Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of Iran

View on Wikipedia

This article's lead section may be too long. (July 2025) |

| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

The History of Iran (also known as Persia) is intertwined with Greater Iran, which is a region encompassing all of the areas that have witnessed significant settlement or influence by the Iranian peoples and the Iranian languages – chiefly the Persians and the Persian language. Central to this region is the Iranian plateau, now largely covered by modern Iran. The most pronounced impact of Iranian history can be seen stretching from Anatolia in the west to the Indus Valley in the east, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, and parts of Central Asia. It also overlaps or mingles with the histories of many other major civilizations, such as India, China, Greece, Rome, and Egypt.

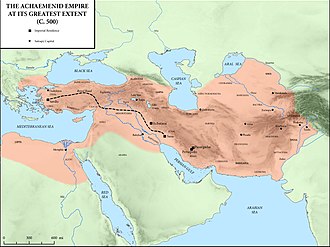

Iran is home to one of the world's oldest continuous major civilizations, with historical and urban settlements dating back to the 5th millennium BC.[1] The Iranian plateau's western regions integrated into the rest of the ancient Near East with the Elamites (in Ilam and Khuzestan), the Kassites (in Kuhdesht), the Gutians (in Luristan), and later with other peoples like the Urartians (in Oshnavieh and Sardasht) near Lake Urmia[2][3][4][5] and the Mannaeans (in Piranshahr, Saqqez and Bukan) in Kurdistan.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel called the Persians the "first Historical People" in his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History.[15] The sustained Iranian empire is understood to have begun with the rise of the Medes during the Iron Age, when Iran was unified as a nation under the Median kingdom in the 7th century BC.[16] By 550 BC, the Medes were sidelined by the conquests of Cyrus the Great, who brought the Persians to power with the establishment of the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus' ensuing campaigns enabled the Persian realm's expansion across most of West Asia and much of Central Asia, and his successors would eventually conquer parts of Southeast Europe and North Africa to preside over the largest empire the world had yet seen. In the 4th century BC, the Achaemenid Empire was conquered by the Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great, whose death led to the establishment of the Seleucid Empire over the bulk of former Achaemenid territory. In the following century, Greek rule of the Iranian plateau came to an end with the rise of the Parthian Empire, which also conquered large parts of the Seleucids' Anatolian, Mesopotamian, and Central Asian holdings. While the Parthians were succeeded by the Sasanian Empire in the 2nd century, Iran remained a leading power for the next millennium, although the majority of this period was marked by the Roman–Persian Wars.

In the 7th century, the Muslim conquest of Iran resulted in the Sasanian Empire's annexation by the Rashidun Caliphate and the beginning of the Islamization of Iran. In spite of repeated invasions by foreign powers, such as the Arabs, Turks, and Mongols, among others, the Iranian national identity was repeatedly asserted in the face of assimilation, allowing it to develop as a distinct political and cultural entity. While the early Muslim conquests had caused the decline of Zoroastrianism, which had been Iran's majority and official religion up to that point, the achievements of prior Iranian civilizations were absorbed into the nascent Islamic empires and expanded upon during the Islamic Golden Age. Nomadic tribes overran parts of the Iranian plateau during the Late Middle Ages and into the early modern period, negatively impacting the region.[17] By 1501, however, the nation was reunified by the Safavid dynasty, which initiated Iranian history's most momentous religious change since the original Muslim conquest by converting Iran to Shia Islam.[18][19] Iran again emerged as a leading world power, especially in rivalry with the Turkish-ruled Ottoman Empire. In the 19th century, Iran came into conflict with the Russian Empire, which annexed the South Caucasus by the end of the Russo-Persian Wars.[20]

The Safavid period (1501–1736) is becoming more recognized as an important time in Iran's history by scholars in both Iran and the West. In 1501, the Safavid dynasty became the first local dynasty to rule all of Iran since the Arabs overthrew the Sasanid empire in the 7th century. For eight and a half centuries, Iran was mostly just a geographical area with no independent government, ruled by various foreign powers—Arabs, Turks, Mongols, and Tartars. The Mongol invasions in the 13th century were a turning point in Iran's history and in Islam. The Mongols destroyed the historical caliphate, which had been a symbol of unity for the Islamic world for 600 years. During the long foreign rule, Iranians kept their unique culture and national identity, and they used this chance to regain their political independence.[21]

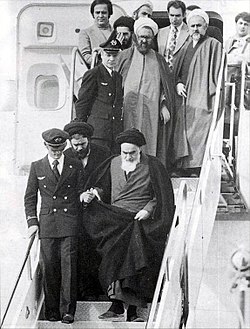

In the 1940s there were hopes that Iran could become a constitutional monarchy, but a 1953 coup aided by U.S. and U.K. removed the elected prime minister, and Iran was ruled as an autocracy under the Shah with American support from that time until the revolution. The Iranian monarchy lasted until the Islamic Revolution in 1979, when the country was officially declared an Islamic republic.[22][23] Since then, it has experienced significant political, social, and economic changes. The establishment of an Islamic republic led to a major restructuring of the country's political system. Iran's foreign relations have been shaped by regional conflicts, beginning with the Iran–Iraq War and persisting through many Arab countries; ongoing tensions with Israel, the United States, and the Western world; and the Iranian nuclear program, which has been a point of contention in international diplomacy. Despite international sanctions and internal challenges, Iran remains a key player in regional and global geopolitics.

Prehistory

[edit]Paleolithic

[edit]The earliest archaeological artifacts in Iran were found in the Kashafrud and Ganj Par sites that are thought to date back to 100,000 years ago in the Middle Paleolithic.[24] Mousterian stone tools made by Neanderthals have also been found.[25] There are more cultural remains of Neanderthals dating back to the Middle Paleolithic period, which mainly have been found in the Zagros region and fewer in central Iran at sites such as Kobeh, Kunji, Bisitun Cave, Tamtama, Warwasi, and Yafteh Cave.[26] In 1949, a Neanderthal radius was discovered by Carleton S. Coon in Bisitun Cave.[27] Evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic periods are known mainly from the Zagros Mountains in the caves of Kermanshah and Khorramabad and a few number of sites in Piranshahr, Alborz and Central Iran. During this time, people began creating rock art in Iran.[28][29]

Neolithic to Chalcolithic

[edit]Early agricultural communities such as Chogha Golan in the 11th millennium BC[30][31] along with settlements such as Chogha Bonut (the earliest village in Elam) in the 9th millennium BC[32][33] began to flourish in and around the Zagros Mountains.[34] Around about the same time, the earliest-known clay vessels and modelled human and animal terracotta figurines were produced at Ganj Dareh.[34] There are 10,000-year-old human and animal figurines from Tepe Sarab in Kermanshah Province among many other ancient artefacts.[35]

The south-western part of Iran was part of the Fertile Crescent where most of humanity's first major crops were grown, in villages such as Susa (where a settlement was first founded possibly as early as 4395 BC)[36]: 46–47 and settlements such as Chogha Mish, dating back to 6800 BC;[37][38] there are 7,000-year-old jars of wine excavated in the Zagros Mountains[39] (now on display at the University of Pennsylvania) and ruins of 7,000-year-old settlements such as Tepe Sialk are further testament to that. The two main Neolithic Iranian settlements were Ganj Dareh and the hypothetical Zayandeh River Culture.[40]

Bronze Age

[edit]

The Kura–Araxes culture (circa 3400 BC—ca. 2000 BC) stretched from northwestern Iran up into the neighbouring regions of the Caucasus and Anatolia.[41][42] Susa is one of the oldest-known settlements of Iran and the world. The general perception among archaeologists is that Susa was an extension of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, hence incorporating many aspects of Mesopotamian culture.[43][44] In its later history, Susa became the capital of Elam, which emerged as a state founded 4000 BC.[36]: 45–46 There are also dozens of prehistoric sites across the Iranian plateau pointing to the existence of ancient cultures and urban settlements in the fourth millennium BC.[37] One of the earliest civilizations on the Iranian plateau was the Jiroft culture in southeastern Iran in the province of Kerman.

Iran is one of the most artefact-rich archaeological sites in the Middle East. Archaeological excavations in Jiroft led to the discovery of several objects belonging to the 4th millennium BC.[45] There is a large quantity of objects decorated with highly distinctive engravings of animals, mythological figures, and architectural motifs. The objects and their iconography are considered unique. Many are made from chlorite, a grey-green soft stone; others are in copper, bronze, terracotta, and even lapis lazuli. Recent excavations at the sites have produced the world's earliest inscription which pre-dates Mesopotamian inscriptions.[46][47]

There are records of numerous other ancient civilizations on the Iranian plateau before the emergence of Iranian peoples during the Early Iron Age. The Early Bronze Age saw the rise of urbanization into organized city-states and the invention of writing (the Uruk period) in the Near East. While Bronze Age Elam made use of writing from an early time, the Proto-Elamite script remains undeciphered, and records from Sumer pertaining to Elam are scarce.

Russian historian Igor M. Diakonoff states that the modern inhabitants of Iran are descendants of mainly non-Indo-European groups, more specifically of pre-Iranic inhabitants of the Iranian Plateau: "It is the autochthones of the Iranian plateau, and not the Proto-Indo-European tribes of Europe, which are, in the main, the ancestors, in the physical sense of the word, of the present-day Iranians."[48]

Early Iron Age

[edit]

Records become more tangible with the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its records of incursions from the Iranian plateau. As early as the 20th century BC, tribes came to the Iranian plateau from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. The arrival of Iranians on the Iranian plateau forced the Elamites to relinquish one area of their empire after another and to take refuge in Elam, Khuzestan and the nearby area, which only then became coterminous with Elam.[49] Bahman Firuzmandi says that the southern Iranians might be intermixed with the Elamite peoples living in the plateau.[50] By the mid-1st millennium BC, Medes, Persians, and Parthians populated the Iranian plateau. Until the rise of the Medes, they all remained under Assyrian domination, like the rest of the Near East. In the first half of the 1st millennium BC, parts of what is now Iranian Azerbaijan were incorporated into Urartu.

Classical antiquity

[edit]Median and Achaemenid Empires (678–330 BC)

[edit]-

The tomb of Cyrus the Great

-

Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis

-

Ruins of the Apadana, Persepolis

-

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis

In 646 BC, Assyrian king Ashurbanipal sacked Susa, which ended Elamite supremacy in the region.[51] For over 150 years Assyrian kings of nearby northern Mesopotamia had been wanting to conquer Median tribes of western Iran.[52] Under pressure from Assyria, the small kingdoms of the western Iranian plateau coalesced into increasingly larger and more centralized states.[51]

In the second half of the 7th century BC, the Medes gained their independence and were united by Deioces. In 612 BC, Cyaxares, Deioces' grandson, and the Babylonian king Nabopolassar invaded Assyria and laid siege to and eventually destroyed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, which led to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[53] Urartu was later on conquered and dissolved as well by the Medes.[54][55] The Medes are credited with founding Iran as a nation and empire, and established the first Iranian empire, the largest of its day until Cyrus the Great established a unified empire of the Medes and Persians, leading to the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC).

Cyrus the Great overthrew, in turn, the Median, Lydian, and Neo-Babylonian empires, creating an empire far larger than Assyria. He was better able, through more benign policies, to reconcile his subjects to Persian rule; the longevity of his empire was one result. The Persian king, like the Assyrian, was also "King of Kings", xšāyaθiya xšāyaθiyānām (shāhanshāh in modern Persian) – "great king", Megas Basileus, as known by the Greeks.

Cyrus's son, Cambyses II, conquered the last major power of the region, ancient Egypt, causing the collapse of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt. Since he became ill and died before, or while, leaving Egypt, stories developed, as related by Herodotus, that he was struck down for impiety against the ancient Egyptian deities. After the death of Cambyses II, Darius ascended the throne by overthrowing the legitimate Achaemenid monarch Bardiya, and then quelling rebellions throughout his kingdom. As the winner, Darius based his claim on membership in a collateral line of the Achaemenid Empire.

Darius' first capital was at Susa, and he started the building program at Persepolis. He rebuilt a canal between the Nile and the Red Sea, a forerunner of the modern Suez Canal. He improved the extensive road system, and it is during his reign that mentions are first made of the Royal Road (shown on map), a great highway stretching all the way from Susa to Sardis with posting stations at regular intervals. Major reforms took place under Darius. Coinage, in the form of the daric (gold coin) and the shekel (silver coin), was standardized (coinage had been invented over a century before in Lydia c. 660 BC but not standardized),[56] and administrative efficiency increased.

The Old Persian language appears in royal inscriptions, written in a specially adapted version of the cuneiform script. Under Cyrus the Great and Darius, the Persian Empire eventually became the largest empire in human history up until that point, ruling and administrating over most of the known world,[57] as well as spanning the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa. The greatest achievement was the empire itself. The Persian Empire represented the world's first superpower[58][59] that was based on a model of tolerance and respect for other cultures and religions.[60]

In the late 6th century BC, Darius launched his European campaign, in which he defeated the Paeonians, conquered Thrace, and subdued all coastal Greek cities, as well as defeating the European Scythians around the Danube river.[61] In 512/511 BC, Macedon became a vassal kingdom of Persia.[61]

In 499 BC, Athens lent support to a revolt in Miletus, which resulted in the sacking of Sardis. This led to an Achaemenid campaign against mainland Greece known as the Greco-Persian Wars, which lasted the first half of the 5th century BC, and is known as one of the most important wars in European history. In the First Persian invasion of Greece, the Persian general Mardonius re-subjugated Thrace and made Macedon a full part of Persia.[61] The war eventually turned out in defeat, however. Darius' successor Xerxes I launched the Second Persian invasion of Greece. At a crucial moment in the war, about half of mainland Greece was overrun by the Persians, including all territories to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth,[62][63] however, this was also turned out in a Greek victory, following the battles of Plataea and Salamis, by which Persia lost its footholds in Europe, and eventually withdrew from it.[64] During the Greco-Persian wars, the Persians gained major territorial advantages. They captured and razed Athens twice, once in 480 BC and again in 479 BC. However, after a string of Greek victories the Persians were forced to withdraw, thus losing control of Macedonia, Thrace and Ionia. Fighting continued for several decades after the successful Greek repelling of the Second Invasion with numerous Greek city-states under the Athens' newly formed Delian League, which eventually ended with the peace of Callias in 449 BC, ending the Greco-Persian Wars. In 404 BC, following the death of Darius II, Egypt rebelled under Amyrtaeus. Later pharaohs successfully resisted Persian attempts to reconquer Egypt until 343 BC, when Egypt was reconquered by Artaxerxes III.

Greek conquest and Seleucid Empire (312 BC–248 BC)

[edit]

From 334 BC to 331 BC, Alexander the Great defeated Darius III in the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, swiftly conquering the Achaemanid Empire by 331 BC. Alexander's empire broke up shortly after his death, and Alexander's general, Seleucus I Nicator, tried to take control of Iran, Mesopotamia, and later Syria and Anatolia. His empire was the Seleucid Empire. He was killed in 281 BC by Ptolemy Keraunos.

Parthian Empire (248 BC–224 AD)

[edit]

The Parthian Empire—ruled by the Parthians, a group of northwestern Iranian people—was the realm of the Arsacid dynasty. This latter reunited and governed the Iranian plateau after the Parni conquest of Parthia and defeating the Seleucid Empire in the late 3rd century BC. It intermittently controlled Mesopotamia between c. 150 BC and 224 AD and absorbed Eastern Arabia.

Parthia was the eastern arch-enemy of the Roman Empire, and it limited Rome's expansion beyond Cappadocia (central Anatolia). The Parthian armies included two types of cavalry: the heavily armed and armored cataphracts and the lightly armed but highly-mobile mounted archers.

For the Romans, who relied on heavy infantry, the Parthians were too hard to defeat, as both types of cavalry were much faster and more mobile than foot soldiers. The Parthian shot used by the Parthian cavalry was most notably feared by the Roman soldiers, which proved pivotal in the crushing Roman defeat at the Battle of Carrhae. On the other hand, the Parthians found it difficult to occupy conquered areas as they were unskilled in siege warfare. Because of these weaknesses, neither the Romans nor the Parthians were able completely to annex each other's territory.

The Parthian empire subsisted for five centuries, longer than most Eastern Empires. The end of this empire came at last in 224 AD, when the empire's organization had loosened and the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassal peoples, the Persians under the Sasanians. However, the Arsacid dynasty continued to exist for centuries onwards in Armenia, the Iberia, and the Caucasian Albania, which were all eponymous branches of the dynasty.

Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD)

[edit]

The first shah of the Sasanian Empire, Ardashir I, started reforming the country economically and militarily. For a period of more than 400 years, Iran was once again one of the leading powers in the world, alongside its neighbouring rival, the Roman and then Byzantine Empires.[65][66] The empire's territory, at its height, encompassed all of today's Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Abkhazia, Dagestan, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, parts of Afghanistan, Turkey, Syria, parts of Pakistan, Central Asia, Eastern Arabia, and parts of Egypt.

Most of the Sasanian Empire's lifespan was overshadowed by the frequent Byzantine–Sasanian wars, a continuation of the Roman–Parthian Wars and the all-comprising Roman–Persian Wars; the last was the longest-lasting conflict in human history. Started in the first century BC by their predecessors, the Parthians, and Romans, the last Roman–Persian War was fought in the seventh century. The Persians defeated the Romans at the Battle of Edessa in 260 and took emperor Valerian prisoner for the remainder of his life. Eastern Arabia was conquered early on. During Khosrow II's rule in 590–628, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine and Lebanon were also annexed to the Empire. The Sassanians called their empire Erânshahr ("Dominion of the Aryans", i.e., of Iranians).[67]

A chapter of Iran's history followed after roughly 600 years of conflict with the Roman Empire. During this time, the Sassanian and Romano-Byzantine armies clashed for influence in Anatolia, the western Caucasus (mainly Lazica and the Kingdom of Iberia; modern-day Georgia and Abkhazia), Mesopotamia, Armenia and the Levant. Under Justinian I, the war came to an uneasy peace with payment of tribute to the Sassanians. However, the Sasanians used the deposition of the Byzantine emperor Maurice as a casus belli to attack the Empire. After many gains, the Sassanians were defeated at Issus, Constantinople, and finally Nineveh, resulting in peace. With the conclusion of the over 700 years lasting Roman–Persian Wars through the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, which included the very siege of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, the war-exhausted Persians lost the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah (632) in Hilla (present-day Iraq) to the invading Muslim forces.

The Sasanian era, encompassing the length of Late Antiquity, is considered to be one of the most important and influential historical periods in Iran, and had a major impact on the world. In many ways, the Sassanian period witnessed the highest achievement of Persian civilization and constitutes the last great Iranian Empire before the adoption of Islam. Persia influenced Roman civilization considerably during Sassanian times,[68] their cultural influence extending far beyond the empire's territorial borders, reaching as far as Western Europe,[69] Africa,[70] China and India[71] and also playing a prominent role in the formation of both European and Asiatic medieval art.[72]

This influence carried forward to the Muslim world. The dynasty's unique and aristocratic culture transformed the Islamic conquest and destruction of Iran into a Persian Renaissance.[69] Much of what later became known as Islamic culture, architecture, writing, and other contributions to civilization, were taken from the Sassanian Persians into the broader Muslim world.[73]

Medieval period

[edit]Early Islamic period

[edit]Islamic conquest of Persia (633–651)

[edit]

In 633, when the Sasanian king Yazdegerd III was ruling over Iran, the Muslims under Umar invaded the country right after it had been in a bloody civil war. Several Iranian nobles and families such as king Dinar of the House of Karen, and later Kanarangiyans of Khorasan, mutinied against their Sasanian overlords. Although the House of Mihran had claimed the Sasanian throne under the two prominent generals Bahrām Chōbin and Shahrbaraz, it remained loyal to the Sasanians during its struggle against the Arabs, but the Mihrans were eventually betrayed and defeated by their own kinsmen, the House of Ispahbudhan, under their leader Farrukhzad, who had mutinied against Yazdegerd III. Yazdegerd III fled from one district to another until a local miller killed him for his purse at Merv in 651.[74] By 674, Muslims had conquered Khorasan (which included Khorasan province and modern Afghanistan and parts of Transoxiana).

The Muslim conquest of Persia ended the Sasanian Empire and led to the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. Over time, the majority of Iranians converted to Islam. Most of the aspects of the previous Persian civilizations were not discarded but were absorbed by the new Islamic polity. As Bernard Lewis has commented:

These events have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders. Both perceptions are of course valid, depending on one's angle of vision.[75]

Umayyad era and Muslim incursions into the Caspian coast

[edit]After the fall of the Sasanian Empire in 651, the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate adopted many Persian customs, especially the administrative and the court mannerisms. Arab provincial governors were undoubtedly either Persianized Arameans or ethnic Persians; certainly Persian remained the language of official business of the caliphate until the adoption of Arabic toward the end of the 7th century,[76] when in 692 minting began at the capital Damascus. The Islamic coins evolved from imitations of Sasanian coins (as well as Byzantine), and the Pahlavi script on the coinage was replaced with Arabic alphabet.

During the Umayyad Caliphate, the Arab conquerors imposed Arabic as the primary language of the subject peoples throughout their empire. Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, who was not happy with the prevalence of the Persian language in the divan, ordered the official language of the conquered lands to be replaced by Arabic, sometimes by force.[77] In al-Biruni's From the Remaining Signs of Past Centuries for example it is written:

When Qutaibah bin Muslim under the command of Al-Hajjaj bin Yousef was sent to Khwarazmia with a military expedition and conquered it for the second time, he swiftly killed whoever wrote the Khwarazmian native language that knew of the Khwarazmian heritage, history, and culture. He then killed all their Zoroastrian priests and burned and wasted their books, until gradually the illiterate only remained, who knew nothing of writing, and hence their history was mostly forgotten.[78]

Several historians see the rule of the Umayyads as setting up the "dhimmah" to increase taxes from the dhimmis to benefit the Muslim Arab community financially and by discouraging conversion.[79] Governors lodged complaints with the caliph when he enacted laws that made conversion easier, depriving the provinces of revenues. In the 7th century, when many non-Arabs such as Persians entered Islam, they were recognized as mawali ("clients") and treated as second-class citizens by the ruling Arab elite until the end of the Umayyad Caliphate. During this era, Islam was initially associated with the ethnic identity of the Arab and required formal association with an Arab tribe and the adoption of the client status of mawali.[79] The half-hearted policies of the late Umayyads to tolerate non-Arab Muslims and Shias had failed to quell unrest among these minorities.

However, all of Iran was still not under Arab control; the region of Daylam was under the control of the Daylamites, while Tabaristan was under Dabuyid and Paduspanid control, and the Mount Damavand region was under Masmughans of Damavand. The Arabs had invaded these regions several times but achieved no decisive result because of the inaccessible terrain of the regions. The most prominent ruler of the Dabuyids, known as Farrukhan the Great (r. 712–728), managed to hold his domains during his long struggle against the Arab general Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, who was defeated by a combined Dailamite-Dabuyid army and was forced to retreat from Tabaristan.[80]

With the death of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 743, the Islamic world was launched into civil war. Abu Muslim was sent to Khorasan by the Abbasid Caliphate initially as a propagandist and then to revolt on their behalf. He took Merv defeating the Umayyad governor Nasr ibn Sayyar. He became the de facto Abbasid governor of Khurasan. During the same period, the Dabuyid ruler Khurshid declared independence from the Umayyads but was shortly forced to recognize Abbasid authority. In 750, Abu Muslim became the leader of the Abbasid army and defeated the Umayyads at the Battle of the Zab. Abu Muslim stormed Damascus later that year.

Abbasid period and autonomous Iranian dynasties

[edit]

The Abbasid army consisted primarily of Khorasanians and was led by Abu Muslim. It contained both Iranian and Arab elements, and the Abbasids enjoyed both Iranian and Arab support. The Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750.[81] According to Amir Arjomand, the Abbasid Revolution essentially marked the end of the Arab empire and the beginning of a more inclusive, multi-ethnic state in the Middle East.[82] One of the first changes the Abbasids made after taking power from the Umayyads was to move the empire's capital to Iraq. The latter region was influenced by Persian history and culture, and moving the capital was part of the Persian mawali demand for Arab influence in the empire. The city of Baghdad was constructed on the Tigris River, in 762, to serve as the Abbasid capital.[83]

The Abbasids established the position of vizier like Barmakids in their administration, which was the equivalent of a "vice-caliph", or second-in-command. Eventually, this change meant that many caliphs under the Abbasids ended up in a much more ceremonial role than ever before, with the vizier in real power. A new Persian bureaucracy began to replace the old Arab aristocracy, and the entire administration reflected these changes, demonstrating that the new dynasty was different in many ways from the Umayyads.[83]

By the 9th century, Abbasid control began to wane as regional leaders sprang up in the far corners of the empire to challenge the central authority of the Abbasid caliphate.[83] The Abbasid caliphs began enlisting mamluks, Turkic-speaking warriors, who had been moving out of Central Asia into Transoxiana as slave warriors as early as the 9th century. Shortly thereafter the real power of the Abbasid caliphs began to wane; eventually, they became religious figureheads while the warrior slaves ruled.[81]

The 9th century also saw the revolt by native Zoroastrians, known as the Khurramites, against oppressive Arab rule. The movement was led by a Persian freedom fighter Babak Khorramdin. Babak's Iranianizing[84] rebellion, from its base in Azerbaijan in northwestern Iran,[85] called for a return of the political glories of the Iranian[86] past. The Khorramdin rebellion of Babak spread to the western and central parts of Iran and lasted more than 20 years before it was defeated when Babak was betrayed by Afshin, a senior general of the Abbasid Caliphate.

As the power of the Abbasid caliphs diminished, a series of dynasties rose in various parts of Iran, some with considerable influence and power. Among the most important of these overlapping dynasties were the Tahirids in Khorasan (821–873); the Saffarids in Sistan (861–1003, their rule lasted as maliks of Sistan until 1537); and the Samanids (819–1005), originally at Bukhara. The Samanids eventually ruled an area from central Iran to Pakistan.[81]

By the early 10th century, the Abbasids almost lost control to the growing Persian faction known as the Buyid dynasty (934–1062). Since much of the Abbasid administration had been Persian anyway, the Buyids were quietly able to assume real power in Baghdad. The Buyids were defeated in the mid-11th century by the Seljuq Turks, who continued to exert influence over the Abbasids, while publicly pledging allegiance to them. The balance of power in Baghdad remained as such – with the Abbasids in power in name only – until the Mongol invasion of 1258 sacked the city and definitively ended the Abbasid dynasty.[83]

During the Abbasid period an enfranchisement was experienced by the mawali and a shift was made in political conception from that of a primarily Arab empire to one of a Muslim empire[87] and c. 930 a requirement was enacted that required all bureaucrats of the empire be Muslim.[79]

Islamic golden age, Shu'ubiyya movement and Persianization process

[edit]

Islamization was a long process by which Islam was gradually adopted by the majority population of Iran. Richard Bulliet's "conversion curve" indicates that only about 10% of Iran converted to Islam during the relatively Arab-centric Umayyad period. Beginning in the Abbasid period, with its mix of Persian as well as Arab rulers, the Muslim percentage of the population rose. As Persian Muslims consolidated their rule of the country, the Muslim population rose from approximately 40% in the mid-9th century to close to 90% by the end of the 11th century.[87] Seyyed Hossein Nasr suggests that the rapid increase in conversion was aided by the Persian nationality of the rulers.[88] Although Persians adopted the religion of their conquerors, over the centuries they worked to protect and revive their distinctive language and culture, a process known as Persianization. Arabs and Turks participated in this attempt.[89][90][91]

In the 9th and 10th centuries, non-Arab subjects of the Ummah created a movement called Shu'ubiyyah in response to the privileged status of Arabs. Most of those behind the movement were Persian, but references to Egyptians, Berbers and Aramaeans are attested.[92] Citing as its basis Islamic notions of equality of races and nations, the movement was primarily concerned with preserving Persian culture and protecting Persian identity, though within a Muslim context.

The Samanid dynasty led the revival of Persian culture and the first important Persian poet after the arrival of Islam, Rudaki, was born during this era and was praised by Samanid kings. The Samanids also revived many ancient Persian festivals. Their successor, the Ghaznawids, who were of non-Iranian Turkic origin, also became instrumental in the revival of Persian culture.[93]

The culmination of the Persianization movement was the Shahnameh, the national epic of Iran, written almost entirely in Persian. This voluminous work, reflects Iran's ancient history, its unique cultural values, its pre-Islamic Zoroastrian religion, and its sense of nationhood. According to Bernard Lewis:[75]

Iran was indeed Islamized, but it was not Arabized. Persians remained Persians. And after an interval of silence, Iran re-emerged as a separate, different and distinctive element within Islam, eventually adding a new element even to Islam itself. Culturally, politically, and most remarkable of all even religiously, the Iranian contribution to this new Islamic civilization is of immense importance. The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavour, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution. In a sense, Iranian Islam is a second advent of Islam itself, a new Islam sometimes referred to as Islam-i Ajam. It was this Persian Islam, rather than the original Arab Islam, that was brought to new areas and new peoples: to the Turks, first in Central Asia and then in the Middle East in the country which came to be called Turkey, and of course to India. The Ottoman Turks brought a form of Iranian civilization to the walls of Vienna...

The Islamization of Iran was to yield deep transformations within the cultural, scientific, and political structure of Iran's society: The blossoming of Persian literature, philosophy, medicine and art became major elements of the newly forming Muslim civilization. Inheriting a heritage of thousands of years of civilization, and being at the "crossroads of the major cultural highways",[96] contributed to Persia emerging as what culminated into the "Islamic Golden Age". During this period, hundreds of scholars and scientists vastly contributed to technology, science and medicine, later influencing the rise of European science during the Renaissance.[97]

The most important scholars of almost all of the Islamic sects and schools of thought were Persian or lived in Iran, including the most notable and reliable Hadith collectors of Shia and Sunni like Shaikh Saduq, Shaikh Kulainy, Hakim al-Nishaburi, Imam Muslim and Imam Bukhari, the greatest theologians of Shia and Sunni like Shaykh Tusi, Imam Ghazali, Imam Fakhr al-Razi and Al-Zamakhshari, the greatest physicians, astronomers, logicians, mathematicians, metaphysicians, philosophers and scientists like Avicenna and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, and the greatest shaykhs of Sufism like Rumi and Abdul-Qadir Gilani.

Persianate states and dynasties (977–1219)

[edit]

In 977, a Turkic governor of the Samanids, Sabuktigin, conquered Ghazna (in present-day Afghanistan) and established a dynasty, the Ghaznavids, that lasted to 1186.[81] The Ghaznavid empire grew by taking all of the Samanid territories south of the Amu Darya in the last decade of the 10th century, and eventually occupied parts of Eastern Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and north-west India.[83] The Ghaznavids are generally credited with launching Islam into a mainly Hindu India. The invasion of India was undertaken in 1000 by the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud and continued for several years. They were unable to hold power for long, however, particularly after the death of Mahmud in 1030. By 1040 the Seljuqs had taken over the Ghaznavid lands in Iran.[83]

The Seljuqs, who like the Ghaznavids were Persianate in nature and of Turkic origin, slowly conquered Iran over the course of the 11th century.[81] The dynasty had its origins in the Turcoman tribal confederations of Central Asia and marked the beginning of Turkic power in the Middle East. They established a Sunni Muslim rule over parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to 14th centuries. They set the Seljuq Empire that stretched from Anatolia in the west to western Afghanistan in the east and the western borders of modern-day China in the north-east; and was the target of the First Crusade. Today they are regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Western Turks, the present-day inhabitants of Turkey, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, and they are remembered as great patrons of Persian culture, art, literature, and language.[89][98][99]

The founder of the dynasty, Tughril Beg, turned his army against the Ghaznavids in Khorasan. He moved south and then west, conquering but not wasting the cities in his path. In 1055 the caliph in Baghdad gave Tughril Beg robes, gifts, and the title King of the East. Under Tughril Beg's successor, Malik Shah (1072–1092), Iran enjoyed a cultural and scientific renaissance, largely attributed to his brilliant Iranian vizier, Nizam al Mulk. These leaders established the observatory where Omar Khayyám did much of his experimentation for a new calendar, and they built religious schools in all the major towns. They brought Abu Hamid Ghazali, one of the greatest Islamic theologians, and other eminent scholars to the Seljuq capital at Baghdad and encouraged and supported their work.[81]

When Malik Shah I died in 1092, the empire split as his brother and four sons quarreled over the apportioning of the empire among themselves. In Anatolia, Malik Shah I was succeeded by Kilij Arslan I who founded the Sultanate of Rûm and in Syria by his brother Tutush I. In Persia he was succeeded by his son Mahmud I whose reign was contested by his other three brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Muhammad I in Baghdad and Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan. As Seljuq power in Iran weakened, other dynasties began to step up in its place, including a resurgent Abbasid caliphate and the Khwarezmshahs. The Khwarezmid Empire was a Sunni Muslim Persianate dynasty, of East Turkic origin, that ruled in Central Asia. Originally vassals of the Seljuqs, they took advantage of the decline of the Seljuqs to expand into Iran.[100] In 1194 the Khwarezmshah Ala ad-Din Tekish defeated the Seljuq sultan Toghrul III in battle and the Seljuq empire in Iran collapsed. Of the former Seljuq Empire, only the Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia remained.

A serious internal threat to the Seljuqs during their reign came from the Nizari Ismailis, a secret sect with headquarters at Alamut Castle between Rasht and Tehran. They controlled the immediate area for more than 150 years and sporadically sent out adherents to strengthen their rule by murdering important officials. Several of the various theories on the etymology of the word assassin derive from these killers.[81] Parts of northwestern Iran were conquered in the early 13th century AD by the Kingdom of Georgia, led by Tamar the Great.[101]

Mongol conquest and rule (1219–1358)

[edit]Mongol invasion (1219–1221)

[edit]

The Khwarazmian dynasty only lasted for a few decades, until the arrival of the Mongols. Genghis Khan had unified the Mongols, and under him the Mongol Empire quickly expanded in several directions. In 1218, it bordered Khwarezm. At that time, the Khwarazmian Empire was ruled by Ala ad-Din Muhammad (1200–1220). Muhammad, like Genghis, was intent on expanding his lands and had gained the submission of most of Iran. He declared himself shah and demanded formal recognition from the Abbasid caliph Al-Nasir. When the caliph rejected his claim, Ala ad-Din Muhammad proclaimed one of his nobles caliph and unsuccessfully tried to depose an-Nasir.

The Mongol invasion of Iran began in 1219, after two diplomatic missions to Khwarezm sent by Genghis Khan had been massacred. During 1220–21 Bukhara, Samarkand, Herat, Tus and Nishapur were razed, and the populations were slaughtered. The Khwarezm-Shah fled, to die on an island off the Caspian coast.[102] During the invasion of Transoxiana in 1219, along with the main Mongol force, Genghis Khan used a Chinese specialist catapult unit in battle; they were used again in 1220 in Transoxania. The Chinese may have used the catapults to hurl gunpowder bombs, since they already had them by this time.[103]

While Genghis Khan was conquering Transoxania and Persia, several Chinese who were familiar with gunpowder were serving in Genghis's army.[104] "Whole regiments" entirely made out of Chinese were used by the Mongols to command bomb hurling trebuchets during the invasion of Iran.[105] Historians have suggested that the Mongol invasion had brought Chinese gunpowder weapons to Central Asia. One of these was the huochong, a Chinese mortar.[106] Books written around the area afterward depicted gunpowder weapons which resembled those of China.[107]

Before his death in 1227, Genghis had reached western Azerbaijan, pillaging and burning many cities along the way after entering into Iran from its north east. The Mongol invasion was by and large disastrous to the Iranians. Although the Mongol invaders eventually converted to Islam and accepted the culture of Iran, the Mongol destruction in Iran and other regions of the Islamic heartland (particularly the historical Khorasan region, mainly in Central Asia) marked a major change of direction for the region. Much of the six centuries of Islamic scholarship, culture, and infrastructure was destroyed as the invaders leveled cities, burned libraries, and in some cases replaced mosques with Buddhist temples.[108][109][110] The Mongols killed many Iranian civilians. Destruction of qanat irrigation systems in the north east of Iran destroyed the pattern of relatively continuous settlements, producing many abandoned towns which were relatively quite good with irrigation and agriculture.[111] In 1221, Genghis Khan destroyed the city of Gurganj. Most if not all the ancient Iranic Khwarazmian people were killed or pushed out, paving the way for the Turkification of Khwarazm.

Ilkhanate (1256–1335)

[edit]

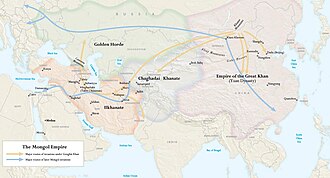

After Genghis's death, Iran was ruled by several Mongol commanders. Genghis' grandson, Hulagu Khan, was tasked with the westward expansion of Mongol dominion. However, by the time he ascended to power, the Mongol Empire had already dissolved, dividing into different factions. Arriving with an army, he established himself in the region and founded the Ilkhanate, a breakaway state of the Mongol Empire, which would rule Iran for the next 80 years and become Persian in the process.

Hulagu Khan seized Baghdad in 1258 and put the last Abbasid caliph to death. The westward advance of his forces was stopped by the Mamelukes, however, at the Battle of Ain Jalut in Palestine in 1260. Hulagu's campaigns against the Muslims also enraged Berke, khan of the Golden Horde and a convert to Islam. Hulagu and Berke fought against each other, demonstrating the weakening unity of the Mongol empire.

The rule of Hulagu's great-grandson, Ghazan (1295–1304) saw the establishment of Islam as the state religion of the Ilkhanate. Ghazan and his famous Iranian vizier, Rashid al-Din, brought Iran a partial and brief economic revival. The Mongols lowered taxes for artisans, encouraged agriculture, rebuilt and extended irrigation works, and improved the safety of the trade routes. As a result, commerce increased dramatically.

Items from India, China, and Iran passed easily across the Asian steppes, and these contacts culturally enriched Iran. For example, Iranians developed a style of painting based on a unique fusion of solid, two-dimensional Mesopotamian painting with the feathery, light brush strokes and other motifs characteristic of China. After Ghazan's nephew Abu Said died in 1335 the Ilkhanate lapsed into civil war and was divided between several petty dynasties – most prominently the Jalayirids, Muzaffarids, Sarbadars and Kartids. The mid-14th-century Black Death killed about 30% of the country's population.[112]

Sunnism and Shiism in pre-Safavid Iran

[edit]

Prior to the rise of the Safavid Empire, Sunni Islam was the dominant religion, accounting for around 90% of the population at the time. According to Mortaza Motahhari the majority of Iranian scholars and masses remained Sunni until the time of the Safavids.[113] The domination of Sunnis did not mean Shia were rootless in Iran. The writers of The Four Books of Shia were Iranian, as well as many other great Shia scholars.

The domination of the Sunni creed during the first nine Islamic centuries characterized the religious history of Iran during this period. There were however some exceptions to this general domination which emerged in the form of the Zaydīs of Tabaristan (see Alid dynasties of northern Iran), the Buyids, the Kakuyids, the rule of Sultan Muhammad Khudabandah (r. Shawwal 703-Shawwal 716/1304–1316) and the Sarbedaran.[114]

Apart from this domination there existed, firstly, throughout these nine centuries, Shia inclinations among many Sunnis of this land and, secondly, original Imami Shiism as well as Zaydī Shiism had prevalence in some parts of Iran. During this period, Shia in Iran were nourished from Kufah, Baghdad and later from Najaf and Hillah.[114] Shiism was the dominant sect in Tabaristan, Qom, Kashan, Avaj and Sabzevar. In many other areas merged population of Shia and Sunni lived together.[citation needed]

During the 10th and 11th centuries, Fatimids sent Ismailis Da'i (missioners) to Iran as well as other Muslim lands. When Ismailis divided into two sects, Nizaris established their base in Iran. Hassan-i Sabbah conquered fortresses and captured Alamut in 1090 AD. Nizaris used this fortress until a Mongol raid in 1256.[citation needed]

After the Mongol raid and fall of the Abbasids, Sunni hierarchies faltered. Not only did they lose the caliphate but also the status of official madhhab. Their loss was the gain of Shia, whose centre wasn't in Iran at that time. Several local Shia dynasties like Sarbadars were established during this time.[citation needed]

The main change occurred in the beginning of the 16th century, when Ismail I founded the Safavid dynasty and initiated a religious policy to recognize Shi'a Islam as the official religion of the Safavid Empire, and the fact that modern Iran remains an officially Shi'ite state is a direct result of Ismail's actions.[citation needed]

Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

[edit]Iran remained divided until the arrival of Timur, a Turco-Mongol[115] belonging to the Timurid dynasty. Like its predecessors, the Timurid Empire was also part of the Persianate world. After establishing a power base in Transoxiana, Timur invaded Iran in 1381 and eventually conquered most of it. Timur's campaigns were known for their brutality; many people were slaughtered and several cities were destroyed.[116]

His regime was characterized by tyranny and bloodshed, but also by its inclusion of Iranians in administrative roles and its promotion of architecture and poetry. His successors, the Timurids, maintained a hold on most of Iran until 1452, when they lost the bulk of it to Black Sheep Turkmen. The Black Sheep Turkmen were conquered by the White Sheep Turkmen under Uzun Hasan in 1468; Uzun Hasan and his successors were the masters of Iran until the rise of the Safavids.[116]

Sufi poet Hafez's popularity became firmly established in the Timurid era that saw the compilation and widespread copying of his divan. Sufis were often persecuted by orthodox Muslims who considered their teachings blasphemous. Sufism developed a symbolic language rich with metaphors to obscure poetic references to provocative philosophical teachings. Hafez concealed his own Sufi faith, even as he employed the secret language of Sufism (developed over hundreds of years) in his own work, and he is sometimes credited with having "brought it to perfection".[117] His work was imitated by Jami, whose own popularity grew to spread across the full breadth of the Persianate world.[118]

The Kara Koyunlu were a Turkmen[119] tribal federation that ruled over northwestern Iran and surrounding areas from 1374 to 1468. The Kara Koyunlu expanded their conquest to Baghdad, however, internal fighting, defeats by the Timurids, rebellions by the Armenians in response to their persecution,[120] and failed struggles with the Ag Qoyunlu led to their eventual demise.[121] Aq Qoyunlu were Turkmen[122][123] under the leadership of the Bayandur tribe,[124] tribal federation of Sunni Muslims who ruled over most of Iran and large parts of surrounding areas from 1378 to 1501 CE. Aq Qoyunlu emerged when Timur granted them all of Diyar Bakr in present-day Turkey. Afterward, they struggled with their rival Oghuz Turks, the Qara Qoyunlu. While the Aq Qoyunlu were successful in defeating Kara Koyunlu, their struggle with the emerging Safavid dynasty led to their downfall.[125]

Early modern period

[edit]Persia underwent a revival under the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736), the most prominent figure of which was Shah Abbas I. Some historians credit the Safavid dynasty for founding the modern nation-state of Iran. Iran's contemporary Shia character and significant segments of Iran's current borders take their origin from this era (e.g. Treaty of Zuhab).

Safavid Empire (1501–1736)

[edit]

The Safavid dynasty was one of the most significant ruling dynasties of Iran and "is often considered the beginning of modern Persian history".[126] They ruled one of the greatest Iranian empires after the Muslim conquest of Persia[127] and established the Twelver school of Shi'a Islam[18] as the official religion of their empire, marking one of the most important turning points in Muslim history. The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722 (experiencing a brief restoration from 1729 to 1736) and at their height, they controlled all of modern Iran, Azerbaijan and Armenia, most of Georgia, the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Safavid Iran was one of the Islamic "gunpowder empires", along with its neighbours, its archrival and principal enemy the Ottoman Empire, and to the east, the Mughal Empire.

The Safavid ruling dynasty was founded by Ismāil, who styled himself Shāh Ismāil I.[128] Practically worshipped by his Qizilbāsh followers, Ismāil invaded Shirvan to avenge the death of his father, Shaykh Haydar, who had been killed during his siege of Derbent, in Dagestan. Afterwards he went on a campaign of conquest, and following the capture of Tabriz in July 1501, he enthroned himself as the Shāh of Iran,[129]: 324 [130][131] minted coins in this name, and proclaimed Shi'ism the official religion of his domain.[18]

Although initially the masters of Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan only, the Safavids had, in fact, won the struggle for power in Iran which had been going on for nearly a century between various dynasties and political forces following the fragmentation of the Kara Koyunlu and the Aq Qoyunlu. A year after his victory in Tabriz, Ismāil proclaimed most of Iran as his domain, and[18] quickly conquered and unified Iran under his rule. Soon afterwards, the new Safavid Empire rapidly conquered regions, nations, and peoples in all directions, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, parts of Georgia, Mesopotamia (Iraq), Kuwait, Syria, Dagestan, large parts of what is now Afghanistan, parts of Turkmenistan, and large chunks of Anatolia, laying the foundation of its multi-ethnic character which would heavily influence the empire itself (most notably the Caucasus and its peoples).

Tahmasp I, the son and successor of Ismail I, carried out multiple invasions in the Caucasus which had been incorporated in the Safavid empire since Shah Ismail I and for many centuries afterwards, and started with the trend of deporting and moving hundreds of thousands of Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians to Iran's heartlands. Initially only solely put in the royal harems, royal guards, and minor other sections of the Empire, Tahmasp believed he could eventually reduce the power of the Qizilbash, by creating and fully integrating a new layer in Iranian society. As Encyclopædia Iranica states, for Tahmasp, the problem circled around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qizilbash, who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Safavid family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement.[132] With this new Caucasian layer in Iranian society, the undisputed might of the Qizilbash (who functioned much like the ghazis of the neighbouring Ottoman Empire) would be questioned and fully diminished as society would become fully meritocratic.

Shah Abbas I and his successors would significantly expand this policy and plan initiated by Tahmasp, deporting during his reign alone around some 200,000 Georgians, 300,000 Armenians and 100,000–150,000 Circassians to Iran, completing the foundation of a new layer in Iranian society. With this, and the complete systematic disorganisation of the Qizilbash by his personal orders, he eventually fully succeeded in replacing the power of the Qizilbash, with that of the Caucasian ghulams. These new Caucasian elements (the so-called ghilman / غِلْمَان / "servants"), almost always after conversion to Shi'ism depending on given function would be, unlike the Qizilbash, fully loyal only to the Shah. The other masses of Caucasians were deployed in all other possible functions and positions available in the empire, as well as in the harem, regular military, craftsmen, farmers, etc. This system of mass usage of Caucasian subjects remained to exist until the fall of the Qajar dynasty.

The greatest of the Safavid monarchs, Shah Abbas I the Great (1587–1629) came to power in 1587 aged 16. Abbas I first fought the Uzbeks, recapturing Herat and Mashhad in 1598, which had been lost by his predecessor Mohammad Khodabanda by the Ottoman–Safavid War (1578–1590). Then he turned against the Ottomans, the archrivals of the Safavids, recapturing Baghdad, eastern Iraq, the Caucasian provinces, and beyond by 1618. Between 1616 and 1618, following the disobedience of his most loyal Georgian subjects Teimuraz I and Luarsab II, Abbas carried out a punitive campaign in his territories of Georgia, devastating Kakheti and Tbilisi and carrying away 130,000[134] – 200,000[135][136] Georgian captives towards mainland Iran. His new army, which had dramatically been improved with the advent of Robert Shirley and his brothers following the first diplomatic mission to Europe, pitted the first crushing victory over the Safavids' archrivals, the Ottomans in the above-mentioned 1603–1618 war and would surpass the Ottomans in military strength. He also used his new force to dislodge the Portuguese from Bahrain (1602) and Hormuz (1622) with aid of the English navy, in the Persian Gulf.

He expanded commercial links with the Dutch East India Company and established firm links with the European royal houses, which had been initiated by Ismail I earlier on by the Habsburg–Persian alliance. Thus Abbas I was able to break the dependence on the Qizilbash for military might and therefore was able to centralize control. The Safavid dynasty had already established itself during Shah Ismail I, but under Abbas I it really became a major power in the world along with its archrival the Ottoman Empire, against whom it became able to compete with on equal foot. It also started the promotion of tourism in Iran. Under their rule Persian Architecture flourished again and saw many new monuments in various Iranian cities, of which Isfahan is the most notable example.

Except for Shah Abbas the Great, Shah Ismail I, Shah Tahmasp I, and Shah Abbas II, many of the Safavid rulers were ineffectual, often being more interested in their women, alcohol and other leisure activities. The end of Abbas II's reign in 1666, marked the beginning of the end of the Safavid dynasty. Despite falling revenues and military threats, many of the later shahs had lavish lifestyles. Shah Soltan Hosain (1694–1722) in particular was known for his love of wine and disinterest in governance.[137]

The declining country was repeatedly raided on its frontiers. Finally, Ghilzai Pashtun chieftain named Mir Wais Khan began a rebellion in Kandahar and defeated the Safavid army under the Iranian Georgian governor over the region, Gurgin Khan. In 1722, Peter the Great of neighbouring Imperial Russia launched the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many of Iran's Caucasian territories, including Derbent, Shaki, Baku, but also Gilan, Mazandaran and Astrabad. In the midst of chaos, in the same year of 1722, an Afghan army led by Mir Wais' son Mahmud marched across eastern Iran, besieged and took Isfahan. Mahmud proclaimed himself 'Shah' of Persia. Meanwhile, Persia's imperial rivals, the Ottomans and the Russians, took advantage of the chaos in the country to seize more territory for themselves.[138] By these events, the Safavid dynasty had effectively ended. In 1724, conform the Treaty of Constantinople, the Ottomans and the Russians agreed to divide large portions of Iran, which they had conquered between themselves.[139]

Nader Shah and his successors

[edit]

Iran's territorial integrity was restored by a native Iranian Turkic Afshar warlord from Khorasan, Nader Shah. He defeated and banished the Afghans, defeated the Ottomans, reinstalled the Safavids on the throne, and negotiated Russian withdrawal from Iran's Caucasian territories, with the Treaty of Resht and Treaty of Ganja. By 1736, Nader had become so powerful he was able to depose the Safavids and have himself crowned shah. Nader was one of the last great conquerors of Asia and briefly presided over what was probably the most powerful military force in the world.[140] To financially support his wars against Iran's arch-rival, the Ottoman Empire, he fixed his sights on the weak but rich Mughal Empire to the east. In 1739, accompanied by his loyal Caucasian subjects including Erekle II,[141][142]: 55 he invaded Mughal India, defeated a numerically superior Mughal army in less than three hours, and completely sacked and looted Delhi, bringing back immense wealth to Iran. On his way back, he also conquered all the Uzbek khanates – except for Kokand – and made the Uzbeks his vassals. He also firmly re-established Iranian rule over the entire Caucasus, Bahrain, as well as large parts of Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Undefeated for years, his defeat in Dagestan, following guerrilla rebellions by the Lezgins and the assassination attempt on him near Mazandaran is often considered the turning point in Nader's impressive career. To his frustration, the Dagestanis resorted to guerrilla warfare, and Nader with his conventional army could make little headway against them.[143] At the Battle of Andalal and the Battle of Avaria, Nader's army was crushingly defeated and he lost half of his entire force, forcing him to flee for the mountains.[144][better source needed] Though Nader managed to take most of Dagestan during his campaign, the effective guerrilla warfare as deployed by the Lezgins, but also the Avars and Laks, made the Iranian re-conquest of the particular North Caucasian region this time a short lived one; several years later, Nader was forced to withdraw. Around the same time, an assassination attempt was made on him near, which accelerated his descent into paranoia and megalomania. He blinded his sons, whom he suspected of the assassination attempts, and showed increasing cruelty against his subjects and officers. In his later years, this eventually provoked multiple revolts and, ultimately, his assassination in 1747.[145]

Nader Shah's death was followed by a period of anarchy as rival army commanders fought for power. Nader's own family, the Afsharids, were soon reduced to holding on to a small domain in Khorasan. Many of the Caucasian territories broke away in various Caucasian khanates. Ottomans regained lost territories in Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Oman and the Uzbek khanates of Bukhara and Khiva regained independence. Ahmad Shah Durrani, one of Nader's officers, founded an independent state which eventually became modern Afghanistan. Erekle II and Teimuraz II, who in 1744 had been made the kings of Kakheti and Kartli respectively by Nader for their loyal service,[142]: 55 capitalized on the eruption of instability and declared de facto independence. Erekle II assumed control over Kartli after Teimuraz II's death, thus unifying the two as the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, becoming the first Georgian ruler in three centuries to preside over a politically unified eastern Georgia.[146] Due to the frantic turn of events in mainland Iran he would be able to remain de facto autonomous through the Zand period.[147] From his capital Shiraz, Karim Khan of the Zand dynasty ruled "an island of relative calm and peace in an otherwise bloody and destructive period,"[148] however the extent of Zand power was confined to contemporary Iran and parts of the Caucasus. Karim Khan's death in 1779 led to yet another civil war in which the Qajar dynasty eventually triumphed and became kings of Iran. During the civil war, Iran permanently lost Basra in 1779 to the Ottomans, which had been captured during the Ottoman–Persian War (1775–76),[149] and Bahrain to Al Khalifa family after Bani Utbah invasion in 1783.[citation needed]

Late modern period

[edit]Qajar dynasty (1796–1925)

[edit]-

Qajar era currency bill with depiction of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar.

-

A map of Iran under the Qajar dynasty in the 19th century.

-

A map showing the 19th-century northwestern borders of Iran, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and the Republic of Azerbaijan, before being ceded to the neighboring Russian Empire by the Russo-Iranian wars.

Agha Mohammad Khan emerged victorious out of the civil war that commenced with the death of the last Zand king. His reign is noted for the reemergence of a centrally led and united Iran. After the death of Nader Shah and the last of the Zands, most of Iran's Caucasian territories had broken away into various Caucasian khanates. Agha Mohammad Khan, like the Safavid kings and Nader Shah before him, viewed the region as no different from the territories in mainland Iran. Therefore, his first objective after having secured mainland Iran, was to reincorpate the Caucasus region into Iran.[150] Georgia was seen as one of the most integral territories.[147] For Agha Mohammad Khan, the resubjugation and reintegration of Georgia into the Iranian Empire was part of the same process that had brought Shiraz, Isfahan, and Tabriz under his rule.[147] As the Cambridge History of Iran states, its permanent secession was inconceivable and had to be resisted in the same way as one would resist an attempt at the separation of Fars or Gilan.[147] It was therefore natural for Agha Mohammad Khan to perform whatever necessary means in the Caucasus in order to subdue and reincorporate the recently lost regions following Nader Shah's death and the demise of the Zands, including putting down what in Iranian eyes was seen as treason on the part Erekle II.[147]

Agha Mohammad Khan subsequently demanded that Erekle renounce its 1783 treaty with Russia, and to submit again to Iranian suzerainty,[150] in return for peace and the security of his kingdom. The Ottomans, Iran's neighboring rival, recognized the latter's rights over Kartli and Kakheti for the first time in four centuries.[151] Heraclius appealed then to his theoretical protector, Empress Catherine II of Russia, pleading for at least 3,000 Russian troops,[151] but he was ignored, leaving Georgia to fend off the Persian threat alone.[152] Nevertheless, Heraclius II still rejected the Khan's ultimatum.[153] As a response, Agha Mohammad Khan invaded the Caucasus region after crossing the Aras river, and, while on his way to Georgia, he re-subjugated Iran's territories of the Erivan Khanate, Shirvan, Nakhchivan Khanate, Ganja khanate, Derbent Khanate, Baku khanate, Talysh Khanate, Shaki Khanate, Karabakh Khanate, which comprise modern-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, Dagestan, and Igdir. Having reached Georgia with his large army, he prevailed in the Battle of Krtsanisi, which resulted in the capture and sack of Tbilisi, as well as the effective resubjugation of Georgia.[154][155] Upon his return from his successful campaign in Tbilisi and in effective control over Georgia, together with some 15,000 Georgian captives that were moved back to mainland Iran,[152] Agha Mohammad was formally crowned Shah in 1796 in the Mughan plain, just as his predecessor Nader Shah was about sixty years earlier. Agha Mohammad Shah was later assassinated in 1797 while preparing a second expedition against Georgia in Shusha[156] (now part of the Republic of Azerbaijan) and its King Heraclius II.

The reassertion of Iranian hegemony over Georgia did not last long; in 1799 the Russians marched into Tbilisi.[157] The Russians were already actively occupied with an expansionist policy towards its neighboring empires to its south, namely the Ottoman Empire and the successive Iranian kingdoms, since the late 17th/early 18th century. The next two years following Russia's entrance into Tbilisi were a time of confusion, and the weakened and devastated Georgian kingdom, with its capital half in ruins, was easily absorbed by Russia in 1801.[152][153] As Iran could not permit or allow the cession of Transcaucasia and Dagestan, which had been an integral part of Iran for centuries,[158] this would lead directly to the wars of several years later, namely the Russo-Persian Wars of 1804-1813 and 1826–1828. The outcome of these two wars (in the Treaty of Gulistan and the Treaty of Turkmenchay, respectively) proved for the irrevocable forced cession and loss of what is now eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan to Imperial Russia.[159][154]

The area to the north of the river Aras, among which the territory of the contemporary republic of Azerbaijan, eastern Georgia, Dagestan, and Armenia were Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[160]

-

Painting showing the Battle of Sultanabad, 13 February 1812. State Hermitage Museum.

-

Storming of Lankaran, 1812. Painted by Franz Roubaud.

-

Battle of Elisabethpol (Ganja), 1828. Franz Roubaud. Part of the collection of the Museum for History, Baku.

Migration of Caucasian Muslims

[edit]

Following the official loss of vast territories in the Caucasus, major demographic shifts were bound to take place. Following the 1804–1814 war, but also per the 1826–1828 war which ceded the last territories, large migrations of so-called Caucasian Muhajirs set off for mainland Iran. Some of these groups included the Ayrums, Qarapapaqs, Circassians, Shia Lezgins, and other Transcaucasian Muslims.[161]

After the Battle of Ganja of 1804, many thousands of Ayrums and Qarapapaqs were settled in Tabriz. During the remaining part of the 1804–1813 war, as well as through the 1826–1828 war, a large number of the Ayrums and Qarapapaqs that were still remaining in newly conquered Russian territories were settled in and migrated to Solduz (in modern-day Iran's West Azerbaijan province).[162] As the Cambridge History of Iran states; "The steady encroachment of Russian troops along the frontier in the Caucasus, General Yermolov's brutal punitive expeditions and misgovernment, drove large numbers of Muslims, and even some Georgian Christians, into exile in Iran."[163]

From 1864 until the early 20th century, another mass expulsion took place of Caucasian Muslims as a result of the Russian victory in the Caucasian War. Others simply voluntarily refused to live under Christian Russian rule, and thus departed for Turkey or Iran. These migrations once again, towards Iran, included masses of Caucasian Azerbaijanis, other Transcaucasian Muslims, as well as many North Caucasian Muslims, such as Circassians, Shia Lezgins and Laks.[161][164] Many of these migrants would prove to play a pivotal role in further Iranian history, as they formed most of the ranks of the Persian Cossack Brigade, which was established in the late 19th century.[165] The initial ranks of the brigade would be entirely composed of Circassians and other Caucasian Muhajirs.[165] This brigade would prove decisive in the following decades in Qajar history.

Furthermore, the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay included the official rights for the Russian Empire to encourage settling of Armenians from Iran in the newly conquered Russian territories.[166][167] Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[168] At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns, the Timurid Renaissance flourished, and Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia.[168] After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians and Muslims in 1604–05,[169] their numbers dwindled even further.

At the time of the Russian invasion of Iran, some 80% of the population of Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[170] As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede Iranian Armenia (which also constituted the present-day Armenia), to the Russians.[171][172] After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[173] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[170] It would be only after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, that ethnic Armenians once again established a solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[174] Nevertheless, the city of Erivan retained a Muslim majority up to the twentieth century.[174] According to the traveller H. F. B. Lynch, the city of Erivan was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Tatars[a] i.e. Azeris and Persians) in the early 1890s.[177]

Fath Ali Shah's reign saw increased diplomatic contacts with the West and the beginning of intense European diplomatic rivalries over Iran. His grandson Mohammad Shah, who succeeded him in 1834, fell under the Russian influence and made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Herat. When Mohammad Shah died in 1848 the succession passed to his son Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, who proved to be the ablest and most successful of the Qajar sovereigns. He founded the first modern hospital in Iran.[178]

Constitutional Revolution and deposition

[edit]The Great Persian Famine of 1870–1871 is believed to have caused the death of two million people.[179]

A new era in the history of Iran dawned with the Persian Constitutional Revolution against the shah in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The shah managed to remain in power, granting a limited constitution in 1906 (making the country a constitutional monarchy). The first Majlis (parliament) was convened on 7 October 1906. The discovery of petroleum in 1908 by the British in Khuzestan spawned intense renewed interest in Persia by the British Empire (see William Knox D'Arcy and Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, now BP). Britain's influence was solidified by the establishment of the Indo-European Telegraph Department in the 1860s and the Imperial Bank of Persia in 1889.[180] By the end of the 19th century, European interference became so pronounced that Iran's central government required Anglo-Russian approval for ministerial appointments.[181] Control of Persia remained contested between the United Kingdom and Russia, in what became known as The Great Game, and codified in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which divided Iran into spheres of influence, regardless of her national sovereignty.

During World War I, the country was occupied by British, Ottoman and Russian forces but was essentially neutral (see Persian Campaign). In 1919, after the Russian Revolution and their withdrawal, Britain attempted to establish a protectorate in Iran, which was unsuccessful. The Constitutionalist movement of Gilan and the central power vacuum caused by the instability of the Qajar government resulted in the rise of Reza Khan, later Reza Shah Pahlavi, who established the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925. In 1921, Reza Khan, an officer of the Persian Cossack Brigade, (along with Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabai) led a military led a coup against governing officials (leaving the Qajar monarchy nominally head of state).[182] In 1925, after being prime minister for two years, Reza Khan did depose the Qajar dynasty and became the first shah of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Pahlavi era (1925–1979)

[edit]Reza Shah (1925–1941)

[edit]Reza Shah ruled for almost 16 years until 16 September 1941, when he was forced to abdicate by the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. He established an authoritarian government that valued nationalism, militarism, secularism and anti-communism combined with strict censorship and state propaganda.[183] Reza Shah introduced many socio-economic reforms, reorganizing the army, government administration, and finances.[184] To his supporters, his reign brought "law and order, discipline, central authority, and modern amenities – schools, trains, buses, radios, cinemas, and telephones".[185] However, his attempts of modernisation have been criticised for being "too fast"[186] and "superficial",[187] and his reign a time of "oppression, corruption, taxation, lack of authenticity" with "security typical of police states."[185]

Many of the new laws and regulations created resentment among devout Muslims and the clergy. For example, mosques were required to use chairs; most men were required to wear western clothing, including a hat with a brim; women were encouraged to discard the hijab—hijab was eventually banned in 1936; men and women were allowed to congregate freely, violating Islamic mixing of the sexes. Tensions boiled over in 1935, when bazaaris and villagers rose up in rebellion at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad to protest against plans for the hijab ban, chanting slogans such as 'The Shah is a new Yezid.' Dozens were killed and hundreds were injured when troops finally quelled the unrest.[188]

World War II

[edit]While German armies were highly successful against the Soviet Union, the Iranian government expected Germany to win the war and establish a powerful force on its borders. It rejected British and Soviet demands to expel German residents from Iran. In response, the two Allies invaded in August 1941 and easily overwhelmed the weak Iranian army in Operation Countenance. Iran became the major conduit of Allied Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union. The purpose was to secure Iranian oil fields and ensure Allied supply lines (see Persian Corridor). Iran remained officially neutral. Its monarch Rezā Shāh was deposed during the subsequent occupation and replaced with his young son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[189]

At the Tehran Conference of 1943, the Allies issued the Tehran Declaration which guaranteed the post-war independence and boundaries of Iran. However, when the war actually ended, Soviet troops stationed in northwestern Iran not only refused to withdraw but backed revolts that established short-lived, pro-Soviet separatist national states in the northern regions of Azerbaijan and Iranian Kurdistan, the Azerbaijan People's Government and the Republic of Kurdistan respectively, in late 1945. Soviet troops did not withdraw from Iran proper until May 1946 after receiving a promise of oil concessions. The Soviet republics in the north were soon overthrown and the oil concessions were revoked.[190][191]

Mohammad-Reza Shah (1941–1979)

[edit]

Initially there were hopes that post-occupation Iran could become a constitutional monarchy. The new, young Shah Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi initially took a very hands-off role in government, and allowed parliament to hold a lot of power. Some elections were held in the first shaky years, although they remained mired in corruption. Parliament became chronically unstable, and from the 1947 to 1951 period Iran saw the rise and fall of six different prime ministers. Pahlavi increased his political power by convening the Iran Constituent Assembly, 1949, which finally formed the Senate of Iran—a legislative upper house allowed for in the 1906 constitution but never brought into being. The new senators were largely supportive of Pahlavi, as he had intended.

In 1951 Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq received the vote required from the parliament to nationalize the British-owned oil industry, in a situation known as the Abadan Crisis. Despite British pressure, including an economic blockade, the nationalization continued. Mosaddeq was briefly removed from power in 1952 but was quickly re-appointed by the Shah, due to a popular uprising in support of the premier, and he, in turn, forced the Shah into a brief exile in August 1953 after a failed military coup by Imperial Guard Colonel Nematollah Nassiri.

1953: U.S. aided coup removes Mosaddeq