Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

View on Wikipedia

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 19,000 words. (July 2025) |

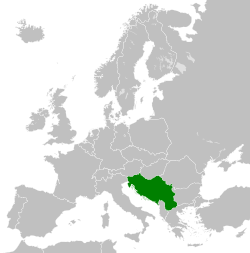

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (commonly abbreviated as SFRY or SFR Yugoslavia), known from 1945 to 1963 as the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as Socialist Yugoslavia or simply Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It was established in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, dissolving amid the onset of the Yugoslav Wars. Spanning an area of 255,804 square kilometres (98,766 sq mi) in the Balkans, Yugoslavia was bordered by the Adriatic Sea and Italy to the west, Austria and Hungary to the north, Bulgaria and Romania to the east, and Albania and Greece to the south. It was a one-party socialist state and federation governed by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, and had six constituent republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. Within Serbia was the Yugoslav capital city of Belgrade as well as two autonomous Yugoslav provinces: Kosovo and Vojvodina.

Key Information

The country emerged as Democratic Federal Yugoslavia on 29 November 1943, during the second session of the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia midst World War II in Yugoslavia. Recognised by the Allies of World War II at the Tehran Conference as the legal successor state to Kingdom of Yugoslavia, it was a provisionally governed state formed to unite the Yugoslav resistance movement. Following the country's liberation, King Peter II was deposed, the monarchical rule was ended, and on 29 November 1945, the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was proclaimed. Led by Josip Broz Tito, the new communist government sided with the Eastern Bloc at the beginning of the Cold War but pursued a policy of neutrality following the 1948 Tito–Stalin split; it became a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, and transitioned from a command economy to market-based socialism. The country was renamed Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963.

After Tito died on 4 May 1980, the Yugoslav economy began to collapse, which increased unemployment and inflation.[9][10] The economic crisis led to rising ethnic nationalism and political dissidence in the late 1980s and early 1990s. With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, efforts to transition into a confederation failed; the two wealthiest republics, Croatia and Slovenia, seceded and gained some international recognition in 1991. The federation dissolved along the borders of federated republics, hastened by the start of the Yugoslav Wars, and formally broke up on 27 April 1992. Two republics, Serbia and Montenegro, remained within a reconstituted state known as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, or FR Yugoslavia, but this state was not recognized internationally as the sole successor state to SFR Yugoslavia. "Former Yugoslavia" is now commonly used retrospectively.

The FPR Yugoslavia and, later SFRY, was a founding member of the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

Name

[edit]The name Yugoslavia, an anglicised transcription of Jugoslavija, is a compound word made up of jug ('yug'; with the 'j' pronounced like an English 'y') and slavija. The Slavic word jug means 'south', while slavija ("Slavia") denotes a 'land of the Slavs'. Thus, a translation of Jugoslavija would be 'South-Slavia' or 'Land of the South Slavs'. The federation's official name varied considerably between 1945 and 1992.[11] Yugoslavia was formed in 1918 under the name Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In January 1929, King Alexander I assumed dictatorship of the kingdom and renamed it the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, for the first time making "Yugoslavia"—which had been used colloquially for decades (even before the country was formed)—the state's official name.[11] After the Axis occupied the kingdom during World War II, the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) announced in 1943 the formation of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (DF Yugoslavia or DFY) in the country's substantial resistance-controlled areas. The name deliberately left the republic-or-kingdom question open. In 1945, King Peter II was officially deposed, with the state reorganized as a republic, and accordingly renamed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPR Yugoslavia or FPRY), with the constitution coming into force in 1946.[12] In 1963, amid pervasive liberal constitutional reforms, the name Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was introduced. The state is most commonly called by that name, which it held for the longest period. Of the three main Yugoslav languages, the Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian names for the state were identical, while Slovene slightly differed in capitalization and the spelling of the adjective Socialist. The names are as follows:

- Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian

- Latin: Socijalistička Federativna Republika Jugoslavija

- Cyrillic: Социјалистичка Федеративна Република Југославија

- Serbo-Croatian pronunciation: [sot͡sijalǐstit͡ʃkaː fêderatiːʋnaː repǔblika juɡǒslaːʋija]

- Macedonian pronunciation: [sɔt͡sijaˈlistit͡ʃka fɛdɛraˈtivna rɛˈpublika juɡɔˈsɫavija]

- Slovene

- Socialistična federativna republika Jugoslavija

- Slovene pronunciation: [sɔtsijaˈlìːstitʃna fɛdɛraˈtíːwna rɛˈpùːblika juɡɔˈslàːʋija]

Due to the name's length, abbreviations were often used for the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, though it was most commonly known simply as Yugoslavia. The most common abbreviation is SFRY, though "SFR Yugoslavia" was also used in an official capacity, particularly by the media.

History

[edit]World War II

[edit]

On 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers led by Nazi Germany; by 17 April 1941, the country was fully occupied and was soon carved up by the Axis. Yugoslav resistance was soon established in two forms, the Royal Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Communist Yugoslav Partisans.[13] The Partisan supreme commander was Josip Broz Tito. Under his command, the movement soon began establishing "liberated territories" that attracted the occupying forces' attention. Unlike the various nationalist militias operating in occupied Yugoslavia, the Partisans were a pan-Yugoslav movement promoting the "brotherhood and unity" of Yugoslav nations and representing the Yugoslav political spectrum's republican, left-wing, and socialist elements. The coalition of political parties, factions, and prominent individuals behind the movement was the People's Liberation Front (Jedinstveni narodnooslobodilački front, JNOF), led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ).

The Front formed a representative political body, the Anti-Fascist Council for the People's Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ, Antifašističko Veće Narodnog Oslobođenja Jugoslavije).[14] The AVNOJ met for the first time in Partisan-liberated Bihać on 26 November 1942 (First Session of the AVNOJ) and claimed the status of Yugoslavia's deliberative assembly (parliament).[11][14][15]

In 1943, the Yugoslav Partisans began attracting serious attention from the Germans. In two major operations, Fall Weiss (January to April 1943) and Fall Schwartz (15 May to 16 June 1943), the Axis attempted to stamp out the Yugoslav resistance once and for all. In the Battle of the Neretva and the Battle of the Sutjeska, the 20,000-strong Partisan Main Operational Group engaged a force of around 150,000 combined Axis troops.[14] In both battles, despite heavy casualties, the Group evaded the trap and retreated to safety. The Partisans emerged stronger than before, occupying a more significant portion of Yugoslavia. The events greatly increased the Partisans' standing and granted them a favourable reputation among the Yugoslav populace, leading to increased recruitment. On 8 September 1943, Fascist Italy capitulated to the Allies, leaving their occupation zone in Yugoslavia open to the Partisans. Tito took advantage of this by briefly liberating the Dalmatian shore and its cities. This secured Italian weaponry and supplies for the Partisans, volunteers from the cities previously annexed by Italy, and Italian recruits crossing over to the Allies (the Garibaldi Division).[11][15] After this favourable chain of events, the AVNOJ decided to meet for the second time, in Partisan-liberated Jajce. The Second Session of the AVNOJ lasted from 21 to 29 November 1943 (right before and during the Tehran Conference) and came to a number of conclusions. The most significant of these was the establishment of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia, a state that would be a federation of six equal South Slavic republics (as opposed to the allegedly Serb predominance in pre-war Yugoslavia). The council decided on a "neutral" name and deliberately left the question of "monarchy vs. republic" open, ruling that Peter II would be allowed to return from exile in London only upon a favourable result of a pan-Yugoslav referendum on the question.[15] Among other decisions, the AVNOJ formed a provisional executive body, the National Committee for the Liberation of Yugoslavia (NKOJ, Nacionalni komitet oslobođenja Jugoslavije), appointing Tito as prime minister. Having achieved success in the 1943 engagements, Tito was also granted the rank of Marshal of Yugoslavia. Favourable news also came from the Tehran Conference when the Allies concluded that the Partisans would be recognized as the Allied Yugoslav resistance movement and granted supplies and wartime support against the Axis occupation.[15]

As the war turned decisively against the Axis in 1944, the Partisans continued to hold significant chunks of Yugoslav territory.[clarification needed] With the Allies in Italy, the Yugoslav islands of the Adriatic Sea were a haven for the resistance. On 17 June 1944, the Partisan base on the island of Vis housed a conference between Prime Minister Tito of the NKOJ (representing the AVNOJ) and Prime Minister Ivan Šubašić of the royalist Yugoslav government-in-exile in London.[16] The conclusions, known as the Tito-Šubašić Agreement, granted the King's recognition to the AVNOJ and the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (DFY) and provided for the establishment of a joint Yugoslav coalition government headed by Tito with Šubašić as the foreign minister, with the AVNOJ confirmed as the provisional Yugoslav parliament.[15] Peter II's government-in-exile in London, partly due to pressure from the United Kingdom,[17] recognized the state in the agreement, signed by Šubašić and Tito on 17 June 1944.[17] The DFY's legislature, after November 1944, was the Provisional Assembly.[18] The Tito-Šubašić agreement of 1944 declared that the state was a pluralist democracy that guaranteed democratic liberties; personal freedom; freedom of speech, assembly, and religion; and a free press.[19] But by January 1945, Tito had shifted his government's emphasis away from pluralist democracy, claiming that though he accepted democracy, multiple parties were unnecessarily divisive amid Yugoslavia's war effort, and that the People's Front represented all the Yugoslav people.[19] The People's Front coalition, headed by the KPJ and its general secretary Tito, was a major movement within the government. Other political movements that joined the government included the "Napred" movement represented by Milivoje Marković.[18] Belgrade, Yugoslavia's capital, was liberated with the Soviet Red Army's help in October 1944, and the formation of a new Yugoslav government was postponed until 2 November 1944, when the Belgrade Agreement was signed. The agreements also provided for postwar elections to determine the state's future system of government and economy.[15]

By 1945, the Partisans were clearing out Axis forces and liberating the remaining parts of occupied territory. On 20 March, the Partisans launched their General Offensive in a drive to completely oust the Germans and the remaining collaborating forces.[14] By the end of April, the remaining northern parts of Yugoslavia were liberated, and Yugoslav troops occupied chunks of southern German (Austrian) territory and Italian territory around Trieste. Yugoslavia was now once more a fully intact state, with its borders closely resembling their pre-1941 form, and was envisioned by the Partisans as a "Democratic Federation", including six federated states: the Federated State of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FS Bosnia and Herzegovina), Federated State of Croatia (FS Croatia), Federated State of Macedonia (FS Macedonia), Federated State of Montenegro (FS Montenegro), Federated State of Serbia (FS Serbia), and Federated State of Slovenia (FS Slovenia).[15][20] But the nature of its government remained unclear, and Tito was reluctant to include the exiled King Peter II in post-war Yugoslavia, as Winston Churchill demanded. In February 1945, Tito acknowledged the existence of a Regency Council representing the King, but the council's first and only act was to proclaim a new government under Tito's premiership.[21] The nature of the state was still unclear immediately after the war, and on 26 June 1945, the government signed the United Nations Charter using only Yugoslavia as an official name, with no reference to either a kingdom or a republic.[22][23] Acting as head of state on 7 March, the King appointed to his Regency Council constitutional lawyers Srđan Budisavljević, Ante Mandić, and Dušan Sernec. In doing so, he empowered his council to form a common temporary government with NKOJ and accept Tito's nomination as prime minister of the first normal government. The Regency Council thus accepted Tito's nomination on 29 November 1945 when FPRY was declared. With this unconditional transfer of power, King Peter II abdicated to Tito.[24] This date, when the second Yugoslavia was born under international law, was thereafter marked as Yugoslavia's national holiday Day of the Republic, but after the Communists' switch to authoritarianism, this holiday officially marked the 1943 Session of AVNOJ that coincidentally[clarification needed][citation needed] fell on the same date.[25]

In the first months after the end of the war, the Partisans were ruthless in executing alleged collaborators along with anyone perceived to be their enemy.[26] An American OSS officer reported from Dubrovnik: "The inhabitants were living in a state of mortal terror...The Partisan attitude was that anybody who had stayed in town during the occupation and didn't work in the Partisan underground was ipso facto a collaborator. The dreaded secret police was going to work and people were being taken from their homes to the old castle and shot everyday".[27] One witness reported in the early summer of 1945: "In Crnogrob there are mass graves. Trucks are bringing men with bound hands and feet every evening from the prison in Škofja Loka and none are ever seen again. Every evening one hears shots from Crnogrob".[26] In July 1945, Tito ordered a stop to summary executions, but it was not until the fall of 1945 that the mass executions finally stopped.[26] In Kosovo, there was an uprising that was only put down in the summer of 1945 as many Albanians did not want to rejoin Yugoslavia, and much preferred to join Albania.[28] In attempt to settle the long-standing "Macedonian question", Tito declared the Macedonians to be one of the official nationalities of Yugoslavia and created a republic for Macedonia.[29] It was declared that Macedonians did not speak Bulgarian, but rather their own language, leading to the publication of several books meant to promote standard Macedonian.[30]

Postwar period

[edit]The first Yugoslav post-World War II elections were set for 11 November 1945. By that time, the coalition of parties backing the Partisans, the People's Liberation Front (Jedinstveni narodnooslobodilački front, JNOF), had been renamed the People's Front (Narodni front, NOF) and was primarily led by the KPJ and represented by Tito. The reputation of both benefited greatly from their wartime exploits and decisive success, and they enjoyed genuine support among the populace. But the old pre-war political parties were also reestablished.[20] As early as January 1945, while the enemy was still occupying the northwest, Tito commented:

I am not in principle against political parties because democracy also presupposes the freedom to express one's principles and one's ideas. But to create parties for the sake of parties, now, when all of us, as one, must direct all our strength in the direction of driving the occupying forces from our country, when the homeland has been razed to the ground when we have nothing but our awareness and our hands ... we have no time for that now. And here is a popular movement [the People's Front]. Everyone is welcome within it, both communists and those who were Democrats and radicals, etc., whatever they were called before. This movement is the force, the only force which can now lead our country out of this horror and misery and bring it to complete freedom.

— Marshal Josip Broz Tito, January 1945[20]

While the elections themselves were fairly conducted by a secret ballot, the campaign that preceded them was highly irregular.[15] Opposition newspapers were banned on more than one occasion, and in Serbia, opposition leaders such as Milan Grol received threats via the press. The opposition withdrew from the election in protest, which caused the three royalist representatives, Grol, Šubašić, and Juraj Šutej, to secede from the provisional government. Indeed, voting was on a single list of People's Front candidates with provision for opposition votes to be cast in separate voting boxes, a procedure that made electors identifiable by OZNA agents.[31][32] The election results of 11 November 1945 were decisively in favour of the People's Front, which received an average of 85% of the vote in each federated state.[15] On 29 November, the second anniversary of the Second Session of the AVNOJ, the Constituent Assembly of Yugoslavia formally abolished the monarchy and declared the state a republic. The country's official name became the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPR Yugoslavia, FPRY), and the six federated states became "People's Republics".[20][33] Yugoslavia became a one-party state and was considered in its earliest years a model of Communist orthodoxy.[34] The principle concern of the new regime was rebuilding a country devastated by the war under the slogan "No rest while we're rebuilding!"[35] During the war, over a million people had been killed in Yugoslavia while 3.5 million were homeless in 1945 and 289,000 businesses had been completely wrecked.[36] One-third of Yugoslav industries had been destroyed in the war and every single mine in the country had been wrecked.[36] In 1944–1945, the Wehrmacht staged its standard "scorched earth" policy while retreating, and systematically destroyed bridges, railroads, telephone lines, electrical plants, roads, factories and mines, leaving Yugoslavia in ruins.[36] The new regime mobilised thousands of people, especially young people, into work brigades that saw to rebuild the country.[36] Between 1945 and 1953, Yugoslavia received a sum equal to $553.8 million US dollars to help rebuild from various sources, including $419 million from the United Nations.[36]

In 1947, Tito launched an ambitious Five-Year Plan, closely modelled after the First Five-Year Plan in the Soviet Union, that placed the first emphasis on investing in shipyards, machine manufacturing, and the electrical industry along with reopening the iron and coal mines with the aim of making Yugoslavia into a major producer of steel.[37] A major weakness for the old Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a lack of an arms industry, and Tito intended for Communist Yugoslavia to be self-sufficient in arms, leading for dozens upon of arms factories being opened in Bosnia and Serbia in the late 1940s-early 1950s.[38] By the mid-1950s, Tito had nearly achieved his aim of military autarky with virtually all the weapons being used by the Yugoslav People's Army being manufactured in Yugoslavia and the country later became a major exporter of arms to the Third World.[39] Between 1947 and 1949, a third of the national income was invested in heavy industry and the number of Yugoslav workers increased fourfold to two million.[39] Between 1953 and 1960, Yugoslavia's industrial production increased by 13.83% annually, which gave Yugoslavia a higher rate of industrialization than Japan during the same decade, albeit Yugoslavia was starting from a much lower basis than Japan.[39] Between 1947 and 1957, the population of Belgrade and Sarajevo increased by 18%, the population of Skopje by 36% and Zenica, which had been chosen as a new industrial by 53%.[39]

The post-war era saw the flight or expulsions of the Italian and German minorities.[40] Before the war, Yugoslavia had a population of half-million volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans), of whom the majority fled to the Reich in 1944–1945.[40] The volksdeutsche were favored during the occupation, and many had served in the SS Prinz Eugen division that had been used to hunt down partisans, making the volksdeutsche the object of much hatred and distrust from the new regime.[40] Of the remaining 200,000 volksdeutsche living in Yugoslavia in 1945, the entire community had all of its assets confiscated by the new regime (including those volksdeutsch who joined the Partisans) and the volksdeutsche were placed into camps prior to their expulsion.[30] In Dalmatia and Istria, there were massacres known as the foibe massacres of Italians who were suspected of supporting the Fascist regime, and the remaining Italians all either fled or were expelled.[26]

Women had played a prominent role in the Partisans with about 100,000 having served in the Partisans between 1941 and 1945 as messengers, saboteurs, commissars, nurses, doctors, and soldiers.[41] The female veterans insisted that they would expect equality in new Yugoslavia.[41] In 1945, women were given the right to vote and hold office.[42] The new regime favored giving Partisan veterans positions in the civil service, through this often caused problems.[43] About two-thirds of the Communist party members in 1945 came from working class or peasant families, and many were barely literate.[43] In October 1945, the Ministry of Forestry issued a memo saying that food and cigarettes were not to be tossed out of windows; spitting in the hallways was not acceptable and there was a "purpose and a proper way to use toilets".[42] The memory of the Second World War was ubiquitous in post-war Yugoslavia with most of the holidays such as Fighters' Day on 4 July and Army Day on 22 December having something to do with the war, and most of the local holidays likewise had something to do with the war.[44] Over 200 feature films were released in post-war Yugoslavia about the Partisans, several of which became massive hits such as Walter Defends Sarajevo and Battle on the Neretva.[45] The Communist regime constructed a legend under which depicted almost all of the Yugoslav peoples rallying under the leadership of Tito in the People's Liberation War as the war was called in Yugoslavia to resist the occupation.[44] At least for a time, this legend served as an unifying factor.[44]

The Yugoslav government allied with the Soviet Union under Stalin and early in the Cold War shot down two American airplanes flying in Yugoslav airspace, on 9 and 19 August 1946. These were the first aerial shootdowns of western aircraft during the Cold War and caused deep distrust of Tito in the United States and even calls for military intervention against Yugoslavia.[46] The new Yugoslavia also closely followed the Stalinist Soviet model of economic development in this period, some aspects of which achieved considerable success. In particular, the public works of the period organized by the government rebuilt and even improved Yugoslav infrastructure (in particular the road system) with little cost to the state. Tensions with the West were high as Yugoslavia joined the Cominform, and the early phase of the Cold War began with Yugoslavia pursuing an aggressive foreign policy.[15] Having liberated most of the Julian March and Carinthia, and with historic claims to both those regions, the Yugoslav government began diplomatic maneuvering to include them in Yugoslavia. The West opposed both these demands. The greatest point of contention was the port city of Trieste. The city and its hinterland were liberated mostly by the Partisans in 1945, but pressure from the western Allies forced them to withdraw to the so-called "Morgan Line". The Free Territory of Trieste was established and separated into Zones A and B, administered by the western Allies and Yugoslavia, respectively. Yugoslavia was initially backed by Stalin, but by 1947 he had begun to cool toward its ambitions. The crisis eventually dissolved as the Tito–Stalin split started, with Zone A granted to Italy and Zone B to Yugoslavia.[15][20]

Meanwhile, civil war raged in Greece – Yugoslavia's southern neighbour – between Communists and the right-wing government, and the Yugoslav government was determined to bring about a Communist victory.[15][20] Yugoslavia dispatched significant assistance—arms and ammunition, supplies, and military experts on partisan warfare (such as General Vladimir Dapčević)—and even allowed the Greek Communist forces to use Yugoslav territory as a safe haven. Although the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, and (Yugoslav-dominated) Albania had also granted military support, Yugoslav assistance was far more substantial. But this Yugoslav foreign adventure also came to an end with the Tito–Stalin split, as the Greek Communists, expecting Tito's overthrow, refused any assistance from his government. Without it, they were greatly disadvantaged, and were defeated in 1949.[20] As Yugoslavia was the country's only Communist neighbour in the immediate postwar period, the People's Republic of Albania was effectively a Yugoslav satellite. Neighboring Bulgaria was under increasing Yugoslav influence as well, and talks began to negotiate the political unification of Albania and Bulgaria with Yugoslavia. The major point of contention was that Yugoslavia wanted to absorb the two and transform them into additional federated republics. Albania was in no position to object, but the Bulgarian view was that a new Balkan Federation would see Bulgaria and Yugoslavia as a whole uniting on equal terms. As these negotiations began, Yugoslav representatives Edvard Kardelj and Milovan Đilas were summoned to Moscow alongside a Bulgarian delegation, where Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov attempted to browbeat them into accepting Soviet control over the merger between the countries, and generally tried to force them into subordination.[20] The Soviets did not express a specific view on Yugoslav-Bulgarian unification but wanted to ensure Moscow approved every decision by both parties. The Bulgarians did not object, but the Yugoslav delegation withdrew from the Moscow meeting. Recognizing the level of Bulgarian subordination to Moscow, Yugoslavia withdrew from the unification talks and shelved plans for the annexation of Albania in anticipation of a confrontation with the Soviet Union.[20]

From the beginning, the foreign policy of the Yugoslav government under Tito assigned high importance to developing strong diplomatic relations with other nations, including those outside the Balkans and Europe. Yugoslavia quickly established formal relations with India, Burma, and Indonesia following their independence from the British and Dutch colonial empires. Official relations between Yugoslavia and the Republic of China were established with the Soviet Union's permission. Simultaneously, Yugoslavia maintained close contacts with the Chinese Communist Party and supported its cause in the Chinese Civil War.[47]

Informbiro period

[edit]| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

The Tito–Stalin, or Yugoslav–Soviet split, took place in the spring and early summer of 1948. Its title pertains to Tito, at the time the Yugoslav Prime Minister (President of the Federal Assembly), and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. In the West, Tito was thought of as a loyal Communist leader, second only to Stalin in the Eastern Bloc. However, having largely liberated itself with only limited Red Army support,[14] Yugoslavia steered an independent course and was constantly experiencing tensions with the Soviet Union. Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav government considered themselves allies of Moscow, while Moscow considered Yugoslavia a satellite and often treated it as such. Previous tensions erupted over a number of issues, but after the Moscow meeting, an open confrontation was beginning.[20] Next came an exchange of letters directly between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ). In the first CPSU letter of 27 March 1948, the Soviets accused the Yugoslavs of denigrating Soviet socialism via statements such as "socialism in the Soviet Union has ceased to be revolutionary". It also claimed that the KPJ was not "democratic enough", and that it was not acting as a vanguard that would lead the country to socialism. The Soviets said that they "could not consider such a Communist party organization to be Marxist-Leninist, Bolshevik". The letter also named a number of high-ranking officials as "dubious Marxists" (Milovan Đilas, Aleksandar Ranković, Boris Kidrič, and Svetozar Vukmanović-Tempo) inviting Tito to purge them, and thus cause a rift in his own party. Communist officials Andrija Hebrang and Sreten Žujović supported the Soviet view.[15][20] Tito, however, saw through it, refused to compromise his own party, and soon responded with his own letter. The KPJ response on 13 April 1948 was a strong denial of the Soviet accusations, both defending the revolutionary nature of the party and re-asserting its high opinion of the Soviet Union. However, the KPJ noted also that "no matter how much each of us loves the land of socialism, the Soviet Union, he can in no case love his own country less".[20] In a speech, the Yugoslav Prime Minister stated:

We are not going to pay the balance on others' accounts, we are not going to serve as pocket money in anyone's currency exchange, we are not going to allow ourselves to become entangled in political spheres of interest. Why should it be held against our peoples that they want to be completely independent? And why should autonomy be restricted, or the subject of dispute? We will not be dependent on anyone ever again!

— Prime Minister Josip Broz Tito[20]

The 31-page-long Soviet answer of 4 May 1948 admonished the KPJ for failing to admit and correct its mistakes, and went on to accuse it of being too proud of their successes against the Germans, maintaining that the Red Army had "saved them from destruction" (an implausible statement, as Tito's partisans had successfully campaigned against Axis forces for four years before the appearance of the Red Army there).[14][20] This time, the Soviets named Tito and Edvard Kardelj as the principal "heretics", while defending Hebrang and Žujović. The letter suggested that the Yugoslavs bring their "case" before the Cominform. The KPJ responded by expelling Hebrang and Žujović from the party, and by answering the Soviets on 17 May 1948 with a letter which sharply criticized Soviet attempts to devalue the successes of the Yugoslav resistance movement.[20] On 19 May 1948, a correspondence by Mikhail Suslov informed Tito that the Cominform (Informbiro in Serbo-Croatian), would be holding a session on 28 June 1948 in Bucharest almost completely dedicated to the "Yugoslav issue". The Cominform was an association of Communist parties that was the primary Soviet tool for controlling the political developments in the Eastern Bloc. The date of the meeting, 28 June, was carefully chosen by the Soviets as the triple anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo Field (1389), the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo (1914), and the adoption of the Vidovdan Constitution (1921).[20] Tito, personally invited, refused to attend under a dubious excuse of illness. When an official invitation arrived on 19 June 1948, Tito again refused. On the first day of the meeting, 28 June, the Cominform adopted the prepared text of a resolution, known in Yugoslavia as the "Resolution of the Informbiro" (Rezolucija Informbiroa). In it, the other Cominform (Informbiro) members expelled Yugoslavia, citing "nationalist elements" that had "managed in the course of the past five or six months to reach a dominant position in the leadership" of the KPJ. The resolution warned Yugoslavia that it was on the path back to bourgeois capitalism due to its nationalist, independence-minded positions, and accused the party itself of "Trotskyism".[20] This was followed by the severing of relations between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, beginning the period of Soviet–Yugoslav conflict between 1948 and 1955 known as the Informbiro Period.[20]

After the break with the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia found itself economically and politically isolated as the country's Eastern Bloc-oriented economy began to falter. At the same time, Stalinist Yugoslavs, known in Yugoslavia as "cominformists", began fomenting civil and military unrest. A number of cominformist rebellions and military insurrections took place, along with acts of sabotage. However, the Yugoslav security service (UDBA) led by Aleksandar Ranković, was quick and efficient in cracking down on insurgent activity. Much of the Yugoslav Communist Party membership was loyal to the Soviet Union and between 1948 and 1955 over 55,600 party members were expelled as "Cominformists".[48] The two most prominent pro-Soviet members to be expelled were the Croat Andrija Hebrang and the Serb Sreten Žujović.[48] Invasion appeared imminent, as Soviet military units massed along the border with the Hungarian People's Republic, while the Hungarian People's Army was quickly increased in size from 2 to 15 divisions. The UDBA began arresting alleged Cominformists even under suspicion of being pro-Soviet. However, from the start of the crisis, Tito began making overtures to the United States and the West. Consequently, Stalin's plans were thwarted as Yugoslavia began shifting its alignment. About approximately 16,000 people were convicted of being "Cominformists" and/or of being "suspicious" and sent to the concentration camp on the island of Goli Otok to be "reeducated".[48] Most of those convicted of being "Cominformists" and sent to Goli Otok were party members who fought with the Partisans during the Second World War, and were for this reason treated in an especially harsh manner for siding with Stalin against Tito.[48] However, Tito's defiant stance against the Soviet Union won him much popular respect that lasted for decades with a librarian from Zagreb saying in the early 1970s: "I don't like him, but I guess we all respect him for having stood up to the Russians and having kept us out of their clutches".[48]

The West welcomed the Yugoslav-Soviet rift and, in 1949 commenced a flow of economic aid, assisted in averting famine in 1950, and covered much of Yugoslavia's trade deficit for the next decade. The United States began shipping weapons to Yugoslavia in 1951. Tito, however, was wary of becoming too dependent on the West as well, and military security arrangements concluded in 1953 as Yugoslavia refused to join NATO and began developing a significant military industry of its own.[49][50] With the American response in the Korean War serving as an example of the West's commitment, Stalin began backing down from war with Yugoslavia. The Truman administration misunderstood the Tito-Stalin split as a sign that Yugoslavia would ally with the West, and it took some time for those in positions in power in Washington to understand that Tito wanted Yugoslavia to be neutral in the Cold War.[48]

Reform

[edit]

This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (July 2025) |

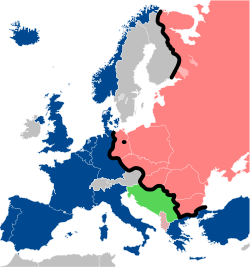

Yugoslavia began a number of fundamental reforms in the early 1950s, bringing about change in three major directions: rapid liberalization and decentralization of the country's political system, the institution of a new, unique economic system, and a diplomatic policy of non-alignment. Edvard Kardelj, the chief ideologue of the Communist regime, in a 1949 article "On People's Democracy", harshly criticised the Stalinist regimes in the Soviet Union for becoming a bureaucratic dictatorship that had merged party and state into one, and had elevated itself over Soviet society.[51] Taking a phrase from Frederich Engels, Kardeji called for a "withering state", arguing that ordinary people should placed in charge of their workplaces to create the sort of society that Karl Marx and Engels had envisioned in the 19th century.[51] In 1950, Kardeji along with Milovan Djilas, Moša Pijade, Boris Kidrič and Vladimir Bakarić drafted the "Basic Law on the Management of State Economic Enterprises" that called for councils elected by the workers to manage businesses along with a decentralisation of state management of the economy.[51] Yugoslavia refused to take part in the Communist Warsaw Pact and instead took a neutral stance in the Cold War, becoming a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement along with countries like India, Egypt and Indonesia, and pursuing centre-left influences that promoted a non-confrontational policy towards the United States. The country distanced itself from the Soviets in 1948 and started to build its own way to socialism under the strong political leadership of Tito, sometimes informally called "Titoism". Tito reveled in the role of a world leader, and between 1944 and 1980 made 169 official visits to 92 nations, and in the process he met 175 heads of state along with 110 prime ministers.[52] These frequent visits abroad served an important propaganda function, namely to show that Tito as one of the leaders of the non-aligned movement was an important world leader because Yugoslavia was an important nation.[52]

The economic reforms began with the introduction of workers' self-management in June 1950. In this system, profits were shared among the workers themselves as workers' councils controlled production and the profits. An industrial sector began to emerge thanks to the government's implementation of industrial and infrastructure development programs.[15][20] Exports of industrial products, led by heavy machinery, transportation machines (especially in the shipbuilding industry), and military technology and equipment rose by a yearly increase of 11%. All in all, the annual growth of the gross domestic product (GDP) through to the early 1980s averaged 6.1%.[15][20] Political liberalization began with the reduction of the massive state (and party) bureaucratic apparatus, a process described as the "whittling down of the state" by Boris Kidrič, President of the Yugoslav Economic Council (economics minister). On 2 November 1952, the Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia introduced the "Basic Law", which emphasized the "personal freedom and rights of man" and the freedom of "free associations of working people". The Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) changed its name at this time to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY/SKJ), becoming a federation of six republican Communist parties. The result was a regime that was somewhat more humane than other Communist states. However, the LCY retained absolute power; as in all Communist regimes, the legislature did little more than rubber-stamp decisions already made by the LCY's Politburo. The UDBA, while operating with considerably more restraint than its counterparts in the rest of Eastern Europe, was nonetheless a feared tool of government control. UDBA was particularly notorious for assassinating suspected "enemies of the state" who lived in exile overseas.[53][unreliable source?] The media remained under restrictions that were somewhat onerous by Western standards, but still had somewhat more latitude than their counterparts in other Communist countries. Nationalist groups were a particular target of the authorities, with numerous arrests and prison sentences handed down over the years for separatist activities.[citation needed] Dissent from a radical faction within the party led by Milovan Đilas, advocating the near-complete annihilation of the state apparatus, was at this time put down by Tito's intervention.[15][20]

The post-war period saw a rapid urbanization with some 5.5 million people leaving the countryside for the cities between 1945 and 1970.[54] By 1969, the population of Belgrade passed the one million mark for the first time; that year, it was estimated that two of three Belgradians had been born in the countryside.[54] In the late 1950s, the car manufacturer Zastava in Kragujevac began the production under license from Fiat of a small car, known officially as the Fiat 600 and unofficially as the fiċo that become ubiquitous in Yugoslavia for decades afterward.[55] By 1968, about 8% of the Yugoslav population owned a car, and the majority were the fiċo, which became a symbol of Yugoslavia itself.[55] In 1947, it was estimated that one radio set was shared by an average of 70 people; by 1965, the typical radio set was shared by an average of 7 people.[54] Increased literacy led to a massive demand for books with an average of 13,000 books being published annually in the 1960s.[54] In 1945, one out of every two Yugoslavs were illiterate; by 1961 the illiteracy rate had fallen to 20% of the population.[56] By 1953, 71% of all Yugoslav children finished elementary school and by 1981, 97% of all Yugoslav children finished school.[56] In 1945, Yugoslavia had three universities and two institutions of higher learning.[57] By 1965, Yugoslavia had 158 universities and colleges.[57] With the exceptions of the Soviet Union, Sweden, and the Netherlands, no European country had quite as many university students.[57] By 1960, about 500, 000 Yugoslavs were attending university and by 1970 the number had reached 650, 000.[57] The composition of the Communist Party/League of Communists changed during the post-war decades.[57] Of the 12,000 people who were party members in 1941, only 3, 000 survived World War Two with the rest all being killed.[57] After 1945, the party took in a massive number of new members, the majority of whom came from either a peasant or working-class background.[57] In 1945, every second party member had a peasant background, every third member had a working-class background and every tenth member had a white collar background.[57] By 1966, the membership of the League of Communists was mostly made up of people from a middle-class background with 39% of all league members having a white collar job while league members with a peasant background made up 7% of the membership.[57] By the early 1960s, the so-called "socialist bourgeoise" had emerged as the dominant class both politically and economically.[57] The typical "socialist bourgeoise" was someone with a university education who held a management job; or worked as an engineer or some other technical skilled trade; or was a member of the new capitalist class, usually a restaurant owner or someone who became rich as a result of the tourism trade.[57] By the mid-1960s, the League of Communists had by large and ceased to be an ideological party committed to Marxism, and instead become just a vehicle for social advancement of ambitious careerists.[58] League members were more interested in obtaining status symbols such as luxury cars, large houses, expensive clothing and the vikendica (weekend cottage) than in creating a Marxist society.[59] One League member told a Western journalist in 1965: "We go to Trieste about twice a year to buy clothes and cosmetics, Italian clothing is really not of a better quality than ours, but we want something others don't have, even if it costs us a lot of money".[59] In 1962, a group of dissenting Marxist intellectuals founded the journal Praxis, which was discreetly critical of the regime.[60] The major theme of the Praxis group was "alienation" and "humanity" with the argument that people were becoming more "alienated" from society and the solution was they proposed was freedom of speech, multiparty democracy, and more decentralization of the federation.[61]

Increased prosperity led to higher television ownership. In 1960, there were 30,000 television sets in operation in all of Yugoslavia.[62] By 1964, there were 440, 000 television sets in operation in Yugoslavia.[62] The greater number of people who owned televisions led to the end of the traditional evening get-together known as the sijelo that once formed the focus of social life in Yugoslavia as people were too busy watching television in the evening.[62] Censorship was less extreme than elsewhere in Eastern Europe in the 1960s, not the less because the authorities could only prosecute a journalist after an article had been published, not just for writing an article as was the case in the rest of Eastern Europe.[63] Likewise, censorship was generally only enforced by the republics rather than by the federal government, so it was quite common for an article to be banned in one republic while being allowed in other republics.[63] Starting in the early 1960s, Yugoslavs were permitted to travel to Western Europe without visas, and by the early 1960s, an average of 300,000 Yugoslavs visited Western Europe as tourists.[64] During the same period, it became common for Yugoslavs to go to Western Europe, especially West Germany, to work abroad as "guest workers".[64] By 1971, about 775,000 people (about 3.8% of the total Yugoslav population) were living abroad as "guest workers".[64] The remittances sent home by the "guest workers" led to a significant rise in the standard of living, and by the 1960s it became common for those whose family members were working abroad to own a car and electrical appliances such as a refrigerator.[64] The socialist regime championed women's rights and allowed equal legal rights to both legitimate and illegitimate children.[65] Abortion and birth control were both legal in Yugoslavia, which led to a rapid decline in population growth in 1960s-1970s.[65] Between 1948 and 1981, the population growth rate fell from 14.7% in 1947 to 7.4% in 1981.[66] In particular, the Communist regime attacked what it considered to be sexist traditions in the Muslim communities, banning polygamy, women being veiled and the "sale" of girls who were married off to the man best able to afford the bride-price.[67] An young Bosnian Muslim women stated: "Things used to be very different. Girls were not free...Today a girl can chose whom she wants to be with and where she wants to go...When I cut off my braids and got a permanent wave there was a lot of disapproval and gossip. I was one of the first girls in the village to stop wearing dimija [harem pants] and put on a dress...And today almost every girl has modern cloths in addition to her dimija".[67] The Partisan movement in the World War Two was very puritanical, which was carried on into the late 1940s and 1950s, but starting in the 1960s the regime embraced the values of the "permissive society" and the "sexual revolution".[56] In the 1960s, pornographic magazines were permitted and the Yugoslav newspapers devoted much coverage to gossip about the sex lives of celebrities, through not senior members of the League of Communists.[56] Likewise, the regime sought to encourage women to work and by 1964 about 29% of all Yugoslav women were working.[67] The female labor participation varied sharply from region to region. In Slovenia, 42% of all women were working in 1964 while in Kosovo region only 18% of women worked in 1964.[67] Western music was allowed in Yugoslavia, and music by groups popular in the West such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones was frequently played on Yugoslav radio.[68] Officially, Yugoslavia was neutral in the Cold War, but in a cultural sense, Yugoslavia belonged to the West as Western films, TV shows and music were all very popular in the 1960s.[68] Because of the low value of the dinar, Western films were often shot in Yugoslavia in the 1960s.[68] In the arts, a genre known as the "black wave" emerged in the 1960s that saw novels, plays and films that depicted modern Yugoslavia as corrupt and dehumanizing.[61] Several "black wave" works such as the novel Dad su cvetale tikve (When Pumpkins Blossomed) by Dragolav Milailović about his imprisonment at the Goli Otok camp in the early 1950s were banned, but others such as the novel Memoari Pere Bogaljia (Memoirs of Pera the Cripple) by Slobadan Selenić which depicted the League of Communist members as vulgar, corrupt and self-serving were awarded first prize at the Belgrade literary festival.[61]

In the early 1960s concern over problems such as the building of economically irrational "political" factories and inflation led a group within the Communist leadership to advocate greater decentralization.[69] These liberals were opposed by a group around Aleksandar Ranković.[70] Ranković as secret police chief was known as an advocate of an repressive line, especially against the Albanians of Kosovo, and tended to favor Serbs over the other peoples.[71] In 1966 the liberals (the most important being Edvard Kardelj, Vladimir Bakarić of Croatia and Petar Stambolić of Serbia) gained the support of Tito. At a party meeting in Brijuni, Ranković faced a fully prepared dossier of accusations and a denunciation from Tito that he had formed a clique with the intention of taking power. That year (1966), more than 3,700 Yugoslavs fled to Trieste[72] with the intention to seek political asylum in North America, United Kingdom or Australia. Ranković was forced to resign all party posts and some of his supporters were expelled from the party.[73] Throughout the 1950s and '60s, the economic development and liberalization continued at a rapid pace.[15][20] The introduction of further reforms introduced a variant of market socialism, which now entailed a policy of open borders. In 1965, most of the state controls on production, pricing and wages were ended and allowed small businesses to open, albeit with the proviso that no small enterprise could employ more than five people at a time.[74] Many of the older Communist leaders were uncomfortable with the "socialist market economy" that was being created, and were forced by Tito to take early retirement.[75] With heavy federal investment, tourism in SR Croatia was revived, expanded, and transformed into a major source of income. In particular, the 745-mile coastline of Dalmatia and Istria with its bright, sunny weather, beaches and more 1, 000 islands, and Italianate architecture became extremely popular with tourists in the 1960s.[76] In 1965, three million foreign tourists visited Dalmatia and by 1970 4.75 million foreign tourists came to visit Dalmatia.[76] Some of the other tourists came from Czechoslovakia and Hungary, but the majority came from Western Europe, especially from Italy, Austria and West Germany as the low value of the dinar made vacationing in Yugoslavia extremely cheap.[76] By 1969, the federal government made $275 million US dollars from tourism, which comprised some 10% of all revenue.[66] Dalmatia and Istria, which had once been poor regions, were almost overnight transformed into wealthy areas as about 30% of all people in Istria and Dalmatia were employed in the tourism industry by the end of the 1960s.[66]

With these successful measures, the Yugoslav economy achieved relative self-sufficiency and traded extensively with both the West and the East. By the early 1960s, foreign observers noted that the country was "booming", and that all the while the Yugoslav citizens enjoyed far greater liberties than the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc states.[77] Literacy was increased dramatically and reached 91%, medical care was free on all levels, and life expectancy was 72 years.[15][20][78] The German historian Marie-Janine Calic noted that the 1960s are remembered as the time of the "economic miracle" when living standards were rising for most Yugoslavs and the prosperity had "a politically pacifying and socially integrating effect".[79] Some of the republics became more wealthier than others. In 1965, Slovenia had an index value of 177.3% of Yugoslavia's per capital income, followed by Croatia at 120.7%, and Serbia at 94.9% while Bosnia-Herzegovina had 69.1% and the poorest region being Kosovo at 38.6%.[80] At least part of the reason for the regional differences was Tito's policy until 1965 of keeping the prices of raw materials and agricultural goods artificially low, which hurt the poorer republics in the south as most people there were employed in either agriculture or mining while Slovenia and Croatia were more industrialised.[80] To address the regional disparity, Tito created a regional development fund in 1965 intended to help the poorer republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Macedonia along with the Kosovo region of Serbia "catch up" with the richer republics to the north.[71]

In 1965, the Bosnian Muslims were upgraded to a sixth nationality, defined somewhat paradoxically as an ethnic rather than a religious group, and the 1971 census for the first time included the category "Muslim an ethnic sense".[81] The recognition of Bosnian Muslims as an ethnicity allowed for greater Muslim involvement in the politics of Bosnia with the numbers of Muslims on the Bosnian Central Committee raising from 19% of the membership in 1965 to 33% in 1974.[82] However, the recognition of Bosnian Muslims as an official nationality led to sharp disputes about whatever Bosnia-Herzegovina was the republic of the Muslims or if the Muslims were one of the three nations of Bosnia alongside the Serbs and the Croats.[82] The Croats and the Serbs tended to favor the "three nations" theory of Bosnia while the Muslims argued that the Serbs and the Croats already had their own republics and Bosnia was the special homeland of the Serbo-Croatian speaking Muslims.[82] On 2 June 1968, student demonstrations led to wider mass youth protests in capital cities across Yugoslavia. They were gradually stopped a week later by Tito on 9 June during his televised speech.[83] The student demonstrations of 1968 were an important turning point in Yugoslav history as for the first street protests had forced a change in policy, and in the coming decades, successive leaders within the League of Communists were to mobilize street protests as a way of forcing change.[83] In August 1968, Tito was opposed to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[84] The invasion of Czechoslovakia badly frightened Tito, whom believed that Yugoslavia would also soon be invaded by the Soviet Union.[85] In 1968–1969, Tito embarked upon major military reforms with the aim of preparing for the expected Soviet invasion.[85] Tito decided that the Yugoslav People's Army would stage a fighting retreat into the interior of the country and then revert over to guerrilla warfare, a doctrine Tito called "all-people's defense".[85] As part of the planned guerrilla war, Tito sought to enroll as much of the population into the military as possible.[85] The defense forces in 1969 were reorganized with 250, 000 professional soldiers of the People's Army along with 250, 000 reservists forming the core of the military and the territorial defense forces of the six republics, which collectively made up another 900, 000 men to serve as a nucleus of a guerilla force.[85] In the process, much of the population was armed and Tito in effect by creating the territorial defense forces on the republic level gave each republic its own army, which was later to play a major role in the break-up of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.[85] In October–November 1968, a series of riots erupted in Yugoslav Macedonia and the Kosovo region by Albanians who demanded that the regions where Albanians were a majority be turned into a new republic.[86] Some of the more radical Albanians called for the session of Kosovo and the Albanian regions of Macedonia to join Albania to form a greater Albania.[86] Tito rejected the demand for a 7th republic with an Albanian majority, but did grant demands for greater Albanian participation in public life.[86] In 1969, the University of Pristina was opened, becoming the first Albanian language university in Yugoslavia.[86] Likewise, Tito allowed for a greater number of Albanians to be recruited into the League of Communists and into the government, which in turn caused complaints from the Serbs that the Albanians were dominating the political life of Kosovo at their expense.[87]

In 1971 the leadership of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, notably Miko Tripalo and Savka Dabčević-Kučar, allied with nationalist non-party groups, began a movement to increase the powers of the individual federated republics. The movement was referred to as MASPOK, a portmanteau of masovni pokret meaning mass movement, and led to the Croatian Spring.[88] Tito responded to the incident by purging the League of Communists of Croatia, while Yugoslav authorities arrested large numbers of the Croatian protesters. To avert ethnically driven protests in the future, Tito began to initiate some of the reforms demanded by the protesters.[89] At this time, Ustaše-sympathizers outside Yugoslavia tried through terrorism and guerrilla actions to create a separatist momentum,[90] but they were unsuccessful, sometimes even gaining the animosity of fellow Roman Catholic Croatian Yugoslavs.[91] From 1971 on, the republics had control over their economic plans. This led to a wave of investment, which in turn was accompanied by a growing level of debt and a growing trend of imports not covered by exports.[92] After the "Croatian Spring", Tito turned towards a more repressive leadership style, bringing in a new law in 1973 that restricted media freedom.[93] By 1975, Yugoslavia had 4, 000 political prisoners, a figure that was only exceeded in Europe by Albania and the Soviet Union.[94] The journal Praxis, which was the main organ of criticism of the regime was shut down while a number of the "Black Wave" films were banned.[94] The 1973-1974 oil shock badly hurt the Yugoslav economy as Yugoslavia had no oil of its own while the global recession sharply decreased the demand for raw materials and manufactured goods from Yugoslavia.[95] To compensate, Yugoslavia went on a spree of borrowing money, creating an illusion of prosperity as the 1970s saw the greatest period of construction as thousands of new hotels, sports arenas, libraries, and streets were built that decade.[96] The average annual economic rate after the 1973-1974 oil shock crisis was 8%, but the growth was largely fueled with money borrowed from the West.[97]

Many of the demands made in the Croatian Spring movement in 1971, such as giving more autonomy to the individual republics, became reality with the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution. While the constitution gave the republics more autonomy, it also awarded a similar status to two autonomous provinces within Serbia: Kosovo, a largely ethnic Albanian populated region, and Vojvodina, a region with Serb majority but large numbers of ethnic minorities, such as Hungarians. These reforms satisfied most of the republics, especially Croatia and the Albanians of Kosovo and the minorities of Vojvodina. But the 1974 constitution deeply aggravated Serbian Communist officials and Serbs themselves who distrusted the motives of the proponents of the reforms. Many Serbs saw the reforms as concessions to Croatian and Albanian nationalists, as no similar autonomous provinces were made to represent the large numbers of Serbs of Croatia or Bosnia and Herzegovina. Serb nationalists were frustrated over Tito's support for the recognition of Montenegrins and Macedonians as independent nationalities, as Serbian nationalists had claimed that there was no ethnic or cultural difference separating these two nations from the Serbs that could verify that such nationalities truly existed. Tito maintained a busy, active travelling schedule despite his advancing age. His 85th birthday in May 1977 was marked by huge celebrations. That year, he visited Libya, the Soviet Union, North Korea and finally China, where the post-Mao leadership finally made peace with him after more than 20 years of denouncing the SFRY as "revisionists in the pay of capitalism". This was followed by a tour of France, Portugal, and Algeria after which the president's doctors advised him to rest. In August 1978, Chinese leader Hua Guofeng visited Belgrade, reciprocating Tito's China trip the year before. This event was sharply criticized in the Soviet press, especially as Tito used it as an excuse to indirectly attack Moscow's ally Cuba for "promoting divisiveness in the Non-Aligned Movement". When China launched a military campaign against Vietnam the following February, Yugoslavia openly took Beijing's side in the dispute. The effect was a rather adverse decline in Soviet Union-Yugoslavia relations. During this time, Yugoslavia's first nuclear reactor was under construction in Krško, built by US-based Westinghouse. The project ultimately took until 1980 to complete because of disputes with the United States about certain guarantees that Belgrade had to sign off on before it could receive nuclear materials (which included the promise that they would not be sold to third parties or used for anything but peaceful purposes).

In 1979, seven selection criteria comprising Ohrid, Dubrovnik, Split, Plitvice Lakes National Park, Kotor, Stari Ras and Sopoćani were designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, making it the first inscription of cultural and natural landmarks in Yugoslavia.

Post-Tito period

[edit]

Tito died on 4 May 1980 due to complications after surgery. While it had been known for some time that the 87-year-old president's health had been failing, his death nonetheless came as a shock to the country. This was because Tito was looked upon as the country's hero in World War II and had been the country's dominant figure and identity for over three decades. His loss marked a significant alteration, and it was reported that many Yugoslavs openly mourned his death. In the Split soccer stadium, Serbs and Croats visited the coffin among other spontaneous outpourings of grief, and a funeral was organized by the League of Communists with hundreds of world leaders in attendance (See Tito's state funeral).[98] After Tito's death in 1980, a new collective presidency of the Communist leadership from each republic was adopted. At the time of Tito's death the Federal government was headed by Veselin Đuranović (who had held the post since 1977). He had come into conflict with the leaders of the republics, arguing that Yugoslavia needed to economize due to the growing problem of foreign debt. Đuranović argued that a devaluation was needed which Tito refused to countenance for reasons of national prestige.[99][page needed] Post-Tito Yugoslavia faced significant fiscal debt in the 1980s, but its good relations with the United States led to an American-led group of organizations called the "Friends of Yugoslavia" to endorse and achieve significant debt relief for Yugoslavia in 1983 and 1984, though economic problems would continue until the state's dissolution in the 1990s.[100] Yugoslavia was the host nation of the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. For Yugoslavia, the games demonstrated Tito's continued vision of Brotherhood and Unity, as the multiple nationalities of Yugoslavia remained united in one team, and Yugoslavia became the second Communist state to hold the Olympic Games (the Soviet Union held them in 1980). However, Yugoslavia's games had Western countries participating, while the Soviet Union's Olympics were boycotted by some. In the late 1980s, the Yugoslav government began to deviate from communism as it attempted to transform to a market economy under the leadership of Prime Minister Ante Marković, who advocated shock therapy tactics to privatize sections of the Yugoslav economy. Marković was popular, as he was seen as the most capable politician to be able to transform the country to a liberalized democratic federation, though he later lost his popularity, mainly due to rising unemployment. His work was left incomplete as Yugoslavia broke apart in the 1990s.

Dissolution and war

[edit]After a period of political and economic crisis in the 1980s, the constituent republics of Yugoslavia split apart in the early 1990s. Unresolved issues from the breakup caused a series of inter-ethnic Yugoslav Wars from 1991 to 2001 which primarily affected Bosnia and Herzegovina, neighbouring parts of Croatia and, some years later, Kosovo.

Following the Allied victory in World War II, Yugoslavia was set up as a federation of six republics, with borders drawn along ethnic and historical lines: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. In addition, two autonomous provinces were established within Serbia: Vojvodina and Kosovo. Each of the republics had its own branch of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia party and a ruling elite, and any tensions were solved on the federal level. The Yugoslav model of state organisation, as well as a "middle way" between planned and liberal economy, had been a relative success, and the country experienced a period of strong economic growth and relative political stability up to the 1980s, under Josip Broz Tito.[101] After his death in 1980, the weakened system of federal government was left unable to cope with rising economic and political challenges.

In the 1980s, Kosovo Albanians started to demand that their autonomous province be granted the status of a full constituent republic, starting with the 1981 protests. Ethnic tensions between Albanians and Kosovo Serbs remained high over the whole decade, which resulted in the growth of Serb opposition to the high autonomy of provinces and ineffective system of consensus at the federal level across Yugoslavia, which were seen as an obstacle for Serb interests. In 1987, Slobodan Milošević came to power in Serbia, and through a series of populist moves acquired de facto control over Kosovo, Vojvodina, and Montenegro, garnering a high level of support among Serbs for his centralist policies. Milošević was met with opposition by party leaders of the western constituent republics of Slovenia and Croatia, who also advocated greater democratisation of the country in line with the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe. The League of Communists of Yugoslavia dissolved in January 1990 along federal lines. Republican communist organisations became the separate socialist parties.

During 1990, the socialists (former communists) lost power to ethnic separatist parties in the first multi-party elections held across the country, except in Montenegro and in Serbia, where Milošević and his allies won. Nationalist rhetoric on all sides became increasingly heated. Between June 1991 and April 1992, four constituent republics declared independence while Montenegro and Serbia remained federated. Germany took the initiative and recognized the independence of Croatia and Slovenia, but the status of ethnic Serbs outside Serbia and Montenegro, and that of ethnic Croats outside Croatia, remained unsolved. After a string of inter-ethnic incidents, the Yugoslav Wars ensued, with the most severe conflicts being in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo. The wars left economic and political damage in the region that is still felt decades later.[102] On April 27, 1992, the Federal Council of the Assembly of the SFRY, based on the decision of the Assembly of the Republic of Serbia and the Assembly of Montenegro, adopted the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which formally ended the breakup. The SFR Yugoslavia had, de facto, dissolved into five successor states: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Slovenia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (later renamed "Serbia and Montenegro"). The Badinter Commission later (1991–93) noted that Yugoslavia disintegrated into several independent states, so it is not possible to talk about the secession of Slovenia and Croatia from Yugoslavia.[11]

Post-1992 UN membership

[edit]In September 1992, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (consisting of Serbia and Montenegro) failed to achieve de jure recognition as the continuation of the Socialist Federal Republic in the United Nations. It was separately recognised as a successor alongside Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia. Before 2000, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia declined to re-apply for membership in the United Nations and the United Nations Secretariat allowed the mission from the SFRY to continue to operate and accredited representatives of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to the SFRY mission, continuing work in various United Nations organs.[103] It was only after the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević, that the government of FR Yugoslavia applied for UN membership in 2000.

Governance

[edit]Constitution

[edit]

The first Yugoslav Constitution was adopted in 1946 and amended in 1953. The second one was adopted in 1963 and the third in 1974.[104] The League of Communists of Yugoslavia won the first elections, and remained in power throughout the state's existence. It was composed of individual Communist parties from each constituent republic. The party would reform its political positions through party congresses in which delegates from each republic were represented and voted on changes to party policy, the last of which was held in 1990. Yugoslavia's parliament was known as the Federal Assembly which was housed in the building which currently houses Serbia's parliament. The Federal Assembly was composed entirely of Communist members. The primary political leader of the state was Josip Broz Tito, but there were several other important politicians, particularly after Tito's death.

In 1974, Tito was elected President-for-life of Yugoslavia.[105] After Tito's death in 1980, the single position of president was divided into a collective Presidency, where representatives of each republic would essentially form a committee where the concerns of each republic would be addressed and from it, collective federal policy goals and objectives would be implemented. The head of the collective presidency was rotated between representatives of the republics. The collective presidency was considered the head of state of Yugoslavia. The collective presidency was ended in 1991, as Yugoslavia fell apart. In 1974, major reforms to Yugoslavia's constitution occurred. Among the changes was the controversial internal division of Serbia, which created two autonomous provinces within it, Vojvodina and Kosovo. Each of these autonomous provinces had voting power equal to that of the republics, and were represented in the Serbian assembly.[106]

Women's rights policy

[edit]The 1946 Yugoslav Constitution aimed to unify family law throughout Yugoslavia and to overcome discriminatory provisions, particularly concerning economic rights, inheritance, child custody and the birth of 'illegitimate' children. Article 24 of the Constitution affirmed the equality of women in society, stating that: "Women have equal rights with men in all areas of state, economic and socio-political life."[107]

At the end of the 1940s, the Women's Antifascist Front of Yugoslavia (AFŽ), an organization founded during the Resistance to involve women in politics, was tasked with implementing a socialist policy for the emancipation of women, targeting in particular the most backward rural areas. AFŽ activists were immediately confronted with the gap between officially proclaimed rights and women's daily lives. The reports drawn up by local AFŽ sections in the late 1940s and 1950s testify to the extent of patriarchal domination, physical exploitation and poor access to education faced by the majority of women, particularly in the countryside.[107]

AFŽ also led a campaign against the full veil, which covered the whole body and face, until it was banned in the 1950s.[107]

By the 1970s, thirty years after women's rights were enshrined in the Yugoslav Constitution, the country had undergone a rapid process of modernisation and urbanisation. Women's literacy and access to the labour market had reached unprecedented levels, and inequalities in women's rights had been considerably reduced compared to the inter-war period. Yet full equality was far from being achieved.[107]

Federal units

[edit]Internally, the Yugoslav federation was divided into six constituent states. Their formation was initiated during the war years, and finalized in 1944–1946. They were initially designated as federated states, but after the adoption of the first federal Constitution, on 31 January 1946, they were officially named people's republics (1946–1963), and later socialist republics (from 1963 forward). They were constitutionally defined as mutually equal in rights and duties within the federation. Initially, there were initiatives to create several autonomous units within some federal units, but that was enforced only in Serbia, where two autonomous units (Vojvodina and Kosovo) were created (1945).[108][99]

In alphabetical order, the republics and provinces were:

| Name | Capital | Flag | Coat of arms | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina | Sarajevo | |||

| Socialist Republic of Croatia | Zagreb | |||

| Socialist Republic of Macedonia | Skopje | |||

| Socialist Republic of Montenegro | Titograd (now Podgorica) | |||

| Socialist Republic of Serbia | Belgrade | |||

| Socialist Republic of Slovenia | Ljubljana |

Foreign policy

[edit]

Under Tito, Yugoslavia adopted a policy of nonalignment in the Cold War. It developed close relations with developing countries by having a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement, as well as maintaining cordial relations with the United States and Western European countries. Stalin considered Tito a traitor and openly offered condemnation towards him. Yugoslavia provided major assistance to anti-colonialist movements in the Third World. The Yugoslav delegation was the first to bring the demands of the Algerian National Liberation Front to the United Nations. In January 1958, the French Navy boarded the Slovenija cargo ship off Oran, whose holds were filled with weapons for the insurgents. Diplomat Danilo Milic explained that "Tito and the leading nucleus of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia really saw in the Third World's liberation struggles a replica of their own struggle against the fascist occupants. They vibrated to the rhythm of the advances or setbacks of the FLN or Vietcong."[109] Thousands of Yugoslav military advisors travelled to Guinea after its decolonisation and as the French government tried to destabilise the country. Tito also covertly helped left-wing nationalist movements to destabilize the Portuguese colonial empire. Tito saw the murder of Patrice Lumumba by Belgian-backed Katangan separatists in 1961 as the "greatest crime in contemporary history". Yugoslavia's military academies trained left-wing activists from both Swapo (modern Namibia) and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania as part of Tito's efforts to destabilize South Africa under apartheid. In 1980, the intelligence services of South Africa and Argentina plotted to return the favor by covertly bringing 1,500 anti-communist urban guerrillas to Yugoslavia. The operation was aimed at overthrowing Tito and was planned during the Olympic Games period so that the Soviets would be too busy to react. The operation was finally abandoned due to Tito's death and the Yugoslav armed forces raising their alert level.[109]

After World War II, Yugoslavia became a leader in international tourism among socialist states, motivated by both ideological and financial purposes. In the 1960s, many foreigners were able to get a visa on arrival and, later onward, were issued a tourist card for short stays. Numerous reciprocal agreements for abolishing visas were implemented with other countries (mainly Western European), through the decade. For the International Year of Tourism in 1967 Yugoslavia suspended visa requirements for all countries it had diplomatic relations with.[110][111] In the same year, Tito became active in promoting a peaceful resolution of the Arab–Israeli conflict. His plan called for Arab countries to recognize the State of Israel in exchange for Israel returning territories it had gained.[112] The Arab countries rejected his land for peace concept.[citation needed] However, that same year, Yugoslavia no longer recognized Israel.[citation needed]

In 1968, following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Tito added an additional defense line to Yugoslavia's borders with the Warsaw Pact countries.[113] Later in 1968, Tito then offered Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubček that he would fly to Prague on three hours notice if Dubček needed help in facing down the Soviet Union which was occupying Czechoslovakia at the time.[114]

Yugoslavia had mixed relations towards Enver Hoxha's Albania. Initially Yugoslav-Albanian relations were forthcoming, as Albania adopted a common market with Yugoslavia and required the teaching of Serbo-Croatian to students in high schools.[citation needed] At this time, the concept of creating a Balkan Federation was being discussed between Yugoslavia, Albania and Bulgaria.[citation needed] Albania at this time was heavily dependent on economic support of Yugoslavia to fund its initially weak infrastructure. Trouble between Yugoslavia and Albania began when Albanians began to complain that Yugoslavia was paying too little for Albania's natural resources.[citation needed] Afterward, relations between Yugoslavia and Albania worsened. From 1948 onward, the Soviet Union backed Albania in opposition to Yugoslavia. On the issue of Albanian-populated Kosovo, Yugoslavia and Albania both attempted to neutralize the threat of nationalist conflict, Hoxha opposed Albanian nationalism, as he officially believed in the world communist ideal of international brotherhood of all people, though on a few occasions in the 1980s he made inflammatory speeches in support of Albanians in Kosovo against the Yugoslav government, when public sentiment in Albania was firmly in support of Kosovo's Albanians.[citation needed]

Military

[edit]