Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

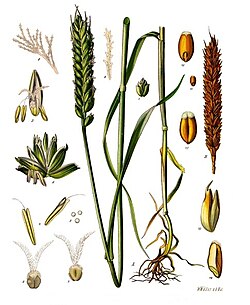

Cereal

View on Wikipedia

(middle) sorghum, maize, oats

(bottom) millet, wheat, rye, triticale

A cereal is a grass cultivated for its edible grain. Cereals are the world's largest crops, and are therefore staple foods. They include rice, wheat, rye, oats, barley, millet, and maize (corn). Edible grains from other plant families, such as amaranth, buckwheat and quinoa, are pseudocereals. Most cereals are annuals, producing one crop from each planting, though rice is sometimes grown as a perennial. Winter varieties are hardy enough to be planted in the autumn, becoming dormant in the winter, and harvested in spring or early summer; spring varieties are planted in spring and harvested in late summer. The term cereal is derived from the name of the Roman goddess of grain crops and fertility, Ceres.

Cereals were domesticated in the Neolithic around 8,000 years ago. Wheat and barley were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent. Rice and some millets were domesticated in East Asia, while sorghum and other millets were domesticated in West Africa. Maize was domesticated by Indigenous peoples of the Americas in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago. In the 20th century, cereal productivity was greatly increased by the Green Revolution. This increase in production has accompanied a growing international trade, with some countries producing large portions of the cereal supply for other countries.

Cereals provide food eaten directly as whole grains, usually cooked, or they are ground to flour and made into bread, porridge, and other products. Cereals have a high starch content, enabling them to be fermented into alcoholic drinks such as beer. Cereal farming has a substantial environmental impact, and is often produced in high-intensity monocultures. The environmental harms can be mitigated by sustainable practices which reduce the impact on soil and improve biodiversity, such as no-till farming and intercropping.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

Wheat, barley, rye, and oats were gathered and eaten in the Fertile Crescent during the early Neolithic. Cereal grains 19,000 years old have been found at the Ohalo II site in Israel, with charred remnants of wild wheat and barley.[1]

During the same period, farmers in China began to farm rice and millet, using human-made floods and fires as part of their cultivation regimen.[2][3] The use of soil conditioners, including manure, fish, compost and ashes, appears to have begun early, and developed independently in areas of the world including Mesopotamia, the Nile Valley, and Eastern Asia.[4]

Cereals that became modern barley and wheat were domesticated some 8,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent.[5] Millets and rice were domesticated in East Asia, while sorghum and other millets were domesticated in sub-Saharan West Africa, primarily as feed for livestock.[6] Maize arose from a single domestication in Mesoamerica about 9,000 years ago.[7]

In these agricultural regions, religion was often shaped by the divinity associated with the grain and harvests. In the Mesopotamian creation myth, an era of civilization is inaugurated by the grain goddess Ashnan.[8] The Roman goddess Ceres presided over agriculture, grain crops, fertility, and motherhood;[9] the term cereal is derived from Latin cerealis, "of grain", originally meaning "of [the goddess] Ceres".[10] Several gods of antiquity combined agriculture and war: the Hittite Sun goddess of Arinna, the Canaanite Lahmu and the Roman Janus.[11]

Complex civilizations arose where cereal agriculture created a surplus, allowing for part of the harvest to be appropriated from farmers, allowing power to be concentrated in cities.[12]

Modern

[edit]

During the second half of the 20th century, there was a significant increase in the production of high-yield cereal crops worldwide, especially wheat and rice, due to the Green Revolution, a technological change funded by development organizations.[15] The strategies developed by the Green Revolution included mechanized tilling, monoculture, nitrogen fertilizers, and breeding of new strains of seeds. These innovations focused on fending off starvation and increasing yield-per-plant, and were very successful in raising overall yields of cereal grains, but paid less attention to nutritional quality.[16] These modern high-yield cereal crops tend to have low-quality proteins, with essential amino acid deficiencies, are high in carbohydrates, and lack balanced essential fatty acids, vitamins, minerals and other quality factors.[16] So-called ancient grains and heirloom varieties have seen an increase in popularity with the "organic" movements of the early 21st century, but there is a tradeoff in yield-per-plant, putting pressure on resource-poor areas as food crops are replaced with cash crops.[17]

Biology

[edit]

Cereals are grasses, in the Poaceae family, that produce edible grains. A cereal grain is botanically a caryopsis, a fruit where the seed coat is fused with the pericarp.[18][19] Grasses have stems that are hollow except at the nodes and narrow alternate leaves borne in two ranks.[20] The lower part of each leaf encloses the stem, forming a leaf-sheath. The leaf grows from the base of the blade, an adaptation that protects the growing meristem from grazing animals.[20][21] The flowers are usually hermaphroditic, with the exception of maize, and mainly anemophilous or wind-pollinated, although insects occasionally play a role.[20][22]

Among the best-known cereals are maize, rice, wheat, barley, sorghum, millet, oat, rye and triticale.[23] Some other grains are colloquially called cereals, even though they are not grasses; these pseudocereals include buckwheat, quinoa, and amaranth.[24]

Cultivation

[edit]All cereal crops are cultivated in a similar way. Most are annual, so after sowing they are harvested just once.[25] An exception is rice, which although usually treated as an annual can survive as a perennial, producing a ratoon crop.[26] Cereals adapted to a temperate climate, such as barley, oats, rye, spelt, triticale, and wheat, are called cool-season cereals. Those preferring a tropical climate, such as millet and sorghum, are called warm-season cereals.[25][27][28] Cool-season cereals, especially rye, followed by barley, are hardy; they grow best in fairly cool weather, and stop growing, depending on variety, when the temperature goes above around 30 °C or 85 °F. Warm-season cereals, in contrast, require hot weather and cannot tolerate frost.[25] Cool-season cereals can be grown in highlands in the tropics, where they sometimes deliver several crops in a single year.[25]

Planting

[edit]

In the tropics, warm-season cereals can be grown at any time of the year. In temperate zones, these cereals can only be grown when there is no frost. Most cereals are planted in tilled soils, which reduces weeds and breaks up the surface of a field. Most cereals need regular water in the early part of their life cycle. Rice is commonly grown in flooded fields,[29] though some strains are grown on dry land.[30] Other warm climate cereals, such as sorghum, are adapted to arid conditions.[31]

Cool-season cereals are grown mainly in temperate zones. These cereals often have both winter varieties for autumn sowing, winter dormancy, and early summer harvesting, and spring varieties planted in spring and harvested in late summer. Winter varieties have the advantage of using water when it is plentiful, and permitting a second crop after the early harvest. They flower only in spring as they require vernalization, exposure to cold for a specific period, fixed genetically. Spring crops grow when it is warmer but less rainy, so they may need irrigation.[25]

Growth

[edit]

Cereal strains are bred for consistency and resilience to the local environmental conditions. The greatest constraints on yield are plant diseases, especially rusts (mostly the Puccinia spp.) and powdery mildews.[32] Fusarium head blight, caused by Fusarium graminearum, is a significant limitation on a wide variety of cereals.[33] Other pressures include pest insects and wildlife like rodents and deer.[34][35] In conventional agriculture, some farmers apply fungicides or pesticides.

Harvesting

[edit]Annual cereals die when they have come to seed, and dry up. Harvesting begins once the plants and seeds are dry enough. Harvesting in mechanized agricultural systems is by combine harvester, a machine which drives across the field in a single pass in which it cuts the stalks and then threshes and winnows the grain.[25][36] In traditional agricultural systems, mostly in the Global South, harvesting may be by hand, using tools such as scythes and grain cradles.[25] Leftover parts of the plant can be allowed to decompose, or collected as straw; this can be used for animal bedding, mulch, and a growing medium for mushrooms.[37] It is used in crafts such as building with cob or straw-bale construction.[38]

-

A small-scale rice combine harvester in Japan

Preprocessing and storage

[edit]If cereals are not completely dry when harvested, such as when the weather is rainy, the stored grain will be spoilt by mould fungi such as Aspergillus and Penicillium.[25][39] This can be prevented by drying it artificially. It may then be stored in a grain elevator or silo, to be sold later. Grain stores need to be constructed to protect the grain from damage by pests such as seed-eating birds and rodents.[25]

-

Grain elevators on a farm in Israel

Processing

[edit]

When the cereal is ready to be distributed, it is sold to a manufacturing facility that first removes the outer layers of the grain for subsequent milling for flour or other processing steps, to produce foods such as flour, oatmeal, or pearl barley.[40] In developing countries, processing may be traditional, in artisanal workshops, as with tortilla production in Central America.[41]

Most cereals can be processed in a variety of ways. Rice processing, for instance, can create whole-grain or polished rice, or rice flour. Removal of the germ increases the longevity of grain in storage.[42] Some grains can be malted, a process of activating enzymes in the seed to cause sprouting that turns the complex starches into sugars before drying.[43][44] These sugars can be extracted for industrial uses and further processing, such as for making industrial alcohol,[45] beer,[46] whisky,[47] or rice wine,[48] or sold directly as a sugar.[49] In the 20th century, industrial processes developed around chemically altering the grain, to be used for other processes. In particular, maize can be altered to produce food additives, such as corn starch[50] and high-fructose corn syrup.[51]

Effects on the environment

[edit]Impacts

[edit]

Cereal production has a substantial impact on the environment. Tillage can lead to soil erosion and increased runoff.[52] Irrigation consumes large quantities of water; its extraction from lakes, rivers, or aquifers may have multiple environmental effects, such as lowering the water table and cause salination of aquifers.[53] Fertilizer production contributes to global warming,[54] and its use can lead to pollution and eutrophication of waterways.[55] Arable farming uses large amounts of fossil fuel, releasing greenhouse gases which contribute to global warming.[56] Pesticide usage can cause harm to wildlife, such as to bees.[57]

Mitigations

[edit]

Some of the impacts of growing cereals can be mitigated by changing production practices. Tillage can be reduced by no-till farming, such as by direct drilling of cereal seeds, or by developing and planting perennial crop varieties so that annual tilling is not required. Rice can be grown as a ratoon crop;[26] and other researchers are exploring perennial cool-season cereals, such as kernza, being developed in the US.[58]

Fertilizer and pesticide usage may be reduced in some polycultures, growing several crops in a single field at the same time.[59] Fossil fuel-based nitrogen fertilizer usage can be reduced by intercropping cereals with legumes which fix nitrogen.[60] Greenhouse gas emissions may be cut further by more efficient irrigation or by water harvesting methods like contour trenching that reduce the need for irrigation, and by breeding new crop varieties.[61]

Uses

[edit]Direct consumption

[edit]Some cereals such as rice require little preparation before human consumption. For example, to make plain cooked rice, raw milled rice is washed and boiled.[62] Foods such as porridge[63] and muesli may be made largely of whole cereals, especially oats, whereas commercial breakfast cereals such as granola may be highly processed and combined with sugars, oils, and other products.[64]

Flour-based foods

[edit]

Cereals can be ground to make flour. Wheat flour is the main ingredient of bread and pasta.[65][66][67] Maize flour has been important in Mesoamerica since ancient times, with foods such as Mexican tortillas and tamales.[68] Rye flour is a constituent of bread in central and northern Europe,[69] while rice flour is common in Asia.[70]

A cereal grain consists of starchy endosperm, germ, and bran. Wholemeal flour contains all of these; white flour is without some or all of the germ or bran.[71][72]

Alcohol

[edit]Because cereals have a high starch content, they are often used to make industrial alcohol[45] and alcoholic drinks by fermentation. For instance, beer is produced by brewing and fermenting starch, mainly from cereal grains—most commonly malted barley.[46] Rice wines such as Japanese sake are brewed in Asia;[73] a fermented rice and honey wine was made in China some 9,000 years ago.[48]

Animal feed

[edit]

Cereals and their related byproducts such as hay are routinely fed to farm animals. Common cereals as animal food include maize, barley, wheat, and oats. Moist grains may be treated chemically or made into silage; mechanically flattened or crimped, and kept in airtight storage until used; or stored dry with a moisture content of less than 14%.[75] Commercially, grains are often combined with other materials and formed into feed pellets.[76]

Nutrition

[edit]Whole-grain and processed

[edit]

As whole grains, cereals provide carbohydrates, polyunsaturated fats, protein, vitamins, and minerals. When processed by the removal of the bran and germ, all that remains is the starchy endosperm.[71] In some developing countries, cereals constitute a majority of daily sustenance. In developed countries, cereal consumption is moderate and varied but still substantial, primarily in the form of refined and processed grains.[78]

Amino acid balance

[edit]Some cereals are deficient in the essential amino acid lysine, obliging vegetarian cultures to combine their diet of cereal grains with legumes to obtain a balanced diet. Many legumes, however, are deficient in the essential amino acid methionine, which grains contain. Thus, a combination of legumes with grains forms a well-balanced diet for vegetarians. Such combinations include dal (lentils) with rice by South Indians and Bengalis, beans with maize tortillas, tofu with rice, and peanut butter with wholegrain wheat bread (as sandwiches) in several other cultures, including the Americas.[79] For feeding animals, the amount of crude protein measured in grains is expressed as grain crude protein concentration.[80]

Comparison of major cereals

[edit]| Per 45g serving | Barley | Maize | Millet | Oats | Rice | Rye | Sorgh. | Wheat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | kcal | 159 | 163 | 170 | 175 | 165 | 152 | 148 | 153 |

| Protein | g | 5.6 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 6.1 |

| Lipid | g | 1 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.1 |

| Carbohydrate | g | 33 | 35 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 34 | 32 | 32 |

| Fibre | g | 7.8 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 1.6 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 4.8 |

| Calcium | mg | 15 | 3 | 4 | 24 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 15 |

| Iron | mg | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Magnesium | mg | 60 | 57 | 51 | 80 | 52 | 50 | 74 | 65 |

| Phosphorus | mg | 119 | 108 | 128 | 235 | 140 | 149 | 130 | 229 |

| Potassium | mg | 203 | 129 | 88 | 193 | 112 | 230 | 163 | 194 |

| Sodium | mg | 5 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zinc | mg | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.9 |

| Thiamine (B1) | mg | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.19 |

| Riboflavin (B2) | mg | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Niacin (B3) | mg | 2 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 3.0 |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | mg | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Pyridoxine (B6) | mg | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Folic acid (B9) | mcg | 9 | 11 | 38 | 25 | 10 | 17 | 9 | 19 |

Production and trade commodities

[edit]

Cereals constitute the world's largest commodities by tonnage, whether measured by production[82] or by international trade. Several major producers of cereals dominate the market.[83] Because of the scale of the trade, some countries have become reliant on imports, thus cereals pricing or availability can have outsized impacts on countries with a food trade imbalance and thus food security.[84] Speculation, as well as other compounding production and supply factors leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, created rapid inflation of grain prices during the 2007–2008 world food price crisis.[85] Other disruptions, such as climate change or war related changes to supply or transportation can create further food insecurity; for example the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 disrupted Ukrainian and Russian wheat supplies causing a global food price crisis in 2022 that affected countries heavily dependent on wheat flour.[86][87][88][89]

Production

[edit]

Cereals are the world's largest crops by tonnage of grain produced.[82] Three cereals, maize, wheat, and rice, together accounted for 89% of all cereal production worldwide in 2012, and 43% of the global supply of food energy in 2009,[90] while the production of oats and rye has drastically fallen from their 1960s levels.[91]

Other cereals not included in the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization statistics include wild rice, which is grown in small amounts in North America, and teff, an ancient grain that is a staple in Ethiopia.[92] Teff is grown in sub-Saharan Africa as a grass primarily for feeding horses. It is high in fiber and protein. Its flour is often used to make injera. It can be eaten as a warm breakfast cereal like farina with a chocolate or nutty flavor.[92]

-

Production of cereals worldwide, by country in 2021

The table shows the annual production of cereals in 1961, 1980, 2000, 2010, and 2019/2020.[a][93][91]

| Grain | Worldwide production

(millions of metric tons) |

Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 1980 | 2000 | 2010 | 2019/20 | ||

| Maize (corn) | 205 | 397 | 592 | 852 | 1,148 | A staple food of people in the Americas, Africa, and of livestock worldwide; often called corn in North America, Australia, and New Zealand. A large portion of maize crops are grown for purposes other than human consumption.[92] |

| Rice[b] Production is in milled terms. | 285 | 397 | 599 | 697 | 755 | The primary cereal of tropical and some temperate regions. Staple food in most of Brazil, other parts of Latin America and some other Portuguese-descended cultures, parts of Africa (even more before the Columbian exchange), most of South Asia and the Far East. Largely overridden by breadfruit (a dicot tree) during the South Pacific's part of the Austronesian expansion.[92] |

| Wheat | 222 | 440 | 585 | 641 | 768 | The primary cereal of temperate regions. It has a worldwide consumption but it is a staple food of North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Brazil and much of the Greater Middle East. Wheat gluten-based meat substitutes are important in the Far East (albeit less than tofu) and are said to resemble meat texture more than others.[92] |

| Barley | 72 | 157 | 133 | 123 | 159 | Grown for malting and livestock on land too poor or too cold for wheat.[92] |

| Sorghum | 41 | 57 | 56 | 60 | 58 | Important staple food in Asia and Africa and popular worldwide for livestock.[92] |

| Millet | 26 | 25 | 28 | 33 | 28 | A group of similar cereals that form an important staple food in Asia and Africa.[92] |

| Oats | 50 | 41 | 26 | 20 | 23 | Popular worldwide as a breakfast food, such as in porridge, and livestock feed.[94] |

| Triticale | 0 | 0.17 | 9 | 14 | — | Hybrid of wheat and rye, grown similarly to rye.[92] |

| Rye | 35 | 25 | 20 | 12 | 13 | Important in cold climates. Rye grain is used for flour, bread, beer, crispbread, some whiskeys, some vodkas, and animal fodder.[92] |

| Fonio | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.56 | — | Several varieties are grown as food crops in Africa.[92] |

Trade

[edit]

Cereals are the most traded commodities by quantity in 2021, with wheat, maize, and rice the main cereals involved. The Americas and Europe are the largest exporters, and Asia is the largest importer.[83] The largest exporter of maize is the US, while India is the largest exporter of rice. China is the largest importer of maize and of rice. Many other countries trade cereals, both as exporters and as importers.[83] Cereals are traded as futures on world commodity markets, helping to mitigate the risks of changes in price for example, if harvests fail.[95]

-

Main traded cereals, top import, export in 2021

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul (2012). Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice (6th ed.). Thames & Hudson. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-500-28976-1.

- ^ "The Development of Agriculture". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Hancock, James F. (2012). Plant evolution and the origin of crop species (3rd ed.). CABI. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-84593-801-7. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ UN Industrial Development Organization, International Fertilizer Development Center (1998). The Fertilizer Manual (3rd ed.). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7923-5032-3. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Purugganan, Michael D.; Fuller, Dorian Q. (1 February 2009). "The nature of selection during plant domestication" (PDF). Nature. 457 (7231): 843–848. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..843P. doi:10.1038/nature07895. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19212403. S2CID 205216444.

- ^ Henry, R.J.; Kettlewell, P.S. (1996). Cereal Grain Quality. Chapman & Hall. p. 155. ISBN 978-9-4009-1513-8.

- ^ Matsuoka, Y.; Vigouroux, Y.; Goodman, M. M.; et al. (2002). "A single domestication for maize shown by multilocus microsatellite genotyping". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (9): 6080–4. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.6080M. doi:10.1073/pnas.052125199. PMC 122905. PMID 11983901.

- ^ Standage, Tom (2009). An Edible History of Humanity. New York: Walker & Company. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1782391654. (pdf)

- ^ Room, Adrian (1990). Who's Who in Classical Mythology. NTC Publishing. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-8442-5469-X.

- ^ "cereal (n.)". Etymonline. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "JHOM - Bread - Hebrew". www.jhom.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Mayshar, Joram; Moav, Omer; Pascali, Luigi (2022). "The Origin of the State: Land Productivity or Appropriability?". Journal of Political Economy. 130 (4): 1091–1144. doi:10.1086/718372. hdl:10230/57736. S2CID 244818703. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Kumar, Manoj; Williams, Matthias (29 January 2009). "Punjab, bread basket of India, hungers for change". Reuters.

- ^ The Government of Punjab (2004). Human Development Report 2004, Punjab (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2011. Section: "The Green Revolution", pp. 17–20.

- ^ "Lessons from the green revolution: towards a new green revolution". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

The green revolution was a technology package comprising material components of improved high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of two staple cereals (rice or "wheat"), irrigation or controlled "water" supply and improved moisture utilization, fertilizers and pesticides and associated management skills.

- ^ a b Sands, David C.; Morris, Cindy E.; Dratz, Edward A.; Pilgeram, Alice L. (2009). "Elevating optimal human nutrition to a central goal of plant breeding and production of plant-based foods". Plant Science. 177 (5): 377–389. Bibcode:2009PlnSc.177..377S. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.07.011. PMC 2866137. PMID 20467463.

- ^ "Did Quinoa Get Too Popular for Its Own Good?". HowStuffWorks. 5 November 2018. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Juliano, Bienvenido O.; Tuaño, Arvin Paul P. (2019). "Gross structure and composition of the rice grain". Rice. Elsevier. pp. 31–53. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-811508-4.00002-2. ISBN 978-0-12-811508-4.

- ^ Rosentrater & Evers 2018, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Clayton, W.D.; Renvoise, S.A. (1986). Genera Graminum: Grasses of the world. London: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 978-1900347754.

- ^ Cope, T.; Gray, A. (2009). Grasses of the British Isles. London: Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. ISBN 978-0901158420.

- ^ "Insect Pollination of Grasses". Australian Journal of Entomology. 3: 74. 1964. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1964.tb00625.x.

- ^ Rosentrater & Evers 2018, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Rosentrater & Evers 2018, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barr, Skylar; Sutton, Mason (2019). Technology of Cereals, Pulses and Oilseeds. Edtech. p. 54. ISBN 9781839472619. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b "The Rice Plant and How it Grows". International Rice Research Institute. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009.

- ^ Rosentrater & Evers 2018, pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Best Crops for Grazing". Successful Farming. 22 February 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Water Management". International Rice Research Institute. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Gupta, Phool Chand; O'Toole, J. C. O'Toole (1986). Upland Rice: A Global Perspective. International Rice Research Institute. ISBN 978-971-10-4172-4.

- ^ Danovich, Tove (15 December 2015). "Move over, quinoa: sorghum is the new 'wonder grain'". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ "14th International Cereal Rusts and Powdery Mildews Conference". Aarhus University. 2015. pp. 1–163. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023.

- ^ Goswami, R.; Kistler, H. (2004). "Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops". Molecular Plant Pathology. 5 (6). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 515–525. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00252.x. ISSN 1464-6722. PMID 20565626. S2CID 11548015.

- ^ Singleton, Grant R; Lorica, Renee P; Htwe, Nyo Me; Stuart, Alexander M (1 October 2021). "Rodent management and cereal production in Asia: Balancing food security and conservation". Pest Management Science. 77 (10): 4249–4261. doi:10.1002/ps.6462. PMID 33949075.

- ^ "Deer (Overview) Interaction with Humans - Damage to Agriculture | Wildlife Online". www.wildlifeonline.me.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Constable, George; Somerville, Bob (2003). A Century of Innovation: Twenty Engineering Achievements That Transformed Our Lives, Chapter 7, Agricultural Mechanization. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-08908-5. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Cereal Straw". University of Kentucky. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Walker, Pete; Thomson, A.; Maskell, D. (2020). "Straw bale construction". Nonconventional and Vernacular Construction Materials. Elsevier. pp. 189–216. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102704-2.00009-3. ISBN 978-0-08-102704-2.

- ^ Erkmen, Osman; Bozoglu, T. Faruk, eds. (2016). "Spoilage of Cereals and Cereal Products". Food Microbiology: Principles into Practice. Wiley. pp. 364–375. doi:10.1002/9781119237860.ch21. ISBN 978-1-119-23776-1.

- ^ Papageorgiou, Maria; Skendi, Adriana (2018). "1 Introduction to cereal processing and by-products". In Galanakis, Charis M. (ed.). Sustainable Recovery and Reutilization of Cereal Processing By-Products. Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition. Woodhead Publishing. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-0-08-102162-0. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Astier, Marta; Odenthal, Georg; Patricio, Carmen; Orozco-Ramírez, Quetzalcoatl (2 January 2019). "Handmade tortilla production in the basins of lakes Pátzcuaro and Zirahuén, Mexico". Journal of Maps. 15 (1). Informa UK: 52–57. Bibcode:2019JMaps..15...52A. doi:10.1080/17445647.2019.1576553. ISSN 1744-5647.

- ^ "Varieties". Rice Association. 2 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "The Malting Process". Brewing With Briess. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Malting - an overview". Science Direct. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Paul Burke (1938). Information on Industrial Alcohol. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Chemistry and Soils. pp. 3–4. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ a b Barth, Roger (2013). "1. Overview". The Chemistry of Beer: The Science in the Suds. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-67497-0.

- ^ "Standards of Identity for Distilled Spirits, Title 27 Code of Federal Regulations, Pt. 5.22" (PDF). Retrieved 17 October 2008.

Bourbon whiskey ... Corn whiskey ... Malt whiskey ... Rye whiskey ... Wheat whiskey

- ^ a b Borrell, Brendan (20 August 2009). "The Origin of Wine". Scientific American.

- ^ Briggs, D. E. (1978). "Some uses of barley malt". Barley. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 560–586. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5715-2_16. ISBN 978-94-009-5717-6.

products include malt extracts (powders and syrups), diastase, beer, whisky, ... and malt vinegar.

- ^ "International Starch: Production of corn starch". Starch.dk. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Glucose-fructose syrup: How is it produced?". European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Takken, Ingrid; Govers, Gerard; Jetten, Victor; Nachtergaele, Jeroen; Steegen, An; Poesen, Jean (2001). "Effects of tillage on runoff and erosion patterns". Soil and Tillage Research. 61 (1–2). Elsevier: 55–60. Bibcode:2001STilR..61...55T. doi:10.1016/s0167-1987(01)00178-7. ISSN 0167-1987.

- ^ Sundquist, Bruce (2007). "1 Irrigation overview". The Earth's Carrying Capacity: some literature reviews. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. p. 454.

- ^ Werner, Wilfried (2009). "6. Environmental Aspects". Fertilizers. Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.n10_n05. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- ^ Nabuurs, G-J.; Mrabet, R.; Abu Hatab, A.; Bustamante, M.; et al. "7: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Uses" (PDF). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. p. 750. doi:10.1017/9781009157926.009.

- ^ "Neonicotinoids: risks to bees confirmed". European Food Safety Authority. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Kaplan, Sarah. "A recipe for fighting climate change and feeding the world". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Glover, Jerry D.; Cox, Cindy M.; Reganold, John P. (2007). "Future Farming: A Return to Roots?" (PDF). Scientific American. 297 (2): 82–89. Bibcode:2007SciAm.297b..82G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0807-82. PMID 17894176.

- ^ Jensen, Erik Steen; Carlsson, Georg; Hauggaard-Nielsen, Henrik (2020). "Intercropping of grain legumes and cereals improves the use of soil N resources and reduces the requirement for synthetic fertilizer N: A global-scale analysis". Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 40 (1). Springer Science and Business Media: 5. Bibcode:2020AgSD...40....5J. doi:10.1007/s13593-020-0607-x. ISSN 1774-0746.

- ^ Vermeulen, S.J.; Dinesh, D. (2016). "Measures for climate change adaptation in agriculture. Opportunities for climate action in agricultural systems. CCAFS Info Note". Copenhagen, Denmark: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security.

- ^ "How to cook perfect rice". BBC Food. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Davidson 2014, pp. 642–643 Porridge.

- ^ Bilow, Rochelle (17 September 2015). "What's the difference between muesli and granola? A very important primer". Bon Appétit. Condé Nast. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Vaclavik, Vickie A.; Christian, Elizabeth W. (2008). "Grains: Cereal, Flour, Rice, and Pasta". Essentials of Food Science. New York: Springer New York. pp. 81–105. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-69940-0_6. ISBN 978-0-387-69939-4.

- ^ "The history of flour - The FlourWorld Museum Wittenburg – Flour Sacks of the World". flour-art-museum.de. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Peña, R. J. "Wheat for bread and other foods". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

Wheat, in the form of bread, provides more nutrients to the world population than any other single food source.

- ^ Davidson 2014, pp. 516–517 Mexico.

- ^ "Medieval Daily Bread Made of Rye". Medieval Histories. 15 January 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

Sources: Råg. Article in Kulturhistorisk leksikon for Nordisk Middelalder. Rosenkilde and Bagger 1982.

- ^ Davidson 2014, p. 682 Rice.

- ^ a b "Cereals and wholegrain foods". Better Health Channel. 6 December 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

in consultation with and approved by Victoria State Government Department of Health; Deakin University

- ^ Davidson 2014, pp. 315–316 Flour.

- ^ Davidson 2014, p. 701.

- ^ "Cereals in poultry diets – Small and backyard poultry". poultry.extension.org. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Feeding cereal grains to livestock: moist vs dry grain". Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Thomas, M.; van Vliet, T.; van der Poel, A.F.B. (1998). "Physical quality of pelleted animal feed 3. Contribution of feedstuff components". Animal Feed Science and Technology. 70 (1–2): 59–78. doi:10.1016/S0377-8401(97)00072-2.

- ^ "Storing Whole Grains". Whole Grains Council. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Mundell, E.J. (9 July 2019). "More Americans Are Eating Whole Grains, But Intake Still Too Low". HealthDay. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Prime Mover: A Natural History of Muscle. W.W. Norton & Company. 17 August 2003. p. 301. ISBN 9780393247312..

- ^ Edwards, J.S.; Bartley, E.E.; Dayton, A.D. (1980). "Effects of Dietary Protein Concentration on Lactating Cows". Journal of Dairy Science. 63 (2): 243. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(80)82920-1.

- ^ "FoodData Central". US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ a b "IDRC - International Development Research Centre". International Development Research Centre. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- ^ a b c World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023. Food and Agriculture Organization. 2023. doi:10.4060/cc8166en. ISBN 978-92-5-138262-2. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ OECD; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (6 July 2023). "3. Cereals". OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023-2032. OECD. doi:10.1787/19991142. ISBN 978-92-64-61933-3.

- ^ "World Food Situation". FAO. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Pei, Qing; Zhang, David Dian; Xu, Jingjing (August 2014). "Price Responses of Grain Market under Climate Change in Pre-industrial Western Europe by ARX Modelling". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications. 2014 4th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications (SIMULTECH). pp. 811–817. doi:10.5220/0005025208110817. ISBN 978-989-758-038-3. S2CID 8045747.

- ^ "Climate Change is Likely to Devastate the Global Food Supply". Time. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "CLIMATE CHANGE LINKED TO GLOBAL RISE IN FOOD PRICES – Climate Change". Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Lustgarten, Abrahm (16 December 2020). "How Russia Wins the Climate Crisis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "ProdSTAT". FAOSTAT. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ a b Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (17 October 2013). "Crop Yields". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Wrigley, Colin W.; Corke, Harold; Seetharaman, Koushik; Faubion, Jonathan, eds. (2016). Encyclopedia of food grains (2nd ed.). Kidlington, Oxford, England: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-394786-4. OCLC 939553708.

- ^ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. "FAOSTAT". FAOSTAT (Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics Division). Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Types of Oats". Whole Grains Council. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ Atkin, Michael (2024). "6. Grains". Agricultural Commodity Markets: A Guide to Futures Trading. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781003845379.

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023, FAO, FAO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2023, FAO, FAO.- Davidson, Alan (2014). "Mexico". The Oxford Companion to Food (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- Rosentrater, Kurt August; Evers, Anthony D. (2018). Kent's Technology of Cereals: An Introduction for Students of Food Science and Agriculture (5th ed.). Duxford, England: Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-08-100532-3. OCLC 1004672994.

Cereal

View on GrokipediaCereals, also known as cereal grains, are annual plants primarily from the grass family (Poaceae) cultivated for their starchy seeds, botanically termed caryopses, which consist of the endosperm, germ, and bran.[1][2] These grains serve as a foundational source of carbohydrates, providing roughly 50% of global dietary energy intake, with higher reliance in developing regions.[3] The principal cereals—wheat, rice, and maize—dominate production and consumption, accounting for over 60% of the world's food calories and occupying two-thirds of cropland, underscoring their role in sustaining human populations and livestock.[4][5] Global cereal output has expanded steadily, rising by 2% to include an additional 61 million tonnes in 2023 compared to 2022, driven largely by maize yields amid varying climatic conditions.[6] Beyond direct human consumption in forms like bread, porridge, and tortillas, cereals support animal feed, biofuels, and industrial processing, though challenges such as soil degradation and yield variability highlight dependencies on agronomic practices and environmental factors.[7]

History

Domestication in Prehistoric Times

The domestication of cereals marked a pivotal transition from hunter-gatherer societies to sedentary agriculture during the Neolithic period, occurring independently across multiple regions between approximately 12,000 and 7,000 years ago. This process involved selective pressures on wild grasses, favoring traits such as non-shattering rachises for easier seed retention, larger grains, and synchronized maturation, which reduced harvesting losses and enabled storage. Archaeobotanical evidence, including charred remains and phytoliths, alongside genetic analyses, indicates that early cultivation began with intensive foraging of wild stands before full domestication traits fixed in populations.[8][9] In the Fertile Crescent of the Near East, einkorn wheat (Triticum monococcum) and emmer wheat (T. dicoccum) were domesticated from wild progenitors around 11,500–10,500 years ago, with initial evidence from sites in the southern Levant and southeastern Turkey's Karacadag Mountains. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) followed closely, with non-brittle rachis mutations appearing by 10,000 years ago in the region's foothills, supported by spikelet remains from Syrian and Iraqi sites. These developments coincided with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, where cereal processing tools like sickles and grinding stones proliferated, though full domestication spanned 2,000–3,000 years of cultivation. Genetic studies confirm a single primary origin for barley in this arc-shaped zone, with reduced diversity in domesticated lineages reflecting founder effects.[10][11][12] In East Asia, rice (Oryza sativa) domestication began in the Yangtze River basin of China around 10,000 years ago, evidenced by phytoliths and grain impressions from Shangshan site sediments, indicating early wet-field management and selection against shattering. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum) emerged in northern China's Yellow River region by 10,000 years ago, with remains from Cishan showing intensified harvesting of wild stands transitioning to domesticated forms suited to arid conditions. These parallel trajectories highlight regional adaptations to monsoon climates and floodplains, distinct from Near Eastern dry-farming.[13][14] Maize (Zea mays) was domesticated in Mesoamerica's Balsas River valley of Mexico from teosinte (Zea mays ssp. parviglumis) approximately 9,000 years ago, with macrofossil cobs from Guila Naquitz cave exhibiting enlarged kernels and reduced glume coverage by 6,250 years ago. This protracted process, involving hybridization and selection for multi-rowed ears, is corroborated by starch grain and cob morphology analyses, though maize contributed minimally to diets until 4,700 years ago in some areas.[15][16] In sub-Saharan Africa, sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) domestication occurred in the Sudanian savannas around 5,000–3,000 years ago from wild S. arundinaceum and related taxa, with archaeological grains from eastern Sudan sites showing tougher glumes and larger seeds. Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) followed in West Africa's Sahel by the 2nd millennium BCE, evidenced by spikelet bases from Dhar Tichitt, Mauritania, reflecting selection for non-shattering in semi-arid environments. These later timelines relative to Eurasia underscore Africa's diverse ecological niches and delayed intensification compared to riverine cores elsewhere.[17][18]Role in Ancient Civilizations and Expansion

In Mesopotamia, barley emerged as the primary cereal due to its adaptation to dry, saline soils, supplemented by emmer wheat, which supported surplus production essential for urban centers and state formation around 3000 BCE.[19] These crops facilitated trade networks and administrative systems, as grain procurement underpinned imperial growth in the region.[20] Wheat and barley cultivation, domesticated in the Fertile Crescent circa 10,000 years ago, spread westward to Europe and Egypt by 6000 BCE, enabling basin irrigation systems that yielded staple breads and beers critical to Egyptian society's nutritional base from the Old Kingdom onward.[21][22] Cereal agriculture expanded eastward via distinct routes, with barley reaching the Indus Valley by the second millennium BCE as a dominant grain, integral to Harappan urban planning and storage infrastructures like granaries.[23] In China, millets dominated the Yellow River basin while rice cultivation arose independently in the Yangtze region around 8000 years ago, forming the agrarian foundation for early dynastic states.[24] Barley and wheat followed divergent paths into East Asia, adapting to high-altitude Tibetan plateaus before integrating into lowland farming by the Iron Age. Independently in Mesoamerica, maize domestication from teosinte began approximately 9000 years ago, evolving into the cornerstone of Mayan and other societies by 2000 BCE, where it supplied caloric needs, shaped religious iconography via the Maize God, and drove agricultural intensification through techniques like slash-and-burn.[25][26] This crop's yield improvements—larger seeds and non-shattering ears—mirrored Old World cereal evolutions, fostering population densities and complex polities despite isolated development.[27] Overall, cereal surpluses across these cradles of civilization enabled sedentism, labor specialization, and hierarchical structures, with dissemination via migration and exchange amplifying their socioeconomic impact.[9]Industrialization and the Green Revolution

The industrialization of cereal production commenced in the 19th century with key mechanization advances that reduced labor intensity and enabled larger-scale farming. In 1831, Cyrus McCormick invented the mechanical reaper, the first machine to harvest grain efficiently, allowing one operator to cut the work of several laborers in wheat and other cereal fields.[28] This innovation spread rapidly in the United States and Europe, contributing to a shift from subsistence to commercial cereal agriculture. By the late 19th century, steam-powered threshing machines separated grains from stalks more quickly than manual methods, further boosting post-harvest efficiency for crops like barley and oats.[29] The early 20th century introduced internal combustion engines, with gasoline tractors emerging around 1892 and gaining traction by the 1910s, replacing animal draft power and permitting cultivation of expansive cereal monocultures.[30] Combine harvesters, which integrated reaping, threshing, and winnowing, became viable in the 1910s–1920s, exemplified by models from International Harvester; by mid-century, their adoption in the U.S. cut wheat harvest times from weeks to days per field.[31] Concurrently, the Haber-Bosch process, scaled commercially by 1913, synthesized ammonia for nitrogen fertilizers, addressing soil nutrient depletion in intensive cereal rotations and enabling yield doublings in nitrogen-responsive grains like maize and wheat.[32] These developments tripled U.S. farm output per worker between 1900 and 1950, though they concentrated production in mechanized regions and increased reliance on fossil fuels.[28] The Green Revolution, spanning roughly 1943–1970, amplified industrialization through coordinated agronomic packages tailored to cereals, originating with wheat breeding at the Rockefeller Foundation's Mexican program under Norman Borlaug. Semi-dwarf wheat varieties, resistant to lodging under heavy fertilization, raised Mexican yields from 750 kg/ha in the 1940s to 3,200 kg/ha by 1960, averting food shortages.[33] These strains, introduced to India and Pakistan in 1965–1966 amid famine threats, tripled wheat output there by 1970, with India's production surging from 11 million tons in 1960 to 26 million tons in 1971.[34] For rice, the International Rice Research Institute released high-yielding IR8 variety in 1966, which, combined with expanded irrigation and pesticides, boosted Asian yields by 30–50% within a decade; maize hybrids, refined earlier in the U.S. from the 1930s, extended similar gains in Latin America and Africa.[35] Globally, cereal production in developing nations doubled between 1961 and 1985, supporting population growth from 3 billion to over 4.5 billion without proportional farmland expansion.[36] While these advances demonstrably curbed starvation—Borlaug's work credited with saving over a billion lives—their heavy dependence on synthetic inputs fostered environmental trade-offs, including groundwater depletion from irrigation (e.g., India's Punjab region saw water tables drop 1 meter annually by the 1980s) and soil degradation from monocropping.[37] Empirical data from long-term trials indicate that without continued fertilizer application, HYV yields revert toward traditional levels, underscoring a causal link to input-intensive systems rather than inherent genetic superiority alone.[38] Institutional analyses, often from development agencies, emphasize productivity gains but understate biodiversity losses, as cereal acreage expanded at the expense of pulses and other crops.[36]Botanical and Genetic Characteristics

Classification within the Grass Family

Cereals comprise a subset of cultivated species within the Poaceae family (also known as Gramineae), a monocotyledonous group of approximately 11,500 species distributed across 768 genera, representing the fifth-largest angiosperm family.[39] This family is characterized by wind-pollinated flowers, reduced perianth structures, and spikelet inflorescences, with cereals specifically valued for their edible, starchy grains derived from the caryopses.[40] Phylogenetic analyses, incorporating molecular data such as rDNA and chloroplast genes, have refined the classification into 12 subfamilies, emphasizing clades like the BEP (Bambusoideae-Ehrhartoideae-Pooideae) and PACMAD (Panicoideae-Arundinoideae-Chloridoideae-Micrairoideae-Danthonioideae-Aristidoideae), where most cereals reside.[41] The major cereal crops are concentrated in three subfamilies: Pooideae (cool-season, C3 photosynthetic pathway grasses predominant in temperate regions), Panicoideae (warm-season, C4 grasses adapted to tropical and subtropical environments), and Ehrhartoideae (a smaller group including aquatic-adapted species).[40] Pooideae, the largest subfamily with over 3,000 species, encompasses tribes such as Triticeae (e.g., wheat, barley, rye) and Aveneae (e.g., oats), reflecting shared morphological traits like compact spike inflorescences and vernalization requirements.[42] Panicoideae, with around 3,300 species, includes the economically dominant Andropogoneae tribe for maize and sorghum, and Paniceae for millets, distinguished by open panicle inflorescences and efficient C4 carbon fixation enhancing drought tolerance.[40] Ehrhartoideae features the Oryzeae tribe, home to rice, with adaptations for flooded cultivation.[43] The classification of key cereals is summarized below:| Cereal Crop | Genus (Species Example) | Subfamily | Tribe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Triticum (T. aestivum) | Pooideae | Triticeae [43] |

| Barley | Hordeum (H. vulgare) | Pooideae | Triticeae [43] |

| Oats | Avena (A. sativa) | Pooideae | Aveneae [40] |

| Rye | Secale (S. cereale) | Pooideae | Triticeae [43] |

| Rice | Oryza (O. sativa) | Ehrhartoideae | Oryzeae [43] |

| Maize | Zea (Z. mays) | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae [43] |

| Sorghum | Sorghum (S. bicolor) | Panicoideae | Andropogoneae [40] |

| Pearl Millet | Pennisetum (P. glaucum) | Panicoideae | Paniceae [40] |

Key Species and Varietal Diversity

The major cereal species, defined as edible grains from the Poaceae family, include wheat (Triticum spp.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), maize (Zea mays L.), barley (Hordeum vulgare L.), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench), and various millets, which collectively dominate global production surpassing 2.8 billion metric tons in the 2023-24 season.[45][46] These species exhibit substantial varietal diversity through polyploidy, geographic adaptation, and selective breeding for traits like yield, disease resistance, and processing quality.[47] Wheat production relies primarily on bread wheat (T. aestivum L.), a hexaploid species (2n=42, AABBDD genomes) accounting for over 95% of output, alongside tetraploid durum wheat (T. durum Desf.) for pasta and semolina. Varietal diversity includes ancient forms like spelt (T. spelta L.) and emmer (T. dicoccum Schrank), but modern cultivars—numbering in the thousands—stem from 20th-century breeding emphasizing high gluten content for leavened breads and hardness for milling.[48] Genetic analyses using SNP markers reveal population structures tied to breeding pedigrees and regional adaptations, with narrower diversity in elite lines prompting wild relative incorporation for resilience.[49] Rice (O. sativa) divides into indica and japonica subspecies, with indica varieties featuring long, slender grains suited to tropical lowlands and lower stickiness upon cooking due to intermediate amylose levels, while japonica produces short, plump grains with higher amylopectin for sticky textures in temperate uplands.[50] This differentiation, rooted in ecogeographic races, supports thousands of landraces and hybrids bred for flood tolerance, aroma, and nutrition, including African rice (O. glaberrima Steud.) as a distinct species with weedy traits.[51] Maize, strictly Z. mays, displays kernel-type diversity including dent (field corn for feed and ethanol, with soft starch collapse), flint (hard, vitreous kernels for storage in tropics), flour (soft endosperm for grinding), popcorn (expanded pericarp), and sweet corn (high sugar for fresh eating).[52] Derived from teosinte domestication around 9,000 years ago, varietal proliferation via open-pollinated and hybrid selections has yielded cultivars for maturity groups, color, and pest resistance, with over 300 races documented in Latin America.[53] Barley features two-row (H. vulgare subsp. distichon) for malting in brewing and six-row for higher yield in feed, while sorghum includes grain sorghums for food in Africa and Asia alongside sweet and forage types. Millets encompass pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) for drought-prone areas and proso millet (Panicum miliaceum L.), with varieties selected for tillering and bird resistance. Oats (Avena sativa L.) emphasize hulless or naked forms for milling, and rye (Secale cereale L.) prioritizes winter-hardy cultivars for poor soils.[54] This varietal spectrum, amplified by hybridization since the mid-20th century, balances productivity gains against genetic erosion risks in monoculture systems.[55]Physiological Traits and Adaptations

Cereal crops, primarily annual herbaceous monocots in the Poaceae family, display determinate growth patterns, initiating reproductive development after a vegetative phase characterized by tillering, where axillary buds produce side shoots to increase productive culms. [56] Tillering enhances resource capture and yield potential, with the number of tillers influenced by environmental factors such as nutrient availability and planting density. [57] Physiologically, cereals vary in photosynthetic pathways: wheat, rice, and barley employ the C3 pathway, which fixes CO2 via Rubisco but suffers photorespiration losses under high light and temperature; in contrast, maize, sorghum, and pearl millet utilize the C4 pathway, concentrating CO2 around Rubisco to minimize photorespiration and improve water-use efficiency in arid conditions. [58] [59] [60] Winter varieties of cereals like wheat and barley require vernalization, a cold-induced physiological process necessitating prolonged exposure to low temperatures (typically 0–10°C for 4–8 weeks) to transition from vegetative to reproductive growth by upregulating floral meristem identity genes such as VRN1. [61] [62] This adaptation synchronizes flowering with favorable spring conditions in temperate regions, with vernalization sensitivity varying by genotype—spring types flower without cold exposure. [63] Photoperiodism further modulates development, with long-day requirements in many temperate cereals promoting heading under increasing day lengths. [64] Adaptations to abiotic stresses include morphological shifts like deeper root systems and reduced tillering under drought to conserve water, alongside physiological responses such as osmotic adjustment via solute accumulation and enhanced antioxidant activity to mitigate oxidative damage from heat or salinity. [65] [66] In C4 cereals, Kranz anatomy—bundle sheath cells surrounding veins—facilitates spatial CO2 concentration, conferring superior heat tolerance (optimal at 30–40°C) compared to C3 types (optimal at 15–25°C). [67] These traits underpin cereal resilience across diverse agroecologies, from Mediterranean drylands to tropical highlands, though breeding continues to target improved stress tolerance via root architecture and photosynthetic efficiency. [68] [69]Agronomic Cultivation

Soil, Climate, and Site Selection

Cereal crops generally require well-drained soils with adequate fertility to support root penetration and nutrient absorption, as poor drainage promotes anaerobic conditions detrimental to most species. Loamy soils, combining sand, silt, and clay in balanced proportions, facilitate aeration and water retention without excessive compaction, yielding higher productivity compared to sandy or heavy clay soils alone. For wheat and barley, medium-fertile loams with good humus content are ideal, enabling tolerance to moderate alkalinity but sensitivity to acidity below pH 6.0, which induces aluminum toxicity and reduces yields. Maize demands deeper, nutrient-rich soils to accommodate its fibrous roots, with soil sampling recommended to assess nitrogen depth and organic matter levels prior to planting. Rice, uniquely among major cereals, thrives in heavy clay soils that retain water for flooded paddies, where anaerobic decomposition supports growth but risks methane emissions and nutrient leaching if mismanaged.[70][71][72] Optimal climates vary by species, reflecting adaptations to temperature, precipitation, and photoperiod, with temperate cereals like wheat favoring cooler regimes of 15–25°C during growth and vernalization requirements below 10°C for flowering initiation. Barley exhibits similar cool-season preferences but greater drought tolerance, succeeding in regions with 400–800 mm annual rainfall, while maize requires warmer conditions of 20–30°C and 500–800 mm water, often supplemented by irrigation to avoid pollination failure under heat stress above 35°C. Rice demands humid subtropical or tropical climates with 1,000–2,000 mm rainfall or equivalent irrigation, optimal temperatures of 22–31°C, and 5–6 hours daily sunshine to maximize photosynthesis without excessive evaporation. These parameters underscore causal links between climatic mismatches and reduced yields, as evidenced by historical data showing 4–13% global shortfalls in maize, wheat, and barley production attributable to warming trends deviating from historical optima.[73][74][75] Site selection prioritizes topography and prior land use to minimize erosion and disease carryover, favoring gently sloping fields with 0–5% gradients for uniform drainage and machinery access in upland cereals. Low-lying or flood-prone sites suit rice paddies but risk waterlogging for wheat or maize, where perched water tables elevate root disease incidence; soil history must exclude persistent pathogens from prior solanaceous or brassica crops. Ecological assessments, including wind exposure and proximity to pollinator habitats for hybrid varieties, further inform choices, with zoning and historical productivity data guiding avoidance of contaminated or nutrient-depleted parcels. Comprehensive suitability mapping integrates these factors, revealing that physico-chemical soil profiles and microclimatic variations can limit cereal viability in marginal zones without amendments.[76][77][78]| Cereal | Preferred Soil Texture | Optimal pH | Key Climate Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Loamy, well-drained | 6.0–7.5 | Cool temperate; 500–1,000 mm rainfall; frost-tolerant vernalization |

| Barley | Medium loamy, porous | 6.0–8.0 | Cool, drought-tolerant; 400–800 mm rainfall |

| Maize | Deep, fertile loamy | 5.8–7.0 | Warm; 20–30°C; irrigation often needed |

| Rice | Heavy clay, water-retentive | 5.5–7.0 | Humid tropical/subtropical; flooded conditions |

Planting, Growth Management, and Harvesting

Planting of cereal crops involves site-specific timing and methods tailored to species, climate, and soil conditions to optimize establishment and yield. For maize, optimal planting in the U.S. Midwest occurs from late April to early May, with seeds sown 5 to 7.5 centimeters deep in rows spaced 76 to 100 centimeters apart, using seeding rates of 11 to 17 kilograms per hectare for grain production.[79][80] Wheat in temperate regions like the southern U.S. is typically drilled in November, with seeding rates of about 26 seeds per square foot when planted within recommended windows to ensure tillering and stand density.[81] Rice planting varies, with direct seeding or transplanting; in subtropical areas, yields peak from mid-March plantings, as later dates reduce productivity due to shorter growth periods and heat stress.[82] Growth management encompasses nutrient application, water supply, and pest mitigation to support physiological stages from germination to maturity. Fertilization targets nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium needs, with cereals under irrigation requiring precise rates to avoid deficiencies or excesses that impair yield; for instance, wheat demands balanced inputs during stem elongation and grain fill for maximal biomass accumulation.[83] Irrigation is critical for rice, often involving flooded paddies to suppress weeds and enhance nutrient uptake, while maize and wheat rely on supplemental watering in dry conditions to maintain transpiration and photosynthesis.[83] Pest control employs integrated pest management (IPM), combining monitoring, cultural practices like crop rotation, and targeted pesticides to minimize losses from insects, diseases, and weeds without over-reliance on chemicals that could foster resistance.[84] Harvesting occurs when grain reaches physiological maturity, typically at 12-18% moisture content to minimize drying costs and quality degradation. Major cereals like wheat and maize are mechanically harvested using combine harvesters that cut, thresh, and clean in one pass, suitable for large-scale operations and reducing labor compared to manual sickles or reapers used in smaller fields.[85][86] Rice harvesting may involve combines adapted for wet conditions or manual methods followed by threshing, with timing critical to avoid shattering losses in upright panicles.[86] Post-cutting, grains are separated from chaff via threshing and winnowing, ensuring clean product for storage.[85]Post-Harvest Handling and Storage

Post-harvest handling of cereal grains begins immediately after harvesting to minimize quality degradation and losses. Threshing separates grains from ears or cobs, followed by winnowing or cleaning to remove chaff, dirt, and impurities, which can harbor pests or promote spoilage if left in storage.[87] Drying is essential, reducing moisture content from typical harvest levels of 20-30% to safe storage thresholds of 13-14% or lower to inhibit fungal growth and microbial activity.[88] [89] Effective storage requires controlled environmental conditions to preserve grain viability and nutritional value. Grains should be stored at temperatures below 15°C with relative humidity under 65-70% to prevent respiration-induced heating and mold development.[90] [91] Aeration systems in silos or bins facilitate cooling and uniform moisture distribution, while regular monitoring detects hot spots or infestations early.[92] Common storage methods include bulk silos for large-scale operations, bagged storage for smaller quantities, and hermetic systems that limit oxygen to suppress insects without chemical fumigants.[93] [94] Pest management is critical, as insects like weevils and rodents can cause significant losses through consumption and contamination. Integrated approaches combine sanitation, temperature control, and targeted fumigation with phosphine or controlled atmospheres, though overuse risks resistance development.[95] Post-harvest losses in cereals average 14% globally before retail, rising to 20-50% in regions with inadequate infrastructure due to spoilage, pests, and improper handling.[96] [95] In traditional systems, losses hover around 5%, but inefficiencies in drying and storage amplify them where modern equipment is absent.[97]Global Production and Economics

Major Producing Regions and Yield Trends

Asia dominates global cereal production, accounting for more than 50% of the total output, with China and India as the leading producers due to extensive cultivation of rice, wheat, and maize across vast arable lands supported by monsoon climates and irrigation systems.[7] In 2023, China's cereal production exceeded 633 million metric tons, driven by high-yield hybrid varieties and intensive farming practices, while India's output focused on rice and wheat contributed substantially to regional totals.[98] North America, particularly the United States, ranks second globally, with maize production reaching a record 427 million metric tons in 2023, facilitated by mechanized large-scale farming, genetically modified seeds, and fertile Midwest soils.[7] Europe and South America follow, with Russia and Brazil producing significant wheat and maize volumes, respectively, though geopolitical disruptions like the Russia-Ukraine conflict have impacted European yields and exports.[6]| Country | Production (million metric tons, 2023) |

|---|---|

| China | 634 |

| United States | ~500 (dominated by maize) |

| India | ~330 (rice and wheat) |

| Brazil | ~120 (maize) |

| Russia | ~100 (wheat) |

Trade Dynamics and Market Influences

Global cereal trade volumes fluctuate based on production surpluses and import demands, with the FAO forecasting 497.1 million tonnes for 2025/26, an increase of 3.7 million tonnes from prior estimates driven by expected higher wheat and coarse grain exports.[7] In 2023, the United States led exporters by value at $19.11 billion, followed by Argentina, France, Canada, and Russia, reflecting competitive advantages in scale and logistics for wheat, corn, and other grains.[104] Importers, primarily in Asia and North Africa, rely on these flows for food security, with China significantly increasing broken rice imports from 2020 to 2022 amid corn price surges, substituting for animal feed.[105] Trade dynamics are shaped by regional production cycles and transport efficiencies, such as bulk carrier shipments from Americas and Black Sea ports, where disruptions like the 2022 Russia-Ukraine conflict initially spiked wheat exports via alternative routes before stabilizing.[106] Corn trade, heavily influenced by U.S. and Brazilian surpluses, supports dual food and biofuel demands, exposing it to energy market linkages and policy shifts.[107] Rice dynamics differ, with Asian exporters like India and Thailand dominating, though global competition and weather variability in monsoon-dependent regions affect flows to importers like the Philippines.[108] Market influences include weather-induced supply variability and geopolitical tensions, contributing to price volatility; wheat and corn prices rose 1.8-fold and 2.8-fold respectively from 2000 to 2023, correlated with crude oil dynamics and extreme events.[109] In 2024, the FAO Cereal Price Index fell 13.3% to an average 113.5 points, the second consecutive annual decline, due to abundant harvests in Europe, the U.S., and Black Sea exporters outpacing demand amid strong inter-exporter competition.[110][111] Additional factors encompass biofuel mandates boosting coarse grain demand and currency fluctuations impacting competitiveness, though ample global stocks tempered extremes in late 2024.[112][106]Policy Impacts Including Subsidies and Tariffs

In the United States, federal subsidies for cereal crops primarily operate through the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs under the 2018 Farm Bill, extended into subsequent years, covering commodities such as corn, wheat, and rice. Corn, the dominant subsidized cereal, received $3.2 billion in 2024, accounting for 30.5% of total federal farm subsidies, while direct government payments across agriculture are projected at $40.5 billion for 2025, driven largely by crop insurance premiums and revenue protections amid volatile prices. These mechanisms provide payments when market prices or revenues fall below reference levels, with base acre allocations favoring historic production of program crops, resulting in concentrated benefits to large-scale producers in the Midwest.[113][114][115] The European Union's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) allocates €387 billion for 2021-2027, with €291.1 billion directed to the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund for direct income support to farmers, including those producing cereals like wheat and barley. While coupled payments tied to cereal output have diminished, decoupled area-based payments still incentivize maintaining cereal acreage, though empirical analysis shows most CAP subsidies exert negative or insignificant effects on total factor productivity for cereal farms, except for targeted agri-environmental schemes. This structure has historically promoted surplus production, enabling export refunds that effectively subsidize EU cereal exports, depressing global prices.[116][117][118] Globally, agricultural subsidies totaling approximately $540 billion annually, with a significant portion directed toward cereals, stimulate production by 0.9% and greenhouse gas emissions by 0.6%, as modeled from production-linked incentives in major economies. These distort trade flows more severely than equivalent tariffs, with ad valorem equivalents of subsidy distortions roughly double those of tariffs in agriculture, fostering overproduction and market dumping that disadvantages unsubsidized farmers in developing countries.[119][120] Tariffs on cereal imports, governed by the World Trade Organization's Agreement on Agriculture since 1995, mandate tariffication of prior non-tariff barriers, with bound rates establishing ceilings—often exceeding 20% for cereals in many members—and permitting special safeguards for surges in imports. Applied tariffs remain higher in net-importing developing countries, averaging above bound commitments for grains, while major exporters like the US and EU maintain low or zero tariffs on cereals to facilitate outflows, though retaliatory measures, such as those in 2018-2019 trade disputes, imposed 25% tariffs on US agricultural products including soybeans (a key cereal feed), reducing exports by billions and redirecting trade to alternative markets.[121][122][123] These policies collectively elevate domestic cereal production in subsidized regions—evident in US corn yields sustained despite market signals—but suppress international prices, with EU export subsidies historically lowering global cereal values by encouraging dumping volumes exceeding 10 million tons annually in the 1990s-2000s. Environmentally, production-boosting subsidies correlate with intensified input use, contributing to soil degradation and emissions, while tariff protections in importers like Japan or Malaysia shield local producers but inflate consumer costs; simulations indicate subsidy removal could raise wheat prices 10-20% in such markets. Trade distortions from subsidies and retaliatory tariffs have reshaped flows, diminishing US shares in key destinations and heightening volatility, as seen in post-2018 grain export declines to China.[124][125][126]Nutritional Composition and Human Health

Macronutrient Profiles Across Cereals

Cereals, as staple grains, derive the majority of their caloric content from carbohydrates, primarily in the form of starch, which constitutes 60-80% of dry weight across species, enabling efficient energy storage and human utilization. Protein content varies significantly, from approximately 7% in rice to over 15% in oats, reflecting differences in endosperm composition and breeding priorities, while fats remain low at 1-6%, concentrated in the germ and bran layers. These profiles are measured on uncooked, whole-grain basis per 100 grams dry matter, though actual values fluctuate with cultivar, soil conditions, and processing; data from USDA analyses provide standardized averages.[127][128] The table below summarizes macronutrient compositions for major cereals, highlighting relative abundances: wheat and barley offer higher proteins suitable for bread-making gluten formation, oats provide elevated fats from lipids like avenolipids, and maize contains more extractable oils from its pericarp.| Cereal | Protein (g) | Fat (g) | Carbohydrates (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (whole) | 12.6 | 2.5 | 71.2 |

| Rice (brown) | 7.9 | 2.7 | 77.2 |

| Maize (corn) | 9.4 | 4.7 | 74.3 |

| Barley (pearled) | 12.5 | 2.3 | 73.5 |

| Oats | 16.9 | 6.9 | 66.3 |

| Sorghum | 11.0 | 3.3 | 72.9 |

| Millet | 11.0 | 4.2 | 72.9 |

Micronutrients, Digestibility, and Bioavailability

Cereals provide several micronutrients, including B vitamins such as thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, and folate, as well as minerals like iron, zinc, magnesium, and phosphorus, though concentrations vary by grain type and processing level.[131] Whole grain wheat contains approximately 3.6 mg of iron and 2.6 mg of zinc per 100 g, while brown rice offers about 1.5 mg of iron and 2.0 mg of zinc per 100 g, and maize provides 2.7 mg of iron and 2.2 mg of zinc per 100 g, according to USDA nutrient data.[128] These levels decline significantly in refined forms due to the removal of bran and germ layers, which concentrate most micronutrients.[132] Digestibility of cereal carbohydrates is generally high, with starch hydrolysis rates exceeding 95% in refined products, enabling rapid glucose release, though whole grains exhibit lower digestibility (around 85-90%) due to intact cell walls and fiber content that resist enzymatic breakdown.[133] Cereal proteins, comprising 7-14% of dry weight, show moderate digestibility, with true ileal digestibility values of 75-90% influenced by cross-linked prolamins and disulfide bonds that hinder protease access, particularly in maize and wheat.[132] The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) for major cereals is low, typically 0.4-0.6 for wheat and maize due to lysine limitation, reflecting suboptimal utilization despite adequate apparent digestibility in refined forms.[133] Bioavailability of micronutrients in cereals is often limited by anti-nutritional factors, notably phytic acid (myo-inositol hexaphosphate), present at 0.5-2.5% of dry weight, which forms insoluble complexes with divalent cations like iron and zinc, reducing absorption.[134] Empirical studies indicate non-heme iron absorption from high-phytate cereal meals averages 1-5%, compared to 15-35% from heme sources, with phytate dose-dependently suppressing uptake in human trials.[135] Zinc bioavailability from cereals similarly ranges from 4-17%, far below the 20-40% from animal proteins, exacerbating deficiencies in populations reliant on grain-based diets.[136] Processing methods like fermentation, sprouting, or milling can degrade phytates by 20-80%, enhancing mineral bioaccessibility, as demonstrated in maize and wheat interventions.[137] B vitamins generally exhibit higher bioavailability, though niacin in maize requires alkali processing (nixtamalization) for release from bound forms.[138]Evidence-Based Health Outcomes and Dietary Roles