Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Renaissance humanism

View on Wikipedia

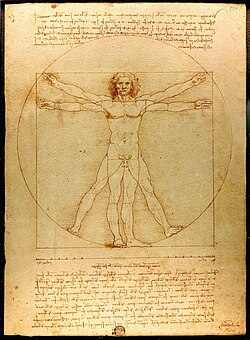

"In his explicit turn back to an ancient model in search of knowledge and wisdom, Leonardo follows early humanist practice. What he finds in Vitruvius is a mathematical formula for the proportions of all parts of the human body, which results in its idealized representation as the true microcosmic measure of all things. [...]The perfection of this ideal human form corresponds visually to the early humanist belief in the unique central placement of human beings within the divine universal order and their consequent human grandeur and dignity, expressed in the philosopher Pico della Mirandola's Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486), known as the manifesto of the Renaissance."

— Anne Hudson Jones[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

Renaissance humanism is a worldview centered on the nature and importance of humanity that emerged from the study of Classical antiquity.

Renaissance humanists sought to create a citizenry able to speak and write with eloquence and clarity, and thus capable of engaging in the civic life of their communities and persuading others to virtuous and prudent actions. Humanism, while set up by a small elite who had access to books and education, was intended as a cultural movement to influence all of society. It was a program to revive the cultural heritage, literary legacy, and moral philosophy of the Greco-Roman civilization.

It first began in Italy and then spread across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term humanist (Italian: umanista) referred to teachers and students of the humanities, known as the studia humanitatis, which included the study of Latin and Ancient Greek literatures, grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. It was not until the 19th century that this began to be called humanism instead of the original humanities, and later by the retronym Renaissance humanism to distinguish it from later humanist developments.[2]

During the Renaissance period most humanists were Christians, so their concern was to "purify and renew Christianity", not to do away with it. Their vision was to return ad fontes ("to the pure sources") to the Gospels, the New Testament and the Church Fathers, bypassing the complexities of medieval Christian theology.[3]

Definition

[edit]

Very broadly, the project of the Italian Renaissance humanists of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was the studia humanitatis: the study of the humanities, "a curriculum focusing on language skills."[5] This project sought to recover the culture of ancient Greece and Rome through its literature and philosophy and to use this classical revival to imbue the ruling classes with the moral attitudes of said ancients—a project James Hankins calls one of "virtue politics."[6] But what this studia humanitatis actually constituted is a subject of much debate. According to one scholar of the movement,

Early Italian humanism, which in many respects continued the grammatical and rhetorical traditions of the Middle Ages, not merely provided the old Trivium with a new and more ambitious name (Studia humanitatis), but also increased its actual scope, content and significance in the curriculum of the schools and universities and in its own extensive literary production. The studia humanitatis excluded logic, but they added to the traditional grammar and rhetoric not only history, Greek, and moral philosophy, but also made poetry, once a sequel of grammar and rhetoric, the most important member of the whole group.[7]

However, in investigating this definition in his article "The changing concept of the studia humanitatis in the early Renaissance," Benjamin G. Kohl provides an account of the various meanings the term took on over the course of the period.[8]

- Around the middle of the fourteenth century, when the term first came into use among Italian literati, it was used in reference to a very specific text: as praise of the cultural and moral attitudes expressed in Cicero's Pro Archia poeta (62 BCE).

- Tuscan humanist Coluccio Salutati popularized the term in the 1370s, using the phrase to refer to culture and learning as a guide to moral life, with a focus on rhetoric and oration. Over the years, he came to use it specifically in literary praise of his contemporaries, but later viewed the studia humanitatis as a means of editing and restoring ancient texts and even understanding scripture and other divine literature.

- But it was not until the beginning of the quattrocento (15th century) that the studia humanitatis began to be associated with particular academic disciplines, when Pier Paolo Vergerio, in his De ingenuis moribus, stressed the importance of rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy as a means of moral improvement.

- By the middle of the century, the term was adopted more formally, as it started to be used in Bologna and Padua in reference to university courses that taught these disciplines as well as Latin poetry, before then spreading northward throughout Italy.

- But the first instance of it as encompassing grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy all together only came when Tommaso Parentucelli wrote to Cosimo de' Medici with recommendations regarding his library collection, saying, "de studiis autem humanitatis quantum ad grammaticam, rhetoricam, historicam et poeticam spectat ac moralem" ("concerning studies of the humanities, insofar as they [consist of] grammar, rhetoric, history and poetry, and also ethics").[9]

And so, the term studia humanitatis took on a variety of meanings over the centuries, being used differently by humanists across the various Italian city-states as one definition got adopted and spread across the country. Still, it has referred consistently to a mode of learning—formal or not—that results in one's moral edification.[8]

Under the influence and inspiration of the classics, Renaissance humanists developed a new rhetoric and new learning. Some scholars also argue that humanism articulated new moral and civic perspectives, and values offering guidance in life to all citizens. Renaissance humanism was a response to what came to be depicted by later whig historians as the "narrow pedantry" associated with medieval scholasticism.[10]

History

[edit]| Renaissance |

|---|

|

| Aspects |

| Regions |

| History and study |

In the last years of the 13th century and in the first decades of the 14th century, the cultural climate was changing in some European regions. The rediscovery, study, and renewed interest in authors who had been forgotten, and in the classical world that they represented, inspired a flourishing return to linguistic, stylistic and literary models of antiquity. There emerged a consciousness of the need for a cultural renewal, which sometimes also meant a detachment from contemporary culture. Manuscripts and inscriptions were in high demand and graphic models were also imitated. This "return to the ancients" was the main component of so-called "pre-humanism", which developed particularly in Tuscany, in the Veneto region, and at the papal court of Avignon, through the activity of figures such as Lovato Lovati and Albertino Mussato in Padua, Landolfo Colonna in Avignon, Ferreto de' Ferreti in Vicenza, Convenevole from Prato in Tuscany and then in Avignon, and many others.[11]

By the 14th century some of the first humanists were great collectors of antique manuscripts, including Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Coluccio Salutati, and Poggio Bracciolini. Of the four, Petrarch was dubbed the "Father of Humanism," as he was the one who first encouraged the study of pagan civilizations and the teaching of classical virtues as a means of preserving Christianity.[6] He also had a library, of which many manuscripts did not survive.[12][citation needed] Many worked for the Catholic Church and were in holy orders, like Petrarch, while others were lawyers and chancellors of Italian cities, and thus had access to book copying workshops, such as Petrarch's disciple Salutati, the Chancellor of Florence.

In Italy, the humanist educational program won rapid acceptance and, by the mid-15th century, many of the upper classes had received humanist educations, possibly in addition to traditional scholastic ones. Some of the highest officials of the Catholic Church were humanists with the resources to amass important libraries. Such was Cardinal Basilios Bessarion, a convert to the Catholic Church from Greek Orthodoxy, who was considered for the papacy, and was one of the most learned scholars of his time. There were several 15th-century and early 16th-century humanist Popes[13] one of whom, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II), was a prolific author and wrote a treatise on The Education of Boys.[14] These subjects came to be known as the humanities, and the movement which they inspired is shown as humanism.

The migration waves of Byzantine Greek scholars and émigrés in the period following the Crusader sacking of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 was a very welcome addition to the Latin texts scholars like Petrarch had found in monastic libraries[15] for the revival of Greek literature and science via their greater familiarity with ancient Greek works.[16][17] They included Gemistus Pletho, George of Trebizond, Theodorus Gaza, and John Argyropoulos.

There were important centres of Renaissance humanism in Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Genoa, Livorno, Mantua, Padua, Pisa, Naples, Rome, Siena, Venice, Vicenza, and Urbino.

Italian humanism spread to Spain, with Francisco de Vitoria becoming its first great exponent.[18] His work on the rights of the Spanish subjects in America, which became seminal, earned him being called the father of modern international law.[19] He founded the School of Salamanca, of which Antonio de Nebrija became one of its main members. A circle of humanists also formed around King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, with names like Alfonso and Juan de Valdés, Juan Luis Vives and Luisa Sigea.[20] Charles appointed another noted humanist, Mercurino di Gattinara, as his chancellor.[21] The Valdés brothers, Gattinara and Antonio de Guevara were proponents of working towards the restoration of a Christian, universal Roman Empire, an idea originally inspired by Dante Alighieri in his Monarchia.[22] Spain's perennial state of war, in conflicts like the Italian Wars and the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars, favored a militant conception of humanism known as las armas y las letras ("the weapons and the letters"), first codified in Charles' court by Baldassare Castiglione.[23][24]

Humanism also spread northward to France, Germany, the Low Countries, Poland-Lithuania, Hungary and England with the adoption of large-scale printing after 1500, and it became associated with the Reformation. In France, pre-eminent humanist Guillaume Budé (1467–1540) applied the philological methods of Italian humanism to the study of antique coinage and to legal history, composing a detailed commentary on Justinian's Code. Budé was a royal absolutist (and not a republican like the early Italian umanisti) who was active in civic life, serving as a diplomat for Francis I and helping to found the Collège des Lecteurs Royaux (later the Collège de France). Meanwhile, Marguerite de Navarre, the sister of Francis I, was a poet, novelist, and religious mystic[25] who gathered around her and protected a circle of vernacular poets and writers, including Clément Marot, Pierre de Ronsard, and François Rabelais.

Paganism and Christianity in the Renaissance

[edit]Many humanists were churchmen, most notably Pope Pius II, Sixtus IV, and Leo X,[26][27] and there was often patronage of humanists by senior church figures.[28] Much humanist effort went into improving the understanding and translations of Biblical and early Christian texts, both before and after the Reformation, which was greatly influenced by the work of non-Italian, Northern European figures such as Erasmus, Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, William Grocyn, and Swedish Catholic Archbishop in exile Olaus Magnus.

Description

[edit]The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy describes the rationalism of ancient writings as having tremendous impact on Renaissance scholars:

Here, one felt no weight of the supernatural pressing on the human mind, demanding homage and allegiance. Humanity—with all its distinct capabilities, talents, worries, problems, possibilities—was the center of interest. It has been said that medieval thinkers philosophised on their knees, but, bolstered by the new studies, they dared to stand up and to rise to full stature.[29]

In 1417, for example, Poggio Bracciolini discovered the manuscript of Lucretius, De rerum natura, which had been lost for centuries and which contained an explanation of Epicurean doctrine, though at the time this was not commented on much by Renaissance scholars, who confined themselves to remarks about Lucretius's grammar and syntax.

Only in 1564 did French commentator Denys Lambin (1519–72) announce in the preface to the work that "he regarded Lucretius's Epicurean ideas as 'fanciful, absurd, and opposed to Christianity'." Lambin's preface remained standard until the nineteenth century.[30] Epicurus's unacceptable doctrine that pleasure was the highest good "ensured the unpopularity of his philosophy".[31] Lorenzo Valla, however, puts a defense of epicureanism in the mouth of one of the interlocutors of one of his dialogues.

Epicureanism

[edit]Charles Trinkhaus regards Valla's "epicureanism" as a ploy, not seriously meant by Valla, but designed to refute Stoicism, which he regarded together with epicureanism as equally inferior to Christianity.[32] Valla's defense, or adaptation, of Epicureanism was later taken up in The Epicurean by Erasmus, the "Prince of humanists:"

If people who live agreeably are Epicureans, none are more truly Epicurean than the righteous and godly. And if it is names that bother us, no one better deserves the name of Epicurean than the revered founder and head of the Christian philosophy Christ, for in Greek epikouros means "helper". He alone, when the law of Nature was all but blotted out by sins, when the law of Moses incited to lists rather than cured them, when Satan ruled in the world unchallenged, brought timely aid to perishing humanity. Completely mistaken, therefore, are those who talk in their foolish fashion about Christ's having been sad and gloomy in character and calling upon us to follow a dismal mode of life. On the contrary, he alone shows the most enjoyable life of all and the one most full of true pleasure.[33]

This passage exemplifies the way in which the humanists saw pagan classical works, such as the philosophy of Epicurus, as being in harmony with their interpretation of Christianity.

Neo-Platonism

[edit]Renaissance Neo-Platonists such as Marsilio Ficino (whose translations of Plato's works into Latin were still used into the 19th century) attempted to reconcile Platonism with Christianity, according to the suggestions of early Church Fathers Lactantius and Saint Augustine. In this spirit, Pico della Mirandola attempted to construct a syncretism of religions and philosophies with Christianity, but his work did not win favor with the church authorities, who rejected it because of his views on magic.[34]

Evolution and reception

[edit]The historian of the Renaissance Sir John Hale cautions against too direct a linkage between Renaissance humanism and modern uses of the term humanism: "Renaissance humanism must be kept free from any hint of either 'humanitarianism' or 'humanism' in its modern sense of rational, non-religious approach to life ... the word 'humanism' will mislead ... if it is seen in opposition to a Christianity its students in the main wished to supplement, not contradict, through their patient excavation of the sources of ancient God-inspired wisdom."[35]

Individual freedom

[edit]Historian Steven Kreis expresses a widespread view (derived from the 19th-century Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt), when he writes that:

The period from the fourteenth century to the seventeenth worked in favor of the general emancipation of the individual. The city-states of northern Italy had come into contact with the diverse customs of the East, and gradually permitted expression in matters of taste and dress. The writings of Dante, and particularly the doctrines of Petrarch and humanists like Machiavelli, emphasized the virtues of intellectual freedom and individual expression. In the essays of Montaigne the individualistic view of life received perhaps the most persuasive and eloquent statement in the history of literature and philosophy.[36]

Two noteworthy trends in some Renaissance humanists were Renaissance Neo-Platonism and Hermeticism, which through the works of figures like Nicholas of Kues, Giordano Bruno, Cornelius Agrippa, Campanella and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola sometimes came close to constituting a new religion itself.[according to whom?] Of these two, Hermeticism has had great continuing influence in Western thought, while the former mostly dissipated as an intellectual trend, leading to movements in Western esotericism such as Theosophy and New Age thinking.[37] The "Yates thesis" of Frances Yates holds that before falling out of favour, esoteric Renaissance thought introduced several concepts that were useful for the development of scientific method, though this remains a matter of controversy.

Sixteenth century and beyond

[edit]| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

Though humanists continued to use their scholarship in the service of the church into the middle of the sixteenth century and beyond, the sharply confrontational religious atmosphere following the Reformation resulted in the Counter-Reformation that sought to silence challenges to Catholic theology,[38] with similar efforts among the Protestant denominations. Some humanists, even moderate Catholics such as Erasmus, risked being declared heretics for their perceived criticism of the institutional church.[39]

A number of humanists joined the Reformation movement and took over leadership functions, for example, Philipp Melanchthon, Ulrich Zwingli, Henry VIII, John Calvin, and William Tyndale. Others, like Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, were favorable to it although they remained Catholic.

With the Counter-Reformation initiated by the Council of Trent (1545–1563), positions hardened and a strict Catholic orthodoxy based on scholastic philosophy was imposed. However the education systems developed by Jesuits ran on humanist lines.

Historiography

[edit]Baron thesis

[edit]Hans Baron (1900–1988) was the inventor of the now ubiquitous term "civic humanism." First coined in the 1920s and based largely on his studies of Leonardo Bruni, Baron's "thesis" proposed the existence of a central strain of humanism, particularly in Florence and Venice, dedicated to republicanism.

As argued in his chef-d'œuvre, The Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance: Civic Humanism and Republican Liberty in an Age of Classicism and Tyranny, the German historian thought that civic humanism originated in around 1402, after the great struggles between Florence and Visconti-led Milan in the 1390s. He considered Petrarch's humanism to be a rhetorical, superficial project, and viewed this new strand to be one that abandoned the feudal and supposedly "otherworldly" (i.e., divine) ideology of the Middle Ages in favour of putting the republican state and its freedom at the forefront of the "civic humanist" project.[40] Already controversial at the time of The Crisis' publication, the "Baron Thesis" has been met with even more criticism over the years.

Even in the 1960s, historians Philip Jones and Peter Herde[41] found Baron's praise of "republican" humanists naive, arguing that republics were far less liberty-driven than Baron had believed, and were practically as undemocratic as monarchies. James Hankins adds that the disparity in political values between the humanists employed by oligarchies and those employed by princes was not particularly notable, as all of Baron's civic ideals were exemplified by humanists serving various types of government. In so arguing, he asserts that a "political reform program is central to the humanist movement founded by Petrarch. But it is not a 'republican' project in Baron's sense of republic; it is not an ideological product associated with a particular regime type."[6]

Garin and Kristeller

[edit]Two renowned Renaissance scholars, Eugenio Garin and Paul Oskar Kristeller collaborated with one another throughout their careers. But while the two historians were on good terms, they fundamentally disagreed on the nature of Renaissance humanism.

- Kristeller affirmed that Renaissance humanism used to be viewed just as a project of Classical revival, one that led to great increase in Classical scholarship. But he argued that this theory "fails to explain the ideal of eloquence persistently set forth in the writings of the humanists," asserting that "their classical learning was incidental to" their being "professional rhetoricians."[42] Similarly, he considered their influence on philosophy and particular figures' philosophical output to be incidental to their humanism, viewing grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and ethics to be the humanists' main concerns.

- Garin, on the other hand, viewed philosophy itself as being ever-evolving, each form of philosophy being inextricable from the practices of the thinkers of its period. He thus considered the Italian humanists' break from Scholasticism and newfound freedom to be perfectly in line with this broader sense of philosophy.[43]

During the period in which they argued over these differing views, there was a broader cultural conversation happening regarding Humanism: one revolving around Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger.

- In 1946, Sartre published a work called "L'existentialisme est un humanisme," in which he outlined his conception of existentialism as revolving around the belief that "existence comes before essence"; that man "first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world – and defines himself afterwards," making himself and giving himself purpose.[44]

- Heidegger, in a response to this work of Sartre's, declared: "For this is humanism: meditating and caring, that human beings be human and not inhumane, "inhuman", that is, outside their essence."[45] He also discussed a decline in the concept of humanism, pronouncing that it had been dominated by metaphysics and essentially discounting it as philosophy. He also explicitly criticized Italian Renaissance humanism in the letter.[46]

While this discourse was taking place outside the realm of Renaissance Studies (for more on the evolution of the term "humanism," see Humanism), this background debate was not irrelevant to Kristeller and Garin's ongoing disagreement. Kristeller—who had at one point studied under Heidegger[47]—also discounted (Renaissance) humanism as philosophy, and Garin's Der italienische Humanismus was published alongside Heidegger's response to Sartre—a move that Rubini describes as an attempt "to stage a pre-emptive confrontation between historical humanism and philosophical neo-humanisms."[48] Garin also conceived of the Renaissance humanists as occupying the same kind of "characteristic angst the existentialists attributed to men who had suddenly become conscious of their radical freedom," further weaving philosophy with Renaissance humanism.[43]

Hankins summarizes the Kristeller v. Garin debate as:

- Kristeller conceives of professional philosophers as being very formal and method-focused.[43] Renaissance humanists, on the other hand, he viewed to be professional rhetoricians who, using their classically-inspired paideia or institutio, did improve fields such as philosophy, but without the practice of philosophy being their main goal or function.[42]

- Garin, instead, wanted his "humanist-philosophers to be organic intellectuals," not constituting a rigid school of thought, but having a shared outlook on life and education that broke with the medieval traditions that came before them.[43]

I. R. Grigulevich

[edit]According to Russian historian and Stalinist assassin Iosif Grigulevich two characteristic traits of late Renaissance humanism were "its revolt against abstract, Aristotelian modes of thought and its concern with the problems of war, poverty, and social injustice."[49]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hudson Jones, Anne. "Neh Institute". uva.theopenscholar.com.

- ^ The term la rinascita (rebirth) first appeared, however, in its broad sense in Giorgio Vasari's Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani (The Lives of the Artists, 1550, revised 1568) Panofsky, Erwin. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art, New York: Harper and Row, 1960. "The term umanista was used in fifteenth-century Italian academic slang to describe a teacher or student of classical literature and the arts associated with it, including that of rhetoric. The English equivalent 'humanist' makes its appearance in the late sixteenth century with a similar meaning. Only in the nineteenth century, however, and probably for the first time in Germany in 1809, is the attribute transformed into a substantive: humanism, standing for devotion to the literature of ancient Greece and Rome, and the humane values that may be derived from them" Nicholas Mann "The Origins of Humanism", Cambridge Companion to Humanism, Jill Kraye, editor [Cambridge University Press, 1996], p. 1–2). The term "Middle Ages" for the preceding period separating classical antiquity from its "rebirth" first appears in Latin in 1469 as media tempestas. For humanities as the original term for Renaissance humanism, see James Fieser, Samuel Enoch Stumpf "Philosophy during the Renaissance", Philosophy: A Historical Survey with Essential Readings (9th ed.) [McGraw-Hill Education, 2014]

- ^ McGrath, Alister (2011). Christian Theology: An Introduction (5th ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4443-3514-9.

- ^ "Six Tuscan Poets, Giorgio Vasari". collections.artsmia.org. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Minneapolis Institute of Art. 2023. Archived from the original on 17 June 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Rummel, Erika (1992). "Et cum theologo bella poeta gerit: The Conflict between Humanists and Scholastics Revisited". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 23 (4): 713–726. doi:10.2307/2541729. ISSN 0361-0160. JSTOR 2541729.

- ^ a b c Hankins, James (2019). Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy. The Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- ^ Paul Oskar Kristeller, Renaissance Thought II: Papers on Humanism and the Arts (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1965), p. 178. See also Kristeller's Renaissance Thought I, "Humanism and Scholasticism In the Italian Renaissance", Byzantion 17 (1944–45), pp. 346–74. Reprinted in Renaissance Thought (New York: Harper Torchbooks), 1961.

- ^ a b Kohl, Benjamin G. (1992). "The Changing Concept of the "Studia Humanitatis" in the Early Renaissance". Renaissance Studies. 6 (2): 185–209. doi:10.1111/1477-4658.t01-1-00116. ISSN 0269-1213. JSTOR 24412493.

- ^ Sforza, Giovanni (1884). "La patria, la famiglia e la giovinezza di papa Niccolò V". Atti della Reale Accademia Lucchese di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti. XXIII: 380.

- ^ Craig W. Kallendorf, introduction to Humanist Educational Treatises, edited and translated by Craig W. Kallendorf (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London England: The I Tatti Renaissance Library, 2002) p. vii.

- ^ "Return to the style of the ancients and the anti-gothic reaction". www.vatlib.it. Latin Paleography.

- ^ Fredi Chiappelli (January 1981). "Petrarch and Innovation: A Note on a Manuscript". MLN. 96 (1): 138–143. doi:10.2307/2906433. JSTOR 2906433.Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ They include Innocent VII, Nicholas V, Pius II, Sixtus IV, Alexander VI, Julius II and Leo X. Innocent VII, patron of Leonardo Bruni, is considered the first humanist Pope. See James Hankins, Plato in the Italian Renaissance (New York: Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition, 1990), p. 49; for the others, see their respective entries in Sir John Hale's Concise Encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 1981).

- ^ See Humanist Educational Treatises, (2001) pp. 126–259. This volume (pp. 92–125) contains an essay by Leonardo Bruni, entitled "The Study of Literature", on the education of girls.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark. "Renaissance Humanism". World History Encyclopedia. The Classical Ideal. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ "Byzantines in Renaissance Italy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ^ Greeks in Italy

- ^ Frayle Delgado (2004), p. 28-29.

- ^ Scott (2000), p. 163-173.

- ^ Jones, Richard O., El Renacimiento en España: ideas y actitudes, in Historia de la literatura española, vol. 2: Siglo de Oro: prosa y poesía., Barcelona, Ariel, 2000 (14ª ed. rev.), chap. 1, pgs. 17-54

- ^ Callado Estela (2022), p. 58-59.

- ^ Callado Estela (2022), p. 97-99.

- ^ García Gibert (2010), p. 35-36.

- ^ Fernández Hoyos, M. A. (1998). Las armas y las letras en Felipe II. "Felipe II (1598-1998), Europa dividida, la monarquía católica de Felipe II", Vol. 4, ISBN 84-8230-025-3, págs. 117-132

- ^ She was the author of Miroir de l'ame pecheresse (The Mirror of a Sinful Soul), published after her death, among other devotional poetry. See also "Marguerite de Navarre: Religious Reformist" in Jonathan A. Reid, King's sister--queen of dissent: Marguerite of Navarre (1492–1549) and her evangelical network [dead link] (Studies in medieval and Reformation traditions, 1573–4188; v. 139). Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2009. (2 v.: (xxii, 795 p.) ISBN 978-90-04-17760-4 (v. 1), 9789004177611 (v. 2)

- ^ Löffler, Klemens (1910). "Humanism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. VII. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 538–542.

- ^ See note two, above.

- ^ Davies, 477

- ^ "Humanism". The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Second Edition. Cambridge University Press. 1999. p.397 quotation:

The unashamedly humanistic flavor of classical writings had a tremendous impact on Renaissance scholar.

- ^ See Jill Kraye's essay, "Philologists and Philosophers" in the Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism [1996], p. 153.)

- ^ (Kraye [1996] p. 154.)

- ^ See Trinkaus, In Our Image and Likeness Vol. 1 (University of Chicago Press, 1970), pp. 103–170

- ^ John L. Lepage (5 December 2012). The Revival of Antique Philosophy in the Renaissance. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-137-28181-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Daniel O'Callaghan (9 November 2012). The Preservation of Jewish Religious Books in Sixteenth-Century Germany: Johannes Reuchlin's Augenspiegel. BRILL. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-90-04-24185-5.

- ^ Hale, 171. See also Davies, 479–480 for similar caution.

- ^ Kreis, Steven (2008). "Renaissance Humanism". Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Plumb, 95

- ^ "Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library & Renaissance Culture: Humanism". The Library of Congress. 2002-07-01. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ "Humanism". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Religion. Vol. F–N. Corpus Publications. 1979. pp. 1733. ISBN 978-0-9602572-1-8.

- ^ Hankins, James (1995). "The "Baron Thesis" after Forty Years and Some Recent Studies of Leonardo Bruni". Journal of the History of Ideas. 56 (2): 309–338. doi:10.2307/2709840. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709840.

- ^ See Philip Jones, "Communes and Despots: The City-State in Late-Medieval Italy," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th ser., 15 (1965), 71–96, and review of Baron's Crisis (2nd ed.), in History, 53 (1968), 410–13; Peter Herde, "Politik und Rhetorik in Florenz am Vorabend der Renaissance," Archiv far Kulturgeschichte, 50 (1965), 141–220; idem, "Politische Verhaltensweise der Florentiner Oligarchie,1382–1402," in Geschichte und Verfassungsgefüge: Frankfurter Festgabe für Walter Schlesinger (Wiesbaden, 1973).

- ^ a b Kristeller, Paul Oskar (1944). "Humanism and Scholasticism in the Italian Renaissance". Byzantion. 17: 346–374. ISSN 0378-2506. JSTOR 44168603.

- ^ a b c d Hankins, James. 2011. "Garin and Paul Oskar Kristeller: Existentialism, Neo-Kantianism, and the Post-war Interpretation of Renaissance Humanism". In Eugenio Garin: Dal Rinascimento all'Illuminismo, ed. Michele Ciliberto, 481–505. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Existentialism Is a Humanism". In Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre, tr. Walter Kaufmann, 287–311. New York: Meridian Books, 1956.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin. "Letter on 'Humanism'". In Pathmarks, ed. William McNeill, 239–276. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- ^ Kakkori, Leena; Huttunen, Rauno (June 2012). "The Sartre-Heidegger Controversy on Humanism and the Concept of Man in Education". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 44 (4): 351–365. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2010.00680.x. ISSN 0013-1857. S2CID 145476769.

- ^ R. Popkin, The History of Scepticism: From Savonarola to Bayle rev. ed. (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. viii.

- ^ Rubini, Rocco (2011). "The Last Italian Philosopher: Eugenio Garin (with an Appendix of Documents)." Intellectual History Review. 21 (2): 209–230. DOI: 10.1080/17496977.2011.574348

- ^ Keen, Benjamin (1977). "The Legacy of Bartolomé de las Casas" (PDF). Ibero-Americana Pragensia. 11.

Further reading

[edit]- Bolgar, R. R. The Classical Heritage and Its Beneficiaries: from the Carolingian Age to the End of the Renaissance. Cambridge, 1954.

- Callado Estela, Emilio (2022). Tiempos de reforma: Pensamiento y religión en la época de Carlos V. ESIC. ISBN 9788411228411.

- Cassirer, Ernst. Individual and Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy. Harper and Row, 1963.

- Cassirer, Ernst (Editor), Paul Oskar Kristeller (Editor), John Herman Randall (Editor). The Renaissance Philosophy of Man. University of Chicago Press, 1969.

- Cassirer, Ernst. Platonic Renaissance in England. Gordian, 1970.

- Celenza, Christopher S. The Lost Italian Renaissance: Humanism, Historians, and Latin's Legacy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2004 ISBN 978-0-8018-8384-2

- Celenza, Christopher S. Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer. London: Reaktion. 2017

- Celenza, Christopher S. The Intellectual World of the Italian Renaissance: Language, Philosophy, and the Search for Meaning. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2018

- Erasmus, Desiderius. "The Epicurean". In Colloquies.

- Frayle Delgado, Luis (2004). Pensamiento humanista de Francisco de Vitoria. San Esteban. ISBN 9788482601458.

- Garin, Eugenio. Science and Civic Life in the Italian Renaissance. New York: Doubleday, 1969.

- Garin, Eugenio. Italian Humanism: Philosophy and Civic Life in the Renaissance. Basil Blackwell, 1965.

- Garin, Eugenio. History of Italian Philosophy. (2 vols.) Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2008. ISBN 978-90-420-2321-5

- García Gibert, Javier (2010). La humanitas Hispana. Sobre el humanismo literario en los siglos de oro (in Spanish). Universidad de Salamanca. ISBN 9788478002023.

- Grafton, Anthony. Bring Out Your Dead: The Past as Revelation. Harvard University Press, 2004 ISBN 0-674-01597-5

- Grafton, Anthony. Worlds Made By Words: Scholarship and Community in the Modern West. Harvard University Press, 2009 ISBN 0-674-03257-8

- Hale, John. A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance. Oxford University Press, 1981, ISBN 0-500-23333-0.

- Kallendorf, Craig W, editor. Humanist Educational Treatises. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The I Tatti Renaissance Library, 2002.

- Kraye, Jill (Editor). The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar. Renaissance Thought and Its Sources. Columbia University Press, 1979 ISBN 978-0-231-04513-1

- Pico della Mirandola, Giovanni. Oration on the Dignity of Man. In Cassirer, Kristeller, and Randall, eds. Renaissance Philosophy of Man. University of Chicago Press, 1969.

- Skinner, Quentin. Renaissance Virtues: Visions of Politics: Volume II. Cambridge University Press, [2002] 2007.

- Makdisi, George. The Rise of Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West: With Special Reference to Scholasticism, 1990: Edinburgh University Press

- McManus, Stuart M. "Byzantines in the Florentine Polis: Ideology, Statecraft and Ritual during the Council of Florence". Journal of the Oxford University History Society, 6 (Michaelmas 2008/Hilary 2009).

- Melchert, Norman (2002). The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-19-517510-3.

- Nauert, Charles Garfield. Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe (New Approaches to European History). Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Plumb, J. H. ed.: The Italian Renaissance 1961, American Heritage, New York, ISBN 0-618-12738-0 (page refs from 1978 UK Penguin edn).

- Rossellini, Roberto. The Age of the Medici: Part 1, Cosimo de' Medici; Part 2, Alberti 1973. (Film Series). Criterion Collection.

- Scott, James Brown (2000). The Spanish Origin of International Law - Francisco de Vitoria and His Law of Nations. Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 9781584771104.

- Symonds, John Addington.The Renaissance in Italy. Seven Volumes. 1875–1886.

- Trinkaus, Charles (1973). "Renaissance Idea of the Dignity of Man". In Wiener, Philip P (ed.). Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-13293-8. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- Trinkaus, Charles. The Scope of Renaissance Humanism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983.

- Wind, Edgar. Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance. New York: W.W. Norton, 1969.

- Witt, Ronald. "In the footsteps of the ancients: the origins of humanism from Lovato to Bruni." Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2000

External links

[edit]- Humanism 1: An Outline by Albert Rabil, Jr.

- Paganism in the Renaissance, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Tom Healy, Charles Hope & Evelyn Welch (In Our Time, June 16, 2005)

Renaissance humanism

View on GrokipediaRenaissance humanism was a cultural and educational reform movement that originated in 14th-century Italy, centered on the recovery and study of ancient Greek and Roman texts to foster eloquence, moral philosophy, and an appreciation for human capabilities independent of strict theological frameworks.[1] It emphasized the studia humanitatis—grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and ethics—as disciplines essential for cultivating virtuous citizens, marking a departure from the abstract dialectics of medieval scholasticism toward direct engagement with primary sources (ad fontes).[2] The movement's origins trace to figures like Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), who critiqued contemporary learning and championed the rediscovery of Cicero's letters and other classical works, positioning antiquity as a model for personal and civic excellence rather than mere subservience to divine authority.[3] This revival spurred textual criticism, philology, and the collection of manuscripts, which humanists pursued amid the bustling city-states of Florence and Venice, where patronage from merchants and rulers supported academies and libraries.[4] Key proponents, including Leonardo Bruni and Coluccio Salutati, applied humanistic methods to translate and interpret Plato and Aristotle afresh, influencing governance through ideals of republican virtue and rhetorical persuasion in diplomacy and law.[5] While Renaissance humanism profoundly shaped education, art, and literature—evident in the anatomical precision of Leonardo da Vinci's studies and the civic humanism of Machiavelli's political realism—it faced critiques for its elitism, limited accessibility beyond Latin-literate males, and incomplete secularization, as many humanists reconciled classical paganism with Christian doctrine.[6] Its legacy extended northward, inspiring reformers like Erasmus, yet modern scholarship, drawing from archival evidence, cautions against overstating its rupture from medieval traditions, highlighting continuities in rhetorical training and ethical inquiry.[7]

Definition and Core Principles

Fundamental Concepts

Renaissance humanism revolved around the studia humanitatis, an educational curriculum formalized in early 15th-century Italy that prioritized the study of grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy, and history drawn from classical Latin and Greek authors.[8] This program, distinct from the logical dialectics of medieval scholasticism, emphasized practical skills in interpretation, composition, and persuasion to develop civic virtue and eloquence among the educated elite.[9] Humanists viewed these disciplines not as abstract philosophy but as tools for emulating ancient models of wisdom and conduct, fostering humanitas—a Ciceronian ideal encompassing cultivated learning, ethical benevolence, and the refinement of human character through liberal arts.[10] A cornerstone principle was ad fontes, the imperative to return to the pristine sources of antiquity by consulting original manuscripts rather than relying on corrupted medieval glosses or translations.[4] Pioneered by figures like Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374), who actively hunted for lost texts in monastic libraries, this approach sought textual accuracy and stylistic purity to revive the rhetorical prowess of Cicero and Virgil. By 1400, this method had led to critical editions and philological advances, enabling humanists to apply ancient ethics and history to contemporary governance and personal moral improvement without necessarily rejecting Christian theology.[11] Humanism posited the inherent dignity and agency of individuals, capable of self-betterment through education and imitation of classical exemplars, yet this optimism was tempered by a focus on rhetorical utility over metaphysical speculation.[12] Unlike later secular interpretations, Renaissance humanists like those in the orbit of Paul Oskar Kristeller's analyses integrated these pursuits with religious piety, aiming to harmonize pagan learning with scriptural truths for societal and personal edification.[7] This synthesis underscored humanism's role as a cultural rather than ideological movement, prioritizing eloquence as the means to virtuous action in republics and courts.Distinctions from Prior Intellectual Traditions

Renaissance humanism distinguished itself from medieval scholasticism primarily through its methodological commitment to ad fontes, or returning directly to original classical texts in Greek and Latin, rather than relying on the layered commentaries and summaries that characterized scholastic approaches. Scholastics, building on Aristotelian logic mediated through Arabic and Latin intermediaries like Averroes and Thomas Aquinas, prioritized systematic disputation and syllogistic reasoning to reconcile faith and reason within a theological framework.[14][15] In contrast, humanists such as Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374) advocated studying ancient authors like Cicero and Virgil firsthand to recover authentic wisdom, viewing scholastic intermediaries as distortions that obscured meaning.[16] This shift enabled philological advances, including textual criticism to establish accurate editions, which scholastics largely neglected in favor of doctrinal synthesis.[17] A core divergence lay in intellectual priorities: humanism elevated the studia humanitatis—encompassing grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy—to foster eloquence, civic virtue, and human potential, whereas scholasticism centered on dialectic and theology to achieve certain knowledge via university disputations.[14] Petrarch lambasted scholasticism as "arid and useless," decrying its obsession with "hair-splitting logic" and abstruse abstractions that divorced learning from practical ethics and personal moral improvement.[16] Humanists critiqued the scholastic curriculum's trivium and quadrivium, rooted in late antique Christian adaptations, as insufficient for public life; instead, they promoted rhetorical training drawn from Quintilian and Cicero to equip individuals for oratory and governance.[14] This emphasis on persuasive speech over logical certainty reflected humanism's probabilistic view of knowledge, aligned with ancient skeptics, against scholastic aspirations for infallible proofs.[14] Linguistically, humanists rejected the "barbarous" technical jargon of scholastics, which Petrarch argued impeded inner reflection and virtuous behavior by prioritizing verbal complexity over clarity and elegance.[18] They sought to revive Ciceronian Latin for its capacity to shape emotions and conduct, believing stylistic purity directly influenced moral and cultural renewal—a causal link absent in scholastic prose, which humanists deemed obstructive to meditative dialogue with antiquity.[18] While scholasticism integrated pagan philosophy subordinately to Christian doctrine, humanism's anthropocentric leanings—celebrating human dignity and agency—injected secular elements, though often synthesized with Augustinian piety, marking a departure from purely theocentric medieval paradigms.[14] These distinctions, articulated by early figures like Petrarch in works from the 1340s onward, positioned humanism not as outright rejection but as a reformative alternative amid ongoing scholastic dominance in universities.[16]Historical Development

Origins in Fourteenth-Century Italy

The origins of Renaissance humanism trace to the economic vitality and relative stability of fourteenth-century northern Italian city-states, where trade routes and craftsmanship generated wealth amid limited external disruptions like the papal Babylonian Captivity (1309–1377). Urban centers such as Florence and Milan supported populations over 100,000 by century's end, fostering patronage for scholars who accessed ancient manuscripts in monastic repositories.[19] This context enabled a departure from medieval scholasticism's theological abstractions toward direct study of classical authors, emphasizing human potential and rhetorical eloquence.[20] Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374), deemed the initiator of humanism, advanced this shift through his philological pursuits and recovery of lost texts. In 1345, at Verona's cathedral library, he discovered a damaged codex of Cicero's letters to Atticus, Brutus, and Quintus, which he personally transcribed due to its illegibility.[21] These epistles portrayed Cicero as a relatable figure with personal vulnerabilities, challenging idealized medieval views and inspiring Petrarch's focus on antiquity's moral and literary models.[21] Works like his De viris illustribus, compiling biographies of illustrious men from Greco-Roman and biblical eras, underscored continuity between pagan virtue and Christian ethics, while Secretum (c. 1342–1343) explored individual introspection via classical dialogue.[20] Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), Petrarch's collaborator, amplified these foundations by amassing Greek and Latin codices, including early translations of Homer, and lecturing on Dante to elevate vernacular literature.[22] His Decameron (1353), framing tales of human folly and resilience amid plague, drew on classical realism to critique scholastic rigidity and affirm earthly experience.[20] Their epistolary exchanges, as in Petrarch's 1362 letter defending humanistic studies against detractors, cultivated a scholarly circle prioritizing textual fidelity over allegory.[23] By century's close, Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), Florence's chancellor from 1375, embedded humanistic rhetoric in governance, collecting manuscripts and defending active civic life against monastic withdrawal.[24] These efforts crystallized humanism's core: rigorous source criticism and studia humanitatis—grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, ethics—rooted in empirical recovery of antiquity, distinct from prior deductive traditions.[20]

Fifteenth-Century Maturation in Italy

In the fifteenth century, Renaissance humanism in Italy evolved from its nascent fourteenth-century roots into a more systematic intellectual movement, marked by intensified manuscript hunting, philological rigor, and application to civic life, education, and philosophy. Humanists expanded their searches beyond Italy to monastic libraries in France and Germany, recovering key classical texts such as additional letters of Cicero and Lucretius's De rerum natura, discovered by Poggio Bracciolini in 1417 at the abbey of Fulda.[3] This era saw humanism's influence deepen in city-states like Florence, where patronage from the Medici family, beginning with Cosimo de' Medici's support in the 1430s, fostered institutions like the Platonic Academy founded in 1462.[5] Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370–1444), serving as Florence's chancellor from 1427, exemplified civic humanism by translating Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics (1416–1417) and Politics (1430s), adapting ancient political philosophy to justify republican governance and active citizenship.[25][26] His History of the Florentine People (completed posthumously in 1444) applied classical historiographical methods to contemporary events, emphasizing moral lessons from antiquity to promote virtù in public life.[25] Concurrently, Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457) pioneered historical and philological criticism, demolishing the authenticity of the Donation of Constantine in his 1440 treatise through linguistic analysis, exposing medieval forgeries and underscoring humanism's commitment to empirical textual scrutiny over scholastic authority. The century's later decades shifted toward metaphysical synthesis, with Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) translating Plato's complete dialogues (published 1484) and Plotinus's Enneads (1492), establishing Neoplatonism as a bridge between pagan antiquity and Christian theology at the Florentine Platonic Academy.[5] Ficino's Platonic Theology (1482) argued for the soul's immortality through rational demonstration, influencing a generation of thinkers by harmonizing classical wisdom with revealed religion.[5] Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) extended this syncretism in his 900 Theses (1486) and Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486), positing human free will as a microcosmic capacity to ascend divine hierarchies, drawing eclectically from Kabbalah, Hermes Trismegistus, and Zoroastrianism alongside Greco-Roman sources.[5] These efforts solidified humanism's maturation by embedding classical revival within a broader quest for universal knowledge, though tensions arose from papal scrutiny, as seen in Pico's partial condemnation by Pope Innocent VIII in 1487.[5] By century's end, humanism had permeated Italian universities and courts, training elites in studia humanitatis—grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy—elevating vernacular literature while prioritizing Latin eloquence.Spread to Northern Europe

The dissemination of Renaissance humanism to Northern Europe accelerated in the late 15th century, driven by Northern scholars' direct exposure to Italian centers of learning and the technological innovation of Johannes Gutenberg's movable-type printing press, operational by 1455 in Mainz, which produced over 200,000 books by 1500 and made classical and patristic texts widely accessible beyond elite circles. Italian humanists' works, including editions of Cicero and Virgil, circulated via printed editions from Venice and Basel, while travelers like Rudolf Agricola bridged the regions by importing manuscripts and pedagogical methods. Unlike the Italian focus on civic and secular ethics, Northern variants integrated humanism with devotional piety, prioritizing ad fontes ("to the sources") approaches to scripture and church fathers to purify Christian doctrine from scholastic accretions.[27][28] In the German-speaking lands and Low Countries, Agricola (1444–1485), after studying rhetoric and philosophy in Pavia and Ferrara during the 1470s, returned in 1479 to Heidelberg and Groningen, where he lectured on classical dialectic and composed De inventione dialectica libri III (published posthumously in 1526), emphasizing invention in argumentation over medieval logic. This laid foundations for German humanism, influencing universities like those in Leipzig and Tübingen. Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536), educated in Deventer and Paris before visiting Italy in 1506–1509, synthesized these strands in works like Enchiridion militis Christiani (1503), advocating ethical reform through philological study of Greek and Latin Bible editions; his 1516 Novum Instrumentum omne exemplified textual criticism, printing 3,000 copies initially and fueling debates on translation accuracy. Erasmus's network, spanning 1,000 correspondents, amplified humanism's reach, though his irenicism clashed with emerging Lutheran polemics.[29][30] English humanism emerged via Oxford academics who sojourned in Italy: William Grocyn (c. 1445–1519) mastered Greek under Demetrios Chalcondylas in Florence around 1488–1490, returning to teach it at Oxford by 1491 as the first such instructor there, fostering a curriculum shift toward classical languages. His associate Thomas Linacre (c. 1460–1524), similarly trained in Florence and Rome, translated Galen’s medical texts from Greek (e.g., De usu pulsuum in 1522) and established the College of Physicians in London in 1518, requiring humanist proficiency for licensure to advance empirical anatomy over astrological humoralism. These initiatives, supported by patrons like William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, prepared terrain for Tudor scholars, emphasizing rhetoric for governance and theology.[31][32] In France, humanism permeated royal courts by the 1520s under Francis I (r. 1515–1547), who imported Italian scholars and founded the Collège Royal in 1530 for vernacular and classical studies; figures like Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (c. 1455–1536) applied philology to patristics, producing a 1517 Latin Bible edition that influenced vernacular translations. This Northern adaptation, blending elitist Italian erudition with reformist zeal, totaled over 20 million printed volumes by 1500 across Europe, catalyzing literacy rates' rise from 10% to 20% in urban centers and undergirding confessional upheavals.[28]Intellectual Methods and Achievements

Revival and Study of Classical Texts

The revival of classical texts began in 14th-century Italy, driven by scholars seeking out long-forgotten Latin manuscripts preserved in monastic libraries. Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), often regarded as the initiator of this movement, actively hunted for ancient works during his travels, transcribing Cicero's Epistolae ad Atticum from a manuscript held by Verona Cathedral around 1345, which broadened access to Ciceronian rhetoric and philosophy.[33] Petrarch's efforts emphasized direct engagement with original sources over medieval glosses, fostering a preference for ad fontes—returning to the fountains of antiquity—as a methodological principle.[34] Giovanni Boccaccio complemented this by aiding in the recovery of texts like those of Quintilian and Valerius Maximus, establishing scriptoria in Florence to copy and disseminate them.[35] In the early 15th century, figures like Poggio Bracciolini intensified manuscript hunts across Europe, particularly during ecclesiastical councils. Poggio discovered the sole surviving copy of Lucretius's De rerum natura in 1417 at a German monastery library while attending the Council of Constance, rescuing the Epicurean poem on atomic theory and natural philosophy from obscurity.[36] This find, along with recoveries of works by Quintilian, Asconius Pedianus, and Columella, highlighted the haphazard survival of texts amid monastic neglect and underscored humanists' role in systematic archival expeditions.[37] By mid-century, Italian humanists such as Leonardo Bruni advanced the study through rigorous editing and Latin translations of Greek originals, prioritizing fidelity to ancient syntax over medieval interpretive layers.[38] The fall of Constantinople in 1453 accelerated the influx of Greek texts, as Byzantine émigrés like Bessarion transported manuscripts of Plato, Aristotle, and Homer to Italy, enriching libraries in Venice and Florence.[39] Humanist scholars, including Marsilio Ficino, established translation workshops, rendering Plato's dialogues into Latin by the 1480s, which integrated Neoplatonic ideas into Western thought.[40] This era saw the development of paleography and collation techniques to authenticate and emend corrupt copies, enabling more precise scholarly editions that prioritized empirical textual evidence over scholastic authority.[41] By the late 15th century, printers like Aldus Manutius produced affordable editions, such as the 1495–1496 Aristotle in Greek, democratizing access and solidifying classical study as a cornerstone of humanist education.[3]Advances in Philology and Textual Criticism

Renaissance humanists revolutionized philology—the comparative study of ancient languages and texts—and textual criticism by prioritizing empirical collation of manuscripts over scholastic dialectics, aiming to reconstruct original classical and patristic works from corrupted medieval copies. This involved meticulous comparison of variants, linguistic analysis to identify anachronisms, and rejection of interpolations based on historical and stylistic evidence, yielding more accurate editions that influenced scholarship for centuries.[42][1] A pivotal achievement was Lorenzo Valla's application of these methods in his 1440 treatise De falso credita et ementita Constantini donatione, which exposed the Donation of Constantine—a purported 4th-century imperial grant of temporal power to the papacy—as an 8th-century forgery. Valla demonstrated this through linguistic scrutiny, noting phrases absent from classical Latin, such as "satrap" (a term from Persian contexts unknown in Constantine's era), and references to cities like "Byzantium" before its renaming to Constantinople in 330 CE, alongside legal anachronisms incompatible with Roman imperial practice.[43][44] Building on such precedents, Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494) advanced textual criticism by systematically collating manuscripts and tracing error patterns to infer their interrelationships, prefiguring modern stemmatics in editions of authors like Catullus and in his Miscellanea (1489), where he corrected texts via Greek-Latin parallels and rejected medieval glosses as authentic readings.[45][46] Northern humanists extended these techniques to Christian scriptures; Desiderius Erasmus's 1516 Greek New Testament edition collated about six late manuscripts, emended Vulgate-influenced readings (e.g., rejecting the Comma Johanneum in 1 John 5:7–8 for lacking Greek attestation), and marked variants, initiating critical biblical philology despite reliance on inferior sources and rushed printing.[47][48] These efforts collectively elevated textual authenticity, enabling broader recovery of antiquity while exposing medieval fabrications.[42]Educational and Rhetorical Innovations

Humanist educators pioneered the studia humanitatis, a curriculum centered on five core disciplines—grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy, and history—designed to foster eloquence, ethical judgment, and civic virtue through immersion in classical texts rather than abstract scholastic logic.[49][8] This framework, emerging in 14th-century Italy, shifted pedagogical emphasis from medieval university disputations to practical mastery of Latin and Greek authors, aiming to shape individuals capable of moral action and persuasive discourse in republican or courtly settings.[49][50] Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), often credited as a foundational figure, championed the revival of classical literature for personal and moral formation, arguing in works like his Letter in Defense of Liberal Studies (c. 1390s, though postdating his life, reflecting his influence) that such studies elevated the soul beyond rote theology.[51] His advocacy inspired educators to prioritize imitatio, the emulation of ancient models, over mere commentary, integrating reading with composition to cultivate introspective self-improvement.[51] In practice, Vittorino da Feltre (1378–1446) exemplified these innovations by founding a school in 1423 at Casa Gioiosa in Mantua, under Gonzaga patronage, where up to 70 pupils, including noble children and orphans, received balanced training in classical languages, mathematics, and physical exercises like archery and riding, alongside religious exercises to harmonize body, mind, and piety.[52][53] This holistic method, which avoided corporal punishment in favor of motivational encouragement, produced graduates noted for their rhetorical poise and ethical resilience, influencing later European academies.[52][53] Guarino da Verona (1374–1460), operating in Ferrara from the 1420s, attracted over 200 students from Italy and abroad, including England, through a rigorous program starting with his own Rules of Latin Grammar (c. 1420s), progressing to advanced rhetoric via declamations modeled on Cicero's speeches.[54][55] His approach emphasized oral practice and textual emulation, producing scholars like his son Battista, who applied these skills in diplomacy and letters.[54][55] Rhetorically, humanists revived Cicero (106–43 BCE) and Quintilian (c. 35–100 CE) as exemplars, adapting their treatises—such as Cicero's De Oratore and Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria—to train in inventio (argument discovery), dispositio (arrangement), and elocutio (style), prioritizing natural fluency over artificial scholastic forms.[56][57] This innovation enabled humanists to deploy eloquence in political oratory and moral persuasion, as seen in the chancelleries of Florence and Venice by the 1430s, where rhetorical training directly enhanced civic participation.[56][57]Religious Context and Tensions

Synthesis with Christian Doctrine

Renaissance humanists, particularly in the Northern European tradition, developed Christian humanism as a framework to harmonize classical antiquity's emphasis on human dignity, rhetoric, and moral philosophy with core Christian tenets of faith, grace, and scriptural authority. This synthesis viewed pagan authors like Cicero and Seneca not as rivals to revelation but as providential precursors who grasped partial truths about virtue and ethics, which could aid believers in living out gospel imperatives more effectively. By the early 16th century, this approach rejected the medieval scholastic prioritization of dialectical logic in favor of ad fontes—a return to original biblical and patristic sources—using philological tools to refine doctrine and practice.[30] Desiderius Erasmus (c. 1466–1536) epitomized this integration, coining the "philosophy of Christ" to denote a piety rooted in ethical imitation of Jesus rather than ritual formalism or arid speculation. In his 1516 Novum Instrumentum omne, Erasmus applied humanist textual criticism to produce the first printed Greek New Testament alongside a revised Latin Vulgate, correcting centuries of accumulated errors to promote a scripture-centered faith accessible to the laity. He contended that classical eloquence could edify preachers and educators, fostering moral reform within the church; for instance, his Enchiridion militis Christiani (1503) urged lay Christians to cultivate Stoic-like self-discipline under divine grace, arguing that humanistic studies purified the intellect for deeper contemplation of God. Erasmus's efforts, supported by patrons like Thomas More, aimed to renew Catholicism from within, emphasizing free will and education as complements to predestination debates.[30][58] Figures like Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) advanced the synthesis through Neoplatonic theology, proposing in works such as De docta ignorantia (1440) that human reason, when humbled before divine infinity, could approximate learned ignorance—a union of rational inquiry and mystical faith. This Platonic-inflected approach influenced later humanists by framing classical metaphysics as preparatory for Trinitarian doctrine, positing an ancient wisdom tradition culminating in Christianity. Such integrations extended to education, where studia humanitatis curricula in institutions like the University of Louvain trained clergy in both Virgil and the Vulgate, yielding figures like Juan Luis Vives, who in De subventione pauperum (1526) blended Aristotelian ethics with Christian charity to advocate social welfare. Despite these efforts, the synthesis presupposed Christianity's supremacy, subordinating classical elements to revelation and often critiquing pagan polytheism as incomplete.[17]Incorporation of Pagan Elements

Renaissance humanists incorporated pagan elements primarily through the revival and selective adaptation of classical Greek and Roman philosophy, literature, and mythology, interpreting them as compatible with or preparatory for Christian revelation. This approach, known as prisca theologia, posited that ancient pagan thinkers possessed fragments of primordial divine wisdom that anticipated Christian truths.[59] Marsilio Ficino, a key Florentine humanist, exemplified this by translating Plato's complete works into Latin between 1460 and 1469, alongside Neoplatonic texts from Plotinus and Proclus, arguing in his Platonic Theology (completed 1482) that pagan philosophy demonstrated the soul's immortality through rational means, thereby supporting faith.[60] Ficino's De Christiana Religione (1463) further claimed that pagans like Hermes Trismegistus and Zoroaster held a form of true religion, integrating pagan demonology and cosmology into a Christian framework without endorsing polytheism.[60] In literature and scholarship, humanists like Giovanni Boccaccio compiled pagan mythologies, as in his Genealogia Deorum Gentilium (finished c. 1360), which organized deities from Ovid and Hesiod into a hierarchical system for allegorical use, treating myths as moral veils rather than literal beliefs.[61] Angelo Poliziano and Cristoforo Landino employed Virgilian and Ovidian narratives in commentaries to draw ethical lessons, subordinating pagan narratives to Christian virtue ethics. This philological engagement extended to textual criticism, where humanists recovered and emended works like Ovid's Metamorphoses, using them for rhetorical training and poetic inspiration while allegorizing erotic or idolatrous content to align with doctrinal orthodoxy.[62] Artistic incorporation often featured pagan motifs symbolically, as in Sandro Botticelli's Birth of Venus (c. 1485), commissioned by the Medici, which depicted the goddess emerging from the sea but interpreted Neoplatonically as the soul's beauty ascending toward divine love, blending mythological nudity with Christian humanism's emphasis on human form.[63] Such works, patronized by figures like Lorenzo de' Medici, served ideological purposes, portraying classical gods as emblems of civic virtue or intellectual harmony rather than objects of worship, though this risked theological scrutiny for potentially glorifying heathenism. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's Oration on the Dignity of Man (1486) synthesized Kabbalah, Hermeticism, and pagan philosophy to affirm human free will, claiming all traditions converged on a universal truth accessible via reason.[5] Despite these integrations, incorporation remained bounded by Christian supremacy, with humanists like Petrarch rejecting pagan immorality while praising virtues like Stoic resilience in Cicero's writings.[62]Critiques from Scholastic and Theological Perspectives

Scholastic thinkers critiqued Renaissance humanism for prioritizing rhetorical form and philological precision over substantive philosophical and theological content, viewing the humanist focus on classical eloquence as superficial and potentially misleading.[64] In debates spanning the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, scholastics such as those at the University of Louvain and the Sorbonne argued that dialectical methods, rooted in Aristotelian logic and refined by figures like Thomas Aquinas, provided demonstrative certainty essential for resolving doctrinal disputes, whereas humanist rhetoric merely persuaded without guaranteeing truth.[65] For example, critics like Jacob Latomus, a Louvain scholastic, responded to Erasmus's Antibarbari (c. 1495–1500) by defending "barbarian" scholastic terminology as precise for conveying metaphysical realities, accusing humanists of juvenile obsession with stylistic purity that neglected rigorous argumentation.[64] [66] Theological perspectives emphasized that humanism's ad fontes approach to classical texts risked eroding ecclesiastical authority by questioning scholastic syntheses of faith and reason, particularly through textual emendations that challenged traditional interpretations.[67] Louvain theologians, adhering to Thomistic orthodoxy, condemned Erasmus's 1516 Greek New Testament edition for alleged alterations to the Vulgate and promotion of doctrinal ambiguities, labeling such philological interventions as heretical innovations that undermined the church's interpretive tradition.[68] In 1519, the Louvain faculty escalated opposition by censuring humanist-influenced works for deviating from Aquinas, arguing that the revival of potentially corrupt pagan manuscripts introduced skepticism toward revealed truth.[67] Similarly, the Paris Faculty of Theology, a bastion of scholasticism, resisted Hebrew and Greek studies in the early 1500s, fearing they fostered doubts about Latin patristic sources and encouraged lay access to scripture without clerical mediation.[69] Critics from these perspectives also highlighted humanism's incorporation of pagan ethics and anthropocentric ideals as a causal vector for moral laxity, positing that uncritical admiration for Cicero or Virgil exalted human virtue over divine grace, echoing semi-Pelagian errors.[70] Theologians at conservative centers like Louvain contended that this shift diluted theocentrism, as evidenced in their 1520s attacks on Erasmus for allegedly prioritizing classical pietas over Christian piety, which they saw as fostering irreligion amid the Lutheran crisis.[66] [71] Despite humanism's Christian proponents claiming compatibility, scholastics maintained that without dialectical safeguards, the method invited relativism, as humanist emendations lacked the universality of scholastic proofs derived from first principles and authority.[64] These critiques persisted into the Reformation era, influencing condemnations that framed humanism as a precursor to Protestant disruptions by weakening institutional theology.[67]Political and Social Dimensions

Civic Humanism in Republican Contexts

Civic humanism emerged prominently in the republican environment of Florence during the early 15th century, where humanists adapted classical ideals of active citizenship and political virtue to support the city's oligarchic republic against threats from neighboring powers like Milan.[72] This strand emphasized the moral imperative for educated elites to engage in public affairs, drawing on Cicero's republican ethos and Aristotle's conception of the polity as a mixed government balanced between monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, which Bruni identified in Florence's constitution of priors and gonfaloniers elected from guilds.[72] Florentine chancellors such as Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), who served from 1375 to 1406, exemplified this by using humanistic rhetoric to rally citizens during conflicts, including the war against Giangaleazzo Visconti, portraying republican liberty as superior to monarchical tyranny.[72] Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370–1444), Salutati's protégé and Florence's chancellor from 1427 to 1444, articulated civic humanism most influentially in his Laudatio Florentinae Urbis (1403–1404), a panegyric likening Florence to ancient Athens and Rome for its equitable laws, communal spirit, and architectural beauty symbolizing civic harmony.[73] Bruni argued that true human flourishing required participation in governance, translating Aristotle's Politics into Latin (c. 1435) to equip citizens with tools for debating justice and the common good, while his History of the Florentine People (1415–1444) framed the republic's struggles as defenses of liberty against autocracy.[72] This educational focus extended to studia humanitatis curricula, prioritizing rhetoric and history over scholastic logic to train orators for assemblies and diplomacy, as seen in Bruni's advocacy for virtuous action (virtù) over monastic withdrawal.[72] In later republican thought, Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) radicalized civic humanism in his Discourses on Livy (composed c. 1517, published 1531), praising Rome's mixed constitution as a model for Florence and insisting that republics endure through citizen militias, anti-corruption laws, and periodic tumults to prevent oligarchic decay—echoing Bruni but grounding it in empirical Roman history rather than ideal praise.[72] Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540), a Florentine statesman, critiqued unchecked popular participation in his Dialogues (c. 1530) while upholding republican prudence, favoring Venice's stable oligarchy over Florence's volatile rotations of office, yet both thinkers inherited humanism's insistence on historical study for political realism.[74] These ideas reinforced Florence's guild-based elections and scrutiny of magistrates until the Medici consolidation in 1434, though civic humanist rhetoric persisted in anti-Medicean exiles' calls for restored liberty.[72] Unlike princely courts, republican contexts thus fostered humanism as a tool for collective self-rule, prioritizing communal bene comune over personal patronage.[75]Courtly and Patronage Influences

Renaissance humanism thrived in the princely courts of Italy, where rulers provided financial and institutional support to scholars, enabling the recovery, translation, and application of classical texts to courtly governance and prestige. Patrons such as dukes, marquises, and kings commissioned libraries, employed humanists as secretaries and diplomats, and integrated rhetorical and moral philosophy into princely education, often adapting ancient ideals to justify monarchical authority rather than republican virtue. This courtly patronage contrasted with civic models by emphasizing personal magnificence and dynastic legitimacy, with courts like Urbino, Ferrara, and Naples serving as intellectual hubs that disseminated humanistic learning across Europe.[76] Federico da Montefeltro, who ruled Urbino from 1444 until his death in 1482, exemplified princely patronage by tasking the bookseller and humanist Vespasiano da Bisticci with assembling a ducal library over fourteen years, which included comprehensive collections of Greek and Latin authors and was organized in a manner anticipating modern libraries. Vespasiano praised Federico's holdings as encompassing "all the good authors, both Latin and Greek," underscoring the duke's commitment to humanistic study as a complement to his military and diplomatic roles. The Urbino court attracted scholars and artists, fostering an environment where humanism informed not only literature but also the decoration of spaces like the ducal studiolo, completed around 1476, which featured classical motifs symbolizing virtuous rule.[77][78][79] In Naples, the Aragonese dynasty, ruling from 1442, supported humanists to enhance royal splendor, with Giovanni Pontano (1429–1503) serving as a key advisor and poet who authored De Splendore (c. 1498), linking classical rhetoric to the magnificence of the court under kings like Ferrante I (r. 1458–1494). The court's annual revenues exceeding 800,000 ducats facilitated such patronage, enabling Pontano to promote Neolatin literature and political theory that justified absolutist power through historical precedents from antiquity. Eleanora of Aragon (1450–1493), daughter of Ferrante, further extended this influence by corresponding with scholars and collecting antiquities.[76] The Este court in Ferrara, under Borso d'Este (r. 1452–1471) and Ercole I (r. 1471–1505), patronized humanists and commissioned works like the Palazzo Schifanoia frescoes (completed 1476), which blended astrological and classical themes to glorify ducal rule. Similarly, in Mantua, the Gonzaga family, ruling since 1328, provided humanistic training to heirs under marquises like Ludovico III (r. 1444–1478) and employed artists such as Andrea Mantegna for the Camera degli Sposi frescoes (1465–1475), where classical allusions reinforced courtly hierarchy. In Milan, Ludovico Sforza (r. 1494–1499) commissioned humanists to write regime-legitimizing histories, merging imperial Roman traditions with contemporary dynastic claims.[76] Even the papal court in Rome operated as a princely institution, with Nicholas V (r. 1447–1455) acquiring over 800 manuscripts to found the Vatican Library in 1451, employing humanists like Lorenzo Valla for textual criticism and diplomatic service. Successors such as Pius II (Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, r. 1458–1464), a humanist poet himself, continued this by sponsoring academies and writings that harmonized pagan classics with papal authority. Such patronage ensured humanism's survival amid political fragmentation, though it often prioritized rhetorical display for power consolidation over unadulterated scholarly pursuit.[62]Effects on Individual Agency and Society