Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Malta convoys

View on Wikipedia

| Malta convoys | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Mediterranean | |

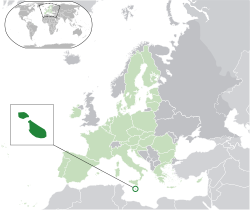

Relief map of the Mediterranean Sea | |

| Operational scope | Supply operations |

| Location | |

| Planned by | Mediterranean Fleet RAF Middle East (RAF Middle East Command from 29 December 1941) Merchant Navy Allies |

| Commanded by | Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, 1 June 1939 – March 1942 Admiral Sir Henry Harwood, 22 April 1942 – February 1943 |

| Objective | Break of the Siege of Malta |

| Date | 27 June 1940 – 31 December 1943 |

| Outcome | Allied victory |

| Casualties | 1,600 civilians on Malta 5,700 service personnel on land, sea and in the air Aircraft: 707 Merchant ships: 31 sunk Royal Navy: 1 battleship 2 aircraft carriers 4 cruisers 1 minelayer 20 destroyers/minesweepers 40 submarines unknown number of smaller vessels |

The Malta convoys were Allied supply convoys of the Second World War. The convoys took place during the Siege of Malta in the Mediterranean Theatre. Malta was a base from which British sea and air forces could attack ships carrying supplies from Europe to Italian Libya. Britain fought the Western Desert Campaign against Axis armies in North Africa to keep the Suez Canal and to control Middle Eastern oil. The strategic value of Malta was so great the British risked many merchant vessels and warships to supply the island and the Axis made determined efforts to neutralise the island as an offensive base.

The civilian population and the garrison required imports of food, medical supplies, fuel and equipment; the military forces on the island needed reinforcements, ammunition and spare parts. British convoys were escorted to Malta by ships of the Mediterranean Fleet, Force H and aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm and Royal Air Force, during the Battle of the Mediterranean (1940–1943). British and Allied ships were attacked by the Italian Regia Aeronautica (Royal Air Force) and Regia Marina (Royal Navy) in 1940 and from 1941, by the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) and Kriegsmarine (German Navy).

In 1942, the British assembled large flotillas of warships to escort Malta convoys, sent fast warships to make solo runs to the island and organised Magic Carpet supply runs by submarine. Hurricane and then Spitfire fighters were flown to Malta from aircraft carriers on Club Runs from Gibraltar towards Malta. In mid-1942, Axis air attacks on the island and on supply convoys neutralised Malta as an offensive base and an Axis invasion, Unternehmen Herkules (Operation Hercules), was set for mid-July 1942 but cancelled.

The siege of Malta eased after the Allied victory at the Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942). The Axis retreat from Egypt and Cyrenaica brought more of the seas around Malta into range of Allied land-based aircraft. In Operation Stoneage, which began after Operation Torch (8–16 November), round the clock air cover was possible and all the merchant ships reached Malta. Mediterranean convoys were resumed to supply the advancing British forces, from which ships for Malta were detached and escorted to and from the island.

Background

[edit]Malta, 1940–1941

[edit]

Malta, a Mediterranean island of 122 sq mi (320 km2) had been a British colony since 1814. By the 1940s, the island had a population of 275,000 but local farmers could feed only one-third of the population, the deficit being made up by imports. Malta was a staging post on the British Suez Canal sea route to India, East Africa, the oilfields of Iraq and Iran, India and the Far East. The island was also close to the Sicilian Channel between Sicily and Tunis.[1] Malta was also a base for air, sea and submarine operations against Axis supply convoys by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Fleet Air Arm (FAA).[2]

Central Mediterranean, 1942

[edit]Military operations from Malta and using the island as a staging post, led to Axis air campaigns against the island in 1941 and 1942. By late July, the 80 fighters on the island averaged wastage of 17 per week and the remaining aviation fuel was only sufficient for the fighters, making it impractical to send more bombers and torpedo-bombers for offensive operations.[3] Resources available to sustain Malta were reduced when Japan declared war in December 1941, and conducted the Indian Ocean raid in April 1942.[4] Malta was neutralised as an offensive base against Italian convoys by the attacks of the Regia Aeronautica and the Luftwaffe in early 1942. Several warships were sunk in Valletta harbour and others were withdrawn to Gibraltar and Egypt. Food and medicines for the Maltese population and the British garrison dwindled along with fuel, ammunition and spare parts with the success of Axis attacks on Malta convoys. The Italian Operation C3 and the Axis Unternehmen Herkules (Operation Hercules) invasion plans against Malta were prepared but then cancelled on 16 June 1942.[5][6]

Battle of the Mediterranean

[edit]

The Allies waged the Western Desert Campaign (1940–43) in North Africa, against the Axis forces of Italy aided by Germany, which sent the Deutsches Afrika Korps and substantial Luftwaffe detachments to the Mediterranean in late 1940. Up to the end of the year, 21 ships with 160,000 long tons (160,000 t) of cargo reached Malta without loss and a reserve of seven months' supplies had been accumulated. Three convoy operations to Malta in 1941 lost one merchant ship. From January 1941 to August 1942, 46 ships delivered 320,000 long tons (330,000 t) but 25 ships were sunk and modern, efficient, merchant ships, naval and air forces had been diverted from other routes for long periods; thirty-one supply runs by submarines were also conducted.[7] Reinforcements for Malta, included 19 Club Runs, risky aircraft carrier ferry operations to deliver fighters.[8] From August 1940 to the end of August 1942, 670 Hurricane and Spitfire fighters were flown off aircraft carriers in the western Mediterranean.[9] Many other aircraft used Malta as a staging post for North Africa and the Desert Air Force.[10]

Prelude

[edit]When Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940, the Taranto Naval Squadron did not sail to occupy Malta as suggested by Admiral Carlo Bergamini.[11] With Italian bases in Sicily, British control of Malta was made more difficult from its bases in Gibraltar to the west and Cyprus, Egypt and Palestine to the east, which were much further away. Two weeks later, the Second Armistice at Compiègne ended British access to Mediterranean Sea bases in France and passage to Mediterranean colonies. The British attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July 1940 against French naval ships, began an informal war between Vichy France and Britain. Axis support for General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War also caused the British to be apprehensive about the security of the British base at Gibraltar. It was soon clear that unlike the Atlantic, where the war was fought by U-boats and surface and air escorts, operations in the Mediterranean would depend on air power and the possession of land bases to operate the aircraft.[12]

Events on land in Greece, Crete, Libya and the rest of the south shore of the Mediterranean would have great influence on the security of sea communications by both sides. An Italian conquest of Egypt could link Abyssinia, Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. The Italian invasion of Egypt in September 1940, was followed by Operation Compass, a British counter-offensive in December, which led to the destruction of the Italian 10th Army and the conquest of Cyrenaica in January 1941. Hitler transferred the Fliegerkorps X to Sicily in Unternehmen Mittelmeer (Operation Mediterranean) to protect the Axis supply routes past Malta, and sent the Afrika Korps to Libya in Unternehmen Sonnenblume (Operation Sunflower) which, with Italian reinforcements, recaptured Cyrenaica.[13] Fliegerkorps X was transferred to Greece in April 1941 and the 23rd U-boat Flotilla was based at Salamis, near Athens, in September.[14]

First year

[edit]July 1940

[edit]

In the Battle of Calabria (Battaglia di Punta Stilo), Regia Marina escorts (two battleships, 14 cruisers and 32 destroyers) of an Italian convoy engaged the battleships HMS Warspite, Malaya, Royal Sovereign and the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle.[15] The British cruisers and destroyers covered two convoys heading from Malta to Alexandria. The first, Malta Fast 1 (MF 1)/Malta East 1 (ME 1), was composed of El Nil, Knight of Malta and Rodi; the second, Malta Slow 1 (MS 1)/ME 1 was composed of Kirkland, Masirah, Novasli, Tweed and Zeeland.[15]

August 1940

[edit]Operation Hurry

[edit]Using an aircraft carrier to ferry land-based aircraft to Malta had been discussed by the Admiralty in July and once Italy had declared war, the reinforcement of Malta could be delayed no longer. The training aircraft carrier HMS Argus was used to despatch twelve Hurricanes to Malta from a position to the south-west of Sardinia. Hurry was the first Club Run to reinforce the air defence of the island, despite the British Chiefs of Staff decision two months earlier that nothing could be done to reinforce Malta.[8] Club Runs continued until it was possible to fly the aircraft direct from Gibraltar.[16]

September 1940

[edit]Operation Hats

[edit]

The Mediterranean Fleet in Alexandria escorted the fast Convoy MF 2 of three freighters carrying 40,000 short tons (36,000 t) of supplies, including reinforcements and ammunition for anti-aircraft guns and met at Malta another convoy from Gibraltar.[17] En route, Italian airbases were raided; the Regia Marina had superior forces at sea but missed the opportunity to exploit their advantage.[18]

October 1940

[edit]Operation MB 6

[edit]Four ships of Convoy MF 3 reached Malta safely from Alexandria and three ships returned to Alexandria as Convoy MF 4.[17] The convoys were part of Operation MB 6 and the escort included four battleships and two aircraft carriers. An Italian attempt against the returning escort by destroyers and torpedo boats ended in the Battle of Cape Passero, a British success.[19]

November 1940

[edit]Operation Judgement

[edit]

The five ship Convoy MW 3 from Alexandria and four ship return Convoy ME 3 arrived safely, coinciding with a troop convoy from Gibraltar and the air attack on the Italian battle fleet at the Battle of Taranto.[17][20]

Operation White

[edit]In Operation White, twelve Hurricanes were flown off Argus to reinforce Malta but the threat of the Italian fleet lurking south of Sardinia prompted a premature fly-off from Argus and its return to Gibraltar. Eight Hurricanes ran out of fuel and ditched at sea, with seven pilots lost.[21] An enquiry found that the Hurricane pilots had been insufficiently trained about the range and endurance of their aircraft.[8]

Operation Collar

[edit]Operation Collar was intended to combine the passage of a battleship, heavy cruiser and light cruiser with mechanical defects from Alexandria to Gibraltar, with a four-ship Convoy MW 4 to Malta and the sailing of ME 4 from Malta comprising Cornwall and the four empty ships from Convoy MW 3, escorted by a cruiser and three destroyers. Attacks on Italian airfields in the Aegean and North Africa were to be made at the same time. Three ships at Gibraltar, two bound for Malta and one for Alexandria were to be escorted by the cruisers HMS Manchester and HMS Southampton. Operation MB 9 from Alexandria began on 23 November, when Convoy MW 4 with four ships sailed with eight destroyer escorts, covered by Force E of three cruisers. Force D comprising a battleship and two cruisers sailed on 24 November and next day, two more battleships, an aircraft carrier, two cruisers and four destroyers of Force C departed Alexandria. MW 4 reached Malta without incident; ME 4 had sailed on 26 November, two destroyers returned to Malta; the cruiser and one destroyer saw the freighters into Alexandria and Port Said on 30 November.[22]

Force F from Gibraltar was to pass 1,400 soldiers and RAF personnel from Gibraltar to Alexandria in the two cruisers, slip two supply ships into Malta and one to Crete. The other warships destined for the reinforcement of the fleet at Alexandria were to be sent on, the cruisers being accompanied by two destroyers and four corvettes. Force B provided the covering force with the battlecruiser Renown, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, the cruisers Sheffield and Despatch, and nine destroyers. The destroyers and corvettes left Alexandria on the night of 23/24 November to rendezvous with the merchant ships and their destroyer escorts from Britain. The cruisers embarked the troops and RAF personnel, leaving Gibraltar on 25 November. The British were unaware that Italian reconnaissance aircraft had spotted the sorties from both ends of the Mediterranean and set up submarine ambushes. Two Italian battleships, three cruisers and two destroyer flotillas had left harbour, more cruisers, destroyers and torpedo boats following. Force D was attacked on the night of 26/27 November but the attack was so ineffectual that the British did not notice. On 27 November, aircraft from Force F spotted the Italian battle fleet, the force headed for Force D and prepared to defend the merchant ships, in what became a confused and inconclusive engagement. Two Italian submarines attacked three cruisers in the Sicilian Narrows as they waited for the eastbound convoy on the night of 27/28 November to no effect and the two ships for Malta arrived on 29 November, as Force H returned to Gibraltar and the through convoy and naval ships reached Alexandria.[23]

December 1940

[edit]Convoy MW 5A with Lanarkshire and Waiwera carrying supplies and munitions and Convoy MW 5B of Volo, Rodi and Devis, the tanker Pontfield, Hoegh Hood and Ulster Prince from Alexandria with a covering force of a battleship, two cruisers, destroyers and corvettes reached Malta on 20 December and Convoy ME 5 with the empty Breconshire, Memnon, Clan Macaulay and Clan Ferguson were collected by the covering force and returned to Alexandria.[24] Convoy MG 1 with Clan Forbes and Clan Fraser reached Gibraltar from Malta escorted by the battleship and four destroyers.[17][25]

| Convoy/ Operation |

From | Sailed | To | Arrived | No. | Lost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF 1 | Malta | 9 July | Alexandria | 11 July | 3 | 0 | |

| MS 1 | Malta | 10 July | Alexandria | 14 July | 5 | 0 | |

| MF 2/Hats | Alexandria | 29 August | Malta | 2 September | 3 | 0 | |

| MF 3 | Alexandria | 8 October | Malta | 11 October | 4 | 0 | |

| MF 4 | Malta | 11 October | Alexandria | 16 October | 3 | 0 | |

| MW 3 | Alexandria | 4 November | Malta | 10 November | 5 | 0 | |

| ME 3 | Malta | 10 November | Alexandria | 13 November | 4 | 0 | |

| MW 4 | Alexandria | 23 November | Malta | 26 November | 4 | 0 | |

| Collar | Gibraltar | 25 November | Malta | 26 November | 2 | 0 | |

| ME 4 | Malta | 26 November | Alexandria | 29 November | 5 | 0 | |

| MW 5A | Alexandria | 16 December | Malta | 20 December | 2 | 0 | |

| MW 5B | Alexandria | 18 December | Malta | 20 December | 5 | 0 | |

| ME 5A | Malta | 20 December | Alexandria | 23 December | 4 | 0 | |

| MG 1 | Malta | 20 December | Gibraltar | 24 December | 2 | 0 |

Second year

[edit]January 1941

[edit]Operation Excess

[edit]

Operation Excess delivered one ship from Gibraltar to Malta and three to Piraeus. The operation was coordinated with Operation MC 4, consisting of Convoy MW 5+1⁄2 with Breconshire and Clan Macaulay from Alexandria to Malta, ME 6, a return journey of ME 5+1⁄2 with Lanarkshire and Waiwera and ME 6, with Volo, Rodi, Pontfield, Devis, Hoegh Hood, Trocas and RFA Plumleaf. The convoys arrived safely with 10,000 short tons (9,100 t) of supplies. The cruiser Southampton was sunk, the cruiser HMS Gloucester and aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious were badly damaged and a destroyer was damaged beyond repair.[27] Excess was the first occasion that the Luftwaffe participated in an anti-convoy operation; the Italian torpedo boat Vega was sunk during the operations by the cruiser HMS Bonaventure.[28]

February 1941

[edit]Operation MC 8

[edit]Operation MC 8, from19 to 21 February, delivered troops, vehicles and stores to Malta in the cruisers Orion, Ajax and Gloucester and Tribal-class destroyers Nubian and Mohawk, covered by Barham, Valiant, Eagle, Coventry, Decoy, Hotspur, Havock, Hereward, Hero, Hasty, Ilex, Jervis, Janus and Jaguar.[29]

March 1941

[edit]Operation MC 9

[edit]Operation MC 9 covered Convoy MW 6 consisting of Perthshire, Clan Ferguson, City of Manchester and City of Lincoln, which sailed from Alexandria on 19 March, the escorts sailing a day later, covered by the Mediterranean Fleet until the night of 22/23 March. The ships sailed by indirect routes and bad weather enabled the convoy to evade Axis air reconnaissance. The ships arrived at Malta but two were bombed at their berths.[30][31]

April 1941

[edit]Operation Winch and Convoy ME 7

[edit]Hurricanes delivered to Gibraltar on Argus were put on board Ark Royal, which sailed on 2 April, escorted by the battleship Renown, a cruiser and five destroyers. The Hurricanes were flown off on 3 April and all arrived, Force H returning safely to Gibraltar on 4 April. Stores and ammunition were run to Malta in Operations MC 8 and MC 9. On 18 April, the Mediterranean Fleet sailed from Alexandria to Suda Bay in Crete with Breconshire carrying oil and aviation fuel for Malta. Late on 19 April, the Malta Strike Force destroyers sailed with Convoy ME 7 of four empty cargo ships. Breconshire made a run into Malta and the destroyers returned after joining in a shore bombardment by the main fleet. The cruiser Gloucester, which had a long range, joining the force.[32]

Operation Dunlop

[edit]In Operation Dunlop, HMS Ark Royal sailed from Gibraltar on 24 April and flew off 24 Hurricanes at dawn on 27 April. Bristol Blenheims and Beaufighters were flown direct from Gibraltar. Three battleships and an aircraft carrier covered the fast transport HMS Breconshire from Alexandria to Malta. The operation was coordinated with the four-ship Convoy ME 7 from Malta to Alexandria.[33] On 16 April, the value of Malta for offensive operations was shown when four destroyers of 14th Flotilla (the Malta Striking Force), recently based in the island, destroyed an Afrika Korps supply convoy (five ships, for a total of 14,000 GRT and three escorts) in the Battle of the Tarigo Convoy.[34][35][b]

Operation Temple

[edit]During Operation Temple, the freighter Parracombe sailed for Malta from Gibraltar on the night of 28/29 April, disguised as a Spanish merchantman and later as the Vichy steamer Oued-Kroum. She was mined on 2 May, which blew off her bows, and sank with 21 Hurricanes, equipment, ammunition and military freight aboard.[37] The minefield had been laid down on 24 April by the Italian cruisers Duca d'Aosta, Eugenio di Savoia, Muzzio Attendolo and Raimondo Montecuccoli, escorted by the destroyers Italian destroyer Alvise da Mosto and Giovanni da Verrazzano.[38]

May 1941

[edit]Operations Tiger and Splice

[edit]

In Operation Tiger, Convoy WS 8 sailed from Gibraltar to Alexandria, combined with a supply run to Malta by six destroyers of Force H. Five 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h) merchant ships passed Gibraltar on 6 May accompanied by Force H, along with a battleship and two cruisers en route to Alexandria; Clan Campbell, Clan Chattam, Clan Lamont, Empire Song and New Zealand Star. The merchants tried to reach Alexandria with air cover of Fairey Fulmars onboard Ark Royal and the anti aircraft fire of 9 destroyers. Bad weather helped, but the Regia Aeronautica engaged the convoy during the day and at dusk Empire Song was lost after hitting two mines. The destroyers from Force H participated in the convoy operation as far as Malta then returned. Force H bombarded Benghazi and rendezvoused with the convoy 50 nmi (58 mi; 93 km) south of Malta late on 9 May.[39] The minefield had been laid by the same Italian cruiser force whose mines had sunk the freighter Parracombe in early May.[38]

Operation Splice was a Club Run from 19 to 22 May; 48 Hurricanes were flown off Ark Royal and Furious on 21 May, all reaching Malta. Slow Convoy MW 7B with two tankers sailed from Egypt for Malta with 24,000 long tons (24,000 t) of fuel oil, followed by fast Convoy MW 7A with six freighters escorted by five cruisers, three destroyers and two corvettes. Abdiel and Breconshire sailed with the main fleet and all the ships reached Grand Harbour on 9 May, preceded by a minesweeper, which detonated about twelve mines.[40] In May, the Luftwaffe transferred Fliegerkorps X from Sicily to the Balkans, relieving pressure on Malta until December.[41]

June 1941

[edit]Operation Rocket

[edit]A Club Run from 5 to 7 June delivered 35 Hurricanes to Malta, guided by eight Blenheims from Gibraltar.[42]

Operation Tracer

[edit]In June, the new carrier HMS Victorious replaced Furious on Club Runs. Operation Tracer began on 13 June when Ark Royal and Victorious, escorted by Force H, departed Gibraltar. On 14 June, 47 Hurricanes were flown off. The fighters were guided by four Hudsons from Gibraltar and 43 of the Hurricanes reached Malta.[42][43]

Operations Railway I and II

[edit]On 26 June Ark Royal and Furious sailed again with 22 Hurricanes, which were guided to Malta by Blenheims from Gibraltar; all arrived at Malta in bad weather, though one Hurricane crashed on landing. Force H reached port on 28 June, Crated aircraft were assembled aboard Furious as she joined Force H for Operation Railway II; on 30 June, 26 Hurricanes took off from Ark Royal. The second fighter skidded on take-off from Furious and a drop tank came loose and caught fire as the Hurricane went overboard, killing nine men and injuring four more before the fire was extinguished. It was early afternoon before the 35 remaining Hurricanes arrived at Malta, again guided by six Blenheims. During the month 142 aircraft reached Malta, some of which were ferried to Egypt.[42][43][43]

July 1941

[edit]Operation Substance

[edit]Operation Substance sent Convoy GM 1 (six ships transporting 5,000 soldiers, escorted by six destroyers), covered by the battleship Nelson and three cruisers from the Home Fleet and Force H (Ark Royal, Renown, and several cruisers and destroyers). GM 1 reached Gibraltar from Britain on 19 July and sailed for Malta on 21 July, minus troopship RMS Leinster (carrying 1,000 troops and RAF ground crews) which ran aground and had to return to Gibraltar. The Eastern Fleet sortied from Alexandria as a diversion and eight submarines watched Italian ports and patrolled the routes an Italian sortie was expected to use. Force H was to return to Gibraltar upon reaching the Sicilian Narrows, while the close escort of three cruisers, Manxman, and ten destroyers would continue to Malta. During the convoy operation, Breconshire and six other empty ships at Malta were independently to return to Gibraltar in Operation MG 1. On 23 July, south of Sardinia, Italian air attacks began; one cruiser was hit and had to return to Gibraltar, and a destroyer was so badly damaged it was scuttled, but air cover from Ark Royal enabled the convoy to reach the Skerki Channel by late afternoon.[44]

The covering force turned for Gibraltar and the rest of the convoy pressed on, facing more Regia Aeronautica attacks; these forced another damaged destroyer to drop out and return to Gibraltar. Turning north, the convoy evaded Italian aircraft, but on the night of 23/24 July, the 12,000 GRT steamer Sydney Star was torpedoed by an MAS boat and crippled; the Australian destroyer HMAS Nestor assisted her safe arrival to harbour and she was seaworthy again by September. The cruisers sailed ahead to disembark troops and equipment; the convoy and its destroyer escort arrived later on 24 July. A raid on 26 July by Italian midget submarines, MAS boats, and aircraft on the transports in Grand Harbour failed, with the attacking force almost destroyed; 65,000 short tons (59,000 t) of supplies were landed.[44] On 31 July, three cruisers and two destroyers sailed from Gibraltar with the troops and stores left behind in Leinster, reaching Malta 2 August.[45]

September 1941

[edit]Operations Status I and II, Operation Propeller

[edit]

Ark Royal and Furious flew off over 50 Hurricanes to Malta in Operations Status I and Status II, forty-nine arriving; several Blenheims flew direct from Gibraltar at the same time, to build up the Malta striking force to use the munitions delivered in Operation Substance.[46] The merchantman SS Empire Guillemot reached Malta from Gibraltar in Operation Propeller and another ship completed the trip independently.[47]

Operation Halberd

[edit]In Operation Halberd, the eastbound Convoy GM 2 with nine 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h) merchant ships, carrying 81,000 long tons (82,000 t) of supplies and 2,600 troops from Gibraltar, was accompanied by the battleships Nelson, Rodney, Prince of Wales (all detached from the Home Fleet), Ark Royal, five cruisers, and eighteen destroyers. The British staged diversions in the eastern Mediterranean and submarines and aircraft watched Italian naval and air bases. Attacks on the convoy by the Regia Aeronautica began on 27 September, demonstrating more skill and determination than earlier encounters. An Italian torpedo bomber hit Nelson with an aerial torpedo and reduced her speed. Later air attacks were deterred by the anti-aircraft fire of the British destroyer screen. British reconnaissance aircraft reported the Italian Fleet had left harbour and was on an interception course and the British covering force, less Nelson, was sent to engage. Ark Royal launched her torpedo bombers but the Italian turned back, and the aircraft failed to make contact; at about 7:00 p.m., GM 2 reached the Narrows.[48]

The five cruisers and nine of the destroyers continued for Malta as the covering force changed course. The British made course for Sicily, which enabled them to skirt minefields laid by the Italians in the channel between Sicily and the North African coast. During the night the moon was bright and Italian torpedo bombers managed to hit the 10,000 GRT transport Imperial Star with an aerial torpedo. Attempts to tow the ship to Malta failed; her troops were taken off and the ship was scuttled. During the morning of 28 September, the convoy came into range of Malta-based fighters. The rest of the convoy reached Malta at 1:30 p.m. and landed 85,000 short tons (77,000 t) of supplies. Halberd was the last convoy operation of 1941.[49]

October 1941

[edit]Operations Callboy and MG 3

[edit]On 16 October, Force H covered Operation Callboy, another Club Run by Ark Royal, to fly off thirteen Swordfish and Albacore torpedo bombers for Malta, delivered to Gibraltar by Argus.[50] On 12 October, the cruisers HMS Aurora and Penelope had sailed from Scapa Flow for Malta and were joined by the destroyers HMS Lance and Lively of Force H at Gibraltar, reaching the island on 21 October. The squadron was named Force K (reviving a title used in 1939) for operations against the Italian supply route to North Africa. Operation MG 3 was a convoy planned to despatch the Halberd merchant ships from Malta but the ships sailed in succession. Two departed on 16 October but one ship had to turn back with engine trouble. The second ship was covered by the fleet movements of Operation Callboy which reached the flying off point on 17 October and arrived on 19 October, having dodged a torpedo bomber attack. Two cruisers and two destroyers of Force H loaded equipment and ammunition for Malta as soon as they got back to Gibraltar and sailed again on 20 October, arriving at Grand Harbour in Malta the next day. Two ships sailed from Malta in ballast on 21 October and arrived at Gibraltar despite air attacks; one ship with engine trouble left Malta again on 22 October, watched over by Catalina flying boats, but failed to arrive; an Italian radio broadcast claimed the sinking. The fourth ship sailed on 24 October but was attacked by an Italian aircraft and recalled, having been spotted so quickly.[51]

November 1941

[edit]Operation Perpetual

[edit]Force K of two cruisers and two destroyers sailed from Malta on 8 November and sank the merchant ships of an Axis convoy off Cape Spartivento.[52][c] On 10 November, Ark Royal and Argus sailed from Gibraltar and flew off thirty-seven Hurricanes, thirty-four arriving successfully; seven Blenheims flew direct from Gibraltar.[53] On 13 November, Ark Royal was torpedoed and sank the next day, 25 nmi (29 mi; 46 km) from Gibraltar.[54]

Operation Astrologer

[edit]Operation Astrologer (14–15 November 1941), an attempt to supply Malta by two unescorted freighters, Empire Pelican and Empire Defender disguised as neutral Spanish then French ships. Empire Pelican passed Gibraltar on 12 November and sailed close to the Moroccan, Algerian and Tunisian coasts but was spotted by Italian aircraft at early on 14 November south of Galite Islands and sunk by torpedo bombers. Empire Defender was sunk at sunset the next day in the same place; Astrologer was the last attempt to send merchant ships to Malta from the west for six months.[55]

December 1941

[edit]Operations MF 1 and MD 1

[edit]To alleviate a fuel oil shortage on Malta, MV Breconshire was escorted from Malta on 5 December by a cruiser and four destroyers of Force K in Operation MF 1 towards Alexandria; next day, a cruiser and two destroyers left Alexandria. During the evening of 6 December the cruiser and two destroyers returned to Malta and two destroyers carried on with Breconshire, meeting the cruiser and two destroyers from Alexandria at dawn on 7 December. Two destroyers went on to Malta and Breconshire continued to Alexandria accompanied by the cruiser and its two destroyers, reaching Alexandria on 8 December, less the cruiser which was detached to help a sloop damaged by air attack of Tobruk. Breconshire was filled with 5,000 long tons (5,100 t) of boiler oil and every space was filled with supplies. On 15 December, MD 1 began when Breconshire sailed for Malta with three cruiser and eight destroyer escorts. During the night Breconshire was slowed by engine trouble and on 16 December the force headed west in daylight without zig-zagging. After dark a cruiser and two destroyers turned back and made spurious wireless broadcasts to simulate the battle fleet at sea. Destroyers left Malta on 16 December and at 6:00 p.m. Force K comprising two cruisers and two destroyers sailed to meet Breconshire and escort it into Grand Harbour.[56]

During the afternoon, an Italian battleship convoy was spotted and every seaworthy ship at Malta was ordered out to bring in Breconshire. Only one cruiser and two destroyers were operational but they met the oncoming force before dawn on 17 December and the ships made a circle round Breconshire; the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica attacked through the afternoon with bombs and torpedoes. As night was falling, three Italian battleships two cruisers and ten destroyers appeared and Breconshire and two escorts were diverted to the south-west as the rest of the British ships turned towards the Italian fleet. With the escorts between the Italians and Breconshire, the ship was handed over to Force K as it arrived and set a smoke screen. The opposing ships diverged in the dark and Force K turned for Malta with Breconshire; the rest of the ships returned to Alexandria and the Italian freighters reached Libya. Force K and Breconshire spent 18 December under air attack, until Malta Hurricanes arrived in the afternoon and at around 3:00 p.m. the ships arrived in Malta.[57]

| Convoy Operation |

From | Sailed | To | Arrived | No. | Lost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excess | Gibraltar | 6 January | Malta | 10 January | 1 | 0 | |

| MW 5.5 | Alexandria | 7 January | Malta | 10 January | 2 | 0 | |

| ME 5.5 | Malta | 10 January | Alexandria | 13 January | 2 | 0 | |

| ME 6 | Malta | 10 January | Alexandria | 13 January | 7 | 0 | |

| MC 8 | Malta | 20 February | Alexandria | 22 February | 2 | 0 | |

| MW 6 | Alexandria | 19 March | Malta | 23 March | 4 | 0 | |

| MD 2 | Alexandria | 18 April | Malta | 21 April | 1 | 0 | |

| ME 7 | Malta | 19 April | Alexandria | 22 April | 4 | 0 | |

| Temple | Gibraltar | 28 April | Malta | — | 1 | 1 | |

| MD 3 | Malta | 28 April | Alexandria | 20 April | 1 | 0 | |

| Tiger | Gibraltar | 6 May | Alexandria | 12 May | 5 | 1 | |

| MW 7A | Alexandria | 6 May | Malta | 10 May | 4 | 0 | |

| MW 7B | Alexandria | 5 May | Malta | 10 May | 2 | 0 | |

| GM 1 | Gibraltar | 21 July | Malta | 24 July | 6 | 0 | |

| MG 1 | Malta | 23 July | Gibraltar | 26 July | 7 | 0 | |

| Propeller | Gibraltar | 13 September | Malta | 19 September | 1 | 0 | |

| Halberd, GM 2 | Gibraltar | 25 September | Malta | 29 September | 9 | 1 | |

| Halberd, MG 2 | Malta | 26 September | Gibraltar | 29 September | 1 | 0 | |

| Independent | Malta | 27 September | Gibraltar | 20 September | 2 | 0 | Not convoyed |

| Independent | Malta | 16 October | Gibraltar | 19 October | 1 | 0 | Not convoyed |

| Independent | Malta | 22 October | Gibraltar | 27 October | 3 | 1 | Not convoyed |

| Astrologer | Gibraltar | 12 November | Malta | — | 1 | 1 | |

| Astrologer | Gibraltar | 14 November | Malta | — | 1 | 1 | |

| Not named | Malta | 5 December | Alexandria | 8 December | 1 | 0 | |

| Not named | Alexandria | 15 December | Malta | 18 December | 1 | 0 | |

| ME 8 | Malta | 26 December | Alexandria | 29 December | 4 | 0 |

Third year

[edit]January 1942

[edit]Operation MF 2

[edit]

On 5 January, the fast supply ship HMS Glengyle was escorted from Alexandria by 15th Cruiser Squadron (Force B, commanded by Rear Admiral Philip Vian, made up of Dido-class light cruisers Naiad, Dido, and Euryalus and the anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Carlisle) and six destroyers. The cruisers served as a bluff, in the absence of more heavily armed ships capable of challenging a sortie by the Regia Marina.[58][e] Breconshire had sailed from Malta on 6 January escorted by four destroyers of Force C; the two forces met on 7 January and Force C with Glengyle reached Malta on 8 January, Force B with Breconshire arriving at Alexandria the next day.[60]

Operation MF 3

[edit]On 16 January the Convoy MW8A and Convoy MW8B with two ships each, sailed from Alexandria in Operation MF3, accompanied by Carlisle and two destroyer divisions.[61] The 15th Cruiser Squadron sortied on 17 January to join the escort for both convoys. Force K (still short Aurora) departed Malta to rendezvous with the convoy on 18 January. Thermopylae (6,655 tons), in MW8A, developed mechanical faults and was diverted to Benghazi but was severely damaged by bombing en route and had to be scuttled. On 17 January, the destroyer HMS Gurkha was torpedoed by U-133; the Dutch destroyer HNLMS Isaac Sweers towed her clear of blazing oil, allowing most of her crew to be rescued before she sank. The three remaining freighters reached Malta, air attacks on the ships being intercepted by fighters from No. 201 (Naval Co-operation) Group based in Cyrenaica, the convoy and escorts' anti-aircraft guns; once the convoy was in range. Hurricanes from Malta also provided air cover and the ships docked on 19 January.[62] On 26 January, in a similar operation, Breconshire and escorts from Alexandria met two ships which had sailed from Malta on 25 January transporting service families from Malta with escorts from Force K, which escorted Breconshire back to the island on 27 January.[63][64]

February 1942

[edit]Operation MF 5

[edit]

On 12 February, a three ship Convoy MW 9, escorted by Carlisle and eight destroyers, sailed from Alexandria in Operation MF5; several hours later, two cruisers from 15th Cruiser Squadron, escorted by eight destroyers, sortied to protect it. On 14 February, SS Clan Campbell was bombed and forced to seek shelter in Tobruk, Clan Chattan was bombed, caught fire and scuttled in the afternoon; Rowallan Castle was near-missed, disabled and taken under tow but scuttled by Lively after it was realised she could not reach Malta before dark: the escort had been warned that the Italian battleship Duilio had sailed from Taranto to intercept the convoy.[65][66]

March 1942

[edit]Operation Spotter

[edit]| Type | No. | Sunk | Dgd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cruisers | 4 | — | 3 |

| AA ships | 1 | — | — |

| Destroyers | 18 | 3 | 2 |

| Submarines | 5 | 1 | — |

| Freighters | 4 | 1 | — |

| Freighters arriving |

3 | 3 in dock |

— |

On 6 March, Operation Spotter, a Club Run by the aircraft carriers Eagle and Argus flew off the first 15 Spitfire reinforcements for Malta. An earlier attempt had been abandoned but the right external ferry tanks were fitted; seven Blenheims flew direct from Gibraltar. On 10 March, the Spitfires flew their first sorties against a raid by Ju 88s escorted by Bf 109 fighters.[68]

Operation MG 1

[edit]Operation MG 1 began with the four ships of Convoy MW 10 sailing from Alexandria at 7:10 a.m. on 20 March, each with a navy liaison party and Defensively equipped merchant ship (DEMS) gunners, supplemented by service passengers. The convoy was escorted by Force B, the cruisers HMS Cleopatra, Dido, Euryalus, the anti-aircraft cruiser Carlisle and the six ships of the 22nd Destroyer Flotilla. The 5th Destroyer Flotilla sailed from Tobruk on an anti-submarine sweep, before joining the convoy on 21 March. Clan Campbell struggled to keep up because of engine trouble and the convoy timetable was not met. Several British submarines participated near Messina and Taranto to watch for Italian ships. Long Range Desert Group parties were to attack the airfields at Martuba and Tmimi in Cyrenaica as RAF and FAA aircraft bombed them to ground Ju 88 bombers; 201 Group RAF provided air cover and reconnaissance of the convoy route. A club run, Operation Picket was to use Argus and Eagle, with Force H as a decoy, but the Spitfire ferry tanks were found to be defective and the operation was called off.[69]

On 22 March, when MW 10 was through Bomb Alley, news arrived that an Italian squadron had sailed and from 10:35 a.m. – 12:05 p.m. five Italian torpedo bomber attacks were made but with no hits. In the afternoon, German and Italian air attacks began, with bombs and torpedoes, again to no effect. Smoke was seen at 2:10 p.m. and the escorts moved to intercept in rough seas as the convoy was hidden by a smoke screen. Italian cruisers commenced fire then turned to lure the British cruisers towards Littorio; the British did not take the bait. The exchange began the Second Battle of Sirte. Axis aircraft concentrated on the convoy, which manoeuvred so effectively that no ship was hit, but the ships and close escort fired much of their ammunition. During the battle near the convoy, the escorts kept laying smoke screens and the Italians came within 8 nmi (9.2 mi; 15 km) as Force B dodged around in the smoke, attacking at every opportunity.[70]

German air attacks continued and Force B turned for Alexandria, very short of fuel as Force K joined the convoy for the last leg. The convoy had been ordered to disperse, three ships diverting southwards and Clan Campbell making straight for Grand Harbour, the diversions being calculated to bring the ships back together just short of Malta by daylight on 23 March. The detours were a mistake and Pampas was hit by a bomb during the morning but kept going, reaching Malta. Talabot was also frequently attacked but arrived undamaged, except from some small bombs dropped by a Bf 109 fighter-bomber. Clan Campbell was sunk 20 nmi (23 mi; 37 km) from Malta and Breconshire, after being taken in tow by destroyers and tugs several times, reached Marsaxlokk harbour on 25 March. Unloading of the ships was very slow and Luftwaffe attacks on 26 March sank Breconshire in the evening and continued bombing Valletta harbour into the night. Talabot and Pampas were set on fire before unloading, only 4,952 short tons (4,492 t) of the 29,500 short tons (26,800 t) of supplies were landed and several destroyers were seriously damaged.[71]

Operation Picket

[edit]On 22 March, a Club Run by Argus and Eagle covered by Force H sailed from Gibraltar to deliver Spitfires to Malta and to divert attention from MG 1. Two Italian submarines spotted the British ships and one fired torpedoes at Argus with no effect but the operation was cancelled when the long range fuel tanks of the Spitfires were found to be defective. The operation was repeated on 27 March and sixteen Spitfires were flown off for Malta, the ships returning to Gibraltar on 30 March.[72]

April 1942

[edit]Operation Calendar

[edit]As Malta's effectiveness as an offensive base diminished, forty-seven Spitfires were flown off as reinforcements. They were delivered by the American carrier USS Wasp, escorted by the battlecruiser Renown, cruisers HMS Cairo and Charybdis and six British and US destroyers. Most of the aircraft were destroyed on the ground by bombing.[73]

May 1942

[edit]Operations Bowery and LB

[edit]In Operation Bowery, 64 Spitfires were flown off Wasp and Eagle. A second batch of 16 fighters were flown off Eagle in Operation LB.[74]

June 1942

[edit]Operation Style

[edit]On 20 May, SS Empire Conrad departed from Milford Haven, Wales with a cargo of 32 Spitfires Mk Vc (Trop). Also on board were the ground crew who were to assemble them, a total of over 110 men. Empire Conrad was escorted by the 29th ML Flotilla and the corvette HMS Spirea. The convoy was later joined by the minesweepers HMS Hythe and Rye. Empire Conrad arrived at Gibraltar on 27 May. The aircraft were transferred to the aircraft carrier Eagle where they were assembled. On 2 June, Eagle departed from Gibraltar escorted by the cruiser Charybdis and destroyers HMS Antelope, Ithuriel, Partridge, Westcott and Wishart. On 3 June, the aircraft were flown off Eagle, bound for Malta. Twenty-eight arrived safely, with the other four being shot down en route.[75]

Operation Julius (Harpoon and Vigorous)

[edit]

The arrival of more Spitfires from Eagle and the transfer of German aircraft to the Russian Front eased the pressure on Malta but supplies were needed if the island was to avoid surrender. Operation Julius was planned to send convoys simultaneously from both ends of the Mediterranean.[76] The ships for Operation Harpoon sailed from Britain on 5 June and entered the Mediterranean on the night of 11/12 June. Several stations were called on to obtain a battleship, the aircraft carriers Eagle and Argus, three cruisers, and eight destroyers for the escort and covering force to the Narrows, the close escort into Malta comprising the anti-aircraft cruiser Cairo, nine destroyers, four fleet minesweepers, and six minesweeping motor launches. Once the convoy of three British, one Dutch and two U.S. freighters, carrying 43,000 long tons (44,000 t) of supplies, had been swept through the Axis minefields, the minesweepers were to remain at Malta.[77]

The ships from Gibraltar and Alexandria were intended to arrive on consecutive days. Axis naval and air force attacks began on the morning of 12 June; one cruiser was badly damaged and one merchantman sunk. On 15 June, an Italian cruiser force engaged the close escort and as Cairo and as the escort destroyers made smoke, the fleet destroyers attacked the Italian ships. Two of the fleet destroyers were soon disabled the remaining three managed to hit an Italian destroyer and were then joined by the cruiser and the four smaller destroyers. Dive-bombers attacked the convoy soon after and one merchant ship was sunk and another damaged and taken in tow. Near noon, another air attack damaged another merchant ship and the order was given to scuttle the ships in tow, to increase the speed of the remaining two ships, because the Italian squadron was still lurking in the area.[78] The escorts were scattered by the Italian cruiser force, that eventually finished off the tanker Kentucky and the cargo ship Burdwan.[79] The destroyer HMS Bedouin, repeatedly hit by the Italian cruisers and disabled during the battle, was finally sunk by an Italian S-79 torpedo bomber. The Polish Kujawiak was also lost in a minefield a few miles before arrival.[78] The convoy arrived with 15,000 short tons (14,000 t) of supplies under cover of the Malta Spitfires, which defeated several more air attacks.[78]

Operation Vigorous, a convoy of eleven merchant ships from Haifa, Palestine and Port Said, Egypt sailed at the same time as Harpoon. The convoy was attacked by aircraft, torpedo boats and submarines for four days, threatened by an Italian fleet and turned back. The cruiser HMS Hermione and destroyers HMS Hasty, Airedale, Nestor and two merchantmen were sunk.[80]

July 1942

[edit]Operation Pinpoint

[edit]Welshman departed Gibraltar 14 July, carrying powdered milk, cooking oil, fats and flour, soap, and minesweeping stores. She was in company of Force H comprising Eagle; the light anti-aircraft cruisers, Charybdis and Cairo and five destroyers, Antelope, Ithuriel, Vansittart, Westcott and Wrestler. Eagle flew off 31 Spitfires on 15 July; Welshman made an independent run close to the Algerian coast but was shadowed by Axis aircraft and attacked by fighter-bombers, bombers and torpedo bombers until dusk. She reached Malta on 16 July and departed again on 18 July.[81]

Operation Insect

[edit]Eagle sailed from Gibraltar with two destroyers and five destroyers on 20 July, Eagle being missed by a salvo of four torpedoes from the Italian submarine Dandolo and on 21 July another 28 Spitfires were flown off for Malta.[82]

August 1942

[edit]Operation Pedestal

[edit]As supplies on Malta dwindled, particularly of aviation fuel, the largest convoy to date was assembled at Gibraltar for Operation Pedestal. It consisted of 14 merchant ships, including the large oil tanker SS Ohio, carrying a total of 121,000 long tons (123,000 t) of cargo. These were protected by powerful escort and covering forces, totalling forty-four warships, including the aircraft carriers Eagle, Indomitable and Victorious and battleships Nelson and Rodney. A diversionary operation was staged from Alexandria. The convoy was attacked by Axis aircraft, motor torpedo boats and submarines. Three merchant ships reached Malta on 13 August and another on 14 August. Ohio arrived on 15 August, damaged by air attacks, under tow by destroyers HMS Penn and Ledbury. The rest were sunk. Ohio later broke in two in Valletta Harbour but not before much of her cargo had been unloaded. Eagle, the cruisers Cairo and Manchester and the destroyer HMS Foresight were sunk and there was serious damage to other warships; Italian losses were two submarines sunk and two cruisers damaged.[83]

This convoy, especially the arrival of Ohio, was seen as divine intervention by the people of Malta. The feast of the Assumption of Mary is celebrated on 15 August and many Maltese attributed the arrival of Ohio into Grand Harbour as the answer to their prayers.[84] It had been agreed by military commanders at the time that if supplies became any lower, they would surrender the islands (the date, deferred as supplies were received, was referred to as the target date).[85] Pedestal delivered 12,000 long tons (12,000 t) of coal, 32,000 long tons (33,000 t) freight and 11,000 long tons (11,000 t) of oil aboard Ohio. The commodities landed were enough for Malta to last until mid-November.[86] The 568 survivors of the Pedestal convoy were evacuated, 207 men on three destroyers to Gibraltar and the remainder by submarine and aircraft.[87]

Operation Baritone

[edit]

On 16 August, a cruiser and twelve destroyers escorted Furious to the area south of Formentera in the south-west of the Balearic Islands, where she flew off 32 Spitfires; one crashed on take-off and two turned back, the rest reaching Malta that afternoon.[88]

September 1942

[edit]Submarine HMS Talisman left Gibraltar for Valletta on 10 September on a supply run and was lost 17 September, either in a minefield or depth-charged by Italian torpedo boats north-west of Malta.[89]

October 1942

[edit]Magic Carpet rides by submarine reached Malta on 2 October (Rorqual), 3 October (Parthian), and 6 October (Clyde), with petrol and other stores, departing for Beirut on 8 October and carrying survivors from Pedestal.[87]

Operation Train

[edit]A continuous flow of new Spitfires to Malta had become necessary after the Axis air forces resorted to attacks by fighter-bombers; in another Club Run from 28 to 30 October, two cruisers and eight destroyers escorted Furious which flew off 29 Spitfires for Malta, of which two returned with engine trouble. Ten Italian submarines were patrolling but were not able to attack and Axis aircraft were held off until the afternoon of 29 October, when a Ju 88 managed to drop a bomb which landed 600 ft (180 m) behind Furious.[90]

November 1942

[edit]Operations Stone Age and Crupper

[edit]

In early November Operation Crupper was a failed attempt to send an independently routed, disguised freighter from Alexandria to Malta. The disguised merchant ships Ardeola (2,609 tons) and Tadorna (1,947 tons) from Gibraltar, were captured and interned at Bizerta while passing through Vichy territorial waters. Welshman made a dash from Gibraltar with a cargo of dried food and torpedoes during the Allied landings in French North Africa (Operation Torch), Manxman and six destroyers sailed from Alexandria on 11 November; both efforts succeeded.[91] On 17 November, Convoy MW 13 (two U.S., one Dutch, and one British merchant ship, carrying 35,000 short tons (32,000 t) of supplies) departed Alexandria, escorted by three cruisers of the 15th Cruiser Squadron; from 18 November, this was reduced to ten destroyers. Axis air attacks began and after the main escort had detached, the cruiser HMS Arethusa was torpedoed and set on fire. Many of the air attacks were intercepted by Allied fighters flying from desert airfields and on 20 November, MW 13 arrived, escorted by Euryalus and ten Hunt-class destroyers. By 25 November, the ships had landed an adequate quantity of aviation fuel and Magic Carpet rides were cancelled. On 20 November, the minelayer HMS Adventure sailed from Plymouth to Gibraltar with 2,000 depth charges for Malta and made a repeat run in December.[92] The success of Stone Age relieved the siege of Malta, albeit by a narrow margin because the lack of military stores and food for the population would have been exhausted by December.[citation needed]

December 1942

[edit]Operation Portcullis

[edit]In Operation Portcullis, the five ships of Convoy MW 14 arrived from Port Said with 55,000 short tons (50,000 t) of supplies, the first convoy to arrive without loss since 1941.[93] Nine more ships arrived in Convoy MW 15 to Convoy MW 18, delivering 18,200 short tons (16,500 t) of fuel and another 58,500 short tons (53,100 t) of general supplies and military stores by the end of December; thirteen ships returned to Alexandria as Convoy ME 11 and Convoy ME 12. Increased rations to civilians helped to stave off the general decline in health of the population, which had led to an outbreak of poliomyelitis.[94]

| Convoy/ Operation |

From | Sailed | To | Arrived | No. | Lost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF 2 | Alexandria | 6 January | Malta | 8 January | 1 | 0 | |

| MF 2 | Malta | 6 January | Alexandria | 8 January | 1 | 0 | |

| MF 3, MW 8, MW 8A | Alexandria | 16 January | Malta | 19 January | 4 | 1 | |

| MF 4 | Alexandria | 24 January | Malta | 27 January | 1 | 0 | |

| MF 4 | Malta | 25 January | Alexandria | 28 January | 2 | 0 | |

| MF 5, MW 9 | Alexandria | 12 February | Malta | 15 February | 3 | 2 | |

| ME 10 | Malta | 13 February | Alexandria | 16 February | 3 | 0 | |

| MW 10 | Alexandria | 20 March | Malta | 23 March | 4 | 4 | |

| Harpoon | Gibraltar | 11 June | Malta | 15 June | 5 | 4 | |

| Vigorous | Alexandria | 12 June | Malta | — | 12 | 2 | Turned back |

| Pedestal | Gibraltar | 10 August | Malta | 14 August | 14 | 9 | |

| Independent | Alexandria | 1 November | Malta | 3 November | 1 | 0 | Not convoyed |

| Crupper | Gibraltar | 8 November | Malta | — | 2 | 2 | |

| MW 13 | Alexandria | 17 November | Malta | 20 November | 4 | 0 | |

| MW 14 | Port Said | 1 December | Malta | 5 December | 5 | 0 | |

| MW 15 | Port Said | 6 December | Malta | 10 December | 2 | 0 | |

| ME 11 | Malta | 7 December | Port Said | 11 December | 9 | 0 | |

| MW 16 | Alexandria | 11 December | Malta | 14 December | 3 | 0 | |

| ME 12 | Matla | 17 December | Port Said | 20 December | 4 | 0 | |

| MW 17 | Alexandria | 17 December | Malta | 21 December | 2 | 0 | |

| MW 18 | Alexandria | 28 December | Malta | 31 December | 2 | 0 |

December 1942 – January 1943

[edit]Operation Quadrangle

[edit]Portcullis was the last direct convoy to Malta; in Operations Quadrangle A, B, C and D, pairs of ships to Malta joined with ordinary west-bound convoys then rendezvoused with escorts from Force K, arriving with no loss.[93] In Operation Quadrangle A, Convoy MW 15 of two ships was a side convoy from the new Port Said to Benghazi service. When the main convoy arrived off Barce in Libya, the ships for Malta rendezvoused with eight destroyer escorts and empty ships from the island. The ships exchanged escorts for the return voyage to Grand Harbour, MW 15 arriving on 10 December. Operation Quadrangle B covered Convoy MW 16 of one tanker escorted by six destroyers and a minesweeper. Four ships of MW 13 were formed into Convoy MW 12 and nine destroyers departed Grand Harbour on 17 December. Quadrangle B was attacked by Ju 88s the next day to no effect. Several escorts handed over MW 12 at Barce to ships from Alexandria and took over Convoy MW 17, two freighters in Operation Quadrangle C to Malta. Convoy ME 13 was omitted and Convoy ME 14 with four empty ships sailed from Malta on 28 December with five destroyers. In December, 58,500 long tons (59,400 t) of general cargo and 18,200 long tons (18,500 t) of fuel oil was delivered. Convoy MW 18 with a tanker and a merchant ship departed from Alexandria in Operation Quadrangle D with six destroyer escorts, arriving at Malta on 2 January 1943.[95]

Operation Survey

[edit]Convoy MW 19 left Alexandria on 7 January 1943 with five freighters and a tanker with nine destroyers and survived an attack by torpedo bombers at dusk on 8 January. During a night attack, a merchantman and a destroyer were near-missed and a destroyer evaded a torpedo. On 9 January a storm slowed the tanker and the convoy missed the meeting with Force K and later made rendezvous with three Malta destroyers. As the storm abated the ships gathered speed and for most of the run to Malta Beaufighters provided air cover, one being vectored onto a He 111 during 11 January, which was attacked and driven off, the convoy arriving at Malta during the evening.[96]

Aftermath

[edit]Analysis

[edit]There were 35 large supply operations to Malta from 1940 to 1942. Operations White, Tiger, Halberd, MF5, MG1, Harpoon, Vigorous and Pedestal were turned back or suffered severe losses from Axis forces. There were long periods when no convoy runs were even attempted and only a trickle of supplies reached Malta by submarine or fast warship. The worst period for Malta was from December 1941 to October 1942, when Axis forces had air and naval supremacy in the central Mediterranean.[97]

Casualties

[edit]From June 1940 to December 1943, about 1,600 civilians and 700 soldiers were killed on Malta. The RAF lost about 900 men killed, 547 aircraft on operations and 160 on the ground and Royal Navy losses were 1,700 submariners and 2,200 sailors; about 200 merchant navy men died. Of 110 voyages by merchant ships to Malta 79 arrived, three to be sunk soon after reaching the island and one ship was sunk on a return voyage. Six of seven independent sailings failed, three ships being sunk, two were interned by Vichy authorities and one ship turned back. The Mediterranean Fleet lost a battleship, two aircraft carriers, four cruisers, a fast minelayer, twenty destroyers and minesweepers and forty submarines. Many small ships were sunk and many surviving ships were damaged.[98]

See also

[edit]- Bonner Fellers - the US military attaché in Egypt whose reports to Washington were being read by the Axis

- Mediterranean U-boat Campaign (World War II)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Data taken from Hague (2000) unless indicated.[26]

- ^ An Afrika Korps convoy (the Tarigo convoy) of the German ships Aegina, Arta, Adana and Iserlhon, with 3,000 troop reinforcements on board, the Italian Sabaudia loaded with ammunition and three Italian destroyer escorts was sunk by destroyers Jervis, Janus, Nubian and Mohawk, near the Kerkennah Islands off Tunisia; Mohawk was also sunk but the success showed the value of Malta as an offensive base. Churchill ordered that the Italian supply route to Tripoli be cut off and even suggested using the battleship Barham to block the harbour.[36]

- ^ Force K sank seven merchantmen and one of its destroyer escorts; the force was back at Malta by the afternoon of 9 November and the submarine Upholder from Malta sank another destroyer.[50]

- ^ Data taken from Hague (2000) unless indicated.[26]

- ^ The Dido-class cruisers were equipped with a main armament of dual-purpose QF 5.25-inch guns and had been designed for convoy protection and service in the Mediterranean.[58][59]

- ^ Data taken from Hague (2000) unless indicated.[26]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Roskill 1957, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Richards & Saunders 1975, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Potter & Nimitz 1960, pp. 654–661.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 324.

- ^ Greene & Massignani 2002, p. 225.

- ^ Playfair et al. 2004, p. 324.

- ^ a b c Roskill 1957, p. 298.

- ^ Playfair et al. 2004, p. 325.

- ^ Hooton 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Bartimeus 1944, pp. 42–47.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 293.

- ^ Potter & Nimitz 1960, pp. 521–527.

- ^ Helgason 2012.

- ^ a b Greene & Massignani 2002, pp. 63–81.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 58, 61.

- ^ a b c d Hague 2000, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 61–62, 64, 73–74.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 82, 86–87.

- ^ Greene & Massignani 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 97–105.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f Hague 2000, p. 192.

- ^ Thomas 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 110–111, 113–114, 125–126.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 131.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 423.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 156–157, 160, 162–163.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 164–166, 250.

- ^ Greene & Massignani 2002, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 431.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 165–167.

- ^ a b Lupinacci 1988, pp. 187–192.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 437.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 519.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2003, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Roskill 1957, pp. 423, 518.

- ^ a b Woodman 2003, pp. 184–185, 206–208, 212–213, 218.

- ^ Roskill 1957, pp. 521–523.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 524.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Roskill 1957, pp. 529–530.

- ^ Roskill 1957, pp. 530–531.

- ^ a b Roskill 1957, pp. 532–533.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 240–243.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 532.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 243–245.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 533.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 263–264, 267–268.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 268–270.

- ^ a b Roskill 1962, p. 44.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 485.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Roskill 1957, p. 295.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 282.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 48.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 73.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 291.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 293–295.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 300, 303.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 306–316.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 295, 317.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 320–322.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 321–322, 328.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 211, 328.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Roskill 1957, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Roskill 1957, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 339.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 329–370.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 283, 372–380, 386–442, 454–455, 463.

- ^ Castillo 2006, p. 207.

- ^ Woodman 2003, p. 283.

- ^ Castillo 2006, p. 199.

- ^ a b Woodman 2003, pp. 450–457.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 456–457.

- ^ DNC 1952, p. 376.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 340, 312.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 340.

- ^ a b Roskill 1962, p. 346.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 461–464.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 463–465.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 465–466.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 455, 467.

- ^ Woodman 2003, pp. 470–471.

References

[edit]Books

- Bartimeus, W. M. (1944). East of Malta, West of Suez. New York/Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 1727304.

- Castillo, Dennis Angelo (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-32329-4.

- Greene, J.; Massignani, A. (2002) [1998]. The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940–1943 (pbk. ed.). Rochester: Chatham. ISBN 978-1-86176-190-3.

- Hague, Arnold (2000). The Allied Convoy System 1939–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-019-9.

- H. M. Ships Damaged or Sunk by Enemy Action, 3rd September, 1939 to 2nd September, 1945 (PDF). London: HMSO (Admiralty: Director of Naval Construction). 1952. OCLC 38570200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Hooton, E. R. (2010) [1997]. Eagle in Flames: Defeat of the Luftwaffe. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-85409-343-1.

- Lupinacci, Pier Filippo (1988) [1966]. La guerra di mine [The Mine War] (in Italian) (2nd ed.). Roma: Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004) [1960]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: British Fortunes Reach Their Lowest Ebb (September 1941 to September 1942). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III (facs. pbk. Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-067-2.

- Potter, E. B.; Nimitz, C. W., eds. (1960). Sea Power. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 933965485.

- Richards, D.; Saunders, H. St G. (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–45: The Fight Avails. Vol. II (repr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Roskill, S. W. (1957) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Defensive. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (4th impr. ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 881709135. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. Vol. II (3rd impression ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

- Thomas, D. A. (1999). Malta Convoys. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-0-85052-663-9.

- Woodman, R. (2003). Malta Convoys 1940–1943 (pbk. ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6408-6.

Websites

- Helgason, Guðmundur (2012). "23rd Flotilla". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Llewellyn-Jones, M. (2007). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean Convoys: A Naval Staff History (1st ed.). Abingdon: The Whitehall History Publishing Consortium in association with Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-86459-6.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004a) [1960]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: British Fortunes Reach Their Lowest Ebb (September 1941 to September 1942). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III (Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-067-2.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; et al. (2004b) [HMSO 1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-068-9.

- Richards, Denis (1974) [1953]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight At Odds. Vol. I (paperback ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771592-9. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Santoro, G. (1957). L'aeronautica italiana nella seconda guerra mondiale [The Italian Air Force in the Second World War]. Vol. II (1st ed.). Milano-Roma: Edizione Esse. OCLC 60102091. semi-official history

Journals

[edit]- Caruana, Joseph (2012). "Emergency Victualling of Malta During WWII". Warship International. LXIX (4): 357–364. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Caruana, Joseph (2006). "Fighters to Malta". Warship International. XLIII (4): 383–393. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Vego, M. (Winter 2010). "Major Convoy Operation To Malta, 10–15 August 1942 (Operation Pedestal)". Naval War College Review. 63 (1). ISSN 0028-1484. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

Theses

[edit]- Hammond, R. J. (2011). The British Anti-shipping Campaign in the Mediterranean 1940–1944: Comparing Methods of Attack (PhD). registration. University of Exeter. OCLC 798399582. Docket uk.bl.ethos.548977. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

External links

[edit]- Mediterranean naval campaign

- Codenames: Operations of World War 2: Pinpoint access-date 6 March 2019

- Operation Harpoon

- Photos of Operation Pedestal

- Documentary film: Convoy to Malta Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Mediterranean Convoy Operations (London Gazette)

- NZETC Spitfires over Malta

- The Italian Navy in World War II

Malta convoys

View on GrokipediaBackground

Strategic Significance of Malta

Malta's strategic value in the Mediterranean theater of World War II stemmed from its acquisition by Britain during the Napoleonic Wars, formalized by the Treaty of Paris in 1814, which established the islands as a crown colony and key imperial outpost.[5] Prior to the war, British authorities had invested heavily in fortifications, including coastal batteries, anti-aircraft defenses, and underground shelters, recognizing Malta's vulnerability to aerial attack; Governor Sir William Dobbie accelerated these efforts in 1940, mobilizing local volunteers to construct over 13 miles of cave shelters and deploying limited air assets like three Sea Gladiator biplanes for initial defense.[6] These pre-war preparations transformed Malta into a fortified naval and air base, positioned just 60 miles south of Sicily and astride the shortest sea route between Italy and North Africa. Geopolitically, Malta served as a central hub for British forces to intercept and disrupt Italian and German convoys supplying Axis troops in North Africa, enabling submarines, aircraft, and surface vessels based there to target vulnerable shipping lanes.[6] By mid-1942, operations from Malta had sunk over 30% of Axis shipping destined for the region, with monthly losses reaching 35% in August and 38% in September, severely hampering General Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps and contributing to Allied victories such as El Alamein.[6] This offensive capability, bolstered by Ultra intelligence decrypts relayed to the island, allowed Malta to act as an unsinkable aircraft carrier, projecting power across the central Mediterranean and denying the Axis uncontested logistics. Economically, Malta's significance was amplified by its resource scarcity and role as a symbol of Allied resilience, sustaining a population of approximately 270,000 on limited arable land that covered less than 30% of the islands and produced insufficient food, necessitating constant imports of essentials like grain and fuel to maintain military operations and civilian life.[7] The island's endurance under relentless Axis bombing fostered high morale, epitomized by King George VI's award of the George Cross to the entire population in April 1942 for collective bravery, which flew from public buildings and became an enduring emblem of defiance against fascist aggression.[8]Mediterranean Theater and Axis Threats

Italy entered World War II on June 10, 1940, when Benito Mussolini declared war on France and Britain, immediately escalating threats in the Mediterranean theater where Italian forces sought to dominate sea lanes and support operations in North Africa.[9] This entry positioned the Regia Marina as the primary Axis naval power in the region, with its surface fleet comprising four battleships, 19 cruisers, and numerous destroyers and torpedo boats designed to challenge British control of vital routes like the Suez Canal and Gibraltar Strait.[10] The Italian submarine force, numbering 122 vessels at the war's outset, further augmented this threat by conducting ambushes on Allied shipping, though initial operations were hampered by defensive strategies to avoid direct confrontation with superior British forces.[10] German intervention intensified Axis pressure in early 1941 with the deployment of Fliegerkorps X to Sicily, where it arrived in January to bolster Italian efforts by targeting British naval movements and supply lines.[11] Equipped with Ju 88 bombers, Ju 87 Stukas, and Me 110 fighters, the corps quickly established Luftwaffe air superiority across the central Mediterranean from 1941 to mid-1942, launching relentless attacks that neutralized Allied airfields and convoys while protecting Axis reinforcements to Libya.[11] German U-boats, operating alongside Italian submarines, compounded these dangers by sinking key Allied vessels, such as the carrier HMS Eagle in August 1942, thereby disrupting efforts to sustain positions like Malta, which served as a critical outpost for interdicting Axis supplies.[12] To counter these escalating Axis capabilities, the British established Force H at Gibraltar in late June 1940 under Admiral James Somerville, tasking it with securing the western Mediterranean through aggressive patrols, carrier strikes, and support for relief operations against Italian surface threats.[13] Complementing this, the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet, based in Alexandria and commanded by Admiral Andrew Cunningham, engaged Italian forces in battles such as Calabria in July 1940 and Cape Matapan in March 1941, using battleships like HMS Warspite and aircraft carriers to sink cruisers and disrupt Axis convoy routes to North Africa.[14] These fleets' coordinated actions aimed to maintain open sea lanes despite the Luftwaffe's dominance, preventing total Axis control of the region during this period.[14]Initial Supply Challenges

At the outset of World War II, Malta's supply lines were severely constrained, relying primarily on unconventional methods such as submarine and aircraft deliveries due to the island's isolation in the central Mediterranean. Submarines, including early operations by the Royal Navy's Tenth Submarine Flotilla, transported small but critical cargoes of ammunition, medical supplies, and concentrated food, totaling around 500 tons in 1940, though these missions were hampered by the vessels' limited cargo capacity of typically 50-100 tons per trip. Aircraft deliveries, often via carrier-borne fighters like the Hawker Hurricanes flown off HMS Argus in July 1940, focused on bolstering air defenses rather than bulk goods, with only a handful of planes reaching the island amid high operational risks. These methods proved inadequate for sustaining the garrison of approximately 20,000 troops and 250,000 civilians, as Malta possessed just one major deep-water harbor at Valletta (Grand Harbour), which was prone to congestion, mining, and bombing damage that further impeded unloading operations.[15][12][3] The primary supply route from Gibraltar, spanning roughly 1,000 nautical miles in a sickle-shaped arc to evade initial threats, exposed shipments to relentless Axis air attacks launched from bases in Sardinia and Sicily, just 60-100 miles away. This "Sichelschnitt" path, intended to skirt the Strait of Sicily, left vessels vulnerable for much of the journey, as Italian and later German aircraft could strike with little warning, sinking or damaging early attempts at resupply. Environmental factors, including the Mediterranean's unpredictable weather and the need for speed to minimize exposure, compounded these dangers, making surface voyages nearly impossible without heavy escorts that were often unavailable in 1940.[3][2][12] Resource shortages escalated rapidly by late 1940, with fuel stocks rationed to essential military use as initial supply efforts provided only limited relief, leaving reserves sufficient for only about 22 weeks under strict controls. Food imports, vital for the civilian population dependent on external sources due to Malta's lack of arable land, dwindled to emergency levels, prompting hoarding and black-market activity. By October 1940, these constraints threatened the island's operational capacity, underscoring the urgent need for more robust convoy systems to avert starvation and operational paralysis.[16][1]Early Operations (1940–Early 1941)

Pioneering Convoys from Gibraltar

The pioneering convoys from Gibraltar in late 1940 represented the Royal Navy's initial forays to sustain Malta as a forward base in the Mediterranean, testing Axis interdiction capabilities while prioritizing high-value reinforcements like aircraft and fuel over large-scale merchant traffic. These operations, conducted under Force H commanded by Vice Admiral James Somerville, were characterized by their limited scale, heavy carrier support, and diversionary tactics to mask intentions from Italian reconnaissance. Successes were modest but vital, establishing viable routes despite air threats and demonstrating British naval superiority in surface actions. Operation Hurry, launched on 31 July 1940, focused on delivering urgently needed fighter aircraft to Malta's beleaguered garrison. The elderly aircraft carrier HMS Argus carried 12 Hawker Hurricane Mk I fighters, which were flown off approximately 170 nautical miles west of Malta on 2 August, successfully landing at Hal Far airfield to equip the newly formed No. 261 Squadron of the Royal Air Force. Escorted by Force H—including the battlecruiser HMS Renown, the carrier HMS Ark Royal, the battleship HMS Valiant, and several cruisers and destroyers—the operation avoided direct enemy contact but featured a diversionary strike by nine Swordfish torpedo bombers from Ark Royal against the Italian airfield at Cagliari on Sardinia, destroying several aircraft on the ground and sowing mines in the harbor approaches. All British forces returned to Gibraltar by 5 August without loss, marking the first "Club Run" for aircraft reinforcement and proving the feasibility of carrier-based delivery under cover of the main fleet.[17][18] Operation Hats, executed from 30 August to 6 September 1940, expanded on this model by incorporating supply deliveries alongside fleet maneuvers to reinforce the eastern Mediterranean squadron. Departing Gibraltar, Force H—comprising HMS Ark Royal, HMS Renown, the light cruiser HMS Sheffield, and eight destroyers—provided distant cover for a small convoy of three merchant vessels carrying ammunition, anti-aircraft equipment, and other stores, totaling around 3,500 tons of critical materiel. The merchants, supported by a close escort of destroyers from the Mediterranean Fleet, reached Malta on 2 September after fending off Italian air attacks that damaged but did not sink any ships; the cargo was unloaded promptly to bolster island defenses. Concurrently, the operation transferred the new carrier HMS Illustrious to Alexandria and involved Swordfish strikes from Ark Royal on Italian ports, while an Italian battle fleet was sighted but declined engagement, retreating to Taranto. This multi-phased effort highlighted the logistical challenges of synchronizing Gibraltar-based and Alexandria-based forces, achieving full delivery success without major casualties.[19][20] In October 1940, Operation MB 6 represented an escalation in supply efforts, though coordinated primarily from Alexandria with Gibraltar providing fleet cover; it included the first dedicated tanker element in a merchant convoy to address Malta's acute fuel shortages. Four freighters—Memnon (7,506 tons), Lanarkshire (9,816 tons), Clan Macaulay (10,492 tons), and Clan Ferguson (7,347 tons)—sailed as Convoy MF 3 under close escort by anti-aircraft cruisers HMS Calcutta and HMS Coventry, plus four destroyers, delivering approximately 35,000 tons of general cargo, including fuel and provisions, upon arrival at Malta on 11 October. Covered by the full Mediterranean Fleet (battleships HMS Warspite, HMS Valiant, HMS Malaya, and HMS Ramillies; carriers HMS Eagle and HMS Illustrious; multiple cruisers and destroyers), the convoy endured persistent Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica bombing, with HMS Liverpool sustaining torpedo damage but remaining operational. A notable success occurred during the return leg on 11-12 October, when the light cruiser HMS Ajax, screening the empty convoy near Cape Passero, Sicily, decisively engaged an Italian torpedo boat flotilla in the Battle of Cape Passero, sinking two torpedo boats (Airone and Ariel) and damaging the destroyer Artigliere, while suffering no British losses. This action underscored the protective value of cruiser squadrons against Italian surface raiders, ensuring the convoy's overall viability despite air harassment.[21]Winter Relief Efforts