Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Enzyme

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Biochemistry |

|---|

|

An enzyme is a biological macromolecule, usually a protein, that acts as a biological catalyst, accelerating chemical reactions without being consumed in the process. The molecules on which enzymes act are called substrates, which are converted into products. Nearly all metabolic processes within a cell depend on enzyme catalysis to occur at biologically relevant rates.[1]: 8.1 Metabolic pathways are typically composed of a series of enzyme-catalyzed steps. The study of enzymes is known as enzymology, and a related field focuses on pseudoenzymes—proteins that have lost catalytic activity but may retain regulatory or scaffolding functions, often indicated by alterations in their amino acid sequences or unusual 'pseudocatalytic' behavior.[2][3]

Enzymes are known to catalyze over 5,000 types of biochemical reactions.[4] Other biological catalysts include catalytic RNA molecules, or ribozymes, which are sometimes classified as enzymes despite being composed of RNA rather than protein. More recently, biomolecular condensates have been recognized as a third category of biocatalysts, capable of catalyzing reactions by creating interfaces and gradients—such as ionic gradients—that drive biochemical processes, even when their component proteins are not intrinsically catalytic.[5]

Enzymes increase the reaction rate by lowering a reaction's activation energy, often by factors of millions. A striking example is orotidine 5'-phosphate decarboxylase, which accelerates a reaction that would otherwise take millions of years to occur in milliseconds.[6][7] Like all catalysts, enzymes do not affect the overall equilibrium of a reaction and are regenerated at the end of each cycle. What distinguishes them is their high specificity, determined by their unique three-dimensional structure, and their sensitivity to factors such as temperature and pH. Enzyme activity can be enhanced by activators or diminished by inhibitors, many of which serve as drugs or poisons. Outside optimal conditions, enzymes may lose their structure through denaturation, leading to loss of function.

Enzymes have widespread practical applications. In industry, they are used to catalyze the production of antibiotics and other complex molecules. In everyday life, enzymes in biological washing powders break down protein, starch, and fat stains, enhancing cleaning performance. Papain and other proteolytic enzymes are used in meat tenderizers to hydrolyze proteins, improving texture and digestibility. Their specificity and efficiency make enzymes indispensable in both biological systems and commercial processes.

Etymology and history

[edit]By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the digestion of meat by stomach secretions[8] and the conversion of starch to sugars by plant extracts and saliva were known but the mechanisms by which these occurred had not been identified.[9]

French chemist Anselme Payen was the first to discover an enzyme, diastase, in 1833.[10] A few decades later, when studying the fermentation of sugar to alcohol by yeast, Louis Pasteur concluded that this fermentation was caused by a vital force contained within the yeast cells called "ferments", which were thought to function only within living organisms. He wrote that "alcoholic fermentation is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells, not with the death or putrefaction of the cells."[11]

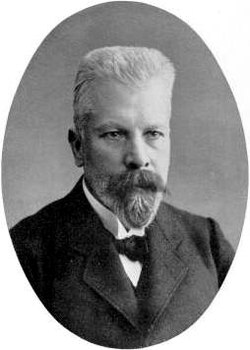

In 1877, German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne (1837–1900) first used the term enzyme, which comes from Ancient Greek ἔνζυμον (énzymon) 'leavened, in yeast', to describe this process.[12] The word enzyme was used later to refer to nonliving substances such as pepsin, and the word ferment was used to refer to chemical activity produced by living organisms.[13]

Eduard Buchner submitted his first paper on the study of yeast extracts in 1897. In a series of experiments at the University of Berlin, he found that sugar was fermented by yeast extracts even when there were no living yeast cells in the mixture.[14] He named the enzyme that brought about the fermentation of sucrose "zymase".[15] In 1907, he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "his discovery of cell-free fermentation". Following Buchner's example, enzymes are usually named according to the reaction they carry out: the suffix -ase is combined with the name of the substrate (e.g., lactase is the enzyme that cleaves lactose) or to the type of reaction (e.g., DNA polymerase forms DNA polymers).[16]

The biochemical identity of enzymes was still unknown in the early 1900s. Many scientists observed that enzymatic activity was associated with proteins, but others (such as Nobel laureate Richard Willstätter) argued that proteins were merely carriers for the true enzymes and that proteins per se were incapable of catalysis.[17] In 1926, James B. Sumner showed that the enzyme urease was a pure protein and crystallized it; he did likewise for the enzyme catalase in 1937. The conclusion that pure proteins can be enzymes was definitively demonstrated by John Howard Northrop and Wendell Meredith Stanley, who worked on the digestive enzymes pepsin (1930), trypsin and chymotrypsin. These three scientists were awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[18]

The discovery that enzymes could be crystallized eventually allowed their structures to be solved by x-ray crystallography. This was first done for lysozyme, an enzyme found in tears, saliva and egg whites that digests the coating of some bacteria; the structure was solved by a group led by David Chilton Phillips and published in 1965.[19] This high-resolution structure of lysozyme marked the beginning of the field of structural biology and the effort to understand how enzymes work at an atomic level of detail.[20]

Classification and nomenclature

[edit]Enzymes can be classified by two main criteria: either amino acid sequence similarity (and thus evolutionary relationship) or enzymatic activity.

Enzyme activity. An enzyme's name is often derived from its substrate or the chemical reaction it catalyzes, with the word ending in -ase.[1]: 8.1.3 Examples are lactase, alcohol dehydrogenase and DNA polymerase. Different enzymes that catalyze the same chemical reaction are called isozymes.[1]: 10.3

The International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology have developed a nomenclature for enzymes, the EC numbers (for "Enzyme Commission"). Each enzyme is described by "EC" followed by a sequence of four numbers which represent the hierarchy of enzymatic activity (from very general to very specific). That is, the first number broadly classifies the enzyme based on its mechanism while the other digits add more and more specificity.[21]

The top-level classification is:

- EC 1, Oxidoreductases: catalyze oxidation/reduction reactions

- EC 2, Transferases: transfer a functional group (e.g. a methyl or phosphate group)

- EC 3, Hydrolases: catalyze the hydrolysis of various bonds

- EC 4, Lyases: cleave various bonds by means other than hydrolysis and oxidation

- EC 5, Isomerases: catalyze isomerization changes within a single molecule

- EC 6, Ligases: join two molecules with covalent bonds.

- EC 7, Translocases: catalyze the movement of ions or molecules across membranes, or their separation within membranes.

These sections are subdivided by other features such as the substrate, products, and chemical mechanism. An enzyme is fully specified by four numerical designations. For example, hexokinase (EC 2.7.1.1) is a transferase (EC 2) that adds a phosphate group (EC 2.7) to a hexose sugar, a molecule containing an alcohol group (EC 2.7.1).[22]

Sequence similarity. EC categories do not reflect sequence similarity. For instance, two ligases of the same EC number that catalyze exactly the same reaction can have completely different sequences. Independent of their function, enzymes, like any other proteins, have been classified by their sequence similarity into numerous families. These families have been documented in dozens of different protein and protein family databases such as Pfam.[23]

Non-homologous isofunctional enzymes. Unrelated enzymes that have the same enzymatic activity have been called non-homologous isofunctional enzymes.[24] Horizontal gene transfer may spread these genes to unrelated species, especially bacteria where they can replace endogenous genes of the same function, leading to hon-homologous gene displacement.

Structure

[edit]

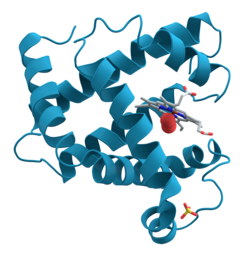

Enzymes are generally globular proteins, acting alone or in larger complexes. The sequence of the amino acids specifies the structure which in turn determines the catalytic activity of the enzyme.[25] Although structure determines function, a novel enzymatic activity cannot yet be predicted from structure alone.[26] Enzyme structures unfold (denature) when heated or exposed to chemical denaturants and this disruption to the structure typically causes a loss of activity.[27] Enzyme denaturation is normally linked to temperatures above a species' normal level; as a result, enzymes from bacteria living in volcanic environments such as hot springs are prized by industrial users for their ability to function at high temperatures, allowing enzyme-catalysed reactions to be operated at a very high rate.

Enzymes are usually much larger than their substrates. Sizes range from just 62 amino acid residues, for the monomer of 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase,[28] to over 2,500 residues in the animal fatty acid synthase.[29] Only a small portion of their structure (around 2–4 amino acids) is directly involved in catalysis: the catalytic site.[30] This catalytic site is located next to one or more binding sites where residues orient the substrates. The catalytic site and binding site together compose the enzyme's active site. The remaining majority of the enzyme structure serves to maintain the precise orientation and dynamics of the active site.[31]

In some enzymes, no amino acids are directly involved in catalysis; instead, the enzyme contains sites to bind and orient catalytic cofactors.[31] Enzyme structures may also contain allosteric sites where the binding of a small molecule causes a conformational change that increases or decreases activity.[32]

A small number of RNA-based biological catalysts called ribozymes exist, which again can act alone or in complex with proteins. The most common of these is the ribosome which is a complex of protein and catalytic RNA components.[1]: 2.2

Mechanism

[edit]

Substrate binding

[edit]Enzymes must bind their substrates before they can catalyse any chemical reaction. Enzymes are usually very specific as to what substrates they bind and then the chemical reaction catalysed. Specificity is achieved by binding pockets with complementary shape, charge and hydrophilic/hydrophobic characteristics to the substrates. Enzymes can therefore distinguish between very similar substrate molecules to be chemoselective, regioselective and stereospecific.[33]

Some of the enzymes showing the highest specificity and accuracy are involved in the copying and expression of the genome. Some of these enzymes have "proof-reading" mechanisms. Here, an enzyme such as DNA polymerase catalyzes a reaction in a first step and then checks that the product is correct in a second step.[34] This two-step process results in average error rates of less than 1 error in 100 million reactions in high-fidelity mammalian polymerases.[1]: 5.3.1 Similar proofreading mechanisms are also found in RNA polymerase,[35] aminoacyl tRNA synthetases[36] and ribosomes.[37]

Conversely, some enzymes display enzyme promiscuity, having broad specificity and acting on a range of different physiologically relevant substrates. Many enzymes possess small side activities which arose fortuitously (i.e. neutrally), which may be the starting point for the evolutionary selection of a new function.[38][39]

"Lock and key" model

[edit]To explain the observed specificity of enzymes, in 1894 Emil Fischer proposed that both the enzyme and the substrate possess specific complementary geometric shapes that fit exactly into one another.[40] This is often referred to as "the lock and key" model.[1]: 8.3.2 This early model explains enzyme specificity, but fails to explain the stabilization of the transition state that enzymes achieve.[41]

Induced fit model

[edit]In 1958, Daniel Koshland suggested a modification to the lock and key model: since enzymes are rather flexible structures, the active site is continuously reshaped by interactions with the substrate as the substrate interacts with the enzyme.[42] As a result, the substrate does not simply bind to a rigid active site; the amino acid side-chains that make up the active site are molded into the precise positions that enable the enzyme to perform its catalytic function. In some cases, such as glycosidases, the substrate molecule also changes shape slightly as it enters the active site.[43] The active site continues to change until the substrate is completely bound, at which point the final shape and charge distribution is determined.[44] Induced fit may enhance the fidelity of molecular recognition in the presence of competition and noise via the conformational proofreading mechanism.[45]

Catalysis

[edit]Enzymes can accelerate reactions in several ways, all of which lower the activation energy (ΔG‡, Gibbs free energy)[46]

- By stabilizing the transition state:

- Creating an environment with a charge distribution complementary to that of the transition state to lower its energy[47]

- By providing an alternative reaction pathway:

- Temporarily reacting with the substrate, forming a covalent intermediate to provide a lower energy transition state[48]

- By destabilizing the substrate ground state:

- Distorting bound substrate(s) into their transition state form to reduce the energy required to reach the transition state[49]

- By orienting the substrates into a productive arrangement to reduce the reaction entropy change[50] (the contribution of this mechanism to catalysis is relatively small)[51]

Enzymes may use several of these mechanisms simultaneously. For example, proteases such as trypsin perform covalent catalysis using a catalytic triad, stabilize charge build-up on the transition states using an oxyanion hole, complete hydrolysis using an oriented water substrate.[52]

Dynamics

[edit]Enzymes are not rigid, static structures; instead they have complex internal dynamic motions – that is, movements of parts of the enzyme's structure such as individual amino acid residues, groups of residues forming a protein loop or unit of secondary structure, or even an entire protein domain. These motions give rise to a conformational ensemble of slightly different structures that interconvert with one another at equilibrium. Different states within this ensemble may be associated with different aspects of an enzyme's function. For example, different conformations of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase are associated with the substrate binding, catalysis, cofactor release, and product release steps of the catalytic cycle,[53] consistent with catalytic resonance theory. The transitions between the different conformations during the catalytic cycle involve internal viscoelastic motion that is facilitated by high-strain regions where amino acids are rearranged.[54]

Substrate presentation

[edit]Substrate presentation is a process where the enzyme is sequestered away from its substrate. Enzymes can be sequestered to the plasma membrane away from a substrate in the nucleus or cytosol.[55] Or within the membrane, an enzyme can be sequestered into lipid rafts away from its substrate in the disordered region. When the enzyme is released it mixes with its substrate. Alternatively, the enzyme can be sequestered near its substrate to activate the enzyme. For example, the enzyme can be soluble and upon activation bind to a lipid in the plasma membrane and then act upon molecules in the plasma membrane.[56]

Allosteric modulation

[edit]Allosteric sites are pockets on the enzyme, distinct from the active site, that bind to molecules in the cellular environment. These molecules then cause a change in the conformation or dynamics of the enzyme that is transduced to the active site and thus affects the reaction rate of the enzyme.[57] In this way, allosteric interactions can either inhibit or activate enzymes. Allosteric interactions with metabolites upstream or downstream in an enzyme's metabolic pathway cause feedback regulation, altering the activity of the enzyme according to the flux through the rest of the pathway.[58]

Cofactors

[edit]

Some enzymes do not need additional components to show full activity. Others require non-protein molecules called cofactors to be bound for activity.[59] Cofactors can be either inorganic (e.g., metal ions and iron–sulfur clusters) or organic compounds (e.g., flavin and heme). These cofactors serve many purposes; for instance, metal ions can help in stabilizing nucleophilic species within the active site.[60] Organic cofactors can be either coenzymes, which are released from the enzyme's active site during the reaction, or prosthetic groups, which are tightly bound to an enzyme. Organic prosthetic groups can be covalently bound (e.g., biotin in enzymes such as pyruvate carboxylase).[61]

An example of an enzyme that contains a cofactor is carbonic anhydrase, which uses a zinc cofactor bound as part of its active site.[62] These tightly bound ions or molecules are usually found in the active site and are involved in catalysis.[1]: 8.1.1 For example, flavin and heme cofactors are often involved in redox reactions.[1]: 17

Enzymes that require a cofactor but do not have one bound are called apoenzymes or apoproteins. An enzyme together with the cofactor(s) required for activity is called a holoenzyme (or haloenzyme). The term holoenzyme can also be applied to enzymes that contain multiple protein subunits, such as the DNA polymerases; here the holoenzyme is the complete complex containing all the subunits needed for activity.[1]: 8.1.1

Coenzymes

[edit]Coenzymes are small organic molecules that can be loosely or tightly bound to an enzyme. Coenzymes transport chemical groups from one enzyme to another.[63] Examples include NADH, NADPH and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Some coenzymes, such as flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), and tetrahydrofolate (THF), are derived from vitamins. These coenzymes cannot be synthesized by the body de novo and closely related compounds (vitamins) must be acquired from the diet. The chemical groups carried include:

- the hydride ion (H−), carried by NAD or NADP+

- the phosphate group, carried by adenosine triphosphate

- the acetyl group, carried by coenzyme A

- formyl, methenyl or methyl groups, carried by folic acid and

- the methyl group, carried by S-adenosylmethionine[63]

Since coenzymes are chemically changed as a consequence of enzyme action, it is useful to consider coenzymes to be a special class of substrates, or second substrates, which are common to many different enzymes. For example, about 1000 enzymes are known to use the coenzyme NADH.[64]

Coenzymes are usually continuously regenerated and their concentrations maintained at a steady level inside the cell. For example, NADPH is regenerated through the pentose phosphate pathway and S-adenosylmethionine by methionine adenosyltransferase. This continuous regeneration means that small amounts of coenzymes can be used very intensively. For example, the human body turns over its own weight in ATP each day.[65]

Thermodynamics

[edit]

As with all catalysts, enzymes do not alter the position of the chemical equilibrium of the reaction. In the presence of an enzyme, the reaction runs in the same direction as it would without the enzyme, just more quickly.[1]: 8.2.3 For example, carbonic anhydrase catalyzes its reaction in either direction depending on the concentration of its reactants:[66]

| (in tissues; high CO2 concentration) | 1 |

| (in lungs; low CO2 concentration) | 2 |

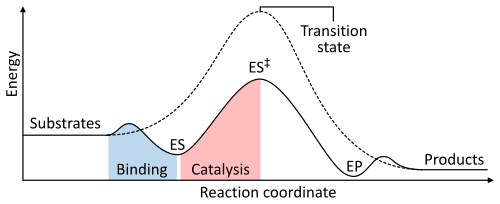

The rate of a reaction is dependent on the activation energy needed to form the transition state which then decays into products. Enzymes increase reaction rates by lowering the energy of the transition state. First, binding forms a low energy enzyme-substrate complex (ES). Second, the enzyme stabilises the transition state such that it requires less energy to achieve compared to the uncatalyzed reaction (ES‡). Finally the enzyme-product complex (EP) dissociates to release the products.[1]: 8.3

Enzymes can couple two or more reactions, so that a thermodynamically favorable reaction can be used to "drive" a thermodynamically unfavourable one so that the combined energy of the products is lower than the substrates. For example, the hydrolysis of ATP is often used to drive other chemical reactions.[67]

Kinetics

[edit]Enzyme kinetics is the investigation of how enzymes bind substrates and turn them into products.[68] The rate data used in kinetic analyses are commonly obtained from enzyme assays. In 1913 Leonor Michaelis and Maud Leonora Menten proposed a quantitative theory of enzyme kinetics, which is referred to as Michaelis–Menten kinetics.[69] The major contribution of Michaelis and Menten was to think of enzyme reactions in two stages. In the first, the substrate binds reversibly to the enzyme, forming the enzyme-substrate complex. This is sometimes called the Michaelis–Menten complex in their honor. The enzyme then catalyzes the chemical step in the reaction and releases the product. This work was further developed by G. E. Briggs and J. B. S. Haldane, who derived kinetic equations that are still widely used today.[70]

Enzyme rates depend on solution conditions and substrate concentration. To find the maximum speed of an enzymatic reaction, the substrate concentration is increased until a constant rate of product formation is seen. This is shown in the saturation curve on the right. Saturation happens because, as substrate concentration increases, more and more of the free enzyme is converted into the substrate-bound ES complex. At the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) of the enzyme, all the enzyme active sites are bound to substrate, and the amount of ES complex is the same as the total amount of enzyme.[1]: 8.4

Vmax is only one of several important kinetic parameters. The amount of substrate needed to achieve a given rate of reaction is also important. This is given by the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km), which is the substrate concentration required for an enzyme to reach one-half its maximum reaction rate; generally, each enzyme has a characteristic KM for a given substrate. Another useful constant is kcat, also called the turnover number, which is the number of substrate molecules handled by one active site per second.[1]: 8.4

The efficiency of an enzyme can be expressed in terms of kcat/Km. This is also called the specificity constant and incorporates the rate constants for all steps in the reaction up to and including the first irreversible step. Because the specificity constant reflects both affinity and catalytic ability, it is useful for comparing different enzymes against each other, or the same enzyme with different substrates. The theoretical maximum for the specificity constant is called the diffusion limit and is about 108 to 109 (M−1 s−1). At this point every collision of the enzyme with its substrate will result in catalysis, and the rate of product formation is not limited by the reaction rate but by the diffusion rate. Enzymes with this property are called catalytically perfect or kinetically perfect. Example of such enzymes are triose-phosphate isomerase, carbonic anhydrase, acetylcholinesterase, catalase, fumarase, β-lactamase, and superoxide dismutase.[1]: 8.4.2 The turnover of such enzymes can reach several million reactions per second.[1]: 9.2 But most enzymes are far from perfect: the average values of and are about and , respectively.[71]

Michaelis–Menten kinetics relies on the law of mass action, which is derived from the assumptions of free diffusion and thermodynamically driven random collision. Many biochemical or cellular processes deviate significantly from these conditions, because of macromolecular crowding and constrained molecular movement.[72] More recent, complex extensions of the model attempt to correct for these effects.[73]

Inhibition

[edit]Enzyme reaction rates can be decreased by various types of enzyme inhibitors.[74]: 73–74

Types of inhibition

[edit]Competitive

[edit]A competitive inhibitor and substrate cannot bind to the enzyme at the same time.[75] Often competitive inhibitors strongly resemble the real substrate of the enzyme. For example, the drug methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, which catalyzes the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate.[76] The similarity between the structures of dihydrofolate and this drug are shown in the accompanying figure. This type of inhibition can be overcome with high substrate concentration. In some cases, the inhibitor can bind to a site other than the binding-site of the usual substrate and exert an allosteric effect to change the shape of the usual binding-site.[77]

Non-competitive

[edit]A non-competitive inhibitor binds to a site other than where the substrate binds. The substrate still binds with its usual affinity and hence Km remains the same. However the inhibitor reduces the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme so that Vmax is reduced. In contrast to competitive inhibition, non-competitive inhibition cannot be overcome with high substrate concentration.[74]: 76–78

Uncompetitive

[edit]An uncompetitive inhibitor cannot bind to the free enzyme, only to the enzyme-substrate complex; hence, these types of inhibitors are most effective at high substrate concentration. In the presence of the inhibitor, the enzyme-substrate complex is inactive.[74]: 78 This type of inhibition is rare.[78]

Mixed

[edit]A mixed inhibitor binds to an allosteric site and the binding of the substrate and the inhibitor affect each other. The enzyme's function is reduced but not eliminated when bound to the inhibitor. This type of inhibitor does not follow the Michaelis–Menten equation.[74]: 76–78

Irreversible

[edit]An irreversible inhibitor permanently inactivates the enzyme, usually by forming a covalent bond to the protein.[79] Penicillin[80] and aspirin[81] are common drugs that act in this manner.

Functions of inhibitors

[edit]In many organisms, inhibitors may act as part of a feedback mechanism. If an enzyme produces too much of one substance in the organism, that substance may act as an inhibitor for the enzyme at the beginning of the pathway that produces it, causing production of the substance to slow down or stop when there is sufficient amount. This is a form of negative feedback. Major metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle make use of this mechanism.[1]: 17.2.2

Since inhibitors modulate the function of enzymes they are often used as drugs. Many such drugs are reversible competitive inhibitors that resemble the enzyme's native substrate, similar to methotrexate above; other well-known examples include statins used to treat high cholesterol,[82] and protease inhibitors used to treat retroviral infections such as HIV.[83] A common example of an irreversible inhibitor that is used as a drug is aspirin, which inhibits the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes that produce the inflammation messenger prostaglandin.[81] Other enzyme inhibitors are poisons. For example, the poison cyanide is an irreversible enzyme inhibitor that combines with the copper and iron in the active site of the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase and blocks cellular respiration.[84]

Factors affecting enzyme activity

[edit]As enzymes are made up of proteins, their actions are sensitive to change in many physio chemical factors such as pH, temperature, substrate concentration, etc.

The following table shows pH optima for various enzymes.[85]

| Enzyme | Optimum pH | pH description |

|---|---|---|

| Pepsin | 1.5–1.6 | Highly acidic |

| Invertase | 4.5 | Acidic |

| Lipase (stomach) | 4.0–5.0 | Acidic |

| Lipase (castor oil) | 4.7 | Acidic |

| Lipase (pancreas) | 8.0 | Alkaline |

| Amylase (malt) | 4.6–5.2 | Acidic |

| Amylase (pancreas) | 6.7–7.0 | Acidic-neutral |

| Cellobiase | 5.0 | Acidic |

| Maltase | 6.1–6.8 | Acidic |

| Sucrase | 6.2 | Acidic |

| Catalase | 7.0 | Neutral |

| Urease | 7.0 | Neutral |

| Cholinesterase | 7.0 | Neutral |

| Ribonuclease | 7.0–7.5 | Neutral |

| Fumarase | 7.8 | Alkaline |

| Trypsin | 7.8–8.7 | Alkaline |

| Adenosine triphosphate | 9.0 | Alkaline |

| Arginase | 10.0 | Highly alkaline |

Biological function

[edit]Enzymes serve a wide variety of functions inside living organisms. They are indispensable for signal transduction and cell regulation, often via kinases and phosphatases.[86] They also generate movement, with myosin hydrolyzing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to generate muscle contraction, and also transport cargo around the cell as part of the cytoskeleton.[87] Other ATPases in the cell membrane are ion pumps involved in active transport. Enzymes are also involved in more exotic functions, such as luciferase generating light in fireflies.[88] Viruses can also contain enzymes for infecting cells, such as the HIV integrase and reverse transcriptase, or for viral release from cells, like the influenza virus neuraminidase.[89]

An important function of enzymes is in the digestive systems of animals. Enzymes such as amylases and proteases break down large molecules (starch or proteins, respectively) into smaller ones, so they can be absorbed by the intestines. Starch molecules, for example, are too large to be absorbed from the intestine, but enzymes hydrolyze the starch chains into smaller molecules such as maltose and eventually glucose, which can then be absorbed. Different enzymes digest different food substances. In ruminants, which have herbivorous diets, microorganisms in the gut produce another enzyme, cellulase, to break down the cellulose cell walls of plant fiber.[90]

Metabolism

[edit]

Several enzymes can work together in a specific order, creating metabolic pathways.[1]: 30.1 In a metabolic pathway, one enzyme takes the product of another enzyme as a substrate. After the catalytic reaction, the product is then passed on to another enzyme. Sometimes more than one enzyme can catalyze the same reaction in parallel; this can allow more complex regulation: with, for example, a low constant activity provided by one enzyme but an inducible high activity from a second enzyme.[91]

Enzymes determine what steps occur in these pathways. Without enzymes, metabolism would neither progress through the same steps and could not be regulated to serve the needs of the cell. Most central metabolic pathways are regulated at a few steps, typically through enzymes whose activity involves the phosphorylation by ATP. Because this reaction releases so much energy, other reactions that are thermodynamically unfavorable can be coupled to ATP hydrolysis, driving the overall series of linked metabolic reactions.[1]: 30.1

Control of activity

[edit]There are five main ways that enzyme activity is controlled in the cell.[1]: 30.1.1

Regulation

[edit]Enzymes can be either activated or inhibited by other molecules. For example, the end product(s) of a metabolic pathway are often inhibitors for one of the first enzymes of the pathway (usually the first irreversible step, called committed step), thus regulating the amount of end product made by the pathways. Such a regulatory mechanism is called a negative feedback mechanism, because the amount of the end product produced is regulated by its own concentration.[92]: 141–48 Negative feedback mechanism can effectively adjust the rate of synthesis of intermediate metabolites according to the demands of the cells. This helps with effective allocations of materials and energy economy, and it prevents the excess manufacture of end products. Like other homeostatic devices, the control of enzymatic action helps to maintain a stable internal environment in living organisms.[92]: 141

Post-translational modification

[edit]Examples of post-translational modification include phosphorylation, myristoylation and glycosylation.[92]: 149–69 For example, in the response to insulin, the phosphorylation of multiple enzymes, including glycogen synthase, helps control the synthesis or degradation of glycogen and allows the cell to respond to changes in blood sugar.[93] Another example of post-translational modification is the cleavage of the polypeptide chain. Chymotrypsin, a digestive protease, is produced in inactive form as chymotrypsinogen in the pancreas and transported in this form to the stomach where it is activated. This stops the enzyme from digesting the pancreas or other tissues before it enters the gut. This type of inactive precursor to an enzyme is known as a zymogen[92]: 149–53 or proenzyme.

Quantity

[edit]Enzyme production (transcription and translation of enzyme genes) can be enhanced or diminished by a cell in response to changes in the cell's environment. This form of gene regulation is called enzyme induction. For example, bacteria may become resistant to antibiotics such as penicillin because enzymes called beta-lactamases are induced that hydrolyse the crucial beta-lactam ring within the penicillin molecule.[94] Another example comes from enzymes in the liver called cytochrome P450 oxidases, which are important in drug metabolism. Induction or inhibition of these enzymes can cause drug interactions.[95] Enzyme levels can also be regulated by changing the rate of enzyme degradation.[1]: 30.1.1 The opposite of enzyme induction is enzyme repression.

Subcellular distribution

[edit]Enzymes can be compartmentalized, with different metabolic pathways occurring in different cellular compartments. For example, fatty acids are synthesized by one set of enzymes in the cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi and used by a different set of enzymes as a source of energy in the mitochondrion, through β-oxidation.[96] In addition, trafficking of the enzyme to different compartments may change the degree of protonation (e.g., the neutral cytoplasm and the acidic lysosome) or oxidative state (e.g., oxidizing periplasm or reducing cytoplasm) which in turn affects enzyme activity.[97] In contrast to partitioning into membrane bound organelles, enzyme subcellular localisation may also be altered through polymerisation of enzymes into macromolecular cytoplasmic filaments.[98][99]

Organ specialization

[edit]In multicellular eukaryotes, cells in different organs and tissues have different patterns of gene expression and therefore have different sets of enzymes (known as isozymes) available for metabolic reactions. This provides a mechanism for regulating the overall metabolism of the organism. For example, hexokinase, the first enzyme in the glycolysis pathway, has a specialized form called glucokinase expressed in the liver and pancreas that has a lower affinity for glucose yet is more sensitive to glucose concentration.[100] This enzyme is involved in sensing blood sugar and regulating insulin production.[101]

Involvement in disease

[edit]

Since the tight control of enzyme activity is essential for homeostasis, any malfunction (mutation, overproduction, underproduction or deletion) of a single critical enzyme can lead to a genetic disease. The malfunction of just one type of enzyme out of the thousands of types present in the human body can be fatal. An example of a fatal genetic disease due to enzyme insufficiency is Tay–Sachs disease, in which patients lack the enzyme hexosaminidase.[102][103]

One example of enzyme deficiency is the most common type of phenylketonuria. Many different single amino acid mutations in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, which catalyzes the first step in the degradation of phenylalanine, result in build-up of phenylalanine and related products. Some mutations are in the active site, directly disrupting binding and catalysis, but many are far from the active site and reduce activity by destabilising the protein structure, or affecting correct oligomerisation.[104][105] This can lead to intellectual disability if the disease is untreated.[106] Another example is pseudocholinesterase deficiency, in which the body's ability to break down choline ester drugs is impaired.[107] Oral administration of enzymes can be used to treat some functional enzyme deficiencies, such as pancreatic insufficiency[108] and lactose intolerance.[109]

Another way enzyme malfunctions can cause disease comes from germline mutations in genes coding for DNA repair enzymes. Defects in these enzymes cause cancer because cells are less able to repair mutations in their genomes. This causes a slow accumulation of mutations and results in the development of cancers. An example of such a hereditary cancer syndrome is xeroderma pigmentosum, which causes the development of skin cancers in response to even minimal exposure to ultraviolet light.[110][111]

Evolution

[edit]Similar to any other protein, enzymes change over time through mutations and sequence divergence. Given their central role in metabolism, enzyme evolution plays a critical role in adaptation. A key question is therefore whether and how enzymes can change their enzymatic activities alongside. It is generally accepted that many new enzyme activities have evolved through gene duplication and mutation of the duplicate copies although evolution can also happen without duplication. One example of an enzyme that has changed its activity is the ancestor of methionyl aminopeptidase (MAP) and creatine amidinohydrolase (creatinase) which are clearly homologous but catalyze very different reactions (MAP removes the amino-terminal methionine in new proteins while creatinase hydrolyses creatine to sarcosine and urea). In addition, MAP is metal-ion dependent while creatinase is not, hence this property was also lost over time.[112] Small changes of enzymatic activity are extremely common among enzymes. In particular, substrate binding specificity (see above) can easily and quickly change with single amino acid changes in their substrate binding pockets. This is frequently seen in the main enzyme classes such as kinases.[113]

Artificial (in vitro) evolution is now commonly used to modify enzyme activity or specificity for industrial applications (see below).

Industrial applications

[edit]Enzymes are used in the chemical industry and other industrial applications when extremely specific catalysts are required. Enzymes in general are limited in the number of reactions they have evolved to catalyze and also by their lack of stability in organic solvents and at high temperatures. As a consequence, protein engineering is an active area of research and involves attempts to create new enzymes with novel properties, either through rational design or in vitro evolution.[114][115] These efforts have begun to be successful, and a few enzymes have now been designed "from scratch" to catalyze reactions that do not occur in nature.[116]

| Application | Enzymes used | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Biofuel industry | Cellulases | Break down cellulose into sugars that can be fermented to produce cellulosic ethanol.[117] |

| Ligninases | Pretreatment of biomass for biofuel production.[117] | |

| Biological detergent | Proteases, amylases, lipases | Remove protein, starch, and fat or oil stains from laundry and dishware.[118] |

| Mannanases | Remove food stains from the common food additive guar gum.[118] | |

| Brewing industry | Amylase, glucanases, proteases | Split polysaccharides and proteins in the malt.[119]: 150–9 |

| Betaglucanases | Improve the wort and beer filtration characteristics.[119]: 545 | |

| Amyloglucosidase and pullulanases | Make low-calorie beer and adjust fermentability.[119]: 575 | |

| Acetolactate decarboxylase (ALDC) | Increase fermentation efficiency by reducing diacetyl formation.[120] | |

| Culinary uses | Papain | Tenderize meat for cooking.[121] |

| Dairy industry | Rennin | Hydrolyze protein in the manufacture of cheese.[122] |

| Lipases | Produce Camembert cheese and blue cheeses such as Roquefort.[123] | |

| Food processing | Amylases | Produce sugars from starch, such as in making high-fructose corn syrup.[124] |

| Proteases | Lower the protein level of flour, as in biscuit-making.[125] | |

| Trypsin | Manufacture hypoallergenic baby foods.[125] | |

| Cellulases, pectinases | Clarify fruit juices.[126] | |

| Molecular biology | Nucleases, DNA ligase and polymerases | Use restriction digestion and the polymerase chain reaction to create recombinant DNA.[1]: 6.2 |

| Paper industry | Xylanases, hemicellulases and lignin peroxidases | Remove lignin from kraft pulp.[127] |

| Personal care | Proteases | Remove proteins on contact lenses to prevent infections.[128] |

| Starch industry | Amylases | Convert starch into glucose and various syrups.[129] |

See also

[edit]Enzyme databases

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Stryer L, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL (2002). Biochemistry (5th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4955-6. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010.

- ^ Murphy JM, Farhan H, Eyers PA (April 2017). "Bio-Zombie: the rise of pseudoenzymes in biology". Biochemical Society Transactions. 45 (2): 537–544. doi:10.1042/bst20160400. PMID 28408493.

- ^ Murphy JM, Zhang Q, Young SN, Reese ML, Bailey FP, Eyers PA, et al. (January 2014). "A robust methodology to subclassify pseudokinases based on their nucleotide-binding properties". The Biochemical Journal. 457 (2): 323–334. doi:10.1042/BJ20131174. PMC 5679212. PMID 24107129.

- ^ Schomburg I, Chang A, Placzek S, Söhngen C, Rother M, Lang M, et al. (January 2013). "BRENDA in 2013: integrated reactions, kinetic data, enzyme function data, improved disease classification: new options and contents in BRENDA". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (Database issue): D764 – D772. doi:10.1093/nar/gks1049. PMC 3531171. PMID 23203881.

- ^ Philip Ball (21 January 2025). Jen Schwartz (ed.). "Mysterious Blobs Found inside Cells Are Rewriting the Story of How Life Works. Tiny specks called biomolecular condensates are leading to a new understanding of the cell". Scientific American. 332 (2 (February)).

Condensates can act as catalysts for biochemical reactions, even if their component proteins do not. This is because condensates create an interface between two phases, which sets up a gradient in concentrations—of ions for example, creating an electric field that can trigger reactions. The researchers have demonstrated condensate-induced catalysis of a wide range of biochemical reactions, including those involving hydrolysis (in which water splits other molecules apart).

- ^ Radzicka A, Wolfenden R (January 1995). "A proficient enzyme". Science. 267 (5194): 90–93. Bibcode:1995Sci...267...90R. doi:10.1126/science.7809611. PMID 7809611. S2CID 8145198.

- ^ Callahan BP, Miller BG (December 2007). "OMP decarboxylase--An enigma persists". Bioorganic Chemistry. 35 (6): 465–469. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.07.004. PMID 17889251.

- ^ de Réaumur RA (1752). "Observations sur la digestion des oiseaux". Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (in French). 1752: 266, 461.

- ^ Williams HS (1904). A History of Science: in Five Volumes. Volume IV: Modern Development of the Chemical and Biological Sciences. Harper and Brothers.

- ^ Payen A, Persoz JF (1833). "Mémoire sur la diastase, les principaux produits de ses réactions et leurs applications aux arts industriels" [Memoir on diastase, the principal products of its reactions, and their applications to the industrial arts]. Annales de chimie et de physique. 2nd (in French). 53: 73–92.

- ^ Manchester KL (December 1995). "Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)--chance and the prepared mind". Trends in Biotechnology. 13 (12): 511–515. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(00)89014-9. PMID 8595136.

- ^ Kühne coined the word "enzyme" in: Kühne W (1877). "Über das Verhalten verschiedener organisirter und sog. ungeformter Fermente" [On the behavior of various organized and so-called unformed ferments]. Verhandlungen des Naturhistorisch-medicinischen Vereins zu Heidelberg. new series (in German). 1 (3): 190–193. Relevant passage on page 190: "Um Missverständnissen vorzubeugen und lästige Umschreibungen zu vermeiden schlägt Vortragender vor, die ungeformten oder nicht organisirten Fermente, deren Wirkung ohne Anwesenheit von Organismen und ausserhalb derselben erfolgen kann, als Enzyme zu bezeichnen." (Translation: In order to obviate misunderstandings and avoid cumbersome periphrases, [the author, a university lecturer] suggests designating as "enzymes" the unformed or not organized ferments, whose action can occur without the presence of organisms and outside of the same.)

- ^ Holmes FL (2003). "Enzymes". In Heilbron JL (ed.). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 9780199743766.

- ^ "Eduard Buchner". Nobel Laureate Biography. Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "Eduard Buchner – Nobel Lecture: Cell-Free Fermentation". Nobelprize.org. 1907. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ The naming of enzymes by adding the suffix "-ase" to the substrate on which the enzyme acts, has been traced to French scientist Émile Duclaux (1840–1904), who intended to honor the discoverers of diastase – the first enzyme to be isolated – by introducing this practice in his book Duclaux E (1899). Traité de microbiologie: Diastases, toxines et venins [Microbiology Treatise: diastases, toxins and venoms] (in French). Paris, France: Masson and Co. See Chapter 1, especially page 9.

- ^ Willstätter R (1927). "Faraday lecture. Problems and methods in enzyme research". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 1359–1381. doi:10.1039/JR9270001359. quoted in Blow D (April 2000). "So do we understand how enzymes work?". Structure. 8 (4): R77 – R81. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00125-8. PMID 10801479.

- ^ "Nobel Prizes and Laureates: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1946". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Blake CC, Koenig DF, Mair GA, North AC, Phillips DC, Sarma VR (May 1965). "Structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Angstrom resolution". Nature. 206 (4986): 757–761. Bibcode:1965Natur.206..757B. doi:10.1038/206757a0. PMID 5891407. S2CID 4161467.

- ^ Johnson LN, Petsko GA (July 1999). "David Phillips and the origin of structural enzymology". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 24 (7): 287–289. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01423-1. PMID 10390620.

- ^ Moss GP. "Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes by the Reactions they Catalyse". International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Nomenclature Committee. "EC 2.7.1.1". International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB). School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Mulder NJ (28 September 2007). "Protein Family Databases". eLS. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. a0003058.pub2. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0003058.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^ Omelchenko MV, Galperin MY, Wolf YI, Koonin EV (April 2010). "Non-homologous isofunctional enzymes: a systematic analysis of alternative solutions in enzyme evolution". Biology Direct. 5 (1) 31. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-5-31. PMC 2876114. PMID 20433725.

- ^ Anfinsen CB (July 1973). "Principles that govern the folding of protein chains". Science. 181 (4096): 223–230. Bibcode:1973Sci...181..223A. doi:10.1126/science.181.4096.223. PMID 4124164.

- ^ Dunaway-Mariano D (November 2008). "Enzyme function discovery". Structure. 16 (11): 1599–1600. doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.10.001. PMID 19000810.

- ^ Petsko GA, Ringe D (2003). "Chapter 1: From sequence to structure". Protein structure and function. London: New Science. p. 27. ISBN 978-1405119221.

- ^ Chen LH, Kenyon GL, Curtin F, Harayama S, Bembenek ME, Hajipour G, et al. (September 1992). "4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase, an enzyme composed of 62 amino acid residues per monomer". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (25): 17716–17721. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)37101-7. PMID 1339435.

- ^ Smith S (December 1994). "The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes". FASEB Journal. 8 (15): 1248–1259. doi:10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001737. PMID 8001737. S2CID 22853095.

- ^ "The Catalytic Site Atlas". The European Bioinformatics Institute. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ a b Suzuki H (2015). "Chapter 7: Active Site Structure". How Enzymes Work: From Structure to Function. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 117–140. ISBN 978-981-4463-92-8.

- ^ Krauss G (2003). "The Regulations of Enzyme Activity". Biochemistry of Signal Transduction and Regulation (3rd ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 89–114. ISBN 9783527605767.

- ^ Jaeger KE, Eggert T (August 2004). "Enantioselective biocatalysis optimized by directed evolution". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 15 (4): 305–313. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2004.06.007. PMID 15358000.

- ^ Shevelev IV, Hübscher U (May 2002). "The 3' 5' exonucleases". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 3 (5): 364–376. doi:10.1038/nrm804. PMID 11988770. S2CID 31605786.

- ^ Zenkin N, Yuzenkova Y, Severinov K (July 2006). "Transcript-assisted transcriptional proofreading". Science. 313 (5786): 518–520. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..518Z. doi:10.1126/science.1127422. PMID 16873663. S2CID 40772789.

- ^ Ibba M, Soll D (2000). "Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 69: 617–650. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. PMID 10966471.

- ^ Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W (2001). "Fidelity of aminoacyl-tRNA selection on the ribosome: kinetic and structural mechanisms". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 70: 415–435. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.415. PMID 11395413.

- ^ Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS (2010). "Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 79: 471–505. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143718. PMID 20235827.

- ^ O'Brien PJ, Herschlag D (April 1999). "Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities". Chemistry & Biology. 6 (4): R91 – R105. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80033-7. PMID 10099128.

- ^ Fischer E (1894). "Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme" [Influence of configuration on the action of enzymes]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 27 (3): 2985–93. doi:10.1002/cber.18940270364. From page 2992: "Um ein Bild zu gebrauchen, will ich sagen, dass Enzym und Glucosid wie Schloss und Schlüssel zu einander passen müssen, um eine chemische Wirkung auf einander ausüben zu können." (To use an image, I will say that an enzyme and a glucoside [i.e., glucose derivative] must fit like a lock and key, in order to be able to exert a chemical effect on each other.)

- ^ Cooper GM (2000). "Chapter 2.2: The Central Role of Enzymes as Biological Catalysts". The Cell: a Molecular Approach (2nd ed.). Washington (DC ): ASM Press. ISBN 0-87893-106-6.

- ^ Koshland DE (February 1958). "Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 44 (2): 98–104. Bibcode:1958PNAS...44...98K. doi:10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. PMC 335371. PMID 16590179.

- ^ Vasella A, Davies GJ, Böhm M (October 2002). "Glycosidase mechanisms". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 6 (5): 619–629. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00380-0. PMID 12413546.

- ^ Boyer R (2002). "Chapter 6: Enzymes I, Reactions, Kinetics, and Inhibition". Concepts in Biochemistry (2nd ed.). New York, Chichester, Weinheim, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 137–8. ISBN 0-470-00379-0. OCLC 51720783.

- ^ Savir Y, Tlusty T (May 2007). Scalas E (ed.). "Conformational proofreading: the impact of conformational changes on the specificity of molecular recognition". PLOS ONE. 2 (5): e468. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..468S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000468. PMC 1868595. PMID 17520027.

- ^ Fersht A (1985). Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. pp. 50–2. ISBN 978-0-7167-1615-0.

- ^ Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, Xiang Y, Liu H, Olsson MH (August 2006). "Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis". Chemical Reviews. 106 (8): 3210–3235. doi:10.1021/cr0503106. PMID 16895325.

- ^ Cox MM, Nelson DL (2013). "Chapter 6.2: How enzymes work". Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (6th ed.). New York, N.Y.: W.H. Freeman. p. 195. ISBN 978-1464109621.

- ^ Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S (August 2003). "A perspective on enzyme catalysis". Science. 301 (5637): 1196–1202. Bibcode:2003Sci...301.1196B. doi:10.1126/science.1085515. PMID 12947189. S2CID 7899320.

- ^ Jencks WP (1987). Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. Mineola, N.Y: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65460-7.

- ^ Villa J, Strajbl M, Glennon TM, Sham YY, Chu ZT, Warshel A (October 2000). "How important are entropic contributions to enzyme catalysis?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (22): 11899–11904. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9711899V. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.22.11899. PMC 17266. PMID 11050223.

- ^ Polgár L (October 2005). "The catalytic triad of serine peptidases". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 62 (19–20): 2161–2172. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5160-x. PMC 11139141. PMID 16003488. S2CID 3343824.

- ^ Ramanathan A, Savol A, Burger V, Chennubhotla CS, Agarwal PK (January 2014). "Protein conformational populations and functionally relevant substates". Accounts of Chemical Research. 47 (1): 149–156. doi:10.1021/ar400084s. OSTI 1565147. PMID 23988159.

- ^ Weinreb E, McBride JM, Siek M, Rougemont J, Renault R, Peleg Y, et al. (28 March 2025). "Enzymes as viscoelastic catalytic machines". Nature Physics. 21 (5): 787–798. Bibcode:2025NatPh..21..787W. doi:10.1038/s41567-025-02825-9. ISSN 1745-2481.

- ^ Agrawal D, Budakoti M, Kumar V (September 2023). "Strategies and tools for the biotechnological valorization of glycerol to 1, 3-propanediol: Challenges, recent advancements and future outlook". Biotechnology Advances. 66 108177. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108177. hdl:1826/19759. PMID 37209955.

- ^ Selvy PE, Lavieri RR, Lindsley CW, Brown HA (October 2011). "Phospholipase D: enzymology, functionality, and chemical modulation". Chemical Reviews. 111 (10): 6064–6119. doi:10.1021/cr200296t. PMC 3233269. PMID 21936578.

- ^ Tsai CJ, Del Sol A, Nussinov R (March 2009). "Protein allostery, signal transmission and dynamics: a classification scheme of allosteric mechanisms". Molecular BioSystems. 5 (3): 207–216. doi:10.1039/b819720b. PMC 2898650. PMID 19225609.

- ^ Changeux JP, Edelstein SJ (June 2005). "Allosteric mechanisms of signal transduction". Science. 308 (5727): 1424–1428. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1424C. doi:10.1126/science.1108595. PMID 15933191. S2CID 10621930.

- ^ de Bolster MW (1997). "Glossary of Terms Used in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Cofactor". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- ^ Voet D, Voet J, Pratt C (2016). Fundamentals of Biochemistry. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-118-91840-1.

- ^ Chapman-Smith A, Cronan JE (September 1999). "The enzymatic biotinylation of proteins: a post-translational modification of exceptional specificity". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 24 (9): 359–363. doi:10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01438-3. PMID 10470036.

- ^ Fisher Z, Hernandez Prada JA, Tu C, Duda D, Yoshioka C, An H, et al. (February 2005). "Structural and kinetic characterization of active-site histidine as a proton shuttle in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II". Biochemistry. 44 (4): 1097–1105. doi:10.1021/bi0480279. PMID 15667203.

- ^ a b Wagner AL (1975). Vitamins and Coenzymes. Krieger Pub Co. ISBN 0-88275-258-8.

- ^ "BRENDA The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System". Technische Universität Braunschweig. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ Törnroth-Horsefield S, Neutze R (December 2008). "Opening and closing the metabolite gate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (50): 19565–19566. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10519565T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810654106. PMC 2604989. PMID 19073922.

- ^ McArdle WD, Katch F, Katch VL (2006). "Chapter 9: The Pulmonary System and Exercise". Essentials of Exercise Physiology (3rd ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 312–3. ISBN 978-0781749916.

- ^ Ferguson SJ, Nicholls D, Ferguson S (2002). Bioenergetics 3 (3rd ed.). San Diego: Academic. ISBN 0-12-518121-3.

- ^ Bisswanger H (2017). Enzyme kinetics : principles and methods (Third, enlarged and improved ed.). Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 9783527806461. OCLC 992976641.

- ^ Michaelis L, Menten M (1913). "Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung" [The Kinetics of Invertase Action]. Biochem. Z. (in German). 49: 333–369.; Michaelis L, Menten ML, Johnson KA, Goody RS (October 2011). "The original Michaelis constant: translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten paper". Biochemistry. 50 (39): 8264–8269. doi:10.1021/bi201284u. PMC 3381512. PMID 21888353.

- ^ Briggs GE, Haldane JB (1925). "A Note on the Kinetics of Enzyme Action". The Biochemical Journal. 19 (2): 338–339. doi:10.1042/bj0190338. PMC 1259181. PMID 16743508.

- ^ Bar-Even A, Noor E, Savir Y, Liebermeister W, Davidi D, Tawfik DS, et al. (May 2011). "The moderately efficient enzyme: evolutionary and physicochemical trends shaping enzyme parameters". Biochemistry. 50 (21): 4402–4410. doi:10.1021/bi2002289. PMID 21506553.

- ^ Ellis RJ (October 2001). "Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 26 (10): 597–604. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01938-7. PMID 11590012.

- ^ Kopelman R (September 1988). "Fractal reaction kinetics". Science. 241 (4873): 1620–1626. Bibcode:1988Sci...241.1620K. doi:10.1126/science.241.4873.1620. PMID 17820893. S2CID 23465446.

- ^ a b c d Cornish-Bowden A (2004). Fundamentals of Enzyme Kinetics (3 ed.). London: Portland Press. ISBN 1-85578-158-1.

- ^ Price NC (1979). "What is meant by 'competitive inhibition'?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 4 (11): N272 – N273. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(79)90205-6.

- ^ Goodsell DS (1 August 1999). "The molecular perspective: methotrexate". The Oncologist. 4 (4): 340–341. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.4-4-340. PMID 10476546.

- ^ Wu P, Clausen MH, Nielsen TE (December 2015). "Allosteric small-molecule kinase inhibitors" (PDF). Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 156: 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.10.002. PMID 26478442. S2CID 1550698.

- ^ Cornish-Bowden A (July 1986). "Why is uncompetitive inhibition so rare? A possible explanation, with implications for the design of drugs and pesticides". FEBS Letters. 203 (1): 3–6. Bibcode:1986FEBSL.203....3C. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(86)81424-7. PMID 3720956. S2CID 45356060.

- ^ Strelow JM (January 2017). "A Perspective on the Kinetics of Covalent and Irreversible Inhibition". SLAS Discovery. 22 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1177/1087057116671509. PMID 27703080.

- ^ Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S (February 2005). "Bacterial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics: compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity". Chemical Reviews. 105 (2): 395–424. doi:10.1021/cr030102i. PMID 15700950.

- ^ a b Johnson DS, Weerapana E, Cravatt BF (June 2010). "Strategies for discovering and derisking covalent, irreversible enzyme inhibitors". Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2 (6): 949–964. doi:10.4155/fmc.10.21. PMC 2904065. PMID 20640225.

- ^ Endo A (November 1992). "The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors". Journal of Lipid Research. 33 (11): 1569–1582. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)41379-3. PMID 1464741.

- ^ Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J (1998). "Inhibitors of HIV-1 protease: a major success of structure-assisted drug design". Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 27: 249–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.249. PMID 9646869. S2CID 10205781.

- ^ Yoshikawa S, Caughey WS (May 1990). "Infrared evidence of cyanide binding to iron and copper sites in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Implications regarding oxygen reduction". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (14): 7945–7958. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)39023-4. PMID 2159465.

- ^ Jain JL (May 1999). Fundamentals of biochemistry. New Delhi: S. Chand and Co. ISBN 8121903432. OCLC 818809626.

- ^ Hunter T (January 1995). "Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling". Cell. 80 (2): 225–236. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90405-0. PMID 7834742. S2CID 13999125.

- ^ Berg JS, Powell BC, Cheney RE (April 2001). "A millennial myosin census". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 12 (4): 780–794. doi:10.1091/mbc.12.4.780. PMC 32266. PMID 11294886.

- ^ Meighen EA (March 1991). "Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence". Microbiological Reviews. 55 (1): 123–142. doi:10.1128/MMBR.55.1.123-142.1991. PMC 372803. PMID 2030669.

- ^ De Clercq E (April 2002). "Highlights in the development of new antiviral agents". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2 (2): 163–175. doi:10.2174/1389557024605474. PMID 12370077.

- ^ Mackie RI, White BA (October 1990). "Recent advances in rumen microbial ecology and metabolism: potential impact on nutrient output". Journal of Dairy Science. 73 (10): 2971–2995. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78986-2. PMID 2178174.

- ^ Rouzer CA, Marnett LJ (April 2009). "Cyclooxygenases: structural and functional insights". Journal of Lipid Research. 50 (Suppl): S29 – S34. doi:10.1194/jlr.R800042-JLR200. PMC 2674713. PMID 18952571.

- ^ a b c d Suzuki H (2015). "Chapter 8: Control of Enzyme Activity". How Enzymes Work: From Structure to Function. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 141–69. ISBN 978-981-4463-92-8.

- ^ Doble BW, Woodgett JR (April 2003). "GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase". Journal of Cell Science. 116 (Pt 7): 1175–1186. doi:10.1242/jcs.00384. PMC 3006448. PMID 12615961.

- ^ Bennett PM, Chopra I (February 1993). "Molecular basis of beta-lactamase induction in bacteria". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 37 (2): 153–158. doi:10.1128/aac.37.2.153. PMC 187630. PMID 8452343.

- ^ Skett P, Gibson GG (2001). "Chapter 3: Induction and Inhibition of Drug Metabolism". Introduction to Drug Metabolism (3 ed.). Cheltenham, UK: Nelson Thornes Publishers. pp. 87–118. ISBN 978-0748760114.

- ^ Faergeman NJ, Knudsen J (April 1997). "Role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in the regulation of metabolism and in cell signalling". The Biochemical Journal. 323 (Pt 1): 1–12. doi:10.1042/bj3230001. PMC 1218279. PMID 9173866.

- ^ Suzuki H (2015). "Chapter 4: Effect of pH, Temperature, and High Pressure on Enzymatic Activity". How Enzymes Work: From Structure to Function. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 53–74. ISBN 978-981-4463-92-8.

- ^ Noree C, Sato BK, Broyer RM, Wilhelm JE (August 2010). "Identification of novel filament-forming proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster". The Journal of Cell Biology. 190 (4): 541–551. doi:10.1083/jcb.201003001. PMC 2928026. PMID 20713603.

- ^ Aughey GN, Liu JL (2015). "Metabolic regulation via enzyme filamentation". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 51 (4): 282–293. doi:10.3109/10409238.2016.1172555. PMC 4915340. PMID 27098510.

- ^ Kamata K, Mitsuya M, Nishimura T, Eiki J, Nagata Y (March 2004). "Structural basis for allosteric regulation of the monomeric allosteric enzyme human glucokinase". Structure. 12 (3): 429–438. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.02.005. PMID 15016359.

- ^ Froguel P, Zouali H, Vionnet N, Velho G, Vaxillaire M, Sun F, et al. (March 1993). "Familial hyperglycemia due to mutations in glucokinase. Definition of a subtype of diabetes mellitus". The New England Journal of Medicine. 328 (10): 697–702. doi:10.1056/NEJM199303113281005. PMID 8433729.

- ^ Okada S, O'Brien JS (August 1969). "Tay-Sachs disease: generalized absence of a beta-D-N-acetylhexosaminidase component". Science. 165 (3894): 698–700. Bibcode:1969Sci...165..698O. doi:10.1126/science.165.3894.698. PMID 5793973. S2CID 8473726.

- ^ "Learning About Tay–Sachs Disease". U.S. National Human Genome Research Institute. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Erlandsen H, Stevens RC (October 1999). "The structural basis of phenylketonuria". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 68 (2): 103–125. doi:10.1006/mgme.1999.2922. PMID 10527663.

- ^ Flatmark T, Stevens RC (August 1999). "Structural Insight into the Aromatic Amino Acid Hydroxylases and Their Disease-Related Mutant Forms". Chemical Reviews. 99 (8): 2137–2160. doi:10.1021/cr980450y. PMID 11849022.

- ^ "Phenylketonuria". Genes and Disease [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). 1998–2015.

- ^ "Pseudocholinesterase deficiency". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Fieker A, Philpott J, Armand M (2011). "Enzyme replacement therapy for pancreatic insufficiency: present and future". Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 4: 55–73. doi:10.2147/CEG.S17634. PMC 3132852. PMID 21753892.

- ^ Misselwitz B, Pohl D, Frühauf H, Fried M, Vavricka SR, Fox M (June 2013). "Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment". United European Gastroenterology Journal. 1 (3): 151–159. doi:10.1177/2050640613484463. PMC 4040760. PMID 24917953.

- ^ Cleaver JE (May 1968). "Defective repair replication of DNA in xeroderma pigmentosum". Nature. 218 (5142): 652–656. Bibcode:1968Natur.218..652C. doi:10.1038/218652a0. PMID 5655953. S2CID 4171859.

- ^ James WD, Elston D, Berger TG (2011). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (11th ed.). London: Saunders/ Elsevier. p. 567. ISBN 978-1437703146.

- ^ Murzin AG (November 1993). "Can homologous proteins evolve different enzymatic activities?". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 18 (11): 403–405. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(93)90132-7. PMID 8291080.

- ^ Ochoa D, Bradley D, Beltrao P (February 2018). "Evolution, dynamics and dysregulation of kinase signalling". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 48: 133–140. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2017.12.008. PMID 29316484.

- ^ Renugopalakrishnan V, Garduño-Juárez R, Narasimhan G, Verma CS, Wei X, Li P (November 2005). "Rational design of thermally stable proteins: relevance to bionanotechnology". Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 5 (11): 1759–1767. doi:10.1166/jnn.2005.441. PMID 16433409.

- ^ Hult K, Berglund P (August 2003). "Engineered enzymes for improved organic synthesis". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 14 (4): 395–400. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00095-8. PMID 12943848.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, Doyle L, Röthlisberger D, Zanghellini A, et al. (March 2008). "De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes". Science. 319 (5868): 1387–1391. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ a b Sun Y, Cheng J (May 2002). "Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials for ethanol production: a review". Bioresource Technology. 83 (1): 1–11. Bibcode:2002BiTec..83....1S. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00212-7. PMID 12058826.

- ^ a b Kirk O, Borchert TV, Fuglsang CC (August 2002). "Industrial enzyme applications". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 13 (4): 345–351. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00328-2. PMID 12323357.

- ^ a b c Briggs DE (1998). Malts and Malting (1st ed.). London: Blackie Academic. ISBN 978-0412298004.

- ^ Dulieu C, Moll M, Boudrant J, Poncelet D (2000). "Improved performances and control of beer fermentation using encapsulated alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase and modeling". Biotechnology Progress. 16 (6): 958–965. doi:10.1021/bp000128k. PMID 11101321. S2CID 25674881.

- ^ Tarté R (2008). Ingredients in Meat Products Properties, Functionality and Applications. New York: Springer. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-387-71327-4.

- ^ "Chymosin – GMO Database". GMO Compass. European Union. 10 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Molimard P, Spinnler HE (February 1996). "Review: Compounds Involved in the Flavor of Surface Mold-Ripened Cheeses: Origins and Properties". Journal of Dairy Science. 79 (2): 169–184. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76348-8.

- ^ Guzmán-Maldonado H, Paredes-López O (September 1995). "Amylolytic enzymes and products derived from starch: a review". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 35 (5): 373–403. doi:10.1080/10408399509527706. PMID 8573280.

- ^ a b "Protease – GMO Database". GMO Compass. European Union. 10 July 2010. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Alkorta I, Garbisu C, Llama MJ, Serra JL (January 1998). "Industrial applications of pectic enzymes: a review". Process Biochemistry. 33 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1016/S0032-9592(97)00046-0.

- ^ Bajpai P (March 1999). "Application of enzymes in the pulp and paper industry". Biotechnology Progress. 15 (2): 147–157. doi:10.1021/bp990013k. PMID 10194388. S2CID 26080240.

- ^ Begley CG, Paragina S, Sporn A (March 1990). "An analysis of contact lens enzyme cleaners". Journal of the American Optometric Association. 61 (3): 190–194. PMID 2186082.

- ^ Farris PL (2009). "Economic Growth and Organization of the U.S. Starch Industry". In BeMiller JN, Whistler RL (eds.). Starch Chemistry and Technology (3rd ed.). London: Academic. ISBN 9780080926551.

Further reading

[edit]

|

|

External links

[edit] Media related to Enzymes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Enzymes at Wikimedia Commons

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}+{}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} {}\mathrel {\xrightarrow {\text{Carbonic anhydrase}} } {}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cb4c8837b26e96fe552c17d863f93e0618cd998b)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}+{}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} {}\mathrel {\xleftarrow {\text{Carbonic anhydrase}} } {}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/618e95485aa1c3c44a29c557ac448ae5b544ff07)