Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ferrous metallurgy

View on Wikipedia

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt,[1] were made from meteoritic iron-nickel.[2] It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ores began, but by the end of the 2nd millennium BC iron was being produced from iron ores in the region from Greece to India,[3][4][5][6][7][8][page needed] The use of wrought iron (worked iron) was known by the 1st millennium BC, and its spread defined the Iron Age. During the medieval period, smiths in Europe found a way of producing wrought iron from cast iron, in this context known as pig iron, using finery forges. All these processes required charcoal as fuel.

By the 4th century BC southern India had started exporting wootz steel, with a carbon content between pig iron and wrought iron, to ancient China, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.[citation needed] Archaeological evidence of cast iron appears in 5th-century BC China.[9] New methods of producing it by carburizing bars of iron in the cementation process were devised in the 17th century. During the Industrial Revolution, new methods of producing bar iron emerged, by substituting charcoal in favor of coke, and these were later applied to produce steel, ushering in a new era of greatly increased use of iron and steel that some contemporaries described as a new "Iron Age".[10]

In the late 1850s Henry Bessemer invented a new steelmaking process which involved blowing air through molten pig-iron to burn off carbon, and so producing mild steel. This and other 19th-century and later steel-making processes have displaced wrought iron. Today, wrought iron is no longer produced on a commercial scale, having been displaced by the functionally equivalent mild or low-carbon steel.[11]: 145

Meteoric iron

[edit]

Iron was extracted from iron–nickel alloys, which comprise about 6% of all meteorites that fall on the Earth. That source can often be identified with certainty because of the unique crystalline features (Widmanstätten patterns) of that material, which are preserved when the metal is worked cold or at low temperature. Those artifacts include, for example, spear tips and ornaments from ancient Egypt and Sumer around 4000 BC.[12]

These early uses appear to have been largely ceremonial or decorative. Meteoric iron is very rare, and the metal was probably very expensive, perhaps more expensive than gold. The early Hittites are known to have bartered iron (meteoric or smelted) for silver, at a rate of 40 times the iron's weight, with Assyria in the first centuries of the second millennium BC.[13]

Meteoric iron was also fashioned into tools in the Arctic when the Thule people of Greenland began making harpoons, knives, ulus and other edged tools from pieces of the Cape York meteorite. Typically pea-size bits of metal were cold-hammered into disks and fitted to a bone handle.[2] These artifacts were also used as trade goods with other Arctic peoples: tools made from the Cape York meteorite have been found in archaeological sites more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) distant. When the American polar explorer Robert Peary shipped the largest piece of the meteorite to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City in 1897, it still weighed over 33 tons. Another example of a late use of meteoric iron is an adze from around 1000 AD found in Sweden.[2]

Native iron

[edit]Native iron in the metallic state occurs rarely as small inclusions in certain basalt rocks. Besides meteoritic iron, Thule people of Greenland have used native iron from the Disko region.[2]

Iron smelting and the Iron Age

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Iron Age |

|---|

| ↑ Bronze Age |

| ↓ Ancient history |

Iron smelting—the extraction of usable metal from oxidized iron ores—is more difficult than tin and copper smelting. While these metals and their alloys can be cold-worked or melted in relatively simple furnaces (such as the kilns used for pottery) and cast into molds, smelted iron requires hot-working and can be melted only in specially designed furnaces. Iron is a common impurity in copper ores and iron ore was sometimes used as a flux, thus it is not surprising that humans mastered the technology of smelted iron only after several millennia of bronze metallurgy.[12]

The place and time for the discovery of iron smelting is not known, partly because of the difficulty of distinguishing metal extracted from nickel-containing ores from hot-worked meteoritic iron.[2] The archaeological evidence seems to point to the Middle East area, during the Bronze Age in the 3rd millennium BC. However, wrought iron artifacts remained a rarity until the 12th century BC.

The Iron Age is conventionally defined by the widespread replacement of bronze weapons and tools with those of iron and steel.[14] That transition happened at different times in different places, as the technology spread. Mesopotamia was fully into the Iron Age by 900 BC. Although Egypt produced iron artifacts, bronze remained dominant until its conquest by Assyria in 663 BC. The Iron Age began in India about 1200 BC, in Central Europe about 800 BC, and in China about 300 BC.[15][16] Around 500 BC, the Nubians, who had learned from the Assyrians the use of iron and were expelled from Egypt, became major manufacturers and exporters of iron.[17] The development of bloomery versus cast iron across regions may be due to influence by the applications demanded of iron within the respective socio-political environments[18]

Ancient Near East

[edit]

About 1500 BC, increasing numbers of non-meteoritic, smelted iron objects appeared in Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Egypt.[2] Nineteen meteoric iron objects were found in the tomb of Egyptian ruler Tutankhamun, who died in 1323 BC, including an iron dagger with a golden hilt, an Eye of Horus, the mummy's head-stand and sixteen models of an artisan's tools.[19] An Ancient Egyptian sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah as well as a battle axe with an iron blade and gold-decorated bronze shaft were both found in the excavation of Ugarit.[20]

Although iron objects dating from the Bronze Age have been found across the Eastern Mediterranean, bronzework appears to have greatly predominated during this period.[21] As the technology spread, iron came to replace bronze as the dominant metal used for tools and weapons across the Eastern Mediterranean (the Levant, Cyprus, Greece, Crete, Anatolia and Egypt).[14]

Iron was originally smelted in bloomeries, furnaces where bellows were used to force air through a pile of iron ore and burning charcoal. The carbon monoxide produced by the charcoal reduced the iron oxide from the ore to metallic iron. The bloomery, however, was not hot enough to melt the iron, so the metal collected in the bottom of the furnace as a spongy mass, or bloom. Workers then repeatedly beat and folded it to force out the molten slag. This laborious, time-consuming process produced wrought iron, a malleable but fairly soft alloy.[22]

Concurrent with the transition from bronze to iron was the discovery of carburization, the process of adding carbon to wrought iron. While the iron bloom contained some carbon, the subsequent hot-working oxidized most of it. Smiths in the Middle East discovered that wrought iron could be turned into a much harder product by heating the finished piece in a bed of charcoal, and then quenching it in water or oil. This procedure turned the outer layers of the piece into steel, an alloy of iron and iron carbides, with an inner core of less brittle iron.

Theories on the origin of iron smelting

[edit]The development of iron smelting was traditionally attributed to the Hittites of Anatolia of the Late Bronze Age.[23] It was believed that they maintained a monopoly on iron working, and that their empire had been based on that advantage. According to that theory, the ancient Sea Peoples, who invaded the Eastern Mediterranean and destroyed the Hittite empire at the end of the Late Bronze Age, were responsible for spreading the knowledge through that region. This theory is no longer held in the mainstream of scholarship,[23] since there is no archaeological evidence of the alleged Hittite monopoly. While there are some iron objects from Bronze Age Anatolia, the number is comparable to iron objects found in Egypt and other places of the same time period, and only a small number of those objects were weapons.[21]

A more recent theory claims that the development of iron technology was driven by the disruption of the copper and tin trade routes, due to the collapse of the empires at the end of the Late Bronze Age.[23] These metals, especially tin, were not widely available and metal workers had to transport them over long distances, whereas iron ores were widely available. However, no known archaeological evidence suggests a shortage of bronze or tin in the Early Iron Age.[24] Bronze objects remained abundant, and these objects have the same percentage of tin as those from the Late Bronze Age.

Indian subcontinent

[edit]

The history of ferrous metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent began in the 2nd millennium BC. Archaeological sites in the Gangetic plains have yielded iron implements dated between 1800 and 1200 BC.[25] By the early 13th century BC, iron smelting was practiced on a large scale in India.[25] In Southern India (present day Mysore) iron was in use 12th to 11th centuries BC.[4] The technology of iron metallurgy advanced in the politically stable Maurya period[26] and during a period of peaceful settlements in the 1st millennium BC.[4]

Iron artifacts such as spikes, knives, daggers, arrow-heads, bowls, spoons, saucepans, axes, chisels, tongs, door fittings, etc., dated from 600 to 200 BC, have been discovered at several archaeological sites of India.[15] The Greek historian Herodotus wrote the first western account of the use of iron in India.[15] The Indian mythological texts, the Upanishads, have mentions of weaving, pottery and metallurgy, as well.[27] The Romans had high regard for the excellence of steel from India in the time of the Gupta Empire.[28]

Perhaps as early as 500 BC, although certainly by 200 AD, high-quality steel was produced in southern India by the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon.[29] Iron chain was used in Indian suspension bridges as early as the 4th century.[30]

Wootz steel was produced in India and Sri Lanka from around 300 BC.[29] Wootz steel is famous from Classical Antiquity for its durability and ability to hold an edge. When asked by King Porus to select a gift, Alexander is said to have chosen, over gold or silver, thirty pounds of steel.[28] Wootz steel was originally a complex alloy with iron as its main component together with various trace elements. Recent studies have suggested that its qualities may have been due to the formation of carbon nanotubes in the metal.[31] According to Will Durant, the technology passed to the Persians and from them to Arabs who spread it through the Middle East.[28] In the 16th century, the Dutch carried the technology from South India to Europe, where it was mass-produced.[32]

Steel was produced in Sri Lanka from 300 BC[29] by furnaces blown by the monsoon winds. The furnaces were dug into the crests of hills, and the wind was diverted into the air vents by long trenches. This arrangement created a zone of high pressure at the entrance, and a zone of low pressure at the top of the furnace. The flow is believed to have allowed higher temperatures than bellows-driven furnaces could produce, resulting in better-quality iron.[33][34][35] Steel made in Sri Lanka was traded extensively within the region and in the Islamic world.

One of the world's foremost metallurgical curiosities is an iron pillar located in the Qutb complex in Delhi. The pillar is made of wrought iron (98% Fe), is almost seven meters high and weighs more than six tonnes.[36] The pillar was erected by Chandragupta II Vikramaditya and has withstood 1,600 years of exposure to heavy rains with relatively little corrosion.

China

[edit]

Numerous scholars have suggested that the Afanasievo culture may be responsible for the introduction of metallurgy to China.[37][38] In particular, contacts between the Afanasievo culture and the Majiayao culture and the Qijia culture are considered for the transmission of bronze technology.[39]

In 2008, two iron fragments were excavated at the Mogou site, in Gansu. They have been dated to the 14th century BC, belonging to the period of Siwa culture. One of the fragments was made of bloomery iron rather than meteoritic iron.[40][41]

The earliest iron artifacts made from bloomeries in China date to end of the 9th century BC.[42] Cast iron was used in ancient China for warfare, agriculture and architecture.[9] Around 500 BC, metalworkers in the southern state of Wu achieved a temperature of 1130 °C. At this temperature, iron combines with 4.3% carbon and melts. The liquid iron can be cast into molds, a method far less laborious than individually forging each piece of iron from a bloom.

Cast iron is rather brittle and unsuitable for striking implements. It can be decarburized to steel or wrought iron by heating it in air for several days. In China, these iron working methods spread northward, and by 300 BC, iron was the material of choice throughout China for most tools and weapons.[9] A mass grave in Hebei province, dated to the early 3rd century BC, contains several soldiers buried with their weapons and other equipment. The artifacts recovered from this grave are variously made of wrought iron, cast iron, malleabilized cast iron, and quench-hardened steel, with only a few, probably ornamental, bronze weapons.

During the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), the government established ironworking as a state monopoly, repealed during the latter half of the dynasty and returned to private entrepreneurship, and built a series of large blast furnaces in Henan province, each capable of producing several tons of iron per day. By this time, Chinese metallurgists had discovered how to fine molten pig iron, stirring it in the open air until it lost its carbon and could be hammered (wrought). In modern Mandarin-Chinese, this process is now called chao, literally stir frying. Pig iron is known as 'raw iron', while wrought iron is known as 'cooked iron'. By the 1st century BC, Chinese metallurgists had found that wrought iron and cast iron could be melted together to yield an alloy of intermediate carbon content, that is, steel.[43][44][45]

According to legend, the sword of Liu Bang, the first Han emperor, was made in this fashion. Some texts of the era mention "harmonizing the hard and the soft" in the context of ironworking; the phrase may refer to this process. The ancient city of Wan (Nanyang) from the Han period forward was a major center of the iron and steel industry.[46] Along with their original methods of forging steel, the Chinese had also adopted the production methods of creating Wootz steel, an idea imported from India to China by the 5th century AD.[47]

During the Han dynasty, the Chinese were also the first to apply hydraulic power (i.e. a waterwheel) in working the bellows of the blast furnace. This was recorded in the year 31 AD, as an innovation by the Chinese mechanical engineer and politician Du Shi, Prefect of Nanyang.[48] Although Du Shi was the first to apply water power to bellows in metallurgy, the first drawn and printed illustration of its operation with water power appeared in 1313 AD, in the Yuan dynasty era text called the Nong Shu.[49]

In the 11th century, there is evidence of the production of steel in Song China using two techniques: a "berganesque" method that produced inferior, heterogeneous steel and a precursor to the modern Bessemer process that utilized partial decarbonization via repeated forging under a cold blast.[50] By the 11th century, there was a large amount of deforestation in China due to the iron industry's demands for charcoal.[51] By this time however, the Chinese had learned to use bituminous coke to replace charcoal, and with this switch in resources many acres of prime timberland in China were spared.[51]

Iron Age Europe

[edit]

The earliest iron objects found in Europe date from the 3rd millennium BC, and are assigned to the Yamnaya culture and Catacomb culture.[52][53] Eastern Europe, especially the Cis-Ural region, shows the highest concentration of early and middle Bronze Age iron objects in western Eurasia,[54] though most of these are thought to consist of meteoric Iron.[55] A knife blade from the Catacomb culture dated to c. 2300 BC is thought to have been made from smelted iron.[53][55] During most of the Middle and Late Bronze Age in Central Europe, iron was present, though scarce. It was used for personal ornaments and small knives, for repairs on bronzes, and for bimetallic items.[56] Early smelted iron finds from central Europe include an iron knife or sickle from Ganovce in Slovakia, possibly dating from the 18th-15th century BC,[57][58] an iron ring from Vorwohlde in Germany dating from circa the 15th century BC,[59] and an iron chisel from Heegermühle in Germany dating from circa 1000 BC.[60][61] Smelted iron objects are known from Eastern Europe dating from after 1200 BC.[55]

In the 11th century BC iron swords replaced bronze swords in Southern Europe, especially in Greece, and in the 10th century BC iron became the prevailing metal in use.[62] In the Carpathian Basin there is a significant increase in iron finds dating from the 10th century BC onwards, with some finds possibly dating as early as the 12th century BC.[63] Iron swords have been found in central Europe dating from the 10th century BC; however, the Iron Age began in earnest with the Hallstatt culture from 800 BC.[64] Steel was produced from circa 800 BC as part of the production of swords,[65] and swords made entirely of high-carbon steel are known from pre-Roman period.[66] Evidence for iron metallurgy in Britain dates from the 10th century BC,[67] with the beginning of the Iron Age dated to the 8th century BC.[68] The production of high-carbon steel is attested in Britain from circa 490 BC.[69] Iron metallurgy began to be practised in Scandinavia during the later Bronze Age from at least the 9th century BC,[70] with evidence for steel production from 800–700 BC.[71] Iron and steel artefacts, including high-carbon steel, were manufactured in northern Sweden, Finland and Norway (in the Cap of the North) from c. 200–50 BC.[71] Evidence for iron metallurgy in Italy and Sardinia dates from the Late Bronze Age (c. 1350-950 BC).[72][73] High-carbon steel tools were produced in Iberia (Portugal) from c. 900 BC.[74][75]

From 500 BC the La Tène culture saw a significant increase in iron production, with iron metallurgy also becoming common in southern Scandinavia. The spread of ironworking in Central and Western Europe is associated with Celtic expansion.[65] By the 1st century BC, Noric steel was famous for its quality and sought after by the Roman military.[76] The annual output of iron in the Roman Empire is estimated at 84,750 tonnes.[77]

The production of ultrahigh carbon steel is attested at the Germanic site of Heeten in the Netherlands from the 2nd to 4th/5th centuries AD, in the Late Roman Iron Age.[78]

Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]

Archaeometallurgical scientific knowledge and technological development originated in numerous centers of Africa; the centers of origin were located in West Africa, Central Africa, and East Africa; consequently, as these origin centers are located within inner Africa, these archaeometallurgical developments are thus native African technologies.[79] Iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BCE – 2458 BCE at Lejja, in Nigeria, 2136 BCE – 1921 BCE at Obui, in Central Africa Republic, 1895 BCE – 1370 BCE at Tchire Ouma 147, in Niger, and 1297 BCE – 1051 BCE at Dekpassanware, in Togo.[79]

Though there is some uncertainty, some archaeologists believe that iron metallurgy was developed independently in sub-Saharan Africa (possibly in West Africa).[80][81]

Inhabitants of Termit, in eastern Niger, smelted iron around 1500 BC.[82]

In the region of the Aïr Mountains in Niger there are also signs of independent copper smelting between 2500 and 1500 BC. The process was not in a developed state, indicating smelting was not foreign. It became mature about 1500 BC.[83]

Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have also been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[84][81] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[81] The site of Gbabiri (in the Central African Republic) has yielded evidence of iron metallurgy, from a reduction furnace and blacksmith workshop; with earliest dates of 896–773 BC and 907–796 BC respectively.[85] Similarly, smelting in bloomery-type furnaces appear in the Nok culture of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.[6][7][86][dubious – discuss][80][85]

There is also evidence that carbon steel was made in Western Tanzania by the ancestors of the Haya people as early as 2,300 to 2,000 years ago (about 300 BC or soon after) by a complex process of "pre-heating" allowing temperatures inside a furnace to reach 1300 to 1400 °C.[87][88][89][90][91][92]

Iron and copper working spread southward through the continent, reaching the Cape around AD 200.[6][7] The widespread use of iron revolutionized the Bantu-speaking farming communities who adopted it, driving out and absorbing the rock tool using hunter-gatherer societies they encountered as they expanded to farm wider areas of savanna. The technologically superior Bantu-speakers spread across southern Africa and became wealthy and powerful, producing iron for tools and weapons in large, industrial quantities.[6][7]

The earliest records of bloomery-type furnaces in East Africa are discoveries of smelted iron and carbon in Nubia that date back between the 7th and 6th centuries BC,[93][94][95] particularly in Meroe where there are known to have been ancient bloomeries that produced metal tools for the Nubians and Kushites and produced surplus for their economy.

Medieval Islamic world

[edit]Iron technology was further advanced by several inventions in medieval Islam, during the Islamic Golden Age. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Muslim world had these industrial mills in operation, from Islamic Spain and North Africa in the west to the Middle East and Central Asia in the east.[96] There are also 10th-century references to cast iron, as well as archeological evidence of blast furnaces being used in the Ayyubid and Mamluk empires from the 11th century, thus suggesting a diffusion of Chinese metal technology to the Islamic world.[97]

One of the most famous steels produced in the medieval Near East was Damascus steel used for swordmaking, and mostly produced in Damascus, Syria, in the period from 900 to 1750. This was produced using the crucible steel method, based on the earlier Indian wootz steel. This process was adopted in the Middle East using locally produced steels. The exact process remains unknown, but it allowed carbides to precipitate out as micro particles arranged in sheets or bands within the body of a blade. Carbides are far harder than the surrounding low carbon steel, so swordsmiths could produce an edge that cut hard materials with the precipitated carbides, while the bands of softer steel let the sword as a whole remain tough and flexible. A team of researchers based at the Technical University of Dresden that uses X-rays and electron microscopy to examine Damascus steel discovered the presence of cementite nanowires[98] and carbon nanotubes.[99] Peter Paufler, a member of the Dresden team, says that these nanostructures give Damascus steel its distinctive properties[100] and are a result of the forging process.[100][31]

Medieval and early modern Europe

[edit]There was no fundamental change in the technology of iron production in Europe for many centuries. European metal workers continued to produce iron in bloomeries. However, the Medieval period brought two developments—the use of water power in the bloomery process in various places (outlined above), and the first European production in cast iron.

Powered bloomeries

[edit]Sometime in the medieval period, water power was applied to the bloomery process. It is possible that this was at the Cistercian Abbey of Clairvaux as early as 1135, but it was certainly in use in early 13th century France and Sweden.[101] In England, the first clear documentary evidence for this is the accounts of a forge of the Bishop of Durham, near Bedburn in 1408,[102] but that was certainly not the first such ironworks. In the Furness district of England, powered bloomeries were in use into the beginning of the 18th century, and near Garstang until about 1770.

The Catalan Forge was a variety of powered bloomery. Bloomeries with hot blast were used in upstate New York in the mid-19th century.

Blast furnace

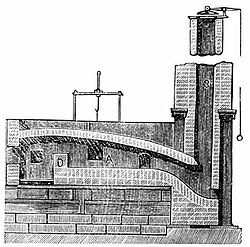

[edit]

The preferred method of iron production in Europe until the development of the puddling process in 1783–84. Cast iron development lagged in Europe because wrought iron was the desired product and the intermediate step of producing cast iron involved an expensive blast furnace and further refining of pig iron to cast iron, which then required a labor and capital intensive conversion to wrought iron.[11]

Through a good portion of the Middle Ages, in Western Europe, iron was still being made by the working of iron blooms into wrought iron. Some of the earliest casting of iron in Europe occurred in Sweden, in two sites, Lapphyttan and Vinarhyttan, between 1150 and 1350. Some scholars have speculated the practice followed the Mongols across Russia to these sites, but there is no clear proof of this hypothesis, and it would certainly not explain the pre-Mongol datings of many of these iron-production centres. In any event, by the late 14th century, a market for cast iron goods began to form, as a demand developed for cast iron cannonballs.

Finery forge

[edit]An alternative method of decarburising pig iron was the finery forge, which seems to have been devised in the region around Namur in the 15th century. By the end of that century, this Walloon process spread to the Pay de Bray on the eastern boundary of Normandy, and then to England, where it became the main method of making wrought iron by 1600. It was introduced to Sweden by Louis de Geer in the early 17th century and was used to make the oregrounds iron favoured by English steelmakers.

A variation on this was the German forge. This became the main method of producing bar iron in Sweden.

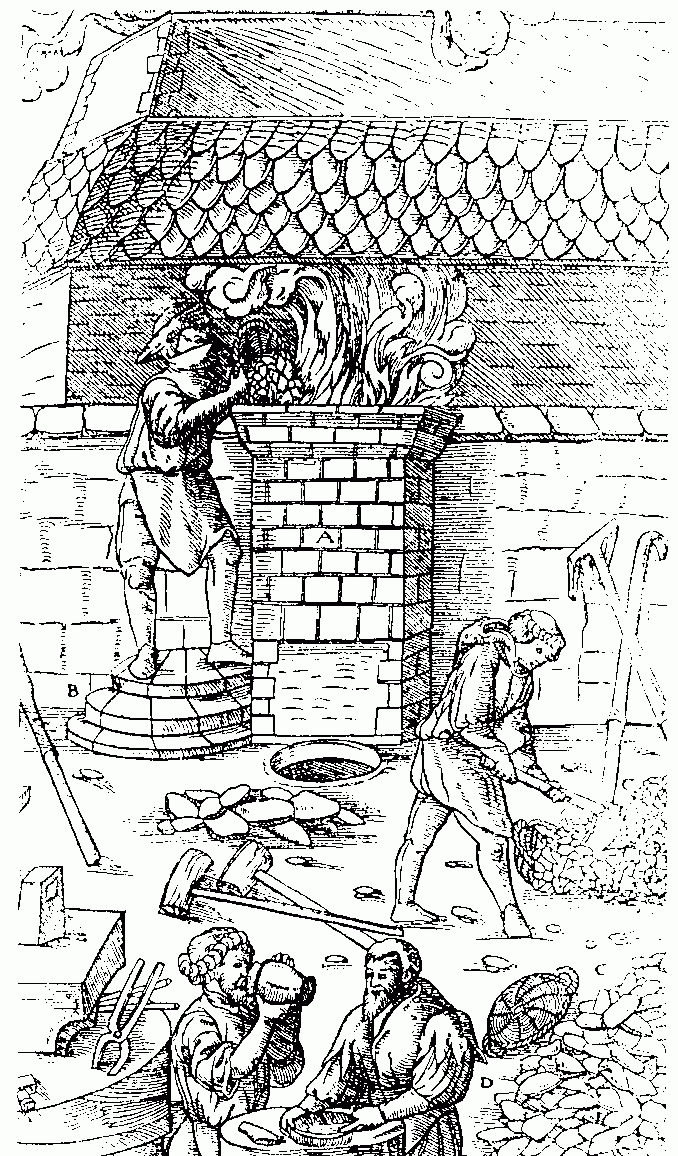

Cementation process

[edit]In the early 17th century, ironworkers in Western Europe had developed the cementation process for carburizing wrought iron. Wrought iron bars and charcoal were packed into stone boxes, then sealed with clay to be held at a red heat continually tended in an oxygen-free state immersed in nearly pure carbon (charcoal) for up to a week. During this time, carbon diffused into the surface layers of the iron, producing cement steel or blister steel—also known as case hardened, where the portions wrapped in iron (the pick or axe blade) became harder, than say an axe hammer-head or shaft socket which might be insulated by clay to keep them from the carbon source. The earliest place where this process was used in England was at Coalbrookdale from 1619, where Sir Basil Brooke had two cementation furnaces (recently excavated in 2001–2005[103]). For a time in the 1610s, he owned a patent on the process, but had to surrender this in 1619. He probably used Forest of Dean iron as his raw material, but it was soon found that oregrounds iron was more suitable. The quality of the steel could be improved by faggoting, producing the so-called shear steel.

Crucible steel

[edit]In the 1740s, Benjamin Huntsman found a means of melting blister steel, made by the cementation process, in crucibles. The resulting crucible steel, usually cast in ingots, was more homogeneous than blister steel.[11]: 145

Transition to coke in England

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]Early iron smelting used charcoal as both the heat source and the reducing agent. By the 18th century, the availability of wood for making charcoal was limiting the expansion of iron production, so that England became increasingly dependent for a considerable part of the iron required by its industry, on Sweden (from the mid-17th century) and then from about 1725 also on Russia.[citation needed] Smelting with coal (or its derivative coke) was a long sought objective. The production of pig iron with coke was probably achieved by Dud Dudley around 1619,[104] and with a mixed fuel made from coal and wood again in the 1670s. However this was probably only a technological rather than a commercial success. Shadrach Fox may have smelted iron with coke at Coalbrookdale in Shropshire in the 1690s, but only to make cannonballs and other cast iron products such as shells. However, in the peace after the Nine Years War, there was no demand for these.[105][106]

Abraham Darby and his successors

[edit]In 1707, Abraham Darby I patented a method of making cast iron pots. His pots were thinner and hence cheaper than those of his rivals. Needing a larger supply of pig iron he leased the blast furnace at Coalbrookdale in 1709. There, he made iron using coke, thus establishing the first successful business in Europe to do so. His products were all of cast iron, though his immediate successors attempted (with little commercial success) to fine this to bar iron.[107]

Bar iron thus continued normally to be made with charcoal pig iron until the mid-1750s. In 1755 Abraham Darby II (with partners) opened a new coke-using furnace at Horsehay in Shropshire, and this was followed by others. These supplied coke pig iron to finery forges of the traditional kind for the production of bar iron. The reason for the delay remains controversial.[108]

New forge processes

[edit]

It was only after this that economically viable means of converting pig iron to bar iron began to be devised. A process known as potting and stamping was devised in the 1760s and improved in the 1770s, and seems to have been widely adopted in the West Midlands from about 1785. However, this was largely replaced by Henry Cort's puddling process, patented in 1784, but probably only made to work with grey pig iron in about 1790. These processes permitted the great expansion in the production of iron that constitutes the Industrial Revolution for the iron industry.[109]

In the early 19th century, Hall discovered that the addition of iron oxide to the charge of the puddling furnace caused a violent reaction, in which the pig iron was decarburised, this became known as 'wet puddling'. It was also found possible to produce steel by stopping the puddling process before decarburisation was complete.

Hot blast

[edit]The efficiency of the blast furnace was improved by the change to hot blast, patented by James Beaumont Neilson in Scotland in 1828.[104] This further reduced production costs. Within a few decades, the practice was to have a 'stove' as large as the furnace next to it into which the waste gas (containing CO) from the furnace was directed and burnt. The resultant heat was used to preheat the air blown into the furnace.[110]

Industrial steelmaking

[edit]

Apart from some production of puddled steel, English steel continued to be made by the cementation process, sometimes followed by remelting to produce crucible steel. These were batch-based processes whose raw material was bar iron, particularly Swedish oregrounds iron.

The problem of mass-producing cheap steel was solved in 1855 by Henry Bessemer, with the introduction of the Bessemer converter at his steelworks in Sheffield, England. (An early converter can still be seen at the city's Kelham Island Museum). In the Bessemer process, molten pig iron from the blast furnace was charged into a large crucible, and then air was blown through the molten iron from below, igniting the dissolved carbon from the coke. As the carbon burned off, the melting point of the mixture increased, but the heat from the burning carbon provided the extra energy needed to keep the mixture molten. After the carbon content in the melt had dropped to the desired level, the air draft was cut off: a typical Bessemer converter could convert a 25-ton batch of pig iron to steel in half an hour.

In the 1860s development of regenerative furnaces and higher temperature refractory lining allowed to melt steel in an open hearth. That was slow and energy intensive, but allowed to better control the chemical makeup of the product and recycle iron scrap.

The acidic refractory lining of Bessemer converters and early open hearths didn't allow to remove phosphorus from steel with lime, which prolonged the life of puddling furnaces in order to utilize phosphorous iron ores abundant in Continental Europe. However, in the 1870s Gilchrist–Thomas process was developed, and later basic lining was adopted for the open hearths as well.

Finally, the basic oxygen process was introduced at the Voest-Alpine works in 1952; a modification of the basic Bessemer process, it lances oxygen from above the steel (instead of bubbling air from below), reducing the amount of nitrogen uptake into the steel. The basic oxygen process is used in all modern steelworks; the last Bessemer converter in the U.S. was retired in 1968. Furthermore, the last three decades have seen a massive increase in the mini-mill business, where scrap steel only is melted with an electric arc furnace. These mills only produced bar products at first, but have since expanded into flat and heavy products, once the exclusive domain of the integrated steelworks.

Until these 19th-century developments, steel was an expensive commodity and only used for a limited number of purposes where a particularly hard or flexible metal was needed, as in the cutting edges of tools and springs. The widespread availability of inexpensive steel powered the Second Industrial Revolution and modern society as we know it. Mild steel ultimately replaced wrought iron for almost all purposes, and wrought iron is no longer commercially produced. With minor exceptions, alloy steels only began to be made in the late 19th century. Stainless steel was developed on the eve of World War I and was not widely used until the 1920s.

Modern steel industry

[edit]

The steel industry is often considered an indicator of economic progress, because of the critical role played by steel in infrastructural and overall economic development.[111] In 1980, there were more than 500,000 U.S. steelworkers. By 2000, the number of steelworkers had fallen to 224,000.[112]

The economic boom in China and India caused a massive increase in the demand for steel. Between 2000 and 2005, world steel demand increased by 6%. Since 2000, several Indian[113] and Chinese steel firms have risen to prominence,[according to whom?] such as Tata Steel (which bought Corus Group in 2007), Baosteel Group and Shagang Group. As of 2017[update], though, ArcelorMittal is the world's largest steel producer.[114] In 2005, the British Geological Survey stated China was the top steel producer with about one-third of the world share; Japan, Russia, and the US followed respectively.[115]

The large production capacity of steel results in a significant amount of carbon dioxide emissions inherent related to the main production route. In 2019, it was estimated that 7 to 9% of the global carbon dioxide emissions resulted from the steel industry.[116] Reduction of these emissions are expected to come from a shift in the main production route using cokes, more recycling of steel and the application of carbon capture and storage or carbon capture and utilization technology.

In 2008, steel began trading as a commodity on the London Metal Exchange. At the end of 2008, the steel industry faced a sharp downturn that led to many cut-backs.[117]

See also

[edit]- Bintie, a type of refined iron

- History of steelmaking

- Iron Age

- List of alloys

- Nok culture

- Non-ferrous extractive metallurgy

- Roman metallurgy

Citations

[edit]- ^ Rehren, T. (2013). "5,000 years old Egyptian iron beads made from hammered meteoritic iron" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (12): 4785–4792. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.4785R. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.002.

- ^ a b c d e f Photos, E. (1989). "The Question of Meteoritic versus Smelted Nickel-Rich Iron: Archaeological Evidence and Experimental Results". World Archaeology. 20 (3): 403–421. doi:10.1080/00438243.1989.9980081. JSTOR 124562. S2CID 5908149.

- ^ Riederer, Josef; Wartke, Ralf-B.: "Iron", Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.): Brill's New Pauly, Brill 2009

- ^ a b c Early Antiquity By I.M. Drakonoff. 1991. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14465-8. p. 372

- ^ Rao, Kp (2018). "Iron Age in South India: Telangana and Andhra Pradesh". In Uesugi, Akinori (ed.). Iron Age in South Asia. Research Group for South Asian Archaeology. ISBN 978-4-9909150-1-8. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Duncan E.; van der Merwe, N.J. (1994). "Early Metal Working in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Recent Research". Journal of African History. 35: 1–36. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025949. S2CID 162330270.

- ^ a b c d Stuiver, Minze; van der Merwe, N.J. (1968). "Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa". Current Anthropology. 9: 54–58. doi:10.1086/200878. S2CID 145379030.

- ^ Waldbaum (1978).

- ^ a b c Donald B. Wagner (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China. Brill. p. 408. ISBN 978-90-04-09632-5.

- ^ Williams, David (1867), "The Iron Age [weekly journal]", Iron Age, New York: David Williams, ISSN 0021-1508, LCCN sc82008005, OCLC 5257259

- ^ a b c Tylecote (1992).

- ^ a b Tylecote (1992). p. 3.

- ^ Veenhof, Klaas; Eidem, Jesper (2008). Mesopotamia : Annäherungen. Saint-Paul. p. 84. ISBN 978-3-525-53452-6.

- ^ a b Waldbaum (1978). pp. 56–58.

- ^ a b c Marco Ceccarelli (2000). International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms: Proceedings HMM Symposium. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-6372-8. p. 218

- ^ White, W. C.: "Bronze Culture of Ancient China", p. 208. University of Toronto Press, 1956.

- ^ Collins, Rober O. and Burns, James M. The History of Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-68708-9.

- ^ Liu, Y.; Wood, J. (2025). "Questioning Diversity (of Iron) in the Workplace: Bloomery Iron, Cast Iron, China and the West". Internet Archaeology (69). doi:10.11141/ia.69.14.

- ^ The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen: Discovered by the Late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter, Volume 3

- ^ Richard Cowen, The Age of Iron, Chapter 5 in a series of essays on Geology, History, and People prepares for a course of the University of California at Davis. Online version Archived 2010-03-14 at the Wayback Machine accessed on 2010-02-11.

- ^ a b Waldbaum (1978): 23.

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (2016). Still the Iron Age. Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0128042335.

- ^ a b c Muhly, James D. 'Metalworking/Mining in the Levant' pp. 174–183 in Near Eastern Archaeology ed. Suzanne Richard (2003), pp. 179–180.

- ^ Muhly 2003: 180.

- ^ a b Tewari, Rakesh (2003). "The origins of iron-working in India: new evidence from the Central Ganga Plain and the Eastern Vindhyas" (PDF). Antiquity. 77 (297): 536–544. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.4300. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00092590. S2CID 14951163. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-05.

- ^ J. F. Richards et al. (2005).The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36424-8. p. 64

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (1998). Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283576-9. p. xxix

- ^ a b c Will Durant (), The Story of Civilization I: Our Oriental Heritage

- ^ a b c G. Juleff (1996). "An ancient wind powered iron smelting technology in Sri Lanka". Nature. 379 (3): 60–63. Bibcode:1996Natur.379...60J. doi:10.1038/379060a0. S2CID 205026185.

- ^ "Suspension bridge – engineering". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16.

- ^ a b Sanderson, Katharine (2006-11-15). "Sharpest cut from nanotube sword: Carbon nanotech may have given swords of Damascus their edge". Nature. doi:10.1038/news061113-11. S2CID 136774602. Archived from the original on 2006-11-19. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- ^ Roy Porter (2003). The Cambridge History of Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57199-5. p. 684

- ^ Juleff, G. (1996). "An ancient wind powered iron smelting technology in Sri Lanka". Nature. 379 (3): 60–63. Bibcode:1996Natur.379...60J. doi:10.1038/379060a0. S2CID 205026185.

- ^ "ANSYS Fluent Software: CFD Simulation". Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ^ Simulation of air flows through a Sri Lankan wind driven furnace, submitted to J. Arch. Sci, 2003.

- ^ R. Balasubramaniam (2002), Delhi Iron Pillar: New Insights. Aryan Books International, Delhi ISBN 81-7305-223-9. "Review: Delhi Iron Pillar: New Insights". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-04-27. "List of Publications on Indian Archaeometallurgy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-12. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ Rawson, Jessica (April 2017). "China and the steppe: reception and resistance". Antiquity. 91 (356): 375–388. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.276.

The development of several key technologies in China —bronze and iron metallurgy and horse-drawn chariots— arose out of the relations of central China, of the Erlitou period (c. 1700–1500 BC), the Shang (c.1500–1046 BC) and the Zhou (1046–771 BC) dynasties, with their neighbours in the steppe.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (11 December 2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B. Tauris. p. 122. ISBN 978-1780760605.

- ^ Wan, Xiang (2011). "Early development of bronze metallurgy in Eastern Eurasia". Sino-Platonic Papers. 213: 4–5.

The metal-using Afanasievo culture is probably the origin of bronze metallurgy in Northwest China." (...) "Therefore it is conspicuous that one of the earliest bronze cultures in China, the Qijia culture, might well have borrowed its bronze metallurgy from the Steppe, via Siba, Tianshanbeilu, and cultures in the Altai region.

- ^ Chen, Jianli, Mao, Ruilin, Wang, Hui, Chen, Honghai, Xie, Yan, Qian, Yaopeng, 2012. The iron objects unearthed from tombs of the Siwa culture in Mogou, Gansu, and the origin of iron-making technology in China. Wenwu (Cult. Relics) 8, 45–53 (in Chinese)

- ^ p. xl, Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Warfare, J, Woronoff & I. Spence

- ^ Wengcheong Lam (2014). Everything Old is New Again? Rethinking the Transition to Cast Iron Production in the Central Plains of China. Chinese University of Hong Kong. p. 519.

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 197.

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 277.

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 563 g

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 3, p. 86.

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 1, p. 282.

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 2, p. 370.

- ^ Needham (1986). Vol. 4, Part 2, p. 371.

- ^ Hartwell, Robert (1966). "Markets, Technology and the Structure of Enterprise in the Development of the Eleventh Century Chinese Iron and Steel Industry". Journal of Economic History. 26: 53–54. doi:10.1017/S0022050700061842. S2CID 154556274.

- ^ a b (2006). 158.

- ^ "Early Iron in Eastern Europe". topoi.org.

- ^ a b Anthony, David (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

One unappreciated aspect of Early Bronze Age and Middle Bronze Age steppe metallurgy was its experimentation with iron. … A Catacomb-period grave at Gerasimovka on the Donets (western Russia/Ukraine), probably dated around 2500 BCE, contained a knife with a handle made of arsenical bronze and a blade made of iron. The iron did not contain magnetite or nickel, as would be expected in meteoric iron, so it is thought to have been forged. Iron objects were rare, but they were part of the experiments conducted by steppe metalsmiths during the Early and Middle Bronze Ages

- ^ "Early Iron in Eastern Europe". topoi.org.

- ^ a b c Kašuba, Maja; et al. (2019). "Eisenmetallurgie in der Bronzezeit Osteuropas. Die archäologischen Quellen und ihre Interpretation". Praehistorische Zeitschrift. 94 (1): 158–209. doi:10.1515/pz-2019-0001.

- ^ "The Iron Age". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Hansen, Svend (2019). "The Hillfort of Teleac and Early Iron in Southern Europe". In Hansen, Svend; Krause, Rüdiger (eds.). Bronze Age Fortresses in Europe. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. p. 204.

- ^ Furmánek, Václav (2000). "Eine Eisensichel aus Gánovce. Zur Interpretation des ältesten Eisengegenstandes in Mitteleuropa". Praehistorische Zeitschrift. 75: 153–160. doi:10.1515/prhz.2000.75.2.153.

- ^ Turnbull, Anne (1984). From bronze to iron : The occurrence of iron in the British later Bronze Age (PhD). Edinburgh University. p. 24. S2CID 164098953.

- ^ "Life and Belief in the Bronze Age: Belt Disc from Heegermühle". Neues Museum.

- ^ "Der Depotfund von Heegermühle bei Eberswalde". askanier-welten.de.

- ^ Hansen, Svend (2019). "The Hillfort of Teleac and Early Iron in Southern Europe". In Hansen, Svend; Krause, Rüdiger (eds.). Bronze Age Fortresses in Europe. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. pp. 204–206.

- ^ Hansen, Svend (2019). "The Hillfort of Teleac and Early Iron in Southern Europe". In Hansen, Svend; Krause, Rüdiger (eds.). Bronze Age Fortresses in Europe. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. p. 214.

- ^ Hansen, Svend (2019). "The Hillfort of Teleac and Early Iron in Southern Europe". In Hansen, Svend; Krause, Rüdiger (eds.). Bronze Age Fortresses in Europe. Verlag Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn. p. 211.

- ^ a b Wells, Peter (1995). "Resources and Industry". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 218. ISBN 9781135632434.

- ^ Skóra, Kalina; et al. (2019). "Weaponry of the Przeworsk Culture in the light of metallographic examinations. The case of the cemetery in Raczkowice". Praehistorische Zeitschrift. 94 (2): 1–45. doi:10.1515/pz-2019-0016.

In Pre-Roman Period Europe one can see a strong diversification of sword blade technologies. There are many low quality blades made from iron or low-carbon steel; on the other hand, one also encounters artefacts made partially or entirely from high-carbon steel.

- ^ COLLARD, Mark; et al. (2006). "Ironworking in the Bronze Age? Evidence from a 10th Century BC Settlement at Hartshill Copse, Upper Bucklebury, West Berkshire". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 72: 367–421. doi:10.1017/S0079497X0000089X.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry W. (2005). Iron Age Communities in Britain: An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC Until the Roman Conquest (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 0-415-34779-3.

- ^ "East Lothian's Broxmouth fort reveals edge of steel". BBC News. 15 January 2014.

- ^ Lund, Julie; Melheim, Lene (2011). "Heads and Tails – Minds and Bodies: Reconsidering the Late Bronze Age Vestby Hoard". European Journal of Archaeology. 14 (3): 441–464. doi:10.1179/146195711798356692.

iron technology was practiced in the Nordic region from at least the ninth century BC (Hjärthner-Holdar 1993; Serning 1984)

- ^ a b Bennerhag, Carina; et al. (2021). "Hunter-gatherer metallurgy in the Early Iron Age of Northern Fennoscandia". Antiquity. 95 (384): 1511–1526. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.248.

- ^ Giardino, Claudio (2005). "Metallurgy in Italy between the Late Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age: the Coming of Iron". Papers in Italian Archaeology VI, Vol. I. Archaeopress. pp. 491–505.

- ^ Lo Schiavo, Fulvio (2005). "The First Iron in Sardinia". Archaeometallurgy in Sardinia (PDF). Editions Monique Mergoil. pp. 401–406. ISBN 2-907303-89-9.

- ^ "Steel was being used in Europe 2900 years ago". sciencedaily.com. 2023.

- ^ "Stone-working and the earliest steel in Iberia: Scientific analyses and experimental replications of final bronze age stelae and tools (Gonzalez et al. 2023)".

- ^ Presslinger, Hubert; et al. (2005). "Norican Steel - An Assessment of the Archaeological Finds at the Magdalensberg Site, Carinthia, Compared to the "Celtic Trove" of Gründberg Hill, Linz". Steel Research International. 76 (9).

- ^ Craddock, Paul T. (2008): "Mining and Metallurgy", in: Oleson, John Peter (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1, p. 108

- ^ Godfrey, Evelyne; van Nie, Matthijs (2004). "A Germanic ultrahigh carbon steel punch of the Late Roman-Iron Age". Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (8): 1117–1125. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.02.002.

- ^ a b Bandama, Foreman; Babalola, Abidemi Babatunde (13 September 2023). "Science, Not Black Magic: Metal and Glass Production in Africa". African Archaeological Review. 40 (3): 531–543. doi:10.1007/s10437-023-09545-6. ISSN 0263-0338. OCLC 10004759980. S2CID 261858183.

- ^ a b Eggert (2014). pp. 51–59.

- ^ a b c Holl, Augustin F. C. (6 November 2009). "Early West African Metallurgies: New Data and Old Orthodoxy". Journal of World Prehistory. 22 (4): 415–438. doi:10.1007/s10963-009-9030-6. S2CID 161611760.

- ^ Iron in Africa: Revisiting the History Archived 2008-10-25 at the Wayback Machine – Unesco (2002)

- ^ Ehret, Christopher (2002). The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, pp. 136, 137 ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- ^ Eze–Uzomaka, Pamela. "Iron and its influence on the prehistoric site of Lejja". Academia.edu. University of Nigeria,Nsukka, Nigeria. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ a b Eggert (2014). pp. 53–54.

- ^ Tylecote (1975) (see below)

- ^ Schmidt, Peter; Avery, Donald (1978). "Complex Iron Smelting and Prehistoric Culture in Tanzania". Science. 201 (4361): 1085–1089. Bibcode:1978Sci...201.1085S. doi:10.1126/science.201.4361.1085. JSTOR 1746308. PMID 17830304. S2CID 37926350.

- ^ Schmidt, Peter; Avery, Donald (1983). "More Evidence for an Advanced Prehistoric Iron Technology in Africa". Journal of Field Archaeology. 10 (4): 421–434. doi:10.1179/009346983791504228.

- ^ Schmidt, Peter (1978). Historical Archaeology: A Structural Approach in an African Culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- ^ Avery, Donald; Schmidt, Peter (1996). "Preheating: Practice or illusion". The Culture and Technology of African Iron Production. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. pp. 267–276.

- ^ Schmidt, Peter (2019). "Science in Africa: A history of ingenuity and invention in African iron technology". In Worger, W; Ambler, C; Achebe, N (eds.). A Companion to African History. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 267–288.

- ^ Childs, S. Terry (1996). "Technological history and culture in western Tanzania". In Schmidt, P. (ed.). The Culture and Technology of African Iron Production. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press.

- ^ Collins, Robert O.; Burns, James M. (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521867467 – via Google Books.

- ^ Edwards, David N. (2004). The Nubian Past: An Archaeology of the Sudan. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0203482766 – via Google Books.

- ^ Humphris J, Charlton MF, Keen J, Sauder L, Alshishani F (June 2018). "Iron Smelting in Sudan: Experimental Archaeology at The Royal City of Meroe". Journal of Field Archaeology. 43 (5): 399–416. doi:10.1080/00934690.2018.1479085.

- ^ Lucas 2005, p. 10–11, 27.

- ^ R. L. Miller (October 1988). "Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan and Donald R. Hill, 'Islamic technology: an illustrated history'". Medical History. 32 (4): 466–467. doi:10.1017/s0025727300048602.

- ^ Kochmann, W.; Reibold M.; Goldberg R.; Hauffe W.; Levin A. A.; Meyer D. C.; Stephan T.; Müller H.; Belger A.; Paufler P. (2004). "Nanowires in ancient Damascus steel". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 372 (1–2): L15 – L19. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2003.10.005. ISSN 0925-8388.

Levin, A. A.; Meyer D. C.; Reibold M.; Kochmann W.; Pätzke N.; Paufler P. (2005). "Microstructure of a genuine Damascus sabre" (PDF). Crystal Research and Technology. 40 (9): 905–916. Bibcode:2005CryRT..40..905L. doi:10.1002/crat.200410456. S2CID 96560374. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-08-09. - ^ Reibold, M.; Levin A. A.; Kochmann W.; Pätzke N.; Meyer D. C. (16 November 2006). "Materials:Carbon nanotubes in an ancient Damascus sabre". Nature. 444 (7117): 286. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..286R. doi:10.1038/444286a. PMID 17108950. S2CID 4431079.

- ^ a b "Legendary Swords' Sharpness, Strength From Nanotubes, Study Says". news.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28.

- ^ Lucas 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Tylecote (1992). p. 76.

- ^ Belford and Ross, Paper: English steelmaking in the seventeenth century: the excavation of two cementation furnaces at Coalbrookdale Archived 2018-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, Academia.edu, accessdate=30 March 2017

- ^ a b Howe, Henry Marion (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 803.

- ^ King, P. W. (2002). "Dud Dudley's contribution to metallurgy". Historical Metallurgy. 36 (1): 43–53.

- ^ King, P. W. (2001). "Sir Clement Clerke and the adoption of coal in metallurgy". Trans. Newcomen Soc. 73 (1): 33–52. doi:10.1179/tns.2001.002. S2CID 112533187.

- ^ A. Raistrick, A dynasty of Ironfounders (1953; 1989); N. Cox, 'Imagination and innovation of an industrial pioneer: The first Abraham Darby' Industrial Archaeology Review 12(2) (1990), 127–144.

- ^ A. Raistrick, Dynasty; C. K. Hyde, Technological change and the British iron industry 1700–1870 (Princeton, 1977), 37–41; P. W. King, 'The Iron Trade in England and Wales 1500–1815' (Ph.D. thesis, Wolverhampton University, 2003), 128–141.

- ^ G. R. Morton and N. Mutton, 'The transition to Cort's puddling process' Journal of Iron and Steel Institute 205(7) (1967), 722–728; R. A. Mott (ed. P. Singer), Henry Cort: The great finer: creator of puddled iron (1983); P. W. King, 'Iron Trade', 185–193.

- ^ A. Birch, Economic History of the British Iron and Steel Industry , 181–189; C. K. Hyde, Technological Change and the British iron industry (Princeton 1977), 146–159.

- ^ "Steel Industry". Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ^ "Congressional Record V. 148, Pt. 4, April 11, 2002 to April 24, 2002". United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ Chopra, Anuj (12 February 2007). "India's steel industry steps onto world stage". Cristian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ^ "Top Steelmakers in 2017" (PDF). World Steel Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ "Long-term planning needed to meet steel demand". The News. 2008-03-01. Archived from the original on 2024-05-25. Retrieved 2010-11-02.

- ^ De Ras, Kevin; Van De Vijver, Ruben; Galvita, Vladimir V.; Marin, Guy B.; Van Geem, Kevin M. (2019-12-01). "Carbon capture and utilization in the steel industry: challenges and opportunities for chemical engineering" (PDF). Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering. 26: 81–87. Bibcode:2019COCE...26...81D. doi:10.1016/j.coche.2019.09.001. hdl:1854/LU-8635595. ISSN 2211-3398. S2CID 210619173.

- ^ Uchitelle, Louis (2009-01-01). "Steel Industry, in Slump, Looks to Federal Stimulus". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.[ISBN missing]

- Eggert, Manfred (2014). "Early iron in West and Central Africa". In Breunig, P (ed.). Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt: Africa Magna Verlag Press. ISBN 978-3937248462. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- Lucas, Adam Robert (2005). "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe". Technology and Culture. 46 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1353/tech.2005.0026. S2CID 109564224.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 2; Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3.

- Tylecote, R. F. (1992). A History of Metallurgy (2nd ed.). London: Maney Publishing, for the Institute of Materials. ISBN 978-0901462886.

- Waldbaum, Jane C. (1978). From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. LIV. Gothenburg: Paul Åström. ISBN 9185058793.

Further reading

[edit]- Knowles, Anne Kelly. (2013). Mastering Iron: The Struggle to Modernize an American Industry, 1800–1868 (University of Chicago Press) 334 pages [ISBN missing]

- Lam, Wengcheong (2014). Everything Old is New Again? Rethinking the transition to Cast Iron Production in the Plains of Central China, Chinese University of Hong Kong [ISBN missing]

- Pleiner, R. (2000). Iron in Archaeology. The European Bloomery Smelters, Praha, Archeologický Ústav Av Cr. [ISBN missing]

- Pounds, Norman J. G. (1957). "Historical Geography of the Iron and Steel Industry of France". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 47#1, pp. 3–14. JSTOR 2561556.

- Wagner, Donald (1996). Iron and Steel in Ancient China. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [ISBN missing]

- Woods, Michael and Mary B. Woods (2000). Ancient Construction (Ancient Technology) Runestone Press [ISBN missing]

External links

[edit]- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.