Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aztecs

View on Wikipedia

| Aztec civilization |

|---|

|

| Aztec society |

| Aztec history |

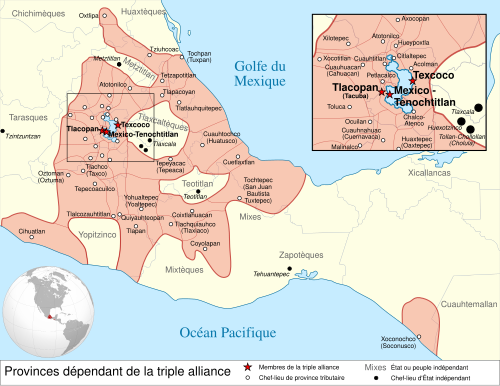

The Aztecs[a] (/ˈæztɛks/ AZ-teks) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Mexica or Tenochca, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs[1] is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era,[2] as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821).[3]

Most ethnic groups of central Mexico in the post-classic period shared essential cultural traits of Mesoamerica.[4] The culture of central Mexico includes maize cultivation, the social division between nobility (pipiltin) and commoners (macehualtin), a pantheon, and the calendric system. Particular to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan was the patron god Huitzilopochtli, twin pyramids, and the ceramic styles known as Aztec I to IV.[5] The Mexica were late-comers to the Valley of Mexico, and founded the city-state of Tenochtitlan on unpromising islets in Lake Texcoco, later becoming the dominant power of the Aztec Triple Alliance or Aztec Empire which conquered other city-states throughout Mesoamerica. It originated in 1427 as an alliance between the city-states Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan to defeat the Tepanec state of Azcapotzalco, which had previously dominated the Basin of Mexico. Soon Texcoco and Tlacopan were relegated to junior partnership in the alliance, with Tenochtitlan the dominant power. The empire extended its reach by a combination of trade and military conquest. It was never a true territorial empire controlling territory by large military garrisons in conquered provinces but rather dominated its client city-states primarily by installing friendly rulers in conquered territories, constructing marriage alliances between the ruling dynasties, and extending an imperial ideology to its client city-states.[6] Client city-states paid taxes, not tribute[7] to the Aztec emperor, the Huey Tlatoani, in an economic strategy limiting communication and trade between outlying polities, making them dependent on the imperial center for the acquisition of luxury goods.[8] The political clout of the empire reached far south into Mesoamerica conquering polities as far south as Chiapas and Guatemala and spanning Mesoamerica from the Pacific to the Atlantic oceans.[9]

The empire reached its maximum extent in 1519, just before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés. Cortés allied with city-states opposed to the Mexica, particularly the Nahuatl-speaking Tlaxcalteca as well as other central Mexican polities, including Texcoco, its former ally in the Triple Alliance. After the fall of Tenochtitlan on 13 August 1521 and the capture of the emperor Cuauhtémoc, the Spanish founded Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan and proceeded with the process of conquest and incorporation of Mesoamerican peoples into the Spanish Empire.[10] With the destruction of the superstructure of the Aztec Empire in 1521, the Spanish used the city-states on which the Aztec Empire had been built to rule the indigenous populations via their local nobles. Nobles acted as intermediaries to convey taxes and mobilize labor for their new overlords, facilitating the establishment of Spanish colonial rule.[11]

Aztec culture and history are primarily known through archaeological evidence found in excavations such as that of the renowned Templo Mayor in Mexico City; from Indigenous writings; from eyewitness accounts by Spanish conquistadors such as Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo; and especially from 16th- and 17th-century descriptions of Aztec culture and history written by Spanish clergymen and literate Aztecs in the Spanish or Nahuatl language, such as the famous illustrated, bilingual (Spanish and Nahuatl), twelve-volume Florentine Codex created by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, in collaboration with Indigenous Aztec informants. Important for knowledge of post-conquest Nahuas was the training of indigenous scribes to write alphabetic texts in Nahuatl, mainly for local purposes under Spanish colonial rule. At its height, Aztec culture had rich and complex philosophical, mythological, and religious traditions, as well as remarkable architectural and artistic accomplishments.

Definitions

[edit]

The Nahuatl words aztēcatl (Nahuatl pronunciation: [asˈteːkat͡ɬ], singular)[12] and aztēcah (Nahuatl pronunciation: [asˈteːkaʔ], plural)[12] mean "people from Aztlán",[13] a mythical place of origin for several ethnic groups in central Mexico. The term was not used as an endonym by the Aztecs themselves, but it is found in the different migration accounts of the Mexica, where it describes the different tribes who left Aztlan together. In one account of the journey from Aztlan, Huitzilopochtli, the tutelary deity of the Mexica tribe, tells his followers on the journey that "now, no longer is your name Azteca, you are now Mexitin [Mexica]".[14]

In today's usage, the term "Aztec" often refers exclusively to the Mexica people of Tenochtitlan (now the location of Mexico City), situated on an island in Lake Texcoco, who referred to themselves as Mēxihcah (Nahuatl pronunciation: [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ], a tribal designation that included the Tlatelolco), Tenochcah (Nahuatl pronunciation: [teˈnot͡ʃkaʔ], referring only to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, excluding Tlatelolco) or Cōlhuah (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈkoːlwaʔ], referring to their royal genealogy tying them to Culhuacan).[15][16][nb 1][nb 2]

Sometimes the term also includes the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan's two principal allied city-states, the Acolhuas of Texcoco and the Tepanecs of Tlacopan, who together with the Mexica formed the Triple Alliance, a state exerting control over the Valley of Mexico in a collective polity often known as the "Aztec Empire". The usage of the term "Aztec" in describing the empire and its people has been criticized by Robert H. Barlow, who preferred the term "Culhua-Mexica" in reference to the empire's people,[15][17] and by Pedro Carrasco, who prefers the term "Tenochca Empire" in reference to their state.[18] Carrasco writes about the term "Aztec" that "it is of no use for understanding the ethnic complexity of ancient Mexico and for identifying the dominant element in the political entity we are studying".[18]

In other contexts, Aztec may refer to all the various city-states and their peoples, who shared large parts of their ethnic history and cultural traits with the Mexica, Acolhua, and Tepanecs, and who often also used the Nahuatl language as a lingua franca. An example is Jerome A. Offner's Law and Politics in Aztec Texcoco.[19] In this meaning, it is possible to talk about an "Aztec civilization" including all the particular cultural patterns common for most of the peoples inhabiting central Mexico in the late postclassic period.[20] Such usage may also extend the term "Aztec" to all the groups in Central Mexico that were incorporated culturally or politically into the sphere of dominance of the Aztec empire.[21][nb 3]

When used to describe ethnic groups, the term "Aztec" refers to several Nahuatl-speaking peoples of central Mexico in the postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology, especially the Mexica, the ethnic group that had a leading role in establishing the hegemonic empire based at Tenochtitlan. The term extends to further ethnic groups associated with the Aztec empire, such as the Acolhua, the Tepanec, and others that were incorporated into the empire. Charles Gibson enumerates many groups in central Mexico that he includes in his study The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule (1964). These include the Culhuaque, Cuitlahuaque, Mixquica, Xochimilca, Chalca, Tepaneca, Acolhuaque, and Mexica.[22]

In older usage, the term was commonly used about modern Nahuatl-speaking ethnic groups, as Nahuatl was previously referred to as the "Aztec language". In recent usage, these ethnic groups are referred to as the Nahua peoples.[23][24] Linguistically, the term "Aztecan" is still used about the branch of the Uto-Aztecan languages (also sometimes called the Uto-Nahuan languages) that includes the Nahuatl language and its closest relatives Pochutec and Pipil.[25]

To the Aztecs themselves the word "Aztec" was not an endonym for any particular ethnic group. Rather, it was an umbrella term used to refer to several ethnic groups, not all of them Nahuatl-speaking, that claimed heritage from the mythic place of origin, Aztlan. Alexander von Humboldt originated the modern usage of "Aztec" in 1810, as a collective term applied to all the people linked by trade, custom, religion, and language to the Mexica state and the Triple Alliance. In 1843, with the publication of the work of William H. Prescott on the history of the conquest of Mexico, the term was adopted by most of the world, including 19th-century Mexican scholars who saw it as a way to distinguish present-day Mexicans from pre-conquest Mexicans. This usage has been the subject of debate in more recent years, but the term "Aztec" is still more common.[16]

History

[edit]Sources of knowledge

[edit]

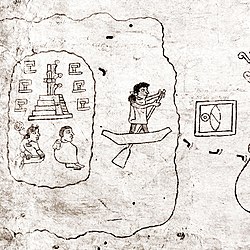

Knowledge of Aztec society rests on several different sources: The many archeological remains of everything from temple pyramids to thatched huts can be used to understand many of the aspects of what the Aztec world was like. However, archeologists often must rely on knowledge from other sources to interpret the historical context of artifacts. There are many written texts by the indigenous people and Spaniards of the early colonial period that contain invaluable information about pre-colonial Aztec history. These texts provide insight into the political histories of various Aztec city-states, and their ruling lineages. Such histories were produced as well in pictorial codices. Some of these manuscripts were entirely pictorial, often with glyphs. In the postconquest era, many other texts were written in Latin script by either literate Aztecs or by Spanish friars who interviewed the native people about their customs and stories. An important pictorial and alphabetic text produced in the early sixteenth century was Codex Mendoza, named after the first viceroy of Mexico and perhaps commissioned by him, to inform the Spanish crown about the political and economic structure of the Aztec empire. It has information naming the polities that the Triple Alliance conquered, the types of taxes rendered to the Aztec Empire, and the class/gender structure of their society.[26] Many written annals exist, written by local Nahua historians recording the histories of their polity. These annals used pictorial histories and were subsequently transformed into alphabetic annals in Latin script.[27] Well-known native chroniclers and annalists are Chimalpahin of Amecameca-Chalco; Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc of Tenochtitlan; Alva Ixtlilxochitl of Texcoco, Juan Bautista Pomar of Texcoco, and Diego Muñoz Camargo of Tlaxcala. There are also many accounts by Spanish conquerors who participated in the Spanish invasion, such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo who wrote a full history of the conquest.

Spanish friars also produced documentation in chronicles and other types of accounts. Of key importance is Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, one of the first twelve Franciscans arriving in Mexico in 1524. Another Franciscan of great importance was Fray Juan de Torquemada, author of Monarquia Indiana. Dominican Diego Durán also wrote extensively about pre-Hispanic religion as well as the history of the Mexica.[28] An invaluable source of information about many aspects of Aztec religious thought, political and social structure, as well as the history of the Spanish conquest from the Mexica viewpoint is the Florentine Codex. Produced between 1545 and 1576 in the form of an ethnographic encyclopedia written bilingually in Spanish and Nahuatl, by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and indigenous informants and scribes, it contains knowledge about many aspects of precolonial society from religion, calendrics, botany, zoology, trades and crafts and history.[29][30] Another source of knowledge is the cultures and customs of the contemporary Nahuatl speakers who can often provide insights into what prehispanic ways of life may have been like. Scholarly study of Aztec civilization is most often based on scientific and multidisciplinary methodologies, combining archeological knowledge with ethnohistorical and ethnographic information.[31]

Central Mexico in the classic and postclassic

[edit]

It is a matter of debate whether the enormous city of Teotihuacan was inhabited by speakers of Nahuatl, or whether Nahuas had not yet arrived in central Mexico in the classic period. It is generally agreed that the Nahua peoples were not indigenous to the highlands of central Mexico, but that they gradually migrated into the region from somewhere in northwestern Mexico. At the fall of Teotihuacan in the 6th century CE, some city-states rose to power in central Mexico, some of them, including Cholula and Xochicalco, probably inhabited by Nahuatl speakers. One study has suggested that Nahuas originally inhabited the Bajío area around Guanajuato which reached a population peak in the 6th century, after which the population quickly diminished during a subsequent dry period. This depopulation of the Bajío coincided with an incursion of new populations into the Valley of Mexico, which suggests that this marks the influx of Nahuatl speakers into the region.[32] These people populated central Mexico, dislocating speakers of Oto-Manguean languages as they spread their political influence south. As the former nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples mixed with the complex civilizations of Mesoamerica, adopting religious and cultural practices, the foundation for later Aztec culture was laid. After 900 CE, during the postclassic period, many sites almost certainly inhabited by Nahuatl speakers became powerful. Among them are the site of Tula, Hidalgo, and also city-states such as Tenayuca, and Colhuacan in the valley of Mexico and Cuauhnahuac in Morelos.[33]

Mexica migration and foundation of Tenochtitlan

[edit]In the ethnohistorical sources from the colonial period, the Mexica themselves describe their arrival in the Valley of Mexico. The ethnonym Aztec (Nahuatl Aztecah) means "people from Aztlan", Aztlan being a mythical place of origin toward the north. Hence the term applied to all those peoples who claimed to carry the heritage from this mythical place. The migration stories of the Mexica tribe tell how they traveled with other tribes, including the Tlaxcalteca, Tepaneca, and Acolhua, but that eventually their tribal deity Huitzilopochtli told them to split from the other Aztec tribes and take on the name "Mexica".[34] At the time of their arrival, there were many Aztec city-states in the region. The most powerful were Colhuacan to the south and Azcapotzalco to the west. The Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco soon expelled the Mexica from Chapultepec and executed the first Aztec royal family except Queen Chimalxochitl II. In 1299, Colhuacan ruler Cocoxtli permitted them to settle in the empty barrens of Tizapan, where they were eventually assimilated into Culhuacan culture.[35] The noble lineage of Colhuacan traced its roots back to the legendary city-state of Tula, and by marrying into Colhua families, the Mexica now appropriated this heritage. After living in Colhuacan, the Mexica were again expelled and were forced to move.[36]

According to Aztec legend, in 1323, the Mexica were shown a vision of an eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, eating a snake. The vision indicated where they were to build their settlement. The Mexica founded Tenochtitlan on a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco, the inland lake of the Basin of Mexico. The year of foundation is usually given as 1325. In 1376 the Mexica royal dynasty was founded when Acamapichtli was elected as the first Huey Tlatoani of Tenochtitlan.[37]

Early Mexica rulers

[edit] |

| Rulers (tlahtoqueh) of Tenochtitlan |

|---|

| Rulers subject to Azcapotzalco |

| Acamapichtli (1375–1395) |

| Huitzilihhuitl (1396–1417) |

| Chimalpopoca (1417–1427) |

| Independent rulers |

| Itzcoatl (1427–1440) |

| Motecuzoma I Ilhuicamina (1440–1469) |

| Axayacatl (1469–1481) |

| Tizoc (1481–1486) |

| Ahuitzotl (1486–1502) |

| Motecuzoma II Xocoyotzin (1502–1520) |

| Cuitlahuac (1520) |

| Cuauhtemoc (1520–1521) |

| Colonial indigenous governors |

| Juan Velázquez Tlacotzin (1525) |

| Andrés de Tapia Motelchiuh (1525–1530) |

| Pablo Xochiquentzin (1532–1536) |

| Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin (1539–1541) |

| Diego de San Francisco Tehuetzquititzin (1541–1554) |

| Esteban de Guzmán (1554–1557) |

| Cristóbal de Guzmán Cecetzin (1557–1562) |

| Luis de Santa María Nanacacipactzin (1563–1565) |

In the first 50 years after the founding of the Mexica dynasty, the Mexica were a tributary of Azcapotzalco, which had become a major regional power under the ruler Tezozomoc. The Mexica supplied the Tepaneca with warriors for their successful conquest campaigns in the region and received part of the tribute from the conquered city-states. In this way, the political standing and economy of Tenochtitlan gradually grew.[38]

In 1396, at Acamapichtli's death, his son Huitzilihhuitl (lit. "Hummingbird feather") became ruler; married to Tezozomoc's daughter, the relationship with Azcapotzalco remained close. Chimalpopoca (lit. "She smokes like a shield"), son of Huitzilihhuitl, became ruler of Tenochtitlan in 1417. In 1418, Azcapotzalco initiated a war against the Acolhua of Texcoco and killed their ruler Ixtlilxochitl. Even though Ixtlilxochitl was married to Chimalpopoca's daughter, the Mexica ruler continued to support Tezozomoc. Tezozomoc died in 1426, and his sons began a struggle for the rulership of Azcapotzalco. During this power struggle, Chimalpopoca died, probably killed by Tezozomoc's son Maxtla who saw him as a competitor.[39] Itzcoatl, brother of Huitzilihhuitl and uncle of Chimalpopoca, was elected the next Mexica tlatoani. The Mexica were now in open war with Azcapotzalco and Itzcoatl petitioned for an alliance with Nezahualcoyotl, son of the slain Texcocan ruler Ixtlilxochitl against Maxtla. Itzcoatl also allied with Maxtla's brother Totoquihuaztli ruler of the Tepanec city of Tlacopan. The Triple Alliance of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan besieged Azcapotzalco, and in 1428 they destroyed the city and sacrificed Maxtla. Through this victory, Tenochtitlan became the dominant city-state in the Valley of Mexico, and the alliance between the three city-states provided the basis on which the Aztec Empire was built.[40]

Itzcoatl proceeded by securing a power basis for Tenochtitlan, by conquering the city-states on the southern lake – including Culhuacan, Xochimilco, Cuitlahuac, and Mizquic. These states had an economy based on highly productive chinampa agriculture, cultivating human-made extensions of rich soil in the shallow lake Xochimilco. Itzcoatl then undertook further conquests in the valley of Morelos, subjecting the city-state of Cuauhnahuac (today Cuernavaca).[41]

Early rulers of the Aztec Empire

[edit]Motecuzoma I Ilhuicamina

[edit]

In 1440, Moteuczomatzin Ilhuicamina[nb 4] (lit. "he frowns like a lord, he shoots the sky"[nb 5]) was elected tlatoani; he was the son of Huitzilihhuitl, brother of Chimalpopoca and had served as the war leader of his uncle Itzcoatl in the war against the Tepanecs. The accession of a new ruler in the dominant city-state was often an occasion for subjected cities to rebel by refusing to pay taxes. This meant that new rulers began their rule with a coronation campaign, often against rebellious provinces, but also sometimes demonstrating their military might by making new conquests. Motecuzoma tested the attitudes of the cities around the valley by requesting laborers for the enlargement of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. Only the city of Chalco refused to provide laborers, and hostilities between Chalco and Tenochtitlan would persist until the 1450s.[42][43] Motecuzoma then reconquered the cities in the valley of Morelos and Guerrero, and then later undertook new conquests in the Huaxtec region of northern Veracruz, and the Mixtec region of Coixtlahuaca and large parts of Oaxaca, and later again in central and southern Veracruz with conquests at Cosamalopan, Ahuilizapan, and Cuetlaxtlan.[44] During this period the city-states of Tlaxcalan, Cholula and Huexotzinco emerged as major competitors to the imperial expansion, and they supplied warriors to several of the cities conquered. Motecuzoma therefore initiated a state of low-intensity warfare against these three cities, staging minor skirmishes called "Flower Wars" (Nahuatl xochiyaoyotl) against them, perhaps as a strategy of exhaustion.[45][46] In the Valley of Oaxaca, which was invaded Moctezuma's forces in the 1450s, the Aztec Empire would oppress the Mixtec and Zapotec peoples, who they would also require to pay tributes.[47]

Motecuzoma I also consolidated the political structure of the Triple Alliance and the internal political organization of Tenochtitlan. His brother Tlacaelel served as his main advisor (Nahuatl languages: Cihuacoatl) and he is considered responsible for the major political reforms in this period, consolidating the power of the noble class (Nahuatl languages: pipiltin) and instituting a set of legal codes, and the practice of reinstating conquered rulers in their cities bound by fealty to the Mexica tlatoani.[48][49][45]

Axayacatl and Tizoc

[edit]In 1469, the next ruler was Axayacatl (lit. "Water mask"), son of Itzcoatl's son Tezozomoc and Motecuzoma I's daughter Atotoztli II.[nb 6] He undertook a successful coronation campaign far south of Tenochtitlan against the Zapotecs in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Axayacatl also conquered the independent Mexica city of Tlatelolco, located on the northern part of the island where Tenochtitlan was also located. The Tlatelolco ruler Moquihuix was married to Axayacatl's sister, and his alleged mistreatment of her was used as an excuse to incorporate Tlatelolco and its important market directly under the control of the tlatoani of Tenochtitlan.[50]

Axayacatl then conquered areas in Central Guerrero, the Puebla Valley, on the gulf coast and against the Otomi and Matlatzinca in the Toluca Valley. The Toluca Valley was a buffer zone against the powerful Tarascan state in Michoacan, against which Axayacatl turned next. In the major campaign against the Tarascans (Nahuatl languages: Michhuahqueh) in 1478–1479 the Aztec forces were repelled by a well-organized defense. Axayacatl was soundly defeated in a battle at Tlaximaloyan (today Tajimaroa), losing most of his 32,000 men and only barely escaping back to Tenochtitlan with the remnants of his army.[51]

In 1481 at Axayacatls death, his older brother Tizoc was elected ruler. Tizoc's coronation campaign against the Otomi of Metztitlan failed as he lost the major battle and only managed to secure 40 prisoners to be sacrificed for his coronation ceremony. Having shown weakness, many cities rebelled and consequently, most of Tizoc's short reign was spent attempting to quell rebellions and maintain control of areas conquered by his predecessors. Tizoc died suddenly in 1485, and it has been suggested that he was poisoned by his brother and war leader Ahuitzotl who became the next tlatoani. Tizoc is mostly known as the namesake of the Stone of Tizoc a monumental sculpture (Nahuatl temalacatl), decorated with a representation of Tizoc's conquests.[52]

Ahuitzotl

[edit]

The next ruler was Ahuitzotl (lit. "Water monster"), brother of Axayacatl and Tizoc and war leader under Tizoc. His successful coronation campaign suppressed rebellions in the Toluca Valley and conquered Jilotepec and several communities in the northern Valley of Mexico. A second 1521 campaign to the gulf coast was also highly successful. He began an enlargement of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, inaugurating the new temple in 1487. For the inauguration ceremony, the Mexica invited the rulers of all their subject cities, who participated as spectators in the ceremony in which an unprecedented number of war captives were sacrificed – some sources giving a figure of 80,400 prisoners sacrificed over four days. Probably the actual figure of sacrifices was much smaller, but still numbering several thousand. There have never been found enough skulls in the capital to satisfy even the most conservative figures.[53] Ahuitzotl also constructed monumental architecture in sites such as Calixtlahuaca, Malinalco, and Tepoztlan. After a rebellion in the towns of Alahuiztlan and Oztoticpac in Northern Guerrero, he ordered the entire population executed and repopulated with people from the valley of Mexico. He also constructed a fortified garrison at Oztuma defending the border against the Tarascan state.[54]

Final Aztec rulers and the Spanish conquest

[edit]

Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin is known to world history as the Aztec ruler when the Spanish invaders and their indigenous allies began their conquest of the empire in a two-year-long campaign (1519–1521). His early rule did not hint at his future fame. He succeeded in the rulership after the death of Ahuitzotl. Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (lit. "He frowns like a lord, the youngest child who is dead as he had lived in life but not death"), was a son of Axayacatl, and a war leader. He began his rule in standard fashion, conducting a coronation campaign to demonstrate his skills as a leader. He attacked the fortified city of Nopallan in Oaxaca and subjected the adjacent region to the empire. An effective warrior, Moctezuma maintained the pace of conquest set by his predecessor and subjected large areas in Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, and even far south along the Pacific and Gulf coasts, conquering the province of Xoconochco in Chiapas. he also intensified the flower wars waged against Tlaxcala and Huexotzinco and secured an alliance with Cholula. He also consolidated the class structure of Aztec society, by making it harder for commoners (Nahuatl languages: macehualtin) to accede to the privileged class of the pipiltin through merit in combat. He also instituted a strict sumptuary code limiting the types of luxury goods that could be consumed by commoners.[55]

In 1517, Moctezuma received the first news of ships with strange warriors having landed on the Gulf Coast near Cempoallan and he dispatched messengers to greet them and find out what was happening, and he ordered his subjects in the area to keep him informed of any new arrivals. In 1519, he was informed of the arrival of the Spanish fleet of Hernán Cortés, who soon marched toward Tlaxcala where he allied with the traditional enemies of the Aztecs. On 8 November 1519, Moctezuma II received Cortés and his troops and Tlaxcalan allies on the causeway south of Tenochtitlan, and he invited the Spaniards to stay as his guests in Tenochtitlan. When Aztec troops destroyed a Spanish camp on the Gulf Coast, Cortés ordered Moctezuma to execute the commanders responsible for the attack, and Moctezuma complied. At this point, the power balance had shifted toward the Spaniards who now held Moctezuma as a prisoner in his palace. As this shift in power became clear to Moctezuma's subjects, the Spaniards became increasingly unwelcome in the capital city, and, in June 1520, hostilities broke out, culminating in the massacre in the Great Temple, and a major uprising of the Mexica against the Spanish. During the fighting, Moctezuma was killed, either by the Spaniards who killed him as they fled the city, or by the Mexica themselves who considered him a traitor.[56]

Cuitláhuac, a kinsman and adviser to Moctezuma, succeeded him as tlatoani, mounting the defense of Tenochtitlan against the Spanish invaders and their indigenous allies. He ruled for only 80 days, perhaps dying in a smallpox epidemic, although early sources do not give the cause. He was succeeded by Cuauhtémoc, the last independent Mexica tlatoani, who continued the fierce defense of Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs were weakened by disease, and the Spanish enlisted tens of thousands of Indian allies, especially Tlaxcalans, for the assault on Tenochtitlan. After the siege and destruction of the Aztec capital, Cuauhtémoc was captured on 13 August 1521, marking the beginning of Spanish hegemony in central Mexico. Spaniards held Cuauhtémoc captive until he was tortured and executed on the orders of Cortés, supposedly for treason, during an ill-fated expedition to Honduras in 1525. His death marked the end of a tumultuous era in Aztec political history.

After the fall of the Aztec Empire, entire Nahua communities were subject to forced labor under the encomienda system, the Aztec education system was abolished and replaced by a very limited church education, and Aztec religious practices were forcibly replaced with Catholicism.

The Cuauhtlatoque and Aztec polity post-conquest (1521–1565)

[edit]Cuauhtémoc and the deterritorialization of the tlatoque

[edit]

Following the Spanish and their indigenous allies' victory over the Triple Alliance, its tlatloque[nb 7] – Cuauhtémoc, captured on 13 August 1521 – was not immediately deposed of his titular throne while in captivity.[57][58] Rather, the Spanish maintained his nominal, but not actual authority, while they established a foothold in the Valley of Mexico, and understanding thereof. This dynamic also was to avoid ceding control over the Valley to their allies, who neighbored and detested the former Triple Alliance for its historic bellicosity towards them and their peoples.[59] According to Spanish legend only, he requested, upon his and his nobles' surrender, for Hernán Cortés to execute him by knife, "strik[ing him] dead immediately",[60] which Cortés supposedly refused, declaring that "A Spaniard knows how to respect valor, even in an enemy" and praising Cuauhtémoc for having "defended [his] capital like a brave warrior".[61]

The account continues that Cortés accepted Cuauhtémoc's request to leave the Mexica unharmed. Cortés later recanted his obligations upon seeing that the war bounty collected from the conquest did not meet his expectations, and proceeded to torture Cuauhtémoc by forcing him to walk over hot coals, out of the belief that he had attempted to hide more valuables. These valuables would not be recovered to the extent desired by Cortés. Cuauhtémoc was forcefully converted to Catholicism, baptised under the new name Fernando Cuauhtémotzín, relieved of his sovereignty, keeping only the title of tlatoani, and kept under house arrest[62] until his execution[63] – an event for which there exist numerous contradicting contemporary perspectives, testimonies, and reasonings.[64] There are, however, no Mexica sources describing these events, possibly due to the mass-destruction of indigenous texts during conquest.[65] Cuauhtémoc was the last tlatoani with full sovereign authority, as well as the last tlatoque whose title came through to him through dynastic lineage until the throne's dynastic restoration in 1538.

Cuāuhtlahtoāni (1525–1536)

[edit]

In the period immediately succeeding Cuauhtémoc's deposition, successors were directly installed by the Spanish to facilitate easier control of their new colony. This practice was employed by the Spanish in numerous areas throughout the early stages of conquest. This was to navigate the inherent difficulty in administer a foreign government in an incompletely understood land, whose people at the time were still recovering from war and plagued by European-introduced disease. Additionally, a puppet government served as an attempt to create an image of legitimacy towards the indigenous Mesoamericans. These installed tlatoani were known as Cuāuhtlahtoāni, meaning "the one who speaks like eagle" in Náhuatl, and as appointments, did not undergo the traditional Mexica investiture ceremony pursued with normal tlatoani. This invalidated the Cuahtlatoani's authority and right to rule in the eyes of their "subjects".

The Cuauhtlatoani were not a novel concept, but had precedent, as the term was used pre-conquest to describe an interim, non-dynastic regent with tlatloque-like authority. Generally, cuauhtlatoani would be appointed by tlatoani to administer recently-conquered lands, such as the Atlepetl of Tlatelolco following the 1473 defeat of its last Tlatoani – Moquihuix – by the Triple Alliance. Tlatelolco was governed by cuauhtlatoque until the death of Itzquauhtzin in 1520.[66] The term cuauhtlatoani is also sometimes used in early 16th-century codices to describe the mythic first leaders of the Mexica during their migration from Aztlán.[67]

In the context of the Spanish conquest, the indigenous population's general view of the cuauhtlatoani as illegitimate was initially of benefit and preference to Hernán Cortés and the Spanish, who saw it as a way of ensuring their appointees would not be seen as a source of allegiance separate from the Spanish crown.[68] Despite their illegitimacy, Mexica codices composed after their reigns would describe cuauhtlatoani as if they were tlatoani, but differ considerably on perceptions of legitimacy, with some vocally ascribing illegitimacy to their reigns and others remaining silent on the matter entirely, implying continuity with their predecessors.[69]

There were three cuauhtlatoani of Tenochtitlan before the restoration of dynastically-derived rulership to the atlepetl in 1565. These were Tlacotzin (reigned less than a year sometime between 1525 and 1526), who died before even reaching Tenochtitlan,[70] Motelchiuhtzin (1525/1526–1530/1531), a Mexica commoner and officer for Hernán Cortéz, and Xochiquentzin (1532–1536), a Mexica commoner who had previously served as calpixqui, a minor administrative palatine officer.[71]

Restoration of dynastic rulership (1538–1565)

[edit]1538 saw the dynastic rulership restored to the throne of Tenochtitlan, still in a dynamic of vassalage to the authority expressed by the conquistadors in the name of the Spanish crown.[62] The reasoning behind this choice is not certain, but it was probably made by the Spanish viceroy of New Spain from 1535 to 1550, Antonio de Mendoza, in pursuit of a more authoritative appearance of legitimacy in regards to Spanish rule over the Mexica.[70] The restoration entailed a revalidation of the role of Mexica nobility in the selection of a tlatloque, where a candidate they elected would be forwarded to the Spanish authority for confirmation and installation.[57] This helped forward an air of authority and responsibility in the eye of the Mexica towards the Spanish and the new tlatoani.

This period saw four tlatoani with one cuauhtlatoque acting to serve in only a transitional role between tlatoani. These were: Huanitzin (1538–1541),[72] grandnephew to Moctezuma II – who was popular amongst the Nahua and was bilingual in Spanish and Náhuatl – followed by Tehuetzquititzin (1541–1554), who was de facto succeeded by the magistrate of Tenochtitlan, Omacatzin, a commoner from Xochimilco whose authority only served a temporary and transitional buffer between Tehuetzquititzin, and his de jure successor, Cecetzin (1557–1562). The reason for this interregnum and its significant length is, to date, unknown.[57] Cetcetzin was succeeded by Cipac (1563–1565), whose reign saw numerous conflicts between him and the Spanish authorities in regards to jurisprudence and taxation – the stress of which would lead to his early death, as well as the Spanish's decision to continue with direct administration over the remnants of the Triple Alliance through the creation of Spanish-appointed governorships. These governorships would, at least initially, be held by indigenous or mestizo administrators, none of which, however, were dynastically contiguous with the tlatloque.[73]

Social and political organization

[edit]Nobles and commoners

[edit]

The highest class was the pīpiltin[nb 8] or nobility. The pilli status was hereditary and ascribed certain privileges to its holders, such as the right to wear particularly fine garments and consume luxury goods, as well as to own land and direct corvee labor by commoners. The most powerful nobles were called lords (Nahuatl languages: teuctin) and they owned and controlled noble estates or houses, and could serve in the highest government positions or as military leaders. Nobles made up about five percent of the population.[74]

The second class was the mācehualtin, originally peasants, but later extended to the lower working classes in general. Eduardo Noguera estimates that in later stages only 20 percent of the population was dedicated to agriculture and food production.[75] The other 80 percent of society were warriors, artisans, and traders. Eventually, most of the mācehuallis were dedicated to arts and crafts. Their works were an important source of income for the city.[76] Macehualtin could become enslaved, (Nahuatl languages: tlacotin) for example if they had to sell themselves into the service of a noble due to debt or poverty, but enslavement was not an inherited status among the Aztecs. Some macehualtin were landless and worked directly for a lord (Nahuatl languages: mayehqueh), whereas the majority of commoners were organized into calpollis which gave them access to land and property.[77]

Commoners were able to obtain privileges similar to those of the nobles by demonstrating prowess in warfare. When a warrior took a captive he accrued the right to use certain emblems, weapons, or garments, and as he took more captives his rank and prestige increased.[78]

Family and gender

[edit]

The Aztec family pattern was bilateral, counting relatives on the father's and mother's side of the family equally, and inheritance was also passed both to sons and daughters. This meant that women could own property just as men and that women therefore had a good deal of economic freedom from their spouses. Nevertheless, Aztec society was highly gendered with separate gender roles for men and women. Men were expected to work outside of the house, as farmers, traders, craftsmen, and warriors, whereas women were expected to take responsibility for the domestic sphere. Women could however also work outside of the home as small-scale merchants, doctors, priests, and midwives. Warfare was highly valued and a source of high prestige, but women's work was metaphorically conceived of as equivalent to warfare, and as equally important in maintaining the equilibrium of the world and pleasing the gods. This situation has led some scholars to describe Aztec gender ideology as an ideology not of a gender hierarchy, but of gender complementarity, with gender roles being separate but equal.[79]

Among the nobles, marriage alliances were often used as a political strategy with lesser nobles marrying daughters from more prestigious lineages whose status was then inherited by their children. Nobles were also often polygamous, with lords having many wives. Polygamy was not very common among the commoners and some sources describe it as being prohibited.[80]

Altepetl and calpolli

[edit]

The main unit of Aztec political organization was the city-state, in Nahuatl called the altepetl, meaning "water-mountain". Each altepetl was led by a ruler, a tlatoani, with authority over a group of nobles and a population of commoners. The altepetl included a capital that served as a religious center, the hub of distribution and organization of a local population that often lived spread out in minor settlements surrounding the capital. Altepetl was also the main source of ethnic identity for the inhabitants, even though Altepetl was frequently composed of groups speaking different languages. Each altepetl would see itself as standing in political contrast to other altepetl polities, and war was waged between altepetl states. In this way, Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs of one Altepetl would be solidary with speakers of other languages belonging to the same altepetl, but enemies of Nahuatl speakers belonging to other competing altepetl states. In the basin of Mexico, altepetl was composed of subdivisions called calpolli, which served as the main organizational unit for commoners. In Tlaxcala and the Puebla valley, the altepetl was organized into teccalli units headed by a lord (Nahuatl languages: tecutli), who would hold sway over a territory and distribute rights to land among the commoners. A calpolli was at once a territorial unit where commoners organized labor and land use since the land was not private property, and also often a kinship unit as a network of families that were related through intermarriage. Calpolli leaders might be or become members of the nobility, in which case they could represent their Calpolli interests in the altepetl government.[81][82]

In the valley of Morelos, archeologist Michael E. Smith estimates that a typical altepetl had from 10,000 to 15,000 inhabitants, and covered an area between 70 and 100 square kilometers (27 and 39 sq mi). In the Morelos Valley, altepetl sizes were somewhat smaller. Smith argues that the altepetl was primarily a political unit, made up of the population with allegiance to a lord, rather than as a territorial unit. He makes this distinction because in some areas minor settlements with different altepetl allegiances were interspersed.[83]

Triple Alliance and Aztec Empire

[edit]

The Aztec Empire was ruled by indirect means. Like most European empires, it was ethnically very diverse, but unlike most European empires, it was more of a hegemonic confederacy than a single system of government. Ethnohistorian Ross Hassig has argued that the Aztec empire is best understood as an informal or hegemonic empire because it did not exert supreme authority over the conquered lands; it merely expected taxes to be paid and exerted force only to the degree it was necessary to ensure the payment of taxes.[84] It was also a discontinuous empire because not all dominated territories were connected; for example, the southern peripheral zones of Xoconochco were not in direct contact with the center. The hegemonic nature of the Aztec empire can be seen in the fact that generally local rulers were restored to their positions once their city-state was conquered, and the Aztecs did not generally interfere in local affairs as long as the tax payments were made and the local elites participated willingly. Such compliance was secured by establishing and maintaining a network of elites, related through intermarriage and different forms of exchange.[84]

Nevertheless, the expansion of the empire was accomplished through military control of frontier zones, in strategic provinces where a much more direct approach to conquest and control was taken. Such strategic provinces were often exempt from taxation. The Aztecs even invested in those areas, by maintaining a permanent military presence, installing puppet rulers, or even moving entire populations from the center to maintain a loyal base of support.[85] In this way, the Aztec system of government distinguished between different strategies of control in the outer regions of the empire, far from the core in the Valley of Mexico. Some provinces were treated as subject provinces, which provided the basis for economic stability for the empire, and strategic provinces, which were the basis for further expansion.[86]

Although the form of government is often referred to as an empire, most areas within the empire were organized as city-states, known as altepetl in Nahuatl. These were small polities ruled by a hereditary leader (tlatoani) from a legitimate noble dynasty. The Early Aztec period was a time of growth and competition among altepetl. Even after the confederation of the Triple Alliance was formed in 1427 and began its expansion through conquest, the altepetl remained the dominant form of organization at the local level. The efficient role of the altepetl as a regional political unit was largely responsible for the success of the empire's hegemonic form of control.[87]

Economy

[edit]Agriculture and subsistence

[edit]

Like all Mesoamerican peoples, Aztec society was organized around maize agriculture. The humid environment in the Valley of Mexico with its many lakes and swamps permitted intensive agriculture. The main crops in addition to maize were beans, squashes, chilies, and amaranth. Particularly important for agricultural production in the valley was the construction of chinampas on the lake, artificial islands that allowed the conversion of the shallow waters into highly fertile gardens that could be cultivated year-round. Chinampas are human-made extensions of agricultural land, created from alternating layers of mud from the bottom of the lake, and plant matter and other vegetation. These raised beds were separated by narrow canals, which allowed farmers to move between them by canoe. Chinampas were extremely fertile pieces of land, and yielded, on average, seven crops annually. Based on current chinampa yields, it has been estimated that one hectare (2.5 acres) of chinampa would feed 20 individuals and 9,000 hectares (22,000 acres) of chinampas could feed 180,000.[88]

The Aztecs further intensified agricultural production by constructing systems of artificial irrigation. While most of the farming occurred outside the densely populated areas, within the cities there was another method of (small-scale) farming. Each family had a garden plot where they grew maize, fruits, herbs, medicines, and other important plants. When the city of Tenochtitlan became a major urban center, water was supplied to the city through aqueducts from springs on the banks of the lake, and they organized a system that collected human waste for use as fertilizer. Through intensive agriculture, the Aztecs were able to sustain a large urbanized population. The lake was also a rich source of proteins in the form of aquatic animals such as fish, amphibians, shrimp, insects and insect eggs, and waterfowl. The presence of such varied sources of protein meant that there was little use for domestic animals for meat (only turkeys and dogs were kept), and scholars have calculated that there was no shortage of protein among the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico.[89]

Crafts and trades

[edit]

The excess supply of food products allowed a significant portion of the Aztec population to dedicate themselves to trades other than food production. Apart from taking care of domestic food production, women weaved textiles from agave fibers and cotton. Men also engaged in craft specializations such as the production of ceramics and obsidian and flint tools and of luxury goods such as beadwork, featherwork, and the elaboration of tools and musical instruments. Sometimes entire calpollis specialized in a single craft, and in some archeological sites large neighborhoods have been found where- only a single craft specialty was practiced.[90][91]

The Aztecs did not produce much metalwork but did have knowledge of basic smelting technology for gold, and they combined gold with precious stones such as jade and turquoise. Copper products were generally imported from the Tarascans of Michoacan.[92]

Trade and distribution

[edit]

Products were distributed through a network of markets; some markets specialized in a single commodity (e.g., the dog market of Acolman), and other general markets with the presence of many different goods. Markets were highly organized with a system of supervisors taking care that only authorized merchants were permitted to sell their goods, and punishing those who cheated their customers or sold substandard or counterfeit goods. A typical town would have a weekly market (every five days), while larger cities held markets every day. Cortés reported that the central market of Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan's sister city, was visited by 60,000 people daily. Some sellers in the markets were petty vendors; farmers might sell some of their produce, potters sold their vessels, and so on. Other vendors were professional merchants who traveled from market to market seeking profits.[93]

The pochteca were specialized long-distance merchants organized into exclusive guilds. They made long expeditions to all parts of Mesoamerica bringing back exotic luxury goods, and they served as the judges and supervisors of the Tlatelolco market. Although the economy of Aztec Mexico was commercialized (in its use of money, markets, and merchants), land and labor were not generally commodities for sale, though some types of land could be sold between nobles.[94] In the commercial sector of the economy, several types of money were in regular use.[95] Small purchases were made with cacao beans, which had to be imported from lowland areas. In Aztec marketplaces, a small rabbit was worth 30 beans, a turkey egg cost three beans, and a tamal cost a single bean. For larger purchases, standardized lengths of cotton cloth, called quachtli, were used. There were different grades of quachtli, ranging in value from 65 to 300 cacao beans. About 20 quachtli could support a commoner for one year in Tenochtitlan.[96]

Taxation

[edit]

Another form of distribution of goods was through the payment of taxes. When an altepetl was conquered, the victor imposed a yearly tax, usually paid in the form of whichever local product was most valuable or treasured. Several pages from the Codex Mendoza list subject towns along with the goods they supplied, which included not only luxuries such as feathers, adorned suits, and greenstone beads, but more practical goods such as cloth, firewood, and food. Taxes were usually paid twice or four times a year at differing times.[26]

Archaeological excavations in the Aztec-ruled provinces show that incorporation into the empire had both costs and benefits for provincial peoples. On the positive side, the empire promoted commerce and trade, and exotic goods from obsidian to bronze managed to reach the houses of both commoners and nobles. Trade partners also included the enemy Purépecha (also known as Tarascans), a source of bronze tools and jewelry. On the negative side, imperial taxes imposed a burden on commoner households, who had to increase their work to pay their share of taxes. Nobles, on the other hand, often made out well under the imperial rule because of the indirect nature of imperial organization. The empire had to rely on local kings and nobles and offered them privileges for their help in maintaining order and keeping the tax revenue flowing.[97]

Urbanism

[edit]Aztec society combined a relatively simple agrarian rural tradition with the development of a truly urbanized society with a complex system of institutions, specializations, and hierarchies. The urban tradition in Mesoamerica was developed during the classic period with major urban centers such as Teotihuacan with a population well above 100,000, and, at the time of the rise of the Aztecs, the urban tradition was ingrained in Mesoamerican society, with urban centers serving major religious, political and economic functions for the entire population.[98]

Mexico-Tenochtitlan

[edit]

The capital city of the Aztec empire was Tenochtitlan, now the site of modern-day Mexico City. Built on a series of islets in Lake Texcoco, the city plan was based on a symmetrical layout that was divided into four city sections called campan (directions). Tenochtitlan was built according to a fixed plan and centered on the ritual precinct, where the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan rose 50 meters (160 ft) above the city. Houses were made of wood and loam, and roofs were made of reed, although pyramids, temples, and palaces were generally made of stone. The city was interlaced with canals, which were useful for transportation. Anthropologist Eduardo Noguera estimated the population at 200,000 based on the house count and merging the population of Tlatelolco (once an independent city, but later became a suburb of Tenochtitlan).[88] If one includes the surrounding islets and shores surrounding Lake Texcoco, estimates range from 300,000 to 700,000 inhabitants. Michael E. Smith gives a somewhat smaller figure of 212,500 inhabitants of Tenochtitlan based on an area of 1,350 hectares (3,300 acres) and a population density of 157 inhabitants per hectare (60/acre). The second largest city in the valley of Mexico in the Aztec period was Texcoco with some 25,000 inhabitants dispersed over 450 hectares (1,100 acres).[99]

The center of Tenochtitlan was the sacred precinct, a walled-off square area that housed the Great Temple, temples for other deities, the ballcourt, the calmecac (a school for nobles), a skull rack tzompantli, displaying the skulls of sacrificial victims, houses of the warrior orders and a merchants palace. Around the sacred precinct were the royal palaces built by the tlatoanis.[100]

The Great Temple

[edit]

The centerpiece of Tenochtitlan was the Templo Mayor, the Great Temple, a large stepped pyramid with a double staircase leading up to two twin shrines – one dedicated to Tlaloc, the other to Huitzilopochtli. This was where most of the human sacrifices were carried out during the ritual festivals and the bodies of sacrificial victims were thrown down the stairs. The temple was enlarged in several stages, and most of the Aztec rulers made a point of adding a further stage, each with a new dedication and inauguration. The temple has been excavated in the center of Mexico City and the rich dedicatory offerings are displayed in the Museum of the Templo Mayor.[101]

Archeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, in his essay Symbolism of the Templo Mayor, posits that the orientation of the temple is indicative of the totality of the vision the Mexica had of the universe (cosmovision). He states that the "principal center, or navel, where the horizontal and vertical planes intersect, that is, the point from which the heavenly or upper plane and the plane of the Underworld begin and the four directions of the universe originate, is the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan". Matos Moctezuma supports his supposition by claiming that the temple acts as an embodiment of a living myth where "all sacred power is concentrated and where all the levels intersect".[102][103]

Other major city-states

[edit]Other major Aztec cities were some of the previous city-state centers around the lake including Tenayuca, Azcapotzalco, Texcoco, Colhuacan, Tlacopan, Chapultepec, Coyoacan, Xochimilco, and Chalco. In the Puebla Valley, Cholula was the largest city with the largest pyramid temple in Mesoamerica, while the confederacy of Tlaxcala consisted of four smaller cities. In Morelos, Cuahnahuac was a major city of the Nahuatl-speaking Tlahuica tribe, and Tollocan in the Toluca Valley was the capital of the Matlatzinca tribe which included Nahuatl speakers as well as speakers of Otomi and the language today called Matlatzinca. Most Aztec cities had a similar layout with a central plaza with a major pyramid with two staircases and a double temple oriented toward the west.[98]

Religion

[edit]Nahuas' metaphysics centers around teotl, "a single, dynamic, vivifying, eternally self-generating and self-regenerating sacred power, energy or force."[104] This is conceptualized in a kind of monistic pantheism[105] as manifest in the supreme god Ometeotl,[106] as well as a large pantheon of lesser gods and idealizations of natural phenomena such as stars and fire.[107] Priests and educated upper classes held more monistic views, while the popular religion of the uneducated tended to embrace the polytheistic and mythological aspects.[108]

In common with many other indigenous Mesoamerican civilizations, the Aztecs put great ritual emphasis on calendrics, and scheduled festivals, government ceremonies, and even war around key transition dates in the Aztec calendar. Public ritual practices could involve food, storytelling, and dance, as well as ceremonial warfare, the Mesoamerican ballgame, and human sacrifice, as a manner of payment for, or even effecting, the continuation of the days and the cycle of life.[109][110]

Deities

[edit]

The four main deities worshiped by the Aztecs were Tlaloc, Huitzilopochtli, Quetzalcoatl, and Tezcatlipoca. Tlaloc is a rain and storm deity; Huitzilopochtli, a solar and martial deity and the tutelary deity of the Mexica tribe; Quetzalcoatl, a wind, sky, and star deity and cultural hero; and Tezcatlipoca, a deity of the night, magic, prophecy, and fate. The Great Temple in Tenochtitlan had two shrines on its top, one dedicated to Tlaloc, the other to Huitzilopochtli. The two shrines represented two sacred mountains: the left one was Tonacatepetl, the Hill of Sustenance, whose patron god was Tlaloc, and the right one was Coatepec, whose patron god was Huitzilopochtli.[111] Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca each had separate temples within the religious precinct close to the Great Temple, and the high priests of the Great Temple were named "Quetzalcoatl Tlamacazqueh". Other major deities were Tlaltecutli or Coatlicue (a female earth deity); the deity couple Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl (associated with life and sustenance); Mictlantecutli and Mictlancihuatl, a male and female couple of deities that represented the underworld and death; Chalchiutlicue (a female deity of lakes and springs); Xipe Totec (a deity of fertility and the natural cycle); Huehueteotl or Xiuhtecuhtli (a fire god); Tlazolteotl (a female deity tied to childbirth and sexuality); and Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal (gods of song, dance and games). In some regions, particularly Tlaxcala, Mixcoatl or Camaxtli was the main tribal deity. A few sources mention a binary deity, Ometeotl, who may have been a god of the duality between life and death, male and female, and who may have incorporated Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl.[112] Some historians argue against the notion that Ometeotl was a dual god, claiming that scholars are applying their preconceived ideas onto translated texts.[113] Apart from the major deities, there were dozens of minor deities each associated with an element or concept, and as the Aztec empire grew so did their pantheon because they adopted and incorporated the local deities of conquered people into their own. Additionally, the major gods had many alternative manifestations or aspects, creating small families of gods with related aspects.[114]

Mythology and worldview

[edit]

Aztec mythology is known from many sources written down in the colonial period. One set of myths, called Legend of the Suns, describes the creation of four successive suns, or periods, each ruled by a different deity and inhabited by a different group of beings. Each period ends in a cataclysmic destruction that sets the stage for the next period to begin. In this process, the deities Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl appear as adversaries, each destroying the creations of the other. The current Sun, the fifth, was created when a minor deity sacrificed himself on a bonfire and turned into the sun, but the sun only begins to move once the other deities sacrifice themselves and offer it their life force.[116]

In another myth of how the earth was created, Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl appear as allies, defeating a giant crocodile Cipactli, and requiring her to become the earth, allowing humans to carve into her flesh and plant their seeds, on the condition that in return they will offer blood to her. In the story of the creation of humanity, Quetzalcoatl travels with his twin Xolotl to the underworld and brings back bones which are then ground like corn on a metate by the goddess Cihuacoatl, the resulting dough is given human form and comes to life when Quetzalcoatl imbues it with his blood.[117]

Huitzilopochtli is the deity tied to the Mexica tribe and he figures in the story of the origin and migrations of the tribe. On their journey, Huitzilopochtli, in the form of a deity bundle carried by the Mexica priest, continuously spurs the tribe by pushing them into conflict with their neighbors whenever they are settled in a place. In another myth, Huitzilopochtli defeats and dismembers his sister the lunar deity Coyolxauhqui, and her four hundred brothers at the hill of Coatepetl. The southern side of the Great Temple, also called Coatepetl, was a representation of this myth, and at the foot of the stairs lay a large stone monolith carved with a representation of the dismembered goddess.[118]

Calendar

[edit]

Aztec religious life was organized around the calendars. Like most Mesoamerican people, the Aztecs used two calendars simultaneously: a ritual calendar of 260 days called the tonalpohualli and a solar calendar of 365 days called the xiuhpohualli. Each day had a name and number in both calendars, and the combination of two dates was unique within 52 years. The tonalpohualli was mostly used for divinatory purposes and it consisted of 20-day signs and number coefficients of 1–13 that cycled in a fixed order. The xiuhpohualli was made up of 18 "months" of 20 days, and with a remainder of five "void" days at the end of a cycle before the new xiuhpohualli cycle began. Each 20-day month was named after the specific ritual festival that began the month, many of which contained a relation to the agricultural cycle. Whether, and how, the Aztec calendar was corrected for leap year is a matter of discussion among specialists. The monthly rituals involved the entire population as rituals were performed in each household, in the calpolli temples, and the main sacred precinct. Many festivals involved different forms of dancing, as well as the reenactment of mythical narratives by deity impersonators and the offering of sacrifice, in the form of food, animals, and human victims.[119]

Every 52 years, the two calendars reached their shared starting point and a new calendar cycle began. This calendar event was celebrated with a ritual known as Xiuhmolpilli or the New Fire Ceremony. In this ceremony, old pottery was broken in all homes and all fires in the Aztec realm were put out. Then a new fire was drilled over the breast of a sacrificial victim and runners brought the new fire to the different calpolli communities where fire was redistributed to each home. The night without fire was associated with the fear that star demons, tzitzimimeh, might descend and devour the earth – ending the fifth period of the sun.[120]

Human sacrifice and cannibalism

[edit]

To the Aztecs, death was instrumental in the perpetuation of creation, and gods and humans alike had the responsibility of sacrificing themselves to allow life to continue. As described in the myth of creation above, humans were understood to be responsible for the sun's continued revival, as well as for paying the earth for its continued fertility. Blood sacrifice in various forms was conducted. Both humans and animals were sacrificed, depending on the god to be placated and the ceremony being conducted, and priests of some gods were sometimes required to provide their blood through self-mutilation. It is known that some rituals included acts of cannibalism, with the captor and his family consuming part of the flesh of their sacrificed captives, but it is not known how widespread this practice was.[121][122]

While human sacrifice was practiced throughout Mesoamerica, the Aztecs, according to their accounts, brought this practice to an unprecedented level. For example, for the reconsecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, Aztec and Spanish sources later said that 80,400 prisoners were sacrificed over four days, reportedly by Ahuitzotl, the Great Speaker himself. This number, however, is considered by many scholars as wildly exaggerated. Other estimates place the number of human sacrifices at between 1,000 and 20,000 annually.[123][124]

The scale of Aztec human sacrifice has provoked many scholars to consider what may have been the driving factor behind this aspect of Aztec religion. In the 1970s, Michael Harner and Marvin Harris argued that the motivation behind human sacrifice among the Aztecs was the cannibalization of the sacrificial victims, depicted for example in Codex Magliabechiano. Harner claimed that very high population pressure and an emphasis on maize agriculture, without domesticated herbivores, led to a deficiency of essential amino acids among the Aztecs.[125] While there is universal agreement that the Aztecs practiced sacrifice, there is a lack of scholarly consensus as to whether cannibalism was widespread. Harris, the author of Cannibals and Kings (1977), has propagated the claim, originally proposed by Harner, that the flesh of the victims was a part of an aristocratic diet as a reward since the Aztec diet was lacking in proteins. These claims have been refuted by Bernard Ortíz Montellano who, in his studies of Aztec health, diet, and medicine, demonstrates that while the Aztec diet was low in animal proteins, it was rich in vegetable proteins. Ortiz also points to the preponderance of human sacrifice during periods of food abundance following harvests compared to periods of food scarcity, the insignificant quantity of human protein available from sacrifices, and the fact that aristocrats already had easy access to animal protein.[126][123] Today, many scholars point to ideological explanations of the practice, noting how the public spectacle of sacrificing warriors from conquered states was a major display of political power, supporting the claim of the ruling classes to divine authority.[127] It also served as an important deterrent against rebellion by subjugated polities against the Aztec state, and such deterrents were crucial for the loosely organized empire to cohere.[128]

Art and cultural production

[edit]The Aztecs greatly appreciated the toltecayotl (arts and fine craftsmanship) of the Toltecs, who predated the Aztecs in central Mexico. The Aztecs considered Toltec productions to represent the finest state of culture. The fine arts included writing and painting, singing and composing poetry, carving sculptures and producing mosaics, making fine ceramics, producing complex featherwork, and working metals, including copper and gold. Artisans of the fine arts were referred to collectively as tolteca (Toltec).[129]

-

Urban standard details; Mexico-Tenochtitlan's Calmecac stone wall remnants in Centro Cultural de España archaeological site (Mexico City)

-

The Mask of Xiuhtecuhtli; 1400–1521; cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, mother-of-pearl, conch shell, cinnabar; height: 16.8 cm (6.6 in), width: 15.2 cm (6.0 in); British Museum (London)

-

Double-headed serpent; 1450–1521; Spanish cedar wood (Cedrela odorata), turquoise, shell, traces of gilding & 2 resins are used as adhesive (pine resin and Bursera resin); height: 20.3 cm (8.0 in), width: 43.3 cm (17.0 in), depth: 5.9 cm (2.3 in); British Museum

-

Page 12 of the Codex Borbonicus, (in the big square): Tezcatlipoca (night and fate) and Quetzalcoatl (feathered serpent); before 1500; bast fiber paper; height: 38 cm (15 in), length of the full manuscript: 142 cm (56 in); Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale (Paris)

-

Aztec calendar stone; 1502–1521; basalt; diameter: 3.58 m (11.7 ft); thick: 98 cm (39 in); discovered on 17 December 1790 during repairs on the Mexico City Cathedral; National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City)

-

Tlāloc effigy vessel; 1440–1469; painted earthenware; height: 35 cm (14 in); Templo Mayor Museum (Mexico City)

-

Kneeling female figure; 15th–early 16th century; painted stone; overall: 54.61 cm × 26.67 cm (21.50 in × 10.50 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Frog-shaped necklace ornaments; 15th–early 16th century; gold; height: 2.1 cm (0.83 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Writing and iconography

[edit]

The Aztecs did not have a fully developed writing system like the Maya; however, like the Maya and Zapotec, they did use a writing system that combined logographic signs with phonetic syllable signs. Logograms would, for example, be the use of an image of a mountain to signify the word tepetl, "mountain", whereas a phonetic syllable sign would be the use of an image of a tooth tlantli to signify the syllable tla in words unrelated to teeth. The combination of these principles allowed the Aztecs to represent the sounds of names of persons and places. Narratives tended to be represented through sequences of images, using various iconographic conventions such as footprints to show paths, temples on fire to show conquest events, etc.[130]

Epigrapher Alfonso Lacadena has demonstrated that the different syllable signs used by the Aztecs almost enabled the representation of all the most frequent syllables of the Nahuatl language (with some notable exceptions),[131] but some scholars have argued that such a high degree of phonetics was only achieved after the conquest when the Aztecs had been introduced to the principles of phonetic writing by the Spanish.[132] Other scholars, notably Gordon Whittaker, have argued that the syllabic and phonetic aspects of Aztec writing were considerably less systematic and more creative than Lacadena's proposal suggests, arguing that Aztec writing never coalesced into a strictly syllabic system such as the Maya writing, but rather used a wide range of different types of phonetic signs.[133]

The image to the right demonstrates the use of phonetic signs for writing place names in the colonial Aztec Codex Mendoza. The uppermost place is "Mapachtepec", meaning literally "Hill of the Raccoon", but the glyph includes the phonetic prefixes ma (hand) and pach (moss) over a mountain tepetl spelling the word "mapach" ("raccoon") phonetically instead of logographically. The other two place names, Mazatlan ("Place of Many Deer") and Huitztlan ("Place of many thorns") use the phonetic element tlan represented by a tooth (tlantli) combined with a deer head to spell maza (mazatl = deer) and a thorn (huitztli) to spell huitz.[134]

Music, song and poetry

[edit]

Song and poetry were highly regarded; there were presentations and poetry contests at most of the Aztec festivals. There were also dramatic presentations that included players, musicians, and acrobats. There were several different genres of cuicatl (song): Yaocuicatl was devoted to war and the god(s) of war, Teocuicatl to the gods and creation myths and adoration of said figures, xochicuicatl to flowers (a symbol of poetry itself and indicative of the highly metaphorical nature of poetry that often used duality to convey multiple layers of meaning). "Prose" was tlahtolli, also with its different categories and divisions.[135][136]

A key aspect of Aztec poetics was the use of parallelism, using a structure of embedded couplets to express different perspectives on the same element.[137] Some such couplets were diphrasisms, conventional metaphors whereby an abstract concept was expressed metaphorically by using two more concrete concepts. For example, the Nahuatl expression for "poetry" was in xochitl in cuicatl a dual term meaning "the flower, the song".[138]

A remarkable amount of this poetry survives, having been collected during the era of the conquest. In some cases poetry is attributed to individual authors, such as Nezahualcoyotl, tlatoani of Texcoco, and Cuacuauhtzin, Lord of Tepechpan, but whether these attributions reflect actual authorship is a matter of opinion. An important collection of such poems is Romances de los señores de la Nueva España, collected (Tezcoco 1582), probably by Juan Bautista de Pomar,[nb 9] and the Cantares Mexicanos.[139] Both men and women were poets in Aztec society, illustrating pre-Hispanic Mexico's gender parallelism in upper-class society.[140] One famous female poet is Macuilxochitzin, whose work primarily focused on the Aztec conquest.[141]

Ceramics

[edit]The Aztecs produced ceramics of different types. Common are orange wares, which are orange or buff burnished ceramics with no slip. Red wares are ceramics with a reddish slip. Polychrome ware is ceramics with a white or orange slip, with painted designs in orange, red, brown, and/or black. Very common is "black on orange" ware which is orange ware decorated with painted designs in black.[142][143][144]

Aztec black-on-orange ceramics are chronologically classified into four phases: Aztec I and II corresponding to c. 1100–1350 (early Aztec period), Aztec III (c. 1350–1520), and the last phase Aztec IV was the early colonial period. Aztec I is characterized by floral designs and day-name glyphs; Aztec II is characterized by a stylized grass design above calligraphic designs such as S-curves or loops; Aztec III is characterized by very simple line designs; Aztec IV continues some pre-Columbian designs but adds European influenced floral designs. There were local variations on each of these styles, and archeologists continue to refine the ceramic sequence.[143]

Typical vessels for everyday use were clay griddles for cooking (comalli), bowls and plates for eating (caxitl), pots for cooking (comitl), molcajetes or mortar-type vessels with slashed bases for grinding chilli (molcaxitl), and different kinds of braziers, tripod dishes, and biconical goblets. Vessels were fired in simple updraft kilns or even in open firing in pit kilns at low temperatures.[143] Polychrome ceramics were imported from the Cholula region (also known as Mixteca-Puebla style), and these wares were highly prized as a luxury ware, whereas the local black on orange styles were also for everyday use.[145]

Painted art

[edit]

Aztec painted art was produced on animal skin (mostly deer), on cotton lienzos, and amate paper made from bark (e.g., from Trema micrantha or Ficus aurea), it was also produced on ceramics and carved in wood and stone. The surface of the material was often first treated with gesso to make the images stand out more clearly. The art of painting and writing was known in Nahuatl by the metaphor in tlilli, in tlapalli – meaning "the black ink, the red pigment".[146][147]

There are few extant Aztec-painted books. Of these, none are conclusively confirmed to have been created before the conquest, but several codices must have been painted either right before the conquest or very soon after – before traditions for producing them were much disturbed. Even if some codices may have been produced after the conquest, there is good reason to think that they may have been copied from pre-Columbian originals by scribes. The Codex Borbonicus is considered by some to be the only extant Aztec codex produced before the conquest – it is a calendric codex describing the day and month counts indicating the patron deities of the different periods.[28] Others consider it to have stylistic traits suggesting a post-conquest production.[148]

Some codices were produced post-conquest, sometimes commissioned by the colonial government, for example, Codex Mendoza, were painted by Aztec tlacuilos (codex creators), but under the control of Spanish authorities, who also sometimes commissioned codices describing pre-colonial religious practices, for example, Codex Ríos. After the conquest, codices with calendric or religious information were sought out and systematically destroyed by the church – whereas other types of painted books, particularly historical narratives, and tax lists continued to be produced.[28] Although depicting Aztec deities and describing religious practices also shared by the Aztecs of the Valley of Mexico, the codices produced in Southern Puebla near Cholula, are sometimes not considered to be Aztec codices, because they were produced outside of the Aztec "heartland".[28] Karl Anton Nowotny, nevertheless considered that the Codex Borgia, painted in the area around Cholula and using a Mixtec style, was the "most significant work of art among the extant manuscripts".[149]

The first Aztec murals were from Teotihuacan.[150] Most of our current Aztec murals were found in Templo Mayor.[150] The Aztec capital was decorated with elaborate murals. In Aztec murals, humans are represented like they are represented in the codices. One mural discovered in Tlateloco depicts an old man and an old woman. This may represent the gods Cipactonal and Oxomico.

Sculpture

[edit]

Sculptures were carved in stone and wood, but few wood carvings have survived.[151] Aztec stone sculptures exist in many sizes from small figurines and masks to large monuments, and are characterized by a high quality of craftsmanship.[152] Many sculptures were carved in highly realistic styles, for example realistic sculpture of animals.[153]

In Aztec artwork some monumental stone sculptures have been preserved, such sculptures usually functioned as adornments for religious architecture. Particularly famous monumental rock sculpture includes the so-called Aztec "Sunstone" or Calendarstone discovered in 1790; also discovered in 1790 excavations of the Zócalo was the 2.7-meter-tall (8.9 ft) Coatlicue statue made of andesite, representing a serpentine chthonic goddess with a skirt made of rattlesnakes. The Coyolxauhqui Stone representing the dismembered goddess Coyolxauhqui, found in 1978, was at the foot of the staircase leading up to the Great Temple in Tenochtitlan.[154] Two important types of sculpture are unique to the Aztecs, and related to the context of ritual sacrifice: the cuauhxicalli or "eagle vessel", large stone bowls often shaped like eagles or jaguars used as a receptacle for extracted human hearts; the temalacatl, a monumental carved stone disk to which war captives were tied and sacrificed in a form of gladiatorial combat. The most well-known examples of this type of sculpture are the Stone of Tizoc and the Stone of Motecuzoma I, both carved with images of warfare and conquest by specific Aztec rulers. Many smaller stone sculptures depicting deities also exist. The style used in religious sculpture was rigid stances likely meant to create a powerful experience for the onlooker.[153] Although Aztec stone sculptures are now displayed in museums as unadorned rock, they were originally painted in vivid polychrome color, sometimes covered first with a base coat of plaster.[155] Early Spanish conquistador accounts also describe stone sculptures as having been decorated with precious stones and metal, inserted into the plaster.[153]

Featherwork

[edit]