Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

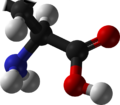

Glutamic acid

View on Wikipedia

Skeletal formula of L-glutamic acid

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Glutamic acid

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

2-Aminopentanedioic acid | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

| ||

| 1723801 (L) 1723799 (rac) 1723800 (D) | |||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChEMBL |

| ||

| ChemSpider |

| ||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.567 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E620 (flavour enhancer) | ||

| 3502 (L) 101971 (rac) 201189 (D) | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

| ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C5H9NO4 | |||

| Molar mass | 147.130 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | White crystalline powder | ||

| Density | 1.4601 (20 °C) | ||

| Melting point | 199 °C (390 °F; 472 K) decomposes | ||

| 8.57 g/L (25 °C)[1] | |||

| Solubility | Ethanol: 350 μg/100 g (25 °C)[2] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) |

| ||

| −78.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Warning | |||

| H315, H319, H335 | |||

| P261, P264, P271, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Glutamic acid (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

[4]Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E;[5] known as glutamate in its anionic form) is an α-amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can synthesize enough for its use.[citation needed] It is also the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate nervous system. It serves as the precursor for the synthesis of the inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in GABAergic neurons.

Its molecular formula is C

5H

9NO

4. Glutamic acid exists in two optically isomeric forms; the dextrorotatory L-form is usually obtained by hydrolysis of gluten or from the waste waters of beet-sugar manufacture or by fermentation.[6][full citation needed] Its molecular structure could be idealized as HOOC−CH(NH

2)−(CH

2)2−COOH, with two carboxyl groups −COOH and one amino group −NH

2. However, in the solid state and mildly acidic water solutions, the molecule assumes an electrically neutral zwitterion structure −OOC−CH(NH+

3)−(CH

2)2−COOH. It is encoded by the codons GAA or GAG.

The acid can lose one proton from its second carboxyl group to form the conjugate base, the singly-negative anion glutamate −OOC−CH(NH+

3)−(CH

2)2−COO−. This form of the compound is prevalent in neutral solutions. The glutamate neurotransmitter plays the principal role in neural activation.[7] This anion creates the savory umami flavor of foods and is found in glutamate flavorings such as monosodium glutamate (MSG). In Europe, it is classified as food additive E620. In highly alkaline solutions the doubly negative anion −OOC−CH(NH

2)−(CH

2)2−COO− prevails. The radical corresponding to glutamate is called glutamyl.

The one-letter symbol E for glutamate was assigned as the letter following D for aspartate, as glutamate is larger by one methylene –CH2– group.[8]

Chemistry

[edit]Ionization

[edit]

When glutamic acid is dissolved in water, the amino group (−NH

2) may gain a proton (H+

), and/or the carboxyl groups may lose protons, depending on the acidity of the medium.

In sufficiently acidic environments, both carboxyl groups are protonated and the molecule becomes a cation with a single positive charge, HOOC−CH(NH+

3)−(CH

2)2−COOH.[9]

At pH values between about 2.5 and 4.1,[9] the carboxylic acid closer to the amine generally loses a proton, and the acid becomes the neutral zwitterion −OOC−CH(NH+

3)−(CH

2)2−COOH. This is also the form of the compound in the crystalline solid state.[10][11] The change in protonation state is gradual; the two forms are in equal concentrations at pH 2.10.[12]

At even higher pH, the other carboxylic acid group loses its proton and the acid exists almost entirely as the glutamate anion −OOC−CH(NH+

3)−(CH

2)2−COO−, with a single negative charge overall. The change in protonation state occurs at pH 4.07.[12] This form with both carboxylates lacking protons is dominant in the physiological pH range (7.35–7.45).

At even higher pH, the amino group loses the extra proton, and the prevalent species is the doubly-negative anion −OOC−CH(NH

2)−(CH

2)2−COO−. The change in protonation state occurs at pH 9.47.[12]

Optical isomerism

[edit]Glutamic acid is chiral; two mirror-image enantiomers exist: d(−), and l(+). The l form is more widely occurring in nature, but the d form occurs in some special contexts, such as the bacterial capsule and cell walls of the bacteria (which produce it from the l form with the enzyme glutamate racemase) and the liver of mammals.[13][14]

History

[edit]Although they occur naturally in many foods, the flavor contributions made by glutamic acid and other amino acids were only scientifically identified early in the 20th century. The substance was discovered and identified in the year 1866 by the German chemist Karl Heinrich Ritthausen, who treated wheat gluten (for which it was named) with sulfuric acid.[15] In 1908, Japanese researcher Kikunae Ikeda of the Tokyo Imperial University identified brown crystals left behind after the evaporation of a large amount of kombu broth as glutamic acid. These crystals, when tasted, reproduced the novel flavor he detected in many foods, most especially in seaweed. Professor Ikeda termed this flavor umami. He then patented a method of mass-producing a crystalline salt of glutamic acid, monosodium glutamate.[16][17]

Synthesis

[edit]Biosynthesis

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2025) |

| Reactants | Products | Enzymes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| glutamine + H2O | → | Glu + NH3 | GLS, GLS2 |

| NAcGlu + H2O | → | Glu + acetate | N-acetyl-glutamate synthase |

| α-ketoglutarate + NADPH + NH4+ | → | Glu + NADP+ + H2O | GLUD1, GLUD2[18] |

| α-ketoglutarate + α-amino acid | → | Glu + α-keto acid | transaminase |

| 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate + NAD+ + H2O | → | Glu + NADH | ALDH4A1 |

| N-formimino-L-glutamate + FH4 | → | Glu + 5-formimino-FH4 | FTCD |

| NAAG | → | Glu + NAA | GCPII |

Industrial synthesis

[edit]Glutamic acid is produced on the largest scale of any amino acid, with an estimated annual production of about 1.5 million tons in 2006.[19] Chemical synthesis was supplanted by the aerobic fermentation of sugars and ammonia in the 1950s, with the organism Corynebacterium glutamicum (also known as Brevibacterium flavum) being the most widely used for production.[20] Isolation and purification can be achieved by concentration and crystallization; it is also widely available as its hydrochloride salt.[21]

Function and uses

[edit]Metabolism

[edit]Glutamate is a key compound in cellular metabolism. In humans, dietary proteins are broken down by digestion into amino acids, which serve as metabolic fuel for other functional roles in the body. A key process in amino acid degradation is transamination, in which the amino group of an amino acid is transferred to an α-ketoacid, typically catalysed by a transaminase. The reaction can be generalised as such:

- R1-amino acid + R2-α-ketoacid ⇌ R1-α-ketoacid + R2-amino acid

A very common α-keto acid is α-ketoglutarate, an intermediate in the citric acid cycle. Transamination of α-ketoglutarate gives glutamate. The resulting α-ketoacid product is often a useful one as well, which can contribute as fuel or as a substrate for further metabolism processes. Examples are as follows:

- aspartate + α-ketoglutarate ⇌ oxaloacetate + glutamate

Both pyruvate and oxaloacetate are key components of cellular metabolism, contributing as substrates or intermediates in fundamental processes such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the citric acid cycle.

Glutamate also plays an important role in the body's disposal of excess or waste nitrogen. Glutamate undergoes deamination, an oxidative reaction catalysed by glutamate dehydrogenase,[18] as follows:

Ammonia (as ammonium) is then excreted predominantly as urea, synthesised in the liver. Transamination can thus be linked to deamination, effectively allowing nitrogen from the amine groups of amino acids to be removed, via glutamate as an intermediate, and finally excreted from the body in the form of urea.

Glutamate is also a neurotransmitter (see below), which makes it one of the most abundant molecules in the brain. Malignant brain tumors known as glioma or glioblastoma exploit this phenomenon by using glutamate as an energy source, especially when these tumors become more dependent on glutamate due to mutations in the gene IDH1.[22][23]

Neurotransmitter

[edit]Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate nervous system.[24] At chemical synapses, glutamate is stored in vesicles. Nerve impulses trigger the release of glutamate from the presynaptic cell. Glutamate acts on ionotropic and metabotropic (G-protein coupled) receptors.[24] In the opposing postsynaptic cell, glutamate receptors, such as the NMDA receptor or the AMPA receptor, bind glutamate and are activated. Because of its role in synaptic plasticity, glutamate is involved in cognitive functions such as learning and memory in the brain.[25] The form of plasticity known as long-term potentiation takes place at glutamatergic synapses in the hippocampus, neocortex, and other parts of the brain. Glutamate works not only as a point-to-point transmitter, but also through spill-over synaptic crosstalk between synapses in which summation of glutamate released from a neighboring synapse creates extrasynaptic signaling/volume transmission.[26] In addition, glutamate plays important roles in the regulation of growth cones and synaptogenesis during brain development as originally described by Mark Mattson.

Brain nonsynaptic glutamatergic signaling circuits

[edit]Extracellular glutamate in Drosophila brains has been found to regulate postsynaptic glutamate receptor clustering, via a process involving receptor desensitization.[27] A gene expressed in glial cells actively transports glutamate into the extracellular space,[27] while, in the nucleus accumbens-stimulating group II metabotropic glutamate receptors, this gene was found to reduce extracellular glutamate levels.[28] This raises the possibility that this extracellular glutamate plays an "endocrine-like" role as part of a larger homeostatic system.

GABA precursor

[edit]Glutamate also serves as the precursor for the synthesis of the inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in GABA-ergic neurons. This reaction is catalyzed by glutamate decarboxylase (GAD).[29] GABA-ergic neurons are identified (for research purposes) by revealing its activity (with the autoradiography and immunohistochemistry methods)[30] which is most abundant in the cerebellum and pancreas.[31]

Stiff person syndrome is a neurologic disorder caused by anti-GAD antibodies, leading to a decrease in GABA synthesis and, therefore, impaired motor function such as muscle stiffness and spasm. Since the pancreas has abundant GAD, a direct immunological destruction occurs in the pancreas and the patients will have diabetes mellitus.[32]

Flavor enhancer

[edit]Glutamic acid, being a constituent of protein, is present in foods that contain protein, but it can only be tasted when it is present in an unbound form. Significant amounts of free glutamic acid are present in a wide variety of foods, including cheeses and soy sauce, and glutamic acid is responsible for umami, one of the five basic tastes of the human sense of taste. Glutamic acid often is used as a food additive and flavor enhancer in the form of its sodium salt, known as monosodium glutamate (MSG).

Nutrient

[edit]All meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, and kombu are excellent sources of glutamic acid. Some protein-rich plant foods also serve as sources. 30% to 35% of gluten (much of the protein in wheat) is glutamic acid. Ninety-five percent of the dietary glutamate is metabolized by intestinal cells in a first pass.[33]

Plant growth

[edit]Auxigro is a plant growth preparation that contains 30% glutamic acid.

NMR spectroscopy

[edit]In recent years,[when?] there has been much research into the use of residual dipolar coupling (RDC) in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). A glutamic acid derivative, poly-γ-benzyl-L-glutamate (PBLG), is often used as an alignment medium to control the scale of the dipolar interactions observed.[34]

Glutamate and aging

[edit]Brain glutamate levels tend to decline with age, and may be a useful as a marker of age-related diseases of the brain.[35]

Pharmacology

[edit]The drug phencyclidine (more commonly known as PCP or 'Angel Dust') antagonizes glutamic acid non-competitively at the NMDA receptor. For the same reasons, dextromethorphan and ketamine also have strong dissociative and hallucinogenic effects. Acute infusion of the drug eglumetad (also known as eglumegad or LY354740), an agonist of the metabotropic glutamate receptors 2 and 3) resulted in a marked diminution of yohimbine-induced stress response in bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata); chronic oral administration of eglumetad in those animals led to markedly reduced baseline cortisol levels (approximately 50 percent) in comparison to untreated control subjects.[36] Eglumetad has also been demonstrated to act on the metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) of human adrenocortical cells, downregulating aldosterone synthase, CYP11B1, and the production of adrenal steroids (i.e. aldosterone and cortisol).[37] Glutamate does not easily pass the blood brain barrier, but, instead, is transported by a high-affinity transport system.[38][39] It can also be converted into glutamine.

Glutamate toxicity can be reduced by antioxidants, and the psychoactive principle of cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and the non psychoactive principle cannabidiol (CBD), and other cannabinoids, is found to block glutamate neurotoxicity with a similar potency, and thereby potent antioxidants.[40][41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "L-Glutamic acid". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Belitz, H.-D.; Grosch, Werner; Schieberle, Peter (27 February 2009). Food Chemistry. Springer. ISBN 978-3540699330.

- ^ "Amino Acid Structures". cem.msu.edu. Archived from the original on 11 February 1998.

- ^ Jetter, R.L. (13 December 1973). AI-MSG modifications: basis for MSG modification design criteria (Report). Office of Scientific and Technical Information (OSTI).

- ^ "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. 1983. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged, Third Edition, 1971.

- ^ Robert Sapolsky (2005), Biology and Human Behavior: The Neurological Origins of Individuality (2nd edition); The Teaching Company. pp. 19–20 of the Guide Book.

- ^ Saffran, M. (April 1998). "Amino acid names and parlor games: from trivial names to a one-letter code, amino acid names have strained students' memories. Is a more rational nomenclature possible?". Biochemical Education. 26 (2): 116–118. doi:10.1016/S0307-4412(97)00167-2.

- ^ a b Neuberger, A. (1936). "Dissociation constants and structures of glutamic acid and its esters". Biochemical Journal. 30 (11): 2085–2094. doi:10.1042/bj0302085. PMC 1263308. PMID 16746266.

- ^ Rodante, F.; Marrosu, G. (1989). "Thermodynamics of the second proton dissociation processes of nine α-amino-acids and the third ionization processes of glutamic acid, aspartic acid and tyrosine". Thermochimica Acta. 141: 297–303. Bibcode:1989TcAc..141..297R. doi:10.1016/0040-6031(89)87065-0.

- ^ Lehmann, Mogens S.; Koetzle, Thomas F.; Hamilton, Walter C. (1972). "Precision neutron diffraction structure determination of protein and nucleic acid components. VIII: the crystal and molecular structure of the β-form of the amino acidl-glutamic acid". Journal of Crystal and Molecular Structure. 2 (5): 225–233. Bibcode:1972JCCry...2..225L. doi:10.1007/BF01246639. S2CID 93590487.

- ^ a b c William H. Brown and Lawrence S. Brown (2008), Organic Chemistry (5th edition). Cengage Learning. p. 1041. ISBN 0495388572, 978-0495388579.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information, "D-glutamate". PubChem Compound Database, CID=23327. Accessed 2017-02-17.

- ^ Liu, L.; Yoshimura, T.; Endo, K.; Kishimoto, K.; Fuchikami, Y.; Manning, J. M.; Esaki, N.; Soda, K. (1998). "Compensation for D-glutamate auxotrophy of Escherichia coli WM335 by D-amino acid aminotransferase gene and regulation of murI expression". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 62 (1): 193–195. doi:10.1271/bbb.62.193. PMID 9501533.

- ^ R. H. A. Plimmer (1912) [1908]. R. H. A. Plimmer; F. G. Hopkins (eds.). The Chemical Constitution of the Protein. Monographs on biochemistry. Vol. Part I. Analysis (2nd ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 114. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Renton, Alex (10 July 2005). "If MSG is so bad for you, why doesn't everyone in Asia have a headache?". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ "Kikunae Ikeda Sodium Glutamate". Japan Patent Office. 7 October 2002. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ a b Grabowska, A.; Nowicki, M.; Kwinta, J. (2011). "Glutamate dehydrogenase of the germinating triticale seeds: Gene expression, activity distribution and kinetic characteristics". Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 33 (5): 1981–1990. Bibcode:2011AcPPl..33.1981G. doi:10.1007/s11738-011-0801-1.

- ^ Alvise Perosa; Fulvio Zecchini (2007). Methods and Reagents for Green Chemistry: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-470-12407-9.

- ^ Michael C. Flickinger (2010). Encyclopedia of Industrial Biotechnology: Bioprocess, Bioseparation, and Cell Technology, 7 Volume Set. Wiley. pp. 215–225. ISBN 978-0-471-79930-6.

- ^ Foley, Patrick; Kermanshahi pour, Azadeh; Beach, Evan S.; Zimmerman, Julie B. (2012). "Derivation and synthesis of renewable surfactants". Chem. Soc. Rev. 41 (4): 1499–1518. doi:10.1039/C1CS15217C. ISSN 0306-0012. PMID 22006024.

- ^ van Lith, SA; Navis, AC; Verrijp, K; Niclou, SP; Bjerkvig, R; Wesseling, P; Tops, B; Molenaar, R; van Noorden, CJ; Leenders, WP (August 2014). "Glutamate as chemotactic fuel for diffuse glioma cells: are they glutamate suckers?". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1846 (1): 66–74. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.004. PMID 24747768.

- ^ van Lith, SA; Molenaar, R; van Noorden, CJ; Leenders, WP (December 2014). "Tumor cells in search for glutamate: an alternative explanation for increased invasiveness of IDH1 mutant gliomas". Neuro-Oncology. 16 (12): 1669–1670. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou152. PMC 4232089. PMID 25074540.

- ^ a b Meldrum, B. S. (2000). "Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: Review of physiology and pathology". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4S Suppl): 1007S – 1015S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.1007s. PMID 10736372.

- ^ McEntee, W. J.; Crook, T. H. (1993). "Glutamate: Its role in learning, memory, and the aging brain". Psychopharmacology. 111 (4): 391–401. doi:10.1007/BF02253527. PMID 7870979. S2CID 37400348.

- ^ Okubo, Y.; Sekiya, H.; Namiki, S.; Sakamoto, H.; Iinuma, S.; Yamasaki, M.; Watanabe, M.; Hirose, K.; Iino, M. (2010). "Imaging extrasynaptic glutamate dynamics in the brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (14): 6526–6531. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6526O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913154107. PMC 2851965. PMID 20308566.

- ^ a b Augustin H, Grosjean Y, Chen K, Sheng Q, Featherstone DE (2007). "Nonvesicular Release of Glutamate by Glial xCT Transporters Suppresses Glutamate Receptor Clustering In Vivo". Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (1): 111–123. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4770-06.2007. PMC 2193629. PMID 17202478.

- ^ Zheng Xi; Baker DA; Shen H; Carson DS; Kalivas PW (2002). "Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 300 (1): 162–171. doi:10.1124/jpet.300.1.162. PMID 11752112.

- ^ Bak, Lasse K.; Schousboe, Arne; Waagepetersen, Helle S. (August 2006). "The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer". Journal of Neurochemistry. 98 (3): 641–653. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03913.x. ISSN 0022-3042. PMID 16787421.

- ^ Kerr, D.I.B.; Ong, J. (January 1995). "GABAB receptors". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 67 (2): 187–246. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(95)00016-A. PMID 7494864.

- ^ Krueger, Christian; Stöker, Winfried; Schlosser, Michael (2007). "GLUTAMIC ACID DECARBOXYLASE AUTOANTIBODIES". Autoantibodies (2nd ed.). pp. 369–378. doi:10.1016/B978-044452763-9/50052-4. ISBN 978-0-444-52763-9.

- ^ Newsome, Scott D.; Johnson, Tory (15 August 2022). "Stiff Person Syndrome Spectrum Disorders; More Than Meets the Eye". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 369 577915. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577915. ISSN 0165-5728. PMC 9274902. PMID 35717735.

- ^ Reeds, P.J.; et al. (1 April 2000). "Intestinal glutamate metabolism". Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4s): 978S – 982S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.978S. PMID 10736365.

- ^ C. M. Thiele, Concepts Magn. Reson. A, 2007, 30A, 65–80

- ^ Chang, Linda; Jiang, Caroline S.; Ernst, Thomas (1 January 2009). "Effects of age and sex on brain glutamate and other metabolites". Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 27 (1): 142–145. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2008.06.002. ISSN 0730-725X. PMC 3164853. PMID 18687554.

- ^ Coplan JD, Mathew SJ, Smith EL, Trost RC, Scharf BA, Martinez J, Gorman JM, Monn JA, Schoepp DD, Rosenblum LA (July 2001). "Effects of LY354740, a novel glutamatergic metabotropic agonist, on nonhuman primate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and noradrenergic function". CNS Spectr. 6 (7): 607–612, 617. doi:10.1017/S1092852900002157. PMID 15573025. S2CID 6029856.

- ^ Felizola SJ, Nakamura Y, Satoh F, Morimoto R, Kikuchi K, Nakamura T, Hozawa A, Wang L, Onodera Y, Ise K, McNamara KM, Midorikawa S, Suzuki S, Sasano H (January 2014). "Glutamate receptors and the regulation of steroidogenesis in the human adrenal gland: The metabotropic pathway". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 382 (1): 170–177. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2013.09.025. PMID 24080311. S2CID 3357749.

- ^ Smith, Quentin R. (April 2000). "Transport of glutamate and other amino acids at the blood–brain barrier". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (4S Suppl): 1016S – 1022S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.1016S. PMID 10736373.

- ^ Hawkins, Richard A. (September 2009). "The blood-brain barrier and glutamate". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 90 (3): 867S – 874S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.27462BB. PMC 3136011. PMID 19571220.

This organization does not allow net glutamate entry to the brain; rather, it promotes the removal of glutamate and the maintenance of low glutamate concentrations in the ECF.

- ^ Hampson, Aidan J. (1998). "Cannabidiol and (−)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95 (14): 8268–8273. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.8268. PMC 20965. PMID 9653176.

- ^ Hampson, Aidan J. (2006). "Neuroprotective Antioxidants from Marijuana". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 899 (1): 274–282. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06193.x. S2CID 39496546.

Further reading

[edit]- Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005). Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.