Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Apollo command and service module

View on Wikipedia

Apollo CSM Endeavour in lunar orbit during Apollo 15 | |||

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Designer | Maxime Faget | ||

| Country of origin | United States | ||

| Operator | NASA | ||

| Applications | Crewed cislunar flight and lunar orbit Skylab crew shuttle Apollo–Soyuz Test Project | ||

| Specifications | |||

| Spacecraft type | Capsule | ||

| Launch mass | 32,390 lb (14,690 kg) Earth orbit 63,500 lb (28,800 kg) Lunar | ||

| Dry mass | 26,300 lb (11,900 kg) | ||

| Payload capacity | 2,320 lb (1,050 kg) | ||

| Crew capacity | 3 | ||

| Volume | 218 cu ft (6.2 m3) | ||

| Power | 3 × 1.4 kW, 30 V DC fuel cells | ||

| Batteries | 3 × 40 ampere-hour silver zinc battery | ||

| Regime | Low Earth orbit Cislunar space Lunar orbit | ||

| Design life | 14 days | ||

| Dimensions | |||

| Length | 36.2 ft (11.0 m) | ||

| Diameter | 12.8 ft (3.9 m) | ||

| Production | |||

| Status | Retired | ||

| Built | 35 | ||

| Launched | 19 | ||

| Operational | 19 | ||

| Failed | 2 | ||

| Lost | 1 | ||

| Maiden launch | February 26, 1966 (AS-201) | ||

| Last launch | July 15, 1975 (Apollo–Soyuz) | ||

| Last retirement | July 24, 1975 | ||

| Service Propulsion System | |||

| Powered by | 1 × AJ10-137[1] | ||

| Maximum thrust | 91.19 kN (20,500 lbf) | ||

| Specific impulse | 314.5 s (3.084 km/s) | ||

| Burn time | 750 s | ||

| Propellant | N2O4/Aerozine 50 | ||

| Related spacecraft | |||

| Flown with | Apollo Lunar Module | ||

| Configuration | |||

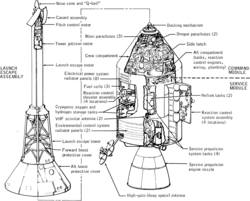

Apollo Block II CSM diagram

| |||

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functioned as a mother ship, which carried a crew of three astronauts and the second Apollo spacecraft, the Apollo Lunar Module, to lunar orbit, and brought the astronauts back to Earth. It consisted of two parts: the conical command module, a cabin that housed the crew and carried equipment needed for atmospheric reentry and splashdown; and the cylindrical service module which provided propulsion, electrical power and storage for various consumables required during a mission. An umbilical connection transferred power and consumables between the two modules. Just before reentry of the command module on the return home, the umbilical connection was severed and the service module was cast off and allowed to burn up in the atmosphere.

The CSM was developed and built for NASA by North American Aviation starting in November 1961. It was initially designed to land on the Moon atop a landing rocket stage and return all three astronauts on a direct-ascent mission, which would not use a separate lunar module, and thus had no provisions for docking with another spacecraft. This, plus other required design changes, led to the decision to design two versions of the CSM: Block I was to be used for uncrewed missions and a single crewed Earth orbit flight (Apollo 1), while the more advanced Block II was designed for use with the lunar module. The Apollo 1 flight was cancelled after a cabin fire killed the crew and destroyed their command module during a launch rehearsal test. Corrections of the problems which caused the fire were applied to the Block II spacecraft, which was used for all crewed spaceflights.

Nineteen CSMs were launched into space. Of these, nine flew humans to the Moon between 1968 and 1972, and another two performed crewed test flights in low Earth orbit, all as part of the Apollo program. Before these, another four CSMs had flown as uncrewed Apollo tests, of which two were suborbital flights and another two were orbital flights. Following the conclusion of the Apollo program and during 1973–1974, three CSMs ferried astronauts to the orbital Skylab space station. Finally in 1975, the last flown CSM docked with the Soviet craft Soyuz 19 as part of the international Apollo–Soyuz Test Project.

Before Apollo

[edit]Concepts of an advanced crewed spacecraft started before the Moon landing goal was announced. The three-person vehicle was to be mainly for orbital use around Earth. It would include a large pressurized auxiliary orbital module where the crew would live and work for weeks at a time. They would perform space station-type activities in the module, while later versions would use the module to carry cargo to space stations. The spacecraft was to service the Project Olympus (LORL), a foldable rotating space station launched on a single Saturn V. Later versions would be used on circumlunar flights, and would be the basis for a direct ascent lunar spacecraft as well as used on interplanetary missions. In late 1960, NASA called on U.S. industry to propose designs for the vehicle. On May 25, 1961 President John F. Kennedy announced the Moon landing goal before 1970, which immediately rendered NASA's Olympus Station plans obsolete.[2][3]

Development history

[edit]When NASA awarded the initial Apollo contract to North American Aviation on November 28, 1961, it was still assumed the lunar landing would be achieved by direct ascent rather than by lunar orbit rendezvous.[4] Therefore, design proceeded without a means of docking the command module to a lunar excursion module (LEM). But the change to lunar orbit rendezvous, plus several technical obstacles encountered in some subsystems (such as environmental control), soon made it clear that substantial redesign would be required. In 1963, NASA decided the most efficient way to keep the program on track was to proceed with the development in two versions:[5]

- Block I would continue the preliminary design, to be used for early low Earth orbit test flights only.

- Block II would be the lunar-capable version, including a docking hatch and incorporating weight reduction and lessons learned in Block I. Detailed design of the docking capability depended on design of the LEM, which was contracted to Grumman Aircraft Engineering.

By January 1964, North American started presenting Block II design details to NASA.[6] Block I spacecraft were used for all uncrewed Saturn 1B and Saturn V test flights. Initially two crewed flights were planned, but this was reduced to one in late 1966. This mission, designated AS-204 but named Apollo 1 by its flight crew, was planned for launch on February 21, 1967. During a dress rehearsal for the launch on January 27, all three astronauts (Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee) were killed in a cabin fire, which revealed serious design, construction and maintenance shortcomings in Block I, many of which had been carried over into Block II command modules being built at the time.[citation needed]

After a thorough investigation by the Apollo 204 Review Board, it was decided to terminate the crewed Block I phase and redefine Block II to incorporate the review board's recommendations. Block II incorporated a revised CM heat shield design, which was tested on the uncrewed Apollo 4 and Apollo 6 flights, so the first all-up Block II spacecraft flew on the first crewed mission, Apollo 7.[citation needed]

The two blocks were essentially similar in overall dimensions, but several design improvements resulted in weight reduction in Block II. Also, the Block I service module propellant tanks were slightly larger than in Block II. The Apollo 1 spacecraft weighed approximately 45,000 pounds (20,000 kg), while the Block II Apollo 7 weighed 36,400 lb (16,500 kg). (These two Earth orbital craft were lighter than the craft which later went to the Moon, as they carried propellant in only one set of tanks, and did not carry the high-gain S-band antenna.) In the specifications given below, unless otherwise noted, all weights given are for the Block II spacecraft.[citation needed]

The total cost of the CSM for development and the units produced was $36.9 billion in 2016 dollars, adjusted from a nominal total of $3.7 billion[7] using the NASA New Start Inflation Indices.[8]

Command module (CM)

[edit]

The command module was a truncated cone (frustum) with a diameter of 12 feet 10 inches (3.91 m) across the base, and a height of 11 feet 5 inches (3.48 m) including the docking probe and dish-shaped aft heat shield. The forward compartment contained two reaction control system thrusters, the docking tunnel, and the Earth Landing System. The inner pressure vessel housed the crew accommodation, equipment bays, controls and displays, and many spacecraft systems. The aft compartment contained 10 reaction control engines and their related propellant tanks, freshwater tanks, and the CSM umbilical cables.[9]

Construction

[edit]The command module was built in North American's factory in Downey, California,[10][11] and consisted of two basic structures joined together: the inner structure (pressure shell) and the outer structure.[citation needed]

The inner structure was an aluminum sandwich construction consisting of a welded aluminum inner skin, adhesively bonded aluminum honeycomb core, and outer face sheet. The thickness of the honeycomb varied from about 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) at the base to about 0.25 inches (0.64 cm) at the forward access tunnel. This inner structure was the pressurized crew compartment.[citation needed]

The outer structure was made of stainless steel brazed-honeycomb brazed between steel alloy face sheets. It varied in thickness from 0.5 inch to 2.5 inches. Part of the area between the inner and outer shells was filled with a layer of fiberglass insulation as additional heat protection.[12]

Thermal protection (heat shield)

[edit]

An ablative heat shield on the outside of the CM protected the capsule from the heat of reentry, which is sufficient to melt most metals. This heat shield was composed of phenolic formaldehyde resin. During reentry, this material charred and melted away, absorbing and carrying away the intense heat in the process. The heat shield has several outer coverings: a pore seal, a moisture barrier (a white reflective coating), and a silver Mylar thermal coating that looks like aluminum foil.[citation needed]

The heat shield varied in thickness from 2 inches (5.1 cm) in the aft portion (the base of the capsule, which faced forward during reentry) to 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) in the crew compartment and forward portions. The total weight of the shield was about 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg).[12]

Forward compartment

[edit]The 1-foot-11-inch (0.58 m)-tall forward compartment was the area outside the inner pressure shell in the nose of the capsule, located around the forward docking tunnel and covered by the forward heat shield. The compartment was divided into four 90-degree segments that contained Earth landing equipment (all the parachutes, recovery antennas and beacon light, and sea recovery sling), two reaction control thrusters, and the forward heat shield release mechanism.[citation needed]

At about 25,000 feet (7,600 m) during reentry, the forward heat shield was jettisoned to expose the Earth landing equipment and permit deployment of the parachutes.[12]

Aft compartment

[edit]The 1-foot-8-inch (0.51 m)-tall aft compartment was located around the periphery of the command module at its widest part, just forward of (above) the aft heat shield. The compartment was divided into 24 bays containing 10 reaction control engines; the fuel, oxidizer, and helium tanks for the CM reaction control subsystem; water tanks; the crushable ribs of the impact attenuation system; and a number of instruments. The CM-SM umbilical, the point where wiring and plumbing ran from one module to the other, was also in the aft compartment. The panels of the heat shield covering the aft compartment were removable for maintenance of the equipment before flight.[12]

Earth landing system

[edit]

The components of the ELS were housed around the forward docking tunnel. The forward compartment was separated from the central by a bulkhead and was divided into four 90-degree wedges. The ELS consisted of two drogue parachutes with mortars, three main parachutes, three pilot parachutes to deploy the mains, three inflation bags for uprighting the capsule if necessary, a sea recovery cable, a dye marker, and a swimmer umbilical.[citation needed]

The command module's center of mass was offset a foot or so from the center of pressure (along the symmetry axis). This provided a rotational moment during reentry, angling the capsule and providing some lift (a lift to drag ratio of about 0.368).[13] The capsule was then steered by rotating the capsule using thrusters; when no steering was required, the capsule was spun slowly, and the lift effects cancelled out. This system greatly reduced the g-force experienced by the astronauts, permitted a reasonable amount of directional control and allowed the capsule's splashdown point to be targeted within a few miles.[citation needed]

At 24,000 feet (7,300 m), the forward heat shield was jettisoned using four pressurized-gas compression springs. The drogue parachutes were then deployed, slowing the spacecraft to 125 miles per hour (201 kilometres per hour). At 10,700 feet (3,300 m) the drogues were jettisoned and the pilot parachutes, which pulled out the mains, were deployed. These slowed the CM to 22 miles per hour (35 kilometres per hour) for splashdown. The portion of the capsule that first contacted the water surface contained four crushable ribs to further mitigate the force of impact. The command module could safely parachute to an ocean landing with only two parachutes deployed (as occurred on Apollo 15), the third parachute being a safety precaution.[citation needed]

Reaction control system

[edit]The command module attitude control system consisted of twelve 93-pound-force (410 N) attitude control thrusters, ten of which were located in the aft compartment, plus two in the forward compartment. These were supplied by four tanks storing 270 pounds (120 kg) of monomethylhydrazine fuel and nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer, and pressurized by 1.1 pounds (0.50 kg) of helium stored at 4,150 pounds per square inch (28.6 MPa) in two tanks.[citation needed]

Hatches

[edit]The forward docking hatch was mounted at the top of the docking tunnel. It was 30 inches (76 cm) in diameter and weighed 80 pounds (36 kg), constructed from two machined rings that were weld-joined to a brazed honeycomb panel. The exterior side was covered with 0.5-inch (13 mm) of insulation and a layer of aluminum foil. It was latched in six places and operated by a pump handle. The hatch contained a valve in its center, used to equalize the pressure between the tunnel and the CM so the hatch could be removed.[citation needed]

The unified crew hatch (UCH) measured 29 inches (74 cm) high, 34 inches (86 cm) wide, and weighed 225 pounds (102 kg). It was operated by a pump handle, which drove a ratchet mechanism to open or close fifteen latches simultaneously.[citation needed]

Docking assembly

[edit]Apollo's mission required the LM to dock with the CSM on return from the Moon, and also in the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver at the beginning of the translunar coast. The docking mechanism was a non-androgynous system, consisting of a probe located in the nose of the CSM, which connected to the drogue, a truncated cone located on the lunar module. The probe was extended like a scissor jack to capture the drogue on initial contact, known as soft docking. Then the probe was retracted to pull the vehicles together and establish a firm connection, known as "hard docking". The mechanism was specified by NASA to have the following functions:[citation needed]

- Allow the two vehicles to connect, and attenuate excess movement and energy caused by docking

- Align and center the two vehicles and pull them together for capture

- Provide a rigid structural connection between both vehicles, and be capable of removal and re-installation by a single crewman

- Provide a means of remote separation of both vehicles for the return to Earth, using pyrotechnic fasteners at the circumference of the CSM docking collar

- Provide redundant power and logic circuits for all electrical and pyrotechnic components.[citation needed]

Coupling

[edit]The probe head located in the CSM was self-centering and gimbal-mounted to the probe piston. As the probe head engaged in the opening of the drogue socket, three spring-loaded latches depressed and engaged. These latches allowed a so-called 'soft dock' state and enabled the pitch and yaw movements in the two vehicles to subside. Excess movement in the vehicles during the 'hard dock' process could cause damage to the docking ring and put stress on the upper tunnel. A depressed locking trigger link at each latch allowed a spring-loaded spool to move forward, maintaining the toggle linkage in an over-center locked position. In the upper end of the lunar module tunnel, the drogue, which was constructed of 1-inch-thick aluminum honeycomb core, bonded front and back to aluminum face sheets, was the receiving end of the probe head capture latches.[citation needed]

Retraction

[edit]After the initial capture and stabilization of the vehicles, the probe was capable of exerting a closing force of 1,000 pounds-force (4.4 kN) to draw the vehicles together. This force was generated by gas pressure acting on the center piston within the probe cylinder. Piston retraction compressed the probe and interface seals and actuated the 12 automatic ring latches which were located radially around the inner surface of the CSM docking ring. The latches were manually re-cocked in the docking tunnel by an astronaut after each hard docking event (lunar missions required two dockings).[citation needed]

Separation

[edit]An automatic extension latch attached to the probe cylinder body engaged and retained the probe center piston in the retracted position. Before vehicle separation in lunar orbit, manual cocking of the twelve ring latches was accomplished. The separating force from the internal pressure in the tunnel area was then transmitted from the ring latches to the probe and drogue. In undocking, the release of the capture latches was accomplished by electrically energizing tandem-mounted DC rotary solenoids located in the center piston. In a temperature degraded condition, a single motor release operation was done manually in the lunar module by depressing the locking spool through an open hole in the probe heads, while release from the CSM was done by rotating a release handle at the back of the probe to rotate the motor torque shaft manually.[14] When the command and lunar modules separated for the last time, the probe and forward docking ring were pyrotechnically separated, leaving all docking equipment attached to the lunar module. In the event of an abort during launch from Earth, the same system would have explosively jettisoned the docking ring and probe from the CM as it separated from the boost protective cover.[citation needed]

Cabin interior arrangement

[edit]

The central pressure vessel of the command module was its sole habitable compartment. It had an interior volume of 210 cubic feet (5.9 m3) and housed the main control panels, crew seats, guidance and navigation systems, food and equipment lockers, the waste management system, and the docking tunnel.

Dominating the forward section of the cabin was the crescent-shaped main display panel measuring nearly 7 feet (2.1 m) wide and 3 feet (0.91 m) tall. It was arranged into three panels, each emphasizing the duties of each crew member. The mission commander's panel (left side) included the velocity, attitude, and altitude indicators, the primary flight controls, and the main FDAI (Flight Director Attitude Indicator).

The CM pilot served as navigator, so his control panel (center) included the Guidance and Navigation computer controls, the caution and warning indicator panel, the event timer, the Service Propulsion System and RCS controls, and the environmental control system controls.

The LM pilot served as systems engineer, so his control panel (right-hand side) included the fuel cell gauges and controls, the electrical and battery controls, and the communications controls.

Flanking the sides of the main panel were sets of smaller control panels. On the left side were a circuit breaker panel, audio controls, and the SCS power controls. On the right were additional circuit breakers and a redundant audio control panel, along with the environmental control switches. In total, the command module panels included 24 instruments, 566 switches, 40 event indicators, and 71 lights.

The three crew couches were constructed from hollow steel tubing and covered in a heavy, fireproof cloth known as Armalon. The leg pans of the two outer couches could be folded in a variety of positions, while the hip pan of the center couch could be disconnected and laid on the aft bulkhead. One rotation and one translation hand controller was installed on the armrests of the left-hand couch. The translation controller was used by the crew member performing the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver with the LM, usually the CM Pilot. The center and right-hand couches had duplicate rotational controllers. The couches were supported by eight shock-attenuating struts, designed to ease the impact of touchdown on water or, in case of an emergency landing, on solid ground.

The contiguous cabin space was organized into six equipment bays:

- The lower equipment bay, which housed the Guidance and Navigation computer, sextant, telescope, and Inertial Measurement Unit; various communications beacons; medical stores; an audio center; the S-band power amplifier; etc. There was also an extra rotation hand controller mounted on the bay wall, so the CM Pilot/navigator could rotate the spacecraft as needed while standing and looking through the telescope to find stars to take navigational measurements with the sextant. This bay provided a significant amount of room for the astronauts to move around in, unlike the cramped conditions which existed in the previous Mercury and Gemini spacecraft.

- The left-hand forward equipment bay, which contained four food storage compartments, the cabin heat exchanger, pressure suit connector, potable water supply, and G&N telescope eyepieces.

- The right-hand forward equipment bay, which housed two survival kit containers, a data card kit, flight data books and files, and other mission documentation.

- The left hand intermediate equipment bay, housing the oxygen surge tank, water delivery system, food supplies, the cabin pressure relief valve controls, and the ECS package.

- The right hand intermediate equipment bay, which contained the bio instrument kits, waste management system, food and sanitary supplies, and a waste storage compartment.

- The aft storage bay, behind the crew couches. This housed the 70 mm camera equipment, the astronaut's garments, tool sets, storage bags, a fire extinguisher, CO2 absorbers, sleep restraint ropes, spacesuit maintenance kits, 16mm camera equipment, and the contingency lunar sample container.

The CM had five windows. The two side windows measured 9 inches (23 cm) square next to the left and right-hand couches. Two forward-facing triangular rendezvous windows measured 8 by 9 inches (20 by 23 cm), used to aid in rendezvous and docking with the LM. The circular hatch window was 9 inches (23 cm) in diameter located directly over the center couch. Each window assembly consisted of three thick panes of glass. The inner two panes, which were made of aluminosilicate, made up part of the module's pressure vessel. The fused silica outer pane served as both a debris shield and as part of the heat shield. Each pane had an anti-reflective coating and a blue-red reflective coating on the inner surface.

Specifications

[edit]

- Crew: 3

- Crew cabin volume: 210 cu ft (5.9 m3) living space, pressurized 366 cu ft (10.4 m3)

- Length: 11.4 ft (3.5 m)

- Diameter: 12.8 ft (3.9 m)

- Mass: 12,250 lb (5,560 kg)

- Structure mass: 3,450 lb (1,560 kg)

- Heat shield mass: 1,869 lb (848 kg)

- RCS engine mass: 12 × 73.3 lb (33.2 kg)

- Recovery equipment mass: 540 lb (240 kg)

- Navigation equipment mass: 1,113 lb (505 kg)

- Telemetry equipment mass: 440 lb (200 kg)

- Electrical equipment mass: 1,540 lb (700 kg)

- Communications systems mass: 220 lb (100 kg)

- Crew couches and provisions mass: 1,210 lb (550 kg)

- Environmental Control System mass: 440 lb (200 kg)

- Misc. contingency mass: 440 lb (200 kg)

- RCS: twelve 93 lbf (410 N) thrusters, firing in pairs

- RCS propellants: MMH/N

2O

4 - RCS propellant mass: 270 lb (120 kg)

- Drinking water capacity: 33 lb (15 kg)

- Waste water capacity: 58 lb (26 kg)

- CO2 scrubber: lithium hydroxide

- Odor absorber: activated charcoal

- Electric system batteries: three 40 ampere-hour silver-zinc batteries; two 0.75 ampere-hour silver-zinc pyrotechnic batteries

- Parachutes: two 16.5-foot (5.0 m) conical ribbon drogue parachutes; three 7.2-foot (2.2 m) ringslot pilot parachutes; three 83.5-foot (25.5 m) ringsail main parachutes[15]

Service module (SM)

[edit]

Construction

[edit]The service module was an unpressurized cylindrical structure with a diameter of 12 feet 10 inches (3.91 m) and 14 feet 10 inches (4.52 m) long. The service propulsion engine nozzle and heat shield increased the total height to 24 feet 7 inches (7.49 m). The interior was a simple structure consisting of a central tunnel section 44 inches (1.1 m) in diameter, surrounded by six pie-shaped sectors. The sectors were topped by a forward bulkhead and fairing, separated by six radial beams, covered on the outside by four honeycomb panels, and supported by an aft bulkhead and engine heat shield. The sectors were not all equal 60° angles, but varied according to required size.

- Sector 1 (50°) was originally unused, so it was filled with ballast to maintain the SM's center-of gravity.

- On the last three lunar landing (I-J class) missions, it carried the scientific instrument module (SIM) with a powerful Itek 24 inches (610 mm) focal length camera originally developed for the Lockheed U-2 and SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft. The camera photographed the Moon; had the S-IVB failed to fire causing the CSM to not leave earth orbit, astronauts would have used it to photograph the Earth.[18][19] SIM also had other sensors and a subsatellite.

- Sector 2 (70°) contained the service propulsion system (SPS) oxidizer sump tank, so called because it directly fed the engine and was kept continuously filled by a separate storage tank, until the latter was empty. The sump tank was a cylinder with hemispherical ends, 153.8 inches (3.91 m) high, 51 inches (1.3 m) in diameter, and contained 13,923 pounds (6,315 kg) of oxidizer. Its total volume was 161.48 cu ft (4.573 m3)

- Sector 3 (60°) contained the SPS oxidizer storage tank, which was the same shape as the sump tank but slightly smaller at 154.47 inches (3.924 m) high and 44 inches (1.1 m) in diameter, and held 11,284 pounds (5,118 kg) of oxidizer. Its total volume was 128.52 cu ft (3.639 m3)

- Sector 4 (50°) contained the electrical power system (EPS) fuel cells with their hydrogen and oxygen reactants.

- Sector 5 (70°) contained the SPS fuel sump tank. This was the same size as the oxidizer sump tank and held 8,708 pounds (3,950 kg) of fuel.

- Sector 6 (60°) contained the SPS fuel storage tank, also the same size as the oxidizer storage tank. It held 7,058 pounds (3,201 kg) of fuel.

The forward fairing measured 1 foot 11 inches (58 cm) long and housed the reaction control system (RCS) computer, power distribution block, ECS controller, separation controller, and components for the high-gain antenna, and included eight EPS radiators and the umbilical connection arm containing the main electrical and plumbing connections to the CM. The fairing externally contained a retractable forward-facing spotlight; an EVA floodlight to aid the command module pilot in SIM film retrieval; and a flashing rendezvous beacon visible from 54 nautical miles (100 km) away as a navigation aid for rendezvous with the LM.

The SM was connected to the CM using three tension ties and six compression pads. The tension ties were stainless steel straps bolted to the CM's aft heat shield. It remained attached to the command module throughout most of the mission, until being jettisoned just prior to re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. At jettison, the CM umbilical connections were cut using a pyrotechnic-activated guillotine assembly. Following jettison, the SM aft translation thrusters automatically fired continuously to distance it from the CM, until either the RCS fuel or the fuel cell power was depleted. The roll thrusters were also fired for five seconds to make sure it followed a different trajectory from the CM and faster break-up on re-entry.

Service propulsion system

[edit]

The service propulsion system (SPS) engine was originally designed to lift the CSM off the surface of the Moon in the direct ascent mission mode,[20] The engine selected was the AJ10-137,[21] which used Aerozine 50 as fuel and nitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) as oxidizer to produce 20,500 lbf (91 kN) of thrust.[22] A contract was signed in April 1962 for the Aerojet-General company to start developing the engine, resulting in a thrust level twice what was needed to accomplish the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) mission mode officially chosen in July of that year.[23] The engine was actually used for mid-course corrections between the Earth and Moon, and to place the spacecraft into and out of lunar orbit. It also served as a retrorocket to perform the deorbit burn for Earth orbital flights.

The propellants were pressure-fed to the engine by 39.2 cubic feet (1.11 m3) of gaseous helium at 3,600 pounds per square inch (25 MPa), carried in two 40-inch (1.0 m) diameter spherical tanks.[24]

The exhaust nozzle measured 152.82 inches (3.882 m) long and 98.48 inches (2.501 m) wide at the base. It was mounted on two gimbals to keep the thrust vector aligned with the spacecraft's center of mass during SPS firings. The combustion chamber and pressurant tanks were housed in the central tunnel.

Reaction control system

[edit]

Four clusters of four reaction control system (RCS) thrusters (known as "quads") were installed around the upper section of the SM every 90°. The sixteen-thruster arrangement provided rotation and translation control in all three spacecraft axes. Each R-4D thruster measured 12 inches (30 cm) long by 6 inches (15 cm) diameter, generated 100 pounds-force (440 N) of thrust, and used helium-fed monomethylhydrazine (MMH) as fuel and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) as oxidizer.[25] Each quad assembly measured 2.2 by 2.7 feet (0.67 by 0.82 m) and had its own fuel, oxidizer, and helium tanks mounted on the inside of an 8-by-2.75-foot (2.44 by 0.84 m) skin panel. The primary fuel (MMH) tank contained 69.1 pounds (31.3 kg); the secondary fuel tank contained 45.2 pounds (20.5 kg); the primary oxidizer tank contained 137.0 pounds (62.1 kg), and the secondary oxidizer tank contained 89.2 pounds (40.5 kg). The propellant tanks were pressurized from a single tank containing 1.35 pounds (0.61 kg) of liquid helium.[26] Back flow was prevented by a series of check valves, and back flow and ullage requirements were resolved by containing the fuel and oxidizer in Teflon bladders which separated the propellants from the helium pressurant.[26]

The four completely independent RCS clusters provided redundancy; only two adjacent functioning units were needed to allow complete attitude control.[26]

The lunar module used a similar four-quad arrangement of R-4D thruster engines for its RCS.

Electrical power system

[edit]

Electrical power was produced by three fuel cells, each measuring 44 inches (1.1 m) tall by 22 inches (0.56 m) in diameter and weighing 245 pounds (111 kg). These combined hydrogen and oxygen to generate electrical power, and produced drinkable water as a byproduct. The cells were fed by two hemispherical-cylindrical 31.75-inch (0.806 m) diameter tanks, each holding 29 pounds (13 kg) of liquid hydrogen, and two spherical 26-inch (0.66 m) diameter tanks, each holding 326 pounds (148 kg) of liquid oxygen (which also supplied the environmental control system).

On the flight of Apollo 13, the EPS was disabled by an explosive rupture of one oxygen tank, which punctured the second tank and led to the loss of all oxygen. After the accident, a third oxygen tank was added to obviate operation below 50% tank capacity. That allowed the elimination of the tank's internal stirring-fan equipment, which had contributed to the failure.

Also starting with Apollo 14, a 400 Ah auxiliary battery was added to the SM for emergency use. Apollo 13 had drawn heavily on its entry batteries in the first hours after the explosion, and while this new battery could not power the CM for more than 5–10 hours it would buy time in the event of a temporary loss of all three fuel cells. Such an event had occurred when Apollo 12 was struck twice by lightning during launch.

Environmental control system

[edit]Cabin atmosphere was maintained at 5 pounds per square inch (34 kPa) of pure oxygen from the same liquid oxygen tanks that fed the electrical power system's fuel cells. Potable water supplied by the fuel cells was stored for drinking and food preparation. A thermal control system using a mixture of water and ethylene glycol as coolant dumped waste heat from the CM cabin and electronics to outer space via two 30-square-foot (2.8 m2) radiators located on the lower section of the exterior walls, one covering sectors 2 and 3 and the other covering sectors 5 and 6.[27]

Communications system

[edit]

Short-range communications between the CSM and LM employed two VHF scimitar antennas mounted on the SM just above the ECS radiators. These antennas were originally located on the Block I command module and performed a double function as aerodynamic strakes to stabilize the capsule after a launch abort. The antennas were moved to the Block II service module when this function was found unnecessary.

A steerable unified S-band high-gain antenna for long-range communications with Earth was mounted on the aft bulkhead. This was an array of four 31-inch (0.79 m) diameter reflectors surrounding a single 11-inch (0.28 m) square reflector. During launch it was folded down parallel to the main engine to fit inside the Spacecraft-to-LM Adapter (SLA). After CSM separation from the SLA, it deployed at a right angle to the SM.

Four omnidirectional S-band antennas on the CM were used when the attitude of the CSM kept the high-gain antenna from being pointed at Earth. These antennas were also used between SM jettison and landing.[28]

Specifications

[edit]- Length: 24.8 ft (7.6 m)

- Diameter: 12.8 ft (3.9 m)

- Mass: 54,060 lb (24,520 kg)

- Structure mass: 4,200 lb (1,900 kg)

- Electrical equipment mass: 2,600 lb (1,200 kg)

- Service Propulsion (SPS) engine mass: 6,600 lb (3,000 kg)

- SPS engine propellants: 40,590 lb (18,410 kg)

- RCS thrust: 2 or 4 × 100 lbf (440 N)

- RCS propellants: MMH/N

2O

4 - SPS engine thrust: 20,500 lbf (91,000 N)

- SPS engine propellants: (UDMH/N

2H

4)/N

2O

4 - SPS Isp: 314 s (3,100 N·s/kg)

- Spacecraft delta-v: 9,200 ft/s (2,800 m/s)

- Electrical system: three 1.4 kW 30 V DC fuel cells

Modifications for Saturn IB missions

[edit]

The payload capability of the Saturn IB launch vehicle used to launch the Low Earth Orbit missions (Apollo 1 (planned), Apollo 7, Skylab 2, Skylab 3, Skylab 4, and Apollo–Soyuz) could not handle the 66,900-pound (30,300 kg) mass of the fully fueled CSM. This was not a problem, because the spacecraft delta-v requirement of these missions was much smaller than that of the lunar mission; therefore they could be launched with less than half of the full SPS propellant load, by filling only the SPS sump tanks and leaving the storage tanks empty. The CSMs launched in orbit on Saturn IB ranged from 32,558 pounds (14,768 kg) (Apollo–Soyuz), to 46,000 pounds (21,000 kg) (Skylab 4).

The omnidirectional antennas sufficed for ground communications during the Earth orbital missions, so the high-gain S-band antenna on the SM was omitted from Apollo 1, Apollo 7, and the three Skylab flights. It was restored for the Apollo–Soyuz mission to communicate through the ATS-6 satellite in geostationary orbit, an experimental precursor to the current TDRSS system.

On the Skylab and Apollo–Soyuz missions, some additional dry weight was saved by removing the otherwise empty fuel and oxidizer storage tanks (leaving the partially filled sump tanks), along with one of the two helium pressurant tanks.[29] This permitted the addition of some extra RCS propellant to allow for use as a backup for the deorbit burn in case of possible SPS failure.[30]

Since the spacecraft for the Skylab missions would not be occupied for most of the mission, there was lower demand on the power system, so one of the three fuel cells was deleted from these SMs. The command module was also partially painted white, to provide passive thermal control for the extended time it would remain in orbit.

The command module could be modified to carry extra astronauts as passengers by adding jump seat couches in the aft equipment bay. CM-119 was fitted with two jump seats as a Skylab Rescue vehicle, which was never used.[31]

Major differences between Block I and Block II

[edit]Command module

[edit]

- The Block II used a one-piece, quick-release, outward opening hatch instead of the two-piece plug hatch used on Block I, in which the inner piece had to be unbolted and placed inside the cabin in order to enter or exit the spacecraft (a flaw that doomed the Apollo 1 crew). The Block II hatch could be opened quickly in case of an emergency. (Both hatch versions were covered with an extra, removable section of the Boost Protective Cover which surrounded the CM to protect it in case of a launch abort.)

- The Block I forward access tunnel was smaller than Block II, and intended only for emergency crew egress after splashdown in case of problems with the main hatch. It was covered by the nose of the forward heat shield during flight. Block II contained a shorter forward heat shield with a flat removable hatch, beneath a docking ring and probe mechanism which captured and held the LM.

- The aluminized PET film layer, which gave the Block II heat shield a shiny mirrored appearance, was absent on Block I, exposing the light gray epoxy resin material, which on some flights was painted white.

- The Block I VHF scimitar antennas were located in two semicircular strakes originally thought necessary to help stabilize the CM during reentry. However, the uncrewed reentry tests proved these to be unnecessary for stability, and also aerodynamically ineffective at high simulated lunar reentry speeds. Therefore, the strakes were removed from Block II and the antennas were moved to the service module.

- The Block I CM/SM umbilical connector was smaller than on Block II, located near the crew hatch instead of nearly 180 degrees away from it. The separation point was between the modules, instead of the larger hinged arm mounted on the service module, separating at the CM sidewall on Block II.

- The two negative pitch RCS engines located in the forward compartment were arranged vertically on Block I, and horizontally on Block II.

Service module

[edit]

- On the Apollo 6 uncrewed Block I flight, the SM was painted white to match the command module's appearance. On Apollo 1, Apollo 4, and all the Block II spacecraft, the SM walls were left unpainted except for the EPS and ECS radiators, which were white.

- The EPS and ECS radiators were redesigned for Block II. Block I had three larger EPS radiators located on Sectors 1 and 4. The ECS radiators were located on the aft section of Sectors 2 and 5.

- The Block I fuel cells were located at the aft bulkhead in Sector 4, and their hydrogen and oxygen tanks were located in Sector 1.

- Block I had slightly longer SPS fuel and oxidizer tanks which carried more propellant than Block II.

- The Block II aft heat shield was a rectangular shape with slightly rounded corners at the propellant tank sectors. The Block I shield was the same basic shape, but bulged out slightly near the ends more like an hourglass or figure eight, to cover more of the tanks.

CSMs produced

[edit]| Serial number | Name | Use | Launch date | Current location | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block I[32][33][34] | |||||

| CSM-001 | systems compatibility test vehicle | scrapped[35] | |||

| CSM-002 | A-004 flight | January 20, 1966 | Command module on display at Cradle of Aviation, Long Island, New York[36] |

| |

| CSM-004 | static and thermal structural ground tests | scrapped[34] | |||

| CSM-006 | used for demonstrating tumbling debris removal system | Command module scrapped;[37] service module (redesignated as SM-010)[33] on display at U.S. Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama[38] |

| ||

| CSM-007 | various tests including acoustic vibration and drop tests, and water egress training. CM was refitted with Block II improvements.[39] Underwent testing for Skylab at the McKinley Climatic Laboratory, Eglin AFB, Florida, 1971–1973. | Command module on display at Museum of Flight, Seattle, Washington[40] |

| ||

| CSM-008 | complete systems spacecraft used in thermal vacuum tests | scrapped[35] |

| ||

| CSM-009 | AS-201 flight and drop tests | February 26, 1966 | Command module on display at Strategic Air and Space Museum, adjacent to Offutt Air Force Base in Ashland, Nebraska[41] |

| |

| CSM-010 | Thermal test (command module redesignated as CM-004A / BP-27 for dynamic tests);[42] service module never completed[33] | Command module on display at U.S. Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama[35] |

| ||

| CSM-011 | AS-202 flight | August 25, 1966 | Command module on display on the USS Hornet museum at the former Naval Air Station Alameda, Alameda, California[43] |

| |

| CSM-012 | Apollo 1; the command module was severely damaged in the Apollo 1 fire | Command module in storage at the Langley Research Center, Hampton, Virginia;[44] three-part door hatch on display at Kennedy Space Center;[45] service module scrapped[35] |

| ||

| CSM-014 | Command module disassembled as part of Apollo 1 investigation. Service module (SM-014) used on Apollo 6 mission. Command module (CM-014) later modified and used for ground testing (as CM-014A).[33] | Scrapped May 1977.[32] | |||

| CSM-017 | CM-017 flew on Apollo 4 with SM-020 after SM-017 was destroyed in a propellant tank explosion during ground testing.[33][46] | November 9, 1967 | Command module on display at Stennis Space Center, Bay St. Louis, Mississippi[47] |

| |

| CSM-020 | CM-020 flew on Apollo 6 with SM-014.[33] | April 4, 1968 | Command module on display at Fernbank Science Center, Atlanta |

| |

| Block II[48][49] | |||||

| CSM-098 | 2TV-1 (Block II Thermal Vacuum no.1)[50] | used in thermal vacuum tests | CSM on display at Academy of Science Museum, Moscow, Russia as part of the Apollo Soyuz Test Project display.[34] | ||

| CM-099 | 2S-1[50] | Skylab flight crew interface training;[50] impact tests[33] | scrapped[50] | ||

| CSM-100 | 2S-2[50] | static structural testing[33] | Command module "transferred to Smithsonian as an artifact", service module on display at New Mexico Museum of Space History[50] | ||

| CSM-101 | Apollo 7 | October 11, 1968 | Command module was on display at National Museum of Science and Technology, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada from 1974 until 2004, now at the Frontiers of Flight Museum, Dallas, Texas after 30 years of being on loan.[51] |

| |

| CSM-102 | Launch Complex 34 checkout vehicle | Command module scrapped;[52] service module is at JSC on top of the Little Joe II in Rocket Park with Boiler Plate 22 command module.[53] |

| ||

| CSM-103 | Apollo 8 | December 21, 1968 | Command module on display at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago[49] |

| |

| CSM-104 | Gumdrop | Apollo 9 | March 3, 1969 | Command module on display at San Diego Air and Space Museum[49] |

|

| CSM-105 | acoustic tests | On display at National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C. as part of the Apollo Soyuz Test Project display.[54] (Photo) | |||

| CSM-106 | Charlie Brown | Apollo 10 | May 18, 1969 | Command module on display at Science Museum, London[49] |

|

| CSM-107 | Columbia | Apollo 11 | July 16, 1969 | Command module on display at National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.[49] |

|

| CSM-108 | Yankee Clipper | Apollo 12 | November 14, 1969 | Command module on display at Virginia Air & Space Center, Hampton, Virginia;[49] previously on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Pensacola, Florida (exchanged for CSM-116) |

|

| CSM-109 | Odyssey | Apollo 13 | April 11, 1970 | Command module on display at Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center[49] |

|

| CSM-110 | Kitty Hawk | Apollo 14 | January 31, 1971 | Command module on display at the Kennedy Space Center[49] |

|

| CSM-111 | Apollo Soyuz Test Project | July 15, 1975 | Command module currently on display at California Science Center in Los Angeles, California[55][56][57] (formerly displayed at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex) |

| |

| CSM-112 | Endeavour | Apollo 15 | July 26, 1971 | Command module on display at National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio[49] |

|

| CSM-113 | Casper | Apollo 16 | April 16, 1972 | Command module on display at U.S. Space & Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama[49] |

|

| CSM-114 | America | Apollo 17 | December 7, 1972 | Command module on display at Space Center Houston, Houston, Texas[49] |

|

| CSM-115 | Apollo 19[58] (canceled) | Never fully completed[59] – service module does not have its SPS nozzle installed. On display as part of the Saturn V display at Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas[60] |

| ||

| CSM-115a | Apollo 20[61] (canceled) | Never fully completed[59] – internal structures not installed,[62] used for spare parts. Remaining items sent to Japan for exhibition in 1978 and never returned, display at the Space LABO in Kitakyushu,Japan.[63][64] |

| ||

| CSM-116 | Skylab 2 | May 25, 1973 | Command module on display at National Museum of Naval Aviation, Naval Air Station Pensacola, Pensacola, Florida[65] |

| |

| CSM-117 | Skylab 3 | July 28, 1973 | Command module on display at Great Lakes Science Center, current location of the NASA Glenn Research Center Visitor Center, Cleveland, Ohio[66] |

| |

| CSM-118 | Skylab 4 | November 16, 1973 | Command module on display at Oklahoma History Center[67] (formerly displayed at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.)[68] |

| |

| CSM-119 | Skylab Rescue and ASTP backup | On display at the Kennedy Space Center[69] |

| ||

See also

[edit]

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

Citations

- ^ "Aerojet AJ10-137 Archives". December 25, 2022.

- ^ Portree, David S. F. (September 2, 2013). "Project Olympus (1962)". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Compton, W. D.; Benson, C. D. (January 1983). "ch1". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Courtney G Brooks; James M. Grimwood; Loyd S. Swenson (1979). "Contracting for the Command Module". Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. NASA. ISBN 0-486-46756-2. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ Courtney G Brooks; James M. Grimwood; Loyd S. Swenson (1979). "Command Modules and Program Changes". Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. NASA. ISBN 0-486-46756-2. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ Morse, Mary Louise; Bays, Jean Kernahan (September 20, 2007). The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology. SP-4009II. Vol. II, Part 2(C): Developing Hardware Distinctions. NASA. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- ^ Orloff, Richard (1996). Apollo by the Numbers (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 22.

- ^ "NASA New Start Inflation Indices". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Press Kit". No. 69–83K. NASA. July 6, 1969.

- ^ Margolis, Jacob (July 16, 2019). "The Making Of Apollo's Command Module: 2 Engineers Recall Tragedy And Triumph". NPR.org. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ Chiotakis, Steve; Mesirow, Tod (July 15, 2019). "How Downey, California helped put Apollo 11 on the moon (and get the astronauts back safely)". KCRW. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "CSM06 Command Module Overview pp. 39–52" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Hillje, Ernest R., "Entry Aerodynamics at Lunar Return Conditions Obtained from the Flight of Apollo 4 (AS-501)," NASA TN D-5399, (1969).

- ^ Bloom, Kenneth (January 1, 1971). The Apollo docking system (Technical report). North American Rockwell Corporation. 19720005743.

- ^ West, Robert B., Apollo Experience Report: Earth Landing System, NASA Technical Note D-7437, p. 4, November 1973.

- ^ "Apollo CM". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Orloff, Richard (2000). Apollo by the numbers : a statistical reference (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 277. ISBN 0-16-050631-X. OCLC 44775012.

- ^ Day, Dwayne (May 26, 2009). "Making lemons into lemonade". The Space Review. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Day, Dwayne Allen (June 11, 2012). "Out of the black". The Space Review. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ Wilford, John (1969). We Reach the Moon: The New York Times Story of Man's Greatest Adventure. New York: Bantam Paperbacks. p. 167. ISBN 978-0552082051.

- ^ "Apollo CSM". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007.

- ^ Feldman, A. L.; David, Dan (1970). "Design of the Apollo Service Module Rocket Engine for Manned Operation". Space Engineering. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 15. Springer Netherlands. pp. 411–425. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-7551-7_30. ISBN 978-94-011-7553-1. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Apollo CSM SPS". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010.

- ^ "Apollo Operations Handbook, SM2A-03-Block II-(1)" (PDF). NASA. Section 2.4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

- ^ Apollo 11 Mission Report – Performance of the Command and Service Module Reaction Control System (PDF). NASA – Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. December 1971. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c SM2A-03-BLOCK II-(1), Apollo Operations Handbook (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1969. p. 8. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ "Apollo Operations Handbook, SM2A-03-Block II-(1)" (PDF). NASA. Section 2.7. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

- ^ "Nasa CSM/LM communication" (PDF). Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Reduced Apollo Block II service propulsion system for Saturn IB Missions". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft, Second Revision. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. p. 292. ISBN 0-02-542820-9.

- ^ " Mission Requirements, Skylab Rescue Mission, SL-R" NASA, 24 August 1973.

- ^ a b APOLLO/SKYLAB ASTP AND SHUTTLE --ORBITER MAJOR END ITEMS (PDF). NASA Johnson Space Center. 1978., p. 4

- ^ a b c d e f g h "CSM Contract" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ a b c "A Field Guide to American Spacecraft". Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 14.

- ^ "Rockwell Command Module 002 at the Cradle of Aviation Museum". Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 13.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, pp. 13, 17.

- ^ These included the crew couches, quick escape hatch, and metallic heat shield coating. See Apollo command module (image @ Wikimedia Commons).

- ^ Gerard, James H. (November 22, 2004). "CM-007". A Field Guide to American Spacecraft. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Apollo Command Space Module (CSM 009)". Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 14, 17.

- ^ "Permanent Exhibits". USS Hornet museum. December 8, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

the Apollo Command Module – CM-011. It was used for the uncrewed mission AS-202 on August 26, 1966

- ^ Tennant, Diane (February 17, 2007). "Burned Apollo I capsule moved to new storage facility in Hampton". PilotOnline.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ "50 years later, NASA displays fatal Apollo capsule". The Horn News. January 25, 2017. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ Wade, Mark (December 10, 1999). "CSM Block I". Encyclopedia Astronautica.

- ^ "Apollo 4 capsule from first Saturn V launch lands at Infinity Science Center". Collectspace.com. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ "Apollo Command and Service Module Documentation". NASA.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Location of Apollo Command Modules". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 4.

- ^ "Apollo 7 Command Module and Wally Schirra's Training Suit Leave Science and Tech Museum After 30 Years". Canada Science and Technology Museum. March 12, 2004. Archived from the original on August 17, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2009.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 5.

- ^ Gerard, James H. (July 11, 2007). "BP-22". A Field Guide to American Spacecraft. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, pp. 4, 5.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert (February 23, 2018). "Historic Apollo–Soyuz Spacecraft Gets New Display at CA Science Center". Space.com. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Apollo–Soyuz Command Module". californiasciencecenter.org. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert. "Apollo–Soyuz spacecraft gets new display at CA Science Center". collectSPACE. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Science and Astronautics (1970). 1971 NASA Authorization: Hearings, Ninety-first Congress, Second Session, on H.R. 15695 (superseded by H.R. 16516). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 884.

- ^ a b United States. Congress. House. Committee on Science and Astronautics (1973). 1974 NASA Authorization: Hearings, Ninety-third Congress, First Session, on H.R. 4567 (superseded by H.R. 7528). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 1272.

- ^ Hutchinson, Lee (September 19, 2015). "Exploring NASA's Johnson Space Center with the cast of The Martian". Ars Technica.

A close-up of the upper heat shield on CSM-115, the unfinished Apollo Block 2 command module that sits atop the Saturn.

- ^ Shayler, David (2002). Apollo: The Lost and Forgotten Missions. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 271. ISBN 1-85233-575-0.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Science and Astronautics (1973). Space Shuttle-Skylab 1973: Status Report for the Committee on Science and Astronautics. p. 397.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Science and Astronautics (October 1977). 1979 NASA Reauthorization (Program Review). p. 227.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 6

- ^ "Item – National Naval Aviation Museum". National Naval Aviation Museum. September 5, 2015. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Navratil, Liz (June 23, 2010). "Skylab space capsule lands at Cleveland's Great Lakes Science Center". Cleveland.com. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ McDonnell, Brandy (November 17, 2020). "Oklahoma History Center celebrating 15th anniversary with free admission, new exhibit 'Launch to Landing: Oklahomans and Space'". The Oklahoman. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ "Skylab 4 capsule to land in new exhibit at Oklahoma History Center". Collect Space. August 28, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ Johnson Space Center 1978, p. 7.

Apollo command and service module

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Pre-Apollo Spacecraft Development

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established on July 29, 1958, through the National Aeronautics and Space Act, consolidating U.S. aeronautical research efforts in response to the Soviet Union's Sputnik launch. Shortly thereafter, on October 7, 1958, NASA officially initiated Project Mercury as its first human spaceflight program, focusing on developing a single-seat spacecraft capable of safely launching an astronaut into Earth orbit and returning them via a ballistic reentry.[8] The Mercury capsule, designed by Maxime Faget's team at NASA's Langley Research Center, featured a compact, cone-shaped structure with a blunt base to generate high drag during reentry, addressing the critical challenge of atmospheric heating that could exceed 3,000°F (1,650°C).[9] This single-pilot design prioritized simplicity and reliability for short-duration missions—typically under 24 hours—but highlighted limitations in crew capacity, life support duration, and maneuverability, necessitating advancements for more ambitious goals like lunar travel.[10] Building on Mercury's successes, NASA launched Project Gemini in 1961 as a bridge to lunar missions, evolving the spacecraft to accommodate two astronauts for extended flights up to two weeks, thereby testing multi-crew operations and human factors in confined spaces.[11] Gemini addressed Mercury's shortcomings by incorporating rendezvous and docking capabilities with uncrewed targets, essential for assembling larger spacecraft in orbit—a technique critical for lunar missions but absent in Mercury's suborbital and short orbital profiles.[12] Reentry heating remained a persistent challenge, with both programs relying on ablative heat shields that charred and eroded to dissipate thermal loads, but Gemini's higher velocities and durations pushed material limits further, informing scalable protections for deeper space.[9] Parallel experimental efforts, such as the X-15 hypersonic research program (1959–1968), provided foundational data on high-speed aerothermodynamics and structural integrity under extreme heating, directly influencing ablative material development for spacecraft reentry systems.[13] The X-15, reaching speeds over Mach 6, tested turbulent heat-transfer phenomena and early ablator coatings, contributing to the design of heat shields capable of withstanding lunar-return velocities without catastrophic failure.[14] These insights from suborbital rocket planes complemented Mercury and Gemini by validating material behaviors in regimes beyond orbital reentry. As lunar ambitions grew, NASA evaluated mission architectures in the early 1960s, contrasting direct ascent—which required a massive single rocket to launch the entire spacecraft to the Moon and back—with Earth-orbit rendezvous (multiple launches to assemble a lunar vehicle in low Earth orbit) and lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR), where a command module orbited the Moon while a separate lander descended.[15] After rigorous analysis, NASA selected LOR on July 11, 1962, for its efficiency in reducing launch mass and enabling modular spacecraft design, setting the stage for Apollo's multi-component approach.[16]Apollo Program Initiation and Spacecraft Selection

The Apollo program was initiated amid heightened Cold War tensions in space exploration, spurred by the Soviet Union's early successes. On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space aboard Vostok 1, an event that underscored American lagging capabilities following the Sputnik launch in 1957 and intensified pressure on the U.S. to respond decisively.[17] Just over a month later, on May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy addressed a joint session of Congress, committing the United States to the goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" before the end of the decade, framing it as a national imperative to restore U.S. prestige in science and technology.[18] This announcement marked the formal launch of the Apollo program, building on the limitations of prior efforts like Project Mercury's single-crew, short-duration flights and Project Gemini's two-person configuration, which were insufficient for extended lunar missions. To support this ambitious objective, Kennedy requested funding for the space program including $531 million in fiscal year 1962 for new initiatives and an estimated additional $7 billion to $9 billion over the next five years, contributing to NASA's overall FY1962 appropriation of approximately $1.8 billion, with allocations ramping up to approximately $5.4 billion annually by the mid-1960s to cover development, launches, and operations.[19][20][21] In July 1961, NASA Administrator James E. Webb, in consultation with Kennedy, established an ad hoc committee under Nicholas E. Golovin to outline the program's structure, leading to the formal organization of the Office of Manned Space Flight and initial planning for a three-man spacecraft capable of supporting lunar travel.[22] By late 1961, preliminary specifications emerged for the Apollo spacecraft, envisioning a command module as the crew's habitat and reentry vehicle, paired with a service module providing propulsion, power, and life support systems essential for the mission's demands. The program's rapid advancement included competitive processes to select prime contractors. NASA issued requests for proposals in August 1961 to 14 major aerospace firms, including Boeing, General Dynamics' Astronautics Division, Lockheed, and Martin, evaluating designs for a versatile, three-crew vehicle with orbital and lunar capabilities. After rigorous review of technical proposals, mockups, and management plans, North American Aviation was awarded the contract for the command and service module (CSM) on November 28, 1961, chosen for its demonstrated expertise in aircraft and missile systems, though the decision drew some internal NASA debate over cost and innovation.[3] This selection solidified the CSM as the program's core spacecraft, setting the stage for subsequent development under the newly formed Apollo Spacecraft Program Office at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in January 1962.Design and Development

Early Design Concepts and Contractors

The initial design of the Apollo command and service module (CSM) featured a cone-shaped command module (CM) for aerodynamic stability during reentry and a cylindrical service module (SM) to house propulsion and support systems.[23] This configuration emerged from early studies emphasizing a compact, reentry-capable crew compartment atop a propulsion stage, selected after evaluations of various lunar mission modes in 1961-1962.[5] North American Aviation was awarded the prime contract for the CSM on November 28, 1961, responsible for overall design, integration, and production of both the CM and SM.[3] Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, as the lunar module (LM) contractor, collaborated on interface designs to ensure compatibility between the CSM and LM for orbital docking and extraction maneuvers.[24] Subsystem responsibilities included RCA for the communications system, providing radios and telemetry for ground and inter-vehicle links, and Hamilton Standard for the environmental control system (ECS), which managed cabin atmosphere, temperature, and humidity. Early concepts incorporated a unified stack integrating the S-IVB upper stage with the CSM for translunar injection, allowing the CSM to separate and maneuver independently after launch.[25] Docking mechanisms evolved from 1962 studies, with North American Aviation proposing extendable probe-and-drogue systems to capture and latch the LM during rendezvous.[26] The preliminary design review in late 1962 solidified these architectural decisions, confirming the CSM's role in the lunar orbit rendezvous mode.[5] Budget overruns in 1963, driven by escalating development costs that increased Apollo obligations by 130% from the prior year, prompted partial redesigns to optimize weight and subsystem integration without altering core structures.[27] Early radiation shielding concepts addressed Van Allen belt exposure through the CM's aluminum pressure vessel and ablative heat shield, providing sufficient attenuation for the brief transit—estimated at 1-2 rem dose—while prioritizing lightweight materials over heavy shielding.[28] These measures were refined in Block I prototypes but rooted in 1961-1962 analyses of trapped proton and electron fluxes.[28]Development Timeline and Testing

The development of the Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) commenced with NASA issuing a letter contract to North American Aviation on November 28, 1961, tasking the company with designing and building the spacecraft as the primary crewed component of the Apollo program. This marked the formal start of engineering efforts, building on preliminary concepts from earlier NASA studies. By mid-1962, progress advanced to the construction of initial prototypes; the first Block I mockup underwent inspection on July 10, 1962, at North American's Space and Information Systems Division in Downey, California, where NASA officials, including Manned Spacecraft Center Director Robert R. Gilruth, reviewed the basic configuration for crew accommodations, systems layout, and interfaces.[3][29] Prototyping and ground testing intensified in 1963–1965, focusing on subsystems and structural integrity, with early boilerplate models used for preliminary evaluations. A critical phase involved verifying the launch escape system through uncrewed abort tests using the Little Joe II rocket at White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico. The Pad Abort Test, designated A-004, launched on January 20, 1966, successfully demonstrated the command module's separation from a simulated launch pad under emergency conditions, reaching an altitude of 34.6 kilometers before parachute deployment and splashdown. Complementing this, the Little Joe II A-003 ascent abort test on December 8, 1965—often grouped with 1966 efforts due to its role in the final qualification sequence—simulated a high-dynamic-pressure abort during launch, confirming the escape tower's performance despite minor anomalies in booster separation. These tests validated the CSM's ability to protect the crew in launch emergencies.[30][31] The first integrated flight test of a production Block I CSM occurred on February 26, 1966, during the unmanned AS-201 suborbital mission atop a Saturn IB launch vehicle from Cape Kennedy's Launch Complex 34. Lasting 37 minutes, the flight reached a maximum altitude of 488 kilometers and downrange distance of 8,472 kilometers, evaluating structural loads, thermal protection during reentry, and service module propulsion; the command module splashed down intact in the Atlantic Ocean, with post-flight analysis confirming the spacecraft's robustness despite minor heat shield ablation.[32] A tragic setback occurred on January 27, 1967, when a flash fire during a plugs-out ground simulation test of the Block I CSM for Apollo 1 at Launch Complex 34 killed astronauts Virgil I. Grissom, Edward H. White II, and Roger B. Chaffee. The incident, fueled by a pure-oxygen atmosphere and combustible materials, exposed design flaws in the inward-opening hatch and wiring insulation. NASA's subsequent investigation prompted extensive redesigns for the Block II CSM, including a unified outward-opening hatch for faster egress, non-flammable materials throughout the cabin, improved wiring harnesses, and a shift to a nitrogen-oxygen atmosphere during ground operations—delaying manned flights by over 21 months but enhancing overall safety.[33] Parallel ground testing phases addressed reentry, landing, and space environment challenges. Drop tests for the Earth landing system began in 1963 using boilerplate command modules dropped from C-133 Cargomaster aircraft over El Centro, California, to qualify the three-parachute deployment sequence and assess water impact loads; the final full-scale test on July 3, 1968, confirmed stability and deceleration within design limits. Thermal-vacuum testing simulated deep-space conditions in large chambers, such as those at the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory (SESL) at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center), where full-scale CSMs underwent extended exposures to vacuum and temperature extremes from -156°C to +121°C, verifying systems performance for missions like Apollo 7 in 1968.[34][35][36] Qualification efforts culminated in a comprehensive certification program, encompassing over 700 dynamic, thermal, and climatic tests on flight hardware to simulate mission profiles. These accumulated thousands of hours in environmental facilities, including vibration tables, acoustic chambers, and altitude simulations at contractor sites like North American's Downey plant, ensuring the CSM met reliability thresholds before integration. Integration testing with the Saturn IB (as in AS-201 and AS-204) and later Saturn V vehicles, starting with AS-501 in 1967, focused on stack-up procedures, umbilical connections, and launch pad operations at Kennedy Space Center, confirming end-to-end compatibility for lunar missions.[37][38]Block I and Block II Configurations

The Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) was developed in two distinct configurations, Block I and Block II, to progressively advance the spacecraft from initial testing to full lunar mission capability. Block I vehicles served primarily for unmanned earth-orbital development flights, such as AS-201, AS-202, and AS-203, which qualified key systems like launch, reentry, and basic propulsion without exposing crews to lunar transit risks. These tests were essential in validating the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) strategy by confirming the CSM's performance in near-Earth conditions, allowing NASA to refine designs iteratively before committing to high-stakes lunar operations.[39][33] Block I CSM lacked a docking probe and transfer tunnel, as they were not designed for lunar module compatibility, and featured a stainless steel honeycomb outer structure over a steel pressure vessel for the command module to ensure durability during early qualification trials. The environmental control system (ECS) was configured for shorter test durations, prioritizing basic life support over extended mission needs. Only a limited number of Block I flight vehicles were produced—three for unmanned tests plus one for the planned crewed AS-204 mission—to focus resources on rapid prototyping and risk reduction.[40][41] The Block II configuration, introduced for crewed lunar flights starting with Apollo 7 (AS-205), incorporated major enhancements driven by lessons from Block I tests and the Apollo 1 fire. It added a probe-and-drogue docking mechanism in the command module's forward compartment to enable secure coupling with the lunar module during transposition, docking, and extraction maneuvers. The command module shifted to an aluminum honeycomb sandwich structure for the inner pressure vessel and sidewalls, reducing overall mass while preserving structural integrity for trans-lunar injection and reentry loads. Post-fire redesigns emphasized fire safety, including low-flammability materials like beta cloth for interiors and beta marquisette for thermal garments, alongside elimination of ignition sources such as exposed wiring and pure oxygen pre-launch environments. A unified hatch replaced the multi-piece Block I design, allowing rapid inward or outward opening in under 5 seconds for emergency egress, with the crew cabin providing 210 cubic feet of habitable volume. Approximately 16 Block II CSMs were built, with 11 supporting the crewed Apollo missions from Apollo 7 to 17.[42][43][44][45] The evolution from Block I to Block II represented a critical pivot toward operational reliability, with Block I's earth-bound validations minimizing uncertainties in the LOR approach and Block II's refinements enabling the success of NASA's lunar objectives.[41]| Aspect | Block I | Block II |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Unmanned earth-orbital qualification (e.g., AS-201 to AS-203) | Crewed Apollo missions (e.g., Apollo 7 onward) |

| Docking Capability | None; no probe or transfer tunnel | Probe-and-drogue system for LM interface |

| CM Structure | Stainless steel honeycomb outer shell; steel pressure vessel | Aluminum honeycomb inner/outer skins; aluminum pressure vessel |

| Fire Safety Features | Standard materials; multi-piece hatch | Low-flammability fabrics; unified quick-open hatch |

| Production Quantity | Limited (4 flight vehicles total) | ~16 total, 11 for crewed Apollo missions |

Command Module (CM)

Construction and Structure

The Apollo Command Module (CM) was designed as a blunt cone-shaped spacecraft, measuring 12.8 feet (3.91 meters) in base diameter and 11.4 feet (3.48 meters) in height, providing a compact, reentry-stable form factor for three astronauts.[46] This configuration optimized aerodynamic performance during atmospheric entry while maintaining structural integrity under launch, spaceflight, and reentry conditions. The overall structure relied on lightweight, high-strength materials to balance mass constraints with durability, essential for the mission's demands. The CM's primary structure centered on an aluminum pressure vessel serving as the habitable core, constructed from a welded aluminum alloy inner skin, an adhesively bonded aluminum honeycomb core, and an outer aluminum face sheet to form sandwich panels.[44] These panels, varying in thickness from approximately 1 to 2 inches, provided rigidity and leak-proof containment for the internal pressure of 5 psi. The vessel was divided into three main compartments: a small forward compartment at the apex for recovery equipment, the central crew compartment housing the astronauts and primary systems, and an aft equipment bay for propulsion and guidance components. For the Block II configuration used in lunar missions, the CM's empty weight was approximately 12,250 pounds (5,557 kilograms), reflecting optimizations for reduced mass without compromising strength.[24] Manufacturing occurred at North American Aviation's facility in Downey, California, where the structure was assembled through a combination of riveting for panel joints and adhesive bonding for the honeycomb layers, ensuring precise alignment and load distribution.[47] This process allowed the CM to withstand structural loads up to 8 g during reentry, including deceleration forces and thermal stresses, while the outer layers incorporated stainless steel honeycomb panels for added micrometeoroid protection against high-velocity impacts in space.[48] The design integrated seamlessly with the thermal protection system, where the aluminum structure supported the overlying ablative materials without direct exposure to reentry heating.[49]Thermal Protection and Reentry Systems

The thermal protection system of the Apollo command module (CM) primarily consisted of an ablative heat shield made from Avcoat 5026-39, an epoxy-novolac resin reinforced with 25% fibrous silica by weight, designed to protect the spacecraft during high-speed atmospheric reentry from lunar missions.[50] This material was applied in varying thicknesses across the CM's heat shield, reaching up to 2 inches at the apex and approximately 0.85 inches on the conical base, where it was molded into a fiberglass honeycomb structure bonded to the spacecraft's outer mold line.[51] During reentry, Avcoat ablated in a controlled manner, charring and vaporizing to carry away heat, with the material capable of withstanding peak surface temperatures of around 5,000°F while limiting internal temperatures to safe levels for the crew and structure.[50] The reentry profile for lunar returns involved entry velocities of approximately 36,000 ft/s, corresponding to Mach numbers around 36 at the interface altitude of 400,000 feet, with peak heating and deceleration occurring at about Mach 25.[52] Peak decelerations ranged from 4 to 7 g, depending on the trajectory, ensuring the total integrated heat load on the heat shield was approximately 10,000 BTU/ft² for the forward-facing areas.[51] This system was complemented by a backup earth landing capability, providing redundancy for the CM's safe return.[53] Development of the Avcoat heat shield began in the early 1960s, with initial flight testing conducted using the hemispherically blunted nose cap of a Pacemaker vehicle during the Pac Fair reentry experiment in 1963, which validated ablation rates and temperature profiles under simulated high-speed conditions.[54] Subsequent ground and flight tests, including those on Apollo missions like AS-202, confirmed the material's performance against predicted heating environments.[55] In the 2020s, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analyses have revisited Apollo reentry data, generating laminar flow databases for the heat shield that affirm Avcoat's thermal efficiency, demonstrating it remains competitive with modern ablative alternatives for similar entry profiles due to its proven recession and insulation properties.[56] The shield was structurally mounted to the CM's pressure vessel via an epoxy adhesive, integrating seamlessly with the overall conical configuration.[51]Compartment Layout and Interfaces