Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Israel Defense Forces

View on Wikipedia

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; Hebrew: צבא הגנה לישראל, romanized: ⓘ, lit. 'Army for the Defense of Israel'), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym Tzahal (צה״ל), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branches: the Israeli Ground Forces, the Israeli Air Force, and the Israeli Navy.[3] It is the sole military wing of the Israeli security apparatus. The IDF is headed by the chief of the general staff, who is subordinate to the defense minister.

On the orders of first prime minister David Ben-Gurion, the IDF was formed on 26 May 1948 and began to operate as a conscript military, drawing its initial recruits from the already existing paramilitaries of the Yishuv—namely Haganah, the Irgun, and Lehi. It was formed shortly after the Israeli Declaration of Independence and has participated in every armed conflict involving Israel. In the wake of the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty and the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty, the IDF underwent a significant strategic realignment. Previously spread across various fronts—Lebanon and Syria in the north, Jordan and Iraq in the east, and Egypt in the south—the IDF redirected its focus towards southern Lebanon and the Palestinian territories. In 2000, the IDF withdrew from Southern Lebanon and in 2005 from Gaza. Conflict between Israel and Islamist groups based in Gaza, notably Hamas, has continued since then. Moreover, notable Israeli–Syrian border incidents have occurred frequently since 2011, due to regional instability caused by the Syrian civil war.

Since 1967, the IDF has maintained a close security relationship with the United States,[4] including in research and development cooperation, with joint efforts on the F-15I and the Arrow defence system, among others. The IDF is believed to have maintained an operational nuclear weapons capability since 1967, possibly possessing between 80 and 400 nuclear warheads.[5] The IDF's actions and policies in the Palestinian territories have faced widespread criticism, with accusations of repression, institutionalized discrimination, unlawful killings and systematic abuses of Palestinian rights, with multiple human rights organizations and scholars accusing the IDF of genocide.[6][7][8]

Etymology

[edit]The Israeli cabinet ratified the name "Israel Defense Forces" (Hebrew: צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל), Tzva haHagana leYisra'el, literally "the army for the defence of Israel," on 26 May 1948. The other main contender was Tzva Yisra'el (Hebrew: צְבָא יִשְׂרָאֵל). The name was chosen because it conveyed the idea that the army's role was defence and incorporated the name Haganah, the pre-state defensive organization upon which the new army was based.[9] Among the primary opponents of the name were Minister Haim-Moshe Shapira and the Hatzohar party, both in favor of Tzva Yisra'el.[9]

In Israel's basic law about the military, the Hebrew name of the IDF is צבא הגנה לישראל, Tzva Hagana LeYisra'el, without a definite article on the second word.[10]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

The IDF traces its roots to Jewish paramilitary organizations in the New Yishuv, starting with the Second Aliyah (1904 to 1914).[11] There had been several such organizations, or in part even older date, such as the "Mahane Yehuda" mounted guards company founded by Michael Halperin in 1891[12] (see Ness Ziona), HaMagen (1915–17),[13] HaNoter[13] (1912–13; see Zionism: Pre-state self-defense), and the much more consequential (but falsely-claimed "first" such organization), Bar-Giora, founded in September 1907. Bar-Giora was transformed into Hashomer in April 1909, which operated until the British Mandate of Palestine came into being in 1920. Hashomer was an elitist organization with a narrow scope and was mainly created to protect against criminal gangs seeking to steal property. The Zion Mule Corps and the Jewish Legion, both part of the British Army of World War I, further bolstered the Yishuv with military experience and manpower, forming the basis for later paramilitary forces.[14]

After the 1920 Palestine riots against Jews in April 1920, the Yishuv leadership realized the need for a nationwide underground defence organization, and the Haganah was founded in June 1920.[14] The Haganah became a full-scale defence force after the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine with an organized structure, consisting of three main units—the Field Corps, Guard Corps, and the Palmach. During World War II, the Yishuv participated in the British war effort, culminating in the formation of the Jewish Brigade. These would eventually form the backbone of the Israel Defense Forces, and provide it with its initial manpower and doctrine.

Following Israel's Declaration of Independence, Prime Minister and Defense Minister David Ben-Gurion issued an order for the formation of the Israel Defense Forces on 26 May 1948. Although Ben-Gurion had no legal authority to issue such an order, the order was made legal by the cabinet on 31 May. The same order called for the disbandment of all other Jewish armed forces.[15] The two other Jewish underground organizations, Irgun and Lehi, agreed to join the IDF if they would be able to form independent units and agreed not to make independent arms purchases. This was the background for the Altalena Affair, a confrontation surrounding weapons purchased by the Irgun resulting in a standoff between Irgun members and the newly created IDF. The affair came to an end when Altalena, the ship carrying the arms, was shelled by the IDF. Following the affair, all independent Irgun and Lehi units were either disbanded or merged into the IDF. The Palmach, a leading component of the Haganah, also joined the IDF with provisions, and Ben Gurion responded by disbanding its staff in 1949, after which many senior Palmach officers retired, notably its first commander, Yitzhak Sadeh.

The new army organized itself when the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine escalated into the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, which saw neighbouring Arab states attack. Twelve infantry and armoured brigades formed: Golani, Carmeli, Alexandroni, Kiryati, Givati, Etzioni, the 7th, and 8th armoured brigades, Oded, Harel, Yiftach, and the Negev.[16] After the war, some of the brigades were converted to reserve units, and others were disbanded. Directorates and corps were created from corps and services in the Haganah, and this basic structure in the IDF still exists today.

Immediately after the 1948 war, the Israel-Palestinian conflict shifted to a low-intensity conflict between the IDF and Palestinian fedayeen. In the 1956 Suez Crisis, the IDF's first serious test of strength after 1949, the new army captured the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, which was later returned. In the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel conquered the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Golan Heights from the surrounding Arab states, changing the balance of power in the region as well as the role of the IDF. In the following years leading up to the Yom Kippur War, the IDF fought in the War of Attrition against Egypt in the Sinai and a border war against the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Jordan, culminating in the Battle of Karameh.

The surprise of the Yom Kippur War and its aftermath completely changed the IDF's procedures and approach to warfare. Organizational changes were made and more time was dedicated to training for conventional warfare. However, in the following years the army's role slowly shifted again to low-intensity conflict, urban warfare and counter-terrorism. An example of the latter was the successful 1976 Operation Entebbe commando raid to free hijacked airline passengers being held captive in Uganda. During this era, the IDF also mounted a successful bombing mission in Iraq to destroy its nuclear reactor. It was involved in the Lebanese Civil War, initiating Operation Litani and later the 1982 Lebanon War, where the IDF ousted Palestinian guerrilla organizations from Lebanon.

For twenty-five years the IDF maintained a security zone inside South Lebanon with their allies the South Lebanon Army. Palestinian militancy has been the main focus of the IDF ever since, especially during the First and Second Intifadas, Operation Defensive Shield, the Gaza War (2008–2009), the 2012 Gaza War, the 2014 Gaza War, and the 2021 Israel-Palestine crisis, causing the IDF to change many of its values and publish the IDF Code of Ethics. The Lebanese Shia organization Hezbollah has also been a growing threat,[17] against which the IDF fought an asymmetric conflict between 1982 and 2000, as well as a full-scale war in 2006.

The Israel Defense Forces have been accused of committing various war crimes since the founding of Israel in 1948. Israel ratified the Geneva Conventions on July 6, 1951,[18] and on January 2, 2015, the State of Palestine acceded to the Rome Statute, granting the International Criminal Court (ICC) jurisdiction over war crimes committed in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT).[19] A 2017 report by Human Rights Watch accused the IDF of unlawful killings, using excessive force in policing situations, forced displacement, excessive use of detention and excessive restrictions on movement, as well as criticized the IDF's support and protection for Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territory.[6] Human rights experts argue that actions taken by the IDF during armed conflicts in the OPT fall under the rubric of war crimes.[20] Various UN special rapporteurs, alongside human rights and aid organizations including Human Rights Watch, Médecins Sans Frontières, Amnesty International, have accused Israel of war crimes, and since 2024, genocide.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27]

Organization

[edit]

All branches of the IDF answer to a single General Staff. The Chief of the General Staff is the only serving officer having the rank of Lieutenant General (Rav Aluf). He reports directly to the Defense Minister and indirectly to the Prime Minister of Israel and the cabinet. Chiefs of Staff are formally appointed by the cabinet, based on the Defense Minister's recommendation, for three years. The government can vote to extend their service to four, and on rare occasions even five years. The current chief of staff is Eyal Zamir.[28]

Structure

[edit]The IDF includes the following bodies. Those whose respective heads are members of the General Staff are in bold:

Ranks, uniforms and insignia

[edit]Ranks

[edit]

Unlike most militaries, the IDF uses the same rank names in all corps, including the air force and navy.

From the formation of the IDF until the late 1980s, sergeant major was a particularly important warrant officer rank, in line with usage in other armies. In the 1980s and 1990s the proliferating ranks of sergeant major became devalued, and now all professional non-commissioned officer ranks are a variation on sergeant major (rav samal) except for rav nagad.

All translations here are the official translations of the IDF's website.[29]

Conscripts (Hogrim) (Conscript ranks may be gained purely on time served)

- Private (Turai)

- Corporal (Rav Turai) (also called rabat[30])

- Sergeant (Samal)

- First Sergeant (Samal Rishon)

Warrant Officers (Nagadim)

- Sergeant First Class (Rav Samal)

- Master Sergeant (Rav Samal Rishon)

- Sergeant Major (Rav Samal Mitkadem)

- Warrant Officer (Rav Samal Bakhir)

- Master Warrant Officer (Rav Nagad Mishneh)

- Chief Warrant Officer (Rav Nagad)

Academic officers (Ktzinim Akadema'im)

- Professional Academic Officer (Katzin Miktzo'i Akadema'i)

- Senior Academic Officer (Katzin Akadema'i Bakhir)

Officers (Ktzinim)

- Second Lieutenant (Segen Mishneh) [1951–Present]

- Lieutenant (Segen)

- Captain (Seren)

- Major (Rav Seren)

- Lieutenant Colonel (Sgan Aluf)

- Colonel (Aluf Mishneh) [1950–Present]

- Brigadier General (Tat Aluf) [1968–Present]

- Major General (Aluf) [1948–Present]

- Lieutenant General (Rav Aluf)

Uniforms

[edit]

The Israel Defense Forces has several types of uniforms:

- Service dress (מדי אלף Madei Alef – Uniform "A") – the everyday uniform, worn by everybody.

- Field dress (מדי ב Madei Bet – Uniform "B") – worn into combat, training, work on base.

The first two resemble each other but the Madei Alef is made of higher quality materials in a golden olive while the madei bet is in olive drab.[31][32] The dress uniforms may also exhibit a surface shine[32][33]

- Officers / Ceremonial dress (מדי שרד madei srad) – worn by officers, or during special events/ceremonies.

- Dress uniform and mess dress – worn only abroad. Several dress uniforms are depending on the season and the branch.

The service uniform for all ground forces personnel is olive green; navy and air force uniforms are beige/tan (also once worn by the ground forces). The uniforms consist of a two-pocket shirt, combat trousers, sweater, jacket or blouse, and shoes or boots. The navy also has an all-white dress uniform. The green fatigues are the same for winter and summer and heavy winter gear is issued as needed. Women's dress parallels the men's but may substitute a skirt for trousers and a blouse for a shirt.

Headgear included a service cap for dress and semi-dress and a field cap or "Kova raful" bush hat worn with fatigues. Many IDF personnel once wore the tembel as a field hat. IDF personnel generally wear berets instead of the service cap and there are many beret colours issued to IDF personnel. Paratroopers are issued a maroon beret, Golani brown, Givati purple, Nahal lime green, Kfir camouflage, Combat Engineers grey, navy blue for IDF Naval and dark grey for IDF Air Force personnel.

In combat uniforms, the Orlite helmet has replaced the British Brodie helmet Mark II/Mark III, RAC Mk II modified helmet with chin web jump harness (used by paratroopers and similar to the HSAT Mk II/Mk III paratrooper helmets),[34] US M1 helmet,[35] and French Modèle 1951 helmet – previously worn by Israeli infantry and airborne troops from the late 1940s to the mid-1970s and early 1980s.[36]

Some corps or units have small variations in their uniforms – for instance, military police wear a white belt and police hat, Naval personnel have dress whites for parades, paratroopers are issued a four pocket tunic (yarkit/yerkit) worn untucked with a pistol belt cinched tight around the waist over the shirt.[37] The IDF Air Corps has a dress uniform consisting of a pale blue shirt with dark blue trousers.

Most IDF soldiers are issued black leather combat boots, certain units issue reddish-brown leather boots for historical reasons — the paratroopers,[37] combat medics, Nahal and Kfir Brigades, as well as some Special Forces units (Sayeret Matkal, Oketz, Duvdevan, Maglan, and the Counter-Terror School). Women were also formerly issued sandals, but this practice has ceased.

Insignia

[edit]IDF soldiers have three types of insignia (other than rank insignia) which identify their corps, specific unit, and position. A pin attached to the beret identifies a soldier's corps. Individual units are identified by a shoulder tag attached to the left shoulder strap. The position/job of a soldier can then be identified by an aiguillette attached to the left shoulder strap and shirt pocket, and a pin indicating the soldier's work type.

Service

[edit]Military service routes

[edit]

The military service is held in three different tracks:

- Regular service (שירות חובה): mandatory military service which is held according to the Israeli security service law.

- Permanent service (שירות קבע): military service which is held as part of a contractual agreement between the IDF and the permanent position-holder.

- Reserve service (שירות מילואים): a military service in which citizens are called for active duty of at most a month every year (in accordance with the Reserve Service Law), for training and ongoing military activities and especially to increase the military forces in case of a war.

Sometimes the IDF would also hold pre-military courses (קורס קדם צבאי or קד"צ) for soon-to-be regular service soldiers.

Special service routes

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

- Shoher (שוחר), a person enrolled in pre-military studies (high school, technical college up to engineering degree, some of the קד"ץ courses) – after completing the twelfth study year will do a two-month boot-camp and, if allowed, enter a program of education to qualify as a practical engineer, with at least two weeks of training following each study year. Successful candidates will continue for an engineering bachelor degree.

- Civilian working for the IDF (Hebrew: אזרח עובד צה"ל), a civilian working for the military.

The Israeli Manpower Directorate (Hebrew: אגף משאבי אנוש) at the Israeli General Staff is the body which coordinates and assembles activities related to the control over human resources and its placement.

Regular service

[edit]

National military service is mandatory for all Israeli citizens over the age of 18, although Arab (but not Druze) citizens are exempted if they so please, and other exceptions may be made on religious, physical or psychological grounds (see Profile 21). The Tal law exempted ultra-Orthodox Jews from service. In June 2024, Israel's Supreme Court unanimously ruled that Haredi Jews were eligible for compulsory service, ending nearly eight decades of exemption.[38] The army began drafting Haredi men the following month.[39]

Until the draft of July 2015, men served three years in the IDF. Men drafted since July 2015 serve two years and eight months (32 months), with some roles requiring an additional four months of Permanent service. Women serve two years. The IDF women who volunteer for several combat positions often serve for three years, due to the longer period of training. Women in other positions, such as programmers, who also require lengthy training time, may also serve three years.

Many Religious Zionist men (and many Modern Orthodox who make Aliyah) elect to do Hesder, a five-year program envisioned by Rabbi Yehuda Amital which combines Torah learning and military service.[40]

Some distinguished soldiers are selected to be trained to eventually become members of special forces units. Every brigade in the IDF has its special force branch.

Career soldiers are paid on average NIS 23,000 a month. Conscripts are paid according to four tiers based on their positions. Frontline soldiers receive NIS 3,048 a month, other combat soldiers receive NIS 2,463, combat support soldiers receive NIS 1,793, and administrative soldiers receive NIS 1,235.[41][42]

In 1998–2000, only about 9% of those who refused to serve in the Israeli military were granted an exemption.[43]

Permanent service

[edit]Permanent service is designed for soldiers who choose to continue serving in the army after their regular service, for a short or long period, and in many cases making the military their career. Permanent service is based on a contractual agreement between the IDF and the permanent position holder.

Reserve service

[edit]After personnel complete their regular service, they are either granted permanent exemption from military service or assigned a position in the reserve forces. No distinction is made between the assignment of men and women to reserve service.

The IDF may call up reservists for:

- reserve service of up to one month every three years, until the age of 40 (enlisted) or 45 (officers). Reservists may volunteer after this age, with the approval of the Manpower Directorate.

- immediate active duty in wartime.

All Israelis who served in the IDF and are under the age of 40, unless otherwise exempt, are eligible for reserve duty. Only those who completed at least 20 days of reserve duty within the past three years are considered active reservists.[44]

Non-IDF service

[edit]Other than the civil, i.e. non-military "National Service" (Sherut Leumi), IDF conscripts may serve in bodies other than the IDF in several ways.

The combat option is Israel Border Police (Magav – the exact translation from Hebrew means "border guard") service, part of the Israel Police. Some soldiers complete their IDF combat training and later undergo additional counter terror and Border Police training. These are assigned to Border Police units. The Border Police units fight side by side with the regular IDF combat units though to a lower capacity. They are also responsible for security in heavy urban areas such as Jerusalem and security and crime fighting in rural areas.

Non-combat services include the Mandatrory Police Service (Shaham, שח"מ) program, where youth serve in the Israeli Police, Israel Prison Service, or other wings of the Israeli Security Forces instead of the regular army service.

Women

[edit]

Israel is one of only a few nations that conscript women or deploy them in combat roles, although in practice, women can avoid conscription through a religious exemption and over a third of Israeli women do so.[45] As of 2010, 88% of all roles in the IDF are open to female candidates, and women could be found in 69% of all IDF positions.[46]

According to the IDF, 535 female Israeli soldiers were killed during service in the period 1962–2016,[47] and dozens before then. The IDF says that fewer than 4 percent of women are in combat positions. Rather, they are concentrated in "combat-support" positions which command a lower compensation and status than combat positions.[48]

Civilian pilot and aeronautical engineer Alice Miller successfully petitioned the High Court of Justice to take the Israeli Air Force pilot training exams, after being rejected on grounds of gender. Though president Ezer Weizman, a former IAF commander, told Miller that she would be better off staying home and darning socks, the court eventually ruled in 1996 that the IAF could not exclude qualified women from pilot training. Even though Miller would not pass the exams, the ruling was a watershed, opening doors for women in new IDF roles. Female legislators took advantage of the momentum to draft a bill allowing women to volunteer for any position if they could qualify.[49]

In 2000, the Equality Amendment to the Military Service law stated that the right of women to serve in any role in the IDF is equal to the right of men.[50] Women have served in the military since before the founding of the state of Israel in 1948.[51] Women started to enter combat support and light combat roles in a few areas, including the Artillery Corps, infantry units and armoured divisions. A few platoons named Karakal were formed for men and women to serve together in light infantry. By 2000, Karakal became a full-fledged battalion, with a second mixed-gender battalion, Lions of the Jordan (אריות הירדן, Arayot Ha-Yarden) formed in 2015. Many women also joined the Border Police.[49]

In June 2011, Maj. General Orna Barbivai became the first female major general in the IDF, replacing the head of the directorate Maj. General Avi Zamir. Barbivai stated, "I am proud to be the first woman to become a major general and to be part of an organization in which equality is a central principle. Ninety percent of jobs in the IDF are open to women and I am sure that other women will continue to break down barriers."[52][53]

In 2013, the IDF announced they would, for the first time, allow a transgender woman to serve in the army as a female soldier.[54]

Elana Sztokman notes it would be "difficult to claim that women are equals in the IDF". "And tellingly, there is only one female general in the entire IDF," she adds.[48] In 2012, religious soldiers claimed they were promised they would not have to listen to women sing or lecture, but IAF Chief Rabbi Moshe Raved resigned because male religious soldiers were being required to do so.[55] In January 2015, three women IDF singers performed in one of the IDF's units. The performance was first disrupted by fifteen religious soldiers, who left in protest and then the Master Sergeant forced the women to end the performance because it was disturbing the religious soldiers. An IDF spokesperson announced an investigation of the incident: "We are aware of the incident and already begun examining it. The exclusion of women is not consistent with the values of the IDF."[56]

Defense Minister Moshe Ya'alon has also arranged for women to be excluded from recruitment centres catering to religious males.[57] As the IDF recruits more religious soldiers, the rights of male religious soldiers and women in the IDF come into conflict. Brig. Gen. Zeev Lehrer, who served on the chief of staff's panel of the integration of women, noted "There is a clear process of 'religionization' in the army, and the story of the women is a central piece of it. There are very strong pressures at work to halt the process of integrating women into the army, and they are coming from the direction of religion."[58]

Sex segregation is allowed in the IDF, which reached what it considers a "new milestone" in 2006, creating the first company of soldiers segregated in an all-female unit, the Nachshol (Hebrew for "giant wave") Reconnaissance Company. "We are the only unit in the world made up entirely of female combat soldiers," said Nachshol Company Commander Cpt. Dana Ben-Ezra. "Our effectiveness and the dividends we earn are the factors by which we are measured, not our gender."[59]

With the rise of social media platforms such as TikTok and Twitter, some critics claim that women in the IDF are frequently used as tools of propaganda, with official military accounts frequently posting attractive young women to create a sympathetic social media presence.[60]

Minorities in the IDF

[edit]Non-Jewish minorities tended to serve in one of several special units: the Sword Battalion, also known as Unit 300 or the Minorities Unit, until it was disbanded in 2015;[61] the Druze Reconnaissance Unit; and the Trackers Unit, composed mostly of Negev Bedouins. In 1982, the IDF general staff decided to integrate the armed forces by opening up other units to minorities, while placing some Jewish conscripts in the Minorities Unit. Until 1988, the Intelligence Corps and the Air Force remained closed to minorities.

Druze and Circassians

[edit]

Although Israel has a majority of Jewish soldiers, all citizens including large numbers of Druze and Circassian men are subject to mandatory conscription.[62] Originally, they served in the framework of a special unit called "The Minorities' Unit", which operated until 2015 in the form of the independent Herev Gdud ("Sword") battalion. However, since the 1980s Druze soldiers have increasingly protested this practice, which they considered a means of segregating them and denying them access to elite units (like sayeret units). The army has increasingly admitted Druze soldiers to regular combat units and promoted them to higher ranks from which they had been previously excluded.

In 2015, Rav Aluf Gadi Eizenkot ordered the unit's closure to assimilate the Druze soldiers no differently than Jewish soldiers, as part of an ongoing reorganization of the army. Several Druze officers reached ranks as high as Major General, and many received commendations for distinguished service. In proportion to their numbers, the Druze people achieve much higher—documented—levels in the Israeli army than other soldiers. Nevertheless, some Druze still charge that discrimination continues, such as exclusion from the Air Force, although the official low-security classification for Druze has been abolished for some time. The first Druze aircraft navigator completed his training course in 2005. Like all Air Force pilots, his identity is not disclosed. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, many Druze who had initially sided with the Arabs deserted their ranks to either return to their villages or side with Israel in various capacities.[63]

Since the late 1970s, the Druze Initiative Committee, centred at the village of Beit Jan and linked to Maki, has campaigned to abolish Druze conscription.

Military service is a tradition among some of the Druze population, with most opposition in Druze communities of the Golan Heights. 83 per cent of Druze boys serve in the army, according to the IDF's statistics.[64] According to the Israeli army in 2010, 369 Druze soldiers had been killed in combat operations since 1948.[65]

Bedouins and Israeli Arabs

[edit]

By law, all Israeli citizens are subject to conscription. The Defense Minister has complete discretion to grant exemption to individual citizens or classes of citizens. A long-standing policy dating to Israel's early years extends an exemption to all other Israeli minorities (most notably Israeli Arabs). However, there is a long-standing government policy of encouraging Bedouins to volunteer and of offering them various inducements, and in some impoverished Bedouin communities a military career seems one of the few means of (relative) social mobility available. Also, Muslims and Christians are accepted as volunteers, even if older than 18.[66]

From among non-Bedouin Arab citizens, the number of volunteers for military service—some Christian Arabs and even a few Muslim Arabs—is minute, and the government makes no special effort to increase it. Six Israeli Arabs have received orders of distinction as a result of their military service; of them the most famous is a Bedouin officer, Lieutenant Colonel Abd el-Majid Hidr (also known as Amos Yarkoni), who received the Order of Distinction. Vahid el Huzil was the first Bedouin to be a battalion commander.[67][68]

Until the second term of Yitzhak Rabin as Prime Minister (1992–1995), social benefits given to families in which at least one member (including a grandfather, uncle, or cousin) had served at some time in the armed forces were significantly higher than to "non-military" families, which was considered a means of blatant discrimination between Jews and Arabs. Rabin led the abolition of the measure, in the teeth of strong opposition from the Right. At present, the only official advantage of military service is the attaining of security clearance and serving in some types of government positions (in most cases, security-related), as well as some indirect benefits.

Rather than perform army service, Israeli Arab youths have the option to volunteer to national service and receive benefits similar to those received by discharged soldiers. The volunteers are generally allocated to Arab populations, where they assist with social and community matters. As of 2010[update], 1,473 Arabs were volunteering for national service. According to sources in the national service administration, Arab leaders are counselling youths to refrain from performing services to the state. According to a National Service official, "For years the Arab leadership has demanded, justifiably, benefits for Arab youths similar to those received by discharged soldiers. Now, when this opportunity is available, it is precisely these leaders who reject the state's call to come and do the service, and receive these benefits."[69]

Although Arabs are not obliged to serve in the IDF, any Arab can volunteer. In 2008, a Muslim Arab woman was serving as a medic with unit 669.[70]

Cpl. Elinor Joseph from Haifa became the first female Arab combat soldier for IDF.[71]

Other Arab-Muslim officers who have served in the IDF are Second Lieutenant Hisham Abu Varia[72] and Major Ala Wahib, the highest ranking Muslim officer in the IDF in 2013.[73]

In October 2012, the IDF promoted Mona Abdo to become the first female Christian Arab to the rank of combat commander. Abdo had voluntarily enlisted in the IDF, which her family had encouraged, and transferred from the Ordnance Corps to the Caracal Battalion, a mixed-gender unit with both Jewish and Arab soldiers.[74]

In 2014, an increase in Israeli Christian Arabs joining the army was reported.[75]

Muslim Arabs have also been drafted into the Israel Defense Forces in increasing numbers in recent years. In 2020, 606 Muslim Arabs were drafted, compared to 489 in 2019 and 436 in 2018. More than half of those who have drafted have gone into combat roles.[76][77][78]

Ethiopian Jews

[edit]The IDF carried out extended missions in Ethiopia and neighbouring states, whose purpose was to protect Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel) and to help their immigration to Israel.[79] The IDF adopted policies and special activities for the absorption and integration of Ethiopian immigrant soldiers, reported to have much improved the achievements and integration of those soldiers in the army, and Israeli society in general.[80][81] Statistical research showed that the Ethiopian soldiers are esteemed as excellent soldiers and many aspire to be recruited to combat units.[82]

Haredim

[edit]

Under a special arrangement called Torato Umanuto, Haredi men could choose to defer service while enrolled in yeshivot and many avoided conscription altogether. This has given rise to tensions between the Israeli religious and secular communities. In 2024, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that Haredi men were eligible for compulsory service and the army began drafting them.[38][39]

Haredi males have the option of serving in the 97th "Netzah Yehuda" Infantry Battalion. This unit is a standard IDF infantry battalion focused on the Jenin region. To facilitate Haredi soldiers to serve, the Netzah Yehuda military bases follow the standards of Jewish dietary laws. The only women permitted on these bases were wives of soldiers and officers. Some Haredim serve in the IDF via the Hesder system, principally designed for the Religious Zionist sector. It is a 5-year program which includes 2 years of religious studies, 1½ years of military service and 1½ years of religious studies during which the soldiers can be recalled to active duty at any moment. Haredi soldiers may join other units of the IDF but rarely do. Although the IDF claims it will not discriminate against women, it is offering Haredim "women free and secular free" recruitment centres. Defense Minister Moshe Ya'alon expressed his willingness to relax regulations to meet the demands of ultra-Orthodox rabbis. Regulations regarding gender equality had already been relaxed so that Haredim could be assured that men would not receive physical exams from female medical staff.[83]

In 2024, the Hasmonean Brigade, a Haredi infantry unit, was created to accommodate Haredi soldiers. In January 2025, the unit received its first 50 soldiers.[84]

Since the beginning of the Israel-Hamas War, 600 Haredim have enlisted through the Shlav Bet program, an IDF recruitment track intended for Haredim over the age of 26 to complete military service.[85][86]

LGBT people

[edit]Since the early 1990s, sexual identity has presented no formal barrier in terms of soldiers' military specialization or eligibility for promotion.[87][88]

Until the 1980s, the IDF tended to discharge soldiers who were openly gay. In 1983, the IDF permitted homosexuals to serve but banned them from intelligence and top-secret positions. A decade later, professor Uzi Even,[89] an IDF reserves officer and chairman of Tel Aviv University's Chemistry Department, revealed that his rank had been revoked and that he had been barred from researching sensitive topics in military intelligence, solely because of his sexual orientation. His testimony to the Knesset in 1993 raised a political storm, forcing the IDF to remove such restrictions against gays.[87]

The chief of staff's policy states that it is strictly forbidden to harm or hurt anyone's dignity or feeling based on their gender or sexual orientation in any way, including signs, slogans, pictures, poems, lectures, any means of guidance, propaganda, publishing, voicing, and utterance. Moreover, gays in the IDF have additional rights, such as the right to take a shower alone if they want to. According to a University of California, Santa Barbara study,[89] a brigadier general stated that Israelis show a "great tolerance" for gay soldiers. Consul David Saranga at the Israeli Consulate in New York, who was interviewed by the St. Petersburg Times, said, "It's a non-issue. You can be a very good officer, a creative one, a brave one, and be gay at the same time."[87]

A study published by the Israel Gay Youth (IGY) Movement in January 2012 found that half of the homosexual soldiers who serve in the IDF suffer from violence and homophobia, although the head of the group said "I am happy to say that the intention among the top brass is to change that."[90]

Deaf and hard-of-hearing people

[edit]Israel is the only country in the world that requires deaf and hard-of-hearing people to serve in the military.[91] Sign language interpreters are provided during training, and many of them serve in non-combat capacities such as mapping and office work. The major language spoken by the deaf and hard-of-hearing in Israel is Israeli Sign Language (also called Shassi)–a language related to German Sign Language but not Hebrew or any other local language–though Israel and Palestine are home to numerous sign languages spoken by various populations like Bedouins' Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language.

Vegans

[edit]According to a Care2 report, vegans in the IDF may refuse vaccination if they oppose animal testing.[92] They are given artificial leather boots and a black fleece beret.[93] Until 2014, vegan soldiers in the IDF received special allowances to buy their own food, when this policy was replaced with vegan food being provided in all bases, as well as vegan combat rations being offered to vegan combat soldiers.[94]

Overseas volunteers

[edit]Non-immigrating foreign volunteers typically serve with the IDF in one of five ways:

- The Mahal program targets young non-Israeli Jews or Israeli citizens who grew up abroad (men younger than 24 and women younger than 21). The program consists typically of 18 months of IDF service, including a lengthy training for those in combat units or (for 18 months) one month of non-combat training and an additional two months of learning Hebrew after enlisting, if necessary. There are two additional subcategories of Mahal, both geared solely for religious men: Mahal Nahal Haredi (18 months), and Mahal Hesder, which combines yeshiva study of 5 months with IDF service of 16 months, for a total of 21 months. Similar IDF programs exist for Israeli overseas residents. To be accepted as a Mahal Volunteer, one must be of Jewish descent (at least one Jewish grandparent).

- Sar-El, an organization subordinate to the Israeli Logistics Corps, provides a volunteer program for non-Israeli citizens who are 17 years or older (or 15 if accompanied by a parent). The program is also aimed at Israeli citizens, aged 30 years or older, living abroad who did not serve in the Israeli Army and who now wish to finalize their status with the military. The program usually consists of three weeks of volunteer service on different rear army bases, doing non-combative work.

- Garin Tzabar offers a program mainly for Israelis who emigrated with their parents to the United States at a young age. Although a basic knowledge of the Hebrew language is not mandatory, it is helpful. Of all the programs listed, only Garin Tzabar requires full-length service in the IDF. The program is set up in stages: first, the participants go through five seminars in their country of origin, then have an absorption period in Israel at a kibbutz. Each delegation is adopted by a kibbutz in Israel and has living quarters designated for it. The delegation shares responsibilities in the kibbutz when on military leave. Participants start the program three months before being enlisted in the army at the beginning of August.

- Marva is short-term basic training for two months.

- Lev LaChayal is a program based at Yeshivat Lev Hatorah which takes a holistic approach to preparation for service. Being as ready as possible to integrate into Israeli culture, handling the physical challenges of the military, and maintaining religious values require a multi-pronged approach. The beit midrash learning, classes, physical training, and even recreational activities are designed to allow for maximum readiness.

Doctrine

[edit]IDF Code of Ethics

[edit]In 1992, the IDF drafted a Code of Conduct that combines international law, Israeli law, Jewish heritage and the IDF's traditional ethical code—the IDF Spirit (Hebrew: רוח צה"ל, Ru'ah Tzahal).[95]

The document defines four core values for all IDF soldiers to follow, including "defense of the state, its citizens and its residents", "love of the homeland and loyalty to the country", "human dignity" and "stateliness, as well as ten secondary values.[95][96][97][98]

"The Spirit of the IDF" (cf. supra) is still considered the only binding moral code that formally applies to the IDF troops. In 2009, Amos Yadlin (then head of Military Intelligence) suggested that the article he co-authored with Asa Kasher be ratified as a formal binding code, arguing that "the current code ['The Spirit of the IDF'] does not sufficiently address one of the army's most pressing challenges: asymmetric warfare against terrorist organizations that operate amid a civilian population".[99]

Details of the IDF's rules of engagement remain classified.[100]

Targeted killing

[edit]Targeted killing, targeted prevention[101][102] or assassination[103] is a tactic that has been repeatedly used by the IDF and other Israeli organisations in the course of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the Iran–Israel proxy conflict or other conflicts.[103]

In 2005, Asa Kasher and Amos Yadlin co-authored a noticed article published in the Journal of Military Ethics under the title: "Military Ethics of Fighting Terror: An Israeli Perspective". The article was meant as an "extension of the classical Just War Theory", and as a "[needed] third model" or missing paradigm besides which of "classical war (army) and law enforcement (police).", resulting in a "doctrine (...) on the background of the IDF fight against acts and activities of terror performed by Palestinian individuals and organizations."[104]

In this article, Kasher and Yadlin concluded that targeted killings of terrorists were justifiable, even at the cost of hitting nearby civilians. In a 2009 interview to Haaretz, Asa Kasher later confirmed, pointing to the fact that in an area in which the IDF does not have effective security control (e.g., Gaza, vs. East-Jerusalem), soldiers' lives protection takes priority over avoiding injury to enemy civilians.[105] Some, along with Avishai Margalit and Michael Walzer, have disputed this argument, arguing that such a position was "contrary to centuries of theorizing about the morality of war as well as international humanitarian law",[106] since drawing "a sharp line between combatants and noncombatants" would be "the only morally relevant distinction that all those involved in a war can agree on."[107]

Hannibal Directive

[edit]The Hannibal Directive is a controversial procedure that the IDF has used to prevent the capture of Israeli soldiers by enemy forces. It was introduced in 1986, after some abductions of IDF soldiers in Lebanon and the subsequent controversial prisoner exchanges. The full text of the directive has never been published and until 2003 Israeli military censorship even forbade any discussion of the subject in the press. The directive has been changed several times. At one time the formulation was that "the kidnapping must be stopped by all means, even at the price of striking and harming our own forces."[108]

The Hannibal directive has, at times, apparently existed in two different versions, one top-secret written version, accessible only to the upper echelon of the IDF, and one "oral law" version for division commanders and lower levels. In the latter versions, "by all means" was often interpreted literally, as in "an IDF soldier was better dead than abducted". In 2011, IDF Chief of Staff Benny Gantz stated the directive does not permit the killing of IDF soldiers.[109]

Dahiya doctrine

[edit]The Dahiya doctrine[110] is a military strategy of asymmetric warfare, outlined by former IDF Chief of General Staff Gadi Eizenkot, which encompasses the use of aerial and artillery fire against civilian infrastructure used by terrorist organizations[111] and endorses the employment of "disproportionate power" to secure that end.[112][113] The doctrine is named after the Dahieh neighborhood of Beirut, where Hezbollah was headquartered during the 2006 Lebanon War, which were heavily damaged by the IDF.[111]

Budget

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (July 2024) |

During 1950–66, Israel spent an average of 9% of its GDP on defense. Defence expenditures increased dramatically after both the 1967 and 1973 wars. They reached a high of about 30% of GDP in 1975, but have since come down significantly, following the signing of peace agreements with Jordan and Egypt.[114]

In September 2009, Defense Minister Ehud Barak, Finance Minister Yuval Steinitz and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu endorsed an additional NIS 1.5 billion for the defense budget to help Israel address problems regarding Iran. The budget changes came two months after Israel had approved its two-year budget. The defence budget in 2009 stood at NIS 48.6 billion and NIS 53.2 billion for 2010 – the highest amount in Israel's history. The figure constituted 6.3% of expected gross domestic product and 15.1% of the overall budget, even before the planned NIS 1.5 billion addition.[115]

In 2011, the prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu reversed course and moved to make significant cuts in the defence budget to pay for social programs.[116] The General Staff concluded that the proposed cuts endangered the battle readiness of the armed forces.[117] In 2012, Israel spent $15.2 billion on its armed forces, one of the highest ratios of defense spending to GDP among developed countries ($1,900 per person). However, Israel's spending per capita is below that of the US.[118]

Equipment and weaponry

[edit]Military equipment

[edit]

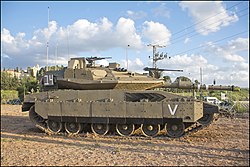

The IDF possesses various foreign and domestically produced weapons and computer systems. Some gear comes from the US (with some equipment modified for IDF use) such as the M4A1 and M16 assault rifles, the M24 SWS 7.62 mm bolt action sniper rifle, the SR-25 7.62 mm semi-automatic sniper rifle, the F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter jets, and the AH-1 Cobra and AH-64D Apache attack helicopters. Israel has also developed its own independent weapons industry, which has developed weapons and vehicles such as the Merkava battle tank series, Nesher and Kfir fighter aircraft, and various small arms such as the Galil and Tavor assault rifles, and the Uzi submachine gun. Israel has also installed a variant of the Samson RCWS, a remote controlled weapons platform, which can include machine guns, grenade launchers, and anti-tank missiles on a remotely operated turret, in pillboxes along the Gaza–Israel barrier intended to prevent Palestinian militants from entering its territory.[119][120]

Israel has developed observation balloons equipped with sophisticated cameras and surveillance systems used to thwart terror attacks from Gaza.[121] The IDF also possesses advanced combat engineering equipment which includes the IDF Caterpillar D9 armoured bulldozer, IDF Puma CEV, Tzefa Shiryon and CARPET minefield breaching rockets, and a variety of robots and explosive devices.

The IDF has several large internal research and development departments, and it purchases many technologies produced by the Israeli security industries including IAI, IMI, Elbit Systems, Rafael, and dozens of smaller firms. Many of these developments have been battle-tested in Israel's numerous military engagements, making the relationship mutually beneficial, the IDF getting tailor-made solutions and the industries a good reputation.[citation needed]

In response to the price overruns on the US Littoral Combat Ship program, Israel is considering producing their own warships, which would take a decade[122] and depend on diverting US financing to the project.[123]

Main developments

[edit]

Israel's military technology is famous for its firearms,[124][125] armoured fighting vehicles (tanks, tank-converted armoured personnel carriers (APCs), armoured bulldozers, etc.),[126] unmanned aerial vehicles,[127] and rocketry (missiles and rockets).[128] Israel also has manufactured aircraft including the Kfir (reserve), IAI Lavi (cancelled), and the IAI Phalcon Airborne early warning System, and naval systems (patrol and missile ships). Much of the IDF's electronic systems (intelligence, communication, command and control, navigation etc.) are Israeli-developed, including many systems installed on foreign platforms (esp. aircraft, tanks and submarines), as are many of its precision-guided munitions. Israel is the world's largest exporter of drones.[129]

Israel Military Industries (IMI), as well as its former subsidiary Israel Weapon Industries, are known for their firearms.[125] The IMI Galil, the Uzi, the IMI Negev light machine gun and the new Tavor TAR-21 Bullpup assault rifle are used by the IDF. The Rafael Advanced Defense Systems Spike missile is one of the most widely exported ATGMs in the world.[130]

Israel's Arrow anti-ballistic missile system, jointly funded and produced by Israel and the United States, has successfully conducted combat intercepts of incoming ballistic missile attacks.[131] The Iron Dome system against short-range rockets is operational and proved to be successful, intercepting hundreds of Qassam, 122 mm Grad and Fajr-5 artillery rockets fire by Palestinian militants from the Gaza Strip.[132][133] David's Sling, an anti-missile system designed to counter medium range rockets, became operational in 2017. Israel has also worked with the US on the development of a tactical high energy laser system against medium-range rockets (called Nautilus or THEL). Iron Beam is a short-range laser beam air defence system, created to eliminate rockets, artillery, and mortar bombs. With a range of several kilometres, it complements the Iron Dome system, which is specifically designed for intercepting missiles launched from greater distances.[134]

Israel has the independent capability of launching reconnaissance satellites into orbit, a capability shared with Russia, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, South Korea, Italy, Germany, the People's Republic of China, India, Japan, Brazil and Ukraine. Israeli security industries developed both the satellites (Ofeq) and the launchers (Shavit).[135][136]

Israel is known to have developed nuclear weapons.[137] Israel does not officially acknowledge its nuclear weapons program. It is thought Israel possesses between one hundred and four hundred nuclear warheads.[137][138] It is believed that Jericho intercontinental ballistic missiles are capable of delivering nuclear warheads with a superior degree of accuracy and a range of 11,500 km.[139] Israeli F-15I and F-16 fighter-bomber aircraft also have been cited as possible nuclear delivery systems (these aircraft types are nuclear capable in the US Air Force).[140][141][142] The U.S. Air Force F-15E has tactical nuclear weapon (B61 and B83 bombs) capability.[143] It has been asserted that Dolphin-class submarines have been adapted to carry Popeye Turbo Submarine-launched cruise missiles with nuclear warheads, so as to give Israel a second strike capacity.[144][145]

In 2006, Israel deployed the Wolf Armoured Vehicle APC for use in urban warfare and to protect VIPs.

Field rations

[edit]Field rations, called manot krav, usually consist of canned tuna, sardines, beans, stuffed vine leaves, maize and fruit cocktail and bars of halva. Packets of fruit-flavoured drink powder are provided along with condiments like ketchup, mustard, chocolate spread and jam. Around 2010, the IDF announced that certain freeze-dried MREs served in water-activated disposable heaters like goulash, turkey schwarma and meatballs would be introduced as field rations.[146]

One staple of these rations was loof, a type of Kosher spam made from chicken or beef that was phased out around 2008.[147] Food historian Gil Marks has written that: "Many Israeli soldiers insist that Loof uses all the parts of the cow that the hot dog manufacturers will not accept, but no one outside of the manufacturer and the kosher supervisors know what is inside."[148]

Development plans

[edit]

The IDF is planning several technological upgrades and structural reforms for the future of its land, air, and sea branches. Training has been increased, including cooperation between ground, air, and naval units.[149]

The Israeli Army is phasing out the M-16 rifle from all ground units in favor of the IMI Tavor variants, most recently the IWI Tavor X95 flat-top ("Micro-Tavor Dor Gimel").[150] The IDF is replacing its outdated M113 armored personnel carriers in favor of new Namer APCs, with 200 ordered in 2014, the Eitan AFV, and is upgrading its IDF Achzarit APCs.[151][152] The IDF announced plans to streamline its military bureaucracy so as to better maintain its reserve force, which a 2014 State Comptroller report noted was under-trained and may not be able to fulfill wartime missions. As part of the plans, 100,000 reservists will be discharged, and training for the remainder will be improved. The officer corps will be slashed by 5,000. Infantry and light artillery brigades will be reduced to increase training standards among the rest.[153]

The IDF is planning a future tank to replace the Merkava. The new tank will be able to fire lasers and electromagnetic pulses, run on a hybrid engine, run with a crew as small as two, will be faster, and will be better protected, with emphasis on protection systems such as the Trophy over armour.[154][155] The Combat Engineering Corps assimilated new technologies, mainly in tunnel detection and unmanned ground vehicles and military robots, such as remote-controlled IDF Caterpillar D9T "Panda" armoured bulldozers, Sahar engineering scout robot and improved Remotec ANDROS robots.

The Israeli Air Force will purchase as many as 100 F-35 Lightning II fighter jets from the United States. The aircraft will be modified and designated F-35I. They will use Israeli-built electronic warfare systems, outer wings, guided bombs, and air-to-air missiles.[156][157][158] As part of a 2013 arms deal, the IAF will purchase KC-135 Stratotanker aerial refueling aircraft and V-22 Osprey multi-mission aircraft from the United States, as well as advanced radars for warplanes and missiles designed to take out radars.[159] In April 2013, an Israeli official stated that within 40–50 years, piloted aircraft would be phased out of service by unmanned aerial vehicles capable of executing nearly any operation that can be performed by piloted combat aircraft. Israel's military industries are reportedly on the path to developing such technology in a few decades. Israel will also manufacture tactical satellites for military use.[160]

The Israeli Navy is currently expanding its submarine fleet, with a planned total of six Dolphin class submarines. Currently, five have been delivered, with the sixth, INS Drakon, expected to be delivered in 2020.[161] It is also upgrading and expanding its surface fleet. It is planning to upgrade the electronic warfare systems of its Sa'ar 5-class corvettes and Sa'ar 4.5 class missile boats,[162] and has ordered two new classes of warship: the Sa'ar 6-class corvette (a variant of the Braunschweig-class corvette) and the Sa'ar 72-class corvette, an improved and enlarged version of the Sa'ar 4.5-class. It plans to acquire four Saar 6-class corvettes and three Sa'ar 72-class corvettes. Israel is also developing marine artillery, including a gun capable of firing satellite-guided 155mm rounds between 75 and 120 kilometres.[163]

Foreign military relations

[edit]France

[edit]Starting on 14 May 1948 (5 Iyar 5708), when Israel became a sovereign state, a strong military, commercial and political relationship was established between France and Israel, which lasted until 1969. Between 1956 and 1966, the two countries had the highest level of military collaboration.[164]

United States

[edit]

In 1983, the United States and Israel established a Joint Political Military Group, which convenes twice a year. Both the U.S. and Israel participate in joint military planning and combined exercises and have collaborated on military research and weapons development. Additionally the U.S. military maintains two classified, pre-positioned War Reserve Stocks in Israel valued at $493 million.[citation needed] Israel has the official distinction of being an American Major non-NATO ally. Since 1976, Israel had been the largest annual recipient of U.S. foreign assistance. In 2009, Israel received $2.55 billion in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) grants from the Department of Defense.[165] All but 26% of this military aid is for the purchase of military hardware from American companies only.[165]

In October 2012, the United States and Israel began their biggest joint air and missile defence exercise, known as Austere Challenge 12, involving around 3,500 U.S. troops in the region along with 1,000 IDF personnel.[166] Germany and Britain also participated.[167]

Since mid-2017, the United States has operated an anti-missile system in the Negev region of Southern Israel, which is manned by 120 US Army personnel. It is a facility used by the U.S. inside a larger Mashabim Israeli Air Force base.[168]

India

[edit]India and Israel enjoy strong military and strategic ties.[169] Israeli authorities consider Indian citizens to be the most pro-Israel people in the world.[170][171][172][173][174] Apart from being Israel's second-largest economic partner in Asia,[175] India is also the largest customer of Israeli arms in the world.[176] In 2006, annual military sales between India and Israel stood at US$900 million, totalling around US$4,200,000,000 (equivalent to $7,458,334,899 in 2024) for the past two decades of arms trade.[177][178] Israeli defense firms had the largest exhibition at the 2009 Aero India show, during which Israel offered several state-of-the art weapons to India.[179]

The first major military deal between the two countries was the sale of Israeli Phalcon airborne warning and control system (AWACS) radars to the Indian Air Force in 2004.[180][181] In March 2009, India and Israel signed a US$1.4 billion deal under which Israel would sell India an advanced air-defense system.[182] India and Israel have also embarked on extensive space cooperation. In 2008, India's ISRO launched Israel's most technologically advanced spy satellite TecSAR.[183] In 2009, India reportedly developed a high-tech spy satellite RISAT-2 with significant assistance from Israel.[184] The satellite was successfully launched by India in April 2009.[185]

According to a Los Angeles Times news story, the 2008 Mumbai attacks were an attack on the growing India-Israel partnership. It quotes retired Indian Vice Admiral Premvir S. Das thus "Their aim was to... tell the Indians clearly that your growing linkage with Israel is not what you should be doing..."[186] In the past, India and Israel have held numerous joint anti-terror training exercises[187]

Despite regional crisis and ongoing Gaza war, defence supply lines to India remained active in 2023-24, as political ties and defence buyers kept the relationship operational.[188]

Germany

[edit]

Germany developed the Dolphin submarine and supplied it to Israel. Two submarines were donated by Germany.[189] The military co-operation has been discreet but mutually profitable: Israeli intelligence, for example, sent captured Warsaw Pact armor to West Germany to be analyzed. The results aided the German development of an anti-tank system.[190] Israel also trained members of GSG 9, a German counter-terrorism and special operations unit.[191] The Israeli Merkava MK IV tank uses a German V12 engine produced under license.[192]

In 2008, the website DefenseNews revealed that Germany and Israel had been jointly developing a nuclear warning system, Operation Bluebird.[193][194]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom has supplied equipment and spare parts for Sa'ar 4.5-class missile boats and F-4 Phantom fighter-bombers, components for small-calibre artillery ammunition and air-to-surface missiles, and engines for Elbit Hermes 450 Unmanned aerial vehicles. British arms sales to Israel mainly consist of light weaponry, and ammunition and components for helicopters, tanks, armoured personnel carriers, and combat aircraft.[195][196]

Russia

[edit]On 19 October 1999, the Defense Minister of China, General Chi Haotian, after meeting with Syrian Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass in Damascus, Syria, to discuss expanding military ties between Syria and China, then flew directly to Israel and met with Ehud Barak, the then Prime Minister and Defense Minister of Israel where they discussed military relations. Among the military arrangements was a $1 billion Israeli–Russian sale of military aircraft to China, which were to be jointly produced by Russia and Israel.[197]

Russia has bought drones from Israel.[198][199][200][201][202]

China

[edit]Israel is the second-largest foreign supplier of arms to the People's Republic of China, only after the Russian Federation. China has purchased a wide array of military hardware from Israel, including Unmanned aerial vehicles and communications satellites. China has become an extensive market for Israel's military industries and arms manufacturers, and trade with Israel has allowed it to obtain "dual-use" technology which the United States and European Union were reluctant to provide.[203] In 2010 Yair Golan, head of IDF Home Front Command visited China to strengthen military ties.[204] In 2012, IDF Chief of Staff Benny Gantz visited China for high-level talks with the Chinese defence establishment.[205]

Cyprus

[edit]As closely neighbouring countries, Israel and Cyprus have enjoyed greatly improving diplomatic relations since 2010. During the Mount Carmel Forest Fire, Cyprus dispatched two aviation assets to assist fire-fighting operations in Israel – the first time Cypriot Government aircraft were permitted to operate from Israeli airfields in a non-civil capacity.[206] Israel and Cyprus have closely cooperated in maritime activities relating to Gaza, since 2010, and have reportedly begun an extensive sharing program of regional intelligence to support mutual security concerns. In May 2012, it was widely reported that the Israeli Air Force had been granted unrestricted access to the Nicosia Flight Information Region of Cyprus and that Israeli aviation assets may have operated over the island itself.[207]

Greece

[edit]

Since 2010, the Israeli and Greek air forces trained jointly in Greece, indicating a boost in ties due in large part to Israel's rift with Turkey.[208] Recent purchases include 100 million euro deal between Greece and Israel for the purchase of SPICE 1000 and SPICE 2000 pound bomb kits.[209] In November 2011, the Israeli Air Force hosted Greece's Hellenic Air Force in a joint exercise at the Uvda base.[210][211] Similar training was held in 2012 by the IAF in cooperation with the Hellenic Air Force in the Peloponnese and parts of southern Greece in a response to the need of the IAF training of pilots in unfamiliar areas.[212][213] On March 14, 2013, the navies of Israel, Greece and the US held a two-week joint military exercise for the third year in a row. The annual operation is nicknamed Noble Dina and was established in 2011. Similar to Noble Dina in 2012, the exercise in 2013 included defending offshore natural gas platforms and simulated air-to-air combat and anti-submarine warfare.[214][215][216] In March 2017, Israel participated in the large-scale "Iniochus 2017" military exercise, which is organized annually by Greece, along with USA, Italy and the United Arab Emirates.[217][218]

Turkey

[edit]Israel has provided extensive military assistance to Turkey. Israel sold Turkey IAI Heron Unmanned aerial vehicles, and modernized Turkey's F-4 Phantom and Northrop F-5 aircraft at the cost of $900 million. Turkey's main battle tank is the Israeli-made Sabra tank, of which Turkey has 170. Israel later upgraded them for $500 million. Israel has also supplied Turkey with Israeli-made missiles, and the two nations have engaged in naval cooperation. Turkey allowed Israeli pilots to practice long-range flying over mountainous terrain in Turkey's Konya firing range, while Israel trains Turkish pilots at Israel's computerized firing range at Nevatim Airbase.[219][220] Until 2009, the Turkish military was one of Israel's largest defence customers. Israel defence companies have sold unmanned aerial vehicles and long-range targeting pods.[221]

However, relations have been strained in recent times. Since 2010 the Turkish military has declined to participate in the annual joint naval exercise with Israel and the United States.[222][223] The exercise, known as "Reliant Mermaid" was started in 1998 and included the Israeli, Turkish and American navies.[224] The objective of the exercise is to practice search-and-rescue operations and to familiarize each navy with international partners who also operate in the Mediterranean Sea.[225]

Azerbaijan

[edit]Azerbaijan and Israel have engaged in intense cooperation since 1992.[226] Israeli military have been a major provider of battlefield aviation, artillery, antitank, and anti-infantry weaponry to Azerbaijan.[227][228] In 2009, Israeli President Shimon Peres made a visit to Azerbaijan where military relations were expanded further, with the Israeli company Aeronautics Defense Systems Ltd announcing it was going to build a factory in Baku.[229]

In 2012, Israel and Azerbaijan signed an agreement according to which state-run Israel Aerospace Industries would sell $1.6 billion in drones and anti-aircraft and missile defense systems to Azerbaijan.[230] In March 2012, the magazine Foreign Policy reported that the Israeli Air Force may be preparing to use the Sitalchay Military Airbase, located 500 km (310 mi) from the Iranian border, for air strikes against the nuclear program of Iran,[231] later backed up by other media.[232]

Other countries

[edit]Israel has also sold to or received supplies of military equipment from the Czech Republic, Argentina, Portugal, Spain, Slovakia, Italy, South Africa, Canada, Australia, Poland, Slovenia, Romania, Hungary, Belgium, Austria, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina,[233] Georgia,[234] Vietnam and Colombia,[235] among others.

Commemoration

[edit]Parades

[edit]Israel Defense Forces parades took place on Independence Day, during the first 25 years of the State of Israel's existence. They were cancelled after 1973 due to financial and security concerns. The Israel Defense Forces still have weapon exhibitions country-wide on Independence Day, but they are stationary.

Commemoration

[edit]

Yom Hazikaron, Israel's day of remembrance for fallen soldiers, is observed on the 4th day of the month of Iyar of the Hebrew calendar, the day before the celebration of Independence Day.

The main museum for Israel's armoured corps is the Yad La-Shiryon in Latrun, which houses one of the largest tank museums in the world. Other significant military museums are the Israel Defense Forces History Museum (Batei Ha-Osef) in Tel Aviv, the Palmach Museum, and the Beit HaTotchan of artillery in Zikhron Ya'akov. The Israeli Air Force Museum is located at Hatzerim Airbase in the Negev Desert, and the Israeli Clandestine Immigration and Naval Museum, is in Haifa.

Israel's National Military Cemetery is at Mount Herzl. Other Israeli military cemeteries include Kiryat Shaul Military Cemetery in Tel Aviv, and Sgula military cemetery at Petah Tikva.

See also

[edit]

Security forces[edit]

|

Defense industry of Israel[edit]

|

Strategic communication[edit]

|

Related subjects[edit]

|

References and footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b International Institute for Strategic Studies (15 February 2023). The Military Balance 2023. London: Routledge. p. 331. ISBN 9781032508955. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b Tian, Nan; Fleurant, Aude; Kuimova, Alexandra; Wezeman, Pieter D.; Wezeman, Siemon T. (24 April 2022). "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2021" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ "THE STATE: Israel Defense Forces (IDF)". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

The IDF's three service branches (ground forces, air force, and navy) function under a unified command, headed by the Chief of the General Staff, with the rank of lieutenant-general, who is responsible to the minister of defence.

- ^ Mahler, Gregory S. (1990). Israel After Begin. SUNY Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7914-0367-9.

- ^ There is a wide range of estimates as to the size of the Israeli nuclear arsenal. For a compiled list of estimates, see Avner Cohen, The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel's bargain with the Bomb (Columbia University Press, 2010), Table 1, page xxvii and page 82.

- ^ a b "Israel: 50 Years of Occupation Abuses". Human Rights Watch. 4 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Israel, West Bank and Gaza". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 6 March 2024. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ "Israel's apartheid against Palestinians: a cruel system of domination and a crime against humanity". Amnesty International. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ a b Ostfeld, Zehava (1994). Shoshana Shiftel (ed.). An Army is Born (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Israel Ministry of Defense. pp. 113–116. ISBN 978-965-05-0695-7.

- ^ "חוק-יסוד: הצבא" [Basic Law: The Military] (PDF). Knesset (in Hebrew). Retrieved 19 September 2025.

- ^ Speedy (12 September 2011). "The Speedy Media: IDF's History". Thespeedymedia.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "The Israeli Flag (definitive stamp), 11/2010. Four Milestones in the History of the Flag: Nezz Ziona, 1891" (PDF). Israel Postal Company. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ a b Hemmingby, Cato. Conflict and Military Terminology: The Language of the Israel Defense Forces Archived January 11, 2024, at the Wayback Machine. Master's thesis, University of Oslo, 2011. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "HAGANAH". encyclopedia.com. The Gale Group, Inc. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

The Haganah ("defense") was founded in June 1920...

- ^ Ostfeld, Zehava (1994). Shoshana Shiftel (ed.). An Army is Born (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Israel Ministry of Defense. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-965-05-0695-7.

- ^ Pa'il, Meir (1982). "The Infantry Brigades". In Yehuda Schiff (ed.). IDF in Its Corps: Army and Security Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Vol. 11. Revivim Publishing. p. 15.

- ^ "Hezbollah hiding 100,000 missiles that can hit north, army says". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "The Obligations of Israel and the Palestinian Authority Under International Law". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Accountability for International Crimes in Palestine". ccrjustice.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ "Israel and Occupied Palestinian Territories". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ "Gaza: Apparent War Crimes During May Fighting". Human Rights Watch. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ "Indiscriminate violence and the collective punishment of Gaza must cease". Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. Médecins Sans Frontières. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Israel May Have Committed War Crimes in Jenin Operation, UN Palestinian Rights Official Says". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ "Israel/OPT: Investigate war crimes during August offensive on Gaza". Amnesty International. 25 October 2022. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ "Israeli Settlements Should be Classified as War Crimes, Says Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in OPT". United Nations. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- ^ "Amnesty International concludes Israel is committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza". Amnesty International. 5 December 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "Israel's Crime of Extermination, Acts of Genocide in Gaza | Human Rights Watch". 19 December 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Fabian, Emanuel. "Eyal Zamir takes over from Herzi Halevi as IDF chief, vows victory over Hamas". The Times of Israel. ISSN 0040-7909.

- ^ "IDF Ranks". IDF. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ Pgs 10 & 59, Israeli Defense Forces since 1973, Osprey Elite 8, Samuel Katz, 1986, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85045-687-5

- ^ Israeli Defence Forces since 1973, Osprey – Elite Series #8, Sam Katz 1986, ISNC 0-85045-887-8

- ^ a b "Guide to Israeli Militaria, Insignia, Badges, Uniforms & Unit Formations at Historama.com | The Online History Shop". Historama.com. 2 August 1945. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "GarinMahal – Your first day in the IDF". Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Katz & Volstad, Israeli Elite Units since 1948 (1988), pp. 53–54; 56.

- ^ Katz & Volstad, Israeli Elite Units since 1948 (1988), pp. 54–55; 57–59.

- ^ Katz & Volstad, Israeli Elite Units since 1948 (1988), p. 60.

- ^ a b "Paratroopers Brigade". Israeli Defense Forces. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Israel's high court orders the army to draft ultra-Orthodox men, rattling Netanyahu's government". AP News. 25 June 2024. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b Fabian, Emanuel (18 July 2024). "IDF to begin drafting 3,000 Haredi men starting Sunday, in three waves". Times of Israel.

- ^ "This Day in Jewish History / A Yeshiva Head and Settler Who Had a Change of Heart Is Born". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ Zrahiya, Zvi (6 November 2011). "Barak Wants to Pay Minimum Wage to IDF Conscripts". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Gross, Judah Ari. "Government raises soldiers' pay following major backlash over high pensions". The Times of Israel. ISSN 0040-7909.

- ^ Dayan, Aryeh (3 March 2002). "Pacifists are fighting hard against the draft". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ "Just a quarter of all eligible reservists serve in the IDF". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Abuse of IDF Exemptions Questioned Archived 10 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Jewish Daily Forward, 16 December 2009

- ^ Statistics: Women's Service in the IDF for 2010 Archived 13 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine IDF, 25 August 2010

- ^ "Israeli woman who broke barriers downed by Hezbollah rocket as 2006 combat volunteer – Israel News". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ a b Gaza: It's a Man's War Archived 8 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic, 7 August 2014

- ^ a b Lauren Gelfond Feldinger (21 September 2008). "Skirting history". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Integration of women in the IDF". Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 8 March 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Women in the IDF". Israel Defense Forces. 7 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Katz, Yaakov (23 July 2011). "Orna Barbivai becomes first female IDF major general". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ Greenberg, Hanan (26 May 2011). "IDF names 1st female major-general". Yedioth Ahronot. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Transgender in the IDF". AWiderBridge. 7 August 2013. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Haredi soldier warns: We'll leave IDF over women's singing Archived 23 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine YNET, 4 January 2012

- ^ Female soldiers were not permitted to sing the national anthem Archived 6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Jerusalem Online, 11 January 2015

- ^ IDF offers haredim 'women-free' recruitment centers Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine YNET, 31 October 2014

- ^ No Touching Archived 7 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Slate, 11 October 2012

- ^ Leading the way in gender equality Archived 7 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine IDF, 27 January 2013

- ^ Dickson, Ej (27 May 2021). "Why Are Israeli Defense Forces Soldiers Posting Thirst Traps on TikTok?". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Cohen, Gili (19 May 2015). "IDF to disband Druze battalion after more than 40 years' service". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ "IDF human resources site" (in Hebrew). IDF. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ Gelber, Yoav (1 April 1995). "Druze and Jews in the war of 1948. (Israel-Arab War of 1948–49)". Middle Eastern Studies. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

- ^ Larry Derfner (15 January 2009). "Covenant of blood". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.