Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aramaic alphabet

View on Wikipedia

| Aramaic alphabet | |

|---|---|

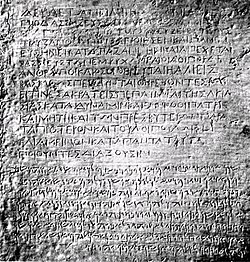

Aramaic inscription from Tayma, containing a dedicatory inscription to the god Salm | |

| Script type | |

Period | 800 BC to AD 600 |

| Direction | Right-to-left |

| Languages | Aramaic (Syriac[1] and Mandaic), Hebrew, Edomite |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Armi (124), Imperial Aramaic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Imperial Aramaic |

| U+10840–U+1085F | |

| Arameans |

|---|

| Syro-Hittite states |

| Aramean kings |

| Aramean cities |

| Sources |

The ancient Aramaic alphabet was used to write the Aramaic languages spoken by ancient Aramean pre-Christian peoples throughout the Fertile Crescent. It was also adopted by other peoples as their own alphabet when empires and their subjects underwent linguistic Aramaization during a language shift for governing purposes — a precursor to Arabization centuries later — including among the Assyrians and Babylonians who permanently replaced their Akkadian language and its cuneiform script with Aramaic and its script, and among Jews, but not Samaritans, who adopted the Aramaic language as their vernacular and started using the Aramaic alphabet, which they call "Square Script", even for writing Hebrew, displacing the former Paleo-Hebrew alphabet. The modern Hebrew alphabet derives from the Aramaic alphabet, in contrast to the modern Samaritan alphabet, which derives from Paleo-Hebrew.

The letters in the Aramaic alphabet all represent consonants, some of which are also used as matres lectionis to indicate long vowels. Writing systems, like the Aramaic, that indicate consonants but do not indicate most vowels other than by means of matres lectionis or added diacritical signs, have been called abjads by Peter T. Daniels to distinguish them from alphabets such as the Greek alphabet, that represent vowels more systematically. The term was coined to avoid the notion that a writing system that represents sounds must be either a syllabary or an alphabet, which would imply that a system like Aramaic must be either a syllabary, as argued by Ignace Gelb, or an incomplete or deficient alphabet, as most other writers had said before Daniels. Daniels put forward, this is a different type of writing system, intermediate between syllabaries and 'full' alphabets.

The Aramaic alphabet is historically significant since virtually all modern Middle Eastern writing systems can be traced back to it. That is primarily due to the widespread usage of the Aramaic language after it was adopted as both a lingua franca and the official language of the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Empires, and their successor, the Achaemenid Empire. Among the descendant scripts in modern use, the Jewish Hebrew alphabet bears the closest relation to the Imperial Aramaic script of the 5th century BC, with an identical letter inventory and, for the most part, nearly identical letter shapes. By contrast the Samaritan Hebrew script is directly descended from Proto-Hebrew/Phoenician script, which was the ancestor of the Aramaic alphabet. The Aramaic alphabet was also an ancestor to the Syriac alphabet and Mongolian script and Kharosthi[2] and Brahmi,[3] and Nabataean alphabet, which had the Arabic alphabet as a descendant.

History

[edit]

The earliest inscriptions in the Aramaic language use the Phoenician alphabet.[4] Over time, the alphabet developed into the Aramaic alphabet by the 8th century BC. It was used to write the Aramaic languages spoken by ancient Aramean pre-Christian tribes throughout the Fertile Crescent. It was also adopted by other peoples as their own alphabet when empires and their subjects underwent linguistic Aramaization during a language shift for governing purposes — a precursor to Arabization centuries later.

These include the Assyrians and Babylonians, who permanently replaced their Akkadian language and its cuneiform script with Aramaic and its script, and among Jews, but not Samaritans, who adopted the Aramaic language as their vernacular and started using the Aramaic alphabet even for writing Hebrew, displacing the former Paleo-Hebrew alphabet. The modern Hebrew alphabet derives from the Aramaic alphabet, in contrast to the modern Samaritan alphabet, which derives from Paleo-Hebrew.

Achaemenid Empire (The First Persian Empire)

[edit]

Around 500 BC, following the Achaemenid conquest of Mesopotamia under Darius I, Old Aramaic was adopted by the Persians as the "vehicle for written communication between the different regions of the vast Persian empire with its different peoples and languages. The use of a single official language, which modern scholarship has dubbed as Official Aramaic, Imperial Aramaic or Achaemenid Aramaic, can be assumed to have greatly contributed to the astonishing success of the Achaemenid Persians in holding their far-flung empire together for as long as they did."[5]

Imperial Aramaic was highly standardised. Its orthography was based more on historical roots than any spoken dialect and was influenced by Old Persian. The Aramaic glyph forms of the period are often divided into two main styles, the "lapidary" form, usually inscribed on hard surfaces like stone monuments, and a cursive form whose lapidary form tended to be more conservative by remaining more visually similar to Phoenician and early Aramaic. Both were in use through the Achaemenid Persian period, but the cursive form steadily gained ground over the lapidary, which had largely disappeared by the 3rd century BC.[6]

For centuries after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire in 331 BC, Imperial Aramaic, or something near enough to it to be recognisable, remained an influence on the various native Iranian languages. The Aramaic script survived as the essential characteristics of the Iranian Pahlavi writing system.[7]

30 Aramaic documents from Bactria have been recently discovered, an analysis of which was published in November 2006. The texts, which were rendered on leather, reflect the use of Aramaic in the 4th century BC, in the Persian Achaemenid administration of Bactria and Sogdiana.[8]

The widespread usage of Achaemenid Aramaic in the Middle East led to the gradual adoption of the Aramaic alphabet for writing Hebrew. Formerly, Hebrew had been written using an alphabet closer in form to that of Phoenician, the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet.[9]

Aramaic-derived scripts

[edit]Since the evolution of the Aramaic alphabet out of the Phoenician one was a gradual process, the division of the world's alphabets into the ones derived from the Phoenician one directly, and the ones derived from Phoenician via Aramaic, is somewhat artificial. In general, the alphabets of the Mediterranean region (Anatolia, Greece, Italy) are classified as Phoenician-derived, adapted from around the 8th century BC. Those of the East (the Levant, Persia, Central Asia, and India) are considered Aramaic-derived, adapted from around the 6th century BC from the Imperial Aramaic script of the Achaemenid Empire.[citation needed]

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, the unity of the Imperial Aramaic script was lost, diversifying into a number of descendant cursives.

The Hebrew and Nabataean alphabets, as they stood by the Roman era, were little changed in style from the Imperial Aramaic alphabet. Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) alleges that not only the old Nabataean writing was influenced by the "Syrian script" (i.e. Aramaic), but also the old Chaldean script.[10]

A cursive Hebrew variant developed from the early centuries AD. It remained restricted to the status of a variant used alongside the noncursive. By contrast, the cursive developed out of the Nabataean alphabet in the same period soon became the standard for writing Arabic, evolving into the Arabic alphabet as it stood by the time of the early spread of Islam.

The development of cursive versions of Aramaic led to the creation of the Syriac, Palmyrene and Mandaic alphabets, which formed the basis of the historical scripts of Central Asia, such as the Sogdian and Mongolian alphabets.[11]

The Old Turkic script is generally considered to have its ultimate origins in Aramaic,[12][13][11] in particular via the Pahlavi or Sogdian alphabets,[14][15] as suggested by V. Thomsen, or possibly via Kharosthi (cf., Issyk inscription).

Brahmi script was also possibly derived or inspired by Aramaic. Brahmic family of scripts includes Devanagari.[16]

Languages using the alphabet

[edit]Today, Biblical Aramaic, Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialects and the Aramaic language of the Talmud are written in the modern-Hebrew alphabet, distinguished from the Old Hebrew script. In classical Jewish literature, the name given to the modern-Hebrew script was "Ashurit", the ancient Assyrian script,[17] a script now known widely as the Aramaic script.[18][19] It is believed that, during the period of Assyrian dominion, Aramaic script and language received official status.[18]

Syriac and Christian Neo-Aramaic dialects are today written in the Syriac alphabet, which script has superseded the more ancient Assyrian script and now bears its name. Mandaic is written in the Mandaic alphabet. The near-identical nature of the Aramaic and the classical Hebrew alphabets caused Aramaic text to be typeset mostly in the standard Hebrew script in scholarly literature.

Maaloula

[edit]In Maaloula, one of few surviving communities in which a Western Aramaic dialect is still spoken, an Aramaic Language Institute was established in 2006 by Damascus University that teaches courses to keep the language alive.

Unlike Classical Syriac, which has a rich literary tradition in Syriac-Aramaic script, Western Neo-Aramaic was solely passed down orally for generations until 2006 and was not utilized in a written form.[20]

Therefore, the Language Institute's chairman, George Rizkalla (Rezkallah), undertook the writing of a textbook in Western Neo-Aramaic. Being previously unwritten, Rizkalla opted for the Hebrew alphabet. In 2010, the institute's activities were halted due to concerns that the square Maalouli-Aramaic alphabet used in the program bore a resemblance to the square script of the Hebrew alphabet. As a result, all signs featuring the square Maalouli script were subsequently removed.[21] The program stated that they would instead use the more distinct Syriac-Aramaic alphabet, although use of the Maalouli alphabet has continued to some degree.[22] Al Jazeera Arabic also broadcast a program about Western Neo-Aramaic and the villages in which it is spoken with the square script still in use.[23]

Letters

[edit]| Letter name | Aramaic written using | IPA | Phoneme | Equivalent letter in | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial Aramaic | Syriac script | Hebrew | Maalouli | Nabataean | Parthian | Arabic | South Arabian | Geʽez | Proto-Sinaitic | Phoenician | Greek | Latin | Cyrillic | Brahmi | Kharosthi | Turkic | |||||

| Image | Text | Image | Text | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ālaph | 𐡀 | ܐ | /ʔ/; /aː/, /eː/ | ʾ | א | 𐭀 | ا | 𐩱 | አ | 𐤀 | Αα | Aa | Аа | 𐰁 | |||||||

| Bēth | 𐡁 | ܒ | /b/, /v/ | b | ב | 𐭁 | ب | 𐩨 | በ | 𐤁 | Ββ | Bb | Бб, Вв | 𐰉 𐰋 | |||||||

| Gāmal | 𐡂 | ܓ | /ɡ/, /ɣ/ | g | ג | 𐭂 | ج | 𐩴 | ገ | 𐤂 | Γγ | Cc, Gg | Гг, Ґґ | 𐰲 𐰱 | |||||||

| Dālath | 𐡃 | ܕ | /d/, /ð/ | d | ד | 𐭃 | د ذ | 𐩵 | ደ | 𐤃 | Δδ | Dd | Дд | 𐰓 | |||||||

| Hē | 𐡄 | ܗ | /h/ | h | ה | 𐭄 | ه | 𐩠 | ሀ | 𐤄 | Εε | Ee | Ее, Ёё, Єє, Ээ | ||||||||

| Waw | 𐡅 | ܘ | /w/; /oː/, /uː/ | w | ו | 𐭅 | و | 𐩥 | ወ | 𐤅 | (Ϝϝ), Υυ | Ff, Uu, Vv, Ww, Yy | Ѵѵ, Уу, Ўў | 𐰈 𐰆 | |||||||

| Zayn | 𐡆 | ܙ | /z/ | z | ז | 𐭆 | ز | 𐩸 | 𐤆 | Ζζ | Zz | Зз | 𐰕 | ||||||||

| Ḥēth | 𐡇 | ܚ | /ħ/ | ḥ | ח | 𐭇 | ح خ | 𐩢 | ሐ | 𐤇 | Ηη | Hh | Ии, Йй | ||||||||

| Ṭēth | 𐡈 | ܛ | /tˤ/ | ṭ | ט | 𐭈 | ط ظ | 𐩷 | ጠ | 𐤈 | Θθ | Ѳѳ | 𐱃 | ||||||||

| Yodh | 𐡉 | ܝ | /j/; /iː/, /eː/ | y | י | 𐭉 | ي | 𐩺 | የ | 𐤉 | Ιι | Ιi, Jj | Іі, Її, Јј | 𐰘 𐰃 𐰖 | |||||||

| Kāph | 𐡊 | ܟ | /k/, /x/ | k | כ ך | 𐭊 | ك | 𐩫 | ከ | 𐤊 | Κκ | Kk | Кк | 𐰚 𐰜 | |||||||

| Lāmadh | 𐡋 | ܠ | /l/ | l | ל | 𐭋 | ل | 𐩡 | ለ | 𐤋 | Λλ | Ll | Лл | 𐰞 𐰠 | |||||||

| Mim | 𐡌 | ܡ | /m/ | m | מ ם | 𐭌 | م | 𐩣 | መ | 𐤌 | Μμ | Mm | Мм | 𐰢 | |||||||

| Nun | 𐡍 | ܢ | /n/ | n | נ ן | 𐭍 | ن | 𐩬 | ነ | 𐤍 | Νν | Nn | Нн | 𐰤 𐰣 | |||||||

| Semkath | 𐡎 | ܣ | /s/ | s | ס | 𐭎 | س | 𐩯 | 𐤎 | Ξξ | Ѯѯ | 𐰾 | |||||||||

| ʿAyn | 𐡏 | ܥ | /ʕ/ | ʿ | ע | 𐭏 | ع غ | 𐩲 | ዐ | 𐤏 | Οο, Ωω | Oo | Оо, Ѡѡ | 𐰏 𐰍 | |||||||

| Pē | 𐡐 | ܦ | /p/, /f/ | p | פ ף | 𐭐 | ف | 𐩰 | ፈ | 𐤐 | Ππ | Pp | Пп | 𐰯 | |||||||

| Ṣādhē | 𐡑 | ܨ | /sˤ/ | ṣ | צ ץ | 𐭑 | ص ض | 𐩮 | ጸ | 𐤑 | (Ϻϻ) | Цц, Чч, Џџ | 𐰽 | ||||||||

| Qoph | 𐡒 | ܩ | /q/ | q | ק | 𐭒 | ق | 𐩤 | ቀ | 𐤒 | (Ϙϙ), Φφ | Ҁҁ, Фф | 𐰴 𐰸 | ||||||||

| Rēš | 𐡓 | ܪ | /r/ | r | ר | 𐭓 | ر | 𐩧 | ረ | 𐤓 | Ρρ | Rr | Рр | 𐰺 𐰼 | |||||||

| Šin | 𐡔 | ܫ | /ʃ/ | š | ש | 𐭔 | ش | 𐩦 | ሠ | 𐤔 | Σσς | Ss | Сс, Шш, Щщ | 𐱂 𐱁 | |||||||

| Taw | 𐡕 | ܬ | /t/, /θ/ | t | ת | 𐭕 | ت ث | 𐩩 | ተ | 𐤕 | Ττ | Tt | Тт | 𐱅 | |||||||

Unicode

[edit]The Imperial Aramaic alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009, with the release of version 5.2.

The Unicode block for Imperial Aramaic is U+10840–U+1085F:

| Imperial Aramaic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1084x | 𐡀 | 𐡁 | 𐡂 | 𐡃 | 𐡄 | 𐡅 | 𐡆 | 𐡇 | 𐡈 | 𐡉 | 𐡊 | 𐡋 | 𐡌 | 𐡍 | 𐡎 | 𐡏 |

| U+1085x | 𐡐 | 𐡑 | 𐡒 | 𐡓 | 𐡔 | 𐡕 | 𐡗 | 𐡘 | 𐡙 | 𐡚 | 𐡛 | 𐡜 | 𐡝 | 𐡞 | 𐡟 | |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Syriac Aramaic alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in September 1999, with the release of version 3.0.

The Syriac Abbreviation (a type of overline) can be represented with a special control character called the Syriac Abbreviation Mark (U+070F). The Unicode block for Syriac Aramaic is U+0700–U+074F:

| Syriac[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+070x | ܀ | ܁ | ܂ | ܃ | ܄ | ܅ | ܆ | ܇ | ܈ | ܉ | ܊ | ܋ | ܌ | ܍ | SAM | |

| U+071x | ܐ | ܑ | ܒ | ܓ | ܔ | ܕ | ܖ | ܗ | ܘ | ܙ | ܚ | ܛ | ܜ | ܝ | ܞ | ܟ |

| U+072x | ܠ | ܡ | ܢ | ܣ | ܤ | ܥ | ܦ | ܧ | ܨ | ܩ | ܪ | ܫ | ܬ | ܭ | ܮ | ܯ |

| U+073x | ܰ | ܱ | ܲ | ܳ | ܴ | ܵ | ܶ | ܷ | ܸ | ܹ | ܺ | ܻ | ܼ | ܽ | ܾ | ܿ |

| U+074x | ݀ | ݁ | ݂ | ݃ | ݄ | ݅ | ݆ | ݇ | ݈ | ݉ | ݊ | ݍ | ݎ | ݏ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 89. ISBN 978-0195079937.

- ^ "Kharoshti | Indo-Parthian, Brahmi Script, Prakrit | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Brahmi | Ancient Script, India, Devanagari, & Dravidian Languages | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 6 September 2024. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ Inland Syria and the East-of-Jordan Region in the First Millennium BCE before the Assyrian Intrusions, Mark W. Chavalas, The Age of Solomon: Scholarship at the Turn of the Millennium, ed. Lowell K. Handy, (Brill, 1997), 169.

- ^ Shaked, Saul (1987). "Aramaic". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 250–261. p. 251

- ^ Greenfield, J.C. (1985). "Aramaic in the Achaemenid Empire". In Gershevitch, I. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran: Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 709–710.

- ^ Geiger, Wilhelm; Kuhn, Ernst (2002). Grundriss der iranischen Philologie: Band I. Abteilung 1. Boston: Adamant. pp. 249ff.

- ^ Naveh, Joseph; Shaked, Shaul (2006). Ancient Aramaic Documents from Bactria. Studies in the Khalili Collection. Oxford: Khalili Collections. ISBN 978-1-874780-74-8.

- ^ Thamis (18 January 2012). "The Phoenician Alphabet & Language". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- ^ Ibn Khaldun (1958). F. Rosenthal (ed.). The Muqaddimah (K. Ta'rikh – "History"). Vol. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. p. 283. OCLC 643885643.

- ^ a b Kara, György (1996). "Aramaic Scripts for Altaic Languages". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 535–558. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^ Babylonian beginnings: The origin of the cuneiform writing system in comparative perspective, Jerold S. Cooper, The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, ed. Stephen D. Houston, (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 58–59.

- ^ Tristan James Mabry, Nationalism, Language, and Muslim Exceptionalism, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 109.

- ^ Turks, A. Samoylovitch, First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936, Vol. VI, (Brill, 1993), 911.

- ^ George L. Campbell and Christopher Moseley, The Routledge Handbook of Scripts and Alphabets, (Routledge, 2012), 40.

- ^ "Brāhmī | writing system". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Danby, H., ed. (1964). "Tractate Megillah 1:8". Mishnah. London: Oxford University Press. p. 202 (note 20). OCLC 977686730. (The Mishnah, p. 202 (note 20)).

- ^ a b Steiner, R.C. (1993). "Why the Aramaic Script Was Called "Assyrian" in Hebrew, Greek, and Demotic". Orientalia. 62 (2): 80–82. JSTOR 43076090.

- ^ Cook, Stanley A. (1915). "The Significance of the Elephantine Papyri for the History of Hebrew Religion". The American Journal of Theology. 19 (3). The University of Chicago Press: 348. doi:10.1086/479556. JSTOR 3155577.

- ^ Oriens Christianus (in German). 2003. p. 77.

As the villages are very small, located close to each other, and the three dialects are mutually intelligible, there has never been the creation of a script or a standard language. Aramaic is the unwritten village dialect...

- ^ Maissun Melhem. "Schriftenstreit in Syrien" (in German). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

Before the Islamic conquest, Aramaic was spoken throughout Syria and was a global language. There were many variants, but Aramaic did not exist as a written language everywhere, including the Ma'alula region, notes Professor Jastrow. The decision to use the Hebrew script, in his opinion, was made arbitrarily."

- ^ Beach, Alastair (2 April 2010). "Easter Sunday: A Syrian bid to resurrect Aramaic, the language of Jesus Christ". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ Al Jazeera Documentary الجزيرة الوثائقية (11 February 2016). "أرض تحكي لغة المسيح". Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2018 – via YouTube.

Sources

[edit]- Byrne, Ryan. "Middle Aramaic Scripts". Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier. (2006)

- Daniels, Peter T., et al. eds. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford. (1996)

- Coulmas, Florian. The Writing Systems of the World. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford. (1989)

- Rudder, Joshua. Learn to Write Aramaic: A Step-by-Step Approach to the Historical & Modern Scripts. n.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011. 220 pp. ISBN 978-1461021421. Includes a wide variety of Aramaic scripts.

- Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic on Coins, reading and transliterating Proto-Hebrew, online edition (Judaea Coin Archive).

External links

[edit]Aramaic alphabet

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Early Development

Phoenician and Proto-Sinaitic influences

The Proto-Sinaitic script represents the earliest known alphabetic writing system, dating to approximately 1850–1500 BCE, and emerged as a derivation from Egyptian hieroglyphs employed by Semitic-speaking workers in the Sinai Peninsula.[6] This script innovated the acrophonic principle, whereby pictorial symbols—drawn from hieroglyphic forms—were repurposed to denote the initial consonant sounds of Semitic words rather than entire concepts or syllables, marking a pivotal shift toward phonetic representation.[7] Archaeological evidence, primarily from inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadim in the southern Sinai and Wadi el-Hol in Egypt, illustrates this adaptation, with signs like the ox head for ʾalp (aleph) exemplifying how Egyptian icons were simplified for consonantal values suited to Semitic phonology.[8] Building directly on Proto-Sinaitic foundations, the Phoenician alphabet solidified around 1050 BCE as a streamlined 22-consonant system without vowel markers, written from right to left, and became the primary script for Canaanite and Levantine trade networks.[9] Its letter forms evolved through linear simplification: for instance, the aleph symbol transitioned from the detailed Proto-Sinaitic ox head to a more abstract inverted wedge shape in Phoenician, retaining its acrophonic origin from the Semitic word for "ox" while adapting to efficient inscription on durable materials like stone and papyrus.[10] This alphabet shed overt Egyptian pictorial influences, favoring abstract linear strokes that better accommodated the full range of Semitic phonemes, including gutturals and emphatics absent in Egyptian.[11] Key transitional features between these systems included the progressive loss of hieroglyphic complexity in favor of a purely consonantal repertoire, enabling broader portability across Semitic languages, as evidenced by evolving inscriptions from Proto-Sinaitic's irregular forms to Phoenician's standardized order.[12] By the 11th–10th centuries BCE, Arameans in Syrian regions—such as around Damascus and the Euphrates—adopted this Phoenician script for their vernacular, initiating the Aramaic alphabet's distinct development through local modifications for dialectal sounds.[13] This adoption, supported by early Aramaic inscriptions like those from Tell Fekheriye, reflected the script's adaptability in multicultural trade hubs, setting the stage for its later expansions without altering its core Semitic alphabetic structure.[14]Emergence as Imperial Aramaic script

The Aramaic script began to take shape in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE among the Aramean kingdoms of Syria and northern Mesopotamia, where Arameans developed it as their primary writing system for administrative, royal, and monumental purposes. These kingdoms, including Aram-Damascus and those centered at sites like Zincirli (Sam'al), produced the earliest known Old Aramaic inscriptions, which demonstrate the script's initial forms derived from earlier alphabetic traditions. A prominent example is the Tel Dan Stele, a 9th-century BCE victory monument erected by an Aramean king, likely Hazael of Aram-Damascus, featuring an Aramaic text that records military triumphs over Israelite and Judahite rulers. This inscription, discovered at Tel Dan in northern Israel, showcases the script's early monumental style and provides evidence of its use in royal propaganda within Aramean polities. By the mid-8th century BCE, the script underwent standardization, evolving into a more distinct form suited to Aramaic phonology and practical needs, while maintaining the 22-consonant structure of its precursors but with modified letter shapes. Arameans introduced cursive variants to facilitate writing on perishable materials like papyrus and clay tablets, enhancing its utility for everyday administration and diplomacy in the Neo-Assyrian sphere of influence. This period marked a shift toward a more unified and standardized form that developed into Imperial Aramaic under the Achaemenid Empire, with inscriptions showing increased legibility and consistency across regions, as seen in royal steles and decrees from Aramean rulers. Key artifacts include precursors to later imperial styles, such as the Hadad Inscription from Zincirli (mid-8th century BCE, c. 775–750 BCE), a dedication by King Panamuwa I, and early royal decrees like those of Bar-Hadad, which highlight the transition to a fully alphabetic system independent of earlier syllabic or hieroglyphic influences.[15][16][17] Phonological adaptations in the emerging script accommodated Aramaic's distinctive sounds, particularly the emphatic consonants represented by letters like ṭēṯ (for emphatic /ṭ/) and ṣādē (for emphatic /ṣ/), as well as gutturals such as ʾālap (glottal stop), ḥēṯ (pharyngeal fricative), and ʿāyin (pharyngeal approximant). These features, essential for rendering Aramaic's Semitic phoneme inventory, involved subtle modifications to letter forms to better distinguish sounds absent or differently realized in other dialects, ensuring the script's fidelity to spoken Aramaic in inscriptions from Aramean courts.[17][16]Historical Usage and Spread

Role in the Achaemenid Empire

During the reign of Darius I (c. 522–486 BCE), the Achaemenid Empire adopted Aramaic as its official lingua franca for administration, extending its use across the vast territory from India to Egypt, encompassing numerous provinces.[18] This adoption built on the existing administrative role of Aramaic in the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which the Achaemenids inherited after Cyrus the Great's conquest in 539 BCE, but Darius I standardized it empire-wide to streamline governance over diverse regions.[19] The script's alphabetic efficiency made it ideal for recording transactions and decrees in a multilingual bureaucracy, where it served as the primary medium for imperial correspondence despite the coexistence of languages like Elamite and Old Persian.[20] Official Aramaic, also known as Imperial Aramaic, featured a standardized script with more angular, square-like forms that evolved from earlier cursive styles, promoting uniformity in official documents.[18] To address the limitations of its consonantal system, it employed matres lectionis—consonants repurposed as vowel indicators—such as yod (y) to denote the long vowel /i/ and waw (w) for /u/, enhancing readability without full vocalization. This orthographic innovation, influenced by Old Persian administrative needs, allowed for consistent spelling based on historical roots rather than local dialects, facilitating clear communication across the empire's satrapies.[18] Archaeological evidence underscores Aramaic's dominance in the Achaemenid bureaucracy, as seen in the Persepolis Fortification and Treasury tablets, where Aramaic inscriptions appear on seals and as dockets summarizing Elamite records, indicating its role in cross-linguistic oversight.[21] Similarly, the Elephantine papyri from Egypt reveal Aramaic's use in legal contracts, tax receipts, and military dispatches among Jewish mercenaries, demonstrating a multilingual yet Aramaic-centric system for provincial administration. Achaemenid coinage further attests to this, with Aramaic legends on silver sigloi circulating from the Mediterranean to Central Asia, standardizing economic transactions.[18] Aramaic maintained its preeminence from the 5th to the 4th centuries BCE, enabling efficient trade networks, legal enforcement, and diplomatic exchanges among the empire's ethnic groups, from Scythians to Egyptians.[19] This period of centralized use solidified the script's status as an imperial tool, bridging linguistic barriers and supporting the Achaemenids' vast infrastructure of roads and postal systems.[18]Post-Achaemenid evolution and regional variants

Following the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire in 331 BCE, the standardized Imperial Aramaic script began to fragment into distinct regional variants, as the absence of a central administrative authority allowed local scribal traditions to innovate and adapt the script to specific dialects and cultural contexts.[22] These post-Achaemenid developments marked a shift from uniformity to diversity, with the script retaining core letter forms while incorporating cursive elements and orthographic adjustments suited to trade, religion, and governance in the Hellenistic kingdoms.[16] In the Hellenistic period (4th–1st centuries BCE), Greek administrative dominance following Alexander the Great's conquests influenced Aramaic's role, reducing its status as an imperial lingua franca while fostering localized scripts in eastern trade centers like Palmyra and Hatra. The Palmyrene script, emerging around the 1st century BCE, featured a more angular and lapidary style for monumental inscriptions, reflecting its use in caravan commerce across Syria and Mesopotamia.[16] Similarly, the Hatran script, attested from the 1st century BCE in the Parthian-influenced city of Hatra, adopted a cursive form with elongated strokes, adapted for both official and private documents in northern Mesopotamia.[22] These variants incorporated subtle phonetic distinctions to accommodate regional Aramaic dialects, though they preserved the 22-letter consonantal structure of their Imperial predecessor.[16] During the Parthian (3rd century BCE–3rd century CE) and Sassanid (3rd–7th century CE) eras, further cursive evolutions occurred, particularly in Jewish Palestinian Aramaic and Mandaic scripts, driven by religious and communal needs in Mesopotamia and the Levant. The Jewish Palestinian Aramaic script developed a flowing cursive style by the 2nd century CE, used in rabbinic texts and amulets, with letters like aleph and ayin showing rounded, connected forms for faster writing on papyrus.[23] Mandaic script, originating in the late Parthian period around the 2nd century CE among the Mandaeans in southern Mesopotamia, evolved from Parthian cursive influences, featuring right-to-left orientation with added dots for vowels and spirants to represent the liturgical Mandaic dialect.[24] Prominent regional styles included the Edessan script, an early form of Syriac that arose in the 1st–2nd centuries CE in Edessa (modern Urfa, Turkey), characterized by its estrangela (rounded) letter shapes for Christian liturgical texts, building on post-Achaemenid cursive trends.[25] The Nabataean script, used from the 2nd century BCE in the Nabataean Kingdom of Petra and surrounding areas, adapted the Aramaic alphabet for a transitional Aramaic-Arabic dialect, with letters like final nun curving toward proto-Arabic forms and occasional diacritics for emphatic consonants.[16] These styles often added suprasegmental markers, such as points or lines, to denote vowel qualities or dialectal sounds absent in the original Imperial system.[25] By the 1st century CE, Aramaic had largely declined as a widespread lingua franca in the western Near East, supplanted by Greek in Hellenistic territories and Latin in Roman provinces, though it endured in eastern religious and scholarly contexts like Syriac Christianity and Mandaean rituals.[16] This persistence in sacred texts ensured the script's survival amid broader linguistic shifts, even as regional variants continued to evolve under Parthian and Sassanid patronage.[22]Script Features and Variations

Alphabet composition and letter forms

The Aramaic alphabet consists of 22 consonants, adapted from the Phoenician script around the 10th century BCE and standardized during the Achaemenid Empire as the Imperial Aramaic script. This abjad system represents a consonantal skeleton, with letters evolving in form and function to suit the phonetic needs of Aramaic dialects while maintaining continuity with its Semitic precursors. Key innovations included the retention of 22 letters without addition or subtraction, though phonetic distinctions like emphatic consonants persisted from earlier Northwest Semitic traditions.[26] The following table lists the core 22 consonants in their Imperial Aramaic forms (5th century BCE, as attested in Egyptian documents), with traditional names, approximate phonetic values in International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), and notes on evolution from Phoenician equivalents. Names and values are drawn from Biblical Aramaic conventions, reflecting the script's widespread use.[26]| Letter Name | Imperial Form | Phonetic Value (IPA) | Phoenician Evolution Note | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾĀlap (Aleph) | 𐡀 | /ʔ/ (glottal stop) | Derived from ox-head (ʾalp); silent carrier | 1 |

| Bēt | 𐡁 | /b/ or /v/ | House (bayt); spirantized variant | 2 |

| Gāmal | 𐡂 | /ɡ/ or /ɣ/ | Camel (gamal); softened in later dialects | 3 |

| Dālat | 𐡃 | /d/ or /ð/ | Door (dalt); simple stroke evolution | 4 |

| Hē | 𐡄 | /h/ | Window (hayk); breath sound | 5 |

| Waw | 𐡅 | /w/ or /oː/, /uː/ | Hook (waw); semi-vowel, vowel carrier | 6 |

| Zayin | 𐡆 | /z/ | Weapon (zayt); from Phoenician zayin | 7 |

| Ḥēt | 𐡇 | /ħ/ (pharyngeal fricative) | Wall (ḥiṯ); guttural retention | 8 |

| Ṭēt | 𐡈 | /tˤ/ (emphatic t) | Wheel (ṭwṯ); emphatic from Proto-Semitic | 9 |

| Yōd | 𐡉 | /j/ or /iː/ | Hand (yad); semi-vowel split from waw | 10 |

| Kāp | 𐡊 | /k/ or /x/ | Palm (kap); spirantized | 20 |

| Lāmad | 𐡋 | /l/ | Ox-goad (lamd); unchanged form | 30 |

| Mēm | 𐡌 | /m/ | Water (maym); wavy lines | 40 |

| Nūn | 𐡍 | /n/ | Fish (nūn); serpentine shape | 50 |

| Samek | 𐡎 | /s/ | Support (samk); pillar form | 60 |

| ʿAyin | 𐡏 | /ʕ/ (pharyngeal) | Eye (ʿyn); circle evolution | 70 |

| Pē | 𐡐 | /p/ or /f/ | Mouth (pē); head outline | 80 |

| Ṣādē | 𐡑 | /sˤ/ (emphatic s) | Hunt (ṣd); plant or hook | 90 |

| Qōp | 𐡒 | /q/ (uvular) | Back of head (qwp); monkey-like | 100 |

| Rēš | 𐡓 | /r/ | Head (rʾš); profile shape | 200 |

| Šīn | 𐡔 | /ʃ/ | Tooth (šn); multiple strokes | 300 |

| Taw | 𐡕 | /t/ or /θ/ | Mark (taw); cross or X | 400 |