Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Slavic languages

View on Wikipedia

| Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Slavonic | |

| Geographic distribution | Throughout Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Europe, plus Central Asia and North Asia (Siberia) |

| Ethnicity | Slavs |

Native speakers | c. 315 million (2001)[1] |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Slavic |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | sla |

| Linguasphere | 53 (phylozone) |

| Glottolog | slav1255 |

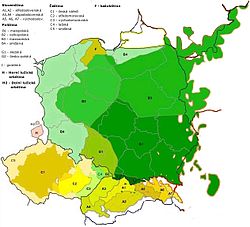

Political map of Europe with countries where a Slavic language is a national language East Slavic languages

South Slavic languages

West Slavic languages | |

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic, spoken during the Early Middle Ages, which in turn is thought to have descended from the earlier Proto-Balto-Slavic language, linking the Slavic languages to the Baltic languages in a Balto-Slavic group within the Indo-European family.

The current geographical distribution of natively spoken Slavic languages includes the Balkans, Central and Eastern Europe, and all the way from Western Siberia to the Russian Far East. Furthermore, the diasporas of many Slavic peoples have established isolated minorities of speakers of their languages all over the world. The number of speakers of all Slavic languages together was estimated to be 315 million at the turn of the twenty-first century.[1] It is the largest and most diverse ethno-linguistic group in Europe.[2][3]

The Slavic languages are conventionally (that is, also on the basis of extralinguistic features, such as geography) divided into three subgroups: East, South, and West, which together constitute more than 20 languages. Of these, 10 have at least one million speakers and official status as the national languages of the countries in which they are predominantly spoken: Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian (of the East group), Polish, Czech and Slovak (of the West group), Bulgarian and Macedonian (eastern members of the South group), and Serbo-Croatian and Slovene (western members of the South group). In addition, Aleksandr Dulichenko recognizes a number of Slavic microlanguages: both isolated ethnolects and peripheral dialects of more well-established Slavic languages.[4][5][page needed][6]

All Slavic languages have fusional morphology and, with a partial exception of Bulgarian and Macedonian, they have fully developed inflection-based conjugation and declension. In their relational synthesis Slavic languages distinguish between lexical and inflectional suffixes. In all cases, the lexical suffix precedes the inflectional in an agglutination mode. The fusional categorization of Slavic languages is based on grammatic inflectional suffixes alone.

Prefixes are also used, particularly for lexical modification of verbs. For example, the equivalent of English "came out" in Russian is "vyshel", where the prefix "vy-" means "out", the reduced root "-sh" means "come", and the suffix "-el" denotes past tense of masculine gender. The equivalent phrase for a feminine subject is "vyshla". The gender conjugation of verbs, as in the preceding example, is another feature of some Slavic languages rarely found in other language groups.

The well-developed fusional grammar allows Slavic languages to have a somewhat unusual feature of virtually free word order in a sentence clause, although subject–verb–object and adjective-before-noun is the preferred order in the neutral style of speech.[7]

Branches

[edit]

Since the interwar period,[specify] scholars have conventionally divided Slavic languages, on the basis of geographical and genealogical principle, and with the use of the extralinguistic feature of script, into three main branches, that is, East, South, and West (from the vantage of linguistic features alone, there are only two branches of the Slavic languages, namely North and South).[8] These three conventional branches feature some of the following sub-branches:

- Slavic

- East Slavic[9]

- Belarusian

- Russian

- Rusyn (often seen as a dialect of Ukrainian)[10]

- Ukrainian

- Podlachian (often seen as a dialect of Ukrainian)

- West Polesian (often seen as a dialect of Ukrainian)

- South Slavic

- West Slavic

- Czech–Slovak

- Lechitic

- Polabian

- Polish

- Pomeranian

- Kashubian

- Slovincian (often seen as a dialect of Kashubian)

- Silesian

- Sorbian

- East Slavic[9]

Some linguists speculate that a North Slavic branch has existed as well. The Old Novgorod dialect may have reflected some idiosyncrasies of this group.[11]

Slavic languages diverged from a common proto-language later than any other groups of the Indo-European language family, and enough differences exist between the any two geographically distant Slavic languages to make spoken communication between such speakers cumbersome. As usually found within other language groups, mutual intelligibility between Slavic languages is better for geographically adjacent languages and in the written (rather than oral) form.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18] Recent studies of mutual intelligibility between Slavic languages have said, that their traditional three-branch division does not withstand quantitative scrutiny.[19][neutrality is disputed] While the grouping of Czech, Slovak and Polish into West Slavic turned out to be appropriate, Western South Slavic Serbo-Croatian and Slovene were found to be closer to Czech and Slovak (West Slavic languages) than to Eastern South Slavic Bulgarian.

The traditional tripartite division of the Slavic languages does not take into account the spoken dialects of each language. Within the individual Slavic languages, dialects may vary to a lesser degree, as those of Russian, or to a much greater degree, like those of Slovene. In certain cases transitional dialects and hybrid dialects often bridge the gaps between different languages, showing similarities that do not stand out when comparing Slavic literary (i.e. standard) languages. For example, Slovak (West Slavic) and Ukrainian (East Slavic) are bridged by the Rusyn language spoken in Transcarpatian Ukraine and adjacent counties of Slovakia and Ukraine.[20] Similarly, the Croatian Kajkavian dialect is more similar to Slovene than to the standard Croatian language.[citation needed]

Modern Russian differs from other Slavic languages in an unusually high percentage[citation needed][21] of words of non-Slavic origin, particularly of Dutch (e.g. for naval terms introduced during the reign of Peter I), French (for household and culinary terms during the reign of Catherine II) and German (for medical, scientific and military terminology in the mid-1800s).

Another difference between the East, South, and West Slavic branches is in the orthography of the standard languages: West Slavic languages (and Western South Slavic languages – Croatian and Slovene) are written in the Latin script, and have had more Western European influence due to their proximity and speakers being historically Roman Catholic, whereas the East Slavic and Eastern South Slavic languages are written in Cyrillic and, with Eastern Orthodox or Eastern-Catholic faith, have had more Greek influence.[22] Two Slavic languages, Belarusian and Serbo-Croatian, are biscriptal, i.e. written in either alphabet either presently or in a recent past.

History

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Common roots and ancestry

[edit]

Slavic languages descend from Proto-Slavic, their immediate parent language, ultimately deriving from Proto-Indo-European, the ancestor language of all Indo-European languages, via a Proto-Balto-Slavic stage. During the Proto-Balto-Slavic period a number of exclusive isoglosses in phonology, morphology, lexis, and syntax developed, which makes Slavic and Baltic the closest related of all the Indo-European branches. The secession of the Balto-Slavic dialect ancestral to Proto-Slavic is estimated on archaeological and glottochronological criteria to have occurred sometime in the period 1500–1000 BCE.[23]

A minority of Baltists maintain the view that the Slavic group of languages differs so radically from the neighboring Baltic group (Lithuanian, Latvian, and the now-extinct Old Prussian), that they could not have shared a parent language after the breakup of the Proto-Indo-European continuum about five millennia ago. Substantial advances in Balto-Slavic accentology that occurred in the last three decades, however, make this view very hard to maintain nowadays, especially when one considers that there was most likely no "Proto-Baltic" language and that West Baltic and East Baltic differ from each other as much as each of them does from Proto-Slavic.[24]

Differentiation

[edit]The Proto-Slavic language originated in the area of modern Ukraine and Belarus mostly overlapping with the northern part of Indoeuropean Urheimat, which is within the boundaries of modern Ukraine and Southern Federal District of Russia.[25]

The Proto-Slavic language existed until around AD 500. By the 7th century, it had broken apart into large dialectal zones.[citation needed] There are no reliable hypotheses about the nature of the subsequent breakups of West and South Slavic. East Slavic is generally thought to converge to one Old East Slavic language of Kievan Rus, which existed until at least the 12th century.

Linguistic differentiation was accelerated by the dispersion of the Slavic peoples over a large territory, which in Central Europe exceeded the current extent of Slavic-speaking majorities. Written documents of the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries already display some local linguistic features. For example, the Freising manuscripts show a language that contains some phonetic and lexical elements peculiar to Slovene dialects (e.g. rhotacism, the word krilatec). The Freising manuscripts are the first Latin-script continuous text in a Slavic language.

The migration of Slavic speakers into the Balkans in the declining centuries of the Byzantine Empire expanded the area of Slavic speech, but the pre-existing writing (notably Greek) survived in this area. The arrival of the Hungarians in Pannonia in the 9th century interposed non-Slavic speakers between South and West Slavs. Frankish conquests completed the geographical separation between these two groups, also severing the connection between Slavs in Moravia and Lower Austria (Moravians) and those in present-day Styria, Carinthia, East Tyrol in Austria, and in the provinces of modern Slovenia, where the ancestors of the Slovenes settled during first colonization.

In September 2015, Alexei Kassian and Anna Dybo published,[26] as a part of interdisciplinary study of Slavic ethnogenesis,[27] a lexicostatistical classification of Slavic languages. It was built using qualitative 110-word Swadesh lists that were compiled according to the standards of the Global Lexicostatistical Database project[28] and processed using modern phylogenetic algorithms.

The resulting dated tree complies with the traditional expert views on the Slavic group structure. Kassian-Dybo's tree suggests that Proto-Slavic first diverged into three branches: Eastern, Western and Southern. The Proto-Slavic break-up is dated to around 100 A.D., which correlates with the archaeological assessment of Slavic population in the early 1st millennium A.D. being spread on a large territory[29] and already not being monolithic.[30] Then, in the 5th and 6th centuries A.D., these three Slavic branches almost simultaneously divided into sub-branches, which corresponds to the fast spread of the Slavs through Eastern Europe and the Balkans during the second half of the 1st millennium A.D. (the so-called Slavicization of Europe).[31][32][33][34]

The Slovenian language was excluded from the analysis, as both Ljubljana koine and Literary Slovenian show mixed lexical features of Southern and Western Slavic languages (which could possibly indicate the Western Slavic origin of Slovenian, which for a long time was being influenced on the part of the neighboring Serbo-Croatian dialects),[original research?] and the quality Swadesh lists were not yet collected for Slovenian dialects. Because of scarcity or unreliability of data, the study also did not cover the so-called Old Novgordian dialect, the Polabian language and some other Slavic lects.

The above Kassian-Dybo's research did not take into account the findings by Russian linguist Andrey Zaliznyak who stated that, until the 14th or 15th century, major language differences were not between the regions occupied by modern Belarus, Russia and Ukraine,[35] but rather between the north-west (around modern Velikiy Novgorod and Pskov) and the center (around modern Kyiv, Suzdal, Rostov, Moscow as well as Belarus) of the East Slavic territories.[36] The Old Novgorodian dialect of that time differed from the central East Slavic dialects as well as from all other Slavic languages much more than in later centuries.[37][38] According to Zaliznyak, the Russian language developed as a convergence of that dialect and the central ones,[39] whereas Ukrainian and Belarusian were continuation of development of the central dialects of East Slavs.[40]

Also Russian linguist Sergey Nikolaev, analysing historical development of Slavic dialects' accent system, concluded that a number of other tribes in Kievan Rus came from different Slavic branches and spoke distant Slavic dialects.[41][page needed]

Zaliznyak and Nikolaev's points mean that there was a convergence stage before the divergence or simultaneously, which was not taken into consideration by Kassian-Dybo's research.

Ukrainian linguists (Stepan Smal-Stotsky, Ivan Ohienko, George Shevelov, Yevhen Tymchenko, Vsevolod Hantsov, Olena Kurylo) deny the existence of a common Old East Slavic language at any time in the past.[42] According to them, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages.[43]

Linguistic history

[edit]The following is a summary of the main changes from Proto-Indo-European (PIE) leading up to the Common Slavic (CS) period immediately following the Proto-Slavic language (PS).

- Satemisation:

- PIE *ḱ, *ǵ, *ǵʰ → *ś, *ź, *źʰ (→ CS *s, *z, *z)

- PIE *kʷ, *gʷ, *gʷʰ → *k, *g, *gʰ

- Ruki rule: Following *r, *u, *k or *i, PIE *s → *š (→ CS *x)

- Loss of voiced aspirates: PIE *bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ → *b, *d, *g

- Merger of *o and *a: PIE *a/*o, *ā/*ō → PS *a, *ā (→ CS *o, *a)

- Law of open syllables: All closed syllables (syllables ending in a consonant) are eventually eliminated, in the following stages:

- Nasalization: With *N indicating either *n or *m not immediately followed by a vowel: PIE *aN, *eN, *iN, *oN, *uN → *ą, *ę, *į, *ǫ, *ų (→ CS *ǫ, *ę, *ę, *ǫ, *y). (NOTE: *ą *ę etc. indicates a nasalized vowel.)

- In a cluster of obstruent (stop or fricative) + another consonant, the obstruent is deleted unless the cluster can occur word-initially.

- (occurs later, see below) Monophthongization of diphthongs.

- (occurs much later, see below) Elimination of liquid diphthongs (e.g. *er, *ol when not followed immediately by a vowel).

- First palatalization: *k, *g, *x → CS *č, *ž, *š (pronounced [tʃ], [ʒ], [ʃ] respectively) before a front vocalic sound (*e, *ē, *i, *ī, *j).

- Iotation: Consonants are palatalized by an immediately following *j:

- sj, *zj → CS *š, *ž

- nj, *lj, *rj → CS *ň, *ľ, *ř (pronounced [nʲ lʲ rʲ] or similar)

- tj, *dj → CS *ť, *ď (probably palatal stops, e.g. [c ɟ], but developing in different ways depending on the language)

- bj, *pj, *mj, *wj → *bľ, *pľ, *mľ, *wľ (the lateral consonant *ľ is mostly lost later on in West Slavic)

- Vowel fronting: After *j or some other palatal sound, back vowels are fronted (*a, *ā, *u, *ū, *ai, *au → *e, *ē, *i, *ī, *ei, *eu). This leads to hard/soft alternations in noun and adjective declensions.

- Prothesis: Before a word-initial vowel, *j or *w is usually inserted.

- Monophthongization: *ai, *au, *ei, *eu, *ū → *ē, *ū, *ī, *jū, *ȳ [ɨː]

- Second palatalization: *k, *g, *x → CS *c [ts], *dz, *ś before new *ē (from earlier *ai). *ś later splits into *š (West Slavic), *s (East/South Slavic).

- Progressive palatalization (or "third palatalization"): *k, *g, *x → CS *c, *dz, *ś after *i, *ī in certain circumstances.

- Vowel quality shifts: All pairs of long/short vowels become differentiated as well by vowel quality:

- a, *ā → CS *o, *a

- e, *ē → CS *e, *ě (originally a low-front sound [æ] but eventually raised to [ie] in most dialects, developing in divergent ways)

- i, *u → CS *ь, *ъ (also written *ĭ, *ŭ; lax vowels as in the English words pit, put)

- ī, *ū, *ȳ → CS *i, *u, *y

- Elimination of liquid diphthongs: Liquid diphthongs (sequences of vowel plus *l or *r, when not immediately followed by a vowel) are changed so that the syllable becomes open:

- or, *ol, *er, *el → *ro, *lo, *re, *le in West Slavic.

- or, *ol, *er, *el → *oro, *olo, *ere, *olo in East Slavic.

- or, *ol, *er, *el → *rā, *lā, *re, *le in South Slavic.

- Possibly, *ur, *ul, *ir, *il → syllabic *r, *l, *ř, *ľ (then develops in divergent ways).

- Development of phonemic tone and vowel length (independent of vowel quality): Complex developments (see History of accentual developments in Slavic languages).

Features

[edit]The Slavic languages are a relatively homogeneous family, compared with other families of Indo-European languages (e.g. Germanic, Romance, and Indo-Iranian). As late as the 10th century AD, the entire Slavic-speaking area still functioned as a single, dialectally differentiated language, termed Common Slavic. Compared with most other Indo-European languages, the Slavic languages are quite conservative, particularly in terms of morphology (the means of inflecting nouns and verbs to indicate grammatical differences). Most Slavic languages have a rich, fusional morphology that conserves much of the inflectional morphology of Proto-Indo-European.[44] The vocabulary of the Slavic languages is also of Indo-European origin. Many of its elements, which do not find exact matches in the ancient Indo-European languages, are associated with the Balto-Slavic community.[45]

Consonants

[edit]The following table shows the inventory of consonants of Late Common Slavic:[46]

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | |||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | tʲː | dʲː | k | ɡ |

| Affricate | ts | dz | tʃ | |||||

| Fricative | s | z | ʃ, (sʲ1) | ʒ | x | |||

| Trill | r | rʲ | ||||||

| Lateral | l | lʲ | ||||||

| Approximant | ʋ | j | ||||||

1The sound /sʲ/ did not occur in West Slavic, where it had developed to /ʃ/.

This inventory of sounds is quite similar to what is found in most modern Slavic languages. The extensive series of palatal consonants, along with the affricates *ts and *dz, developed through a series of palatalizations that happened during the Proto-Slavic period, from earlier sequences either of velar consonants followed by front vowels (e.g. *ke, *ki, *ge, *gi, *xe, and *xi), or of various consonants followed by *j (e.g. *tj, *dj, *sj, *zj, *rj, *lj, *kj, and *gj, where *j is the palatal approximant ([j], the sound of the English letter "y" in "yes" or "you").

The biggest change in this inventory results from a further general palatalization occurring near the end of the Common Slavic period, where all consonants became palatalized before front vowels. This produced a large number of new palatalized (or "soft") sounds, which formed pairs with the corresponding non-palatalized (or "hard") consonants[44] and absorbed the existing palatalized sounds *lʲ *rʲ *nʲ *sʲ. These sounds were best preserved in Russian but were lost to varying degrees in other languages (particularly Czech and Slovak). The following table shows the inventory of modern Russian:

| Labial | Dental & Alveolar |

Post- alveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | hard | soft | hard | soft | |

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | ||||

| Stop | p b | pʲ bʲ | t d | tʲ dʲ | k ɡ | kʲ ɡʲ | ||

| Affricate | t͡s | (t͡sʲ) | t͡ɕ | |||||

| Fricative | f v | fʲ vʲ | s z | sʲ zʲ | ʂ ʐ | ɕː ʑː | x | xʲ |

| Trill | r | rʲ | ||||||

| Approximant | l | lʲ | j | |||||

This general process of palatalization did not occur in Serbo-Croatian and Slovenian. As a result, the modern consonant inventory of these languages is nearly identical to the Late Common Slavic inventory.

Late Common Slavic tolerated relatively few consonant clusters. However, as a result of the loss of certain formerly present vowels (the weak yers), the modern Slavic languages allow quite complex clusters, as in the Russian word взблеск [vzblʲesk] ("flash"). Also present in many Slavic languages are clusters rarely found cross-linguistically, as in Russian ртуть [rtutʲ] ("mercury") or Polish mchu [mxu] ("moss", gen. sg.). The word for "mercury" with the initial rt- cluster, for example, is also found in the other East and West Slavic languages, although Slovak retains an epenthetic vowel (ortuť).[failed verification][47]

Vowels

[edit]A typical vowel inventory is as follows:

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | (ɨ) | u |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

The sound [ɨ] occurs only in some languages (e.g. Russian and Belarusian), and even in these languages, it is often unclear whether it is its own phoneme or an allophone of /i/. Nonetheless, it is a quite prominent and noticeable characteristic of the languages in which it is present.

Common Slavic also had two nasal vowels: *ę [ẽ] and *ǫ [õ]. However, these are preserved only in modern Polish (along with a few lesser-known dialects and microlanguages; see Yus for more details).

Other phonemic vowels are found in certain languages (e.g. the schwa /ə/ in Bulgarian and Slovenian, distinct high-mid and low-mid vowels in Slovenian, and the lax front vowel /ɪ/ in Ukrainian).

Length, accent, and tone

[edit]An area of great difference among Slavic languages is that of prosody (i.e. syllabic distinctions such as vowel length, accent, and tone). Common Slavic had a complex system of prosody, inherited with little change from Proto-Indo-European. This consisted of phonemic vowel length and a free, mobile pitch accent:

- All vowels could occur either short or long, and this was phonemic (it could not automatically be predicted from other properties of the word).

- There was (at most) a single accented syllable per word, distinguished by higher pitch (as in modern Japanese) rather than greater dynamic stress (as in English).

- Vowels in accented syllables could be pronounced with either a rising or falling tone (i.e. there was pitch accent), and this was phonemic.

- The accent was free in that it could occur on any syllable and was phonemic.

- The accent was mobile in that its position could potentially vary among closely related words within a single paradigm (e.g. the accent might land on a different syllable between the nominative and genitive singular of a given word).

- Even within a given inflectional class (e.g. masculine i-stem nouns), there were multiple accent patterns in which a given word could be inflected. For example, most nouns in a particular inflectional class could follow one of three possible patterns: Either there was a consistent accent on the root (pattern A), predominant accent on the ending (pattern B), or accent that moved between the root and ending (pattern C). In patterns B and C, the accent in different parts of the paradigm shifted not only in location but also type (rising vs. falling). Each inflectional class had its own version of patterns B and C, which might differ significantly from one inflectional class to another.

The modern languages vary greatly in the extent to which they preserve this system. On one extreme, Serbo-Croatian preserves the system nearly unchanged (even more so in the conservative Chakavian dialect); on the other, Macedonian has basically lost the system in its entirety. Between them are found numerous variations:

- Slovenian preserves most of the system but has shortened all unaccented syllables and lengthened non-final accented syllables so that vowel length and accent position largely co-occur.

- Russian and Bulgarian have eliminated distinctive vowel length and tone and converted the accent into a stress accent (as in English) but preserved its position. As a result, the complexity of the mobile accent and the multiple accent patterns still exists (particularly in Russian because it has preserved the Common Slavic noun inflections, while Bulgarian has lost them).

- Czech and Slovak have preserved phonemic vowel length and converted the distinctive tone of accented syllables into length distinctions. The phonemic accent is otherwise lost, but the former accent patterns are echoed to some extent in corresponding patterns of vowel length/shortness in the root. Paradigms with mobile vowel length/shortness do exist but only in a limited fashion, usually only with the zero-ending forms (nom. sg., acc. sg., and/or gen. pl., depending on inflectional class) having a different length from the other forms. (Czech has a couple of other "mobile" patterns, but they are rare and can usually be substituted with one of the "normal" mobile patterns or a non-mobile pattern.)

- Old Polish had a system very much like Czech. Modern Polish has lost vowel length, but some former short-long pairs have become distinguished by quality (e.g. [o oː] > [o u]), with the result that some words have vowel-quality changes that exactly mirror the mobile-length patterns in Czech and Slovak.

Grammar

[edit]Similarly, Slavic languages have extensive morphophonemic alternations in their derivational and inflectional morphology,[44] including between velar and postalveolar consonants, front and back vowels, and a vowel and no vowel.[48]

Selected cognates

[edit]The following is a very brief selection of cognates in basic vocabulary across the Slavic language family, which may serve to give an idea of the sound changes involved. This is not a list of translations: cognates have a common origin, but their meaning may be shifted and loanwords may have replaced them.

| Proto-Slavic | Russian | Ukrainian | Belarusian | Rusyn | Polish | Czech | Slovak | Slovene | Serbo-Croatian | Bulgarian | Macedonian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *uxo (ear) | ухо (úkho) | вухо (vúkho) | вуха (vúkha) | ухо (úkho) | ucho | ucho | ucho | uho | уво / uvo (Serbia only) ухо / uho (Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia) |

ухо (ukhó) | уво (úvo) |

| *ognь (fire) | огонь (ogónʹ) | вогонь (vohónʹ) | агонь (ahónʹ) | огинь (ohénʹ) | ogień | oheň | oheň | ogenj | огањ / oganj | огън (ógǎn) | оган/огин (ógan/ógin) |

| *ryba (fish) | рыба (rýba) | риба (rýba) | рыба (rýba) | рыба (rýba) | ryba | ryba | ryba | riba | риба / riba | риба (ríba) | риба (ríba) |

| *gnězdo (nest) | гнездо (gnezdó) | гнiздо (hnizdó) | гняздо (hnyazdó) | гнïздо (hnʹizdó) | gniazdo | hnízdo | hniezdo | gnezdo | гнездо / gnezdo (ek.) гнијездо / gnijezdo (ijek.) гниздо / gnizdo (ik.) |

гнездо (gnezdó) | гнездо (gnézdo) |

| *oko (eye) | око (óko) (dated, poetic or in set expressions) modern: глаз (glaz) |

око (óko) | вока (vóka) | око (óko) | oko | oko | oko | oko | око / oko | око (óko) | око (óko) |

| *golva (head) | голова (golová) глава (glavá) "chapter or chief, leader, head" |

голова (holová) | галава (halavá) | голова (holová) | głowa | hlava | hlava | glava | глава / glava | глава (glavá) | глава (gláva) |

| *rǫka (hand) | рука (ruká) | рука (ruká) | рука (ruká) | рука (ruká) | ręka | ruka | ruka | roka | рука / ruka | ръка (rǎká) | рака (ráka) |

| *noktь (night) | ночь (nočʹ) | ніч (nič) | ноч (noč) | нуч (nuč) | noc | noc | noc | noč | ноћ / noć | нощ (nosht) | ноќ (noḱ) |

Influence on neighboring languages

[edit]Most languages of the former Soviet Union and of some neighbouring countries (for example, Mongolian) are significantly influenced by Russian, especially in vocabulary. The Romanian, Albanian, and Hungarian languages show the influence of the neighboring Slavic nations, especially in vocabulary pertaining to urban life, agriculture, and crafts and trade—the major cultural innovations at times of limited long-range cultural contact. In each one of these languages, Slavic lexical borrowings represent at least 15% of the total vocabulary. This is potentially because Slavic tribes crossed and partially settled the territories inhabited by ancient Illyrians and Vlachs on their way to the Balkans.[45]

Germanic languages

[edit]This section needs expansion with: No discussion of areal interactions with Scandinavian languages. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (June 2024) |

Max Vasmer, a specialist in Slavic etymology, has claimed that there were no Slavic loans into Proto-Germanic. However, there are isolated Slavic loans (mostly recent) into other Germanic languages. For example, the word for "border" (in modern German Grenze, Dutch grens) was borrowed from the Common Slavic granica. There are, however, many cities and villages of Slavic origin in Eastern Germany, the largest of which are Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. English derives quark (a kind of cheese and subatomic particle) from the German Quark, which in turn is derived from the Slavic tvarog, which means "curd". Many German surnames, particularly in Eastern Germany and Austria, are Slavic in origin. The Nordic languages also have torg/torv (market place) from Old Russian tъrgъ (trŭgŭ) or Polish targ,[49] humle (hops),[50] räka/reke/reje (shrimp, prawn),[51] and, via Middle Low German tolk (interpreter) from Old Slavic tlŭkŭ,[52] and pråm/pram (barge) from West Slavonic pramŭ.[53]

Finno-Ugric languages

[edit]Finnic languages have many words in common with Slavic languages. According to Petri Kallio, this suggests Slavic words being borrowed into Finnic languages, as early as Proto-Finnic.[54] Many loanwords have acquired a Finnicized form, making it difficult to say whether such a word is natively Finnic or Slavic.[55]

Russian dialects have numerous borrowings from Finno-Ugric languages, particularly for forest terms and geographical names.[56][57] This is related to the expansion in 7th to the 11th centuries AD of Slavic people into the areas of Central Russia (near Moscow) previously populated by Finno-Ugric peoples,[58] and the resulting genetic, cultural and linguistic exchange.

Other

[edit]The Czech word robot is now found in most languages worldwide, and the word pistol, probably also from Czech,[59] is found in many European languages.

A well-known Slavic word in almost all European languages is vodka, a borrowing from Russian водка (vodka, lit. 'little water'), from common Slavic voda ('water', cognate to the English word water) with the diminutive ending -ka.[60][a] Owing to the medieval fur trade with Northern Russia, Pan-European loans from Russian include such familiar words as sable.[b] The English word "vampire" was borrowed (perhaps via French vampire) from German Vampir, in turn derived from Serbo-Croatian вампир (vampir), continuing Proto-Slavic *ǫpyrь,[61][62][63][64][65][66][c] although Polish scholar K. Stachowski has argued that the origin of the word is early Slavic *vąpěrь, going back to Turkic oobyr.[67]

Several European languages, including English, have borrowed the word polje (meaning 'large, flat plain') directly from the former Yugoslav languages (i.e. Slovene and Serbo-Croatian). During the heyday of the USSR in the 20th century, many more Russian words became known worldwide: da, Soviet, sputnik, perestroika, glasnost, kolkhoz, etc. Another borrowed Russian term is samovar (lit. 'self-boiling').

Detailed list

[edit]The following tree for the Slavic languages derives from the Ethnologue report for Slavic languages.[68] It includes the ISO 639-1 and ISO 639-3 codes where available.

- Belarusian: ISO 639-1 code: be; ISO 639-3 code: bel

- Russian: ISO 639-1 code: ru; ISO 639-3 code: rus

- Rusyn: ISO 639-3 code: rue

- Ruthenian: ISO 639-3 code: rsk

- Ukrainian: ISO 639-1 code: uk; ISO 639-3 code: ukr

- Western South Slavic languages

- Bosnian: ISO 639-1 code: bs; ISO 639-3 code: bos

- Chakavian: ISO 639-3 code: ckm

- Croatian: ISO 639-1 code: hr; ISO 639-3 code: hrv

- Montenegrin: ISO 639-3 code: cnr

- Serbian: ISO 639-1 code: sr; ISO 639-3 code: srp

- Slavomolisano: ISO 639-3 code: svm

- Slovene: ISO 639-1 code: sl; ISO 639-3 code: slv

- Eastern South Slavic languages

- Bulgarian: ISO 639-1 code: bg; ISO 639-3 code: bul

- Church Slavonic: ISO 639-1 code: cu; ISO 639-3 code: chu

- Macedonian: ISO 639-1 code: mk; ISO 639-3 code: mkd

- Sorbian languages

- Lower Sorbian (also known as Lusatian): ISO 639-3 code: dsb

- Upper Sorbian: ISO 639-3 code: hsb

- Lechitic languages

- Czech–Slovak languages

Para- and supranational languages

- Church Slavonic language, variations of Old Church Slavonic with significant replacement of the original vocabulary by forms from the Old East Slavic and other regional forms. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, Polish Orthodox Church, Macedonian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox Church, and even some Roman Catholic Churches in Croatia continue to use Church Slavonic as a liturgical language. While not used in modern times, the text of a Church Slavonic Roman Rite Mass survives in Croatia and the Czech Republic,[69][70] which is best known through Janáček's musical setting of it (the Glagolitic Mass).

- Interslavic language, a modernized and simplified form of Old Church Slavonic, largely based on material that the modern Slavic languages have in common. Its purpose is to facilitate communication between representatives of different Slavic nations and to enable people who do not know any Slavic language to communicate with Slavs. Because Old Church Slavonic had become too archaic and complex for everyday communication, Pan-Slavic language projects have been created from the 17th century onwards in order to provide the Slavs with a common literary language. Interslavic in its current form was standardized in 2011 after the merger of several older projects.[71]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "vodka". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "sable". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "vampire". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Ivanov 2021, section 1: "The Slavic languages, spoken by some 315 million people at the turn of the 21st century".

- ^ Misachi 2017.

- ^ Barford 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Dulichenko 2005.

- ^ Dulichenko 1981.

- ^ Duličenko 1994.

- ^ Siewierska, Anna and Uhliřová, Ludmila. "An overview of word order in Slavic languages". 1 Constituent Order in the Languages of Europe, edited by Anna Siewierska, Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton, 1998, pp. 105-150. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110812206.105

- ^ Trudgill 2003, p. 36, 95–96, 124–125.

- ^ IRB 2004.

- ^ "North Slavic languages | Information, explanation, historical facts | iNFOPEDIA". Info dla Polaka - Ważne informacje: Polityka, Sport, Motoryzacja. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ Fesenmeier, L., Heinemann, S., & Vicario, F. (2014). "The mutual intelligibility of Slavic languages as a source of support for the revival of the Sorbian language" [Sprachminderheiten: gestern, heute, morgen- Minoranze linguistiche: ieri, oggi, domani]. In Language minorities: yesterday, today, tomorrow. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-04817-9/11

- ^ Fischer, A., Jágrová, K., Stenger, I., Avgustinova, T., Klakow, D., & Marti, R. (2016). Orthographic and morphological correspondences between related Slavic languages as a base for modeling of mutual intelligibility. 10th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, LREC 2016.

- ^ Fischer, A. K., Jagrova, K., Stenger, I., Avgustinova, T., Klakow, D., & Marti, R. (2016, 2016/05/01). LREC - Orthographic and Morphological Correspondences between Related Slavic Languages as a Base for Modeling of Mutual Intelligibility.

- ^ Golubović, J. (2016). "Mutual intelligibility in the Slavic language area". Dissertation in Linguistics, 152. https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai%3Apure.rug.nl%3Apublications%2F19c19b5b-a43e-47bf-af6e-f68c0713342b; https://research.rug.nl/en/publications/mutual-intelligibility-in-the-slavic-language-area ; https://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/31880568/Title_and_contents_.pdf ; https://lens.org/000-445-299-792-024

- ^ Golubovic, J., & Gooskens, C. (2015). "Mutual intelligibility between West and South Slavic languages". Russian Linguistics, 39(3), 351-373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-015-9150-9

- ^ Kyjánek, L., & Haviger, J. (2019). "The Measurement of Mutual Intelligibility between West-Slavic Languages" [Article]. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 26(3), 205-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2018.1464546

- ^ Lindsay, R. (2014). "Mutual intelligibility of languages in the Slavic family". Academia. Stenger, I., Avgustinova, T., & Marti, R. (2017). "Levenshtein distance and word adaptation surprisal as methods of measuring mutual intelligibility in reading comprehension of Slavic languages". Computational Linguistics and Intellectual Technologies: International Conference 'Dialogue 2017' Proceedings, 16, 304-317. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85021828413&partnerID=40&md5=c9a8557c3da885eb1be39898bfacf6e4

- ^ Golubović, J., Gooskens, C. (2015). "Mutual intelligibility between West and South Slavic languages" [Article]. Russian Linguistics, 39(3), 351-373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11185-015-9150-9

- ^ Magocsi & Pop 2002, p. 274.

- ^ Tsvetkova, Svetoslava. "How Russian differs from other Slavic languages".

- ^ Kamusella 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Novotná & Blažek 2007, p. 185–210: ""Classical glottochronology" conducted by Czech Slavist M. Čejka in 1974 dates the Balto-Slavic split to −910±340 BCE, Sergei Starostin in 1994 dates it to 1210 BCE, and "recalibrated glottochronology" conducted by Novotná & Blažek dates it to 1400–1340 BCE. This agrees well with Trziniec-Komarov culture, localized from Silesia to Central Ukraine and dated to the period 1500–1200 BCE".

- ^ Kapović 2008, p. 94: "Kako rekosmo, nije sigurno je li uopće bilo prabaltijskoga jezika. Čini se da su dvije posvjedočene, preživjele grane baltijskoga, istočna i zapadna, različite jedna od druge izvorno kao i svaka posebno od praslavenskoga".

- ^ "New insights into the origin of the Indo-European languages".

- ^ Kassian & Dybo 2015.

- ^ Kushniarevich et al. 2015.

- ^ RSUH 2016.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Sedov 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Sedov 1979.

- ^ Barford 2001.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 500-700.

- ^ Heather 2010.

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 111: "…ростовско-суздальско-рязанская языковая зона от киевско-черниговской ничем существенным в древности не отличалась. Различия возникли позднее, они датируются сравнительно недавним, по лингвистическим меркам, временем, начиная с XIV–XV вв […the Rostov-Suzdal-Ryazan language area did not significantly differ from the Kiev-Chernigov one. Distinctions emerged later, in a relatively recent, by linguistic standards, time, starting from the 14th-15th centuries]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 88: "Северо-запад — это была территория Новгорода и Пскова, а остальная часть, которую можно назвать центральной, или центрально-восточной, или центрально-восточно-южной, включала одновременно территорию будущей Украины, значительную часть территории будущей Великороссии и территории Белоруссии … Существовал древненовгородский диалект в северо-западной части и некоторая более нам известная классическая форма древнерусского языка, объединявшая в равной степени Киев, Суздаль, Ростов, будущую Москву и территорию Белоруссии [The territory of Novgorod and Pskov was in the north-west, while the remaining part, which could either be called central, or central-eastern, or central-eastern-southern, comprised the territory of the future Ukraine, a substantial part of the future Great Russia, and the territory of Belarus … The Old Novgorodian dialect existed in the north-western part, while a somewhat more well-known classical variety of the Old Russian language united equally Kiev, Suzdal, Rostov, the future Moscow and the territory of Belarus]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 82: "…черты новгородского диалекта, отличавшие его от других диалектов Древней Руси, ярче всего выражены не в позднее время, когда, казалось бы, они могли уже постепенно развиться, а в самый древний период […features of the Novgorodian dialect, which made it different from the other dialects of the Old Rus', were most pronounced not in later times, when they seemingly could have evolved, but in the oldest period]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 92: "…северо-западная группа восточных славян представляет собой ветвь, которую следует считать отдельной уже на уровне праславянства […north-western group of the East Slavs is a branch that should be regarded as separate already in the Proto-Slavic period]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 94: "…великорусская территория оказалась состоящей из двух частей, примерно одинаковых по значимости: северо-западная (новгородско-псковская) и центрально-восточная (Ростов, Суздаль, Владимир, Москва, Рязань) […the Great Russian territory happened to include two parts of approximately equal importance: the north-western one (Novgorod-Pskov) and the central-eastern-southern one (Rostov, Suzdal, Vladimir, Moscow, Ryazan)]".

- ^ Zaliznyak 2012, section 94: "…нынешняя Украина и Белоруссия — наследники центрально-восточно-южной зоны восточного славянства, более сходной в языковом отношении с западным и южным славянством […today's Ukraine and Belarus are successors of the central-eastern-southern area of the East Slavs, more linguistically similar to the West and South Slavs]".

- ^ Dybo, Zamyatina & Nikolaev 1990.

- ^ Nimchuk 2001.

- ^ Shevelov 1979.

- ^ a b c Comrie & Corbett 2002, p. 6.

- ^ a b Skorvid 2015, p. 389, 396–397.

- ^ Schenker 2002, p. 82.

- ^ Nilsson 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Comrie & Corbett 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Hellquist 1922a.

- ^ Hellquist 1922b.

- ^ Hellquist 1922c.

- ^ Hellquist 1922d.

- ^ Hellquist 1922e.

- ^ Kallio 2006.

- ^ Mustajoki & Protassova 2014.

- ^ Teush, O. À. (2019). "Borrowed names of forest and forest loci in the Russian dialects of the European North of Russia: Lexemes of Baltic-Finnish origin" [Article]. Bulletin of Ugric Studies, 9(2), 297-317. https://doi.org/10.30624/2220-4156-2019-9-2-297-317

- ^ Teush, O. А. (2019). "Borrowed names of forest and forest loci in the Russian dialects of European North of Russia: Lexemes of Sami and Volga-Finnish origin" [Article]. Bulletin of Ugric Studies, 9(3), 485-498. https://doi.org/10.30624/2220-4156-2019-9-3-485-49

- ^ "Early Russia and East Slavs | Smart History of Russia".

- ^ Titz 1922.

- ^ Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Wörterbuchnetz 2023.

- ^ Dauzat 1938.

- ^ Pfeifer 2006.

- ^ Skok 1974.

- ^ Tokarev 1982.

- ^ Vasmer 1953.

- ^ Stachowski 2005.

- ^ Ethnologue 2022.

- ^ Dominikánská.

- ^ Bartoň 2018.

- ^ Steenbergen 2018, p. 52–54.

References

[edit]- Dulichenko, Aleksandr Dmitrievich (2005). "Malye slavyanskie literaturnye yazyki (mikroyazyki)" Малые славянские литературные языки (микроязыки) [Minor Slavic Literary Languages (Micro-Languages)]. In Moldovan, A. M.; et al. (eds.). Yazyki mira. Slavyanskie yazyki Языки мира. Славянские языки [Languages of the World. Slavic Languages] (in Russian). Moscow: Academia. pp. 595–615.

- Dulichenko, Aleksandr Dmitrievich (1981). Slavyanskie literaturnye mikroyazyki. Voprosy formirovania i razvitia Славянские литературные микроязыки. Вопросы формирования и развития [Slavic Literary Micro-Languages. The Questions of their Founding and Development] (in Russian). Tallinn: Valgus.

- Duličenko, A. D. (1994). "Kleinschriftsprachen in der slawischen Sprachenwelt" [Minor Languages in the Slavic Language World]. Zeitschrift für Slawistik (in German). 39 (4). doi:10.1524/slaw.1994.39.4.560. S2CID 170747896.

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich (16 March 2021). Ray, Michael; et al. (eds.). "Slavic languages". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Misachi, John (25 April 2017). "Slavic Countries". WorldAtlas.

- Barford, P.M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Trudgill, Peter (2003). A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 36, 95–96, 124–125.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2005). "The Triple Division of the Slavic Languages: A linguistic finding, a product of politics, or an accident?". IWM Working Papers. Vienna: Institute for Human Sciences. hdl:10023/12905. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Magocsi, Paul R.; Pop, Ivan Ivanovich (2002). Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 274.

- Novotná, Petra; Blažek, Václav (2007). "Glottochronology and its Application to the Balto-Slavic Languages" (PDF). Baltistica. XLII (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2008.

- Kapović, Mate (2008). Uvod u indoeuropsku lingvistiku [An Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics] (in Serbo-Croatian). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. ISBN 978-953-150-847-6.

- Kassian, Alexei; Dybo, Anna (2015). "Supplementary Information 2: Linguistics: Datasets; Methods; Results". PLOS ONE. 10 (9) e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- Kushniarevich, A; Utevska, O; Chuhryaeva, M; Agdzhoyan, A; Dibirova, K; Uktveryte, I; et al. (2015). "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data". PLOS ONE. 10 (9) e0135820. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035820K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135820. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4558026. PMID 26332464.

- "The Global Lexicostatistical Database". Russian State University for the Humanities, Moscow. 2016.

- Sussex, Roland; Cubberley, Paul (2006). The Slavic languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sedov, Valentin V. (1995). Slavyane v rannem srednevekov'ye Славяне в раннем средневековье [Slavs in the Early Middle Ages] (in Russian). Moscow: Fond Arheologii.

- Sedov, Valentin V. (1979). Proishozhdenie i rannyaya istoria slavyan Происхождение и ранняя история славян [The Origin and Early History of Slavs] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Curta, F. (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heather, P. (2010). Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zaliznyak, Andrey Anatolyevich (2012). "Ob istorii russkogo yazyka" Об истории русского языка [About Russian Language History]. Elementy (in Russian). Mumi-Troll School. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Dybo, V. A.; Zamyatina, G. I.; Nikolaev, S. L. (1990). Bulatova, R.V. (ed.). Osnovy slavyanskoy aktsentologii Основы славянской акцентологии [Fundamentals of Slavic Accentology] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 5-02-011011-6.

- Nimchuk, V. V. (2001). "9.1. Mova" 9.1. Мова [9.1. The Language]. In Smoliy, V. A. (ed.). Istoriia ukrains'koi kul'tury Історія української культури [A History of the Ukrainian Culture] (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Kyiv: Naukova Dumka. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Shevelov, George Yurii (1979). Istorychna fonolohiia ukrains'koi movy Історична фонологія української мови [A Historical Phonology of the Ukrainian Language] (in Ukrainian). Translated by Vakulenko, Serhiy; Danilenko, Andriy. Kharkiv: Acta (published 2000). Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Skorvid, Sergey (2015). Osipov, Yury (ed.). Slavyanskie yazyki Славянские языки [Slavic Languages] (in Russian). Vol. 30. Great Russian Encyclopedia. pp. 389, 396–397. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Schenker, Alexander M. (2002). "Proto-Slavonic". In Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville. G. (eds.). The Slavonic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 60–124. ISBN 0-415-28078-8.

- Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville. G. (2002). "Introduction". In Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville. G. (eds.). The Slavonic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 1–19. ISBN 0-415-28078-8.

- Nilsson, Morgan (8 November 2014). Vowel–Zero Alternations in West Slavic Prepositions. University of Gothenburg. hdl:2077/36304. ISBN 978-91-981198-3-1. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Hellquist, Elof (1922a). "torg". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- Hellquist, Elof (1922b). "humle". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- Hellquist, Elof (1922c). "räka". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- Hellquist, Elof (1922d). "tolk". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- Hellquist, Elof (1922e). "pråm". Svensk etymologisk ordbok (in Swedish) – via Project Runeberg.

- Kallio, Petri (2006). Nuorluoto, Juhani (ed.). On the Earliest Slavonic Loanwords in Finnic (PDF). Helsinki: Department of Slavonic and Baltic Languages and Literatures. ISBN 952-10-2852-1.

- Mustajoki, Arto; Protassova, Ekaterina (2014). "The Finnish-Russian Relationships: the Interplay of Economics, History, Psychology and Language". Russian Journal of Linguistics (4): 69–81.

- Titz, Karel (1922). "Naše řeč – Ohlasy husitského válečnictví v Evropě" [Our Speech – Echoes of Hussite Warfare in Europe]. Československý Vědecký ústav Vojenský (in Czech): 88. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Vodka". Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- "Vampyr" [Vampire]. Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm, digitalisierte Fassung im Wörterbuchnetz des Trier Center for Digital Humanities [The German Dictionary by Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm, Digitized Edition in Wörterbuchnetz of the Trier Center for Digital Humanities]. 01/23 (in German). Wörterbuchnetz. 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Dauzat, Albert (1938). Dictionnaire étymologique [Etymological Dictionary] (in French). Librairie Larousse.

- Pfeifer, Wolfgang (2006). Etymologisches Wörterbuch [Etymological Dictionary] (in German). p. 1494.

- Skok, Petar (1974). Etimologijski rjecnk hrvatskoga ili srpskoga jezika [Etymological dictionary of the Croatian or Serbian language] (in Serbo-Croatian).

- Tokarev, S. A. (1982). Mify narodov mira Мифы народов мира [Myths of the Peoples of the World] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Sovetskaya Entsiklopedia.

- Vasmer, Max (1953). Russisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch [Russian Etymological Dictionary] (in German). Carl Winter Universitätsverlag.

- Stachowski, Kamil (2005). "Wampir na rozdrożach. Etymologia wyrazu upiór – wampir w językach słowiańskich" [A vampire at the crossroads. The etymology of the word "upiór" - vampire in Slavic languages]. Rocznik Slawistyczny (in Polish). 55. Wrocław: 73–92.

- "Indo-European, Slavic". Language Family Trees. Ethnologue. 2022.

- "Rimskyj misal slověnskym jazykem". Dominikánská knihovna Olomouc.

- Bartoň, Josef (2018). "Miroslav Vepřek: Hlaholský misál Vojtěcha Tkadlčíka" [Miroslav Vepřek: Glagolitic missal by Vojtěch Tkadlčík]. AUC Theologica (in Czech). 7 (2). Olomouc: Nakladatelství Centra Aletti Refugium Velehrad-Roma: 173–178. doi:10.14712/23363398.2017.25.

- Steenbergen, Jan van (2018). Koutny, Ilona; Stria, Ida (eds.). "Język międzysłowiański jako lingua franca dla Europy Środkowej" [Interslavic Language as a Lingua Franca for the Central Europe] (PDF). Język. Komunikacja. Informacja (in Polish) (13). Poznań: Wydawnictwo Rys: 47–61. ISBN 978-83-65483-72-0. ISSN 1896-9585. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- "Ukraine: Treatment of Carpatho-Rusyns by authorities and society; state protection". Refworld. Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 29 January 2004. UKR42354.E. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

General references

[edit]- Lockwood, W.B. A Panorama of Indo-European Languages. Hutchinson University Library, 1972. ISBN 0-09-111020-3 hardback, ISBN 0-09-111021-1 paperback.

- Marko Jesensek, The Slovene Language in the Alpine and Pannonian Language Area, 2005. ISBN 83-242-0577-2

- Kalima, Jalo (April 1947). "Classifying Slavonic languages: Some remarks". The Slavonic and East European Review. 25 (65).

- Richards, Ronald O. (2003). The Pannonian Slavic Dialect of the Common Slavic Proto-language: The View from Old Hungarian. Los Angeles: University of California. ISBN 978-0-9742653-0-8.

External links

[edit]- Slavic dictionaries on Slavic Net Archived 17 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Slavistik-Portal The Slavistics Portal (Germany)

- Leo Wiener (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

Slavic languages

View on GrokipediaClassification

Major branches

The Slavic languages are conventionally classified into three primary branches—East, West, and South—based on shared phonological, morphological, and lexical innovations that emerged after the disintegration of Proto-Slavic around the 5th–6th centuries CE.[7] This tripartite division, while rooted in the Stammbaum model of linguistic genealogy, reflects a combination of genetic relationships and historical-geographic factors, with the branches forming dialect continua rather than strictly isolated groups.[8] The East Slavic branch comprises 3–4 languages, including Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian (with Rusyn sometimes counted separately), primarily spoken by approximately 190 million native speakers in Eastern Europe as of 2023.[9] The West Slavic branch includes 5–6 languages, such as Polish, Czech, Slovak, Upper Sorbian, Lower Sorbian, and Kashubian, concentrated in Central Europe with around 60 million native speakers as of 2023.[7] The South Slavic branch is the most diverse, encompassing 10 or more languages or standardized varieties (including dialects), such as Bulgarian, Macedonian, Slovene, and the Serbo-Croatian continuum (Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin), spoken by approximately 30 million native speakers in the Balkans as of 2023.[8] Branching criteria emphasize innovations distinguishing the groups from Proto-Slavic. Phonologically, West and South Slavic languages share the loss of nasal vowels (denasalized to *or and *er in West, *u and *ă in South), while East Slavic retained them longer before similar shifts; East Slavic features the shift of Proto-Slavic *g to /ɦ/ (h-like sound), as in Ukrainian голова [ɦoˈlowa] 'head' (e.g., Proto-Slavic *golva > Ukrainian голова).[7] Morphologically, all branches developed the perfective/imperfective verbal aspect system from Proto-Slavic prefixes, but West and South show earlier simplification of the dual number and case endings compared to East.[10] Lexical innovations, assessed via lexicostatistics, reveal branch-specific vocabulary, such as Germanic loans in West Slavic and Turkic/Balkan elements in South Slavic.[7] The approximate timelines for branch separations trace back to migrations and barriers in the early medieval period. The initial East-South split occurred around 500–700 CE, influenced by Avar incursions that divided eastern dialects, with the full divergence of West Slavic following in the 7th–9th centuries due to geographic isolation.[8] Geographically, East Slavic forms the core in Eastern Europe (Russia, Ukraine, Belarus), West Slavic in Central Europe (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Lusatia), and South Slavic in the Balkans (former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, North Macedonia).[10]Subdivisions and dialects

The East Slavic branch encompasses Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian, each featuring distinct dialectal subdivisions that reflect historical migrations and regional variations. Russian's standard form is primarily derived from the Central dialect group, which bridges Northern dialects (characterized by features like tsokanye, where the affricate /tɕ/ is realized as /ts/) and Southern dialects (noted for their preservation of full vowels in unstressed positions, unlike the akanye reduction in the north).[11] Ukrainian dialects are broadly divided into Northern, Southeastern, and Southwestern groups, with the Carpathian subdialects—such as Hutsul, Boiko, and Lemko—exhibiting archaic East Slavic traits like some retention of nasalized vowels in specific contexts and unique lexical borrowings from Romance languages due to historical contacts in the highlands.[12] Belarusian is split into Northern (or Northeastern) and Southern (or Southwestern) variants, where the Northern dialects show stronger Russian influences in phonology, such as mixed tsokanye and akanye, while Southern dialects align more closely with Ukrainian in retaining soft consonants and vowel reductions.[13] Within the West Slavic branch, the Lechitic subgroup includes Polish and its close relative Kashubian, the latter often classified as a separate language due to phonological shifts like the depalatalization of *tj to /ts/ and retention of nasal vowels, though it forms a dialect continuum with northern Polish varieties.[14] The Sorbian languages divide into Upper Sorbian (spoken in Saxony, with features like pitch accent and closer ties to Czech phonology) and Lower Sorbian (in Brandenburg, exhibiting Polish-like consonant softening and vowel harmony), both endangered but standardized separately since the 16th century.[15] The Czech-Slovak continuum represents a mutual intelligibility zone, where eastern Czech dialects blend seamlessly into western Slovak ones through shared prosodic features and lexical overlap, historically reinforced by the 1918 union of Czechoslovakia despite political separation fostering distinct standards.[16] South Slavic subdivisions highlight a western-eastern split, with the Western group comprising Slovene and the Serbo-Croatian dialect cluster (encompassing Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian standards, unified by Shtokavian basis but differentiated by script and lexical purism).[17] The Eastern group includes Macedonian and Bulgarian, where Torlak dialects serve as a transitional zone to Serbian, featuring analytic case marking and loss of infinitive similar to Balkan sprachbund traits.[18] Dialect continua illustrate the fluid boundaries across branches, such as the extinct Polabian language, a Lechitic variety that linked West Slavic with early East Slavic through shared nasal consonants and vocabulary until its assimilation by German in the 18th century.[19] In South Slavic, Chakavian and Kajkavian dialects represent transitional zones between Slovene and the Shtokavian core, preserving dual number and pitch accent while bridging western prosody with central morphology.[10] Subdivisions in Slavic languages have been shaped by migrations (such as 6th-7th century Slavic expansions leading to dialect divergence), political borders (e.g., post-WWII partitions reinforcing national standards), and 19th-century standardization efforts during national revivals, where intellectuals like Vuk Karadžić for Serbo-Croatian and Josef Jungmann for Czech promoted dialect-based norms to foster ethnic unity.[20][21] Debated statuses include Rusyn, often viewed as an East Slavic language closely related to Ukrainian but considered separate by some due to its Carpathian-specific features like preserved yat reflexes and distinct literary tradition since the 1990s.[8] Montenegrin is typically regarded as a variant within the Serbo-Croatian cluster, standardized in 2007 with unique letters like <ś> but sharing 95% lexical overlap with Serbian, amid ongoing disputes over its autonomy.[22]Historical development

Proto-Slavic origins

Proto-Slavic, the reconstructed common ancestor of all Slavic languages, emerged from Proto-Balto-Slavic between approximately 1000 BCE and the early centuries CE and was spoken until approximately 900 CE in a homeland spanning the regions of modern-day Poland, Ukraine, and western Russia.[23] This timeframe marks the period of relative linguistic unity before the major dialectal divergences that led to the East, West, and South Slavic branches.[24] The language developed in the context of early Slavic migrations and settlements following the Migration Period, with its speakers occupying marshy and forested areas along the middle Dnieper River and extending westward.[25] As part of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European family, Proto-Slavic shared key innovations with Proto-Baltic, including satemization, a phonological shift in which Proto-Indo-European palatovelar consonants (*ḱ, *ǵ, *ǵʰ) evolved into sibilants (e.g., *ḱ > *ś > *s in many contexts), distinguishing Balto-Slavic from centum branches like Germanic and Italic.[26] This satem development, along with other shared features such as the retention of certain Indo-European vowel distinctions and accentual patterns, underscores the close genetic relationship between Baltic and Slavic languages within Indo-European.[26] Proto-Balto-Slavic itself likely dates to 1000–500 BCE, with the divergence into Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic occurring gradually amid cultural and migratory shifts in Eastern Europe. The later Common Slavic period of linguistic unity is dated to roughly the 5th–9th centuries CE.[23] The phonological system of Proto-Slavic featured an inventory of approximately 25 consonants, including stops (*p, *b, *t, *d, *k, *g), fricatives (*s, *z, *š, *ž, *x), nasals (*m, *n), liquids (*l, *r), and approximants (*j, *w), with palatalization emerging as a key contrastive feature in later stages.[23] Vowels consisted of five basic short qualities (*a, *e, *i, *o, *u) and their long counterparts (*ā, *ē, *ī, *ō, *ū), alongside reduced vowels *ь and *ъ representing jer sounds.[23] The prosodic system included a mobile accent that could shift across syllables within paradigms, characterized by pitch or stress with an "acute" intonation on long vowels, diphthongs, or syllabic resonants, but without initial tonal distinctions.[23] Morphologically, Proto-Slavic was a highly synthetic, fusional language with rich inflectional paradigms, including seven cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, instrumental, locative, vocative) that encoded grammatical relations.[27] Nouns, adjectives, and pronouns distinguished three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter) and three numbers (singular, dual, plural), reflecting a conservative inheritance from Indo-European via Balto-Slavic.[28] The dual number, used for pairs of entities, was fully productive across declensions and conjugations, as evidenced by comparative analysis of early Slavic texts and modern remnants in languages like Slovenian.[29] Verbal morphology included tenses such as present, aorist, and imperfect, with aspects beginning to develop, all marked for person, number, and mood in a predominantly synthetic framework.[23] The core vocabulary of Proto-Slavic derived from Indo-European roots, exemplified by *gordъ 'enclosure, fortified settlement, town', which traces back to Proto-Indo-European *gʰerdʰ- 'to enclose' and reflects basic societal concepts.[30] Early loans from neighboring languages enriched the lexicon, including Germanic borrowings like *xъlmъ 'helmet' from Proto-Germanic *helmaz, indicating contacts during the Migration Period with tribes such as the Goths.[31] These integrations highlight Proto-Slavic's role as a dynamic system absorbing terms for material culture and warfare. Proto-Slavic is associated with the culture of early Slavic tribes, such as the Antes and Sclaveni, who inhabited Eastern Europe in the pre-Christian era before widespread Christianization in the 9th–10th centuries CE.[32] Lacking direct written records from this period, its features have been reconstructed primarily through the comparative method, analyzing correspondences across daughter languages, ancient texts like Old Church Slavonic, and Indo-European cognates, supplemented by internal reconstruction of sound changes.[23] This approach reveals a society of decentralized tribal communities engaged in agriculture, trade, and intermittent warfare, with linguistic unity fostering ethnic cohesion until the onset of branch divergences around 900 CE.[24]Divergence into branches

The unity of Common Slavic persisted until approximately the 6th–7th centuries CE, when large-scale migrations across Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe initiated the process of dialectal fragmentation. These migrations, driven by climatic events such as the Late Antique Little Ice Age (536–660 CE) and the Justinianic Plague (541–750 CE), dispersed Slavic speakers from their core habitat between the upper Vistula and Dnieper rivers, leading to geographic isolation and the emergence of distinct branches. By the 9th–10th centuries, transitional dialects had developed, with the East-West split solidifying around the 11th century as Western groups settled in areas of Germanic influence and Eastern groups interacted with Finno-Ugric and Turkic populations; the South Slavic branch became further isolated in the Balkans following Avar-led expansions.[20][33] Key phonological divergences arose through successive waves of palatalization, which differentiated the branches after the monophthongization of diphthongs like *ai and *ei. The progressive palatalization, occurring before the delabialization of *u and *ü, affected sequences such as *tj, yielding ć in West Slavic (e.g., *moťi > Polish móc [muts]), č in East and South Slavic (e.g., *moťi > Russian мочь [motɕ], Serbo-Croatian moći [moːtɕi]); these variations reflect regional phonetic conditioning and contributed to early branch markers by the 10th century. Additional shifts, including the pleophony of *or and *ol in West and South but not East Slavic, further accentuated separations.[34][33] Morphological innovations also marked the splits, with the South Slavic branch showing distinct developments in verbal categories. The dual number, inherited from Proto-Slavic, was lost early in Eastern South Slavic (e.g., Bulgarian and Macedonian), replaced by plural forms, while it persisted longer in West and East Slavic before partial retention only in Slovene and Upper Sorbian; this loss facilitated analytical constructions in the south. The aorist tense was retained and developed in South Slavic (e.g., as a simple past in Bulgarian), whereas East and West Slavic languages eliminated it by the medieval period, relying instead on perfective forms derived from the old perfect. Future tense formations diverged similarly: South Slavic often employs a subjunctive particle like da + present (e.g., Bulgarian ще да отида), contrasting with the use of perfective present in East and West Slavic (e.g., Russian пойду).[35][36] External contacts accelerated these changes, with West Slavic exposed to Germanic substrates via migrations into former Roman and Germanic territories, introducing loanwords like Old High German *kuningaz > Proto-Slavic *kŭnędzĭ 'prince'; South Slavic encountered Greek and Balkan influences through Byzantine interactions, evident in toponyms and borrowings; and East Slavic incorporated Finnic and Turkic elements, such as substrate terms in phonology. Evidence for these early divergences comes from 9th-century Old Church Slavonic texts, which preserve a transitional South Slavic form with features bridging East and South, like nasal vowels (ę > South męso 'meat' vs. West maso); loanwords and toponyms, such as 6th-century Slavic place names in Greece, further attest to migration paths and contacts. Intermediate dialects, including early Old Russian, exhibit South Slavic traits like aorist retention, illustrating ongoing East-South bridging before full separation.[33][20]Medieval to modern evolution

During the medieval period from the 9th to 15th centuries, Old Church Slavonic served as the primary literary koine across Slavic-speaking regions, functioning as a standardized ecclesiastical and cultural language based on the South Slavic dialects of the Thessalonica area and used for religious texts, administration, and early literature.[33] This lingua franca facilitated the spread of Christianity among the Slavs following the missionary work of Cyril and Methodius in the late 9th century, but it coexisted with emerging regional vernaculars that reflected local phonetic and lexical variations.[33] For instance, in the East Slavic territories of Kievan Rus', Old East Slavic began to develop from the 10th century onward, as evidenced in the earliest documents like the Primary Chronicle, marking the divergence from Old Church Slavonic toward a distinct vernacular used in secular and legal contexts.[37] In the Renaissance and Reformation eras of the 15th to 18th centuries, the advent of printing presses accelerated the dissemination of Slavic texts and spurred vernacular standardization efforts, particularly through Bible translations that promoted literacy in national languages. A prominent example is the Czech Kralice Bible, translated between 1579 and 1593 by the Unity of the Brethren, which became a cornerstone for the standardization of the Czech language and influenced Protestant literary traditions in Central Europe.[38] In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Polish emerged as the dominant chancery language for official documents and diplomacy during this period, reflecting its role in unifying diverse territories and elevating its status over Latin and Ruthenian.[39] The 19th century witnessed national awakenings across Slavic regions, where philological reforms intertwined with romantic nationalism to codify and purify languages as symbols of ethnic identity. Vuk Stefanović Karadžić's 1814 reforms for Serbo-Croatian, which advocated for a phonemic orthography based on the Štokavian dialect, revolutionized South Slavic linguistics by rejecting archaic Church Slavonic elements in favor of spoken vernaculars, thereby fostering a unified literary standard.[40] Parallel purism movements, such as those in Czech and Slovak contexts, sought to eliminate German loanwords and revive native roots, aligning language policy with political aspirations for autonomy amid Habsburg and Ottoman rule.[41] In the 20th century, standardization processes were heavily shaped by geopolitical shifts, including Soviet policies that promoted Russian as a lingua franca, leading to Russification in Ukraine, Belarus, and other East Slavic areas through education and media, which suppressed local variants and accelerated dialect leveling. Post-World War II, newly independent or reconfigured states codified languages like Macedonian in 1945, drawing on central dialects to establish an official standard distinct from Bulgarian and Serbian, supported by the Yugoslav government's multilingual framework. European Union integration since the 1990s has influenced Slavic orthographies in member states, such as harmonizing spelling reforms in Polish and Czech to align with digital and international norms while preserving linguistic heritage.[42] Contemporary Slavic languages face challenges from globalization, including English dominance in media and commerce, which threatens smaller varieties, yet efforts at minority revivals persist, as seen in the Sorbian languages of Germany, where community programs and bilingual education have stabilized speaker numbers since the 1990s. As of 2025, EU-funded initiatives continue to support minority Slavic languages through digital archiving and education programs. Digital corpora, such as the Prague Dependency Treebank for multiple Slavic languages, enable advanced reconstruction and comparative studies, aiding preservation amid urbanization. Notable extinctions include Polabian, a West Slavic language that died out in the mid-18th century due to German assimilation in the Elbe River region, with its last fluent speaker recorded in 1756.[43]Phonology

Consonants

The reconstructed Proto-Slavic consonant inventory is estimated to have included approximately 25 consonants, encompassing stops, fricatives, affricates, nasals, liquids, and glides, with distinctions in five places of articulation (labial, dental/alveolar, postalveolar, palatal, and velar) and a voicing contrast for obstruents and affricates.[44] Key elements included palatal consonants such as *j (glide) and sibilants like *s, *z (alveolar), *š, *ž (postalveolar fricatives), and affricates *č [t͡ʃ], *dž [d͡ʒ].[23] This system laid the foundation for the rich consonantal complexity observed in modern Slavic languages, where inventories typically range from 20 to 35 phonemes due to subsequent developments in palatalization and affrication.[45] A hallmark of Slavic consonant systems is palatalization, which creates contrastive soft/hard pairs in many languages, particularly in East and West Slavic branches; for example, Russian distinguishes /t/ (hard) from /tʲ/ (soft, palatalized) in words like tot 'that one' versus tʲotʲa 'aunt'.[44] Fricative clusters are also common, such as št (e.g., Proto-Slavic kušti > Russian kuštʲ 'bush') and zd (e.g., gvozdi > Russian gvozʲdʲ 'nails'), often preserved or adapted across branches to maintain syllable structure.[23] These features contribute to the languages' phonological density, with obstruents showing progressive or regressive assimilation in voicing and place. Major sound changes shaping consonants include the first palatalization, a progressive shift where velars softened before front vowels (e.g., Proto-Slavic *kēsъ > Russian čas [tɕas] 'hour/time'), and later regressive palatalizations affecting dentals and labials before yers or front vowels (e.g., t > tʲ or č in Russian nočʲ 'night' from noktь).[23] The loss of yers (ultrashort vowels *ĭ, ŭ) during the Common Slavic period led to consonant cluster formation or simplification, as in Russian denʲ 'day' (nominative singular) versus dnʲi 'days' (nominative plural), where yer deletion creates /dnʲ/ without vocalization altering the consonants directly but affecting their adjacency. Some West Slavic languages, like Czech, feature syllabic sonorants (r̥, l̥) as realizations of such clusters from yer deletion.[45] Branch-specific developments highlight divergences: in South Slavic languages like Serbo-Croatian, mergers of hissing and hushing sibilants occurred, eliminating distinctions such as between č [t͡ʃ] and palatalized ć [t͡ɕ], resulting in a unified /t͡ʃ/ without contrastive secondary palatalization (e.g., čovjek 'man').[44] West Slavic languages, such as Polish, simplified affricates in some contexts while retaining complex sibilants, with /cz/ [t͡ʂ] and /dz/ [d͡z] from Proto-Slavic *tʲ and dʲ (e.g., Polish czas 'time' from časъ), and feature regressive voicing assimilation (e.g., final devoicing in pies [pʲɛs] 'dog').[45] East Slavic, exemplified by Russian, preserved extensive secondary palatalization and added retroflex sounds like /ʂ/, expanding the inventory.[45] Allophonic variations further enrich these systems, including voicing assimilation, which is regressive and progressive; in Russian, obščij 'common' surfaces as [opɕːoj], with /b/ devoicing before voiceless /š/ and /šč/ geminating slightly.[45] Gemination appears in some dialects and loanwords, as in Russian dialects where clusters like /ttʲ/ occur (e.g., [pədˈtarkə] 'gift' from yer loss), though it is not phonemic in standard varieties.[44] Final devoicing is widespread except in Serbo-Croatian (e.g., Russian grod 'city' > [ɡrot]).| Language/Branch | Total Consonants | Palatalized Consonants | Key Distinctive Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Russian (East) | 34 | 18 | Secondary palatalization; retroflexes (/ʂ, /ʐ/); voicing assimilation in clusters.[45] |

| Polish (West) | 35 | 17 | Primary and secondary palatalization; affricates (/t͡ʂ, d͡z/); regressive devoicing.[45] |

| Czech (West) | 25 | 0 (primary only) | No contrastive secondary palatalization; morpheme-specific softening; yer-induced clusters; syllabic r̥, l̥.[45] |

| Serbo-Croatian (South) | 25 | 0 | Merged sibilants (/t͡ʃ/ without ć); no final devoicing; limited palatalization.[45] |

| Bulgarian (South) | 37 | 18 | Secondary palatalization; no retroflexes; vowel epenthesis in clusters.[45] |

Vowels