Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cell signaling

View on WikipediaThis article's lead section may be too long. (March 2025) |

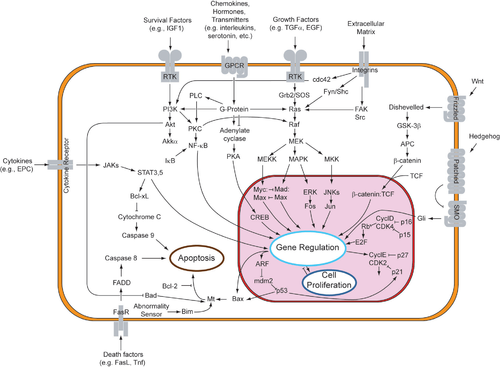

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the process by which a cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellular life in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Typically, the signaling process involves three components: the first messenger (the ligand), the receptor, and the signal itself.[1]

In biology, signals are mostly chemical in nature, but can also be physical cues such as pressure, voltage, temperature, or light. Chemical signals are molecules with the ability to bind and activate a specific receptor. These molecules, also referred to as ligands, are chemically diverse, including ions (e.g. Na+, K+, Ca2+, etc.), lipids (e.g. steroid, prostaglandin), peptides (e.g. insulin, ACTH), carbohydrates, glycosylated proteins (proteoglycans), nucleic acids, etc. Peptide and lipid ligands are particularly important, as most hormones belong to these classes of chemicals. Peptides are usually polar, hydrophilic molecules. As such they are unable to diffuse freely across the bi-lipid layer of the plasma membrane, so their action is mediated by a cell membrane bound receptor. On the other hand, liposoluble chemicals such as steroid hormones, can diffuse passively across the plasma membrane and interact with intracellular receptors.

Cell signaling can occur over short or long distances,[dubious – discuss]and can be further classified as autocrine, intracrine, juxtacrine, paracrine, or endocrine. Autocrine signaling occurs when the chemical signal acts on the same cell that produced the signaling chemical.[2] Intracrine signaling occurs when the chemical signal produced by a cell acts on receptors located in the cytoplasm or nucleus of the same cell.[3] Juxtacrine signaling occurs between physically adjacent cells.[4] Paracrine signaling occurs between nearby cells. Endocrine interaction occurs between distant cells, with the chemical signal usually carried by the blood.[5]

Receptors are complex proteins or tightly bound multimer of proteins, located in the plasma membrane or within the interior of the cell such as in the cytoplasm, organelles, and nucleus. Receptors have the ability to detect a signal either by binding to a specific chemical or by undergoing a conformational change when interacting with physical agents. It is the specificity of the chemical interaction between a given ligand and its receptor that confers the ability to trigger a specific cellular response. Receptors can be broadly classified into cell membrane receptors and intracellular receptors.

Cell membrane receptors can be further classified into ion channel linked receptors, G-Protein coupled receptors and enzyme linked receptors.

- Ion channels receptors are large transmembrane proteins with a ligand activated gate function. When these receptors are activated, they may allow or block passage of specific ions across the cell membrane. Most receptors activated by physical stimuli such as pressure or temperature belongs to this category.

- G-protein receptors are multimeric proteins embedded within the plasma membrane. These receptors have extracellular, trans-membrane and intracellular domains. The extracellular domain is responsible for the interaction with a specific ligand. The intracellular domain is responsible for the initiation of a cascade of chemical reactions which ultimately triggers the specific cellular function controlled by the receptor.

- Enzyme-linked receptors are transmembrane proteins with an extracellular domain responsible for binding a specific ligand and an intracellular domain with enzymatic or catalytic activity. Upon activation the enzymatic portion is responsible for promoting specific intracellular chemical reactions.

Intracellular receptors have a different mechanism of action. They usually bind to lipid soluble ligands that diffuse passively through the plasma membrane such as steroid hormones. These ligands bind to specific cytoplasmic transporters that shuttle the hormone-transporter complex inside the nucleus where specific genes are activated and the synthesis of specific proteins is promoted.

The effector component of the signaling pathway begins with signal transduction. In this process, the signal, by interacting with the receptor, starts a series of molecular events within the cell leading to the final effect of the signaling process. Typically the final effect consists in the activation of an ion channel (ligand-gated ion channel) or the initiation of a second messenger system cascade that propagates the signal through the cell. Second messenger systems can amplify or modulate a signal, in which activation of a few receptors results in multiple secondary messengers being activated, thereby amplifying the initial signal (the first messenger). The downstream effects of these signaling pathways may include additional enzymatic activities such as proteolytic cleavage, phosphorylation, methylation, and ubiquitinylation.

Signaling molecules can be synthesized from various biosynthetic pathways and released through passive or active transports, or even from cell damage.

Each cell is programmed to respond to specific extracellular signal molecules, and is the basis of development, tissue repair, immunity, and homeostasis. Errors in signaling interactions may cause diseases such as cancer, autoimmunity, and diabetes.

Taxonomic range

[edit]In many small organisms such as bacteria, quorum sensing enables individuals to begin an activity only when the population is sufficiently large. This signaling between cells was first observed in the marine bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri, which produces light when the population is dense enough.[6] The mechanism involves the production and detection of a signaling molecule, and the regulation of gene transcription in response. Quorum sensing operates in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, and both within and between species.[7]

In slime molds, individual cells aggregate together to form fruiting bodies and eventually spores, under the influence of a chemical signal, known as an acrasin. The individuals move by chemotaxis, i.e. they are attracted by the chemical gradient. Some species use cyclic AMP as the signal; others such as Polysphondylium violaceum use a dipeptide known as glorin.[8]

In plants and animals, signaling between cells occurs either through release into the extracellular space, divided in paracrine signaling (over short distances) and endocrine signaling (over long distances), or by direct contact, known as juxtacrine signaling such as notch signaling.[9] Autocrine signaling is a special case of paracrine signaling where the secreting cell has the ability to respond to the secreted signaling molecule.[10] Synaptic signaling is a special case of paracrine signaling (for chemical synapses) or juxtacrine signaling (for electrical synapses) between neurons and target cells.

Extracellular signal

[edit]Synthesis and release

[edit]

Many cell signals are carried by molecules that are released by one cell and move to make contact with another cell. Signaling molecules can belong to several chemical classes: lipids, phospholipids, amino acids, monoamines, proteins, glycoproteins, or gases. Signaling molecules binding surface receptors are generally large and hydrophilic (e.g. TRH, Vasopressin, Acetylcholine), while those entering the cell are generally small and hydrophobic (e.g. glucocorticoids, thyroid hormones, cholecalciferol, retinoic acid), but important exceptions to both are numerous, and the same molecule can act both via surface receptors or in an intracrine manner to different effects.[10] In animal cells, specialized cells release these hormones and send them through the circulatory system to other parts of the body. They then reach target cells, which can recognize and respond to the hormones and produce a result. This is also known as endocrine signaling. Plant growth regulators, or plant hormones, move through cells or by diffusing through the air as a gas to reach their targets.[11] Hydrogen sulfide is produced in small amounts by some cells of the human body and has a number of biological signaling functions. Only two other such gases are currently known to act as signaling molecules in the human body: nitric oxide and carbon monoxide.[12]

Exocytosis

[edit]Exocytosis is the process by which a cell transports molecules such as neurotransmitters and proteins out of the cell. As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use of energy to transport material. Exocytosis and its counterpart, endocytosis, the process that brings substances into the cell, are used by all cells because most chemical substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic portion of the cell membrane by passive transport. Exocytosis is the process by which a large amount of molecules are released; thus it is a form of bulk transport. Exocytosis occurs via secretory portals at the cell plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structures at the cell plasma membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.[13]

In the context of neurotransmission, neurotransmitters are typically released from synaptic vesicles into the synaptic cleft via exocytosis; however, neurotransmitters can also be released via reverse transport through membrane transport proteins.[citation needed]

Types of Cell Signaling

[edit]Autocrine

[edit]

Autocrine signaling involves a cell secreting a hormone or chemical messenger (called the autocrine agent) that binds to autocrine receptors on that same cell, leading to changes in the cell itself.[14] This can be contrasted with paracrine signaling, intracrine signaling, or classical endocrine signaling.

Intracrine

[edit]In intracrine signaling, the signaling chemicals are produced inside the cell and bind to cytosolic or nuclear receptors without being secreted from the cell. The intracrine signals not being secreted outside of the cell is what sets apart intracrine signaling from the other cell signaling mechanisms such as autocrine signaling. In both autocrine and intracrine signaling, the signal has an effect on the cell that produced it.[15]

Juxtacrine

[edit]Juxtacrine signaling is a type of cell–cell or cell–extracellular matrix signaling in multicellular organisms that requires close contact. There are three types:

- A membrane ligand (protein, oligosaccharide, lipid) and a membrane protein of two adjacent cells interact.

- A communicating junction links the intracellular compartments of two adjacent cells, allowing transit of relatively small molecules.

- An extracellular matrix glycoprotein and a membrane protein interact.

Additionally, in unicellular organisms such as bacteria, juxtacrine signaling means interactions by membrane contact. Juxtacrine signaling has been observed for some growth factors, cytokine and chemokine cellular signals, playing an important role in the immune response. Juxtacrine signalling via direct membrane contacts is also present between neuronal cell bodies and motile processes of microglia both during development,[16] and in the adult brain.[17]

Paracrine

[edit]

In paracrine signaling, a cell produces a signal to induce changes in nearby cells, altering the behaviour of those cells. Signaling molecules known as paracrine factors diffuse over a relatively short distance (local action), as opposed to cell signaling by endocrine factors, hormones which travel considerably longer distances via the circulatory system; juxtacrine interactions; and autocrine signaling. Cells that produce paracrine factors secrete them into the immediate extracellular environment. Factors then travel to nearby cells in which the gradient of factor received determines the outcome. However, the exact distance that paracrine factors can travel is not certain.

Paracrine signals such as retinoic acid target only cells in the vicinity of the emitting cell.[18] Neurotransmitters represent another example of a paracrine signal.

Some signaling molecules can function as both a hormone and a neurotransmitter. For example, epinephrine and norepinephrine can function as hormones when released from the adrenal gland and are transported to the heart by way of the blood stream. Norepinephrine can also be produced by neurons to function as a neurotransmitter within the brain.[19] Estrogen can be released by the ovary and function as a hormone or act locally via paracrine or autocrine signaling.[20]

Although paracrine signaling elicits a diverse array of responses in the induced cells, most paracrine factors utilize a relatively streamlined set of receptors and pathways. In fact, different organs in the body - even between different species - are known to utilize a similar sets of paracrine factors in differential development.[21] The highly conserved receptors and pathways can be organized into four major families based on similar structures: fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, Hedgehog family, Wnt family, and TGF-β superfamily. Binding of a paracrine factor to its respective receptor initiates signal transduction cascades, eliciting different responses.

Endocrine

[edit]

Endocrine signals are called hormones. Hormones are produced by endocrine cells and they travel through the blood to reach all parts of the body. Specificity of signaling can be controlled if only some cells can respond to a particular hormone. Endocrine signaling involves the release of hormones by internal glands of an organism directly into the circulatory system, regulating distant target organs. In vertebrates, the hypothalamus is the neural control center for all endocrine systems. In humans, the major endocrine glands are the thyroid gland and the adrenal glands. The study of the endocrine system and its disorders is known as endocrinology.

Receptors

[edit]

Cells receive information from their neighbors through a class of proteins known as receptors. Receptors may bind with some molecules (ligands) or may interact with physical agents like light, mechanical temperature, pressure, etc. Reception occurs when the target cell (any cell with a receptor protein specific to the signal molecule) detects a signal, usually in the form of a small, water-soluble molecule, via binding to a receptor protein on the cell surface, or once inside the cell, the signaling molecule can bind to intracellular receptors, other elements, or stimulate enzyme activity (e.g. gasses), as in intracrine signaling.

Signaling molecules interact with a target cell as a ligand to cell surface receptors, and/or by entering into the cell through its membrane or endocytosis for intracrine signaling. This generally results in the activation of second messengers, leading to various physiological effects. In many mammals, early embryo cells exchange signals with cells of the uterus.[22] In the human gastrointestinal tract, bacteria exchange signals with each other and with human epithelial and immune system cells.[23] For the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae during mating, some cells send a peptide signal (mating factor pheromones) into their environment. The mating factor peptide may bind to a cell surface receptor on other yeast cells and induce them to prepare for mating.[24]

Cell surface receptors

[edit]Cell surface receptors play an essential role in the biological systems of single- and multi-cellular organisms and malfunction or damage to these proteins is associated with cancer, heart disease, and asthma.[25] These trans-membrane receptors are able to transmit information from outside the cell to the inside because they change conformation when a specific ligand binds to it. There are three major types: Ion channel linked receptors, G protein–coupled receptors, and enzyme-linked receptors.

Ion channel linked receptors

[edit]

Ion channel linked receptors are a group of transmembrane ion-channel proteins which open to allow ions such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, and/or Cl− to pass through the membrane in response to the binding of a chemical messenger (i.e. a ligand), such as a neurotransmitter.[26][27][28]

When a presynaptic neuron is excited, it releases a neurotransmitter from vesicles into the synaptic cleft. The neurotransmitter then binds to receptors located on the postsynaptic neuron. If these receptors are ligand-gated ion channels (LICs), a resulting conformational change opens the ion channels, which leads to a flow of ions across the cell membrane. This, in turn, results in either a depolarization, for an excitatory receptor response, or a hyperpolarization, for an inhibitory response.

These receptor proteins are typically composed of at least two different domains: a transmembrane domain which includes the ion pore, and an extracellular domain which includes the ligand binding location (an allosteric binding site). This modularity has enabled a 'divide and conquer' approach to finding the structure of the proteins (crystallising each domain separately). The function of such receptors located at synapses is to convert the chemical signal of presynaptically released neurotransmitter directly and very quickly into a postsynaptic electrical signal. Many LICs are additionally modulated by allosteric ligands, by channel blockers, ions, or the membrane potential. LICs are classified into three superfamilies which lack evolutionary relationship: cys-loop receptors, ionotropic glutamate receptors and ATP-gated channels.

G protein–coupled receptors

[edit]

G protein-coupled receptors are a large group of evolutionarily-related proteins that are cell surface receptors that detect molecules outside the cell and activate cellular responses. Coupling with G proteins, they are called seven-transmembrane receptors because they pass through the cell membrane seven times. The G-protein acts as a "middle man" transferring the signal from its activated receptor to its target and therefore indirectly regulates that target protein.[29] Ligands can bind either to extracellular N-terminus and loops (e.g. glutamate receptors) or to the binding site within transmembrane helices (Rhodopsin-like family). They are all activated by agonists although a spontaneous auto-activation of an empty receptor can also be observed.[29]

G protein-coupled receptors are found only in eukaryotes, including yeast, choanoflagellates,[30] and animals. The ligands that bind and activate these receptors include light-sensitive compounds, odors, pheromones, hormones, and neurotransmitters, and vary in size from small molecules to peptides to large proteins. G protein-coupled receptors are involved in many diseases.

There are two principal signal transduction pathways involving the G protein-coupled receptors: cAMP signal pathway and phosphatidylinositol signal pathway.[31] When a ligand binds to the GPCR it causes a conformational change in the GPCR, which allows it to act as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF). The GPCR can then activate an associated G protein by exchanging the GDP bound to the G protein for a GTP. The G protein's α subunit, together with the bound GTP, can then dissociate from the β and γ subunits to further affect intracellular signaling proteins or target functional proteins directly depending on the α subunit type (Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11, Gα12/13).[32]: 1160

G protein-coupled receptors are an important drug target and approximately 34%[33] of all Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs target 108 members of this family. The global sales volume for these drugs is estimated to be 180 billion US dollars as of 2018[update].[33] It is estimated that GPCRs are targets for about 50% of drugs currently on the market, mainly due to their involvement in signaling pathways related to many diseases i.e. mental, metabolic including endocrinological disorders, immunological including viral infections, cardiovascular, inflammatory, senses disorders, and cancer. The long ago discovered association between GPCRs and many endogenous and exogenous substances, resulting in e.g. analgesia, is another dynamically developing field of pharmaceutical research.[29]

Enzyme-linked receptors

[edit]

Enzyme-linked receptors (or catalytic receptors) are transmembrane receptors that, upon activation by an extracellular ligand, causes enzymatic activity on the intracellular side.[34] Hence a catalytic receptor is an integral membrane protein possessing both enzymatic, catalytic, and receptor functions.[35]

They have two important domains, an extra-cellular ligand binding domain and an intracellular domain, which has a catalytic function; and a single transmembrane helix. The signaling molecule binds to the receptor on the outside of the cell and causes a conformational change on the catalytic function located on the receptor inside the cell.[citation needed] Examples of the enzymatic activity include:

- Receptor tyrosine kinase, as in fibroblast growth factor receptor. Most enzyme-linked receptors are of this type.[36]

- Receptor protein serine/threonine kinase, as in bone morphogenetic protein

- Guanylate cyclase, as in atrial natriuretic factor receptor

Intracellular receptors

[edit]Intracellular receptors exist freely in the cytoplasm, nucleus, or can be bound to organelles or membranes. For example, the presence of nuclear and mitochondrial receptors is well documented.[37] The binding of a ligand to the intracellular receptor typically induces a response in the cell. Intracellular receptors often have a level of specificity, this allows the receptors to initiate certain responses when bound to a corresponding ligand.[38] Intracellular receptors typically act on lipid soluble molecules. The receptors bind to a group of DNA binding proteins. Upon binding, the receptor-ligand complex translocates to the nucleus where they can alter patterns of gene expression.[citation needed]

Steroid hormone receptors are found in the nucleus, cytosol, and also on the plasma membrane of target cells. They are generally intracellular receptors (typically cytoplasmic or nuclear) and initiate signal transduction for steroid hormones which lead to changes in gene expression over a time period of hours to days. The best studied steroid hormone receptors are members of the nuclear receptor subfamily 3 (NR3) that include receptors for estrogen (group NR3A)[39] and 3-ketosteroids (group NR3C).[40] In addition to nuclear receptors, several G protein-coupled receptors and ion channels act as cell surface receptors for certain steroid hormones.

Mechanisms of Receptor Down-Regulation

[edit]Receptor mediated endocytosis is a common way of turning receptors "off". Endocytic down regulation is regarded as a means for reducing receptor signaling.[41] The process involves the binding of a ligand to the receptor, which then triggers the formation of coated pits, the coated pits transform to coated vesicles and are transported to the endosome.

Receptor Phosphorylation is another type of receptor down-regulation. Biochemical changes can reduce receptor affinity for a ligand.[42]

Reducing the sensitivity of the receptor is a result of receptors being occupied for a long time. This results in a receptor adaptation in which the receptor no longer responds to the signaling molecule. Many receptors have the ability to change in response to ligand concentration.[43]

Signal transduction pathways

[edit]When binding to the signaling molecule, the receptor protein changes in some way and starts the process of transduction, which can occur in a single step or as a series of changes in a sequence of different molecules (called a signal transduction pathway). The molecules that compose these pathways are known as relay molecules. The multistep process of the transduction stage is often composed of the activation of proteins by addition or removal of phosphate groups or even the release of other small molecules or ions that can act as messengers. The amplification of a signal is one of the benefits to this multiple step sequence. Other benefits include more opportunities for regulation than simpler systems do and the fine-tuning of the response, in both unicellular and multicellular organisms.[11]

In some cases, receptor activation caused by ligand binding to a receptor is directly coupled to the cell's response to the ligand. For example, the neurotransmitter GABA can activate a cell surface receptor that is part of an ion channel. GABA binding to a GABAA receptor on a neuron opens a chloride-selective ion channel that is part of the receptor. GABAA receptor activation allows negatively charged chloride ions to move into the neuron, which inhibits the ability of the neuron to produce action potentials. However, for many cell surface receptors, ligand-receptor interactions are not directly linked to the cell's response. The activated receptor must first interact with other proteins inside the cell before the ultimate physiological effect of the ligand on the cell's behavior is produced. Often, the behavior of a chain of several interacting cell proteins is altered following receptor activation. The entire set of cell changes induced by receptor activation is called a signal transduction mechanism or pathway.[44]

A more complex signal transduction pathway is the MAPK/ERK pathway, which involves changes of protein–protein interactions inside the cell, induced by an external signal. Many growth factors bind to receptors at the cell surface and stimulate cells to progress through the cell cycle and divide. Several of these receptors are kinases that start to phosphorylate themselves and other proteins when binding to a ligand. This phosphorylation can generate a binding site for a different protein and thus induce protein–protein interaction. In this case, the ligand (called epidermal growth factor, or EGF) binds to the receptor (called EGFR). This activates the receptor to phosphorylate itself. The phosphorylated receptor binds to an adaptor protein (GRB2), which couples the signal to further downstream signaling processes. For example, one of the signal transduction pathways that are activated is called the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. The signal transduction component labeled as "MAPK" in the pathway was originally called "ERK," so the pathway is called the MAPK/ERK pathway. The MAPK protein is an enzyme, a protein kinase that can attach phosphate to target proteins such as the transcription factor MYC and, thus, alter gene transcription and, ultimately, cell cycle progression. Many cellular proteins are activated downstream of the growth factor receptors (such as EGFR) that initiate this signal transduction pathway.[citation needed]

Some signaling transduction pathways respond differently, depending on the amount of signaling received by the cell. For instance, the hedgehog protein activates different genes, depending on the amount of hedgehog protein present.[citation needed]

Complex multi-component signal transduction pathways provide opportunities for feedback, signal amplification, and interactions inside one cell between multiple signals and signaling pathways.[citation needed]

A specific cellular response is the result of the transduced signal in the final stage of cell signaling. This response can essentially be any cellular activity that is present in a body. It can spur the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton, or even as catalysis by an enzyme. These three steps of cell signaling all ensure that the right cells are behaving as told, at the right time, and in synchronization with other cells and their own functions within the organism. At the end, the end of a signal pathway leads to the regulation of cellular activity. This response can take place in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm of the cell. A majority of signaling pathways control protein synthesis by turning certain genes on and off in the nucleus. [45]

In unicellular organisms such as bacteria, signaling can be used to 'activate' peers from a dormant state, enhance virulence, defend against bacteriophages, etc.[46] In quorum sensing, which is also found in social insects, the multiplicity of individual signals has the potentiality to create a positive feedback loop, generating coordinated response. In this context, the signaling molecules are called autoinducers.[47][48][49] This signaling mechanism may have been involved in evolution from unicellular to multicellular organisms.[47][50] Bacteria also use contact-dependent signaling, notably to limit their growth.[51]

Signaling molecules used by multicellular organisms are often called pheromones. They can have such purposes as alerting against danger, indicating food supply, or assisting in reproduction.[52]

Short-term cellular responses

[edit]| Receptor Family | Example of Ligands/ activators (Bracket: receptor for it) | Example of effectors | Further downstream effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Gated Ion Channels | Acetylcholine (such as Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor), |

Changes in membrane permeability | Change in membrane potential |

| Seven Helix Receptor | Light (Rhodopsin), Dopamine (Dopamine receptor), GABA (GABA receptor), Prostaglandin (prostaglandin receptor) etc. |

Trimeric G protein | Adenylate Cyclase, cGMP phosphodiesterase, G-protein gated ion channel, etc. |

| Two-component | Diverse activators | Histidine Kinase | Response Regulator - flagellar movement, Gene expression |

| Membrane Guanylyl Cyclase | Atrial natriuretic peptide, Sea urchin egg peptide etc. |

cGMP | Regulation of Kinases and channels- Diverse actions |

| Cytoplasmic Guanylyl cyclase | Nitric Oxide (Nitric oxide receptor) | cGMP | Regulation of cGMP Gated channels, Kinases |

| Integrins | Fibronectins, other extracellular matrix proteins | Nonreceptor tyrosine kinase | Diverse response |

Regulating gene activity

[edit]| Frizzled (special type of 7Helix receptor) | Wnt | Dishevelled, axin - APC, GSK3-beta - Beta catenin | Gene expression |

| Two-component | Diverse activators | Histidine Kinase | Response Regulator - flagellar movement, Gene expression |

| Receptor Tyrosine Kinase | Insulin (insulin receptor), EGF (EGF receptor), FGF-Alpha, FGF-Beta, etc. (FGF-receptors) |

Ras, MAP-kinases, PLC, PI3-Kinase | Gene expression change |

| Cytokine receptors | Erythropoietin, Growth Hormone (Growth Hormone Receptor), IFN-Gamma (IFN-Gamma receptor) etc. |

JAK kinase | STAT transcription factor - Gene expression |

| Tyrosine kinase Linked- receptors | MHC-peptide complex - TCR, Antigens - BCR | Cytoplasmic Tyrosine Kinase | Gene expression |

| Receptor Serine/Threonine Kinase | Activin (activin receptor), Inhibin, Bone-morphogenetic protein (BMP Receptor), TGF-beta |

Smad transcription factors | Control of gene expression |

| Sphingomyelinase linked receptors | IL-1 (IL-1 receptor), TNF (TNF-receptors) |

Ceramide activated kinases | Gene expression |

| Cytoplasmic Steroid receptors | Steroid hormones, Thyroid hormones, Retinoic acid etc. |

Work as/ interact with transcription factors | Gene expression |

Notch signaling pathway

[edit]

Notch is a cell surface protein that functions as a receptor. Animals have a small set of genes that code for signaling proteins that interact specifically with Notch receptors and stimulate a response in cells that express Notch on their surface. Molecules that activate (or, in some cases, inhibit) receptors can be classified as hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, and growth factors, in general called receptor ligands. Ligand receptor interactions such as that of the Notch receptor interaction, are known to be the main interactions responsible for cell signaling mechanisms and communication.[55] Notch acts as a receptor for ligands that are expressed on adjacent cells. While some receptors are cell-surface proteins, others are found inside cells. For example, estrogen is a hydrophobic molecule that can pass through the lipid bilayer of the membranes. As part of the endocrine system, intracellular estrogen receptors from a variety of cell types can be activated by estrogen produced in the ovaries.[citation needed]

In the case of Notch-mediated signaling, the signal transduction mechanism can be relatively simple. As shown in Figure 2, the activation of Notch can cause the Notch protein to be altered by a protease. Part of the Notch protein is released from the cell surface membrane and takes part in gene regulation. Cell signaling research involves studying the spatial and temporal dynamics of both receptors and the components of signaling pathways that are activated by receptors in various cell types.[56][57] Emerging methods for single-cell mass-spectrometry analysis promise to enable studying signal transduction with single-cell resolution.[58]

In notch signaling, direct contact between cells allows for precise control of cell differentiation during embryonic development. In the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, two cells of the developing gonad each have an equal chance of terminally differentiating or becoming a uterine precursor cell that continues to divide. The choice of which cell continues to divide is controlled by competition of cell surface signals. One cell will happen to produce more of a cell surface protein that activates the Notch receptor on the adjacent cell. This activates a feedback loop or system that reduces Notch expression in the cell that will differentiate and that increases Notch on the surface of the cell that continues as a stem cell.[59]

See also

[edit]- Scaffold protein

- Biosemiotics

- Molecular cellular cognition

- Crosstalk (biology)

- Bacterial outer membrane vesicles

- Membrane vesicle trafficking

- Host–pathogen interaction

- Retinoic acid

- JAK-STAT signaling pathway

- Imd pathway

- Localisation signal

- Oscillation

- Protein dynamics

- Systems biology

- Lipid signaling

- Redox signaling

- Signaling cascade

- Cell Signaling Technology – an antibody development and production company

- Netpath – a curated resource of signal transduction pathways in humans

- Synthetic Biology Open Language

- Nanoscale networking – leveraging biological signaling to construct ad hoc in vivo communication networks

- Soliton model in neuroscience – physical communication via sound waves in membranes

- Temporal feedback

References

[edit]- ^ Nair, Arathi; Chauhan, Prashant; Saha, Bhaskar; Kubatzky, Katharina F. (2019-07-04). "Conceptual Evolution of Cell Signaling". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (13): 3292. doi:10.3390/ijms20133292. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 6651758. PMID 31277491.

- ^ Pandit, Nita K. (2007). Introduction to the pharmaceutical sciences (1st ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-4478-2.

- ^ Re, Richard N. (April 2003). "The intracrine hypothesis and intracellular peptide hormone action". BioEssays. 25 (4): 401–409. doi:10.1002/bies.10248. PMID 12655647.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F.; Tyler, Mary S.; Kozlowski, Ronald N. (2000). Developmental biology (6th ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Assoc. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- ^ "Hormones". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ^ Nealson, K.H.; Platt, T.; Hastings, J.W. (1970). "Cellular control of the synthesis and activity of the bacterial luminescent system". Journal of Bacteriology. 104 (1): 313–22. doi:10.1128/jb.104.1.313-322.1970. PMC 248216. PMID 5473898.

- ^ Bassler, Bonnie L. (1999). "How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2 (6): 582–587. doi:10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00025-9. PMID 10607620.

- ^ Shimomura, O; Suthers, H L; Bonner, J T (December 1982). "Chemical identity of the acrasin of the cellular slime mold Polysphondylium violaceum". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 79 (23): 7376–7379. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.7376S. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.23.7376. PMC 347342. PMID 6961416.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). "Juxtacrine Signaling". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ a b Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002). "General Principles of Cell Communication". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). Garland Science.

- ^ a b Reece JB (Sep 27, 2010). Campbell Biology. Benjamin Cummings. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-321-55823-7.

- ^ Cooper, Geoffrey M. (2000). "Signaling Molecules and Their Receptors". The Cell: A Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Jena, Bhanu (2009). "Porosome: the secretory portal in cells". Biochemistry. 48 (19). ACS Publications: 4009–4018. doi:10.1021/bi9002698. PMC 4580239. PMID 19364126.

- ^ Pandit, Nikita K. (2007). Introduction To The Pharmaceutical Sciences. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-7817-4478-2.

- ^ Rubinow, Katya B. (September 2018). "An intracrine view of sex steroids, immunity, and metabolic regulation". Molecular Metabolism. 15: 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2018.03.001. PMC 6066741. PMID 29551633.

- ^ Cserép, Csaba; Schwarcz, Anett D.; Pósfai, Balázs; László, Zsófia I.; Kellermayer, Anna; Környei, Zsuzsanna; Kisfali, Máté; Nyerges, Miklós; Lele, Zsolt; Katona, István (September 2022). "Microglial control of neuronal development via somatic purinergic junctions". Cell Reports. 40 (12) 111369. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111369. PMC 9513806. PMID 36130488.

- ^ Cserép, Csaba; Pósfai, Balázs; Lénárt, Nikolett; Fekete, Rebeka; László, Zsófia I.; Lele, Zsolt; Orsolits, Barbara; Molnár, Gábor; Heindl, Steffanie; Schwarcz, Anett D.; Ujvári, Katinka; Környei, Zsuzsanna; Tóth, Krisztina; Szabadits, Eszter; Sperlágh, Beáta; Baranyi, Mária; Csiba, László; Hortobágyi, Tibor; Maglóczky, Zsófia; Martinecz, Bernadett; Szabó, Gábor; Erdélyi, Ferenc; Szipőcs, Róbert; Tamkun, Michael M.; Gesierich, Benno; Duering, Marco; Katona, István; Liesz, Arthur; Tamás, Gábor; Dénes, Ádám (31 January 2020). "Microglia monitor and protect neuronal function through specialized somatic purinergic junctions" (PDF). Science. 367 (6477): 528–537. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..528C. doi:10.1126/science.aax6752. PMID 31831638.

- ^ Duester G (September 2008). "Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis". Cell. 134 (6): 921–31. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. PMC 2632951. PMID 18805086.

- ^ Cartford MC, Samec A, Fister M, Bickford PC (2004). "Cerebellar norepinephrine modulates learning of delay classical eyeblink conditioning: evidence for post-synaptic signaling via PKA". Learning & Memory. 11 (6): 732–7. doi:10.1101/lm.83104. PMC 534701. PMID 15537737.

- ^ Jesmin S, Mowa CN, Sakuma I, Matsuda N, Togashi H, Yoshioka M, Hattori Y, Kitabatake A (October 2004). "Aromatase is abundantly expressed by neonatal rat penis but downregulated in adulthood". Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 33 (2): 343–59. doi:10.1677/jme.1.01548. PMID 15525594.

- ^ Gilbert, Scott F. (2000). "Paracrine Factors". Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Mohamed OA, Jonnaert M, Labelle-Dumais C, Kuroda K, Clarke HJ, Dufort D (June 2005). "Uterine Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for implantation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (24): 8579–84. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.8579M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500612102. PMC 1150820. PMID 15930138.

- ^ Clarke MB, Sperandio V (June 2005). "Events at the host-microbial interface of the gastrointestinal tract III. Cell-to-cell signaling among microbial flora, host, and pathogens: there is a whole lot of talking going on". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 288 (6): G1105–9. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00572.2004. PMID 15890712.

- ^ Lin JC, Duell K, Konopka JB (March 2004). "A microdomain formed by the extracellular ends of the transmembrane domains promotes activation of the G protein-coupled alpha-factor receptor". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (5): 2041–51. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.5.2041-2051.2004. PMC 350546. PMID 14966283.

- ^ Han R, Bansal D, Miyake K, Muniz VP, Weiss RM, McNeil PL, Campbell KP (July 2007). "Dysferlin-mediated membrane repair protects the heart from stress-induced left ventricular injury". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (7): 1805–13. doi:10.1172/JCI30848. PMC 1904311. PMID 17607357.

- "Faulty Cell Membrane Repair Causes Heart Disease". ScienceDaily (Press release). July 6, 2007.

- ^ "Gene Family: Ligand gated ion channels". HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee.

- ^ "ligand-gated channel" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Purves, Dale; George J. Augustine; David Fitzpatrick; William C. Hall; Anthony-Samuel LaMantia; James O. McNamara; Leonard E. White (2008). Neuroscience. 4th ed. Sinauer Associates. pp. 156–7. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.

- ^ a b c Trzaskowski B, Latek D, Yuan S, Ghoshdastider U, Debinski A, Filipek S (2012). "Action of molecular switches in GPCRs--theoretical and experimental studies". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 19 (8): 1090–109. doi:10.2174/092986712799320556. PMC 3343417. PMID 22300046.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5) Archived 22 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine license.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Attribution 2.5 Generic (CC BY 2.5) Archived 22 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine license.

- ^ King N, Hittinger CT, Carroll SB (July 2003). "Evolution of key cell signaling and adhesion protein families predates animal origins". Science. 301 (5631): 361–3. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..361K. doi:10.1126/science.1083853. PMID 12869759.

- ^ Gilman AG (1987). "G proteins: transducers of receptor-generated signals". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 56 (1): 615–49. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. PMID 3113327.

- ^ Wettschureck N, Offermanns S (October 2005). "Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions". Physiological Reviews. 85 (4): 1159–204. doi:10.1152/physrev.00003.2005. PMID 16183910.

- ^ a b Hauser AS, Chavali S, Masuho I, Jahn LJ, Martemyanov KA, Gloriam DE, Babu MM (January 2018). "Pharmacogenomics of GPCR Drug Targets". Cell. 172 (1–2): 41–54.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.033. PMC 5766829. PMID 29249361.

- ^ Ronald W. Dudek (1 November 2006). High-yield cell and molecular biology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6887-0. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA (February 2007). "Catalytic Receptors". Br. J. Pharmacol. 150 Suppl 1 (S1): S122–7. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707205. PMC 2013840.

- ^ "lecture10". Archived from the original on 2007-05-25. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ Lee, Junghee; Sharma, Swati; Kim, Jinho; Ferrante, Robert J.; Ryu, Hoon (April 2008). "Mitochondrial Nuclear Receptors and Transcription Factors: Who's Minding the Cell?". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 86 (5): 961–971. doi:10.1002/jnr.21564. PMC 2670446. PMID 18041090.

- ^ Clark, James H.; Peck, Ernest J. (1984). "Intracellular Receptors: Characteristics and Measurement". Biological Regulation and Development. pp. 99–127. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4619-8_3. ISBN 978-1-4757-4621-1.

- ^ Dahlman-Wright K, Cavailles V, Fuqua SA, Jordan VC, Katzenellenbogen JA, Korach KS, Maggi A, Muramatsu M, Parker MG, Gustafsson JA (Dec 2006). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 58 (4): 773–81. doi:10.1124/pr.58.4.8. PMID 17132854.

- ^ Lu NZ, Wardell SE, Burnstein KL, Defranco D, Fuller PJ, Giguere V, Hochberg RB, McKay L, Renoir JM, Weigel NL, Wilson EM, McDonnell DP, Cidlowski JA (Dec 2006). "International Union of Pharmacology. LXV. The pharmacology and classification of the nuclear receptor superfamily: glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, progesterone, and androgen receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 58 (4): 782–97. doi:10.1124/pr.58.4.9. PMID 17132855.

- ^ Roepstorff, Kirstine; Grøvdal, Lene; Grandal, Michael; Lerdrup, Mads; van Deurs, Bo (May 2008). "Endocytic downregulation of ErbB receptors: mechanisms and relevance in cancer". Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 129 (5): 563–578. doi:10.1007/s00418-008-0401-3. PMC 2323030. PMID 18288481.

- ^ Li, Xin; Huang, Yao; Jiang, Jing; Frank, Stuart J. (November 2008). "ERK-dependent threonine phosphorylation of EGF receptor modulates receptor downregulation and signaling". Cellular Signalling. 20 (11): 2145–2155. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.08.006. PMC 2613789. PMID 18762250.

- ^ Schwartz, Alan L. (December 1995). "Receptor Cell Biology: Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis". Pediatric Research. 38 (6): 835–843. doi:10.1203/00006450-199512000-00003. PMID 8618782.

- ^ Dinasarapu AR, Saunders B, Ozerlat I, Azam K, Subramaniam S (June 2011). "Signaling gateway molecule pages--a data model perspective". Bioinformatics. 27 (12): 1736–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr190. PMC 3106186. PMID 21505029.

- ^ Reece JB (Sep 27, 2010). Campbell Biology (9th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-321-55823-7.

- ^ Mukamolova GV, Kaprelyants AS, Young DI, Young M, Kell DB (July 1998). "A bacterial cytokine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (15): 8916–21. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.8916M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.8916. PMC 21177. PMID 9671779.

- ^ a b Miller MB, Bassler BL (1 October 2001). "Quorum sensing in bacteria". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55 (1): 165–99. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. PMID 11544353.

- ^ Kaper JB, Sperandio V (June 2005). "Bacterial cell-to-cell signaling in the gastrointestinal tract". Infection and Immunity. 73 (6): 3197–209. doi:10.1128/IAI.73.6.3197-3209.2005. PMC 1111840. PMID 15908344.

- ^ Camilli A, Bassler BL (February 2006). "Bacterial small-molecule signaling pathways". Science. 311 (5764): 1113–6. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1113C. doi:10.1126/science.1121357. PMC 2776824. PMID 16497924.

- ^ Stoka AM (June 1999). "Phylogeny and evolution of chemical communication: an endocrine approach". Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 22 (3): 207–25. doi:10.1677/jme.0.0220207. PMID 10343281.

- ^ Blango MG, Mulvey MA (April 2009). "Bacterial landlines: contact-dependent signaling in bacterial populations". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 12 (2): 177–81. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.011. PMC 2668724. PMID 19246237.

- ^ Tirindelli R, Dibattista M, Pifferi S, Menini A (July 2009). "From pheromones to behavior". Physiological Reviews. 89 (3): 921–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.460.5566. doi:10.1152/physrev.00037.2008. PMID 19584317.

- ^ a b Cell biology/Pollard et al,[full citation needed][page needed]

- ^ a b The Cell/ G.M. Cooper[full citation needed][page needed]

- ^ Cooper, Geoffrey M. (2000). "Functions of Cell Surface Receptors". The Cell: A Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Ferrell JE, Machleder EM (May 1998). "The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes". Science. 280 (5365): 895–8. Bibcode:1998Sci...280..895F. doi:10.1126/science.280.5365.895. PMID 9572732.

- ^ Slavov N, Carey J, Linse S (April 2013). "Calmodulin transduces Ca2+ oscillations into differential regulation of its target proteins". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 4 (4): 601–12. doi:10.1021/cn300218d. PMC 3629746. PMID 23384199.

- ^ Slavov N (January 2020). "Unpicking the proteome in single cells". Science. 367 (6477): 512–513. Bibcode:2020Sci...367..512S. doi:10.1126/science.aaz6695. PMC 7029782. PMID 32001644.

- ^ Greenwald I (June 1998). "LIN-12/Notch signaling: lessons from worms and flies". Genes & Development. 12 (12): 1751–62. doi:10.1101/gad.12.12.1751. PMID 9637676.

Further reading

[edit]- "The Inside Story of Cell Communication". learn.genetics.utah.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- "When Cell Communication Goes Wrong". learn.genetics.utah.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

External links

[edit]- NCI-Nature Pathway Interaction Database: authoritative information about signaling pathways in human cells.

- Intercellular+Signaling+Peptides+and+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Cell+Communication at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Signaling Pathways Project: cell signaling hypothesis generation knowledgebase constructed using biocurated archived transcriptomic and ChIP-Seq datasets