Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

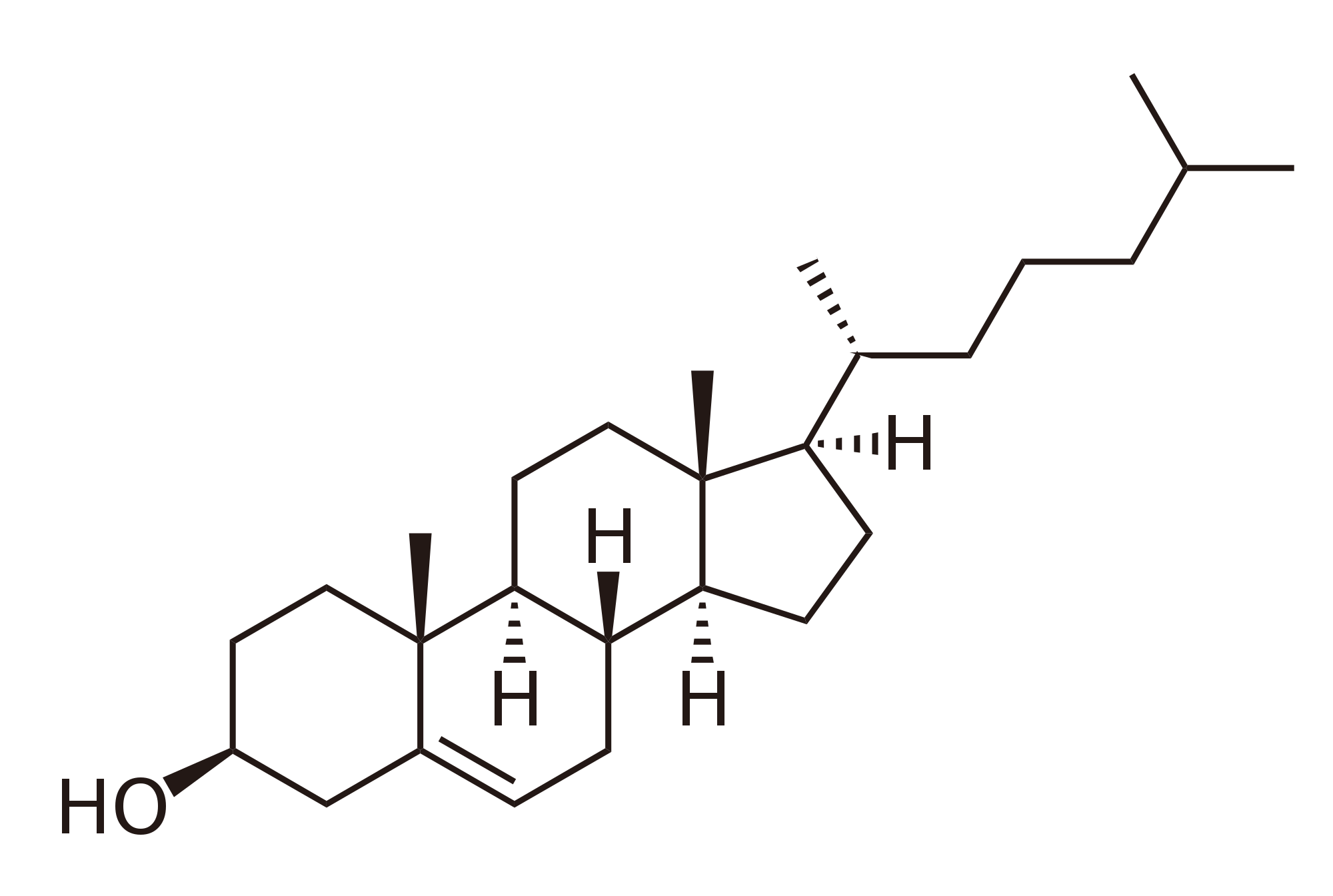

Cholesterol

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Cholest-5-en-3β-ol

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1R,3aS,3bS,7S,9aR,9bS,11aR)-9a,11a-Dimethyl-1-[(2R)-6-methylheptan-2-yl]-2,3,3a,3b,4,6,7,8,9,9a,9b,10,11,11a-tetradecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthren-7-ol | |

| Other names

Cholesterin, Cholesteryl alcohol[1]

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.321 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H46O | |

| Molar mass | 386.65 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder[2] |

| Density | 1.052 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 148 to 150 °C (298 to 302 °F; 421 to 423 K)[2] |

| Boiling point | 360 °C (680 °F; 633 K) (decomposes) |

| 0.095 mg/L (30 °C)[1] | |

| Solubility | soluble in acetone, benzene, chloroform, ethanol, ether, hexane, isopropyl myristate, methanol |

| −284.2·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 209.3 ±12.4 °C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all animals, distributed in body tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in animal fats and oils.[3][4]

Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells[5] and is an essential structural and signaling component of animal cell membranes. In vertebrates, hepatic cells typically produce the greatest amounts. In the brain, astrocytes produce cholesterol and transport it to neurons.[6] It is absent among prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), although there are some exceptions, such as Mycoplasma, which require cholesterol for growth.[7] Cholesterol also serves as a precursor for the biosynthesis of steroid hormones, bile acid,[8] and vitamin D.

Elevated levels of cholesterol in the blood, especially when bound to low-density lipoprotein (LDL, often referred to as "bad cholesterol"), may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.[9]

François Poulletier de la Salle first identified cholesterol in solid form in gallstones in 1769. In 1815, chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul named the compound "cholesterine".[10][11]

Etymology

[edit]The word cholesterol comes from Ancient Greek chole- 'bile' and stereos 'solid', followed by the chemical suffix -ol for an alcohol.

Physiology

[edit]Cholesterol is essential for all animal life. While most cells are capable of synthesizing it, the majority of cholesterol is ingested or synthesized by hepatocytes and transported in the blood to peripheral cells. The levels of cholesterol in peripheral tissues are dictated by a balance of uptake and export.[12] Under normal conditions, brain cholesterol is separate from peripheral cholesterol, i.e., the dietary and hepatic cholesterol do not cross the blood brain barrier. Rather, astrocytes produce and distribute cholesterol in the brain.[13]

De novo synthesis, both in astrocytes and hepatocytes, occurs by a complex 37-step process. This begins with the mevalonate or HMG-CoA reductase pathway, the target of statin drugs, which encompasses the first 18 steps. This is followed by 19 additional steps to convert the resulting lanosterol into cholesterol.[14] A human male weighing 68 kg (150 lb) normally synthesizes about 1 gram (1,000 mg) of cholesterol per day, and his body contains about 35 g, mostly contained within the cell membranes.[citation needed]

Typical daily cholesterol dietary intake for a man in the United States is 307 mg.[15] Most ingested cholesterol is esterified, which causes it to be poorly absorbed by the gut. The body also compensates for absorption of ingested cholesterol by reducing its own cholesterol synthesis.[16] For these reasons, cholesterol in food, seven to ten hours after ingestion, has little, if any effect on concentrations of cholesterol in the blood. Conversely, in rats, blood cholesterol is inversely correlated with cholesterol consumption: the more cholesterol a rat eats the lower the blood cholesterol.[17] During the first seven hours after ingestion of cholesterol, as absorbed fats are being distributed around the body within extracellular water by the various lipoproteins (which transport all fats in the water outside cells), the concentrations increase.[18]

Plants make cholesterol in very small amounts.[19] In larger quantities they produce phytosterols, chemically similar substances that compete with cholesterol for reabsorption in the intestinal tract, thus potentially reducing cholesterol reabsorption.[20] When intestinal lining cells absorb phytosterols, in place of cholesterol, they usually excrete the phytosterol molecules back into the GI tract, an important protective mechanism. The intake of naturally occurring phytosterols, which encompass plant sterols and stanols, ranges between ≈200–300 mg/day depending on eating habits.[21] Specially designed vegetarian experimental diets have been produced yielding upwards of 700 mg/day.[22]

Function

[edit]Membranes

[edit]Cholesterol is present in varying degrees in all animal cell membranes but is absent in prokaryotes.[23] It is required to build and maintain membranes and modulates membrane fluidity over the range of physiological temperatures. The hydroxyl group of each cholesterol molecule interacts with water molecules surrounding the membrane, as do the polar heads of the membrane phospholipids and sphingolipids, while the bulky steroid and the hydrocarbon chain are embedded in the membrane, alongside the nonpolar fatty-acid chain of the other lipids. Through the interaction with the phospholipid fatty-acid chains, cholesterol increases membrane packing, which both alters membrane fluidity[24] and maintains membrane integrity so that animal cells do not need to build cell walls (like plants and most bacteria). The membrane remains stable and durable without being rigid, allowing animal cells to change shape and animals to move.[citation needed]

The structure of the tetracyclic ring of cholesterol contributes to the fluidity of the cell membrane, as the molecule is in a trans conformation, making all but the side chain of cholesterol rigid and planar.[25] In this structural role, cholesterol also reduces the permeability of the plasma membrane to neutral solutes,[26] hydrogen ions, and sodium ions.[27]

Substrate presentation

[edit]Cholesterol regulates the biological process of substrate presentation and the enzymes that use substrate presentation as a mechanism of their activation. Phospholipase D2 (PLD2) is a well-defined example of an enzyme activated by substrate presentation.[28] The enzyme is palmitoylated causing the enzyme to traffic to cholesterol dependent lipid domains sometimes called "lipid rafts". The substrate of phospholipase D is phosphatidylcholine (PC) which is unsaturated and is of low abundance in lipid rafts. PC localizes to the disordered region of the cell along with the polyunsaturated lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). PLD2 has a PIP2 binding domain. When PIP2 concentration in the membrane increases, PLD2 leaves the cholesterol-dependent domains and binds to PIP2 where it then gains access to its substrate PC and commences catalysis based on substrate presentation.[citation needed]

Signaling

[edit]Cholesterol is implicated in cell signaling processes, assisting in the formation of lipid rafts in the plasma membrane, which brings receptor proteins in close proximity with high concentrations of second messenger molecules.[29] In multiple layers, cholesterol and phospholipids (both electrical insulators) can facilitate speed of transmission of electrical impulses along nerve tissue. For many neuron fibers, a myelin sheath, rich in cholesterol since it is derived from compacted layers of Schwann cell or oligodendrocyte membranes, provides insulation for more efficient conduction of impulses.[30]Demyelination (loss of myelin) is believed to be part of the basis for multiple sclerosis.[31]

Cholesterol binds to and affects the gating of a number of ion channels such as the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, GABAA receptor, and the inward-rectifier potassium channel.[32] Cholesterol activates the estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα) and may be the endogenous ligand for the receptor.[33][34] The constitutively active nature of the receptor may be explained by the fact that cholesterol is ubiquitous in the body.[34] Inhibition of ERRα signaling by reduction of cholesterol production has been identified as a key mediator of the effects of statins and bisphosphonates on bone, muscle, and macrophages.[33][34] On the basis of these findings, it has been suggested that the ERRα should be de-orphanized and classified as a receptor for cholesterol.[33][34]

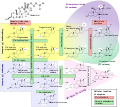

As a chemical precursor

[edit]Within cells, cholesterol is a precursor molecule for several biochemical pathways. For example, it is the precursor molecule for the synthesis of vitamin D in the calcium metabolism and all steroid hormones, including the adrenal gland hormones cortisol and aldosterone, as well as the sex hormones progesterone, estrogens, and testosterone, and their derivatives.[8][35]

Epidermis

[edit]The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis.[36][37] It is composed of terminally differentiated and enucleated corneocytes that reside within a lipid matrix, like "bricks and mortar."[36][37] Together with ceramides and free fatty acids, cholesterol forms the lipid mortar, a water-impermeable barrier that prevents evaporative water loss. As a rule of thumb, the epidermal lipid matrix is composed of an equimolar mixture of ceramides (≈50% by weight), cholesterol (≈25% by weight), and free fatty acids (≈15% by weight), with smaller quantities of other lipids also present.[36][37] Cholesterol sulfate reaches its highest concentration in the granular layer of the epidermis. Steroid sulfate sulfatase then decreases its concentration in the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the epidermis.[38] The relative abundance of cholesterol sulfate in the epidermis varies across different body sites with the heel of the foot having the lowest concentration.[37]

Metabolism

[edit]Cholesterol is recycled in the body. The liver excretes cholesterol into biliary fluids, which are then stored in the gallbladder from where they are excreted in a non-esterified form (via bile) into the digestive tract. Typically, about 50% of the excreted cholesterol is reabsorbed by the small intestine back into the bloodstream.[39]

Biosynthesis and regulation

[edit]Biosynthesis

[edit]Almost all animal tissues synthesize cholesterol from acetyl-CoA. All animal cells (with some exceptions within the invertebrates) manufacture cholesterol, for both membrane structure and other uses, with relative production rates varying by cell type and organ function. About 80% of total daily cholesterol production occurs in the liver and the intestines;[40] other sites of higher synthesis rates include the brain, the adrenal glands, and the reproductive organs.

Synthesis within the body starts with the mevalonate pathway where two molecules of acetyl-CoA condense to form acetoacetyl-CoA. This is followed by a second condensation between acetyl-CoA and acetoacetyl-CoA to form 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA).[41]

This molecule is then reduced to mevalonate by the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. Production of mevalonate is the rate-limiting and irreversible step in cholesterol synthesis and is the site of action for statins (a class of cholesterol-lowering drugs).[citation needed]

Mevalonate is finally converted to isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) through two phosphorylation steps and one decarboxylation step that requires ATP.

Three molecules of isopentenyl pyrophosphate condense to form farnesyl pyrophosphate through the action of geranyl transferase.

Two molecules of farnesyl pyrophosphate then condense to form squalene by the action of squalene synthase in the endoplasmic reticulum.[41]

Oxidosqualene cyclase then cyclizes squalene to form lanosterol.

Finally, lanosterol is converted to cholesterol via either of two pathways, the Bloch pathway, or the Kandutsch-Russell pathway.[42][43][44][45][46] The final 19 steps to cholesterol contain NADPH and oxygen to help oxidize methyl groups for the removal of carbons, mutases to move alkene groups, and NADH to help reduce ketones.

Konrad Bloch and Feodor Lynen shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1964 for their discoveries concerning some of the mechanisms and methods of regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism.[47]

Regulation of cholesterol synthesis

[edit]Biosynthesis of cholesterol is directly regulated by the cholesterol levels present, though the homeostatic mechanisms involved are only partly understood. A higher intake of food leads to a net decrease in endogenous production, whereas a lower intake of food has the opposite effect. The main regulatory mechanism is the sensing of intracellular cholesterol in the endoplasmic reticulum by the protein SREBP (sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and 2).[48] In the presence of cholesterol, SREBP is bound to two other proteins: SCAP (SREBP cleavage-activating protein) and INSIG-1. When cholesterol levels fall, INSIG-1 dissociates from the SREBP-SCAP complex, which allows the complex to migrate to the Golgi apparatus. Here SREBP is cleaved by S1P and S2P (site-1 protease and site-2 protease), two enzymes that are activated by SCAP when cholesterol levels are low.[citation needed]

The cleaved SREBP then migrates to the nucleus and acts as a transcription factor to bind to the sterol regulatory element (SRE), which stimulates the transcription of many genes. Among these are the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor and HMG-CoA reductase. The LDL receptor scavenges circulating LDL from the bloodstream, whereas HMG-CoA reductase leads to an increase in endogenous production of cholesterol.[49] A large part of this signaling pathway was clarified by Dr. Michael S. Brown and Dr. Joseph L. Goldstein in the 1970s. In 1985, they received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work. Their subsequent work shows how the SREBP pathway regulates the expression of many genes that control lipid formation and metabolism and body fuel allocation.[citation needed]

Cholesterol synthesis can be turned off when cholesterol levels are high. HMG-CoA reductase contains both a cytosolic domain (responsible for its catalytic function) and a membrane domain which senses signals for its degradation. Increasing concentrations of cholesterol (and other sterols) cause a change in this domain's oligomerization state, making it more susceptible to destruction by the proteasome. This enzyme's activity can also be reduced by phosphorylation by an AMP-activated protein kinase. Because this kinase is activated by AMP, which is produced when ATP is hydrolyzed, it follows that cholesterol synthesis is halted when ATP levels are low.[50]

Plasma transport and regulation of absorption

[edit]

As an isolated molecule, cholesterol is only minimally soluble in water, or hydrophilic. Because of this, it dissolves in blood at exceedingly small concentrations. To be transported effectively, cholesterol is instead packaged within lipoproteins, complex discoidal particles with exterior amphiphilic proteins and lipids, whose outward-facing surfaces are water-soluble and inward-facing surfaces are lipid-soluble. This allows it to travel through the blood via emulsification. Unbound cholesterol, being amphipathic, is transported in the monolayer surface of the lipoprotein particle along with phospholipids and proteins. Cholesterol esters bound to fatty acid, on the other hand, are transported within the fatty hydrophobic core of the lipoprotein, along with triglyceride.[51]

There are several types of lipoproteins in the blood. In order of increasing density, they are chylomicrons, very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Lower protein/lipid ratios make for less dense lipoproteins. Cholesterol within different lipoproteins is identical, although some are carried as their native "free" alcohol form (the cholesterol-OH group facing the water surrounding the particles), while others as fatty acyl esters (known also as cholesterol esters) within the particles.[51]

Lipoprotein particles are organized by complex apolipoproteins, typically between 80 and 100 different proteins per particle, which can be recognized and bound by specific receptors on cell membranes, directing their lipid payload into specific cells and tissues currently ingesting these fat transport particles. These surface receptors serve as unique molecular signatures, which then help determine fat distribution delivery throughout the body.[51]

Chylomicrons, the least dense cholesterol transport particles, contain apolipoprotein B-48, apolipoprotein C, and apolipoprotein E (the principal cholesterol carrier in the brain)[52] in their shells. Chylomicrons carry fats from the intestine to muscle and other tissues in need of fatty acids for energy or fat production. Unused cholesterol remains in more cholesterol-rich chylomicron remnants and is taken up from here to the bloodstream by the liver.[51]

VLDL particles are produced by the liver from triacylglycerol and cholesterol not used in the synthesis of bile acids. These particles contain apolipoprotein B100 and apolipoprotein E in their shells and can be degraded by lipoprotein lipase on the artery wall to IDL. This arterial wall cleavage allows absorption of triacylglycerol and increases the concentration of circulating cholesterol. IDL particles are then consumed in two processes: half is metabolized by HTGL and taken up by the LDL receptor on the liver cell surfaces, while the other half continues to lose triacylglycerols in the bloodstream until they become cholesterol-laden LDL particles.[51]

LDL particles are the major blood cholesterol carriers. Each one contains approximately 1,500 molecules of cholesterol ester. LDL particle shells contain just one molecule of apolipoprotein B100, recognized by LDL receptors in peripheral tissues. Upon binding of apolipoprotein B100, many LDL receptors concentrate in clathrin-coated pits. Both LDL and its receptor form vesicles within a cell via endocytosis. These vesicles then fuse with a lysosome, where the lysosomal acid lipase enzyme hydrolyzes the cholesterol esters. The cholesterol can then be used for membrane biosynthesis or esterified and stored within the cell, so as to not interfere with the cell membranes.[51]

LDL receptors are used up during cholesterol absorption, and its synthesis is regulated by SREBP, the same protein that controls the synthesis of cholesterol de novo, according to its presence inside the cell. A cell with abundant cholesterol will have its LDL receptor synthesis blocked, to prevent new cholesterol in LDL particles from being taken up. Conversely, LDL receptor synthesis proceeds when a cell is deficient in cholesterol.[51]

When this process becomes unregulated, LDL particles without receptors begin to appear in the blood. These LDL particles are oxidized and taken up by macrophages, which become engorged and form foam cells. These foam cells often become trapped in the walls of blood vessels and contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation. Differences in cholesterol homeostasis affect the development of early atherosclerosis (carotid intima-media thickness).[53] These plaques are the main causes of heart attacks, strokes, and other serious medical problems, leading to the association of so-called LDL cholesterol (actually a lipoprotein) with the term "bad" cholesterol.[50]

HDL particles are thought to transport cholesterol back to the liver, either for excretion or for other tissues that synthesize hormones, in a process known as reverse cholesterol transport (RCT).[54] Large numbers of HDL particles correlates with better health outcomes,[55] whereas low numbers of HDL particles is associated with atheromatous disease progression in the arteries.[56]

Metabolism, recycling and excretion

[edit]Cholesterol is susceptible to oxidation and easily forms oxygenated derivatives called oxysterols. These can be formed by three different mechanisms: autoxidation, secondary oxidation to lipid peroxidation, and cholesterol-metabolizing enzyme oxidation. A great interest in oxysterols arose when they were shown to exert inhibitory actions on cholesterol biosynthesis.[57] This finding became known as the "oxysterol hypothesis". Additional roles for oxysterols in human physiology include their participation in bile acid biosynthesis, function as transport forms of cholesterol, and regulation of gene transcription.[58]

In biochemical experiments, radiolabelled forms of cholesterol, such as tritiated-cholesterol, are used. These derivatives undergo degradation upon storage, and it is essential to purify cholesterol prior to use. Cholesterol can be purified using small Sephadex LH-20 columns.[59]

Cholesterol is oxidized by the liver into a variety of bile acids.[60] These, in turn, are conjugated with glycine, taurine, glucuronic acid, or sulfate. A mixture of conjugated and nonconjugated bile acids, along with cholesterol itself, is excreted from the liver into the bile. Approximately 95% of the bile acids are reabsorbed from the intestines, and the remainder are lost in the feces.[61] The excretion and reabsorption of bile acids forms the basis of the enterohepatic circulation, which is essential for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats. Under certain circumstances, when more concentrated, as in the gallbladder, cholesterol crystallises and is the major constituent of most gallstones (lecithin and bilirubin gallstones also occur, but less frequently).[62] Every day, up to one gram of cholesterol enters the colon. This cholesterol originates from the diet, bile, and desquamated intestinal cells, and it can be metabolized by the colonic bacteria. Cholesterol is converted mainly into coprostanol, a nonabsorbable sterol that is excreted in the feces.[citation needed]

Although cholesterol is a steroid generally associated with mammals, the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis is able to completely degrade this molecule and contains a large number of genes that are regulated by its presence.[63] Many of these cholesterol-regulated genes are homologues of fatty acid β-oxidation genes, which have evolved in such a way as to bind large steroid substrates like cholesterol.[64][65]

Dietary sources

[edit]Animal fats are complex mixtures of triglycerides, with lesser amounts of both the phospholipids and cholesterol molecules from which all animal (and human) cell membranes are constructed. Since all animal cells manufacture cholesterol, all animal-based foods contain cholesterol in varying amounts.[66] Major dietary sources of cholesterol include red meat, egg yolks and whole eggs, liver, kidney, giblets, fish oil, shellfish, and butter.[67] Human breast milk also contains significant quantities of cholesterol.[68]

Plant cells synthesize cholesterol as a precursor for other compounds, such as phytosterols and steroidal glycoalkaloids, with cholesterol remaining in plant foods only in minor amounts or absent.[67][69] Some plant foods, such as avocado, flax seeds and peanuts, contain phytosterols, which compete with cholesterol for absorption in the intestines and reduce the absorption of both dietary and bile cholesterol.[70] A typical diet contributes in the order of 0.2 grams of phytosterols, not enough to have a significant impact on blocking cholesterol absorption. The intake of phytosterols can be supplemented through the use of phytosterol-containing functional foods or dietary supplements that are recognized as having potential to reduce levels of LDL-cholesterol.[71]

Medical guidelines and recommendations

[edit]In 2015, the scientific advisory panel of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture for the 2015 iteration of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans dropped the previously recommended limit of consumption of dietary cholesterol to 300 mg per day with a new recommendation to "eat as little dietary cholesterol as possible", thereby acknowledging an association between a diet low in cholesterol and reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.[72]

A 2013 report by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommended focusing on healthy dietary patterns rather than specific cholesterol limits, as they are hard for clinicians and consumers to implement. They recommend the DASH and Mediterranean diet, both of which are low in cholesterol.[73] A 2017 review by the American Heart Association recommends switching saturated fats for polyunsaturated fats to reduce cardiovascular disease risk.[74]

Some supplemental guidelines have recommended doses of phytosterols in the order of 1.6–3.0 grams per day (Health Canada, EFSA, ATP III, FDA). A meta-analysis demonstrated a 12% reduction in LDL-cholesterol at a mean dose of 2.1 grams per day.[75] The benefits of a diet supplemented with phytosterols have also been questioned.[76]

Clinical significance

[edit]Hypercholesterolemia

[edit]

According to the lipid hypothesis, elevated levels of cholesterol in the blood lead to atherosclerosis, which may increase the risk of heart attack, stroke, and peripheral artery disease. Since higher blood LDL – especially higher LDL concentrations and smaller LDL particle size – contributes to this process more than the cholesterol content of the HDL particles,[9] LDL particles are often termed "bad cholesterol". High concentrations of functional HDL, which can remove cholesterol from cells and atheromas, offer protection and are commonly referred to as "good cholesterol". These balances are mostly genetically determined but can be changed by body composition, medications, diet,[77] and other factors.[78] A 2007 study demonstrated that blood total cholesterol levels have an exponential effect on cardiovascular and total mortality, with the association more pronounced in younger subjects. Because cardiovascular disease is relatively rare in the younger population, the impact of high cholesterol on health is larger in older people.[79]

Elevated levels of the lipoprotein fractions, LDL, IDL and VLDL, rather than the total cholesterol level, correlate with the extent and progress of atherosclerosis.[80] Conversely, the total cholesterol can be within normal limits, yet be made up primarily of small LDL and small HDL particles, under which conditions atheroma growth rates are high. A post hoc analysis of the IDEAL and the EPIC prospective studies found an association between high levels of HDL cholesterol (adjusted for apolipoprotein A-I and apolipoprotein B) and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, casting doubt on the cardioprotective role of "good cholesterol".[81][82]

About one in 250 individuals has a genetic mutation for the LDL cholesterol receptor that causes them to have familial hypercholesterolemia.[83] Inherited high cholesterol can also include genetic mutations in the PCSK9 gene and the gene for apolipoprotein B.[84]

Elevated cholesterol levels are treatable by a diet that reduces or eliminates saturated fat, and trans fats,[85][86] often followed by one of various hypolipidemic agents, such as statins, fibrates, cholesterol absorption inhibitors, monoclonal antibody therapy (PCSK9 inhibitors), nicotinic acid derivatives or bile acid sequestrants.[87] There are several international guidelines on the treatment of hypercholesterolemia.[88]

Human trials using HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, commonly known as statins, have repeatedly confirmed that changing lipoprotein transport patterns from unhealthy to healthier patterns significantly lowers cardiovascular disease event rates, even for people with cholesterol values currently considered low for adults.[89] Studies have shown that reducing LDL cholesterol levels by about 38.7 mg/dL with the use of statins can reduce cardiovascular disease and stroke risk by about 21%.[90] Studies have also found that statins reduce atheroma progression.[91] As a result, people with a history of cardiovascular disease may derive benefit from statins irrespective of their cholesterol levels (total cholesterol below 5.0 mmol/L [193 mg/dL]),[92] and in men without cardiovascular disease, there is benefit from lowering abnormally high cholesterol levels ("primary prevention").[93] Primary prevention in women was originally practiced only by extension of the findings in studies on men,[94] since, in women, none of the large statin trials conducted prior to 2007 demonstrated a significant reduction in overall mortality or in cardiovascular endpoints.[95] Meta-analyses have demonstrated significant reductions in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, without significant heterogeneity by sex.[96]

| Level | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|

| mg/dL | mmol/L | |

| < 200 | < 5.2 | Desirable level (lower risk) |

| 200–240 | 5.2–6.2 | Borderline high risk |

| > 240 | > 6.2 | High risk |

The 1987 report of National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panels suggests the total blood cholesterol level should be: < 200 mg/dL normal blood cholesterol, 200–239 mg/dL borderline-high, > 240 mg/dL high cholesterol.[97] The American Heart Association provides a similar set of guidelines for total (fasting) blood cholesterol levels and risk for heart disease:[85] Statins are effective in lowering LDL cholesterol and widely used for primary prevention in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease, as well as in secondary prevention for those who have developed cardiovascular disease.[98] The average global mean total cholesterol for humans has remained at about 4.6 mmol/L (178 mg/dL) for men and women, both crude and age standardized, for nearly 40 years from 1980 to 2018, with some regional variations and reduction of total cholesterol in Western nations.[99]

More current testing methods determine LDL ("bad") and HDL ("good") cholesterol separately, allowing cholesterol analysis to be more nuanced. The desirable LDL level is considered to be less than 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L).[100][101]

Total cholesterol is defined as the sum of HDL, LDL, and VLDL. Usually, only the total, HDL, and triglycerides are measured. For cost reasons, the VLDL is usually estimated as one-fifth of the triglycerides, and the LDL is estimated using the Friedewald formula (or a variant): estimated LDL = [total cholesterol] − [total HDL] − [estimated VLDL]. Direct LDL measures are used when triglycerides exceed 400 mg/dL. The estimated VLDL and LDL have more error when triglycerides are above 400 mg/dL.[102]

In the Framingham Heart Study, each 10 mg/dL (0.6 mmol/L) increase in total cholesterol levels increased 30-year overall mortality by 5% and CVD mortality by 9%. While subjects over the age of 50 had an 11% increase in overall mortality, and a 14% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality per 1 mg/dL (0.06 mmol/L) year drop in total cholesterol levels. The researchers attributed this phenomenon to a different correlation, whereby the disease itself increases the risk of death, as well as changing a myriad of factors, such as weight loss and the inability to eat, which lower serum cholesterol.[103] This effect was also shown in men of all ages and women over 50 in the Vorarlberg Health Monitoring and Promotion Programme. These groups were more likely to die of cancer, liver diseases, and mental diseases with very low total cholesterol, of 186 mg/dL (10.3 mmol/L) and lower. This result indicates the low-cholesterol effect occurs even among younger respondents, contradicting the previous assessment among cohorts of older people that this is a marker for frailty occurring with age.[104]

Hypocholesterolemia

[edit]Abnormally low levels of cholesterol are termed hypocholesterolemia. Research into the causes of this state is relatively limited, but some studies suggest a link with depression, cancer, and cerebral hemorrhage. In general, the low cholesterol levels seem to be a consequence, rather than a cause, of an underlying illness.[79] A genetic defect in cholesterol synthesis causes Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, often associated with low plasma cholesterol levels. Hyperthyroidism, or any other endocrine disturbance that causes upregulation of the LDL receptor, may result in hypocholesterolemia.[105]

Testing

[edit]The American Heart Association recommends testing cholesterol every four to six years for people aged 20 years or older.[106] A separate set of American Heart Association guidelines issued in 2013 indicates that people taking statin medications should have their cholesterol tested 4–12 weeks after their first dose and then every 3–12 months thereafter.[107][108] For men ages 45 to 65 and women ages 55 to 65, a cholesterol test should be performed every one to two years, and an annual test should be performed for seniors over the age of 65.[107]

After 12 hours of fasting, a blood sample is taken by a healthcare professional from an arm vein to measure a lipid profile for a) total cholesterol, b) HDL cholesterol, c) LDL cholesterol, and d) triglycerides.[3][107] Results may be expressed as "calculated", indicating a calculation of total cholesterol, HDL, and triglycerides.[3]

Cholesterol is tested to determine for "normal" or "desirable" levels if a person has a total cholesterol of 5.2 mmol/L or less (200 mg/dL), an HDL value of more than 1 mmol/L (40 mg/dL, "the higher, the better"), an LDL value of less than 2.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL), and a triglycerides level of less than 1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL).[107][3] Blood cholesterol in people with lifestyle, aging, or cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, family history of coronary artery disease, or angina, are evaluated at different levels.[107]

Interactive pathway map

[edit]Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.[§ 1]

- ^ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "Statin_Pathway_WP430".

Cholesteric liquid crystals

[edit]Some cholesterol derivatives (among other simple cholesteric lipids) are known to generate the cholesteric liquid crystalline phase. The cholesteric phase is, in fact, a chiral nematic phase, and it changes color when its temperature changes. This makes cholesterol derivatives useful for indicating temperature in liquid-crystal display thermometers and in temperature-sensitive paints.[109]

Stereoisomers

[edit]

Cholesterol has 256 stereoisomers that arise from its eight stereocenters. Only two of the stereoisomers have biochemical significance: nat-cholesterol and ent-cholesterol (for natural and enantiomer, respectively).[110][111] The only cholesterol stereoisomer to occur naturally is nat-cholesterol.

Additional images

[edit]-

Cholesterol units conversion

-

Steroidogenesis, using cholesterol as building material

-

Space-filling model of the Cholesterol molecule

-

Numbering of the steroid nuclei

See also

[edit]- Arcus senilis "Cholesterol ring" in the eyes

- Cardiovascular disease – Class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels

- Cholesterol embolism

- Cholesterol total synthesis

- Familial hypercholesterolemia – Genetic disorder characterized by high cholesterol levels

- Hypercholesterolemia – High levels of cholesterol in the blood

- Hypocholesterolemia

- Janus-faced molecule

- List of cholesterol in foods

- Niemann–Pick disease – Medical condition

- Oxycholesterol

- Remnant cholesterol

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Cholesterol, 57-88-5". PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Safety (MSDS) data for cholesterol". Archived from the original on 12 July 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Cholesterol". MedlinePlus, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health. 10 December 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Cholesterol at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Narwal V, Deswal R, Batra B, Kalra V, Hooda R, Sharma M, et al. (March 2019). "Cholesterol biosensors: A review". Steroids. 143: 6–17. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2018.12.003. PMID 30543816.

- ^ Wang H, Kulas JA, Wang C, Holtzman DM, Ferris HA, Hansen SB (August 2021). "Regulation of beta-amyloid production in neurons by astrocyte-derived cholesterol". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (33) e2102191118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11802191W. doi:10.1073/pnas.2102191118. PMC 8379952. PMID 34385305.

- ^ Razin S, Tully JG (May 1970). "Cholesterol requirement of mycoplasmas". Journal of Bacteriology. 102 (2): 306–310. doi:10.1128/JB.102.2.306-310.1970. PMC 247552. PMID 4911537.

- ^ a b Hanukoglu I (December 1992). "Steroidogenic enzymes: structure, function, and role in regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 43 (8): 779–804. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90307-5. PMID 22217824. S2CID 112729.

- ^ a b Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, et al. (April 2008). "Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation". Diabetes Care. 31 (4): 811–822. doi:10.2337/dc08-9018. PMID 18375431.

- ^ Chevreul ME (1816). "Recherches chimiques sur les corps gras, et particulièrement sur leurs combinaisons avec les alcalis. Sixième mémoire. Examen des graisses d'homme, de mouton, de boeuf, de jaguar et d'oie" [Chemical researches on fatty substances, and particularly on their combinations o filippos ine kapios with alkalis. Sixth memoir. Study of human, sheep, beef, jaguar and goose fat]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 2: 339–372 [346].

Je nommerai cholesterine, de χολη, bile, et στερεος, solide, la substance cristallisée des calculs biliares humains, ...

[I will name cholesterine – from χολη (bile) and στερεος (solid) – the crystalized substance from human gallstones ...] - ^ Olson RE (February 1998). "Discovery of the lipoproteins, their role in fat transport and their significance as risk factors". The Journal of Nutrition. 128 (2 Suppl): 439S – 443S. doi:10.1093/jn/128.2.439S. PMID 9478044.

- ^ Luo J, Yang H, Song BL (April 2020). "Mechanisms and regulation of cholesterol homeostasis". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 21 (4): 225–245. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0190-7. PMID 31848472. S2CID 209392321.

- ^ Hansen SB, Wang H (September 2023). "The shared role of cholesterol in neuronal and peripheral inflammation". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 249 108486. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108486. PMID 37390970. S2CID 259303593.

- ^ Bae SH, Lee JN, Fitzky BU, Seong J, Paik YK (May 1999). "Cholesterol biosynthesis from lanosterol. Molecular cloning, tissue distribution, expression, chromosomal localization, and regulation of rat 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase, a Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome-related protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (21): 14624–14631. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.21.14624. PMID 10329655.

- ^ "National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey" (PDF). United States Center for Disease Control. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ Lecerf JM, de Lorgeril M (July 2011). "Dietary cholesterol: from physiology to cardiovascular risk". The British Journal of Nutrition. 106 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1017/S0007114511000237. PMID 21385506.

- ^ Angel A, Farkas J (September 1974). "Regulation of cholesterol storage in adipose tissue". Journal of Lipid Research. 15 (5): 491–499. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)36769-9. PMID 4415522.

- ^ Dubois C, Armand M, Mekki N, Portugal H, Pauli AM, Bernard PM, et al. (November 1994). "Effects of increasing amounts of dietary cholesterol on postprandial lipemia and lipoproteins in human subjects". Journal of Lipid Research. 35 (11): 1993–2007. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)39946-6. PMID 7868978.

- ^ Behrman EJ, Gopalan V (2005). Scovell WM (ed.). "Cholesterol and Plants". Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (12): 1791. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82.1791B. doi:10.1021/ed082p1791.

- ^ John S, Sorokin AV, Thompson PD (February 2007). "Phytosterols and vascular disease". Current Opinion in Lipidology. 18 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e328011e9e3. PMID 17218830. S2CID 29213889.

- ^ Jesch ED, Carr TP (June 2017). "Food Ingredients That Inhibit Cholesterol Absorption". Preventive Nutrition and Food Science. 22 (2): 67–80. doi:10.3746/pnf.2017.22.2.67. PMC 5503415. PMID 28702423.

- ^ Agren JJ, Tvrzicka E, Nenonen MT, Helve T, Hänninen O (February 2001). "Divergent changes in serum sterols during a strict uncooked vegan diet in patients with rheumatoid arthritis". The British Journal of Nutrition. 85 (2): 137–139. doi:10.1079/BJN2000234. PMID 11242480.

- ^ Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L (2010). Biochemistry (7th ed.). p. 350.

- ^ Sadava D, Hillis DM, Heller HC, Berenbaum MR (2011). "Cell Membranes". Life: The Science of Biology (9th ed.). San Francisco: Freeman. pp. 105–114. ISBN 978-1-4292-4646-0.

- ^ Ohvo-Rekilä H, Ramstedt B, Leppimäki P, Slotte JP (January 2002). "Cholesterol interactions with phospholipids in membranes". Progress in Lipid Research. 41 (1): 66–97. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(01)00020-0. PMID 11694269.

- ^ Yeagle PL (October 1991). "Modulation of membrane function by cholesterol". Biochimie. 73 (10): 1303–1310. doi:10.1016/0300-9084(91)90093-G. PMID 1664240.

- ^ Haines TH (July 2001). "Do sterols reduce proton and sodium leaks through lipid bilayers?". Progress in Lipid Research. 40 (4): 299–324. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(01)00009-1. PMID 11412894. S2CID 32236169.

- ^ Petersen EN, Chung HW, Nayebosadri A, Hansen SB (December 2016). "Kinetic disruption of lipid rafts is a mechanosensor for phospholipase D". Nature Communications. 7 13873. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713873P. doi:10.1038/ncomms13873. PMC 5171650. PMID 27976674.

- ^ Incardona JP, Eaton S (April 2000). "Cholesterol in signal transduction". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 12 (2): 193–203. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00076-9. PMID 10712926.

- ^ Pawlina W, Ross MW (2006). "Supporting Cells of the Nervous System". Histology: a text and atlas: with correlated cell and molecular biology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-7817-5056-1.

- ^ Lubetzki C, Stankoff B (2014). "Demyelination in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 122. pp. 89–99. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52001-2.00004-2. ISBN 978-0-444-52001-2. ISSN 0072-9752. PMC 7152443. PMID 24507514.

- ^ Levitan I, Singh DK, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A (2014). "Cholesterol binding to ion channels". Frontiers in Physiology. 5: 65. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00065. PMC 3935357. PMID 24616704.

- ^ a b c Wei W, Schwaid AG, Wang X, Wang X, Chen S, Chu Q, et al. (March 2016). "Ligand Activation of ERRα by Cholesterol Mediates Statin and Bisphosphonate Effects". Cell Metabolism. 23 (3): 479–491. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.010. PMC 4785078. PMID 26777690.

- ^ a b c d Zuo H, Wan Y (2017). "Nuclear Receptors in Skeletal Homeostasis". In Forrest D, Tsai S (eds.). Nuclear Receptors in Development and Disease. Elsevier Science. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-12-802196-5.

- ^ Payne AH, Hales DB (December 2004). "Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones". Endocrine Reviews. 25 (6): 947–970. doi:10.1210/er.2003-0030. PMID 15583024.

- ^ a b c Elias PM, Feingold KR (2006). "Stratum Corneum Barrier Function: Definitions and Broad Concepts". In Elias PM (ed.). Skin barrier. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8247-5815-8.

- ^ a b c d Merleev AA, Le ST, Alexanian C, Toussi A, Xie Y, Marusina AI, et al. (August 2022). "Biogeographic and disease-specific alterations in epidermal lipid composition and single-cell analysis of acral keratinocytes". JCI Insight. 7 (16) e159762. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.159762. PMC 9462509. PMID 35900871.

- ^ Elias PM, Williams ML, Maloney ME, Bonifas JA, Brown BE, Grayson S, et al. (October 1984). "Stratum corneum lipids in disorders of cornification. Steroid sulfatase and cholesterol sulfate in normal desquamation and the pathogenesis of recessive X-linked ichthyosis". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 74 (4): 1414–1421. doi:10.1172/JCI111552. PMC 425309. PMID 6592175.

- ^ Cohen DE (April 2008). "Balancing cholesterol synthesis and absorption in the gastrointestinal tract". Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2 (2): S1 – S3. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2008.01.004. PMC 2390860. PMID 19343078.

- ^ "How it's made: Cholesterol production in your body". Harvard Health Publishing. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Biosynthesis and Regulation of Cholesterol (with Animation)". PharmaXChange.info. 17 September 2013. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Cholesterol metabolism (includes both Bloch and Kandutsch-Russell pathways) (Mus musculus) – WikiPathways". wikipathways.org. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Singh P, Saxena R, Srinivas G, Pande G, Chattopadhyay A (2013). "Cholesterol biosynthesis and homeostasis in regulation of the cell cycle". PLOS ONE. 8 (3) e58833. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858833S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058833. PMC 3598952. PMID 23554937.

- ^ "Kandutsch-Russell pathway". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Berg J (2002). Biochemistry. New York: WH Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3051-4.

- ^ Rhodes CM, Stryer L, Tasker R (1995). Biochemistry (4th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 280, 703. ISBN 978-0-7167-2009-6.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1964". Nobel Prize, Nobel Media.

- ^ Espenshade PJ, Hughes AL (2007). "Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes". Annual Review of Genetics. 41: 401–427. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130315. PMID 17666007.

- ^ Brown MS, Goldstein JL (May 1997). "The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor". Cell. 89 (3): 331–340. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5. PMID 9150132. S2CID 17882616.

- ^ a b Tymoczko JL, Berg T, Stryer L, Berg JM (2002). Biochemistry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 726–727. ISBN 978-0-7167-4955-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Patton KT, Thibodeau GA (2010). Anatomy and Physiology (7th ed.). Mosby/Elsevier. ISBN 978-99960-57-76-2.[page needed]

- ^ Mahley RW (July 2016). "Apolipoprotein E: from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 94 (7): 739–746. doi:10.1007/s00109-016-1427-y. PMC 4921111. PMID 27277824.

- ^ Weingärtner O, Pinsdorf T, Rogacev KS, Blömer L, Grenner Y, Gräber S, et al. (October 2010). Federici M (ed.). "The relationships of markers of cholesterol homeostasis with carotid intima-media thickness". PLOS ONE. 5 (10) e13467. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513467W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013467. PMC 2956704. PMID 20976107.

- ^ Lewis GF, Rader DJ (June 2005). "New insights into the regulation of HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport". Circulation Research. 96 (12): 1221–1232. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000170946.56981.5c. PMID 15976321.

- ^ Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, et al. (January 1989). "High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies". Circulation. 79 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.79.1.8. PMID 2642759.

- ^ Miller NE, Thelle DS, Forde OH, Mjos OD (May 1977). "The Tromsø heart-study. High-density lipoprotein and coronary heart-disease: a prospective case-control study". Lancet. 1 (8019): 965–968. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92274-7. PMID 67464. S2CID 140204202.

- ^ Kandutsch AA, Chen HW, Heiniger HJ (August 1978). "Biological activity of some oxygenated sterols". Science. 201 (4355): 498–501. Bibcode:1978Sci...201..498K. doi:10.1126/science.663671. PMID 663671.

- ^ Russell DW (December 2000). "Oxysterol biosynthetic enzymes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1529 (1–3): 126–135. doi:10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00142-6. PMID 11111082.

- ^ Hanukoglu I, Jefcoate CR (1980). "Pregnenolone separation from cholesterol using Sephadex LH-20 mini-columns". Journal of Chromatography A. 190 (1): 256–262. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)85545-4.

- ^ Javitt NB (December 1994). "Bile acid synthesis from cholesterol: regulatory and auxiliary pathways". FASEB Journal. 8 (15): 1308–1311. doi:10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001744. PMID 8001744. S2CID 20302590.

- ^ Wolkoff AW, Cohen DE (February 2003). "Bile acid regulation of hepatic physiology: I. Hepatocyte transport of bile acids". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 284 (2): G175 – G179. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00409.2002. PMID 12529265.

- ^ Marschall HU, Einarsson C (June 2007). "Gallstone disease". Journal of Internal Medicine. 261 (6): 529–542. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01783.x. PMID 17547709. S2CID 8609639.

- ^ Wipperman MF, Sampson NS, Thomas ST (2014). "Pathogen roid rage: cholesterol utilization by Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 49 (4): 269–293. doi:10.3109/10409238.2014.895700. PMC 4255906. PMID 24611808.

- ^ Thomas ST, Sampson NS (April 2013). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis utilizes a unique heterotetrameric structure for dehydrogenation of the cholesterol side chain". Biochemistry. 52 (17): 2895–2904. doi:10.1021/bi4002979. PMC 3726044. PMID 23560677.

- ^ Wipperman MF, Yang M, Thomas ST, Sampson NS (October 2013). "Shrinking the FadE proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: insights into cholesterol metabolism through identification of an α2β2 heterotetrameric acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase family". Journal of Bacteriology. 195 (19): 4331–4341. doi:10.1128/JB.00502-13. PMC 3807453. PMID 23836861.

- ^ Christie WW (2003). Lipid analysis: isolation, separation, identification, and structural analysis of lipids. Ayr, Scotland: Oily Press. ISBN 978-0-9531949-5-7. [page needed]

- ^ a b "Cholesterol content in foods, rank order per 100 g; In: USDA Food Composition Databases". United States Department of Agriculture. 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.[dead link]

- ^ Jensen RG, Hagerty MM, McMahon KE (June 1978). "Lipids of human milk and infant formulas: a review". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 31 (6): 990–1016. doi:10.1093/ajcn/31.6.990. PMID 352132.

- ^ Sonawane PD, Pollier J, Panda S, Szymanski J, Massalha H, Yona M, et al. (December 2016). "Plant cholesterol biosynthetic pathway overlaps with phytosterol metabolism". Nature Plants. 3 (1) 16205. doi:10.1038/nplants.2016.205. PMID 28005066. S2CID 5518449.

- ^ De Smet E, Mensink RP, Plat J (July 2012). "Effects of plant sterols and stanols on intestinal cholesterol metabolism: suggested mechanisms from past to present". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 56 (7): 1058–1072. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201100722. PMID 22623436.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority, Journal (2010). "Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to plant sterols and plant stanols and maintenance of normal blood cholesterol concentrations".

- ^ "2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines | health.gov". health.gov. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Carson JA, Lichtenstein AH, Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Meyer KA, et al. (January 2020). "Dietary Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Risk: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 141 (3): e39 – e53. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000743. PMID 31838890.

- ^ Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. (July 2017). "Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (3): e1 – e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. PMID 28620111. S2CID 367602.

- ^ Ras RT, Geleijnse JM, Trautwein EA (July 2014). "LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of plant sterols and stanols across different dose ranges: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies". The British Journal of Nutrition. 112 (2): 214–219. doi:10.1017/S0007114514000750. PMC 4071994. PMID 24780090.

- ^ Weingärtner O, Böhm M, Laufs U (February 2009). "Controversial role of plant sterol esters in the management of hypercholesterolaemia". European Heart Journal. 30 (4): 404–409. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn580. PMC 2642922. PMID 19158117.

- ^ "More evidence for Mediterranean diet". Department of Health (UK), NHS Choices. 8 March 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ Durrington P (August 2003). "Dyslipidaemia". Lancet. 362 (9385): 717–731. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14234-1. PMID 12957096. S2CID 208792416.

- ^ a b Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–1839. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058. S2CID 54293528.

- ^ "Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final Report" (PDF). National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. 1 September 2002. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ van der Steeg WA, Holme I, Boekholdt SM, Larsen ML, Lindahl C, Stroes ES, et al. (February 2008). "High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein particle size, and apolipoprotein A-I: significance for cardiovascular risk: the IDEAL and EPIC-Norfolk studies". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 51 (6): 634–642. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.060. PMID 18261682.

- ^ Robinson JG, Wang S, Jacobson TA (November 2012). "Meta-analysis of comparison of effectiveness of lowering apolipoprotein B versus low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and nonhigh-density lipoprotein cholesterol for cardiovascular risk reduction in randomized trials". The American Journal of Cardiology. 110 (10): 1468–1476. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.007. PMID 22906895.

- ^ Akioyamen LE, Genest J, Shan SD, Reel RL, Albaum JM, Chu A, et al. (September 2017). "Estimating the prevalence of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 7 (9) e016461. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016461. PMC 5588988. PMID 28864697.

- ^ "Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH)". heart.org. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Prevention and Treatment of High Cholesterol (Hyperlipidemia)". American Heart Association. 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Cholesterol: Top foods to improve your numbers". Mayo Clinic. 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification. London, 2008.

- ^ Mannu GS, Zaman MJ, Gupta A, Rehman HU, Myint PK (October 2012). "Update on guidelines for management of hypercholesterolemia". Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 10 (10): 1239–1249. doi:10.1586/erc.12.94. PMID 23190064. S2CID 5451203.

- ^ Kizer JR, Madias C, Wilner B, Vaughan CJ, Mushlin AI, Trushin P, et al. (May 2010). "Relation of different measures of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to risk of coronary artery disease and death in a meta-regression analysis of large-scale trials of statin therapy". The American Journal of Cardiology. 105 (9): 1289–1296. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.12.051. PMC 2917836. PMID 20403481.

- ^ Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. (June 2019). "2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 139 (25): e1082 – e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625. PMC 7403606. PMID 30586774.

- ^ Nicholls SJ (August 2008). "Rosuvastatin and progression of atherosclerosis". Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 6 (7): 925–933. doi:10.1586/14779072.6.7.925. PMID 18666843. S2CID 46419583.

- ^ Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group (July 2002). "MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 360 (9326): 7–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. PMID 12114036. S2CID 35836642.

- ^ Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Isles CG, Lorimer AR, MacFarlane PW, et al. (November 1995). "Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (20): 1301–1307. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. PMID 7566020.

- ^ Grundy SM (May 2007). "Should women be offered cholesterol lowering drugs to prevent cardiovascular disease? Yes". BMJ. 334 (7601): 982. doi:10.1136/bmj.39202.399942.AD. PMC 1867899. PMID 17494017.

- ^ Kendrick M (May 2007). "Should women be offered cholesterol lowering drugs to prevent cardiovascular disease? No". BMJ. 334 (7601): 983. doi:10.1136/bmj.39202.397488.AD. PMC 1867901. PMID 17494018.

- ^ Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, Gotto AM, Shepherd J, Westendorp RG, et al. (June 2009). "The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 338 b2376. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2376. PMC 2714690. PMID 19567909.

- ^ "Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. The Expert Panel". Archives of Internal Medicine. 148 (1): 36–69. January 1988. doi:10.1001/archinte.148.1.36. PMID 3422148.

- ^ Alenghat FJ, Davis AM (February 2019). "Management of Blood Cholesterol". JAMA. 321 (8): 800–801. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0015. PMC 6679800. PMID 30715135.

- ^ "Mean total cholesterol trends Global estimates". World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "How To Get Your Cholesterol Tested". American Heart Association. 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "About cholesterol". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 March 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Warnick GR, Knopp RH, Fitzpatrick V, Branson L (January 1990). "Estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by the Friedewald equation is adequate for classifying patients on the basis of nationally recommended cutpoints". Clinical Chemistry. 36 (1): 15–19. doi:10.1093/clinchem/36.1.15. PMID 2297909.

- ^ Anderson KM, Castelli WP, Levy D (24 April 1987). "Cholesterol and mortality. 30 years of follow-up from the Framingham study". JAMA. 257 (16): 2176–2180. doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03390160062027. PMID 3560398.

- ^ Ulmer H, Kelleher C, Diem G, Concin H (2004). "Why Eve is not Adam: prospective follow-up in 149650 women and men of cholesterol and other risk factors related to cardiovascular and all-cause mortality". Journal of Women's Health. 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1089/154099904322836447. PMID 15006277.

- ^ Rizos CV, Elisaf MS, Liberopoulos EN (24 February 2011). "Effects of thyroid dysfunction on lipid profile". The Open Cardiovascular Medicine Journal. 5 (1): 76–84. doi:10.2174/1874192401105010076. PMC 3109527. PMID 21660244.

- ^ "How To Get Your Cholesterol Tested". American Heart Association. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Cholesterol test". Mayo Clinic. 15 May 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Stone NJ, Robinson J, Goff DC (2013). "Getting a grasp of the Guidelines". American College of Cardiology. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Atkins MD, Boer MF (2016). "Chapter 2 - Flow Visualization". In Kim T, Song SJ, Lu TJ (eds.). Application of Thermo-Fluidic Measurement Techniques: An Introduction. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 15–59. doi:10.1016/C2015-0-01881-0. ISBN 978-0-12-809731-1.

- ^ Westover EJ, Covey DF, Brockman HL, Brown RE, Pike LJ (December 2003). "Cholesterol depletion results in site-specific increases in epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation due to membrane level effects. Studies with cholesterol enantiomers". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (51): 51125–51133. doi:10.1074/jbc.M304332200. PMC 2593805. PMID 14530278.

- ^ Kristiana I, Luu W, Stevenson J, Cartland S, Jessup W, Belani JD, et al. (September 2012). "Cholesterol through the looking glass: ability of its enantiomer also to elicit homeostatic responses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (40): 33897–33904. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.360537. PMC 3460484. PMID 22869373.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cholesterol at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cholesterol at Wikimedia Commons

Cholesterol

View on GrokipediaEtymology and History

Etymology

The term "cholesterol" originates from the Greek words chole (χολή), meaning "bile," and stereos (στερεός), meaning "solid" or "stiff," combined with the chemical suffix "-ol," denoting an alcohol.[7] This nomenclature reflects the compound's initial identification as a waxy, solid substance found in bile and gallstones.[8] In 1769, French chemist François Poulletier de la Salle first isolated the substance from gallstones, describing it as a fatty, crystalline material in bile, though he did not coin a specific name for it.[9] The term "cholesterine" was later introduced in 1815 by French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, who independently rediscovered and purified the compound from bile, deriving the name to highlight its biliary origin and solid form.[8] Over time, the terminology evolved from "cholesterine" to the modern "cholesterol," standardized in the early 20th century as chemical understanding advanced, while retaining its roots in the substance's waxy, bile-associated properties.[9]Discovery and Early Research

The first observation of cholesterol occurred in 1769 when French chemist and physician François Poulletier de la Salle identified a fatty, waxy substance in gallstones during his chemical analyses.[10] This substance was independently isolated and characterized in 1815 by French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, who extracted it from bile and named it "cholesterine," derived from the Greek words for bile (chole) and solid (stereos), recognizing its crystalline form.[8] Throughout the 19th century, researchers advanced the understanding of cholesterol through crystallization techniques and elemental analysis, confirming its composition as a complex alcohol related to fats; Heinrich Otto Wieland, building on this foundation, elucidated the structures of bile acids—cholesterol derivatives—through meticulous degradative studies, earning the 1927 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for these contributions.[11][12] In the early 20th century, Russian pathologist Nikolai Anitschkow established a pivotal link between cholesterol and vascular disease by feeding rabbits a diet enriched with pure cholesterol, inducing hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerotic lesions in their aortas, as detailed in his 1913 experiments. This built on earlier 1908 experiments by Russian pathologist Alexander Ignatovsky, who first induced atherosclerotic lesions in rabbits by feeding them diets rich in animal products such as milk, eggs, and meat.[13][14] In the mid-20th century, the association between dietary cholesterol, saturated fats, and cardiovascular disease gained prominence through Ancel Keys' Seven Countries Study (1958–1970), an epidemiological investigation involving 16 cohorts across seven nations that correlated dietary saturated fat intake with serum cholesterol levels and coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality rates, positioning cholesterol as a key mediator in atherosclerosis.[15] This research significantly influenced early American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, including the 1961 conference report on diet and CHD, which recommended reducing intake of saturated fats and cholesterol, promoting low-fat diets, and encouraging cholesterol screening to mitigate cardiovascular risk.[16] However, the Seven Countries Study has faced methodological critiques, particularly regarding Keys' selection of data from only seven out of 22 available countries, excluding high-fat, low-CHD cases such as France and Switzerland. An analysis by Yerushalmy and Hilleboe (1957) of the full 22-nation dataset found no significant correlation between dietary fat and CHD mortality, attributing observed patterns to socioeconomic and other non-causal factors rather than direct dietary causation.[17] These controversies highlight the contentious evolution of cholesterol research, from early animal models to modern guidelines that adopt a multifactorial approach to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, as outlined in the 2018 AHA/ACC guidelines, which integrate LDL cholesterol assessment with factors like hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.[18] Subsequent decades saw evolving definitions of "elevated" cholesterol levels, shifting from looser pre-statin norms to stricter thresholds amid pharmacological advances. Before statins (pre-1980s), total cholesterol was the primary metric, with levels up to 300 mg/dL often considered normal in adults (e.g., Framingham Study 1948-1960s data showed average TC ~220-250 mg/dL without alarm for many).[19] The 1988 NCEP guidelines introduced LDL-C specific thresholds: desirable <130 mg/dL, borderline 130-159 mg/dL, high ≥160 mg/dL.[20] By ATP III (2001), desirable dropped to <100 mg/dL for high-risk groups, with optional <70 mg/dL in very high risk (2004 update).[21] The 2013 ACC/AHA emphasized statin intensity over fixed numbers, but 2018-2025 updates reinforced aggressive goals: LDL-C <70 mg/dL (very high risk), or <55 mg/dL if persistent, reflecting "lower is better" supported by trials (e.g., CTT meta: risk reduction per LDL drop).[18][22] Critics note these progressive lowerings coincided with statin commercialization (lovastatin 1987), potentially expanding "high" LDL diagnoses from ~25% to >50% of adults, though evidence affirms benefits in targeted populations.[23] This extends historical context to guideline evolution and changing norms.Chemical Structure and Properties

Molecular Structure

Cholesterol has the molecular formula C27H46O.[24] As a sterol, cholesterol features a characteristic tetracyclic structure consisting of four fused rings: three six-membered rings (labeled A, B, and C) and one five-membered ring (D), collectively forming the gonane core.[24] This core is adorned with angular methyl groups at positions C10 and C13, a hydroxyl group (-OH) attached at C3 in the β-orientation, and a double bond between C5 and C6 in ring A.[24] Additionally, an eight-carbon isooctyl side chain, specifically a 6-methylheptan-2-yl group, branches from C17 on ring D.[24] The arrangement of these elements confers cholesterol's amphipathic nature, with the polar hydroxyl head group enabling interactions with aqueous environments and the nonpolar hydrocarbon rings and tail promoting association with hydrophobic regions. This base structure also underlies the existence of various stereoisomers of cholesterol.[24]Stereoisomers and Physical Properties

Cholesterol possesses eight chiral centers at carbons 3, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 17, and 20, resulting in 2^8 = 256 possible stereoisomers.[25] The naturally occurring form in animals is the specific stereoisomer designated as (3β)-cholest-5-en-3-ol, featuring a β-configuration at the 3-hydroxyl group and defined absolute configurations at all chiral centers that enable its integration into biological membranes.[24] This particular stereoisomer is biosynthesized exclusively by living organisms, while synthetic or laboratory preparations may yield diastereomers by inverting select chiral centers, though these variants exhibit altered physical and biological properties. Key physical properties of cholesterol include a melting point of 148–150 °C, reflecting its stability as a solid under physiological conditions.[24] It is practically insoluble in water, with a solubility of approximately 0.000095 g/L at 30 °C, which contributes to its tendency to aggregate in aqueous environments.[24] In contrast, cholesterol is highly soluble in nonpolar solvents such as chloroform, ethanol, and fats, as well as in oils and benzene, facilitating its extraction and analysis in organic media.[26] The density of crystalline cholesterol is 1.05–1.06 g/cm³ at 25 °C, and it exhibits a specific optical rotation of [α]_D^{20} ≈ -31° to -39° (depending on solvent, e.g., -31.5° in ether or -36° in dioxane), confirming its chirality and the dominance of the levorotatory natural enantiomer.[24][26] Cholesterol displays polymorphism, existing in multiple crystalline forms that influence its solubility and phase behavior. Anhydrous cholesterol can adopt at least two polymorphic phases, with a transition between them occurring around 38 °C, affecting properties like density and dissolution rates in lipid systems.[27] Additionally, it forms a stable monohydrate crystal, which appears as rhomb-shaped plates in triclinic symmetry under certain conditions, while a monoclinic monohydrate variant assembles into rod-like or helical structures, particularly in hydrated environments mimicking biological contexts.[28][29] These polymorphic forms underscore cholesterol's versatility in solid-state packing, with the monohydrate being more prevalent in aqueous suspensions due to hydrogen bonding with water molecules.[30]Biological Functions

Role in Cell Membranes

Cholesterol constitutes approximately 30–40 mol% of the lipids in the mammalian plasma membrane, making it a primary structural component that integrates deeply into the bilayer.[31] By intercalating between the hydrocarbon chains of phospholipids, it orients its hydroxyl group toward the polar headgroups and its steroid ring and tail within the hydrophobic core, thereby influencing the overall architecture and dynamics of the membrane.[32] A key function of cholesterol is to regulate membrane fluidity across physiological temperatures. At low temperatures, it prevents the crystallization of phospholipid acyl chains into a rigid gel phase by disrupting tight packing, thus maintaining sufficient fluidity to support cellular processes.[33] Conversely, at higher temperatures, cholesterol restricts the excessive motion of acyl chains in the liquid-disordered phase, increasing packing order and reducing fluidity to preserve membrane integrity.[32] This buffering effect broadens the gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperature of phospholipids, eliminating sharp transitions and ensuring a stable, semi-fluid state.[33] Cholesterol also modulates phase behavior in heterogeneous membranes. In fluid phospholipid environments, such as those dominated by phosphatidylcholine, it promotes a liquid-ordered phase by enhancing lipid order without fully immobilizing the chains.[34] In more ordered gel-like phases, such as those involving sphingomyelin, it fluidizes the structure by intercalating and loosening chain interactions.[34] These effects contribute to the formation of lipid rafts—cholesterol- and sphingolipid-enriched microdomains that exhibit liquid-ordered properties and serve as platforms for signal transduction, protein sorting, and membrane trafficking.[34]As a Precursor for Steroids and Bile Acids

Cholesterol serves as the essential precursor for the synthesis of steroid hormones, bile acids, and vitamin D, playing a critical role in endocrine function, lipid digestion, and calcium homeostasis. These conversions represent key catabolic pathways that utilize cholesterol beyond its structural role in cell membranes, where it also acts as a reservoir for these derivatives. The processes occur primarily in specialized tissues such as the adrenal glands, gonads, liver, and skin, ensuring the production of bioactive molecules vital for physiological regulation. In steroidogenesis, cholesterol undergoes side-chain cleavage catalyzed by the mitochondrial cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP11A1, also known as cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme or P450scc) to form pregnenolone, the foundational intermediate for all steroid hormones.[35] This reaction involves a three-step oxidation process, removing the eight-carbon side chain from cholesterol's C17 position and liberating isocaproic acid.[36] Pregnenolone is then further metabolized through a series of enzymatic steps in the adrenal cortex, gonads, and placenta to produce glucocorticoids such as cortisol, mineralocorticoids like aldosterone, and sex hormones including estrogens (e.g., estradiol) and androgens (e.g., testosterone).[37] These hormones regulate stress responses, electrolyte balance, and reproductive functions, respectively, with daily production rates typically ranging from 10-50 mg for major steroids in adults.[1] Bile acid synthesis occurs predominantly in hepatocytes, where cholesterol is converted via the classic (neutral) pathway, initiated by the rate-limiting enzyme cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1).[38] This cytochrome P450 enzyme hydroxylates cholesterol at the C7 position, leading to the formation of primary bile acids: cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid, through a multi-enzymatic process involving at least 14 steps.[39] The primary bile acids are then conjugated in the liver with glycine or taurine by bile acid-CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase (BAAT), forming bile salts such as glycocholate and taurochenodeoxycholate, which enhance solubility and are secreted into bile for storage in the gallbladder.[40] These bile salts emulsify dietary fats and facilitate their absorption in the intestine, with daily synthesis accounting for approximately 400-600 mg of cholesterol conversion in humans, representing a major route of cholesterol catabolism.[41] Cholesterol also contributes to vitamin D production indirectly, as its derivative 7-dehydrocholesterol, an intermediate produced endogenously during cholesterol biosynthesis in the skin, serves as the immediate precursor to cholecalciferol (vitamin D3).[42] Upon exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation (wavelength 290-320 nm), 7-dehydrocholesterol undergoes photochemical ring cleavage to form previtamin D3, which thermally isomerizes to cholecalciferol.[42] This process occurs primarily in the epidermis and is crucial for maintaining calcium and phosphate balance, though endogenous production varies with sunlight exposure and is minimal compared to bile acid utilization.[43] Overall, these pathways represent the primary routes of cholesterol catabolism, with bile acid synthesis dominating the flux and steroid/vitamin D production comprising smaller but essential fractions.[44]Biosynthesis and Regulation

Biosynthetic Pathway

Cholesterol biosynthesis, also known as the mevalonate pathway, is a multi-step anabolic process that converts acetyl-CoA, derived from carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism, into cholesterol primarily within eukaryotic cells. This pathway, elucidated through pioneering work in the mid-20th century, involves over 20 enzymatic reactions and produces not only cholesterol but also isoprenoid intermediates essential for other cellular functions. The process is highly conserved across mammals and occurs predominantly in the liver and small intestine, though all nucleated cells possess the capability for de novo synthesis.[1][45] The pathway begins in the cytosol with the condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA to form acetoacetyl-CoA, catalyzed by the enzyme acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (thiolase). A third acetyl-CoA molecule is then added by HMG-CoA synthase to produce 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA). The subsequent reduction of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, the committed step of the pathway, is mediated by the rate-limiting enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which utilizes two molecules of NADPH as cofactors and occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. Mevalonate is then sequentially phosphorylated and decarboxylated in the cytosol by mevalonate kinase, phosphomevalonate kinase, and diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase to yield the five-carbon isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), the universal isoprenoid building block.[46][45][1] IPP isomerizes to dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), which condenses with another IPP to form geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP, C10), and GPP further condenses with IPP to produce farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP, C15) via farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase. Two FPP molecules then combine head-to-head, catalyzed by squalene synthase in the ER, to generate the linear 30-carbon squalene, with the release of two pyrophosphate groups. Squalene is epoxidized by squalene monooxygenase to 2,3-oxidosqualene, which undergoes cyclization by lanosterol synthase to form lanosterol, the first sterol intermediate. The conversion from lanosterol to cholesterol involves approximately 19 steps, including demethylations, isomerizations, and reductions, primarily via the Bloch pathway in most tissues or the Kandutsch-Russell pathway in others; these reactions, executed by cytochrome P450 enzymes and reductases like 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase, occur in the ER and remove three methyl groups while adjusting double bond positions.[46][45][47] The overall stoichiometry of the pathway reflects its complexity, requiring 18 molecules of acetyl-CoA, 18 ATP, and 16 NADPH to construct the 27-carbon cholesterol molecule, with significant energy and reducing power input and the release of byproducts like CO₂. The liver and small intestine together account for about 80% of total body cholesterol synthesis due to their high enzyme expression, but extrahepatic tissues contribute the remainder to meet local demands.[1][46]Enzymatic Regulation and Feedback Mechanisms