Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

County

View on Wikipedia

A county is a type of officially recognized geographical division within a modern country, federal state, or province. Counties are defined in diverse ways, but they are typically current or former official administrative divisions within systems of local government, and in this sense counties are similar to shires, and typically larger than municipalities. Various non-English terms can be translated as "county" or "shire" in other languages, and in English new terms with less historical connection have been invented such as "council area" and "local government district". On the other hand, in older English-speaking countries the word can still refer to traditional historical regions such as some of those which exist in England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. The term is also sometimes used for districts with specific non-governmental purposes such as courts, or land registration.

Historically the concept of a geographical administrative "county" is European (from French: comté, Latin: comitatus), and represented the territorial limits of the jurisdiction of a medieval count, or a viscount (French: vîcomte, Latin: vicecomes) supposedly standing in the place of a count. However, there were no such counts in medieval England, and when the French-speaking Normans took control of England after 1066 they transplanted the French and medieval Latin terms to describe the pre-existing Anglo Saxon shires, but they did not establish any system placing the administration of shires under the control of high-level nobles. Instead, although there were exceptions, the officers responsible for administrative functions, such as tax collection, or the mustering of soldiers, were sheriffs, theoretically assigned by the central government, and controlled directly by the monarch.

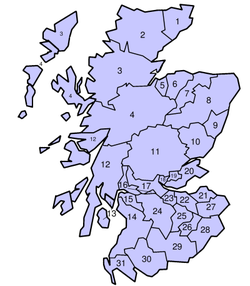

The Counties of England have evolved in several different directions, so that there is now more than one definition. The 39 "traditional", "ancient" or "historic" counties of England have on the one hand evolved into 83 metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties, which are modern administrative districts covering the whole country except London, Berkshire, and the Isles of Scilly. The historic counties are also the basis for the 48 ceremonial counties of England, which still each have lords-lieutenants and high sheriffs, who theoretically represent the monarchy in different parts of the country. In cases such as Yorkshire and Sussex, some historical counties remain as geographical regions without any administrative function. The postal counties of the United Kingdom, based upon older county definitions, were used by the Royal Mail until 1996. Scotland replaced its 34 historic counties or shires with 32 modern "council areas", some of which correspond to the old counties, or use the old names. In Wales the modern "principal areas" correspond to some extent to the old county boundaries, and they can also still be referred to as "counties" and "county boroughs". The 32 modern Irish counties were first defined after the Norman invasion, but several of these were broadly continuations with earlier divisions clan lordships (Tír Eoghain became county Tyrone, Tír Chonaill became county Donegal, west Breifne became county Leitrim and Fír Manach became modern county Fermanagh).

Notable examples of more recently-founded English-speaking administrations which have taken up the term "county" as a level of local government include the United States and Canada, where counties sometimes evolved from historic districts governed by courts or magistrates, before the countries became independent of the United Kingdom. In New Zealand there were counties historically, but these have been replaced by cities or districts. In Australian local government, the term "shire" is among the several which are typically used in local government, depending upon the state, but the term "county", which was used by the colonial administration, is mainly relevant for land registration districts (for example in Queensland lands administration). It is also used for the County Court of Victoria, which is a court covering an entire Australian state.

Africa

[edit]Kenya

[edit]Counties are the current second-level political division in Kenya. Each county has an assembly where members of the county assembly (MCAs) sit. This assembly is headed by a governor. Each county is also represented in the Senate of Kenya by a senator. Additionally, a women's representative is elected from each county to the Parliament of Kenya to represent women's interests. Counties replaced provinces as the second-level division after the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya.

Liberia

[edit]Liberia has 15 counties, each of which elects two senators to the Senate of Liberia.

Asia

[edit]China

[edit]The English word county is used to translate the Chinese term xiàn (县 or 縣). In Mainland China, governed by the People's Republic of China (PRC), counties and county-level divisions are the third level of regional/local government, coming under the provincial level and the prefectural level, and above the township level and village level.

There are 1,464 so-named "counties" out of 2,862 county-level divisions in the PRC, and the number of counties has remained more or less constant since the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220). It remains one of the oldest titles of local-level government in China and significantly predates the establishment of provinces in the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). The county government was particularly important in imperial China because this was the lowest level at which the imperial government is functionally involved, while below it the local people are managed predominantly by the gentries. The head of a county government during imperial China was the magistrate, who was often a newly ascended jinshi.

In older context, district was an older English translation of xiàn before the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). The English nomenclature county was adopted following the establishment of the ROC.

During most of the imperial era, there were no concepts like municipalities in China. All cities existed within counties, commanderies, prefectures, etc., and had no governments of their own.[a] Large cities (must be imperial capitals or seats of prefectures) could be divided and administered by two or three counties. Such counties are called 倚郭縣 (yǐguō xiàn, 'county leaning on the city walls') or 附郭縣 (fùguō xiàn, 'county attached to the city walls'). The yamen or governmental houses of these counties exist in the same city. In other words, they share one county town. In this sense, a yǐguō xiàn or fùguō xiàn is similar to a district of a city.

For example, the city of Guangzhou (seat of the eponymous prefecture, also known as Canton in the Western world) was historically divided by Nanhai County (南海縣) and Panyu County (番禺縣). When the first modern city government in China was established in Guangzhou, the urban area was separated from these two counties, with the rural areas left in the remaining parts of them. However, the county governments remained in the city for years, before moving into the respective counties. Similar processes happened in many Chinese cities.

Nowadays, most counties in mainland China, i.e. with "Xian" in their titles, are administered by prefecture-level cities and have mainly agricultural economies and rural populations.

Indonesia

[edit]Regency (kabupaten) in Indonesia is an administrative unit under a province that is equivalent to a city. A regency is headed by a regent who is directly elected by the people, and is responsible for public services such as education, health, and infrastructure. The structure of a regency includes several districts (kecamatan) which are further divided into villages or ward. Regency in Indonesia is similar to the concept of "county" in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, but with differences in cultural context and government system. Indonesia has more than 400 regencies spread across all provinces.

Iran

[edit]

The ostans (provinces) of Iran are further subdivided into counties called shahrestān (Persian: شهرستان). County consists of a city centre, a few bakhsh (Persian: بخش), and many villages around them. There are usually a few cities (Persian: شهر, shahar) and rural agglomerations (Persian: دهستان, dehestān) in each county. Rural agglomerations are a collection of a number of villages. One of the cities of the county is appointed as the capital of the county.

Each shahrestān has a government office known as farmândâri (فرمانداری), which coordinates different events and government offices. The farmândâr فرماندار, or the head of farmândâri, is the governor of the shahrestān.

Fars province has the highest number of shahrestāns, with 36, while Qom uniquely has one, being coextensive with its namesake county. Iran had 324 shahrestāns in 2005 and 443 in 2021.

Korea

[edit]County is the common English translation for the character 군 (gun or kun) that denotes the current second level political division in South Korea. In North Korea, the county is one type of municipal-level division.

Taiwan

[edit]There are currently 13 counties in the Republic of China (Taiwan). In addition, provincial cities have the same level of authority as counties. Above county, there are special municipalities (in effect) and province (suspended due to economical and political reasons).

Europe

[edit]Denmark

[edit]Denmark was divided into counties (Danish: amter) from 1662 to 2006. On 1 January 2007 the counties were replaced by five Regions. At the same time, the number of municipalities was slashed to 98.

The counties were first introduced in 1662, replacing the 49 fiefs (len) in Denmark–Norway with the same number of counties. This number does not include the subdivisions of the Duchy of Schleswig, which was only under partial Danish control. The number of counties in Denmark (excluding Norway) had dropped to around 20 by 1793. Following the reunification of South Jutland with Denmark in 1920, four counties replaced the Prussian Kreise. Aabenraa and Sønderborg County merged in 1932 and Skanderborg and Aarhus were separated in 1942. From 1942 to 1970, the number stayed at 22.[1] The number was further decreased by the 1970 Danish municipal reform, leaving 14 counties plus two cities unconnected to the county structure; Copenhagen and Frederiksberg.

In 2003, Bornholm County merged with the local five municipalities, forming the Bornholm Regional Municipality. The remaining 13 counties were abolished on 1 January 2007 where they were replaced by five new regions. In the same reform, the number of municipalities was slashed from 270 to 98 and all municipalities now belong to a region.

France

[edit]

A comté was a territory ruled by a count (comte) in medieval France. In modern France, the rough equivalent of a county as used in many English-speaking countries is a department (département). Ninety-six departments are in metropolitan France, and five are overseas departments, which are also classified as overseas regions. Departments are further subdivided into 334 arrondissements, but these have no autonomy; they are the basis of local organisation of police, fire departments and, sometimes, administration of elections.

Germany

[edit]

Each administrative district consists of an elected council and an executive, and whose duties are comparable to those of a county executive in the United States, supervising local government administration. Historically, counties in the Holy Roman Empire were called Grafschaften. The majority of German districts are "rural districts"[2] (German: Landkreise), of which there are 294 as of 2017[update]. Cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants (and smaller towns in some states) do not usually belong to a district, but take on district responsibilities themselves, similar to the concept of independent cities and there are 107 of them, bringing the total number of districts to 401.[3]

Hungary

[edit]The administrative unit of Hungary is called vármegye (between 1950 and 2022 they were called megye, historically also comitatus in Latin), which can be translated with the word county. The two names are used interchangeably ('megye' used in common parlance, and when referring to the counties of other states), just like before 1950, when the word 'megye' even appeared in legal texts. The 19 counties constitute the highest level of the administrative subdivisions of the country together with the capital city Budapest, although counties and the capital are grouped into seven statistical regions.

Counties are subdivided into districts (járás) and municipalities, the two types of which are towns (város) and villages (község), each one having their own elected mayor and council. 23 of the towns have the rights of a county although they do not form independent territorial units equal to counties.

The vármegye was also the historic administrative unit in the Kingdom of Hungary, which included areas of present-day neighbouring countries of Hungary. Its Latin name (comitatus) is the equivalent of the French comté. Actual political and administrative role of counties changed much through history. Originally they were subdivisions of the royal administration, but from the 13th century they became self-governments of the nobles and kept this character until the 19th century when in turn they became modern local governments.

Ireland

[edit]

The island of Ireland was historically divided into 32 counties, of which 26 later formed the Republic of Ireland and 6 made up Northern Ireland.

These counties are traditionally grouped into four provinces: Leinster (12 counties), Munster (6), Connacht (5) and Ulster (9). Historically, the counties of Meath and Westmeath and small parts of surrounding counties constituted the province of Mide, which was one of the "Five Fifths" of Ireland (in the Irish language the word for province, cúige, means 'a fifth': from cúig, 'five'); however, these have long since been absorbed into Leinster. In the Republic each county is administered by an elected "county council", and the old provincial divisions are merely traditional names with no political significance.

The number and boundaries of administrative counties in the Republic of Ireland were reformed in the 1990s. For example, County Dublin was divided into three: Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal, and South Dublin; the City of Dublin had existed for centuries before. The cities of Cork and Galway have been separated from the town and rural areas of their counties. The cities of Limerick and Waterford were merged with their respective counties in 2014. Thus, the Republic of Ireland now has 31 'county-level' authorities, although the borders of the original twenty-six counties are still officially in place.[4]

In Northern Ireland, the six county councils and the smaller town councils were abolished in 1973 and replaced by a single tier of local government. However, in the north as well as in the south, the traditional 32 counties and 4 provinces remain in common usage for many sporting, cultural and other purposes. County identity is heavily reinforced in the local culture by allegiances to county teams in hurling and Gaelic football. Each Gaelic Athletic Association county has its own flag/colours (and often a nickname), and county allegiances are taken quite seriously. See the counties of Ireland and the Gaelic Athletic Association.

Italy

[edit]In Italy the word county is not used; the administrative sub-division of a region is called provincia. Italian provinces are mainly named after their principal town and comprise several administrative subdivisions called comuni ('communes'). There are currently 110 provinces in Italy.

In the context of pre-modern Italy, the Italian word contado generally refers to the countryside surrounding, and controlled by, the city state. The contado provided natural resources and agricultural products to sustain the urban population. In contemporary usage, contado can refer to a metropolitan area, and in some cases large rural/suburban regions providing resources to distant cities.[5]

Lithuania

[edit]Apskritis (plural apskritys) is the Lithuanian word for county. Since 1994 Lithuania has 10 counties; before 1950 it had 20. The only purpose with the county is an office of a state governor who shall conduct law and order in the county.

Norway

[edit]Norway has been divided into 11 counties (Bokmål: fylker, Nynorsk: fylke; singular: fylke) since 2020; they previously numbered 19 following a local government reform in 1972. Until that year Bergen was a separate county, but today it is a municipality within the county of Vestland. All counties form administrative entities called county municipalities (fylkeskommuner or fylkeskommunar; singular: fylkeskommune), further subdivided into municipalities (kommuner or kommunar; singular: kommune). One county, Oslo, is not divided into municipalities, rather it is equivalent to the municipality of Oslo.

Each county has its own county council (fylkesting) whose representatives are elected every four years together with representatives to the municipal councils. The counties handle matters such as high schools and local roads, and until 1 January 2002 hospitals as well. This last responsibility was transferred to the state-run health authorities and health trusts, and there is a debate on the future of the county municipality as an administrative entity. Some people, and parties, such as the Conservative and Progress Party, call for the abolition of the county municipalities once and for all, while others, including the Labour Party, merely want to merge some of them into larger regions.

Poland

[edit]

The territorial administration of Poland since 1999 has been based on three levels of subdivision. The country is divided into voivodeships (provinces); these are further divided into powiats. The term powiat is often translated into English as county (or sometimes district). In historical contexts this may be confusing because the Polish term hrabstwo (a territorial unit administered/owned by a hrabia, count) is also literally translated as "county" and it was subordinated under powiat.

The 380 county-level entities in Poland include 314 "land counties" (powiaty ziemskie) and the 66 "city counties" (miasta na prawach powiatu or powiaty grodzkie) powiat. They are subdivisions of the 16 voivodeship, and are further subdivided into 2,479 gminas (also called commune or municipality).[6][7]

Romania

[edit]

The Romanian word for county, comitat, is not currently used for any Romanian administrative divisions. Romania is divided into a total of 41 counties (Romanian: județe), which along with the municipality of Bucharest, constitute the official administrative divisions of Romania. They represent the country's NUTS-3 (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics – Level 3) statistical subdivisions within the European Union and each of them serves as the local level of government within its borders. Most counties are named after a major river, while some are named after notable cities within them, such as the county seat.

Sweden

[edit]

The Swedish division into counties, län, which literally means 'fief', was established in 1634, and was based on an earlier division into provinces; Sweden is divided into 21 counties and 290 municipalities (kommuner). At the county level there is a county administrative board led by a governor appointed by the central government of Sweden, as well as an elected county council that handles a separate set of issues, notably hospitals and public transportation for the municipalities within its borders. The counties and their expanse have changed several times, most recently in 1998.

Every county council corresponds to a county with a number of municipalities per county. County councils and municipalities have different roles and separate responsibilities relating to local government. Health care, public transport and certain cultural institutions are administered by county councils while general education, public water utilities, garbage disposal, elderly care and rescue services are administered by the municipalities. Gotland is a special case of being a county council with only one municipality and the functions of county council and municipality are performed by the same organisation.[8]

Ukraine

[edit]In Ukraine the county (Ukrainian: повіт, romanized: povit) was introduced in Ukrainian territories under Poland in the second half of the 14th century, and in the eighteenth century under the Russian Empire in the Cossack Hetmanate, Sloboda Ukraine, Southern Ukraine, and Right-Bank Ukraine.[9] In 1913 there were 126 counties in Ukrainian-inhabited territories of the Russian Empire.[9] Under the Austrian Empire in 1914 there were 59 counties in Ukrainian-inhabited Galicia, 34 in Transcarpathia, and 10 in Bukovina.[9] Counties were retained by the independent Ukrainian People's Republic of 1917–1921, and in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Romania until the Soviet annexations at the start of World War II. 99 counties formed the Ukrainian SSR in 1919, where they were abolished in 1923–25 in favour of 53 okruhas (in turn replaced by oblasts in 1930–32), although they existed in the Zakarpattia Oblast until 1953.[9][10]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom is divided into a number of metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties. There are also ceremonial counties which group small non-metropolitan counties into geographical areas broadly based on the historic counties of England. In 1974, the metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties replaced the system of administrative counties and county boroughs which was introduced in 1889. The counties generally belong to level 3 of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS 3).

In 1965 and 1974–1975, major reorganisations of local government in England and Wales created several new administrative counties such as Hereford and Worcester (abolished again in 1998 and reverted, with some transfers of territory, to the two separate historic counties of Herefordshire and Worcestershire) and also created several new metropolitan counties based on large urban areas as a single administrative unit. In Scotland, county-level local government was replaced by larger regions, which lasted until 1996. Modern local government in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and a large part of England is trending towards smaller unitary authorities: a system similar to that proposed in the 1960s by the Redcliffe-Maud Report for most of Britain.

The name "county" was introduced by the Normans, and was derived from a Norman term for an area administered by a Count (lord). These Norman "counties" were simply the Saxon shires, and kept their Saxon names. Several traditional counties, including Essex, Sussex and Kent, predate the unification of England by Alfred the Great, and were originally more or less independent kingdoms (although the most important Saxon Kingdom on the island of Britain, Alfred's own Wessex, no longer survives in any form).

England

[edit]

In England, in the Anglo-Saxon period, shires were established as areas used for the raising of taxes, and usually had a fortified town at their centre. This became known as the shire town or later the county town. In many cases, the shires were named after their shire town (for example Bedfordshire), but there are several exceptions, such as Cumberland, Norfolk and Suffolk. In several other cases, such as Buckinghamshire, the modern county town is different from the town after which the shire is named. (See Toponymical list of counties of the United Kingdom)

Most non-metropolitan counties in England are run by county councils and are divided into non-metropolitan districts, each with its own council. Local authorities in the UK are usually responsible for education, emergency services, planning, transport, social services, and a number of other functions.

Until 1974, the county boundaries of England changed little over time. In the medieval period, a number of important cities were granted the status of counties in their own right, such as London, Bristol and Coventry, and numerous small exclaves such as Islandshire were created. In 1844, most of these exclaves were transferred to their surrounding counties.

Northern Ireland

[edit]

In Northern Ireland, the six county councils, if not their counties, were abolished in 1973 and replaced by 26 local government districts. The traditional six counties remain in common everyday use for many cultural and other purposes.

Scotland and Wales

[edit]

The thirteen historic counties of Wales were fixed by statute in 1539 (although counties such as Pembrokeshire date from 1138) and most of the shires of Scotland are of at least this age. The Welsh word for county is sir which is derived from the English 'shire'.[11] The word is officially used to signify counties in Wales.[12] In the Gaelic form, Scottish traditional county names are generally distinguished by the designation siorramachd—literally "sheriffdom", e.g. Siorramachd Earra-ghaidheal (Argyllshire). This term corresponds to the jurisdiction of the sheriff in the Scottish legal system.

North America

[edit]Canada

[edit]Alberta

[edit]A county in Alberta used to be a type of designation in a single-tier municipal system; but this was nominally changed to "municipal district" under the Municipal Government Act, when the County Act was repealed in the mid-1990s. However, at the time the new "municipal districts" were also permitted to retain the usage of county in their official names.[13]

As a result, in Alberta, the term county is synonymous with the term municipal district – it is not its own incorporated municipal status that is different from that of a municipal district. As such, Alberta Municipal Affairs provides municipal districts with the opportunity to change to a county in their official names, but some have chosen to hold out with the municipal district title. The vast majority of "municipal districts" in Alberta are branded as counties.

British Columbia

[edit]British Columbia has counties for the purposes of its justice system but otherwise they hold no governmental function. For the provision of all other governmental services, the province is divided into regional districts that form the upper tier, which are further subdivided into local municipalities that are partly autonomous, and unincorporated electoral areas that are governed directly by the regional districts.

Manitoba

[edit]The province of Manitoba was divided into counties; however, these counties were abolished in 1890. Manitoba is divided into rural municipalities, which do not overlap with urban municipalities.

New Brunswick

[edit]The counties of New Brunswick were upper-tier governance units until the municipal reform of 1967; they were also used as electoral districts until 1973. They remain in use as census divisions by Statistics Canada and by locals as geographic identifiers. The Territorial Division Act defining them remains in effect; their subdivisions are called parishes; their government centres are called shiretowns.

Newfoundland and Labrador

[edit]Newfoundland and Labrador does not have any second-level administrative subdivision between the provincial government and its municipalities.

Northwest Territories

[edit]The Northwest Territories are divided into regions; however, these regions only serve to streamline the delivery of territorial governmental services, and have no government of their own.

Nova Scotia

[edit]Nova Scotia formerly had a two-tier system of local government in which counties were upper-tier municipalities.

Nunavut

[edit]Nunavut is divided into regions; however, these regions only serve to streamline the delivery of territorial governmental services, and have no government of their own.

Ontario

[edit]Ontario has a two-tier system of local government in which counties are upper-tier municipalities.

The primary administrative division of southern Ontario is its 22 counties, which are upper-tier local governments providing limited municipal services to rural and moderately dense areas—within them, there are a variety of lower-tier towns, cities, villages, etc. that provide most municipal services. This contrasts with northern Ontario's 10 districts, which are geographic divisions but not local governments—although some towns, etc. are within them that are local governments, the low population densities and much larger area have significant impacts on how government is organized and operates. In both northern and southern Ontario, urban densities in cities are one of two other local structures: regional municipalities (restructured former counties which are also upper-tier) or single-tier municipalities.

Prince Edward Island

[edit]The counties of Prince Edward Island are historical and have no governments of their own today. However, they remain used as census divisions by Statistics Canada, and by locals as geographic identifiers.

Quebec

[edit]Quebec has a two-tier system of local government in which counties are upper-tier municipalities. Quebec's counties are more properly called "regional county municipalities" (municipalités régionales de comté). The province's former counties proper were supplanted in the early 1980s.

Saskatchewan

[edit]Saskatchewan is divided into rural and urban municipalities, which do not overlap. Saskatchewan does not have any second-level administrative subdivision between the provincial government and the municipalities.

Yukon

[edit]Yukon does not have any second-level administrative subdivision between the territorial government and its municipalities.

Jamaica

[edit]Jamaica is divided into 14 parishes which are grouped together into three historic counties: Cornwall, Middlesex, and Surrey.

United States

[edit]

Counties in U.S. states are administrative or political subdivisions of the state in which their boundaries are drawn. In addition, the United States Census Bureau uses the term "county equivalent" to describe places that are comparable to counties, but called by different names.[14]

Forty-seven of the 50 U.S. states use the term "county", while Alaska, Connecticut, and Louisiana use the terms "borough", "planning region", and "parish", respectively, for analogous jurisdictions. A consolidated city-county, such as the City and County of San Francisco, is formed when a city and county merge into one unified jurisdiction. Conversely, independent cities, including Baltimore, St. Louis, Carson City, and all cities in Virginia, legally belong to no county, i.e. no county even nominally exists in those places compared to a consolidated city-county where a county does legally exist in some form. Washington, D.C., is known as a federal city because it is outside the jurisdiction of any state; the U.S. Census Bureau treats it as a single county equivalent.[14]

The specific governmental powers of counties vary widely between the states. They are generally the intermediate tier of state government, between the statewide tier and the immediately local government tier (typically a city, town/borough, or village/township). Some of the governmental functions that a county may offer include judiciary, county prisons, land registration, enforcement of building codes, and federally mandated services programs. Depending on the individual state, counties or their equivalents may be administratively subdivided into townships, boroughs or boros, or towns (in the New England states, New York, and Wisconsin).

New York City is a special case where the city is made up of five boroughs, each of which is territorially coterminous with a county, though not always with an identical name. The Bronx is Bronx County, Brooklyn is Kings County, Manhattan is New York County, Queens is Queens County, and Staten Island is Richmond County. In the context of city government, the boroughs are subdivisions of the city but are still called "county" where county function is involved, e.g., "New York County Courthouse".

County governments in Rhode Island and Connecticut have been completely abolished but the entities remain for administrative and statistical purposes in Rhode Island, while Connecticut has replaced them with planning regions served by councils of municipal governments. Alaska's 323,440-square-mile (837,700 km2) Unorganized Borough also has no county equivalent government, but the U.S. Census Bureau further divides it into statistical county equivalent subdivisions called census areas.[14] Massachusetts eliminated county governments in 8 of its 14 counties.[15][16]

Today, 3,142 counties and county equivalents carve up the United States, ranging in number from 3 for Delaware to 254 for Texas. The areas of each county also vary widely between the states. For example, the territorially medium-sized state of Pennsylvania has 67 counties delineated in geographically convenient ways.[17] By way of contrast, Massachusetts, with far less territory, has massively sized counties in comparison even to Pennsylvania's largest,[b] yet each organizes their judicial and incarceration officials similarly.

Most counties have a county seat: a city, town, or other named place where its administrative functions are centered. Some New England states use the term shire town to mean "county seat". A handful of counties like Harrison County, Mississippi have two or more county seats, usually located on opposite sides of the county, dating back from the days when travel was difficult. In Virginia, where all cities are independent, some double as county seats despite not being part of a county. Notable examples include the independent City of Fairfax serving as the seat of Fairfax County and Salem serving as the county seat of Roanoke County.

Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]In the eastern states of Australia, counties are used in the administration of land titles. They do not generally correspond to a level of government, but are used in the identification of parcels of land.

The local communities in Australia that share the same post code are usually referred to as suburbs or localities. Several neighboring suburbs are often serviced by the same local government known as a council, whose jurisdiction is officially known as the local government area (LGA). An LGA functions basically the same way as a county of other countries, although it is called instead as "city", "municipality", "shire", "borough", "town", "district" or simple "councils" depending on the state/territory and subregion. It performs municipal services and regulates permits for land uses, but lacks any legislative or law enforcement powers.

New Zealand

[edit]After New Zealand abolished its provinces in 1876, a system of counties similar to other countries' systems was instituted, lasting until 1989. They had chairmen, not mayors as boroughs and cities had; many legislative provisions (such as burial and land subdivision control) were different for the counties.

During the second half of the 20th century, many counties received overflow population from nearby cities. The result was often a merger of the two into a district (e.g. Rotorua) or a change of name to either district (e.g. Waimairi) or city (e.g. Manukau City).

The Local Government Act 1974 began the process of bringing urban, mixed, and rural councils into the same legislative framework. Substantial reorganisations under that Act resulted in the 1989 shake-up, which covered the country in (non-overlapping) cities and districts and abolished all the counties except for the Chatham Islands County, which survived under that name for a further 6 years but then became a "Territory" under the "Chatham Islands Council".

South America

[edit]Argentina

[edit]Provinces in Argentina are divided into departments (Spanish: departamentos), except in the Buenos Aires Province, where they are called partidos. The Autonomous City of Buenos Aires is divided into communes (comunas).

Brazil

[edit]States in Brazil were divided into microregions (Portuguese: microrregiões) before they were replaced by "immediate geographic regions" in 2017.

Notes

[edit]- ^ There were exceptions in the Jīn and Yuan dynasties, when cities were separated from counties and independently administered by institutions like 録事司 (lù shi sī) and 司候司 (sī hòu sī).

- ^ e.g. Westmoreland, Washington in western Pennsylvania.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Amternes administration 1660–1970 (in Danish)". Dansk Center for Byhistorie. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ "Country Compendium, A companion to the English Style Guide" (PDF). European Commission Directorate-General for Translation (EC DGT). February 2017. pp. 50–51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Kreisfreie Städte und Landkreise nach Fläche und Bevölkerung auf Grundlage des ZENSUS 2011 und Bevölkerungsdichte – Gebietsstand: 31.12.2015" (XLS) (in German). Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland. July 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Areas". Ordnance Survey Ireland. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- ^ Guenzi, Alberto (2016). Guilds, Markets and Work Regulations in Italy, 16th–19th Centuries. Routledge. ISBN 9781351931960.

- ^ ideo.pl, ideo- (27 April 2019). "Gminy wiejskie chcą lepszej ochrony swych granic". Prawo.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Population. Size and structure and vital statistics in Poland by territorial division in 2017. As of December, 31" (PDF) (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Central Statistical Office). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Municipalities, county councils and regions Archived 22 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine; official translation of the Local Government Act Archived 20 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine (Kommunallagen);About Stockholm County Council Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d "County". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Okruha". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru". geiriadur.ac.uk.

- ^ "Carmarthenshire County Council Website : Gwefan Cyngor Sir Gaerfyrddin". Carmarthenshire.gov.wales. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Province of Alberta. "Transitional Provisions, Consequential Amendments, Repeal and Commencement (Municipal Government Act)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ a b c "County and equivalent entity". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "America's County Governments: A SHORT PRIMER ON OUR HISTORY, DEFINITIONS, STRUCTURES AND AUTHORITIES" (PDF). www.naco.org.

- ^ "Substantial Changes to Counties and County Equivalent Entities: 1970-Present".

- ^ "County Government". Citizen's Guide to Pennsylvania Local Government: 8 of 56. 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

External links

[edit]County

View on GrokipediaTerminology and Etymology

Linguistic Origins

The English word "county" derives from Middle English counte, first attested around 1319–1320, borrowed from Anglo-French counte or counté.[5][1] This in turn stems from Old French conté (modern French comté), signifying the domain or jurisdiction governed by a comte (count).[3][1] The Old French term traces to Late Latin comitatus, denoting the office, dignity, or territorial extent associated with a comes (count or companion).[1][6] The root comes (nominative comes, accusative comitem), from which comitatus is formed, originally signified a companion, attendant, or member of a retinue in Classical Latin, evolving by Late Antiquity to denote imperial or royal officials responsible for provincial administration.[6][7] This semantic shift reflected the comes' role as a leader of followers (comites), extending to the governed area under their authority in Frankish and Carolingian contexts.[6] In linguistic usage, comitatus parallels Germanic concepts of lordship and followers, as seen in Old English comitatus (borrowed directly) and its influence on administrative terminology post-Norman Conquest, where it supplanted or coexisted with native terms like scīr (shire) for territorial divisions.[6] The word's adoption in English thus preserved a continental feudal connotation of a noble's territorial oversight, distinct from purely geographic descriptors.[5]Modern Definitions and Equivalents

In the United States, a county functions as the primary legal and administrative subdivision of a state, encompassing geographic areas bounded by county lines and serving as the basis for U.S. Census Bureau data release, with responsibilities including local governance, public safety, and record-keeping.[2] There are 3,144 counties or county-equivalent entities across the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories as of the 2020 Census, though functions vary by state, with some rural areas delegating powers to townships or cities.[8] In the United Kingdom, particularly England, a county denotes a territorial division for administrative purposes, where county councils oversee county-wide services such as education, social care, highways, and planning across non-metropolitan areas, distinct from unitary authorities or metropolitan boroughs.[9] As of 2023, England maintains 26 administrative counties alongside ceremonial counties used for cultural and lieutenancy roles, reflecting a layered system post-1974 local government reforms.[9] Equivalents abroad often mirror county-level administration but adopt distinct nomenclature and structures adapted to national systems. In France, the département—96 mainland units plus overseas equivalents—performs analogous mid-tier functions like public works, welfare, and secondary education under prefect oversight, established post-1789 Revolution to decentralize from provinces.[10] Germany's Landkreis (rural district) or kreisfreie Stadt (district-free city) serves as the county parallel, numbering 294 rural districts and 107 urban ones as of 2014, handling waste management, building permits, and social services below the 16 Länder states.[11] In Poland, the powiat acts as the second-level division equivalent to a county, with 308 rural powiats and 65 urban powiats with powiat status as of 2023, managing health, roads, and environmental protection subordinate to 16 voivodeships.[12] Similar subdivisions appear globally: Ireland retains 26 traditional counties for local authority boundaries and elections; China's xian (county) totals 1,464 units as primary rural administrations under provinces; and Kenya's 47 counties, devolved since the 2010 Constitution, manage devolved powers like agriculture and health akin to U.S. models.[12] These equivalents prioritize fiscal decentralization and service delivery but differ in autonomy, with civil-law systems often retaining stronger central oversight compared to common-law county traditions.[13]Historical Development

Medieval European Roots

The concept of the county as an administrative division emerged in early medieval Europe from the Latin term comitatus, denoting the jurisdiction and entourage of a comes (count), originally a companion or high-ranking official in the Roman imperial court who evolved into a local governor under Germanic kingdoms.[1] This structure gained prominence during the Carolingian dynasty, particularly under Charlemagne (r. 768–814), who reorganized the Frankish realm into counties as the primary units of royal administration, often aligning with pre-existing Roman pagi or tribal districts.[14] In the Carolingian system, counts were appointed by the king from the royal comitatus—the itinerant court entourage—and tasked with enforcing royal capitularies, collecting taxes, mobilizing military levies, and presiding over local courts (mallus).[14] By the late 8th century, these officials held hereditary or semi-hereditary authority over territories varying in size from roughly 300 to 1,000 square kilometers, with larger counties in peripheral regions like Aquitaine or Bavaria subdivided into centenae for finer control.[15] The count's role emphasized delegated royal power rather than independent feudal lordship, though by the 9th century under Louis the Pious (r. 814–840), weakening central oversight allowed some counts to consolidate comitatus into appanages, foreshadowing the rise of principalities.[14] This Carolingian model disseminated across Europe through conquest and imitation, influencing regions like the Low Countries, where comitatus denoted both the count's office and the governed territory by the 10th century, and eastern Francia, where royal diplomas explicitly granted comitatus as administrative counties distinct from ecclesiastical or proprietary lands.[15] In Italy and Iberia, post-Carolingian counties adapted the framework amid Reconquista efforts, with counts like those of Toulouse exercising judicial and fiscal prerogatives over 500–2,000 square kilometers by the 11th century.[16] Hereditary tenure increasingly prevailed after the 843 Treaty of Verdun fragmented the empire, transforming counties from revocable royal delegations into durable territorial units that underpinned feudal hierarchies while retaining administrative functions like muster and inquest.[14]Establishment in England and the British Isles

The county system in England traces its origins to the Anglo-Saxon shire, an administrative division that emerged in the Kingdom of Wessex during the early medieval period, primarily for taxation, military mustering, and local justice.[17] The Old English term scīr, denoting a district under official care, first appeared in Wessex with the onset of Anglo-Saxon settlement around the fifth to sixth centuries, though systematic organization intensified by the eighth century.[18] Shires were governed by ealdormen or reeves, subdivided into hundreds for finer control, and often centered on fortified burhs established or reinforced under Alfred the Great (r. 871–899) to counter Viking incursions.[19] By the tenth century, following unification under Edward the Elder and Athelstan, the system encompassed most of England, with approximately thirty-nine shires recorded by the Domesday Book of 1086.[20] Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the French-derived term "county" (comté) was overlaid on the shire structure, equating the ealdorman with the Norman comes (earl), while preserving the underlying framework for royal revenue and courts.[17] Shire courts met twice yearly, handling civil and criminal matters, with the sheriff (shire-reeve) appointed by the king to enforce fiscal and judicial duties.[21] In Wales, counties developed later under English influence, with initial administrative circuits established after Edward I's conquest by 1284 via the Statute of Rhuddlan, dividing conquered territories into four regions for governance.[22] The definitive thirteen historic counties were formalized by the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–1542, which legally annexed Wales to England, imposing shire-based administration aligned with English models for uniformity in law, taxation, and representation.[23] Scotland's counties originated as sheriffdoms in the twelfth century, introduced by David I (r. 1124–1153) to centralize royal authority, drawing from Anglo-Saxon precedents in lowland areas influenced by English settlement.[22] Alexander I (r. 1107–1124) initiated the first shires around royal burghs for judicial oversight, expanding to about thirty-three by the eighteenth century, each under a hereditary sheriff managing courts and revenues.[24] In Ireland, counties were imposed by Anglo-Norman invaders starting in the late twelfth century, with King John designating twelve initial counties in 1210—Dublin, Kildare, Meath, Louth, Carlow, Kilkenny, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Limerick, Kerry, and Tipperary—to administer English-held pale and lordships.[25] Tudor expansions in the sixteenth century added counties like Longford (1569) and Fermanagh (1584), completing the thirty-two counties by 1607, standardizing boundaries for plantation policies, taxation, and military control.[26]Spread Through Colonization and Adoption Elsewhere

The English shire system, adapted as counties, was transplanted to British North American colonies during the 17th century to facilitate local administration, judicial functions, and land management akin to the homeland model. In Virginia, the first colonial county government emerged in 1634 with the establishment of James City Shire (later renamed James City County), followed rapidly by seven others, enabling sheriffs to enforce laws, collect taxes, and oversee militias in sparsely settled frontier areas.[27] By the mid-17th century, New England colonies like Massachusetts Bay adopted counties in 1643 for similar purposes, dividing territories into units such as Essex and Middlesex to handle probate, poor relief, and local courts, reflecting the practical need for decentralized governance in expansive new territories.[28] This framework persisted and proliferated after American independence in 1776, as the new states retained counties as primary subdivisions for taxation, elections, and public services, expanding to over 2,000 by 1900 through westward settlement and territorial organization.[29] Today, the United States maintains 3,143 counties and equivalents (including 64 parish-equivalents in Louisiana and 19 consolidated city-counties), serving as the principal units for rural and suburban governance, with responsibilities devolved from states but varying widely in size—from San Bernardino County, California, at 20,105 square miles, to New York County at 23 square miles. In Canada, counties were introduced in the late 18th century under British rule, first in Nova Scotia (1785) and New Brunswick for land registry and courts, then in Upper Canada (Ontario) via the 1792 Constitutional Act, which created 19 initial counties like York and Wentworth to mirror English judicial districts and support Loyalist settlement.[30] Quebec followed with county divisions post-1791, but the system waned in the 19th-20th centuries as provinces shifted to townships and municipalities; by the mid-20th century, most Canadian counties had been restructured or abolished outside eastern Ontario, where 16 united counties remain for planning and services.[31] Adoption beyond North America was limited and often modified. In Australia and New Zealand, British settlers employed "shire" terminology for local councils from the 19th century—such as New South Wales' first shires in 1843—but these functioned as municipal bodies rather than intermediate administrative tiers equivalent to English counties, prioritizing urban-rural divides over shire-wide governance. In other empire territories like India and African colonies, the county model did not take root; instead, pre-existing Mughal districts in India or tribal divisions in Africa were adapted into provinces or collectorates under direct Crown rule, bypassing shire-style decentralization due to denser populations and centralized imperial control. This selective spread underscores the system's suitability for settler societies with dispersed agrarian economies, where local autonomy aided colonization but proved less adaptable to high-density or indigenous-heavy contexts.Administrative Characteristics

Core Functions and Powers

Counties function as intermediate administrative divisions between national or state governments and municipalities, wielding powers primarily delegated from higher authorities to deliver localized public services and enforce regulations. These powers encompass legislative, executive, and sometimes limited judicial roles, enabling counties to adopt ordinances on matters like zoning and public health, subject to overriding statutes from superior jurisdictions.[32][33] Executive authority is typically exercised by elected councils or commissions, which appoint administrators to oversee operations, budget execution, and policy implementation within defined boundaries.[34] Among core functions, counties universally prioritize infrastructure maintenance, including roads, bridges, and transportation networks, often funding these through property taxes and grants.[35] Public safety constitutes another foundational responsibility, encompassing fire protection, emergency services, and in some systems, sheriff-led law enforcement for unincorporated areas.[36] Social services, such as welfare administration, child protection, and elderly care, form a significant remit, with counties acting as conduits for state-mandated programs.[37] Land use planning and environmental management further define county powers, involving development approvals, waste disposal, and sanitary services to balance growth with resource conservation.[38] In jurisdictions like England, counties oversee education provision, libraries, and trading standards, while in Ireland, they coordinate housing, water supply, and regional economic initiatives.[38][39] Fiscal powers include property assessment, tax collection, and budgeting, though constrained by legal caps and audits to prevent overreach.[34] These roles adapt to national contexts—for example, French départements emphasize secondary education and social assistance, whereas German Landkreise focus on youth services and inter-municipal coordination—ensuring counties address subnational needs without supplanting central authority.[40][37]Variations in Governance and Autonomy

In federal systems like the United States, counties typically feature elected governing bodies, such as boards of supervisors or commissions, which exercise considerable autonomy over local taxation, law enforcement, land use, and infrastructure, though this varies by state under frameworks like home rule charters that permit broader ordinance-making powers or Dillon's Rule that restricts authority to explicitly granted functions.[32][41] The three predominant structural forms—county commission (combining legislative and executive roles), council-administrator (with a professional manager), and council-elected executive—allow for tailored responses to local needs, with counties raising revenue through property taxes averaging higher autonomy than in many OECD peers.[42] In unitary states such as the United Kingdom, shire counties are administered by elected county councils with defined statutory powers over strategic services including education, highways, and social care, coordinated in a two-tier system with lower-tier districts handling housing and waste; however, these councils lack constitutional protection for autonomy, relying on parliamentary acts like the Local Government Act 1972 for authority, resulting in less fiscal independence and vulnerability to central reforms.[9][43] Continental European equivalents exhibit further centralization: France's 101 départements, governed by elected departmental councils, primarily implement national policies on welfare, roads, and secondary education but operate with low decentralization, as local authorities account for only 20% of public expenditures amid heavy reliance on state transfers and oversight.[44] In Germany, the 294 rural Landkreise and independent cities function as intermediate self-governing units under federalism, with elected assemblies and district administrators managing devolved tasks like environmental protection and emergency services, safeguarded by Article 28 of the Basic Law yet subordinate to state (Land) supervision.[37] These differences stem from constitutional designs, with federal arrangements fostering greater local initiative and unitary ones prioritizing uniformity, influencing efficiency in service provision and responsiveness to regional disparities.[45]Legal and Fiscal Frameworks

Counties derive their legal existence and authority from statutes or constitutions at the national or subnational level, functioning as intermediate administrative units between central governments and municipalities. In federal systems such as the United States, counties are statutory creations of state legislatures, with powers explicitly enumerated or implied under doctrines like Dillon's Rule—which limits authority to expressly granted functions—or home rule provisions that permit self-governance via charter, as seen in states like California and New York where counties handle zoning, public health, and elections independently of state preemption unless overridden.[32][46] In unitary systems, such as those in the United Kingdom, counties were redefined under the Local Government Act 1972, establishing non-metropolitan county councils with delegated powers for strategic services like highways and social care, though subsequent reforms like the Local Government Act 1985 abolished some upper-tier councils, redistributing duties to districts or unitary authorities.[9] Legal autonomy varies significantly by jurisdiction: U.S. counties often operate under commission or council-elected executive forms, enacting ordinances enforceable as local law, subject to state judicial review, while Irish counties, established via the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, possess corporatist status for service delivery but limited policymaking, with chief executives—appointed by the central government—exercising veto power over council decisions on planning and procurement to ensure fiscal prudence.[34][47] This contrasts with more centralized models, where counties like those in Poland or Romania serve primarily as electoral and judicial districts with minimal self-rule, their boundaries adjusted by national decree for efficiency rather than local input.[48] Fiscal frameworks emphasize balanced budgeting tied to mandated expenditures, with revenues sourced from property levies, user fees, and grants. In the U.S., counties generate about 40% of revenue from property taxes assessed locally, allocating funds to sheriff services, jails, and roads via annual budgets approved by elected boards, often constrained by state-imposed tax caps like California's Proposition 13 (1978), which limits reassessments to curb revenue growth.[32] Irish counties rely heavily on central allocations—comprising over 70% of income—plus commercial rates on businesses, prohibiting direct income or sales taxes, while borrowing requires ministerial approval to align with national debt targets under the Stability and Growth Pact.[49] English counties fund operations through council tax (a banded property charge) and revenue support grants, with multi-year medium-term financial plans mandated since 2011 to project deficits and enforce austerity measures post-2008 recession, reflecting unitary oversight that caps precept increases via referendums for rises exceeding 5%.[9] Intergovernmental fiscal relations often involve equalization mechanisms to mitigate disparities; for instance, U.S. states redistribute via formulas based on need, while EU-member counties in Ireland or Poland access cohesion funds tied to GDP per capita, conditional on compliance with procurement directives.[32] Legal challenges to fiscal authority, such as lawsuits over tax assessments or grant withholding, underscore counties' subordinate status, with courts upholding state supremacy in revenue-sharing disputes, as in U.S. cases affirming that counties lack inherent taxing power absent delegation.[46] These frameworks prioritize accountability through audits—annual in the U.S. under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)—and transparency mandates, yet persistent underfunding pressures reveal tensions between local priorities and central mandates.[34]Usage by Continent

Europe

Denmark

Denmark's counties, known in Danish as amter, served as intermediate administrative divisions between the national government and municipalities from the 17th century until their abolition on January 1, 2007.[50] Established following the absolute monarchy in 1662, when Denmark was reorganized into 48 amter from earlier len (fiefs), these units primarily handled regional governance, including infrastructure, education, and health services.[50] By 1793, the number was reduced to 24 amter through further consolidation, reflecting efforts to streamline administration amid growing centralization.[51] A major reform on April 1, 1970, restructured Denmark into 14 counties (plus Copenhagen and Frederiksberg as independent municipalities with county-like functions), reducing the previous 25 amter to enhance efficiency in service delivery.[52] These counties managed key responsibilities such as secondary education, hospitals, public transport, and environmental regulation, with each led by an amtsborgmester (county mayor) elected by the county council.[53] For instance, counties like Aarhus and Odense coordinated regional planning and financed non-municipal welfare services, operating under a framework where they could not levy income taxes but received state grants and user fees.[52] The 2007 municipal reform dissolved the counties, merging them into five larger regions—Capital Region of Denmark, Central Denmark Region, North Denmark Region, Region Zealand, and Region of Southern Denmark—to cut administrative costs and improve healthcare coordination amid an aging population.[52] This shift transferred most county powers to the 98 municipalities (up from 271), while regions focus narrowly on hospitals, psychiatry, and emergency services without taxing authority or full legislative powers.[54] Unlike historical amter, which balanced local autonomy with national oversight, the regions emphasize specialized tasks, funded primarily by block grants from the central government, reflecting a trend toward municipal centralization rather than intermediate layers.[55] Historically, amter boundaries often aligned with cultural and geographic divisions, such as Jutland's rural counties versus Zealand's urban ones, influencing local identities and policy implementation.[50] Post-abolition, the legacy persists in statistical reporting and cultural references, but administratively, Denmark operates as a unitary state with decentralized municipal governance, avoiding the federal-like autonomy seen in other European counties.[56]France

The départements constitute France's primary intermediate administrative divisions, analogous in function to counties by bridging national or regional governance with municipal levels through management of local services and infrastructure.[57] Created on 26 March 1790 by the National Constituent Assembly during the French Revolution, they replaced the patchwork of historic provinces to impose uniform administration, limit feudal influences, and ensure each unit was compact enough for efficient oversight—typically spanning a diameter traversable in a day's travel by horse.[58] This restructuring divided metropolitan France into 83 initial départements, later adjusted to 96 including Corsica's subdivision into Haute-Corse (2A) and Corse-du-Sud (2B) in 1975, with five overseas départements—Guadeloupe (971), Martinique (972), Guyane (973), Réunion (974), and Mayotte (976, elevated from collectivity status in 2011)—bringing the total to 101 as of 2025.[59][58] Governance of each département combines elected local authority with central oversight: an elected conseil départemental of 34 to 70 members, chosen via cantonal elections every six years since 2015 reforms pairing councilors by gender parity, elects a president to lead deliberations and execute decisions.[60] The council holds fiscal powers, levying taxes like the taxe foncière on property and allocating budgets for expenditures exceeding €1 billion annually per département on average.[57] A préfet, appointed by the Minister of the Interior, represents the national government, supervises legality of council acts, coordinates emergency responses, and maintains public order through affiliated services.[60] Subdivisions include arrondissements for prefectural administration and cantons for electoral purposes, while further granularity occurs at the communal level with over 35,000 communes.[61] Core functions, expanded by 1982 decentralization laws under President François Mitterrand, encompass social assistance (e.g., family allowances and elderly care, comprising over 50% of budgets), maintenance of collèges (junior high schools), departmental roads (totaling 400,000 km nationwide), fire and rescue services, and environmental protections like waste management.[57] These responsibilities position départements as key providers of welfare and infrastructure, though their autonomy remains constrained compared to more federal systems, with national laws overriding local ones and funding partly derived from state transfers.[57] Reforms in 2015 consolidated regions from 22 to 13 metropolitan ones, elevating regional councils' roles in economic development while preserving départements' social mandates to avoid overlap.[62] Overseas départements mirror metropolitan structures but adapt to insular or tropical contexts, such as enhanced roles in tourism promotion or disaster resilience; for instance, Réunion manages volcanic risk mitigation alongside standard duties.[59] Population varies widely, from Paris's dense Île-de-France départements exceeding 1 million residents to sparsely populated Creuse at under 120,000, influencing service scales and fiscal capacities.[61] Despite centralization tendencies, départements embody France's unitary republican framework, prioritizing equity across territories over parochial autonomy.[57]Germany

In Germany, the administrative divisions most analogous to counties in other countries are the Kreise, encompassing rural districts (Landkreise) and district-free cities (kreisfreie Städte). These units function as intermediate layers between the 16 federal states (Bundesländer) and the approximately 10,000 municipalities (Gemeinden), handling tasks too large for individual municipalities but below state-level responsibilities. The three city-states—Berlin, Hamburg, and Bremen—operate without Kreise, managing affairs directly at the state-municipal level. As of 2024, there are 294 Landkreise and 107 kreisfreie Städte, forming a total of 401 Kreise.[63] The contemporary Kreis system emerged from post-World War II reconstructions, building on historical precedents like medieval counties (Grafschaften) but standardized through federal and state laws. Major territorial reforms occurred between 1967 and 1979, particularly in western states, consolidating over 400 smaller districts into fewer, larger entities to enhance efficiency in service delivery and reduce administrative overlap; for instance, North Rhine-Westphalia reduced its districts from 121 to 31 by 1975. Eastern states adopted similar structures after reunification in 1990, with further adjustments in the 1990s to align with western models.[64] Kreise bear responsibilities including the operation of secondary schools (e.g., Gymnasien and Realschulen), hospitals, waste disposal facilities, and maintenance of county roads (Kreisstraßen). They also oversee social welfare services, such as youth protection and elderly care, and environmental tasks like water management. Governance occurs via an elected district council (Kreistag), which appoints a full-time district administrator (Landrat or Oberbürgermeister in urban districts) responsible for executive functions; elections for the Kreistag align with municipal cycles, typically every five years. Kreisfreie Städte, often larger cities like Munich or Stuttgart, additionally perform extensive municipal duties, blurring lines between district and city administration. Funding derives primarily from local taxes (e.g., property and trade taxes), state grants, and fees, with Kreise enjoying self-governance under the federal Grundgesetz (Basic Law) but subject to state oversight.[65][66] Variations exist across states; for example, in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, Kreise have enumerated statutory duties, while in others like Schleswig-Holstein, responsibilities are more flexibly defined by state law. Some states, such as Hesse, employ Landkreise alongside regional associations for specific functions like water supply. Despite reforms, debates persist on further amalgamation to address demographic declines in rural Landkreise, where populations have shrunk by up to 10% in some areas since 2000 due to urbanization.[67]Hungary

Hungary is administratively subdivided into 19 counties, known as megyék or vármegyék, alongside the capital Budapest, which possesses equivalent status and is not part of any county.[68][69] This structure supports regional coordination within a unitary state framework, with counties serving as intermediate levels between central government and over 3,000 municipalities.[70] The origins of the county system trace to the early Kingdom of Hungary around 1000 AD, when territories were organized as castle-based districts (vármegyék) under royal officials called ispáns (counts), responsible for military, judicial, and fiscal duties.[71] By the 13th century, counties had evolved into noble self-governing bodies dominated by gentry assemblies, retaining substantial autonomy through the medieval and early modern periods despite Ottoman occupations and Habsburg reforms.[72][73] The system persisted post-1867 Austro-Hungarian Compromise but underwent centralization under communist rule after 1949, with counties restructured as administrative units subordinated to the state until the 1990 transition to democracy restored limited self-governance.[74] Governance occurs through county assemblies (megyei közgyűlések), directly elected every five years by proportional representation, which enact regional policies and approve budgets.[70] The assembly selects a president (elöljáró) to head an executive committee, overseeing operations; since 2022 legislation reviving historical terminology, presidents hold the title főispán and counties are officially vármegyék, emphasizing continuity with pre-modern traditions without altering substantive powers.[73] Counties lack hierarchical authority over municipalities but coordinate cross-jurisdictional services, with funding derived primarily from central transfers and EU cohesion funds.[75] Core functions include regional development planning, infrastructure projects spanning multiple localities, environmental management, and supplementary roles in education, healthcare, and cultural preservation where economies of scale demand it.[70][72] Post-2010 reforms centralized many competencies—such as public education and hospitals—to the national level or newly created districts (járások, 174 in total since 2013), narrowing counties' scope to development coordination amid criticisms of reduced local autonomy.[68][74] This shift reflects a broader emphasis on national efficiency, with counties tasked under the National Regional Development and Spatial Planning Concept to prioritize rural economic growth using targeted investments.[75] The counties, listed alphabetically with their administrative seats, are:| County | Seat |

|---|---|

| Bács-Kiskun | Kecskemét |

| Baranya | Pécs |

| Békés | Békéscsaba |

| Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén | Miskolc |

| Csongrád-Csanád | Szeged |

| Fejér | Székesfehérvár |

| Győr-Moson-Sopron | Győr |

| Hajdú-Bihar | Debrecen |

| Heves | Eger |

| Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok | Szolnok |

| Komárom-Esztergom | Tatabánya |

| Nógrád | Salgótarján |

| Pest | Budapest (surrounds) |

| Somogy | Kaposvár |

| Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg | Nyíregyháza |

| Tolna | Szekszárd |

| Vas | Szombathely |

| Veszprém | Veszprém |

| Zala | Zalaegerszeg |

Iceland

In Iceland, the term "county" corresponds to sýslur (singular: sýsla), which historically divided the country into 23 administrative, judicial, and fiscal districts, alongside independent towns (kaupstaðir). These counties originated from medieval Norwegian governance models imported during Iceland's settlement and served as the primary intermediate tier between national authority and local parishes (sóknir) or districts (hreppur). Each sýsla was headed by a sýslumaður (district commissioner or sheriff), appointed by the central government, who enforced laws, collected taxes and fines, managed local police forces, presided over district courts, and handled civil functions including bankruptcy proceedings, enforcement of judgments, and civil marriages outside ecclesiastical control.[77][78] The administrative significance of sýslur diminished in the late 20th century amid reforms centralizing power. In 1988, legislative changes effectively abolished counties as formal governance units, devolving most responsibilities—such as infrastructure, education, and social services—to the municipal level (sveitarstjórnir), which now number around 64 and handle direct local administration. This shift aligned with broader Nordic trends toward efficient, decentralized municipal autonomy, reducing intermediate layers to minimize bureaucratic overlap. However, sýslur retained limited roles; the 23 districts (with 24 sýslumenn to account for overlaps) continue to define jurisdictions for residual executive duties, including oversight of rural police forces (excluding Reykjavík's metropolitan force) and certain legal enforcements.[79] Today, sýslur primarily function in statistical and electoral contexts rather than active governance. Statistics Iceland subdivides the nation's 8 statistical regions (landsvæði) using the traditional 23 sýslur alongside towns and other minor divisions for data aggregation on population, economy, and demographics—e.g., as of 2023, rural sýslur like Austur-Skaftafellssýsla encompass sparse populations under 5,000. Electoral boundaries for parliamentary (Alþingi) constituencies also reference sýslur outlines, though adjusted for equity. This vestigial use underscores Iceland's unitary state structure, where national ministries retain strong oversight, and municipalities derive fiscal powers from central grants rather than independent taxation akin to counties elsewhere.[77][80]Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, the 26 historic counties serve as the primary basis for local government administration, with 31 local authorities including 26 county councils, three city councils (Dublin, Cork, and Galway), and two city and county councils (Limerick and Waterford).[81] These entities deliver essential services such as housing provision, road maintenance, spatial planning, environmental regulation, fire services, and libraries.[48] Elected county councils hold reserved functions, including adopting annual budgets, approving county development plans, setting policies for housing and environmental protection, and determining the local property tax rate.[82] Executive implementation of these policies falls to appointed chief executives.[83] The county divisions originated during the Norman conquest of the late 12th century, initially applied to territories under Anglo-Norman control as a means to administer justice, taxation, and military obligations, with King John formalizing twelve counties in 1210 and subsequent expansions completing the 32-county system across the island by the 16th century.[25] Following Irish independence in 1922, the southern 26 counties retained their role in local governance, subject to reforms under the Local Government Act 1991, which devolved additional powers, and the 2014 consolidation that integrated city councils into surrounding counties in Limerick and Waterford while splitting Dublin into three authorities.[83] This structure emphasizes decentralized service delivery, though funding relies heavily on central government grants supplemented by local taxes, with county councils grouped into three regional assemblies for coordination on economic and spatial planning since 2014.[48] Counties maintain cultural and identarian significance beyond administration, influencing sports leagues like Gaelic football and hurling organized by the Gaelic Athletic Association along county lines, and serving as reference units for electoral constituencies and census data.[84] Despite administrative adaptations, the boundaries have remained stable, preserving historical continuity while adapting to modern needs such as urban expansion in areas like Dublin, where the county is divided among multiple councils without altering the overarching county identity.[81]Italy

In Italy, provinces (province) serve as the primary administrative equivalent to counties, functioning as intermediate entities between the nation's 20 regions and its 7,904 municipalities (comuni).[85][86] Established post-unification in 1861 to standardize sub-regional governance, provinces coordinate multiple municipalities, handling tasks such as territorial planning, secondary road maintenance, and environmental protection.[86][87] As of 2024, Italy comprises 107 provinces, governed by a president elected indirectly by mayors and councilors from constituent municipalities, rather than through popular vote.[87] Their core functions include oversight of school buildings, waste management coordination, and promotion of local economic initiatives, though provinces lack significant fiscal independence and depend on allocations from regions and the central government.[88][87] A major restructuring occurred via the 2014 Delrio Law (Law 56/2014), which diminished provinces' elected bodies, transferred numerous competencies to municipal unions (unioni di comuni), and instituted 14 metropolitan cities—encompassing areas like Rome, Milan, and Naples—to supplant traditional provinces in densely populated zones, emphasizing urban integration and efficiency amid fiscal constraints.[89][88] This reform aimed to streamline administration but has drawn criticism for reducing local democratic input while preserving provinces' role in non-metropolitan areas for essential infrastructural and supervisory duties.[90] Historically, medieval Italian territories included feudal counties (contadi), such as the County of Tuscany or County of Savoy, which influenced early modern boundaries but bear little resemblance to today's technocratic provinces.[86] In contemporary usage, the provincial level aligns with EU NUTS-3 statistical classifications, facilitating data comparability across member states, though Italy's unitary framework limits provinces to supportive rather than autonomous governance akin to counties in federal systems.[87]Lithuania