Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

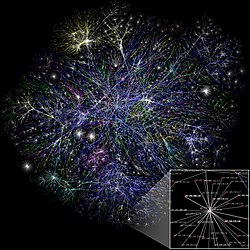

Computer network

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

| Operating systems |

|---|

|

| Common features |

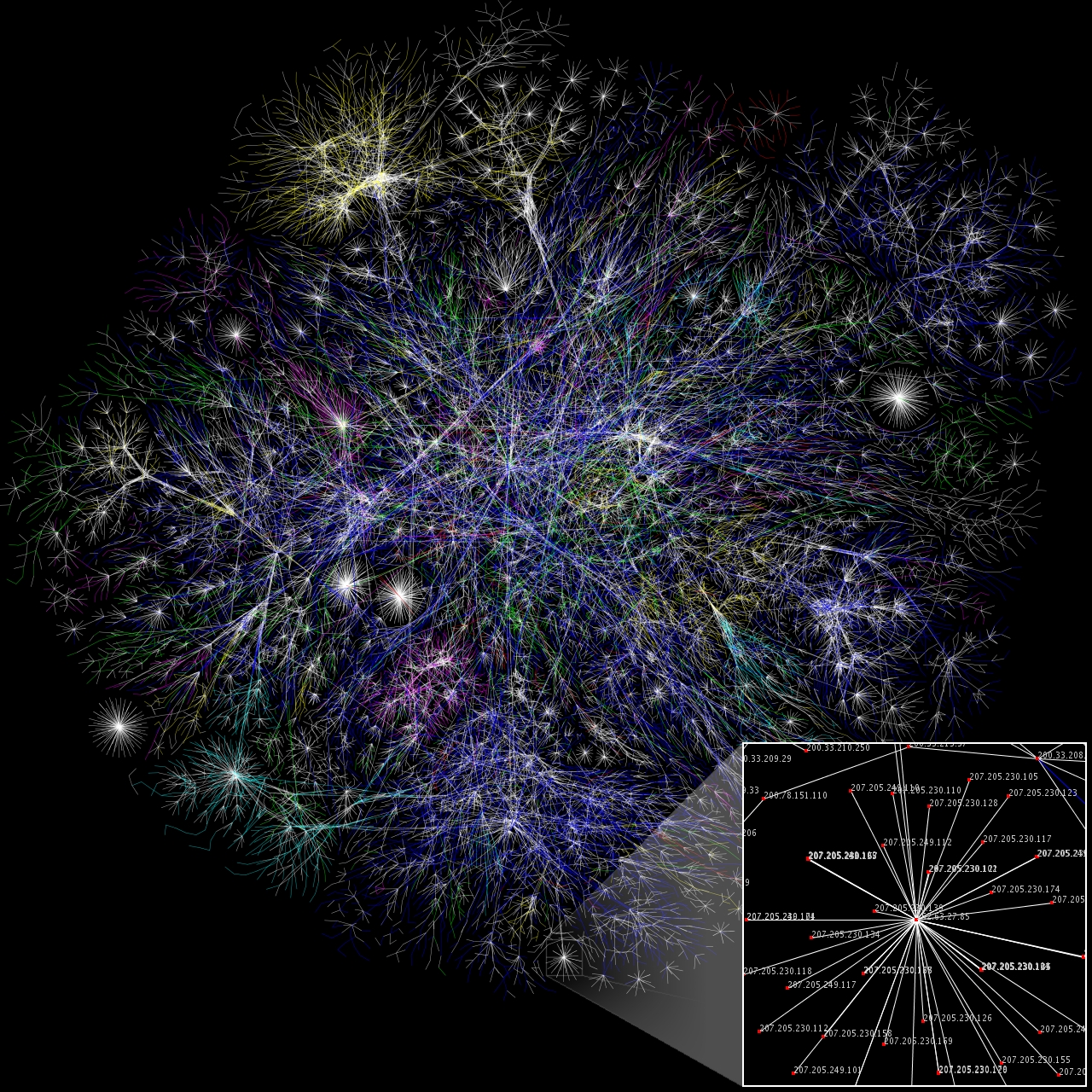

In computer science, computer engineering, and telecommunications, a network is a group of communicating computers and peripherals known as hosts, which communicate data to other hosts via communication protocols, as facilitated by networking hardware.

Within a computer network, hosts are identified by network addresses, which allow network software such as the Internet Protocol to locate and identify hosts. Hosts may also have hostnames, memorable labels for the host nodes, which are rarely changed after initial assignment. The physical medium that supports information exchange includes wired media like copper cables, optical fibers, and wireless radio-frequency media. The arrangement of hosts and hardware within a network architecture is known as the network topology.[1][2]

The first computer network was created in 1940 when George Stibitz connected a terminal at Dartmouth to his Complex Number Calculator at Bell Labs in New York. Today, almost all computers are connected to a computer network, such as the global Internet or embedded networks such as those found in many modern electronic devices. Many applications have only limited functionality unless they are connected to a network. Networks support applications and services, such as access to the World Wide Web, digital video and audio, application and storage servers, printers, and email and instant messaging applications.

History

[edit]Early origins (1940 – 1960s)

[edit]In 1940, George Stibitz of Bell Labs connected a teletype at Dartmouth to a Bell Labs computer running his Complex Number Calculator to demonstrate the use of computers at long distance.[3][4] This was the first real-time, remote use of a computing machine.[3]

In the late 1950s, a network of computers was built for the U.S. military Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) radar system[5][6][7] using the Bell 101 modem. It was the first commercial modem for computers, released by AT&T Corporation in 1958. The modem allowed digital data to be transmitted over regular unconditioned telephone lines at a speed of 110 bits per second (bit/s). In 1959, Christopher Strachey filed a patent application for time-sharing in the United Kingdom and John McCarthy initiated the first project to implement time-sharing of user programs at MIT.[8][9][10][11] Strachey passed the concept on to J. C. R. Licklider at the inaugural UNESCO Information Processing Conference in Paris that year.[12] McCarthy was instrumental in the creation of three of the earliest time-sharing systems (the Compatible Time-Sharing System in 1961, the BBN Time-Sharing System in 1962, and the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System in 1963).

In 1959, Anatoly Kitov proposed to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union a detailed plan for the re-organization of the control of the Soviet armed forces and of the Soviet economy on the basis of a network of computing centers.[13] Kitov's proposal was rejected, as later was the 1962 OGAS economy management network project.[14]

During the 1960s,[15][16] Paul Baran and Donald Davies independently invented the concept of packet switching for data communication between computers over a network.[17][18][19][20] Baran's work addressed adaptive routing of message blocks across a distributed network, but did not include routers with software switches, nor the idea that users, rather than the network itself, would provide the reliability.[21][22][23][24] Davies' hierarchical network design included high-speed routers, communication protocols and the essence of the end-to-end principle.[25][26][27][28] The NPL network, a local area network at the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom), pioneered the implementation of the concept in 1968-69 using 768 kbit/s links.[29][27][30] Both Baran's and Davies' inventions were seminal contributions that influenced the development of computer networks.[31][32][33][34]

ARPANET (1969 – 1974)

[edit]In 1962 and 1963, J. C. R. Licklider sent a series of memos to office colleagues discussing the concept of the "Intergalactic Computer Network", a computer network intended to allow general communications among computer users. This ultimately became the basis for the ARPANET, which began in 1969.[35] That year, the first four nodes of the ARPANET were connected using 50 kbit/s circuits between the University of California at Los Angeles, the Stanford Research Institute, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and the University of Utah.[35][36] Designed principally by Bob Kahn, the network's routing, flow control, software design and network control were developed by the IMP team working for Bolt Beranek & Newman.[37][38][39] In the early 1970s, Leonard Kleinrock carried out mathematical work to model the performance of packet-switched networks, which underpinned the development of the ARPANET.[40][41] His theoretical work on hierarchical routing in the late 1970s with student Farouk Kamoun remains critical to the operation of the Internet today.[42][43]

In 1973, Peter Kirstein put internetworking into practice at University College London (UCL), connecting the ARPANET to British academic networks, the first international heterogeneous computer network.[44][45] That same year, Robert Metcalfe wrote a formal memo at Xerox PARC describing Ethernet,[46] a local area networking system he created with David Boggs.[47] It was inspired by the packet radio ALOHAnet, started by Norman Abramson and Franklin Kuo at the University of Hawaii in the late 1960s.[48][49] Metcalfe and Boggs, with John Shoch and Edward Taft, also developed the PARC Universal Packet for internetworking.[50] That year, the French CYCLADES network, directed by Louis Pouzin was the first to make the hosts responsible for the reliable delivery of data, rather than this being a centralized service of the network itself.[51]

The internet (1974 – present)

[edit]In 1974, Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn published their seminal 1974 paper on internetworking, A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication.[52] Later that year, Cerf, Yogen Dalal, and Carl Sunshine wrote the first Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) specification, RFC 675, coining the term Internet as a shorthand for internetworking.[53] In July 1976, Metcalfe and Boggs published their paper "Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks"[54] and in December 1977, together with Butler Lampson and Charles P. Thacker, they received U.S. patent 4063220A for their invention.[55][56]

In 1976, John Murphy of Datapoint Corporation created ARCNET, a token-passing network first used to share storage devices. In 1979, Robert Metcalfe pursued making Ethernet an open standard.[57] In 1980, Ethernet was upgraded from the original 2.94 Mbit/s protocol to the 10 Mbit/s protocol, which was developed by Ron Crane, Bob Garner, Roy Ogus,[58] Hal Murray, Dave Redell and Yogen Dalal.[59] In 1986, the National Science Foundation (NSF) launched the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNET) as a general-purpose research network connecting various NSF-funded sites to each other and to regional research and education networks.[35]

In 1995, the transmission speed capacity for Ethernet increased from 10 Mbit/s to 100 Mbit/s. By 1998, Ethernet supported transmission speeds of 1 Gbit/s. Subsequently, higher speeds of up to 800 Gbit/s were added (as of 2025[update]). The scaling of Ethernet has been a contributing factor to its continued use.[57] In the 1980s and 1990s, as embedded systems were becoming increasingly important in factories, cars, and airplanes, network protocols were developed to allow the embedded computers to communicate. In the late 1990s and 2000s, ubiquitous computing and an Internet of Things became popular.[60][61]

Commercial usage

[edit]In 1960, the commercial airline reservation system semi-automatic business research environment (SABRE) went online with two connected mainframes. In 1965, Western Electric introduced the first widely used telephone switch that implemented computer control in the switching fabric. In 1972, commercial services were first deployed on experimental public data networks in Europe.[62][63] Public data networks in Europe, North America and Japan began using X.25 in the late 1970s and interconnected with X.75.[18] This underlying infrastructure was used for expanding TCP/IP networks in the 1980s.[64] In 1977, the first long-distance fiber network was deployed by GTE in Long Beach, California.

Hardware

[edit]Network links

[edit]The transmission media used to link devices to form a computer network include electrical cable, optical fiber, and free space. In the OSI model, the software to handle the media is defined at layers 1 and 2 — the physical layer and the data link layer. Common examples of networking technologies include:

- Ethernet is a widely adopted family of networking technologies that use copper and fiber media in local area networks (LAN). The media and protocol standards that enable communication between networked devices over Ethernet are defined by IEEE 802.3.

- Wireless LAN standards, which use radio waves. Some standards use infrared signals as a transmission medium.

- Power line communication uses a building's power cabling to transmit data.

Wired

[edit]

The following classes of wired technologies are used in computer networking.

- Coaxial cable is widely used for cable television systems, office buildings, and other work-sites for local area networks. Transmission speed ranges from 200 million bits per second to more than 500 million bits per second.[citation needed]

- ITU-T G.hn technology uses existing home wiring (coaxial cable, phone lines and power lines) to create a high-speed local area network.

- Twisted pair cabling is used for wired Ethernet and other standards. It typically consists of 4 pairs of copper cabling that can be utilized for both voice and data transmission. The use of two wires twisted together helps to reduce crosstalk and electromagnetic induction. The transmission speed ranges from 2 Mbit/s to 10 Gbit/s. Twisted pair cabling comes in two forms: unshielded twisted pair (UTP) and shielded twisted-pair (STP). Each form comes in several category ratings, designed for use in various scenarios.

- An optical fiber is a glass fiber that carries pulses of light that represent data via lasers and optical amplifiers. Some advantages of optical fibers over metal wires are very low transmission loss and immunity to electrical interference. Using dense wave division multiplexing, optical fibers can simultaneously carry multiple streams of data on different wavelengths of light, which greatly increases the rate that data can be sent to up to trillions of bits per second. Optic fibers can be used for long runs of cable carrying very high data rates, and are used for undersea communications cables to interconnect continents. There are two basic types of fiber optics, single-mode optical fiber (SMF) and multi-mode optical fiber (MMF).[65]

Wireless

[edit]

Network connections can be established wirelessly using radio or other electromagnetic means of communication.

- Terrestrial microwave – Terrestrial microwave communication uses Earth-based transmitters and receivers resembling satellite dishes. Terrestrial microwaves are in the low gigahertz range, which limits all communications to line-of-sight. Relay stations are spaced approximately 40 miles (64 km) apart.

- Communications satellites – Satellites also communicate via microwave. The satellites are stationed in space, typically in geosynchronous orbit 35,400 km (22,000 mi) above the equator. These Earth-orbiting systems are capable of receiving and relaying voice, data, and TV signals.

- Cellular networks use several radio communications technologies. The systems divide the region covered into multiple geographic areas. Each area is served by a low-power transceiver.

- Radio and spread spectrum technologies – Wireless LANs use a high-frequency radio technology similar to digital cellular. Wireless LANs use spread spectrum technology to enable communication between multiple devices in a limited area. IEEE 802.11 defines a common flavor of open-standards wireless radio-wave technology known as Wi-Fi.

- Free-space optical communication uses visible or invisible light for communications. In most cases, line-of-sight propagation is used, which limits the physical positioning of communicating devices.

- Extending the Internet to interplanetary dimensions via radio waves and optical means, the Interplanetary Internet.[66]

- IP over Avian Carriers was a humorous April fool's Request for Comments, issued as RFC 1149. It was implemented in real life in 2001.[67]

The last two cases have a large round-trip delay time, which gives slow two-way communication but does not prevent sending large amounts of information (they can have high throughput).

Network nodes

[edit]Apart from any physical transmission media, networks are built from additional basic system building blocks, such as network interface controllers, repeaters, hubs, bridges, switches, routers, modems, and firewalls. Any particular piece of equipment will frequently contain multiple building blocks and so may perform multiple functions.

Network interfaces

[edit]

A network interface controller (NIC) is computer hardware that connects the computer to the network media and has the ability to process low-level network information. For example, the NIC may have a connector for plugging in a cable, or an aerial for wireless transmission and reception, and the associated circuitry.

In Ethernet networks, each NIC has a unique Media Access Control (MAC) address—usually stored in the controller's permanent memory. To avoid address conflicts between network devices, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) maintains and administers MAC address uniqueness. The size of an Ethernet MAC address is six octets. The three most significant octets are reserved to identify NIC manufacturers. These manufacturers, using only their assigned prefixes, uniquely assign the three least-significant octets of every Ethernet interface they produce.

Repeaters and hubs

[edit]A repeater is an electronic device that receives a network signal, cleans it of unnecessary noise and regenerates it. The signal is retransmitted at a higher power level, or to the other side of obstruction so that the signal can cover longer distances without degradation. In most twisted-pair Ethernet configurations, repeaters are required for cable that runs longer than 100 meters. With fiber optics, repeaters can be tens or even hundreds of kilometers apart.

Repeaters work on the physical layer of the OSI model but still require a small amount of time to regenerate the signal. This can cause a propagation delay that affects network performance and may affect proper function. As a result, many network architectures limit the number of repeaters used in a network, e.g., the Ethernet 5-4-3 rule.

An Ethernet repeater with multiple ports is known as an Ethernet hub. In addition to reconditioning and distributing network signals, a repeater hub assists with collision detection and fault isolation for the network. Hubs and repeaters in LANs have been largely obsoleted by modern network switches.

Bridges and switches

[edit]Network bridges and network switches are distinct from a hub in that they only forward frames to the ports involved in the communication whereas a hub forwards to all ports. Bridges only have two ports but a switch can be thought of as a multi-port bridge. Switches normally have numerous ports, facilitating a star topology for devices, and for cascading additional switches.

Bridges and switches operate at the data link layer (layer 2) of the OSI model and bridge traffic between two or more network segments to form a single local network. Both are devices that forward frames of data between ports based on the destination MAC address in each frame.[68] They learn the association of physical ports to MAC addresses by examining the source addresses of received frames and only forward the frame when necessary. If an unknown destination MAC is targeted, the device broadcasts the request to all ports except the source, and discovers the location from the reply.

Bridges and switches divide the network's collision domain but maintain a single broadcast domain. Network segmentation through bridging and switching helps break down a large, congested network into an aggregation of smaller, more efficient networks.

Routers

[edit]

A router is an internetworking device that forwards packets between networks by processing the addressing or routing information included in the packet. The routing information is often processed in conjunction with the routing table. A router uses its routing table to determine where to forward packets and does not require broadcasting packets which is inefficient for very big networks.

Modems

[edit]Modems (modulator-demodulator) are used to connect network nodes via wire not originally designed for digital network traffic, or for wireless. To do this one or more carrier signals are modulated by the digital signal to produce an analog signal that can be tailored to give the required properties for transmission. Early modems modulated audio signals sent over a standard voice telephone line. Modems are still commonly used for telephone lines, using a digital subscriber line technology and cable television systems using DOCSIS technology.

Firewalls

[edit]

A firewall is a network device or software for controlling network security and access rules. Firewalls are inserted in connections between secure internal networks and potentially insecure external networks such as the Internet. Firewalls are typically configured to reject access requests from unrecognized sources while allowing actions from recognized ones. The vital role firewalls play in network security grows in parallel with the constant increase in cyber attacks.

Communication

[edit]Protocols

[edit]

A communication protocol is a set of rules for exchanging information over a network. Communication protocols have various characteristics, such as being connection-oriented or connectionless, or using circuit switching or packet switching.

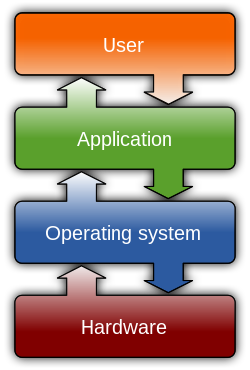

In a protocol stack, often constructed per the OSI model, communications functions are divided into protocol layers, where each layer leverages the services of the layer below it until the lowest layer controls the hardware that sends information across the media. The use of protocol layering is ubiquitous across the field of computer networking. An important example of a protocol stack is HTTP, the World Wide Web protocol. HTTP runs over TCP over IP, the Internet protocols, which in turn run over IEEE 802.11, the Wi-Fi protocol. This stack is used between a wireless router and a personal computer when accessing the web.

Packets

[edit]

Most modern computer networks use protocols based on packet-mode transmission. A network packet is a formatted unit of data carried by a packet-switched network.

Packets consist of two types of data: control information and user data (payload). The control information provides data the network needs to deliver the user data, for example, source and destination network addresses, error detection codes, and sequencing information. Typically, control information is found in packet headers and trailers, with payload data in between.

With packets, the bandwidth of the transmission medium can be better shared among users than if the network were circuit switched. When one user is not sending packets, the link can be filled with packets from other users, and so the cost can be shared, with relatively little interference, provided the link is not overused. Often the route a packet needs to take through a network is not immediately available. In that case, the packet is queued and waits until a link is free.

The physical link technologies of packet networks typically limit the size of packets to a certain maximum transmission unit (MTU). A longer message may be fragmented before it is transferred and once the packets arrive, they are reassembled to construct the original message.

Common protocols

[edit]Internet protocol suite

[edit]The Internet protocol suite, also called TCP/IP, is the foundation of all modern networking. It offers connection-less and connection-oriented services over an inherently unreliable network traversed by datagram transmission using Internet protocol (IP). At its core, the protocol suite defines the addressing, identification, and routing specifications for Internet Protocol Version 4 (IPv4) and for IPv6, the next generation of the protocol with a much enlarged addressing capability. The Internet protocol suite is the defining set of protocols for the Internet.[69]

IEEE 802

[edit]IEEE 802 is a family of IEEE standards dealing with local area networks and metropolitan area networks. The complete IEEE 802 protocol suite provides a diverse set of networking capabilities. The protocols have a flat addressing scheme. They operate mostly at layers 1 and 2 of the OSI model.

For example, MAC bridging (IEEE 802.1D) deals with the routing of Ethernet packets using a Spanning Tree Protocol. IEEE 802.1Q describes VLANs, and IEEE 802.1X defines a port-based network access control protocol, which forms the basis for the authentication mechanisms used in VLANs[70] (but it is also found in WLANs[71]) – it is what the home user sees when the user has to enter a "wireless access key".

Ethernet

[edit]Ethernet is a family of technologies used in wired LANs. It is described by a set of standards together called IEEE 802.3 published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Wireless LAN

[edit]Wireless LAN based on the IEEE 802.11 standards, also widely known as WLAN or WiFi, is probably the most well-known member of the IEEE 802 protocol family for home users today. IEEE 802.11 shares many properties with wired Ethernet.

SONET/SDH

[edit]Synchronous optical networking (SONET) and Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH) are standardized multiplexing protocols that transfer multiple digital bit streams over optical fiber using lasers. They were originally designed to transport circuit mode communications from a variety of different sources, primarily to support circuit-switched digital telephony. However, due to its protocol neutrality and transport-oriented features, SONET/SDH also was the obvious choice for transporting Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) frames.

Asynchronous Transfer Mode

[edit]Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) is a switching technique for telecommunication networks. It uses asynchronous time-division multiplexing and encodes data into small, fixed-sized cells. This differs from other protocols such as the Internet protocol suite or Ethernet that use variable-sized packets or frames. ATM has similarities with both circuit and packet switched networking. This makes it a good choice for a network that must handle both traditional high-throughput data traffic, and real-time, low-latency content such as voice and video. ATM uses a connection-oriented model in which a virtual circuit must be established between two endpoints before the actual data exchange begins.

ATM still plays a role in the last mile, which is the connection between an Internet service provider and the home user.[72][needs update]

Cellular standards

[edit]There are a number of different digital cellular standards, including: Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), General Packet Radio Service (GPRS), cdmaOne, CDMA2000, Evolution-Data Optimized (EV-DO), Enhanced Data Rates for GSM Evolution (EDGE), Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS), Digital Enhanced Cordless Telecommunications (DECT), Digital AMPS (IS-136/TDMA), and Integrated Digital Enhanced Network (iDEN).[73]

Routing

[edit]

Routing is the process of selecting network paths to carry network traffic. Routing is performed for many kinds of networks, including circuit switching networks and packet switched networks.

In packet-switched networks, routing protocols direct packet forwarding through intermediate nodes. Intermediate nodes are typically network hardware devices such as routers, bridges, gateways, firewalls, or switches. General-purpose computers can also forward packets and perform routing, though because they lack specialized hardware, may offer limited performance. The routing process directs forwarding on the basis of routing tables, which maintain a record of the routes to various network destinations. Most routing algorithms use only one network path at a time. Multipath routing techniques enable the use of multiple alternative paths.

Routing can be contrasted with bridging in its assumption that network addresses are structured and that similar addresses imply proximity within the network. Structured addresses allow a single routing table entry to represent the route to a group of devices. In large networks, the structured addressing used by routers outperforms unstructured addressing used by bridging. Structured IP addresses are used on the Internet. Unstructured MAC addresses are used for bridging on Ethernet and similar local area networks.

Architecture

[edit]

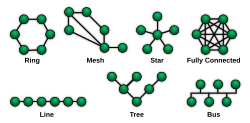

Topology

[edit]The physical or geographic locations of network nodes and links generally have relatively little effect on a network, but the topology of interconnections of a network can significantly affect its throughput and reliability. With many technologies, such as bus or star networks, a single failure can cause the network to fail entirely. In general, the more interconnections there are, the more robust the network is; but the more expensive it is to install. Therefore, most network diagrams are arranged by their network topology which is the map of logical interconnections of network hosts.

Common topologies are:

- Bus network: all nodes are connected to a common medium along this medium. This was the layout used in the original Ethernet, called 10BASE5 and 10BASE2. This is still a common topology on the data link layer, although modern physical layer variants use point-to-point links instead, forming a star or a tree.

- Star network: all nodes are connected to a special central node. This is the typical layout found in a small switched Ethernet LAN, where each client connects to a central network switch, and logically in a wireless LAN, where each wireless client associates with the central wireless access point.

- Ring network: each node is connected to its left and right neighbor node, such that all nodes are connected and that each node can reach each other node by traversing nodes left- or rightwards. Token ring networks, and the Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI), made use of such a topology.

- Mesh network: each node is connected to an arbitrary number of neighbors in such a way that there is at least one traversal from any node to any other.

- Fully connected network: each node is connected to every other node in the network.

- Tree network: nodes are arranged hierarchically. This is the natural topology for a larger Ethernet network with multiple switches and without redundant meshing.

The physical layout of the nodes in a network may not necessarily reflect the network topology. As an example, with FDDI, the network topology is a ring, but the physical topology is often a star, because all neighboring connections can be routed via a central physical location. Physical layout is not completely irrelevant, however, as common ducting and equipment locations can represent single points of failure due to issues like fires, power failures and flooding.

Overlay network

[edit]

An overlay network is a virtual network that is built on top of another network. Nodes in the overlay network are connected by virtual or logical links. Each link corresponds to a path, perhaps through many physical links, in the underlying network. The topology of the overlay network may (and often does) differ from that of the underlying one. For example, many peer-to-peer networks are overlay networks. They are organized as nodes of a virtual system of links that run on top of the Internet.[74]

Overlay networks have been used since the early days of networking, back when computers were connected via telephone lines using modems, even before data networks were developed.

The most striking example of an overlay network is the Internet itself. The Internet itself was initially built as an overlay on the telephone network.[74] Even today, each Internet node can communicate with virtually any other through an underlying mesh of sub-networks of wildly different topologies and technologies. Address resolution and routing are the means that allow mapping of a fully connected IP overlay network to its underlying network.

Another example of an overlay network is a distributed hash table, which maps keys to nodes in the network. In this case, the underlying network is an IP network, and the overlay network is a table (actually a map) indexed by keys.

Overlay networks have also been proposed as a way to improve Internet routing, such as through quality of service guarantees achieve higher-quality streaming media. Previous proposals such as IntServ, DiffServ, and IP multicast have not seen wide acceptance largely because they require modification of all routers in the network.[citation needed] On the other hand, an overlay network can be incrementally deployed on end-hosts running the overlay protocol software, without cooperation from Internet service providers. The overlay network has no control over how packets are routed in the underlying network between two overlay nodes, but it can control, for example, the sequence of overlay nodes that a message traverses before it reaches its destination[citation needed].

For example, Akamai Technologies manages an overlay network that provides reliable, efficient content delivery (a kind of multicast). Academic research includes end system multicast,[75] resilient routing and quality of service studies, among others.

Scale

[edit]| Computer network types by scale |

|---|

|

Networks may be characterized by many properties or features, such as physical capacity, organizational purpose, user authorization, access rights, and others. Another distinct classification method is that of the physical extent or geographic scale.

Nanoscale network

[edit]A nanoscale network has key components implemented at the nanoscale, including message carriers, and leverages physical principles that differ from macroscale communication mechanisms. Nanoscale communication extends communication to very small sensors and actuators such as those found in biological systems and also tends to operate in environments that would be too harsh for other communication techniques.[76]

Personal area network

[edit]A personal area network (PAN) is a computer network used for communication among computers and different information technological devices close to one person. Some examples of devices that are used in a PAN are personal computers, printers, fax machines, telephones, PDAs, scanners, and video game consoles. A PAN may include wired and wireless devices. The reach of a PAN typically extends to 10 meters.[77] A wired PAN is usually constructed with USB and FireWire connections while technologies such as Bluetooth and infrared communication typically form a wireless PAN.

Local area network

[edit]A local area network (LAN) is a network that connects computers and devices in a limited geographical area such as a home, school, office building, or closely positioned group of buildings. Wired LANs are most commonly based on Ethernet technology. Other networking technologies such as ITU-T G.hn also provide a way to create a wired LAN using existing wiring, such as coaxial cables, telephone lines, and power lines.[78]

A LAN can be connected to a wide area network (WAN) using a router. The defining characteristics of a LAN, in contrast to a WAN, include higher data transfer rates, limited geographic range, and lack of reliance on leased lines to provide connectivity.[citation needed] Current Ethernet or other IEEE 802.3 LAN technologies operate at data transfer rates up to and in excess of 100 Gbit/s,[79] standardized by IEEE in 2010.

- A home area network (HAN) is a residential LAN used for communication between digital devices typically deployed in the home, usually a small number of personal computers and accessories, such as printers and mobile computing devices. An important function is the sharing of Internet access, often a broadband service through a cable Internet access or digital subscriber line (DSL) provider.

- A storage area network (SAN) is a dedicated network that provides access to consolidated, block-level data storage. SANs are primarily used to make storage devices, such as disk arrays, tape libraries, and optical jukeboxes, accessible to servers so that the storage appears as locally attached devices to the operating system. A SAN typically has its own network of storage devices that are generally not accessible through the local area network by other devices. The cost and complexity of SANs dropped in the early 2000s to levels allowing wider adoption across both enterprise and small to medium-sized business environments.[citation needed]

Campus area network

[edit]A campus area network (CAN) is made up of an interconnection of LANs within a limited geographical area. The networking equipment (switches, routers) and transmission media (optical fiber, Cat5 cabling, etc.) are almost entirely owned by the campus tenant or owner (an enterprise, university, government, etc.). For example, a university campus network is likely to link a variety of campus buildings to connect academic colleges or departments, the library, and student residence halls.

Backbone network

[edit]A backbone network is part of a computer network infrastructure that provides a path for the exchange of information between different LANs or subnetworks. A backbone can tie together diverse networks within the same building, across different buildings, or over a wide area. When designing a network backbone, network performance and network congestion are critical factors to take into account. Normally, the backbone network's capacity is greater than that of the individual networks connected to it.

For example, a large company might implement a backbone network to connect departments that are located around the world. The equipment that ties together the departmental networks constitutes the network backbone. Another example of a backbone network is the Internet backbone, which is a massive, global system of fiber-optic cable and optical networking that carry the bulk of data between wide area networks (WANs), metro, regional, national and transoceanic networks.

- An enterprise private network or intranet is a network that a single organization builds to interconnect its office locations (e.g., production sites, head offices, remote offices, shops) so they can share computer resources.

Metropolitan area network

[edit]A metropolitan area network (MAN) is a large computer network that interconnects users with computer resources in a geographic region of the size of a metropolitan area.

Wide area network

[edit]A wide area network (WAN) is a computer network that covers a large geographic area such as a city, country, or spans even intercontinental distances. A WAN uses a communications channel that combines many types of media such as telephone lines, cables, and airwaves. A WAN often makes use of transmission facilities provided by common carriers, such as telephone companies. WAN technologies generally function at the lower three layers of the OSI model: the physical layer, the data link layer, and the network layer.

Global area network

[edit]A global area network (GAN) is a network used for supporting mobile users across an arbitrary number of wireless LANs, satellite coverage areas, etc. The key challenge in mobile communications is handing off communications from one local coverage area to the next. In IEEE Project 802, this involves a succession of terrestrial wireless LANs.[80]

Scope

[edit]An intranet is a community of interest under private administration usually by an enterprise, and is only accessible by authorized users (e.g. employees).[81] Intranets do not have to be connected to the Internet, but generally have a limited connection. An extranet is an extension of an intranet that allows secure communications to users outside of the intranet (e.g. business partners, customers).[81]

Networks are typically managed by the organizations that own them. Private enterprise networks may use a combination of intranets and extranets. They may also provide network access to the Internet, which has no single owner and permits virtually unlimited global connectivity.

Intranet

[edit]An intranet is a set of networks that are under the control of a single administrative entity. An intranet typically uses the Internet Protocol and IP-based tools such as web browsers and file transfer applications. The administrative entity limits the use of the intranet to its authorized users. Most commonly, an intranet is the internal LAN of an organization. A large intranet typically has at least one web server to provide users with organizational information.

Extranet

[edit]An extranet is a network that is under the administrative control of a single organization but supports a limited connection to a specific external network. For example, an organization may provide access to some aspects of its intranet to share data with its business partners or customers. These other entities are not necessarily trusted from a security standpoint. The network connection to an extranet is often, but not always, implemented via WAN technology.

Internet

[edit]

An internetwork is the connection of multiple different types of computer networks to form a single computer network using higher-layer network protocols and connecting them together using routers.

The Internet is the largest example of internetwork. It is a global system of interconnected governmental, academic, corporate, public, and private computer networks. It is based on the networking technologies of the Internet protocol suite. It is the successor of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) developed by DARPA of the United States Department of Defense. The Internet utilizes copper communications and an optical networking backbone to enable the World Wide Web (WWW), the Internet of things, video transfer, and a broad range of information services.

Participants on the Internet use a diverse array of methods of several hundred documented, and often standardized, protocols compatible with the Internet protocol suite and the IP addressing system administered by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority and address registries. Service providers and large enterprises exchange information about the reachability of their address spaces through the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), forming a redundant worldwide mesh of transmission paths.

Darknet

[edit]A darknet is an overlay network, typically running on the Internet, that is only accessible through specialized software. It is an anonymizing network where connections are made only between trusted peers — sometimes called friends (F2F)[83] — using non-standard protocols and ports.

Darknets are distinct from other distributed peer-to-peer networks as sharing is anonymous (that is, IP addresses are not publicly shared), and therefore users can communicate with little fear of governmental or corporate interference.[84]

Virtual private networks

[edit]A virtual private network (VPN) is an overlay network in which some of the links between nodes are carried by open connections or virtual circuits in some larger network (e.g., the Internet) instead of by physical wires. The data link layer protocols of the virtual network are said to be tunneled through the larger network. One common application is secure communications through the public Internet, but a VPN need not have explicit security features, such as authentication or content encryption. VPNs, for example, can be used to separate the traffic of different user communities over an underlying network with strong security features.

Services

[edit]Network services are applications hosted by servers on a computer network, to provide some functionality for members or users of the network, or to help the network itself to operate.

The World Wide Web, E-mail,[85] printing and network file sharing are examples of well-known network services. Network services such as Domain Name System (DNS) give names for IP and MAC addresses (people remember names like nm.lan better than numbers like 210.121.67.18),[86] and Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) to ensure that the equipment on the network has a valid IP address.[87]

Services are usually based on a service protocol that defines the format and sequencing of messages between clients and servers of that network service.

Performance

[edit]Bandwidth

[edit]Bandwidth in bit/s may refer to consumed bandwidth, corresponding to achieved throughput or goodput, i.e., the average rate of successful data transfer through a communication path. The throughput is affected by processes such as bandwidth shaping, bandwidth management, bandwidth throttling, bandwidth cap and bandwidth allocation (using, for example, bandwidth allocation protocol and dynamic bandwidth allocation).

Network delay

[edit]Network delay is a design and performance characteristic of a telecommunications network. It specifies the latency for a bit of data to travel across the network from one communication endpoint to another. Delay may differ slightly, depending on the location of the specific pair of communicating endpoints. Engineers usually report both the maximum and average delay, and they divide the delay into several components, the sum of which is the total delay:

- Processing delay – time it takes a router to process the packet header

- Queuing delay – time the packet spends in routing queues

- Transmission delay – time it takes to push the packet's bits onto the link

- Propagation delay – time for a signal to propagate through the media

A certain minimum level of delay is experienced by signals due to the time it takes to transmit a packet serially through a link. This delay is extended by more variable levels of delay due to network congestion. IP network delays can range from less than a microsecond to several hundred milliseconds.

Performance metrics

[edit]The parameters that affect performance typically can include throughput, jitter, bit error rate and latency.

In circuit-switched networks, network performance is synonymous with the grade of service. The number of rejected calls is a measure of how well the network is performing under heavy traffic loads.[88] Other types of performance measures can include the level of noise and echo.

In an Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) network, performance can be measured by line rate, quality of service (QoS), data throughput, connect time, stability, technology, modulation technique, and modem enhancements.[89][verification needed][full citation needed]

There are many ways to measure the performance of a network, as each network is different in nature and design. Performance can also be modeled instead of measured. For example, state transition diagrams are often used to model queuing performance in a circuit-switched network. The network planner uses these diagrams to analyze how the network performs in each state, ensuring that the network is optimally designed.[90]

Network congestion

[edit]Network congestion occurs when a link or node is subjected to a greater data load than it is rated for, resulting in a deterioration of its quality of service. When networks are congested and queues become too full, packets have to be discarded, and participants must rely on retransmission to maintain reliable communications. Typical effects of congestion include queueing delay, packet loss or the blocking of new connections. A consequence of these latter two is that incremental increases in offered load lead either to only a small increase in the network throughput or to a potential reduction in network throughput.

Network protocols that use aggressive retransmissions to compensate for packet loss tend to keep systems in a state of network congestion even after the initial load is reduced to a level that would not normally induce network congestion. Thus, networks using these protocols can exhibit two stable states under the same level of load. The stable state with low throughput is known as congestive collapse.

Modern networks use congestion control, congestion avoidance and traffic control techniques where endpoints typically slow down or sometimes even stop transmission entirely when the network is congested to try to avoid congestive collapse. Specific techniques include: exponential backoff in protocols such as 802.11's CSMA/CA and the original Ethernet, window reduction in TCP, and fair queueing in devices such as routers.

Another method to avoid the negative effects of network congestion is implementing quality of service priority schemes allowing selected traffic to bypass congestion. Priority schemes do not solve network congestion by themselves, but they help to alleviate the effects of congestion for critical services. A third method to avoid network congestion is the explicit allocation of network resources to specific flows. One example of this is the use of Contention-Free Transmission Opportunities (CFTXOPs) in the ITU-T G.hn home networking standard.

For the Internet, RFC 2914 addresses the subject of congestion control in detail.

Network resilience

[edit]Network resilience is "the ability to provide and maintain an acceptable level of service in the face of faults and challenges to normal operation."[91]

Security

[edit]Computer networks are also used by security hackers to deploy computer viruses or computer worms on devices connected to the network, or to prevent these devices from accessing the network via a denial-of-service attack.

Network security

[edit]Network Security consists of provisions and policies adopted by the network administrator to prevent and monitor unauthorized access, misuse, modification, or denial of the computer network and its network-accessible resources.[92] Network security is used on a variety of computer networks, both public and private, to secure daily transactions and communications among businesses, government agencies, and individuals.

Network surveillance

[edit]Network surveillance is the monitoring of data being transferred over computer networks such as the Internet. The monitoring is often done surreptitiously and may be done by or at the behest of governments, by corporations, criminal organizations, or individuals. It may or may not be legal and may or may not require authorization from a court or other independent agency.

Computer and network surveillance programs are widespread today, and almost all Internet traffic is or could potentially be monitored for clues to illegal activity.

Surveillance is very useful to governments and law enforcement to maintain social control, recognize and monitor threats, and prevent or investigate criminal activity. With the advent of programs such as the Total Information Awareness program, technologies such as high-speed surveillance computers and biometrics software, and laws such as the Communications Assistance For Law Enforcement Act, governments now possess an unprecedented ability to monitor the activities of citizens.[93]

However, many civil rights and privacy groups—such as Reporters Without Borders, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the American Civil Liberties Union—have expressed concern that increasing surveillance of citizens may lead to a mass surveillance society, with limited political and personal freedoms. Fears such as this have led to lawsuits such as Hepting v. AT&T.[93][94] The hacktivist group Anonymous has hacked into government websites in protest of what it considers "draconian surveillance".[95][96]

End to end encryption

[edit]End-to-end encryption (E2EE) is a digital communications paradigm of uninterrupted protection of data traveling between two communicating parties. It involves the originating party encrypting data so only the intended recipient can decrypt it, with no dependency on third parties. End-to-end encryption prevents intermediaries, such as Internet service providers or application service providers, from reading or tampering with communications. End-to-end encryption generally protects both confidentiality and integrity.

Examples of end-to-end encryption include HTTPS for web traffic, PGP for email, OTR for instant messaging, ZRTP for telephony, and TETRA for radio.

Typical server-based communications systems do not include end-to-end encryption. These systems can only guarantee the protection of communications between clients and servers, not between the communicating parties themselves. Examples of non-E2EE systems are Google Talk, Yahoo Messenger, Facebook, and Dropbox.

The end-to-end encryption paradigm does not directly address risks at the endpoints of the communication themselves, such as the technical exploitation of clients, poor quality random number generators, or key escrow. E2EE also does not address traffic analysis, which relates to things such as the identities of the endpoints and the times and quantities of messages that are sent.

SSL/TLS

[edit]The introduction and rapid growth of e-commerce on the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s made it obvious that some form of authentication and encryption was needed. Netscape took the first shot at a new standard. At the time, the dominant web browser was Netscape Navigator. Netscape created a standard called secure socket layer (SSL). SSL requires a server with a certificate. When a client requests access to an SSL-secured server, the server sends a copy of the certificate to the client. The SSL client checks this certificate (all web browsers come with an exhaustive list of root certificates preloaded), and if the certificate checks out, the server is authenticated and the client negotiates a symmetric-key cipher for use in the session. The session is now in a very secure encrypted tunnel between the SSL server and the SSL client.[65]

See also

[edit]- Cloud computing

- Cyberspace

- Distributed computing

- History of the Internet

- Information Age

- ISO/IEC 11801 – International standard for electrical and optical cables

- Network diagram software

- Network mapping

- Network on a chip

- Network planning and design

- Network simulation

References

[edit]- ^ Peterson, Larry; Davie, Bruce (2000). Computer Networks: A Systems Approach. Singapore: Harcourt Asia. ISBN 9789814066433. Retrieved May 24, 2025.

- ^ Anniss, Matthew (2015). Understanding Computer Networks. United States: Capstone. ISBN 9781484609071.

- ^ a b Ritchie, David (1986). "George Stibitz and the Bell Computers". The Computer Pioneers. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 35. ISBN 067152397X.

- ^ Metropolis, Nicholas (2014). History of Computing in the Twentieth Century. Elsevier. p. 481. ISBN 9781483296685.

- ^ Sterling, Christopher H., ed. (2008). Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. ABC-Clio. p. 399. ISBN 978-1-85109-737-1.

- ^ Haigh, Thomas; Ceruzzi, Paul E. (14 September 2021). A New History of Modern Computing. MIT Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0262542906.

- ^ Ulmann, Bernd (August 19, 2014). AN/FSQ-7: the computer that shaped the Cold War. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-486-85670-5.

- ^ Corbató, F. J.; et al. (1963). The Compatible Time-Sharing System A Programmer's Guide] (PDF). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03008-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

Shortly after the first paper on time-shared computers by C. Strachey at the June 1959 UNESCO Information Processing conference, H. M. Teager and J. McCarthy at MIT delivered an unpublished paper "Time-shared Program Testing" at the August 1959 ACM Meeting.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Computer Pioneers - Christopher Strachey". history.computer.org. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ "Reminiscences on the Theory of Time-Sharing". jmc.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ "Computer - Time-sharing and minicomputers". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ Gillies, James M.; Gillies, James; Gillies, James and Cailliau Robert; Cailliau, R. (2000). How the Web was Born: The Story of the World Wide Web. Oxford University Press. pp. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-286207-5.

- ^ Kitova, O. "Kitov Anatoliy Ivanovich. Russian Virtual Computer Museum". computer-museum.ru. Translated by Alexander Nitusov. Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2021-10-11.

- ^ Peters, Benjamin (25 March 2016). How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262034180.

- ^ Baran, Paul (2002). "The beginnings of packet switching: some underlying concepts" (PDF). IEEE Communications Magazine. 40 (7): 42–48. Bibcode:2002IComM..40g..42B. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2002.1018006. ISSN 0163-6804. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

Essentially all the work was defined by 1961, and fleshed out and put into formal written form in 1962. The idea of hot potato routing dates from late 1960.

- ^ Roberts, Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The evolution of packet switching" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1307–13. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11141. ISSN 0018-9219. S2CID 26876676.

Almost immediately after the 1965 meeting, Davies conceived of the details of a store-and-forward packet switching system.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon and Schuster. pp. 237–246. ISBN 9781476708690. Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ a b Roberts, Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The evolution of packet switching" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1307–13. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11141. S2CID 26876676. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

Both Paul Baran and Donald Davies in their original papers anticipated the use of T1 trunks

- ^ "NIHF Inductee Paul Baran, Who Invented Packet Switching". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ "NIHF Inductee Donald Davies, Who Invented Packet Switching". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2022-02-12. Retrieved 2022-02-12.

- ^ Baran, P. (1964). "On Distributed Communications Networks". IEEE Transactions on Communications. 12 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1964.1088883. ISSN 0096-2244.

- ^ Kleinrock, L. (1978). "Principles and lessons in packet communications". Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1320–1329. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11143. ISSN 0018-9219.

Paul Baran ... focused on the routing procedures and on the survivability of distributed communication systems in a hostile environment, but did not concentrate on the need for resource sharing in its form as we now understand it; indeed, the concept of a software switch was not present in his work.

- ^ Pelkey, James L. "6.1 The Communications Subnet: BBN 1969". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications 1968–1988.

As Kahn recalls: ... Paul Baran's contributions ... I also think Paul was motivated almost entirely by voice considerations. If you look at what he wrote, he was talking about switches that were low-cost electronics. The idea of putting powerful computers in these locations hadn't quite occurred to him as being cost effective. So the idea of computer switches was missing. The whole notion of protocols didn't exist at that time. And the idea of computer-to-computer communications was really a secondary concern.

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2018). The Dream Machine. Stripe Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-953953-36-0.

Baran had put more emphasis on digital voice communications than on computer communications.

- ^ Yates, David M. (1997). Turing's Legacy: A History of Computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945-1995. National Museum of Science and Industry. pp. 132–4. ISBN 978-0-901805-94-2.

Davies's invention of packet switching and design of computer communication networks ... were a cornerstone of the development which led to the Internet

- ^ Naughton, John (2000) [1999]. A Brief History of the Future. Phoenix. p. 292. ISBN 9780753810934.

- ^ a b Campbell-Kelly, Martin (1987). "Data Communications at the National Physical Laboratory (1965-1975)". Annals of the History of Computing. 9 (3/4): 221–247. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1987.10023. S2CID 8172150.

the first occurrence in print of the term protocol in a data communications context ... the next hardware tasks were the detailed design of the interface between the terminal devices and the switching computer, and the arrangements to secure reliable transmission of packets of data over the high-speed lines

- ^ Davies, Donald; Bartlett, Keith; Scantlebury, Roger; Wilkinson, Peter (October 1967). A Digital Communication Network for Computers Giving Rapid Response at remote Terminals (PDF). ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 2020-09-15. "all users of the network will provide themselves with some kind of error control"

- ^ Scantlebury, R. A.; Wilkinson, P.T. (1974). "The National Physical Laboratory Data Communications Network". Proceedings of the 2nd ICCC 74. pp. 223–228.

- ^ Guardian Staff (2013-06-25). "Internet pioneers airbrushed from history". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-01-01. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

This was the first digital local network in the world to use packet switching and high-speed links.

- ^ "The real story of how the Internet became so vulnerable". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-05-30. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

Historians credit seminal insights to Welsh scientist Donald W. Davies and American engineer Paul Baran

- ^ Roberts, Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching" (PDF). IEEE Invited Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

In nearly all respects, Davies' original proposal, developed in late 1965, was similar to the actual networks being built today.

- ^ Norberg, Arthur L.; O'Neill, Judy E. (1996). Transforming computer technology: information processing for the Pentagon, 1962-1986. Johns Hopkins studies in the history of technology New series. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. pp. 153–196. ISBN 978-0-8018-5152-0. Prominently cites Baran and Davies as sources of inspiration.

- ^ A History of the ARPANET: The First Decade (PDF) (Report). Bolt, Beranek & Newman Inc. 1 April 1981. pp. 13, 53 of 183 (III-11 on the printed copy). Archived from the original on 1 December 2012.

Aside from the technical problems of interconnecting computers with communications circuits, the notion of computer networks had been considered in a number of places from a theoretical point of view. Of particular note was work done by Paul Baran and others at the Rand Corporation in a study "On Distributed Communications" in the early 1960's. Also of note was work done by Donald Davies and others at the National Physical Laboratory in England in the mid-1960's. ... Another early major network development which affected development of the ARPANET was undertaken at the National Physical Laboratory in Middlesex, England, under the leadership of D. W. Davies.

- ^ a b c "Birth of the Commercial Internet". National Science Foundation. United States: US Government. Archived from the original on July 1, 2025. Retrieved July 5, 2025.

- ^ Chris Sutton. "Internet Began 35 Years Ago at UCLA with First Message Ever Sent Between Two Computers". UCLA. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08.

- ^ Roberts, Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The evolution of packet switching" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1307–13. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11141. S2CID 26876676.

Significant aspects of the network's internal operation, such as routing, flow control, software design, and network control were developed by a BBN team consisting of Frank Heart, Robert Kahn, Severo Omstein, William Crowther, and David Walden

- ^ F.E. Froehlich, A. Kent (1990). The Froehlich/Kent Encyclopedia of Telecommunications: Volume 1 - Access Charges in the U.S.A. to Basics of Digital Communications. CRC Press. p. 344. ISBN 0824729005.

Although there was considerable technical interchange between the NPL group and those who designed and implemented the ARPANET, the NPL Data Network effort appears to have had little fundamental impact on the design of ARPANET. Such major aspects of the NPL Data Network design as the standard network interface, the routing algorithm, and the software structure of the switching node were largely ignored by the ARPANET designers. There is no doubt, however, that in many less fundamental ways the NPL Data Network had and effect on the design and evolution of the ARPANET.

- ^ Heart, F.; McKenzie, A.; McQuillian, J.; Walden, D. (January 4, 1978). Arpanet Completion Report (PDF) (Technical report). Burlington, MA: Bolt, Beranek and Newman. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-05-27.

- ^ Clarke, Peter (1982). Packet and circuit-switched data networks (PDF) (PhD thesis). Department of Electrical Engineering, Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London. "Many of the theoretical studies of the performance and design of the ARPA Network were developments of earlier work by Kleinrock ... Although these works concerned message switching networks, they were the basis for a lot of the ARPA network investigations ... The intention of the work of Kleinrock [in 1961] was to analyse the performance of store and forward networks, using as the primary performance measure the average message delay. ... Kleinrock [in 1970] extended the theoretical approaches of [his 1961 work] to the early ARPA network."

- ^ Davies, Donald Watts (1979). Computer networks and their protocols. Internet Archive. Wiley. pp. See page refs highlighted at url. ISBN 978-0-471-99750-4.

In mathematical modelling use is made of the theories of queueing processes and of flows in networks, describing the performance of the network in a set of equations. ... The analytic method has been used with success by Kleinrock and others, but only if important simplifying assumptions are made. ... It is heartening in Kleinrock's work to see the good correspondence achieved between the results of analytic methods and those of simulation.

- ^ Davies, Donald Watts (1979). Computer networks and their protocols. Internet Archive. Wiley. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-471-99750-4.

Hierarchical addressing systems for network routing have been proposed by Fultz and, in greater detail, by McQuillan. A recent very full analysis may be found in Kleinrock and Kamoun.

- ^ Feldmann, Anja; Cittadini, Luca; Mühlbauer, Wolfgang; Bush, Randy; Maennel, Olaf (2009). "HAIR: Hierarchical architecture for internet routing" (PDF). Proceedings of the 2009 workshop on Re-architecting the internet. ReArch '09. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 43–48. doi:10.1145/1658978.1658990. ISBN 978-1-60558-749-3. S2CID 2930578.

The hierarchical approach is further motivated by theoretical results (e.g., [16]) which show that, by optimally placing separators, i.e., elements that connect levels in the hierarchy, tremendous gain can be achieved in terms of both routing table size and update message churn. ... [16] KLEINROCK, L., AND KAMOUN, F. Hierarchical routing for large networks: Performance evaluation and optimization. Computer Networks (1977).

- ^ Kirstein, P.T. (1999). "Early experiences with the Arpanet and Internet in the United Kingdom". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 21 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1109/85.759368. S2CID 1558618.

- ^ Kirstein, Peter T. (2009). "The early history of packet switching in the UK". IEEE Communications Magazine. 47 (2): 18–26. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2009.4785372. S2CID 34735326.

- ^ "Xerox Researcher Proposes 'Ethernet'". computerhistory.org. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

Robert Metcalfe, a researcher at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in California, writes his original memo proposing an 'Ethernet', a means of connecting computers together.

- ^ "Ethernet is Still Going Strong After 50 Years - IEEE Spectrum". spectrum.ieee.org. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ^ "ALOHAnet – University of Hawai'i College of Engineering". eng.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ^ "Celebrating 50 Years of the ALOHA System and the Future of Networking". computerhistory.org. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ^ Hsu, Hansen; McJones, Paul. "Xerox PARC file system archive". xeroxparcarchive.computerhistory.org.

Pup (PARC Universal Packet) was a set of internetworking protocols and packet format designed and first implemented (in BCPL) by David R. Boggs, John F. Shoch, Edward A. Taft, and Robert M. Metcalfe. It became a key influence on the later design of TCP/IP.

- ^ Bennett, Richard (September 2009). "Designed for Change: End-to-End Arguments, Internet Innovation, and the Net Neutrality Debate" (PDF). Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-29. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ Cerf, V.; Kahn, R. (1974). "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Communications. 22 (5): 637–648. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1974.1092259. ISSN 1558-0857.

The authors wish to thank a number of colleagues for helpful comments during early discussions of international network protocols, especially R. Metcalfe, R. Scantlebury, D. Walden, and H. Zimmerman; D. Davies and L. Pouzin who constructively commented on the fragmentation and accounting issues; and S. Crocker who commented on the creation and destruction of associations.

- ^ Cerf, Vinton; dalal, Yogen; Sunshine, Carl (December 1974). Specification of Internet Transmission Control Protocol. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0675. RFC 675.

- ^ Robert M. Metcalfe; David R. Boggs (July 1976). "Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks". Communications of the ACM. 19 (5): 395–404. doi:10.1145/360248.360253. S2CID 429216.

- ^ Press, Gil. "The Ethernet And The Telegraph Or What Metcalfe And Morse Have Wrought". Forbes. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

- ^ "Ethernet and Robert Metcalfe and Xerox PARC 1971-1975 | History of Computer Communications". historyofcomputercommunications.info. Retrieved 2025-03-08.

Once successful, Xerox filed for patents covering the Ethernet technology under the names of Metcalfe, Boggs, Butler Lampson and Chuck Thacker. (Metcalfe insisted Lampson, the 'intellectual guru under whom we all had the privilege to work' and Thacker 'the guy who designed the Altos' names were on the patent.)

- ^ a b Spurgeon, Charles E. (2000). Ethernet The Definitive Guide. O'Reilly & Associates. ISBN 1-56592-660-9.

- ^ "Introduction to Ethernet Technologies". www.wband.com. WideBand Products. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- ^ Pelkey, James L. (2007). "Yogen Dalal". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications, 1968-1988. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ^ "What is the Importance of Embedded Networking?". Total Phase. United States: Total Phase, Inc. November 26, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2025.

- ^ Gershenfeld, Neil; Krikorian, Raffi; Cohen, Danny (October 2004). "The internet of things". Scientific American. 291 (4). Springer Nature: 76–81. Bibcode:2004SciAm.291d..76G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1004-76. JSTOR 26060727. PMID 15487673. Retrieved June 23, 2025.

- ^ Derek Barber. "The Origins of Packet Switching". Computer Resurrection Issue 5. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

The Spanish, dark horses, were the first people to have a public network. They'd got a bank network which they craftily turned into a public network overnight, and beat everybody to the post.

- ^ Després, R. (1974). "RCP, the Experimental Packet-Switched Data Transmission Service of the French PTT". Proceedings of ICCC 74. pp. 171–185. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ National Research Council; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Computer Science and Telecommunications Board; Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Applications; NII 2000 Steering Committee (1998-02-05). The Unpredictable Certainty: White Papers. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-17414-5. Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ a b Meyers, Mike (2012). CompTIA Network+ exam guide : (Exam N10-005) (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071789226. OCLC 748332969.

- ^ A. Hooke (September 2000), Interplanetary Internet (PDF), Third Annual International Symposium on Advanced Radio Technologies, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-13, retrieved 2011-11-12

- ^ "Bergen Linux User Group's CPIP Implementation". Blug.linux.no. Archived from the original on 2014-02-15. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ^ "Define switch". webopedia. September 1996. Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (2003). Computer Networks (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- ^ "IEEE Standard for Local and Metropolitan Area Networks--Port-Based Network Access Control". IEEE STD 802.1X-2020 (Revision of IEEE STD 802.1X-2010 Incorporating IEEE STD 802.1Xbx-2014 and IEEE STD 802.1Xck-2018). 7.1.3 Connectivity to unauthenticated systems. February 2020. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2020.9018454. ISBN 978-1-5044-6440-6.

- ^ "IEEE Standard for Information Technology--Telecommunications and Information Exchange between Systems - Local and Metropolitan Area Networks--Specific Requirements - Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications". IEEE STD 802.11-2020 (Revision of IEEE STD 802.11-2016). 4.2.5 Interaction with other IEEE 802 layers. February 2021. doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2021.9363693. ISBN 978-1-5044-7283-8.

- ^ Martin, Thomas. "Design Principles for DSL-Based Access Solutions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- ^ Paetsch, Michael (1993). The evolution of mobile communications in the US and Europe: Regulation, technology, and markets. Boston, London: Artech House. ISBN 978-0-8900-6688-1.

- ^ a b D. Andersen; H. Balakrishnan; M. Kaashoek; R. Morris (October 2001), Resilient Overlay Networks, Association for Computing Machinery, archived from the original on 2011-11-24, retrieved 2011-11-12

- ^ "End System Multicast". project web site. Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on 2005-02-21. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

- ^ Bush, S. F. (2010). Nanoscale Communication Networks. Artech House. ISBN 978-1-60807-003-9.

- ^ Margaret Rouse. "personal area network (PAN)". TechTarget. Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- ^ "New global standard for fully networked home". ITU-T Newslog. ITU. 2008-12-12. Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ "IEEE P802.3ba 40Gb/s and 100Gb/s Ethernet Task Force". IEEE 802.3 ETHERNET WORKING GROUP. Archived from the original on 2011-11-20. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ "IEEE 802.20 Mission and Project Scope". IEEE 802.20 — Mobile Broadband Wireless Access (MBWA). Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ a b Rosen, E.; Rekhter, Y. (March 1999). BGP/MPLS VPNs. doi:10.17487/RFC2547. RFC 2547.

- ^ "Maps". The Opto Project. Archived from the original on 2005-01-15.

- ^ Mansfield-Devine, Steve (December 2009). "Darknets". Computer Fraud & Security. 2009 (12): 4–6. doi:10.1016/S1361-3723(09)70150-2.

- ^ Wood, Jessica (2010). "The Darknet: A Digital Copyright Revolution" (PDF). Richmond Journal of Law and Technology. 16 (4). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Klensin, J. (October 2008). Simple Mail Transfer Protocol. doi:10.17487/RFC5321. RFC 5321.

- ^ Mockapetris, P. (November 1987). Domain names – Implementation and Specification. doi:10.17487/RFC1035. RFC 1035.

- ^ Peterson, L.L.; Davie, B.S. (2011). Computer Networks: A Systems Approach (5th ed.). Elsevier. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-1238-5060-7.

- ^ ITU-D Study Group 2 (June 2006). Teletraffic Engineering Handbook (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-11.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Telecommunications Magazine Online". January 2003. Archived from the original on 2011-02-08.

- ^ "State Transition Diagrams". Archived from the original on 2003-10-15. Retrieved 2003-07-13.

- ^ "Definitions: Resilience". ResiliNets Research Initiative. Archived from the original on 2020-11-06. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Simmonds, A; Sandilands, P; van Ekert, L (2004). "An Ontology for Network Security Attacks". Applied Computing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3285. pp. 317–323. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-30176-9_41. ISBN 978-3-540-23659-7. S2CID 2204780.

- ^ a b "Is the U.S. Turning Into a Surveillance Society?". American Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on 2017-03-14. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Jay Stanley; Barry Steinhardt (January 2003). "Bigger Monster, Weaker Chains: The Growth of an American Surveillance Society" (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Emil Protalinski (2012-04-07). "Anonymous hacks UK government sites over 'draconian surveillance'". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ James Ball (2012-04-20). "Hacktivists in the frontline battle for the internet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2018-03-14. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

Further reading

[edit]History

[edit]- Pelkey, James (1994). "History of Computer Communications". The History of Computer Communications. United States: Computer History Museum. Retrieved August 7, 2025.

- Gillies, James M.; Cailliau, Robert (2000). How the Web was Born: The Story of the World Wide Web. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-286207-5.

Textbooks

[edit]- Peterson, Larry; Davie, Bruce (2000). Computer Networks: A Systems Approach. Singapore: Harcourt Asia. ISBN 9789814066433. Retrieved May 24, 2025.

- Kurose, James F; Ross, Keith W. (2005). Computer Networking: A Top-Down Approach Featuring the Internet. Pearson Education.

- Stallings, William (2004). Computer Networking with Internet Protocols and Technology. Pearson Education.

- Bertsekas, Dimitri; Gallager, Robert (1992). Data Networks. Prentice Hall.

Computer network

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Core Principles