Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

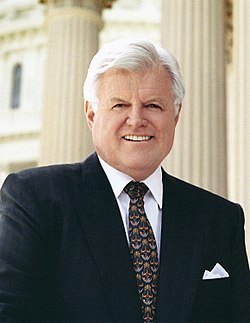

Ted Kennedy

View on Wikipedia

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts who served as a member of the United States Senate from 1962 to his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic Party and the prominent Kennedy family, he was the second-most-senior member of the Senate when he died. He is ranked fifth in U.S. history for length of continuous service as a senator. Kennedy was the younger brother of President John F. Kennedy and U.S. attorney general and U.S. senator Robert F. Kennedy, and the father of U.S. representative Patrick J. Kennedy.

Key Information

After attending Harvard University and earning his law degree from the University of Virginia, Kennedy began his career as an assistant district attorney in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. He won a November 1962 special election in Massachusetts to fill the vacant seat previously held by his brother John, who had taken office as the U.S. president. He was elected to a full six-year term in 1964 and was re-elected seven more times. After the Chappaquiddick incident in 1969 resulted in the death of his automobile passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, Kennedy pleaded guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of an accident and received a two-month suspended sentence. The incident and its aftermath hindered his chances of becoming president. He ran in 1980 in the Democratic primary campaign for the party's nomination, but lost to the incumbent president, Jimmy Carter.

Kennedy was known for his oratorical skills. His 1968 eulogy for his brother Robert and his 1980 rallying cry for modern American liberalism were among his best-known speeches. He became recognized as "The Lion of the Senate" through his long tenure and influence. Kennedy and his staff wrote more than 300 bills that were enacted into law. Unabashedly liberal, Kennedy championed an interventionist government that emphasized economic and social justice, but he was also known for working with Republicans to find compromises. Kennedy played a major role in passing many laws, including the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the National Cancer Act of 1971, the COBRA health insurance provision, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Ryan White AIDS Care Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the Mental Health Parity Act, the S-CHIP children's health program, the No Child Left Behind Act, and the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act. During the 2000s, he led several unsuccessful immigration reform efforts. Over the course of his Senate career, Kennedy made efforts to enact universal health care, which he called the "cause of my life". By his later years, Kennedy had come to be viewed as a major figure and spokesman for American progressivism.

On August 25, 2009, Kennedy died of a brain tumor (glioblastoma) at his home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, at the age of 77. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Early life

[edit]Edward Moore Kennedy was born at St. Margaret's Hospital in the Dorchester section of Boston, Massachusetts on February 22, 1932. He was the youngest of the nine children of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose Fitzgerald, members of prominent Irish-American families in Boston.[1] They constituted one of the wealthiest families in the nation after their marriage.[2] His eight siblings were Joseph Jr., John, Rose, Kathleen, Eunice, Patricia, Robert, and Jean. His older brother John asked to be the newborn's godfather, a request his parents honored, though they did not agree to his request to name the baby George Washington Kennedy (Kennedy was born on President George Washington's 200th birthday). They named the boy after their father's assistant and longtime friend.[3][4]

As a child, Kennedy was frequently uprooted by his family's moves among Bronxville, New York; Hyannis Port, Massachusetts; Palm Beach, Florida; and the Court of St. James's, in London, England.[5][6] His formal education started at Gibbs School in Kensington, London.[7] He had attended 10 schools by the age of eleven; these disruptions interfered with his academic success.[8] He was an altar boy at the St. Joseph's Church and was seven when he received his First Communion from Pope Pius XII in the Vatican.[9] He spent sixth and seventh grades at the Fessenden School, where he was a mediocre student,[1] and eighth grade at Cranwell Preparatory School, both in Massachusetts.[5] He was the youngest child and his parents were affectionate toward him, but they also compared him unfavorably with his older brothers.[1]

Between the ages of eight and sixteen, Kennedy suffered the traumas of his sister Rosemary's failed lobotomy and the deaths of two siblings: Joseph Jr. in an airplane explosion and Kathleen in an airplane crash.[1] Kennedy's affable maternal grandfather, John F. Fitzgerald, was the Mayor of Boston, a U.S. Congressman, and an early political and personal influence.[1] Kennedy spent his four high-school years at Milton Academy, a preparatory school in Milton, Massachusetts, where he received B and C grades. In 1950, he finished 36th in a graduating class of 56.[10] He did well at football there, playing on the varsity in his last two years; the school's headmaster later described his play as "absolutely fearless ... he would have tackled an express train to New York if you asked ... he loved contact sports".[10] Kennedy also played on the tennis team and was in the drama, debate, and glee clubs.[10]

College, military service, and law school

[edit]Like his father and brothers before him, Ted graduated from Harvard College.[11] In his spring semester, he was assigned to the athlete-oriented Winthrop House, where his brothers had also lived.[11] He was an offensive and defensive end on the freshman football team; his play was characterized by his large size and fearless style.[1] In his first semester, Kennedy and his classmates arranged to copy answers from another student during the final examination for a science class.[12] At the end of his second semester in May 1951, Kennedy was anxious about maintaining his eligibility for athletics for the next year,[1] and he had a classmate take his place at a Spanish exam.[13][14] The ruse was discovered and both were expelled for cheating.[13][15] As was standard for serious disciplinary cases, they were told they could apply for readmission within a year or two if they demonstrated good behavior during that time.[13][16]

In June 1951, Kennedy enlisted in the United States Army and signed up for an optional four-year term that was shortened to the minimum of two years after his father intervened.[13] Following basic training at Fort Dix in New Jersey, he requested assignment to Fort Holabird in Maryland for Army Intelligence training, but was dropped without explanation after a few weeks.[13] He went to Camp Gordon in Georgia for training in the Military Police Corps.[13] In June 1952, Kennedy was assigned to the honor guard at SHAPE headquarters in Paris, France.[1][13] His father's political connections ensured that he was not deployed to the ongoing Korean War.[1][17] While stationed in Europe, Kennedy traveled extensively on weekends and climbed the Matterhorn in the Pennine Alps.[18] After 21 months, he was discharged in March 1953 as a private first class.[13][18]

Kennedy re-entered Harvard in the summer of 1953 and improved his study habits.[1] His brother John was a U.S. Senator and the family was attracting more public attention.[19] Kennedy joined The Owl final club in 1954[20] and was also chosen for the Hasty Pudding Club and the Pi Eta fraternity.[21] Kennedy was on athletic probation during his sophomore year, and he returned as a second-string two-way end for the Crimson football team during his junior year. He barely missed earning his varsity letter.[22] Green Bay Packers head coach Lisle Blackbourn asked him about his interest in playing professional football.[23] Kennedy demurred, saying he had plans to attend law school and "go into another contact sport, politics."[24] In his senior season of 1955, Kennedy started at end for the Harvard football team and worked hard to improve his blocking and tackling to complement his 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m), 200 lb (91 kg) size.[18] In the season-ending Harvard–Yale game in the snow at the Yale Bowl on November 19 (which Yale won 21–7), Kennedy caught a pass to score Harvard's only touchdown;[25] the team finished the season with a 3–4–1 record.[26] Academically, Kennedy received mediocre grades for his first three years, improved to a B average for his senior year, and finished barely in the top half of his class.[27] Kennedy graduated from Harvard at age 24 in 1956 with an AB in history and government.[27]

Due to his low grades, Kennedy was not accepted by Harvard Law School.[16] He instead followed his brother Robert and enrolled in the University of Virginia School of Law in 1956.[1] That acceptance was controversial among faculty and alumni, who judged Kennedy's past cheating episodes to be incompatible with the University of Virginia's honor code; it took a full faculty vote to admit him.[28] Kennedy also attended The Hague Academy of International Law during one summer.[29] At Virginia, Kennedy felt that he had to study "four times as hard and four times as long" as other students to keep up.[30] He received mostly C grades[30] and was in the middle of the class ranking, but won the prestigious William Minor Lile Moot Court Competition.[1][31] He was elected head of the Student Legal Forum and brought many prominent speakers to the campus via his family connections.[32] While there, his questionable automotive practices were curtailed when he was charged with reckless driving and driving without a license.[1] He was officially named as manager of his brother John's 1958 Senate re-election campaign; Ted's ability to connect with ordinary voters on the street helped bring a record-setting victory margin that gave credibility to John's presidential aspirations.[33] Kennedy graduated from law school in 1959.[32]

Family and early career

[edit]

In October 1957 (early in his second year of law school), Kennedy met Joan Bennett at Manhattanville College; they were introduced after a dedication speech for a gymnasium that his family had donated at the campus.[34][35] Bennett was a senior at Manhattanville and had worked as a model and won beauty contests, but she was unfamiliar with politics.[34] After the couple became engaged, she grew nervous about marrying someone she did not know that well, but Joe Kennedy insisted that the wedding should proceed.[34] The couple was married by Cardinal Francis Spellman on November 29, 1958, at St. Joseph's Church in Bronxville, New York,[1][18] with the reception being held at the nearby Siwanoy Country Club.[36] Ted and Joan had three children: Kara (1960–2011), Edward Jr. (b. 1961) and Patrick (b. 1967). By the 1970s, the marriage was in trouble due to Ted's infidelity and Joan's growing alcoholism.[37]

Ted and Joan established Massachusetts residency after buying a townhouse on Charles River Square in Boston, and a home on Squaw Island, Cape Cod.[38] During Ted's tenure in the U.S. Senate, the Kennedys lived in a townhouse in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., and later, a 12,500-square-foot house in McLean, Virginia.[39][40] From 1982 until his death in 2009, the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts became Ted's principal residence.[41]

In 1959, Kennedy was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar.[42] In 1960, Ted's brother John announced his candidacy for President of the United States and Ted managed his campaign in the Western states.[1] Kennedy learned to fly and during the Democratic primary campaign he barnstormed around the western states, meeting with delegates and bonding with them by trying his hand at ski jumping and bronc riding.[18] The seven weeks he spent in Wisconsin helped his brother win the first contested primary of the season there and a similar time spent in Wyoming was rewarded when a unanimous vote from that state's delegates put his brother over the top at the 1960 Democratic National Convention.[43]

Following his victory in the presidential election, John resigned from his seat as U.S. Senator from Massachusetts, but Ted was not eligible to fill the vacancy until his thirtieth birthday on February 22, 1962.[44] Kennedy initially wanted to stay out west rather than run for office right away; he said, "The disadvantage of my position is being constantly compared with two brothers of such superior ability."[45] Kennedy's brothers were not in favor of his running immediately, but Kennedy ultimately coveted the Senate seat as an accomplishment to match his brothers, and their father overruled them.[18] John asked Massachusetts governor Foster Furcolo to name Kennedy family friend Ben Smith as interim senator for John's unexpired term, which he did in December 1960.[46] This kept the seat available for Ted.[18]

Meanwhile, Kennedy started work in February 1961 as an assistant district attorney at the Suffolk County, Massachusetts District Attorney's Office (for which he took a nominal $1 salary), where he developed a hard-nosed attitude towards crime.[47] He took many overseas trips, billed as fact-finding tours with the goal of improving his foreign policy credentials.[47][48][49] On a nine-nation Latin American trip in 1961, FBI reports from the time showed Kennedy meeting with Lauchlin Currie, an alleged former Soviet spy, together with locals in each country whom the reports deemed left-wingers and Communist sympathizers.[49][50] Reports from the FBI and other sources had Kennedy renting a brothel and opening up bordellos after hours during the tour.[49][50][51] The Latin American trip helped to formulate Kennedy's foreign policy views, and in subsequent Boston Globe columns he warned that the region might turn to communism if the U.S. did not reach out to it in a more effective way.[49][51] Kennedy also began speaking to local political organizations.[45]

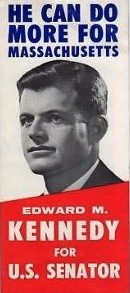

In the 1962 U.S. Senate special election in Massachusetts, Kennedy initially faced a Democratic Party primary challenge from Edward J. McCormack Jr., the state Attorney General. Kennedy's slogan was "He can do more for Massachusetts", the same one his brother John had used in his first campaign for the seat ten years earlier.[52] McCormack had the support of many liberals and intellectuals, who thought Kennedy inexperienced and knew of his suspension from Harvard, a fact which became public during the race.[45] Kennedy also faced the notion that with one brother President and another U.S. Attorney General, "Don't you think that Teddy is one Kennedy too many?" But Kennedy proved to be an effective street-level campaigner.[18] His charm was such that one delegate at the party convention said "He's completely unqualified and inexperienced. And I'm going to be with him".[16] In a televised debate, McCormack said "The office of United States Senator should be merited, and not inherited", and said that if his opponent's name was Edward Moore, not Edward Moore Kennedy, his candidacy "would be a joke".[45] Voters thought McCormack was overbearing—a Kennedy supporter said "McCormack was able to make a millionaire an underdog"[16]—and with the family political machine's finally getting fully behind him, Kennedy won the September 1962 primary by a two-to-one margin. In the November special election, Kennedy defeated Republican George Cabot Lodge II, product of another noted Massachusetts political family, gaining 55 percent of the vote.[18][53]

United States Senator

[edit]First years, brothers' assassinations

[edit]Kennedy was sworn into the Senate on November 7, 1962.[54] He maintained a deferential attitude towards the senior Southern members when he first entered the Senate, avoiding publicity and focusing on committee work and local issues.[55][56] He lacked his brother John's sophistication and Robert's intense, sometimes grating drive, but was more affable than either.[55] He was favored by Senator James Eastland, chair of the powerful Judiciary Committee. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, despite his feuds with John and Robert, liked Ted and told aides that he "had the potential to be the best politician in the whole family."[57]

On November 22, 1963, Ted was presiding over the Senate—a task given to junior members—when an aide rushed in to tell him his brother, President John F. Kennedy, had been shot. His brother Robert soon told him that the President was dead.[45] Ted and his sister Eunice flew to the family home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, to give the news to their invalid father, who had had a stroke two years earlier.[45]

On June 19, 1964, Kennedy was a passenger in a private Aero Commander 680 airplane that was flying in bad weather from Washington, D.C. to Massachusetts. The plane crashed into an apple orchard in Southampton, Massachusetts, on final approach to the Barnes Municipal Airport in Westfield.[58][59] The pilot and Edward Moss (one of Kennedy's aides) were killed.[60] Kennedy was pulled from the wreckage by Senator Birch Bayh,[58] and spent months in hospital recovering from a back injury, a punctured lung, broken ribs and internal bleeding.[45] He suffered chronic back pain for the rest of his life.[61][62] Kennedy took advantage of his convalescence to meet with academics and study issues more closely, and the hospital experience triggered his lifelong interest in the provision of health care.[45] His wife Joan did the campaigning for him in the regular 1964 U.S. Senate election in Massachusetts,[45] and he defeated his Republican opponent by a three-to-one margin.[53]

Kennedy was walking with a cane when he returned to the Senate in January 1965.[45] He employed a stronger and more effective legislative staff.[45] He took on President Johnson and almost succeeded in amending the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to explicitly ban the poll tax at the state and local level,[45][63] gaining a reputation for legislative skill.[64] He was a leader in pushing through the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended a quota system based upon national origin. He played a role in the creation of the National Teachers Corps.[45][65]

Kennedy initially said he had "no reservations" about the expanding U.S. role in the Vietnam War and acknowledged it would be a "long and enduring struggle".[64] Kennedy held hearings on the plight of refugees in the conflict, which revealed that the U.S. government had no coherent policy for refugees.[66] Kennedy tried to reform "unfair" and "inequitable" aspects of conscription.[64] By the time of a January 1968 trip to Vietnam, Kennedy was disillusioned by the lack of progress, and suggested publicly that the U.S. should tell South Vietnam, "Shape up or we're going to ship out."[67]

Ted initially advised his brother Robert against challenging the incumbent Johnson for the Democratic nomination in the 1968 presidential election.[45] Once Senator Eugene McCarthy's strong showing in the New Hampshire primary led to Robert's presidential campaign starting in March 1968, Kennedy recruited political leaders for endorsements to his brother in the western states.[45][68] Ted was in San Francisco when his brother Robert won the crucial California primary on June 4, 1968, and then after midnight, Robert was shot in Los Angeles and died the next day.[45] Ted was devastated, as he was closest to Robert among those in the Kennedy family.[69][page needed] Kennedy aide Frank Mankiewicz said of seeing Ted at the hospital where Robert lay mortally wounded: "I have never, ever, nor do I expect ever, to see a face more in grief."[45] At Robert's funeral at St. Patrick's Cathedral, Kennedy eulogized his older brother:

My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it. Those of us who loved him and who take him to his rest today, pray that what he was to us and what he wished for others will some day come to pass for all the world. As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."[70]

At the chaotic August 1968 Democratic National Convention, Mayor of Chicago Richard J. Daley and other party factions feared that Hubert Humphrey could not unite the party, and so encouraged Kennedy to make himself available for a draft.[45][71] The 36-year-old Kennedy was seen as the natural heir to his brothers,[52] and "Draft Ted" movements sprang up from various quarters.[71][72] Thinking he was only being seen as a stand-in for his brother and that he was not ready for the job, and getting an uncertain reaction from McCarthy and a negative one from Southern delegates, Kennedy rejected moves to place his name before the convention as a candidate.[71][72] He declined consideration for the vice-presidential spot.[55] Senator George McGovern remained the symbolic standard-bearer for Robert's delegates instead.[73]

After the deaths of his brothers, Kennedy took on the role of a surrogate father for their children.[74][75] By some reports, he also negotiated the October 1968 marital contract between Jacqueline Kennedy and Aristotle Onassis.[76] Kennedy denied this.[77]

Following Republican Richard Nixon's victory in November, Kennedy was assumed to be the front-runner for the 1972 Democratic nomination.[78] In January 1969, Kennedy defeated Louisiana Senator Russell B. Long by a 31–26 margin to become Senate Majority Whip, the youngest person to attain the position.[55][79] While this further boosted his presidential image, he appeared conflicted by the inevitability of having to run for president;[75][78] "Few who knew him doubted that in one sense he very much wanted to take that path", Time magazine reported, but "he had a fatalistic, almost doomed feeling about the prospect". The reluctance was in part due to the danger; Kennedy reportedly observed, "I know that I'm going to get my ass shot off one day, and I don't want to."[80][81] Indeed, there were death threats made against Kennedy for much of the rest of his career.[82]

Chappaquiddick incident

[edit]On the night of July 18, 1969, Kennedy was at Chappaquiddick Island hosting a party for the Boiler Room Girls, a group of young women who had worked on his brother Robert's presidential campaign.[78] Kennedy left the party with 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne.

Driving a 1967 Oldsmobile Delmont 88, he attempted to cross the Dike Bridge, which did not have a guardrail. Kennedy then lost control and crashed in the Poucha Pond inlet, a tidal channel. Kennedy escaped from the overturned vehicle, and, by his description, dove below the surface seven times, vainly attempting to rescue Kopechne. He swam to shore and left the scene, with Kopechne still trapped inside the vehicle. Kennedy did not report the accident to authorities until the next morning, by which time Kopechne's body had already been discovered.[78] Kennedy's cousin Joe Gargan said that he and Kennedy's friend Paul Markham, both of whom were at the party and came to the scene, had urged Kennedy to report it.[83]

A week after the incident, Kennedy pleaded guilty to leaving the scene of an accident and was given a suspended sentence of two months in jail.[78] That night, he gave a national broadcast in which he said, "I regard as indefensible the fact that I did not report the accident to the police immediately," but he denied driving under the influence of alcohol and denied any immoral conduct between him and Kopechne.[78] Kennedy asked the Massachusetts electorate whether he should stay in office or resign; after getting a favorable response in messages sent to him, Kennedy announced on July 30 that he would remain in the Senate and run for re-election the next year.[84]

In January 1970, an inquest into Kopechne's death was held in Edgartown, Massachusetts.[78] At the request of Kennedy's lawyers, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ordered the inquest to be conducted in secret.[78][85][86] The presiding judge, James A. Boyle, concluded that some aspects of Kennedy's story of that night were untrue, and that negligent driving "appears to have contributed" to the death of Kopechne.[86] A grand jury conducted an investigation in April 1970 but issued no indictment, after which Boyle made his inquest report public.[78] Kennedy deemed its conclusions "not justified."[78] Questions about the incident generated many articles and books.[87]

1970s

[edit]

At the end of 1968, Kennedy had joined the new Committee for National Health Insurance at the invitation of its founder, United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther.[88][89] In May 1970, Reuther died and Senator Ralph Yarborough, chairman of the full Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee and its Health subcommittee, lost his primary election, propelling Kennedy into a leadership role on the issue of national health insurance.[90] Kennedy introduced a bipartisan bill in August 1970 for single-payer universal national health insurance with no cost sharing, paid for by payroll taxes and general federal revenue.[91]

Despite the Chappaquiddick controversy, Kennedy easily won re-election to the Senate in November 1970 with 62% against underfunded Republican candidate Josiah Spaulding, although he received about 500,000 fewer votes than in 1964.[87]

In January 1971, Kennedy lost his position as Senate Majority Whip to Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, 31–24,[92] probably because of Chappaquiddick. He later told Byrd that the defeat had allowed Kennedy to focus more on issues and committee work,[93][3] where he could exert influence independently from the Democratic party apparatus.[94] Kennedy began a decade as chairman of the Subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research of the Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee.

In February 1971, Nixon proposed health insurance reform—an employer mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, federalization of Medicaid for the poor with dependent minor children, and support for health maintenance organizations.[95][96] Hearings on national health insurance were held in 1971, but no bill had the support of House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committee chairmen Representative Wilbur Mills and Senator Russell Long.[95][97] Kennedy sponsored and helped pass the limited Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973.[96][98] He played a leading role, with Senator Jacob Javits, in the creation and passage of the National Cancer Act of 1971.[99]

In October 1971, Kennedy made his first speech about The Troubles in Northern Ireland: he said that "Ulster is becoming Britain's Vietnam", advocating for the withdrawal of British troops, called for a united Ireland,[100] and declared that Ulster Unionists who could not accept this "should be given a decent opportunity to go back to Britain" (a position he backed away from within a few years).[101] Kennedy was sharply criticised by the British and Ulster unionists, and he formed a long political relationship with Social Democratic and Labour Party founder John Hume.[100] In scores of anti-war speeches, Kennedy opposed Nixon's policy of Vietnamization, calling it "a policy of violence [that] means more and more war".[87] In December 1971, Kennedy strongly criticized the Nixon administration's support for Pakistan and its ignoring of "the brutal and systematic repression of East Bengal by the Pakistani army".[102] He traveled to India and wrote a report on the plight of the 10 million Bengali refugees.[103] In February 1972, Kennedy flew to Bangladesh and delivered a speech at the University of Dhaka, where a killing rampage had begun a year earlier.[103]

The Chappaquiddick incident had greatly hindered Kennedy's presidential prospects,[80] and shortly afterwards he declared he would not be a candidate in the 1972 presidential election.[78] Nevertheless, polls in 1971 suggested he could win the nomination, and Kennedy gave thought to running. In May he decided not to, saying he needed "breathing time" to gain more experience and take care of his brothers' children, and that "it feels wrong in my gut."[104] Nevertheless, in November 1971, a Gallup Poll still had him in first place in the Democratic nomination race with 28 percent.[105] George McGovern was close to clinching the Democratic nomination in June 1972, when various anti-McGovern forces tried to get Kennedy to enter the contest at the last minute, but he declined.[106] At the 1972 Democratic National Convention, McGovern repeatedly tried to recruit Kennedy as his vice presidential running mate, but Kennedy turned him down.[106] When McGovern's choice of Thomas Eagleton stepped down soon after the convention, McGovern again tried to get Kennedy to take the nod, again without success.[106] McGovern instead chose Kennedy's brother-in-law Sargent Shriver.

In 1973, Kennedy's 12-year-old son Edward Jr., was diagnosed with bone cancer; his leg was amputated and he underwent a long, difficult, experimental two-year drug treatment.[78][107] The case brought international attention among doctors and in the media,[107] as did the young Kennedy's return to skiing half a year later.[108] Son Patrick was suffering from severe asthma attacks.[78] The pressure of the situation mounted on Joan Kennedy. On several occasions, she entered facilities for treatment of alcoholism and emotional strain, and was arrested for drunk driving after a traffic accident.[78][109]

In February 1974, Nixon proposed more comprehensive health insurance reform—an employer mandate to offer private health insurance if employees volunteered to pay 25 percent of premiums, replacement of Medicaid by state-run health insurance plans available to all with income-based premiums and cost sharing, and replacement of Medicare with a federal program that eliminated the limit on hospital days, added income-based out-of-pocket limits, and added outpatient prescription drug coverage.[110][111] In April 1974, Kennedy and Mills introduced a bill for near-universal national health insurance with benefits identical to the expanded Nixon plan—but with mandatory participation by employers and employees through payroll taxes—both plans were criticized by labor, consumer, and senior citizen organizations because of their substantial cost sharing.[110][112][110][113]

In the wake of the Watergate scandal, Kennedy pushed campaign finance reform; he was a leading force behind passage of the Federal Election Campaign Act Amendments of 1974, which set contribution limits and established public financing for presidential elections.[114][115] In 1974, Kennedy travelled to the Soviet Union, where he met with leader Leonid Brezhnev and advocated a full nuclear test ban as well as relaxed emigration, met with Soviet dissidents, and secured an exit visa for cellist Mstislav Rostropovich.[116] Kennedy's Subcommittee on Refugees and Escapees continued to focus on Vietnam, especially after the Fall of Saigon in 1975.[87]

Kennedy had initially opposed busing schoolchildren across racial lines, but grew to support the practice as it became a focal point of civil rights efforts.[117] After federal judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered the Boston School Committee in 1974 to racially integrate Boston's public schools via busing, Kennedy made a surprise appearance at a September 1974 anti-busing rally in City Hall Plaza to express the need for peaceful dialogue and was met with hostility.[117][118][119] The predominantly white crowd yelled insults about his children, hurled tomatoes and eggs at him as he retreated into the John F. Kennedy Federal Building, and went broke one of its glass walls.[117][118][119]

Kennedy was again much talked about as a contender in the 1976 presidential election, with no strong front-runners among the other possible Democratic candidates.[120] Kennedy's concerns about his family were strong, and Chappaquiddick was still in the news, with The Boston Globe, The New York Times Magazine, and Time magazine all reassessing the incident and raising doubts about Kennedy's version of events.[78][121][122] In 1977, the Times described Chappaquiddick as Kennedy's Watergate.[123] In September 1974, Kennedy announced that for family reasons he would not run in 1976, declaring that his decision was "firm, final, and unconditional."[120] Kennedy was up for Senate re-election in 1976. He defeated a primary challenger who was angry at his support for school busing in Boston. Kennedy won the general election with 69 percent.[124]

The Carter administration years were difficult for Kennedy; he had been the most important Democrat in Washington since his brother Robert's death, but now Carter was, and Kennedy at first did not have a full committee chairmanship to wield influence.[125] Carter in turn sometimes resented Kennedy's status as a political celebrity.[3] Despite similar ideologies, their priorities were different.[125][126] Kennedy told reporters he was content with his congressional role and denied presidential ambitions,[123] but by late 1977 Carter reportedly saw Kennedy as a future challenger to his presidency.[127]

Kennedy and his wife Joan separated in 1977, though they still staged joint appearances.[128] He held Health and Scientific Research Subcommittee hearings in March 1977 that led to public revelations of extensive scientific misconduct by contract research organizations, including Industrial Bio-Test Laboratories.[129][130][131] Kennedy visited China on a goodwill mission in December 1977, meeting with leader Deng Xiaoping and eventually gaining permission for several mainland Chinese nationals to leave the country; in 1978, he visited the Soviet Union and Brezhnev and dissidents there again.[132] During the 1970s, Kennedy showed interest in nuclear disarmament, and as part of his efforts in this field visited Hiroshima in January 1978 and gave a speech to that effect at Hiroshima University.[133] He became chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1978, by which time he had amassed a wide-ranging Senate staff of a hundred.[134]

As a candidate, Carter had proposed health care reform that included key features of Kennedy's national health insurance bill, but in December 1977, Carter told Kennedy his bill must preserve a large role for private insurance companies, minimize federal spending (precluding payroll tax financing), and be phased-in to not interfere with Carter's paramount domestic policy objective—balancing the budget.[135][136][137] Kennedy and labor compromised and made the requested changes, but broke with Carter in July 1978 when he would not commit to pursuing a single bill with a fixed schedule for phasing-in comprehensive coverage.[135][136][138] Frustrated by Carter's budgetary concerns and caution,[2] in a December 1978 speech on national health insurance at the Democratic midterm convention, Kennedy said regarding liberal goals that "sometimes a party must sail against the wind" and in particular should provide health care as "a basic right for all, not just an expensive privilege for the few."[139][140][141]

In May 1979, Kennedy proposed a new bipartisan universal national health insurance bill—choice of competing federally regulated private health insurance plans with no cost sharing financed by income-based premiums via an employer mandate and individual mandate, replacement of Medicaid by government payment of premiums to private insurers, and enhancement of Medicare by adding prescription drug coverage and eliminating premiums and cost sharing.[142][143] In June 1979, Carter proposed more limited health insurance reform—an employer mandate to provide catastrophic private health insurance plus coverage without cost sharing for pregnant women and infants, federalization of Medicaid with extension to all of the very poor, and adding catastrophic coverage to Medicare.[142] Neither plan gained any traction in Congress,[144][145] and the failure to come to agreement represented the final political breach between the two.[146] Carter wrote in 1982 that Kennedy "ironically" thwarted Carter's efforts to provide a comprehensive health-care system.[147] In turn, Kennedy wrote in 2009 that his relationship with Carter was "unhealthy" and that "Carter was a difficult man to convince – of anything."[148]

1980 presidential campaign

[edit]

Kennedy decided to seek the Democratic nomination in the 1980 presidential election by launching an unusual, insurgent campaign against the incumbent Carter. A midsummer 1978 poll showed that Democrats preferred Kennedy over Carter by a 5-to-3 margin.[87] Through summer 1979, as Kennedy deliberated whether to run, Carter was not intimidated despite his 28 percent approval rating, saying publicly: "If Kennedy runs, I'll whip his ass."[144][146] Carter later asserted that Kennedy's constant criticism of his policies was a strong indicator Kennedy was planning to run.[149] Labor unions urged Kennedy to run, as did some Democratic party officials who feared Carter's unpopularity could result in heavy losses in the 1980 congressional elections.[150] Kennedy decided to run in August 1979, when polls showed him with a 2-to-1 advantage over Carter;[151] Carter's approval rating slipped to 19 percent.[150] Kennedy formally announced his campaign on November 7, 1979, at Boston's Faneuil Hall.[146] He had already received substantial negative press from a rambling response to the question "Why do you want to be President?" during an interview with Roger Mudd of CBS News a few days earlier.[146][152] The Iranian hostage crisis, which began on November 4, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, which began on December 27, prompted the electorate to rally around the president and allowed Carter to pursue a Rose Garden strategy of staying at the White House, which kept Kennedy's campaign out of the headlines.[146][153]

Kennedy's campaign staff was disorganized and he was initially an ineffective campaigner.[153][154] There is little evidence Kennedy truly wanted to be president;[146] to observers such as Ellen Goodman and Anthony Lewis, the Mudd interview confirmed their belief that he did not want the job. The incoherent answer to Mudd was an example of what Walter Mondale, who knew Kennedy well from the Senate, described as his way of avoiding a topic by "using words, but they didn't come together somehow".[155] Chris Whipple of Life, who was present for the interview, wondered if Kennedy's answer was "consciously or otherwise, an act of political self-destruction ... The campaign was over. His heart just wasn't in it".[156] The Chappaquiddick incident emerged as a more significant issue than the staff had expected, with columnists and editorials criticizing Kennedy's answers on the matter.[153] In the January 1980 Iowa caucuses that initiated the primaries season, Carter demolished Kennedy by a 59–31 percent margin.[146] Kennedy's fundraising immediately declined and his campaign had to downsize, but he remained defiant, saying "[Now] we'll see who is going to whip whose what."[157] Nevertheless, Kennedy lost three New England contests.[146] Kennedy did form a more coherent message about why he was running, saying at Georgetown University: "I believe we must not permit the dream of social progress to be shattered by those whose premises have failed."[158] However, concerns over Chappaquiddick and issues related to character prevented Kennedy from gaining the support of many who were disillusioned with Carter.[159] During a St. Patrick's Day Parade in Chicago, Kennedy had to wear a bullet-proof vest due to assassination threats, and hecklers yelled "Where's Mary Jo?" at him.[160] In the key March 18 primary in Illinois, Kennedy failed to gain the support of Catholic voters, and Carter won 155 of 169 delegates.[65][146]

With little mathematical hope of winning the nomination and polls showing another likely defeat in New York, Kennedy prepared to withdraw.[146] However, partially due to Jewish voter unhappiness with a U.S. vote at the United Nations against Israeli settlements in the West Bank, Kennedy staged an upset and won the March 25 vote by 59–41 percent.[146] Carter responded with an advertising campaign that attacked Kennedy's character without explicitly mentioning Chappaquiddick, but Kennedy still managed a narrow win in the April Pennsylvania primary.[146] Carter won 11 of 12 primaries held in May, while on the June 3 Super Tuesday primaries, Kennedy won California, New Jersey, and three smaller states out of eight contests.[161] Overall, Kennedy had won 10 presidential primaries against Carter, who won 24.[162]

Although Carter now had enough delegates to clinch the nomination,[161] Kennedy carried his campaign on to the 1980 Democratic National Convention in August in New York, hoping to pass a rule there that would free delegates from being bound by primary results and open the convention.[146] This move failed on the first night, and Kennedy withdrew.[146] On the second night, August 12, Kennedy delivered the most famous speech of his career, written in part by speech writer Bob Shrum.[163][164] Drawing on allusions to and quotes of Martin Luther King Jr., Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Alfred Lord Tennyson to say that American liberalism was not passé,[165] he concluded with the words:

For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.

The Madison Square Garden audience reacted with wild applause and demonstrations for half an hour.[146] On the final night, Kennedy arrived late after Carter's acceptance speech and while he shook Carter's hand, he failed to raise Carter's arm in the traditional show of party unity.[65][165]

1980s

[edit]

The 1980 election saw the Republicans capture not just the presidency but the Senate as well, and Kennedy was in the minority party for the first time in his career. Kennedy did not dwell upon his presidential loss,[146] but instead reaffirmed his public commitment to American liberalism.[166] He chose to become the ranking member of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee rather than of the Judiciary Committee, which he would later say was one of the most important decisions of his career.[166] Kennedy became a committed champion of women's issues,[166] and established relationships with select Republican senators to block Reagan's actions and preserve and improve the Voting Rights Act, funding for AIDS treatment, and equal funding for women's sports under Title IX.[146] To combat being in the minority, he worked long hours and devised a series of hearings-like public forums to which he could invite experts and discuss topics important to him.[146] Kennedy could not hope to stop all of Reagan's reshaping of government, but was often nearly the sole effective Democrat battling him.[167]

In January 1981, Ted and Joan Kennedy announced they were getting a divorce.[168] The proceedings were generally amicable,[168] and she received a reported $4 million settlement when the divorce was granted in 1982.[169] Later that year, Kennedy created the Friends of Ireland organization with Senator Daniel Moynihan and House Speaker Tip O'Neill to support initiatives for peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland.[170]

Kennedy easily defeated Republican businessman Ray Shamie to win re-election in 1982.[171] Senate leaders granted him a seat on the Armed Services Committee, while allowing him to keep his other major seats despite the traditional limit of two such seats.[172] Kennedy became very visible in opposing aspects of the foreign policy of the Reagan administration, including U.S. intervention in the Salvadoran Civil War and U.S. support for the Contras in Nicaragua, and in opposing Reagan-supported weapons systems, including the B-1 bomber, the MX missile, and the Strategic Defense Initiative.[172] Kennedy became the Senate's leading advocate for a nuclear freeze[172] and was a critic of Reagan's confrontational policies toward the Soviet Union.[173][174][175]

A 1983 KGB memo indicates that Kennedy engaged in back-channel communication with the Soviet Union.[176][177][178] According to a May 1983, memorandum from Chairman of the KGB Viktor Chebrikov to general secretary Yuri Andropov, former U.S. Senator John V. Tunney—a friend of Kennedy's—visited Moscow that month and conveyed a message from Kennedy to Andropov.[178][179][180][181] The memo indicates that the stated purpose of the communication was to "'root out the threat of nuclear war', 'improve Soviet-American relations' and 'define the safety of the world'".[181] Kennedy reportedly offered to visit Moscow "'to arm Soviet officials with explanations regarding problems of nuclear disarmament so they may be better prepared and more convincing during appearances in the USA'" and to set up U.S. television appearances for Andropov.[181][178]

Chebrikov also noted "a little-hidden secret that [Kennedy] intended to run for president in 1988 and that the Democratic Party 'may officially turn to him to lead the fight against the Republicans' in 1984 — turning the proposal from one purely about international cooperation to one tinged with personal political aspiration."[181] Andropov was unimpressed by Kennedy's overtures.[179] After the Chebrikov memo was unearthed, Tunney and a Kennedy spokesperson denied it was true.[181] Former Reagan administration negotiator Max Kampelman has asserted that Kennedy did engage in back-channel communications, but added that "'the senator never acted or received information without informing the appropriate United States agency or official'". Kenneth Adelman, a deputy ambassador to the United Nations under Reagan, has asserted that the Reagan administration knew of back-channel communications between senators and the Soviet Union and were unconcerned.[181]

Kennedy's staff drew up detailed plans for a candidacy in the 1984 presidential election that he considered, but with his family opposed and his realization that the Senate was a fully satisfying career, in 1982 he decided not to run.[81][146][182] Kennedy campaigned hard for Democratic presidential nominee Mondale and defended vice presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro from criticism over being a pro-choice Catholic, but Reagan was re-elected in a landslide.[183]

Kennedy staged a tiring, dangerous, and high-profile trip to South Africa in 1985.[184] He defied both the apartheid government's wishes and militant leftist AZAPO demonstrators by spending a night in the Soweto home of Bishop Desmond Tutu and visited Winnie Mandela, wife of imprisoned black leader Nelson Mandela.[146][184] Upon returning, Kennedy became a leader in the push for economic sanctions against South Africa; collaborating with Senator Lowell Weicker, he secured Senate passage, and the overriding of Reagan's veto, of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.[184] Despite their many political differences, Kennedy and Reagan had a good personal relationship,[185] and with the administration's approval Kennedy traveled to the Soviet Union in 1986 to act as a go-between in arms control negotiations with reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.[146] The discussions were productive, and Kennedy helped gain the release of Soviet Jewish refuseniks, including Anatoly Shcharansky.[146][186]

Although Kennedy was an accomplished legislator, his personal life was troubled during this time.[187] His weight fluctuated wildly and he drank heavily – though not when it would interfere with his Senate duties.[187][188] Kennedy later acknowledged, "I went through a lot of difficult times over a period in my life where [drinking] may have been somewhat of a factor or force."[187] He chased women frequently,[189] and was in a series of more serious relationships but did not want to commit to anything long-term.[190] He often caroused with fellow Senator Chris Dodd;[190] twice in 1985 they were in drunken incidents in Washington restaurants, with one involving a waitress claiming the pair sexually assaulted her.[189][191] In 1987, Kennedy and a young female lobbyist were surprised in the back room of a restaurant in a state of partial undress.[81] Female Senate staffers from the late 1980s and early 1990s recalled that Kennedy was on an informal list of male Senators who were known for harassing women regularly.[192]

After again considering a candidacy for the 1988 presidential election,[81] in December 1985 Kennedy publicly declined to run. This decision was influenced by his personal difficulties, family concerns, and contentment with remaining in the Senate.[146][189] He added: "I know this decision means I may never be president. But the pursuit of the presidency is not my life. Public service is."[146] Kennedy used his legislative skills to achieve passage of the COBRA Act, which extended employer-based health benefits after leaving a job.[193][194] Following the 1986 congressional elections, the Democrats regained control of the Senate, and Kennedy became chair of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee. Kennedy had become what colleague and future President Joe Biden termed "the best strategist in the Senate".[146] Kennedy continued his close working relationship with ranking Republican Senator Orrin Hatch,[193] and they were close allies on many health-related measures.[195]

One of Kennedy's biggest battles in the Senate came with Reagan's July 1987 nomination of Judge Robert Bork to the U.S. Supreme Court.[146] Kennedy saw a possible Bork appointment as leading to a dismantling of civil rights law that he had helped put in place, and feared Bork's originalist judicial philosophy.[146] Kennedy's staff had researched Bork's writings and record, and within an hour of the nomination – which was initially expected to succeed – Kennedy went on the Senate floor to announce his opposition:

Robert Bork's America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens' doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the Government, and the doors of the Federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens ...[196]

The incendiary rhetoric of what became known as the "Robert Bork's America" speech enraged Bork supporters, who considered it slanderous, and worried some Democrats as well.[81][196][197][198] Bork responded, "There was not a line in that speech that was accurate."[199] In 1988, an analysis published in the Western Political Quarterly of amicus curiae briefs filed by U.S. Solicitors General during the Warren and Burger Courts found that during Bork's tenure in the position during the Nixon and Ford Administrations (1973–1977), Bork took liberal positions in the aggregate as often as Thurgood Marshall did during the Johnson Administration (1965–1967) and more often than Wade H. McCree did during the Carter Administration (1977–1981), in part because Bork filed briefs in favor of the litigates in civil rights cases 75 percent of the time (contradicting a previous review of his civil rights record published in 1983).[200][201]

However, the Reagan administration was unprepared for the assault, and the speech froze some Democrats from supporting the nomination and gave Kennedy and other Bork opponents time to prepare the case against him.[196][202] When the September 1987 Judiciary Committee hearings began, Kennedy challenged Bork forcefully on civil rights, privacy, women's rights, and other issues.[146] Bork's own demeanor hurt him,[196] and the nomination was defeated both in committee and the full Senate.[146] The tone of the Bork battle changed the way Washington worked – with controversial nominees or candidates now experiencing all-out war waged against them – and the ramifications of it are still being felt today.[197][202][203]

During the 1988 presidential election, Kennedy supported the eventual Democratic nominee, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis.[204] In the fall, Dukakis lost to George H. W. Bush, but Kennedy won re-election to the Senate over Republican Joseph D. Malone in the easiest race of his career.[205] Kennedy remained a powerful force in the Senate. In 1988, Kennedy co-sponsored an amendment to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibits discrimination in the rental, sale, marketing, and financing of the nation's housing; the amendment strengthened the ability of the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity to enforce the Act and expanded the protected classes to include disabled persons and families with children.[206] After prolonged negotiations during 1989 with Bush chief of staff John H. Sununu and Attorney General Richard Thornburgh to secure Bush's approval, he directed passage of the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.[193][207] Kennedy had personal interest in the bill due to his sister Rosemary's condition and his son's lost leg, and he considered its enactment one of the most important successes of his career.[193] In the late 1980s Kennedy and Hatch staged a prolonged battle against Senator Jesse Helms to provide funding to combat the AIDS epidemic and provide treatment for low-income people affected; this would culminate in passage of the Ryan White Care Act.[208] In late November 1989, Kennedy traveled to see first-hand the newly fallen Berlin Wall; he spoke at John-F.-Kennedy-Platz, site of the famous "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech in 1963, and said "Emotionally, I just wish my brother could have seen it."[209]

Early 1990s

[edit]Kennedy's personal life came to dominate his image. In 1989, paparazzi stalked him on a vacation in Europe and photographed him having sex on a motorboat.[187] In February 1990, Michael Kelly published his lengthy profile "Ted Kennedy on the Rocks" in GQ magazine.[81] It captured Kennedy as "an aging Irish boyo clutching a bottle and diddling a blonde," portrayed him as an out-of-control Regency rake, and brought his behavior to the forefront of public attention.[81][187][190] Kennedy's brother-in-law, Stephen Edward Smith, died from cancer in August 1990; Smith was a close family member and troubleshooter, and his death left Kennedy emotionally bereft.[187][210] Kennedy pushed on, but even his legislative successes, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which expanded employee rights in discrimination cases, came at the cost of being criticized for compromising with Republicans and Southern Democrats.[211]

On Easter weekend in March 1991, Kennedy was at a get-together at the family's Palm Beach, Florida, estate. After reminiscing about his brother-in-law, Kennedy was restless and maudlin when he left for a late-night visit to a local bar. He got his son Patrick and nephew William Kennedy Smith to accompany him.[187][212] Patrick and Smith returned with women they met there, Michelle Cassone and Patricia Bowman. Cassone said that Ted Kennedy subsequently walked in on her and Patrick; Ted was dressed only in a nightshirt and had a weird look on his face.[187][212] Smith and Bowman went out on the beach, where they had sex that he said was consensual but she said was rape.[187] The local police made a delayed investigation; Kennedy sources were soon feeding the press with negative information about Bowman's background, and several mainstream newspapers broke an unwritten rule by publishing her name.[212] The case quickly became a media frenzy.[187][212] While not directly implicated in the case, Kennedy became the frequent butt of jokes on The Tonight Show and other late-night television programs.[187][213] Time magazine said Kennedy was being perceived as a "Palm Beach boozer, lout and tabloid grotesque" while Newsweek said Kennedy was "the living symbol of the family flaws".[214]

Bork and Clarence Thomas were the two most contentious Supreme Court nominations in United States history to that point.[215] When the Thomas hearings began in September 1991, Kennedy pressed Thomas on his unwillingness to express an opinion about Roe v. Wade, but the nomination appeared headed for success.[216] When Anita Hill brought the sexual harassment charges against Thomas the following month, the nomination battle dominated public discourse. Kennedy was hamstrung by his past reputation and the ongoing developments in the William Kennedy Smith case.[187][217] He said almost nothing until the third day of the Thomas–Hill hearings, and when he did it was criticized by Hill supporters for being too little, too late.[187]

Biographer Adam Clymer rated Kennedy's silence during the Thomas hearings as the worst moment of his Senate career.[217] Writer Anna Quindlen said "[Kennedy] let us down because he had to; he was muzzled by the facts of his life".[217] On the day before the full Senate vote, Kennedy gave an impassioned speech against Thomas, declaring that the treatment of Hill had been "shameful" and that "[t]o give the benefit of the doubt to Judge Thomas is to say that Judge Thomas is more important than the Supreme Court."[218] He then voted against the nomination.[217] Thomas was confirmed by a 52–48 vote, one of the narrowest margins ever for a successful nomination.[217]

Due to the Palm Beach media attention and the Thomas hearings, Kennedy's public image suffered. A Gallup Poll gave Kennedy a 22 percent national approval rating.[187] A Boston Herald/WCVB-TV poll found that 62 percent of Massachusetts citizens thought Kennedy should not run for re-election, by a 2-to-1 margin thought Kennedy had misled authorities in the Palm Beach investigation, and had Kennedy losing a hypothetical Senate race to Governor William Weld by 25 points.[219] Meanwhile, at a June 17, 1991, dinner party, Kennedy saw Victoria Anne Reggie, a Washington lawyer, a divorced mother of two, and the daughter of an old Kennedy family ally, Louisiana judge Edmund Reggie.[220] They began dating and by September were in a serious relationship.[220] In a late October speech at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Kennedy sought to begin a political recovery, saying:

I am painfully aware that the criticism directed at me in recent months involves far more than disagreements with my positions ... [It] involves the disappointment of friends and many others who rely on me to fight the good fight. To them I say, I recognize my own shortcomings – the faults in the conduct of my private life. I realize that I alone am responsible for them, and I am the one who must confront them.[187]

In December 1991, the William Kennedy Smith rape trial was held; it was nationally televised and the most watched until the O. J. Simpson murder case three years later.[187] Kennedy's testimony at the trial seemed relaxed, confident, and forthcoming, and helped convince the public that his involvement had been peripheral and unintended.[221] Smith was acquitted.

Kennedy and Reggie continued their relationship, and he was said to be devoted to her two children, Curran and Caroline.[187][222] They became engaged in March 1992,[223] and were married in a civil ceremony by Judge A. David Mazzone on July 3, 1992, at Kennedy's home in McLean, Virginia.[224] She would gain credit for reportedly stabilizing his personal life and helping him resume a productive Senate career.[187][222]

Kennedy had no further presidential ambitions. Despite having initially backed former fellow Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas in the 1992 Democratic presidential primaries, Kennedy formed a good relationship with Democratic President Bill Clinton upon the latter taking office in 1993.[225] Kennedy floor-managed passage of Clinton's National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993 that created the AmeriCorps program, and despite reservations supported the president on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).[226] On the issue Kennedy cared most about, national health insurance, he supported but was not much involved in formation of the Clinton health care plan, which was run by First Lady Hillary Clinton and others.[193] It failed badly and damaged the prospects for such legislation for years to come.[193] In 1994, Kennedy's strong recommendation of his former Judiciary Committee staffer Stephen Breyer played a role in Clinton appointing Breyer to the U.S. Supreme Court.[227] During 1994 Kennedy became the first senator with a home page on the World Wide Web; the product of an effort with the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, it helped counter the image of Kennedy as old and out of touch.[228][229]

In the 1994 U.S. Senate election in Massachusetts, Kennedy faced his first serious challenger, the young, telegenic, and very well-funded Mitt Romney.[187] Romney ran as a successful entrepreneur and Washington outsider with a strong family image and moderate stands on social issues, while Kennedy was saddled not only with his recent past but the 25th anniversary of Chappaquiddick and his first wife Joan seeking a renegotiated divorce settlement.[187] By mid-September 1994, polls showed the race to be even.[187][230] Kennedy's campaign ran short on money, and belying his image as endlessly wealthy, he was forced to take out a second mortgage on his Virginia home.[231] Kennedy responded with a series of attack ads, which focused both on Romney's shifting political views and on the treatment of workers at a paper products plant owned by Romney's Bain Capital.[187][232] Kennedy's new wife Vicki proved to be a strong asset in campaigning.[230] Kennedy and Romney held a widely watched late October debate without a clear winner, but by then Kennedy had pulled ahead in polls and stayed ahead afterward.[233] In the November election, despite a very bad outcome for the Democratic Party nationally, Kennedy won re-election by a 58 percent to 41 percent margin,[234] the closest re-election race of his career.

Kennedy's mother Rose died in January 1995. From then on, Kennedy intensified the practice of his Catholic faith, often attending Mass several times a week.[235]

Late 1990s

[edit]Kennedy's role as a liberal lion in the Senate came to the fore in 1995, when (after the 1994 US House of Representatives elections) the Republican Revolution took control and legislation intending to fulfill the Contract with America was coming from Newt Gingrich's House of Representatives.[236] Many Democrats in the Senate and the United States overall felt depressed but Kennedy rallied forces to combat the Republicans.[236] By the beginning of 1996, the Republicans had overreached; most of the Contract had failed to pass the Senate and the Democrats could once again move forward with legislation, almost all of it coming out of Kennedy's staff.[237]

In 1996, Kennedy secured an increase in the minimum wage, which was one of his favorite issues;[238] there would not be another increase for ten years. Following the failure of the Clinton health care plan, Kennedy went against his past strategy and sought incremental measures instead.[239] Kennedy worked with Republican Senator Nancy Kassebaum to create and pass the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in 1996, which set new marks for portability of insurance and confidentiality of records.[193] The same year, Kennedy's Mental Health Parity Act forced insurance companies to treat mental health payments the same as others with respect to limits reached.[193] In 1997, Kennedy was the prime mover behind the State Children's Health Insurance Program,[240] which used increased tobacco taxes to fund the largest expansion of taxpayer-funded health insurance coverage for children in the U.S. since Medicaid began in the 1960s. Senator Hatch and Hillary Clinton also played major roles in SCHIP passing.[241]

Kennedy was a stalwart backer of President Clinton during the 1998 Clinton–Lewinsky scandal, often trying to cheer up the president and getting him to add past Kennedy staffer Greg Craig to his defense team, which helped improve the president's fortunes.[242] In the trial after the 1999 impeachment of Clinton, Kennedy voted to acquit Clinton on both charges, saying "Republicans in the House of Representatives, in their partisan vendetta against the President, have wielded the impeachment power in precisely the way the framers rejected, recklessly and without regard for the Constitution or the will of the American people."[243]

On July 16, 1999, Kennedy's nephew John F. Kennedy Jr. was killed when his Piper Saratoga aircraft crashed into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Martha's Vineyard. John Jr.'s wife, Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy, and his sister-in-law, Lauren Bessette, were also killed.[244] Ted was the family patriarch, and he and President Clinton consoled his extended family at the public memorial service.[244] He paraphrased W. B. Yeats by saying of his nephew: "We dared to think, in that other Irish phrase, that this John Kennedy would live to comb gray hair, with his beloved Carolyn by his side. But like his father, he had every gift but length of years."[244] The Boston Globe wrote of the changed role: "It underscored the evolution that surprised so many people who knew the Kennedys: Teddy, the baby of the family, who had grown into a man who could sometimes be dissolute and reckless, had become the steady, indispensable patriarch, the one the family turned to in good times and bad."[244]

2000s

[edit]

Kennedy had an easy time with his re-election to the Senate in 2000, as Republican lawyer and entrepreneur Jack E. Robinson III was sufficiently damaged by his past personal record that Republican state party officials refused to endorse him.[245] Kennedy got 73 percent of the general election vote, with Robinson splitting the rest with Libertarian Carla Howell. During the long, disputed post-presidential election battle in Florida in 2000, Kennedy supported Vice President Al Gore's legal actions.[246] After the bitter contest, many Democrats in Congress did not want to work with incoming President George W. Bush.[193] Kennedy, however, saw Bush as genuinely interested in a major overhaul of education, Bush saw Kennedy as a potential major ally in the Senate, and the two partnered together on the legislation.[193][247] Kennedy accepted provisions governing mandatory student testing and teacher accountability that other Democrats and the National Education Association did not like, in return for increased funding levels for education.[193] The No Child Left Behind Act was passed by Congress in May and June 2001 and signed into law by Bush in January 2002. Kennedy soon became disenchanted with the implementation of the act, however, saying for 2003 that it was $9 billion short of the $29 billion authorized.[193] Kennedy said, "The tragedy is that these long overdue reforms are finally in place, but the funds are not,"[247] and accused Bush of not living up to his personal word on the matter.[193][211] Other Democrats concluded that Kennedy's penchant for cross-party deals had gotten the better of him.[193] The White House defended its spending levels given the context of two wars[248] going on.[193]

Kennedy was in his Senate offices meeting with First Lady Laura Bush when the September 11, 2001, attacks took place.[244] Two of the airplanes involved had taken off from Boston, and Kennedy telephoned each of the 177 Massachusetts families who had lost members in the attacks.[244] He pushed through legislation that provided healthcare and grief counseling benefits for the families, and recommended the appointment of his former chief of staff Kenneth Feinberg as Special Master of the government's September 11th Victim Compensation Fund.[244] Kennedy maintained an ongoing bond with the Massachusetts 9/11 families in subsequent years.[244][249]

Kennedy was a supporter of the American-led 2001 overthrow of the Taliban government in Afghanistan. However, Kennedy strongly opposed the Iraq War from the start, and was one of 23 senators voting against the Iraq War Resolution in October 2002.[244] As the Iraqi insurgency grew in subsequent years, Kennedy pronounced that the conflict was "Bush's Vietnam."[244] In response to losses of Massachusetts service personnel to roadside bombs, Kennedy became vocal on the issue of Humvee vulnerability, and co-sponsored enacted 2005 legislation that sped up production and Army procurement of up-armored Humvees.[244]

Despite the strained relationship between Kennedy and Bush over 'No Child Left Behind' spending, the two attempted to work together again on extending Medicare to cover prescription drug benefits.[193] Kennedy's strategy was again doubted by other Democrats, but he saw the proposed $400 billion program as an opportunity that should not be missed.[193] However, when the final formulation of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act contained provisions to steer seniors towards private plans, Kennedy switched to opposing it.[193] It passed in late 2003, and led Kennedy to again say he had been betrayed by the Bush administration.[193]

In the 2004 Democratic Party presidential primaries, Kennedy campaigned heavily for fellow Massachusetts Senator John Kerry[244] and lent his chief of staff, Mary Beth Cahill, to the Kerry campaign. Kennedy's appeal was effective among blue collar and minority voters, and helped Kerry stage a come-from-behind win in the Iowa caucuses that propelled him on to the Democratic nomination.[244]

After Bush won a second term in the 2004 general election, Kennedy continued to oppose him on Iraq and many other issues.[115][193] However, Kennedy sought to partner with Republicans again on the matter of immigration reform in the context of the ongoing United States immigration debate.[193] Kennedy was chair of the United States Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Border Security, and Refugees, and in 2005, Kennedy teamed with Republican Senator John McCain on the Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act. The "McCain-Kennedy bill" did not reach a Senate vote, but provided a template for further attempts at dealing comprehensively with legalization, guest worker programs, and border enforcement components. Kennedy returned again with the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, which was sponsored by an ideologically diverse, bipartisan group of senators[250] and had strong support from the Bush administration.[193] The bill aroused furious grassroots opposition among talk radio listeners and others as an "amnesty" program,[251] and despite Kennedy's last-minute attempts to salvage it, failed a cloture vote in the Senate.[252] Kennedy was philosophical about the defeat, saying that it often took several attempts across multiple Congresses for this type of legislation to build enough momentum for passage.[193]

In 2006, Kennedy released a children's book from the view of his dog Splash, My Senator and Me: A Dog's-Eye View of Washington, D.C.[253] Also in 2006, Kennedy released a political history entitled America Back on Track.[254]

In 2006, a Cessna Citation 550 in which Kennedy was flying lost electrical power after being struck by lightning and had to be diverted.[255]

In November 2006, Kennedy again easily won re-election to the Senate, winning 69 percent of the vote against Republican language school owner Kenneth Chase, who suffered from very poor name recognition.[256]

Obama, illness

[edit]

Kennedy initially stated that he would support John Kerry again if he were to make another bid for president in 2008, but in January 2007, Kerry said he would not make a second attempt for the White House.[257] Kennedy then remained neutral as the 2008 Democratic nomination battle between Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama intensified, because his friend Chris Dodd was also running for the nomination.[258] The initial caucuses and primaries were split between Clinton and Obama. When Dodd withdrew from the race, Kennedy became dissatisfied with the tone of the Clinton campaign and what he saw as racially tinged remarks by Bill Clinton.[258][259] Kennedy gave an endorsement to Obama on January 28, 2008, despite appeals by both Clintons not to do so.[260] In a move that was seen as a symbolic passing of the torch,[244] Kennedy said that it was "time again for a new generation of leadership," and compared Obama's ability to inspire with that of his fallen brothers.[259] In return, Kennedy gained a commitment from Obama to make universal health care a top priority of his administration if he were elected.[258] Kennedy's endorsement was considered among the most influential that any Democrat could get,[261] and raised the possibility of improving Obama's vote-getting among unions, Hispanics, and traditional base Democrats.[260] It dominated the political news, and gave national exposure to a candidate who was still not well known in much of the USA, as the Super Tuesday primaries across the nation approached.[258][262]

On May 17, 2008, Kennedy suffered a seizure, which was followed by a second seizure as he was being rushed from the Kennedy Compound to Cape Cod Hospital and then by helicopter to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.[263] Within days, doctors announced that Kennedy had a malignant glioma, a type of brain tumor.[264] The grim diagnosis[264][265][266] brought shocked reactions from many senators of both parties and from President Bush.[264]

Doctors initially informed Kennedy that the tumor was inoperable, but Kennedy followed standard procedure and sought other opinions. He decided to follow the most aggressive course of treatment possible.[265] On June 2, 2008, Kennedy underwent brain surgery at Duke University Medical Center in an attempt to remove as much of the tumor as possible.[267][268] The 3½-hour operation—conducted by Dr. Allan Friedman while Kennedy was conscious to minimize any permanent neurological effects—was deemed successful.[267][268] Kennedy left the hospital a week later to begin a course of chemotherapy and radiation treatment.[269] Opinions varied regarding Kennedy's prognosis: the surgery typically extends survival time for only a few months, but people can sometimes live for years.[268][270]

The operation and follow-up treatments left Kennedy thinner, prone to additional seizures, weak and short on energy, and hurt his balance.[265] Kennedy made his first post-illness public appearance on July 9, when he surprised the Senate by showing up to supply the added vote to break a Republican filibuster against a bill to preserve Medicare fees for doctors.[271] In addition, Kennedy was ill from an attack of kidney stones. Against the advice of some associates,[272][273] he insisted on appearing during the first night of the 2008 Democratic National Convention on August 25, 2008, where a video tribute to him was played. Introduced by his niece Caroline Kennedy, the senator said, "It is so wonderful to be here. Nothing – nothing – is going to keep me away from this special gathering tonight."[244] He then delivered a speech to the delegates (which he had to memorize, as his impaired vision left him unable to read a teleprompter)[235] in which, reminiscent of his speech at the 1980 Democratic National Convention, he said, "this November, the torch will be passed again to a new generation of Americans. So, with Barack Obama and for you and for me, our country will be committed to his cause. The work begins anew. The hope rises again. And the dream lives on."[274] The dramatic appearance and speech electrified the convention audience,[244][273][275] as Kennedy vowed that he would be present to see Obama inaugurated.[276]

On September 26, 2008, Kennedy suffered a mild seizure while at home in Hyannis Port; he immediately went to the hospital, was examined and released later that same day. Doctors believed that a change in his medication triggered the seizure.[275] Kennedy relocated to Florida for the winter; he continued his treatments, did a lot of sailing, and stayed in touch with legislative matters via telephone.[265] In his absence, many senators wore blue "Tedstrong" bracelets.[265]

On January 20, 2009, Kennedy attended Barack Obama's presidential inauguration, but then suffered a seizure at the luncheon immediately afterwards. He was taken by ambulance to MedStar Washington Hospital Center.[277] Doctors attributed the episode to "simple fatigue". He was released from the hospital the following morning, and he returned to his home in Washington, D.C.[278]

When the 111th Congress began, Kennedy dropped his spot on the Senate Judiciary Committee to focus all his attentions on national health care issues, which he regarded as "the cause of my life".[265][279][280] He saw the characteristics of the Obama administration and the Democratic majorities in Congress as representing the third and best great chance for universal health care, following the lost 1971 Nixon and 1993 Clinton opportunities,[281] and as his last big legislative battle.[265] Kennedy made another surprise appearance in the Senate to break a Republican filibuster against the Obama stimulus package.[282] When spring arrived, Kennedy appeared on Capitol Hill more frequently, although staffers often did not announce his attendance at committee meetings until they were sure Kennedy was well enough to appear.[265] On March 4, 2009, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Gordon Brown announced that Kennedy had been granted an honorary knighthood by Queen Elizabeth II for his work in the Northern Ireland peace process, and for his contribution to UK–US relations,[283][284] although the move caused some controversy in the UK due to his connections with Gerry Adams of the Irish republican political party Sinn Féin.[285] Later in March, a bill reauthorizing and expanding the AmeriCorps program was renamed the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act by Senator Hatch in Kennedy's honor.[286] Kennedy threw the ceremonial first pitch at Fenway Park before the Boston Red Sox season opener in April, echoing what his grandfather "Honey Fitz" – a member of the Royal Rooters – had done to open the park in 1912.[287] Even when his illness prevented him from being a major factor in health plan deliberations, his symbolic presence still made him one of the key senators involved.[288]