Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (July 2025) |

Key Information

Uruk, the archeological site known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East or West Asia, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river in Muthanna Governorate, Iraq. The site lies 93 kilometers (58 miles) northwest of ancient Ur, 108 kilometers (67 miles) southeast of ancient Nippur, and 24 kilometers (15 miles) northwest of ancient Larsa. It is 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah.[1]

Uruk is the type site for the Uruk period. Uruk played a leading role in the early urbanization of Sumer in the mid-4th millennium BC. By the final phase of the Uruk period around 3100 BC, the city may have had 40,000 residents,[2] with 80,000–90,000 people living in its environs,[3] making it the largest urban area in the world at the time. Gilgamesh, according to the chronology presented in the Sumerian King List (SKL), ruled Uruk in the 27th century BC. After the end of the Early Dynastic period, with the rise of the Akkadian Empire, the city lost its prime importance. It had periods of florescence during the Isin-Larsa period, Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian periods and throughout the Achaemenid (550–330 BC), Seleucid (312–63 BC) and Parthian (227 BC to AD 224) periods, until it was finally abandoned shortly before or after the Islamic conquest of 633–638.

William Kennett Loftus visited the site of Uruk in 1849, identifying it as "Erech", known as "the second city of Nimrod", and led the first excavations from 1850 to 1854.[4] In myth and literature, Uruk was famous as the capital city of Gilgamesh, hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Biblical scholars identify Uruk as the biblical Erech (Genesis 10:10), the second city founded by Nimrod in Shinar.[5]

Toponymy

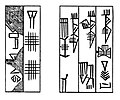

[edit]Uruk (/ˈʊrʊk/) has several spellings in cuneiform; in Sumerian it is 𒀕𒆠 unugᵏⁱ;[6] in Akkadian, 𒌷𒀕 or 𒌷𒀔 Uruk (URUUNUG). Its names in other languages include: Arabic: وركاء or أوروك, Warkāʾ or Auruk; Classical Syriac: ܐܘܿܪܘܿܟ, ʾÚrūk; Biblical Hebrew: אֶרֶךְ ʾÉreḵ; Ancient Greek: Ὀρχόη, romanized: Orkhóē, Ὀρέχ Orékh, Ὠρύγεια Ōrúgeia.

History

[edit]

According to the SKL, Uruk was founded by the king Enmerkar. Though the king-list mentions a father before him, the epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta relates that Enmerkar constructed the House of Heaven (Sumerian: e₂-anna; cuneiform: 𒂍𒀭 E₂.AN) for the goddess Inanna in the Eanna District of Uruk. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh builds the city wall around Uruk and is king of the city.

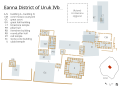

Uruk went through several phases of growth, from the Early Uruk period (4000–3500 BC) to the Late Uruk period (3500–3100 BC).[1] The city was formed when two smaller Ubaid settlements developed into the cities of Unug and Kullaba and later merged to become Uruk. The temple complexes at their cores became the Eanna District (Unug) dedicated to Inanna and the "Anu" District of Kullaba.[1]

The Eanna District was composed of several buildings with spaces for workshops, and it was walled off from the city. By contrast, the Anu District was built on a terrace with a temple at the top. It is clear Eanna was dedicated to Inanna from the earliest Uruk period throughout the history of the city.[7] The rest of the city was composed of typical courtyard houses, grouped by profession of the occupants, in districts around Eanna and Anu. Uruk was extremely well penetrated by a canal system that has been described as "Venice in the desert".[8] This canal system flowed throughout the city connecting it with the maritime trade on the ancient Euphrates River as well as the surrounding agricultural belt.

The original city of Uruk was situated southwest of the ancient Euphrates River, now dry. Currently, the site of Warka is northeast of the modern Euphrates river. The change in position was caused by a shift in the Euphrates at some point in history, which, together with salination due to irrigation, may have contributed to the decline of Uruk.

Uruk period

[edit]

In addition to being one of the first cities, Uruk was the main force of urbanization and state formation during the Uruk period, or 'Uruk expansion' (4000–3200 BC). This period of 800 years saw a shift from small, agricultural villages to a larger urban center with a full-time bureaucracy, military, and stratified society. Although other settlements coexisted with Uruk, they were generally about 10 hectares while Uruk was significantly larger and more complex. The Uruk period culture exported by Sumerian traders and colonists had an effect on all surrounding peoples, who gradually evolved their own comparable, competing economies and cultures. Ultimately, Uruk could not maintain long-distance control over colonies such as Tell Brak by military force.

Early Dynastic, Akkadian, Ur III, and Old Babylonian period

[edit]

Dynastic categorizations are described solely from the Sumerian King List, which is of problematic historical accuracy;[9][10] the organization might be analogous to Manetho's.

In 2009, two different copies of an inscription were put forth as evidence of a 19th-century BC ruler of Uruk named Naram-sin.[11]

Uruk continued as principality of Ur, Babylon, and later Achaemenid, Seleucid, and Parthian Empires. It enjoyed brief periods of independence during the Isin-Larsa period, under kings such as (possibly Ikūn-pî-Ištar, Sumu-binasa, Alila-hadum, and Naram-Sin), Sîn-kāšid, his son Sîn-irībam, his son Sîn-gāmil, Ilum-gāmil, brother of Sîn-gāmil, Etēia, AN-am3 (Dingiram), ÌR3-ne-ne (Irdanene), who was defeated by Rīm-Sîn I of Larsa in his year 14 (c. 1740 BC), Rîm-Anum and Nabi-ilīšu.[12][11][13][14][15]

It is known that during the time of Ilum-gāmil a temple was built for the god Iškur (Hadad) based on a clay cone inscription reading "For the god Iškur, lord, fearsome splendour of heaven and earth, his lord, for the life of Ilum-gāmil, king of Uruk, son of Sîn-irībam, Ubar-Adad, his servant, son of Apil-Kubi, built the Esaggianidu, ('House — whose closing is good'), the residence of his office of en, and thereby made it truly befitting his own li[fe]".[12]

Uruk into Late Antiquity

[edit]

Although it had been a thriving city in Early Dynastic Sumer, especially Early Dynastic II, Uruk was ultimately annexed by the Akkadian Empire and went into decline. Later, in the Neo-Sumerian period, Uruk enjoyed revival as a major economic and cultural center under the sovereignty of Ur. The Eanna District was restored as part of an ambitious building program, which included a new temple for Inanna. This temple included a ziggurat, the 'House of the Universe' (Cuneiform: E₂.SAR.A) (𒂍𒊬𒀀) to the northeast of the Uruk period Eanna ruins.

Following the collapse of Ur (c. 2000 BC), Uruk went into a steep decline until about 850 BC when the Neo-Assyrian Empire annexed it as a provincial capital. Under the Neo-Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians, Uruk regained much of its former glory. By 250 BC, a new temple complex the 'Head Temple' (Akkadian: Bīt Reš) was added to northeast of the Uruk period Anu district. The Bīt Reš along with the Esagila was one of the two main centers of Neo-Babylonian astronomy. All of the temples and canals were restored again under Nabopolassar. During this era, Uruk was divided into five main districts: the Adad Temple, Royal Orchard, Ištar Gate, Lugalirra Temple, and Šamaš Gate districts.[16]

Uruk, known as Orcha (Ὄρχα) to the Greeks, continued to thrive under the Seleucid Empire. During this period, Uruk was a city of 300 hectares and perhaps 40,000 inhabitants.[16][17][18] In 200 BC, the 'Great Sanctuary' (Cuneiform: E₂.IRI₁₂.GAL, Sumerian: eš-gal) of Ishtar was added between the Anu and Eanna districts. The ziggurat of the temple of Anu, which was rebuilt in this period, was the largest ever built in Mesopotamia.[18] When the Seleucids lost Mesopotamia to the Parthians in 141 BC, Uruk continued in use.[19] The decline of Uruk after the Parthians may have been in part caused by a shift in the Euphrates River. By 300 AD, Uruk was mostly abandoned, but a group of Mandaeans settled there, based on some finds of Mandaic incantation bowls, and by c. 700 AD it was completely abandoned.[20]

Political history

[edit]

Uruk played a very important part in the political history of Sumer. Starting from the Early Uruk period, the city exercised hegemony over nearby settlements. At this time (c. 3800 BC), there were two centers of 20 ha (49 acres), Uruk in the south and Nippur in the north surrounded by much smaller 10 ha (25 acres) settlements.[23] Later, in the Late Uruk period, its sphere of influence extended over all Sumer and beyond to external colonies in upper Mesopotamia and Syria.

In Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia, Sumerian civilization seems to have reached its creative peak. This is pointed out repeatedly in the references to this city in religious and, especially, in literary texts, including those of mythological content; the historical tradition as preserved in the Sumerian king-list confirms it. From Uruk the center of political gravity seems to have moved to Ur.

— Oppenheim[24]

The recorded chronology of rulers over Uruk includes both mythological and historic figures in five dynasties. As in the rest of Sumer, power moved progressively from the temple to the palace. Rulers from the Early Dynastic period exercised control over Uruk and at times over all of Sumer. In myth, kingship was lowered from heaven to Eridu then passed successively through five cities until the deluge which ended the Uruk period. Afterwards, kingship passed to Kish at the beginning of the Early Dynastic period, which corresponds to the beginning of the Early Bronze Age in Sumer. In the Early Dynastic I period (2900–2800 BC), Uruk was in theory under the control of Kish. This period is sometimes called the Golden Age. During the Early Dynastic II period (2800–2600 BC), Uruk was again the dominant city exercising control of Sumer. This period is the time of the First Dynasty of Uruk sometimes called the Heroic Age. However, by the Early Dynastic IIIa period (2600–2500 BC) Uruk had lost sovereignty, this time to Ur. This period, corresponding to the Early Bronze Age III, is the end of the First Dynasty of Uruk. In the Early Dynastic IIIb period (2500–2334 BC), also called the Pre-Sargonic period (before the rise of the Akkadian Empire under Sargon of Akkad), Uruk continued to be ruled by Ur.

Architecture

[edit]

Uruk has some of the first monumental constructions in architectural history, and certainly the largest of its era. Much of Near Eastern architecture can trace its roots to these prototypical buildings. The structures of Uruk are cited by two different naming conventions, one in German from the initial expedition, and the English translation of the same. The stratigraphy of the site is complex and as such much of the dating is disputed. In general, the structures follow the two main typologies of Sumerian architecture, Tripartite with 3 parallel halls and T-Shaped also with three halls, but the central one extends into two perpendicular bays at one end. The following table summarizes the significant architecture of the Eanna and Anu Districts.[26] Temple N, Cone-Mosaic Courtyard, and Round Pillar Hall are often referred to as a single structure; the Cone-Mosaic Temple.

| Eanna district: 4000–3000 BC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure name | German name | Period | Typology | Material | Area in m² | |

| Stone-Cone Temple | Steinstifttempel | Uruk VI | T-shaped | Limestone and bitumen | x | |

| Limestone Temple | Kalksteintempel | Uruk V | T-shaped | Limestone and bitumen | 2373 | |

| Riemchen Building | Riemchengebäude | Uruk IVb | unique | Adobe brick | x | |

| Cone-Mosaic Temple | Stiftmosaikgebäude | Uruk IVb | unique | x | x | |

| Temple A | Gebäude A | Uruk IVb | Tripartite | Adobe brick | 738 | |

| Temple B | Gebäude B | Uruk IVb | Tripartite | Adobe brick | 338 | |

| Temple C | Gebäude C | Uruk IVb | T-shaped | Adobe brick | 1314 | |

| Temple/Palace E | Gebäude E | Uruk IVb | unique | Adobe brick | 2905 | |

| Temple F | Gebäude F | Uruk IVb | T-shaped | Adobe brick | 465 | |

| Temple G | Gebäude G | Uruk IVb | T-shaped | Adobe brick | 734 | |

| Temple H | Gebäude H | Uruk IVb | T-shaped | Adobe brick | 628 | |

| Temple D | Gebäude D | Uruk IVa | T-shaped | Adobe brick | 2596 | |

| Room I | Gebäude I | Uruk V | x | x | x | |

| Temple J | Gebäude J | Uruk IVb | x | Adobe brick | x | |

| Temple K | Gebäude K | Uruk IVb | x | Adobe brick | x | |

| Temple L | Gebäude L | Uruk V | x | x | x | |

| Temple M | Gebäude M | Uruk IVa | x | Adobe brick | x | |

| Temple N | Gebäude N | Uruk IVb | unique | Adobe brick | x | |

| Temple O | Gebäude O | x | x | x | x | |

| Hall Building/Great Hall | Hallenbau | Uruk IVa | unique | Adobe brick | 821 | |

| Pillar Hall | Pfeilerhalle | Uruk IVa | unique | x | 219 | |

| Bath Building | Bäder | Uruk III | unique | x | x | |

| Red Temple | Roter Tempel | Uruk IVa | x | Adobe brick | x | |

| Great Court | Großer Hof | Uruk IVa | unique | Burnt Brick | 2873 | |

| Rammed-Earth Building | Stampflehm | Uruk III | unique | x | x | |

| Round Pillar Hall | Rundpeifeilerhalle | Uruk IVb | unique | Adobe brick | x | |

| Anu district: 4000–3000 BC | ||||||

| Stone Building | Steingebäude | Uruk VI | unique | Limestone and bitumen | x | |

| White Temple | x | Uruk III | Tripartite | Adobe brick | 382 | |

It is clear Eanna was dedicated to Inanna symbolized by Venus from the Uruk period. At that time, she was worshipped in four aspects as Inanna of the netherworld (Sumerian: ᵈinanna-kur), Inanna of the morning (Sumerian: ᵈinanna-hud₂), Inanna of the evening (Sumerian: ᵈinanna-sig), and Inanna (Sumerian: ᵈinanna-NUN).[7] The names of four temples in Uruk at this time are known, but it is impossible to match them with either a specific structure and in some cases a deity.[7]

- sanctuary of Inanna (Sumerian: eš-ᵈinanna)

- sanctuary of Inanna of the evening (Sumerian: eš-ᵈinanna-sig)

- temple of heaven (Sumerian: e₂-an)

- temple of heaven and netherworld (Sumerian: e₂-an-ki)

- Architecture of Uruk

-

Plan of Eanna VI–V

-

Plan of Eanna IVb

-

Plan of Eanna IVa

-

Plan of Eanna III

-

Plan of Neo-Sumerian Eanna

-

Plan of Anu District Phase E

-

Reconstruction of a mosaic from the Eanna temple.

-

Detail of Reconstruction of a mosaic from the Eanna temple.

Archaeology

[edit]

By the end of the Uruk period c. 3100 BC) Uruk had reached a size of 250 ha (620 acres). During the following Jemdet Nasr period it grew to a size of 600 ha (1,500 acres) by c. 2800 BC with the main temple area of Eanna being completely rebuilt after leveling the foundations of the Uruk period construction.[27] A new city wall was constructed in this period.[28]

The site, which lies about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of ancient Ur, is one of the largest in the region at around 5.5 km2 (2.1 sq mi) in area. The maximum extent is 3 km (1.9 miles) north/south, and 2.5 km (1.6 miles) east/west. There are three major tells within the site: The Eanna district, Bit Resh (Kullaba), and Irigal. Archaeologically, the site is divided into six parts

- the É-Anna ziggurat ' Egipar-imin,

- the É-Anna enclosure (Zingel),

- the Anu-Antum temple complex, BitRes and Anu-ziggurat,

- Irigal, the South Building,

- Parthian structures including the Gareus-temple, and the Multiple Apse building,

- the "Gilgameš" city-wall with associated Sinkâsid Palace and the Seleucid Bit Akîtu.[29]

The location of Uruk was first noted by Fraser and Ross in 1835.[30] William Loftus excavated there in 1850 and 1854 after a scouting mission in 1849. By Loftus' own account, he admits that the first excavations were superficial at best, as his financiers forced him to deliver large museum artifacts at a minimal cost.[4] A large basalt stela found by Loftus was later lost.[31] Warka was also scouted by archaeologist Walter Andrae in 1902.[32] In 1905 Warka was visited by archaeologist Edgar James Banks.[33]

From 1912 to 1913, Julius Jordan and his team from the German Oriental Society discovered the temple of Ishtar, one of four known temples located at the site. The temples at Uruk were quite remarkable as they were constructed with brick and adorned with colorful mosaics. Jordan also discovered part of the city wall. It was later discovered that this 40-to-50-foot (12 to 15 m) high brick wall, probably utilized as a defense mechanism, totally encompassed the city at a length of 9 km (5.6 mi). Utilizing sedimentary strata dating techniques, this wall is estimated to have been erected around 3000 BC. Jordan produced a contour map of the entire site.[28] The GOS returned to Uruk in 1928 and excavated until 1939, when World War II intervened. The team was led by Jordan until 1931 when Jordan became Director of Antiquities in Baghdad, then by A. Nöldeke, Ernst Heinrich, and H. J. Lenzen.[34][35] Among the finds was the Stell of the Lion Hunt, excavated in a Jemdat Nadr layer but sylistically dated to Uruk IV.[36]

The German excavations resumed after the war and were under the direction of Heinrich Lenzen from 1954 to 1967.[37][38][39] He was followed in 1968 by J. Schmidt, and in 1978 by R.M. Boehmer.[40][41] In total, the German archaeologists spent 39 seasons working at Uruk. The results are documented in two series of reports:

- Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk (ADFU), 17 volumes, 1912–2001

- Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka, Endberichte (AUWE), 25 volumes, 1987–2007

Most recently, from 2001 to 2002, the German Archaeological Institute team led by Margarete van Ess, with Joerg Fassbinder and Helmut Becker, conducted a partial magnetometer survey in Uruk. In addition to the geophysical survey, core samples and aerial photographs were taken. This was followed up with high-resolution satellite imagery in 2005.[42] Work resumed in 2016 and is currently concentrated on the city wall area and a survey of the surrounding landscape.[43][44][45] Part of the work has been to create a digital twin of the Uruk archaeological area.[46] The current effort also involves geophysical surveying. The soil characteristics of the site make ground penetrating radar unsuitable so caesium magnetometers, combined with resistivity probes, are being used.[47]

Cuneiform tablets

[edit]

A number of Proto-cuneiform clay tablets were found at Uruk. About 190 were Uruk V period (c. 3500 BC) "numerical tablets" or "impressed tablets", 1776 were from the Uruk IV period (c. 3300 BC), 3094 from the Uruk III period (c. 3200–2900 BC) which is also called the Jemdet Nasr period.[48][49] Later cuneiform tablets were deciphered and include the famous SKL, a record of kings of the Sumerian civilization. There was an even larger cache of legal and scholarly tablets of the Neo-Babylonian, Late Babylonian, and Seleucid period, that have been published by Adam Falkenstein and other Assyriological members of the German Archaeological Institute in Baghdad as Jan J. A. Djik,[50] Hermann Hunger, Antoine Cavigneaux, Egbert von Weiher,[51][52][53][54] and Karlheinz Kessler, or others as Erlend Gehlken.[55][56][57] Many of the cuneiform tablets form acquisitions by museums and collections as the British Museum, Yale Babylonian Collection, and the Louvre. The latter holds a unique cuneiform tablet in Aramaic known as the Aramaic Uruk incantation. The last dated cuneiform tablet from Uruk was W22340a, an astronomical almanac, which is dated to 79/80 AD.[58]

The oldest known writing to feature a person's name was found in Uruk, in the form of several tablets that mention Kushim, who (assuming they are an individual person) served as an accountant recording transactions made in trading barley – 29,086 measures barley 37 months Kushim.[59][60]

Beveled rim bowls were the most common type of container used during the Uruk period. They are believed to be vessels for serving rations of food or drink to dependent laborers. The introduction of the fast wheel for throwing pottery was developed during the later part of the Uruk period, and made the mass production of pottery simpler and more standardized.[61]

Artifacts

[edit]The Mask of Warka, also known as the 'Lady of Uruk' and the 'Sumerian Mona Lisa', dating from 3100 BC, is one of the earliest representations of the human face. The carved marble female face is probably a depiction of Inanna. It is approximately 20 cm (7.9 in) tall, and may have been incorporated into a larger cult image. The mask was looted from the Iraq Museum during the invasion of Iraq in April 2003. It was recovered in September 2003 and returned to the museum.

-

Lugal-kisalsi, king of Uruk

-

Mask of Warka

-

Bull sculpture, Jemdet Nasr period, c. 3000 BC

-

Stele of the Lion Hunt – Uruk period

Archaeological levels of Uruk

[edit]Archeologists have discovered multiple cities of Uruk built atop each other in chronological order.[26]

- Uruk XVIII Eridu period (c. 5000 BC): the founding of Uruk

- Uruk XVIII–XVI Late Ubaid period (4800–4200 BC)

- Uruk XVI–X Early Uruk period (4000–3800 BC)

- Uruk IX–VI Middle Uruk period (3800–3400 BC)

- Uruk V–IV Late Uruk period (3400–3100 BC): the earliest monumental temples of Eanna District are built

- Uruk III Jemdet Nasr period (3100–2900 BC): the 9 km city wall is built

- Uruk II

- Uruk I

Anu District

[edit]The area traditionally called the Anu district consists of a single massive terrace, the Anu ziggurat, originally proposed to have been dedicated to the Sumerian sky god Anu.

The Stone Temple was built of limestone and bitumen on a podium of rammed earth and plastered with lime mortar. The podium itself was built over a woven reed mat called ĝipar, which was ritually used as a nuptial bed. The ĝipar was a source of generative power which then radiated upward into the structure. The structure of the Stone Temple further develops some mythological concepts from Enuma Elish, perhaps involving libation rites as indicated from the channels, tanks, and vessels found there. The structure was ritually destroyed, covered with alternating layers of clay and stone, then excavated and filled with mortar sometime later.

Eanna District

[edit]

The Eanna district is historically significant as both writing and monumental public architecture emerged here during Uruk periods VI–IV. The combination of these two developments places Eanna as arguably the first true city and civilization in human history. Eanna during period IVa contains the earliest examples of writing.[62]

The first building of Eanna, Stone-Cone Temple (Mosaic Temple), was built in period VI over a preexisting Ubaid temple and is enclosed by a limestone wall with an elaborate system of buttresses. The Stone-Cone Temple, named for the mosaic of colored stone cones driven into the adobe brick façade, may be the earliest water cult in Mesopotamia. It was "destroyed by force" in Uruk IVb period and its contents interred in the Riemchen Building.[38]

In the following period, Uruk V, about 100 m east of the Stone-Cone Temple the Limestone Temple was built on a 2 m high rammed-earth podium over a pre-existing Ubaid temple, which like the Stone-Cone Temple represents a continuation of Ubaid culture. However, the Limestone Temple was unprecedented for its size and use of stone, a clear departure from traditional Ubaid architecture. The stone was quarried from an outcrop at Umayyad about 60 km east of Uruk. It is unclear if the entire temple or just the foundation was built of this limestone. The Limestone Temple is probably the first Inanna temple, but it is impossible to know with certainty. Like the Stone-Cone temple the Limestone temple was also covered in cone mosaics. Both of these temples were rectangles with their corners aligned to the cardinal directions, a central hall flanked along the long axis by two smaller halls, and buttressed façades; the prototype of all future Mesopotamian temple architectural typology.

Between these two monumental structures a complex of buildings (called A–C, E–K, Riemchen, Cone-Mosaic), courts, and walls was built during Eanna IVb. These buildings were built during a time of great expansion in Uruk as the city grew to 250 ha (620 acres) and established long-distance trade, and are a continuation of architecture from the previous period. The Riemchen Building, named for the 16 cm (6.3 in)×16 cm (6.3 in) brick shape called Riemchen by the Germans, is a memorial with a ritual fire kept burning in the center for the Stone-Cone Temple after it was destroyed. For this reason, Uruk IV period represents a reorientation of belief and culture. The facade of this memorial may have been covered in geometric and figural murals. The Riemchen bricks first used in this temple were used to construct all buildings of Uruk IV period Eanna. The use of colored cones as a façade treatment was greatly developed as well, perhaps used to greatest effect in the Cone-Mosaic Temple. Composed of three parts: Temple N, the Round Pillar Hall, and the Cone-Mosaic Courtyard, this temple was the most monumental structure of Eanna at the time. They were all ritually destroyed and the entire Eanna district was rebuilt in period IVa at an even grander scale.

During Eanna IVa, the Limestone Temple was demolished and the Red Temple built on its foundations. The accumulated debris of the Uruk IVb buildings were formed into a terrace, the L-Shaped Terrace, on which Buildings C, D, M, Great Hall, and Pillar Hall were built. Building E was initially thought to be a palace, but later proven to be a communal building. Also in period IV, the Great Court, a sunken courtyard surrounded by two tiers of benches covered in cone mosaic, was built. A small aqueduct drains into the Great Courtyard, which may have irrigated a garden at one time. The impressive buildings of this period were built as Uruk reached its zenith and expanded to 600 hectares. All the buildings of Eanna IVa were destroyed sometime in Uruk III, for unclear reasons.[citation needed]

The architecture of Eanna in period III was very different from what had preceded it. The complex of monumental temples was replaced with baths around the Great Courtyard and the labyrinthine Rammed-Earth Building. This period corresponds to Early Dynastic Sumer c. 2900 BC, a time of great social upheaval when the dominance of Uruk was eclipsed by competing city-states. The fortress-like architecture of this time is a reflection of that turmoil. The temple of Inanna continued functioning during this time in a new form and under a new name, 'The House of Inanna in Uruk' (Sumerian: e₂-ᵈinanna unuᵏⁱ-ga). The location of this structure is currently unknown.[7]

List of rulers

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2024) |

The Sumerian King List (SKL) lists only 22 rulers among five dynasties of Uruk. The sixth dynasty was an Amorite dynasty not mentioned on the SKL. The following list should not be considered complete:

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic I period (c. 2900 – c. 2700 BC) | ||||||

| First dynasty of Uruk / Uruk I dynasty (c. 2900 – c. 2700 BC) | ||||||

— Sumerian King List (SKL) | ||||||

| 1st |

|

Meshkiangasher 𒈩𒆠𒉘𒂵𒊺𒅕 |

Son of Utu | reigned c. 2775 BC (324 years) |

| |

— SKL | ||||||

| 2nd |

|

Enmerkar 𒂗𒈨𒅕𒃸 |

Son of Meshkiangasher | "the king of Uruk, who built Uruk" | r. c. 2750, c. 2730 BC (420 years) |

|

| 3rd |

|

Lugalbanda 𒈗𒌉𒁕 |

"the shepherd" | r. c. 2700 BC (1,200 years) |

| |

| 4th |

|

Dumuzid 𒌉𒍣𒋗𒄩 |

"the fisherman whose city was Kuara" | r. c. 2700 BC (110 years) |

| |

| Early Dynastic II period (c. 2700 – c. 2600 BC) | ||||||

| 5th |

|

Gilgamesh 𒀭𒄑𒉋𒂵𒈨𒌋𒌋𒌋 |

Son of Lugalbanda (?) | "the lord of Kulaba" | r. c. 2700, c. 2670, c. 2650 BC (126 years) |

|

| 6th |

|

Ur-Nungal 𒌨𒀭𒉣𒃲 |

Son of Gilgamesh | r. c. 2650 – c. 2620 BC (30 years) |

| |

| 7th | Udul-kalama 𒌋𒊨𒌦𒈠 |

Son of Ur-Nungal | r. c. 2620 – c. 2605 BC (15 years) |

| ||

| 8th |

|

La-ba'shum 𒆷𒁀𒀪𒋳 |

r. c. 2605 – c. 2596 BC (9 years) |

| ||

| 9th |

|

En-nun-tarah-ana 𒂗𒉣𒁰𒀭𒈾 |

r. c. 2596 – c. 2588 BC (8 years) |

| ||

| 10th | Mesh-he 𒈩𒃶 |

"the smith" | r. c. 2588 – c. 2552 BC (36 years) |

| ||

| 11th | Melem-ana 𒈨𒉈𒀭𒈾 |

r. c. 2552 – c. 2546 BC (6 years) |

| |||

| 12th | Lugal-kitun 𒈗𒆠𒂅 |

r. c. 2546 – c. 2510 BC (36 years) |

| |||

— SKL | ||||||

| Early Dynastic IIIa period (c. 2550 – c. 2500 BC) | ||||||

| Lumma[66] 𒈝𒈠 |

Uncertain; these two rulers may have fl. c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC sometime during the Early Dynastic (ED) IIIa period | |||||

| Ursangpae |

| |||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BC) | ||||||

| Lugalnamniršumma 𒈗𒉆𒉪𒋧 |

Uncertain; these two rulers may have fl. c. 2500 – c. 2400 BC sometime during the ED IIIb period |

| ||||

|

Lugalsilâsi I 𒈗𒋻𒋛 |

|||||

|

Meskalamdug[citation needed] 𒈩𒌦𒄭 |

r. c. 2600, c. 2500 BC | ||||

|

Mesannepada[citation needed] 𒈩𒀭𒉌𒅆𒊒𒁕 |

r. c. 2500 BC (80 years)[68] |

||||

| Urzage 𒌨𒍠𒌓𒁺 |

r. c. 2400 BC | |||||

| Second dynasty of Uruk / Uruk II dynasty (c. 2500 – c. 2340 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 2nd |

|

Lugal-kinishe-dudu 𒈗𒆠𒉌𒂠𒌌𒌌 |

r. c. 2430, c. 2400 BC (120 years)[68] |

|||

|

Lugal-kisal-si 𒈗𒆦𒋛 |

Son of Lugal-kinishe-dudu | Uncertain; these three rulers may have fl. c. 2400 – c. 2350 BC sometime during the EDIIIb period.[68] | |||

| Urni 𒌨𒉌𒉌𒋾 |

||||||

| Lugalsilâsi II 𒈗𒋻𒋛 |

||||||

| 3rd | Argandea 𒅈𒂵𒀭𒀀 |

r. c. 2350 BC (7 years) |

| |||

| Proto-Imperial period (c. 2350 – c. 2254 BC) | ||||||

| 1st |

|

Enshakushanna 𒂗𒊮𒊨𒀭𒈾 |

Son of Elulu (?) | r. c. 2430, c. 2350 BC (2 to 60 years) |

| |

— SKL | ||||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Third dynasty of Uruk / Uruk III dynasty (c. 2340 – c. 2254 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 1st |

|

Lugalzagesi 𒈗𒍠𒄀𒋛 |

Son of Ukush | r. c. 2340 – c. 2316 BC (25 to 34 years) |

| |

— SKL | ||||||

| Girimesi 𒀀𒄩𒋻𒁺𒋛 |

Uncertain; this ruler may have fl. c. 2350 – c. 2254 BC sometime during the Proto-Imperial period.[68] |

| ||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Akkadian period (c. 2254 – c. 2154 BC) | ||||||

| Fourth dynasty of Uruk / Uruk IV dynasty (c. 2254 – c. 2124 BC) | ||||||

| Amar-girid 𒀫𒀭𒄌𒆠 |

r. c. 2254 BC |

| ||||

| Gutian period (c. 2154 – c. 2119 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 1st |

|

Ur-nigin 𒌨𒌋𒌓𒆤 |

r. c. 2154 – c. 2147 BC (7 years) |

| ||

| 2nd |

|

Ur-gigir 𒌨𒄑𒇀 |

Son of Ur-nigin | r. c. 2147 – c. 2141 BC (6 years) |

| |

| 3rd |

|

Kuda 𒋻𒁕 |

r. c. 2141 – c. 2135 BC (6 years) |

| ||

| 4th | Puzur-ili 𒅤𒊭𒉌𒉌 |

r. c. 2135 – c. 2130 BC (5 years) |

| |||

| 5th | Ur-Utu 𒌨𒀭𒌓 |

Son of Ur-gigir | r. c. 2130 – c. 2124 BC (6 years) |

| ||

— SKL | ||||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Ur III period (c. 2119 – c. 2004 BC) | ||||||

| Fifth dynasty of Uruk / Uruk V dynasty (c. 2124 – c. 1872 BC) | ||||||

— SKL | ||||||

| 1st |

|

Utu-hengal 𒀭𒌓𒃶𒅅 |

r. c. 2124 – c. 2113 BC (7 to 26 years) |

| ||

— SKL | ||||||

| # | Depiction | Ruler | Succession | Epithet | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Isin-Larsa period (c. 2025 – c. 1763 BC) | ||||||

| Sixth dynasty of Uruk / Uruk VI dynasty (c. 1872 – c. 1802 BC) | ||||||

|

Sîn-kāšid 𒀭𒂗𒍪𒂵𒅆𒀉 |

r. c. 1865 – c. 1833 BC |

| |||

| Sin-eribam | Son of Sîn-kāšid[citation needed] | r. c. 1833 – c. 1827 BC |

| |||

|

Sîn-gāmil | Son of Sin-eribam | r. c. 1827 – c. 1824 BC |

| ||

| An-am 𒀭𒀀𒀭 |

r. c. 1824 – c. 1816 BC |

| ||||

| Irdanene | Son of Anam | r. c. 1816 – c. 1810 BC |

| |||

| Rîm-Anum | r. c. 1810 – c. 1802 BC |

| ||||

| Nabi-ilishu | r. c. 1802 BC |

| ||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Harmansah, Ömür (2007-12-03). "The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Ceremonial centers, urbanization and state formation in Southern Mesopotamia". Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ^ a b Nissen, Hans J (2003). "Uruk and the formation of the city". In Aruz, J (ed.). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 11–20. ISBN 978-0-300-09883-9.

- ^ Algaze, Guillermo (2013). "The end of prehistory and the Uruk period". In Crawford, Harriet (ed.). The Sumerian World. London: Routledge. pp. 68–95. ISBN 978-1-138-23863-3.

- ^ a b William K. Loftus, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana, Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana: With an Account of Excavations at Warka, the "Erech" of Nimrod, and Shush, "Shushan the Palace" of Esther, in 1849–52, Robert Carter & Brothers, 1857

- ^ Warwick Ball, "Rome in the East: the transformation of an empire", Routledge, 2016

- ^ "Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary, ePSD2". University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ a b c d Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13024-1.

- ^ Fassbinder, J.W.E., and H. Becker, "Magnetometry at Uruk (Iraq): The city of King Gilgamesh", Archaeologia Polona, vol. 41, pp. 122–124, 2003

- ^ Kesecker, Nshan (January 2018). "Lugalzagesi: The First Emperor of Mesopotamia?". ARAMAZD Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 12: 76–96. doi:10.32028/ajnes.v12i1.893. S2CID 257461809.

- ^ Marchesi, Gianni, "The Sumerian King List and the early history of Mesopotamia", Vicino Oriente Quaderno, pp. 231–248, 2010

- ^ a b Eva von Dassow, "Narām-Sîn of Uruk: A New King in an Old Shoebox", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 61, pp. 63–91, 2009

- ^ a b Frayne, Douglas, "Uruk", Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 439–483, 1990

- ^ Rients de Boer, "Beginnings of Old Babylonian Babylon: Sumu-Abum and Sumu-La-El", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 70, pp. 53–86, 2018

- ^ Seri, Andrea, "The archive of the house of prisoners and political history", The House of Prisoners: Slavery and State in Uruk during the Revolt against Samsu-iluna, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 20–54, 2013

- ^ Witold Tyborowski, "New Tablets from Kisurra and the Chronology of Central Babylonia in the Early Old Babylonian Period", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 102, iss. 2, pp. 245–269, 2012, ISSN 0084-5299

- ^ a b H. D. Baker, "The Urban Landscape in First Millennium BC Babylonia", University of Vienna, 2002

- ^ R. van der Spek "The Latest on Seleucid Empire Building in the East". Journal of the American Oriental Society 138.2 (2018): 385–394.

- ^ a b R. van der Spek. "Feeding Hellenistic Seleucia on the Tigris". In R. Alston & O. van Nijf, eds. Feeding the Ancient Greek City 36. Leuven ; Dudley, Massachusetts: Peeters Publishers, 2008.

- ^ C. A. Petrie, "Seleucid Uruk: An Analysis of Ceramic Distribution", Iraq, vol. 64, 2002, pp. 85–123, 2002

- ^ Rudolf Macuch, "Gefäßinschriften", in Eva Strommenger (ed.), Gefässe aus Uruk von der Neubabylonischen Zeit bis zu den Sasaniden (= Ausgrabungen der deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka 7), pp. 55–57, pl. 57.1–3, Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1967

- ^ "Couteau du Gebel el-Arak at the Louvre Museum". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Cooper, Jerrol S. (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. pp. 10–14. ISBN 978-0-931464-96-6.

- ^ Crawford, Harriet E.W., "Sumer and the Sumerians", Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-521-53338-4

- ^ Oppenheim, A. Leo; Erica Reiner (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 445. ISBN 0-226-63187-7.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ a b Charvát, Petr; Zainab Bahrani; Marc Van de Mieroop (2002). Mesopotamia Before History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25104-4.

- ^ Nissen, H. J., "Uruk: Key Site of the Period and Key Site of the Problem", in Artefacts of Complexity: Tracking the Uruk in the Near East, edited by J. N. Postgate, Warminster: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, pp. 1–16, 2002

- ^ a b Nissen, H. J., "The City Wall of Uruk", in Ucko, P. J., R. Tringham and G. W. Dimbleby (eds.), Man, Settlement and Urbanism. London: Duckworth, pp. 793–98, 1972

- ^ North, Robert, "Status of the Warka Excavation", Orientalia, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 185–256, 1957

- ^ Fraser, James Baillie, Travels in Koordistan, Mesopotamia, Etc: Including an Account of Parts of Those Countries Hitherto Unvisited by Europeans, R. Bentley, 1840

- ^ Reade, Julian, "Early monuments in Gulf stone at the British Museum, with observations on some Gudea statues and the location of Agade", vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 258-295, 2002

- ^ Walter Andrae, Die deutschen Ausgrabungen in Warka (Uruk), Berlin, 1935

- ^ Banks, Edgar James. "Warka, the Ruins of Erech (Gen. 10: 10) | The Biblical World 25.4, pp. 302–305, 1905". doi:10.1086/473565.

- ^ Julius Jordan, "Uruk-Warka nach dem ausgrabungen durch die Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft", Hinrichs, 1928 (German)

- ^ [1] Ernst Heinrich, "Kleinfunde aus den archaischen Tempelschichten in Uruk", Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1936 (German)

- ^ Faraj Basmachi (1949). The Lion-Hunt Stela from Warka | Sumer. Vol. 5, iss. 1. pp. 87–90.

- ^ H. J. Lenzen, "The Ningiszida Temple Built by Marduk-Apla-Iddina II at Uruk (Warka)", Iraq, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 146–150, 1957

- ^ a b H. J. Lenzen (1960). The E-anna district after excavations in the winter of 1958–59 | Sumer. Vol. 16. pp. 3–11.

- ^ H. J. Lenzen, "New discoveries at Warka in southern Iraq", Archaeology, vol. 17, pp. 122–131, 1964

- ^ J. Schmidt, "Uruk-Warka, Susammenfassender Bericht uber die 27. Kampagne 1969", Baghdader, vol. 5, pp. 51–96, 1970

- ^ Rainer Michael Boehmer, "Uruk 1980–1990: a progress report", Antiquity, vol. 65, pp. 465–478, 1991

- ^ M. van Ess and J. Fassbinder, "Magnetic prospection of Uruk (Warka) Iraq", in: La Prospection Géophysique, Dossiers d'Archeologie Nr. 308, pp. 20–25, Nov. 2005

- ^ Van Ess, Margarete, and J. Fassbinder, "Uruk-Warka. Archaeological Research 2016–2018, Preliminary Report", Sumer Journal of Archaeology of Iraq 65, pp. 47–85, 2019

- ^ Margarete van Ess, "Uruk, Irak. Wissenschaftliche Forschungen 2019", e-Forschungsberichte des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, vol. 2, pp. 117–121, 2019

- ^ van Ess, Margarete, et al., "Uruk, Irak. Wissenschaftliche Forschungen und Konservierungsarbeiten. Die Arbeiten der Jahre 2020 bis 2022", e-Forschungsberichte, pp. 1–31, 2022

- ^ Haibt, Max (2024). "End-to-end digital twin creation of the archaeological landscape in Uruk-Warka (Iraq)". International Journal of Digital Earth. 17 (1) 2324964. Bibcode:2024IJDE...1724964H. doi:10.1080/17538947.2024.2324964.

- ^ Fassbinder, Jörg W. E. "Beneath the Euphrates Sediments: Magnetic Traces of the Mesopotamian Megacity Uruk-Warka | Ancient Near East Today 8, 2020" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hans J. Nissen, "The Archaic Texts from Uruk", World Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 317–334, 1986

- ^ M. W. Green, "Archaic Uruk Cuneiform", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 464–466, 1986

- ^ Jan J. A. Djik, "Texte aus dem Rēš-Heiligtum in Uruk-Warka", (= Baghdader Mitteilungen. Beiheft 2), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1980 ISBN 3-7861-1282-7

- ^ Egbert von Weiher, "Spätbabylonischen Texte aus Uruk, Teil II". (= Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka 10), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1983 ISBN 3-7861-1336-X

- ^ Egbert von Weiher, "Spätbabylonischen Texte aus Uruk, Teil III", (= Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka 12), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1988 ISBN 3-7861-1508-7

- ^ Egbert von Weiher, "Uruk. Spätbabylonischen Texte aus aus dem Planquadrat U 18, Teil IV", (= Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka. Endberichte 12), Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1993 ISBN 3-8053-1504-X

- ^ Egbert von Weiher, Uruk. Spätbabylonischen Texte aus aus dem Planquadrat U 18, Teil V (= Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka. Endberichte 13), Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1998 ISBN 3-8053-1850-2

- ^ Erlend Gehlken, "Uruk. Spätbabylonischen Wirtschaftstext aus dem Eanna-Archiv, Teil 1", (= Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka. Endberichte 5), Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1990 ISBN 3-8053-1217-2

- ^ Erlend Gehlken, "Uruk. Spätbabylonischen Wirtschaftstext aus dem Eanna-Archiv, Teil 2", (= Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka. Endberichte 11), Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1996 ISBN 3-8053-1545-7

- ^ Corò, Paola, "The Missing Link – Connections between Administrative and Legal Documents in Hellenistic Uruk", Archiv für Orientforschung, vol. 53, pp. 86–92, 2015

- ^ Hunger, Hermann and de Jong, Teije, "Almanac W22340a From Uruk: The Latest Datable Cuneiform Tablet", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 104, no. 2, pp. 182–194, 2014

- ^ Mattessich, Richard, "Recent Insights into Mesopotamian Accounting of the 3rd Millennium B.C — Successor to Token Accounting", The Accounting Historians Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 1–27, 1998

- ^ Nissen, HansJörg; Damerow, Peter; Englund, Robert K., Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993

- ^ Burmeister, Stefan (2017). The Interplay of People and Technologies Archaeological Case Studies on Innovations. Bernbeck, Reinhard (1st ed.). Berlin. ISBN 978-3-9816751-8-4. OCLC 987573072.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nissen, Hans J. (2015). "Urbanization and the techniques of communication: the Mesopotamian city of Uruk during the fourth millennium BCE". In Yoffee, Norman (ed.). Early Cities in Comparative Perspective, 4000 BCE–1200 CE. The Cambridge World History. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-521-19008-4.

- ^ "Tablet MSVO 3,12 /BM 140855: description on CDLI".

- ^ Rohl, David (1998). Legend: Genesis of Civilisation. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-7126-7747-9.

- ^ Mittermayer, C. (2009). Enmerkara und der Herr von Arata: Ein ungleicher Wettstreit (in German). Academic Press. ISBN 978-3-525-54359-7.

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr, "A Campaign of Southern City-States against Kiš as Documented in the ED IIIa Sources from Šuruppak (Fara)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 76.1, pp. 3-26, 2024

- ^ Jestin, Raymond R. 1937. Tablettes Sumériennes de S̈uruppak Conservées Au Musée de Stamboul. Mémoires de L’institut Français d’Archéologie de Stamboul 3. Paris : E. de Boccard.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Marchesi, Gianni (January 2015). Sallaberger, W.; Schrakamp, I. (eds.). "Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia". History & Philology (ARCANE 3; Turnhout): 139–156.

- ^ Kesecker, Nshan (January 2018). "Lugalzagesi: The First Emperor of Mesopotamia?". ARAMAZD Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 12: 76–96. doi:10.32028/ajnes.v12i1.893. S2CID 257461809.

- ^ , Jerold S. Cooper, Sumerian and Akkadian Royal Inscriptions: Presargonic Inscriptions, Eisenbrauns, 1986, ISBN 0-940490-82-X

- ^ C.J Gadd (1924). A Sumerian reading-book. Clarendon Press.

Further reading

[edit]- [2] R. McC. Adams and H. Nissen, "The Uruk Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban Societies", Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972 ISBN 0-226-00500-3

- [3] Banks, Edgar James, "A Vase Inscription from Warka", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 62–63, 1904

- [4] Brandes, Mark A., "Untersuchungen zur Komposition der Stiftmosaiken an der Pfeilerhalle der Schicht IVa in Uruk-Warka", Berlin : Gebr. Mann, 1968.

- Green, MW (1984). "The Uruk Lament". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 104 (2): 253–279. doi:10.2307/602171. JSTOR 602171.

- Liverani, Mario; Zainab Bahrani; Marc Van de Mieroop (2006). Uruk: The First City. London: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 1-84553-191-4.

- [5] Seton Lloyd, "Foundations in the Dust", Oxford University Press, 1947

- [6] Nies, James B., "A Pre-Sargonic Inscription on Limestone from Warka", Journal of the American Oriental Society 38, pp. 188–196, 1918

- [7] Nissen, Hans J., "Uruk and I", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2024 (1), 2024

- [8] Ann Louise Perkins, "The Comparative Archeology of Early Mesopotamia", Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 25, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1949

- Postgate, J.N. (1994). Early Mesopotamia, Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. New York, New York: Routledge Publishing. p. 367. ISBN 0-415-00843-3.

- Rositani, Annunziata, "The Status of War Prisoners at Uruk in the Old Babylonian Period", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, 2024

- Rositani, Annunziata, "King Rīm-Anum of Uruk: A Reconstruction of an Old Babylonian Rebel Kingdom", DOCUMENTA ASIANA 14, pp. 109–123, 2024

- Rothman, Mitchell S. (2001). Uruk, Mesopotamia & Its Neighbors. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. p. 556. ISBN 1-930618-03-4.

- Sandowicz, Małgorzata, Cornelia Wunsch, and Stefan Zawadzki, "On Shifting Social and Urban Landscapes in Uruk under Nabû-kudurrī-uṣur II: A View from One Neighborhood", Altorientalische Forschungen 50.2, pp. 206–236, 2023

- Stevens, Kathryn, "Secrets in the Library: Protected Knowledge and Professional Identity in Late Babylonian Uruk", Iraq, vol. 75, pp. 211–53, 2013

- Eva Strommenger, The Chronological Division of the Archaic Levels of Uruk-Eanna VI to III/II: Past and Present, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 479–487, Oct. 1980

- Szarzyńska, Krystyna, "Offerings for the Goddess Inana in Archaic Uruk", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie Orientale, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 7–28, 1993

- Krystyna Szarzyńska, Observations on the Temple Precinct EŠ3 in Archaic Uruk, Journal of Cuneiform Sudies, vol. 63, pp. 1–4, 2011

External links

[edit]- Archaeologists unearth ancient Sumerian riverboat in Iraq – Ars Technica – 4/8/2022

- News from Old Uruk – Margarete van Ess 2021 Oriental Institute lecture on recent work

- Earliest evidence for large scale organized warfare in the Mesopotamian world (Hamoukar vs. Uruk?)

- Uruk at CDLI wiki

- Lament for Unug (in Sumerian)

- Archaeological Expedition Mapping Ancient City Of Uruk in 2002

- Digital images of tablets from Uruk – CDLI

Toponymy

Etymology and Historical Names

The name Uruk derives from the Sumerian Unug, denoting an "abode," "site," or "location," reflecting its status as one of the earliest urban centers in southern Mesopotamia.[10] In cuneiform script, it appears as 𒀕 (unug), often compounded as Unugki to specify the city-state.[10] This Sumerian term evolved into the Akkadian Ūruk (𒌷𒀕), maintaining the core phonetic structure while adapting to Semitic phonology during the city's prominence in the third millennium BCE.[11] In Semitic languages, the name appears as Erech (Hebrew אֶרֶךְ), attested in the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 10:10) as a foundational city in the kingdom of Nimrod, likely transmitted via Aramaic intermediaries from the Babylonian Uruk.[12] Greek sources rendered it as Orchoi or Orchōē, preserving the approximate pronunciation in Hellenistic accounts of Babylonian geography.[13] The modern Arabic name is Warkāʾ (وركاء), used for the archaeological site since at least the early Islamic period, reflecting phonetic shifts from Aramaic ʾrk and possibly influencing the regional toponym al-ʿIrāq for lower Mesopotamia.[14] Archaeological records confirm continuous usage of variants like Warqa from the second millennium BCE onward.[14]Geography and Environment

Location and Physical Setting

The archaeological site of Uruk, modernly designated as Warka or Warqa, is situated in southern Iraq within Al-Muthanna Governorate, approximately 30 kilometers east of Samawah and 35 kilometers east of the contemporary Euphrates River channel.[15] [16] This positioning places it in the expansive alluvial plain of southern Mesopotamia, historically watered by the Euphrates but now distanced from its shifted course, which followed a dried-up ancient riverbed.[17] The site's coordinates are approximately 31.32°N latitude and 45.635°E longitude.[17] Physically, Uruk occupies a low-lying tell mound rising modestly above the surrounding flat terrain, formed by millennia of occupational debris across an area spanning roughly 5 kilometers in diameter.[18] The landscape features the characteristic silt-laden deposits of the Mesopotamian deltaic plain, shaped by fluvial processes of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, though environmental shifts have rendered the vicinity a semi-arid desert zone with sparse vegetation and reliance on distant water sources in antiquity via canals.[19] [20] The terrain's uniformity facilitated early urban expansion but exposed the settlement to flooding risks and sediment accumulation, influencing architectural adaptations like mud-brick platforms.[21] Uruk's setting within this dynamic fluvial environment underscores its role in pioneering irrigation-dependent agriculture, with the plain's fertile potential evident from paleoenvironmental proxies indicating wetter conditions during the fourth millennium BCE, gradually yielding to aridity.[21] The site's enclosure by ancient city walls, remnants of which delineate the urban core, highlights deliberate boundary-making amid an otherwise undifferentiated horizon.[20]Euphrates River Influence and Climate

Uruk was originally situated on an active channel of the Euphrates River in southern Mesopotamia, approximately 35 kilometers east of the river's modern course near the site of Warka in present-day Iraq.[16] The Euphrates provided critical freshwater for irrigation, enabling the cultivation of crops such as barley, wheat, and dates on the surrounding alluvial floodplains, which supported the city's rapid urbanization during the Uruk Period (ca. 4000–3100 BCE).[22] Periodic inundations deposited fertile silt, boosting soil productivity, though the river's unpredictability necessitated the construction of canals and levees to manage floods and distribute water systematically.[22] Shifts in the Euphrates' meandering path over millennia distanced Uruk from the main waterway; by the 1st millennium BCE, the city relied on secondary channels and artificial irrigation networks, contributing to its eventual decline as trade and water access diminished.[16] This riverine dependence fostered early innovations in hydraulic engineering, integral to sustaining Uruk's population, estimated at up to 50,000–80,000 inhabitants at its peak around 3000 BCE.[18] The regional climate during Uruk's formative phases was semi-arid with hot summers averaging 40°C (104°F) and mild winters, receiving scant annual rainfall of about 100–200 mm, primarily in the cooler months from November to April. Paleoclimatic reconstructions indicate slightly wetter conditions in southern Mesopotamia around 6000–4000 calibrated years before present, coinciding with the onset of urbanism, as evidenced by increased moisture availability that enhanced agricultural viability without fully alleviating irrigation needs.[23] Subsequent aridification trends from the mid-Holocene onward intensified reliance on river systems, underscoring the Euphrates' pivotal role in mitigating environmental constraints.[24]Chronological History

Origins and Uruk Period (ca. 4000–3100 BCE)

The origins of Uruk lie in the transition from the preceding Ubaid period (c. 5500–4000 BCE), with the site's earliest substantial occupation layers dating to approximately 4000 BCE, building on smaller Ubaid-era settlements characterized by mud-brick houses and basic irrigation farming.[21] Archaeological surveys in the Warka region indicate that initial growth stemmed from intensified agriculture exploiting alluvial soils near the Euphrates River, enabling surplus production that supported denser populations and craft specialization.[21] By the early phases of the Uruk period, the settlement had expanded beyond 70 hectares, marking a shift from dispersed villages to nucleated urbanism driven by administrative centralization around temple institutions.[25] The Uruk Period (ca. 4000–3100 BCE), divided into Early (Uruk XVIII–XVI), Middle (XV–XIV), and Late (XIII–IV) phases based on stratigraphic pottery sequences, witnessed Uruk's rapid urbanization, reaching up to 250 hectares in extent by its close and sustaining a population conservatively estimated at 25,000–50,000, far surpassing contemporaneous sites like Eridu or Erbil.[26][27] Monumental architecture emerged prominently in the Eanna precinct, where successive temple platforms—such as the Limestone Temple (Uruk V–VI)—featured terraced structures up to 10–15 meters high, adorned with multicolored cone mosaics and bitumen waterproofing, reflecting organized labor mobilization likely tied to religious and economic functions.[26] The Anu district saw parallel developments with white-washed temples on conical hills, underscoring a theocratic model where temples served as hubs for grain storage, redistribution, and ritual.[21] Key technological and social innovations defined the period, including the adoption of the fast potter's wheel for mass-producing bevel-rimmed bowls—standardized vessels numbering in the millions across sites, interpreted as rations in temple-administered labor systems.[4] Proto-cuneiform script appeared in Late Uruk (c. 3400–3100 BCE) on clay tablets from Eanna, initially pictographic for accounting commodities like barley and sheep, with over 5,000 exemplars recovered, evidencing bureaucratic complexity for managing agrarian surpluses.[26] These developments coincided with the "Uruk Expansion," where Uruk-style artifacts, including cylinder seals and pottery, appeared in northern Mesopotamia and Susiana (c. 3700–3100 BCE), indicating trade or emulation rather than direct conquest, as supported by colonial sites like Habuba Kabira with enclosed settlements mirroring Uruk's walled enclosures.[21] This phase laid foundational patterns for state formation, though source interpretations vary, with some emphasizing temple-led hierarchy over secular elites due to the scarcity of royal inscriptions.[26]Early Dynastic Period (ca. 2900–2350 BCE)

During the Early Dynastic period, Uruk solidified its role as a paramount Sumerian city-state, with archaeological strata revealing sustained urban growth and architectural elaboration in its sacred precincts following the innovations of the Uruk period. Temple complexes such as Eanna, dedicated to Inanna, underwent phased reconstructions, including the ED III level characterized by columnar halls and administrative buildings, indicative of centralized ritual and economic functions. The Anu district similarly featured terraced platforms supporting shrines, reflecting continuity in cultic practices amid evolving political structures. This era marked a gradual transfer of authority from priestly to royal institutions, as evidenced by increased palatial elements in the archaeological record.[2][21] Uruk attained its peak extent in Early Dynastic I, encompassing expansive hinterlands that supported agricultural intensification through irrigation networks, though precise population figures remain estimates derived from settlement surveys rather than direct counts. Cuneiform inscriptions and cylinder seals from this phase document administrative sophistication, including resource allocation and labor organization tied to temple estates. Inter-city rivalries emerged, with Uruk engaging in conflicts reflective of competition for arable land and water rights among Sumerian polities, though specific military campaigns are sparsely attested beyond legendary accounts.[21][2] In Early Dynastic III, historical rulers become identifiable through dedicatory inscriptions, notably Lugal-kinishe-dudu and his successor Lugal-kisal-si (ca. 2400–2350 BCE), who claimed kingship over Uruk, Ur, and Kish, suggesting temporary hegemony via conquest or alliance. Lugal-kisal-si's limestone foundation peg, inscribed to the goddess Namma, wife of An, was embedded in temple foundations, attesting to royal patronage of cultic building projects. These artifacts provide tangible evidence of dynastic succession and titulary expansion, contrasting with the semi-mythical figures of earlier phases like Gilgamesh, whose historicity is debated but potentially rooted in ED II leadership around 2700 BCE. By the period's close, Uruk's dominance waned as rival cities like Umma asserted regional power, setting the stage for Akkadian unification.[28][2]Akkadian Empire to Old Babylonian Period (ca. 2350–1595 BCE)

During the Akkadian Empire (ca. 2334–2154 BCE), Uruk was incorporated into the centralized Semitic-dominated realm following its conquest by Sargon of Akkad around 2334 BCE, marking the end of Sumerian city-state independence. Archaeological strata at the Eanna precinct reveal continuity in ceramic production, with Akkadian-period types such as conical bowls (O-10) and plain-rim jars (C-1) paralleling those from contemporary sites, indicating sustained urban occupation and adaptation to imperial administration rather than major disruption.[29] No extensive monumental rebuilding is attested, but Uruk's temples likely served as local cult centers under Akkadian oversight, with textual references to governors or ensis managing tribute and labor.[29] The empire's collapse circa 2154 BCE ushered in the Gutian interregnum (ca. 2147–2116 BCE), a period of decentralized rule by highland invaders from the Zagros Mountains, during which Uruk experienced devastation as described in Sumerian lament texts portraying the city as "smitten with weapons" and its kingship "carried off." The Sumerian King List attributes a brief Fourth Dynasty of Uruk to this era, listing Susuda (reigned ca. 200+ years in the list's exaggerated chronology), Dadase (ca. 90 years), and Mamagal, reflecting intermittent local control amid chaos, though archaeological evidence shows no clear destruction layers but rather a shift to simpler pottery forms signaling economic contraction.[30][29] Circa 2116 BCE, Utu-hengal seized power in Uruk and defeated the Gutian king Tirigan in battle, expelling the invaders and restoring Sumerian hegemony, as recorded in his inscriptions claiming liberation of cities like Uruk, Ur, and Lagash. His brief reign (ca. 2116–2110 BCE) ended violently, but it enabled Ur-Nammu to found the Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2112–2004 BCE), under which Uruk functioned as a key provincial hub with appointed governors overseeing agriculture, corvée labor, and temple estates, evidenced by numerous administrative cuneiform tablets documenting grain allocations and workforce mobilization. Pottery innovations, including small bowls with inturned rims (O-13) and thickened rounded-rim jars (C-29), underscore renewed trade and ceramic standardization during this Neo-Sumerian revival.[31] Following Ur III's fall to Elamite invasion circa 2004 BCE, Uruk navigated the Isin-Larsa rivalry (ca. 2004–1763 BCE) with fluctuating autonomy, producing carinated-shoulder jars (C-20) and triple-ridged-rim vessels (C-28) that reflect Isin-Larsa stylistic influences in archaeological assemblages. In the early Old Babylonian period, Amorite ruler Sin-kāšid (ca. 1865–1833 BCE) established a short-lived dynasty, wresting control from Larsa, building a palace in the city's western quarter, and dedicating foundation cones and bricks to deities like Inanna and Lugalbanda, as inscribed on clay artifacts attesting to temple restorations and urban fortification.[29][32][33] Under Hammurabi's Babylonian unification (ca. 1763 BCE onward), Uruk persisted as a religious center with ongoing cultic activity at Eanna, though environmental shifts, including the Euphrates River's gradual avulsion away from the city by the late third millennium BCE, contributed to silting and reduced fertility, fostering long-term decline evidenced by sparser later strata. Administrative texts and votive objects indicate continuity until the period's close circa 1595 BCE with the Hittite sack of Babylon, after which Uruk's prominence waned further.[34][29]Kassite, Neo-Assyrian, and Later Periods to Decline (ca. 1595 BCE–7th century CE)

![Part of the façade of the Inanna Temple built by Kassite king Kara-Indash at Uruk][float-right] Following the Hittite destruction of Babylon circa 1595 BCE, Uruk entered the Kassite period under the rule of the Kassite dynasty, which governed southern Mesopotamia until approximately 1155 BCE.[35] The city maintained its role as a religious and administrative center within the Kassite kingdom, with evidence of continued temple maintenance and economic activity documented in cuneiform texts.[36] A notable architectural achievement occurred during the reign of Kassite king Karaindash, around 1413 BCE, who commissioned a temple façade in the Eanna precinct dedicated to the goddess Inanna.[37] This structure featured molded and glazed bricks depicting alternating male and female deities, including mountain gods and water goddesses pouring life-giving streams, exemplifying Kassite artistic influences blended with Mesopotamian traditions.[38][39] After the fall of the Kassites amid Elamite invasions around 1155 BCE, Uruk experienced periods of instability before incorporation into the expanding Neo-Assyrian Empire by the 9th century BCE.[35] As a provincial city under Assyrian control, Uruk contributed to the empire's administration and cult practices, though specific monumental constructions from this era are less attested archaeologically compared to earlier phases. The city's fortunes revived somewhat in the Neo-Babylonian period (626–539 BCE), marked by scholarly production, including astronomical and lexical tablets that highlight Uruk's enduring intellectual tradition.[40] Conquered by Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE, Uruk persisted under Achaemenid Persian rule as a temple center, with local priesthoods managing estates and rituals.[34] In the subsequent Seleucid Hellenistic period (312–63 BCE), the Eanna precinct remained active, focusing on the worship of Inanna/Ishtar, as evidenced by excavations revealing continued ritual deposits and cuneiform records.[41] Under Parthian domination from 141 BCE, Uruk's urban fabric endured, though settlement patterns shifted, with evidence of Parthian-era occupations in surveys of southern Mesopotamia.[42] Into the Sasanian period (224–651 CE), Uruk saw fluctuating habitation, vulnerable to environmental stresses and regional power dynamics, leading to a gradual decline in population and monumental activity.[42] By the 7th century CE, following the Arab Muslim conquests, the city was largely abandoned, with its temples and infrastructure falling into ruin, marking the end of continuous occupation that had spanned over three millennia.[43]Governance and Administration

Political Structure and State Formation

The political structure of Uruk emerged during the Uruk Period (c. 4000–3100 BCE) as a theocratic system dominated by temple institutions, particularly the Eanna complex dedicated to Inanna and the Anu precinct. The high priest, titled en, held supreme authority, functioning as both religious intermediary and administrative overseer of temple estates, which controlled vast agricultural lands, labor allocation, and resource redistribution. This centralization enabled the mobilization of surplus for urban growth and monumental architecture, laying the groundwork for state formation through bureaucratic coordination rather than kinship-based tribalism. Archaeological evidence includes proto-cuneiform tablets documenting rations, inventories, and transactions, indicating specialized officials managing temple affairs.[44][45] State formation in Uruk is evidenced by the development of a four-tier settlement hierarchy and territorial expansion beyond a 25–30 km radius from the city core by around 3500 BCE, extending influence to regions like Susiana (250 km east) via colonies and outposts. This required delegated governance, with administrative artifacts such as seals, bullae, and standardized ceramics attesting to direct control and extraction of resources like timber and metals, fostering a proto-state apparatus. The territorial-expansion model posits that such outreach, driven by resource scarcity in the alluvial plain, necessitated formalized authority structures to maintain cohesion and extract tribute, distinguishing Uruk as one of the earliest primary states.[45] By the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2900–2350 BCE), Uruk's governance saw a shift toward secular kingship with the lugal (king) emerging as a military and executive leader, supplementing the en's ritual role, though temples retained economic dominance. Iconographic depictions, such as the "priest-king" statue from Uruk (c. 3300 BCE), portray a robed figure in authoritative pose, symbolizing the fusion of divine and temporal power. No contemporary named rulers survive from the Uruk Period, but later traditions attribute dynastic origins to legendary figures, reflecting retrospective idealization of priestly origins. This evolution underscores causal drivers like irrigation-dependent agriculture generating surpluses that incentivized hierarchical control to manage flood risks and labor for canals.[44]Known Rulers and Dynasties

![Limestone foundation peg of Lugal-kisal-si, from Uruk, Iraq. C. 2380 BCE. Pergamon Museum.jpg][float-right] Historical evidence for rulers of Uruk is sparse prior to the late Early Dynastic period, with most accounts deriving from the Sumerian King List, which blends mythological and historical elements and attributes implausibly long reigns to early kings such as Gilgamesh, traditionally dated around 2700 BCE but lacking contemporary corroboration.[30] The list posits five dynasties for Uruk, commencing after Kish with figures like Mesh-ki-ang-gasher and Enmerkar, but these remain unverified by inscriptions or artifacts specific to Uruk governance.[46] One of the earliest archaeologically attested rulers is Lugal-kisalsi, king of Uruk and Ur circa 2380 BCE during Early Dynastic III, son of Lugal-kinishe-dudu; his reign is evidenced by a limestone foundation peg dedicated to the goddess Nammu's temple in Uruk, indicating temple-building activities and territorial control extending to Ur.[47] Lugal-kisalsi held the title "king of Kish," suggesting hegemony over Sumerian cities before his defeat by contemporaries like Enshakushanna of Kish or later Lugalzagesi of Umma, who briefly ruled Uruk.[28] Following conquests by the Akkadian Empire under Sargon (ca. 2334–2279 BCE) and the Ur III dynasty (ca. 2112–2004 BCE), Uruk lacked independent kings, functioning under imperial governors or ensi; no distinct local dynasty is attested during these centralized periods. In the Isin-Larsa interregnum and early Old Babylonian era, Uruk experienced brief autonomy under an Amorite dynasty founded by Sin-kashid (ca. 1865–1833 BCE), who established independence from Larsa and built extensively, including a palace.[48] Sin-kashid's successors included Sin-eribam and Ilum-gamil, culminating in Sin-gamil (ca. 1827–1824 BCE), whose inscriptions record the construction of a royal palace and the Emeurur temple for Inanna in Uruk, as well as dedications to Nergal; his rule ended with subjugation by Larsa's Rim-Sin I.[49] This short-lived dynasty represents the last phase of Uruk's semi-independent kingship before prolonged incorporation into Babylonian, Kassite, and Assyrian administrations, with no further named local rulers documented amid the city's decline.[50] ![Tablet of Sin-Gamil of Uruk.jpg][center]Urban Development and Architecture

City Layout and Monumental Construction

Uruk's urban layout during the Late Uruk period (ca. 3500–3100 BCE) centered on two principal sacred precincts, the Anu district in the northwest and the Eanna district in the southeast, separated by residential and administrative zones within a mud-brick enclosure wall. The city encompassed roughly 250 hectares, with monumental architecture concentrated in the elevated temple complexes that dominated the flat alluvial plain. These precincts featured multi-phase constructions rebuilt over centuries, reflecting centralized labor organization and resource allocation for religious and administrative functions.[16][2] The Anu precinct included a terraced ziggurat platform originating around 4000 BCE, evolving through multiple layers to support the White Temple (ca. 3500–3000 BCE), dedicated to the sky god Anu. This temple measured 17.5 by 22 meters at its base, constructed from mud-brick with walls preserving heights exceeding 3 meters in excavations; its rectangular plan incorporated buttresses and niches typical of early Mesopotamian temple design. The ziggurat's stepped form, built by piling mud-brick platforms, elevated the structure above surrounding buildings, symbolizing a link between earthly and divine realms through empirical layering evident in stratigraphic evidence.[51][26] In the Eanna precinct, monumental buildings from phases VI–V (ca. 3500–3000 BCE) included tripartite temples and pillar halls adorned with innovative cone mosaics—thousands of clay cones, up to 10 cm long, dipped in bitumen, painted in red, black, and white, and embedded tip-first into mud-brick walls to create geometric patterns and friezes depicting animals or reeds. These structures, such as the Limestone Temple and Mosaic Temple, spanned areas up to several hundred square meters, with facades employing recessed niches and bent-axis approaches to inner sanctuaries, as revealed by German excavations at Warka. The use of standardized mud-brick (ca. 32x16x6 cm) across buildings indicates mass production and logistical planning for construction.[2][16] The city's enclosing wall, constructed of mud-brick pisé techniques, formed an irregular oval perimeter estimated at 9–10 km in length by the Early Dynastic period (ca. 2900–2350 BCE), though foundations date to the Uruk period; it stood up to 10 meters high in places, with gates and towers facilitating control over access and trade. This layout's causal role in urban centralization is supported by the density of administrative artifacts, like proto-cuneiform tablets, found near precincts, evidencing coordinated labor for maintenance and expansion. Later phases saw rebuilding in baked brick during the Neo-Sumerian period (ca. 2112–2004 BCE), but core monumental forms persisted from Uruk origins.[2][16]Eanna and Anu Temple Complexes

The Eanna precinct, located in the southern sector of Uruk, served as the primary temple complex dedicated to the goddess Inanna and encompassed successive monumental constructions from the Late Uruk Period onward. Archaeological excavations reveal at least 18 stratified levels, with significant development in phases VI through III (ca. 3500–2900 BCE), featuring terraced platforms, multi-chambered temples, and innovative building techniques such as the use of plano-convex bricks and colored clay cone mosaics for facade decoration.[52] In Eanna IV (ca. 3300–3100 BCE), subdivided into IVb and IVa, the precinct included specialized structures like the Limestone Temple and the Temple with the Mosaic Façade, alongside administrative buildings where proto-cuneiform tablets documenting economic activities were found.[53] These phases reflect centralized planning and ritual functions, with evidence of burnt layers indicating periodic reconstructions possibly linked to deliberate ritual destruction.[54] The Anu precinct, situated in the northern part of the city, centered on a massive ziggurat dedicated to the sky god Anu, initiated around 4000 BCE and expanded through approximately 14 construction phases labeled L to A.[55] The most prominent structure, the White Temple (Uruk V–IV, ca. 3500–3000 BCE), crowned the ziggurat's platform, which rose about 13 meters high, and was characterized by white gypsum plaster coating its walls, a rectangular hall with buttresses, and niches for cultic activities.[51] Excavations yielded 19 gypsum plaque tablets inscribed with cylinder seal impressions, attesting to early bureaucratic accounting within the temple.[51] The complex's evolution from a simple mound to a multi-tiered platform underscores its role in elevating sacred spaces above the urban landscape, influencing later Mesopotamian ziggurat designs.[56] Both complexes integrated religious, economic, and administrative roles, with Eanna emphasizing Inanna's cult through diverse temple layouts and Anu focusing on celestial worship via elevated architecture; their proximity within Uruk's 5.5 square kilometer walled area facilitated interconnected ritual and governance practices during the city's formative urbanization.[57] Later rebuilds, such as the Neo-Sumerian Eanna (ca. 2100–2000 BCE), incorporated larger ziggurats and courtyard temples, maintaining continuity amid dynastic changes. Archaeological evidence from German excavations since the 1920s confirms these structures' foundational role in Sumerian temple ideology, though preservation challenges and limited excavation (less than 5% of the site) constrain full interpretations.[57]Economy and Technology

Agriculture, Irrigation, and Resource Management

The economy of Uruk during the Uruk period (ca. 4000–3100 BCE) was fundamentally agrarian, centered on the cultivation of cereals such as barley and emmer wheat, supplemented by lentils and date palms in the southern alluvial plain.[58] Archaeological evidence from contemporary sites, including carbonized remains and stable isotope analysis, indicates barley dominated due to its resilience in semi-arid conditions, while wheat required wetter microenvironments, likely near canals or depressions.[58] Clay sickles, found at over 100 rural sites around Uruk from the Ubaid to Late Uruk phases, attest to systematic harvesting practices, with normal-sized tools for large-scale operations and smaller variants possibly for specialized tasks.[21] Irrigation was essential to counter the region's unpredictable rainfall and reliance on Tigris and Euphrates flooding, with early Uruk communities leveraging natural tidal influences from the Persian Gulf to facilitate water diversion—tides pushed saline water upstream, enabling easier freshwater uptake for fields without extensive engineering.[59][60] As tidal efficacy declined due to delta progradation by the mid-4th millennium BCE, inhabitants constructed artificial canals and levees, evidenced by meandering watercourses with offtakes at sites like Qalca Sussa and U-shaped drainage troughs on five rural settlements.[21] These systems addressed silt buildup from upstream meltwater, flood risks, and post-flood droughts by incorporating bucket hoists over barriers and canal networks to regulate flow, though salinization emerged as a long-term challenge from over-irrigation.[61] Resource management was centralized under temple authorities, which coordinated labor for canal maintenance and land allocation, as inferred from clustered rural settlements (e.g., 108 Late Uruk sites in coordinated tracts) and proto-administrative artifacts like stone vessels for storage.[21] This temple-led economy generated surpluses—estimated to support densities of 100 persons per hectare via 1.5 hectares of irrigated land per person—fueling urban growth, with hoes on 15 sites indicating soil preparation for intensive farming.[21] Swamps and seasonal depressions provided supplementary resources like reeds and fish, diversifying beyond crops and mitigating drought risks through mixed exploitation.[21] By the Jemdet Nasr phase (ca. 3100–2900 BCE), artificial canals extended up to 15 km, linking new settlements and enhancing productivity, though archaeological traces remain indirect for the earliest phases, relying on watercourse beds and settlement patterns.[21]Trade Networks and Innovations (Wheel, Writing Precursors)