Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Derivative

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

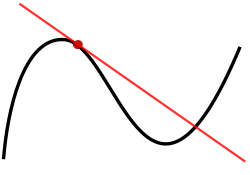

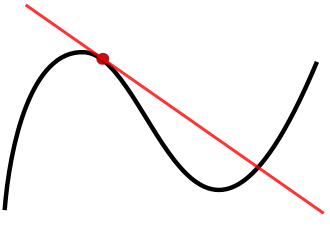

In mathematics, the derivative is a fundamental tool that quantifies the sensitivity to change of a function's output with respect to its input. The derivative of a function of a single variable at a chosen input value, when it exists, is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function at that point. The tangent line is the best linear approximation of the function near that input value. The derivative is often described as the instantaneous rate of change, the ratio of the instantaneous change in the dependent variable to that of the independent variable.[1] The process of finding a derivative is called differentiation.

There are multiple different notations for differentiation. Leibniz notation, named after Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, is represented as the ratio of two differentials, whereas prime notation is written by adding a prime mark. Higher order notations represent repeated differentiation, and they are usually denoted in Leibniz notation by adding superscripts to the differentials, and in prime notation by adding additional prime marks. Higher order derivatives are used in physics; for example, the first derivative with respect to time of the position of a moving object is its velocity, and the second derivative is its acceleration.

Derivatives can be generalized to functions of several real variables. In this case, the derivative is reinterpreted as a linear transformation whose graph is (after an appropriate translation) the best linear approximation to the graph of the original function. The Jacobian matrix is the matrix that represents this linear transformation with respect to the basis given by the choice of independent and dependent variables. It can be calculated in terms of the partial derivatives with respect to the independent variables. For a real-valued function of several variables, the Jacobian matrix reduces to the gradient vector.

Definition

[edit]As a limit

[edit]A function of a real variable is differentiable at a point of its domain, if its domain contains an open interval containing , and the limit exists.[2] This means that, for every positive real number , there exists a positive real number such that, for every such that and then is defined, and where the vertical bars denote the absolute value. This is an example of the (ε, δ)-definition of limit.[3]

If the function is differentiable at , that is if the limit exists, then this limit is called the derivative of at . Multiple notations for the derivative exist.[4] The derivative of at can be denoted , read as " prime of "; or it can be denoted , read as "the derivative of with respect to at " or " by (or over) at ". See § Notation below. If is a function that has a derivative at every point in its domain, then a function can be defined by mapping every point to the value of the derivative of at . This function is written and is called the derivative function or the derivative of . The function sometimes has a derivative at most, but not all, points of its domain. The function whose value at equals whenever is defined and elsewhere is undefined is also called the derivative of . It is still a function, but its domain may be smaller than the domain of .[5]

For example, let be the squaring function: . Then the quotient in the definition of the derivative is[6] The division in the last step is valid as long as . The closer is to , the closer this expression becomes to the value . The limit exists, and for every input the limit is . So, the derivative of the squaring function is the doubling function: .

The ratio in the definition of the derivative is the slope of the line through two points on the graph of the function , specifically the points and . As is made smaller, these points grow closer together, and the slope of this line approaches the limiting value, the slope of the tangent to the graph of at . In other words, the derivative is the slope of the tangent.[7]

Using infinitesimals

[edit]One way to think of the derivative is as the ratio of an infinitesimal change in the output of the function to an infinitesimal change in its input.[8] In order to make this intuition rigorous, a system of rules for manipulating infinitesimal quantities is required.[9] The system of hyperreal numbers is a way of treating infinite and infinitesimal quantities. The hyperreals are an extension of the real numbers that contain numbers greater than anything of the form for any finite number of terms. Such numbers are infinite, and their reciprocals are infinitesimals. The application of hyperreal numbers to the foundations of calculus is called nonstandard analysis. This provides a way to define the basic concepts of calculus such as the derivative and integral in terms of infinitesimals, thereby giving a precise meaning to the in the Leibniz notation. Thus, the derivative of becomes for an arbitrary infinitesimal , where denotes the standard part function, which "rounds off" each finite hyperreal to the nearest real.[10] Taking the squaring function as an example again,

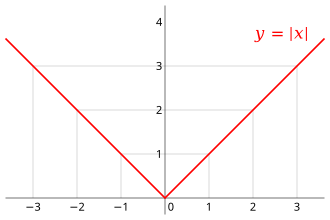

Continuity and differentiability

[edit]If is differentiable at , then must also be continuous at .[11] As an example, choose a point and let be the step function that returns the value 1 for all less than , and returns a different value 10 for all greater than or equal to . The function cannot have a derivative at . If is negative, then is on the low part of the step, so the secant line from to is very steep; as tends to zero, the slope tends to infinity. If is positive, then is on the high part of the step, so the secant line from to has slope zero. Consequently, the secant lines do not approach any single slope, so the limit of the difference quotient does not exist. However, even if a function is continuous at a point, it may not be differentiable there. For example, the absolute value function given by is continuous at , but it is not differentiable there. If is positive, then the slope of the secant line from 0 to is one; if is negative, then the slope of the secant line from to is .[12] This can be seen graphically as a "kink" or a "cusp" in the graph at . Even a function with a smooth graph is not differentiable at a point where its tangent is vertical: For instance, the function given by is not differentiable at . In summary, a function that has a derivative is continuous, but there are continuous functions that do not have a derivative.[13]

Most functions that occur in practice have derivatives at all points or almost every point. Early in the history of calculus, many mathematicians assumed that a continuous function was differentiable at most points.[14] Under mild conditions (for example, if the function is a monotone or a Lipschitz function), this is true. However, in 1872, Weierstrass found the first example of a function that is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere. This example is now known as the Weierstrass function.[15] In 1931, Stefan Banach proved that the set of functions that have a derivative at some point is a meager set in the space of all continuous functions. Informally, this means that hardly any random continuous functions have a derivative at even one point.[16]

Notation

[edit]One common way of writing the derivative of a function is Leibniz notation, introduced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1675, which denotes a derivative as the quotient of two differentials, such as and .[17] It is still commonly used when the equation is viewed as a functional relationship between dependent and independent variables. The first derivative is denoted by , read as "the derivative of with respect to ".[18] This derivative can alternately be treated as the application of a differential operator to a function, Higher derivatives are expressed using the notation for the -th derivative of . These are abbreviations for multiple applications of the derivative operator; for example, [19] Unlike some alternatives, Leibniz notation involves explicit specification of the variable for differentiation, in the denominator, which removes ambiguity when working with multiple interrelated quantities. The derivative of a composed function can be expressed using the chain rule: if and then [20]

Another common notation for differentiation is by using the prime mark in the symbol of a function . This notation, due to Joseph-Louis Lagrange, is now known as prime notation.[21] The first derivative is written as , read as " prime of ", or , read as " prime".[22] Similarly, the second and the third derivatives can be written as and , respectively.[23] For denoting the number of higher derivatives beyond this point, some authors use Roman numerals in superscript, whereas others place the number in parentheses, such as or .[24] The latter notation generalizes to yield the notation for the th derivative of .[19]

In Newton's notation or the dot notation, a dot is placed over a symbol to represent a time derivative. If is a function of , then the first and second derivatives can be written as and , respectively. This notation is used exclusively for derivatives with respect to time or arc length. It is typically used in differential equations in physics and differential geometry.[25] However, the dot notation becomes unmanageable for high-order derivatives (of order 4 or more) and cannot deal with multiple independent variables.

Another notation is D-notation, which represents the differential operator by the symbol .[19] The first derivative is written and higher derivatives are written with a superscript, so the -th derivative is . This notation is sometimes called Euler notation, although it seems that Leonhard Euler did not use it, and the notation was introduced by Louis François Antoine Arbogast.[26] To indicate a partial derivative, the variable differentiated by is indicated with a subscript, for example given the function , its partial derivative with respect to can be written or . Higher partial derivatives can be indicated by superscripts or multiple subscripts, e.g. and .[27]

Rules of computation

[edit]In principle, the derivative of a function can be computed from the definition by considering the difference quotient and computing its limit. Once the derivatives of a few simple functions are known, the derivatives of other functions are more easily computed using rules for obtaining derivatives of more complicated functions from simpler ones. This process of finding a derivative is known as differentiation.[28]

Rules for basic functions

[edit]The following are the rules for the derivatives of the most common basic functions. Here, is a real number, and is the base of the natural logarithm, approximately 2.71828.[29]

- Derivatives of powers:

- Functions of exponential, natural logarithm, and logarithm with general base:

- , for

- , for

- , for

- Trigonometric functions:

- Inverse trigonometric functions:

- , for

- , for

Rules for combined functions

[edit]The following rules allow deducing derivatives of many functions from the derivatives of the basic functions:[30]

- Constant rule: if is a constant function, then for all ,

- Sum rule:

- for all functions and and all real numbers and .

- Product rule:

- for all functions and . As a special case, this rule includes the fact whenever is a constant because by the constant rule.

- Quotient rule:

- for all functions and at all inputs where g ≠ 0.

- Chain rule for composite functions: If , then

Computation example

[edit]The derivative of the function given by is Here the second term was computed using the chain rule and the third term using the product rule. The known derivatives of the elementary functions , , , , and , as well as the constant , were also used.

Antidifferentiation

[edit]An antiderivative of a function is a function whose derivative is . Antiderivatives are not unique: if is an antiderivative of , then so is , where is any constant, because the derivative of a constant is zero.[31] The fundamental theorem of calculus shows that finding an antiderivative of a function gives a way to compute the areas of shapes bounded by that function. More precisely, the integral of a function over a closed interval is equal to the difference between the values of an antiderivative evaluated at the endpoints of that interval.[32]

Higher-order derivatives

[edit]Higher order derivatives are the result of differentiating a function repeatedly. Given that is a differentiable function, the derivative of is the first derivative, denoted as . The derivative of is the second derivative, denoted as , and the derivative of is the third derivative, denoted as . By continuing this process, if it exists, the th derivative is the derivative of the th derivative or the derivative of order . As has been discussed above, the generalization of derivative of a function may be denoted as .[33] A function that has successive derivatives is called times differentiable. If the -th derivative is continuous, then the function is said to be of differentiability class .[34] A function that has infinitely many derivatives is called infinitely differentiable or smooth.[35] Any polynomial function is infinitely differentiable; taking derivatives repeatedly will eventually result in a constant function, and all subsequent derivatives of that function are zero.[36]

One application of higher-order derivatives is in physics. Suppose that a function represents the position of an object at the time. The first derivative of that function is the velocity of an object with respect to time, the second derivative of the function is the acceleration of an object with respect to time,[28] and the third derivative is the jerk.[37]

In other dimensions

[edit]Vector-valued functions

[edit]A vector-valued function of a real variable sends real numbers to vectors in some vector space . A vector-valued function can be split up into its coordinate functions , meaning that . This includes, for example, parametric curves in or . The coordinate functions are real-valued functions, so the above definition of derivative applies to them. The derivative of is defined to be the vector, called the tangent vector, whose coordinates are the derivatives of the coordinate functions. That is,[38] if the limit exists. The subtraction in the numerator is the subtraction of vectors, not scalars. If the derivative of exists for every value of , then is another vector-valued function.[38]

Partial derivatives

[edit]Functions can depend upon more than one variable. A partial derivative of a function of several variables is its derivative with respect to one of those variables, with the others held constant. Partial derivatives are used in vector calculus and differential geometry. As with ordinary derivatives, multiple notations exist: the partial derivative of a function with respect to the variable is variously denoted by

among other possibilities.[39] It can be thought of as the rate of change of the function in the -direction.[40] Here ∂ is a rounded d called the partial derivative symbol. To distinguish it from the letter d, ∂ is sometimes pronounced "der", "del", or "partial" instead of "dee".[41] For example, let , then the partial derivative of function with respect to both variables and are, respectively: In general, the partial derivative of a function in the direction at the point is defined to be:[42]

This is fundamental for the study of the functions of several real variables. Let be such a real-valued function. If all partial derivatives with respect to are defined at the point , these partial derivatives define the vector which is called the gradient of at . If is differentiable at every point in some domain, then the gradient is a vector-valued function that maps the point to the vector . Consequently, the gradient determines a vector field.[43]

Directional derivatives

[edit]If is a real-valued function on , then the partial derivatives of measure its variation in the direction of the coordinate axes. For example, if is a function of and , then its partial derivatives measure the variation in in the and direction. However, they do not directly measure the variation of in any other direction, such as along the diagonal line . These are measured using directional derivatives. Given a vector , then the directional derivative of in the direction of at the point is:[44]

If all the partial derivatives of exist and are continuous at , then they determine the directional derivative of in the direction by the formula:[45]

Total derivative and Jacobian matrix

[edit]When is a function from an open subset of to , then the directional derivative of in a chosen direction is the best linear approximation to at that point and in that direction. However, when , no single directional derivative can give a complete picture of the behavior of . The total derivative gives a complete picture by considering all directions at once. That is, for any vector starting at , the linear approximation formula holds:[46] Similarly with the single-variable derivative, is chosen so that the error in this approximation is as small as possible. The total derivative of at is the unique linear transformation such that[46] Here is a vector in , so the norm in the denominator is the standard length on . However, is a vector in , and the norm in the numerator is the standard length on .[46] If is a vector starting at , then is called the pushforward of by .[47]

If the total derivative exists at , then all the partial derivatives and directional derivatives of exist at , and for all , is the directional derivative of in the direction . If is written using coordinate functions, so that , then the total derivative can be expressed using the partial derivatives as a matrix. This matrix is called the Jacobian matrix of at :[48]

Generalizations

[edit]The concept of a derivative can be extended to many other settings. The common thread is that the derivative of a function at a point serves as a linear approximation of the function at that point.

- An important generalization of the derivative concerns complex functions of complex variables, such as functions from (a domain in) the complex numbers to . The notion of the derivative of such a function is obtained by replacing real variables with complex variables in the definition.[49] If is identified with by writing a complex number as then a differentiable function from to is certainly differentiable as a function from to (in the sense that its partial derivatives all exist), but the converse is not true in general: the complex derivative only exists if the real derivative is complex linear and this imposes relations between the partial derivatives called the Cauchy–Riemann equations – see holomorphic functions.[50]

- Another generalization concerns functions between differentiable or smooth manifolds. Intuitively speaking such a manifold is a space that can be approximated near each point by a vector space called its tangent space: the prototypical example is a smooth surface in . The derivative (or differential) of a (differentiable) map between manifolds, at a point in , is then a linear map from the tangent space of at to the tangent space of at . The derivative function becomes a map between the tangent bundles of and . This definition is used in differential geometry.[51]

- Differentiation can also be defined for maps between vector space, such as Banach space, in which those generalizations are the Gateaux derivative and the Fréchet derivative.[52]

- One deficiency of the classical derivative is that very many functions are not differentiable. Nevertheless, there is a way of extending the notion of the derivative so that all continuous functions and many other functions can be differentiated using a concept known as the weak derivative. The idea is to embed the continuous functions in a larger space called the space of distributions and only require that a function is differentiable "on average".[53]

- Properties of the derivative have inspired the introduction and study of many similar objects in algebra and topology; an example is differential algebra. Here, it consists of the derivation of some topics in abstract algebra, such as rings, ideals, field, and so on.[54]

- The discrete equivalent of differentiation is finite differences. The study of differential calculus is unified with the calculus of finite differences in time scale calculus.[55]

- The arithmetic derivative involves the function that is defined for the integers by the prime factorization. This is an analogy with the product rule.[56]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Apostol 1967, p. 160; Stewart 2002, pp. 129–130; Strang et al. 2023, p. 224.

- ^ Apostol 1967, p. 160; Stewart 2002, p. 127; Strang et al. 2023, p. 220.

- ^ Gonick 2012, p. 83; Thomas et al. 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Gonick 2012, p. 88; Strang et al. 2023, p. 234.

- ^ Gonick 2012, p. 83; Strang et al. 2023, p. 232.

- ^ Gonick 2012, pp. 77–80.

- ^ Thompson 1998, pp. 34, 104; Stewart 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Thompson 1998, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Keisler 2012, pp. 902–904.

- ^ Keisler 2012, p. 45; Henle & Kleinberg 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Gonick 2012, p. 156; Thomas et al. 2014, p. 114; Strang et al. 2023, p. 237.

- ^ Gonick 2012, p. 149; Thomas et al. 2014, p. 113; Strang et al. 2023, p. 237.

- ^ Gonick 2012, p. 156; Thomas et al. 2014, p. 114; Strang et al. 2023, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Jašek 1922; Jarník 1922; Rychlík 1923.

- ^ David 2018.

- ^ Banach 1931, cited in Hewitt & Stromberg 1965.

- ^ Apostol 1967, p. 172; Cajori 2007, p. 204.

- ^ Moore & Siegel 2013, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, pp. 125–126.

- ^ In the formulation of calculus in terms of limits, various authors have assigned the symbol various meanings. Some authors such as Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, p. 119 and Stewart 2002, p. 177 do not assign a meaning to by itself, but only as part of the symbol . Others define as an independent variable, and define by . In non-standard analysis is defined as an infinitesimal. It is also interpreted as the exterior derivative of a function . See differential (infinitesimal) for further information.

- ^ Schwartzman 1994, p. 171; Cajori 1923, pp. 6–7, 10–12, 21–24.

- ^ Moore & Siegel 2013, p. 110; Goodman 1963, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, pp. 125–126; Cajori 2007, p. 228.

- ^ Choudary & Niculescu 2014, p. 222; Apostol 1967, p. 171.

- ^ Evans 1999, p. 63; Kreyszig 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Cajori 1923.

- ^ Apostol 1967, p. 172; Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Apostol 1967, p. 160.

- ^ Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007. See p. 133 for the power rule, pp. 115–116 for the trigonometric functions, p. 326 for the natural logarithm, pp. 338–339 for exponential with base , p. 343 for the exponential with base , p. 344 for the logarithm with base , and p. 369 for the inverse of trigonometric functions.

- ^ For constant rule and sum rule, see Apostol 1967, pp. 161, 164, respectively. For the product rule, quotient rule, and chain rule, see Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, pp. 111–112, 119, respectively. For the special case of the product rule, that is, the product of a constant and a function, see Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Strang et al. 2023, pp. 485–486.

- ^ Strang et al. 2023, pp. 552–559.

- ^ Apostol 1967, p. 160; Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Warner 1983, p. 5.

- ^ Debnath & Shah 2015, p. 40.

- ^ Carothers 2000, p. 176.

- ^ Stewart 2002, p. 193.

- ^ a b Stewart 2002, p. 893.

- ^ Stewart 2002, p. 947; Christopher 2013, p. 682.

- ^ Stewart 2002, p. 949.

- ^ Silverman 1989, p. 216; Bhardwaj 2005, See p. 6.4.

- ^ Mathai & Haubold 2017, p. 52.

- ^ Gbur 2011, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Varberg, Purcell & Rigdon 2007, p. 642.

- ^ Guzman 2003, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Davvaz 2023, p. 266.

- ^ Lee 2013, p. 72.

- ^ Davvaz 2023, p. 267.

- ^ Roussos 2014, p. 303.

- ^ Gbur 2011, pp. 261–264.

- ^ Gray, Abbena & Salamon 2006, p. 826.

- ^ Azegami 2020. See p. 209 for the Gateaux derivative, and p. 211 for the Fréchet derivative.

- ^ Funaro 1992, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Kolchin 1973, pp. 58, 126.

- ^ Georgiev 2018, p. 8.

- ^ Barbeau 1961.

References

[edit]- Apostol, Tom M. (June 1967), Calculus, Vol. 1: One-Variable Calculus with an Introduction to Linear Algebra, vol. 1 (2nd ed.), Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-00005-1

- Azegami, Hideyuki (2020), Shape Optimization Problems, Springer Optimization and Its Applications, vol. 164, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-981-15-7618-8, ISBN 978-981-15-7618-8, S2CID 226442409

- Banach, Stefan (1931), "Uber die Baire'sche Kategorie gewisser Funktionenmengen", Studia Math., 3 (3): 174–179, doi:10.4064/sm-3-1-174-179.

- Barbeau, E. J. (1961). "Remarks on an arithmetic derivative". Canadian Mathematical Bulletin. 4 (2): 117–122. doi:10.4153/CMB-1961-013-0. Zbl 0101.03702.

- Bhardwaj, R. S. (2005), Mathematics for Economics & Business (2nd ed.), Excel Books India, ISBN 9788174464507

- Cajori, Florian (1923), "The History of Notations of the Calculus", Annals of Mathematics, 25 (1): 1–46, doi:10.2307/1967725, hdl:2027/mdp.39015017345896, JSTOR 1967725

- Cajori, Florian (2007), A History of Mathematical Notations, vol. 2, Cosimo Classics, ISBN 978-1-60206-713-4

- Carothers, N. L. (2000), Real Analysis, Cambridge University Press

- Choudary, A. D. R.; Niculescu, Constantin P. (2014), Real Analysis on Intervals, Springer India, doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2148-7, ISBN 978-81-322-2148-7

- Christopher, Essex (2013), Calculus: A complete course, Pearson, p. 682, ISBN 9780321781079, OCLC 872345701

- Courant, Richard; John, Fritz (December 22, 1998), Introduction to Calculus and Analysis, Vol. 1, Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8955-2, ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4

- David, Claire (2018), "Bypassing dynamical systems: A simple way to get the box-counting dimension of the graph of the Weierstrass function", Proceedings of the International Geometry Center, 11 (2), Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: 53–68, arXiv:1711.10349, doi:10.15673/tmgc.v11i2.1028

- Davvaz, Bijan (2023), Vectors and Functions of Several Variables, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-981-99-2935-1, ISBN 978-981-99-2935-1, S2CID 259885793

- Debnath, Lokenath; Shah, Firdous Ahmad (2015), Wavelet Transforms and Their Applications (2nd ed.), Birkhäuser, doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-8418-1, ISBN 978-0-8176-8418-1

- Evans, Lawrence (1999), Partial Differential Equations, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-0772-2

- Eves, Howard (January 2, 1990), An Introduction to the History of Mathematics (6th ed.), Brooks Cole, ISBN 978-0-03-029558-4

- Funaro, Daniele (1992), Polynomial Approximation of Differential Equations, Lecture Notes in Physics Monographs, vol. 8, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-46783-0, ISBN 978-3-540-46783-0

- Gbur, Greg (2011), Mathematical Methods for Optical Physics and Engineering, Cambridge University Press, Bibcode:2011mmop.book.....G, ISBN 978-1-139-49269-0

- Georgiev, Svetlin G. (2018), Fractional Dynamic Calculus and Fractional Dynamic Equations on Time Scales, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73954-0, ISBN 978-3-319-73954-0

- Goodman, A. W. (1963), Analytic Geometry and the Calculus, The MacMillan Company

- Gonick, Larry (2012), The Cartoon Guide to Calculus, William Morrow, ISBN 978-0-06-168909-3

- Gray, Alfred; Abbena, Elsa; Salamon, Simon (2006), Modern Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces with Mathematica, CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-58488-448-4

- Guzman, Alberto (2003), Derivatives and Integrals of Multivariable Functions, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0035-2, ISBN 978-1-4612-0035-2

- Henle, James M.; Kleinberg, Eugene M. (2003), Infinitesimal Calculus, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-42886-4

- Hewitt, Edwin; Stromberg, Karl R. (1965), Real and abstract analysis, Springer-Verlag, Theorem 17.8, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-29794-0, ISBN 978-3-662-28275-5

- Jašek, Martin (1922), "Funkce Bolzanova" (PDF), Časopis pro Pěstování Matematiky a Fyziky (in Czech), 51 (2): 69–76, doi:10.21136/CPMF.1922.121916

- Jarník, Vojtěch (1922), "O funkci Bolzanově" (PDF), Časopis pro Pěstování Matematiky a Fyziky (in Czech), 51 (4): 248–264, doi:10.21136/CPMF.1922.109021. See the English version here.

- Keisler, H. Jerome (2012) [1986], Elementary Calculus: An Approach Using Infinitesimals (2nd ed.), Prindle, Weber & Schmidt, ISBN 978-0-871-50911-6

- Kolchin, Ellis (1973), Differential Algebra And Algebraic Groups, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-08-087369-5

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1991), Differential Geometry, New York: Dover, ISBN 0-486-66721-9

- Larson, Ron; Hostetler, Robert P.; Edwards, Bruce H. (February 28, 2006), Calculus: Early Transcendental Functions (4th ed.), Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 978-0-618-60624-5

- Lee, John M. (2013), Introduction to Smooth Manifolds, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 218, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21752-9, ISBN 978-0-387-21752-9

- Mathai, A. M.; Haubold, H. J. (2017), Fractional and Multivariable Calculus: Model Building and Optimization Problems, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-59993-9, ISBN 978-3-319-59993-9

- Moore, Will H.; Siegel, David A. (2013), A Mathematical Course for Political and Social Research, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15995-9

- Roussos, Ioannis M. (2014), Improper Riemann Integral, CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4665-8807-3

- Rychlík, Karel (1923), Über eine Funktion aus Bolzanos handschriftlichem Nachlasse

- Schwartzman, Steven (1994), The Words of Mathematics: An Etymological Dictionary of Mathematical Terms Used in English, Mathematical Association of American, ISBN 9781614445012

- Silverman, Richard A. (1989), Essential Calculus: With Applications, Courier Corporation, ISBN 9780486660974

- Stewart, James (December 24, 2002), Calculus (5th ed.), Brooks Cole, ISBN 978-0-534-39339-7

- Strang, Gilbert; et al. (2023), Calculus, volume 1, OpenStax, ISBN 978-1-947172-13-5

- Thomas, George B. Jr.; Weir, Maurice D.; Hass, Joel (2014). Thomas's Calculus (PDF) (Thirteenth ed.). Pearson PLC. ISBN 978-0-321-87896-0. Retrieved September 9, 2024.

- Thompson, Silvanus P. (September 8, 1998), Calculus Made Easy (Revised, Updated, Expanded ed.), New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-18548-0

- Varberg, Dale E.; Purcell, Edwin J.; Rigdon, Steven E. (2007), Calculus (9th ed.), Pearson Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0131469686

- Warner, Frank W. (1983), Foundations of Differentiable Manifolds and Lie Groups, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-90894-6

External links

[edit]Derivative

View on Grokipediaprovided this limit exists, representing the sensitivity of the function's output to infinitesimal changes in its input.[2] This concept underpins much of differential calculus and extends to higher-order derivatives, such as the second derivative , which describes concavity or acceleration-like behavior.[3] The development of the derivative traces back to the late 17th century, when Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz independently formulated the foundations of calculus, introducing notation like for the derivative and applying it to problems in physics and geometry.[4] Earlier precursors, including work by mathematicians like Archimedes on tangents and the Persian scholar Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī on cubic polynomials in the 12th century, anticipated aspects of instantaneous rates of change, but Newton and Leibniz's rigorous framework revolutionized mathematics.[5] Augustin-Louis Cauchy later provided a more precise limit-based definition in the 19th century, solidifying its role in analysis.[6] Derivatives have broad applications across science, engineering, and economics, enabling the modeling of dynamic systems and optimization.[7] In physics, the first derivative of position with respect to time yields velocity, while the second derivative gives acceleration, fundamental to kinematics and Newtonian mechanics.[8] In economics, derivatives quantify marginal quantities, such as the rate of change in cost or revenue functions, aiding decision-making in production and pricing.[9] They also support techniques like related rates for solving real-world problems involving varying quantities and Newton's method for numerical root-finding of equations.[10]