Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polyethylene

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Polyethene or poly(methylene)[1]

| |

| Other names

Polyethylene

Polythene | |

| Identifiers | |

| Abbreviations | PE |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.121.698 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Polyethylene |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| (C2H4)n | |

| Density | 0.88–0.96 g/cm3[2] |

| Melting point | 115–135 °C (239–275 °F; 388–408 K)[2] |

| Not soluble | |

| log P | 1.02620[3] |

| −9.67×10−6 (HDPE, SI, 22 °C)[4] | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−28 to −29 kJ/mol[5] |

| 650–651 kJ/mol, 46 MJ/kg[5] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Fiber |

|---|

|

| Natural fibers |

| Human-made fibers |

Polyethylene or polythene (abbreviated PE; IUPAC name polyethene or poly(methylene)) is the most commonly produced plastic.[7] It is a polymer, primarily used for packaging (plastic bags, plastic films, geomembranes and containers including bottles, cups, jars, etc.). As of 2017[update], over 100 million tonnes of polyethylene resins are being produced annually, accounting for 34% of the total plastics market.[8][9]

Many kinds of polyethylene are known, with most having the chemical formula (C2H4)n. PE is usually a mixture of similar polymers of ethylene, with various values of n. It can be low-density or high-density and many variations thereof. Its properties can be modified further by crosslinking or copolymerization. All forms are nontoxic as well as chemically resilient, contributing to polyethylene's popularity as a multi-use plastic. However, polyethylene's chemical resilience also makes it a long-lived and decomposition-resistant pollutant when disposed of improperly.[10] Being a hydrocarbon, polyethylene is colorless to opaque (without impurities or colorants) and combustible.[11]

History

[edit]Polyethylene was first synthesized by the German chemist Hans von Pechmann, who prepared it by accident in 1898 while investigating diazomethane.[12][a][13][b] When his colleagues Eugen Bamberger and Friedrich Tschirner characterized the white, waxy substance that he had created, they recognized that it contained long −CH2− chains and termed it polymethylene.[14]

The first industrially practical polyethylene synthesis (diazomethane is a notoriously unstable substance that is generally avoided in industrial syntheses) was again accidentally discovered in 1933 by Eric Fawcett and Reginald Gibson at the Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) works in Northwich, England.[15] Upon applying extremely high pressure (several hundred atmospheres) to a mixture of ethylene and benzaldehyde they again produced a white, waxy material. Because the reaction had been initiated by trace oxygen contamination in their apparatus, the experiment was difficult to reproduce at first. It was not until 1935 that another ICI chemist, Michael Perrin, developed this accident into a reproducible high-pressure synthesis for polyethylene that became the basis for industrial low-density polyethylene (LDPE) production beginning in 1939. Because polyethylene was found to have very low-loss properties at very high frequency radio waves, commercial distribution in Britain was suspended on the outbreak of World War II, secrecy imposed, and the new process was used to produce insulation for UHF and SHF coaxial cables of radar sets. During World War II, further research was done on the ICI process and in 1944, DuPont at Sabine River, Texas, and Union Carbide Corporation at South Charleston, West Virginia, began large-scale commercial production under license from ICI.[16][17]

The landmark breakthrough in the commercial production of polyethylene began with the development of catalysts that promoted the polymerization at mild temperatures and pressures. The first of these was a catalyst based on chromium trioxide discovered in 1951 by Robert Banks and J. Paul Hogan at Phillips Petroleum.[18] In 1953 the German chemist Karl Ziegler developed a catalytic system based on titanium halides and organoaluminium compounds that worked at even milder conditions than the Phillips catalyst. The Phillips catalyst is less expensive and easier to work with, however, and both methods are heavily used industrially. By the end of the 1950s both the Phillips- and Ziegler-type catalysts were being used for high-density polyethylene (HDPE) production. In the 1970s, the Ziegler system was improved by the incorporation of magnesium chloride. Catalytic systems based on soluble catalysts, the metallocenes, were reported in 1976 by Walter Kaminsky and Hansjörg Sinn. The Ziegler- and metallocene-based catalysts families have proven to be very flexible at copolymerizing ethylene with other olefins and have become the basis for the wide range of polyethylene resins available today, including very-low-density polyethylene and linear low-density polyethylene. Such resins, in the form of UHMWPE fibers, have (as of 2005) begun to replace aramids in many high-strength applications.

Properties

[edit]The properties of polyethylene depend strongly on type. The molecular weight, crosslinking, and presence of comonomers all strongly affect its properties. It is for this structure-property relation that intense effort has been invested into diverse kinds of PE.[7][19] LDPE is softer and more transparent than HDPE. For medium- and high-density polyethylene the melting point is typically in the range 120 to 130 °C (248 to 266 °F). The melting point for average commercial low-density polyethylene is typically 105 to 115 °C (221 to 239 °F). These temperatures vary strongly with the type of polyethylene, but the theoretical upper limit of melting of polyethylene is reported to be 144 to 146 °C (291 to 295 °F). Combustion typically occurs above 349 °C (660 °F).

Most LDPE, MDPE, and HDPE grades have excellent chemical resistance, meaning that they are not attacked by strong acids or strong bases and are resistant to gentle oxidants and reducing agents. Crystalline samples do not dissolve at room temperature. Polyethylene (other than cross-linked polyethylene) usually can be dissolved at elevated temperatures in aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene or xylene, or in chlorinated solvents such as trichloroethane or trichlorobenzene.[7]

Polyethylene absorbs almost no water. The permeability for water vapor and polar gases of is lower than for most plastics. On the other hand, non-polar gases such as Oxygen, carbon dioxide, and flavorings can pass it easily.

Polyethylene burns slowly with a blue flame having a yellow tip and gives off an odour of paraffin (similar to candle flame). The material continues burning on removal of the flame source and produces a drip.[20]

Polyethylene cannot be imprinted or bonded with adhesives without pretreatment. High-strength joints are readily achieved with plastic welding.

Electrical

[edit]Polyethylene is a good electrical insulator. It offers good electrical treeing resistance; however, it becomes easily electrostatically charged (which can be reduced by additions of graphite, carbon black or antistatic agents). When pure, the dielectric constant is in the range 2.2 to 2.4 depending on the density[21] and the loss tangent is very low, making it a good dielectric for building capacitors. For the same reason it is commonly used as the insulation material for high-frequency coaxial and twisted pair cables.

Optical

[edit]Depending on thermal history and film thickness, PE can vary between almost clear (transparent), milky-opaque (translucent) and opaque. LDPE has the greatest, LLDPE slightly less, and HDPE the least transparency. Transparency is reduced by crystallites if they are larger than the wavelength of visible light.[22]

Manufacturing process

[edit]Monomer

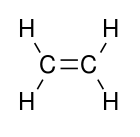

[edit]The ingredient or monomer is ethylene (IUPAC name ethene), a gaseous hydrocarbon with the formula C2H4, which can be viewed as a pair of methylene groups (−CH

2−) connected to each other. Typical specifications for PE purity are <5 ppm for water, oxygen, and other alkenes contents. Acceptable contaminants include N2, ethane (common precursor to ethylene), and methane. Ethylene is usually produced from petrochemical sources, but is also generated by dehydration of ethanol.[7]

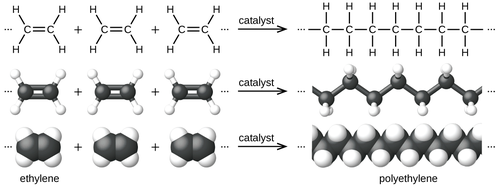

Polymerization

[edit]

Polymerization of ethylene to polyethylene is described by the following chemical equation:

Ethylene is a stable molecule that polymerizes only upon contact with catalysts. The conversion is highly exothermic. Coordination polymerization is the most pervasive technology, which means that metal chlorides or metal oxides are used. The most common catalysts consist of titanium(III) chloride, the so-called Ziegler–Natta catalysts. Another common catalyst is the Phillips catalyst, prepared by depositing chromium(VI) oxide on silica.[7] Polyethylene can be produced through radical polymerization, but this route has only limited utility and typically requires high-pressure apparatus.

Joining

[edit]Commonly used methods for joining polyethylene parts together include:[24]

- Welding

- Fastening

- Adhesives[24]

- Pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSAs)

- Dispersion of solvent-type PSAs

- Polyurethane contact adhesives

- Two-part polyurethane

- Epoxy adhesives

- Hot-melt adhesives

- Solvent bonding – Adhesives and solvents are rarely used as solvent bonding because polyethylene is nonpolar and has a high resistance to solvents.

- Pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSAs)

Pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSA) are feasible if the surface chemistry or charge is modified with plasma activation, flame treatment, or corona treatment.

Classification

[edit]Polyethylene is classified by its density and branching. Its mechanical properties depend significantly on variables such as the extent and type of branching, the crystal structure, and the molecular weight. There are several types of polyethylene:

- Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE)

- Ultra-low-molecular-weight polyethylene (ULMWPE or PE-WAX)

- High-molecular-weight polyethylene (HMWPE)

- High-density polyethylene (HDPE)

- High-density cross-linked polyethylene (HDXLPE)

- Cross-linked polyethylene (PEX or XLPE)

- Medium-density polyethylene (MDPE)

- Linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE)

- Low-density polyethylene (LDPE)

- Very-low-density polyethylene (VLDPE)

- Chlorinated polyethylene (CPE)

With regard to sold volumes, the most important polyethylene grades are HDPE, LLDPE, and LDPE.

Ultra-high-molecular-weight (UHMWPE)

[edit]

UHMWPE is polyethylene with a molecular weight numbering in the millions, usually between 3.5 and 7.5 million amu.[25] The high molecular weight makes it a very tough material, but results in less efficient packing of the chains into the crystal structure as evidenced by densities of less than high-density polyethylene (for example, 0.930–0.935 g/cm3). UHMWPE can be made through any catalyst technology, although Ziegler catalysts are most common. Because of its outstanding toughness and its cut, wear, and excellent chemical resistance, UHMWPE is used in a diverse range of applications. These include can- and bottle-handling machine parts, moving parts on weaving machines, bearings, gears, artificial joints, edge protection on ice rinks, steel cable replacements on ships, and butchers' chopping boards. It is commonly used for the construction of articular portions of implants used for hip and knee replacements. As fiber, it competes with aramid in bulletproof vests.

High-density (HDPE)

[edit]

HDPE is defined by a density of greater or equal to 0.941 g/cm3. HDPE has a low degree of branching. The mostly linear molecules pack together well, so intermolecular forces are stronger than in highly branched polymers. HDPE can be produced by chromium/silica catalysts, Ziegler–Natta catalysts or metallocene catalysts; by choosing catalysts and reaction conditions, the small amount of branching that does occur can be controlled. These catalysts prefer the formation of free radicals at the ends of the growing polyethylene molecules. They cause new ethylene monomers to add to the ends of the molecules, rather than along the middle, causing the growth of a linear chain.

HDPE has high tensile strength. It is used in products and packaging such as milk jugs, detergent bottles, butter tubs, garbage containers, and water pipes.

Cross-linked (PEX or XLPE)

[edit]PEX is a medium- to high-density polyethylene containing cross-link bonds introduced into the polymer structure, changing the thermoplastic into a thermoset. The high-temperature properties of the polymer are improved, its flow is reduced, and its chemical resistance is enhanced. PEX is used in some potable-water plumbing systems because tubes made of the material can be expanded to fit over a metal nipple and it will slowly return to its original shape, forming a permanent, water-tight connection.

Medium-density (MDPE)

[edit]MDPE is defined by a density range of 0.926–0.940 g/cm3. MDPE can be produced by chromium/silica catalysts, Ziegler–Natta catalysts, or metallocene catalysts. MDPE has good shock and drop resistance properties. It also is less notch-sensitive than HDPE; stress-cracking resistance is better than HDPE. MDPE is typically used in gas pipes and fittings, sacks, shrink film, packaging film, carrier bags, and screw closures.

Linear low-density (LLDPE)

[edit]LLDPE is defined by a density range of 0.915–0.925 g/cm3. LLDPE is a substantially linear polymer with significant numbers of short branches, commonly made by copolymerization of ethylene with short-chain alpha-olefins (for example, 1-butene, 1-hexene, and 1-octene). LLDPE has higher tensile strength than LDPE, and it exhibits higher impact and puncture resistance than LDPE. Lower-thickness (gauge) films can be blown, compared with LDPE, with better environmental stress cracking resistance, but they are not as easy to process. LLDPE is used in packaging, particularly film for bags and sheets. Lower thickness may be used compared to LDPE. It is used for cable coverings, toys, lids, buckets, containers, and pipe. While other applications are available, LLDPE is used predominantly in film applications due to its toughness, flexibility, and relative transparency. Product examples range from agricultural films, Saran wrap, and bubble wrap to multilayer and composite films.

Low-density (LDPE)

[edit]LDPE is defined by a density range of 0.910–0.940 g/cm3. LDPE has a high degree of short- and long-chain branching, which means that the chains do not pack into the crystal structure as well. It has, therefore, less strong intermolecular forces as the instantaneous-dipole induced-dipole attraction is less. This results in a lower tensile strength and increased ductility. LDPE is created by free-radical polymerization. The high degree of branching with long chains gives molten LDPE unique and desirable flow properties. LDPE is used for both rigid containers and plastic film applications such as plastic bags and film wrap.

The radical polymerization process used to make LDPE does not include a catalyst that "supervises" the radical sites on the growing PE chains. (In HDPE synthesis, the radical sites are at the ends of the PE chains, because the catalyst stabilizes their formation at the ends.) Secondary radicals (in the middle of a chain) are more stable than primary radicals (at the end of the chain), and tertiary radicals (at a branch point) are more stable yet. Each time an ethylene monomer is added, it creates a primary radical, but often these will rearrange to form more stable secondary or tertiary radicals. Addition of ethylene monomers to the secondary or tertiary sites creates branching.

Very-low-density (VLDPE)

[edit]VLDPE is defined by a density range of 0.880–0.915 g/cm3. VLDPE is a substantially linear polymer with high levels of short-chain branches, commonly made by copolymerization of ethylene with short-chain alpha-olefins (for example, 1-butene, 1-hexene and 1-octene). VLDPE is most commonly produced using metallocene catalysts due to the greater co-monomer incorporation exhibited by these catalysts. VLDPEs are used for hose and tubing, ice and frozen food bags, food packaging and stretch wrap as well as impact modifiers when blended with other polymers.

Much research activity has focused on the nature and distribution of long chain branches in polyethylene. In HDPE, a relatively small number of these branches, perhaps one in 100 or 1,000 branches per backbone carbon, can significantly affect the rheological properties of the polymer.

Copolymers

[edit]In addition to copolymerization with alpha-olefins, ethylene can be copolymerized with a wide range of other monomers and ionic composition that creates ionized free radicals. Common examples include vinyl acetate (the resulting product is ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer, or EVA, widely used in athletic-shoe sole foams) and a variety of acrylates. Applications of acrylic copolymer include packaging and sporting goods, and superplasticizer, used in cement production.

Types of polyethylenes

[edit]The particular material properties of "polyethylene" depend on its molecular structure. Molecular weight and crystallinity are the most significant factors; crystallinity in turn depends on molecular weight and degree of branching. The less the polymer chains are branched, and the lower the molecular weight, the higher the crystallinity of polyethylene. Crystallinity ranges from 35% (PE-LD/PE-LLD) to 80% (PE-HD). Polyethylene has a density of 1.0 g/cm3 in crystalline regions and 0.86 g/cm3 in amorphous regions. An almost linear relationship exists between density and crystallinity.[19]

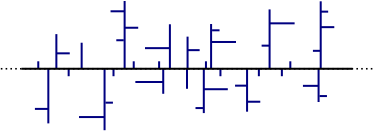

The degree of branching of the different types of polyethylene can be schematically represented as follows:[19]

| PE-HD | |

| PE-LLD | |

| PE-LD |

|

The figure shows polyethylene backbones, short-chain branches and side-chain branches. The polymer chains are represented linearly.

Chain branches

[edit]The properties of polyethylene are highly dependent on type and number of chain branches. The chain branches in turn depend on the process used: either the high-pressure process (only PE-LD) or the low-pressure process (all other PE grades). Low-density polyethylene is produced by the high-pressure process by radical polymerization, thereby numerous short chain branches as well as long chain branches are formed. Short chain branches are formed by intramolecular chain transfer reactions, they are always butyl or ethyl chain branches because the reaction proceeds after the following mechanism:

Environmental issues

[edit]

The widespread usage of polyethylene poses potential difficulties for waste management because it is not readily biodegradable. Since 2008, Japan has increased plastic recycling, but still has a large amount of plastic wrapping which goes to waste. Plastic recycling in Japan is a potential US$90 billion market.[26]

It is possible to rapidly convert polyethylene to hydrogen and graphene by heating. The energy needed is much less than for producing hydrogen by electrolysis.[27][28]

Biodegradability

[edit]Several experiments have been conducted aimed at discovering an enzyme or organisms that will degrade polyethylene. Several plastics - such as polyesters, polycarbonates, and polyamides - degrade either by hydrolysis or air oxidation. In some cases the degradation is increased by bacteria or various enzyme cocktails. The situation is very different with polymers where the backbone consists solely of C-C bonds. These polymers include polyethylene, but also polypropylene, polystyrene and acrylates. At best, these polymers degrade very slowly, but degradation experiments are difficult because yields and rates are very slow.[29] Further confusing the situation, even preliminary successes are greeted with enthusiasm by the popular press.[30][31][32] Some technical challenges in this area include the failure to identify enzymes responsible for the proposed degradation. Another issue is that organisms are incapable of importing hydrocarbons of molecular weight greater than 500.[29]

Bacteria and insect case studies

[edit]The Indian mealmoth larvae are claimed to metabolize polyethylene based on observing that plastic bags at a researcher's home had small holes in them. Deducing that the hungry larvae must have digested the plastic somehow, he and his team analyzed their gut bacteria and found a few that could use plastic as their only carbon source. Not only could the bacteria from the guts of the Plodia interpunctella moth larvae metabolize polyethylene, they degraded it significantly, dropping its tensile strength by 50%, its mass by 10% and the molecular weights of its polymeric chains by 13%.[33][34]

The caterpillar of Galleria mellonella is claimed to consume polyethylene. The caterpillar is able to digest polyethylene due to a combination of its gut microbiota[35] and its saliva containing enzymes that oxidise and depolymerise the plastic.[36]

Climate change

[edit]When exposed to ambient solar radiation the plastic produces trace amounts of two greenhouse gases, methane and ethylene. The plastic type which releases gases at the highest rate is low-density polyethylene (LDPE). Due to its low density it breaks down more easily over time, leading to higher surface areas. When incubated in air, LDPE emits gases at rates ~2 times and ~76 times higher in comparison to incubation in water for methane and ethylene, respectively. However, based on the rates measured in the study methane production by plastics is presently an insignificant component of the global methane budget.[37]

Chemically modified polyethylene

[edit]Polyethylene may either be modified in the polymerization by polar or non-polar comonomers or after polymerization through polymer-analogous reactions. Common polymer-analogous reactions are in case of polyethylene crosslinking, chlorination and sulfochlorination.

Non-polar ethylene copolymers

[edit]α-olefins

[edit]In the low pressure process α-olefins (e.g. 1-butene or 1-hexene) may be added, which are incorporated in the polymer chain during polymerization. These copolymers introduce short side chains, thus crystallinity and density are reduced. As explained above, mechanical and thermal properties are changed thereby. In particular, PE-LLD is produced this way.

Metallocene polyethylene (PE-MC)

[edit]Metallocene polyethylene (PE-M) is prepared by means of metallocene catalysts, usually including copolymers (z. B. ethene / hexene). Metallocene polyethylene has a relatively narrow molecular weight distribution, exceptionally high toughness, excellent optical properties and a uniform comonomer content. Because of the narrow molecular weight distribution it behaves less pseudoplastic (especially under larger shear rates). Metallocene polyethylene has a low proportion of low molecular weight (extractable) components and a low welding and sealing temperature. Thus, it is particularly suitable for the food industry.[19]: 238 [38]: 19

Polyethylene with multimodal molecular weight distribution

[edit]Polyethylene with multimodal molecular weight distribution consists of several polymer fractions, which are homogeneously mixed. Such polyethylene types offer extremely high stiffness, toughness, strength, stress crack resistance and an increased crack propagation resistance. They consist of equal proportions higher and lower molecular polymer fractions. The lower molecular weight units crystallize easier and relax faster. The higher molecular weight fractions form linking molecules between crystallites, thereby increasing toughness and stress crack resistance. Polyethylene with multimodal molecular weight distribution can be prepared either in two-stage reactors, by catalysts with two active centers on a carrier or by blending in extruders.[19]: 238

Cyclic olefin copolymers (COC)

[edit]Cyclic olefin copolymers are prepared by copolymerization of ethene and cycloolefins (usually norbornene) produced by using metallocene catalysts. The resulting polymers are amorphous polymers and particularly transparent and heat resistant.[19]: 239 [38]: 27

Polar ethylene copolymers

[edit]The basic compounds used as polar comonomers are vinyl alcohol (Ethenol, an unsaturated alcohol), acrylic acid (propenoic acid, an unsaturated acid) and esters containing one of the two compounds.

Ethylene copolymers with unsaturated alcohols

[edit]Ethylene/vinyl alcohol copolymer (EVOH) is (formally) a copolymer of PE and vinyl alcohol (ethenol), which is prepared by (partial) hydrolysis of ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (as vinyl alcohol itself is not stable). However, typically EVOH has a higher comonomer content than the VAC commonly used.[39]: 239

EVOH is used in multilayer films for packaging as a barrier layer (barrier plastic). As EVOH is hygroscopic (water-attracting), it absorbs water from the environment, whereby it loses its barrier effect. Therefore, it must be used as a core layer surrounded by other plastics (like LDPE, PP, PA or PET). EVOH is also used as a coating agent against corrosion at street lights, traffic light poles and noise protection walls.[39]: 239

Ethylene/acrylic acid copolymers (EAA)

[edit]Copolymer of ethylene and unsaturated carboxylic acids (such as acrylic acid) are characterized by good adhesion to diverse materials, by resistance to stress cracking and high flexibility.[40] However, they are more sensitive to heat and oxidation than ethylene homopolymers. Ethylene/acrylic acid copolymers are used as adhesion promoters.[19]

If salts of an unsaturated carboxylic acid are present in the polymer, thermo-reversible ion networks are formed, they are called ionomers. Ionomers are highly transparent thermoplastics which are characterized by high adhesion to metals, high abrasion resistance and high water absorption.[19]

Ethylene copolymers with unsaturated esters

[edit]If unsaturated esters are copolymerized with ethylene, either the alcohol moiety may be in the polymer backbone (as it is the case in ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer) or of the acid moiety (e. g. in ethylene-ethyl acrylate copolymer). Ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymers are prepared similarly to LD-PE by high pressure polymerization. The proportion of comonomer has a decisive influence on the behaviour of the polymer.

The density decreases up to a comonomer share of 10% because of the disturbed crystal formation. With higher proportions it approaches to the one of polyvinyl acetate (1.17 g/cm3).[39]: 235 Due to decreasing crystallinity ethylene vinyl acetate copolymers are getting softer with increasing comonomer content. The polar side groups change the chemical properties significantly (compared to polyethylene):[19]: 224 weather resistance, adhesiveness and weldability rise with comonomer content, while the chemical resistance decreases. Also mechanical properties are changed: stress cracking resistance and toughness in the cold rise, whereas yield stress and heat resistance decrease. With a very high proportion of comonomers (about 50%) rubbery thermoplastics are produced (thermoplastic elastomers).[39]: 235

Ethylene-ethyl acrylate copolymers behave similarly to ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymers.[19]: 240

Crosslinking

[edit]A basic distinction is made between peroxide crosslinking (PE-Xa), silane crosslinking (PE-Xb), electron beam crosslinking (PE-Xc) and azo crosslinking (PE-Xd).[41]

Shown are the peroxide, the silane and irradiation crosslinking. In each method, a radical is generated in the polyethylene chain (top center), either by radiation (h·ν) or by peroxides (R-O-O-R). Then, two radical chains can either directly crosslink (bottom left) or indirectly by silane compounds (bottom right).

- Peroxide crosslinking (PE-Xa): The crosslinking of polyethylene using peroxides (e. g. dicumyl or di-tert-butyl peroxide) is still of major importance. In the so-called Engel process, a mixture of HDPE and 2%[42] peroxide is at first mixed at low temperatures in an extruder and then crosslinked at high temperatures (between 200 and 250 °C).[41] The peroxide decomposes to peroxide radicals (RO•), which abstract (remove) hydrogen atoms from the polymer chain, leading to radicals. When these combine, a crosslinked network is formed.[43] The resulting polymer network is uniform, of low tension and high flexibility, whereby it is softer and tougher than (the irradiated) PE-Xc.[41]

- Silane crosslinking (PE-Xb): In the presence of silanes (e.g. trimethoxyvinylsilane) polyethylene can initially be Si-functionalized by irradiation or by a small amount of a peroxide. Later Si-OH groups can be formed in a water bath by hydrolysis, which condense then and crosslink the PE by the formation of Si-O-Si bridges. [16] Catalysts such as dibutyltin dilaurate may accelerate the reaction.[42]

- Irradiation crosslinking (PE-Xc): The crosslinking of polyethylene is also possible by a downstream radiation source (usually an electron accelerator, occasionally an isotopic radiator). PE products are crosslinked below the crystalline melting point by splitting off hydrogen atoms. β-radiation possesses a penetration depth of 10 mm, ɣ-radiation 100 mm. Thereby the interior or specific areas can be excluded from the crosslinking.[41] However, due to high capital and operating costs radiation crosslinking plays only a minor role compared with the peroxide crosslinking.[39] In contrast to peroxide crosslinking, the process is carried out in the solid state. Thereby, the cross-linking takes place primarily in the amorphous regions, while the crystallinity remains largely intact.[42]

- Azo crosslinking (PE-Xd): In the so-called Lubonyl process polyethylene is crosslinked preadded azo compounds after extrusion in a hot salt bath.[39][41]

Chlorination and sulfochlorination

[edit]Chlorinated Polyethylene (PE-C) is an inexpensive material having a chlorine content from 34 to 44%. It is used in blends with PVC because the soft, rubbery chloropolyethylene is embedded in the PVC matrix, thereby increasing the impact resistance. It also increases the weather resistance. Furthermore, it is used for softening PVC foils, without risking the migrate of plasticizers. Chlorinated polyethylene can be crosslinked peroxidically to form an elastomer which is used in cable and rubber industry.[39] When chlorinated polyethylene is added to other polyolefins, it reduces the flammability.[19]: 245

Chlorosulfonated PE (CSM) is used as starting material for ozone-resistant synthetic rubber.[44]

Bio-based polyethylene

[edit]Braskem and Toyota Tsusho Corporation started joint marketing activities to produce polyethylene from sugarcane. Braskem will build a new facility at their existing industrial unit in Triunfo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil with an annual production capacity of 200,000 short tons (180,000,000 kg), and will produce high-density and low-density polyethylene from bioethanol derived from sugarcane.[45]

Nomenclature and general description of the process

[edit]The name polyethylene comes from the ingredient and not the resulting chemical compound, which contains no double bonds. The scientific name polyethene is systematically derived from the scientific name of the monomer.[46][47] The alkene monomer converts to a long, sometimes very long, alkane in the polymerization process.[47] In certain circumstances it is useful to use a structure-based nomenclature; in such cases IUPAC recommends poly(methylene) (poly(methanediyl) is a non-preferred alternative).[46] The difference in names between the two systems is due to the opening up of the monomer's double bond upon polymerization.[48] The name is abbreviated to PE. In a similar manner polypropylene and polystyrene are shortened to PP and PS, respectively. In the United Kingdom and India the polymer is commonly called polythene, from the ICI trade name, although this is not recognized scientifically.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Erwähnt sei noch, dass aus einer ätherischen Diazomethanlösung sich beim Stehen manchmal minimale Quantitäten eines weissen, flockigen, aus Chloroform krystallisirenden Körpers abscheiden; ... [It should be mentioned that from an ether solution of diazomethane, upon standing, sometimes small quantities of a white, flakey substance precipitate, which can be crystallized with chloroform; ...].[12]: 2643

- ^ Die Abscheidung weisser Flocken aus Diazomethanlösungen erwähnt auch v. Pechmann (diese Berichte 31, 2643);[12] er hat sie aber wegen Substanzmangel nicht untersucht. Ich hatte übrigens Hrn. v. Pechmann schon einige Zeit vor Erscheinen seiner Publication mitgetheilt, dass aus Diazomethan ein fester, weisser Körper entstehe, der sich bei der Analyse als (CH2)x erwiesen habe, worauf mir Hr. v. Pechmann schrieb, dass er den weissen Körper ebensfalls beobachtet, aber nicht untersucht habe. Zuerst erwähnt ist derselbe in der Dissertation meines Schülers. (Hindermann, Zürich (1897), S. 120)[13]: footnote 3 on page 956 [Von Pechmann (these Reports, 31, 2643)[12] also mentioned the precipitation of white flakes from diazomethane solutions; however, due to a scarcity of the material, he didn't investigate it. Incidentally, some time before the appearance of his publication, I had communicated to Mr. von Pechmann that a solid, white substance arose from diazomethane, which on analysis proved to be (CH2)x, whereupon Mr. von Pechmann wrote me that he had likewise observed the white substance, but not investigated it. It is first mentioned in the dissertation of my student. (Hindermann, Zürich (1897), p. 120)].

References

[edit]- ^ Compendium of Polymer Terminology and Nomenclature – IUPAC Recommendations 2008 (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ a b Batra, Kamal (2014). Role of Additives in Linear Low Density Polyethylene (LLDPE) Films. p. 9. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ "poly(ethylene)". ChemSrc.

- ^ Wapler, M. C.; Leupold, J.; Dragonu, I.; von Elverfeldt, D.; Zaitsev, M.; Wallrabe, U. (2014). "Magnetic properties of materials for MR engineering, micro-MR and beyond". JMR. 242: 233–242. arXiv:1403.4760. Bibcode:2014JMagR.242..233W. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.005. PMID 24705364. S2CID 11545416.

- ^ a b Paul L. Splitstone and Walter H. Johnson (20 May 1974). "The Enthalpies of Combustion and Formation of Linear Polyethylene" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards.

- ^ Hemakumara, G. P. T. S.; Madhusankha, T. G. Shamal (2023). "Challenges of Reducing Polythene and Plastic in Sri Lanka: A Case Study of Attanagalla Secretariat Division". Socially Responsible Plastic. Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility. 19: 59–73. doi:10.1108/S2043-052320230000019004. ISBN 978-1-80455-987-1.

- ^ a b c d e Whiteley, Kenneth S.; Heggs, T. Geoffrey; Koch, Hartmut; Mawer, Ralph L.; Immel, Wolfgang (2000). "Polyolefins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_487. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Geyer, Roland; Jambeck, Jenna R.; Law, Kara Lavender (1 July 2017). "Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made". Science Advances. 3 (7) e1700782. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0782G. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700782. PMC 5517107. PMID 28776036.

- ^ "Plastics: The Facts" (PDF). Plastics Europe. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ Yao, Zhuang; Jeong Seong, Hyeon; Jang, Yu-Sin (2022). "Environmental toxicity and decomposition of polyethylene". Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 242: 1, 3. Bibcode:2022EcoES.24213933Y. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113933. PMID 35930840.

- ^ Sepe, Michael (8 April 2024). "Understanding the 'Science' of Color". Plastics Technology. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d von Pechmann, H. (1898). "Ueber Diazomethan und Nitrosoacylamine". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin. 31: 2640–2646.

- ^ a b Bamberger, Eug.; Tschirner, Fred. (1900). "Ueber die Einwirkung von Diazomethan auf β-Arylhydroxylamine" [On the effect of diazomethane on β-arylhydroxylamine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin. 33: 955–959. doi:10.1002/cber.190003301166.

- ^ Bamberger, Eugen; Tschirner, Friedrich (1900). "Ueber die Einwirkung von Diazomethan auf β-Arylhydroxylamine" [On the effect of diazomethane on β-arylhydroxylamine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin. 33: 955–959. doi:10.1002/cber.190003301166.

[page 956]: Eine theilweise – übrigens immer nur minimale – Umwandlung des Diazomethans in Stickstoff und Polymethylen vollzieht sich auch bei ganz andersartigen Reactionen; ... [A partial – incidentally, always only minimal – conversion of diazomethane into nitrogen and polymethylene takes place also during quite different reactions; ...]

- ^ "Winnington history in the making". This is Cheshire. 23 August 2006. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Poly – the all-star plastic". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 91, no. 1. Hearst Magazines. July 1949. pp. 125–129. Retrieved 20 February 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ A History of Union Carbide Corporation (PDF). p. 69.

- ^ Hoff, Ray; Mathers, Robert T. (2010). "Chapter 10. Review of Phillips Chromium Catalyst for Ethylene Polymerization". In Hoff, Ray; Mathers, Robert T. (eds.). Handbook of Transition Metal Polymerization Catalysts. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470504437.ch10. ISBN 978-0-470-13798-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kaiser, Wolfgang (2011). Kunststoffchemie für Ingenieure von der Synthese bis zur Anwendung (3. ed.). München: Hanser. ISBN 978-3-446-43047-1.

- ^ "How to Identify Plastic Materials Using The Burn Test". Boedeker Plastics. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Electrical Properties of Plastic Materials" (PDF). professionalplastics.com. Professional Plastics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Chung, C. I. (2010) Extrusion of Polymers: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed.. Hanser: Munich.

- ^ Victor Ostrovskii et al. Ethylene Polymerization Heat (abstract) in Doklady Chemistry 184(1):103–104. January 1969.

- ^ a b Plastics Design Library (1997). Handbook of Plastics Joining: A Practical Guide. Norwich, New York: Plastics Design Library. p. 326. ISBN 1-884207-17-0.

- ^ Kurtz, Steven M. (2015). UHMWPE Biomaterials Handbook. Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene in Total Joint Replacement and Medical Devices (3rd ed.). Elsevier. p. 3. doi:10.1016/C2013-0-16083-7. ISBN 978-0-323-35435-6.

- ^ Prideaux, Eric (3 November 2007). "Plastic incineration rise draws ire". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Alex Wilkins (29 September 2023). "Waste plastic can be recycled into hydrogen fuel and graphene". New Scientist.

- ^ Kevin Wyss; et al. (11 September 2023). "Synthesis of Clean Hydrogen Gas from Waste Plastic at Zero Net Cost". Advanced Materials. 35 (48) e2306763. Bibcode:2023AdM....3506763W. doi:10.1002/adma.202306763. PMID 37694496.

- ^ a b Tournier, Vincent; Duquesne, Sophie; Guillamot, Frédérique; Cramail, Henri; Taton, Daniel; Marty, Alain; André, Isabelle (2023). "Enzymes' Power for Plastics Degradation" (PDF). Chemical Reviews. 123 (9): 5612–5701. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00644. PMID 36916764.

- ^ "Forscherin entdeckt zufällig Plastik-fressende Raupe". Der Spiegel (in German). 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Briggs, Helen. "Plastic-eating caterpillar could munch waste, scientists say". BBC News. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Kawawada, Karen. "CanadaWorld – WCI student isolates microbe that lunches on plastic bags". The Record.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ Balster, Lori (27 January 2015). "Discovery of plastic-eating bacteria may speed waste reduction". fondriest.com.

- ^ Yang, Jun; Yang, Yu; Wu, Wei-Min; Zhao, Jiao; Jiang, Lei (2014). "Evidence of Polyethylene Biodegradation by Bacterial Strains from the Guts of Plastic-Eating Waxworms". Environmental Science & Technology. 48 (23): 13776–84. Bibcode:2014EnST...4813776Y. doi:10.1021/es504038a. PMID 25384056.

- ^ Cassone, Bryan J.; Grove, Harald C.; Elebute, Oluwadara; Villanueva, Sachi M. P.; LeMoine, Christophe M. R. (11 March 2020). "Role of the intestinal microbiome in low-density polyethylene degradation by caterpillar larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1922) 20200112. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0112. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 7126078. PMID 32126962.

- ^ Sanluis-Verdes, A.; Colomer-Vidal, P.; Rodriguez-Ventura, F.; Bello-Villarino, M.; Spinola-Amilibia, M.; Ruiz-Lopez, E.; Illanes-Vicioso, R.; Castroviejo, P.; Aiese Cigliano, R.; Montoya, M.; Falabella, P.; Pesquera, C.; Gonzalez-Legarreta, L.; Arias-Palomo, E.; Solà, M. (4 October 2022). "Wax worm saliva and the enzymes therein are the key to polyethylene degradation by Galleria mellonella". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 5568. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.5568S. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33127-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9532405. PMID 36195604.

- ^ Royer, Sarah-Jeanne; Ferrón, Sara; Wilson, Samuel T.; Karl, David M. (2018). "Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment". PLOS ONE. 13 (8) e0200574. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300574R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200574. PMC 6070199. PMID 30067755.

- ^ a b Pascu, Cornelia Vasile: Mihaela (2005). Practical guide to polyethylene ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Shawbury: Rapra Technology Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85957-493-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elsner, Peter; Eyerer, Peter; Hirth, Thomas (2012). Domininghaus - Kunststoffe (8. ed.). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. p. 224. ISBN 978-3-642-16173-5.

- ^ Elsner, Peter; Eyerer, Peter; Hirth, Thomas (2012). Kunststoffe Eigenschaften und Anwendungen (8. ed.). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. ISBN 978-3-642-16173-5.

- ^ a b c d e Baur, Erwin; Osswald, Tim A. (October 2013). Saechtling Kunststoff Taschenbuch. Hanser, Carl. p. 443. ISBN 978-3-446-43729-6. Vorschau auf kunststoffe.de

- ^ a b c Whiteley, Kenneth S. (2011). "Polyethylene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_487.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Koltzenburg, Sebastian; Maskos, Michael; Nuyken, Oskar (2014). Polymere: Synthese, Eigenschaften und Anwendungen (1 ed.). Springer Spektrum. p. 406. ISBN 978-3-642-34773-3.

- ^ Chlorsulfoniertes Polyethylen (CSM). ChemgaPedia.de

- ^ "Braskem & Toyota Tsusho start joint marketing activities for green polyethylene from sugar cane" (Press release). yourindustrynews.com. 26 September 2008. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ a b A Guide to IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Compounds (Recommendations 1993) IUPAC, Commission on Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. Blackwell Scientific Publications. 1993. ISBN 978-0-632-03702-5. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ a b Kahovec, J.; Fox, R. B.; Hatada, K. (2002). "Nomenclature of regular single-strand organic polymers (IUPAC Recommendations 2002)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 74 (10): 1921. doi:10.1351/pac200274101921.

- ^ "IUPAC Provisional Recommendations on the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 27 October 2004. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Piringer, Otto G.; Baner, Albert Lawrence (2008). Plastic Packaging: Interactions with Food and Pharmaceuticals (2nd ed.). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31455-3. Retrieved 20 February 2014.[permanent dead link]

- Plastics Design Library (1997). Handbook of Plastics Joining: A Practical Guide (illustrated ed.). William Andrew. ISBN 978-1-884207-17-4. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

External links

[edit]- Polythene's story: The accidental birth of plastic bags

- Polythene Technical Properties & Applications

- Article describing the discovery of Sphingomonas as a biodegrader of plastic bags Archived 5 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Kawawada, Karen, Waterloo Region Record (22 May 2008).

Polyethylene

View on GrokipediaChemical Structure and Nomenclature

Monomer and Basic Polymer Chain

Polyethylene is produced through the addition polymerization of ethylene, the monomer with chemical formula C₂H₄ and structure H₂C=CH₂, a colorless gas at standard temperature and pressure.[9] Ethylene's double bond between the two carbon atoms enables the polymerization reaction, where the pi bond breaks to form new sigma bonds with adjacent monomers, initiating chain growth under catalytic conditions such as Ziegler-Natta or free radical mechanisms.[10] The resulting basic polymer chain consists of a linear sequence of repeating –CH₂–CH₂– units, yielding the general formula –(CH₂–CH₂)ₙ–, where n denotes the degree of polymerization, often exceeding 1,000 for commercial grades, corresponding to molecular weights from tens of thousands to over a million daltons.[1] [11] Each carbon atom in the chain is sp³ hybridized, bonded to two hydrogens and two carbons, forming a flexible, non-polar hydrocarbon backbone with tetrahedral geometry that allows for conformational variations like gauche and trans arrangements.[12] In its ideal form, the polyethylene chain lacks branches or functional groups, distinguishing it as a simple alkane polymer, though real-world synthesis introduces minor variations depending on process conditions.[13]Naming Conventions and Molecular Weight Metrics

Polyethylene is commonly abbreviated as PE in industrial and scientific contexts, with the trivial name "polyethylene" retained for widespread use despite systematic nomenclature alternatives. The source-based IUPAC name is poly(ethene), reflecting its derivation from the ethylene monomer, while the structure-based name is poly(methylene), based on the constitutional repeating unit -CH₂-.[14] [15] This dual nomenclature arises from polymer naming conventions that prioritize either the monomer source or the repeating unit structure, with polyethylene's retained name persisting due to historical and practical adoption in standards like ISO and ASTM.[16] Subtype abbreviations, such as HDPE for high-density polyethylene, follow by prefixing descriptors to PE, though full names expand to reflect density or branching characteristics.[17] Molecular weight metrics for polyethylene are essential for defining its processability and mechanical properties, typically expressed through averages rather than a single value due to polydispersity. The number-average molecular weight (Mₙ) represents the arithmetic mean of chain lengths, calculated as total mass divided by total number of chains, while the weight-average molecular weight (Mₓ) weights longer chains more heavily, given by the sum of (chain mass squared) over total mass.[18] The polydispersity index (PDI = Mₓ/Mₙ) quantifies distribution breadth, with values near 1 indicating narrow distributions from controlled polymerization and higher values (e.g., 5-10) common in free-radical processes yielding branched structures.[19] Characterization methods include gel permeation chromatography (GPC) for absolute Mₓ and full molecular weight distribution via size exclusion, often calibrated against polyethylene standards for accuracy in high-molecular-weight samples.[19] [20] Viscosity-average molecular weight (Mᵥ) derives from intrinsic viscosity measurements in solvents like trichlorobenzene, correlating empirically with chain entanglement. Industrially, melt mass-flow rate (MFR) serves as an inverse proxy for molecular weight, with low MFR (e.g., <1 g/10 min) denoting high-molecular-weight grades suitable for films or pipes, standardized under ASTM D1238.[20] For ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), Mₓ exceeds 3 × 10⁶ g/mol, verified by light scattering or advanced GPC to account for entanglement limiting dissolution.[21]History

Discovery and Early Synthesis

In 1898, German chemist Hans von Pechmann heated diazomethane and obtained a waxy solid with a methylene chain structure akin to polyethylene, though its polymeric composition was not recognized until later analyses.[22] This early material, termed polymethylene, represented an accidental precursor but lacked connection to ethylene polymerization or practical utility.[23] The modern discovery of polyethylene occurred accidentally on March 24, 1933, during experiments by Reginald Gibson and Eric Fawcett at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in Northwich, England.[24] The chemists subjected a mixture of ethylene and benzaldehyde to high pressure (several hundred atmospheres) and temperature (170°C) in a reaction vessel, intending to produce a lubricant.[25] A trace oxygen impurity, likely from a leak, initiated free radical polymerization of pure ethylene, yielding a white, waxy solid identified as polyethylene after purification and analysis.[4] This breakthrough demonstrated the feasibility of synthesizing long-chain hydrocarbons from ethylene under extreme conditions.[26] Initial reproducibility proved challenging due to the uncontrolled role of oxygen initiators, prompting further ICI research.[27] By 1935, Michael Perrin developed a controlled high-pressure process using deliberate peroxide initiators, enabling consistent production of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) without benzaldehyde.[28] This free radical mechanism under pressures of 1000-3000 bar and temperatures of 100-300°C formed branched chains characteristic of early LDPE, setting the stage for industrial scaling.Commercialization and Scale-Up

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) initiated commercial production of polyethylene, branded as "Polythene," with the opening of its first full-scale plant at Wallerscote, England, on September 1, 1939, featuring an initial capacity of 100 tonnes per year.[4] This timing coincided with the outbreak of World War II, which rapidly elevated polyethylene's strategic importance due to its excellent electrical insulation properties, leading to its classified use in coating radar cables for airborne interception systems.[29] Production remained under wartime secrecy, with ICI scaling output to meet military demands, though exact figures were not publicly disclosed until after the war.[26] Following the war's end in 1945, polyethylene was declassified, enabling civilian commercialization and rapid scale-up. ICI expanded domestic facilities, while licensing agreements facilitated international production; in the United States, DuPont began large-scale manufacturing at its Sabine River, Texas plant in 1944, followed by Union Carbide at South Charleston, West Virginia.[26] Post-war applications proliferated in packaging, piping, and consumer goods, driving demand; by the early 1950s, global capacity had surged beyond initial wartime levels, with polyethylene becoming the first plastic to exceed one billion pounds in annual U.S. sales.[30] This expansion was supported by process improvements in high-pressure polymerization for low-density polyethylene (LDPE), allowing economical production for films and moldings.[31] Further scale-up in the 1950s involved innovations like the introduction of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) via Ziegler-Natta catalysis in 1953, which lowered production costs and broadened applications, though initial commercialization built on ICI's LDPE foundation.[32] By the late 1950s, annual global production reached several hundred thousand tonnes, reflecting polyethylene's transition from niche wartime material to a cornerstone of the plastics industry.[33]Post-2000 Innovations and Expansions

Following the maturation of Ziegler-Natta catalysis, post-2000 advancements in polyethylene synthesis centered on metallocene and single-site catalysts, which produced resins with more precise control over molecular architecture, resulting in superior uniformity, reduced gel formation, and enhanced end-use performance such as improved puncture resistance in films. By the early 2000s, these catalysts were economically scaled for commercial production, with Univation Technologies commercializing its bimodal UNIPOL process around 2000 to generate high-density polyethylene (HDPE) in a single reactor, yielding bimodal molecular weight distributions that balanced stiffness and processability for demanding applications like pipes and blow-molded containers. ExxonMobil introduced its Enable series of metallocene polyethylenes in 2008, specifically engineered to replicate the melt strength and optical properties of low-density polyethylene (LDPE)/metallocene linear low-density polyethylene (mLLDPE) blends while using less material, thereby optimizing resource efficiency in flexible packaging.[34][35] A pivotal sustainability-driven innovation emerged with bio-based polyethylene, produced from ethylene derived via dehydration of bio-ethanol sourced from sugarcane, achieving chemical indistinguishability from petrochemical counterparts while incorporating renewable carbon. Braskem pioneered commercial-scale production in 2010 at its Triunfo facility in Brazil, the first such plant globally, with an initial capacity of 200,000 metric tons per year, enabling drop-in replacement in existing infrastructure and spurring further investments in renewable feedstocks amid rising environmental pressures. This development coincided with broader capacity expansions, as global polyethylene production surged from approximately 70 million metric tons in 2000 to over 110 million metric tons by 2023, propelled by Asia-Pacific demand for packaging and infrastructure, where new facilities in China and the Middle East adopted advanced bimodal and metallocene technologies to meet volume growth.[36][37] Parallel efforts addressed end-of-life management through catalytic chemical recycling, with post-2000 research yielding processes to depolymerize polyethylene back to monomers or waxes via hydrogenolysis or pyrolysis, enhancing circularity without compromising virgin resin quality. These innovations, including ExxonMobil's 2020s-era performance polyethylene grades for recyclable full-PE laminates, reflected ongoing refinements in resin design to support higher recycled content while maintaining barrier properties. By 2025, metallocene-capable linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE) capacity exceeded 26 million metric tons annually worldwide, underscoring the technology's dominance in high-value segments.[38][39][40]Physical and Chemical Properties

Mechanical and Thermal Properties

Polyethylene exhibits a range of mechanical properties influenced primarily by its molecular structure, density, and crystallinity. High-density polyethylene (HDPE), with its linear chains and high crystallinity (typically 60-80%), demonstrates greater stiffness and tensile strength compared to branched low-density polyethylene (LDPE), which has lower crystallinity (40-50%) and thus higher ductility but reduced rigidity.[11][41] For HDPE, tensile yield strength ranges from 20 to 31 MPa, Young's modulus from 0.8 to 1 GPa, and elongation at break exceeding 500%.[42] LDPE, by contrast, offers tensile strength around 10 MPa, a lower modulus of approximately 0.2 GPa, and elongation up to 600%, enabling greater flexibility for applications like films.[43] Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), featuring extremely long chains (molecular weight >3 million g/mol), provides exceptional impact resistance and abrasion tolerance, with tensile strength of 20-40 MPa and elongation often >300%, though its modulus remains comparable to HDPE at 0.8-1.6 GPa due to reduced crystallinity from chain entanglement.[44] Thermal properties of polyethylene are characterized by low glass transition temperatures (Tg) and melting points that vary with branching and density. The Tg for HDPE lies between -100°C and -130°C, rendering it rubbery at room temperature, while LDPE's Tg is around -60°C to -120°C.[45][46] Melting points range from 105-115°C for LDPE to 120-130°C for HDPE and UHMWPE, reflecting higher crystallinity in linear variants that requires more energy to disrupt ordered regions.[11] Thermal conductivity is low across types, at 0.33 W/m·K for LDPE and 0.45-0.52 W/m·K for HDPE, making polyethylene an effective insulator; specific heat capacity is approximately 1.9-2.3 kJ/kg·K for HDPE and similar for LDPE.[47][48] These properties stem from the non-polar hydrocarbon backbone, which limits intermolecular forces and heat transfer efficiency.| Property | LDPE | HDPE | UHMWPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | ~10 | 20-31 | 20-40 |

| Young's Modulus (GPa) | ~0.2 | 0.8-1 | 0.8-1.6 |

| Elongation at Break (%) | 500-600 | >500 | >300 |

| Melting Point (°C) | 105-115 | 120-130 | 120-130 |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | 0.33 | 0.45-0.52 | ~0.4-0.5 |

Electrical, Optical, and Barrier Properties

Polyethylene exhibits favorable electrical properties that render it an effective insulator in applications such as cable coatings and electronic components. Its dielectric constant typically ranges from 2.25 to 2.3 at frequencies around 1 MHz, reflecting low polarizability due to the non-polar nature of its hydrocarbon chains.[49] Dielectric strength varies by type and thickness but generally falls between 20 and 50 kV/mm for low- and high-density variants, with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) often achieving around 27 kV/mm under standard conditions.[50] High-density polyethylene (HDPE) demonstrates comparable or slightly higher values in some formulations, up to 70 kV/mm in tested composites, attributed to denser packing that reduces void formation under electric fields.[51] These properties stem from polyethylene's high volume resistivity, exceeding 10^15 ohm-cm, minimizing current leakage.[52] Optically, polyethylene is characterized by a refractive index of 1.51–1.52 for LDPE and 1.53–1.54 for HDPE at visible wavelengths, influenced by density and crystallinity.[53] Lower-density forms like LDPE display greater transparency due to smaller crystallite sizes that scatter less light, allowing visible light transmittance up to 50% in thin films, whereas HDPE's higher crystallinity results in translucency with reduced light transmission.[54] This variation arises from light scattering at crystalline-amorphous interfaces, with overall mid-infrared transparency supporting uses in optical components, though visible opacity limits clarity in denser grades.[55] In barrier performance, polyethylene provides excellent resistance to water vapor, with low transmission rates (typically 1–2 g·m⁻²·day⁻¹ at 38°C and 90% RH for 25 μm films) owing to its hydrophobic, non-polar structure that repels moisture.[56] However, it shows moderate to poor barrier to non-polar gases like oxygen, with permeability coefficients around 10–20 barrer (or transmission rates of 1500–6000 cm³·m⁻²·day⁻¹·atm⁻¹ for LDPE films), enabling diffusion through amorphous regions.[57] HDPE outperforms LDPE in both moisture and gas barriers due to higher crystallinity reducing free volume for permeation, though neither suffices for highly oxygen-sensitive packaging without additives or laminates.[58]| Property | LDPE | HDPE |

|---|---|---|

| Dielectric Constant (1 MHz) | ~2.26 | ~2.34 |

| Dielectric Strength (kV/mm) | ~27 | ~20–70 |

| Refractive Index | 1.51–1.52 | 1.53–1.54 |

| Water Vapor Barrier (qualitative) | Good | Excellent |

| Oxygen Permeability | Higher (~2000–6000 cm³/m²/day/atm) | Lower |

Chemical Resistance and Stability

Polyethylene exhibits strong chemical resistance to a broad array of dilute acids, bases, salts, and aqueous solutions at room temperature, attributable to its non-polar, saturated hydrocarbon structure that minimizes interactions with polar reagents.[60][61] High-density polyethylene (HDPE) generally outperforms low-density polyethylene (LDPE) in this regard, showing minimal swelling or degradation when exposed to hydrochloric acid, dilute sulfuric acid, or sodium hydroxide up to concentrations of 30-50% for extended periods.[62][63] Resistance to organic solvents is more variable: polyethylene tolerates aliphatic hydrocarbons like hexane or ethanol with only moderate swelling and no dissolution at 20-50°C, but aromatic solvents such as benzene or toluene induce significant softening, permeation, or dissolution above 60°C, particularly in LDPE variants.[64][65] Strong oxidizing agents, including concentrated nitric acid (>70%), fuming sulfuric acid, or halogens like chlorine, cause oxidative degradation, chain scission, or embrittlement even at ambient conditions, compromising long-term integrity.[64][7] In terms of stability, polyethylene maintains inertness in neutral aqueous environments and resists hydrolysis or microbial attack under standard conditions, with no significant weight loss or mechanical property decline after immersion in water or dilute electrolytes for years.[60][66] However, exposure to environmental stressors like combined chemical permeation and mechanical stress can induce environmental stress cracking (ESC), especially in branched LDPE, where tensile strength may drop by 50% or more after 1000 hours in surfactants or detergents at 50°C.[65][67] Oxidative stability is limited without additives; pure polyethylene undergoes slow auto-oxidation in air above 100°C, forming hydroperoxides that lead to carbonyl groups and reduced molecular weight, as evidenced by FTIR spectroscopy showing peak increases at 1710 cm⁻¹ after accelerated aging tests.[7]| Chemical Class | Resistance Level (HDPE at 20-50°C) | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dilute Acids | Excellent | HCl (37%), H₂SO₄ (dilute), HNO₃ (dilute) | No degradation after 30 days immersion.[63][66] |

| Bases | Excellent | NaOH (50%), NH₄OH (30%) | Minimal swelling; suitable for storage tanks.[60] |

| Alcohols/Glycols | Good | Ethanol (100%), Ethylene glycol | Slight weight gain (<5%) but retains strength.[60][68] |

| Aromatic Solvents | Poor | Benzene, Toluene | Dissolution or severe swelling >60°C.[64] |

| Oxidants | Poor | Concentrated HNO₃, Cl₂ | Oxidative attack; avoid prolonged contact.[64][61] |