Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Atom | |

|---|---|

An illustration of the helium atom, depicting the nucleus (pink) and the electron cloud distribution (black). The nucleus (upper right) in helium-4 is in reality spherically symmetric and closely resembles the electron cloud, although for more complicated nuclei this is not always the case. The black bar is one angstrom (10−10 m or 100 pm). | |

| Classification | |

| Smallest recognized division of a chemical element | |

| Properties | |

| Mass range | 1.67×10−27 to 4.52×10−25 kg |

| Electric charge | zero (neutral), or ion charge |

| Diameter range | 62 pm (He) to 520 pm (Cs) (data page) |

| Components | Electrons and a compact nucleus of protons and neutrons |

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements and the fundamental building blocks of matter. An atom consists of a nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished from each other by the number of protons that are in their atoms. For example, any atom that contains 11 protons is sodium, and any atom that contains 29 protons is copper. Atoms with the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons are called isotopes of the same element.

Atoms are extremely small, typically around 100 picometers across. A human hair is about a million carbon atoms wide. Atoms are smaller than the shortest wavelength of visible light, which means humans cannot see atoms with conventional microscopes. They are so small that accurately predicting their behavior using classical physics is not possible due to quantum effects.

More than 99.94%[1] of an atom's mass is in the nucleus. Protons have a positive electric charge and neutrons have no charge, so the nucleus is positively charged. The electrons are negatively charged, and this opposing charge is what binds them to the nucleus. If the numbers of protons and electrons are equal, as they normally are, then the atom is electrically neutral as a whole. A charged atom is called an ion. If an atom has more electrons than protons, then it has an overall negative charge and is called a negative ion (or anion). Conversely, if it has more protons than electrons, it has a positive charge and is called a positive ion (or cation).

The electrons of an atom are attracted to the protons in an atomic nucleus by the electromagnetic force. The protons and neutrons in the nucleus are attracted to each other by the nuclear force. This force is usually stronger than the electromagnetic force that repels the positively charged protons from one another. Under certain circumstances, the repelling electromagnetic force becomes stronger than the nuclear force. In this case, the nucleus splits and leaves behind different elements. This is a form of nuclear decay.

Atoms can attach to one or more other atoms by chemical bonds to form chemical compounds such as molecules or crystals. The ability of atoms to attach and detach from each other is responsible for most of the physical changes observed in nature. Chemistry is the science that studies these changes.

History of atomic theory

[edit]In philosophy

[edit]The basic idea that matter is made up of tiny indivisible particles is an old idea that appeared in many ancient cultures. The word atom is derived from the ancient Greek word atomos,[a] which means "uncuttable". But this ancient idea was based in philosophical reasoning rather than scientific reasoning. Modern atomic theory is not based on these old concepts.[2][3] In the early 19th century, the scientist John Dalton found evidence that matter really is composed of discrete units, and so applied the word atom to those units.[4]

Dalton's law of multiple proportions

[edit]

In the early 1800s, John Dalton compiled experimental data gathered by him and other scientists and discovered a pattern now known as the "law of multiple proportions". He noticed that in any group of chemical compounds which all contain two particular chemical elements, the amount of Element A per measure of Element B will differ across these compounds by ratios of small whole numbers. This pattern suggested that each element combines with other elements in multiples of a basic unit of weight, with each element having a unit of unique weight. Dalton decided to call these units "atoms".[5]

For example, there are two types of tin oxide: one is a grey powder that is 88.1% tin and 11.9% oxygen, and the other is a white powder that is 78.7% tin and 21.3% oxygen. Adjusting these figures, in the grey powder there is about 13.5 g of oxygen for every 100 g of tin, and in the white powder there is about 27 g of oxygen for every 100 g of tin. 13.5 and 27 form a ratio of 1:2. Dalton concluded that in the grey oxide there is one atom of oxygen for every atom of tin, and in the white oxide there are two atoms of oxygen for every atom of tin (SnO and SnO2).[6][7]

Dalton also analyzed iron oxides. There is one type of iron oxide that is a black powder which is 78.1% iron and 21.9% oxygen; and there is another iron oxide that is a red powder which is 70.4% iron and 29.6% oxygen. Adjusting these figures, in the black powder there is about 28 g of oxygen for every 100 g of iron, and in the red powder there is about 42 g of oxygen for every 100 g of iron. 28 and 42 form a ratio of 2:3. Dalton concluded that in these oxides, for every two atoms of iron, there are two or three atoms of oxygen respectively. These substances are known today as iron(II) oxide and iron(III) oxide, and their formulas are FeO and Fe2O3 respectively. Iron(II) oxide's formula is normally written as FeO, but since it is a crystalline substance we could alternately write it as Fe2O2, and when we contrast that with Fe2O3, the 2:3 ratio for the oxygen is plain to see.[8][9]

As a final example: nitrous oxide is 63.3% nitrogen and 36.7% oxygen, nitric oxide is 44.05% nitrogen and 55.95% oxygen, and nitrogen dioxide is 29.5% nitrogen and 70.5% oxygen. Adjusting these figures, in nitrous oxide there is 80 g of oxygen for every 140 g of nitrogen, in nitric oxide there is about 160 g of oxygen for every 140 g of nitrogen, and in nitrogen dioxide there is 320 g of oxygen for every 140 g of nitrogen. 80, 160, and 320 form a ratio of 1:2:4. The respective formulas for these oxides are N2O, NO, and NO2.[10][11]

Discovery of the electron

[edit]In 1897, J. J. Thomson discovered that cathode rays can be deflected by electric and magnetic fields, which meant that cathode rays are not a form of light but made of electrically charged particles, and their charge was negative given the direction the particles were deflected in.[12] He measured these particles to be 1,700 times lighter than hydrogen (the lightest atom).[13] He called these new particles corpuscles but they were later renamed electrons since these are the particles that carry electricity.[14] Thomson also showed that electrons were identical to particles given off by photoelectric and radioactive materials.[15] Thomson explained that an electric current is the passing of electrons from one atom to the next, and when there was no current the electrons embedded themselves in the atoms. This in turn meant that atoms were not indivisible as scientists thought. The atom was composed of electrons whose negative charge was balanced out by some source of positive charge to create an electrically neutral atom. Ions, Thomson explained, must be atoms which have an excess or shortage of electrons.[16]

Discovery of the nucleus

[edit]

The electrons in the atom logically had to be balanced out by a commensurate amount of positive charge, but Thomson had no idea where this positive charge came from, so he tentatively proposed that it was everywhere in the atom, the atom being in the shape of a sphere. This was the mathematically simplest hypothesis to fit the available evidence, or lack thereof. Following from this, Thomson imagined that the balance of electrostatic forces would distribute the electrons throughout the sphere in a more or less even manner.[17] Thomson's model is popularly known as the plum pudding model, though neither Thomson nor his colleagues used this analogy.[18] Thomson's model was incomplete, it was unable to predict any other properties of the elements such as emission spectra and valencies. It was soon rendered obsolete by the discovery of the atomic nucleus.

Between 1908 and 1913, Ernest Rutherford and his colleagues Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden performed a series of experiments in which they bombarded thin foils of metal with a beam of alpha particles. They did this to measure the scattering patterns of the alpha particles. They spotted a small number of alpha particles being deflected by angles greater than 90°. This shouldn't have been possible according to the Thomson model of the atom, whose charges were too diffuse to produce a sufficiently strong electric field. The deflections should have all been negligible. Rutherford proposed that the positive charge of the atom is concentrated in a tiny volume at the center of the atom and that the electrons surround this nucleus in a diffuse cloud. This nucleus carried almost all of the atom's mass. Only such an intense concentration of charge, anchored by its high mass, could produce an electric field that could deflect the alpha particles so strongly.[19]

Bohr model

[edit]

A problem in classical mechanics is that an accelerating charged particle radiates electromagnetic radiation, causing the particle to lose kinetic energy. Circular motion counts as acceleration, which means that an electron orbiting a central charge should spiral down into that nucleus as it loses speed. In 1913, the physicist Niels Bohr proposed a new model in which the electrons of an atom were assumed to orbit the nucleus but could only do so in a finite set of orbits, and could jump between these orbits only in discrete changes of energy corresponding to absorption or radiation of a photon.[20] This quantization was used to explain why the electrons' orbits are stable and why elements absorb and emit electromagnetic radiation in discrete spectra.[21] Bohr's model could only predict the emission spectra of hydrogen, not atoms with more than one electron.

Discovery of protons and neutrons

[edit]Back in 1815, William Prout observed that the atomic weights of many elements were multiples of hydrogen's atomic weight, which is in fact true for all of them if one takes isotopes into account. In 1898, J. J. Thomson found that the positive charge of a hydrogen ion is equal to the negative charge of an electron, and these were then the smallest known charged particles.[22] Thomson later found that the positive charge in an atom is a positive multiple of an electron's negative charge.[23] In 1913, Henry Moseley discovered that the frequencies of X-ray emissions from an excited atom were a mathematical function of its atomic number and hydrogen's nuclear charge. In 1919, Rutherford bombarded nitrogen gas with alpha particles and detected hydrogen ions being emitted from the gas, and concluded that they were produced by alpha particles hitting and splitting the nuclei of the nitrogen atoms.[24]

These observations led Rutherford to conclude that the hydrogen nucleus is a singular particle with a positive charge equal to the electron's negative charge.[25] He named this particle "proton" in 1920.[26] The number of protons in an atom (which Rutherford called the "atomic number"[27][28]) was found to be equal to the element's ordinal number on the periodic table and therefore provided a simple and clear-cut way of distinguishing the elements from each other. The atomic weight of each element is higher than its proton number, so Rutherford hypothesized that the surplus weight was carried by unknown particles with no electric charge and a mass equal to that of the proton.

In 1928, Walter Bothe observed that beryllium emitted a highly penetrating, electrically neutral radiation when bombarded with alpha particles. It was later discovered that this radiation could knock hydrogen atoms out of paraffin wax. Initially it was thought to be high-energy gamma radiation, since gamma radiation had a similar effect on electrons in metals, but James Chadwick found that the ionization effect was too strong for it to be due to electromagnetic radiation, so long as energy and momentum were conserved in the interaction. In 1932, Chadwick exposed various elements, such as hydrogen and nitrogen, to the mysterious "beryllium radiation", and by measuring the energies of the recoiling charged particles, he deduced that the radiation was actually composed of electrically neutral particles which could not be massless like the gamma ray, but instead were required to have a mass similar to that of a proton. Chadwick now claimed these particles as Rutherford's neutrons.[29]

The current consensus model

[edit]

In 1925, Werner Heisenberg published the first consistent mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics (matrix mechanics).[30] One year earlier, Louis de Broglie had proposed that all particles behave like waves to some extent,[31] and in 1926 Erwin Schrödinger used this idea to develop the Schrödinger equation, which describes electrons as three-dimensional waveforms rather than points in space.[32] A consequence of using waveforms to describe particles is that it is mathematically impossible to obtain precise values for both the position and momentum of a particle at a given point in time. This became known as the uncertainty principle, formulated by Werner Heisenberg in 1927.[30] In this concept, for a given accuracy in measuring a position one could only obtain a range of probable values for momentum, and vice versa.[33] Thus, the planetary model of the atom was discarded in favor of one that described atomic orbital zones around the nucleus where a given electron is most likely to be found.[34][35] This model was able to explain observations of atomic behavior that previous models could not, such as certain structural and spectral patterns of atoms larger than hydrogen.

Structure

[edit]Subatomic particles

[edit]Though the word atom originally denoted a particle that cannot be cut into smaller particles, in modern scientific usage the atom is composed of various subatomic particles. The constituent particles of an atom are the electron, the proton, and the neutron.

The electron is the least massive of these particles by four orders of magnitude at 9.11×10−31 kg, with a negative electrical charge and a size that is too small to be measured using available techniques.[36] It was the lightest particle with a positive rest mass measured, until the discovery of neutrino mass. Under ordinary conditions, electrons are bound to the positively charged nucleus by the attraction created from opposite electric charges. Electrons have been known since the late 19th century, mostly thanks to J.J. Thomson; see history of subatomic physics for details.

Protons have a positive charge and a mass of 1.6726×10−27 kg. The number of protons in an atom is called its atomic number. Ernest Rutherford (1919) observed that nitrogen under alpha-particle bombardment ejects what appeared to be hydrogen nuclei. By 1920 he had accepted that the hydrogen nucleus is a distinct particle within the atom and named it proton.

Neutrons have no electrical charge and have a mass of 1.6749×10−27 kg.[37][38] Neutrons are the heaviest of the three constituent particles, but their mass can be reduced by the nuclear binding energy. Neutrons and protons (collectively known as nucleons) have comparable dimensions—on the order of 2.5×10−15 m—although the 'surface' of these particles is not sharply defined.[39] The neutron was discovered in 1932 by the English physicist James Chadwick.

In the Standard Model of physics, electrons are truly elementary particles with no internal structure, whereas protons and neutrons are composite particles composed of elementary particles called quarks. There are two types of quarks in atoms, each having a fractional electric charge. Protons are composed of two up quarks (each with charge +2/3) and one down quark (with a charge of −1/3). Neutrons consist of one up quark and two down quarks. This distinction accounts for the difference in mass and charge between the two particles.[40][41]

The quarks are held together by the strong interaction (or strong force), which is mediated by gluons. The protons and neutrons, in turn, are held to each other in the nucleus by the nuclear force, which is a residuum of the strong force that has somewhat different range-properties (see the article on the nuclear force for more). The gluon is a member of the family of gauge bosons, which are elementary particles that mediate physical forces.[40][41]

Nucleus

[edit]

All the bound protons and neutrons in an atom make up a tiny atomic nucleus, and are collectively called nucleons. The radius of a nucleus is approximately equal to femtometres, where is the total number of nucleons.[42] This is much smaller than the radius of the atom, which is on the order of 105 fm. The nucleons are bound together by a short-ranged attractive potential called the residual strong force. At distances smaller than 2.5 fm this force is much more powerful than the electrostatic force that causes positively charged protons to repel each other.[43]

Atoms of the same element have the same number of protons, called the atomic number. Within a single element, the number of neutrons may vary, determining the isotope of that element. The total number of protons and neutrons determine the nuclide. The number of neutrons relative to the protons determines the stability of the nucleus, with certain isotopes undergoing radioactive decay.[44]

The proton, the electron, and the neutron are classified as fermions. Fermions obey the Pauli exclusion principle which prohibits identical fermions, such as multiple protons, from occupying the same quantum state at the same time. Thus, every proton in the nucleus must occupy a quantum state different from all other protons, and the same applies to all neutrons of the nucleus and to all electrons of the electron cloud.[45]

A nucleus that has a different number of protons than neutrons can potentially drop to a lower energy state through a radioactive decay that causes the number of protons and neutrons to more closely match. As a result, atoms with matching numbers of protons and neutrons are more stable against decay, but with increasing atomic number, the mutual repulsion of the protons requires an increasing proportion of neutrons to maintain the stability of the nucleus.[45]

The number of protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus can be modified, although this can require very high energies because of the strong force. Nuclear fusion occurs when multiple atomic particles join to form a heavier nucleus, such as through the energetic collision of two nuclei. For example, at the core of the Sun protons require energies of 3 to 10 keV to overcome their mutual repulsion—the coulomb barrier—and fuse together into a single nucleus.[46] Nuclear fission is the opposite process, causing a nucleus to split into two smaller nuclei—usually through radioactive decay. The nucleus can also be modified through bombardment by high energy subatomic particles or photons. If this modifies the number of protons in a nucleus, the atom changes to a different chemical element.[47][48]

If the mass of the nucleus following a fusion reaction is less than the sum of the masses of the separate particles, then the difference between these two values can be emitted as a type of usable energy (such as a gamma ray, or the kinetic energy of a beta particle), as described by Albert Einstein's mass–energy equivalence formula, E = mc2, where m is the mass loss and c is the speed of light. This deficit is part of the binding energy of the new nucleus, and it is the non-recoverable loss of the energy that causes the fused particles to remain together in a state that requires this energy to separate.[49]

The fusion of two nuclei that create larger nuclei with lower atomic numbers than iron and nickel—a total nucleon number of about 60—is usually an exothermic process that releases more energy than is required to bring them together.[50] It is this energy-releasing process that makes nuclear fusion in stars a self-sustaining reaction. For heavier nuclei, the binding energy per nucleon begins to decrease. That means that a fusion process producing a nucleus that has an atomic number higher than about 26, and a mass number higher than about 60, is an endothermic process. Thus, more massive nuclei cannot undergo an energy-producing fusion reaction that can sustain the hydrostatic equilibrium of a star.[45]

Electron cloud

[edit]

The electrons in an atom are attracted to the protons in the nucleus by the electromagnetic force. This force binds the electrons inside an electrostatic potential well surrounding the smaller nucleus, which means that an external source of energy is needed for the electron to escape. The closer an electron is to the nucleus, the greater the attractive force. Hence electrons bound near the center of the potential well require more energy to escape than those at greater separations.

Electrons, like other particles, have properties of both a particle and a wave. The electron cloud is a region inside the potential well where each electron forms a type of three-dimensional standing wave—a wave form that does not move relative to the nucleus. This behavior is defined by an atomic orbital, a mathematical function that characterises the probability that an electron appears to be at a particular location when its position is measured.[51] Only a discrete (or quantized) set of these orbitals exist around the nucleus, as other possible wave patterns rapidly decay into a more stable form.[52] Orbitals can have one or more ring or node structures, and differ from each other in size, shape and orientation.[53]

Each atomic orbital corresponds to a particular energy level of the electron. The electron can change its state to a higher energy level by absorbing a photon with sufficient energy to boost it into the new quantum state. Likewise, through spontaneous emission, an electron in a higher energy state can drop to a lower energy state while radiating the excess energy as a photon. These characteristic energy values, defined by the differences in the energies of the quantum states, are responsible for atomic spectral lines.[52]

The amount of energy needed to remove or add an electron—the electron binding energy—is far less than the binding energy of nucleons. For example, it requires only 13.6 eV to strip a ground-state electron from a hydrogen atom,[54] compared to 2.23 million eV for splitting a deuterium nucleus.[55] Atoms are electrically neutral if they have an equal number of protons and electrons. Atoms that have either a deficit or a surplus of electrons are called ions. Electrons that are farthest from the nucleus may be transferred to other nearby atoms or shared between atoms. By this mechanism, atoms are able to bond into molecules and other types of chemical compounds like ionic and covalent network crystals.[56]

Properties

[edit]Nuclear properties

[edit]By definition, any two atoms with an identical number of protons in their nuclei belong to the same chemical element. Atoms with equal numbers of protons but a different number of neutrons are different isotopes of the same element. For example, all hydrogen atoms admit exactly one proton, but isotopes exist with no neutrons (hydrogen-1, by far the most common form,[57] also called protium), one neutron (deuterium), two neutrons (tritium) and more than two neutrons. The known elements form a set of atomic numbers, from the single-proton element hydrogen up to the 118-proton element oganesson.[58] All known isotopes of elements with atomic numbers greater than 82 are radioactive, although the radioactivity of element 83 (bismuth) is so slight as to be practically negligible.[59][60]

About 339 nuclides occur naturally on Earth,[61] of which 251 (about 74%) have not been observed to decay, and are referred to as "stable isotopes". Only 90 nuclides are stable theoretically, while another 161 (bringing the total to 251) have not been observed to decay, even though in theory it is energetically possible. These are also formally classified as "stable". An additional 35 radioactive nuclides have half-lives longer than 100 million years, and are long-lived enough to have been present since the birth of the Solar System. This collection of 286 nuclides are known as primordial nuclides. Finally, an additional 53 short-lived nuclides are known to occur naturally, as daughter products of primordial nuclide decay (such as radium from uranium), or as products of natural energetic processes on Earth, such as cosmic ray bombardment (for example, carbon-14).[62][note 1]

For 80 of the chemical elements, at least one stable isotope exists. As a rule, there is only a handful of stable isotopes for each of these elements, the average being 3.1 stable isotopes per element. Twenty-six "monoisotopic elements" have only a single stable isotope, while the largest number of stable isotopes observed for any element is ten, for the element tin. Elements 43, 61, and all elements numbered 83 or higher have no stable isotopes.[63]: 1–12

Stability of isotopes is affected by the ratio of protons to neutrons, and also by the presence of certain "magic numbers" of neutrons or protons that represent closed and filled quantum shells. These quantum shells correspond to a set of energy levels within the shell model of the nucleus; filled shells, such as the filled shell of 50 protons for tin, confers unusual stability on the nuclide. Of the 251 known stable nuclides, only four have both an odd number of protons and odd number of neutrons: hydrogen-2 (deuterium), lithium-6, boron-10, and nitrogen-14. (Tantalum-180m is odd-odd and observationally stable, but is predicted to decay with a very long half-life.) Also, only four naturally occurring, radioactive odd-odd nuclides have a half-life over a billion years: potassium-40, vanadium-50, lanthanum-138, and lutetium-176. Most odd-odd nuclei are highly unstable with respect to beta decay, because the decay products are even-even, and are therefore more strongly bound, due to nuclear pairing effects.[64]

Mass

[edit]The large majority of an atom's mass comes from the protons and neutrons that make it up. The total number of these particles (called "nucleons") in a given atom is called the mass number. It is a positive integer and dimensionless (instead of having dimension of mass), because it expresses a count. An example of use of a mass number is "carbon-12," which has 12 nucleons (six protons and six neutrons).

The actual mass of an atom at rest is often expressed in daltons (Da), also called the unified atomic mass unit (u). This unit is defined as a twelfth of the mass of a free neutral atom of carbon-12, which is approximately 1.66×10−27 kg.[65] Hydrogen-1 (the lightest isotope of hydrogen which is also the nuclide with the lowest mass) has an atomic weight of 1.007825 Da.[66] The value of this number is called the atomic mass. A given atom has an atomic mass approximately equal (within 1%) to its mass number times the dalton (for example the mass of a nitrogen-14 is roughly 14 Da), but this number will not be exactly an integer except (by definition) in the case of carbon-12.[67] The heaviest stable atom is lead-208,[59] with a mass of 207.9766521 Da.[68]

As even the most massive atoms are far too light to work with directly, chemists instead use the unit of moles. One mole of atoms of any element always has the same number of atoms (about 6.022×1023). This number was chosen so that if an element has an atomic mass of 1 u, a mole of atoms of that element has a mass close to one gram. Because of the definition of the dalton, each carbon-12 atom has an atomic mass of exactly 12 Da, and so a mole of carbon-12 atoms weighs exactly 0.012 kg.[65]

Shape and size

[edit]Atoms lack a well-defined outer boundary, so their dimensions are usually described in terms of an atomic radius. This is a measure of the distance out to which the electron cloud extends from the nucleus.[69] This assumes the atom to exhibit a spherical shape, which is only obeyed for atoms in vacuum or free space. Atomic radii may be derived from the distances between two nuclei when the two atoms are joined in a chemical bond. The radius varies with the location of an atom on the atomic chart, the type of chemical bond, the number of neighboring atoms (coordination number) and a quantum mechanical property known as spin.[70] On the periodic table of the elements, atom size tends to increase when moving down columns, but decrease when moving across rows (left to right).[71] Consequently, the smallest atom is helium with a radius of 32 pm, while one of the largest is caesium at 225 pm.[72]

When subjected to external forces, like electrical fields, the shape of an atom may deviate from spherical symmetry. The deformation depends on the field magnitude and the orbital type of outer shell electrons, as shown by group-theoretical considerations. Aspherical deviations might be elicited for instance in crystals, where large crystal-electrical fields may occur at low-symmetry lattice sites.[73][74] Significant ellipsoidal deformations have been shown to occur for sulfur ions[75] and chalcogen ions[76] in pyrite-type compounds.

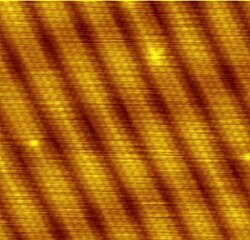

Atomic dimensions are thousands of times smaller than the wavelengths of light (400–700 nm) so they cannot be viewed using an optical microscope, although individual atoms can be observed using a scanning tunneling microscope. To visualize the minuteness of the atom, consider that a typical human hair is about 1 million carbon atoms in width.[77] A single drop of water contains about 2 sextillion (2×1021) atoms of oxygen, and twice the number of hydrogen atoms.[78] A single carat diamond with a mass of 2×10−4 kg contains about 10 sextillion (1022) atoms of carbon.[note 2] If an apple were magnified to the size of the Earth, then the atoms in the apple would be approximately the size of the original apple.[79]

Radioactive decay

[edit]

Every element has one or more isotopes that have unstable nuclei that are subject to radioactive decay, causing the nucleus to emit particles or electromagnetic radiation. Radioactivity can occur when the radius of a nucleus is large compared with the radius of the strong force, which only acts over distances on the order of 1 fm.[80]

The most common forms of radioactive decay are:[81][82]

- Alpha decay: this process is caused when the nucleus emits an alpha particle, which is a helium nucleus consisting of two protons and two neutrons. The result of the emission is a new element with a lower atomic number.

- Beta decay (and electron capture): these processes are regulated by the weak force, and result from a transformation of a neutron into a proton, or a proton into a neutron. The neutron to proton transition is accompanied by the emission of an electron and an antineutrino, while proton to neutron transition (except in electron capture) causes the emission of a positron and a neutrino. The electron or positron emissions are called beta particles. Beta decay either increases or decreases the atomic number of the nucleus by one. Electron capture is more common than positron emission, because it requires less energy. In this type of decay, an electron is absorbed by the nucleus, rather than a positron emitted from the nucleus. A neutrino is still emitted in this process, and a proton changes to a neutron.

- Gamma decay: this process results from a change in the energy level of the nucleus to a lower state, resulting in the emission of electromagnetic radiation. The excited state of a nucleus which results in gamma emission usually occurs following the emission of an alpha or a beta particle. Thus, gamma decay usually follows alpha or beta decay.

Other more rare types of radioactive decay include ejection of neutrons or protons or clusters of nucleons from a nucleus, or more than one beta particle. An analog of gamma emission which allows excited nuclei to lose energy in a different way, is internal conversion—a process that produces high-speed electrons that are not beta rays, followed by production of high-energy photons that are not gamma rays. A few large nuclei explode into two or more charged fragments of varying masses plus several neutrons, in a decay called spontaneous nuclear fission.

Each radioactive isotope has a characteristic decay time period—the half-life—that is determined by the amount of time needed for half of a sample to decay. This is an exponential decay process that steadily decreases the proportion of the remaining isotope by 50% every half-life. Hence after two half-lives have passed only 25% of the isotope is present, and so forth.[80]

Magnetic moment

[edit]Elementary particles possess an intrinsic quantum mechanical property known as spin. This is analogous to the angular momentum of an object that is spinning around its center of mass, although strictly speaking these particles are believed to be point-like and cannot be said to be rotating. Spin is measured in units of the reduced Planck constant (ħ), with electrons, protons and neutrons all having spin 1⁄2 ħ, or "spin-1⁄2". In an atom, electrons in motion around the nucleus possess orbital angular momentum in addition to their spin, while the nucleus itself possesses angular momentum due to its nuclear spin.[83]

The magnetic field produced by an atom—its magnetic moment—is determined by these various forms of angular momentum, just as a rotating charged object classically produces a magnetic field, but the most dominant contribution comes from electron spin. Due to the nature of electrons to obey the Pauli exclusion principle, in which no two electrons may be found in the same quantum state, bound electrons pair up with each other, with one member of each pair in a spin up state and the other in the opposite, spin down state. Thus these spins cancel each other out, reducing the total magnetic dipole moment to zero in some atoms with even number of electrons.[84]

In ferromagnetic elements such as iron, cobalt and nickel, an odd number of electrons leads to an unpaired electron and a net overall magnetic moment. The orbitals of neighboring atoms overlap and a lower energy state is achieved when the spins of unpaired electrons are aligned with each other, a spontaneous process known as an exchange interaction. When the magnetic moments of ferromagnetic atoms are lined up, the material can produce a measurable macroscopic field. Paramagnetic materials have atoms with magnetic moments that line up in random directions when no magnetic field is present, but the magnetic moments of the individual atoms line up in the presence of a field.[84][85]

The nucleus of an atom will have no spin when it has even numbers of both neutrons and protons, but for other cases of odd numbers, the nucleus may have a spin. Normally nuclei with spin are aligned in random directions because of thermal equilibrium, but for certain elements (such as xenon-129) it is possible to polarize a significant proportion of the nuclear spin states so that they are aligned in the same direction—a condition called hyperpolarization. This has important applications in magnetic resonance imaging.[86][87]

Energy levels

[edit]

The potential energy of an electron in an atom is negative relative to when the distance from the nucleus goes to infinity; its dependence on the electron's position reaches the minimum inside the nucleus, roughly in inverse proportion to the distance. In the quantum-mechanical model, a bound electron can occupy only a set of states centered on the nucleus, and each state corresponds to a specific energy level; see time-independent Schrödinger equation for a theoretical explanation. An energy level can be measured by the amount of energy needed to unbind the electron from the atom, and is usually given in units of electronvolts (eV). The lowest energy state of a bound electron is called the ground state, i.e., stationary state, while an electron transition to a higher level results in an excited state.[88] The electron's energy increases along with n because the (average) distance to the nucleus increases. Dependence of the energy on ℓ is caused not by the electrostatic potential of the nucleus, but by interaction between electrons.

For an electron to transition between two different states, e.g. ground state to first excited state, it must absorb or emit a photon at an energy matching the difference in the potential energy of those levels, according to the Niels Bohr model, what can be precisely calculated by the Schrödinger equation. Electrons jump between orbitals in a particle-like fashion. For example, if a single photon strikes the electrons, only a single electron changes states in response to the photon; see Electron properties.

The energy of an emitted photon is proportional to its frequency, so these specific energy levels appear as distinct bands in the electromagnetic spectrum.[89] Each element has a characteristic spectrum that can depend on the nuclear charge, subshells filled by electrons, the electromagnetic interactions between the electrons and other factors.[90]

When a continuous spectrum of energy is passed through a gas or plasma, some of the photons are absorbed by atoms, causing electrons to change their energy level. Those excited electrons that remain bound to their atom spontaneously emit this energy as a photon, traveling in a random direction, and so drop back to lower energy levels. Thus the atoms behave like a filter that forms a series of dark absorption bands in the energy output. An observer viewing the atoms from a view that does not include the continuous spectrum in the background, instead sees a series of emission lines from the photons emitted by the atoms. Spectroscopic measurements of the strength and width of atomic spectral lines allow the composition and physical properties of a substance to be determined.[91]

Close examination of the spectral lines reveals that some display a fine structure splitting. This occurs because of spin–orbit coupling, which is an interaction between the spin and motion of the outermost electron.[92] When an atom is in an external magnetic field, spectral lines become split into three or more components; a phenomenon called the Zeeman effect. This is caused by the interaction of the magnetic field with the magnetic moment of the atom and its electrons. Some atoms can have multiple electron configurations with the same energy level, which thus appear as a single spectral line. The interaction of the magnetic field with the atom shifts these electron configurations to slightly different energy levels, resulting in multiple spectral lines.[93] The presence of an external electric field can cause a comparable splitting and shifting of spectral lines by modifying the electron energy levels, a phenomenon called the Stark effect.[94]

If a bound electron is in an excited state, an interacting photon with the proper energy can cause stimulated emission of a photon with a matching energy level. For this to occur, the electron must drop to a lower energy state that has an energy difference matching the energy of the interacting photon. The emitted photon and the interacting photon then move off in parallel and with matching phases. That is, the wave patterns of the two photons are synchronized. This physical property is used to make lasers, which can emit a coherent beam of light energy in a narrow frequency band.[95]

Valence and bonding behavior

[edit]Valency is the combining power of an element. It is determined by the number of bonds it can form to other atoms or groups.[96] The outermost electron shell of an atom in its uncombined state is known as the valence shell, and the electrons in that shell are called valence electrons. The number of valence electrons determines the bonding behavior with other atoms. Atoms tend to chemically react with each other in a manner that fills (or empties) their outer valence shells.[97] For example, a transfer of a single electron between atoms is a useful approximation for bonds that form between atoms with one-electron more than a filled shell, and others that are one-electron short of a full shell, such as occurs in the compound sodium chloride and other chemical ionic salts. Many elements display multiple valences, or tendencies to share differing numbers of electrons in different compounds. Thus, chemical bonding between these elements takes many forms of electron-sharing that are more than simple electron transfers. Examples include the element carbon and the organic compounds.[98]

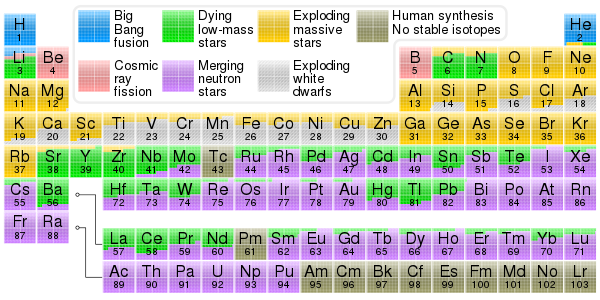

The chemical elements are often displayed in a periodic table that is laid out to display recurring chemical properties, and elements with the same number of valence electrons form a group that is aligned in the same column of the table. (The horizontal rows correspond to the filling of a quantum shell of electrons.) The elements at the far right of the table have their outer shell completely filled with electrons, which results in chemically inert elements known as the noble gases.[99][100]

States

[edit]

Quantities of atoms are found in different states of matter that depend on the physical conditions, such as temperature and pressure. By varying the conditions, materials can transition between solids, liquids, gases, and plasmas.[101] Within a state, a material can also exist in different allotropes. An example of this is solid carbon, which can exist as graphite or diamond.[102] Gaseous allotropes exist as well, such as dioxygen and ozone.

At temperatures close to absolute zero, atoms can form a Bose–Einstein condensate, at which point quantum mechanical effects, which are normally only observed at the atomic scale, become apparent on a macroscopic scale.[103][104] This super-cooled collection of atoms then behaves as a single super atom, which may allow fundamental checks of quantum mechanical behavior.[105]

Identification

[edit]

While atoms are too small to be seen, devices such as the scanning tunneling microscope (STM) enable their visualization at the surfaces of solids. The microscope uses the quantum tunneling phenomenon, which allows particles to pass through a barrier that would be insurmountable in the classical perspective. Electrons tunnel through the vacuum between two biased electrodes, providing a tunneling current that is exponentially dependent on their separation. One electrode is a sharp tip ideally ending with a single atom. At each point of the scan of the surface the tip's height is adjusted so as to keep the tunneling current at a set value. How much the tip moves to and away from the surface is interpreted as the height profile. For low bias, the microscope images the averaged electron orbitals across closely packed energy levels—the local density of the electronic states near the Fermi level.[106][107] Because of the distances involved, both electrodes need to be extremely stable; only then periodicities can be observed that correspond to individual atoms. The method alone is not chemically specific, and cannot identify the atomic species present at the surface.

Atoms can be easily identified by their mass. If an atom is ionized by removing one of its electrons, its trajectory when it passes through a magnetic field will bend. The radius by which the trajectory of a moving ion is turned by the magnetic field is determined by the mass of the atom. The mass spectrometer uses this principle to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. If a sample contains multiple isotopes, the mass spectrometer can determine the proportion of each isotope in the sample by measuring the intensity of the different beams of ions. Techniques to vaporize atoms include inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, both of which use a plasma to vaporize samples for analysis.[108]

The atom-probe tomograph has sub-nanometer resolution in 3-D and can chemically identify individual atoms using time-of-flight mass spectrometry.[109]

Electron emission techniques such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Auger electron spectroscopy (AES), which measure the binding energies of the core electrons, are used to identify the atomic species present in a sample in a non-destructive way. With proper focusing both can be made area-specific. Another such method is electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), which measures the energy loss of an electron beam within a transmission electron microscope when it interacts with a portion of a sample.

Spectra of excited states can be used to analyze the atomic composition of distant stars. Specific light wavelengths contained in the observed light from stars can be separated out and related to the quantized transitions in free gas atoms. These colors can be replicated using a gas-discharge lamp containing the same element.[110] Helium was discovered in this way in the spectrum of the Sun 23 years before it was found on Earth.[111]

Origin and current state

[edit]Baryonic matter forms about 4% of the total energy density of the observable universe, with an average density of about 0.25 particles/m3 (mostly protons and electrons).[112] Within a galaxy such as the Milky Way, particles have a much higher concentration, with the density of matter in the interstellar medium (ISM) ranging from 105 to 109 atoms/m3.[113] The Sun is believed to be inside the Local Bubble, so the density in the solar neighborhood is only about 103 atoms/m3.[114] Stars form from dense clouds in the ISM, and the evolutionary processes of stars result in the steady enrichment of the ISM with elements more massive than hydrogen and helium.

Up to 95% of the Milky Way's baryonic matter are concentrated inside stars, where conditions are unfavorable for atomic matter. The total baryonic mass is about 10% of the mass of the galaxy;[115] the remainder of the mass is an unknown dark matter.[116] High temperature inside stars makes most "atoms" fully ionized, that is, separates all electrons from the nuclei. In stellar remnants—with exception of their surface layers—an immense pressure make electron shells impossible.

Formation

[edit]

Electrons are thought to exist in the Universe since early stages of the Big Bang. Atomic nuclei forms in nucleosynthesis reactions. In about three minutes Big Bang nucleosynthesis produced most of the helium, lithium, and deuterium in the Universe, and perhaps some of the beryllium and boron.[117][118][119]

Ubiquitousness and stability of atoms relies on their binding energy, which means that an atom has a lower energy than an unbound system of the nucleus and electrons. Where the temperature is much higher than ionization potential, the matter exists in the form of plasma—a gas of positively charged ions (possibly, bare nuclei) and electrons. When the temperature drops below the ionization potential, atoms become statistically favorable. Atoms (complete with bound electrons) became to dominate over charged particles 380,000 years after the Big Bang—an epoch called recombination, when the expanding Universe cooled enough to allow electrons to become attached to nuclei.[120]

Since the Big Bang, which produced no carbon or heavier elements, atomic nuclei have been combined in stars through the process of nuclear fusion to produce more of the element helium, and (via the triple-alpha process) the sequence of elements from carbon up to iron;[121] see stellar nucleosynthesis for details.

Isotopes such as lithium-6, as well as some beryllium and boron are generated in space through cosmic ray spallation.[122] This occurs when a high-energy proton strikes an atomic nucleus, causing large numbers of nucleons to be ejected.

Elements heavier than iron were produced in supernovae and colliding neutron stars through the r-process, and in AGB stars through the s-process, both of which involve the capture of neutrons by atomic nuclei.[123] Elements such as lead formed largely through the radioactive decay of heavier elements.[124]

Earth

[edit]Most of the atoms that make up the Earth and its inhabitants were present in their current form in the nebula that collapsed out of a molecular cloud to form the Solar System. The rest are the result of radioactive decay, and their relative proportion can be used to determine the age of the Earth through radiometric dating.[125][126] Most of the helium in the crust of the Earth (about 99% of the helium from gas wells, as shown by its lower abundance of helium-3) is a product of alpha decay.[127]

There are a few trace atoms on Earth that were not present at the beginning (i.e., not "primordial"), nor are results of radioactive decay. Carbon-14 is continuously generated by cosmic rays in the atmosphere.[128] Some atoms on Earth have been artificially generated either deliberately or as by-products of nuclear reactors or explosions.[129][130] Of the transuranic elements—those with atomic numbers greater than 92—only plutonium and neptunium occur naturally on Earth.[131][132] Transuranic elements have radioactive lifetimes shorter than the current age of the Earth[133] and thus identifiable quantities of these elements have long since decayed, with the exception of traces of plutonium-244 possibly deposited by cosmic dust.[125] Natural deposits of plutonium and neptunium are produced by neutron capture in uranium ore.[134]

The Earth contains approximately 1.33×1050 atoms.[135] Although small numbers of independent atoms of noble gases exist, such as argon, neon, and helium, 99% of the atmosphere is bound in the form of molecules, including carbon dioxide and diatomic oxygen and nitrogen. At the surface of the Earth, an overwhelming majority of atoms combine to form various compounds, including water, salt, silicates, and oxides. Atoms can also combine to create materials that do not consist of discrete molecules, including crystals and liquid or solid metals.[136][137] This atomic matter forms networked arrangements that lack the particular type of small-scale interrupted order associated with molecular matter.[138]

Rare and theoretical forms

[edit]Superheavy elements

[edit]All nuclides with atomic numbers higher than 82 (lead) are known to be radioactive. No nuclide with an atomic number exceeding 92 (uranium) exists on Earth as a primordial nuclide, and heavier elements generally have shorter half-lives. Nevertheless, an "island of stability" encompassing relatively long-lived isotopes of superheavy elements[139] with atomic numbers 110 to 114 might exist.[140] Predictions for the half-life of the most stable nuclide on the island range from a few minutes to millions of years.[141] In any case, superheavy elements (with Z > 104) would not exist due to increasing Coulomb repulsion (which results in spontaneous fission with increasingly short half-lives) in the absence of any stabilizing effects.[142]

Exotic matter

[edit]Each particle of matter has a corresponding antimatter particle with the opposite electrical charge. Thus, the positron is a positively charged antielectron and the antiproton is a negatively charged equivalent of a proton. When a matter and corresponding antimatter particle meet, they annihilate each other. Because of this, along with an imbalance between the number of matter and antimatter particles, the latter are rare in the universe. The first causes of this imbalance are not yet fully understood, although theories of baryogenesis may offer an explanation. As a result, no antimatter atoms have been discovered in nature.[143][144] In 1996, the antimatter counterpart of the hydrogen atom (antihydrogen) was synthesized at the CERN laboratory in Geneva.[145][146]

Other exotic atoms have been created by replacing one of the protons, neutrons or electrons with other particles that have the same charge. For example, an electron can be replaced by a more massive muon, forming a muonic atom. These types of atoms can be used to test fundamental predictions of physics.[147][148][149]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For more recent updates see Brookhaven National Laboratory's Interactive Chart of Nuclides Archived 25 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ A carat is 200 milligrams.

- ^ a combination of the negative term "a-" and "τομή" (tomḗ), the term for "cut"

References

[edit]- ^ Edwards, Vennie (2018). Electron Theory. EDTECH. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-83947-382-1.

- ^ Pullman, Bernard (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Melsen (1952). From Atomos to Atom, pp. 18–19

- ^ Pullman (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought, p. 201

- ^ Pullman (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought, p. 199: "The constant ratios, expressible in terms of integers, of the weights of the constituents in composite bodies could be construed as evidence on a macroscopic scale of interactions at the microscopic level between basic units with fixed weights. For Dalton, this agreement strongly suggested a corpuscular structure of matter, even though it did not constitute definite proof."

- ^ Dalton (1817). A New System of Chemical Philosophy vol. 2, p. 36

- ^ Melsen (1952). From Atomos to Atom, p. 137

- ^ Dalton (1817). A New System of Chemical Philosophy vol. 2, p. 28

- ^ Millington (1906). John Dalton, p. 113

- ^ Dalton (1808). A New System of Chemical Philosophy vol. 1, pp. 316–319

- ^ Holbrow et al. (2010). Modern Introductory Physics, pp. 65–66

- ^ J. J. Thomson (1897). "Cathode rays". Philosophical Magazine. 44 (269): 293–316.

- ^ In his book The Corpuscular Theory of Matter (1907), Thomson estimates electrons to be 1/1700 the mass of hydrogen.

- ^ "The Mechanism Of Conduction In Metals" Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Think Quest.

- ^ Thomson, J.J. (August 1901). "On bodies smaller than atoms". The Popular Science Monthly: 323–335. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ J. J. Thomson (1907). On the Corpuscular Theory of Matter, p. 26: "The simplest interpretation of these results is that the positive ions are the atoms or groups of atoms of various elements from which one or more corpuscles have been removed [...] while the negative electrified body is one with more corpuscles than the unelectrified one."

- ^ J. J. Thomson (1907). The Corpuscular Theory of Matter, p. 103: "In default of exact knowledge of the nature of the way in which positive electricity occurs in the atom, we shall consider a case in which the positive electricity is distributed in the way most amenable to mathematical calculation, i.e., when it occurs as a sphere of uniform density, throughout which the corpuscles are distributed."

- ^ Giora Hon; Bernard R. Goldstein (6 September 2013). "J. J. Thomson's plum-pudding atomic model: The making of a scientific myth". Annalen der Physik. 525 (8–9): A129 – A133. Bibcode:2013AnP...525A.129H. doi:10.1002/andp.201300732. ISSN 0003-3804.

- ^ Heilbron (2003). Ernest Rutherford and the Explosion of Atoms, pp. 64–68

- ^ Stern, David P. (16 May 2005). "The Atomic Nucleus and Bohr's Early Model of the Atom". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007.

- ^ Bohr, Niels (11 December 1922). "Niels Bohr, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922, Nobel Lecture". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008.

- ^ J. J. Thomson (1898). "On the Charge of Electricity carried by the Ions produced by Röntgen Rays". The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 5. 46 (283): 528–545. doi:10.1080/14786449808621229.

- ^ J. J. Thomson (1907). The Corpuscular Theory of Matter. p. 26–27: "In an unelectrified atom there are as many units of positive electricity as there are of negative; an atom with a unit of positive charge is a neutral atom which has lost one corpuscle, while an atom with a unit of negative charge is a neutral atom to which an additional corpuscle has been attached."

- ^ Rutherford, Ernest (1919). "Collisions of alpha Particles with Light Atoms. IV. An Anomalous Effect in Nitrogen". Philosophical Magazine. 37 (222): 581. doi:10.1080/14786440608635919.

- ^ The Development of the Theory of Atomic Structure (Rutherford 1936). Reprinted in Background to Modern Science: Ten Lectures at Cambridge arranged by the History of Science Committee 1936:

"In 1919 I showed that when light atoms were bombarded by α-particles they could be broken up with the emission of a proton, or hydrogen nucleus. We therefore presumed that a proton must be one of the units of which the nuclei of other atoms were composed..." - ^ Orme Masson (1921). "The Constitution of Atoms". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 41 (242): 281–285. doi:10.1080/14786442108636219.

Footnote by Ernest Rutherford: 'At the time of writing this paper in Australia, Professor Orme Masson was not aware that the name "proton" had already been suggested as a suitable name for the unit of mass nearly 1, in terms of oxygen 16, that appears to enter into the nuclear structure of atoms. The question of a suitable name for this unit was discussed at an informal meeting of a number of members of Section A of the British Association at Cardiff this year. The name "baron" suggested by Professor Masson was mentioned, but was considered unsuitable on account of the existing variety of meanings. Finally the name "proton" met with general approval, particularly as it suggests the original term "protyle " given by Prout in his well-known hypothesis that all atoms are built up of hydrogen. The need of a special name for the nuclear unit of mass 1 was drawn attention to by Sir Oliver Lodge at the Sectional meeting, and the writer then suggested the name "proton."' - ^ Eric Scerri (2020). The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance, p. 185

- ^ Helge Kragh (2012). Niels Bohr and the Quantum Atom, p. 33

- ^ James Chadwick (1932). "Possible Existence of a Neutron" (PDF). Nature. 129 (3252): 312. Bibcode:1932Natur.129Q.312C. doi:10.1038/129312a0. S2CID 4076465. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b Pais, Abraham (1986). Inward Bound: Of Matter and Forces in the Physical World. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 228–230. ISBN 978-0-19-851971-3.

- ^ McEvoy, J. P.; Zarate, Oscar (2004). Introducing Quantum Theory. Totem Books. pp. 110–114. ISBN 978-1-84046-577-8.

- ^ Kozłowski, Miroslaw (2019). "The Schrödinger equation A History".

- ^ Chad Orzel (16 September 2014). "What is the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle?". TED-Ed. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015 – via YouTube.

- ^ Brown, Kevin (2007). "The Hydrogen Atom". MathPages. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012.

- ^ Harrison, David M. (2000). "The Development of Quantum Mechanics". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007.

- ^ Demtröder, Wolfgang (2002). Atoms, Molecules and Photons: An Introduction to Atomic- Molecular- and Quantum Physics (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 39–42. ISBN 978-3-540-20631-6. OCLC 181435713.

- ^ Woan, Graham (2000). The Cambridge Handbook of Physics. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-57507-2. OCLC 224032426.

- ^ Mohr, P.J.; Taylor, B.N. and Newell, D.B. (2014), "The 2014 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Web Version 7.0). The database was developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. (2014). National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899.

- ^ MacGregor, Malcolm H. (1992). The Enigmatic Electron. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-0-19-521833-6. OCLC 223372888.

- ^ a b Particle Data Group (2002). "The Particle Adventure". Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Archived from the original on 4 January 2007.

- ^ a b Schombert, James (18 April 2006). "Elementary Particles". University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011.

- ^ Jevremovic, Tatjana (2005). Nuclear Principles in Engineering. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-387-23284-3. OCLC 228384008.

- ^ Pfeffer, Jeremy I.; Nir, Shlomo (2000). Modern Physics: An Introductory Text. Imperial College Press. pp. 330–336. ISBN 978-1-86094-250-1. OCLC 45900880.

- ^ Wenner, Jennifer M. (10 October 2007). "How Does Radioactive Decay Work?". Carleton College. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Raymond, David (7 April 2006). "Nuclear Binding Energies". New Mexico Tech. Archived from the original on 1 December 2002.

- ^ Mihos, Chris (23 July 2002). "Overcoming the Coulomb Barrier". Case Western Reserve University. Archived from the original on 12 September 2006.

- ^ Staff (30 March 2007). "ABC's of Nuclear Science". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006.

- ^ Makhijani, Arjun; Saleska, Scott (2 March 2001). "Basics of Nuclear Physics and Fission". Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Archived from the original on 16 January 2007.

- ^ Shultis, J. Kenneth; Faw, Richard E. (2002). Fundamentals of Nuclear Science and Engineering. CRC Press. pp. 10–17. ISBN 978-0-8247-0834-4. OCLC 123346507.

- ^ Fewell, M.P. (1995). "The atomic nuclide with the highest mean binding energy". American Journal of Physics. 63 (7): 653–658. Bibcode:1995AmJPh..63..653F. doi:10.1119/1.17828.

- ^ Mulliken, Robert S. (1967). "Spectroscopy, Molecular Orbitals, and Chemical Bonding". Science. 157 (3784): 13–24. Bibcode:1967Sci...157...13M. doi:10.1126/science.157.3784.13. PMID 5338306.

- ^ a b Brucat, Philip J. (2008). "The Quantum Atom". University of Florida. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006.

- ^ Manthey, David (2001). "Atomic Orbitals". Orbital Central. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ Herter, Terry (2006). "Lecture 8: The Hydrogen Atom". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012.

- ^ Bell, R.E.; Elliott, L.G. (1950). "Gamma-Rays from the Reaction H1(n,γ)D2 and the Binding Energy of the Deuteron". Physical Review. 79 (2): 282–285. Bibcode:1950PhRv...79..282B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.79.282.

- ^ Smirnov, Boris M. (2003). Physics of Atoms and Ions. Springer. pp. 249–272. ISBN 978-0-387-95550-6.

- ^ Matis, Howard S. (9 August 2000). "The Isotopes of Hydrogen". Guide to the Nuclear Wall Chart. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007.

- ^ Weiss, Rick (17 October 2006). "Scientists Announce Creation of Atomic Element, the Heaviest Yet". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011.

- ^ a b Sills, Alan D. (2003). Earth Science the Easy Way. Barron's Educational Series. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-0-7641-2146-3. OCLC 51543743.

- ^ Dumé, Belle (23 April 2003). "Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay". Physics World. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007.

- ^ Lindsay, Don (30 July 2000). "Radioactives Missing From The Earth". Don Lindsay Archive. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007.

- ^ Tuli, Jagdish K. (April 2005). "Nuclear Wallet Cards". National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011.

- ^ CRC Handbook (2002).

- ^ Krane, K. (1988). Introductory Nuclear Physics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 68. ISBN 978-0-471-85914-7.

- ^ a b Mills, Ian; Cvitaš, Tomislav; Homann, Klaus; Kallay, Nikola; Kuchitsu, Kozo (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Commission on Physiochemical Symbols Terminology and Units, Blackwell Scientific Publications. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-632-03583-0. OCLC 27011505.

- ^ Chieh, Chung (22 January 2001). "Nuclide Stability". University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007.

- ^ "Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ Audi, G.; Wapstra, A.H.; Thibault, C. (2003). "The Ame2003 atomic mass evaluation (II)" (PDF). Nuclear Physics A. 729 (1): 337–676. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729..337A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2005.

- ^ Ghosh, D.C.; Biswas, R. (2002). "Theoretical calculation of Absolute Radii of Atoms and Ions. Part 1. The Atomic Radii". Int. J. Mol. Sci. 3 (11): 87–113. doi:10.3390/i3020087.

- ^ Shannon, R.D. (1976). "Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica A. 32 (5): 751–767. Bibcode:1976AcCrA..32..751S. doi:10.1107/S0567739476001551. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Dong, Judy (1998). "Diameter of an Atom". The Physics Factbook. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007.

- ^ Zumdahl, Steven S. (2002). Introductory Chemistry: A Foundation (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-34342-3. OCLC 173081482. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008.

- ^ Bethe, Hans (1929). "Termaufspaltung in Kristallen". Annalen der Physik. 3 (2): 133–208. Bibcode:1929AnP...395..133B. doi:10.1002/andp.19293950202.

- ^ Birkholz, Mario (1995). "Crystal-field induced dipoles in heteropolar crystals – I. concept". Z. Phys. B. 96 (3): 325–332. Bibcode:1995ZPhyB..96..325B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.424.5632. doi:10.1007/BF01313054. S2CID 122527743.

- ^ Birkholz, M.; Rudert, R. (2008). "Interatomic distances in pyrite-structure disulfides – a case for ellipsoidal modeling of sulfur ions" (PDF). Physica Status Solidi B. 245 (9): 1858–1864. Bibcode:2008PSSBR.245.1858B. doi:10.1002/pssb.200879532. S2CID 97824066. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Birkholz, M. (2014). "Modeling the Shape of Ions in Pyrite-Type Crystals". Crystals. 4 (3): 390–403. Bibcode:2014Cryst...4..390B. doi:10.3390/cryst4030390.

- ^ Staff (2007). "Small Miracles: Harnessing nanotechnology". Oregon State University. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. – describes the width of a human hair as 105 nm and 10 carbon atoms as spanning 1 nm.

- ^

Padilla, Michael J.; Miaoulis, Ioannis; Cyr, Martha (2002). Prentice Hall Science Explorer: Chemical Building Blocks. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-13-054091-1. OCLC 47925884.

There are 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (that's 2 sextillion) atoms of oxygen in one drop of water—and twice as many atoms of hydrogen.

- ^ "The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 1: Atoms in Motion". Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Radioactivity". Splung.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. pp. 3–56. ISBN 978-0-12-436603-9. OCLC 16212955.

- ^ Firestone, Richard B. (22 May 2000). "Radioactive Decay Modes". Berkeley Laboratory. Archived from the original on 29 September 2006.

- ^ Hornak, J.P. (2006). "Chapter 3: Spin Physics". The Basics of NMR. Rochester Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007.

- ^ a b Schroeder, Paul A. (25 February 2000). "Magnetic Properties". University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007.

- ^ Goebel, Greg (1 September 2007). "[4.3] Magnetic Properties of the Atom". Elementary Quantum Physics. In The Public Domain website. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ Yarris, Lynn (Spring 1997). "Talking Pictures". Berkeley Lab Research Review. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008.

- ^ Liang, Z.-P.; Haacke, E.M. (1999). Webster, J.G. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering: Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 412–426. ISBN 978-0-471-13946-1.

- ^ Zeghbroeck, Bart J. Van (1998). "Energy levels". Shippensburg University. Archived from the original on 15 January 2005.

- ^ Fowles, Grant R. (1989). Introduction to Modern Optics. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 227–233. ISBN 978-0-486-65957-2. OCLC 18834711.

- ^ Martin, W.C.; Wiese, W.L. (May 2007). "Atomic Spectroscopy: A Compendium of Basic Ideas, Notation, Data, and Formulas". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- ^ "Atomic Emission Spectra – Origin of Spectral Lines". Avogadro Web Site. Archived from the original on 28 February 2006. Retrieved 10 August 2006.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Richard (16 February 2007). "Fine structure". University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ Weiss, Michael (2001). "The Zeeman Effect". University of California-Riverside. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008.

- ^ Beyer, H.F.; Shevelko, V.P. (2003). Introduction to the Physics of Highly Charged Ions. CRC Press. pp. 232–236. ISBN 978-0-7503-0481-8. OCLC 47150433.

- ^ Watkins, Thayer. "Coherence in Stimulated Emission". San José State University. Archived from the original on 12 January 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "valence". doi:10.1351/goldbook.V06588

- ^ Reusch, William (16 July 2007). "Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 29 October 2007.

- ^ "Covalent bonding – Single bonds". chemguide. 2000. Archived from the original on 1 November 2008.

- ^ Husted, Robert; et al. (11 December 2003). "Periodic Table of the Elements". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ Baum, Rudy (2003). "It's Elemental: The Periodic Table". Chemical & Engineering News. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011.

- ^ Goodstein, David L. (2002). States of Matter. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 436–438. ISBN 978-0-13-843557-8.

- ^ Brazhkin, Vadim V. (2006). "Metastable phases, phase transformations, and phase diagrams in physics and chemistry". Physics-Uspekhi. 49 (7): 719–724. Bibcode:2006PhyU...49..719B. doi:10.1070/PU2006v049n07ABEH006013. S2CID 93168446.

- ^ Myers, Richard (2003). The Basics of Chemistry. Greenwood Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-313-31664-7. OCLC 50164580.

- ^ Staff (9 October 2001). "Bose–Einstein Condensate: A New Form of Matter". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008.

- ^ Colton, Imogen; Fyffe, Jeanette (3 February 1999). "Super Atoms from Bose–Einstein Condensation". The University of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007.

- ^ Jacox, Marilyn; Gadzuk, J. William (November 1997). "Scanning Tunneling Microscope". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2008. In particular, see the Nobel lecture by G. Binnig and H. Rohrer.

- ^ Jakubowski, N.; Moens, Luc; Vanhaecke, Frank (1998). "Sector field mass spectrometers in ICP-MS". Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy. 53 (13): 1739–1763. Bibcode:1998AcSpB..53.1739J. doi:10.1016/S0584-8547(98)00222-5.

- ^ Müller, Erwin W.; Panitz, John A.; McLane, S. Brooks (1968). "The Atom-Probe Field Ion Microscope". Review of Scientific Instruments. 39 (1): 83–86. Bibcode:1968RScI...39...83M. doi:10.1063/1.1683116.

- ^ Lochner, Jim; Gibb, Meredith; Newman, Phil (30 April 2007). "What Do Spectra Tell Us?". NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 16 January 2008.

- ^ Winter, Mark (2007). "Helium". WebElements. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007.

- ^ Hinshaw, Gary (10 February 2006). "What is the Universe Made Of?". NASA/WMAP. Archived from the original on 31 December 2007.

- ^ Choppin, Gregory R.; Liljenzin, Jan-Olov; Rydberg, Jan (2001). Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry. Elsevier. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-7506-7463-8. OCLC 162592180.

- ^ Davidsen, Arthur F. (1993). "Far-Ultraviolet Astronomy on the Astro-1 Space Shuttle Mission". Science. 259 (5093): 327–334. Bibcode:1993Sci...259..327D. doi:10.1126/science.259.5093.327. PMID 17832344. S2CID 28201406.

- ^ Lequeux, James (2005). The Interstellar Medium. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-540-21326-0. OCLC 133157789.

- ^ Smith, Nigel (6 January 2000). "The search for dark matter". Physics World. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008.

- ^ Croswell, Ken (1991). "Boron, bumps and the Big Bang: Was matter spread evenly when the Universe began? Perhaps not; the clues lie in the creation of the lighter elements such as boron and beryllium". New Scientist (1794): 42. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008.

- ^ Copi, Craig J.; Schramm, DN; Turner, MS (1995). "Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis and the Baryon Density of the Universe". Science (Submitted manuscript). 267 (5195): 192–199. arXiv:astro-ph/9407006. Bibcode:1995Sci...267..192C. doi:10.1126/science.7809624. PMID 7809624. S2CID 15613185. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019.

- ^ Hinshaw, Gary (15 December 2005). "Tests of the Big Bang: The Light Elements". NASA/WMAP. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008.

- ^ Abbott, Brian (30 May 2007). "Microwave (WMAP) All-Sky Survey". Hayden Planetarium. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013.

- ^ Hoyle, F. (1946). "The synthesis of the elements from hydrogen". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 106 (5): 343–383. Bibcode:1946MNRAS.106..343H. doi:10.1093/mnras/106.5.343.

- ^ Knauth, D.C.; Knauth, D.C.; Lambert, David L.; Crane, P. (2000). "Newly synthesized lithium in the interstellar medium". Nature. 405 (6787): 656–658. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..656K. doi:10.1038/35015028. PMID 10864316. S2CID 4397202.

- ^ Mashnik, Stepan G. (2000). "On Solar System and Cosmic Rays Nucleosynthesis and Spallation Processes". arXiv:astro-ph/0008382.

- ^ Kansas Geological Survey (4 May 2005). "Age of the Earth". University of Kansas. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008.

- ^ a b Manuel (2001). Origin of Elements in the Solar System, pp. 40–430, 511–519

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. S2CID 130092094. Archived from the original on 11 November 2007.

- ^ Anderson, Don L.; Foulger, G.R.; Meibom, Anders (2 September 2006). "Helium: Fundamental models". MantlePlumes.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- ^ Pennicott, Katie (10 May 2001). "Carbon clock could show the wrong time". PhysicsWeb. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007.

- ^ Yarris, Lynn (27 July 2001). "New Superheavy Elements 118 and 116 Discovered at Berkeley Lab". Berkeley Lab. Archived from the original on 9 January 2008.

- ^ Diamond, H; et al. (1960). "Heavy Isotope Abundances in Mike Thermonuclear Device". Physical Review. 119 (6): 2000–2004. Bibcode:1960PhRv..119.2000D. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.119.2000.

- ^ Poston, John W. Sr. (23 March 1998). "Do transuranic elements such as plutonium ever occur naturally?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015.

- ^ Keller, C. (1973). "Natural occurrence of lanthanides, actinides, and superheavy elements". Chemiker Zeitung. 97 (10): 522–530. OSTI 4353086.

- ^ Zaider, Marco; Rossi, Harald H. (2001). Radiation Science for Physicians and Public Health Workers. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-306-46403-4. OCLC 44110319.

- ^ "Oklo Fossil Reactors". Curtin University of Technology. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Weisenberger, Drew. "How many atoms are there in the world?". Jefferson Lab. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael. "Fundamentals of Physical Geography". University of British Columbia Okanagan. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Anderson, Don L. (2002). "The inner inner core of Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (22): 13966–13968. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913966A. doi:10.1073/pnas.232565899. PMC 137819. PMID 12391308.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1960). The Nature of the Chemical Bond. Cornell University Press. pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-8014-0333-0. OCLC 17518275.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Anonymous (2 October 2001). "Second postcard from the island of stability". CERN Courier. Archived from the original on 3 February 2008.

- ^ Karpov, A. V.; Zagrebaev, V. I.; Palenzuela, Y. M.; et al. (2012). "Decay properties and stability of the heaviest elements" (PDF). International Journal of Modern Physics E. 21 (2): 1250013-1 – 1250013-20. Bibcode:2012IJMPE..2150013K. doi:10.1142/S0218301312500139. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Superheavy Element 114 Confirmed: A Stepping Stone to the Island of Stability". Berkeley Lab. 2009. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Möller, P. (2016). "The limits of the nuclear chart set by fission and alpha decay" (PDF). EPJ Web of Conferences. 131: 03002-1 – 03002-8. Bibcode:2016EPJWC.13103002M. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201613103002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Koppes, Steve (1 March 1999). "Fermilab Physicists Find New Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008.

- ^ Cromie, William J. (16 August 2001). "A lifetime of trillionths of a second: Scientists explore antimatter". Harvard University Gazette. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006.

- ^ Hijmans, Tom W. (2002). "Particle physics: Cold antihydrogen". Nature. 419 (6906): 439–440. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..439H. doi:10.1038/419439a. PMID 12368837.