering

- Facilitation (business)

- Industrial engineering

- Project Production Management

- Project management software

- Project portfolio management

- Project management office

- Project workforce management

- Software project management

- Systems engineering

Related subjects

[edit]- Agile management is the application of the principles of Agile software development and Lean Management to various management processes, particularly product development.

- Decision-making

- Game theory

- Earned value management

- Human factors

- Kanban (development)

- Kickoff meeting is the first meeting with the project team and with or without the client of the project.

- Operations research

- Outline of project management

- Postmortem documentation is a process used to identify the causes of a project failure, and how to prevent them in the future.

- Process architecture

- Program management

- Project accounting

- Project governance

- Project management office

- Project management simulation

- Return on time invested

- Small-scale project management

- Software development process

- Social project management

- Systems development life cycle (SDLC)

Lists

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Phillips, Joseph (2004). PMP Project Management Professional Study Guide. McGraw-Hill/Osborne. p. 354. ISBN 0072230622.

- ^ Baratta, Angelo (2006). "The triple constraint a triple illusion". PMI. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- ^ Nokes, Sebastian; Kelly, Sean (2007). The Definitive Guide to Project Management: The Fast Track to Getting the Job Done on Time and on Budget. Pearson Education. Prentice Hall Financial Times. ISBN 9780273710974.

- ^ "What is Project Management?". Project Management Institute. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ Dinsmore, Paul C.; Cooke-Davies, Terence J. (November 4, 2005). Right Projects Done Right: From Business Strategy to Successful Project Implementation. Wiley. p. 35. ISBN 0787971138.

- ^ Cattani, Gino; Ferriani, Simone; Frederiksen, Lars; Täube, Florian (2011). Project-Based Organizing and Strategic Management. Advances in Strategic Management. Vol. 28. Leeds, England: Emerald. ISBN 978-1780521930.

- ^ Lock, Dennis. Project Management (9 ed.). ISBN 9780566087721.

- ^ Kwak, Young-Hoon (2005). "A brief History of Project Management". In Elias G. Carayannis (ed.). The story of managing projects. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 1567205062.

- ^ Cleland, David; Gareis, Roland (May 25, 2006). "1: The evolution of project management". Global Project Management Handbook. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 0071460454.

- ^ Stevens, Martin (2002). Project Management Pathways. Association for Project Management. p. xxii. ISBN 190349401X.

- ^ Marsh, Edward R. (1975). "The Harmonogram of Karol Adamiecki". The Academy of Management Journal. 18 (2): 358–364. JSTOR 255537.

- ^ Witzel, Morgen (2003). Fifty Key Figures in Management. Psychology Press. pp. 96–101. ISBN 0415369770.

- ^ Cleland, David; Gareis, Roland (May 25, 2006). Global Project Management Handbook: Planning, Organizing and Controlling International Projects. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0071460454.

It was in the 1950s when project management was formally recognized as a distinct contribution arising from the management discipline.

- ^ Malcolm, D. G.; Roseboom, J. H.; Clark, C. E.; Fazar, W. (1959). "Application of a technique for research and development program evaluation" (PDF). Operations Research. 7 (5): 646–669. doi:10.1287/opre.7.5.646.

- ^ Harrison, F. L.; Lock, Dennis (2004). Advanced Project Management: A Structured Approach. Gower Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 0566078228.

- ^ Saladis, F. P. (2006). "Bringing the PMBOK® guide to life". PMI Global Congress. Seattle, WA: Project Management Institute.

- ^ "Certified Construction Manager". CMAA. Archived from the original on November 28, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ "Certificate in Biotechnology Project Management". University of Washington. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Sha, Mandy; Immerwahr, Stephen (February 19, 2018). "Survey Translation: Why and How Should Researchers and Managers be Engaged?". Survey Practice. 11 (2): 1–10. doi:10.29115/SP-2018-0016.

- ^ Sha, Mandy; Childs, Jennifer Hunter (August 1, 2014). "Applying a project management approach to survey research projects that use qualitative methods". Survey Practice. 7 (4): 1–8. doi:10.29115/SP-2014-0021.

- ^ Esselink, Bert (2000). A Practical Guide to Localization. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 428. ISBN 978-9-027-21956-5.

- ^ Mesly, Olivier (December 15, 2016). Project Feasibility: Tools for Uncovering Points of Vulnerability. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781498757911..

- ^ Cf. The Bridger (blog), "Project management: PMP, Prince 2, or an Iterative or Agile variant"

- ^ Serra, C. E. M.; Kunc, M. (2014). "Benefits Realisation Management and its influence on project success and on the execution of business strategies". International Journal of Project Management. 33 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.03.011.

- ^ "Going Beyond Critical Path Method". www.pmi.org. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Mahmoudi, Amin; Bagherpour, Morteza; Javed, Saad Ahmed (2021). "Grey Earned Value Management: Theory and Applications". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 68 (6): 1703–1721. doi:10.1109/tem.2019.2920904. ISSN 0018-9391. S2CID 202102868.

- ^ Hass, Kathleen B. (Kitty) (March 2, 2010). "Managing Complex Projects that are Too Large, Too Long and Too Costly". PM Times. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ Conforto, E. C.; Salum, F.; Amaral, D. C.; da Silva, S. L.; Magnanini de Almeida, L. F (June 2014). "Can agile project management be adopted by industries other than software development?". Project Management Journal. 45 (3): 21–34. doi:10.1002/pmj.21410. S2CID 110595660.

- ^ Snowden, David J.; Boone, Mary E. (November 2007). "A Leader's Framework for Decision Making". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ Wysocki, Robert K. (2013). Effective Project Management: Traditional, Adaptive, Extreme (Seventh ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118729168.

- ^ Royce, Winston W. (August 25–28, 1970). "Managing the Development of Large Software Systems" (PDF). Technical Papers of Western Electronic Show and Convention (WesCon). Los Angeles. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Stellman, Andrew; Greene, Jennifer (2005). Applied Software Project Management. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00948-9. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015.

- ^ McCaffer, Ronald; Harris, Frank (2013). Modern construction management. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN 978-1118510186. OCLC 834624541.

- ^ Office for Government Commerce (1996) Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, p14

- ^ "OGC – PRINCE2 – Background". Archived from the original on August 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Project Management Guide" (PDF). VA Office of Information and Technology. 2003. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c PMI (2010). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, pp. 27–35.

- ^ Nathan, Peter; Gerald Everett Jones (2003). PMP certification for dummies, p. 63.

- ^ Kerzner, Harold (2003). Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling (8th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-22577-0.

- ^ a b Lewis, James P. (2000). The project manager's desk reference: a comprehensive guide to project planning, scheduling, evaluation, and systems. p. 185.

- ^ Eccles, Robert G. (1981). "The quasifirm in the construction industry". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2 (4): 335–357. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(81)90013-5. ISSN 0167-2681.

- ^ Davies, Andrew; Hobday, Michael (2005). The Business of projects: managing innovation in complex products and systems. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84328-7.

- ^ Gann, David; Salter, Ammon; Dodgson, Mark; Philips, Nelson (2012). "Inside the world of the project baron". MIT Sloan Management Review. 53 (3): 63–71. ISSN 1532-9194.

- ^ Meng, Xianhai (2012). "The effect of relationship management on project performance in construction". International Journal of Project Management. 30 (2): 188–198. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2011.04.002.

- ^ Cohen-Kashi, S.; Rozenes, S.; Ben-Gal, I. "Project Management Monitoring Based on Expected Duration Entropy" (PDF). In Entropy 2020, 22, 905.

- ^ Becker, Jarg; Kugeler, Martin; Rosemann, Michael (2003). Process Management: A guide for the design of business processes. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 9783540434993.

- ^ Schlagheck, Bernhard (2000). Objektorientierte Referenzmodelle für das Prozess- und Projektcontrolling: Grundlagen - Konstruktion - Anwendungsmöglichkeiten. ISBN 978-3-8244-7162-1, p. 131.

- ^ Riedl, Josef E. (1990). Projekt-Controlling in Forschung und Entwicklung. ISBN 978-3-540-51963-8, p. 99.

- ^ Steinle, Bruch, Lawa (1995). Projektmanagement. FAZ Verlagsbereich Wirtschaftsbücher, pp. 136–143.

- ^ Snyder, Cynthia; Frank Parth (2006). Introduction to IT Project Management, pp. 393–397.

- ^ Abdou, Saed M; Yong, Kuan; Othman, Mohammed (2016). "Project Complexity Influence on Project management performance – The Malaysian perspective". MATEC Web of Conferences. 66: 00065. doi:10.1051/matecconf/20166600065. ISSN 2261-236X.

- ^ Morcov, Stefan; Pintelon, Liliane; Kusters, Rob J. (2020). "Definitions, characteristics and measures of IT Project Complexity - a Systematic Literature Review" (PDF). International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management. 8 (2): 5–21. doi:10.12821/ijispm080201. S2CID 220545211.

- ^ a b Marle, Franck; Vidal, Ludovic-Alexandre (2016). Managing Complex, High Risk Projects - A Guide to Basic and Advanced Project Management. London: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Vidal, Ludovic-Alexandre; Marle, Franck; Bocquet, Jean-Claude (2011). "Measuring project complexity using the Analytic Hierarchy Process" (PDF). International Journal of Project Management. 29 (6): 718–727. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2010.07.005. S2CID 111186583.

- ^ Vidal, Ludovic-Alexandre; Marle, Franck (2008). "Understanding project complexity: implications on project management" (PDF). Kybernetes. 37 (8): 1094–1110. doi:10.1108/03684920810884928.

- ^ Baccarini, D. (1996). "The concept of project complexity, a review". International Journal of Project Management. 14 (4): 201–204. doi:10.1016/0263-7863(95)00093-3.

- ^ Snowden, David J.; Boone, Mary E. (2007). "A Leader's Framework for Decision Making". Harvard Business Review. 85 (11): 68–76.

- ^ Maurer, Maik (2017). Complexity Management in Engineering Design – a Primer. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- ^ Kurtz, C. F.; Snowden, David J. (2003). "The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world". IBM Systems Journal. 42 (3): 462–483. doi:10.1147/sj.423.0462. S2CID 1571304.

- ^ a b c d e f Morcov, S. (2021). "Managing Positive and Negative Complexity: Design and Validation of an IT Project Complexity Management Framework". KU Leuven University.

- ^ Morris, Peter (1994). The management of projects. London: T. Telford. p. 317. ISBN 978-0727725936. OCLC 30437274.

- ^ Dennis Lock; Lindsay Scott, eds. (2013). Gower handbook of people in project management. Farnham, Surrey: Gower Publishing. p. 398. ISBN 978-1409437857. OCLC 855019788.

- ^ "PMOs". www.theprojectmanager.co.za. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Commission, Australian Public Service. "APS framework for optimal management structures". Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Morcov, Stefan; Pintelon, Liliane; Kusters, Rob J. (2020). "IT Project Complexity Management Based on Sources and Effects: Positive, Appropriate and Negative" (PDF). Proceedings of the Romanian Academy - Series A. 21 (4): 329–336.

- ^ Daniel, Pierre A.; Daniel, Carole (January 2018). "Complexity, uncertainty and mental models: From a paradigm of regulation to a paradigm of emergence in project management". International Journal of Project Management. 36 (1): 184–197. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.07.004.

- ^ Pinto, Jeffrey K.; Winch, Graham (February 1, 2016). "The unsettling of 'settled science:' The past and future of the management of projects". International Journal of Project Management. 34 (2): 237–245. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.07.011.

- ^ Morcov, Stefan (April 6, 2021). "Project success vs. project management performance".

- ^ Bannerman, P. L. (2008). "Defining project success: a multilevel framework". Defining the Future of Project Management. Warsaw, Poland: Project Management Institute.

- ^ Camilleri, Emanuel (2011). Project Success: Critical Factors and Behaviours. Gower Publishing, Ltd.

- ^ The KPI Institute, "KPI of the Day – Business Consulting (BC): $ Backlog of commissioned projects". Performance Magazine, 16 March 2021. Accessed 23 December 2022.

- ^ "DoDD 5000.01" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ "Taking the risk out of risk management: Holistic approach to enterprise risk management". Strategic Direction. 32 (5): 28–30. January 1, 2016. doi:10.1108/SD-02-2016-0030. ISSN 0258-0543.

- ^ a b NASA NPR 9501.2D. May 23, 2001.

- ^ Levine, H. A. (1993). "Doing the weebis and the obis: new dances for project managers?" PM Network, 7(4), 35–38.

- ^ ISO/IEC/IEEE Systems and Software Engineering--Life Cycle Processes--Project Management. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2009.5372630. ISBN 978-0-7381-6116-7.

- ^ Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management (PDF). International Project Management Association (IPMA). 2015. ISBN 978-94-92338-01-3.

- ^ European Commission. PM2: The Project Management methodology developed by the European Commission.

- ^ Mohindra, T., & Srivastava, M. (2019). "Comparative Analysis of Project Management Frameworks and Proposition for Project Driven Organizations". PM World Journal, VIII(VIII).

- ^ Hamilton, Albert (2004). Handbook of Project Management Procedures. TTL Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7277-3258-7

- ^ PMBOK 4h Ed. PMI, Project Management Inst. 2008. p. 443. ISBN 978-1933890517.

- ^ Kendrick, Tom (2013). The Project Management Tool Kit: 100 Tips and Techniques for Getting the Job Done Right, Third Edition. AMACOM Books. ISBN 9780814433454

- ^ Curlee, Wanda (2011). The Virtual Project Management Office: Best Practices, Proven Methods. Management Concepts Press.

- ^ Khazanchi, Deepak (2005). Patterns of Effective Project Management in Virtual Projects: An Exploratory Study. Project Management Institute. ISBN 9781930699830. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013.

- ^ Velagapudi, Mridula (April 13, 2012). "Why You Cannot Avoid Virtual Project Management 2012 Onwards".

External links

[edit]- Guidelines for Managing Projects from the UK Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR)

Media related to Project management at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Project management at Wikimedia Commons

Project management

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and Fundamentals

Definition and Scope

Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the requirements of those projects.[1] This discipline operates within the framework of the triple constraint—scope, time (or schedule), and cost—which represents the interrelated limitations that must be balanced to achieve project goals, as any adjustment to one constraint impacts the others.[11] The primary objective of project management is to deliver unique products, services, or results that align with stakeholder expectations, while effectively managing competing demands such as resources, quality, and risk. Projects are defined as temporary endeavors with a definite beginning and end, undertaken to create these distinctive outputs, thereby enabling organizations to achieve specific, non-repetitive goals. In contrast to ongoing business operations, which involve repetitive processes to sustain day-to-day functions indefinitely, projects are inherently temporary and focused on producing novel outcomes rather than maintaining steady-state activities. Fundamental terminology in project management includes deliverables, which are the verifiable products, services, or results produced by the project; milestones, defined as significant points or events marking the completion of key phases or achievements; and constraints, encompassing the boundaries like scope, time, and cost that shape project execution.[12]Characteristics of Projects

Projects are fundamentally distinguished from ongoing operational activities by several key attributes that define their nature and execution. Central to this is their temporary nature, wherein a project has a definite beginning and a definite end in time, typically concluding upon the achievement of its objectives or when the need for the project ceases.[2] This temporality ensures that projects are not indefinite endeavors but finite efforts designed to deliver specific outcomes within a bounded timeframe, contrasting with routine business operations that continue indefinitely.[13] Another defining trait is the uniqueness of each project, which produces a distinct product, service, or result not replicated in routine work.[2] Unlike standardized processes, projects involve novel elements, such as custom designs or adaptations to specific contexts, even if they incorporate repetitive components. For instance, while manufacturing multiple units of a product may include repeatable steps, the initial development of that product qualifies as a unique project.[14] This uniqueness often necessitates innovation, problem-solving, and tailored approaches, setting projects apart from operational maintenance activities like ongoing facility upkeep.[15] Projects also exhibit progressive elaboration, a characteristic that integrates their temporary and unique aspects by allowing details to evolve iteratively as more information emerges.[16] Initially defined at a high level, project scope and plans are refined through incremental steps, enabling greater precision without requiring full upfront specificity. This approach accommodates uncertainty inherent in unique endeavors, such as evolving requirements in software development or design iterations in construction.[17] Finally, projects operate under resource constraints, drawing on a limited allocation of organizational assets—including personnel, budget, equipment, and materials—specifically dedicated to achieving the project's goals.[18] These constraints, often encompassing time, cost, and scope (commonly referred to as the triple constraint), demand careful planning and control to ensure efficient utilization, distinguishing projects from broader, ongoing resource pools in operations. An illustrative example is the construction of a new bridge, which requires a finite team and budget for a set duration, versus routine bridge maintenance that uses general operational resources continuously.[2]Project Complexity

Project complexity arises from the interplay of multiple interdependent factors, including project size, technological requirements, and stakeholder involvement, which collectively make projects difficult to predict, control, and manage. This complexity is often characterized by structural elements, such as the variety and interconnectedness of tasks and resources, and technological elements, like novel or uncertain innovations. Unlike simpler endeavors, projects exhibit this complexity due to their inherent uniqueness and temporary nature, demanding tailored approaches beyond standard processes.[19][20] Positive complexity refers to beneficial aspects where intricate interactions foster innovation, emergent properties, and enhanced value creation, as unforeseen synergies among project elements can lead to outcomes surpassing initial expectations. In contrast, requisite or appropriate complexity represents the optimal level needed to achieve project objectives, balancing necessary intricacy with efficiency to avoid under- or over-complication; this aligns with principles like the law of requisite variety, ensuring the project's structure matches its goals without excess. Negative complexity, however, emerges when entanglements become excessive, resulting in heightened uncertainty, delays, increased costs, and potential failure due to unpredictable behaviors and control challenges.[20][21][22] Contributing factors to project complexity span several dimensions: technical factors involve task variety, technological interdependencies (e.g., pooled, sequential, or reciprocal integrations), and innovation novelty; organizational factors include team size, stakeholder diversity, division of labor, and management structures; environmental factors encompass external uncertainties like regulatory changes, market volatility, and resource scarcity; and social factors account for cultural differences, competing stakeholder interests, and communication dynamics. These elements often interact, amplifying overall complexity.[19][20][21] Managing project complexity requires adaptive strategies that address its multifaceted nature, such as employing systems-thinking models (e.g., Cynefin framework for contextual decision-making) and tailored integration mechanisms to mitigate negative effects while leveraging positive ones. Project managers must assess and calibrate complexity levels to maintain requisite balance, using tools like dependency mapping to enhance control and foresight, ultimately improving success rates in intricate environments.[22][20]Historical Development

Early History

The construction of the Egyptian pyramids, such as the Great Pyramid of Giza built around 2580–2565 BC, exemplifies early forms of project management through meticulous planning, labor organization, and resource allocation, involving the coordination of thousands of workers and the transportation of massive stone blocks over long distances.[23] Similarly, the Roman aqueducts, constructed over centuries starting from the 4th century BC, demonstrated advanced resource management and engineering foresight, with systems like the Aqua Appia (312 BC) requiring precise surveying, material sourcing, and workforce scheduling to deliver water across vast terrains.[23] These ancient endeavors highlight rudimentary project practices focused on scope definition, timeline adherence, and logistical coordination, laying foundational concepts for later developments.[23] The Industrial Revolution in the late 18th and 19th centuries spurred the emergence of more systematic project management approaches in construction and engineering, driven by the scale of infrastructure projects like railways and factories that demanded efficient labor division, material supply chains, and cost controls.[24] Engineers such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel in Britain applied structured planning to ventures like the Great Western Railway (1833–1841), integrating budgeting, risk assessment, and phased execution to manage complex builds amid technological shifts.[25] This era transitioned project efforts from ad hoc methods to formalized processes, emphasizing productivity gains through mechanization and standardized workflows in heavy engineering.[24] In the early 20th century, Henry Gantt introduced Gantt charts in the 1910s as a visual scheduling tool to track project tasks, dependencies, and progress, initially applied in manufacturing and construction to improve efficiency during World War I shipbuilding efforts.[26] Complementing this, Frederick Taylor's principles of scientific management, outlined in his 1911 book The Principles of Scientific Management, influenced project practices by advocating time-motion studies, worker training, and optimized task allocation to enhance overall project performance.[27] Key contributors like Willard Fazar, with his early industrial experience in economics and operations at firms such as U.S. Steel before 1950, helped bridge these ideas toward more integrated management systems.[28] These innovations marked the shift toward tool-based project oversight. World War I and II accelerated project management through military logistics, with initiatives like the Manhattan Project (1942–1946) exemplifying coordinated team efforts across scientists, engineers, and contractors to achieve the atomic bomb's development under tight secrecy and deadlines.[29] Led by General Leslie Groves, the project involved over 130,000 personnel at multiple sites, utilizing hierarchical structures, resource pooling, and milestone tracking to navigate unprecedented complexity and scale.[29] Such wartime projects underscored the value of multidisciplinary collaboration and adaptive planning in high-stakes environments.[29]Modern Developments

Following World War II, project management saw significant formalization through the development of structured techniques for planning and scheduling large-scale projects. The Critical Path Method (CPM) was introduced in 1957 by DuPont engineers James E. Kelley and Morgan R. Walker to optimize plant maintenance and construction schedules, emphasizing the identification of the longest sequence of dependent tasks to determine project duration.[30] Concurrently, the U.S. Navy developed the Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) in 1958 for the Polaris missile program, incorporating probabilistic time estimates to handle uncertainty in complex defense projects.[31] These methods marked a shift toward quantitative, network-based approaches, influencing industries beyond their origins in chemical engineering and military applications. In the 1960s and 1970s, the discipline gained institutional support through the establishment of professional organizations dedicated to standardizing practices. The International Project Management Association (IPMA), originally founded as the International Management Systems Association (IMSA) in 1965 in Switzerland, aimed to foster global collaboration among project managers and promote competence-based certification.[32] Five years later, in 1969, the Project Management Institute (PMI) was formed in the United States following a meeting at the Georgia Institute of Technology, with the goal of advancing the profession through knowledge sharing and ethical standards.[9] These bodies provided platforms for practitioners to exchange ideas, contributing to the recognition of project management as a distinct field. The 1980s and 1990s brought the rise of codified standards and integration with broader quality management frameworks. PMI published the initial Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) document in 1987, outlining core processes, terminology, and best practices to guide project execution.[33] In the UK, PRINCE2 (Projects IN Controlled Environments) emerged in 1996 as an evolution of the earlier PROMPT methodology, offering a process-based standard tailored for government and commercial projects with emphasis on controlled stages and business justification.[34] During this period, project management increasingly aligned with ISO 9000 quality standards, first issued in 1987, which encouraged process-oriented approaches to ensure consistency and customer satisfaction in project deliverables.[35] From the 2000s onward, project management adapted to globalization, rapid technological change, and demands for flexibility. The Agile Manifesto, published in 2001 by a group of software developers, prioritized iterative development, customer collaboration, and responsiveness to change, influencing a shift from rigid plans to adaptive frameworks across industries.[36] This era also saw the proliferation of digital tools, such as cloud-based collaboration platforms and project management software, enabling real-time tracking and remote teams amid global supply chains.[37] Key milestones underscore the profession's maturation, including PMI's expansion to over 770,000 members as of 2024, reflecting widespread adoption and the need for certified expertise in diverse sectors.[38] Digital transformation has further embedded project management in strategic initiatives, with tools like AI-driven analytics enhancing risk prediction and resource allocation since the mid-2010s, and the release of the PMBOK Guide Eighth Edition in 2025 continuing to evolve standards for contemporary practices.[39][5]Project Lifecycle and Processes