Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Art Deco in the United States

View on Wikipedia| Art Deco - United States | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: A New York Central Hudson locomotive in 1939; Delano South Beach and the National Hotels in Miami Beach (1947 and 1940); and the Chrysler Building (1930) and Prometheus statue at Rockefeller Center in New York City (1930) | |

| Years active | 1919-1939 |

| Location | United States |

The Art Deco style, which originated in France just before World War I, had an important impact on architecture and design in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. The most notable examples are the skyscrapers of New York City, including the Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and Rockefeller Center. It combined modern aesthetics, fine craftsmanship, and expensive materials, and became the symbol of luxury and modernity. While rarely used in residences, it was frequently used for office buildings, government buildings, train stations, movie theaters, diners and department stores. It also was frequently used in furniture, and in the design of automobiles, ocean liners, and everyday objects such as toasters and radio sets.

In the late 1930s, during the Great Depression, it featured prominently in the architecture of the immense public works projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administration and the Public Works Administration, such as the Golden Gate Bridge and Hoover Dam. The style competed throughout the period with the modernist architecture, and came to an abrupt end in 1939 with the beginning of World War II. The style was rediscovered in the 1960s, and many of the original buildings have been restored and are now historical landmarks.

Background

[edit]American Art Deco has roots in the style moderne popularized at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, Paris, from which the name Art Deco would be drawn retroactively (Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes). The United States did not officially participate, but Americans—including New York City architect Irwin Chanin and others[1]: 55 —visited the exposition,[2]: 47 and the government sent a delegation to the expo. Their resulting reports helped spread the style to America.[3]: 6 Other influences included German expressionism, the Austrian Secession, Art Nouveau, Cubism, and the ornament of African and Central and South American cultures.[1]: 8–9 [4]: 4

Architecture

[edit]American Art Deco architecture took different forms in different regions of the country, influenced by the local tastes, cultural influences, or laws.[2]: 42 In the 1920s, the style was often referred to as the "vertical style", referring to the new look of skyscrapers appearing in America's cities. In the 1930s and 40s, more horizontal, streamlined or "moderne" buildings became popular. Government buildings commissioned by the Works Progress Administration, with their fusion of moderne and classical elements, are called "WPA Moderne" or "Modern classic".[4]: vi

Skyscrapers

[edit]-

Radiator ornament decoration on the Chrysler Building in New York City (1928)

-

The Empire State Building in New York City (1931)

-

Crown of the RCA Victor Building, now the General Electric Building, in New York City (1930–31)

-

Entrance of the Fisher Building in Detroit, Michigan (1928)

-

Lobby of the Fisher Building in Detroit, Michigan (1928)

-

Chicago Board of Trade Building in Chicago, Illinois (1930)

-

The American Radiator Building in New York City by Raymond Hood (1924)

-

Buffalo City Hall in Buffalo, New York, Dietel, Wade & Jones, 1931

-

LeVeque Tower in Columbus, Ohio (1924)

-

City Hall in Los Angeles, California (1928)

-

The "Wings of Progress" atop the Times Square Building in Rochester, New York (1930)

The Art Deco style had been born in Paris, but no buildings were permitted in that city which were higher than Notre Dame Cathedral with the exception of the Eiffel Tower. As a result, the United States soon took the lead in building tall buildings. The first skyscrapers had been built in Chicago in the 1880s in the Beaux-Arts or neoclassical style. In the 1920s, New York City architects used the new Art Deco style to build the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building. The Empire State building was the tallest building in the world for forty years.

The decoration of the interior and exterior of the skyscrapers was classic Art Deco, with geometric shapes and zigzag patterns. The Chrysler Building, by William Van Alen (1928–30), updated the traditional gargoyles on Gothic cathedrals with sculptures on the building corners in the shape of Chrysler radiator ornaments.[5]

Another major landmark of the style was the RCA Victor Building, now the General Electric Building, by John Walter Cross. It was covered from top to bottom with zig-zags and geometric patterns, and had a highly ornamental crown with geometric spires and lightning bolts of stone. The exterior featured bas-relief sculptures by Leo Friedlander and Lee Lawrie, and a mosaic by Barry Faulkner that required more than a million pieces of enamel and glass.

While the skyscraper Art Deco style was mostly used for corporate office buildings, it also became popular for government buildings, since all city offices could be contained in one building on a minimal amount of land. The city halls of Los Angeles, California and Buffalo, New York were built in the style, and the new state capital building in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Movie theaters

[edit]-

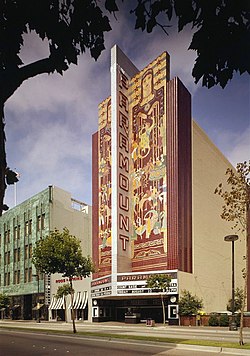

Four-story high grand lobby of the Paramount Theatre, Oakland (1932)

-

Paramount Theatre, Oakland; detail of the mosaic facade (1932)

-

The stage of Radio City Music Hall in New York City (1932)

Another important genre of Art Deco buildings is the movie theater. The Art Deco period coincided with the birth of the talking motion picture, and the age of enormous and lavishly decorated movie theaters. Many of these movie theaters still survive, though many have been divided in the interior into smaller screening halls.

Among the most famous examples are the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, which had a four-story high grand lobby, entered through twenty-seven doors, and could seat 3,746 people.[6]

Radio City Music Hall, located within the skyscraper complex of Rockefeller Center in New York City, was originally a theater for stage shows when it opened in 1932, but it quickly changed to the largest movie theater in the United States. It seats more than five thousand people, and still features a stage show of dancers.

In the 1930s, the streamline style appeared in movie theaters in smaller cities. The movie theater in Normal, Illinois (1937) is a classic surviving example.

Department stores and office buildings

[edit]-

Bullocks Wilshire, Los Angeles, John and Donald Parkinson, 1929

-

The facade of the Niagara Mohawk Building, in Syracuse, New York, (1932), a power utility company, features a statue of "The Spirit of Light"

-

Detail of the Kansas City Power and Light Building in Kansas City, Missouri (1931)

-

Interior of the Guardian Building (originally the Union Trust Building) in Detroit, Michigan (1928)

-

Lobby of the 450 Sutter Street building in San Francisco, by Timothy L. Pflueger (1929)

Following the lead of the skyscrapers of New York City, smaller in scale but no less ambitious in design, Art Deco office buildings and department stores appeared in cities across the United States. They were rarely built by banks, which wanted to appear conservative, but were often built by retail chains, public utilities, automobile companies and technology companies, which wanted to express modernity and progress. Syracuse, New York is home to the Niagara Mohawk Building, in Syracuse, New York, completed in 1932. was originally the home of the nation's largest electricity supplier. The facade, by the firm of Bley and Lyman, was designed to express the power and modernity of electricity; it features a statue called "The Spirit of Light" 8.5 meters high, made of stainless steel, as the central element of the facade. The Guardian Building, originally the Union Trust Building, is a rare example of a bank or financial institution using Art Deco. Its interior decoration was so elaborate that it became known as the "Cathedral of Commerce". [7]

The San Francisco architect Timothy L. Pflueger best known for the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, California, was another proponent of lavish Art Deco interiors and facades on office buildings. The interior of his downtown San Francisco office building, 450 Sutter Street, opened in 1929, was entirely covered with hieroglyphic-like designs and ornament, resembling a giant tapestry. [8]

The Streamline style

[edit]-

Chrome-plated table lamp by Donald Deskey (1927–31)

-

Chrysler Airflow sedan, designed by Carl Breer (1934)

-

Streamlined locomotive of the New York Central Railroad (1939)

-

The Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles (1935)

-

The San Francisco Maritime Museum (1936)

Streamline Moderne (or Streamline) was a variety of Art Deco which emerged during the mid-1930s. The architectural style was more sober and less decorative than earlier Art Deco buildings, more in tune with the somber mood of the Great Depression. Buildings in the style often resembled land-bound ships, with rounded corners, long horizontal lines, iron railings, and sometimes nautical features. Notable examples include the San Francisco Maritime Museum (1936), originally built as a public bath house next to the beach, and the Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, built in 1935 and closed in 1978. It was declared a historic landmark, but it was destroyed by a fire in 1989.

The style of decoration and industrial design was influenced by modern aerodynamic principles developed for aviation and ballistics to reduce air friction at high velocities. The bullet shapes were applied by designers to cars, trains, ships, and even objects not intended to move, such as refrigerators, gas pumps, and buildings. One of the first production vehicles in this style was the Chrysler Airflow of 1933. It was unsuccessful commercially, but the beauty and functionality of its design set a precedent; streamline moderne meant modernity. It continued to be used in car design well after World War II.[9][10][11][12]

Train stations and airports

[edit]-

Suburban Station (1930) in Philadelphia, built by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) to serve as its headquarters, now functions as the primary SEPTA Regional Rail station.

-

Cincinnati Union Terminal in Ohio (1933) now also functions as a museum and cultural center.

-

Union Station in Los Angeles (1939) is a mixture of Art Deco, Streamline Moderne, and Spanish Mission Revival

-

The Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia Airport (1937) was the New York terminal for the flights of Pan Am Clipper flying boats.

Art Deco was often associated with airplanes, trains and airships and was frequently chosen as the style for new transport terminals. The semi-dome of Cincinnati Union Terminal (1933) measures 180 feet (55 m) wide and 106 feet (32 m) high.[13] After the decline of railroad travel, most of the building was converted to other uses, including the Cincinnati Museum Center, though it is still used as an Amtrak station.

The Marine Air Terminal at LaGuardia Airport, built in 1939, was the first terminal for overseas flights from New York; it served the flying boats of Pan American World Airways which landed in the harbor. It survived destruction, and still contains a notable Art Deco mural called Flight, which was destroyed and then restored in the 1980s.

Union Station in Los Angeles was partially designed by John Parkinson and Donald B. Parkinson (the Parkinsons) who had also designed Los Angeles City Hall and other landmark Los Angeles buildings. The structure combines Art Deco, Mission Revival, and Streamline Moderne style, with architectural details such as eight-pointed stars, and even elements of Dutch Colonial Revival architecture.[14]

Hotels, resorts, and the Miami Beach style

[edit]-

Entrance of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel (1929)

-

Miami Beach Architectural District from 1920s–1930s

-

The Tides Hotel on Ocean Drive in Miami Beach (1933)

-

The Delano South Beach (1947) and National Hotel (1943) in Miami Beach

The Art Deco period saw an enormous increase in travel and tourism, by trains, automobiles, and airplanes. Several luxury hotels were built in the new style; the Waldorf-Astoria on Park Avenue in New York City, built in 1929 to replace a beaux-arts style building from the 1890s, was the tallest and largest hotel in the world when it was built.

The city of Miami Beach, Florida developed its own particular variant of Art Deco, and the style remained popular there until the late 1940s, well after other American cities. It became a popular tourist destination in the 1920s and 1930s, particularly attracting visitors from the Northeast United States during the winter. A large number of Art Deco hotels were built, which have been grouped together into an historical area, the Miami Beach Architectural District, and preserved, and many have been restored to their original appearance.[15][16] The district has an area of about one square kilometer, and contains both hotels and secondary residences, all about the same height, none higher than twelve or thirteen stories. Most have classic Art Deco characteristics; clear geometric shapes spread out horizontally; aerodynamic streamline features; and often a central tower breaking the horizontal, topped by a spire or dome. A particular Miami Art Deco feature is the palette of pastel colors, alternating with white stucco. The decoration features herons, sea shells, palm trees and sunrises and sunsets. The neon lighting at night highlights the Art Deco atmosphere. [17]

Diners and roadside architecture

[edit]-

The Modern Diner in Pawtucket, Rhode Island (1940) is modeled after streamlined railroad car.

Because of its high cost of construction, Art Deco was usually used only in large office buildings, government buildings and theaters, but it was sometimes used in smaller structures, such as diners and gas stations, particularly along highways. A notable example is the U-Drop Inn in Shamrock, Texas, located along U.S. Highway 66. It was built in 1936, and is now owned by the City of Shamrock, and is a historical landmark.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, a number of diners modeled after the cars of streamlined trains were produced, and appeared in different cities in the United States. In a few cases, real railroad cars were transformed into diners. A few survive, including the Modern Diner in Pawtucket, Rhode Island which is a registered landmark.

Furniture

[edit]

The art deco style also lended itself well to furniture. Consistent with many other household objects and buildings, furniture during this period became simplified, yet pleasing to the eye. This included metal bars as chair support, rounded feet, and decorated edges, all coming together to create a complex simplicity.

There were many furniture designers during this period including Kem Webber, Wirt Rowland, and some who continue to use the style later on, including Frank Pollaro.

Kem Webber is known for designing the furniture in the Warner Brother's Wester Theater, now known as the Wiltern Theater. Because the art deco style is known for its simplicity and lack of ornament, it is also a significantly less costly design.

Wirt Rowland, another furniture artist of this period, is known better for his creation of the Guardian Building in Detroit. He designed every bit of furniture within the rooms as well.

Frank Pollaro, known best for his creation of the Muppet Marquetry Desk, specialized in recreating French art deco furniture. His preferred material to work with is veneer. He designed the "Art Case" piano for Steinway & Sons company. He also created a number of other furniture pieces in this style, including a humidor (cigar storage).

Fine art

[edit]Murals

[edit]-

Mural Tragic Prelude depicting abolitionist John Brown in the Kansas State Capitol building, by John Steuart Curry (1930)

-

History of Southern Illinois, commissioned by the Federal Art Project for the library of the University of Southern Illinois (1935)

-

Workers sorting the mail, a mural in the U.S. Customs House in New York by Reginald Marsh (1936)

-

Art in the Tropics by Rockwell Kent in the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building (1938)

There was no specific Art Deco style of painting in the United States, though paintings were often used as decoration, especially in government buildings and office buildings. In the 1932 the Public Works of Art Project was created to give work to artists unemployed because the Great Depression. In a year, it commissioned more than fifteen thousand works of art. It was succeeded in 1935 by the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration, or WPA. prominent American artists were commissioned by the Federal Art Project to paint murals in government buildings, hospitals, airports, schools and universities. Some the America's most famous artists, including Grant Wood, Reginald Marsh, Georgia O'Keeffe and Maxine Albro took part in the program. The celebrated Mexican painter Diego Rivera also took part in the program, painting a mural. The paintings were in a variety of styles, including regionalism, social realism, and American scenic painting.

A few murals were also commissioned for Art Deco skyscrapers, notably Rockefeller Center in New York. Two murals were commissioned for the lobby, one by John Steuart Curry and another, Man at the Crossroads, by Diego Rivera. The owners of the building, the Rockefeller family, discovered that Rivera, a Communist, had slipped an image of Lenin into a crowd in the painting, and had it destroyed.[18] The mural was replaced with another by the Spanish artist José Maria Sert.[19]

Sculpture

[edit]-

Aluminum statue of Ceres atop the Chicago Board of Trade Building (1930)

-

Clock of the Chicago Board of Trade (1930)

-

Lobby clock in Rockefeller Center

-

Sculpture on the wall of Rockefeller Center

-

Doors of Cochise County Courthouse in Bisbee, Arizona

One of the largest Art Deco sculptures is the statue of Ceres, the goddess of grain and fertility, at the top of the Chicago Board of Trade. Made of aluminum, it stands 31 feet (9.4 meters) tall, and weighs 6,500 pounds. Ceres was chosen because the Chicago Board of Trade was one of the largest grain and commodities markets in the world.

Graphic arts

[edit]-

Poster for Chicago World's Fair (1933)

-

WPA Poster warning against crossing the street against the light (1937)

-

WPA poster advertising Port of Philadelphia (1937)

-

WPA "Swim for Health" poster (1938)

-

WPA Tourism promotion poster for state of Pennsylvania (1938)

The Art Deco style appeared early in the graphic arts, in the years just before World War I. It appeared in Paris in the posters and the costume designs of Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes, and in the catalogs of the fashion designers Paul Poiret. The illustrations of Georges Barbier, and Georges Lepape and the images in the fashion magazine La Gazette du bon ton perfectly captured the elegance and sensuality of the style. In the 1920s, the look changed; the fashions stressed were more casual, sportive and daring, with the woman models usually smoking cigarettes. American fashion magazines such as Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper's Bazaar quickly picked up the new style and popularized it in the United States. It also influenced the work of American book illustrators such as Rockwell Kent.[20]

In the 1930s a new genre of posters appeared in the United States during the Great Depression. The Federal Art Project hired American artists to create posters to promote tourism and cultural events.

PWA Moderne

[edit]

Government and public buildings of the 1930s and 1940s often combined elements of neoclassical, Beauxs-Arts, and Art Deco. This style is called PWA Moderne,[21] Federal Moderne,[22] Depression Moderne,[21] Classical Moderne,[21] Stripped Classicism, or Greco Deco.[23][22] These building-scale New Deal artworks were built during and shortly after the Great Depression as part of relief projects sponsored by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

The style evolved from Art Deco, drawing from the classical motifs of Beaux-Arts architecture as well; Stripped Classicism is also similar to Streamline Moderne,[22][24] but is less curvilinear and more classically-inspired. The architecture, which frequently has a monumental feel, often expressed itself in a rather severe Greco-Roman facade decorated with Deco-style shallow reliefs and/or Deco styled interior decoration featuring murals, tile mosaics, and sculpture. Public buildings and infrastructure, including post offices, train stations, public schools, libraries, civic centers, courthouses,[22] museums, bridges, and dams across the country were built in the style. Some private buildings, like banks, were also built in the style because such buildings radiated authority.[21]

Elements of the style

[edit]Typical elements of PWA Moderne buildings include:

- Highly symmetrical and balanced form

- Subtle reference to Classical orders

- Vertically recessed windows

- Flat, smooth surfaces of stone, stucco, granite, or concrete

- The use of stylized or simplified pilasters

Examples

[edit]Examples of PWA buildings and structures include:

Arizona/Nevada

[edit]- Hoover Dam (Boulder Dam) – on the Colorado River in Arizona and Nevada.[25][26]

- Arizona State Fairgrounds Grandstand (1936–1937) – Phoenix, Arizona. The exterior of the grandstand has 23 bas-relief panels by David Carrick Swing and Florence Blakeslee, that were funded by the Federal Art Project.[27][28]

- WPA Administration Building (1938) – at 19th Avenue and McDowell Road on the Arizona State Fairgrounds, Phoenix, Arizona. It was headquarters for Works Progress Administration−WPA projects in Arizona.[29][30][31]

Florida

[edit]

- Jacksonville

- Ed Austin Building (former Federal Courthouse, current State Attorney's Office), 1933, Marsh & Saxelbye

California

[edit]Greater Los Angeles

[edit]

- Burbank: Burbank City Hall, Allen Lutzi[32]

- Culver City: United States Post Office, 1940, Louis A. Simon and Neal Melick

- El Segundo: El Segundo Elementary School, 1936

- Hermosa Beach: North School, 1934 Samuel Lunden (Per File #19-45 of DSA Records); Pier Avenue School, 1939, March, Smith, and Powell

- Inglewood: Inglewood Memorial Park, buildings 1933 and 1940, Walter E. Erkes

- Lancaster: Post Office (1940), Louis A. Simon and former School Building (c. 1937)

- Lawndale: Leuzinger High School, T.C. Kistner & Cómo.; Kistner & Curtis; Eugene D. Birnbaum and Associates[32]

- Long Beach

- Jefferson Junior High School Building, 1936

- Long Beach Main Post Office, 1934, Louis A. Simon and James A. Wetmore

- Municipal Utilities Building, 1932, Dedrick and Bobbe

- Robert Louis Stevenson school, c. 1936

- Veteran's Memorial Building 1936–37, George Kahrs

- Los Angeles:

- Abraham Lincoln High School (Lincoln Heights), 1937–38, Albert C. Martin

- Carpenter Community Charter School

- Distribution Station #28, Department of Water and Power (West L.A.), 1945–46, G. E. Benker, engineer

- Federal Building and Post Office (now U.S. Federal Courthouse), 1938–1940, Louis A. Simon

- Hall of Administration, 1956–1961: A continuation of the PWA Moderne style in the 1950s

- Hollywood Branch Post Office, 1937, Claude Beellman, Allison and Allison

- Pacific Stock Exchange, 1929–30, Samuel E. Lunden

- Police and Fire Station of Venice, c. 1930

- San Pedro High School, 1935–1937, Gordon B. Kaufmann

- United States Post Office (San Pedro), 1936, Louis A. Simon

- Sepulveda Dam, 1941, flood control dam on the Los Angeles River in the San Fernando Valley, 1939–1941, War Department

- U.S. Customs House and Post Office (San Pedro), 1935

- U.S. Naval and Marine Corps Armory, 1939–40, Stiles Clements

- University of Southern California campus: Alan Hancock Foundation and Memorial Museum, 1940, Cram and Ferguson

- Pasadena:

- Armory Gallery (former California State Armory), 1932, Bennett and Haskell

- Grover Cleveland Elementary School, 1934

- San Gabriel: San Gabriel Union Church and School, 1936

- Santa Monica:

- Santa Monica City Hall, 1938–39, Donald B. Parkinson and J. M. Estep

- Post Office, Robert Dennis Murray, Louis A. Simon[32]

- Torrance:

- Auditorium (Torrance High School)

- Torrance Public Library, 1936, Walker & Eisen

- Whittier:[33]

- National Trust and Savings, c. 1935, William H. Harrison

- Whittier Post Office, 1935, Louis A. Simon

- Whittier-Union High School, 1939–40, William H. Harrison

Elsewhere in California

[edit]

- Bakersfield: Kern County Hall of Records, 1939 remodel, Chris Brewer

- Fresno: County Hall of Records, 1937, Allied Architects of Fresno[34]

- Jackson: Amador County Courthouse, 1940 remodel, George Sellon[35]

- Oakland: Alameda County Courthouse, 1939[36]

- Salinas: Monterey County Courthouse, 1937, Robert Stanton & Charles Butner[37]

- San Diego: San Diego County Administration Center, 1938, Samuel Wood Hamill, William Templeton Johnson, Richard Requa, Louis John Gill[38]

- San Francisco: San Francisco Mint, 1937

- San Luis Obispo: San Luis Obispo County Courthouse, 1940, Walker & Eisen[39]

- Santa Cruz: Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium, 1939[40]

- Visalia: Tulare County Courthouse (now Department of Public Social Services), 1935, Ernest Kump[41][42]

District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.)

[edit]

- Folger Shakespeare Library, 1932, Paul Philippe Cret[22]

- Library of Congress Annex (John Adams Building), 1939, Pierson & Wilson[22]

- Harry S Truman Building (particularly the War Department building) of the United States Department of State, 1939, Underwood & Foster[43]

Iowa

[edit]

- Animosa: Jones County Courthouse, 1937, Dougher, Rich and Woodburn

- Audubon: Audubon County Court House, 1940, Keffer and Jones

- Atlantic: Cass County Courthouse, 1934, Dougher, Rich and Woodburn

- Burlington: Des Moines County Court House, 1940, Keffer and Jones

- Charles City: Floyd County Court House, 1940, Hansen & Waggoner

- Dakota City: Humboldt County Courthouse, 1939

- Independence: Buchanan County Court House, 1940, Dougher, Rich and Woodburn

- Indianola: Warren County Court House, 1939, Keffer and Jones

- Mason City: Mason City Engine House No. 2, 1939, Hansen & Waggoner

- St. Olaf: St. Olaf Auditorium, 1939

- Sioux City: Sioux City Municipal Auditorium, 1938–50, Knute E. Westerlind

- Waukon: Allamakee County Court House, 1940, Charles Altfillisch

- Waverly: Bremer County Court House, 1937, Mortimer Cleveland

Minnesota

[edit]

- Minneapolis: Minneapolis Armory, 1935–36, P.C. Bettenburg; Walter H. Wheeler

Mississippi

[edit]- Mississippi: Amory National Guard Armory, 1937–38, Overstreet & Town

Nevada

[edit]- Pioche: Lincoln County Courthouse, 1938, A. Lacy Worswick; L.F. Dow

Oregon

[edit]Tennessee

[edit]Texas

[edit]- Austin: Heman Marion Sweatt Travis County Courthouse 1930,1931, Page Brothers

- Kilgore: Kilgore College 1935

- Longview: Gregg County Courthouse 1932, Voelcker and Dixon[44]

Utah

[edit]- Orderville: Valley School

- Provo: Superintendent's Residence at the Utah State Hospital, 1934 (Colonial Revival/PWA Moderne)

- Santaquin: Santaquin Junior High School

Washington

[edit]WPA Moderne

[edit]WPA Moderne has been used to describe restrained architecture at historic places such as the Administration Building for the City of Grand Forks at the Grand Forks Airport (built 1941–43) in North Dakota, the Municipal Auditorium and City Hall (Leoti, Kansas) (built 1939–42) in Kansas, and the Kearney National Guard Armory in Nebraska. (See Category:WPA Moderne architecture). Relative to the Public Works Administration, which terminated in 1944, the Works Progress Administration program, terminated in 1943, focused on smaller, often rural, projects providing employment.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes and citations

[edit]- ^ a b Berenholtz, Richard; Carol Willis (2005). New York Deco. New York: Welcome Books. ISBN 9781599620787.

- ^ a b Robinson, Cervin; Bletter, Rosemarie Hagg (1975). Skyscraper Style. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kurshan, Virginia (September 20, 2011). "Madison Belmont Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Robins, Anthony (2017). New York Art Deco: A Guide to Gotham's Jazz Age Architecture. Albany, New York: Excelsior Editions. ISBN 978-1438463964.

- ^ Morel2012, p. 151.

- ^ Stone, Susannah Harris. The Oakland Paramount, Lancaster-Miller Publishers (1982) - ISBN 0-89581-607-5

- ^ Duncan 1988, p. 193.

- ^ Duncan 1988, p. 198.

- ^ Gartman, David (1994). Auto Opium. Routledge. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-415-10572-9.

- ^ "Curves of Steel: Streamlined Automobile Design". Phoenix Art Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Armi, C. Edson (1989). The Art of American Car Design. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-271-00479-2.

- ^ Hinckley, James (2005). The Big Book of Car Culture: The Armchair Guide to Automotive Americana. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-7603-1965-9.

- ^ Cincinnati Union Terminal Architectural Information Sheet Archived 2010-06-20 at the Wayback Machine. Cincinnati Museum Center. Retrieved on February 8, 2010

- ^ Waldie, D.J. (May 1, 2014) "Union Station: L.A.'s nearly perfect time machine" Op-Ed, Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Our Mission Statement". Miami Design Preservation League. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ Brown, Joseph (2009). "Miami Beach Art Deco". Miami Beach MagazineFebruary 2010. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010.

- ^ Duncan 1988, pp. 203–205.

- ^ "Archibald MacLeish Criticism". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ^ Morel 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Duncan 1988, pp. 148–150.

- ^ a b c d "Fullerton Heritage". Archived from the original on 2018-06-27.

- ^ a b c d e f The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume 1, Joan M. Marter, ed., p. 147

- ^ James M. Goode (1 December 1981). Capital Losses: A Cultural History of Washington's Destroyed Buildings. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 178, 188. ISBN 978-0-87474-479-8. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Architecture and Construction

- ^ Arizona.edu: "The New Deal in Arizona: Connections to Our Historic Landscape", University of Arizona, The New Deal in Arizona Chapter of the National New Deal Preservation Association.

- ^ Arizona.edu: Photos of New Deal projects in Arizona

- ^ KJZZ.org: "Did You Know: Arizona State Fairgrounds 110 Years Old", by Nadine Arroyo Rodriguez, 21 August 2015; with images of the WPA Grandstand and Administration Building.

- ^ Living New Deal Blog: Arizona State Fairgrounds Stadium and Art

- ^ Phoenix New Times: "Demolition of WPA Civic Building at Arizona State Fairgrounds on Temporary Hold", 18 July 2014.

- ^ YouTube: "1938 WPA Administration Building in 1949 & 1969"

- ^ "Azfamily.com: "$200,000 to go toward preserving State Fairgrounds WPA Administration Building"". Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ a b c "PWA Moderne", Los Angeles Conservancy website

- ^ An Arch Guidebook to Los Angeles, Robert Winter, p. 322

- ^ "Fresno County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Amador County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Alameda County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Monterey County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "San Diego County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "San Luis Obispo County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium - Santa Cruz CA - Living New Deal". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Tulare County, US Courthouses". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Tulare County Department of Public Social Services - Visalia CA - Living New Deal". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Harry S. Truman Federal Building, Washington, DC". Archived from the original on December 19, 2018.

- ^ "Gregg County Courthouse, Longview, Texas". www.texasescapes.com. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "William K. Nakamura Federal Courthouse - Seattle WA - Living New Deal". Retrieved 11 Aug 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bayer, Patricia (1999). Art Deco Architecture: Design, Decoration and Detail from the Twenties and Thirties. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28149-9.

- Benton, Charlotte; Benton, Tim; Wood, Ghislaine; Baddeley, Oriana (2003). Art Deco: 1910–1939. Bulfinch. ISBN 978-0-8212-2834-0.

- Breeze, Carla (2003). American Art Deco: Modernistic Architecture and Regionalism. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01970-4.

- Duncan, Alastair (1986). American Art Deco. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50023-465-5.

- Duncan, Alastair (1988). Art déco. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 2-87811-003-X.

- Duncan, Alastair (2009). Art Deco Complete: The Definitive Guide to the Decorative Arts of the 1920s and 1930s. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-81098046-4.

- Gallagher, Fiona (2002). Christie's Art Deco. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-86205-509-4.

- Hillier, Bevis (1968). Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. Studio Vista. ISBN 978-0-289-27788-1.

- Long, Christopher (2007). Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12102-5.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1996). Art Deco Painting. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3576-1.

- Morel, Guillaume (2012). Art Déco (in French). Éditions Place des Victoires. ISBN 978-2-8099-0701-8.

- Savage, Rebecca Binno; Kowalski, Greg (2004). Art Deco in Detroit (Images of America). Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-3228-8.

- Vincent, G.K. (2008). A History of Du Cane Court: Land, Architecture, People and Politics. Woodbine Press. ISBN 978-0-9541675-1-6.

- Ward, Mary; Ward, Neville (1978). Home in the Twenties and Thirties. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0785-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Art Deco in the United States at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Art Deco in the United States at Wikimedia Commons