Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Earth science

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

Earth science or geoscience includes all fields of natural science related to the planet Earth.[1] This is a branch of science dealing with the physical, chemical, and biological complex constitutions and synergistic linkages of Earth's four spheres: the biosphere, hydrosphere/cryosphere, atmosphere, and geosphere (or lithosphere). Earth science can be considered to be a branch of planetary science but with a much older history.

Geology

[edit]

Geology is broadly the study of Earth's structure, substance, and processes. Geology is largely the study of the lithosphere, or Earth's surface, including the crust and rocks. It includes the physical characteristics and processes that occur in the lithosphere as well as how they are affected by geothermal energy. It incorporates aspects of chemistry, physics, and biology as elements of geology interact. Historical geology is the application of geology to interpret Earth history and how it has changed over time.

Geochemistry studies the chemical components and processes of the Earth. Geophysics studies the physical properties of the Earth. Paleontology studies fossilized biological material in the lithosphere. Planetary geology studies geoscience as it pertains to extraterrestrial bodies. Geomorphology studies the origin of landscapes. Structural geology studies the deformation of rocks to produce mountains and lowlands. Resource geology studies how energy resources can be obtained from minerals. Environmental geology studies how pollution and contaminants affect soil and rock.[2] Mineralogy is the study of minerals and includes the study of mineral formation, crystal structure, hazards associated with minerals, and the physical and chemical properties of minerals.[3] Petrology is the study of rocks, including the formation and composition of rocks. Petrography is a branch of petrology that studies the typology and classification of rocks.[4]

Earth's interior

[edit]

Plate tectonics, mountain ranges, volcanoes, and earthquakes are geological phenomena that can be explained in terms of physical and chemical processes in the Earth's crust.[6] Beneath the Earth's crust lies the mantle which is heated by the radioactive decay of heavy elements. The mantle is not quite solid and consists of magma which is in a state of semi-perpetual convection. This convection process causes the lithospheric plates to move, albeit slowly. The resulting process is known as plate tectonics.[7][8][9][10] Areas of the crust where new crust is created are called divergent boundaries, those where it is brought back into the Earth are convergent boundaries and those where plates slide past each other, but no new lithospheric material is created or destroyed, are referred to as transform (or conservative) boundaries.[8][10][11] Earthquakes result from the movement of the lithospheric plates, and they often occur near convergent boundaries where parts of the crust are forced into the earth as part of subduction.[12]

Plate tectonics might be thought of as the process by which the Earth is resurfaced. As the result of seafloor spreading, new crust and lithosphere is created by the flow of magma from the mantle to the near surface, through fissures, where it cools and solidifies. Through subduction, oceanic crust and lithosphere vehemently returns to the convecting mantle.[8][10][13] Volcanoes result primarily from the melting of subducted crust material. Crust material that is forced into the asthenosphere melts, and some portion of the melted material becomes light enough to rise to the surface—giving birth to volcanoes.[8][12]

Atmospheric science

[edit]

(image not to scale.)

Atmospheric science initially developed in the late-19th century as a means to forecast the weather through meteorology, the study of weather. Atmospheric chemistry was developed in the 20th century to measure air pollution and expanded in the 1970s in response to acid rain. Climatology studies the climate and climate change.[14]

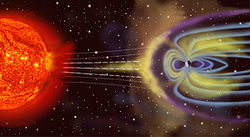

The troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere are the five layers which make up Earth's atmosphere. 75% of the mass in the atmosphere is located within the troposphere, the lowest layer. In all, the atmosphere is made up of about 78.0% nitrogen, 20.9% oxygen, and 0.92% argon, and small amounts of other gases including CO2 and water vapor.[15] Water vapor and CO2 cause the Earth's atmosphere to catch and hold the Sun's energy through the greenhouse effect.[16] This makes Earth's surface warm enough for liquid water and life. In addition to trapping heat, the atmosphere also protects living organisms by shielding the Earth's surface from cosmic rays.[17] The magnetic field—created by the internal motions of the core—produces the magnetosphere which protects Earth's atmosphere from the solar wind.[18] As the Earth is 4.5 billion years old,[19][20] it would have lost its atmosphere by now if there were no protective magnetosphere.

Earth's magnetic field

[edit]

| Part of a series of |

| Geophysics |

|---|

|

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic field is generated by electric currents due to the motion of convection currents of a mixture of molten iron and nickel in Earth's outer core: these convection currents are caused by heat escaping from the core, a natural process called a geodynamo.

The magnitude of Earth's magnetic field at its surface ranges from 25 to 65 μT (0.25 to 0.65 G).[23] As an approximation, it is represented by a field of a magnetic dipole currently tilted at an angle of about 11° with respect to Earth's rotational axis, as if there were an enormous bar magnet placed at that angle through the center of Earth. The North geomagnetic pole (Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada) actually represents the South pole of Earth's magnetic field, and conversely the South geomagnetic pole corresponds to the north pole of Earth's magnetic field (because opposite magnetic poles attract and the north end of a magnet, like a compass needle, points toward Earth's South magnetic field.)

While the North and South magnetic poles are usually located near the geographic poles, they slowly and continuously move over geological time scales, but sufficiently slowly for ordinary compasses to remain useful for navigation. However, at irregular intervals averaging several hundred thousand years, Earth's field reverses and the North and South Magnetic Poles abruptly switch places. These reversals of the geomagnetic poles leave a record in rocks that are of value to paleomagnetists in calculating geomagnetic fields in the past. Such information in turn is helpful in studying the motions of continents and ocean floors. The magnetosphere is defined by the extent of Earth's magnetic field in space or geospace. It extends above the ionosphere, several tens of thousands of kilometres into space, protecting Earth from the charged particles of the solar wind and cosmic rays that would otherwise strip away the upper atmosphere, including the ozone layer that protects Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation.Hydrology

[edit]

Hydrology is the study of the hydrosphere and the movement of water on Earth. It emphasizes the study of how humans use and interact with freshwater supplies. Study of water's movement is closely related to geomorphology and other branches of Earth science. Applied hydrology involves engineering to maintain aquatic environments and distribute water supplies. Subdisciplines of hydrology include oceanography, hydrogeology, ecohydrology, and glaciology. Oceanography is the study of oceans.[24] Hydrogeology is the study of groundwater. It includes the mapping of groundwater supplies and the analysis of groundwater contaminants. Applied hydrogeology seeks to prevent contamination of groundwater and mineral springs and make it available as drinking water. The earliest exploitation of groundwater resources dates back to 3000 BC, and hydrogeology as a science was developed by hydrologists beginning in the 17th century.[25] Ecohydrology is the study of ecological systems in the hydrosphere. It can be divided into the physical study of aquatic ecosystems and the biological study of aquatic organisms. Ecohydrology includes the effects that organisms and aquatic ecosystems have on one another as well as how these ecosystems are affected by humans.[26] Glaciology is the study of the cryosphere, including glaciers and coverage of the Earth by ice and snow. Concerns of glaciology include access to glacial freshwater, mitigation of glacial hazards, obtaining resources that exist beneath frozen land, and addressing the effects of climate change on the cryosphere.[27]

Ecology

[edit]Ecology is the study of the biosphere. This includes the study of nature and of how living things interact with the Earth and one another and the consequences of that. It considers how living things use resources such as oxygen, water, and nutrients from the Earth to sustain themselves. It also considers how humans and other living creatures cause changes to nature.[28]

Physical geography

[edit]Physical geography is the study of Earth's systems and how they interact with one another as part of a single self-contained system. It incorporates astronomy, mathematical geography, meteorology, climatology, geology, geomorphology, biology, biogeography, pedology, and soils geography. Physical geography is distinct from human geography, which studies the human populations on Earth, though it does include human effects on the environment.[29]

Methodology

[edit]Methodologies vary depending on the nature of the subjects being studied. Studies typically fall into one of three categories: observational, experimental, or theoretical. Earth scientists often conduct sophisticated computer analysis or visit an interesting location to study earth phenomena (e.g. Antarctica or hot spot island chains).

A foundational idea in Earth science is the notion of uniformitarianism, which states that "ancient geologic features are interpreted by understanding active processes that are readily observed." In other words, any geologic processes at work in the present have operated in the same ways throughout geologic time. This enables those who study Earth history to apply knowledge of how the Earth's processes operate in the present to gain insight into how the planet has evolved and changed throughout long history.

Earth's spheres

[edit]−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Earth science, it is common to conceptualize the Earth's surface as consisting of several distinct layers, often referred to as spheres: the lithosphere, the hydrosphere, the atmosphere, and the biosphere, this concept of spheres is a useful tool for understanding the Earth's surface and its various processes[30] these correspond to rocks, water, air and life. Also included by some are the cryosphere (corresponding to ice) as a distinct portion of the hydrosphere and the pedosphere (corresponding to soil) as an active and intermixed sphere. The following fields of science are generally categorized within the Earth sciences:

- Geology describes the rocky parts of the Earth's crust (or lithosphere) and its historic development. Major subdisciplines are mineralogy and petrology, geomorphology, paleontology, stratigraphy, structural geology, engineering geology, and sedimentology.[31][32]

- Physical geography focuses on geography as an Earth science. Physical geography is the study of Earth's seasons, climate, atmosphere, soil, streams, landforms, and oceans. Physical geography can be divided into several branches or related fields, as follows: geomorphology, biogeography, environmental geography, palaeogeography, climatology, meteorology, coastal geography, hydrology, ecology, glaciology.[citation needed]

- Geophysics and geodesy investigate the shape of the Earth, its reaction to forces and its magnetic and gravity fields. Geophysicists explore the Earth's core and mantle as well as the tectonic and seismic activity of the lithosphere.[32][33][34] Geophysics is commonly used to supplement the work of geologists in developing a comprehensive understanding of crustal geology, particularly in mineral and petroleum exploration. Seismologists use geophysics to understand plate tectonic movement, as well as predict seismic activity.

- Geochemistry studies the processes that control the abundance, composition, and distribution of chemical compounds and isotopes in geologic environments. Geochemists use the tools and principles of chemistry to study the Earth's composition, structure, processes, and other physical aspects. Major subdisciplines are aqueous geochemistry, cosmochemistry, isotope geochemistry and biogeochemistry.

- Soil science covers the outermost layer of the Earth's crust that is subject to soil formation processes (or pedosphere).[35] Major subdivisions in this field of study include edaphology and pedology.[36]

- Ecology covers the interactions between organisms and their environment. This field of study differentiates the study of Earth from other planets in the Solar System, Earth being the only planet teeming with life.

- Hydrology, oceanography and limnology are studies which focus on the movement, distribution, and quality of the water and involve all the components of the hydrologic cycle on the Earth and its atmosphere (or hydrosphere). "Sub-disciplines of hydrology include hydrometeorology, surface water hydrology, hydrogeology, watershed science, forest hydrology, and water chemistry."[37]

- Glaciology covers the icy parts of the Earth (or cryosphere).

- Atmospheric sciences cover the gaseous parts of the Earth (or atmosphere) between the surface and the exosphere (about 1000 km). Major subdisciplines include meteorology, climatology, atmospheric chemistry, and atmospheric physics.

Earth science breakup

[edit]- Hydrology

- Limnology (freshwater science)

- Oceanography (marine science)

- Chemical oceanography

- Physical oceanography

- Biological oceanography (marine biology)

- Geological oceanography (marine geology)

- Geology

- Geography

- Geochemistry

- Geomorphology

- Geophysics

- Geochronology

- Geodynamics (see also Tectonics)

- Geomagnetism

- Gravimetry (also part of Geodesy)

- Seismology

- Glaciology

- Hydrogeology

- Mineralogy

- Petrology

- Speleology

- Volcanology

- Systems

- Earth system science

- Environmental science

- Geography

- Gaia hypothesis

- Systems ecology

- Systems geology

- Others

See also

[edit]- American Geosciences Institute

- Earth sciences graphics software

- Four traditions of geography

- Glossary of geology terms

- List of Earth scientists

- List of geoscience organizations

- List of unsolved problems in geoscience

- Making North America

- National Association of Geoscience Teachers

- Solid-earth science

- Science tourism

- Structure of the Earth

References

[edit]- ^ "Earth sciences | Definition, Topics, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Smith & Pun 2006, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Haldar 2020, p. 109.

- ^ Haldar 2020, p. 145.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. London: Academic Press. 2000. ISBN 9780080547985.

- ^ "Earth's Energy Budget". ou.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-08-27. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ^ Simison 2007, paragraph 7

- ^ a b c d Adams & Lambert 2006, pp. 94–95, 100, 102

- ^ Smith & Pun 2006, pp. 13–17, 218, G-6

- ^ a b c Oldroyd 2006, pp. 101, 103, 104

- ^ Smith & Pun 2006, p. 331

- ^ a b Smith & Pun 2006, pp. 325–26, 329

- ^ Smith & Pun 2006, p. 327

- ^ Wallace, John M.; Hobbs, Peter V. (2006). Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey (2nd ed.). Elsevier Science. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9780080499536.

- ^ Adams & Lambert 2006, pp. 107–08

- ^ American Heritage, p. 770

- ^ Parker, Eugene (March 2006), Shielding Space (PDF), Scientific American, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-01, retrieved 2017-05-24

- ^ Adams & Lambert 2006, pp. 21–22

- ^ Smith & Pun 2006, p. 183

- ^ "How Did Scientists Calculate the Age of Earth?". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Glatzmaier, Gary A.; Roberts, Paul H. (1995). "A three-dimensional self-consistent computer simulation of a geomagnetic field reversal". Nature. 377 (6546): 203–209. Bibcode:1995Natur.377..203G. doi:10.1038/377203a0. S2CID 4265765.

- ^ Glatzmaier, Gary. "The Geodynamo". University of California Santa Cruz. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Finlay, C. C.; Maus, S.; Beggan, C. D.; Bondar, T. N.; Chambodut, A.; Chernova, T. A.; Chulliat, A.; Golovkov, V. P.; Hamilton, B.; Hamoudi, M.; Holme, R.; Hulot, G.; Kuang, W.; Langlais, B.; Lesur, V.; Lowes, F. J.; Lühr, H.; Macmillan, S.; Mandea, M.; McLean, S.; Manoj, C.; Menvielle, M.; Michaelis, I.; Olsen, N.; Rauberg, J.; Rother, M.; Sabaka, T. J.; Tangborn, A.; Tøffner-Clausen, L.; Thébault, E.; Thomson, A. W. P.; Wardinski, I.; Wei, Z.; Zvereva, T. I. (December 2010). "International Geomagnetic Reference Field: the eleventh generation". Geophysical Journal International. 183 (3): 1216–1230. Bibcode:2010GeoJI.183.1216F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04804.x. hdl:20.500.11850/27303.

- ^ Davie, Tim; Quinn, Nevil Wyndham (2019). Fundamentals of Hydrology (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780203798942.

- ^ Hölting, Bernward; Coldewey, Wilhelm G. (2019). "Introduction". Hydrogeology (8th ed.). Springer. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-56375-5. ISBN 9783662563755. Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- ^ Wood, Paul J.; Hannah, David M.; Sadler, Jonathan P. (2007). "Ecohydrology and Hydroecology: An Introduction". Hydroecology and Ecohydrology: Past, Present and Future. Wiley. pp. 1–6. ISBN 9780470010174.

- ^ Knight, Peter (1999). Glaciers. Taylor & Francis. p. 1. ISBN 9780748740000.

- ^ Ricklefs, Robert E.; Miller, Gary L. (2000). Ecology (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780716728290.

- ^ Petersen, James F.; Sack, Dorothy; Gabler, Robert E. (2014). Fundamentals of Physical Geography. Cengage Learning. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9781285969718.

- ^ Earth's Spheres Archived August 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. ©1997–2000. Wheeling Jesuit University/NASA Classroom of the Future. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ^ Adams & Lambert 2006, p. 20

- ^ a b Smith & Pun 2006, p. 5

- ^ "WordNet Search – 3.1". princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ "NOAA National Ocean Service Education: Global Positioning Tutorial". noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2005-05-08. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ Elissa Levine, 2001, The Pedosphere As A Hub broken link?

- ^ Gardiner, Duane T. "Lecture 1 Chapter 1 Why Study Soils?". ENV320: Soil Science Lecture Notes. Texas A&M University-Kingsville. Archived from the original on 2018-02-09. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- ^ Craig, Kendall. "Hydrology of the Watershed". Archived from the original on 2017-01-11. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

Sources

[edit]- Adams, Simon; Lambert, David (2006). Earth Science: An illustrated guide to science. New York: Chelsea House. ISBN 978-0-8160-6164-8.

- Haldar, S. K. (2020). Introduction to Mineralogy and Petrology (2nd ed.). Elsevier Science. ISBN 9780323851367.

- American Heritage dictionary of the English language (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1992. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

- Simison, W. Brian (2007-02-05). "The mechanism behind plate tectonics". Archived from the original on 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- Smith, Gary A.; Pun, Aurora (2006). How Does the Earth Work? Physical Geology and the Process of Science. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-034129-7.

- Oldroyd, David (2006). Earth Cycles: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33229-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Allaby M., 2008. Dictionary of Earth Sciences, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-921194-4

- Korvin G., 1998. Fractal Models in the Earth Sciences, Elsvier, ISBN 978-0-444-88907-2

- "Earth's Energy Budget". Oklahoma Climatological Survey. 1996–2004. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- Miller, George A.; Christiane Fellbaum; and Randee Tengi; and Pamela Wakefield; and Rajesh Poddar; and Helen Langone; Benjamin Haskell (2006). "WordNet Search 3.0". WordNet a lexical database for the English language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University/Cognitive Science Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- "NOAA National Ocean Service Education: Geodesy". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2005-03-08. Archived from the original on 2005-05-08. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- Reed, Christina (2008). Earth Science: Decade by Decade. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-5533-3.

- Tarbuck E. J., Lutgens F. K., and Tasa D., 2002. Earth Science, Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-13-035390-0

External links

[edit]- Earth Science Picture of the Day, a service of Universities Space Research Association, sponsored by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

- Geoethics in Planetary and Space Exploration.

- Geology Buzz: Earth Science Archived 2021-11-04 at the Wayback Machine