Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dimension

View on Wikipedia

- Two points can be connected to create a line segment.

- Two parallel line segments can be connected to form a square.

- Two parallel squares can be connected to form a cube.

- Two parallel cubes can be connected to form a tesseract.

| Geometry |

|---|

|

| Geometers |

In physics and mathematics, the dimension of a mathematical space (or object) is informally defined as the minimum number of coordinates needed to specify any point within it.[1][2] Thus, a line has a dimension of one (1D) because only one coordinate is needed to specify a point on it – for example, the point at 5 on a number line. A surface, such as the boundary of a cylinder or sphere, has a dimension of two (2D) because two coordinates are needed to specify a point on it – for example, both a latitude and longitude are required to locate a point on the surface of a sphere. A two-dimensional Euclidean space is a two-dimensional space on the plane. The inside of a cube, a cylinder or a sphere is three-dimensional (3D) because three coordinates are needed to locate a point within these spaces.

In classical mechanics, space and time are different categories and refer to absolute space and time. That conception of the world is a four-dimensional space but not the one that was found necessary to describe electromagnetism. The four dimensions (4D) of spacetime consist of events that are not absolutely defined spatially and temporally, but rather are known relative to the motion of an observer. Minkowski space first approximates the universe without gravity; the pseudo-Riemannian manifolds of general relativity describe spacetime with matter and gravity. 10 dimensions are used to describe superstring theory (6D hyperspace + 4D), 11 dimensions can describe supergravity and M-theory (7D hyperspace + 4D), and the state-space of quantum mechanics is an infinite-dimensional function space.

The concept of dimension is not restricted to physical objects. High-dimensional spaces frequently occur in mathematics and the sciences. They may be Euclidean spaces or more general parameter spaces or configuration spaces such as in Lagrangian or Hamiltonian mechanics; these are abstract spaces, independent of the physical space.

In mathematics

[edit]In mathematics, the dimension of an object is, roughly speaking, the number of degrees of freedom of a point that moves on this object. In other words, the dimension is the number of independent parameters or coordinates that are needed for defining the position of a point that is constrained to be on the object. For example, the dimension of a point is zero; the dimension of a line is one, as a point can move on a line in only one direction (or its opposite); the dimension of a plane is two, etc.

The dimension is an intrinsic property of an object, in the sense that it is independent of the dimension of the space in which the object is or can be embedded. For example, a curve, such as a circle, is of dimension one, because the position of a point on a curve is determined by its signed distance along the curve to a fixed point on the curve. This is independent from the fact that a curve cannot be embedded in a Euclidean space of dimension lower than two, unless it is a line. Similarly, a surface is of dimension two, even if embedded in three-dimensional space.

The dimension of Euclidean n-space En is n. When trying to generalize to other types of spaces, one is faced with the question "what makes En n-dimensional?" One answer is that to cover a fixed ball in En by small balls of radius ε, one needs on the order of ε−n such small balls. This observation leads to the definition of the Minkowski dimension and its more sophisticated variant, the Hausdorff dimension, but there are also other answers to that question. For example, the boundary of a ball in En looks locally like En-1 and this leads to the notion of the inductive dimension. While these notions agree on En, they turn out to be different when one looks at more general spaces.

A tesseract is an example of a four-dimensional object. Whereas outside mathematics the use of the term "dimension" is as in: "A tesseract has four dimensions", mathematicians usually express this as: "The tesseract has dimension 4", or: "The dimension of the tesseract is 4".

Although the notion of higher dimensions goes back to René Descartes, substantial development of a higher-dimensional geometry only began in the 19th century, via the work of Arthur Cayley, William Rowan Hamilton, Ludwig Schläfli and Bernhard Riemann. Riemann's 1854 Habilitationsschrift, Schläfli's 1852 Theorie der vielfachen Kontinuität, and Hamilton's discovery of the quaternions and John T. Graves' discovery of the octonions in 1843 marked the beginning of higher-dimensional geometry.

The rest of this section examines some of the more important mathematical definitions of dimension.

Vector spaces

[edit]The dimension of a vector space is the number of vectors in any basis for the space, i.e. the number of coordinates necessary to specify any vector. This notion of dimension (the cardinality of a basis) is often referred to as the Hamel dimension or algebraic dimension to distinguish it from other notions of dimension.

For the non-free case, this generalizes to the notion of the length of a module.

Manifolds

[edit]The uniquely defined dimension of every connected topological manifold can be calculated. A connected topological manifold is locally homeomorphic to Euclidean n-space, in which the number n is the manifold's dimension.

For connected differentiable manifolds, the dimension is also the dimension of the tangent vector space at any point.

In geometric topology, the theory of manifolds is characterized by the way dimensions 1 and 2 are relatively elementary, the high-dimensional cases n > 4 are simplified by having extra space in which to "work"; and the cases n = 3 and 4 are in some senses the most difficult. This state of affairs was highly marked in the various cases of the Poincaré conjecture, in which four different proof methods are applied.

Complex dimension

[edit]

The dimension of a manifold depends on the base field with respect to which Euclidean space is defined. While analysis usually assumes a manifold to be over the real numbers, it is sometimes useful in the study of complex manifolds and algebraic varieties to work over the complex numbers instead. A complex number (x + iy) has a real part x and an imaginary part y, in which x and y are both real numbers; hence, the complex dimension is half the real dimension.

Conversely, in algebraically unconstrained contexts, a single complex coordinate system may be applied to an object having two real dimensions. For example, an ordinary two-dimensional spherical surface, when given a complex metric, becomes a Riemann sphere of one complex dimension.[3]

Varieties

[edit]The dimension of an algebraic variety may be defined in various equivalent ways. The most intuitive way is probably the dimension of the tangent space at any Regular point of an algebraic variety. Another intuitive way is to define the dimension as the number of hyperplanes that are needed in order to have an intersection with the variety that is reduced to a finite number of points (dimension zero). This definition is based on the fact that the intersection of a variety with a hyperplane reduces the dimension by one unless if the hyperplane contains the variety.

An algebraic set being a finite union of algebraic varieties, its dimension is the maximum of the dimensions of its components. It is equal to the maximal length of the chains of sub-varieties of the given algebraic set (the length of such a chain is the number of "").

Each variety can be considered as an algebraic stack, and its dimension as variety agrees with its dimension as stack. There are however many stacks which do not correspond to varieties, and some of these have negative dimension. Specifically, if V is a variety of dimension m and G is an algebraic group of dimension n acting on V, then the quotient stack [V/G] has dimension m − n.[4]

Krull dimension

[edit]The Krull dimension of a commutative ring is the maximal length of chains of prime ideals in it, a chain of length n being a sequence of prime ideals related by inclusion. It is strongly related to the dimension of an algebraic variety, because of the natural correspondence between sub-varieties and prime ideals of the ring of the polynomials on the variety.

For an algebra over a field, the dimension as vector space is finite if and only if its Krull dimension is 0.

Topological spaces

[edit]For any normal topological space X, the Lebesgue covering dimension of X is defined to be the smallest integer n for which the following holds: any open cover has an open refinement (a second open cover in which each element is a subset of an element in the first cover) such that no point is included in more than n + 1 elements. In this case dim X = n. For X a manifold, this coincides with the dimension mentioned above. If no such integer n exists, then the dimension of X is said to be infinite, and one writes dim X = ∞. Moreover, X has dimension −1, i.e. dim X = −1 if and only if X is empty. This definition of covering dimension can be extended from the class of normal spaces to all Tychonoff spaces merely by replacing the term "open" in the definition by the term "functionally open".

An inductive dimension may be defined inductively as follows. Consider a discrete set of points (such as a finite collection of points) to be 0-dimensional. By dragging a 0-dimensional object in some direction, one obtains a 1-dimensional object. By dragging a 1-dimensional object in a new direction, one obtains a 2-dimensional object. In general, one obtains an (n + 1)-dimensional object by dragging an n-dimensional object in a new direction. The inductive dimension of a topological space may refer to the small inductive dimension or the large inductive dimension, and is based on the analogy that, in the case of metric spaces, (n + 1)-dimensional balls have n-dimensional boundaries, permitting an inductive definition based on the dimension of the boundaries of open sets. Moreover, the boundary of a discrete set of points is the empty set, and therefore the empty set can be taken to have dimension −1.[5]

Similarly, for the class of CW complexes, the dimension of an object is the largest n for which the n-skeleton is nontrivial. Intuitively, this can be described as follows: if the original space can be continuously deformed into a collection of higher-dimensional triangles joined at their faces with a complicated surface, then the dimension of the object is the dimension of those triangles.[citation needed]

Hausdorff dimension

[edit]The Hausdorff dimension is useful for studying structurally complicated sets, especially fractals. The Hausdorff dimension is defined for all metric spaces and, unlike the dimensions considered above, can also have non-integer real values.[6] The box dimension or Minkowski dimension is a variant of the same idea. In general, there exist more definitions of fractal dimensions that work for highly irregular sets and attain non-integer positive real values.

Hilbert spaces

[edit]Every Hilbert space admits an orthonormal basis, and any two such bases for a particular space have the same cardinality. This cardinality is called the dimension of the Hilbert space. This dimension is finite if and only if the space's Hamel dimension is finite, and in this case the two dimensions coincide.

In physics

[edit]Spatial dimensions

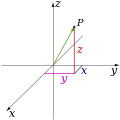

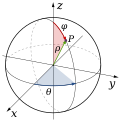

[edit]Classical physics theories describe three physical dimensions: from a particular point in space, the basic directions in which we can move are up/down, left/right, and forward/backward. Movement in any other direction can be expressed in terms of just these three. Moving down is the same as moving up a negative distance. Moving diagonally upward and forward is just as the name of the direction implies i.e., moving in a linear combination of up and forward. In its simplest form: a line describes one dimension, a plane describes two dimensions, and a cube describes three dimensions. (See Space and Cartesian coordinate system.)

Number of

dimensions |

Example co-ordinate systems | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

| |||

| 2 |

| |||

| 3 |

|

Time

[edit]A temporal dimension, or time dimension, is a dimension of time. Time is often referred to as the "fourth dimension" for this reason, but that is not to imply that it is a spatial dimension.[7] A temporal dimension is one way to measure physical change. It is perceived differently from the three spatial dimensions in that there is only one of it, and that we cannot move freely in time but subjectively move in one direction.

The equations used in physics to model reality do not treat time in the same way that humans commonly perceive it. The equations of classical mechanics are symmetric with respect to time, and equations of quantum mechanics are typically symmetric if both time and other quantities (such as charge and parity) are reversed. In these models, the perception of time flowing in one direction is an artifact of the laws of thermodynamics (we perceive time as flowing in the direction of increasing entropy).

The best-known treatment of time as a dimension is Poincaré and Einstein's special relativity (and extended to general relativity), which treats perceived space and time as components of a four-dimensional manifold, known as spacetime, and in the special, flat case as Minkowski space. Time is different from other spatial dimensions as time operates in all spatial dimensions. Time operates in the first, second and third as well as theoretical spatial dimensions such as a fourth spatial dimension. Time is not however present in a single point of absolute infinite singularity as defined as a geometric point, as an infinitely small point can have no change and therefore no time. Just as when an object moves through positions in space, it also moves through positions in time. In this sense the force moving any object to change is time.[8][9][10]

Additional dimensions

[edit]In physics, three dimensions of space and one of time is the accepted norm. However, there are theories that attempt to unify the four fundamental forces by introducing extra dimensions/hyperspace. Most notably, superstring theory requires 10 spacetime dimensions, and originates from a more fundamental 11-dimensional theory tentatively called M-theory which subsumes five previously distinct superstring theories. Supergravity theory also promotes 11D spacetime = 7D hyperspace + 4 common dimensions. To date, no direct experimental or observational evidence is available to support the existence of these extra dimensions. If hyperspace exists, it must be hidden from us by some physical mechanism. One well-studied possibility is that the extra dimensions may be "curled up" (compactified) at such tiny scales as to be effectively invisible to current experiments.

In 1921, Kaluza–Klein theory presented 5D including an extra dimension of space. At the level of quantum field theory, Kaluza–Klein theory unifies gravity with gauge interactions, based on the realization that gravity propagating in small, compact extra dimensions is equivalent to gauge interactions at long distances. In particular when the geometry of the extra dimensions is trivial, it reproduces electromagnetism. However, at sufficiently high energies or short distances, this setup still suffers from the same pathologies that famously obstruct direct attempts to describe quantum gravity. Therefore, these models still require a UV completion, of the kind that string theory is intended to provide. In particular, superstring theory requires six compact dimensions (6D hyperspace) forming a Calabi–Yau manifold. Thus Kaluza-Klein theory may be considered either as an incomplete description on its own, or as a subset of string theory model building.

In addition to small and curled up extra dimensions, there may be extra dimensions that instead are not apparent because the matter associated with our visible universe is localized on a (3 + 1)-dimensional subspace. Thus, the extra dimensions need not be small and compact but may be large extra dimensions. D-branes are dynamical extended objects of various dimensionalities predicted by string theory that could play this role. They have the property that open string excitations, which are associated with gauge interactions, are confined to the brane by their endpoints, whereas the closed strings that mediate the gravitational interaction are free to propagate into the whole spacetime, or "the bulk". This could be related to why gravity is exponentially weaker than the other forces, as it effectively dilutes itself as it propagates into a higher-dimensional volume.

Some aspects of brane physics have been applied to cosmology. For example, brane gas cosmology[11][12] attempts to explain why there are three dimensions of space using topological and thermodynamic considerations. According to this idea it would be since three is the largest number of spatial dimensions in which strings can generically intersect. If initially there are many windings of strings around compact dimensions, space could only expand to macroscopic sizes once these windings are eliminated, which requires oppositely wound strings to find each other and annihilate. But strings can only find each other to annihilate at a meaningful rate in three dimensions, so it follows that only three dimensions of space are allowed to grow large given this kind of initial configuration. Extra dimensions are said to be universal if all fields are equally free to propagate within them.

In computer graphics and spatial data

[edit]Several types of digital systems are based on the storage, analysis, and visualization of geometric shapes, including illustration software, computer-aided design, and geographic information systems. Different vector systems use a wide variety of data structures to represent shapes, but almost all are fundamentally based on a set of geometric primitives corresponding to the spatial dimensions:[13]

- Point (0-dimensional), a single coordinate in a Cartesian coordinate system.

- Line or Polyline (1-dimensional) usually represented as an ordered list of points sampled from a continuous line, whereupon the software is expected to interpolate the intervening shape of the line as straight- or curved-line segments.

- Polygon (2-dimensional) usually represented as a line that closes at its endpoints, representing the boundary of a two-dimensional region. The software is expected to use this boundary to partition 2-dimensional space into an interior and exterior.

- Surface (3-dimensional) represented using a variety of strategies, such as a polyhedron consisting of connected polygon faces. The software is expected to use this surface to partition 3-dimensional space into an interior and exterior.

Frequently in these systems, especially GIS and cartography, a representation of a real-world phenomenon may have a different (usually lower) dimension than the phenomenon being represented. For example, a city (a two-dimensional region) may be represented as a point, or a road (a three-dimensional volume of material) may be represented as a line. This dimensional generalization correlates with tendencies in spatial cognition. For example, asking the distance between two cities presumes a conceptual model of the cities as points, while giving directions involving travel "up," "down," or "along" a road imply a one-dimensional conceptual model. This is frequently done for purposes of data efficiency, visual simplicity, or cognitive efficiency, and is acceptable if the distinction between the representation and the represented is understood but can cause confusion if information users assume that the digital shape is a perfect representation of reality (i.e., believing that roads really are lines).

More dimensions

[edit]List of topics by dimension

[edit]- 0 dimension

- 1 dimension

- 2 dimensions

- 3 dimensions

- 4 dimensions

- 5 dimensions

- 8 dimensions

- 10 dimensions

- 11 dimensions

- 12 dimensions

- 16 dimensions

- 26 dimensions

- 32 dimensions

- Higher dimensions

- Infinite

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dave Kornreich (January 1999). "Curious About Astronomy". astro.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-01-11. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ "MathWorld: Dimension". wolfram.com. 2014-02-27. Archived from the original on 2014-03-25. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ^ Yau, Shing-Tung; Nadis, Steve (2010). "4. Too Good to be True". The Shape of Inner Space: String Theory and the Geometry of the Universe's Hidden Dimensions. Basic Books. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-465-02266-3.

- ^ Fantechi, Barbara (2001), "Stacks for everybody" (PDF), European Congress of Mathematics Volume I, Progr. Math., vol. 201, Birkhäuser, pp. 349–359, archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-01-17

- ^ Hurewicz, Witold; Wallman, Henry (2015). Dimension Theory (PMS-4), Volume 4. Princeton University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4008-7566-5. Extract of page 24

- ^ Fractal Dimension Archived 2006-10-27 at the Wayback Machine, Boston University Department of Mathematics and Statistics

- ^ Lafleur, Laurence J. (1940). "Time as a Fourth Dimension". The Journal of Philosophy. 37 (7): 169–178. doi:10.2307/2017930. ISSN 0022-362X. JSTOR 2017930.

- ^ Rylov, Yuri A. (2007). "Non-Euclidean method of the generalized geometry construction and its application to space-time geometry". arXiv:math/0702552.

- ^ Lane, Paul M.; Lindquist, Jay D. (May 22, 2015). "Definitions for The Fourth Dimension: A Proposed Time Classification System1". In Bahn, Kenneth D. (ed.). Proceedings of the 1988 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science. Springer International Publishing. pp. 38–46. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-17046-6_8. ISBN 978-3-319-17045-9 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Wilson, Edwin B.; Lewis, Gilbert N. (1912). "The Space-Time Manifold of Relativity. The Non-Euclidean Geometry of Mechanics and Electromagnetics". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 48 (11): 389–507. doi:10.2307/20022840. JSTOR 20022840.

- ^ Brandenberger, R.; Vafa, C. (1989). "Superstrings in the early universe". Nuclear Physics B. 316 (2): 391–410. Bibcode:1989NuPhB.316..391B. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(89)90037-0.

- ^ Scott Watson, Brane Gas Cosmology. Archived 2014-10-27 at the Wayback Machine (pdf).

- ^ Vector Data Models, Essentials of Geographic Information Systems, Saylor Academy, 2012

Further reading

[edit]- Murty, Katta G. (2014). "1. Systems of Simultaneous Linear Equations" (PDF). Computational and Algorithmic Linear Algebra and n-Dimensional Geometry. World Scientific Publishing. doi:10.1142/8261. ISBN 978-981-4366-62-5.

- Abbott, Edwin A. (1884). Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. London: Seely & Co.

- —. Flatland: ... Project Gutenberg.

- —; Stewart, Ian (2008). The Annotated Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-2183-2.

- Banchoff, Thomas F. (1996). Beyond the Third Dimension: Geometry, Computer Graphics, and Higher Dimensions. Scientific American Library. ISBN 978-0-7167-6015-3.

- Pickover, Clifford A. (2001). Surfing through Hyperspace: Understanding Higher Universes in Six Easy Lessons. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992381-6.

- Rucker, Rudy (2014) [1984]. The Fourth Dimension: Toward a Geometry of Higher Reality. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-77978-2. Google preview

- Kaku, Michio (1994). Hyperspace, a Scientific Odyssey Through the 10th Dimension. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286189-4.

- Krauss, Lawrence M. (2005). Hiding in the Mirror. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-03395-9.

External links

[edit]- Copeland, Ed (2009). "Extra Dimensions". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

Dimension

View on GrokipediaIn Mathematics

Dimensions of Vector Spaces

In linear algebra, the dimension of a vector space over a field is defined as the cardinality of any basis for .[10] A basis is a linearly independent set that spans , meaning every vector in can be uniquely expressed as a finite linear combination of basis elements with coefficients in .[10] For finite-dimensional spaces, this cardinality is a non-negative integer, with the zero vector space having dimension 0.[11] In the infinite-dimensional case, the dimension is an infinite cardinal number, and a basis is known as a Hamel basis, which exists for every vector space but is generally non-constructive, relying on the axiom of choice via Zorn's lemma.[12] A key property is the dimension theorem, also called Grassmann's relation, which states that for subspaces and of a finite-dimensional vector space , the dimension satisfies where is the sum of the subspaces.[13] This formula quantifies how subspaces combine and overlap, providing a tool to compute dimensions without explicitly finding bases.[13] For instance, the standard Euclidean space over has dimension , with the standard basis where has a 1 in the -th position and 0 elsewhere.[10] The space of all polynomials over a field , denoted , is an example of a countably infinite-dimensional vector space, with basis .[14] Any polynomial is a finite linear combination of these basis elements.[14] The dimension is an invariant under linear isomorphisms: if two vector spaces over the same field are isomorphic, they have the same dimension.[15] This follows from the fact that an isomorphism maps bases to bases bijectively, preserving linear independence and spanning properties.[15] Thus, all finite-dimensional vector spaces of dimension over are isomorphic to .[15]Dimensions in Topology

In topology, dimension is defined as a topological invariant that quantifies the "local complexity" or "size" of a space using covering and separation properties, without relying on linear structures like bases in vector spaces.[16] This approach distinguishes it from algebraic or metric notions, focusing instead on open covers and boundaries to assign non-negative integer values to spaces, capturing their intuitive dimensionality in a homeomorphism-invariant manner. The Lebesgue covering dimension, also known as the topological covering dimension, provides one fundamental measure. For a topological space , it is the smallest non-negative integer (or if no such exists) such that every finite open cover of admits an open refinement where no point lies in more than sets; the order of a cover is defined as the largest integer such that some point belongs to at least sets.[17] This definition ensures that spaces of dimension at most can be "separated" by covers mimicking the behavior of Euclidean -space. Another key notion is the inductive dimension, which comes in small and large variants. The small inductive dimension is defined recursively: if is empty, and otherwise if every point of has arbitrarily small neighborhoods whose boundaries have inductive dimension at most ; the large inductive dimension uses a similar recursion but requires that every open cover has a refinement where the boundaries of the sets have dimension at most . For separable metric spaces, the Lebesgue covering dimension coincides with both inductive dimensions.[18] Examples illustrate these concepts clearly. The Euclidean space has covering dimension , as its open covers can be refined to avoid excessive overlaps in a way that matches the -dimensional structure, but not lower.[16] In contrast, the Cantor set, a compact totally disconnected subset of , has covering dimension 0, since it admits bases of clopen sets, allowing refinements where sets are disjoint.[19] These dimensions exhibit desirable properties, including invariance under homeomorphisms: if and are homeomorphic, then for any of these notions. Additionally, they satisfy monotonicity under continuous maps: for a continuous function , the dimension of the image is at most that of .[18] The development of these ideas traces back to early 20th-century efforts to axiomatize dimension rigorously. Henri Lebesgue introduced the covering dimension in 1911 as part of his work on representing sets via analytic functions and covers.[20] Independently, in the 1920s, Karl Menger and Pavel Urysohn defined the small inductive dimension around 1921–1922, while Urysohn and Stefan Mazurkiewicz later formalized the large inductive dimension in 1926–1927, resolving key questions about equivalence and applicability to metric spaces.[21]Dimensions of Manifolds

In differential geometry and topology, the dimension of a manifold is defined locally through its structure as a space that resembles Euclidean space in sufficiently small neighborhoods. Specifically, an n-dimensional topological manifold is a Hausdorff, second-countable topological space M that is locally homeomorphic to the n-dimensional Euclidean space , meaning every point in M has a neighborhood homeomorphic to an open subset of .[22] This local Euclidean property ensures that the dimension n is well-defined and unique for nonempty manifolds, as it is invariant under homeomorphisms and determined by the topology near each point.[23] To formalize this structure, a manifold is equipped with an atlas, which is a collection of charts covering M, where each is an open subset of M and is a homeomorphism onto an open set in . The charts must be compatible: on overlaps , the transition maps are homeomorphisms, ensuring a consistent notion of dimension n across the entire space.[24] For smooth manifolds, these transition maps are required to be diffeomorphisms (smooth with smooth inverses), which imposes a differentiable structure while preserving the local dimension.[25] The dimension n also manifests in the tangent spaces of smooth manifolds. At each point p in an n-dimensional smooth manifold M, the tangent space —which serves as the best linear approximation to M near p—is an n-dimensional real vector space isomorphic to .[26] This equality of dimensions underscores the manifold's local flatness, with the tangent space providing a vector space model for infinitesimal directions at p. Classic examples illustrate these concepts. The n-sphere is an n-dimensional manifold, as it can be covered by charts excluding one coordinate axis, with transition maps yielding the required homeomorphisms to open sets in .[27] Similarly, the 2-dimensional torus is a compact surface of dimension 2, locally resembling via angular coordinates on each circle factor. In the context of complex manifolds, which carry a compatible complex structure, a manifold of complex dimension m is equivalently a real manifold of dimension 2m, since the local model is .[28] This doubling arises from treating complex coordinates as pairs of real ones, with holomorphic transition maps ensuring the structure. A key global result relating manifold dimension to Euclidean embeddings is the Whitney embedding theorem, which asserts that any smooth n-dimensional manifold (Hausdorff and second-countable) admits a smooth embedding into , realizing the manifold as a submanifold of Euclidean space without self-intersections.[29] This theorem, originally proved by Hassler Whitney, highlights how the local dimension constrains the minimal embedding space required.[30]Dimensions of Algebraic Varieties

In algebraic geometry, the dimension of an affine variety over a field is defined as the Krull dimension of its coordinate ring , where is the ideal of .[31] This Krull dimension equals the transcendence degree of the function field over . Geometrically, it is the length of the longest chain of irreducible closed subvarieties , where is the dimension.[32] For example, the affine space has dimension , as its coordinate ring is a polynomial ring in variables, which has Krull dimension .[31] A hypersurface in , defined by a single irreducible polynomial, has dimension , since its coordinate ring is a hypersurface ring with Krull dimension .[33] Projective varieties are defined as closed subvarieties of projective space , corresponding to homogeneous radical ideals in the homogeneous coordinate ring .[34] The dimension of a projective variety is the Krull dimension of the homogeneous coordinate ring of minus one, or equivalently, the dimension of the affine cone over minus one. The Noether normalization lemma states that for an affine variety of dimension over an infinite field , there exists a finite surjective morphism , making birationally equivalent to affine -space in the sense of integral extensions of rings.[33] This provides a geometric interpretation of the dimension as the minimal number of coordinates needed for such a finite projection. For projective varieties, the dimension relates to the Hilbert polynomial of the homogeneous coordinate ring , which is a polynomial such that equals the dimension of the degree- part of for large .[35] The degree of this Hilbert polynomial equals the dimension of .[36] For instance, the projective space has Hilbert polynomial , of degree .[37]Krull Dimension

In commutative algebra, the Krull dimension of a commutative ring , named after the mathematician Wolfgang Krull, is defined as the supremum of the lengths of all chains of strictly ascending prime ideals in , where the length of such a chain is .[6][38] This measure captures the "size" of the ring in terms of its prime ideal structure, generalizing the classical notion of height (the length of the longest chain descending to a given prime ideal) from integral domains to arbitrary commutative rings.[6] Krull introduced this concept in 1928 to extend results like the principal ideal theorem to Noetherian rings, providing an abstract algebraic analogue to geometric dimension.[38] For example, the polynomial ring over a field has Krull dimension , corresponding to chains of primes generated by subsets of the variables.[6] In contrast, Dedekind domains, such as the ring of integers of a number field, have Krull dimension 1, as their prime ideals are either zero or maximal.[6] Key properties include the fact that the Krull dimension of a quotient ring is at most that of , and more precisely, .[6] Krull's going-up theorem states that for an integral extension of rings , any chain of primes in can be lifted to a chain of the same length in .[39] For integral domains, the dimension satisfies .[6] The notion extends to modules: the Krull dimension of an -module is defined as , where is the support of .[6] This allows dimension theory to apply beyond rings, such as in the study of projective modules or coherent sheaves.Hausdorff Dimension

The Hausdorff dimension provides a way to assign a non-integer "size" to subsets of metric spaces, particularly those that are irregular or fractal-like, extending beyond classical integer dimensions. It is defined for a set in a metric space as , where is the -dimensional Hausdorff measure given by , with denoting the diameter of the set .[40] This measure captures how efficiently can be covered by sets of small diameter, with the infimum over all such covers approaching zero as the scale decreases.[40] The Hausdorff dimension relates closely to the box-counting dimension, defined as , where is the minimal number of sets of diameter needed to cover ; for many self-similar fractals, these two dimensions coincide, providing a practical computational alternative since box-counting is often easier to estimate.[41] For instance, the Sierpinski triangle, constructed by iteratively removing central triangles from an equilateral triangle, has Hausdorff dimension , reflecting its self-similar structure with three copies scaled by .[40] Similarly, the path of a two-dimensional Brownian motion, a continuous but highly irregular random curve, has Hausdorff dimension 2 almost surely, indicating it is space-filling in a measure-theoretic sense despite having zero area.[42] Key properties of the Hausdorff dimension include monotonicity—if , then —and invariance under bi-Lipschitz maps, meaning for any bi-Lipschitz function , which preserves distances up to bounded distortion.[40][43] These ensure the dimension is a robust geometric invariant suitable for abstract sets. In applications to irregular sets, such as fractals without smooth structure, the Hausdorff dimension quantifies complexity; for self-similar fractals satisfying the open set condition, Moran's equation gives , where are the contraction ratios of the similarity maps, solving for the dimension .[44][45]Dimensions of Hilbert Spaces

In Hilbert spaces, the concept of dimension extends the algebraic notion from finite-dimensional vector spaces to infinite-dimensional settings, where it is defined via the cardinality of an orthonormal basis rather than a Hamel basis, due to the completeness and inner product structure.[46] An orthonormal basis in a Hilbert space is a maximal orthonormal set such that every element can be expressed as , with the series converging in the norm topology.[47] The dimension of , denoted , is the cardinality of this index set , which can be finite, countably infinite, or uncountable.[46] A Hilbert space is separable if it admits a countable dense subset, and in this case, it possesses a countable orthonormal basis, making .[47] For example, the space of square-integrable functions on the interval is separable and has a countable orthonormal basis given by the Fourier series exponentials , confirming its countably infinite dimension.[48] Similarly, in quantum mechanics, the state space of a particle in a potential well is modeled by an infinite-dimensional separable Hilbert space like , where observables are self-adjoint operators and states are unit vectors in this countable-dimensional framework.[49] The Riesz representation theorem underscores the preservation of dimension in Hilbert spaces by establishing that the continuous dual space is isometrically isomorphic to itself via the inner product, for unique , thus ensuring .[50] Complementing this, Parseval's identity provides a key relation for orthonormal bases: for and basis , which equates the squared norm of to the sum of the squared absolute values of its Fourier coefficients, highlighting the basis's completeness and the space's structure.[51]In Physics

Spatial Dimensions

In classical physics, the three spatial dimensions describe the extents of length, width, and height through which physical objects and phenomena extend and interact. These dimensions are mathematically formalized as Euclidean 3-space, denoted , which provides the ambient framework for positioning and analyzing the geometry of macroscopic objects.[52] In this space, points are represented by ordered triples of real numbers, enabling the precise description of locations relative to a fixed origin. The standard coordinate system for employs Cartesian coordinates , , and , aligned along three mutually perpendicular axes. This system facilitates vector addition and scalar multiplication, treating as a three-dimensional real vector space. The geometry remains invariant under rotations, governed by the special orthogonal group SO(3), which preserves distances and orientations in physical descriptions of rigid body motion.[53] A key property is the Euclidean distance metric, where the distance between points and is calculated as This formula, derived from the Pythagorean theorem extended to three dimensions, underpins measurements in physics, such as particle separations or structural extents. Additionally, volumes in scale with the cube of linear dimensions; for instance, scaling a cube's side length by a factor multiplies its volume by , reflecting the threefold contribution of each dimension to enclosed space./15:_Multiple_Integration/15.06:_Triple_Integrals_in_Cylindrical_Coordinates) Historically, the conceptualization of three spatial dimensions originated in ancient Greek geometry, as assumed in Euclid's Elements (circa 300 BCE), which systematically developed plane geometry in Books I–VI and extended principles to solid figures in Books XI–XIII, treating space as inherently three-dimensional without explicit proof. The 19th century saw the emergence of non-Euclidean geometries by mathematicians such as Carl Friedrich Gauss, János Bolyai, and Nikolai Lobachevsky, who independently constructed consistent geometries by relaxing Euclid's parallel postulate; these innovations highlighted the contingency of Euclidean assumptions while affirming the empirical fit of three-dimensional Euclidean space to observed physical reality.[54][55] The prevalence of three spatial dimensions in our universe is often explained through anthropic arguments, positing that this dimensionality permits stable planetary orbits under gravity's inverse square law. In dimensions greater than three, the effective force law deviates, leading to spiraling trajectories rather than closed elliptical paths, as analyzed by Paul Ehrenfest in 1917; this stability is crucial for the formation of long-lived solar systems capable of supporting complex life.[56]The Time Dimension

In special relativity, time is conceptualized as the fourth dimension within the framework of Minkowski spacetime, a four-dimensional continuum that unifies the three spatial dimensions with a single temporal dimension to describe the structure of the universe. This approach treats events not merely as points in space at instants of time but as points in a unified spacetime, where the distinction between space and time arises from the geometry of the manifold. The time dimension is distinguished by its role in enforcing causality and the relativistic invariance of physical laws across inertial frames.[57] Hermann Minkowski introduced this formulation in his 1908 lecture "Space and Time," proposing that the laws of physics could be expressed more elegantly by viewing space and time as components of a single entity rather than separate entities, thereby resolving apparent paradoxes in Einstein's 1905 theory of special relativity. In Minkowski spacetime, the geometry is defined by the Minkowski metric, which assigns a negative sign to the time component to reflect the hyperbolic nature of the space: Here, represents the spacetime interval, is the speed of light, is the differential time coordinate, and , , are the spatial differentials; intervals with are spacelike, are timelike, and are null, corresponding to paths of light. This metric ensures that the speed of light remains constant in all inertial frames, with Lorentz transformations acting as the coordinate changes that preserve the metric and mix spatial and temporal coordinates—for instance, transforming to via boosts that couple time and space, such as and , where . These transformations highlight how measurements of time and space are interdependent, leading to effects like time dilation and length contraction.[58][59]/17%3A_Relativistic_Mechanics/17.05%3A_Geometry_of_Space-time) A key feature of the time dimension in this framework is its manifestation through worldlines and light cones, which illustrate the causal structure of spacetime. The worldline of a particle is a one-dimensional curve in four-dimensional Minkowski spacetime tracing its positions over time, always timelike for massive particles since they cannot exceed the speed of light. Light cones, centered at any event, demarcate the boundaries of causality: the future light cone contains all events reachable from the origin event by signals traveling at or below , the past light cone includes events that can influence the origin, and the exterior region is spacelike, inaccessible by light signals. These cones separate past and future, preventing causal paradoxes in relativistic physics./17%3A_Relativistic_Mechanics/17.05%3A_Geometry_of_Space-time) The time dimension is further distinguished by the arrow of time, which imparts a preferred direction to temporal evolution, unlike the reversible spatial dimensions. This asymmetry arises from the second law of thermodynamics, where the entropy of an isolated system tends to increase over time, as formulated by Ludwig Boltzmann in his statistical mechanics framework; the probability of entropy-decreasing processes is overwhelmingly low due to the vast number of microscopic configurations corresponding to high-entropy macrostates. In Minkowski spacetime, this thermodynamic arrow aligns with the forward progression along timelike worldlines, reinforcing the distinction between past and future light cones.Extra Dimensions

In theoretical physics, extra dimensions refer to spatial dimensions beyond the three observed in everyday experience and the one time dimension, proposed in various models to unify fundamental forces or address discrepancies in the Standard Model and general relativity. These models typically posit a higher-dimensional spacetime where the additional dimensions are compactified—curled up into tiny, unobservable scales—to reproduce the familiar four-dimensional physics at low energies. Compactification ensures that the effects of extra dimensions manifest only at high energies or through subtle modifications to known interactions.[60] One of the earliest proposals for extra dimensions is the Kaluza-Klein theory, introduced in the 1920s, which extends general relativity to five-dimensional spacetime. In this framework, the fifth dimension is compactified into a small circle, leading to the emergence of electromagnetism as a geometric effect from the five-dimensional metric; the four-dimensional theory then recovers both gravity and Maxwell's equations from the higher-dimensional vacuum Einstein equations. This unification inspired later developments but faced challenges with quantum effects and the need for further compactifications.[61] String theory, a leading candidate for a quantum theory of gravity, requires 10 dimensions for superstring theories or 11 dimensions in M-theory to ensure mathematical consistency and anomaly cancellation. The extra six or seven dimensions are compactified on Calabi-Yau manifolds, complex geometric structures that preserve supersymmetry and allow for a rich landscape of possible vacua, influencing particle masses and couplings in the effective four-dimensional theory. These manifolds provide the necessary topology for the strings to vibrate in modes that correspond to known particles and forces.[62] Braneworld models offer another approach, where our four-dimensional universe is a lower-dimensional "brane" embedded in a higher-dimensional "bulk" spacetime, with Standard Model particles confined to the brane while gravity propagates into the extra dimensions. In the Randall-Sundrum model, for instance, a warped geometry in five dimensions localizes gravity near our brane, explaining its weakness relative to other forces without requiring large flat extra dimensions. Dimension reduction occurs through moduli spaces, parameter spaces governing the size and shape of compact dimensions, which stabilize to yield effective four-dimensional physics.[63][64] Experimental searches for extra dimensions focus on high-energy colliders and gravitational observations. At the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), signatures include missing transverse energy from gravitons escaping into extra dimensions or microscopic black holes in models with large extra dimensions, though no evidence has been found, setting bounds on the compactification scale above several TeV. Gravitational wave detectors like LIGO provide complementary constraints; deviations in waveform propagation or frequency-dependent speed of gravity from events like GW170817 limit extra dimension sizes to below millimeter scales for certain models.[65][66][67] A key challenge in extra dimension models is the hierarchy problem—the vast disparity between the electroweak scale (~100 GeV) and the Planck scale (~10^19 GeV)—and why extra dimensions remain hidden. In compactified scenarios, the extra dimensions have radii on the order of the Planck length (~10^-35 m), making them undetectable at current energies; larger extra dimensions could dilute gravity's strength across the volume, addressing the hierarchy, but they are constrained by short-range gravity experiments to sizes smaller than approximately 30 micrometers for two extra dimensions (as of 2024).[68] These models thus require fine-tuning of compactification parameters to evade observations while solving theoretical puzzles.[60]In Computing and Data

Dimensions in Computer Graphics

In computer graphics, 2D rendering operates on a raster grid of pixels, where each pixel represents a discrete position in a two-dimensional coordinate system, enabling straightforward manipulation of flat images and sprites without depth considerations.[69] In contrast, 3D graphics define scenes using vertices with three-dimensional coordinates (x, y, z), which capture spatial positions in a virtual environment modeled after the three spatial dimensions.[70] These vertices form polygons that approximate surfaces, requiring projection matrices to map the 3D geometry onto the 2D pixel grid of display screens, simulating depth through perspective or orthographic transformations.[71] The core of 3D rendering lies in the transformation pipeline, particularly the model-view-projection (MVP) sequence, which converts vertex coordinates from local object space to world coordinates via the model matrix, then to camera-relative view space using the view matrix, and finally to normalized clip space through the projection matrix.[72] This pipeline culminates in perspective division, reducing the projected 3D coordinates to 2D screen space for rasterization, ensuring efficient handling of visibility and occlusion in complex scenes.[73] Key examples include ray tracing, a seminal technique introduced by Whitted in 1980 that traces rays from the camera through each pixel into 3D space to compute intersections, reflections, and shadows for photorealistic effects.[74] Texture mapping complements this by projecting 2D images onto 3D surfaces using parametric UV coordinates, maintaining dimensional consistency between the texture's 2D domain and the surface's 3D geometry, as comprehensively surveyed by Heckbert in 1986.[75] Higher-dimensional visualization extends these principles by projecting four-dimensional (4D) structures, such as tesseracts—four-dimensional hypercubes with 16 vertices (in general, an n-dimensional hypercube has 2^n vertices)—onto 3D or 2D spaces through nested perspective transformations that preserve rotational dynamics.[76] For instance, a 4D-to-3D projection followed by a 3D-to-2D projection allows interactive animation of tesseract rotations, revealing inner structures otherwise hidden in lower dimensions. Volume rendering addresses 3D volumetric data, such as scalar fields from medical imaging, by integrating opacity and color along rays through the volume to generate 2D projections, a method pioneered by Levoy in 1988 for direct surface extraction and visualization.[77] APIs like OpenGL facilitate these dimensional operations using 4D homogeneous coordinates (x, y, z, w), where the w component enables unified matrix representations for translations, rotations, scaling, and perspective projections, streamlining the graphics pipeline from vertex processing to fragment shading.[78] This approach supports up to 4D transformations natively, allowing efficient rendering of projected higher-dimensional data while clipping invalid coordinates outside the view frustum.[70]Dimensions in Data Analysis

In data analysis, the feature space dimension refers to the number of variables or features that define each data point in a dataset, typically represented as points in an n-dimensional Euclidean space . For instance, image datasets like MNIST treat each 28×28 pixel grayscale image as a 784-dimensional vector, where each dimension corresponds to a pixel intensity value. This high dimensionality allows for capturing complex patterns but often complicates analysis due to computational and statistical challenges.[79] The curse of dimensionality describes the exponential growth in volume and sparsity that occurs in high-dimensional spaces, leading to phenomena such as distance concentration—where most points become equidistant—and the need for exponentially more samples to maintain density. Coined by Richard Bellman in 1957 during his work on dynamic programming, this issue hampers machine learning tasks like classification and clustering by increasing overfitting risks and computational costs. In high dimensions, data points tend to lie near the boundary of the space, resulting in sparse sampling that undermines traditional distance-based metrics.[80] To mitigate these effects, dimensionality reduction techniques project high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional subspaces while preserving essential structure. Principal component analysis (PCA), introduced by Karl Pearson in 1901, achieves this by identifying orthogonal directions (principal components) of maximum variance through the eigenvalues of the data's covariance matrix; the top k eigenvectors form the projection basis, reducing from n to k dimensions. For example, applying PCA to the 784-dimensional MNIST dataset can yield a 2D visualization that separates digit classes based on dominant variance in pixel patterns, such as stroke thickness and orientation. Complementing PCA's linear approach, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), developed by Laurens van der Maaten and Geoffrey Hinton in 2008, uses non-linear mappings to preserve local neighborhoods, effectively embedding MNIST digits into 2D clusters that reveal manifold-like separations not captured by linear methods.[81][82] Estimating the intrinsic dimension—the minimal dimensionality needed to represent the data's variability—provides insight into the effective complexity beyond the ambient feature space. One key metric is the correlation dimension, calculated via the Grassberger-Procaccia algorithm from 1983, which assesses how the number of pairs of points within distance r scales as , where is the dimension estimated from the slope of versus in the linear regime. This method helps quantify sparsity in high-dimensional datasets, guiding reduction techniques; for MNIST, for example, estimates using the correlation dimension yield ~10-14 for individual digit classes, while for the full dataset, values are higher (often 200-500), still far below 784, reflecting the manifold structure of handwritten digit variations.[83][84][85]Dimensionality Across Disciplines

Dimensions in Probability and Statistics

In probability and statistics, random variables often inhabit multidimensional spaces, such as , where the joint probability density function (PDF) specifies the likelihood of the vector taking a particular value . This joint PDF integrates to 1 over the entire space and allows computation of probabilities for regions in n dimensions.[86] Marginalization reduces dimensionality by integrating the joint PDF over subsets of variables; for instance, the marginal PDF of is , yielding a one-dimensional distribution that summarizes the behavior of independently of the others.[87] Stochastic processes extend this to time-dependent random variables, with the dimension of the state space defining the process's complexity. The state space is the set of possible values the process can take at each time, and its dimension indicates the degrees of freedom; for example, standard Brownian motion, or the Wiener process, operates in a one-dimensional state space , where paths are continuous but nowhere differentiable, modeling random walks with independent Gaussian increments.[88] Higher-dimensional variants, like multidimensional Brownian motion in , feature independent components each following a one-dimensional process, enabling modeling of vector-valued evolutions such as particle diffusion in space.[88] A key example is the multivariate normal distribution in dimensions, which generalizes the univariate Gaussian and is parameterized by an -dimensional mean vector and an positive semi-definite covariance matrix . The PDF is given by where the covariance matrix encodes linear dependencies and variances among the components, making it central to linear models and hypothesis testing in multiple variables.[89] In time series analysis, the embedding dimension represents the minimal dimension needed to reconstruct a dynamical system's attractor from a scalar observation via delay coordinates, ensuring topological equivalence to the original phase space under Takens' embedding theorem, which requires where is the dimension of the attractor.[90] The correlation dimension provides a probabilistic measure of an attractor's complexity in chaotic systems, defined as , where is the correlation integral—the expected number of pairs of points within distance under the invariant measure, estimated from time series data. Introduced by Grassberger and Procaccia, this dimension quantifies how points cluster in embedding space and is lower than the embedding dimension for fractal structures, aiding detection of determinism in noisy data.[83] It relates briefly to the Hausdorff dimension for chaotic attractors, approximating the geometric support under uniform measures.[91] High-dimensional sampling poses significant challenges due to the concentration of measure phenomenon, where probability distributions in as concentrate sharply around their means or medians, leading to the "curse of dimensionality" in estimation and inference. Lévy's lemma formalizes this for the unit sphere , stating that for a 1-Lipschitz function , for uniform on the sphere, implying rapid decay of deviations and complicating uniform sampling or integration in high dimensions.[92]Phenomena by Dimensionality

Phenomena associated with zero dimensions (0D) primarily involve idealized point-like entities without spatial extent. In particle physics, elementary particles such as electrons and quarks are modeled as point particles, treated as zero-dimensional objects in the Standard Model to high precision, with no observed internal structure down to scales of m for electrons[93] and m for quarks.[94] Singularities, exemplified by the Dirac delta function, represent mathematical distributions concentrated at a single point, used in physics to model impulsive forces or point sources, such as in electrostatics where the potential diverges at the origin while integrating to a finite value. One-dimensional (1D) phenomena often manifest as linear structures or propagations along a single axis. Line defects, particularly dislocations in crystalline materials, are one-dimensional imperfections where atoms are misaligned along a line, significantly influencing plasticity and strength; for instance, edge dislocations allow shear deformation in metals. Waves on a taut string illustrate 1D wave propagation, where transverse vibrations follow the one-dimensional wave equation, leading to standing waves and harmonics observable in musical instruments. The DNA double helix functions as a one-dimensional polymer chain, with its helical configuration enabling genetic information storage and replication through linear sequencing of nucleotides. Two-dimensional (2D) phenomena are characterized by planar or surface behaviors. Surfaces in geometry and physics, such as minimal surfaces, minimize area for given boundaries, as seen in catenoid shapes formed by soap films under tension, demonstrating Plateau's laws. Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice, exhibits exceptional 2D properties including high electron mobility and Dirac-like fermions, revolutionizing electronics since its isolation. Soap films further highlight 2D fluid dynamics, where surface tension drives film stability and rupture, modeled by 2D Navier-Stokes equations in thin-film approximations. Three-dimensional (3D) phenomena dominate everyday matter and celestial mechanics. Bulk matter, comprising solids, liquids, and gases, occupies volume in three spatial dimensions, with properties like density and elasticity arising from 3D atomic arrangements, as in isotropic crystals. Planetary orbits occur in three-dimensional space, governed by Newton's law of universal gravitation, resulting in elliptical paths confined to orbital planes within the 3D heliocentric system, as described by Kepler's laws extended to vector form. Higher-dimensional and fractal phenomena transcend integer dimensions, incorporating non-Euclidean complexities. In special relativity, spacetime events are zero-dimensional points embedded in four-dimensional Minkowski space, where worldlines trace particle histories across time and three spatial coordinates. Fractal structures like coastlines exhibit a Hausdorff dimension of approximately 1.2, reflecting self-similar irregularity at multiple scales, as quantified by Mandelbrot's fractal geometry applied to natural boundaries. Turbulence in fluid flows displays an effective fractal dimension around 2.5 for its dissipative structures, capturing the intermittent, scale-invariant nature of eddies in the inertial range. Cross-disciplinary low-dimensional quantum effects bridge physics and materials science. The two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG), confined in semiconductor heterostructures, shows quantized Hall conductance in integer steps under magnetic fields, underpinning the quantum Hall effect discovered in 1980. Such systems reveal dimensionality-dependent behaviors, like enhanced superconductivity in 2D layers compared to 3D bulks.References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Space_and_Time