Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Science in the medieval Islamic world

View on Wikipedia

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids and the Buyids in Persia and beyond, spanning the period roughly between 786 and 1258. Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. Other subjects of scientific inquiry included alchemy and chemistry, botany and agronomy, geography and cartography, ophthalmology, pharmacology, physics, and zoology.

Medieval Islamic science had practical purposes as well as the goal of understanding. For example, astronomy was useful for determining the Qibla, the direction in which to pray, botany had practical application in agriculture, as in the works of Ibn Bassal and Ibn al-'Awwam, and geography enabled Abu Zayd al-Balkhi to make accurate maps. Islamic mathematicians such as Al-Khwarizmi, Avicenna and Jamshīd al-Kāshī made advances in algebra, trigonometry, geometry and Arabic numerals. Islamic doctors described diseases like smallpox and measles, and challenged classical Greek medical theory. Al-Biruni, Avicenna and others described the preparation of hundreds of drugs made from medicinal plants and chemical compounds. Islamic physicists such as Ibn Al-Haytham, Al-Bīrūnī and others studied optics and mechanics as well as astronomy, and criticised Aristotle's view of motion.

During the Middle Ages, Islamic science flourished across a wide area around the Mediterranean Sea and further afield, for several centuries, in a wide range of institutions.

Context and history

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

The Islamic era began in 622. Islamic armies eventually conquered Arabia, Egypt and Mesopotamia, and successfully displaced the Persian and Byzantine Empires from the region within a few decades. Within a century, Islam had reached the area of present-day Portugal in the west and Central Asia in the east. The Islamic Golden Age (roughly between 786 and 1258) spanned the period of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), with stable political structures and flourishing trade. Major religious and cultural works of the Islamic empire were translated into Arabic and occasionally Persian. Islamic culture inherited Greek, Indic, Assyrian and Persian influences. A new common civilisation formed, based on Islam. An era of high culture and innovation ensued, with rapid growth in population and cities. The Arab Agricultural Revolution in the countryside brought more crops and improved agricultural technology, especially irrigation. This supported the larger population and enabled culture to flourish.[1][2] From the 9th century onwards, scholars such as Al-Kindi[3] translated Indian, Assyrian, Sasanian (Persian) and Greek knowledge, including the works of Aristotle, into Arabic. These translations supported advances by scientists across the Islamic world.[4]

Islamic science survived the initial Christian reconquest of Spain, including the fall of Seville in 1248, as work continued in the eastern centres (such as in Persia). After the completion of the Spanish reconquest in 1492, the Islamic world went into an economic and cultural decline.[2] The Abbasid caliphate was followed by the Ottoman Empire (c. 1299–1922), centred in Turkey, and the Safavid Empire (1501–1736), centred in Persia, where work in the arts and sciences continued.[5]

Fields of inquiry

[edit]Medieval Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.[4] Other subjects of scientific inquiry included physics, alchemy and chemistry, ophthalmology, and geography and cartography.[6][a]

Alchemy and chemistry

[edit]The early Islamic period saw the development of theoretical frameworks in alchemy and chemistry, laying the foundation for later advancements in both fields. The sulfur-mercury theory of metals, first found in Sirr al-khalīqa ("The Secret of Creation", c. 750–850, falsely attributed to Apollonius of Tyana), and in the writings attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (written c. 850–950),[7] remained the basis of theories of metallic composition until the 18th century.[8] The Emerald Tablet, a cryptic text that all later alchemists up to and including Isaac Newton saw as the foundation of their art, first occurs in the Sirr al-khalīqa and in one of the works attributed to Jabir.[9] In practical chemistry, the works of Jabir, and those of the Persian alchemist and physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925), contain the earliest systematic classifications of chemical substances.[10] Alchemists were also interested in artificially creating such substances.[11] Jabir describes the synthesis of ammonium chloride (sal ammoniac) from organic substances,[7] and Abu Bakr al-Razi experimented with the heating of ammonium chloride, vitriol, and other salts, which would eventually lead to the discovery of the mineral acids by 13th-century Latin alchemists such as pseudo-Geber.[10]

Astronomy and cosmology

[edit]

Astronomy became a major discipline within Islamic science. Astronomers devoted effort both towards understanding the nature of the cosmos and to practical purposes. One application involved determining the Qibla, the direction to face during prayer. Another was astrology, predicting events affecting human life and selecting suitable times for actions such as going to war or founding a city.[12] Al-Battani (850–922) accurately determined the length of the solar year. He contributed to the Tables of Toledo, used by astronomers to predict the movements of the sun, moon and planets across the sky. Copernicus (1473–1543) later used some of Al-Battani's astronomic tables.[13]

Al-Zarqali (1028–1087) developed a more accurate astrolabe, used for centuries afterwards. He constructed a water clock in Toledo, discovered that the Sun's apogee moves slowly relative to the fixed stars, and obtained a good estimate of its motion[14] for its rate of change.[15] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) wrote an important revision to Ptolemy's 2nd-century celestial model. When Tusi became Helagu's astrologer, he was given an observatory and gained access to Chinese techniques and observations. He developed trigonometry as a separate field, and compiled the most accurate astronomical tables available up to that time.[16]

Botany and agronomy

[edit]

The study of the natural world extended to a detailed examination of plants. The work done proved directly useful in the unprecedented growth of pharmacology across the Islamic world.[17] Al-Dinawari (815–896) popularised botany in the Islamic world with his six-volume Kitab al-Nabat (Book of Plants). Only volumes 3 and 5 have survived, with part of volume 6 reconstructed from quoted passages. The surviving text describes 637 plants in alphabetical order from the letters sin to ya, so the whole book must have covered several thousand kinds of plants. Al-Dinawari described the phases of plant growth and the production of flowers and fruit. The thirteenth century encyclopedia compiled by Zakariya al-Qazwini (1203–1283) – ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt (The Wonders of Creation) – contained, among many other topics, both realistic botany and fantastic accounts. For example, he described trees which grew birds on their twigs in place of leaves, but which could only be found in the far-distant British Isles.[18][17][19] The use and cultivation of plants was documented in the 11th century by Muhammad bin Ibrāhīm Ibn Bassāl of Toledo in his book Dīwān al-filāha (The Court of Agriculture), and by Ibn al-'Awwam al-Ishbīlī (also called Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī) of Seville in his 12th century book Kitāb al-Filāha (Treatise on Agriculture). Ibn Bassāl had travelled widely across the Islamic world, returning with a detailed knowledge of agronomy that fed into the Arab Agricultural Revolution. His practical and systematic book describes over 180 plants and how to propagate and care for them. It covered leaf- and root-vegetables, herbs, spices and trees.[20]

Geography and cartography

[edit]

The spread of Islam across Western Asia and North Africa encouraged an unprecedented growth in trade and travel by land and sea as far away as Southeast Asia, China, much of Africa, Scandinavia and even Iceland. Geographers worked to compile increasingly accurate maps of the known world, starting from many existing but fragmentary sources.[21] Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (850–934), founder of the Balkhī school of cartography in Baghdad, wrote an atlas called Figures of the Regions (Suwar al-aqalim).[22] Al-Biruni (973–1048) measured the radius of the Earth using a new method. It involved observing the height of a mountain at Nandana (now in Pakistan).[23] Al-Idrisi (1100–1166) drew a map of the world for Roger, the Norman King of Sicily (ruled 1105–1154). He also wrote the Tabula Rogeriana (Book of Roger), a geographic study of the peoples, climates, resources and industries of the whole of the world known at that time.[24] The Ottoman admiral Piri Reis (c. 1470–1553) made a map of the New World and West Africa in 1513. He made use of maps from Greece, Portugal, Muslim sources, and perhaps one made by Christopher Columbus. He represented a part of a major tradition of Ottoman cartography.[25]

-

Modern copy of al-Idrisi's 1154 Tabula Rogeriana, upside-down, north at top

Mathematics

[edit]

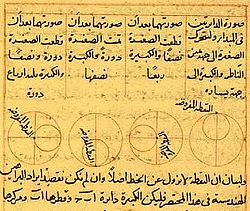

Islamic mathematicians gathered, organised and clarified the mathematics they inherited from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia and Persia, and went on to make innovations of their own. Islamic mathematics covered algebra, geometry and arithmetic. Algebra was mainly used for recreation: it had few practical applications at that time. Geometry was studied at different levels. Some texts contain practical geometrical rules for surveying and for measuring figures. Theoretical geometry was a necessary prerequisite for understanding astronomy and optics, and it required years of concentrated work. Early in the Abbasid caliphate (founded 750), soon after the foundation of Baghdad in 762, some mathematical knowledge was assimilated by al-Mansur's group of scientists from the pre-Islamic Persian tradition in astronomy. Astronomers from India were invited to the court of the caliph in the late eighth century; they explained the rudimentary trigonometrical techniques used in Indian astronomy. Ancient Greek works such as Ptolemy's Almagest and Euclid's Elements were translated into Arabic. By the second half of the ninth century, Islamic mathematicians were already making contributions to the most sophisticated parts of Greek geometry. Islamic mathematics reached its apogee in the Eastern part of the Islamic world between the tenth and twelfth centuries. Most medieval Islamic mathematicians wrote in Arabic, others in Persian.[26][27][28]

Al-Khwarizmi (8th–9th centuries) was instrumental in the adoption of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system and the development of algebra, introduced methods of simplifying equations, and used Euclidean geometry in his proofs.[29][30] He was the first to treat algebra as an independent discipline in its own right,[31] and presented the first systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations.[32]: 14 Ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (801–873) worked on cryptography for the Abbasid Caliphate,[33] and gave the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis and the first description of the method of frequency analysis.[34][35] Avicenna (c. 980–1037) contributed to mathematical techniques such as casting out nines.[36] Thābit ibn Qurra (835–901) calculated the solution to a chessboard problem involving an exponential series.[37] Al-Farabi (c. 870–950) attempted to describe, geometrically, the repeating patterns popular in Islamic decorative motifs in his book Spiritual Crafts and Natural Secrets in the Details of Geometrical Figures.[38] Omar Khayyam (1048–1131), known in the West as a poet, calculated the length of the year to within 5 decimal places, and found geometric solutions to all 13 forms of cubic equations, developing some quadratic equations still in use.[39] Jamshīd al-Kāshī (c. 1380–1429) is credited with several theorems of trigonometry, including the law of cosines, also known as Al-Kashi's Theorem. He has been credited with the invention of decimal fractions, and with a method like Horner's to calculate roots. He calculated π correctly to 17 significant figures.[40]

Sometime around the seventh century, Islamic scholars adopted the Hindu–Arabic numeral system, describing their use in a standard type of text fī l-ḥisāb al hindī, (On the numbers of the Indians). A distinctive Western Arabic variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals began to emerge around the 10th century in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus (sometimes called ghubar numerals, though the term is not always accepted), which are the direct ancestor of the modern Arabic numerals used throughout the world.[41]

Medicine

[edit]

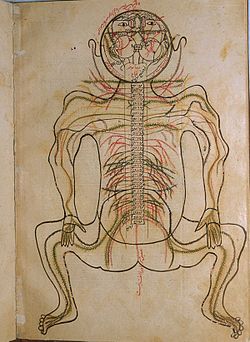

Islamic society paid careful attention to medicine, following a hadith enjoining the preservation of good health. Its physicians inherited knowledge and traditional medical beliefs from the civilisations of classical Greece, Rome, Syria, Persia and India. These included the writings of Hippocrates such as on the theory of the four humours, and the theories of Galen.[42] al-Razi (c. 865–925) identified smallpox and measles, and recognized fever as a part of the body's defenses. He wrote a 23-volume compendium of Chinese, Indian, Persian, Syriac and Greek medicine. al-Razi questioned the classical Greek medical theory of how the four humours regulate life processes. He challenged Galen's work on several fronts, including the treatment of bloodletting, arguing that it was effective.[43] al-Zahrawi (936–1013) was a surgeon whose most important surviving work is referred to as al-Tasrif (Medical Knowledge). It is a 30-volume set mainly discussing medical symptoms, treatments, and pharmacology. The last volume, on surgery, describes surgical instruments, supplies, and pioneering procedures.[44] Avicenna (c. 980–1037) wrote the major medical textbook, The Canon of Medicine.[36] Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) wrote an influential book on medicine; it largely replaced Avicenna's Canon in the Islamic world. He wrote commentaries on Galen and on Avicenna's works. One of these commentaries, discovered in 1924, described the circulation of blood through the lungs.[45][46]

Optics and ophthalmology

[edit]

Optics developed rapidly in this period. By the ninth century, there were works on physiological, geometrical and physical optics. Topics covered included mirror reflection. Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) wrote the book Ten Treatises on the Eye; this remained influential in the West until the 17th century.[49] Abbas ibn Firnas (810–887) developed lenses for magnification and the improvement of vision.[50] Ibn Sahl (c. 940–1000) discovered the law of refraction known as Snell's law. He used the law to produce the first Aspheric lenses that focused light without geometric aberrations.[51][52]

In the eleventh century Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1040) rejected the Greek ideas about vision, whether the Aristotelian tradition that held that the form of the perceived object entered the eye (but not its matter), or that of Euclid and Ptolemy which held that the eye emitted a ray. Al-Haytham proposed in his Book of Optics that vision occurs by way of light rays forming a cone with its vertex at the center of the eye. He suggested that light was reflected from different surfaces in different directions, thus causing objects to look different.[53][54][55][56] He argued further that the mathematics of reflection and refraction needed to be consistent with the anatomy of the eye.[57] He was also an early proponent of the scientific method, the concept that a hypothesis must be proved by experiments based on confirmable procedures or mathematical evidence, five centuries before Renaissance scientists.[58][59][60][61][62][63]

Pharmacology

[edit]

Advances in botany and chemistry in the Islamic world encouraged developments in pharmacology. Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) (865–915) promoted the medical uses of chemical compounds. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis) (936–1013) pioneered the preparation of medicines by sublimation and distillation. His Liber servitoris provides instructions for preparing "simples" from which were compounded the complex drugs then used. Sabur Ibn Sahl (died 869) was the first physician to describe a large variety of drugs and remedies for ailments. Al-Muwaffaq, in the 10th century, wrote The foundations of the true properties of Remedies, describing chemicals such as arsenious oxide and silicic acid. He distinguished between sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate, and drew attention to the poisonous nature of copper compounds, especially copper vitriol, and also of lead compounds. Al-Biruni (973–1050) wrote the Kitab al-Saydalah (The Book of Drugs), describing in detail the properties of drugs, the role of pharmacy and the duties of the pharmacist. Ibn Sina (Avicenna) described 700 preparations, their properties, their mode of action and their indications. He devoted a whole volume to simples in The Canon of Medicine. Works by Masawaih al-Mardini (c. 925–1015) and by Ibn al-Wafid (1008–1074) were printed in Latin more than fifty times, appearing as De Medicinis universalibus et particularibus by Mesue the Younger (died 1015) and as the Medicamentis simplicibus by Abenguefit (c. 997 – 1074) respectively. Peter of Abano (1250–1316) translated and added a supplement to the work of al-Mardini under the title De Veneris. Ibn al-Baytar (1197–1248), in his Al-Jami fi al-Tibb, described a thousand simples and drugs based directly on Mediterranean plants collected along the entire coast between Syria and Spain, for the first time exceeding the coverage provided by Dioscorides in classical times.[64][17] Islamic physicians such as Ibn Sina described clinical trials for determining the efficacy of medical drugs and substances.[65]

Physics

[edit]

The fields of physics studied in this period, apart from optics and astronomy which are described separately, are aspects of mechanics: statics, dynamics, kinematics and motion. In the sixth century John Philoponus (c. 490 – c. 570) rejected the Aristotelian view of motion. He argued instead that an object acquires an inclination to move when it has a motive power impressed on it. In the eleventh century Ibn Sina adopted roughly the same idea, namely that a moving object has force which is dissipated by external agents like air resistance.[66] Ibn Sina distinguished between "force" and "inclination" (mayl); he claimed that an object gained mayl when the object is in opposition to its natural motion. He concluded that continuation of motion depends on the inclination that is transferred to the object, and that the object remains in motion until the mayl is spent. He also claimed that a projectile in a vacuum would not stop unless it is acted upon. That view accords with Newton's first law of motion, on inertia.[67] As a non-Aristotelian suggestion, it was essentially abandoned until it was described as "impetus" by Jean Buridan (c. 1295–1363), who was likely influenced by Ibn Sina's Book of Healing.[66]

In the Shadows, Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) describes non-uniform motion as the result of acceleration.[68] Ibn-Sina's theory of mayl tried to relate the velocity and weight of a moving object, a precursor of the concept of momentum.[69] Aristotle's theory of motion stated that a constant force produces a uniform motion; Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī (c. 1080 – 1164/5) disagreed, arguing that velocity and acceleration are two different things, and that force is proportional to acceleration, not to velocity.[70]

The Banu Musa brothers, Jafar-Muhammad, Ahmad and al-Hasan (c. early 9th century) invented automated devices described in their Book of Ingenious Devices.[71][72][73] Advances on the subject were also made by al-Jazari and Ibn Ma'ruf.

Zoology

[edit]

Many classical works, including those of Aristotle, were transmitted from Greek to Syriac, then to Arabic, then to Latin in the Middle Ages. Aristotle's zoology remained dominant in its field for two thousand years.[74] The Kitāb al-Hayawān (كتاب الحيوان, English: Book of Animals) is a 9th-century Arabic translation of History of Animals: 1–10, On the Parts of Animals: 11–14,[75] and Generation of Animals: 15–19.[76][77]

The book was mentioned by Al-Kindī (died 850), and commented on by Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā) in his The Book of Healing. Avempace (Ibn Bājja) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd) commented on and criticised On the Parts of Animals and Generation of Animals.[78]

Significance

[edit]Muslim scientists helped in laying the foundations for an experimental science with their contributions to the scientific method and their empirical, experimental and quantitative approach to scientific inquiry.[79] In a more general sense, the positive achievement of Islamic science was simply to flourish, for centuries, in a wide range of institutions from observatories to libraries, madrasas to hospitals and courts, both at the height of the Islamic golden age and for some centuries afterwards. It did not lead to a Scientific Revolution like that in Early modern Europe, but such external comparisons are probably to be rejected as imposing "chronologically and culturally alien standards" on a successful medieval culture.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hodgson, Marshall (1974). The Venture of Islam; Conscience and History in a World Civilisation Vol 1. University of Chicago. pp. 233–238. ISBN 978-0-226-34683-0.

- ^ a b c McClellan and Dorn 2006, pp.103–115

- ^ "Al-Kindi". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b Robinson, Francis, ed. (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 228–229.

- ^ Turner 1997, p.7

- ^ Turner 1997, Table of contents

- ^ a b Kraus, Paul (1942–1943). Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. ISBN 978-3-487-09115-0. OCLC 468740510.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) vol. II, p. 1, note 1; Weisser, Ursula (1980). Spies, Otto (ed.). Das "Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung" von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 199. doi:10.1515/9783110866933. ISBN 978-3-11-007333-1. - ^ Norris, John (2006). "The Mineral Exhalation Theory of Metallogenesis in Pre-Modern Mineral Science". Ambix. 53 (1): 43–65. doi:10.1179/174582306X93183. S2CID 97109455.

- ^ Weisser, Ursula (1980). Spies, Otto (ed.). Das "Buch über das Geheimnis der Schöpfung" von Pseudo-Apollonios von Tyana. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110866933. ISBN 978-3-11-007333-1. p. 46. On Newton's alchemy, see Newman, William R. (2019). Newton the Alchemist: Science, Enigma, and the Quest for Nature's Secret Fire. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17487-7.

- ^ a b Karpenko, Vladimír; Norris, John A. (2002). "Vitriol in the History of Chemistry". Chemické listy. 96 (12): 997–1005.

- ^ See Newman, William R. (2004). Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-57524-7.

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.59–116

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.74, 148–150

- ^ Linton (2004), p.97). Owing to the unreliability of the data al-Zarqali relied on for this estimate, its remarkable accuracy was fortuitous.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.73–75

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.132–135

- ^ a b c Turner 1997, pp.138–139

- ^ Fahd, Toufic, Botany and agriculture, p. 815, in Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp.813–852

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.162–188

- ^ "Ibn Baṣṣāl: Dīwān al-filāḥa / Kitāb al-qaṣd wa'l-bayān". The Filaha Texts Project: The Arabic Books of Husbandry. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.117–130

- ^ Edson, E.; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2004). Medieval Views of the Cosmos. Bodleian Library. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-1-851-24184-2.

- ^ Pingree, David (March 1997). "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iv. Geography". Encyclopædia Iranica. Columbia University. ISBN 978-1-56859-050-9.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.79–80

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.128–129

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (January 2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization, Volume 1: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 484–485. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.43–61

- ^ Hogendijk, Jan P.; Berggren, J. L. (1989). "Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam by J. Lennart Berggren". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 109 (4): 697–698. doi:10.2307/604119. JSTOR 604119.

- ^ Toomer, Gerald (1990). "Al-Khwārizmī, Abu Jaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā". In Gillispie, Charles Coulston. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 7. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-684-16962-0.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.139–145

- ^ Gandz, S. (1936), "The Sources of Al-Khowārizmī's Algebra", Osiris, 1: 263–277, doi:10.1086/368426, S2CID 60770737, page 263–277: "In a sense, al-Khwarizmi is more entitled to be called "the father of algebra" than Diophantus because al-Khwarizmi is the first to teach algebra in an elementary form and for its own sake, Diophantus is primarily concerned with the theory of numbers".

- ^ Maher, P. (1998). From Al-Jabr to Algebra. Mathematics in School, 27(4), 14–15.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.49–52

- ^ Broemeling, Lyle D. (1 November 2011). "An Account of Early Statistical Inference in Arab Cryptology". The American Statistician. 65 (4): 255–257. doi:10.1198/tas.2011.10191. S2CID 123537702.

- ^ Al-Kadi, Ibrahim A. (1992). "The origins of cryptology: The Arab contributions". Cryptologia. 16 (2): 97–126. doi:10.1080/0161-119291866801.

- ^ a b Masood 2009, pp.104–105

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.48–49

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.148–149

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.5, 104, 145–146

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid Mas'ud al-Kashi", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- ^ Kunitzsch, Paul (2003), "The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered", in J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.), The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives, MIT Press, pp. 3–22, ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.131–161

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.74, 99–105

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.108–109

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.110–111

- ^ Turner 1997, pp.131–139

- ^ Al-Khalili, Jim (4 January 2009). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News.

Ibn al-Haytham is regarded as the father of the modern scientific method.

- ^ Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa (2010). Mind, Brain, and Education Science: A Comprehensive Guide to the New Brain-Based Teaching. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-393-70607-9.

Alhazen (or Al-Haytham; 965–1039 CE) was perhaps one of the greatest physicists of all times and a product of the Islamic Golden Age or Islamic Renaissance (7th–13th centuries). He made significant contributions to anatomy, astronomy, engineering, mathematics, medicine, ophthalmology, philosophy, physics, psychology, and visual perception and is primarily attributed as the inventor of the scientific method, for which author Bradley Steffens (2006) describes him as the "first scientist".

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.47–48, 59, 96–97, 171–72

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.71–73

- ^ K. B. Wolf, "Geometry and dynamics in refracting systems", European Journal of Physics 16, p. 14–20, 1995.

- ^ R. Rashed, "A pioneer in anaclastics: Ibn Sahl on burning mirrors and lenses", Isis 81, p. 464–491, 1990

- ^ Dallal, Ahmad (2010). Islam, Science, and the Challenge of History. Yale University Press. pp. 38–39.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (1976). Theories of Vision from al-Kindi to Kepler. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-48234-7. OCLC 1676198.

- ^ El-Bizri, Nader (2005). A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen's Optics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–218.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ El-Bizri, Nader (30 March 2011). "Ibn al-Haytham". Muslim Heritage. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.173–175

- ^ Ackerman, James S. (August 1991), Distance Points: Essays in Theory and Renaissance Art and Architecture, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-01122-8

- ^ Haq, Syed (2009). "Science in Islam". Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISSN 1703-7603. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ G. J. Toomer. Review on JSTOR, Toomer's 1964 review of Matthias Schramm (1963) Ibn Al-Haythams Weg Zur Physik Toomer p.464: "Schramm sums up [Ibn Al-Haytham's] achievement in the development of scientific method."

- ^ "International Year of Light - Ibn Al-Haytham and the Legacy of Arabic Optics". Archived from the original on 2014-10-01. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ Al-Khalili, Jim (4 January 2009). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Gorini, Rosanna (October 2003). "Al-Haytham the man of experience. First steps in the science of vision" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine. 2 (4): 53–55. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ Levey, M. (1973). Early Arabic Pharmacology. E. J. Brill.

- ^ Meinert, Curtis L.; Tonascia, Susan (1986). Clinical trials: design, conduct, and analysis. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-503568-1.

- ^ a b Sayili, Aydin (1987). "Ibn Sina and Buridan on the Motion the Projectile". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 500 (1): 477–482. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37219.x. S2CID 84784804.

- ^ Espinoza, Fernando (2005). "An Analysis of the Historical Development of Ideas About Motion and its Implications for Teaching". Physics Education. 40 (2): 139–146. Bibcode:2005PhyEd..40..139E. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/40/2/002. S2CID 250809354.

- ^ "Biography of Al-Biruni". University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

- ^ Nasr, S. H.; Razavi, M. A. (1996). The Islamic Intellectual Tradition in Persia. Routledge.

- ^ Pines, Shlomo (1986). Studies in Arabic versions of Greek texts and in mediaeval science. Vol. 2. Brill Publishers. p. 203. ISBN 978-965-223-626-5.

- ^ Masood 2009, pp.161–163

- ^ Lindberg, David (1978). Science in the Middle Ages. University of Chicago Press. pp. 23, 56.

- ^ Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 151, 235, 375.

- ^ Hoffman, Eva R. (2013). Translating Image and Text in the Medieval Mediterranean World between the Tenth and Thirteenth Centuries. Brill. pp. 288–. ISBN 978-90-04-25034-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Kruk, R., 1979, The Arabic Version of Aristotle's Parts of Animals: book XI–XIV of the Kitab al-Hayawan, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam-Oxford 1979.

- ^ Contadini, Anna (2012). A World of Beasts: A Thirteenth-Century Illustrated Arabic Book on Animals (the Kitab Na't al-Hayawan) in the Ibn Bakhtishu' Tradition). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22265-6.

- ^ Kruk, R., 2003, "La zoologie aristotélicienne. Tradition arabe", DPhA Supplement, 329–334

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. pp. 354–355. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ Durant, Will (1980). The Age of Faith (The Story of Civilization, Volume 4), p. 162–186. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-01200-7. Garrison, Fielding H., An Introduction to the History of Medicine: with Medical Chronology, Suggestions for Study and Bibliographic Data, p. 86. Lewis, Bernard (2001). What Went Wrong? : Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-19-514420-8.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lindberg & Shank 2013, chapters 1–5 cover science, mathematics and medicine in Islam.

Sources

[edit]- Linton, Christopher M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82750-8.

- Masood, Ehsan (2009). Science and Islam: A History. Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-785-78202-2.

- McClellan, James E. III; Dorn, Harold, eds. (2006). Science and Technology in World History (2 ed.). Johns Hopkins. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6.

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 3. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2.

- Turner, Howard R. (1997). Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78149-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Al-Daffa, Ali Abdullah; Stroyls, J.J. (1984). Studies in the exact sciences in medieval Islam. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-90320-8.

- Hogendijk, Jan P.; Sabra, Abdelhamid I. (2003). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

- Hill, Donald Routledge (1993). Islamic Science And Engineering. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0455-5.

- Huff, Toby (1993). The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West. Cambridge University Press.

- Kennedy, Edward S. (1983). Studies in the Islamic Exact Sciences. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-6067-5.

- Lindberg, D. C.; Shank, M. H., eds. (2013). The Cambridge History of Science. Volume 2: Medieval Science. Cambridge University Press. (chapters 1–5 cover science, mathematics and medicine in Islam)

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 2–3. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-02063-3.

- Saliba, George (2007). Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19557-7.

External links

[edit]- "How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs" by De Lacy O'Leary

- Saliba, George. "Whose Science is Arabic Science in Renaissance Europe?".

- Habibi, Golareh. is there such a thing as Islamic science? the influence of Islam on the world of science, Science Creative Quarterly.