Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pyridine

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Pyridine[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Azabenzene | |||

| Other names

Azine

Azinine | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.464 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C5H5N | |||

| Molar mass | 79.102 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid[2] | ||

| Odor | Nauseating, fish-like[3] | ||

| Density | 0.9819 g/mL (20 °C)[4] | ||

| Melting point | −41.63 °C (−42.93 °F; 231.52 K)[4] | ||

| Boiling point | 115.2 °C (239.4 °F; 388.3 K)[4] | ||

| Miscible[4] | |||

| log P | 0.65[5] | ||

| Vapor pressure | 16 mmHg (20 °C)[3] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 5.23 (pyridinium)[6] | ||

| Conjugate acid | Pyridinium | ||

| −48.7·10−6 cm3/mol[7] | |||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.166 W/(m·K)[8] | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.5095 (20 °C)[4] | ||

| Viscosity | 0.879 cP (25 °C)[9] | ||

| 2.215 D[10] | |||

| Thermochemistry[11] | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

132.7 J/(mol·K) | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

100.2 kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.782 MJ/mol | ||

| Hazards[15] | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Low to moderate hazard[13] | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

[12] [12]

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H225, H302, H312, H315, H319, H332[12] | |||

| P210, P280, P301+P312, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340+P312, P305+P351+P338[12] | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 20 °C (68 °F; 293 K)[16] | ||

| 482 °C (900 °F; 755 K)[16] | |||

| Explosive limits | 1.8–12.4%[3] | ||

Threshold limit value (TLV)

|

5 ppm (TWA) | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

891 mg/kg (rat, oral) 1500 mg/kg (mouse, oral) 1580 mg/kg (rat, oral)[14] | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

9000 ppm (rat, 1 hr)[14] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 5 ppm (15 mg/m3)[3] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 5 ppm (15 mg/m3)[3] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

1000 ppm[3] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related amines

|

Picoline Quinoline | ||

Related compounds

|

Aniline Pyrimidine Piperidine | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Pyridine (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Pyridine is a basic heterocyclic organic compound with the chemical formula C5H5N. It is structurally related to benzene, with one methine group (=CH−) replaced by a nitrogen atom (=N−). It is a highly flammable, weakly alkaline, water-miscible liquid with a distinctive, unpleasant fish-like smell. Pyridine is colorless, but older or impure samples can appear yellow. The pyridine ring occurs in many commercial compounds, including agrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, and vitamins. Historically, pyridine was produced from coal tar. As of 2016, it is synthesized on the scale of about 20,000 tons per year worldwide.[2]

Properties

[edit]

Physical properties

[edit]

Pyridine is diamagnetic. Its critical parameters are: pressure 5.63 MPa, temperature 619 K and volume 248 cm3/mol.[18] In the temperature range 340–426 K its vapor pressure p can be described with the Antoine equation

where T is temperature, A = 4.16272, B = 1371.358 K and C = −58.496 K.[19]

Structure

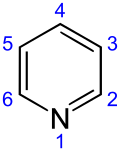

[edit]Pyridine ring forms a C5N hexagon. Slight variations of the C−C and C−N distances as well as the bond angles are observed.

Pyridine crystallizes in an orthorhombic crystal system with space group Pna21 and lattice parameters a = 1752 pm, b = 897 pm, c = 1135 pm, and 16 formula units per unit cell (measured at 153 K). For comparison, crystalline benzene is also orthorhombic, with space group Pbca, a = 729.2 pm, b = 947.1 pm, c = 674.2 pm (at 78 K), but the number of molecules per cell is only 4.[17] This difference is partly related to the lower symmetry of the individual pyridine molecule (C2v vs D6h for benzene). A trihydrate (pyridine·3H2O) is known; it also crystallizes in an orthorhombic system in the space group Pbca, lattice parameters a = 1244 pm, b = 1783 pm, c = 679 pm and eight formula units per unit cell (measured at 223 K).[20]

Spectroscopy

[edit]The optical absorption spectrum of pyridine in hexane consists of bands at the wavelengths of 195, 251, and 270 nm. With respective extinction coefficients (ε) of 7500, 2000, and 450 L·mol−1·cm−1, these bands are assigned to π → π*, π → π*, and n → π* transitions. The compound displays very low fluorescence.[21]

The 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum shows signals for α-(δ 8.5), γ-(δ7.5) and β-protons (δ7). By contrast, the proton signal for benzene is found at δ7.27. The larger chemical shifts of the α- and γ-protons in comparison to benzene result from the lower electron density in the α- and γ-positions, which can be derived from the resonance structures. The situation is rather similar for the 13C NMR spectra of pyridine and benzene: pyridine shows a triplet at δ(α-C) = 150 ppm, δ(β-C) = 124 ppm and δ(γ-C) = 136 ppm, whereas benzene has a single line at 129 ppm. All shifts are quoted for the solvent-free substances.[22] Pyridine is conventionally detected by the gas chromatography and mass spectrometry methods.[23]

Bonding

[edit]

Pyridine has a conjugated system of six π electrons that are delocalized over the ring. The molecule is planar and, thus, follows the Hückel criteria for aromatic systems. In contrast to benzene, the electron density is not evenly distributed over the ring, reflecting the negative inductive effect of the nitrogen atom. For this reason, pyridine has a dipole moment and a weaker resonant stabilization than benzene (resonance energy 117 kJ/mol in pyridine vs. 150 kJ/mol in benzene).[24]

The ring atoms in the pyridine molecule are sp2-hybridized. The nitrogen is involved in the π-bonding aromatic system using its unhybridized p orbital. The lone pair is in an sp2 orbital, projecting outward from the ring in the same plane as the σ bonds. As a result, the lone pair does not contribute to the aromatic system but importantly influences the chemical properties of pyridine, as it easily supports bond formation via an electrophilic attack.[25] However, because of the separation of the lone pair from the aromatic ring system, the nitrogen atom cannot exhibit a positive mesomeric effect.

Many analogues of pyridine are known where N is replaced by other heteroatoms from the same column of the Periodic Table of Elements (see figure below). Substitution of one C–H in pyridine with a second N gives rise to the diazine heterocycles (C4H4N2), with the names pyridazine, pyrimidine, and pyrazine.

Bond lengths and angles of benzene, pyridine, phosphorine, arsabenzene, stibabenzene, and bismabenzene

Atomic orbitals in pyridine

Resonance structures of pyridine

Atomic orbitals in protonated pyridine

History

[edit]

Impure pyridine was undoubtedly prepared by early alchemists by heating animal bones and other organic matter,[26] but the earliest documented reference is attributed to the Scottish scientist Thomas Anderson.[27][28] In 1849, Anderson examined the contents of the oil obtained through high-temperature heating of animal bones.[28] Among other substances, he separated from the oil a colorless liquid with unpleasant odor, from which he isolated pure pyridine two years later. He described it as highly soluble in water, readily soluble in concentrated acids and salts upon heating, and only slightly soluble in oils.

Owing to its flammability, Anderson named the new substance pyridine, after Greek: πῦρ (pyr) meaning fire. The suffix idine was added in compliance with the chemical nomenclature, as in toluidine, to indicate a cyclic compound containing a nitrogen atom.[29][30]

The chemical structure of pyridine was determined decades after its discovery. Wilhelm Körner (1869)[31] and James Dewar (1871)[32][33] suggested that, in analogy between quinoline and naphthalene, the structure of pyridine is derived from benzene by substituting one C–H unit with a nitrogen atom.[34][35] The suggestion by Körner and Dewar was later confirmed in an experiment where pyridine was reduced to piperidine with sodium in ethanol.[36][37] In 1876, William Ramsay combined acetylene and hydrogen cyanide into pyridine in a red-hot iron-tube furnace.[38] This was the first synthesis of a heteroaromatic compound.[23][39]

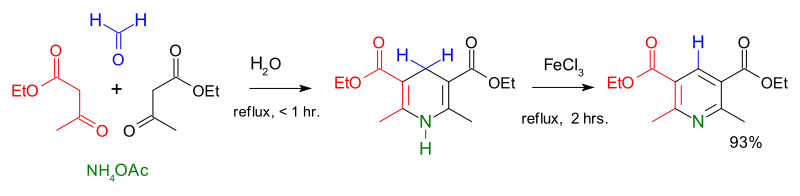

The first major synthesis of pyridine derivatives was described in 1881 by Arthur Rudolf Hantzsch.[40] The Hantzsch pyridine synthesis typically uses a 2:1:1 mixture of a β-keto acid (often acetoacetate), an aldehyde (often formaldehyde), and ammonia or its salt as the nitrogen donor. First, a double hydrogenated pyridine is obtained, which is then oxidized to the corresponding pyridine derivative. Emil Knoevenagel showed that asymmetrically substituted pyridine derivatives can be produced with this process.[41]

The contemporary methods of pyridine production had a low yield, and the increasing demand for the new compound urged to search for more efficient routes. A breakthrough came in 1924 when the Russian chemist Aleksei Chichibabin invented a pyridine synthesis reaction, which was based on inexpensive reagents.[42] This method is still used for the industrial production of pyridine.[2]

Occurrence

[edit]Pyridine is not abundant in nature, except for the leaves and roots of belladonna (Atropa belladonna)[43] and in marshmallow (Althaea officinalis).[44] Pyridine derivatives, however, are often part of biomolecules such as alkaloids.

In daily life, trace amounts of pyridine are components of the volatile organic compounds that are produced in roasting and canning processes, e.g. in fried chicken,[45] sukiyaki,[46] roasted coffee,[47] potato chips,[48] and fried bacon.[49] Traces of pyridine can be found in Beaufort cheese,[50] vaginal secretions,[51] black tea,[52] saliva of those suffering from gingivitis,[53] and sunflower honey.[54]

-

4-bromopyridine

-

2,2'-bipyridine

-

pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid)

-

General form of the pyridinium cation

Trace amounts of up to 16 μg/m3 have been detected in tobacco smoke.[23] Minor amounts of pyridine are released into environment from some industrial processes such as steel manufacture,[55] processing of oil shale, coal gasification, coking plants and incinerators.[23] The atmosphere at oil shale processing plants can contain pyridine concentrations of up to 13 μg/m3,[56] and 53 μg/m3 levels were measured in the groundwater in the vicinity of a coal gasification plant.[57] According to a study by the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, about 43,000 Americans work in contact with pyridine.[58]

In foods

[edit]Pyridine has historically been added to foods to give them a bitter flavour, although this practise is now banned in the U.S.[59][60] It may still be added to ethanol to make it unsuitable for drinking.[61]

Production

[edit]Historically, pyridine was extracted from coal tar or obtained as a byproduct of coal gasification. The process is labor-consuming and inefficient: coal tar contains only about 0.1% pyridine,[62] and therefore a multi-stage purification was required, which further reduced the output. Nowadays, most pyridines are synthesized from ammonia, aldehydes, and nitriles, a few combinations of which are suited for pyridine itself. Various name reactions are also known, but they are not practiced on scale.[2]

In 1989, 26,000 tonnes of pyridine was produced worldwide. Other major derivatives are 2-, 3-, 4-methylpyridines and 5-ethyl-2-methylpyridine. The combined scale of these alkylpyridines matches that of pyridine itself.[2] Among the largest 25 production sites for pyridine, eleven are located in Europe (as of 1999).[23] The major producers of pyridine include Evonik Industries, Rütgers Chemicals, Jubilant Life Sciences, Imperial Chemical Industries, and Koei Chemical.[2] Pyridine production significantly increased in the early 2000s, with an annual production capacity of 30,000 tonnes in mainland China alone.[63] The US–Chinese joint venture Vertellus is currently the world leader in pyridine production.[64]

Chichibabin synthesis

[edit]The Chichibabin pyridine synthesis was reported in 1924 and the basic approach underpins several industrial routes.[42] In its general form, the reaction involves the condensation reaction of aldehydes, ketones, α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds, or any combination of the above, in ammonia or ammonia derivatives. Application of the Chichibabin pyridine synthesis suffer from low yields, often about 30%,[65] however the precursors are inexpensive. In particular, unsubstituted pyridine is produced from formaldehyde and acetaldehyde. First, acrolein is formed in a Knoevenagel condensation from the acetaldehyde and formaldehyde. The acrolein then condenses with acetaldehyde and ammonia to give dihydropyridine, which is oxidized to pyridine. This process is carried out in a gas phase at 400–450 °C. Typical catalysts are modified forms of alumina and silica. The reaction has been tailored to produce various methylpyridines.[2]

Dealkylation and decarboxylation of substituted pyridines

[edit]Pyridine can be prepared by dealkylation of alkylated pyridines, which are obtained as byproducts in the syntheses of other pyridines. The oxidative dealkylation is carried out either using air over vanadium(V) oxide catalyst,[66] by vapor-dealkylation on nickel-based catalyst,[67][68] or hydrodealkylation with a silver- or platinum-based catalyst.[69] Yields of pyridine up to be 93% can be achieved with the nickel-based catalyst.[2] Pyridine can also be produced by the decarboxylation of nicotinic acid with copper chromite.[70]

Bönnemann cyclization

[edit]

The trimerization of a part of a nitrile molecule and two parts of acetylene into pyridine is called Bönnemann cyclization. This modification of the Reppe synthesis can be activated either by heat or by light. While the thermal activation requires high pressures and temperatures, the photoinduced cycloaddition proceeds at ambient conditions with CoCp2(cod) (Cp = cyclopentadienyl, cod = 1,5-cyclooctadiene) as a catalyst, and can be performed even in water.[71] A series of pyridine derivatives can be produced in this way. When using acetonitrile as the nitrile, 2-methylpyridine is obtained, which can be dealkylated to pyridine.

Other methods

[edit]The Kröhnke pyridine synthesis provides a fairly general method for generating substituted pyridines using pyridine itself as a reagent which does not become incorporated into the final product. The reaction of pyridine with bromomethyl ketones gives the related pyridinium salt, wherein the methylene group is highly acidic. This species undergoes a Michael-like addition to α,β-unsaturated carbonyls in the presence of ammonium acetate to undergo ring closure and formation of the targeted substituted pyridine as well as pyridinium bromide.[72]

The Ciamician–Dennstedt rearrangement[73] entails the ring-expansion of pyrrole with dichlorocarbene to 3-chloropyridine.[74][75][76]

In the Gattermann–Skita synthesis,[77] a malonate ester salt reacts with dichloromethylamine.[78]

Other methods include the Boger pyridine synthesis and Diels–Alder reaction of an alkene and an oxazole.[79]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Several pyridine derivatives play important roles in biological systems. While its biosynthesis is not fully understood, nicotinic acid (vitamin B3) occurs in some bacteria, fungi, and mammals. Mammals synthesize nicotinic acid through oxidation of the amino acid tryptophan, where an intermediate product, the aniline derivative kynurenine, creates a pyridine derivative, quinolinate and then nicotinic acid. On the contrary, the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Escherichia coli produce nicotinic acid by condensation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and aspartic acid.[80]

Reactions

[edit]The reactivity of pyridine can be distinguished for three chemical groups. With electrophiles, electrophilic substitution takes place where pyridine expresses aromatic properties. With nucleophiles, pyridine reacts at positions 2 and 4 and thus behaves similar to imines and carbonyls. The reaction with many Lewis acids results in the addition to the nitrogen atom of pyridine, which is similar to the reactivity of tertiary amines. The ability of pyridine and its derivatives to oxidize, forming amine oxides (N-oxides), is also a feature of tertiary amines.[81]

Because of the electronegative nitrogen in the pyridine ring, pyridine enters less readily into electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions than benzene derivatives.[82] Instead, in terms of its reactivity, pyridine resembles nitrobenzene.[83] That is, pyridine reacts most easily in nucleophilic substitution, as evidenced by the ease of metalation by strong organometallic bases.[84][85][contradictory]

The nitrogen center of pyridine features a basic lone pair of electrons. This lone pair does not overlap with the aromatic π-system ring, consequently pyridine is basic, having chemical properties similar to those of tertiary amines. Protonation gives the conjugate acid, a pyridinium cation, C5H5NH+. The pKa of pyridinium is 5.25. The structures of pyridine and pyridinium are almost identical, but the latter is isoelectronic with benzene.[86] Pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) is an illustrative pyridinium salt; it is produced by treating pyridine with p-toluenesulfonic acid.

In addition to protonation, pyridine undergoes N-centred alkylation, acylation, and N-oxidation.

Electrophilic substitutions

[edit]Owing to the decreased electron density in the aromatic system, electrophilic substitutions are suppressed in pyridine and its derivatives. Friedel–Crafts alkylation or acylation, usually fail for pyridine because they lead only to the addition at the nitrogen atom. Substitutions usually occur at the 3-position, which is the most electron-rich carbon atom in the ring and is, therefore, more susceptible to an electrophilic addition.

Direct nitration of pyridine is sluggish.[87][88] Pyridine derivatives wherein the nitrogen atom is screened sterically and/or electronically can be obtained by nitration with nitronium tetrafluoroborate (NO2BF4). In this way, 3-nitropyridine can be obtained via the synthesis of 2,6-dibromopyridine followed by nitration and debromination.[89][90]

Sulfonation of pyridine is even more difficult than nitration. However, pyridine-3-sulfonic acid can be obtained. Reaction with the SO3 group also facilitates addition of sulfur to the nitrogen atom, especially in the presence of a mercury(II) sulfate catalyst.[84][91]

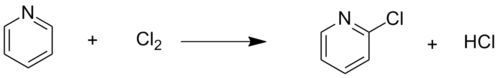

In contrast to the sluggish nitrations and sulfonations, the bromination and chlorination of pyridine proceed well.[2]

Some electrophilic substitutions on the pyridine are usefully effected using pyridine N-oxide followed by deoxygenation. Addition of oxygen suppresses further reactions at nitrogen atom and promotes substitution at the 2- and 4-carbons. The oxygen atom can then be removed, e.g., using zinc dust.[92]

Nucleophilic substitutions

[edit]In contrast to benzene ring, pyridine efficiently supports several nucleophilic substitutions. The reason for this is relatively lower electron density of the carbon atoms of the ring. These reactions include substitutions with elimination of a hydride ion and elimination-additions with formation of an intermediate aryne configuration, and usually proceed at the 2- or 4-position.[84][85]

The hydride ion is a poor leaving group and direct substitution on the bare pyridine ring occurs in only a few heterocyclic reactions. They include the Chichibabin reaction, which yields pyridine derivatives aminated at the 2-position. Here, sodium amide is used as the nucleophile yielding 2-aminopyridine. The hydride ion released in this reaction combines with a proton of an available amino group, forming a hydrogen molecule.[85][93]

Substitutions occur more easily not with bare pyridine but with pyridine modified with bromine, chlorine, fluorine, or sulfonic acid fragments that then become a leaving group. Fluorine is the best leaving group for the substitution with organolithium compounds. The nucleophilic attack compounds may be alkoxides, thiolates, amines, and ammonia (at elevated pressures).[94]

Analogous to benzene, nucleophilic substitutions to pyridine can result in the formation of pyridyne intermediates as heteroaryne. For this purpose, pyridine derivatives can be eliminated with good leaving groups using strong bases such as sodium and potassium tert-butoxide. The subsequent addition of a nucleophile to the triple bond has low selectivity, and the result is a mixture of the two possible adducts.[84]

Radical reactions

[edit]Pyridine supports a series of radical reactions, which is used in its dimerization to bipyridines. Radical dimerization of pyridine with elemental sodium or Raney nickel selectively yields 4,4'-bipyridine,[95] or 2,2'-bipyridine,[96] which are important precursor reagents in the chemical industry. One of the name reactions involving free radicals is the Minisci reaction. It can produce 2-tert-butylpyridine upon reacting pyridine with pivalic acid, silver nitrate and ammonium in sulfuric acid with a yield of 97%.[84]

Reactions on the nitrogen atom

[edit]

Lewis acids easily add to the nitrogen atom of pyridine, forming pyridinium salts. The reaction with alkyl halides leads to alkylation of the nitrogen atom. This creates a positive charge in the ring that increases the reactivity of pyridine to both oxidation and reduction. The Zincke reaction is used for the selective introduction of radicals in pyridinium compounds (it has no relation to the chemical element zinc).

Oxidation of pyridine occurs at nitrogen to give pyridine N-oxide. The oxidation can be achieved with peracids:[97]

- C5H5N + RCO3H → C5H5NO + RCO2H

Hydrogenation and reduction

[edit]

Piperidine is produced by hydrogenation of pyridine with a nickel-, cobalt-, or ruthenium-based catalyst at elevated temperatures.[98] The hydrogenation of pyridine to piperidine releases 193.8 kJ/mol,[99] which is slightly less than the energy of the hydrogenation of benzene (205.3 kJ/mol).[99]

Partially hydrogenated derivatives are obtained under milder conditions. For example, reduction with lithium aluminium hydride yields a mixture of 1,4-dihydropyridine, 1,2-dihydropyridine, and 2,5-dihydropyridine.[100] Selective synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridine is achieved in the presence of organometallic complexes of magnesium and zinc,[101] and (Δ3,4)-tetrahydropyridine is obtained by electrochemical reduction of pyridine.[102] Birch reduction converts pyridine to dihydropyridines.[103]

Lewis basicity and coordination compounds

[edit]Pyridine is a Lewis base, donating its pair of electrons to a Lewis acid. Its Lewis base properties are discussed in the ECW model. Its relative donor strength toward a series of acids, versus other Lewis bases, can be illustrated by C-B plots.[104][105] One example is the sulfur trioxide pyridine complex (melting point 175 °C), which is a sulfation agent used to convert alcohols to sulfate esters. Pyridine-borane (C5H5NBH3, melting point 10–11 °C) is a mild reducing agent.

Transition metal pyridine complexes are numerous.[106][107] Typical octahedral complexes have the stoichiometry MCl2(py)4 and MCl3(py)3. Octahedral homoleptic complexes of the type M(py)+6 are rare or tend to dissociate pyridine. Numerous square planar complexes are known, such as Crabtree's catalyst.[108] The pyridine ligand replaced during the reaction is restored after its completion.

The η6 coordination mode, as occurs in η6 benzene complexes, is observed only in sterically encumbered derivatives that block the nitrogen center.[109]

Applications

[edit]Pesticides and pharmaceuticals

[edit]The main use of pyridine is as a precursor to the herbicides paraquat and diquat.[2] The first synthesis step of insecticide chlorpyrifos consists of the chlorination of pyridine. Pyridine is also the starting compound for the preparation of pyrithione-based fungicides.[23] Cetylpyridinium and laurylpyridinium, which can be produced from pyridine with a Zincke reaction, are used as antiseptic in oral and dental care products.[61] Pyridine is easily attacked by alkylating agents to give N-alkylpyridinium salts. One example is cetylpyridinium chloride.

It is also used in the textile industry to improve network capacity of cotton.[61]

Laboratory use

[edit]Pyridine is used as a polar, basic, low-reactive solvent, for example in Knoevenagel condensations.[23][111] It is especially suitable for the dehalogenation, where it acts as the base for the elimination reaction. In esterifications and acylations, pyridine activates the carboxylic acid chlorides and anhydrides. Even more active in these reactions are the derivatives 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) and 4-(1-pyrrolidinyl) pyridine. Pyridine is also used as a base in some condensation reactions.[112]

Reagents

[edit]

As a base, pyridine can be used as the Karl Fischer reagent, but it is usually replaced by alternatives with a more pleasant odor, such as imidazole.[113]

Pyridinium chlorochromate, pyridinium dichromate, and the Collins reagent (the complex of chromium(VI) oxide) are used for the oxidation of alcohols.[114]

Hazards

[edit]Pyridine is a toxic, flammable liquid with a strong and unpleasant fishy odour. Its odour threshold of 0.04 to 20 ppm is close to its threshold limit of 5 ppm for adverse effects,[115] thus most (but not all) adults will be able to tell when it is present at harmful levels. Pyridine easily dissolves in water and harms both animals and plants in aquatic systems.[116]

Fire

[edit]Pyridine has a flash point of 20 °C and is therefore highly flammable. Combustion produces toxic fumes which can include bipyridines, nitrogen oxides, and carbon monoxide.[12]

Short-term exposure

[edit]Pyridine can cause chemical burns on contact with the skin and its fumes may be irritating to the eyes or upon inhalation.[117] Pyridine depresses the nervous system giving symptoms similar to intoxication with vapor concentrations of above 3600 ppm posing a greater health risk.[2] The effects may have a delayed onset of several hours and include dizziness, headache, lack of coordination, nausea, salivation, and loss of appetite. They may progress into abdominal pain, pulmonary congestion and unconsciousness.[118] The lowest known lethal dose (LDLo) for the ingestion of pyridine in humans is 500 mg/kg.

Long-term exposure

[edit]Prolonged exposure to pyridine may result in liver, heart and kidney damage.[12][23][119] Evaluations as a possible carcinogenic agent showed that there is inadequate evidence in humans for the carcinogenicity of pyridine, although there is sufficient evidence in experimental animals. Therefore, IARC considers pyridine as possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B).[120]

Metabolism

[edit]

Exposure to pyridine would normally lead to its inhalation and absorption in the lungs and gastrointestinal tract, where it either remains unchanged or is metabolized. The major products of pyridine metabolism are N-methylpyridiniumhydroxide, which are formed by N-methyltransferases (e.g., pyridine N-methyltransferase), as well as pyridine N-oxide, and 2-, 3-, and 4-hydroxypyridine, which are generated by the action of monooxygenase. In humans, pyridine is metabolized only into N-methylpyridiniumhydroxide.[12][119]

Environmental fate

[edit]Pyridine is readily degraded by bacteria to ammonia and carbon dioxide.[121] The unsubstituted pyridine ring degrades more rapidly than picoline, lutidine, chloropyridine, or aminopyridines,[122] and a number of pyridine degraders have been shown to overproduce riboflavin in the presence of pyridine.[123] Ionizable N-heterocyclic compounds, including pyridine, interact with environmental surfaces (such as soils and sediments) via multiple pH-dependent mechanisms, including partitioning to soil organic matter, cation exchange, and surface complexation.[124] Such adsorption to surfaces reduces bioavailability of pyridines for microbial degraders and other organisms, thus slowing degradation rates and reducing ecotoxicity.[125]

Nomenclature

[edit]The systematic name of pyridine, within the Hantzsch–Widman nomenclature recommended by the IUPAC, is azinine. However, systematic names for simple compounds are used very rarely; instead, heterocyclic nomenclature follows historically established common names. IUPAC discourages the use of azinine/azine in favor of pyridine.[126] The numbering of the ring atoms in pyridine starts at the nitrogen (see infobox). An allocation of positions by letter of the Greek alphabet (α-γ) and the substitution pattern nomenclature common for homoaromatic systems (ortho, meta, para) are used sometimes. Here α (ortho), β (meta), and γ (para) refer to the 2, 3, and 4 position, respectively. The systematic name for the pyridine derivatives is pyridinyl, wherein the position of the substituted atom is preceded by a number. However, the historical name pyridyl is encouraged by the IUPAC and used instead of the systematic name.[127] The cationic derivative formed by the addition of an electrophile to the nitrogen atom is called pyridinium.

See also

[edit]- 6-membered aromatic rings with one carbon replaced by another group: borabenzene, silabenzene, germabenzene, stannabenzene, pyridine, phosphorine, arsabenzene, stibabenzene, bismabenzene, pyrylium, thiopyrylium, selenopyrylium, telluropyrylium

- 6-membered rings with two nitrogen atoms: diazines

- 6-membered rings with three nitrogen atoms: triazines

- 6-membered rings with four nitrogen atoms: tetrazines

- 6-membered rings with five nitrogen atoms: pentazine

- 6-membered rings with six nitrogen atoms: hexazine

References

[edit]- ^ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 141. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shimizu, S.; Watanabe, N.; Kataoka, T.; Shoji, T.; Abe, N.; Morishita, S.; Ichimura, H. "Pyridine and Pyridine Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_399. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b c d e f NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0541". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, p. 3.474

- ^ Haynes, p. 5.176

- ^ Haynes, p. 5.95

- ^ Haynes, p. 3.579

- ^ Haynes, p. 6.258

- ^ Haynes, p. 6.246

- ^ Haynes, p. 9.65

- ^ Haynes, pp. 5.34, 5.67

- ^ a b c d e f Record of Pyridine in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ^ Pyridine: main hazards, precautions and toxicity

- ^ a b "Pyridine". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Pyridine MSDS". fishersci.com. Fisher. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ a b Haynes, p. 15.19

- ^ a b Cox, E. (1958). "Crystal Structure of Benzene". Reviews of Modern Physics. 30 (1): 159–162. Bibcode:1958RvMP...30..159C. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.30.159.

- ^ Haynes, p. 6.80

- ^ McCullough, J. P.; Douslin, D. R.; Messerly, J. F.; Hossenlopp, I. A.; Kincheloe, T. C.; Waddington, Guy (1957). "Pyridine: Experimental and Calculated Chemical Thermodynamic Properties between 0 and 1500 K.; a Revised Vibrational Assignment". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 79 (16): 4289. doi:10.1021/ja01573a014.

- ^ Mootz, D. (1981). "Crystal structures of pyridine and pyridine trihydrate". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 75 (3): 1517–1522. Bibcode:1981JChPh..75.1517M. doi:10.1063/1.442204.

- ^ Varras, Panayiotis C.; Gritzapis, Panagiotis S.; Fylaktakidou, Konstantina C. (17 January 2018). "An explanation of the very low fluorescence and phosphorescence in pyridine: a CASSCF/CASMP2 study". Molecular Physics. 116 (2): 154–170. doi:10.1080/00268976.2017.1371800.

- ^ Joule, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pyridine (PDF). Washington DC: OSHA. 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Joule, p. 7

- ^ Sundberg, Francis A. Carey; Richard J. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry : Part A: Structure and Mechanisms (5. ed.). Berlin: Springer US. p. 794. ISBN 978-0-387-68346-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weissberger, A.; Klingberg, A.; Barnes, R. A.; Brody, F.; Ruby, P.R. (1960). Pyridine and its Derivatives. Vol. 1. New York: Interscience.

- ^ Anderson, Thomas (1849). "On the constitution and properties of picoline, a new organic base from coal-tar". Transactions of the Royal Societies of Edinburgh University. 16 (2): 123–136. doi:10.1017/S0080456800024984. S2CID 100301190. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b Anderson, T. (1849). "Producte der trocknen Destillation thierischer Materien" [Products of the dry distillation of animal matter]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 70: 32–38. doi:10.1002/jlac.18490700105. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Thomas (1851). "On the products of the destructive distillation of animal substances. Part II". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 20 (2): 247–260. doi:10.1017/S0080456800033160. S2CID 102143621. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2018. From p. 253: "Pyridine. The first of these bases, to which I give the name of pyridine, … "

- ^ Anderson, T. (1851). "Ueber die Producte der trocknen Destillation thierischer Materien" [On the products of dry distillation of animal matter]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 80: 44–65. doi:10.1002/jlac.18510800104. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Koerner, W. (1869). "Synthèse d'une base isomère à la toluidine" [Synthesis of a base [that is] isomeric to toluidine]. Giornale di Scienze Naturali ed Economiche (Journal of Natural Science and Economics (Palermo, Italy)) (in French). 5: 111–114.

- ^ Dewar, James (27 January 1871). "On the oxidation products of picoline". Chemical News. 23: 38–41. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Rocke, Alan J. (1988). "Koerner, Dewar and the Structure of Pyridine". Bulletin for the History of Chemistry. 2 (2): 4. doi:10.70359/bhc1988n02p004. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Ladenburg, Albert (1911). Lectures on the history of the development of chemistry since the time of Lavoisier (PDF). pp. 283–287. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Bansal, Raj K. (1999). Heterocyclic Chemistry. New Age International. p. 216. ISBN 81-224-1212-2.

- ^ Ladenburg, A. (1884). "Synthese des Piperidins" [Synthesis of piperidine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 17: 156. doi:10.1002/cber.18840170143. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Ladenburg, A. (1884). "Synthese des Piperidins und seiner Homologen" [Synthesis of piperidine and its homologues]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 17: 388–391. doi:10.1002/cber.188401701110. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Ramsay, William (1876). "On picoline and its derivatives". Philosophical Magazine. 5th series. 2 (11): 269–281. doi:10.1080/14786447608639105. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "A. Henninger, aus Paris. 12. April 1877". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (Correspondence). 10: 727–737. 1877. doi:10.1002/cber.187701001202.

- ^ Hantzsch, A. (1881). "Condensationsprodukte aus Aldehydammoniak und ketonartigen Verbindungen" [Condensation products from aldehyde ammonia and ketone-type compounds]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 14 (2): 1637–1638. doi:10.1002/cber.18810140214. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Knoevenagel, E.; Fries, A. (1898). "Synthesen in der Pyridinreihe. Ueber eine Erweiterung der Hantzsch'schen Dihydropyridinsynthese" [Syntheses in the pyridine series. On an extension of the Hantzsch dihydropyridine synthesis]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 31: 761–767. doi:10.1002/cber.189803101157. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ a b Chichibabin, A. E. (1924). "Über Kondensation der Aldehyde mit Ammoniak zu Pyridinebasen" [On condensation of aldehydes with ammonia to make pyridines]. Journal für Praktische Chemie. 107: 122. doi:10.1002/prac.19241070110. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Burdock, G. A., ed. (1995). Fenaroli's Handbook of Flavor Ingredients. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-2710-5.

- ^ Täufel, A.; Ternes, W.; Tunger, L.; Zobel, M. (2005). Lebensmittel-Lexikon (4th ed.). Behr. p. 450. ISBN 3-89947-165-2.

- ^ Tang, Jian; Jin, Qi Zhang; Shen, Guo Hui; Ho, Chi Tang; Chang, Stephen S. (1983). "Isolation and identification of volatile compounds from fried chicken". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 31 (6): 1287. Bibcode:1983JAFC...31.1287T. doi:10.1021/jf00120a035.

- ^ Shibamoto, Takayuki; Kamiya, Yoko; Mihara, Satoru (1981). "Isolation and identification of volatile compounds in cooked meat: sukiyaki". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 29 (1): 57–63. Bibcode:1981JAFC...29...57S. doi:10.1021/jf00103a015.

- ^ Aeschbacher, HU; Wolleb, U; Löliger, J; Spadone, JC; Liardon, R (1989). "Contribution of coffee aroma constituents to the mutagenicity of coffee". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 27 (4): 227–232. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(89)90160-9. PMID 2659457.

- ^ Buttery, Ron G.; Seifert, Richard M.; Guadagni, Dante G.; Ling, Louisa C. (1971). "Characterization of Volatile Pyrazine and Pyridine Components of Potato Chips". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 19 (5). Washington, DC: ACS: 969–971. Bibcode:1971JAFC...19..969B. doi:10.1021/jf60177a020.

- ^ Ho, Chi Tang; Lee, Ken N.; Jin, Qi Zhang (1983). "Isolation and identification of volatile flavor compounds in fried bacon". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 31 (2): 336. Bibcode:1983JAFC...31..336H. doi:10.1021/jf00116a038.

- ^ Dumont, Jean Pierre; Adda, Jacques (1978). "Occurrence of sesquiterpene in mountain cheese volatiles". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 26 (2): 364. Bibcode:1978JAFC...26..364D. doi:10.1021/jf60216a037.

- ^ Labows, John N. Jr.; Warren, Craig B. (1981). "Odorants as Chemical Messengers". In Moskowitz, Howard R. (ed.). Odor Quality and Chemical Structure. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. pp. 195–210. doi:10.1021/bk-1981-0148.fw001. ISBN 9780841206076.

- ^ Vitzthum, Otto G.; Werkhoff, Peter; Hubert, Peter (1975). "New volatile constituents of black tea flavor". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 23 (5): 999. doi:10.1021/jf60201a032.

- ^ Kostelc, J. G.; Preti, G.; Nelson, P. R.; Brauner, L.; Baehni, P. (1984). "Oral Odors in Early Experimental Gingivitis". Journal of Periodontal Research. 19 (3): 303–312. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb00821.x. PMID 6235346.

- ^ Täufel, A.; Ternes, W.; Tunger, L.; Zobel, M. (2005). Lebensmittel-Lexikon (4th ed.). Behr. p. 226. ISBN 3-89947-165-2.

- ^ Junk, G. A.; Ford, C. S. (1980). "A review of organic emissions from selected combustion processes". Chemosphere. 9 (4): 187. Bibcode:1980Chmsp...9..187J. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(80)90079-X. OSTI 5295035.

- ^ Hawthorne, Steven B.; Sievers, Robert E. (1984). "Emissions of organic air pollutants from shale oil wastewaters". Environmental Science & Technology. 18 (6): 483–90. Bibcode:1984EnST...18..483H. doi:10.1021/es00124a016. PMID 22247953.

- ^ Stuermer, Daniel H.; Ng, Douglas J.; Morris, Clarence J. (1982). "Organic contaminants in groundwater near to underground coal gasification site in northeastern Wyoming". Environmental Science & Technology. 16 (9): 582–7. Bibcode:1982EnST...16..582S. doi:10.1021/es00103a009. PMID 22284199.

- ^ National Occupational Exposure Survey 1981–83. Cincinnati, OH: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, National Institute for Occuptional Safety and Health.

- ^ 83 FR 50490

- ^ "FDA Removes 7 Synthetic Flavoring Substances from Food Additives List". 5 October 2018. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ a b c RÖMPP Online – Version 3.5. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme. 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Gossauer, A. (2006). Struktur und Reaktivität der Biomoleküle. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 488. ISBN 3-906390-29-2.

- ^ "Pyridine's Development in China". AgroChemEx. 11 May 2010. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "About Vertellus". vertellus.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Frank, R. L.; Seven, R. P. (1949). "Pyridines. IV. A Study of the Chichibabin Synthesis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 71 (8): 2629–2635. Bibcode:1949JAChS..71.2629F. doi:10.1021/ja01176a008.

- ^ DE patent 1917037, Swift, Graham, "Verfahren zur Herstellung von Pyridin und Methylpyridinen", issued 1968

- ^ JP patent 7039545, Nippon Kayaku, "Electrically-assisted bicycle, driving system thereof, and manufacturing method", issued 1967

- ^ BE patent 758201, Koei Chemical, "Procede de preparation de bases pyridiques", issued 1969

- ^ Mensch, F. (1969). "Hydrodealkylierung von Pyridinbasen bei Normaldruck". Erdöl Kohle Erdgas Petrochemie. 2: 67–71.

- ^ Scott, T. A. (1967). "A method for the Degradation of Radioactive Nicotinic Acid". Biochemical Journal. 102 (1): 87–93. doi:10.1042/bj1020087. PMC 1270213. PMID 6030305.

- ^ Behr, A. (2008). Angewandte homogene Katalyse. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 722. ISBN 978-3-527-31666-3.

- ^ Kroehnke, Fritz (1976). "The Specific Synthesis of Pyridines and Oligopyridines". Synthesis. 1976 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1055/s-1976-23941. S2CID 95238046..

- ^ Ciamician, G. L.; Dennstedt, M. (1881). "Ueber die Einwirkung des Chloroforms auf die Kaliumverbindung Pyrrols". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 14 (1): 1153–1163. doi:10.1002/cber.188101401240. ISSN 0365-9496.

- ^ Skell, P. S.; Sandler, R. S. (1958). "Reactions of 1,1-Dihalocyclopropanes with Electrophilic Reagents. Synthetic Route for Inserting a Carbon Atom Between the Atoms of a Double Bond". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 80 (8): 2024. Bibcode:1958JAChS..80.2024S. doi:10.1021/ja01541a070.

- ^ Jones, R. L.; Rees, C. W. (1969). "Mechanism of heterocyclic ring expansions. Part III. Reaction of pyrroles with dichlorocarbene". Journal of the Chemical Society C: Organic (18): 2249. doi:10.1039/J39690002249.

- ^ Gambacorta, A.; Nicoletti, R.; Cerrini, S.; Fedeli, W.; Gavuzzo, E. (1978). "Trapping and structure determination of an intermediate in the reaction between 2-methyl-5-t-butylpyrrole and dichlorocarbene". Tetrahedron Letters. 19 (27): 2439. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)94795-1.

- ^ Gattermann, L.; Skita, A. (1916). "Eine Synthese von Pyridin-Derivaten" [A synthesis of pyridine derivatives]. Chemische Berichte. 49 (1): 494–501. doi:10.1002/cber.19160490155. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Gattermann–Skita". Institute of Chemistry, Skopje. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006.

- ^ Karpeiskii, Y.; Florent'ev V. L. (1969). "Condensation of Oxazoles with Dienophiles — a New Method for the Synthesis of Pyridine Bases". Russian Chemical Reviews. 38 (7): 540–546. Bibcode:1969RuCRv..38..540K. doi:10.1070/RC1969v038n07ABEH001760. S2CID 250852496.

- ^ Tarr, J. B.; Arditti, J. (1982). "Niacin Biosynthesis in Seedlings of Zea mays". Plant Physiology. 69 (3): 553–556. doi:10.1104/pp.69.3.553. PMC 426252. PMID 16662247.

- ^ Milcent, R.; Chau, F. (2002). Chimie organique hétérocyclique: Structures fondamentales. EDP Sciences. pp. 241–282. ISBN 2-86883-583-X.

- ^ Sundberg, Francis A. Carey; Richard J. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry : Part A: Structure and Mechanisms (5. ed.). Berlin: Springer US. p. 794. ISBN 978-0-387-68346-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campaigne, E. (1986). "Adrien Albert and the Rationalization of Heterocyclic chemistry". J. Chem. Educ. 63 (10): 860. Bibcode:1986JChEd..63..860C. doi:10.1021/ed063p860.

- ^ a b c d e Joule, pp. 125–141

- ^ a b c Davies, D. T. (1992). Aromatic Heterocyclic Chemistry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855660-8.

- ^ Krygowski, T. M.; Szatyowicz, H.; Zachara, J. E. (2005). "How H-bonding Modifies Molecular Structure and π-Electron Delocalization in the Ring of Pyridine/Pyridinium Derivatives Involved in H-Bond Complexation". J. Org. Chem. 70 (22): 8859–8865. doi:10.1021/jo051354h. PMID 16238319.

- ^ Bakke, Jan M.; Hegbom, Ingrid (1994). "Dinitrogen Pentoxide-Sulfur Dioxide, a New nitrate ion system". Acta Chemica Scandinavica. 48: 181–182. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.48-0181.

- ^ Ono, Noboru; Murashima, Takashi; Nishi, Keiji; Nakamoto, Ken-Ichi; Kato, Atsushi; Tamai, Ryuji; Uno, Hidemitsu (2002). "Preparation of Novel Heteroisoindoles from nitropyridines and Nitropyridones". Heterocycles. 58: 301. doi:10.3987/COM-02-S(M)22.

- ^ Duffy, Joseph L.; Laali, Kenneth K. (1991). "Aprotic Nitration (NO+

2BF−

4) of 2-Halo- and 2,6-Dihalopyridines and Transfer-Nitration Chemistry of Their N-Nitropyridinium Cations". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 56 (9): 3006. doi:10.1021/jo00009a015. - ^ Joule, p. 126

- ^ Möller, Ernst Friedrich; Birkofer, Leonhard (1942). "Konstitutionsspezifität der Nicotinsäure als Wuchsstoff bei Proteus vulgaris und Streptobacterium plantarum" [Constitutional specificity of nicotinic acid as a growth factor in Proteus vulgaris and Streptobacterium plantarum]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 75 (9): 1108. doi:10.1002/cber.19420750912.

- ^ Campeau, Louis-Charles; Fagnou, Keith (2011). "Synthesis of 2-aryl Pyridines By Palladium-catalyzed Direct Arylation of Pyridine N-oxides". Org. Synth. 88: 22. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.088.0022.

- ^ Shreve, R. Norris; Riechers, E. H.; Rubenkoenig, Harry; Goodman, A. H. (1940). "Amination in the Heterocyclic Series by Sodium amide". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 32 (2): 173. doi:10.1021/ie50362a008.

- ^ Joule, p. 133

- ^ Badger, G; Sasse, W (1963). "The Action of Metal Catalysts on Pyridines". Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry Volume 2. Vol. 2. pp. 179–202. doi:10.1016/S0065-2725(08)60749-7. ISBN 9780120206025. PMID 14279523.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Sasse, W. H. F. (1966). "2,2'-bipyridine". Organic Syntheses. 46: 5–8. doi:10.1002/0471264180.os046.02.

- ^ Mosher, H. S.; Turner, L.; Carlsmith, A. (1953). "Pyridine-N-oxide". Org. Synth. 33: 79. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.033.0079.

- ^ Eller, K.; Henkes, E.; Rossbacher, R.; Hoke, H. "Amines, aliphatic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b Cox, J. D.; Pilcher, G. (1970). Thermochemistry of Organic and Organometallic Compounds. New York: Academic Press. pp. 1–636. ISBN 0-12-194350-X.

- ^ Tanner, Dennis D.; Yang, Chi Ming (1993). "On the structure and mechanism of formation of the Lansbury reagent, lithium tetrakis(N-dihydropyridyl) aluminate". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 58 (7): 1840. doi:10.1021/jo00059a041.

- ^ De Koning, A.; Budzelaar, P. H. M.; Boersma, J.; Van Der Kerk, G. J. M. (1980). "Specific and selective reduction of aromatic nitrogen heterocycles with the bis-pyridine complexes of bis(1,4-dihydro-1-pyridyl)zinc and bis(1,4-dihydro-1-pyridyl)magnesium". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 199 (2): 153. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)83849-8.

- ^ Ferles, M. (1959). "Studies in the pyridine series. II. Ladenburg and electrolytic reductions of pyridine bases". Collection of Czechoslovak Chemical Communications. 24 (4). Institute of Organic Chemistry & Biochemistry: 1029–1035. doi:10.1135/cccc19591029.

- ^ Donohoe, Timothy J.; McRiner, Andrew J.; Sheldrake, Peter (2000). "Partial Reduction of Electron-Deficient Pyridines". Organic Letters. 2 (24): 3861–3863. doi:10.1021/ol0065930. PMID 11101438.

- ^ Laurence, C. and Gal, J-F. (2010) Lewis Basicity and Affinity Scales, Data and Measurement. Wiley. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-470-74957-9

- ^ Cramer, R. E.; Bopp, T. T. (1977). "Graphical display of the enthalpies of adduct formation for Lewis acids and bases". Journal of Chemical Education. 54: 612–613. doi:10.1021/ed054p612. The plots shown in this paper used older parameters. Improved E&C parameters are listed in ECW model.

- ^ Nakamoto, K. (1997). Infrared and Raman spectra of Inorganic and Coordination compounds. Part A (5th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-16394-5.

- ^ Nakamoto, K. (31 July 1997). Infrared and Raman spectra of Inorganic and Coordination compounds. Part B (5th ed.). p. 24. ISBN 0-471-16392-9.

- ^ Crabtree, Robert (1979). "Iridium compounds in catalysis". Accounts of Chemical Research. 12 (9): 331–337. doi:10.1021/ar50141a005.

- ^ Elschenbroich, C. (2008). Organometallchemie (6th ed.). Vieweg & Teubner. pp. 524–525. ISBN 978-3-8351-0167-8.

- ^ "Environmental and health criteria for paraquat and diquat". Geneva: World Health Organization. 1984. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Carey, Francis A.; Sundberg, Richard J. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Part B: Reactions and Synthesis (5th ed.). New York: Springer. p. 147. ISBN 978-0387683546.

- ^ Sherman, A. R. (2004). "Pyridine". In Paquette, L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. e-EROS (Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis). New York: J. Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rp280. ISBN 0471936235.

- ^ "Wasserbestimmung mit Karl-Fischer-Titration" [Water analysis with the Karl Fischer titration] (PDF). Jena University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- ^ Tojo, G.; Fernandez, M. (2006). Oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes and ketones: a guide to current common practice. New York: Springer. pp. 28, 29, 86. ISBN 0-387-23607-4.

- ^ "Pyridine MSDS" (PDF). Alfa Aesar. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ "Database of the (EPA)". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Aylward, G (2008). SI Chemical Data (6th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-81638-7.

- ^ International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (22 August 2000). "Pyridine Summary & Evaluation". IARC Summaries & Evaluations. IPCS INCHEM. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b Bonnard, N.; Brondeau, M. T.; Miraval, S.; Pillière, F.; Protois, J. C.; Schneider, O. (2011). "Pyridine" (PDF). Fiche Toxicologique (in French). INRS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2019). Some chemicals that cause tumours of the urinary tract in rodents (PDF). International Agency for Research on Cancer. Lyon, France. pp. 173–198. ISBN 978-92-832-0186-1. OCLC 1086392170. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sims, G. K.; O'Loughlin, E. J. (1989). "Degradation of pyridines in the environment". CRC Critical Reviews in Environmental Control. 19 (4): 309–340. Bibcode:1989CRvEC..19..309S. doi:10.1080/10643388909388372.

- ^ Sims, G. K.; Sommers, L.E. (1986). "Biodegradation of pyridine derivatives in soil suspensions". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 5 (6): 503–509. Bibcode:1986EnvTC...5..503S. doi:10.1002/etc.5620050601.

- ^ Sims, G. K.; O'Loughlin, E.J. (1992). "Riboflavin production during growth of Micrococcus luteus on pyridine". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 58 (10): 3423–3425. Bibcode:1992ApEnM..58.3423S. doi:10.1128/AEM.58.10.3423-3425.1992. PMC 183117. PMID 16348793.

- ^ Bi, E.; Schmidt, T. C.; Haderlein, S. B. (2006). "Sorption of heterocyclic organic compounds to reference soils: column studies for process identification". Environ Sci Technol. 40 (19): 5962–5970. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.5962B. doi:10.1021/es060470e. PMID 17051786.

- ^ O'Loughlin, E. J; Traina, S. J.; Sims, G. K. (2000). "Effects of sorption on the biodegradation of 2-methylpyridine in aqueous suspensions of reference clay minerals". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 19 (9): 2168–2174. Bibcode:2000EnvTC..19.2168O. doi:10.1002/etc.5620190904. S2CID 98654832.

- ^ Powell, W. H. (1983). "Revision of the extended Hantzsch-Widman system of nomenclature for hetero mono-cycles" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 55 (2): 409–416. doi:10.1351/pac198855020409. S2CID 4686578. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ Hellwinkel, D. (1998). Die systematische Nomenklatur der Organischen Chemie (4th ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 45. ISBN 3-540-63221-2.

Bibliography

[edit]- Sundberg, Francis A. Carey; Richard J. (2007). Advanced Organic Chemistry : Part A: Structure and Mechanisms (5. ed.). Berlin: Springer US. ISBN 978-0-387-68346-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781498754293.

- Joule, J. A.; Mills, K. (2010). Heterocyclic Chemistry (5th ed.). Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3300-5.