Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Telegraphy

View on Wikipedia

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas pigeon post is not. Ancient signalling systems, although sometimes quite extensive and sophisticated as in China, were generally not capable of transmitting arbitrary text messages. Possible messages were fixed and predetermined, so such systems are thus not true telegraphs.

The earliest true telegraph put into widespread use was the Chappe telegraph, an optical telegraph invented by Claude Chappe in the late 18th century. The system was used extensively in France, and European nations occupied by France, during the Napoleonic era. The electric telegraph started to replace the optical telegraph in the mid-19th century. It was first taken up in Britain in the form of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, initially used mostly as an aid to railway signalling. This was quickly followed by a different system developed in the United States by Samuel Morse. The electric telegraph was slower to develop in France due to the established optical telegraph system, but an electrical telegraph was put into use with a code compatible with the Chappe optical telegraph. The Morse system was adopted as the international standard in 1865, using a modified Morse code developed in Germany in 1848.[1]

The heliograph is a telegraph system using reflected sunlight for signalling. It was mainly used in areas where the electrical telegraph had not been established and generally used the same code. The most extensive heliograph network established was in Arizona and New Mexico during the Apache Wars. The heliograph was standard military equipment as late as World War II. Wireless telegraphy developed in the early 20th century became important for maritime use, and was a competitor to electrical telegraphy using submarine telegraph cables in international communications.

Telegrams became a popular means of sending messages once telegraph prices had fallen sufficiently. Traffic became high enough to spur the development of automated systems—teleprinters and punched tape transmission. These systems led to new telegraph codes, starting with the Baudot code. However, telegrams were never able to compete with the letter post on price, and competition from the telephone, which removed their speed advantage, drove the telegraph into decline from 1920 onwards. The few remaining telegraph applications were largely taken over by alternatives on the internet towards the end of the 20th century.

Terminology

[edit]The word telegraph (from Ancient Greek: τῆλε (têle) 'at a distance' and γράφειν (gráphein) 'to write') was coined by the French inventor of the semaphore telegraph, Claude Chappe, who also coined the word semaphore.[2]

A telegraph is a device for transmitting and receiving messages over long distances, i.e., for telegraphy. The word telegraph alone generally refers to an electrical telegraph. Wireless telegraphy is transmission of messages over radio with telegraphic codes.

Contrary to the extensive definition used by Chappe, Morse argued that the term telegraph can strictly be applied only to systems that transmit and record messages at a distance. This is to be distinguished from semaphore, which merely transmits messages. Smoke signals, for instance, are to be considered semaphore, not telegraph. According to Morse, telegraph dates only from 1832 when Pavel Schilling invented one of the earliest electrical telegraphs.[3]

A telegraph message sent by an electrical telegraph operator or telegrapher using Morse code (or a printing telegraph operator using plain text) was known as a telegram. A cablegram was a message sent by a submarine telegraph cable,[4] often shortened to "cable" or "wire". The suffix -gram is derived from ancient Greek: γραμμα (gramma), meaning something written, i.e. telegram means something written at a distance and cablegram means something written via a cable, whereas telegraph implies the process of writing at a distance.

Later, a Telex was a message sent by a Telex network, a switched network of teleprinters similar to a telephone network.

A wirephoto or wire picture was a newspaper picture that was sent from a remote location by a facsimile telegraph. A diplomatic telegram, also known as a diplomatic cable, is a confidential communication between a diplomatic mission and the foreign ministry of its parent country.[5][6] These continue to be called telegrams or cables regardless of the method used for transmission.

History

[edit]Early signalling

[edit]

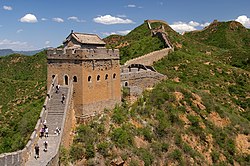

Passing messages by signalling over distance is an ancient practice. One of the oldest examples is the signal towers of the Great Wall of China. By 400 BC, signals could be sent by beacon fires or drum beats, and by 200 BC complex flag signalling had developed. During the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), signallers mainly used flags and wood fires—via the light of the flames swung high into the air at night, and via dark smoke produced by the addition of wolf dung during the day—to send signals.[7] By the Tang dynasty (618–907) a message could be sent 1,100 kilometres (700 mi) in 24 hours. The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) used artillery as another possible signalling method. While the signalling was complex (for instance, flags of different colours could be used to indicate enemy strength), only predetermined messages could be sent.[8] The Chinese signalling system extended well beyond the Great Wall. Signal towers away from the wall were used to give early warning of an attack. Others were built even further out as part of the protection of trade routes, especially the Silk Road.[9]

Signal fires were widely used in Europe and elsewhere for military purposes. The Roman army made frequent use of them, as did their enemies, and the remains of some of the stations still exist. Few details have been recorded of European/Mediterranean signalling systems and the possible messages. One of the few for which details are known is a system invented by Aeneas Tacticus (4th century BC). Tacticus's system had water filled pots at the two signal stations which were drained in synchronisation. Annotation on a floating scale indicated which message was being sent or received. Signals sent by means of torches indicated when to start and stop draining to keep the synchronisation.[10]

None of the signalling systems discussed above are true telegraphs in the sense of a system that can transmit arbitrary messages over arbitrary distances. Lines of signalling relay stations can send messages to any required distance, but all these systems are limited to one extent or another in the range of messages that they can send. A system like flag semaphore, with an alphabetic code, can certainly send any given message, but the system is designed for short-range communication between two persons. An engine order telegraph, used to send instructions from the bridge of a ship to the engine room, fails to meet both criteria; it has a limited distance and very simple message set. There was only one ancient signalling system described that does meet these criteria. That was a system using the Polybius square to encode an alphabet. Polybius (2nd century BC) suggested using two successive groups of torches to identify the coordinates of the letter of the alphabet being transmitted. The number of said torches held up signalled the grid square that contained the letter. There is no definite record of the system ever being used, but there are several passages in ancient texts that some think are suggestive. Holzmann and Pehrson, for instance, suggest that Livy is describing its use by Philip V of Macedon in 207 BC during the First Macedonian War. Nothing else that could be described as a true telegraph existed until the 17th century.[10][11]: 26–29 Possibly the first alphabetic telegraph code in the modern era is due to Franz Kessler who published his work in 1616. Kessler used a lamp placed inside a barrel with a moveable shutter operated by the signaller. The signals were observed at a distance with the newly invented telescope.[11]: 32–34

Optical telegraph

[edit]

An optical telegraph is a telegraph consisting of a line of stations in towers or natural high points which signal to each other by means of shutters or paddles. Signalling by means of indicator pointers was called semaphore. Early proposals for an optical telegraph system were made to the Royal Society by Robert Hooke in 1684[12] and were first implemented on an experimental level by Sir Richard Lovell Edgeworth in 1767.[13] The first successful optical telegraph network was invented by Claude Chappe and operated in France from 1793.[14] The two most extensive systems were Chappe's in France, with branches into neighbouring countries, and the system of Abraham Niclas Edelcrantz in Sweden.[11]: ix–x, 47

During 1790–1795, at the height of the French Revolution, France needed a swift and reliable communication system to thwart the war efforts of its enemies. In 1790, the Chappe brothers set about devising a system of communication that would allow the central government to receive intelligence and to transmit orders in the shortest possible time. On 2 March 1791, at 11 am, they sent the message "si vous réussissez, vous serez bientôt couverts de gloire" (If you succeed, you will soon bask in glory) between Brulon and Parce, a distance of 16 kilometres (10 mi). The first means used a combination of black and white panels, clocks, telescopes, and codebooks to send their message.

In 1792, Claude was appointed Ingénieur-Télégraphiste and charged with establishing a line of stations between Paris and Lille, a distance of 230 kilometres (140 mi). It was used to carry dispatches for the war between France and Austria. In 1794, it brought news of a French capture of Condé-sur-l'Escaut from the Austrians less than an hour after it occurred.[15] A decision to replace the system with an electric telegraph was made in 1846, but it took a decade before it was fully taken out of service. The fall of Sevastopol was reported by Chappe telegraph in 1855.[11]: 92–94

The Prussian system was put into effect in the 1830s. However, they were highly dependent on good weather and daylight to work and even then could accommodate only about two words per minute. The last commercial semaphore link ceased operation in Sweden in 1880. As of 1895, France still operated coastal commercial semaphore telegraph stations, for ship-to-shore communication.[16]

Electrical telegraph

[edit]

The early ideas for an electric telegraph included in 1753 using electrostatic deflections of pith balls,[17] proposals for electrochemical bubbles in acid by Campillo in 1804 and von Sömmering in 1809.[18][19] The first experimental system over a substantial distance was by Ronalds in 1816 using an electrostatic generator. Ronalds offered his invention to the British Admiralty, but it was rejected as unnecessary,[20] the existing optical telegraph connecting the Admiralty in London to their main fleet base in Portsmouth being deemed adequate for their purposes. As late as 1844, after the electrical telegraph had come into use, the Admiralty's optical telegraph was still used, although it was accepted that poor weather ruled it out on many days of the year.[21]: 16, 37 France had an extensive optical telegraph system dating from Napoleonic times and was even slower to take up electrical systems.[22]: 217–218

Eventually, electrostatic telegraphs were abandoned in favour of electromagnetic systems. An early experimental system (Schilling, 1832) led to a proposal to establish a telegraph between St Petersburg and Kronstadt, but it was never completed.[23] The first operative electric telegraph (Gauss and Weber, 1833) connected Göttingen Observatory to the Institute of Physics about 1 km away during experimental investigations of the geomagnetic field.[24]

The first commercial telegraph was by Cooke and Wheatstone following their English patent of 10 June 1837. It was demonstrated on the London and Birmingham Railway in July of the same year.[25] In July 1839, a five-needle, five-wire system was installed to provide signalling over a record distance of 21 km on a section of the Great Western Railway between London Paddington station and West Drayton.[26][27] However, in trying to get railway companies to take up his telegraph more widely for railway signalling, Cooke was rejected several times in favour of the more familiar, but shorter range, steam-powered pneumatic signalling. Even when his telegraph was taken up, it was considered experimental and the company backed out of a plan to finance extending the telegraph line out to Slough. However, this led to a breakthrough for the electric telegraph, as up to this point the Great Western had insisted on exclusive use and refused Cooke permission to open public telegraph offices. Cooke extended the line at his own expense and agreed that the railway could have free use of it in exchange for the right to open it up to the public.[21]: 19–20

Most of the early electrical systems required multiple wires (Ronalds' system was an exception), but the system developed in the United States by Morse and Vail was a single-wire system. This was the system that first used the soon-to-become-ubiquitous Morse code.[25] By 1844, the Morse system connected Baltimore to Washington, and by 1861 the west coast of the continent was connected to the east coast.[28][29] The Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, in a series of improvements, also ended up with a one-wire system, but still using their own code and needle displays.[26]

The electric telegraph quickly became a means of more general communication. The Morse system was officially adopted as the standard for continental European telegraphy in 1851 with a revised code, which later became the basis of International Morse Code.[30] However, Great Britain and the British Empire continued to use the Cooke and Wheatstone system, in some places as late as the 1930s.[26] Likewise, the United States continued to use American Morse code internally, requiring translation operators skilled in both codes for international messages.[30]

Railway telegraphy

[edit]

Railway signal telegraphy was developed in Britain from the 1840s onward. It was used to manage railway traffic and to prevent accidents as part of the railway signalling system. On 12 June 1837 Cooke and Wheatstone were awarded a patent for an electric telegraph.[31] This was demonstrated between Euston railway station—where Wheatstone was located—and the engine house at Camden Town—where Cooke was stationed, together with Robert Stephenson, the London and Birmingham Railway line's chief engineer. The messages were for the operation of the rope-haulage system for pulling trains up the 1 in 77 bank. The world's first permanent railway telegraph was completed in July 1839 between London Paddington and West Drayton on the Great Western Railway with an electric telegraph using a four-needle system.

The concept of a signalling "block" system was proposed by Cooke in 1842. Railway signal telegraphy did not change in essence from Cooke's initial concept for more than a century. In this system each line of railway was divided into sections or blocks of varying length. Entry to and exit from the block was to be authorised by electric telegraph and signalled by the line-side semaphore signals, so that only a single train could occupy the rails. In Cooke's original system, a single-needle telegraph was adapted to indicate just two messages: "Line Clear" and "Line Blocked". The signaller would adjust his line-side signals accordingly. As first implemented in 1844 each station had as many needles as there were stations on the line, giving a complete picture of the traffic. As lines expanded, a sequence of pairs of single-needle instruments were adopted, one pair for each block in each direction.[32]

Wigwag

[edit]Wigwag is a form of flag signalling using a single flag. Unlike most forms of flag signalling, which are used over relatively short distances, wigwag is designed to maximise the distance covered—up to 32 km (20 mi) in some cases. Wigwag achieved this by using a large flag—a single flag can be held with both hands unlike flag semaphore which has a flag in each hand—and using motions rather than positions as its symbols since motions are more easily seen. It was invented by US Army surgeon Albert J. Myer in the 1850s who later became the first head of the Signal Corps. Wigwag was used extensively during the American Civil War where it filled a gap left by the electrical telegraph. Although the electrical telegraph had been in use for more than a decade, the network did not yet reach everywhere and portable, ruggedized equipment suitable for military use was not immediately available. Permanent or semi-permanent stations were established during the war, some of them towers of enormous height and the system was extensive enough to be described as a communications network.[33][34]

Heliograph

[edit]

A heliograph is a telegraph that transmits messages by flashing sunlight with a mirror, usually using Morse code. The idea for a telegraph of this type was first proposed as a modification of surveying equipment (Gauss, 1821). Various uses of mirrors were made for communication in the following years, mostly for military purposes, but the first device to become widely used was a heliograph with a moveable mirror (Mance, 1869). The system was used by the French during the 1870–71 siege of Paris, with night-time signalling using kerosene lamps as the source of light. An improved version (Begbie, 1870) was used by British military in many colonial wars, including the Anglo-Zulu War (1879). At some point, a morse key was added to the apparatus to give the operator the same degree of control as in the electric telegraph.[35]

Another type of heliograph was the heliostat or heliotrope fitted with a Colomb shutter. The heliostat was essentially a surveying instrument with a fixed mirror and so could not transmit a code by itself. The term heliostat is sometimes used as a synonym for heliograph because of this origin. The Colomb shutter (Bolton and Colomb, 1862) was originally invented to enable the transmission of morse code by signal lamp between Royal Navy ships at sea.[35]

The heliograph was heavily used by Nelson A. Miles in Arizona and New Mexico after he took over command (1886) of the fight against Geronimo and other Apache bands in the Apache Wars. Miles had previously set up the first heliograph line in the US between Fort Keogh and Fort Custer in Montana. He used the heliograph to fill in vast, thinly populated areas that were not covered by the electric telegraph. Twenty-six stations covered an area 320 by 480 km (200 by 300 mi). In a test of the system, a message was relayed 640 km (400 mi) in four hours. Miles' enemies used smoke signals and flashes of sunlight from metal, but lacked a sophisticated telegraph code.[36] The heliograph was ideal for use in the American Southwest due to its clear air and mountainous terrain on which stations could be located. It was found necessary to lengthen the morse dash (which is much shorter in American Morse code than in the modern International Morse code) to aid differentiating from the morse dot.[35]

Use of the heliograph declined from 1915 onwards, but remained in service in Britain and British Commonwealth countries for some time. Australian forces used the heliograph as late as 1942 in the Western Desert Campaign of World War II. Some form of heliograph was used by the mujahideen in the Soviet–Afghan War (1979–1989).[35]

Teleprinter

[edit]

A teleprinter is a telegraph machine that can send messages from a typewriter-like keyboard and print incoming messages in readable text with no need for the operators to be trained in the telegraph code used on the line. It developed from various earlier printing telegraphs and resulted in improved transmission speeds.[37] The Morse telegraph (1837) was originally conceived as a system marking indentations on paper tape. A chemical telegraph making blue marks improved the speed of recording (Bain, 1846), but was delayed by a patent challenge from Morse. The first true printing telegraph (that is printing in plain text) used a spinning wheel of types in the manner of a daisy wheel printer (House, 1846, improved by Hughes, 1855). The system was adopted by Western Union.[38]

Early teleprinters used the Baudot code, a five-bit sequential binary code. This was a telegraph code developed for use on the French telegraph using a five-key keyboard (Baudot, 1874). Teleprinters generated the same code from a full alphanumeric keyboard. A feature of the Baudot code, and subsequent telegraph codes, was that, unlike Morse code, every character has a code of the same length making it more machine friendly.[39] The Baudot code was used on the earliest ticker tape machines (Calahan, 1867), a system for mass distributing information on current price of publicly listed companies.[40]

Automated punched-tape transmission

[edit]

In a punched-tape system, the message is first typed onto punched tape using the code of the telegraph system—Morse code for instance. It is then, either immediately or at some later time, run through a transmission machine which sends the message to the telegraph network. Multiple messages can be sequentially recorded on the same run of tape. The advantage of doing this is that messages can be sent at a steady, fast rate making maximum use of the available telegraph lines. The economic advantage of doing this is greatest on long, busy routes where the cost of the extra step of preparing the tape is outweighed by the cost of providing more telegraph lines. The first machine to use punched tape was Bain's teleprinter (Bain, 1843), but the system saw only limited use. Later versions of Bain's system achieved speeds up to 1000 words per minute, far faster than a human operator could achieve.[41]

The first widely used system (Wheatstone, 1858) was first put into service with the British General Post Office in 1867. A novel feature of the Wheatstone system was the use of bipolar encoding. That is, both positive and negative polarity voltages were used.[42] Bipolar encoding has several advantages, one of which is that it permits duplex communication.[43] The Wheatstone tape reader was capable of a speed of 400 words per minute.[44]: 190

Oceanic telegraph cables

[edit]

A worldwide communication network meant that telegraph cables would have to be laid across oceans. On land cables could be run uninsulated suspended from poles. Underwater, a good insulator that was both flexible and capable of resisting the ingress of seawater was required. A solution presented itself with gutta-percha, a natural rubber from the Palaquium gutta tree, after William Montgomerie sent samples to London from Singapore in 1843. The new material was tested by Michael Faraday and in 1845 Wheatstone suggested that it should be used on the cable planned between Dover and Calais by John Watkins Brett. The idea was proved viable when the South Eastern Railway company successfully tested a three-kilometre (two-mile) gutta-percha insulated cable with telegraph messages to a ship off the coast of Folkestone.[45] The cable to France was laid in 1850 but was almost immediately severed by a French fishing vessel.[46] It was relaid the next year[46] and connections to Ireland and the Low Countries soon followed.

Getting a cable across the Atlantic Ocean proved much more difficult. The Atlantic Telegraph Company, formed in London in 1856, had several failed attempts. A cable laid in 1858 worked poorly for a few days, sometimes taking all day to send a message despite the use of the highly sensitive mirror galvanometer developed by William Thomson (the future Lord Kelvin) before being destroyed by applying too high a voltage. Its failure and slow speed of transmission prompted Thomson and Oliver Heaviside to find better mathematical descriptions of long transmission lines.[47] The company finally succeeded in 1866 with an improved cable laid by SS Great Eastern, the largest ship of its day, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel.[48][47]

An overland telegraph from Britain to India was first connected in 1866 but was unreliable, prompting a submarine telegraph cable to be connected in 1870.[49] Several telegraph companies were combined to form the Eastern Telegraph Company in 1872. Australia was first linked to the rest of the world in October 1872 by a submarine telegraph cable at Darwin.[50]

From the 1850s until well into the 20th century, British submarine cable systems dominated the world system. This was set out as a formal strategic goal, which became known as the All Red Line.[51] In 1896, there were thirty cable-laying ships in the world and twenty-four of them were owned by British companies. In 1892, British companies owned and operated two-thirds of the world's cables and by 1923, their share was still 42.7 percent.[52] During World War I, Britain's telegraph communications were almost completely uninterrupted while it was able to quickly cut Germany's cables worldwide.[51]

Facsimile

[edit]

In 1843, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain invented a device that could be considered the first facsimile machine. He called his invention a "recording telegraph". Bain's telegraph was able to transmit images by electrical wires. Frederick Bakewell made several improvements on Bain's design and demonstrated a telefax machine. In 1855, an Italian priest, Giovanni Caselli, also created an electric telegraph that could transmit images. Caselli called his invention "Pantelegraph". Pantelegraph was successfully tested and approved for a telegraph line between Paris and Lyon.[53][54]

In 1881, English inventor Shelford Bidwell constructed the scanning phototelegraph that was the first telefax machine to scan any two-dimensional original, not requiring manual plotting or drawing. Around 1900, German physicist Arthur Korn invented the Bildtelegraph widespread in continental Europe especially since a widely noticed transmission of a wanted-person photograph from Paris to London in 1908 used until the wider distribution of the radiofax. Its main competitors were the Bélinographe by Édouard Belin first, then since the 1930s, the Hellschreiber, invented in 1929 by German inventor Rudolf Hell, a pioneer in mechanical image scanning and transmission.

Wireless telegraphy

[edit]

The late 1880s through to the 1890s saw the discovery and then development of a newly understood phenomenon into a form of wireless telegraphy, called Hertzian wave wireless telegraphy, radiotelegraphy, or (later) simply "radio". Between 1886 and 1888, Heinrich Rudolf Hertz published the results of his experiments where he was able to transmit electromagnetic waves (radio waves) through the air, proving James Clerk Maxwell's 1873 theory of electromagnetic radiation. Many scientists and inventors experimented with this new phenomenon but the consensus was that these new waves (similar to light) would be just as short range as light, and, therefore, useless for long range communication.[56]

At the end of 1894, the young Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi began working on the idea of building a commercial wireless telegraphy system based on the use of Hertzian waves (radio waves), a line of inquiry that he noted other inventors did not seem to be pursuing.[57] Building on the ideas of previous scientists and inventors Marconi re-engineered their apparatus by trial and error attempting to build a radio-based wireless telegraphic system that would function the same as wired telegraphy. He would work on the system through 1895 in his lab and then in field tests making improvements to extend its range. After many breakthroughs, including applying the wired telegraphy concept of grounding the transmitter and receiver, Marconi was able, by early 1896, to transmit radio far beyond the short ranges that had been predicted.[58] Having failed to interest the Italian government, the 22-year-old inventor brought his telegraphy system to Britain in 1896 and met William Preece, a Welshman, who was a major figure in the field and Chief Engineer of the General Post Office. A series of demonstrations for the British government followed—by March 1897, Marconi had transmitted Morse code signals over a distance of about 6 km (3+1⁄2 mi) across Salisbury Plain.

On 13 May 1897, Marconi, assisted by George Kemp, a Cardiff Post Office engineer, transmitted the first wireless signals over water to Lavernock (near Penarth in Wales) from Flat Holm.[59] His star rising, he was soon sending signals across the English Channel (1899), from shore to ship (1899) and finally across the Atlantic (1901).[60] A study of these demonstrations of radio, with scientists trying to work out how a phenomenon predicted to have a short range could transmit "over the horizon", led to the discovery of a radio reflecting layer in the Earth's atmosphere in 1902, later called the ionosphere.[61]

Radiotelegraphy proved effective for rescue work in sea disasters by enabling effective communication between ships and from ship to shore. In 1904, Marconi began the first commercial service to transmit nightly news summaries to subscribing ships, which could incorporate them into their on-board newspapers. A regular transatlantic radio-telegraph service was finally begun on 17 October 1907.[62][63] Notably, Marconi's apparatus was used to help rescue efforts after the sinking of RMS Titanic. Britain's postmaster-general summed up, referring to the Titanic disaster, "Those who have been saved, have been saved through one man, Mr. Marconi...and his marvellous invention."

Non-radio wireless telegraphy

[edit]The successful development of radiotelegraphy was preceded by a 50-year history of ingenious but ultimately unsuccessful experiments by inventors to achieve wireless telegraphy by other means.[citation needed]

Ground, water, and air conduction

[edit]Several wireless electrical signaling schemes based on the (sometimes erroneous) idea that electric currents could be conducted long-range through water, ground, and air were investigated for telegraphy before practical radio systems became available.

The original telegraph lines used two wires between the two stations to form a complete electrical circuit or "loop". In 1837, however, Carl August von Steinheil of Munich, Germany, found that by connecting one leg of the apparatus at each station to metal plates buried in the ground, he could eliminate one wire and use a single wire for telegraphic communication. This led to speculation that it might be possible to eliminate both wires and therefore transmit telegraph signals through the ground without any wires connecting the stations. Other attempts were made to send the electric current through bodies of water, to span rivers, for example. Prominent experimenters along these lines included Samuel F. B. Morse in the United States and James Bowman Lindsay in Great Britain, who in August 1854, was able to demonstrate transmission across a mill dam at a distance of 500 yards (457 metres).[64]

US inventors William Henry Ward (1871) and Mahlon Loomis (1872) developed electrical conduction systems based on the erroneous belief that there was an electrified atmospheric stratum accessible at low altitude.[65][66] They thought atmosphere current, connected with a return path using "Earth currents" would allow for wireless telegraphy as well as supply power for the telegraph, doing away with artificial batteries.[67][68] A more practical demonstration of wireless transmission via conduction came in Amos Dolbear's 1879 magneto electric telephone that used ground conduction to transmit over a distance of a quarter of a mile.[69]

In the 1890s inventor Nikola Tesla worked on an air and ground conduction wireless electric power transmission system, similar to Loomis',[70][71][72] which he planned to include wireless telegraphy. Tesla's experiments had led him to incorrectly conclude that he could use the entire globe of the Earth to conduct electrical energy[73][69] and his 1901 large scale application of his ideas, a high-voltage wireless power station, now called Wardenclyffe Tower, lost funding and was abandoned after a few years.

Telegraphic communication using earth conductivity was eventually found to be limited to impractically short distances, as was communication conducted through water, or between trenches during World War I.

Electrostatic and electromagnetic induction

[edit]

Both electrostatic and electromagnetic induction were used to develop wireless telegraph systems that saw limited commercial application. In the United States, Thomas Edison, in the mid-1880s, patented an electromagnetic induction system he called "grasshopper telegraphy", which allowed telegraphic signals to jump the short distance between a running train and telegraph wires running parallel to the tracks.[74] This system was successful technically but not economically, as there turned out to be little interest by train travelers in the use of an on-board telegraph service. During the Great Blizzard of 1888, this system was used to send and receive wireless messages from trains buried in snowdrifts. The disabled trains were able to maintain communications via their Edison induction wireless telegraph systems,[75] perhaps the first successful use of wireless telegraphy to send distress calls. Edison would also help to patent a ship-to-shore communication system based on electrostatic induction.[76]

The most successful creator of an electromagnetic induction telegraph system was William Preece, chief engineer of Post Office Telegraphs of the General Post Office (GPO) in the United Kingdom. Preece first noticed the effect in 1884 when overhead telegraph wires in Grays Inn Road were accidentally carrying messages sent on buried cables. Tests in Newcastle succeeded in sending a quarter of a mile using parallel rectangles of wire.[21]: 243 In tests across the Bristol Channel in 1892, Preece was able to telegraph across gaps of about 5 kilometres (3.1 miles). However, his induction system required extensive lengths of antenna wires, many kilometers long, at both the sending and receiving ends. The length of those sending and receiving wires needed to be about the same length as the width of the water or land to be spanned. For example, for Preece's station to span the English Channel from Dover, England, to the coast of France would require sending and receiving wires of about 30 miles (48 kilometres) along the two coasts. These facts made the system impractical on ships, boats, and ordinary islands, which are much smaller than Great Britain or Greenland. Also, the relatively short distances that a practical Preece system could span meant that it had few advantages over underwater telegraph cables.

Telegram services

[edit]

A telegram service is a company or public entity that delivers telegraphed messages directly to the recipient. Telegram services were not inaugurated until electric telegraphy became available. Earlier optical systems were largely limited to official government and military purposes.

Historically, telegrams were sent between a network of interconnected telegraph offices. A person visiting a local telegraph office paid by the word to have a message telegraphed to another office and delivered to the addressee on a paper form.[77]: 276 Messages (i.e. telegrams) sent by telegraph could be delivered by telegraph messenger faster than mail,[40] and even in the telephone age, the telegram remained popular for social and business correspondence. At their peak in 1929, an estimated 200 million telegrams were sent.[77]: 274

In 1919, the Central Bureau for Registered Addresses was established in the financial district of New York City. The bureau was created to ease the growing problem of messages being delivered to the wrong recipients. To combat this issue, the bureau offered telegraph customers the option to register unique code names for their telegraph addresses. Customers were charged $2.50 per year per code. By 1934, 28,000 codes had been registered.[78]

Telegram services still operate in much of the world (see worldwide use of telegrams by country), but e-mail and text messaging have rendered telegrams obsolete in many countries, and the number of telegrams sent annually has been declining rapidly since the 1980s.[79] Where telegram services still exist, the transmission method between offices is no longer by telegraph, but by telex or IP link.[80]

Telegram length

[edit]As telegrams have been traditionally charged by the word, messages were often abbreviated to pack information into the smallest possible number of words, in what came to be called "telegram style".

The average length of a telegram in the 1900s in the US was 11.93 words; more than half of the messages were 10 words or fewer.[81] According to another study, the mean length of the telegrams sent in the UK before 1950 was 14.6 words or 78.8 characters.[82] For German telegrams, the mean length is 11.5 words or 72.4 characters.[82] At the end of the 19th century, the average length of a German telegram was calculated as 14.2 words.[82]

Telex

[edit]

Telex (telegraph exchange) was a public switched network of teleprinters. It used rotary-telephone-style pulse dialling for automatic routing through the network. It initially used the Baudot code for messages. Telex development began in Germany in 1926, becoming an operational service in 1933 run by the Reichspost (the German imperial postal service). It had a speed of 50 baud—approximately 66 words per minute. Up to 25 telex channels could share a single long-distance telephone channel by using voice frequency telegraphy multiplexing, making telex the least expensive method of reliable long-distance communication.[83] Telex was introduced into Canada in July 1957, and the United States in 1958.[84] A new code, ASCII, was introduced in 1963 by the American Standards Association. ASCII was a seven-bit code and could thus support a larger number of characters than Baudot. In particular, ASCII supported upper and lower case whereas Baudot was upper case only.

Decline

[edit]Telegraph use began to permanently decline around 1920.[21]: 248 The decline began with the growth of the use of the telephone.[21]: 253 Ironically, the invention of the telephone grew out of the development of the harmonic telegraph, a device which was supposed to increase the efficiency of telegraph transmission and improve the profits of telegraph companies. Western Union gave up its patent battle with Alexander Graham Bell because it believed the telephone was not a threat to its telegraph business. The Bell Telephone Company was formed in 1877 and had 230 subscribers which grew to 30,000 by 1880. By 1886 there were a quarter of a million phones worldwide,[77]: 276–277 and nearly 2 million by 1900.[44]: 204 The decline was briefly postponed by the rise of special occasion congratulatory telegrams. Traffic continued to grow between 1867 and 1893 despite the introduction of the telephone in this period,[77]: 274 but by 1900 the telegraph was definitely in decline.[77]: 277

There was a brief resurgence in telegraphy during World War I but the decline continued as the world entered the Great Depression years of the 1930s.[77]: 277 After the Second World War new technology improved communication in the telegraph industry.[85] Telegraph lines continued to be an important means of distributing news feeds from news agencies by teleprinter machine until the rise of the internet in the 1990s. For Western Union, one service remained highly profitable—the wire transfer of money. This service kept Western Union in business long after the telegraph had ceased to be important.[77]: 277 In the modern era, the telegraph that began in 1837 has been gradually replaced by digital data transmission based on computer information systems.[85]

Social implications

[edit]Optical telegraph lines were installed by governments, often for a military purpose, and reserved for official use only. In many countries, this situation continued after the introduction of the electric telegraph. Starting in Germany and the UK, electric telegraph lines were installed by railway companies. Railway use quickly led to private telegraph companies in the UK and the US offering a telegraph service to the public using telegraph along railway lines. The availability of this new form of communication brought on widespread social and economic changes.

The electric telegraph freed communication from the time constraints of postal mail and revolutionized society and the global economy.[86][87] By the end of the 19th century, the telegraph was becoming an increasingly common medium of communication for ordinary people. The telegraph isolated the message (information) from the physical movement of objects or the process.[88]

There was some fear of the new technology. According to author Allan J. Kimmel, some people "feared that the telegraph would erode the quality of public discourse through the transmission of irrelevant, context-free information." Henry David Thoreau thought of the Transatlantic cable "...perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough." Kimmel says these fears anticipate many of the characteristics of the modern internet age.[89]

Initially, the telegraph was expensive, but it had an enormous effect on three industries: finance, newspapers, and railways. Telegraphy facilitated the growth of organizations "in the railroads, consolidated financial and commodity markets, and reduced information costs within and between firms".[87] In the US, there were 200 to 300 stock exchanges before the telegraph, but most of these were unnecessary and unprofitable once the telegraph made financial transactions at a distance easy and drove down transaction costs.[77]: 274–75 This immense growth in the business sectors influenced society to embrace the use of telegrams once the cost had fallen.

Worldwide telegraphy changed the gathering of information for news reporting. Journalists were using the telegraph for war reporting as early as 1846 when the Mexican–American War broke out. News agencies were formed, such as the Associated Press, for the purpose of reporting news by telegraph.[77]: 274–75 Messages and information would now travel far and wide, and the telegraph demanded a language "stripped of the local, the regional; and colloquial", to better facilitate a worldwide media language.[88] Media language had to be standardized, which led to the gradual disappearance of different forms of speech and styles of journalism and storytelling.

The spread of the railways created a need for an accurate standard time to replace local standards based on local noon. The means of achieving this synchronisation was the telegraph. This emphasis on precise time has led to major societal changes such as the concept of the time value of money.[77]: 273–74

During the telegraph era there was widespread employment of women in telegraphy. The shortage of men to work as telegraph operators in the American Civil War opened up the opportunity for women of a well-paid skilled job.[77]: 274 In the UK, there was widespread employment of women as telegraph operators even earlier – from the 1850s by all the major companies. The attraction of women for the telegraph companies was that they could pay them less than men. Nevertheless, the jobs were popular with women for the same reason as in the US; most other work available for women was very poorly paid.[39]: 77 [21]: 85

The economic impact of the telegraph was not much studied by economic historians until parallels started to be drawn with the rise of the internet. In fact, the electric telegraph was as important as the invention of printing in this respect. According to economist Ronnie J. Phillips, the reason for this may be that institutional economists paid more attention to advances that required greater capital investment. The investment required to build railways, for instance, is orders of magnitude greater than that for the telegraph.[77]: 269–70

In popular culture

[edit]The optical telegraph was quickly forgotten once it went out of service. While it was in operation, it was very familiar to the public across Europe. Examples appear in many paintings of the period. Poems include "Le Telégraphe" by Victor Hugo, and the collection Telegrafen: Optisk kalender för 1858 by Elias Sehlstedt[90] is dedicated to the telegraph. In novels, the telegraph is a major component in Lucien Leuwen by Stendhal, and it features in The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas.[11]: vii–ix Joseph Chudy's 1796 opera, Der Telegraph oder die Fernschreibmaschine, was written to publicise Chudy's telegraph (a binary code with five lamps) when it became clear that Chappe's design was being taken up.[11]: 42–43

Rudyard Kipling wrote a poem in praise of submarine telegraph cables; "And a new Word runs between: whispering, 'Let us be one!'"[91][92] Kipling's poem represented a widespread idea in the late nineteenth century that international telegraphy (and new technology in general)[93] would bring peace and mutual understanding to the world.[94] When a submarine telegraph cable first connected America and Britain, the New York Post declared:

It is the harbinger of an age when international difficulties will not have time to ripen into bloody results, and when, in spite of the fatuity and perveseness of rulers, war will be impossible.[95]

Newspaper names

[edit]Numerous newspapers and news outlets in various countries, such as The Daily Telegraph in Britain, The Telegraph in India, De Telegraaf in the Netherlands, and the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in the US, were given names which include the word "telegraph" due to their having received news by means of electric telegraphy. Some of these names are retained even though different means of news acquisition are now used.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "History and technology of Morse Code". EDinformatics.

- ^ Shectman, Jonathan (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 172. ISBN 9780313320156.

- ^ Samuel F. B. Morse, Examination of the Telegraphic Apparatus and the Processes in Telegraphy Archived 27 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 7–8, Philp & Solomons 1869 OCLC 769828711.

- ^ "Cablegram – Definition of cablegram by Merriam-Webster". merriam-webster.com. 27 July 2023.

- ^ "1,796 memos from US embassy in Manila in WikiLeaks 'Cablegate'". ABS–CBN Corporation. 29 November 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ Definition of "cable", The Macquarie Dictionary (3rd ed.). Australia: Macquarie Library. 1997. ISBN 978-0-949757-89-0.

(n.) 4. a telegram sent abroad, especially by submarine cable. (v.) 9. to send a message by submarine cable.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2007). The Great Wall of China 221 BC–AD 1644. Oxford: Osprey. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-84603-004-8.

- ^ Christopher H. Sterling, "Great Wall of China", pp. 197–198 in, Christopher H. Sterling (ed), Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century, ABC-CLIO, 2008 ISBN 1851097325.

- ^ Morris Rossabi, From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia, p. 203, Brill, 2014 ISBN 9004285296.

- ^ a b David L. Woods, "Ancient signals", pp. 24–25 in, Christopher H. Sterling (ed), Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century, ABC-CLIO, 2008 ISBN 1851097325.

- ^ a b c d e f Gerard J. Holzmann; Björn Pehrson, The Early History of Data Networks, IEEE Computer Society Press, 1995 ISBN 0818667826.

- ^ "The Origin of the Railway Semaphore". Mysite.du.edu. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Burns, Francis W. (2004). Communications: An International History of the Formative Years. IET. ISBN 978-0-86341-330-8.

- ^ "Semaphore | communications". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ How Napoleon's semaphore telegraph changed the world Archived 24 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, Hugh Schofield, 16 June 2013

- ^ "A Semaphore Telegraph Station", Scientific American Supplement, 20 April 1895, page 16087.

- ^ E. A. Marland, Early Electrical Communication, Abelard-Schuman Ltd, London 1964, no ISBN, Library of Congress 64-20875, pages 17–19;

- ^ Jones, R. Victor Samuel Thomas von Sömmering's "Space Multiplexed" Electrochemical Telegraph (1808–10) Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Harvard University website. Attributed to "Semaphore to Satellite", International Telecommunication Union, Geneva 1965.

- ^ Fahie, J. J. (1884), A History of Electric Telegraphy to the year 1837 (PDF), London: E. & F. N. Spon

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). "Sir Francis Ronalds and the Electric Telegraph". International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology. 86: 42–55. doi:10.1080/17581206.2015.1119481. S2CID 113256632.

- ^ a b c d e f Kieve, Jeffrey L. (1973). The Electric Telegraph: A Social and Economic History. David and Charles. OCLC 655205099.

- ^ Jay Clayton, "The voice in the machine", ch. 8 in, Jeffrey Masten, Peter Stallybrass, Nancy J. Vickers (eds), Language Machines: Technologies of Literary and Cultural Production, Routledge, 2016 ISBN 9781317721826.

- ^ "Milestones:Shilling's Pioneering Contribution to Practical Telegraphy, 1828–1837". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ^ R. W. Pohl, Einführung in die Physik, Vol. 3, Göttingen (Springer) 1924

- ^ a b Guarnieri, M. (2019). "Messaging Before the Internet—Early Electrical Telegraphs". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 13 (1): 38–41+53. doi:10.1109/MIE.2019.2893466. hdl:11577/3301045. S2CID 85499543.

- ^ a b c Anton A. Huurdeman, The Worldwide History of Telecommunications (2003) pp. 67–69

- ^ Roberts, Steven, Distant Writing

- ^ Watson, J.; Hill, A. (2015). Dictionary of Media and Communication Studies (9th ed.). London, UK: Bloomsbury – via Credo Reference.

- ^ "The First Transcontinental Telegraph System Was Completed October 24, 1861". America's Library. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ a b Lewis Coe, The Telegraph: A History of Morse's Invention and Its Predecessors in the United States, McFarland, p. 69, 2003 ISBN 0-78641808-7.

- ^ How the UK's railways shaped the development of the telegraph, British Telecom

- ^ Roberts, Steven, Distant Writing: 15. Railway Signal Telegraphy 1838 – 1868

- ^ Rebecca Raines, Getting the Message Through Archived 26 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine, US Government Printing Office, 1996 ISBN 0160872812.

- ^ Albert J. Myer, A Manual of Signals, D. Van Nostrand, 1866, OCLC 680380148.

- ^ a b c d David L. Woods, "Heliograph and mirrors", pp. 208–211 in, Christopher H. Sterling (ed), Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century, ABC-CLIO, 2008 ISBN 1851097325.

- ^ Nelson A. Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations of General Nelson A. Miles, vol. 2, pp. 481–484, University of Nebraska Press, 1992 ISBN 0803281811.

- ^ "Typewriter May Soon Be Transmitter of Telegrams" (PDF), The New York Times, 25 January 1914

- ^ "David Edward Hughes". Clarkson University. 14 April 2007. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008.

- ^ a b Beauchamp, K.G. (2001). History of Telegraphy: Its Technology and Application. IET. pp. 394–395. ISBN 978-0-85296-792-8.

- ^ a b Richard E. Smith, Elementary Information Security, p. 433, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2015 ISBN 1284055949.

- ^ Anton A. Huurdeman, The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, p. 72, Wiley, 2003 ISBN 0471205052.

- ^ Ken Beauchamp, History of Technology, p. 87, Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2001 ISBN 0852967926.

- ^ Lewis Coe, The Telegraph: A History of Morse's Invention and Its Predecessors in the United States, pp. 16–17, McFarland, 2003 ISBN 0786418087.

- ^ a b Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet, Berkley, 1999 ISBN 0-425-17169-8.

- ^ Haigh, K R (1968). Cable Ships and Submarine Cables. London: Adlard Coles Ltd. pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Solymar, Laszlo. The Effect of the Telegraph on Law and Order, War, Diplomacy, and Power Politics Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine in Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 204 f. 2000. Accessed 1 August 2014.

- ^ a b Guarnieri, M. (2014). "The Conquest of the Atlantic". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 8 (1): 53–56/67. doi:10.1109/MIE.2014.2299492. S2CID 41662509.

- ^ Wilson, Arthur (1994). The Living Rock: The Story of Metals Since Earliest Times and Their Impact on Civilization. p. 203. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85573-301-5.

- ^ G.C. Mendis (1952). Ceylon Under the British. Asian Educational Services. p. 96. ISBN 978-81-206-1930-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Briggs, Asa and Burke, Peter: "A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet", p110. Polity, Cambridge, 2005.

- ^ a b Kennedy, P. M. (October 1971). "Imperial Cable Communications and Strategy, 1870–1914". The English Historical Review. 86 (341): 728–752. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxvi.cccxli.728. JSTOR 563928.

- ^ Headrick, D.R., & Griset, P. (2001). Submarine telegraph cables: business and politics, 1838–1939. The Business History Review, 75(3), 543–578.

- ^ "CASELLI". www.itisgalileiroma.it. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ "The Institute of Chemistry - The Hebrew University of Jerusalem". huji.ac.il. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008.

- ^ "First Atlantic Ocean crossing by a wireless signal" Archived 26 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine. aerohistory.org. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ view was held by Nikola Tesla, Oliver Lodge, Alexander Stepanovich Popov, amongst others (also Brian Regal, Radio: The Life Story of a Technology, page 22)

- ^ John W. Klooster (2009). Icons of Invention: The Makers of the Modern World from Gutenberg to Gates. ABC-CLIO. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-313-34743-6.

- ^ Sungook Hong. Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion. MIT Press - 2001, page 21.

- ^ "Marconi: Radio Pioneer". BBC South East Wales. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ^ "Letters to the Editor: Marconi and the History of Radio". IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine. 46 (2): 130. 2004. doi:10.1109/MAP.2004.1305565.

- ^ Victor L. Granatstein (2012). Physical Principles of Wireless Communications, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4398-7897-2.

- ^ "The Clifden Station of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph System". Scientific American. 23 November 1907.

- ^ Second Test of the Marconi Over-Ocean Wireless System Proved Entirely Successful Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Sydney Daily Post. 24 October 1907.

- ^ Fahie, J. J., A History of Wireless Telegraphy, 1838–1899, 1899, p. 29.

- ^ Christopher Cooper, The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation, Race Point Publishing, 2015, pp. 154, 165

- ^ Theodore S. Rappaport, Brian D. Woerner, Jeffrey H. Reed, Wireless Personal Communications: Trends and Challenges, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, pp. 211–215

- ^ Christopher Cooper, The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation, Race Point Publishing, 2015, p. 154

- ^ Thomas H. White, section 21, MAHLON LOOMIS

- ^ a b Christopher Cooper, The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation, Race Point Publishing, 2015, p. 165 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute – Volume 78 – p. 87

- ^ W. Bernard Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, Princeton University Press – 2013, p. H-45

- ^ Marc J. Seifer, Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla: Biography of a Genius, Citadel Press – 1996, p. 107

- ^ Carlson, W. Bernard (2013). Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton University Press. p. 301. ISBN 1400846552

- ^ (U.S. patent 465,971, Means for Transmitting Signals Electrically, US 465971 A, 1891

- ^ "Defied the storm's worst-communication always kept up by 'train telegraphy,'" New York Times, March 17, 1888, p. 8. Proquest Historical Newspapers (subscription). Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ^ Christopher H. Sterling, Encyclopedia of Radio 3-Volume Set, Routledge – 2004, p. 833

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ronnie J. Phillips, "Digital technology and institutional change from the gilded age to modern times: The impact of the telegraph and the internet" Archived 8 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 34, iss. 2, pp. 267–89, June 2000.

- ^ James, Gleick (2011), The information : a history, a theory, a flood, Books on Tape, ISBN 978-0-307-91498-9, OCLC 689998325, retrieved 12 April 2021

- ^ Tom Standage, The Victorian Internet, Afterword, Walker & Co, 2007 ISBN 978-0-802-71879-2.

- ^ "TELEGRAM NOT DEAD. STOP". Ars Technica. 19 June 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Hochfelder, David (2012). The Telegraph in America, 1832–1920. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-42140747-0.

- ^ a b c Frehner, Carmen (2008). Email, SMS, MMS: The Linguistic Creativity of Asynchronous Discourse in the New Media Age. Bern: Peter Lang AG. pp. 187, 191. ISBN 978-303911451-1.

- ^ "Telegraphy and Telex". siemens.com Global Website. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Phillip R. Easterlin, "Telex in New York", Western Union Technical Review, April 1959: 45

- ^ a b "The End of The Telegraph Era". Britannica. 22 July 2024.

- ^ Downey, Gregory J. (2002) Telegraph Messenger Boys: Labor, Technology, and Geography, 1850–1950, Routledge, New York and London, p. 7

- ^ a b Economic History Encyclopedia (2010) "History of the U.S. Telegraph Industry", "EH.Net Encyclopedia: History of the U.S. Telegraph Industry". Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 14 December 2005.

- ^ a b Carey, James (1989). Communication as Culture, Routledge, New York and London, p. 210

- ^ Allan J. Kimmel, People and Products: Consumer Behavior and Product Design, pp. 53–54, Routledge, 2015 ISBN 1317607503.

- ^ Sehlstedt, Elias, Telegrafen: Optisk Kalender för 1858 ([1]), Tryckt Hos Joh Beckman, 1857. ISBN 9171201823.

- ^ Kipling, Rudyard. "The Seven Seas". Retrieved 8 August 2022 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Jonathan Reed Winkler, Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I, p. 1, Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 0674033906.

- ^ Armand Mattelart, Networking the World, 1794–2000, p. 19. University of Minnesota Press, 2000. ISBN 0816632871.

- ^ John A. Britton, Cables, Crises, and the Press: The Geopolitics of the New Information System in the Americas, 1866–1903, p. xi, University of New Mexico Press, 2013. ISBN 0826353983.

- ^ Lindley, David (2004). Degrees Kelvin: a tale of genius, invention, and tragedy. Joseph Henry Press. p. 138. ISBN 0309167825.

Further reading

[edit]- Britton, John A. Cables, Crises, and the Press: The Geopolitics of the New International Information System in the Americas, 1866–1903. (University of New Mexico Press, 2013).

- Fari, Simone. Formative Years of the Telegraph Union (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015).

- Fari, Simone. Victorian Telegraphy Before Nationalization (2014).

- Gorman, Mel. "Sir William O'Shaughnessy, Lord Dalhousie, and the establishment of the telegraph system in India." Technology and Culture 12.4 (1971): 581–601 online Archived 21 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hindmarch-Watson, Katie. "Embodying Telegraphy in Late Victorian London." Information & Culture 55, no. 1 (2020): 10-29.

- Hochfelder, David, The Telegraph in America, 1832–1920 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

- Huurdeman, Anton A. The Worldwide History of Telecommunications (John Wiley & Sons, 2003)

- John, Richard R. Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (Harvard University Press; 2010) 520 pages; the evolution of American telegraph and telephone networks.

- Kieve, Jeffrey L. (1973). The Electric Telegraph: a Social and Economic History. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5883-9.

- Lew, B., and Cater, B. "The Telegraph, Co-ordination of Tramp Shipping, and Growth in World Trade, 1870–1910", European Review of Economic History 10 (2006): 147–73.

- Müller, Simone M., and Heidi JS Tworek. "'The telegraph and the bank': on the interdependence of global communications and capitalism, 1866–1914." Journal of Global History 10#2 (2015): 259–283.

- O'Hara, Glen. "New Histories of British Imperial Communication and the 'Networked World' of the 19th and Early 20th Centuries" History Compass (2010) 8#7pp 609–625, Historiography,

- Richardson, Alan J. "The cost of a telegram: Accounting and the evolution of international regulation of the telegraph." Accounting History 20#4 (2015): 405–429.

- Standage, Tom (1998). The Victorian Internet. Berkley Trade. ISBN 0-425-17169-8.

- Thompson, Robert Luther. Wiring a continent: The history of the telegraph industry in the United States, 1832–1866 (Princeton UP, 1947).

- Wenzlhuemer, Roland. "The Development of Telegraphy, 1870–1900: A European Perspective on a World History Challenge." History Compass 5#5 (2007): 1720–1742.

- Wenzlhuemer, Roland. Connecting the nineteenth-century world: The telegraph and globalization (Cambridge UP, 2013). online review

- Winseck, Dwayne R., and Robert M. Pike. Communication & Empire: Media, Markets & Globalization, 1860–1930 (2007), 429pp.

- The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century's On-Line Pioneers, a book about the telegraph

Technology

[edit]- Armagnay, Henri (1908). "Phototelegraphy". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 197–207. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Dargan, J. "The Railway Telegraph", Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, March 1985 pp. 49–71

- Gray, Thomas (1892). "The Inventors Of The Telegraph And Telephone". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 639–659. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Pichler, Franz, Magneto-Electric Dial Telegraphs: Contributions of Wheatstone, Stoehrer and Siemens, The AWA Review vol. 26, (2013).

- Ross, Nelson E. HOW TO WRITE TELEGRAMS PROPERLY Archived 31 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph Office (1928)

- Wheen, Andrew;— DOT-DASH TO DOT.COM: How Modern Telecommunications Evolved from the Telegraph to the Internet (Springer, 2011) ISBN 978-1-4419-6759-6.

- Wilson, Geoffrey, The Old Telegraphs, Phillimore & Co Ltd 1976 ISBN 0-900592-79-6; a comprehensive history of the shutter, semaphore and other kinds of visual mechanical telegraphs.

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Telegraph at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- The Porthcurno Telegraph Museum (Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine)—The biggest telegraph station in the world, now a museum

- Distant Writing—The History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868

- Western Union Telegraph Company Records, 1820–1995—Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- Early telegraphy and fax engineering, still operable in a German computer museum (Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Telegram Falls Silent Stop Era Ends Stop", The New York Times, 6 February 2006

- International Facilities of the American Carriers—an overview of the U.S. international cable network in 1950

- Elizabeth Bruton: "Communication Technology", in the 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War