Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conscription

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

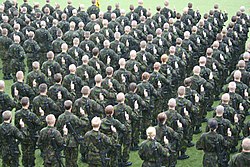

Conscription, also known as the draft in American English, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law.[1] Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day under various names. The modern system of near-universal national conscription for young men dates to the French Revolution in the 1790s, where it became the basis of a very large and powerful military. Most European nations later copied the system in peacetime, so that men at a certain age would serve 1 to 8 years on active duty and then transfer to the reserve force.[2]

Conscription is controversial for a range of reasons, including conscientious objection to military engagements on religious or philosophical grounds; political objection, for example to service for a disliked government or unpopular war; sexism, in that historically only men have been subject to the draft; and ideological objection, for example, to a perceived violation of individual rights. Those conscripted may evade service, sometimes by leaving the country,[3] and seeking asylum in another country. Some selection systems accommodate these attitudes by providing alternative service outside combat-operations roles or even outside the military, such as siviilipalvelus (alternative civil service) in Finland and Zivildienst (compulsory community service) in Austria and Switzerland. Several countries conscript male soldiers not only for armed forces, but also for paramilitary agencies, which are dedicated to police-like domestic-only service like internal troops, border guards or non-combat rescue duties like civil defence.

As of 2025, many states no longer conscript their citizens, relying instead upon professional militaries with volunteers. The ability to rely on such an arrangement, however, presupposes some degree of predictability with regard to both war-fighting requirements and the scope of hostilities. Many states that have abolished conscription still, therefore, reserve the power to resume conscription during wartime or times of crisis.[4] States involved in wars or interstate rivalries are most likely to implement conscription, and democracies are less likely than autocracies to implement conscription.[5] With a few exceptions, such as Singapore and Egypt, former British colonies are less likely to have conscription, as they are influenced by British anti-conscription norms that can be traced back to the English Civil War; the United Kingdom abolished conscription in 1960.[5] Conscription in the United States has not been enforced since 1973. Conscription was ended in most European countries, with the system still being in force in Scandinavian countries, Finland, Switzerland, Austria, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey and several countries of the former Eastern Bloc.

History

[edit]In pre-modern times

[edit]Ilkum

[edit]Around the reign of Hammurabi (1791–1750 BC), the Babylonian Empire used a system of conscription called Ilkum. Under that system those eligible were required to serve in the royal army in time of war. During times of peace they were instead required to provide labour for other activities of the state. In return for this service, people subject to it gained the right to hold land. It is possible that this right was not to hold land per se but specific land supplied by the state.[6]

Various forms of avoiding military service are recorded. While it was outlawed by the Code of Hammurabi, the hiring of substitutes appears to have been practiced both before and after the creation of the code. Later records show that Ilkum commitments could become regularly traded. In other places, people simply left their towns to avoid their Ilkum service. Another option was to sell Ilkum lands and the commitments along with them. With the exception of a few exempted classes, this was forbidden by the Code of Hammurabi.[7]

Roman Dilectus

[edit]See Early Roman army.

Medieval period

[edit]Medieval levies

[edit]Under the feudal laws on the European continent, landowners in the medieval period enforced a system whereby all peasants, freemen commoners and noblemen aged 15 to 60 living in the countryside or in urban centers, were summoned for military duty when required by either the king or the local lord, bringing along the weapons and armor according to their wealth. These levies fought as footmen, sergeants, and men at arms under local superiors appointed by the king or the local lord such as the arrière-ban in France. Arrière-ban denoted a general levy, where all able-bodied males age 15 to 60 living in the Kingdom of France were summoned to go to war by the King (or the constable and the marshals). Men were summoned by the bailiff (or the sénéchal in the south). Bailiffs were military and political administrators installed by the King to steward and govern a specific area of a province following the king's commands and orders. The men summoned in this way were then summoned by the lieutenant who was the King's representative and military governor over an entire province comprising many bailiwicks, seneschalties and castellanies. All men from the richest noble to the poorest commoner were summoned under the arrière-ban and they were supposed to present themselves to the King or his officials.[8][9][10][11]

In medieval Scandinavia the leiðangr (Old Norse), leidang (Norwegian), leding, (Danish), ledung (Swedish), lichting (Dutch), expeditio (Latin) or sometimes leþing (Old English), was a levy of free farmers conscripted into coastal fleets for seasonal excursions and in defence of the realm.[12]

The bulk of the Anglo-Saxon English army, called the fyrd, was composed of part-time English soldiers drawn from the freemen of each county. In the 690s laws of Ine of Wessex, three levels of fines are imposed on different social classes for neglecting military service.[13]

Some modern writers claim military service in Europe was restricted to the landowning minor nobility. These thegns were the land-holding aristocracy of the time and were required to serve with their own armour and weapons for a certain number of days each year. The historian David Sturdy has cautioned about regarding the fyrd as a precursor to a modern national army composed of all ranks of society, describing it as a "ridiculous fantasy":

The persistent old belief that peasants and small farmers gathered to form a national army or fyrd is a strange delusion dreamt up by antiquarians in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries to justify universal military conscription.[14]

In feudal Japan the shogun decree of 1393 exempted money lenders from religious or military levies, in return for a yearly tax. The Ōnin War weakened the shogun and levies were imposed again on money lenders. This overlordism was arbitrary and unpredictable for commoners. While the money lenders were not poor, several overlords tapped them for income. Levies became necessary for the survival of the overlord, allowing the lord to impose taxes at will. These levies included tansen tax on agricultural land for ceremonial expenses. Yakubu takumai tax was raised on all land to rebuild the Ise Grand Shrine, and munabechisen tax was imposed on all houses. At the time, land in Kyoto was acquired by commoners through usury and in 1422 the shogun threatened to repossess the land of those commoners who failed to pay their levies.[15]

Military slavery

[edit]

The system of military slaves was widely used in the Middle East, beginning with the creation of the corps of Turkic slave-soldiers (ghulams or mamluks) by the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tasim in the 820s and 830s. The Mamluks (/ˈmæmluːk/; Arabic: مملوك, romanized: mamlūk (singular), مماليك, mamālīk (plural);[17] translated as "one who is owned",[20] meaning "slave")[22] were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-soldiers, and freed slaves who were assigned high-ranking military and administrative duties, serving the ruling Arab and Ottoman dynasties in the Muslim world.[26] The most enduring Mamluk realm was the knightly military class in medieval Egypt, which developed from the ranks of slave-soldiers.[27] Originally the Mamluks were slaves of Turkic origins from the Eurasian Steppe,[30] but the institution of military slavery spread to include Circassians,[32] Abkhazians,[33][34][35] Georgians,[39] Armenians,[41] Russians,[25] and Hungarians,[24] as well as peoples from the Balkans such as Albanians,[24][42] Greeks,[24] and South Slavs[44] (see Saqaliba). They also recruited from the Egyptians.[28] The "Mamluk/Ghulam Phenomenon",[23] as David Ayalon dubbed the creation of the specific warrior class,[45] was of great political importance; for one thing, it endured for nearly 1,000 years, from the 9th century to the early 19th century.

Over time, Mamluks became a powerful military knightly class in various Muslim societies that were controlled by dynastic Arab rulers.[46] Particularly in Egypt and Syria,[47] but also in the Ottoman Empire, Levant, Mesopotamia, and India, mamluks held political and military power.[24] In some cases, they attained the rank of sultan, while in others they held regional power as emirs or beys.[28] Most notably, Mamluk factions seized the sultanate centered on Egypt and Syria, and controlled it as the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517).[48] The Mamluk Sultanate famously defeated the Ilkhanate at the Battle of Ain Jalut. They had earlier fought the western European Christian Crusaders in 1154–1169 and 1213–1221, effectively driving them out of Egypt and the Levant. In 1302 the Mamluk Sultanate formally expelled the last Crusaders from the Levant, ending the era of the Crusades.[24][49] While Mamluks were purchased as property,[50] their status was above ordinary slaves, who were not allowed to carry weapons or perform certain tasks.[51] In places such as Egypt, from the Ayyubid dynasty to the time of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, mamluks were considered to be "true lords" and "true warriors", with social status above the general population in Egypt and the Levant.[24] In a sense, they were like enslaved mercenaries.[53]

In the middle of the 14th century, Ottoman sultan Murad I developed personal troops to be loyal to him, with a slave army called the Kapıkulu. The first units in the Janissary Corps were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's plunder in kind rather than monetarily; however, the continuing exploitation and enslavement of dhimmi peoples (i.e., non-Muslims), predominantly Balkan Christians,[54] constituted a continuing abuse of subject populations.[55][54][56][57] For a while, the Ottoman government supplied the Janissary Corps with recruits from the devşirme system of child levy enslavement.[58] Children were drafted at a young age and soon turned into slave-soldiers in an attempt to make them loyal to the Ottoman sultan.[55][54][56] The social status of devşirme recruits took on an immediate positive change, acquiring a greater guarantee of governmental rights and financial opportunities.[58] In poor areas officials were bribed by parents to make them take their sons, thus they would have better chances in life.[59] Initially, the Ottoman recruiters favoured Greeks and Albanians.[60][61] The Ottoman Empire began its expansion into Europe by invading the European portions of the Byzantine Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries up until the capture of Constantinople in 1453, establishing Islam as the state religion of the newly founded empire. The Ottoman Turks further expanded into Southeastern Europe and consolidated their political power by invading and conquering huge portions of the Serbian Empire, Bulgarian Empire, and the remaining territories of the Byzantine Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. As borders of the Ottoman Empire expanded, the devşirme system of child levy enslavement was extended to include Armenians, Bulgarians, Croats, Hungarians, Serbs, and later Bosniaks,[62][63][64][65][66] and, in rare instances, Romanians, Georgians, Circassians, Ukrainians, Poles, and southern Russians.[60] A number of distinguished military commanders of the Ottomans, and most of the imperial administrators and upper-level officials of the Empire, such as Pargalı İbrahim Pasha and Sokollu Mehmet Paşa, were recruited in this way.[67] By 1609, the Sultan's Kapıkulu forces increased to about 100,000.[68]

The slave trade in the Ottoman Empire supplied the ranks of the Ottoman army between the 15th and 19th centuries.[55][54][56] They were useful in preventing both the slave rebellions and the breakup of the Empire itself, especially due to the rising tide of nationalism among European peoples in its Balkan provinces from the 17th century onwards.[55] Along with the Balkans, the Black Sea Region remained a significant source of high-value slaves for the Ottomans.[70] Throughout the 16th to 19th centuries, the Barbary States sent pirates to raid nearby parts of Europe in order to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in the Muslim world, primarily in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire, throughout the Renaissance and early modern period.[71] According to historian Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th centuries, Barbary pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves, although these numbers are disputed.[71][72] These slaves were captured mainly from the crews of captured vessels,[73] from coastal villages in Spain and Portugal, and from farther places like the Italian Peninsula, France, or England, the Netherlands, Ireland, the Azores Islands, and even Iceland.[71] For a long time, until the early 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.[74] The Crimean Tatars frequently mounted raids into the Danubian Principalities, Poland–Lithuania, and Russia to enslave people whom they could capture.[21]

Apart from the effect of a lengthy period under Ottoman domination, many of the subject populations were periodically and forcefully converted to Islam[55][54][56] as a result of a deliberate move by the Ottoman Turks as part of a policy of ensuring the loyalty of the population against a potential Venetian invasion. However, Islam was spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman sultan through the devşirme system of child levy enslavement,[55][54][56] by which indigenous European Christian boys from the Balkans (predominantly Albanians, Bulgarians, Croats, Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, and Ukrainians) were taken, levied, subjected to forced circumcision and forced conversion to Islam,[55][54][56] and incorporated into the Ottoman army,[55][54][56] and jizya taxes.[55][56][75] Radushev states that the recruitment system based on child levy can be bisected into two periods: its first, or classical period, encompassing those first two centuries of regular execution and utilization to supply recruits; and a second, or modern period, which more focuses on its gradual change, decline, and ultimate abandonment, beginning in the 17th century.[58]

In later years, Ottoman sultans turned to the Barbary Pirates to supply the Janissary Corps. Their attacks on ships off the coast of Africa or in the Mediterranean, and subsequent capture of able-bodied men for ransom or sale provided some captives for the Ottoman state. From the 17th century onwards, the devşirme system became obsolete.[54] Eventually, the Ottoman sultan turned to foreign volunteers from the warrior clans of Circassians in southern Russia to fill the Janissary Corps. As a whole the system began to break down, the loyalty of the Jannissaries became increasingly suspect. The Janissary Corps was abolished by Mahmud II in 1826 in the Auspicious Incident, in which 6,000 or more were executed.[76] On the western coast of Africa, Berber Muslims captured non-Muslims to put to work as laborers. In Morocco, the Berbers looked south rather than north. The Moroccan sultan Moulay Ismail, called "the Bloodthirsty" (1672–1727), employed a corps of 150,000 black slaves, called the "Black Guard". He used them to coerce the country into submission.[77]

In modern times

[edit]

Modern conscription, the massed military enrollment of national citizens (levée en masse), was devised during the French Revolution, to enable the Republic to defend itself from the attacks of European monarchies. Deputy Jean-Baptiste Jourdan gave its name to the 5 September 1798 Act, whose first article stated: "Any Frenchman is a soldier and owes himself to the defense of the nation." It enabled the creation of the Grande Armée, what Napoleon Bonaparte called "the nation in arms", which overwhelmed European professional armies that often numbered only into the low tens of thousands. More than 2.6 million men were inducted into the French military in this way between the years 1800 and 1813.[78]

The defeat of the Prussian Army in particular shocked the Prussian establishment, which had believed it was invincible after the victories of Frederick the Great. The Prussians were used to relying on superior organization and tactical factors such as order of battle to focus superior troops against inferior ones. Given approximately equivalent forces, as was generally the case with professional armies, these factors showed considerable importance. However, they became considerably less important when the Prussian armies faced Napoleon's forces that outnumbered their own in some cases by more than ten to one. Scharnhorst advocated adopting the levée en masse, the military conscription used by France. The Krümpersystem was the beginning of short-term compulsory service in Prussia, as opposed to the long-term conscription previously used.[79]

In the Russian Empire, the military service time "owed" by serfs was 25 years at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1834 it was decreased to 20 years. The recruits were to be not younger than 17 and not older than 35.[80] In 1874 Russia introduced universal male conscription in the modern pattern, an innovation only made possible by the abolition of serfdom in 1861. New military law decreed that all male Russian subjects, when they reached the age of 20, were eligible to serve in the military for six years.[81]

In the decades prior to World War I universal male conscription along broadly Prussian lines became the norm for European armies, and those modeled on them. By 1914 the only substantial armies still completely dependent on voluntary enlistment were those of Britain and the United States. Some colonial powers such as France reserved their conscript armies for home service while maintaining professional units for overseas duties.[82]

World Wars

[edit]

The range of eligible ages for conscripting was expanded to meet national demand during the World Wars. In the United States, the Selective Service System drafted men for World War I initially in an age range from 21 to 30 but expanded its eligibility in 1918 to an age range of 18 to 45.[83] In the case of a widespread mobilization of forces where service includes homefront defense, ages of conscripts may range much higher, with the oldest conscripts serving in roles requiring lesser mobility.[citation needed]

Expanded-age conscription was common during the Second World War: in Britain, it was commonly known as "call-up" and extended to age 51. Nazi Germany termed it Volkssturm ("People's Storm") and included boys as young as 16 and men as old as 60.[84] During the Second World War, both Britain and the Soviet Union conscripted women. The United States was on the verge of drafting women into the Nurse Corps because it anticipated it would need the extra personnel for its planned invasion of Japan. However, the Japanese surrendered and the idea was abandoned.[85]

During the Great Patriotic War, the Red Army conscripted nearly 30 million men.[86]

Arguments against conscription

[edit]Sexism

[edit]Men's rights activists,[87][88] feminists,[89][90][91] and opponents of discrimination against men[92][93]: 102 have criticized military conscription, or compulsory military service, as sexist. The National Coalition for Men, a men's rights group, sued the US Selective Service System in 2019, leading to it being declared unconstitutional by a US Federal Judge.[94][95] The federal district judge's opinion was unanimously overturned on appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit.[96] In September 2021, the House of Representatives passed the annual Defense Authorization Act, which included an amendment that states that "all Americans between the ages of 18 and 25 must register for selective service." This amendment omitted the word "male", which would have extended a potential draft to women; however, the amendment was removed before the National Defense Authorization Act was passed.[97][98][99]

Feminists have argued, first, that military conscription is sexist because wars serve the interests of what they view as the patriarchy; second, that the military is a sexist institution and that conscripts are therefore indoctrinated into sexism; and third, that conscription of men normalizes violence by men as socially acceptable.[100][101] Feminists have been organizers and participants in resistance to conscription in several countries.[102][103][104][105]

Conscription has also been criticized on the ground that, historically, only men have been subjected to conscription.[93][106][107][108][109] Men who opt out or are deemed unfit for military service must often perform alternative service, such as Zivildienst in Austria, Germany and Switzerland, or pay extra taxes,[110] whereas women do not have these obligations. In the US, men who do not register with the Selective Service cannot apply for citizenship, receive federal financial aid, grants or loans, be employed by the federal government, be admitted to public colleges or universities, or, in some states, obtain a driver's license.[111][112]

Involuntary servitude

[edit]

Many American libertarians oppose conscription and call for the abolition of the Selective Service System, arguing that impressment of individuals into the armed forces amounts to involuntary servitude.[113] For example, Ron Paul, a former U.S. Libertarian Party presidential nominee, has said that conscription "is wrongly associated with patriotism, when it really represents slavery and involuntary servitude".[114] The philosopher Ayn Rand opposed conscription, opining that "of all the statist violations of individual rights in a mixed economy, the military draft is the worst. It is an abrogation of rights. It negates man's fundamental right—the right to life—and establishes the fundamental principle of statism: that a man's life belongs to the state, and the state may claim it by compelling him to sacrifice it in battle."[115]

In 1917, a number of radicals[who?] and anarchists, including Emma Goldman, challenged the new draft law in federal court, arguing that it was a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment's prohibition against slavery and involuntary servitude. However, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the draft act in the case of Arver v. United States on 7 January 1918, on the ground that the Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war and to raise and support armies. The Court also relied on the principle of the reciprocal rights and duties of citizens. "It may not be doubted that the very conception of a just government in its duty to the citizen includes the reciprocal obligation of the citizen to render military service in case of need and the right to compel."[116]

Economic

[edit]It can be argued that in a cost-to-benefit ratio, conscription during peacetime is not worthwhile.[117] Months or years of service performed by the most fit and capable subtract from the productivity of the economy; add to this the cost of training them, and in some countries paying them. Compared to these extensive costs, some would argue there is very little benefit; if there ever was a war then conscription and basic training could be completed quickly, and in any case there is little threat of a war in most countries with conscription. In the United States, every male resident is required by law to register with the Selective Service System within 30 days following his 18th birthday and be available for a draft; this is often accomplished automatically by a motor vehicle department during licensing or by voter registration.[118]

According to Milton Friedman the cost of conscription can be related to the parable of the broken window in anti-draft arguments. The cost of the work, military service, does not disappear even if no salary is paid. The work effort of the conscripts is effectively wasted, as an unwilling workforce is extremely inefficient. The impact is especially severe in wartime, when civilian professionals are forced to fight as amateur soldiers. Not only is the work effort of the conscripts wasted and productivity lost, but professionally skilled conscripts are also difficult to replace in the civilian workforce. Every soldier conscripted in the army is taken away from his civilian work, and away from contributing to the economy which funds the military. This may be less a problem in an agrarian or pre-industrialized state where the level of education is generally low, and where a worker is easily replaced by another. However, this is potentially more costly in a post-industrial society where educational levels are high and where the workforce is sophisticated and a replacement for a conscripted specialist is difficult to find. Even more dire economic consequences result if the professional conscripted as an amateur soldier is killed or maimed for life; his work effort and productivity are lost.[119]

Arguments for conscription

[edit]Political and moral motives

[edit]

Classical republicans promoted conscription as a tool for maintaining civilian control of the military, thereby preventing usurpation by a select class of warriors or mercenaries. Jean Jacques Rousseau argued vehemently against professional armies since he believed that it was the right and privilege of every citizen to participate to the defense of the whole society and that it was a mark of moral decline to leave the business to professionals. He based his belief upon the development of the Roman Republic, which came to an end at the same time as the Roman Army changed from a conscript to a professional force.[120] Similarly, Aristotle linked the division of armed service among the populace intimately with the political order of the state.[121] Niccolò Machiavelli argued strongly for political regimes to enlist their own subjects in the army throughout his works, such as The Prince and The Discourses on Livy, among his other writings.[122]

Other proponents, such as William James, consider both mandatory military and national service as ways of instilling maturity in young adults.[123] Some proponents, such as Jonathan Alter and Mickey Kaus, support a draft in order to reinforce social equality, create social consciousness, break down class divisions and allow young adults to immerse themselves in public enterprise.[124][125][126] This justification forms the basis of Israel's People's Army Model. Charles Rangel called for the reinstatement of the draft during the Iraq War not because he seriously expected it to be adopted but to stress how the socioeconomic restratification meant that very few children of upper-class Americans served in the all-volunteer American armed forces.[127]

Conscription has also been used for nation-building and immigrant integration.

Economic and resource efficiency

[edit]It is estimated by the British military that in a professional military, a company deployed for active duty in peacekeeping corresponds to three inactive companies at home. Salaries for each are paid from the military budget. In contrast, volunteers from a trained reserve are in their civilian jobs when they are not deployed.[128]

Under the total defense doctrine, conscription paired with periodic refresher training ensures that the entire able-bodied population of a country can be mobilized to defend against invasion or assist civil authorities during emergencies. For this reason, some European countries have reintroduced or debated reintroducing conscription during the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Military Keynesians often argue for conscription as a job guarantee. For example, it was more financially beneficial for less-educated young Portuguese men born in 1967 to participate in conscription than to participate in the highly competitive job market with men of the same age who continued to higher education.[129]

Drafting of women

[edit]

Throughout history, women have only been conscripted to join armed forces in a few countries, in contrast to the universal practice of conscription from among the male population. The traditional view has been that military service is a test of manhood and a rite of passage from boyhood into manhood.[130][131] In recent years, this position has been challenged on the basis that it violates gender equality, and some countries, have extended conscription obligations to women.

In 2006, eight countries (China, Eritrea, Israel, Green Libya, Malaysia, North Korea, Peru, and Taiwan) conscripted women into military service.[132]

Norway introduced female conscription in 2015, making it the first NATO member to have a legally compulsory national service for both men and women,[133] and the first country in the world to draft women on the same formal terms as men.[134] In practice only motivated volunteers are selected to join the army in Norway.[135]

Sweden introduced female conscription in 2010, but it was not activated until 2017. This made Sweden the second nation in Europe to draft women, and the second in the world (after Norway) to draft women on the same formal terms as men.[136]

Denmark has extended conscription to women from 2027 but then brought forward military service to 2025, also on a gender-neutral model.[137][138][139][140]

Israel has universal female conscription, and are having similar percantage of conscription to male one's. since the founding of the idf, female conscription was implemanted, but was limited to mostly non combative roles. since 2000, more diverse role were opened for women, and 92% of the roles are opened for them.[141][142][143][144]

In China, military law allows for the conscription of men and women, but in practice people serving are volunteers, given that China's large population (of over a billion) permits meeting its military targets with volunteers. Nevertheless, provinces reserve their right to conscript people, if their quotas are not met by volunteers.[145][146]

Sudanese law allows for conscription of women, but this is not implemented in practice.[147]

In the United Kingdom during World War II, beginning in 1941, women were brought into the scope of conscription but, as all women with dependent children were exempt and many women were informally left in occupations such as nursing or teaching, the number conscripted was relatively few.[148] Most women who were conscripted were sent to the factories, although some were part of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), Women's Land Army, and other women's services. None were assigned to combat roles unless they volunteered.[149] In contemporary United Kingdom, in July 2016, all exclusions on women serving in Ground Close Combat (GCC) roles were lifted.[150]

In the Soviet Union, there was never conscription of women for the armed forces, but the severe disruption of normal life and the high proportion of civilians affected by World War II after the German invasion attracted many volunteers for "The Great Patriotic War".[151] Medical doctors of both sexes could and would be conscripted (as officers). Also, the Soviet university education system required Department of Chemistry students of both sexes to complete an ROTC course in NBC defense, and such female reservist officers could be conscripted in times of war.

The United States came close to drafting women into the Nurse Corps in preparation for a planned invasion of Japan.[152][153]

In 1981 in the United States, several men filed lawsuit in the case Rostker v. Goldberg, alleging that the Selective Service Act of 1948 violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment by requiring that only men register with the Selective Service System (SSS). The Supreme Court eventually upheld the Act, stating that "the argument for registering women was based on considerations of equity, but Congress was entitled, in the exercise of its constitutional powers, to focus on the question of military need, rather than 'equity.'"[154] In 2013, Judge Gray H. Miller of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas ruled that the Service's men-only requirement was unconstitutional, as while at the time Rostker was decided, women were banned from serving in combat, the situation had since changed with the 2013 and 2015 restriction removals.[155] Miller's opinion was reversed by the Fifth Circuit, stating that only the Supreme Court could overturn the Supreme Court precedence from Rostker. The Supreme Court considered but declined to review the Fifth Circuit's ruling in June 2021.[156] In an opinion authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor and joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Brett Kavanaugh, the three justices agreed that the male-only draft was likely unconstitutional given the changes in the military's stance on the roles, but because Congress had been reviewing and evaluating legislation to eliminate its male-only draft requirement via the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service (NCMNPS) since 2016, it would have been inappropriate for the Court to act at that time.[157]

On 1 October 1999, in Taiwan, the Judicial Yuan of the Republic of China in its Interpretation 490 considered that the physical differences between males and females and the derived role differentiation in their respective social functions and lives would not make drafting only males a violation of the Constitution of the Republic of China.[158][(see discussion) verification needed] Though women are not conscripted in Taiwan, transsexual persons are exempt.[159]

In 2018, the Netherlands started including women in its draft registration system, although conscription is not currently enforced for either sex.[160] France and Portugal, where conscription was abolished, extended their symbolic, mandatory day of information on the armed forces for young people - called Defence and Citizenship Day in France and Day of National Defence in Portugal – to women in 1997 and 2008, respectively; at the same time, the military registry of both countries and obligation of military service in case of war was extended to women.[161][162]

Conscription of people with disabilities

[edit]Conscription for autistic people

[edit]Military authorities generally consider autistic individuals unfit for service, while neurodiversity advocates argue that they can be well-suited for military roles.[163]

- Sweden: Sweden's military excluded people with autism and ADHD. While they have since made it possible for people with mild ADHD to enlist if they meet specific criteria, autistic individuals remain excluded. This has led to several lawsuits from neurodiversity advocates, arguing that the policy is discriminatory. Erik Fenn, an autistic man who was initially denied service but won a discrimination lawsuit in 2024, leading to his conscription eligibility.[164]

- Denmark: Denmark classifies individuals with autism as "unfit for military service," and they are consequently excluded from conscription. An exception is made for those with Asperger's syndrome, but even they must prove a "just cause" for military service to be allowed to serve.[165]

- Norway: In Norway, autism is listed in a questionnaire alongside conditions like Down syndrome. This can result in even those with mild autism being deemed unfit for military service and excluded.[166]

- Israel: Israel generally exempts autistic people from military service, but they have been allowed to volunteer since 2008. Programs like "Titkadmu" and "Ro'im Rachok" support and encourage autistic individuals to volunteer for military roles.[167]

- Finland: Finland's policy has shifted over time. While autistic men were once routinely exempted from conscription, the military started including them as eligible candidates in the 2010s. According to a 2019 Finnish military news report, Finnish citizens with autism are subject to conscription.[168]

- Ukraine: In Ukraine, individuals with a moderate autism spectrum disorder are considered eligible for conscription. However, they are assigned to non-combat roles rather than serving on the front line.[169]

- South Korea: South Korea classifies individuals with autism as Grade 4, which exempts them from active-duty service but still requires them to perform reserve duty. Before 2018, most autistic individuals were required to serve on active duty.[170]

- Turkey: In Turkey, autistic people are officially exempt from conscription, but in practice, they may be suspected of draft evasion. Families often face difficult administrative procedures and multiple medical examinations to prove their diagnosis.[171]

Conscientious objection

[edit]A conscientious objector is an individual whose personal beliefs are incompatible with military service, or, more often, with any role in the armed forces.[172][173] In some countries, conscientious objectors have special legal status, which augments their conscription duties. For example, Sweden allows conscientious objectors to choose a service in the weapons-free civil defense.[174][175]

The reasons for refusing to serve in the military are varied. Some people are conscientious objectors for religious reasons. In particular, the members of the historic peace churches are pacifist by doctrine, and Jehovah's Witnesses, while not strictly pacifists, refuse to participate in the armed forces on the ground that they believe that Christians should be neutral in international conflicts.[176]

By country

[edit]This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (April 2025) |

| Country | Conscription[177] | Sex |

|---|---|---|

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2010)[178] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No. Voluntary; conscription may be required for specified reasons per Article 19 of Public Law No.24.429 promulgated on 5 January 1995.[179] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished by parliament in 1972)[180] | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[181] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (but can volunteer for service in Bangladesh Ansar) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (suspended in 1992; service not required of draftees inducted for 1994 military classes or any thereafter)[182] | N/A | |

| No. Laws allow for conscription only if volunteers are insufficient, but conscription has never been implemented.[183] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No | N/A

| |

| No[183] | N/A | |

| Yes (whenever annual number of volunteers falls short of government's goal)[184] | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished on 1 January 2006)[185] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes, but almost all recruits have been volunteers in recent years.[186] (Alternative service is cited in Brazilian law,[187] but a system has not been implemented.)[186] | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished by law on 1 January 2008)[188] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No. Legislative provision making all men of military age a Reserve Militia member was removed in 1904.[189] Conscription into a full-time military service took place in both world wars, with 1945 being the last year conscription was practice.[190] | N/A | |

| Yes (selective compulsory military service) | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No, however Male citizens 18 years of age and over are required to register for military service in People's Liberation Army recruiting offices (registration exempted for residents of Hong Kong and Macao special administrative regions).[191][192][193][194] | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (ended in 1969) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No. Frozen in 2008 due to low turnout, announced reintroduction by late 2025.[195][196][197] | Male | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2005)[198] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[199][200] | Male until 2026; Male and female from 2026.[137] | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (suspended in 2008) | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (18 months by law, but often extended indefinitely) | Male and female | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No, but the military can conduct callups when necessary. | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No (suspended during peacetime in 2001).[201] A voluntary national service (Service national universel, with the option of military or civil service for men and women) was instituted in 2021. | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[202] | Male | |

| No (suspended during peacetime by the federal legislature from 1 July 2011)[203] Reintroduced if volunteers are insufficient. | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2023) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service not available) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (peacetime conscription abolished in 2004)[204] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2003) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female Jews, male Druze and Circassians | |

| No (suspended during peacetime in 2005)[205] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 1945)[206][207] | N/A | |

| No (But the Jordan Government say that men without works or aren´t studying should do mandatory military service , also there are plans to reintroduce the conscription (for men) in 2026 , but it´s not certain if it will be reintroduced at this moment) | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[208] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[209] (abolished in 2007, reintroduced on January 1, 2024)[210] | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2007)[211] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A

| |

| Yes[212] About 3,000–4,000 conscripts each year must be selected, of whom up to 10% serve involuntarily.[213]) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No.[214] Malaysian National Service was suspended from January 2015 due to government budget cuts.[215] It resumed in 2016, then was abolished in 2018. However, in 2023 the government announced its revival pending approval in 2024. National Service Malaysia resumed again in January 2025 for supervised trial training Malaysian Armed Forces with collaboration various government agencies for the nationhood module. | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[216] | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (reintroduced in 2018)[217] | Male and female | |

| Yes[218] | Male and female | |

| Yes, enforced as of February 2024[update].[219][220] | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

(see details) |

No. Active conscription suspended in 1997 (except in Curaçao and Aruba).[citation needed][221] | Male and female |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished in December 1972) | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 1990) | N/A | |

| No (But government usually motives unmarried women and men to enter) | N/A | |

| No. However, under Nigeria's National Youths Service Corps Act, graduates from tertiary institutions are required to undertake national service for a year. The service begins with a 3-week military training. | ||

| Yes[222] | Male and female | |

| No (abolished in 2006)[223] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes by law, but in practice people are not forced to serve against their will.[135] Conscientious objectors have not been prosecuted since 2011; they are simply exempted from service.[224] | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2016)[225][226][228] | N/A | |

| No. Suspended in 2009, but military registration is still required.[229][230] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No. Peacetime conscription abolished in 2004, but there remains a symbolic military obligation for all 18-year-olds, of both sexes: National Defense Day (Dia da Defesa Nacional).[231] | Male and female | |

| Yes[232] | Male | |

| No (stopped in January 2007)[233] | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No. Abolished on January 1, 2011, but will be reintroduced in November 2025.[234] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No (abolished on January 1, 2006)[235] | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2003)[236] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (conscription of men aged 18–40 and women aged 18–30 is authorized, but not currently used) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (ended in 1994)[237] | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available). The military service law was established in 1948.[238] | Male | |

| Yes.[239] The minimum age is 18,[239] but there are reports of illegal conscription of children in the military.[240] | Male | |

| No (abolished by law on 31 December 2001)[241] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes. Abolished in 2010 but reintroduced in 2017 (alternative service available)[242] | Male and female | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[243] | Male | |

| No (abolished in 2024)[244] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (alternative service available).[245] According to the Defence Minister, from 2018 there will be no compulsory enrollment for military service;[246] however, all men born after 1995 will be subject to four months of compulsory military training, increasing to one full year after 2024 (for men born after 2005).[247] |

Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes (selective conscription for 2 years of public service) | Male and female | |

| Yes, but can be exempted if three years of Territorial Defense Student training are completed. Students who start but do not complete a Ror Dor course in high school are still permitted to continue coursework for two more years at a university. Otherwise, they face training or must draw a conscription lottery "black card". The government intends to abolish these rules in 2027.[248] | Male | |

| Yes (authorized in 2020) | Male and female | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| Yes[249] | Male | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes (abolished in 2013, reinstated in 2014 due to the Russo-Ukrainian War)[250] | Male | |

| Yes (alternative service available). Implemented in 2014, compulsory for all male citizens aged 18–30.[251] | Male | |

| No. Required from 1916 until 1920 and from 1939 until 31 December 1960 (except for the Bermuda Regiment, abolished in 2018).[252] | N/A | |

| No. Ended in 1973, but registration is still required of all men aged 18–25.[253] | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| Yes[254][255] | Male and female | |

| Yes | Male | |

| No | N/A | |

| No (abolished in 2001) | N/A | |

| No | N/A | |

| No | N/A |

Austria

[edit]Every male citizen of the Republic of Austria from the age of 17 up to 50, specialists up to 65 years is liable to military service. However, besides mobilization, conscription calls to a six-month long basic military training in the Bundesheer can be done up to the age of 35. For men refusing to undergo this training, a nine-month lasting community service is mandatory.

Belgium

[edit]Belgium abolished the conscription in 1994. The last conscripts left active service in February 1995. To this day (2019), a small minority of the Belgian citizens supports the idea of reintroducing military conscription, for both men and women.

Bulgaria

[edit]Bulgaria had conscription for males above 18 until it was ended in 2008.[256] Due to a shortfall in the army of some 5,500 soldiers,[257] parts of the former ruling coalition have expressed their support for the return of conscription, most notably Krasimir Karakachanov. Opposition towards this idea from the main coalition partner, GERB, saw a compromise in 2018, where instead of conscription, Bulgaria could have possibly introduced a voluntary military service by 2019 where young citizens can volunteer for a period of 6 to 9 months, receiving a basic wage. However, this has not gone forward.[258]

Cambodia

[edit]Since the signing of the Peace Accord in 1993, there has been no official conscription in Cambodia. Also the National Assembly has repeatedly rejected to reintroduce it due to popular resentment.[259] However, in November 2006, it was reintroduced. Although mandatory for all males between the ages of 18 and 30 (with some sources stating up to age 35), less than 20% of those in the age group are recruited amidst a downsizing of the armed forces.[260]

Canada

[edit]Compulsory service in a sedentary militia was practiced in Canada as early as 1669. In peacetime, compulsory service was typically limited to attending an annual muster, although the Canadian militia was mobilized for longer periods during wartime. Compulsory service in the sedentary militia continued until the early 1880s when Canada's sedentary Reserve Militia system fell into disuse. The legislative provision that formally made every male inhabitant aged 16 to 60 member of the Reserve Militia was removed in 1904, replaced with provisions that made them theoretically "liable to serve in the militia".[261]

Conscription into a full-time military service had only been instituted twice by the government of Canada, during both world wars. Conscription into the Canadian Expeditionary Force was practiced in the last year of the First World War in 1918. During the Second World War, conscription for home defence was introduced in 1940 and for overseas service in 1944. Conscription has not been practiced in Canada since the end of the Second World War in 1945.[262]

China

[edit]

Universal conscription in China dates back to the State of Qin, which eventually became the Qin Empire of 221 BC. Following unification, historical records show that a total of 300,000 conscript soldiers and 500,000 conscript labourers constructed the Great Wall of China.[263] In the following dynasties, universal conscription was abolished and reintroduced on numerous occasions.

As of 2011[update],[264] universal military conscription is theoretically mandatory in China, and reinforced by law. However, due to the large population of China and large pool of candidates available for recruitment, the People's Liberation Army has always had sufficient volunteers, so conscription has not been required in practice.[265][192][193][266]

Cuba

[edit]Cyprus

[edit]Military service in Cyprus has a deep rooted history entangled with the Cyprus problem.[267] Military service in the Cypriot National Guard is mandatory for all male citizens of the Republic of Cyprus, as well as any male non-citizens born of a parent of Greek Cypriot descent, lasting from the 1 January of the year in which they turn 18 years of age to 31 December, of the year in which they turn 50.[268][269] All male residents of Cyprus who are of military age (16 and over) are required to obtain an exit visa from the Ministry of Defense.[270] Currently, military conscription in Cyprus lasts up to 14 months.

Denmark

[edit]

Conscription is known in Denmark since the Viking Age, where one man out of every 10 had to serve the king. Frederick IV of Denmark changed the law in 1710 to every 4th man. The men were chosen by the landowner and it was seen as a penalty.

Since 12 February 1849, every physically fit man must do military service. According to §81 in the Constitution of Denmark, which was promulgated in 1849:

Every male person able to carry arms shall be liable with his person to contribute to the defence of his country under such rules as are laid down by Statute. — Constitution of Denmark[271]

The legislation about compulsory military service is articulated in the Danish Law of Conscription.[272] National service takes 4–12 months.[273] It is possible to postpone the duty when one is still in full-time education.[274] Every male turning 18 will be drafted to the 'Day of Defence', where they will be introduced to the Danish military and their health will be tested.[275] Physically unfit persons are not required to do military service.[273][276] It is only compulsory for men, while women are free to choose to join the Danish army.[277] Almost all of the men have been volunteers in recent years,[278] 96.9% of the total number of recruits having been volunteers in the 2015 draft.[279]

After lottery,[280] one can become a conscientious objector.[281] Total objection (refusal from alternative civilian service) results in up to 4 months jailtime according to the law.[282] However, in 2014 a Danish man, who signed up for the service and objected later, got only 14 days of home arrest.[283]

Eritrea

[edit]Estonia

[edit]Estonia adopted a policy of ajateenistus (literally "time service") in late 1991, having inherited the concept from Soviet legislature. According to §124 of the 1992 constitution, "Estonian citizens have a duty to participate in national defence on the bases and pursuant to a procedure provided by a law",[289] which in practice means that men aged 18–27 are subject to the draft.[290]

In the formative years, conscripts had to serve an 18-month term. An amendment passed in 1994 shortened this to 12 months. Further revisions in 2003 established an eleven-month term for draftees trained as NCOs and drivers, and an eight-month term for rank & file. Under the current system, the yearly draft is divided into three "waves" – separate batches of eleven-month conscripts start their service in January and July while those selected for an eight-month term are brought in on October.[291] An estimated 3200 people go through conscript service every year.

From 2013, women have been able to voluntarily join the conscription under the same conditions as men, the only difference being the norms of the general fitness tests and a 90-day window during which women can leave the service.[292]

Conscripts serve in all branches of the Estonian Defence Forces except the air force which only relies on paid professionals due to its highly technical nature and security concerns. Historically, draftees could also be assigned to the border guard (before it switched to an all-volunteer model in 2000), a special rapid response unit of the police force (disbanded in 1997) or three militarized rescue companies within the Estonian Rescue Board (disbanded in 2004).

Finland

[edit]

Conscription in Finland is part of a general compulsion for national military service for all adult males (Finnish: maanpuolustusvelvollisuus; Swedish: totalförsvarsplikt) defined in the 127§ of the Constitution of Finland.

Conscription can take the form of military or of civilian service. According to 2021 data, 65%[293] of Finnish males entered and finished the military service. The number of female volunteers to annually enter armed service had stabilised at approximately 300.[294] The service period is 165, 255 or 347 days for the rank and file conscripts and 347 days for conscripts trained as NCOs or reserve officers. The length of civilian service is always twelve months. Those electing to serve unarmed in duties where unarmed service is possible serve either nine or twelve months, depending on their training.[295][296]

Any Finnish male citizen who refuses to perform both military and civilian service faces a penalty of 173 days in prison, minus any served days. Such sentences are usually served fully in prison, with no parole.[297][298] Jehovah's Witnesses are no longer exempted from service as of 27 February 2019.[299] The inhabitants of demilitarized Åland are exempt from military service. By the Conscription Act of 1951, they are, however, required to serve a time at a local institution, like the coast guard. However, until such service has been arranged, they are freed from service obligation. The non-military service of Åland has not been arranged since the introduction of the act, and there are no plans to institute it. The inhabitants of Åland can also volunteer for military service on the mainland. As of 1995, women are permitted to serve on a voluntary basis and pursue careers in the military after their initial voluntary military service.

The military service takes place in Finnish Defence Forces or in the Finnish Border Guard. All services of the Finnish Defence Forces train conscripts. However, the Border Guard trains conscripts only in land-based units, not in coast guard detachments or in the Border Guard Air Wing. Civilian service may take place in the Civilian Service Center in Lapinjärvi or in an accepted non-profit organization of educational, social or medical nature.

France

[edit]Germany

[edit]Between 1956 and 2011 conscription was mandatory for all male citizens in the German federal armed forces (German: Bundeswehr), as well as for the Federal Border Guard (Bundesgrenzschutz) in the 1970s (see Border Guard Service). With the end of the Cold War the German government drastically reduced the size of its armed forces. The low demand for conscripts led to the suspension of compulsory conscription in 2011. Since then, only volunteer professionals serve in the Bundeswehr.

In 2025, Germany began steps towards potentially reintroducing conscription, which had been suspended in 2011. The new policy included compulsory questionnaires for 18-year-old men. Extending the conscription system to women, which is discussed, would require a constitutional change. The government aimes to raise troop numbers to meet NATO commitments, including plans for an additional 100,000 personnel by 2029.[300] However, Defense Minister Boris Pistorius explained that, for the time being, mandatory conscription would not return "in the immediate future."[301]

Greece

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2017) |

Since 1914 Greece has been enforcing mandatory military service, currently lasting 9 months (but historically up to 36 months) for all adult men. Citizens discharged from active service are normally placed in the reserve and are subject to periodic recalls of 1–10 days at irregular intervals.[302]

Universal conscription was introduced in Greece during the military reforms of 1909, although various forms of selective conscription had been in place earlier. In more recent years, conscription was associated with the state of general mobilisation declared on 20 July 1974, due to the crisis in Cyprus (the mobilisation was formally ended on 18 December 2002).

The duration of military service has historically ranged between 9 and 36 months depending on various factors either particular to the conscript or the political situation in the Eastern Mediterranean. Although women are employed by the Greek army as officers and soldiers, they are not obliged to enlist. Soldiers receive no health insurance, but they are provided with medical support during their army service, including hospitalization costs.

Greece enforces conscription for all male citizens aged between 19 and 45. In August 2009, duration of the mandatory service was reduced from 12 months as it was before to 9 months for the army, but remained at 12 months for the navy and the air force. The number of conscripts allocated to the latter two has been greatly reduced aiming at full professionalization. Nevertheless, mandatory military service at the army was once again raised to 12 months in March 2021, unless served in units in Evros or the North Aegean islands where duration was kept at 9 months. Although full professionalization is under consideration, severe financial difficulties and mismanagement, including delays and reduced rates in the hiring of professional soldiers, as well as widespread abuse of the deferment process, has resulted in the postponement of such a plan.

Iran

[edit]

In Iran, all men who reach the age of 18 must do about two years of compulsory military service in the IR police department or Iranian army or Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.[303] Before the 1979 revolution, women could serve in the military.[304] However, after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, some Ayatollahs considered women's military service to be disrespectful to women by the Pahlavi government and banned women's military service in Iran.[305] Therefore, Iranian women and girls were completely exempted from military service, which caused Iranian men and boys to oppose.[306]

In Iran, men who refuse to go to military service are deprived of their citizenship rights, such as employment, health insurance,[307] continuing their education at university,[308] finding a job, going abroad, opening a bank account,[309] etc.[310] Iranian men have so far opposed mandatory military service and demanded that military service in Iran become a job like in other countries, but the Islamic Republic is opposed to this demand.[303] Some Iranian military commanders consider the elimination of conscription or improving the condition of soldiers as a security issue and one of Ali Khamenei's powers as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces,[303][311] so they treat it with caution.[312] In Iran, usually wealthy people are exempted from conscription.[313][314] Some other men can be exempted from conscription due to their fathers serving in the Iran-Iraq war.[315][316]

Israel

[edit]There is a mandatory military service for all men and women in Israel who are fit and 18 years old. Men must serve 32 months while women serve 24 months, with the vast majority of conscripts being Jewish.

Some Israeli citizens are exempt from mandatory service:

- Non-Jewish Arab citizens

- Permanent residents (non-civilian) such as the Druze of the Golan Heights

- Male Ultra-Orthodox Jews can apply for deferment to study in Yeshiva and the deferment tends to become an exemption, although some do opt to serve in the military

- Female religious Jews, as long as they declare they are unable to serve due to religious grounds. Most of whom opt for the alternative of volunteering in the national service Sherut Leumi

All of the exempt above are eligible to volunteer to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), as long as they declare so.

Male Druze and male Circassian Israeli citizens are liable for conscription, in accordance with agreement set by their community leaders (their community leaders however signed a clause in which all female Druze and female Circassian are exempt from service).

A few male Bedouin Israeli citizens choose to enlist to the Israeli military in every draft (despite their Muslim-Arab background that exempt them from conscription).

Lithuania

[edit]Lithuania abolished its conscription in 2008.[317] In May 2015, the Lithuanian parliament voted to reintroduce conscription and the conscripts started their training in August 2015.[318] From 2015 to 2017 there were enough volunteers to avoid drafting civilians.[319]

Luxembourg

[edit]Luxembourg practiced military conscription from 1948 until 1967.

Moldova

[edit]Moldova has a 12-month conscription for all males between 18 and 27 years. However, a citizen who completed a military training course at a military department is exempted from conscription.[320]

Netherlands

[edit]Conscription, which was called "Service Duty" (Dutch: dienstplicht) in the Netherlands, was first employed in 1810 by French occupying forces. Napoleon's brother Louis Bonaparte, who was King of Holland from 1806 to 1810, had tried to introduce conscription a few years earlier, unsuccessfully. Every man aged 20 years or older had to enlist. By means of drawing lots it was decided who had to undertake service in the French army. It was possible to arrange a substitute against payment.

Later on, conscription was used for all men over the age of 18. Postponement was possible, due to study, for example. Conscientious objectors could perform an alternative civilian service instead of military service. For various reasons, this forced military service was criticized at the end of the twentieth century. Since the Cold War was over, so was the direct threat of a war. Instead, the Dutch army was employed in more and more peacekeeping operations. The complexity and danger of these missions made the use of conscripts controversial. Furthermore, the conscription system was thought to be unfair as only men were drafted.

In the European part of Netherlands, compulsory attendance has been officially suspended since 1 May 1997.[321] Between 1991 and 1996, the Dutch armed forces phased out their conscript personnel and converted to an all-professional force. The last conscript troops were inducted in 1995, and demobilized in 1996.[321] The suspension means that citizens are no longer forced to serve in the armed forces, as long as it is not required for the safety of the country. Since then, the Dutch army has become an all-professional force. However, to this day, every male and – from January 2020 onward – female[322] citizen aged 17 gets a letter in which they are told that they have been registered but do not have to present themselves for service.[323]

Norway

[edit]Conscription was constitutionally established the 12 April 1907 with Kongeriket Norges Grunnlov § 119..[324] As of March 2016[update], Norway currently employs a weak form of mandatory military service for men and women. In practice recruits are not forced to serve, instead only those who are motivated are selected.[325] About 60,000 Norwegians are available for conscription every year, but only 8,000 to 10,000 are conscripted.[326] Since 1985, women have been able to enlist for voluntary service as regular recruits. On 14 June 2013 the Norwegian Parliament voted to extend conscription to women, resulting in universal conscription in effect from 2015.[133] This made Norway the first NATO member and first European country to make national service compulsory for both sexes.[327] In earlier times, up until at least the early 2000s, all men aged 19–44 were subject to mandatory service, with good reasons required to avoid becoming drafted. There is a right of conscientious objection. As of 2020 Norway did not reach gender equity in conscription with only 33% of all conscripted being women.[328]

In addition to the military service, the Norwegian government draft a total of 8,000[329] men and women between 18 and 55 to non-military Civil defence duty.[330] (Not to be confused with Alternative civilian service.) Former service in the military does not exclude anyone from later being drafted to the Civil defence, but an upper limit of total 19 months of service applies.[331] Neglecting mobilisation orders to training exercises and actual incidents, may impose fines.[332]

Russia

[edit]The Russian Armed Forces draw personnel from various sources. In addition to conscripts, the 2022 Russian mobilization on account of the Russian invasion of Ukraine revealed Russian irregular units in Ukraine and Russian penal military units as sources of manpower. This adds to the BARS (Russia), the National Guard of Russia and the Russian volunteer battalions.

Serbia

[edit]As of 1 January 2011[update], Serbia no longer practises mandatory military service. Prior to this, mandatory military service lasted 6 months for men. Conscientious objectors could however opt for 9 months of civil service instead.

On 15 December 2010, the Parliament of Serbia voted to suspend mandatory military service. The decision fully came into force on 1 January 2011.[333]

In September 2024, Prime Minister Miloš Vučević announced that conscription will return in September 2025 with the mandatory military service lasting 75 days.[234] Civil service will still be possible as an alternative.[334]

Singapore

[edit]South Africa

[edit]There was mandatory military conscription for all white men in South Africa from 1968 until the end of apartheid in 1994.[335] Under South African defense law, young white men had to undergo two years' continuous military training after they leave school, after which they had to serve 720 days in occasional military duty over the next 12 years.[336] The End Conscription Campaign began in 1983 in opposition to the requirement. In the same year the National Party government announced plans to extend conscription to white immigrants in the country.[336]

South Korea

[edit]Sweden

[edit]

Sweden had conscription (Swedish: värnplikt) for men between 1901 and 2010. During the last few decades it was selective.[337] Since 1980, women have been allowed to sign up by choice, and, if passing the tests, do military training together with male conscripts. Since 1989 women have been allowed to serve in all military positions and units, including combat.[136]

In 2010, conscription was made gender-neutral, meaning both women and men would be conscripted on equal terms. The conscription system was simultaneously deactivated in peacetime.[136] Seven years later, referencing increased military threat, the Swedish Government reactivated military conscription. Beginning in 2018, both men and women are conscripted.[136]

Taiwan

[edit]Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), maintains an active conscription system. All qualified male citizens of military age are now obligated to receive 4-month of military training. In December 2022, President Tsai Ing-wen led the government to announce the reinstatement of the mandatory 1-year active duty military service from January 2024.[338]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom introduced conscription to full-time military service for the first time in January 1916 (the eighteenth month of World War I) and abolished it in 1920. Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom, was exempted from the original 1916 military service legislation, and although further legislation in 1918 gave power for an extension of conscription to Ireland, the power was never put into effect.

Conscription was reintroduced in 1939, in the lead up to World War II, and continued in force until 1963. Northern Ireland was exempted from conscription legislation throughout the whole period.

In all, eight million men were conscripted during both World Wars, as well as several hundred thousand younger single women.[339] The introduction of conscription in May 1939, before the war began, was partly due to pressure from the French, who emphasized the need for a large British army to oppose the Germans.[340] From early 1942 unmarried women age 20–30 were conscripted (unmarried women who had dependent children aged 14 or younger, including those who had illegitimate children or were widows with children were excluded). Most women who were conscripted were sent to the factories, but they could volunteer for the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) and other women's services. Some women served in the Women's Land Army: initially volunteers but later conscription was introduced. However, women who were already working in a skilled job considered helpful to the war effort, such as a General Post Office telephonist, were told to continue working as before. None was assigned to combat roles unless she volunteered. By 1943 women were liable to some form of directed labour up to age 51. During the Second World War, 1.4 million British men volunteered for service and 3.2 million were conscripted. Conscripts comprised 50% of the Royal Air Force, 60% of the Royal Navy and 80% of the British Army.[149]

The abolition of conscription in Britain was announced on 4 April 1957, by new prime minister Harold Macmillan, with the last conscripts being recruited three years later.[341]

United States

[edit]Conscription in the United States ended in 1973, but males aged between 18 and 25 are required to register with the Selective Service System to enable a reintroduction of conscription if necessary. President Gerald Ford had suspended mandatory draft registration in 1975, but President Jimmy Carter reinstated that requirement when the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan five years later. Consequently, Selective Service registration is still required of almost all young men.[342] There have been no prosecutions for violations of the draft registration law since 1986.[343] Males between the ages of 17 and 45, and female members of the US National Guard may be conscripted for federal militia service pursuant to 10 U.S. Code § 246 and the Militia Clauses of the United States Constitution.[344]

In February 2019, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas ruled that male-only conscription registration breached the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause. In National Coalition for Men v. Selective Service System, a case brought by a non-profit men's rights organization the National Coalition for Men against the U.S. Selective Service System, judge Gray H. Miller issued a declaratory judgment that the male-only registration requirement is unconstitutional, though did not specify what action the government should take.[345] That ruling was reversed by the Fifth Circuit. In June 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the decision by the Court of Appeals.

Other countries

[edit]- Conscription in Australia

- Conscription in Egypt

- Conscription in France

- Conscription in Gibraltar

- Conscription in Malaysia

- Conscription in Mexico

- Conscription in Myanmar

- Conscription in New Zealand

- Conscription in North Korea

- Conscription in Russia

- Conscription in Singapore

- Conscription in South Korea

- Conscription in Switzerland

- Conscription in Turkey

- Conscription in Ukraine

- Conscription in the Ottoman Empire

- Conscription in the Russian Empire

- Conscription in Vietnam

- Conscription in Georgia

- Conscription in Mozambique

See also

[edit]- Civil conscription

- Civilian Public Service

- Corvée

- Counter-recruitment

- Draft evasion

- Economic conscription

- End Conscription Campaign

- Home front during World War I

- Home front during World War II

- Labour battalion

- List of countries by number of military and paramilitary personnel

- Male expendability

- Military recruitment

- No Conscription Campaign

- No-Conscription Fellowship

- Pospolite ruszenie, mass mobilization in Poland

- Quota System

- Timeline of women's participation in warfare

- War resister

References

[edit]- ^ "Conscription". Merriam-Webster Online. 13 September 2023.

- ^ McIntosh, Matthew (2018-02-08). "A History of Military Conscription in Europe". Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas. Retrieved 2025-06-09.

- ^ "Seeking Sanctuary: Draft Dodgers". CBC Digital Archives.

- ^ "World War II". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Historica Canada. 15 July 2015.

- ^ a b Asal, Victor; Conrad, Justin; Toronto, Nathan (2017-08-01). "I Want You! The Determinants of Military Conscription". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 61 (7): 1456–1481. doi:10.1177/0022002715606217. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 9019768.

- ^ Postgate, J.N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 0-415-11032-7.

- ^ Postgate, J.N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge. p. 243. ISBN 0-415-11032-7.

- ^ "arrière-ban". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ Nicolle, D. (2000). French Armies of the Hundred Years' War (Vol. 337). Osprey Publishing.

- ^ Nicolle, D. (2004). Poitiers 1356: The capture of a king (Vol. 138). Osprey Publishing.

- ^ Curry, A. (2002). Essential Histories–The Hundred Years' War. Nova York, Osprey.

- ^ Williams, D. G. E. (1997-01-01). "The Dating of the Norwegian leiðangr System: A Philological Approach". NOWELE. North-Western European Language Evolution. 30 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1075/nowele.30.02wil. ISSN 0108-8416.

- ^ Attenborough, F. L. (1974) [1922]. Laws of the Earliest English Kings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780404565459.

- ^ Sturdy, David Alfred the Great Constable (1995), p. 153