Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Seychelles

View on Wikipedia

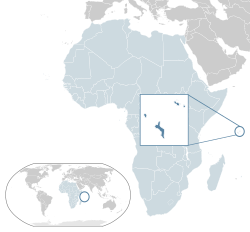

Seychelles[c] (/seɪˈʃɛl(z)/ ⓘ, /ˈseɪʃɛl(z)/;[9][10] French: [sɛʃɛl][11][12][13] or [seʃɛl][14]), officially the Republic of Seychelles (French: République des Seychelles; Seychellois Creole: Repiblik Sesel),[15] is an island country and archipelagic state consisting of 155 islands (as per the Constitution) in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, Victoria, is 1,500 kilometres (800 nautical miles) east of mainland Africa. Nearby island countries and territories include the Maldives, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, and the French overseas departments of Mayotte and Réunion to the south; and the Chagos Archipelago to the east. Seychelles is the smallest country in Africa as well as the least populated sovereign African country, with an estimated population of 100,600 in 2022.[16]

Key Information

Seychelles was uninhabited prior to being encountered by Europeans in the 16th century. It faced competing French and British interests until it came under full British control in the early 19th century. Since proclaiming independence from the United Kingdom in 1976, it has developed from a largely agricultural society to a market-based diversified economy, characterised by service, public sector, and tourism activities. From 1976 to 2015, nominal GDP grew nearly 700%, and purchasing power parity nearly 1600%. Since the late 2010s, the government has taken steps to encourage foreign investment.

As of the early 21st century, Seychelles has the highest nominal per capita GDP and the highest Human Development Index ranking of any African country.[17] According to the 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices, Seychelles is the 43rd-ranked electoral democracy worldwide and 1st-ranked electoral democracy in Africa.[18]

Seychellois culture and society is an eclectic mix of French, British, Indian and African influences, with infusions of Chinese elements. The country is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Southern African Development Community, and the Commonwealth of Nations.

History

[edit]

Seychelles was uninhabited until the 18th century when Europeans arrived with Indians and enslaved Africans. It remained a British colony from 1814 until its independence in 1976. Seychelles has never been inhabited by indigenous people, but its islanders maintain their own Creole heritage.

Early history

[edit]Seychelles was uninhabited throughout most of recorded history, although simulations of Austronesian migration patterns indicate a good probability that they visited the islands.[19] Tombs visible until 1910 at Anse Lascars on Silhouette Island have also been conjectured to belong to later Maldivian and Arab traders visiting the archipelago.[20] Vasco da Gama and his 4th Portuguese India Armada discovered the Seychelles on 15 March 1503; the first sighting was made by Thomé Lopes aboard Rui Mendes de Brito. Da Gama's ships passed close to an elevated island, probably Silhouette Island, and the following day Desroches Island. Later, the Portuguese mapped a group of seven islands and named them The Seven Sisters.[21] The earliest recorded landing was in January 1609, by the crew of the Ascension under Captain Alexander Sharpeigh during the fourth voyage of the British East India Company.

A transit point for trade between Africa and Asia, the islands were said to be occasionally used by pirates until the French began to take control in 1756 when a Stone of Possession was laid on Mahé by Captain Corneille Nicholas Morphey. The islands were named after French politician Jean Moreau de Séchelles, and were formally part of the colony of Isle de France.[22] In August 1770, the French ship Thélémaque under Captain Leblanc Lécore landed 15 white settlers and 13 African and Indian slaves on Ste. Anne Island.[23]

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Orpheus under Captain Henry Newcombe arrived at Mahé on 16 May 1794. Jean-Baptiste Quéau de Quinssy, the senior administrator in the Seychelles, refused to resist Orpheus and instead successfully negotiated with the British, resulting the islands remaining under French control as "neutral" territory. After British forces completed their invasion of Isle de France in December 1810, they assumed control over the Seychelles, which was formalised in the 1814 Treaty of Paris that ended the War of the Sixth Coalition. Seychelles became a separate crown colony from Mauritius in 1903. Elections in Seychelles were held in 1966 and 1970.

Independence

[edit]In 1976, Seychelles gained independence from the United Kingdom as a republic. It has since become a member of the Commonwealth.[24] In the 1970s Seychelles was "the place to be seen, a playground for film stars and the international jet set".[25] In 1977, a coup d'état by France Albert René ousted the first president of the republic, James Mancham.[26] René discouraged over-dependence on tourism and declared that he wanted "to keep Seychelles for the Seychellois".[25]

The 1979 constitution declared a socialist one-party state, which lasted until 1991.[27]

In the 1980s there were a series of coup attempts against President René, some of which were supported by South Africa. In 1981, Mike Hoare led a team of 43 South African mercenaries masquerading as holidaying rugby players in the 1981 Seychelles coup d'état attempt.[25] There was a gun battle at the airport, and most of the mercenaries later escaped in a hijacked Air India plane.[25] The leader of this hijacking was German mercenary D. Clodo, a former member of the Rhodesian SAS.[28] Clodo later stood trial in South Africa (where he was acquitted) as well as in his home country Germany for air piracy.[29]

In 1986, an attempted coup led by the Seychelles Minister of Defence, Ogilvy Berlouis, caused President René to request assistance from India. In Operation Flowers are Blooming, the Indian Navy's Nilgiri-class frigate Vindhyagiri arrived in Port Victoria to help avert the coup.[30]

The first draft of a new constitution failed to receive the requisite 60% of voters in 1992, but an amended version was approved in 1993.[31]

In June 2012, during a conference at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro, a commitment was made by the Seychelles government to protect 30% of its 1.35 million square kilometre marine waters within the country's marine protected areas.

In January 2013, Seychelles declared a state of emergency when the tropical cyclone Felleng caused torrential rain, and flooding and landslides destroyed hundreds of houses.[32][33]

Following the coup in 1977, the president always represented the same political party until the October 2020 Seychellois general election, which was historic in that the opposition party won. Wavel Ramkalawan was the first president who did not represent United Seychelles (the current name of the former Seychelles People's Progressive Front).[34][35]

In January 2023, Seychelles announced its final stages of completing its marine spatial plan. It would become the second largest ocean area at 1.35 million km2 (520,000 sq mi) behind Norway, in support of its blue economy.[36]

In October 2025, presidential runoff was won by former parliamentary speaker and main opposition leader, Patrick Herminie, meaning Herminie's party, United Seychelles (US) returned to power.[37] On 26 October 2025, Patrick Herminie was sworn in as Seychelles’ sixth president.[38]

Politics

[edit]The Seychelles president, who is head of state and head of government, is elected by popular vote for a five-year term of office. The cabinet is presided over and appointed by the president, subject to the approval of a majority of the legislature. As of 2025, the president is Patrick Herminie.

The unicameral Seychellois parliament, the National Assembly or Assemblée Nationale, consists of 35 members, 26 of whom are elected directly by popular vote, while the remaining nine seats are appointed proportionally according to the percentage of votes received by each party. All members serve five-year terms.

The Supreme Court of Seychelles, created in 1903, is the highest trial court in Seychelles and the first court of appeal from all the lower courts and tribunals. The highest court of law in Seychelles is the Seychelles Court of Appeal, which is the court of final appeal in the country.[39]

Political culture

[edit]

Seychelles' long-term president France-Albert René came to power after his supporters overthrew the first president James Mancham on 5 June 1977 in a coup d'état and installed him as president. René was at that time the prime minister. René ruled as a strongman under a socialist one-party system until 1993, when he was forced to introduce a multi-party system. He stepped down in 2004 in favour of his vice-president, James Michel, who was re-elected in 2006, 2011 and again in 2015.[40][41][42][43] On 28 September 2016, the Office of the President announced that Michel would step down effective 16 October, and that Vice President Danny Faure would complete the rest of Michel's term.[44]

On 26 October 2020, Wavel Ramkalawan, a 59-year-old Anglican priest, was elected the fifth President of the Republic of Seychelles. Ramkalawan was an opposition MP from 1993 to 2011, and from 2016 to 2020. He served as the Leader of the Opposition from 1998 to 2011 and from 2016 to 2020. Ramkalawan defeated incumbent Danny Faure by 54.9% to 43.5%. This marked the first time the opposition had won a presidential election in Seychelles.[45][46]

The primary political parties are the former long-time ruling socialist People's Party (PP), known until 2009 as the Seychelles People's Progressive Front (SPPF) now called United Seychelles (US), and the socially liberal Seychelles National Party (SNP).[47]

The election of the National Assembly was held on 22–24 October 2020. The Seychelles National Party, the Seychelles Party for Social Justice and Democracy and the Seychelles United Party formed a coalition, Linyon Demokratik Seselwa (LDS). LDS won 25 seats and US got 10 seats of the 35 seats of the National Assembly.[48] However, in the 2025 Seychellois general election United Seychelles won 15 out of 26 seats in the parliament.[49]

Foreign relations

[edit]Seychelles is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Indian Ocean Commission, La Francophonie, the Southern African Development Community and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Between 1979 and 1983, various plots to overthrow the non-aligned government of France-Albert Rene were, according to leading participants, supported by the United States, France, and South Africa. Commonly cited reasons for such attempts include Rene's socialist politics, his non-aligned stance toward the Western and Eastern Blocs, and the United States' military lease in the country, which was set to expire in 1990. All coup efforts in this period failed.[50] Under the Obama administration, the US began running drone operations out of Seychelles.[51] In the Spring of 2013, members of the Special-Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Africa mentored troops in Seychelles, along with a variety of other African nations.[51]

Military

[edit]The military of Seychelles is the Seychelles People's Defence Force which consists of a number of distinct branches: an infantry unit and coast guard, air force and a presidential protection unit. India has played and continues to play a key role in developing the military of Seychelles. After handing over two SDB Mk5 patrol vessels built by GRSE, the INS Tarasa and INS Tarmugli, to the Seychelles Coast Guard, which were subsequently renamed PS Constant and PS Topaz, India also gifted a Dornier 228 aircraft built by Hindustan Aeronautics Limited.[52] India also signed a pact to develop Assumption Island. Spread over 11 km2 (4 sq mi), it is strategically located in the Indian Ocean, north of Madagascar. The island is being leased for the development of strategic assets by India.[53] In 2018, Seychelles signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[54][55]

Incarceration

[edit]In 2014, Seychelles had the highest incarceration rate in the world of 799 prisoners per 100,000 population, exceeding the United States' rate by 15%.[56] However, the country's actual population was less than 100,000; as of September 2014, Seychelles had 735 actual prisoners, 6% of whom were female and were incarcerated in three prisons.[57]

The incarceration rate in Seychelles has since dropped significantly. It is no longer among the top ten countries with the highest rate of incarceration. In 2022, the incarceration rate was 287 per 100,000 population, being just the 31st highest in the world.[58]

Modern piracy

[edit]Seychelles is a key participant in the fight against Indian Ocean piracy primarily committed by Somali pirates.[59] Former president James Michel said that piracy costs between $7 million – $12 million a year to the international community: "The pirates cost 4% of the Seychelles GDP, including direct and indirect costs for the loss of boats, fishing, and tourism, and the indirect investment for the maritime security." These are factors affecting local fishing – one of the country's main national resources – which had a 46% loss in 2008–2009.[59] International contributions of patrol boats, planes or drones have been provided to help Seychelles combat sea piracy.[59]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Seychelles is divided into twenty-six administrative regions comprising all of the inner islands. Eight of the districts make up the capital of Seychelles and are referred to as Greater Victoria. Another 14 districts are considered the rural part of the main island of Mahé. Two more districts divide the island of Praslin and one covers La Digue as well as satellite and other Inner Islands. The rest of the Outer Islands (Îles Eloignées) make up the last district recently created by the tourism ministry.

|

Greater Victoria

|

Rural Mahé |

Praslin

La Digue and remaining Inner Islands

|

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

An island nation, Seychelles is located in the Somali Sea segment of the Indian Ocean, northeast of Madagascar and about 1,600 km (860 nmi) east of Kenya. The Constitution of Seychelles lists 155 named islands,[60] and a further 7 reclaimed islands have been created subsequent to the publication of the Constitution. The majority of the islands are uninhabited, with many dedicated as nature reserves. Seychelles' largest island, Mahé, is located 1,550 km (835 nmi) from Mogadishu (Somalia's capital).[61]

A group of 44 islands (42 granitic and 2 coralline) occupy the shallow waters of the Seychelles Bank and are collectively referred to as the inner islands. They have a total area of 244 km2 (94 sq mi), accounting for 54% of the total land area of the Seychelles and 98% of the entire population.

The islands have been divided into groups. There are 42 granitic islands known as the Granitic Seychelles. These are in descending order of size: Mahé, Praslin, Silhouette, La Digue, Curieuse, Félicité, Frégate, Ste. Anne, North, Cerf, Marianne, Grand Sœur, Thérèse, Aride, Conception, Petite Sœur, Cousin, Cousine, Long, Récif, Round (Praslin), Anonyme, Mamelles, Moyenne, Ile aux Vaches Marines, L'Islette, Beacon (Ile Sèche), Cachée, Cocos, Round (Mahé), L'Ilot Frégate, Booby, Chauve Souris (Mahé), Chauve Souris (Praslin), Ile La Fouche, Hodoul, L'Ilot, Rat, Souris, St. Pierre (Praslin), Zavé, Harrison Rocks (Grand Rocher).

There are two coral sand cays north of the granitics on the edge of the Seychelles Bank: Denis and Bird. There are two coral islands south of the Granitic: Coëtivy and Platte.

There are 29 coral islands in the Amirantes group, west of the granitic: Desroches, Poivre Atoll (comprising three islands—Poivre, Florentin and South Island), Alphonse, D'Arros, St. Joseph Atoll (comprising 14 islands—St. Joseph, Île aux Fouquets, Resource, Petit Carcassaye, Grand Carcassaye, Benjamin, Bancs Ferrari, Chiens, Pélicans, Vars, Île Paul, Banc de Sable, Banc aux Cocos and Île aux Poules), Marie Louise, Desnœufs, African Banks (comprising two islands—African Banks and South Island), Rémire, St. François, Boudeuse, Étoile, Bijoutier.

There are 13 coral islands in the Farquhar Group, south-southwest of the Amirantes: Farquhar Atoll (comprising 10 islands—Bancs de Sable, Déposés, Île aux Goëlettes, Lapins, Île du Milieu, North Manaha, South Manaha, Middle Manaha, North Island and South Island), Providence Atoll (comprising two islands—Providence and Bancs Providence) and St Pierre.

There are 67 raised coral islands in the Aldabra Group, west of the Farquhar Group: Aldabra Atoll (comprising 46 islands—Grande Terre, Picard, Polymnie, Malabar, Île Michel, Île Esprit, Île aux Moustiques, Ilot Parc, Ilot Émile, Ilot Yangue, Ilot Magnan, Île Lanier, Champignon des Os, Euphrate, Grand Mentor, Grand Ilot, Gros Ilot Gionnet, Gros Ilot Sésame, Héron Rock, Hide Island, Île aux Aigrettes, Île aux Cèdres, Îles Chalands, Île Fangame, Île Héron, Île Michel, Île Squacco, Île Sylvestre, Île Verte, Ilot Déder, Ilot du Sud, Ilot du Milieu, Ilot du Nord, Ilot Dubois, Ilot Macoa, Ilot Marquoix, Ilots Niçois, Ilot Salade, Middle Row Island, Noddy Rock, North Row Island, Petit Mentor, Petit Mentor Endans, Petits Ilots, Pink Rock and Table Ronde), Assumption Island, Astove and Cosmoledo Atoll (comprising 19 islands—Menai, Île du Nord (West North), Île Nord-Est (East North), Île du Trou, Goélettes, Grand Polyte, Petit Polyte, Grand Île (Wizard), Pagode, Île du Sud-Ouest (South), Île aux Moustiques, Île Baleine, Île aux Chauve-Souris, Île aux Macaques, Île aux Rats, Île du Nord-Ouest, Île Observation, Île Sud-Est and Ilot la Croix).

In addition to these 155 islands, as per the Constitution of Seychelles, there are 7 reclaimed islands: Ile Perseverance, Ile Aurore, Romainville, Eden Island, Eve, Ile du Port and Ile Soleil.

South Island, African Banks has been eroded by the sea. At St Joseph Atoll, Banc de Sable and Pelican Island have also eroded, while Grand Carcassaye and Petit Carcassaye have merged to form one island. There are also several unnamed islands at Aldabra, St Joseph Atoll and Cosmoledo. Pti Astove, though named, failed to make it into the Constitution for unknown reasons. Bancs Providence is not a single island, but a dynamic group of islands, comprising four large and about six very small islets in 2016.

Climate

[edit]The climate is very humid, as the islands are small,[62] and is classified by the Köppen-Geiger system as a tropical rain forest (Af). The temperature varies little throughout the year. Temperatures on Mahé vary from 24 to 30 °C (75 to 86 °F), and rainfall ranges from 2,900 mm (114 in) annually at Victoria to 3,600 mm (142 in) on the mountain slopes. Precipitation levels are somewhat less on the other islands.[63]

During the coolest months, July and August, the average low is about 24 °C (75 °F). The southeast trade winds blow regularly from May to November, and this is the most pleasant time of the year. The hot months are from December to April, with higher humidity (80%). March and April are the hottest months, but the temperature seldom exceeds 31 °C (88 °F). Most of the islands lie outside the cyclone belt, so high winds are rare.[63]

| Climate data for Victoria (Seychelles International Airport) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.4 (83.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.1 (75.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 379 (14.9) |

262 (10.3) |

167 (6.6) |

177 (7.0) |

124 (4.9) |

63 (2.5) |

80 (3.1) |

97 (3.8) |

121 (4.8) |

206 (8.1) |

215 (8.5) |

281 (11.1) |

2,172 (85.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 17 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 149 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 82 | 79.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 153.3 | 175.5 | 210.5 | 227.8 | 252.8 | 232.0 | 230.5 | 230.7 | 227.7 | 220.7 | 195.7 | 170.5 | 2,527.7 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[64] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration[65] | |||||||||||||

Wildlife

[edit]

Seychelles is among the world's leading countries to protect lands for threatened species, allocating 42% of its territory for conservation.[66] Like many fragile island ecosystems, Seychelles saw the loss of biodiversity when humans first settled in the area, including the disappearance of most of the giant tortoises from the granitic islands, the felling of coastal and mid-level forests, and the extinction of species such as the chestnut flanked white eye, the Seychelles parakeet, and the saltwater crocodile. However, extinctions were far fewer than on islands such as Mauritius or Hawaii, partly due to a shorter period of human occupation. Seychelles today is known for success stories in protecting its flora and fauna. The rare Seychelles black parrot, the national bird of the country, is now protected.

The freshwater crab genus Seychellum is endemic to the granitic Seychelles, and a further 26 species of crabs and five species of hermit crabs live on the islands.[67] From the year 1500 until the mid-1800s (approximately), the then-previously unknown Aldabra giant tortoise was killed for food by pirates and sailors, driving their numbers to near-extinction levels. Today, a healthy yet fragile population of 150,000 tortoises live solely on the atoll of Aldabra, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[68][69] Additionally, these ancient reptiles can further be found in numerous zoos, botanical gardens, and private collections internationally. Their protection from poaching and smuggling is overseen by CITES, whilst captive breeding has greatly reduced the negative impact on the remaining wild populations. The granitic islands of Seychelles supports three extant species of Seychelles giant tortoise.

Seychelles hosts some of the largest seabird colonies in the world, notably on the outer islands of Aldabra and Cosmoledo. In granitic Seychelles the largest colonies are on Aride Island including the world's largest numbers of two species. The sooty tern also breeds on the islands. Other common birds include cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) and the fairy tern (Gygis alba).[70] More than 1,000 species of fish have been recorded.[citation needed]

The granitic islands of Seychelles are home to roughly 268 flowering plant species, of which 70 (28%) are endemic.[71][72] Particularly well known is the coco de mer, a species of palm that grows only on the islands of Praslin and neighbouring Curieuse. Sometimes nicknamed the "love nut" (the shape of its "double" coconut resembles buttocks), the coco-de-mer produces the world's heaviest seed. The jellyfish tree is to be found in only a few locations on Mahé. This strange and ancient plant, in a genus of its own, Medusagyne seems to reproduce only in cultivation and not in the wild. Other unique plant species include Wright's gardenia (Rothmannia annae), found only on Aride Island’s Special Reserve. There are several unique species of orchid on the islands. Famous botanist Dr. Herb Herbertson was known for his love of the islands unique orchid varieties.[73]

Seychelles is home to two terrestrial ecoregions: Granitic Seychelles forests and Aldabra Island xeric scrub.[74] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 10/10, ranking it first globally out of 172 countries.[75]

Environmental issues

[edit]Since the use of spearguns and dynamite for fishing was banned through efforts of local conservationists in the 1960s, the wildlife is unafraid of snorkelers and divers. Coral bleaching in 1998 has damaged most reefs, but some reefs show healthy recovery (such as Silhouette Island).

Despite huge disparities across nations,[citation needed] Seychelles claims to have achieved nearly all of its Millennium Development Goals.[76] 17 MDGS and 169 targets have been achieved.[citation needed] Environmental protection is becoming a cultural value.[citation needed]

Their government's Seychelles Climate Guide describes the nation's climate as rainy, with a dry season with an ocean economy in the ocean regions. The Southeast Trades is on the decline but still fairly strong.[77] Reportedly, weather patterns there are becoming less predictable.[78]

Demographics

[edit]

When the British gained control of the islands during the Napoleonic Wars, they allowed the French upper class to retain their land. Both the French and British settlers used enslaved Africans, and although the British prohibited slavery in 1835, African workers continued to come. The Gran blan ("big whites") of French origin dominated economic and political life. The British administration employed Indians on indentured servitude to the same degree as in Mauritius resulting in a small Indian population. The Indians, like a similar minority of Chinese, were generally in the merchant class.[79]

Today, Seychelles is described as a fusion of peoples and cultures. Numerous Seychellois are considered multiracial: blending from African, Asian and European descent to create a modern creole culture. Evidence of this blend is also revealed in Seychellois food, incorporating various aspects of French, Chinese, Indian and African cuisine.[80]

As the islands of Seychelles had no indigenous population, the current Seychellois descend from people who immigrated, of which the largest ethnic groups were those of African, French, Indian and Chinese origin. The median age of the Seychellois is 34 years.[81]

Languages

[edit]French and English are official languages along with Seychellois Creole, which is a French-based creole language related to those spoken in Mauritius and Reunion. Seychellois Creole is the most widely spoken native language and de facto the national language of the country. Seychellois Creole is often spoken with English words and phrases mixed in.[82] About 91% of the population are native speakers of Seychellois Creole, 5.1% of English and 0.7% of French.[82] Most business and official meetings are conducted in English and nearly all official websites are in English. National Assembly business is conducted in Creole, but laws are passed and published in English.

Tamil is also a prominent language in Seychelles, spoken primarily by the Indo-Seychellois community, who form a significant part of the country's multilingual society.[83]

Religion

[edit]According to the 2022 census, most Seychellois are Christians: 61.3% were Catholic, pastorally served by the exempt Diocese of Port Victoria; 5.0% were Anglican and 8.6% follows other sects of Christianity.[2][84]

Hinduism is the second largest religion, adhered to by more than 5.4% of the population.[2][81] Hinduism is followed mainly by the Indo-Seychellois community.[85]

Islam is followed by another 1.6% of the population. Other faiths accounted for 1.1% of the population, while a further 5.9% were non-religious or did not specify a religion.[81]

Economy

[edit]

During the plantation era, cinnamon, vanilla and copra were the chief exports. In 1965, during a three-month visit to the islands, futurist Donald Prell prepared for the crown colony's Governor General an economic report containing a scenario for the future of the economy. Quoting from his report, in the 1960s, about 33% of the working population worked at plantations, and 20% worked in the public or government sector.[86][87] The Indian Ocean Tracking Station on Mahé used by the United States' Air Force Satellite Control Network was closed in August 1996 after the Seychelles government attempted to raise the rent to more than $10,000,000 per year.

Since independence in 1976, per capita output has expanded to roughly seven times the old near-subsistence level. Growth has been led by the tourist sector, which employs about 30% of the labour force, compared to agriculture which today employs about 3% of the labour force. Despite the growth of tourism, farming and fishing continue to employ some people, as do industries that process coconuts and vanilla.[citation needed]

As of 2013[update], the main export products are processed fish (60%) and non-fillet frozen fish (22%).[88]

The prime agricultural products currently produced in Seychelles include sweet potatoes, vanilla, coconuts and cinnamon. These products provide much of the economic support of the locals. Frozen and canned fish, copra, cinnamon and vanilla are the main export commodities.

The Seychelles government has prioritised a curbing of the budget deficit, including the containment of social welfare costs and further privatisation of public enterprises. The government has a pervasive presence in economic activity, with public enterprises active in petroleum product distribution, banking, imports of basic products, telecommunications and a wide range of other businesses. According to the 2013 Index of Economic Freedom, which measures the degree of limited government, market openness, regulatory efficiency, rule of law, and other factors, economic freedom has been increasing each year since 2010.[89] [unreliable source?]

The national currency of Seychelles is the Seychellois rupee. Initially tied to a basket of international currencies, it was unpegged and allowed to be devalued and float freely in 2008 on the presumed hopes of attracting further foreign investment in the Seychelles economy.[90]

Seychelles has emerged as the least corrupt country in Africa in the latest Corruption Perception Index report released by Transparency International in January 2020.[91]

Tourism

[edit]

In 1971, with the opening of Seychelles International Airport, tourism became a significant industry, essentially dividing the economy into plantations and tourism. The tourism sector paid better, and the plantation economy could expand only so far. The plantation sector of the economy declined in prominence, and tourism became the primary industry of Seychelles. Consequently, there was a sustained spate of hotel construction throughout almost the entire 1970s which included the opening of Coral Strand Smart Choice, Vista Do Mar and Bougainville Hotel in 1972.

In recent years the government has encouraged foreign investment to upgrade hotels and other services. These incentives have given rise to an enormous amount of investment in real estate projects and new resort properties, such as project TIME, distributed by the World Bank, along with its predecessor project MAGIC.[citation needed]

Since then the government has moved to reduce the dependence on tourism by promoting the development of farming, fishing, small-scale manufacturing and most recently the offshore financial sector, through the establishment of the Financial Services Authority and the enactment of several pieces of legislation (such as the International Corporate Service Providers Act, the International Business Companies Act, the Securities Act, the Mutual Funds and Hedge Fund Act, amongst others). In March 2015, Seychelles allocated Assumption Island to be developed by India.[92]

Owing to the effects of COVID-19, Seychelles shut down its borders to international tourism in the year 2020. As the national vaccination programme progressed well, the nation's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Tourism decided to reopen the borders to international tourists on 25 March 2021.

Energy

[edit]

Although multinational oil companies have explored the waters around the islands, no oil or gas has been found. In 2005, a deal was signed with US firm Petroquest, giving it exploration rights to about 30,000 km2 (12,000 sq mi) around Constant, Topaz, Farquhar and Coëtivy islands until 2014. Seychelles imports oil from the Persian Gulf in the form of refined petroleum derivatives at the rate of about 5,700 barrels per day (910 m3/d).

In recent years oil has been imported from Kuwait and Bahrain. Seychelles imports three times more oil than is needed for internal uses because it re-exports the surplus oil in the form of bunker for ships and aircraft calling at Mahé. There are no refining capacities on the islands. Oil and gas imports, distribution and re-export are the responsibility of Seychelles Petroleum (Sepec), while oil exploration is the responsibility of the Seychelles National Oil Company (SNOC).

Culture

[edit]Art

[edit]A National Art Gallery was inaugurated in 1994 on the occasion of the official opening of the National Cultural Centre, which houses the National Library and National Archives with other offices of the Ministry of Culture. At its inauguration, the Minister of Culture decreed that the exhibition of works of Seychellois artists, painters and sculptors was a testimony to the development of art in Seychelles as a creative form of expression, and provided a view of the state of the country's contemporary art. Painters have traditionally been inspired by Seychelles’ natural features to produce a wide range of works in media ranging from watercolours to oils, acrylics, collages, metals, aluminium, wood, fabrics, gouache, varnishes, recycled materials, pastels, charcoal, embossing, etching, and giclee prints. Local sculptors produce fine works in wood, stone, bronze and cartonnage. There are several art galleries around the island such as the National Gallery in Victoria, the Traditional wooden house galleries Kenwyn House gallery and Kaz Zanana Art Gallery in Victoria, Pagoda Art and Design Gallery in the Seychelles Chinese Culture Centre near the Selwyn Clarke market, and Eden gallery on Eden Island.

Music

[edit]Music and dance have always played prominent roles in Seychelles culture and local festivities. Rooted in African, Malagasy and European cultures, music characteristically features drums such as the tambour and tam-tam, and simple string instruments. The violin and guitar are relatively recent foreign imports which play a prominent role in contemporary music.

Among popular dances are the Sega, with hip-swaying and shuffling of the feet, and the Moutya, a dance dating back to the days of slavery, when it was often used to express strong emotions and discontent.

The music of Seychelles is diverse, a reflection of the fusion of cultures through its history. The folk music of the islands incorporates multiple influences in a syncretic fashion. It includes African rhythms, aesthetic and instrumentation, such as the zez and the bom (known in Brazil as berimbau); European contredanse, polka and mazurka; French folk and pop; sega from Mauritius and Réunion; taarab, soukous and other pan-African genres; and Polynesian, Indian and Arcadian music.

Contombley is a popular form of percussion music, as is Moutya, a fusion of native folk rhythms with Kenyan benga. Kontredans, based on European contra dance, is also popular, especially in district and school competitions during the annual Festival Kreol (International Creole Festival). Moutya playing and dancing often occur at beach bazaars. Music is sung in the Seychellois Creole of the French language, and in French and English.

In 2021,[93] the Moutya, a slave trade-era dance, was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List as a symbol of psychological comfort in its role of resistance against hardship, poverty, servitude and social injustice.[94]

Cuisine

[edit]

Staple foods of Seychelles include fish, seafood and shellfish dishes, often accompanied with rice.[95][96] Fish dishes are cooked several ways, such as steamed, grilled, wrapped in banana leaves, baked, salted and smoked.[95] Curry dishes with rice are also a significant part of the country's cuisine.[96][97]

Other staples include coconut, breadfruit, mangoes and kordonnyen fish.[98] Dishes are often garnished with fresh flowers.[98]

- Chicken dishes, such as chicken curry and coconut milk.[96]

- Coconut curry[96]

- Dal (lentils)[98]

- Fish curry[96]

- Saffron rice[98]

- Fresh tropical fruits[95][99]

- Ladob, eaten either as a savoury dish or as a dessert. The dessert version usually consists of ripe plantain and sweet potatoes (but may also include cassava, breadfruit or even corossol), boiled with coconut milk, sugar, nutmeg and vanilla in the form of a pod until the fruit is soft and the sauce is creamy.[100] The savoury dish usually includes salted fish, cooked in a similar fashion to the dessert version, with plantain, cassava and breadfruit, but with salt used in place of sugar (and omitting vanilla).

- Shark chutney typically consists of boiled skinned shark, finely mashed and cooked with squeezed bilimbi juice and lime. It is mixed with onion and spices, with the onion fried and cooked in oil.[100]

- Vegetables[96][99]

Media

[edit]The main daily newspaper is the Seychelles Nation and Seychelles News Agency dedicated to local government views and current topics. Other newspapers include Le Nouveau Seychelles Weekly, The People, Regar, and Today in Seychelles.[101][102] Foreign newspapers and magazines are readily available at most bookshops and newsagents. The papers are published mostly in Seychellois Creole, French and English.

Seychelles' prominent digital newspaper Seychelles News Agency was set to cease its operations completely on 1 January 2025, following the decision of the Seychelles government and National Information Service Agency (NISA) after ten years of news reporting in Seychelles.[103]

The main television and radio network, operated by the Seychelles Broadcasting Corporation, offers locally produced news and discussion programmes in the Seychellois Creole language, between 3 pm and 11:30 pm on weekdays and longer hours on weekends. There are also imported English- and French-language television programmes on Seychellois terrestrial television, and international satellite television has grown rapidly in recent years.

Sports

[edit]Parts of this article (those related to Beach Soccer World Cup) need to be updated. (May 2025) |

Seychelles' most popular sport is football, which has significantly grown in popularity in the last decade.[104] In 2015, Seychelles hosted the African Beach Soccer Championship. Ten years later, in May 2025, Seychelles hosted the 2025 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup making it the first ever FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup to be ever held in Africa.

Women

[edit]

Mothers tend to be dominant in the household, controlling most expenditure and looking after children's interests.[105] Unwed mothers are the societal norm, and the law requires fathers to support their children.[106] Men are important for their earning ability, but their domestic role is relatively peripheral.[105][106]

LGBT rights

[edit]Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 2016.[107] The bill decriminalising homosexuality was approved in a 14–0 vote.[108] Employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is banned in the Seychelles, making it one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBT people.[109][110]

Education

[edit]Seychelles has the highest literacy rate of any country in sub-Saharan Africa.[111] According to The World Factbook of the Central Intelligence Agency, as of 2018, 95.9% of the population aged 15 and over can read and write in the Seychelles.[111]

Until the mid-19th century, little formal education was available in Seychelles. The Catholic and Anglican churches opened mission schools in 1851. The Catholic mission later operated boys' and girls' secondary schools with religious brothers and nuns from abroad even after the government became responsible for them in 1944.[112]

A teacher training college opened in 1959, when the supply of locally trained teachers began to grow, and in short time many new schools were established. Since 1981 a system of free education has been in effect, requiring attendance by all children in grades one to nine, beginning at age six. Ninety-four percent of all children attend primary school.[113]

The literacy rate for school-age children rose to more than 90% by the late 1980s. Many older Seychellois had not been taught to read or write in their childhood; adult education classes helped raise adult literacy from 60% to a claimed 96% in 2020.[114]

There are a total of 68 schools in Seychelles. The public school system consists of 23 crèches, 25 primary schools and 13 secondary schools. They are located on Mahé, Praslin, La Digue and Silhouette. Additionally, there are three private schools: École Française, International School and the independent school. All the private schools are on Mahé, and the International School has a branch on Praslin. There are seven post-secondary (non-tertiary) schools: the Seychelles Polytechnic, School of Advanced Level Studies, Seychelles Tourism Academy, University of Seychelles Education, Seychelles Institute of Technology, Maritime Training Centre, Seychelles Agricultural and Horticultural Training Centre and the National Institute for Health and Social Studies.[citation needed]

The administration launched plans to open a university in an attempt to slow down the brain drain that has occurred. University of Seychelles, initiated in conjunction with the University of London, opened on 17 September 2009 in three locations, and offers qualifications from the University of London.[115]

Notable people

[edit]- Kevin Betsy, football coach and former professional footballer.

- Sandra Esparon – singer and performer

- Sonia Grandcourt – writer

- Regina Melanie – writer

- Laurence Norah – travel photographer, writer, and blogger

- Jean-Marc Volcy – musician

- Dr Louis Gaston Labat – physician and pioneer in regional anesthesia

See also

[edit]- Outline of Seychelles

- Index of Seychelles-related articles

- Illegal drug trade in Seychelles (highest heroin use per capita in the world)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Native and predominant ethnic group of the country; the creoles trace their mixed origin to mainland East African ethnicities and the Malagasy. They account for vast majority of the population.[1]

- ^ Non-Seychellois minority ethnic groups include smaller pockets of ethnic French, Indian, Chinese, and Arab peoples.[1]

- ^ Treated as singular or plural. The presence of the definite article ("the Seychelles") also varies.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "SeychellesThe World Factbook". -. 12 July 2023. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Seychelles Population and Housing Census 2022". National Bureau of Statistics Seychelles. 21 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "National Profiles | World Religion".

- ^ "MID-YEAR 2024 ESTIMATED RESIDENT POPULATION (ERP)". National Bureau of Statistics. 31 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Seychelles)". International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ "GINI index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2025" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 6 May 2025. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2025. Retrieved 6 May 2025.

- ^ Motschenbacher, Heiko (2 January 2020). "Greece, the Netherlands and (the) Ukraine: A Corpus-Based Study of Definite Article Use with Country Names". Names. 68 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/00277738.2020.1731241. hdl:11250/2676009. ISSN 1756-2279.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "Seychelles – English translation in German – Langenscheidt dictionary French-German" (in English, German, and French). Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Traduction: Seychelles – Dictionnaire français-anglais Larousse" (in English and French). Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Seychelles | French » English | PONS" (in English and French). Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "English Translation of "Seychelles" | Collins French-English Dictionary" (in English and French). Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Seychelles Facts | Britannica".

- ^ "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data (in Latin). Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk". World Bank.[date missing]

- ^ V-Dem Institute (2023). "The V-Dem Dataset". Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Scott M.; Callaghan, Richard (2008). "Seafaring simulations and the Origin of Prehistoric Settlers to Madagascar". In O'Connor, Sue; Clark, Geoffrey; Leach, Foss (eds.). Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes (PDF). Terra Australis. Canberra, ACT, Australia: ANU E Press. p. 52. ISBN 9781921313905.

- ^ Guébourg, Jean-Louis (2004). Les Seychelles (in French). Paris: Ed. Karthala. pp. 27–28. ISBN 2-84586-358-6. OCLC 419931142 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Seychelles: Settlement and the development of the plantation economy (1770–1944)". Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa.

- ^ "Our History". National Assembly of Seychelles. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Govinden, Gerard (27 August 2020). "250th Anniversary of First Settlement". Seychelles Nation. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ "History of Seychelles". seychelles.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d Joanna Symons (21 March 2005). "Seychelles: Life's a breeze near the equator" Archived 4 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "africanhistory.about.com". africanhistory.about.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Seychelles – Return to a Multiparty System". countrystudies.us.

- ^ Hoare, Mike The Seychelles Affair (Transworld, London, 1986; ISBN 0-593-01122-8)

- ^ Bartus László: Maffiaregény ISBN 9634405967, Budapest 2001

- ^ Brewster, David; Rai, Ranjit (10 August 2014). "Flowers Are Blooming: the story of the India Navy's secret operation in the Seychelles". Academia. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "FAO.org". www.fao.org.

- ^ "International Chapter activated for flooding in the Republic of Seychelles". United Nation. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "State of Emergency declared in the Seychelles". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Seychelles election marks first opposition victory in 44 years". TheGuardian.com. 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Seychelles elections: How a priest rose to become president". BBC News. 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Ocean conservation: Seychelles' marine spatial plan in final stages of completion". www.seychellesnewsagency.com.

- ^ "Seychelles presidential election: Opposition leader Patrick Herminie defeats Wavel Ramkalawan". www.bbc.com. 12 October 2025.

- ^ "Patrick Herminie sworn in as Seychelles sixth president". Retrieved 27 October 2025.

- ^ "The Judiciary". Bar Association of Seychelles. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "James Michel secures third term winning 50.15 percent votes in Seychelles presidential run-off". www.seychellesnewsagency.com.

- ^ "Results reflect popular will, observers say". Seychelles Nation. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ "Seychelles re-elects President Michel". Reuters. 21 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ "Vote buying claims mar Seychelles election". Agence France-Presse. 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

- ^ George Thande (28 September 2016). "Seychelles vice president to complete term of resigning president". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "Seychelles election: Wavel Ramkalawan in landmark win". BBC News. 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Seychelles opposition candidate wins presidential election". Al Jazeera. 25 October 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Seychellen4you – Seychelles Info". www.seychelles4u.com (in German). Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ "EISA Seychelles: 2020 National Assembly election results overview". www.eisa.org.

- ^ "TRT Afrika - Seychelles opposition candidate wins presidential runoff, incumbent leader concedes defeat". www.trtafrika.com.

- ^ Blum, William (2014). Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II (Updated ed.). London: Zed Books Ltd. pp. 267–269. ISBN 978-1-78360-177-6.

- ^ a b Turse, Nick (2015). Tomorrow's Battlefield: US Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa. Chicago: Haymarket Books. pp. 13, 55. ISBN 978-1-60846-463-0.

- ^ "India gifts second fast attack craft INS Tarasa to the Seychelles Coast Guard" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Times of India. 8 November 2014

- ^ Shubhajit Roy (12 March 2015) "India to develop strategic assets in 2 Mauritius, Seychelles islands" Archived 11 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. The Indian Express.

- ^ "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- ^ "President of Seychelles signs treaty banning nuclear weapons, meets with leaders at UN". Seychelles News Agency. 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Highest to Lowest – Prison Population Rates Across the World". World Prison Brief. 2014. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Data for prison population in Seychelles". World Prison Brief. 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Incarceration Rates by Country 2022". worldpopulationreview.com.

- ^ a b c Colonnello, Paolo (6 March 2012). "A Pirate's Prison Tucked Inside Seychelles Paradise". Worldcrunch. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ "Constitution of Seychelles". seylii.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021.

- ^ Werema, Gilbert. "Safeguarding Tourism and Tuna: Seychelles’ Fight against the Somali Piracy Problem." (2012).

- ^ "Background Note: Seychelles". state.gov. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 25 May 2010. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Climate". STGT.com. Stuttgart Information. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Victoria". wmo.int. World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Seychelles INTL AP Climate Normals 1971–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Mapped: The countries with the most protected land (#1 might surprise you)". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Haig, Janet (1984). "Land and freshwater crabs of the Seychelles and neighbouring islands". In David Ross Stoddart (ed.). Biogeography and Ecology of the Seychelles Islands. Springer. p. 123. ISBN 978-90-6193-107-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Aldabra giant tortoise". Idaho Falls Zoo/City of Idaho Falls, Idaho. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "Aldabra Atoll – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Attenborough, D (1998). The Life of Birds. BBC. pp. 220–221. ISBN 0563-38792-0.

- ^ Razafimandimbison, Sylvain G.; Kainulainen, Kent; Senterre, Bruno; Morel, Charles; Rydin, Catarina (2020). "Phylogenetic affinity of an enigmatic Rubiaceae from the Seychelles revealing a recent biogeographic link with Central Africa: gen. nov. Seychellea and trib. nov. Seychelleeae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 143 106685. Bibcode:2020MolPE.14306685R. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106685. PMID 31734453.

- ^ "Species – Ministry of Agriculture, Climate Change and Environment".

- ^ Gachanja, Nelly. "All About Seychelles". www.africa.com.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric [in German]; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; et al. (5 April 2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545, Supplemental material 2 table S1b. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ "Seychelles Millennium Development Goals: Status Report 2010" (PDF). undp.org. United Nations Development Programme. August 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Seychelles Climate Guide". meteo.gov.sc. Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change. 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Seychelles weather and climate: Blue Economy". Expertafrica.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Culture of Seychelles". Everyculture.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Seychellois Cuisine: A Fusion of Flavors and Traditions, A Foodie's Guide - Island Hopper Guides". 20 April 2025. Retrieved 28 August 2025.

- ^ a b c "Seychelles Population (2022) – Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ a b Lewis, M Paul; Simons, Gary F; Fennig, Charles D, eds. (2016). "Seychelles languages". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (19th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "Hindu Kavadi procession in the streets of Victoria on Sunday February 5". Nation.sc. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "History of Seychelles Hindu temple". Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ D. B. Prell (1965). Economic Study of the Seychelles Islands. D.B. Prell.

- ^ Economic. Study. Seychelles. 1965. D. B. Prell. 1965 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ OEC – Products exported by the Seychelles (2013) Archived 21 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Atlas.media.mit.edu. Retrieved on 8 December 2016.

- ^ "2013 Index of Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "Seychelles rupee is among best performing currencies against the dollar in Africa". www.seychellesnewsagency.com.

- ^ "Here are the 16 least corrupt countries in Africa". Pulse Ghana. 23 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ India to develop two islands in Indian Ocean – Times of India Archived 15 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Timesofindia.indiatimes.com (11 March 2015). Retrieved on 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Moutya – Historic Inscription During UNESCO Event in Paris | International Magazine Kreol". 2 November 2023.

- ^ "UNESCO – Moutya". UNESCO.

- ^ a b c Lonely Planet Mauritius, Reunion & Seychelles. Lonely Planet. 2010. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-1-74179-167-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Dyfed Lloyd Evans. The Recipes of Africa. Dyfed Lloyd Evans. pp. 235–236.

- ^ Practice Tests for IGCSE English as a Second Language Reading and Writing. Cambridge University Press. 4 February 2010. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-521-14059-1.

- ^ a b c d Paul Tingay (2006). Seychelles. New Holland Publishers. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-84537-439-6.

- ^ a b Lloyd E. Hudman; Richard H. Jackson (2003). Geography of Travel and Tourism. Cengage Learning. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-7668-3256-5.

- ^ a b Sarah Carpin (1998) Seychelles, Odyssey Guides, The Guidebook Company Limited. p. 77

- ^ "Today in Seychelles - Home". www.todayinseychelles.com. Retrieved 30 March 2025.

- ^ "Seychelles media guide". BBC News. 9 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ Vannier, Rassin (19 December 2024). "End of an era: After 10 years of operation, Seychelles News Agency to go offline on Jan. 1, 2025". Seychelles News Agency.

- ^ "Sport in The Seychelles". www.topendsports.com. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ a b Tartter, Jean R. "Status of Women". Indian Ocean country studies: Seychelles Archived 11 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine (Helen Chapin Metz, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (August 1994). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Seychelles (2007) Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (11 March 2008). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The Seychelles will make gay sex legal". Gay Star News. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Seychelles repeals colonial-era law banning gay sex". 18 May 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults", International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, authored by Lucas Paoli Itaborahy, May 2012 Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine : page: 34

- ^ "Employment Act, 1995" (PDF). Retrieved 9 May 2021.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Literacy – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Whitehead, Clive (December 2008). "'...a proper subject of reproach to the Empire'. Reflections on British Education Policy in the Seychelles 1938–1948". Education Research and Perspectives. 35 (2): 95–111.

- ^ "Seychelles: National Education Profile, 2018 Update" (PDF). 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "afrol News – Seychelles gets its 1st university". www.afrol.com. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

External links

[edit]Government

- SeyGov, main government portal

- State House, Office of the President of the Republic of Seychelles

- Central Bank of Seychelles, on-shore banking and insurance regulator

- Seychelles Investment Bureau, government agency promoting investment in Seychelles

- National Bureau of Statistics, government agency responsible for collecting, compiling, analysing and publishing statistical information

Religion

Folklore

- Compilation Books of Seychellois fairy tales (In Seychellois Creole)

- Seychelles Folklore Archive by University of Seychelles

General

- Seychelles. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Seychelles from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Seychelles from BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of Seychelles

Wikimedia Atlas of Seychelles- Island Conservation Society, non-profit nature conservation and educational non-governmental organisation

- Nature Seychelles, scientific/environmental non-governmental nature protection association

- The Seychelles Nation, the largest circulation local daily newspaper

- Seychelles Bird Records Committee

- Seychelles.travel Archived 4 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, government tourism portal

- Tourism Page

- Air Seychelles, Seychelles national airline

- ADST interview with U.S. Ambassador to Seychelles David Fischer

Seychelles

View on GrokipediaHistory

Pre-colonial and early human settlement

The Seychelles archipelago, comprising over 115 islands in the western Indian Ocean, remained uninhabited by permanent human populations prior to European contact in the 16th century and settlement in 1770.[3] Historical records, including cartographic evidence from Arab and Swahili sailors predating 1500 CE, indicate awareness of the islands but no established communities or material traces of sustained occupation.[6] Archaeological surveys have yielded no artifacts, structures, or remains attributable to pre-colonial indigenous groups, contrasting with nearby Madagascar, where Austronesian arrivals around 700–1200 CE left linguistic, genetic, and crop evidence.[7] Possible transient visits by Malagasy or Arab traders for provisioning cannot be ruled out, but the absence of settlement sites underscores the islands' effective isolation from major migration routes, such as those of Bantu expansions along East Africa or Austronesian voyages to the Mascarenes.[8] This lack of human presence stemmed from the archipelago's remoteness—over 1,500 kilometers northeast of Madagascar and 1,600 kilometers east of mainland Africa—compounded by limited arable land on steep, granitic terrain unsuitable for large-scale agriculture or societies reliant on it.[3] Prevailing monsoon winds and equatorial currents further hindered access, preventing the kind of repeated voyages that enabled colonization elsewhere in the Indian Ocean. In turn, this isolation allowed the islands' ecosystems to evolve without anthropogenic pressures like deforestation or species introduction for millennia, fostering high endemism prior to 18th-century introductions.[6]Colonial era under French and British rule

The Seychelles archipelago was first permanently settled by Europeans in August 1770, when the French vessel Thélemaque, under Captain Leblanc Lécore, landed 15 white settlers from Île de France (modern Mauritius) along with 13 African and Indian slaves on Île Sainte Anne near Mahé.[9] These early colonists, operating under French authority, cleared land for subsistence farming and cash crop plantations, importing additional slaves primarily from East Africa and Madagascar to provide forced labor.[6] The economy centered on cotton production, with plantations covering approximately 1,600 acres by the late French period, supplemented by minor exports of spices and timber; this slave-dependent system generated profits for a small elite of French planters while entailing harsh conditions for laborers, including physical punishment and family separations.[10] Amid the Napoleonic Wars, British forces captured the Seychelles in 1810 as part of their conquest of French-held Mauritius, with the islands surrendering without significant resistance and formally ceded to Britain under the 1814 Treaty of Paris.[11] Administered initially as a dependency of Mauritius, the British retained the plantation model, with cotton and later coconut copra as staples, but faced economic stagnation due to soil depletion and fluctuating markets.[6] Slavery, which underpinned the workforce of around 6,500 individuals by 1835, was abolished across British colonies effective February 1, 1835, freeing 6,251 slaves in the Seychelles and triggering a transitional "apprenticeship" system that bound former slaves to planters for limited wages before full emancipation.[12] Post-abolition labor shortages prompted planters to recruit indentured workers from India, East Africa, and China under contracts often marked by debt bondage and poor oversight, perpetuating exploitative hierarchies.[13] Demographic intermixing among French descendants, African slaves, and incoming Asian laborers gradually formed a Creole population characterized by French-based patois and blended customs, though European landowners maintained control over prime estates, entrenching economic disparities that favored a minority.[14] This colonial structure prioritized export agriculture over diversification, yielding modest prosperity for elites but systemic inequality for the majority, with limited infrastructure development until the late 19th century.[6]Road to independence (1960s-1976)

In the 1960s, decolonization movements gained momentum in Seychelles amid broader British colonial reforms across Africa and the Indian Ocean, prompting local demands for greater self-governance.[15] Political parties emerged to channel these aspirations: the Seychelles Democratic Party (SDP), founded in 1964 by James Mancham with a conservative platform initially favoring closer ties or integration with Britain, and the Seychelles People's United Party (SPUP), also established in 1964 by France-Albert René, advocating socialist policies and full independence from colonial rule.[16][17] A constitutional conference in London in March 1970 led to the Seychelles Order of September 30, 1970, granting partial autonomy effective November 12, 1970, with elections that November installing an SDP-led government under Chief Minister Mancham.[15][18] Further reforms culminated in the Seychelles Constitution Order of September 17, 1975, effective October 1, 1975, providing full internal self-government while Britain retained control over defense and foreign affairs.[18] Elections in October 1974, intended as a step toward independence, resulted in a hung parliament, prompting SDP and SPUP to form a coalition government despite ideological divides—SDP prioritizing economic liberalism and tourism development, SPUP emphasizing social welfare and anti-imperialism—which fostered underlying tensions between Mancham and René over policy direction and power-sharing.[19] This uneasy alliance agreed to pursue independence negotiations with Britain, rejecting proposals for association status in favor of sovereign status within the Commonwealth.[20] Seychelles achieved independence on June 29, 1976, after 166 years of British rule, with Mancham sworn in as president and René as prime minister under the coalition framework.[21] The new republic joined the Commonwealth, with Mancham advocating a market-oriented economy focused on tourism to leverage the islands' natural assets for growth.[22]Independence and the 1977 coup d'état

Seychelles achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 29 June 1976, establishing a republic within the Commonwealth with James Mancham of the Seychelles Democratic Party (SDP) as president and France-Albert René of the Seychelles People's United Party (SPUP) as prime minister in a coalition arrangement.[23] [21] Mancham's government adopted a pro-Western stance, prioritizing the liberalization of tourism to attract foreign investment and visitors, including efforts to position the islands as a luxury destination through international promotion and infrastructure development.[24] [25] Tensions between the SDP's market-oriented approach and the SPUP's socialist leanings escalated amid rumors of planned instability, culminating in a coup on 5 June 1977 while Mancham attended a Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in London.[19] Approximately 60 SPUP supporters, some trained in Tanzania, seized key government buildings in a swift, bloodless operation, installing René as president.[26] [27] René's faction presented the takeover as a preemptive measure against potential chaos or foreign-backed subversion, though Mancham denounced it as a betrayal exploiting institutional fragility in the nascent democracy.[28] In the coup's aftermath, René suspended the constitution, detained several opposition leaders and SDP members, and shuttered independent media outlets to consolidate control.[29] [27] This shift facilitated Seychelles' pivot toward the Soviet bloc for military training, economic aid, and diplomatic support, marking a departure from the prior pro-Western alignment.[27] [30] The events exposed vulnerabilities in the young state's power-sharing mechanisms, enabling rapid authoritarian entrenchment under the guise of stability.[31]Authoritarian one-party state (1977-1991)

Following the 1977 coup d'état that brought France-Albert René to power, Seychelles operated under provisional arrangements until March 1979, when a new constitution was promulgated by presidential decree, formally establishing a one-party state dominated by René's Seychelles People's Progressive Front (SPPF).[32][33] This framework centralized authority in the SPPF, eliminating opposition parties and legitimizing rule by decree, with René serving as both president and party leader.[34] The constitution's adoption without broad consultation reflected René's consolidation of power amid internal dissent, prioritizing ideological alignment over pluralistic governance.[35] René's administration implemented socialist policies, including nationalization of banks, transport, and key industries such as fishing and agriculture, which expanded state control but engendered inefficiencies and chronic shortages of goods like food and fuel.[27] Central planning stifled private enterprise, leading to disrupted production and a sharp decline in foreign investment, as investors fled political instability and expropriation risks; by the early 1980s, the economy had deteriorated markedly, with self-sufficiency goals in agriculture unmet despite state interventions.[27][36] Growth stagnated due to these missteps, compounded by reliance on foreign aid from Soviet-aligned states like Cuba, East Germany, and Libya, which provided military and economic support but fostered dependency rather than sustainable development; annual aid inflows reached approximately US$295 per capita in the 1980s, masking underlying fiscal imbalances.[27][8][37] Partial reforms in the mid-1980s, such as limited privatization in tourism, emerged under donor pressure but failed to reverse the stagnation until broader shifts later.[38] René's rule involved systematic repression to suppress dissent, including arbitrary detentions without trial, executions following suspected plots, and use of security forces for surveillance; reports document at least a dozen deaths or disappearances linked to political violence during the period.[39][40] A notable challenge came on November 25, 1981, when South African mercenaries led by Mike Hoare, disguised as tourists, attempted a coup to restore ousted president James Mancham; the plot involved 43 armed intruders seizing the airport, taking 70 hostages, and hijacking an Air India flight, but failed due to detection of weapons, resulting in several mercenary deaths and expulsions.[41][42] In response, René intensified crackdowns, deploying Tanzanian troops for internal security and expelling suspected sympathizers, which entrenched a climate of fear and arbitrary arrests estimated to affect hundreds over the decade.[43][40] These measures, while stabilizing the regime short-term, prioritized control over accountability, with state media and police suppressing opposition voices.[38]Transition to multi-party democracy (1991-present)

In December 1991, Seychelles voters approved constitutional amendments via referendum, abolishing the one-party doctrine and establishing a framework for multi-party competition, pluralism, and separation of powers.[44][45] This transition was influenced by global shifts away from socialism and domestic pressures for reform, though the ruling Seychelles People's Progressive Front (SPPF) retained significant control over the process.[46] The inaugural multi-party presidential and legislative elections occurred between July 20 and 23, 1993, following a June 18 referendum endorsing the new constitution with 61.7% approval. Incumbent President France-Albert René of the SPPF won re-election with 59.5% of the vote against opposition leader James Mancham, while the SPPF secured 56% of National Assembly seats; opposition parties contested the results, citing ballot stuffing, voter intimidation, and media bias favoring the incumbents.[40] The SPPF, rebranded as the Seychelles People's United Party and later United Seychelles (US), dominated subsequent elections in 1998, 2001, 2006, 2011, and 2015, maintaining presidential control and legislative majorities amid allegations of electoral manipulation and incomplete institutional reforms that blurred lines between party, state, and security apparatus.[47] Power alternated in the October 22–24, 2020, elections, when opposition leader Wavel Ramkalawan of the Linyon Demokratik Seselwa (LDS) alliance defeated US candidate Danny Faure with 54.9% of the vote in the first round, ending 43 years of SPPF/US executive dominance since the 1977 coup; the LDS also gained a slim legislative majority.[48] This marked a milestone in pluralism, with peaceful transfer despite prior tensions, though Ramkalawan's administration faced challenges from US-aligned institutions and legislative gridlock. In the September 27, 2025, general elections—requiring a runoff on October 11—incumbent Ramkalawan lost to opposition challenger Patrick Herminie, who secured 52.7% amid campaigns emphasizing economic pressures, drug trafficking, and sovereignty over maritime resources.[49][50] Voter turnout exceeded 85% in both rounds, underscoring competitive engagement.[51] Seychelles has achieved relative political stability with no violent disruptions since 1991, enabling consistent economic growth averaging 4-5% annually in the 2010s and tourism recovery post-global shocks.[52] Freedom House scores reflect progress, upgrading from "Partly Free" (scores in the 60s/100) in the 1990s to "Free" status by 2007, reaching 80/100 in 2025 due to enhanced electoral fairness and reduced government interference in media.[53][54] However, critics highlight persistent elite continuity, with SPPF/US networks influencing appointments and public enterprises, evoking nepotistic patterns from the one-party era—such as family-linked roles in state firms—and incomplete depoliticization of the judiciary and security forces, limiting full liberal democratic consolidation.[40] These factors, combined with high public debt (over 70% of GDP in 2023) and corruption perceptions indexes ranking Seychelles middling regionally, underscore uneven reforms despite electoral pluralism.[52]Geography

Archipelagic location and geological formation

The Seychelles is an archipelago comprising 115 islands located in the western Indian Ocean, approximately 1,600 kilometers east of the African mainland and northeast of Madagascar.[55] These islands occupy a vast exclusive economic zone (EEZ) spanning 1.35 million square kilometers, which is over 2,900 times larger than the total land area of 455 square kilometers.[56] [57] The archipelago divides into an inner group of 41 elevated granitic islands, including the main islands of Mahé, Praslin, and La Digue, and an outer group of low-lying coralline atolls and reefs.[55] Geologically, the inner granitic islands expose continental crust fragments from the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, making them the only mid-ocean granitic islands and among the world's oldest oceanic landmasses.[58] These formations originated as part of the Seychelles microcontinent, which rifted from the Indian subcontinent during the Late Cretaceous breakup of Gondwana, with final separation occurring approximately 65 to 75 million years ago through tectonic rifting and seafloor spreading.[59] [60] Subsequent subsidence of the surrounding plateau submerged much of the original landmass, leaving the rugged granitic peaks emergent while coral growth formed the outer islands atop submerged platforms.[61] This tectonic history underscores the archipelago's isolation, as the granitic group's continental origins and remote positioning limited connectivity to mainland influences. The Seychelles' strategic maritime position, astride key shipping lanes connecting East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and South Asia, has historically facilitated trade route oversight while amplifying exposure to oceanic isolation and transit dependencies.[62] [63] This archipelagic dispersion across expansive ocean expanses reinforces the geological isolation derived from ancient continental fragmentation, shaping a distinct physical geography vulnerable to maritime dynamics yet buffered from continental geological processes.[64]Climate variability and natural hazards