Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

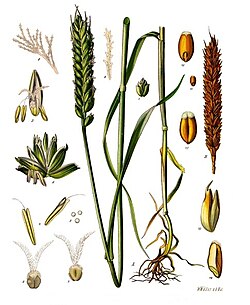

Wheat

View on Wikipedia

| Wheat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Pooideae |

| Tribe: | Triticeae |

| Genus: | Triticum L.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Triticum aestivum | |

| Species[2] | |

Wheat is a group of wild and domesticated grasses of the genus Triticum (/ˈtrɪtɪkəm/).[3] They are cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known wheat species and hybrids include the most widely grown common wheat (T. aestivum), spelt, durum, emmer, einkorn, and Khorasan or Kamut. The archaeological record suggests that wheat was first cultivated in the regions of the Fertile Crescent around 9600 BC.

Wheat is grown on a larger area of land than any other food crop (220.7 million hectares or 545 million acres in 2021). World trade in wheat is greater than that of all other crops combined. In 2021, world wheat production was 771 million tonnes (850 million short tons), making it the second most-produced cereal after maize (known as corn in North America and Australia; wheat is often called corn in countries including Britain).[4] Since 1960, world production of wheat and other grain crops has tripled and is expected to grow further through the middle of the 21st century. Global demand for wheat is increasing because of the usefulness of gluten to the food industry.

Wheat is an important source of carbohydrates. Globally, it is the leading source of vegetable proteins in human food, having a protein content of about 13%, which is relatively high compared to other major cereals but relatively low in protein quality (supplying essential amino acids). When eaten as the whole grain, wheat is a source of multiple nutrients and dietary fibre. In a small part of the general population, gluten – which comprises most of the protein in wheat – can trigger coeliac disease, noncoeliac gluten sensitivity, gluten ataxia, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Description

[edit]

Wheat is a stout grass of medium to tall height. Its stem is jointed and usually hollow, forming a straw. There can be many stems on one plant. It has long narrow leaves, their bases sheathing the stem, one above each joint. At the top of the stem is the flower head, containing some 20 to 100 flowers. Each flower contains both male and female parts.[5] The flowers are wind-pollinated, with over 99% of pollination events being self-pollinations and the rest cross-pollinations.[6] The flower is housed in a pair of small leaflike glumes. The two (male) stamens and (female) stigmas protrude outside the glumes. The flowers are grouped into spikelets, each with between two and six flowers. Each fertilised carpel develops into a wheat grain or berry; botanically a caryopsis fruit, it is often called a seed. The grains ripen to a golden yellow; a head of grain is called an ear.[5]

Leaves emerge from the shoot apical meristem in a telescoping fashion until the transition to reproduction i.e. flowering.[7] The last leaf produced by a wheat plant is known as the flag leaf. It is denser and has a higher photosynthetic rate than other leaves, to supply carbohydrate to the developing ear. In temperate countries the flag leaf, along with the second and third highest leaves on the plant, supply the majority of carbohydrate in the grain; their condition is critical for crop yield.[8][9] Wheat is unusual in having more stomata on the upper (adaxial) side of the leaf, than on the under (abaxial) side.[10] It has been theorised that this might be an effect of having been cultivated longer than any other plant.[11] Winter wheat generally produces up to 15 leaves per shoot, and spring wheat up to 9;[12] winter crops may have up to 35 tillers (shoots) per plant (depending on cultivar).[12]

Wheat roots are among the deepest of arable crops, extending as far down as 2 metres (6 ft 7 in).[13] While the roots of a wheat plant are growing, the plant accumulates an energy store in its stem, in the form of fructans,[14] which helps the plant to yield under drought and disease pressure,[15] but there is a trade-off between root growth and stem non-structural carbohydrate reserves. Root growth is likely to be prioritised in drought-adapted crops, while stem non-structural carbohydrate is prioritised in varieties developed for countries where disease is a bigger issue.[16]

Depending on variety, wheat may be awned or not. Producing awns incurs a cost in grain number,[17] but wheat awns photosynthesise more efficiently than leaves with regards to water usage,[18] so awns are much more frequent in varieties of wheat grown in hot drought-prone countries than those in temperate countries. For this reason, awned varieties could become more widespread due to climate change. In Europe, wheat's climate resilience has declined.[19]

History

[edit]

Domestication

[edit]Hunter-gatherers in West Asia harvested wild wheats for thousands of years before they were domesticated,[20] perhaps as early as 21,000 BC,[21] but they formed a minor component of their diets.[22] In this phase of pre-domestication cultivation, early cultivars were spread around the region and slowly developed the traits that came to characterise their domesticated forms.[23]

Repeated harvesting and sowing of the grains of wild grasses led to the creation of domestic strains, as mutant forms ('sports') of wheat were more amenable to cultivation. In domesticated wheat, grains are larger, and the seeds (inside the spikelets) remain attached to the ear by a toughened rachis during harvesting.[24] In wild strains, a more fragile rachis allows the ear to shatter easily, dispersing the spikelets.[25] Selection for larger grains and non-shattering heads by farmers might not have been deliberately intended, but simply have occurred because these traits made gathering the seeds easier; nevertheless such 'incidental' selection was an important part of crop domestication. As the traits that improve wheat as a food source involve the loss of the plant's natural seed dispersal mechanisms, highly domesticated strains of wheat cannot survive in the wild.[26]

Wild einkorn wheat (T. monococcum subsp. boeoticum) grows across Southwest Asia in open parkland and steppe environments.[27] It comprises three distinct races, only one of which, native to Southeast Anatolia, was domesticated.[28] The main feature that distinguishes domestic einkorn from wild is that its ears do not shatter without pressure, making it dependent on humans for dispersal and reproduction.[27] It also tends to have wider grains.[27] Wild einkorn was collected at sites such as Tell Abu Hureyra (c. 10,700–9000 BC) and Mureybet (c. 9800–9300 BC), but the earliest archaeological evidence for the domestic form comes after c. 8800 BC in southern Turkey, at Çayönü, Cafer Höyük, and possibly Nevalı Çori.[27] Genetic evidence indicates that it was domesticated in multiple places independently.[28]

Wild emmer wheat (T. turgidum subsp. dicoccoides) is less widespread than einkorn, favouring the rocky basaltic and limestone soils found in the hilly flanks of the Fertile Crescent.[27] It is more diverse, with domesticated varieties falling into two major groups: hulled or non-shattering, in which threshing separates the whole spikelet; and free-threshing, where the individual grains are separated. Both varieties probably existed in prehistory, but over time free-threshing cultivars became more common.[27] Wild emmer was first cultivated in the southern Levant, as early as 9600 BC.[29][30] Genetic studies have found that, like einkorn, it was domesticated in southeastern Anatolia, but only once.[28][31] The earliest secure archaeological evidence for domestic emmer comes from Çayönü, c. 8300–7600 BC, where distinctive scars on the spikelets indicated that they came from a hulled domestic variety.[27] Slightly earlier finds have been reported from Tell Aswad in Syria, c. 8500–8200 BC, but these were identified using a less reliable method based on grain size.[27]

Early farming

[edit]

Einkorn and emmer are considered two of the founder crops cultivated by the first farming societies in Neolithic West Asia.[27] These communities also cultivated naked wheats (T. aestivum and T. durum) and a now-extinct domesticated form of Zanduri wheat (T. timopheevii),[32] as well as a wide variety of other cereal and non-cereal crops.[33] Wheat was relatively uncommon for the first thousand years of the Neolithic (when barley predominated), but became a staple after around 8500 BC.[33] Early wheat cultivation did not demand much labour. Initially, farmers took advantage of wheat's ability to establish itself in annual grasslands by enclosing fields against grazing animals and re-sowing stands after they had been harvested, without the need to systematically remove vegetation or till the soil.[34] They may also have exploited natural wetlands and floodplains to practice décrue farming, sowing seeds in the soil left behind by receding floodwater.[35][36][37] It was harvested with stone-bladed sickles.[38] The ease of storing wheat and other cereals led farming households to become gradually more reliant on it over time, especially after they developed individual storage facilities that were large enough to hold more than a year's supply.[39]

Wheat grain was stored after threshing, with the chaff removed.[39] It was then processed into flour using ground stone mortars.[40] Bread made from ground einkorn and the tubers of a form of club rush (Bolboschoenus glaucus) was made as early as 12,400 BC.[41] At Çatalhöyük (c. 7100–6000 BC), both wholegrain wheat and flour was used to prepare bread, porridge and gruel.[42][43] Apart from food, wheat may also have been important to Neolithic societies as a source of straw, which could be used for fuel, wicker-making, or wattle and daub construction.[44]

Spread

[edit]Domestic wheat was quickly spread to regions where its wild ancestors did not grow naturally. Emmer was introduced to Cyprus as early as 8600 BC and einkorn c. 7500 BC;[45][46] emmer reached Greece by 6500 BC, Egypt shortly after 6000 BC, and Germany and Spain by 5000 BC.[47] "The early Egyptians were developers of bread and the use of the oven and developed baking into one of the first large-scale food production industries."[48] By 4000 BC, wheat had reached the British Isles and Scandinavia.[49][50][51] Wheat was also cultivated in India around 3500 BC.[52] Wheat likely appeared in China's lower Yellow River around 2600 BC.[53]

The oldest evidence for hexaploid wheat is through DNA analysis of wheat seeds from around 6400–6200 BC at Çatalhöyük.[54] As of 2023,[update] the earliest known wheat with sufficient gluten for yeasted breads is from a granary at Assiros in Macedonia dated to 1350 BC.[55] Wheat continued to spread across Europe and to the Americas in the Columbian exchange. In the British Isles, wheat straw (thatch) was used for roofing in the Bronze Age, remaining in common use until the late 19th century.[56][57] White wheat bread was historically a high status food, but during the nineteenth century it became in Britain an item of mass consumption, displacing oats, barley and rye from diets in the North of the country.[58] After 1860, the expansion of wheat production in the United States flooded the world market, lowering prices by 40%, and made a major contribution to the nutritional welfare of the poor.[59]

-

Sumerian cylinder seal impression dating to c. 3200 BC showing an ensi and his acolyte feeding a sacred herd wheat stalks; Ninurta was an agricultural deity and, in a poem known as the "Sumerian Georgica", he offers detailed advice on farming

-

Threshing of wheat in ancient Egypt

-

Traditional wheat harvesting

India, 2012

Evolution

[edit]Phylogeny

[edit]

Some wheat species are diploid, with two sets of chromosomes, but many are stable polyploids, with four sets (tetraploid) or six (hexaploid).[60] Einkorn is diploid (AA, two complements of seven chromosomes, 2n=14).[61] Most tetraploid wheats (e.g. emmer and durum wheat) are derived from wild emmer. Wild emmer is itself the result of a hybridization between two diploid wild grasses, T. urartu and a wild goatgrass such as Ae. speltoides.[62] The hybridization that formed wild emmer (AABB, four complements of seven chromosomes in two groups, 4n=28) occurred in the wild, long before domestication, and was driven by natural selection. Hexaploid wheats evolved in farmers' fields as wild emmer hybridized with another goatgrass, Ae. squarrosa or Ae. tauschii, to make the hexaploid wheats including bread wheat.[60][63]

A 2007 molecular phylogeny of the wheats gives the following not fully-resolved cladogram of major cultivated species; the large amount of hybridisation makes resolution difficult. Markings like "6N" indicate the polyploidy of each species:[60]

| Triticeae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomy

[edit]

During 10,000 years of cultivation, numerous forms of wheat, many of them hybrids, have developed under a combination of artificial and natural selection. This complexity and diversity of status has led to much confusion in the naming of wheats.[64][65]

The wild species of wheat, along with the domesticated varieties einkorn,[66] emmer[67] and spelt,[68] have hulls. This more primitive morphology (in evolutionary terms) consists of toughened glumes that tightly enclose the grains, and (in domesticated wheats) a semi-brittle rachis that breaks easily on threshing. The result is that when threshed, the wheat ear breaks up into spikelets. To obtain the grain, further processing, such as milling or pounding, is needed to remove the hulls or husks. Hulled wheats are often stored as spikelets because the toughened glumes give good protection against pests of stored grain.[66] In free-threshing (or naked) forms, such as durum wheat and common wheat, the glumes are fragile and the rachis tough. On threshing, the chaff breaks up, releasing the grains.[69]

| Ploidy | Species | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hexaploid 6N |

Common wheat or bread wheat (T. aestivum) | The most widely cultivated species in the world.[70] |

| Spelt (T. spelta) | Largely replaced by bread wheat, but in the 21st century grown, often organically, for artisanal bread and pasta.[71] | |

| Tetraploid 4N |

Durum (T. durum) | Widely used today, and the second most widely cultivated wheat.[70] |

| Emmer (T. turgidum subsp. dicoccum and T. t. conv. durum) | A species cultivated in ancient times, derived from wild emmer, T. dicoccoides, but no longer in widespread use.[72] | |

| Khorasan or Kamut (T. turgidum ssp. turanicum, also called T. turanicum) | An ancient grain type; Khorasan is a historical region in modern-day Afghanistan and the northeast of Iran. The grain is twice the size of modern wheat and has a rich nutty flavor.[73] | |

| Diploid 2N |

Einkorn (T. monococcum) | Domesticated from wild einkorn, T. boeoticum, at the same time as emmer wheat.[74] |

As a food

[edit]Grain classes

[edit]Classification of wheat greatly varies by the producing country.[75]

Argentina's grain classes were formerly related to the production region or port of shipment: Rosafe (grown in Santa Fe province, shipped through Rosario), Bahia Blanca (grown in Buenos Aires and La Pampa provinces and shipped through Bahia Blanca), Buenos Aires (shipped through the port of Buenos Aires). While mostly similar to the US Hard Red Spring wheat, the classification caused inconsistencies, so Argentina introduced three new classes of wheat, with all names using a prefix Trigo Dura Argentina (TDA) and a number.[76] The grain classification in Australia is within the purview of its National Pool Classification Panel. Australia chose to measure the protein content at 11% moisture basis.[77] The decisions on the wheat classification in Canada are coordinated by the Variety Registration Office of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. As in the US system, the eight classes in Western Canada and six classes in Eastern Canada are based on colour, season, and hardness. Uniquely, Canada requires that the varieties should allow for purely visual identification.[78] The classes used in the United States are named by colour, season, and hardness.[79][80][81]

Food value and uses

[edit]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,368 kJ (327 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

71.18 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 0.41 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 12.2 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.54 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

12.61 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 13.1 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Selenium | 70.7 µg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[82] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[83] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wheat is a staple cereal worldwide.[84][61] Raw wheat berries can be ground into flour or, using hard durum wheat only, can be ground into semolina; germinated and dried creating malt; crushed or cut into cracked wheat; parboiled (or steamed), dried, and de-branned into groats, then crushed into bulgur.[85] If the raw wheat is broken into parts at the mill, the outer husk or bran is removed. Wheat is a major ingredient in baked foods, such as bread, rolls, crackers, biscuits, pancakes, pasta, pies, pastries, pizza, cakes, cookies, and muffins; in fried foods, such as doughnuts; in breakfast cereals, gravy, porridge, and muesli; in semolina; and in drinks such as beer, vodka, and boza (a fermented beverage).[86] In manufacturing wheat products, gluten is valuable to impart viscoelastic functional qualities in dough,[87] enabling the preparation of processed foods such as bread, noodles, and pasta.[88][89]

Nutrition

[edit]Raw red winter wheat is 13% water, 71% carbohydrates including 12% dietary fiber, 13% protein, and 2% fat (table). Some 75–80% of the protein content is as gluten.[87] In a reference amount of 100 grams (3.5 oz), wheat provides 1,368 kilojoules (327 kilocalories) of food energy and is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of multiple dietary minerals, such as manganese, phosphorus, magnesium, zinc, and iron (table). The B vitamins, niacin (36% DV), thiamine (33% DV), and vitamin B6 (23% DV), are present in significant amounts (table).

Wheat is a significant source of vegetable proteins in human food, having a relatively high protein content compared to other major cereals.[90] However, wheat proteins have a low quality for human nutrition, according to the DIAAS protein quality evaluation method.[91][92] Though they contain adequate amounts of the other essential amino acids, at least for adults, wheat proteins are deficient in the essential amino acid lysine.[89][93] Because the gluten proteins present in endosperm are particularly poor in lysine, white flours are more deficient in lysine than are whole grains.[89] Plant breeders have sought to develop lysine-rich wheat varieties, without success, as of 2017[update].[94] Supplementation with proteins from other food sources (mainly legumes) is used to compensate for this deficiency.[95][89]

Health advisories

[edit]Consumed worldwide by billions of people, wheat is a significant food for human nutrition, particularly in the least developed countries where wheat products are primary foods.[89][96] When eaten as the whole grain, wheat supplies multiple nutrients and dietary fiber recommended for children and adults.[88][89][97][98] In genetically susceptible people, wheat gluten can trigger coeliac disease.[87][99] Coeliac disease affects about 1% of the general population in developed countries.[99][100] The only known effective treatment is a strict lifelong gluten-free diet.[99] While coeliac disease is caused by a reaction to wheat proteins, it is not the same as a wheat allergy.[99][100] Other diseases triggered by eating wheat are non-coeliac gluten sensitivity[100][101] (estimated to affect 0.5% to 13% of the general population[102]), gluten ataxia, and dermatitis herpetiformis.[101] Certain short-chain carbohydrates present in wheat, FODMAPs (mainly fructose polymers), may be the cause of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. As of 2019[update], FODMAPs explain certain gastrointestinal symptoms, such as bloating, but not the extra-digestive symptoms of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity.[103][104][105] Other wheat proteins, amylase-trypsin inhibitors, appear to activate the innate immune system in coeliac disease and non-coeliac gluten sensitivity.[104][105] These proteins are part of the plant's natural defense against insects and may cause intestinal inflammation in humans.[104][106]

Production and consumption

[edit]Global

[edit]| Country | Millions of tonnes |

|---|---|

| 136.6 | |

| 110.6 | |

| 91.5 | |

| 49.3 | |

| 41.2 | |

| 35.9 | |

| 31.9 | |

| World | 799 |

| Source: UN Food and Agriculture Organization[107] | |

-

Wheat-growing areas of the world

-

Production of wheat (2019)[108]

-

Wheat's share (brown) of world crop production fell in the 21st century.

In 2023, world wheat production was 799 million tonnes, led by China, India, and Russia which collectively provided 42.4% of the world total.[109] As of 2019[update], the largest exporters were Russia (32 million tonnes), United States (27), Canada (23) and France (20), while the largest importers were Indonesia (11 million tonnes), Egypt (10.4) and Turkey (10.0).[110] In 2021, wheat was grown on 220.7 million hectares or 545 million acres worldwide, more than any other food crop.[111] World trade in wheat is greater than for all other crops combined.[112] Global demand for wheat is increasing due to the unique viscoelastic and adhesive properties of gluten proteins, which facilitate the production of processed foods, whose consumption is increasing as a result of the worldwide industrialization process and westernization of diets.[89][113]

19th century

[edit]

Wheat became a central agriculture endeavor in the worldwide British Empire in the 19th century, and remains of great importance in Australia, Canada and India.[115] In Australia, with vast lands and a limited work force, expanded production depended on technological advances, especially irrigation and machinery. By the 1840s there were 900 growers in South Australia. They used "Ridley's Stripper", a reaper-harvester perfected by John Ridley in 1843,[116] to remove the heads of grain. In Canada, modern farm implements made large scale wheat farming possible from the late 1840s. By 1879, Saskatchewan was the center, followed by Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario, as the spread of railway lines allowed easy exports to Britain. By 1910, wheat made up 22% of Canada's exports, rising to 25% in 1930 despite the sharp decline in prices during the Great Depression.[117] Efforts to expand wheat production in South Africa, Kenya and India were stymied by low yields and disease. However, by 2000 India had become the second largest producer of wheat in the world.[118] In the 19th century the American wheat frontier moved rapidly westward. By the 1880s 70% of American exports went to British ports. The first successful grain elevator was built in Buffalo in 1842.[119] The cost of transport fell rapidly. In 1869 it cost 37 cents to transport a bushel of wheat from Chicago to Liverpool; in 1905 it was 10 cents.[120]

Late 20th century yields

[edit]In the 20th century, global wheat output expanded about 5-fold, but until about 1955 most of this reflected increases in wheat crop area, with lesser (about 20%) increases in yield per unit area. After 1955 however, there was a ten-fold increase in the rate of wheat yield improvement per year, and this allowed global wheat production to increase. Thus technological innovation and scientific crop management with synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, irrigation and wheat breeding were the main drivers of wheat output growth in the second half of the century. There were some significant decreases in wheat crop area, for instance in North America.[121] Better seed storage and germination ability (and hence a smaller requirement to retain harvested crop for next year's seed) is another 20th-century technological innovation. In medieval England, farmers saved one-quarter of their wheat harvest as seed for the next crop, leaving only three-quarters for food and feed consumption. By 1999, the global average seed use of wheat was about 6% of output.[122]

21st century

[edit]

In the 21st century, global warming is reducing wheat yield in some places.[123] War[124] and tariffs have disrupted trade.[125] Between 2007 and 2009, concern was raised that wheat production would peak, in the same manner as oil,[126][127][128] possibly causing sustained price rises.[129][130][131] However, at that time global per capita food production had been increasing steadily for decades.[132]

Agronomy

[edit]Growing wheat

[edit]Wheat is an annual crop. It can be planted in autumn and harvested in early summer as winter wheat in climates that are not too severe, or planted in spring and harvested in autumn as spring wheat. It is normally planted after tilling the soil by ploughing and then harrowing to kill weeds and create an even surface. The seeds are then scattered on the surface, or drilled into the soil in rows. Winter wheat lies dormant during a winter freeze. It needs to develop to a height of 10 to 15 cm before the cold intervenes, so as to be able to survive the winter; it requires a period with the temperature at or near freezing, its dormancy then being broken by the thaw or rise in temperature. Spring wheat does not undergo dormancy. Wheat requires a deep soil, preferably a loam with organic matter, and available minerals including soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. An acid and peaty soil is not suitable. Wheat needs some 30 to 38 cm of rain in the growing season to form a good crop of grain.[133]

The farmer may intervene while the crop is growing to add fertilizer, water by irrigation, or pesticides such as herbicides to kill broad-leaved weeds or insecticides to kill insect pests. The farmer may assess soil minerals, soil water, weed growth, or the arrival of pests to decide timely and cost-effective corrective actions, and crop ripeness and water content to select the right moment to harvest. Harvesting involves reaping, cutting the stems to gather the crop; and threshing, breaking the ears to release the grain; both steps are carried out by a combine harvester. The grain is then dried so that it can be stored safe from mould fungi.[133]

Crop development

[edit]

Wheat normally needs between 110 and 130 days between sowing and harvest, depending upon climate, seed type, and soil conditions. Optimal crop management requires that the farmer have a detailed understanding of each stage of development in the growing plants. In particular, spring fertilizers, herbicides, fungicides, and growth regulators are typically applied only at specific stages of plant development. For example, it is currently recommended that the second application of nitrogen is made when the ear (not visible at this stage) is about 1 cm in size (Z31 on Zadoks scale). Knowledge of stages is important to identify periods of higher risk from the climate. Farmers benefit from knowing when the 'flag leaf' (last leaf) appears, as it represents about 75% of photosynthesis during the grain filling period, and so should be preserved from disease or insect attacks to ensure a good yield. Several systems exist to identify crop stages, with the Feekes and Zadoks scales being the most widely used. Each scale describes successive stages reached by the crop during the season.[134] For example, the stage of pollen formation from the mother cell, and the stages between anthesis and maturity, are vulnerable to high temperatures, made worse by water stress.[135]

-

Anthesis stage

-

Late milk stage

-

Right before harvest

Farming techniques

[edit]Technological advances in soil preparation and seed placement at planting time, use of crop rotation and fertilizers to improve plant growth, and advances in harvesting have combined to promote wheat as a viable crop. When the use of seed drills replaced broadcasting sowing of seed in the 18th century, productivity increased.. Yields per unit area increased as crop rotations were applied to land that had long been in cultivation, and the use of fertilizers became widespread.[136]

Improved husbandry has more recently included pervasive automation, starting with the use of threshing machines,[137] and progressing to large and costly machines like the combine harvester which greatly increased productivity.[138] At the same time, better varieties such as Norin 10 wheat, developed in Japan in the 1930s,[139] or the dwarf wheat developed by Norman Borlaug in the Green Revolution, greatly increased yields.[140][141]

Some large wheat grain-producing countries have significant losses after harvest at the farm, because of poor roads, inadequate storage technologies, inefficient supply chains and farmers' inability to bring the produce into retail markets dominated by small shopkeepers. Some 10% of total wheat production is lost at farm level, another 10% is lost because of poor storage and road networks, and more is lost at the retail level.[142]

In the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, as well as North China, irrigation has been a major contributor to increased output. More widely over the last 40 years, a massive increase in fertilizer use together with increased availability of semi-dwarf varieties in developing countries, has greatly increased yields per hectare.[143] In developing countries, use of (mainly nitrogenous) fertilizer increased 25-fold in this period. However, farming systems rely on much more than fertilizer and breeding to improve productivity. A good illustration of this is Australian wheat growing in the southern winter cropping zone, where, despite low rainfall (300 mm), wheat cropping is successful even with relatively little use of nitrogenous fertilizer. This is achieved by crop rotation with leguminous pastures. The inclusion of a canola crop in the rotations has boosted wheat yields by a further 25%.[144] In these low rainfall areas, better use of available soil-water (and better control of soil erosion) is achieved by retaining the stubble after harvesting and by minimizing tillage.[145]

-

The Wheat Field by John Constable, 1816

-

Field ready for harvesting

-

Combine harvester cuts the wheat stems, threshes the wheat, crushes the chaff and blows it across the field, and loads the grain onto a tractor trailer.

Pests and diseases

[edit]Pests and diseases consume 21.47% of the world's wheat crop annually.[146]

Diseases

[edit]

There are many wheat diseases, mainly caused by fungi, bacteria, and viruses.[147] Plant breeding to develop new disease-resistant varieties, and sound crop management practices are important for preventing disease. Fungicides, used to prevent the significant crop losses from fungal disease, can be a significant variable cost in wheat production. Estimates of the amount of wheat production lost owing to plant diseases vary between 10 and 25% in Missouri.[148] A wide range of organisms infect wheat, of which the most important are viruses and fungi.[149]

Pathogens and wheat are in a constant process of coevolution. Spore-producing wheat rusts are substantially adapted towards successful spore propagation, i.e. increasing their basic reproduction number (R0).[150]

The main wheat-disease categories are:

- Seed-borne diseases: these include seed-borne scab, seed-borne Stagonospora (previously known as Septoria), common bunt (stinking smut), and loose smut. These are managed with fungicides.[151]

- Leaf- and head- blight diseases: Powdery mildew, leaf rust, Septoria tritici leaf blotch, Stagonospora (Septoria) nodorum leaf and glume blotch, and Fusarium head scab.[151][152]

- Crown and root rot diseases: Two of the more important of these are 'take-all' and Cephalosporium stripe. Both of these diseases are soil borne.[151]

- Stem rust diseases: Caused by Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici (basidiomycete) fungi e.g. Ug99[153]

- Wheat blast: Caused by Magnaporthe oryzae Triticum.[154]

- Viral diseases: Wheat spindle streak mosaic (yellow mosaic) and barley yellow dwarf are the two most common viral diseases. Control can be achieved by using resistant varieties.[151]

A historically significant disease of cereals including wheat, though commoner in rye is ergot; it is unusual among plant diseases in also causing sickness in humans who ate grain contaminated with the fungus involved, Claviceps purpurea.[155]

Animal pests

[edit]

Among insect pests of wheat is the wheat stem sawfly, a chronic pest in the Northern Great Plains of the United States and in the Canadian Prairies.[156] Wheat is the food plant of the larvae of some Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) species including the flame, rustic shoulder-knot, setaceous Hebrew character and turnip moth. Early in the season, many species of birds and rodents feed upon wheat crops. These animals can cause significant damage to a crop by digging up and eating newly planted seeds or young plants. They can also damage the crop late in the season by eating the grain from the mature spike. Recent post-harvest losses in cereals amount to billions of dollars per year in the United States alone, and damage to wheat by various borers, beetles and weevils is no exception.[157] Rodents can also cause major losses during storage, and in major grain growing regions, field mice numbers can sometimes build up explosively to plague proportions because of the ready availability of food.[158] To reduce the amount of wheat lost to post-harvest pests, Agricultural Research Service scientists have developed an "insect-o-graph", which can detect insects in wheat that are not visible to the naked eye. The device uses electrical signals to detect the insects as the wheat is being milled. The new technology is so precise that it can detect 5–10 infested seeds out of 30,000 good ones.[159]

Breeding objectives

[edit]In traditional agricultural systems, wheat populations consist of landraces, informal and often diverse farmer-maintained populations. Landraces of wheat continue to be important outside America and Europe. Formal wheat breeding began in the nineteenth century, when single line varieties were created by selecting seed from a plant with desired properties. Modern wheat breeding developed early in the twentieth century, linked to the development of Mendelian genetics. The standard method of breeding inbred wheat cultivars is by crossing two lines using hand emasculation, then selfing or inbreeding the progeny. Selections are identified genetically ten or more generations before release as a cultivar.[160]

Major breeding objectives include high grain yield, good quality, disease- and insect resistance and tolerance to abiotic stresses, including mineral, moisture and heat tolerance.[161][162] Wheat has been the subject of mutation breeding, with the use of gamma-, x-rays, ultraviolet light, and harsh chemicals. Since 1960, hundreds of varieties have been created through these methods, mostly in populous countries such as China.[161] Bread wheat with high grain iron and zinc content has been developed through gamma radiation breeding,[163] and through conventional selection breeding.[164] International wheat breeding is led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico. ICARDA is another major public sector international wheat breeder, but it was forced to relocate from Syria to Lebanon in the Syrian Civil War.[165]

For higher yields

[edit]

The presence of certain versions of wheat genes has been important for crop yields. Genes for the 'dwarfing' trait, first used by Japanese wheat breeders to produce Norin 10 short-stalked wheat, have had a huge effect on wheat yields worldwide, and were major factors in the success of the Green Revolution in Mexico and Asia, an initiative led by Norman Borlaug.[166] Dwarfing genes enable the carbon that is fixed in the plant during photosynthesis to be diverted towards seed production, and reduce lodging,[167] when a tall ear stalk falls over in the wind.[168] By 1997, 81% of the developing world's wheat area was planted to semi-dwarf wheats, giving both increased yields and better response to nitrogenous fertilizer.[169]

T. turgidum subsp. polonicum, known for its longer glumes and grains, has been bred into main wheat lines for its grain size effect, and likely has contributed these traits to T. petropavlovskyi and the Portuguese landrace group Arrancada.[170] As with many plants, MADS-box influences flower development, and more specifically, as with other agricultural Poaceae, influences yield. Despite that importance, as of 2021[update] little research has been done into MADS-box and other such spikelet and flower genetics in wheat specifically.[170]

The world record wheat yield is about 17 tonnes per hectare (15,000 pounds per acre), reached in New Zealand in 2017.[171] A project in the UK, led by Rothamsted Research has aimed to raise wheat yields in the country to 20 t/ha (18,000 lb/acre) by 2020, but in 2018 the UK record stood at 16 t/ha (14,000 lb/acre), and the average yield was just 8 t/ha (7,100 lb/acre).[172][173]

For disease resistance

[edit]

Wild grasses in the genus Triticum and related genera, and grasses such as rye have been a source of many disease-resistance traits for cultivated wheat breeding since the 1930s.[174] Some resistance genes have been identified against Pyrenophora tritici-repentis, especially races 1 and 5, those most problematic in Kazakhstan.[175] Wild relative, Aegilops tauschii is the source of several genes effective against TTKSK/Ug99 - Sr33, Sr45, Sr46, and SrTA1662.[176]

- Lr67 is an R gene, a dominant negative for partial adult resistance discovered and molecularly characterized by Moore et al., 2015. As of 2018[update] Lr67 is effective against all races of leaf, stripe, and stem rusts, and powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis). This is produced by a mutation of two amino acids in what is predicted to be a hexose transporter. The result is to reduce glucose uptake.[177]

- Lr34 is widely deployed in cultivars as it confers resistance against leaf- and stripe-rusts, and powdery mildew.[178] It is used intensively in wheat cultivation worldwide.[179][180] It is an ABC transporter,[178][181] producing a 'slow rusting'/adult resistance phenotype.[181]

- Pm8 is a widely used powdery mildew resistance introgressed from rye (Secale cereale).[182] It comes from the rye 1R chromosome, a source of many resistances since the 1960s.[182]

Resistance to Fusarium head blight (FHB, Fusarium ear blight) is an important breeding target. Marker-assisted breeding panels involving kompetitive allele specific PCR can be used. A KASP genetic marker for a pore-forming toxin-like gene provides FHB resistance.[183]

In 2003 the first resistance genes against fungal diseases in wheat were isolated.[184][185] In 2021, novel resistance genes were identified in wheat against powdery mildew and wheat leaf rust.[186][187] Modified resistance genes have been tested in transgenic wheat and barley plants.[188]

To create hybrid vigor

[edit]Because wheat self-pollinates, creating hybrid seed to provide heterosis, hybrid vigor (as in F1 hybrids of maize), is extremely labor-intensive; the high cost of hybrid wheat seed has kept farmers from adopting them widely[189][190] despite nearly 90 years of effort.[191][160] Commercial hybrid wheat seed has been produced using chemical hybridizing agents, plant growth regulators that interfere with pollen development, or naturally occurring cytoplasmic male sterility systems. Hybrid wheat has been a limited commercial success in France, the United States and South Africa.[192]

Synthetic hexaploids made by crossing the wild goatgrass wheat ancestor Aegilops tauschii,[193] and other Aegilops,[194] with durum wheats are being deployed, increasing the genetic diversity of cultivated wheats.[195][196][197]

For gluten content

[edit]Modern bread wheat varieties have been cross-bred to contain greater amounts of gluten.[198][199] However, a 2020 study found no changes in albumin/globulin and gluten content between 1891 and 2010.[200]

For water efficiency

[edit]Stomata (or leaf pores) are involved in both uptake of carbon dioxide gas from the atmosphere and water vapor losses from the leaf due to water transpiration. Basic physiological investigation of these gas exchange processes has yielded carbon isotope based method used for breeding wheat varieties with improved water-use efficiency. These varieties can improve crop productivity in rain-fed dry-land wheat farms.[201]

For insect resistance

[edit]The complex genome of wheat has made its improvement difficult. Comparison of hexaploid wheat genomes using a range of chromosome pseudomolecule and molecular scaffold assemblies in 2020 has enabled the resistance potential of its genes to be assessed. Findings include the identification of "a detailed multi-genome-derived nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat protein repertoire" which contributes to disease resistance, while the gene Sm1 provides a degree of insect resistance,[202] for instance against the orange wheat blossom midge.[203]

Genomics

[edit]Decoding the genome

[edit]In 2010, 95% of the genome of Chinese Spring line 42 wheat was decoded.[204] This genome was released in a basic format for scientists and plant breeders to use but was not fully annotated.[205] In 2012, an essentially complete gene set of bread wheat was published.[206] Random shotgun libraries of total DNA and cDNA from the T. aestivum cv. Chinese Spring (CS42) were sequenced to generate 85 Gb of sequence (220 million reads) and identified between 94,000 and 96,000 genes.[206] In 2018, a more complete Chinese Spring genome was released by a different team.[207] In 2020, 15 genome sequences from various locations and varieties around the world were reported, with examples of their own use of the sequences to localize particular insect and disease resistance factors.[208] Wheat Blast Resistance is controlled by R genes which are highly race-specific.[154]

Genetic engineering

[edit]For decades, the primary genetic modification technique has been non-homologous end joining. However, since its introduction, the CRISPR/Cas9 tool has been extensively used, for example:[209]

- To intentionally damage three homologs of TaNP1 (a glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase gene) to produce a novel male sterility trait, by Li et al. 2020[209]

- Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici resistance has been produced by Shan et al. 2013 and Wang et al. 2014 by editing one of the mildew resistance locus o genes (more specifically one of the Triticum aestivum MLO (TaMLO) genes)[209]

- T. aestivum EDR1 (TaEDR1) (the EDR1 gene, which inhibits Bmt resistance) has been knocked out by Zhang et al. 2017 to improve that resistance[209]

- T. aestivum HRC (TaHRC) has been disabled by Su et al. 2019 thus producing Gibberella zeae resistance.[209]

- T. aestivum Ms1 (TaMs1) has been knocked out by Okada et al. 2019 to produce another novel male sterility[209]

- and T. aestivum acetolactate synthase (TaALS) and T. aestivum acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (TaACC) were subjected to base changes by Zhang et al. 2019 (in two publications) to confer herbicide resistance to ALS inhibitors and ACCase inhibitors respectively[209]

In art

[edit]

The Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh created the series Wheat Fields between 1885 and 1890, consisting of dozens of paintings made mostly in different parts of rural France. They depict wheat crops, sometimes with farm workers, in varied seasons and styles, sometimes green, sometimes at harvest. Wheatfield with Crows was one of his last paintings, and is considered to be among his greatest works.[210][211]

In 1967, the American artist Thomas Hart Benton made his oil on wood painting Wheat, showing a row of uncut wheat plants, occupying almost the whole height of the painting, between rows of freshly-cut stubble. The painting is held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.[212]

In 1982, the American conceptual artist Agnes Denes grew a two-acre field of wheat at Battery Park, Manhattan. The ephemeral artwork has been described as an act of protest. The harvested wheat was divided and sent to 28 world cities for an exhibition entitled "The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger".[213]

See also

[edit]- Marquis wheat

- Red Fife wheat

- Effects of climate change on agriculture

- Gluten-free diet – Diet excluding proteins found in wheat, barley, and rye

- Wheat germ oil – Oil extracted from the embryo of a wheat seed

- Wheat middlings – By-product of wheat milling

- Wheat production in the United States

- Whole-wheat flour – Basic food ingredient, derived by grinding or mashing the whole grain of wheat

References

[edit]- ^ lectotype designated by Duistermaat, Blumea 32: 174 (1987)

- ^ Serial No. 42236 ITIS 2002-09-22

- ^ "triticum". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Mencken, H. L. (1984). The American language: an inquiry into the development of English in the United States (4th ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 122. ISBN 0-394-40075-5.

Corn, in orthodox English, means grain for human consumption, especially wheat, e.g., the Corn Laws.

- ^ a b "wheat (plant)". britannica.com. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Yang, Hong; Li, Yongpeng; Li, Dongxiao; Liu, Liantao; Qiao, Yunzhou; Sun, Hongyong; et al. (9 June 2022). "Wheat Escapes Low Light Stress by Altering Pollination Types". Frontiers in Plant Science. 13 924565. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.924565. PMC 9218482. PMID 35755640.

- ^ "Fertilising for High Yield and Quality – Cereals" (PDF).

- ^ Pajević, Slobodanka; Krstić, Borivoj; Stanković, Živko; Plesničar, Marijana; Denčić, Srbislav (1999). "Photosynthesis of Flag and Second Wheat Leaves During Senescence". Cereal Research Communications. 27 (1/2): 155–162. doi:10.1007/BF03543932. JSTOR 23786279.

- ^ Araus, J. L.; Tapia, L.; Azcon-Bieto, J.; Caballero, A. (1986). "Photosynthesis, Nitrogen Levels, and Dry Matter Accumulation in Flag Wheat Leaves During Grain Filling". Biological Control of Photosynthesis. pp. 199–207. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-4384-1_18. ISBN 978-94-010-8449-9.

- ^ Singh, Sarvjeet; Sethi, G.S. (1995). "Stomatal Size, Frequency and Distribution in Triticum Aestivum, Secale Cereale and Their Amphiploids". Cereal Research Communications. 23 (1/2): 103–108. JSTOR 23783891.

- ^ Milla, Rubén; De Diego-Vico, Natalia; Martín-Robles, Nieves (2013). "Shifts in stomatal traits following the domestication of plant species". Journal of Experimental Botany. 64 (11): 3137–3146. doi:10.1093/jxb/ert147. PMID 23918960.

- ^ a b "Wheat Growth Guide" (PDF). Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board.

- ^ Das, N. R. (1 October 2008). Wheat Crop Management. Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-93-87741-28-7.

- ^ Hogan, M. E.; Hendrix, J. E. (1986). "Labeling of Fructans in Winter Wheat Stems". Plant Physiology. 80 (4): 1048–1050. doi:10.1104/pp.80.4.1048. PMC 1075255. PMID 16664718.

- ^ Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Dell, B.; Vergauwen, R.; Zhang, X.; Mayer, J. E.; Van Den Ende, W. (2015). "Wheat genotypic variation in dynamic fluxes of WSC components in different stem segments under drought during grain filling". Frontiers in Plant Science. 6: 624. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00624. PMC 4531436. PMID 26322065.

- ^ Lopes, Marta S.; Reynolds, Matthew P. (2010). "Partitioning of assimilates to deeper roots is associated with cooler canopies and increased yield under drought in wheat". Functional Plant Biology. 37 (2): 147. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.6514. doi:10.1071/FP09121.

- ^ Rebetzke, G. J.; Bonnett, D. G.; Reynolds, M. P. (2016). "Awns reduce grain number to increase grain size and harvestable yield in irrigated and rainfed spring wheat". Journal of Experimental Botany. 67 (9): 2573–2586. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw081. PMC 4861010. PMID 26976817.

- ^ Duwayri, Mahmud (1984). "Effect of flag leaf and awn removal on grain yield and yield components of wheat grown under dryland conditions". Field Crops Research. 8: 307–313. Bibcode:1984FCrRe...8..307D. doi:10.1016/0378-4290(84)90077-7.

- ^ Kahiluoto, Helena; Kaseva, Janne; Balek, Jan; Olesen, Jørgen E.; Ruiz-Ramos, Margarita; et al. (2019). "Decline in climate resilience of European wheat". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (1): 123–128. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116..123K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1804387115. PMC 6320549. PMID 30584094.

- ^ Richter, Tobias; Maher, Lisa A. (2013). "Terminology, process and change: reflections on the Epipalaeolithic of South-west Asia". Levant. 45 (2): 121–132. doi:10.1179/0075891413Z.00000000020. S2CID 161961145.

- ^ Piperno, Dolores R.; Weiss, Ehud; Holst, Irene; Nadel, Dani (August 2004). "Processing of wild cereal grains in the Upper Palaeolithic revealed by starch grain analysis". Nature. 430 (7000): 670–673. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..670P. doi:10.1038/nature02734. PMID 15295598. S2CID 4431395.

- ^ Arranz-Otaegui, Amaia; González Carretero, Lara; Roe, Joe; Richter, Tobias (2018). ""Founder crops" v. wild plants: Assessing the plant-based diet of the last hunter-gatherers in southwest Asia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 186: 263–283. Bibcode:2018QSRv..186..263A. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.02.011.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Willcox, George; Allaby, Robin G. (2011). "Cultivation and domestication had multiple origins: arguments against the core area hypothesis for the origins of agriculture in the Near East". World Archaeology. 43 (4): 628–652. doi:10.1080/00438243.2011.624747. S2CID 56437102.

- ^ Hughes, N.; Oliveira, H.R.; Fradgley, N.; Corke, F.; Cockram, J.; Doonan, J.H.; Nibau, C. (14 March 2019). "μCT trait analysis reveals morphometric differences between domesticated temperate small grain cereals and their wild relatives". The Plant Journal. 99 (1): 98–111. doi:10.1111/tpj.14312. PMC 6618119. PMID 30868647.

- ^ Tanno, K.; Willcox, G. (2006). "How fast was wild wheat domesticated?". Science. 311 (5769): 1886. doi:10.1126/science.1124635. PMID 16574859. S2CID 5738581.

- ^ Purugganan, Michael D.; Fuller, Dorian Q. (1 February 2009). "The nature of selection during plant domestication". Nature. 457 (7231). Springer: 843–848. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..843P. doi:10.1038/nature07895. PMID 19212403. S2CID 205216444.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zohary, Daniel; Hopf, Maria; Weiss, Ehud (2012). "Cereals". Domestication of Plants in the Old World (4 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199549061.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-954906-1.

- ^ a b c Ozkan, H.; Brandolini, A.; Schäfer-Pregl, R.; Salamini, F. (2002). "AFLP analysis of a collection of tetraploid wheats indicates the origin of emmer and hard wheat domestication in southeast Turkey". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (10): 1797–1801. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004002. PMID 12270906.

- ^ Feldman, Moshe; Kislev, Mordechai E. (2007). "Domestication of emmer wheat and evolution of free-threshing tetraploid wheat in "A Century of Wheat Research-From Wild Emmer Discovery to Genome Analysis", Published Online: 3 November 2008". Israel Journal of Plant Sciences. 55 (3–4): 207–221. doi:10.1560/IJPS.55.3-4.207 (inactive 12 July 2025). Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Colledge, Sue (2007). The origins and spread of domestic plants in southwest Asia and Europe. Left Coast Press. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-59874-988-5.

- ^ Luo, M.-C.; Yang, Z.-L.; You, F. M.; Kawahara, T.; Waines, J. G.; Dvorak, J. (2007). "The structure of wild and domesticated emmer wheat populations, gene flow between them, and the site of emmer domestication". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 114 (6): 947–959. doi:10.1007/s00122-006-0474-0. PMID 17318496. S2CID 36096777.

- ^ Czajkowska, Beata I.; Bogaard, Amy; Charles, Michael; Jones, Glynis; Kohler-Schneider, Marianne; Mueller-Bieniek, Aldona; Brown, Terence A. (1 November 2020). "Ancient DNA typing indicates that the "new" glume wheat of early Eurasian agriculture is a cultivated member of the Triticum timopheevii group". Journal of Archaeological Science. 123 105258. Bibcode:2020JArSc.123j5258C. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105258. S2CID 225168770.

- ^ a b Arranz-Otaegui, Amaia; Roe, Joe (1 September 2023). "Revisiting the concept of the 'Neolithic Founder Crops' in southwest Asia". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 32 (5): 475–499. Bibcode:2023VegHA..32..475A. doi:10.1007/s00334-023-00917-1. hdl:10810/67728. S2CID 258044557.

- ^ Weide, Alexander; Green, Laura; Hodgson, John G.; Douché, Carolyne; Tengberg, Margareta; Whitlam, Jade; Dovrat, Guy; Osem, Yagil; Bogaard, Amy (June 2022). "A new functional ecological model reveals the nature of early plant management in southwest Asia". Nature Plants. 8 (6): 623–634. Bibcode:2022NatPl...8..623W. doi:10.1038/s41477-022-01161-7. PMID 35654954. S2CID 249313666.

- ^ Sherratt, Andrew (February 1980). "Water, soil and seasonality in early cereal cultivation". World Archaeology. 11 (3): 313–330. doi:10.1080/00438243.1980.9979770.

- ^ Scott, James C. (2017). "The Domestication of Fire, Plants, Animals, and ... Us". Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-3002-3168-7. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

The general problem with farming — especially plough agriculture — is that it involves so much intensive labor. One form of agriculture, however, eliminates most of this labor: 'flood-retreat' (also known as décrue or recession) agriculture. In flood-retreat agriculture, seeds are generally broadcast on the fertile silt deposited by an annual riverine flood.

- ^ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (2021). The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. London: Allen Lane. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-241-40242-9.

- ^ Maeda, Osamu; Lucas, Leilani; Silva, Fabio; Tanno, Ken-Ichi; Fuller, Dorian Q. (1 August 2016). "Narrowing the Harvest: Increasing sickle investment and the rise of domesticated cereal agriculture in the Fertile Crescent". Quaternary Science Reviews. 145: 226–237. Bibcode:2016QSRv..145..226M. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.05.032. hdl:2241/00143830.

- ^ a b Weide, Alexander (29 November 2021). "Towards a Socio-Economic Model for Southwest Asian Cereal Domestication". Agronomy. 11 (12): 2432. Bibcode:2021Agron..11.2432W. doi:10.3390/agronomy11122432.

- ^ Dubreuil, Laure (1 November 2004). "Long-term trends in Natufian subsistence: a use-wear analysis of ground stone tools". Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (11): 1613–1629. Bibcode:2004JArSc..31.1613D. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.04.003.

- ^ Arranz-Otaegui, Amaia; Gonzalez Carretero, Lara; Ramsey, Monica N.; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Richter, Tobias (31 July 2018). "Archaeobotanical evidence reveals the origins of bread 14,400 years ago in northeastern Jordan". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (31): 7925–7930. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.7925A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1801071115. PMC 6077754. PMID 30012614.

- ^ González Carretero, Lara; Wollstonecroft, Michèle; Fuller, Dorian Q. (1 July 2017). "A methodological approach to the study of archaeological cereal meals: a case study at Çatalhöyük East (Turkey)". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 26 (4): 415–432. Bibcode:2017VegHA..26..415G. doi:10.1007/s00334-017-0602-6. PMC 5486841. PMID 28706348. S2CID 41734442.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Carretero, Lara Gonzalez (5 December 2018). "The Archaeology of Neolithic Cooking Traditions: Archaeobotanical Approaches to Baking, Boiling and Fermenting". Archaeology International. 21: 109–121. doi:10.5334/ai-391.

- ^ Graeber, David; Wengrow, David (2021). The dawn of everything: a new history of humanity. London: Allen Lane. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-241-40242-9.

- ^ Vigne, Jean-Denis; Briois, François; Zazzo, Antoine; Willcox, George; Cucchi, Thomas; Thiébault, Stéphanie; Carrère, Isabelle; Franel, Yodrik; Touquet, Régis; Martin, Chloé; Moreau, Christophe; Comby, Clothilde; Guilaine, Jean (29 May 2012). "First wave of cultivators spread to Cyprus at least 10,600 y ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (22): 8445–8449. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8445V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201693109. PMC 3365171. PMID 22566638.

- ^ Lucas, Leilani; Colledge, Sue; Simmons, Alan; Fuller, Dorian Q. (1 March 2012). "Crop introduction and accelerated island evolution: archaeobotanical evidence from 'Ais Yiorkis and Pre-Pottery Neolithic Cyprus". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 21 (2): 117–129. Bibcode:2012VegHA..21..117L. doi:10.1007/s00334-011-0323-1. S2CID 129727157.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2005) [1997]. Guns, Germs and Steel. Vintage. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-099-30278-0.

- ^ Grundas, S.T. (2003). "Wheat: The Crop". Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. Elsevier Science. p. 6130. ISBN 978-0-12-227055-0.

- ^ Piotrowski, Jan (26 February 2019). "Britons may have imported wheat long before farming it". New Scientist. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Smith, Oliver; Momber, Garry; Bates, Richard; et al. (2015). "Sedimentary DNA from a submerged site reveals wheat in the British Isles 8000 years ago". Science. 347 (6225): 998–1001. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..998S. doi:10.1126/science.1261278. hdl:10454/9405. PMID 25722413. S2CID 1167101.

- ^ Brace, Selina; Diekmann, Yoan; Booth, Thomas J.; van Dorp, Lucy; Faltyskova, Zuzana; et al. (2019). "Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (5): 765–771. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3..765B. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9. PMC 6520225. PMID 30988490.

Neolithic cultures first appear in Britain circa 4000 bc, a millennium after they appeared in adjacent areas of continental Europe.

- ^ Jarrige, Jean-François; Meadow, Richard H (1980). "The antecedents of civilization in the Indus Valley". Scientific American. 243 (2): 122–137.

- ^ Long, Tengwen; Leipe, Christian; Jin, Guiyun; Wagner, Mayke; Guo, Rongzhen; et al. (2018). "The early history of wheat in China from 14C dating and Bayesian chronological modelling". Nature Plants. 4 (5): 272–279. doi:10.1038/s41477-018-0141-x. PMID 29725102. S2CID 19156382.

- ^ Bilgic, Hatice; et al. (2016). "Ancient DNA from 8400 Year-Old Çatalhöyük Wheat: Implications for the Origin of Neolithic Agriculture". PLOS One. 11 (3) e0151974. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1151974B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151974. PMC 4801371. PMID 26998604.

- ^ "The science in detail – Wheats DNA – Research – Archaeology". The University of Sheffield. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Belderok, B.; et al. (2000). Bread-Making Quality of Wheat. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 0-7923-6383-3.

- ^ Cauvain, S.P.; Cauvain, P. (2003). Bread Making. CRC Press. p. 540. ISBN 1-85573-553-9.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. University of Chicago Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Nelson, Scott Reynolds (2022). Oceans of Grain: How American Wheat Remade the World. Basic Books. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-5416-4646-9.

- ^ a b c d Golovnina, K. A.; Glushkov, S. A.; Blinov, A. G.; Mayorov, V. I.; Adkison, L. R.; Goncharov, N. P. (12 February 2007). "Molecular phylogeny of the genus Triticum L". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 264 (3–4). Springer: 195–216. Bibcode:2007PSyEv.264..195G. doi:10.1007/s00606-006-0478-x. S2CID 39102602.

- ^ a b Belderok, Robert 'Bob'; Mesdag, Hans; Donner, Dingena A. (2000). Bread-Making Quality of Wheat. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7923-6383-5.

- ^ Friebe, B.; Qi, L.L.; Nasuda, S.; Zhang, P.; Tuleen, N.A.; Gill, B.S. (July 2000). "Development of a complete set of Triticum aestivum-Aegilops speltoides chromosome addition lines". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 101 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1007/s001220051448. S2CID 13010134.

- ^ Dvorak, Jan; Deal, Karin R.; Luo, Ming-Cheng; You, Frank M.; von Borstel, Keith; Dehghani, Hamid (1 May 2012). "The Origin of Spelt and Free-Threshing Hexaploid Wheat". Journal of Heredity. 103 (3): 426–441. doi:10.1093/jhered/esr152. PMID 22378960.

- ^ Shewry, P. R. (1 April 2009). "Wheat". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (6): 1537–1553. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp058. ISSN 0022-0957. PMID 19386614.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Lucas, Leilani (2014), "Wheats: Origins and Development", Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, Springer New York, pp. 7812–7817, doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_2192, ISBN 978-1-4419-0426-3, S2CID 129138746

- ^ a b Potts, D.T. (1996). Mesopotamia Civilization: The Material Foundations. Cornell University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-8014-3339-8.

- ^ Nevo, E. (29 January 2002). Evolution of Wild Emmer and Wheat Improvement. Berlin ; New York: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 8. ISBN 3-540-41750-8.

- ^ Vaughan, J.G.; Judd, P.A. (2003). The Oxford Book of Health Foods. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-19-850459-4.

- ^ "Field Crop Information". College of Agriculture and Bioresources, University of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 18 October 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b Yang, Fan; Zhang, Jingjuan; Liu, Qier; et al. (17 February 2022). "Improvement and Re-Evolution of Tetraploid Wheat for Global Environmental Challenge and Diversity Consumption Demand". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (4): 2206. doi:10.3390/ijms23042206. PMC 8878472. PMID 35216323.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (15 May 2014). "Spelt flour 'wonder grain' set for a price hike as supplies run low". The Guardian.

- ^ "Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccon". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Khlestkina, Elena K.; Röder, Marion S.; Grausgruber, Heinrich; Börner, Andreas (2006). "A DNA fingerprinting-based taxonomic allocation of Kamut wheat". Plant Genetic Resources. 4 (3): 172–180. doi:10.1079/PGR2006120. S2CID 86510231.

- ^ Anderson, Patricia C. (1991). "Harvesting of Wild Cereals During the Natufian as seen from Experimental Cultivation and Harvest of Wild Einkorn Wheat and Microwear Analysis of Stone Tools". In Bar-Yosef, Ofer (ed.). Natufian Culture in the Levant. International Monographs in Prehistory. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Berghahn Books. p. 523.

- ^ Khan 2016, pp. 109–116.

- ^ Khan 2016, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Khan 2016, p. 110.

- ^ Khan 2016, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Bridgwater, W.; Aldrich, Beatrice (1966). "Wheat". The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. p. 1959.

- ^ "Flour types: Wheat, Rye, and Barley". The New York Times. 18 February 1981.

- ^ "Wheat: Background". USDA. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "TABLE 4-7 Comparison of Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in This Report to Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in the 2005 DRI Report". p. 120. In: Stallings, Virginia A.; Harrison, Meghan; Oria, Maria, eds. (2019). "Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. pp. 101–124. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. NCBI NBK545428.

- ^ Mauseth, James D. (2014). Botany. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-4496-4884-8.

Perhaps the simplest of fruits are those of grasses (all cereals such as corn and wheat)...These fruits are caryopses.

- ^ Ensminger, Marion; Ensminger, Audrey H. Eugene (1993). Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia, Two Volume Set. CRC Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8493-8980-1.

- ^ "Wheat". Food Allergy Canada. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Shewry, P. R.; Halford, N. G.; Belton, P. S.; Tatham, A. S. (2002). "The structure and properties of gluten: An elastic protein from wheat grain". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 357 (1418): 133–42. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.1024. PMC 1692935. PMID 11911770.

- ^ a b "Whole Grain Fact Sheet". European Food Information Council. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shewry, Peter R.; Hey, S. J. (2015). "Review: The contribution of wheat to human diet and health". Food and Energy Security. 4 (3): 178–202. doi:10.1002/fes3.64. PMC 4998136. PMID 27610232.

- ^ European Community, Community Research and Development Information Service (24 February 2016). "Genetic markers signal increased crop productivity potential". Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2013. ISBN 978-92-5-107417-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Wolfe, R. R. (August 2015). "Update on protein intake: importance of milk proteins for health status of the elderly". Nutrition Reviews (Review). 73 (Suppl 1): 41–47. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv021. PMC 4597363. PMID 26175489.

- ^ Shewry, Peter R. "Impacts of agriculture on human health and nutrition – Vol. II – Improving the Protein Content and Quality of Temperate Cereals: Wheat, Barley and Rye" (PDF). UNESCO – Encyclopedia Life Support Systems (UNESCO-EOLSS). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

When compared with the WHO requirements of essential amino acids for humans, wheat, barley and rye are seen to be deficient in lysine, with threonine being the second limiting amino acid (Table 1).

- ^ Vasal, S. K. "The role of high lysine cereals in animal and human nutrition in Asia". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "Nutritional quality of cereals". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Shewry, Peter R. (2009). "Wheat". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (6): 1537–53. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp058. PMID 19386614.

- ^ "Whole Grain Resource for the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs: A Guide to Meeting the Whole Grain-Rich criteria" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2022.

Additionally, menu planners are encouraged to serve a variety of foods that meet whole grain-rich criteria and may not serve the same product every day to count for the HUSSC whole grain-rich criteria.

- ^ "All About the Grains Group". US Department of Agriculture, MyPlate. 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Celiac disease". World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. July 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ a b c "Definition and Facts for Celiac Disease". The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ a b Ludvigsson, Jonas F.; Leffler, Daniel A.; Bai, Julio C.; Biagi, Federico; Fasano, Alessio; et al. (16 February 2012). "The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms". Gut. 62 (1). BMJ: 43–52. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. PMC 3440559. PMID 22345659.

- ^ Molina-Infante, J.; Santolaria, S.; Sanders, D. S.; Fernández-Bañares, F. (May 2015). "Systematic review: noncoeliac gluten sensitivity". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 41 (9): 807–820. doi:10.1111/apt.13155. PMID 25753138. S2CID 207050854.

- ^ Volta, Umberto; De Giorgio, Roberto; Caio, Giacomo; Uhde, Melanie; Manfredini, Roberto; Alaedini, Armin (2019). "Nonceliac Wheat Sensitivity". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 48 (1): 165–182. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2018.09.012. PMC 6364564. PMID 30711208.

- ^ a b c Verbeke, K. (February 2018). "Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: What Is the Culprit?". Gastroenterology. 154 (3): 471–473. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.013. PMID 29337156.

- ^ a b Fasano, Alessio; Sapone, Anna; Zevallos, Victor; Schuppan, Detlef (2015). "Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity". Gastroenterology. 148 (6): 1195–1204. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049. PMID 25583468.

- ^ Barone, Maria; Troncone, Riccardo; Auricchio, Salvatore (2014). "Gliadin Peptides as Triggers of the Proliferative and Stress/Innate Immune Response of the Celiac Small Intestinal Mucosa". International Journal of Molecular Sciences (Review). 15 (11): 20518–20537. doi:10.3390/ijms151120518. PMC 4264181. PMID 25387079.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021. Rome: FAO. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb4477en. ISBN 978-92-5-134332-6. S2CID 240163091.

- ^ "Wheat production in 2023 from pick lists: Crops/World regions/Production quantity/Year". www.fao.org. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- ^ "Crops and livestock products". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division, FAOSTAT. 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Wheat area harvested, world total from pick lists: Crops/World regions/Area harvested/Year". 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ Curtis; Rajaraman; MacPherson (2002). "Bread Wheat". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- ^ Day, L.; Augustin, M.A.; Batey, I.L.; Wrigley, C.W. (2006). "Wheat-gluten uses and industry needs". Trends in Food Science & Technology (Review). 17 (2). Elsevier: 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2005.10.003.

- ^ "Wheat prices in England". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Palmer, Alan (1996). Dictionary of the British Empire and Commonwealth. pp. 193, 320, 338.

- ^ Ridley, Annie E. (1904). A Backward Glance: The Story of John Ridley, a Pioneer. J. Clarke. p. 21.

- ^ Furtan, W. Hartley; Lee, George E. (1977). "Economic Development of the Saskatchewan Wheat Economy". Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics. 25 (3): 15–28. Bibcode:1977CaJAE..25...15F. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7976.1977.tb02882.x.

- ^ Joshi, A. K.; Mishra, B.; Chatrath, R.; Ortiz Ferrara, G.; Singh, Ravi P. (2007). "Wheat improvement in India: present status, emerging challenges and future prospects". Euphytica. 157 (3): 431–446. doi:10.1007/s10681-007-9385-7. S2CID 38596433.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Slafer, G.A.; Satorre, E.H. (1999). "Chapter 1". Wheat: Ecology and Physiology of Yield Determination. Haworth Press. ISBN 1-56022-874-1.

- ^ Wright, B. D.; Pardey, P. G. (2002). "Agricultural R&D, productivity, and global food prospects". Plants, Genes and Crop Biotechnology. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 22–51. ISBN 978-0-7637-1586-1.

- ^ Asseng, S.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; Rötter, R. P.; Lobell, D. B.; et al. (2015). "Rising temperatures reduce global wheat production" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 5 (2): 143–147. Bibcode:2015NatCC...5..143A. doi:10.1038/nclimate2470. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Braun, Karen (23 April 2025). "Ukraine's once-booming grain industry teetering on being a war casualty". Reuters. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ "Finding the Flow: How Does Wheat Navigate Trade's Changing Reality?". New US Wheat. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ "Investing In Agriculture - Food, Feed & Fuel", Feb 29th 2008 at

- ^ "Could we really run out of food?", Jon Markman, March 6, 2008 at http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/SuperModels/CouldWeReallyRunOutOfFood.aspx Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McKillop, Andrew (13 December 2006). "Peak Natural Gas is On the Way - Raise the Hammer". www.raisethehammer.org. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Globe Investor at http://www.globeinvestor.com/servlet/WireFeedRedirect?cf=GlobeInvestor/config&date=20080408&archive=nlk&slug=00011064, 2008

- ^ Credit Suisse First Boston, Higher Agricultural Prices: Opportunities and Risks, November 2007

- ^ Food Production May Have to Double by 2030 - Western Spectator "Food Prices Could Increase 10 Times by 2050 | WS". 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Agriculture and Food — Agricultural Production Indices: Food production per capita index Archived 2009-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, World Resources Institute

- ^ a b "How To Grow Wheat Efficiently On A Large Farm". EOS Data Analytics. 10 May 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Slafer, G.A.; Satorre, E.H. (1999). Wheat: Ecology and Physiology of Yield Determination. Haworth Press. pp. 322–323. ISBN 1-56022-874-1.

- ^ Saini, H.S.; Sedgley, M.; Aspinall, D. (1984). "Effect of heat stress during floral development on pollen tube growth and ovary anatomy in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.)". Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 10 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1071/PP9830137.

- ^ Overton, Mark (1996). Agricultural Revolution in England: The transformation of the agrarian economy 1500-1850. Cambridge University Press. p. 1, and throughout. ISBN 978-0-521-56859-3.

- ^ Caprettini, Bruno; Voth, Hans-Joachim (2020). "Rage against the Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing England". American Economic Review: Insights. 2 (3): 305–320. doi:10.1257/aeri.20190385. S2CID 234622559.

- ^ Constable, George; Somerville, Bob (2003). A Century of Innovation: Twenty Engineering Achievements That Transformed Our Lives, Chapter 7, Agricultural Mechanization. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-08908-5.

- ^ Borojevic, Katarina; Borojevic, Ksenija (July–August 2005). "The Transfer and History of "Reduced Height Genes" (Rht) in Wheat from Japan to Europe". Journal of Heredity. 96 (4). Oxford University Press: 455–459. doi:10.1093/jhered/esi060. PMID 15829727.

- ^ Shindler, Miriam (3 January 2016). "From east Asia to south Asia, via Mexico: how one gene changed the course of history". CIMMYT. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Brown, L. R. (30 October 1970). "Nobel Peace Prize: developer of high-yield wheat receives award (Norman Ernest Borlaug)". Science. 170 (957): 518–519. doi:10.1126/science.170.3957.518. PMID 4918766.

- ^ Basavaraja, H.; Mahajanashetti, S.B.; Udagatti, N.C. (2007). "Economic Analysis of Post-harvest Losses in Food Grains in India: A Case Study of Karnataka" (PDF). Agricultural Economics Research Review. 20: 117–126. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Godfray, H.C.; Beddington, J. R.; Crute, I. R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; et al. (2010). "Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people". Science. 327 (5967): 812–818. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..812G. doi:10.1126/science.1185383. PMID 20110467.

- ^ Swaminathan, M. S. (2004). "Stocktake on cropping and crop science for a diverse planet". Proceedings of the 4th International Crop Science Congress, Brisbane, Australia. Archived from the original on 18 June 2005.

- ^ "Umbers, Alan (2006, Grains Council of Australia Limited) Grains Industry trends in Production – Results from Today's Farming Practices" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2017.

- ^ Savary, Serge; Willocquet, Laetitia; Pethybridge, Sarah Jane; Esker, Paul; McRoberts, Neil; Nelson, Andy (4 February 2019). "The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 430–439. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3..430S. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0793-y. PMID 30718852. S2CID 59603871.

- ^ Abhishek, Aditya (11 January 2021). "Disease of Wheat: Get To Know Everything About Wheat Diseases". Agriculture Review. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "G4319 Wheat Diseases in Missouri, MU Extension". University of Missouri Extension. Archived from the original on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2013). "Wheat". In Saundry, P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington DC: National Council for Science and the Environment.

- ^ Fabre, Frederic; Burie, Jean-Baptiste; Ducrot, Arnaud; Lion, Sebastien; Richard, Quentin; Demasse, Ramses (2022). "An epi-evolutionary model for predicting the adaptation of spore-producing pathogens to quantitative resistance in heterogeneous environments". Evolutionary Applications. 15 (1). John Wiley & Sons: 95–110. Bibcode:2022EvApp..15...95F. doi:10.1111/eva.13328. PMC 8792485. PMID 35126650.

- ^ a b c d Singh, Jagdeep; Chhabra, Bhavit; Raza, Ali; Yang, Seung Hwan; Sandhu, Karansher S. (2023). "Important wheat diseases in the US and their management in the 21st century". Frontiers in Plant Science. 13. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1010191. PMC 9877539. PMID 36714765.

- ^ Gautam, P.; Dill-Macky, R. (2012). "Impact of moisture, host genetics and Fusarium graminearum isolates on Fusarium head blight development and trichothecene accumulation in spring wheat". Mycotoxin Research. 28 (1): 45–58. doi:10.1007/s12550-011-0115-6. PMID 23605982. S2CID 16596348.