Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Combinatorics

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2022) |

| Part of a series on | ||

| Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

| ||

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and as an end to obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many applications ranging from logic to statistical physics and from evolutionary biology to computer science.

Combinatorics is well known for the breadth of the problems it tackles. Combinatorial problems arise in many areas of pure mathematics, notably in algebra, probability theory, topology, and geometry,[1] as well as in its many application areas. Many combinatorial questions have historically been considered in isolation, giving an ad hoc solution to a problem arising in some mathematical context. In the later twentieth century, however, powerful and general theoretical methods were developed, making combinatorics into an independent branch of mathematics in its own right.[2] One of the oldest and most accessible parts of combinatorics is graph theory, which by itself has numerous natural connections to other areas. Combinatorics is used frequently in computer science to obtain formulas and estimates in the analysis of algorithms.

Definition

[edit]The full scope of combinatorics is not universally agreed upon.[3] According to H. J. Ryser, a definition of the subject is difficult because it crosses so many mathematical subdivisions.[4] Insofar as an area can be described by the types of problems it addresses, combinatorics is involved with:

- the enumeration (counting) of specified structures, sometimes referred to as arrangements or configurations in a very general sense, associated with finite systems,

- the existence of such structures that satisfy certain given criteria,

- the construction of these structures, perhaps in many ways, and

- optimization: finding the "best" structure or solution among several possibilities, be it the "largest", "smallest" or satisfying some other optimality criterion.

Leon Mirsky has said: "combinatorics is a range of linked studies which have something in common and yet diverge widely in their objectives, their methods, and the degree of coherence they have attained."[5] One way to define combinatorics is, perhaps, to describe its subdivisions with their problems and techniques. This is the approach that is used below. However, there are also purely historical reasons for including or not including some topics under the combinatorics umbrella.[6] Although primarily concerned with finite systems, some combinatorial questions and techniques can be extended to an infinite (specifically, countable) but discrete setting.

History

[edit]

Basic combinatorial concepts and enumerative results appeared throughout the ancient world. The earliest recorded use of combinatorial techniques comes from problem 79 of the Rhind papyrus, which dates to the 16th century BC. The problem concerns a certain geometric series, and has similarities to Fibonacci's problem of counting the number of compositions of 1s and 2s that sum to a given total.[7] Indian physician Sushruta asserts in Sushruta Samhita that 63 combinations can be made out of 6 different tastes, taken one at a time, two at a time, etc., thus computing all 26 − 1 possibilities. Greek historian Plutarch discusses an argument between Chrysippus (3rd century BCE) and Hipparchus (2nd century BCE) of a rather delicate enumerative problem, which was later shown to be related to Schröder–Hipparchus numbers.[8][9][10] Earlier, in the Ostomachion, Archimedes (3rd century BCE) may have considered the number of configurations of a tiling puzzle,[11] while combinatorial interests possibly were present in lost works by Apollonius.[12][13]

In the Middle Ages, combinatorics continued to be studied, largely outside of the European civilization. The Indian mathematician Mahāvīra (c. 850) provided formulae for the number of permutations and combinations,[14][15] and these formulas may have been familiar to Indian mathematicians as early as the 6th century CE.[16] The philosopher and astronomer Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra (c. 1140) established the symmetry of binomial coefficients, while a closed formula was obtained later by the talmudist and mathematician Levi ben Gerson (better known as Gersonides), in 1321.[17] The arithmetical triangle—a graphical diagram showing relationships among the binomial coefficients—was presented by mathematicians in treatises dating as far back as the 10th century, and would eventually become known as Pascal's triangle. Later, in Medieval England, campanology provided examples of what is now known as Hamiltonian cycles in certain Cayley graphs on permutations.[18][19]

During the Renaissance, together with the rest of mathematics and the sciences, combinatorics enjoyed a rebirth. Works of Pascal, Newton, Jacob Bernoulli and Euler became foundational in the emerging field. In modern times, the works of J.J. Sylvester (late 19th century) and Percy MacMahon (early 20th century) helped lay the foundation for enumerative and algebraic combinatorics. Graph theory also enjoyed an increase of interest at the same time, especially in connection with the four color problem.

In the second half of the 20th century, combinatorics enjoyed a rapid growth, which led to establishment of dozens of new journals and conferences in the subject.[20] In part, the growth was spurred by new connections and applications to other fields, ranging from algebra to probability, from functional analysis to number theory, etc. These connections shed the boundaries between combinatorics and parts of mathematics and theoretical computer science, but at the same time led to a partial fragmentation of the field.

Approaches and subfields of combinatorics

[edit]Enumerative combinatorics

[edit]

Enumerative combinatorics is the most classical area of combinatorics and concentrates on counting the number of certain combinatorial objects. Although counting the number of elements in a set is a rather broad mathematical problem, many of the problems that arise in applications have a relatively simple combinatorial description. Fibonacci numbers is the basic example of a problem in enumerative combinatorics. The twelvefold way provides a unified framework for counting permutations, combinations and partitions.

Analytic combinatorics

[edit]Analytic combinatorics concerns the enumeration of combinatorial structures using tools from complex analysis and probability theory. In contrast with enumerative combinatorics, which uses explicit combinatorial formulae and generating functions to describe the results, analytic combinatorics aims at obtaining asymptotic formulae.

Partition theory

[edit]

Partition theory studies various enumeration and asymptotic problems related to integer partitions, and is closely related to q-series, special functions and orthogonal polynomials. Originally a part of number theory and analysis, it is now considered a part of combinatorics or an independent field. It incorporates the bijective approach and various tools in analysis and analytic number theory and has connections with statistical mechanics. Partitions can be graphically visualized with Young diagrams or Ferrers diagrams. They occur in a number of branches of mathematics and physics, including the study of symmetric polynomials and of the symmetric group and in group representation theory in general.

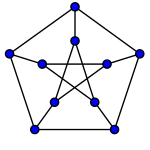

Graph theory

[edit]

Graphs are fundamental objects in combinatorics. Considerations of graph theory range from enumeration (e.g., the number of graphs on n vertices with k edges) to existing structures (e.g., Hamiltonian cycles) to algebraic representations (e.g., given a graph G and two numbers x and y, does the Tutte polynomial TG(x,y) have a combinatorial interpretation?). Although there are very strong connections between graph theory and combinatorics, they are sometimes thought of as separate subjects.[21] While combinatorial methods apply to many graph theory problems, the two disciplines are generally used to seek solutions to different types of problems.

Design theory

[edit]Design theory is a study of combinatorial designs, which are collections of subsets with certain intersection properties. Block designs are combinatorial designs of a special type. This area is one of the oldest parts of combinatorics, such as in Kirkman's schoolgirl problem proposed in 1850. The solution of the problem is a special case of a Steiner system, which play an important role in the classification of finite simple groups. The area has further connections to coding theory and geometric combinatorics.

Combinatorial design theory can be applied to the area of design of experiments. Some of the basic theory of combinatorial designs originated in the statistician Ronald Fisher's work on the design of biological experiments. Modern applications are also found in a wide gamut of areas including finite geometry, tournament scheduling, lotteries, mathematical chemistry, mathematical biology, algorithm design and analysis, networking, group testing and cryptography.[22]

Finite geometry

[edit]Finite geometry is the study of geometric systems having only a finite number of points. Structures analogous to those found in continuous geometries (Euclidean plane, real projective space, etc.) but defined combinatorially are the main items studied. This area provides a rich source of examples for design theory. It should not be confused with discrete geometry (combinatorial geometry).

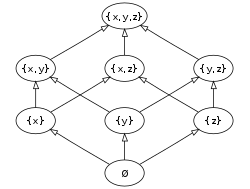

Order theory

[edit]

Order theory is the study of partially ordered sets, both finite and infinite. It provides a formal framework for describing statements such as "this is less than that" or "this precedes that". Various examples of partial orders appear in algebra, geometry, number theory and throughout combinatorics and graph theory. Notable classes and examples of partial orders include lattices and Boolean algebras.

Matroid theory

[edit]Matroid theory abstracts part of geometry. It studies the properties of sets (usually, finite sets) of vectors in a vector space that do not depend on the particular coefficients in a linear dependence relation. Not only the structure but also enumerative properties belong to matroid theory. Matroid theory was introduced by Hassler Whitney and studied as a part of order theory. It is now an independent field of study with a number of connections with other parts of combinatorics.

Extremal combinatorics

[edit]Extremal combinatorics studies how large or how small a collection of finite objects (numbers, graphs, vectors, sets, etc.) can be, if it has to satisfy certain restrictions. Much of extremal combinatorics concerns classes of set systems; this is called extremal set theory. For instance, in an n-element set, what is the largest number of k-element subsets that can pairwise intersect one another? What is the largest number of subsets of which none contains any other? The latter question is answered by Sperner's theorem, which gave rise to much of extremal set theory.

The types of questions addressed in this case are about the largest possible graph which satisfies certain properties. For example, the largest triangle-free graph on 2n vertices is a complete bipartite graph Kn,n. Often it is too hard even to find the extremal answer f(n) exactly and one can only give an asymptotic estimate.

Ramsey theory is another part of extremal combinatorics. It states that any sufficiently large configuration will contain some sort of order. It is an advanced generalization of the pigeonhole principle.

Probabilistic combinatorics

[edit]

In probabilistic combinatorics, the questions are of the following type: what is the probability of a certain property for a random discrete object, such as a random graph? For instance, what is the average number of triangles in a random graph? Probabilistic methods are also used to determine the existence of combinatorial objects with certain prescribed properties (for which explicit examples might be difficult to find) by observing that the probability of randomly selecting an object with those properties is greater than 0. This approach (often referred to as the probabilistic method) proved highly effective in applications to extremal combinatorics and graph theory. A closely related area is the study of finite Markov chains, especially on combinatorial objects. Here again probabilistic tools are used to estimate the mixing time.[clarification needed]

Often associated with Paul Erdős, who did the pioneering work on the subject, probabilistic combinatorics was traditionally viewed as a set of tools to study problems in other parts of combinatorics. The area recently grew to become an independent field of combinatorics.

Algebraic combinatorics

[edit]

Algebraic combinatorics is an area of mathematics that employs methods of abstract algebra, notably group theory and representation theory, in various combinatorial contexts and, conversely, applies combinatorial techniques to problems in algebra. Algebraic combinatorics has come to be seen more expansively as an area of mathematics where the interaction of combinatorial and algebraic methods is particularly strong and significant. Thus the combinatorial topics may be enumerative in nature or involve matroids, polytopes, partially ordered sets, or finite geometries. On the algebraic side, besides group and representation theory, lattice theory and commutative algebra are common.

Combinatorics on words

[edit]

Combinatorics on words deals with formal languages. It arose independently within several branches of mathematics, including number theory, group theory and probability. It has applications to enumerative combinatorics, fractal analysis, theoretical computer science, automata theory, and linguistics. While many applications are new, the classical Chomsky–Schützenberger hierarchy of classes of formal grammars is perhaps the best-known result in the field.

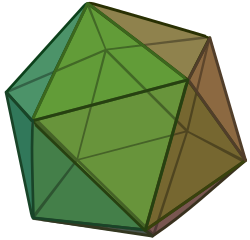

Geometric combinatorics

[edit]

Geometric combinatorics is related to convex and discrete geometry. It asks, for example, how many faces of each dimension a convex polytope can have. Metric properties of polytopes play an important role as well, e.g. the Cauchy theorem on the rigidity of convex polytopes. Special polytopes are also considered, such as permutohedra, associahedra and Birkhoff polytopes. Combinatorial geometry is a historical name for discrete geometry.

It includes a number of subareas such as polyhedral combinatorics (the study of faces of convex polyhedra), convex geometry (the study of convex sets, in particular combinatorics of their intersections), and discrete geometry, which in turn has many applications to computational geometry. The study of regular polytopes, Archimedean solids, and kissing numbers is also a part of geometric combinatorics. Special polytopes are also considered, such as the permutohedron, associahedron and Birkhoff polytope.

Topological combinatorics

[edit]

Combinatorial analogs of concepts and methods in topology are used to study graph coloring, fair division, partitions, partially ordered sets, decision trees, necklace problems and discrete Morse theory. It should not be confused with combinatorial topology which is an older name for algebraic topology.

Arithmetic combinatorics

[edit]Arithmetic combinatorics arose out of the interplay between number theory, combinatorics, ergodic theory, and harmonic analysis. It is about combinatorial estimates associated with arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). Additive number theory (sometimes also called additive combinatorics) refers to the special case when only the operations of addition and subtraction are involved. One important technique in arithmetic combinatorics is the ergodic theory of dynamical systems.

Infinitary combinatorics

[edit]Infinitary combinatorics, or combinatorial set theory, is an extension of ideas in combinatorics to infinite sets. It is a part of set theory, an area of mathematical logic, but uses tools and ideas from both set theory and extremal combinatorics. Some of the things studied include continuous graphs and trees, extensions of Ramsey's theorem, and Martin's axiom. Recent developments concern combinatorics of the continuum[23] and combinatorics on successors of singular cardinals.[24]

Gian-Carlo Rota used the name continuous combinatorics[25] to describe geometric probability, since there are many analogies between counting and measure.

Related fields

[edit]

Combinatorial optimization

[edit]Combinatorial optimization is the study of optimization on discrete and combinatorial objects. It started as a part of combinatorics and graph theory, but is now viewed as a branch of applied mathematics and computer science, related to operations research, algorithm theory and computational complexity theory.

Coding theory

[edit]Coding theory started as a part of design theory with early combinatorial constructions of error-correcting codes. The main idea of the subject is to design efficient and reliable methods of data transmission. It is now a large field of study, part of information theory.

Discrete and computational geometry

[edit]Discrete geometry (also called combinatorial geometry) also began as a part of combinatorics, with early results on convex polytopes and kissing numbers. With the emergence of applications of discrete geometry to computational geometry, these two fields partially merged and became a separate field of study. There remain many connections with geometric and topological combinatorics, which themselves can be viewed as outgrowths of the early discrete geometry.

Combinatorics and dynamical systems

[edit]Combinatorial aspects of dynamical systems is another emerging field. Here dynamical systems can be defined on combinatorial objects. See for example graph dynamical system.

Combinatorics and physics

[edit]There are increasing interactions between combinatorics and physics, particularly statistical physics. Examples include an exact solution of the Ising model, and a connection between the Potts model on one hand, and the chromatic and Tutte polynomials on the other hand.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Björner and Stanley, p. 2

- ^ Lovász, László (1979). Combinatorial Problems and Exercises. North-Holland. ISBN 978-0821842621. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

In my opinion, combinatorics is now growing out of this early stage.

- ^ Pak, Igor. "What is Combinatorics?". Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Ryser 1963, p. 2

- ^ Mirsky, Leon (1979), "Book Review" (PDF), Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, New Series, 1: 380–388, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-1979-14606-8, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-26, retrieved 2021-02-04

- ^ Rota, Gian Carlo (1969). Discrete Thoughts. Birkhaüser. p. 50. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4775-9. ISBN 978-0-8176-4775-9.

... combinatorial theory has been the mother of several of the more active branches of today's mathematics, which have become independent ... . The typical ... case of this is algebraic topology (formerly known as combinatorial topology)

- ^ Biggs, Norman; Lloyd, Keith; Wilson, Robin (1995). "44". In Ronald Grahm, Martin Grötschel, László Lovász (ed.). Handbook of Combinatorics (Google book). MIT Press. pp. 2163–2188. ISBN 0262571722. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Acerbi, F. (2003). "On the shoulders of Hipparchus". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 57 (6): 465–502. doi:10.1007/s00407-003-0067-0. S2CID 122758966. Archived from the original on 2022-01-23. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ Stanley, Richard P.; "Hipparchus, Plutarch, Schröder, and Hough", American Mathematical Monthly 104 (1997), no. 4, 344–350.

- ^ Habsieger, Laurent; Kazarian, Maxim; Lando, Sergei (1998). "On the Second Number of Plutarch". The American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (5): 446. doi:10.1080/00029890.1998.12004906.

- ^ Netz, R.; Acerbi, F.; Wilson, N. "Towards a reconstruction of Archimedes' Stomachion". Sciamvs. 5: 67–99. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ^ Hogendijk, Jan P. (1986). "Arabic Traces of Lost Works of Apollonius". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 35 (3): 187–253. doi:10.1007/BF00357307. ISSN 0003-9519. JSTOR 41133783. S2CID 121613986. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

- ^ Huxley, G. (1967). "Okytokion". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 8 (3): 203. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Combinatorics", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Puttaswamy, Tumkur K. (2000). "The Mathematical Accomplishments of Ancient Indian Mathematicians". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Mathematics. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 417. ISBN 978-1-4020-0260-1. Archived from the original on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- ^ Biggs, Norman L. (1979). "The Roots of Combinatorics". Historia Mathematica. 6 (2): 109–136. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(79)90074-0.

- ^ Maistrov, L.E. (1974), Probability Theory: A Historical Sketch, Academic Press, p. 35, ISBN 978-1-4832-1863-2, archived from the original on 2021-04-16, retrieved 2015-01-25. (Translation from 1967 Russian ed.)

- ^ White, Arthur T. (1987). "Ringing the Cosets". The American Mathematical Monthly. 94 (8): 721–746. doi:10.1080/00029890.1987.12000711.

- ^ White, Arthur T. (1996). "Fabian Stedman: The First Group Theorist?". The American Mathematical Monthly. 103 (9): 771–778. doi:10.1080/00029890.1996.12004816.

- ^ See Journals in Combinatorics and Graph Theory Archived 2021-02-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sanders, Daniel P.; 2-Digit MSC Comparison Archived 2008-12-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stinson 2003, pg.1

- ^ Andreas Blass, Combinatorial Cardinal Characteristics of the Continuum, Chapter 6 in Handbook of Set Theory, edited by Matthew Foreman and Akihiro Kanamori, Springer, 2010

- ^ Eisworth, Todd (2010), Foreman, Matthew; Kanamori, Akihiro (eds.), "Successors of Singular Cardinals", Handbook of Set Theory, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 1229–1350, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5764-9_16, ISBN 978-1-4020-4843-2, retrieved 2022-08-27

- ^ "Continuous and profinite combinatorics" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

References

[edit]- Björner, Anders; and Stanley, Richard P.; (2010); A Combinatorial Miscellany

- Bóna, Miklós; (2011); A Walk Through Combinatorics (3rd ed.). ISBN 978-981-4335-23-2, 978-981-4460-00-2

- Graham, Ronald L.; Groetschel, Martin; and Lovász, László; eds. (1996); Handbook of Combinatorics, Volumes 1 and 2. Amsterdam, NL, and Cambridge, MA: Elsevier (North-Holland) and MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-07169-X

- Lindner, Charles C.; and Rodger, Christopher A.; eds. (1997); Design Theory, CRC-Press. ISBN 0-8493-3986-3.

- Riordan, John (2002) [1958], An Introduction to Combinatorial Analysis, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-42536-8

- Ryser, Herbert John (1963), Combinatorial Mathematics, The Carus Mathematical Monographs(#14), The Mathematical Association of America

- Stanley, Richard P. (1997, 1999); Enumerative Combinatorics, Volumes 1 and 2, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55309-1, 0-521-56069-1

- Stinson, Douglas R. (2003), Combinatorial Designs: Constructions and Analysis, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-95487-2

- van Lint, Jacobus H.; and Wilson, Richard M.; (2001); A Course in Combinatorics, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80340-3

External links

[edit]- "Combinatorial analysis", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Combinatorial Analysis – an article in Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- Combinatorics, a MathWorld article with many references.

- Combinatorics, from a MathPages.com portal.

- The Hyperbook of Combinatorics, a collection of math articles links.

- The Two Cultures of Mathematics by W.T. Gowers, article on problem solving vs theory building.

- "Glossary of Terms in Combinatorics" Archived 2017-08-17 at the Wayback Machine

- List of Combinatorics Software and Databases