Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Early Muslim conquests

View on Wikipedia

| Early Muslim conquests | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Expansion under Muhammad, 622–632

Expansion under the Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661

Expansion under the Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests (Arabic: الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, romanized: al-Futūḥāt al-ʾIslāmiyya),[3] also known as the Arab conquests,[4] were a series of wars initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the prophet of Islam. He established the first Islamic state in Medina, Arabia that expanded rapidly under the Rashidun Caliphate and the Umayyad Caliphate, culminating in Muslim rule being established in Asia, Northern Africa, and Southern Europe over the following century. According to historian James Buchan: "In speed and extent, the first Arab conquests were matched only by those of Alexander the Great, and they were more lasting."[5] At their height, the territory that was conquered by the Arab Muslims stretched from Iberia (at the Pyrenees) in the west to India (at Sind) in the east; Muslim control spanned Sicily, most of the Middle East and North Africa, and the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Among other drastic changes, the early Muslim conquests brought about the collapse of the Sasanian Empire and great territorial losses for the Byzantine Empire. Explanations for the Muslim victories have been difficult to discover, primarily because only fragmentary sources have survived from the period. American scholar Fred McGraw Donner suggests that Muhammad's establishment of an Islamic state in Arabia coupled with ideological (i.e., religious) coherence and mobilization constituted the main factor that propelled the early Muslim armies to successfully establish, in the timespan of roughly a century, one of the largest empires in history. Estimates of the total area of the combined territory held by the early Muslim polities at the conquests' peak have been as high as 13,000,000 square kilometres (5,000,000 sq mi).[6] Most historians also agree that, as another primary factor determining the early Muslim conquests' success, the Sasanians and the Byzantines were militarily and economically exhausted from decades of warfare against each other.[7]

It has been suggested that Jews and some Christians in Sasanian and Byzantine territory were dissatisfied and welcomed the invading Muslim troops, largely because of religious conflict in both empires.[8] However, confederations of Arab Christians, including the Ghassanids, initially allied themselves with the Byzantines. There were also instances of alliances between the Sasanians and the Byzantines, such as when they fought together against the Rashidun army during the Battle of Firaz.[9][10] Some of the lands lost by the Byzantines to the Muslims (namely Egypt, Palestine, and Syria) had been reclaimed from the Sasanians only a few years prior to the Muslim conquests.

Background

[edit]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

[edit]Arabia was a region that hosted several cultures, some urban and others nomadic Bedouin.[11] Arabian society was divided along tribal and clan lines, with the most important divisions being between the "southern" and "northern" tribal associations.[12] Both the Byzantine and Sasanian empires competed for influence in Arabia by sponsoring clients; in turn, Arabian tribes sought the patronage of the two rival empires to bolster their own ambitions.[12] The Lakhmid kingdom, which covered parts of what is now southern Iraq and northern Saudi Arabia was a client of Persia, and in 602 the Persians deposed the Lakhmids to take over the defense of the southern frontier.[13] This left the Persians exposed and overextended, helping to set the stage for the collapse of the Persian Empire later that century.[14] Southern Arabia—especially what is now—Yemen, had for thousands of years been a wealthy region that had been a center of the spice trade.[14] Yemen had been at the center of an international trading network linking Eurasia to Africa, and Yemen. It had been visited by merchants from East Africa, Europe, the Middle East, India and even from as far away as China.[14] In turn, the Yemeni were skilled sailors, travelling up the Red Sea to Egypt and across the Indian Ocean to India and down the east African coast.[14] Inland, the valleys of Yemen had been cultivated by a system of irrigation that had been set back when the Marib Dam was destroyed by an earthquake in about 450 AD.[14] Frankincense and myrrh had been greatly valued in the Mediterranean region, being used in religious ceremonies. However, the conversion of the Mediterranean world to Christianity had significantly reduced the demand for these commodities, causing a major economic slump in southern Arabia which helped to create the impression that Arabia was a backward region.[14]

Little is known of the pre-Islamic religions of Arabia, but it is known that the Arabs worshipped gods such as al-Lāt, Manat, al-Uzza, and Hubal, with the supreme deity in their pantheon being Allah (God).[15] There were also Jewish and Christian communities in Arabia, particularly in regions like Yemen and Najran, and aspects of Arab culture and religious practices reflected their influence.[15] Arabian society during this time was primarily tribal, with strong kinship ties and a code of honor known as murūwah, which emphasized bravery, loyalty, and hospitality.[16]

Pilgrimage was a significant part of Arabian religious life, and one of the most important pilgrimage sites was Mecca, which housed the Kaaba, considered a sacred sanctuary.[15] The Kaʿbah was a central site of worship and was surrounded by 360 idols representing various deities.[17] The region also had an annual fair and market called Ukāẓ, where tribes gathered for trade, poetry competitions, and diplomacy.[18] Poetry was a vital cultural element, with poets serving as both entertainers and historians, preserving the oral traditions of their tribes.[19]

The Arabian Peninsula served as a hub for trade routes connecting the Roman Empire, Persian Empire, Byzantine Empire, and Indian subcontinent. The cities of Mecca and Medina—then known as Yathrib—prospered due to their strategic location along these trade routes.[20] Mecca, in particular, was an important commercial center and a place of truce where violence was prohibited, especially during the pilgrimage season.[21]

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad, a merchant from Mecca, began receiving revelations through the archangel Gabriel, in which he was told that he was the last of the prophets, completing the message of monotheism brought by prophets such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus (known as Isa in Islam).[22] His teachings emphasized the worship of one God (Allah) and social justice, which brought him into conflict with the elite of Mecca, who opposed his message.[22]

After facing persecution, Muhammad and his followers migrated to the city of Yathrib, which became known as Medina ("City of Light, or the Luminous City").[22] In Medina, Muhammad established the first Islamic state based on faith, law, and mutual support.[23] By 630 CE, Muhammad and his followers returned to Mecca and took control of the city, cleansing the Kaaba of its idols and dedicating it solely to the worship of Allah.[22]

Byzantine–Sasanian Wars

[edit]

The prolonged and escalating Byzantine–Sasanian wars of the 6th and 7th centuries and the recurring outbreaks of bubonic plague (Plague of Justinian) left both empires exhausted and weakened in the face of the sudden emergence and expansion of the Arabs. The last of these wars ended with victory for the Byzantines: Emperor Heraclius regained all lost territories and restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in 629.[24] The war against Zoroastrian Persia, whose people worshiped the fire god Ahura Mazda, had been portrayed by Heraclius as a holy war in defense of the Christian faith and the Wood of the Holy Cross, as splinters of wood said to be from the True Cross were known, had been used to inspire Christian fighting zeal.[25] The idea of a holy war against the "fire worshipers", as the Christians called the Zoroastrians, had aroused much enthusiasm, leading to an all-out effort to defeat the Persians.[25]

Nevertheless, neither empire was given any chance to recover, as within a few years they were overrun by the advances of the Arabs (newly united by Islam), which, according to James Howard-Johnston, "can only be likened to a human tsunami".[26][27] According to George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Persian conflict opened the way for Islam".[28]

Arab invasion

[edit]In late 620s Muhammad had already managed to conquer and unify much of Arabia under Muslim rule, and it was under his leadership that the first Muslim-Byzantine skirmishes took place in response to Byzantine incursions. Just a few months after Heraclius and the Persian general Shahrbaraz agreed on terms for the withdrawal of Persian troops from occupied Byzantine eastern provinces in 629, Arab and Byzantine troops confronted each other at the Battle of Mu'tah as a result of Byzantine vassals murdering a Muslim emissary.[29] Muhammad died in 632 and was succeeded by Abu Bakr, the first caliph with undisputed control of the entire Arab peninsula after the successful Ridda Wars, which resulted in the consolidation of a powerful Muslim state throughout the peninsula.[30]

Byzantine sources, such as Short History written by Nikephoros, claim that the Arab invasion came about as a result of restrictions imposed on Arab traders curtailing their ability to trade within Byzantine territory, and to send the profits of their trade out of Byzantine territory. As a result, the Arabs murdered a Byzantine official named Sergius whom they held responsible for convincing the Emperor Heraclius to impose the trade restrictions. Nikephoros relates that:

The Saracens, having flayed a camel, enclosed him in the hide and sewed it up. As the skin hardened, the man who was left inside also withered and so perished in a painful manner. The charge against him was that he had persuaded Heraclius not to allow the Saracens to trade from the Byzantine country and send out of the Byzantine state the thirty pounds of gold which they normally received by way of commercial gain; and for this reason they began to lay waste the Byzantine land.[31]

Some scholars assert that this is the same Sergius, called "the Candidatus", who was "killed by the Saracens" as related in the 7th century Doctrina Jacobi document.[31]

Armies

[edit]Arab

[edit]In Arabia, swords from India were greatly esteemed as being made of the finest steel and were the favorite weapons of the Mujahideen.[32] The Arab sword known as the sayfy closely resembled the Byzantine gladius.[22] Swords and spears were the major weapons of the Muslims, and armour was either mail or leather.[32]

In northern Arabia, Byzantine influence predominated; in eastern Arabia, Persian influence predominated; and in Yemen, Indian influence was felt.[32] As the caliphate spread, the Muslims were influenced by the peoples they conquered—the Turkic peoples in Central Asia, the Persians, and the Byzantines in Syria.[33] The Bedouin tribes of Arabia favored archery, though contrary to popular belief Bedouin archers usually fought on foot instead of horseback.[34] The Arabs usually fought defensive battles with their archers placed on both flanks.[35]

By the Umayyad period, the caliphate had a standing army, including the elite Ahl al-Sham ("people of Syria"), raised from the Arabs who settled in Syria.[36] The caliphate was divided into jund, or regional armies, stationed in the provinces being made of mostly Arab tribes who were paid monthly by the Diwan al-Jaysh (War Ministry).[36]

Byzantine

[edit]

The infantry of the Byzantine army continued to be recruited from within the Byzantine Empire, but much of the cavalry were either recruited from "martial" peoples in the Balkans or in Asia Minor or alternatively were Germanic mercenaries.[37] Most of the Byzantine troops in Syria were indigenae (local), and it seems that at the time of the Muslim conquest, the Byzantine forces in Syria were Arabs.[38] In response to the loss of Syria, the Byzantines developed the phylarch system of using Armenian and Arab Christian auxiliaries living on the frontier to provide a "shield" to counter raiding by the Muslims into the empire.[39] Overall, the Byzantine army remained a small but professional force of foederati.[40] Unlike the foederati who were sent where they were needed, the stradioti lived in the frontier provinces.[41]

Persian

[edit]During the last decades of the Sasanian empire, the frequent use of royal titles by Persian governors in Central Asia, especially in what is now Afghanistan, indicates a weakening of the power of the Shahinshah (King of Kings), suggesting the empire was already breaking down at the time of the Muslim conquest.[42] Persian society was rigidly divided into castes with the nobility being of supposed "Aryan" descent, and this division of Persian society along caste lines was reflected in the military.[42] The azatan aristocracy provided the cavalry, the paighan infantry came from the peasantry and most of the greater Persian nobility had slave soldiers, this last being based on the Persian example.[42] Much of the Persian army consisted of tribal mercenaries recruited from the plains south of the Caspian Sea and from what is now Afghanistan.[43] The Persian tactics were cavalry based with the Persian forces usually divided into a center, based upon a hill, and two wings of cavalry on either side.[44]

Ethiopian

[edit]Little is known about the military forces of the Christian state of Ethiopia other than that they were divided into sarawit professional troops and the ehzab auxiliaries.[44] The Ethiopians made much use of camels and elephants.[44]

Berber

[edit]The Berber peoples of North Africa had often served as a federates (auxiliaries) to the Byzantine Army.[45] The Berber forces were based around the horse and camel but seemed to have been hampered by a lack of weapons or protection, with both Byzantine and Arab sources mentioning the Berbers lacked armour and helmets.[45] The Berbers went to war with their entire communities, and the presence of women and children both slowed down the Berber armies and tied down Berber tribesmen who tried to protect their families.[45]

Turkic

[edit]The British historian David Nicolle called the Turkic peoples of Central Asia the "most formidable foes" faced by the Muslims.[46] The Jewish Turkic Khazar khanate, based in what is now southern Russia and Ukraine, had a powerful heavy cavalry.[46] The Turkic heartland of Central Asia was divided into five khanates whose khans variously recognized the shahs of Iran or the emperors of China as their overlords.[47]

Turkic society was feudal with the khans only being pater primus among the aristocracy of dihquans who lived in castles in the countryside, with the rest of Turkic forces being divided into kadivar (farmers), khidmatgar (servants) and atbai (clients).[47] The heavily armored Turkic cavalry played a significant role in influencing subsequent Muslim tactics and weapons; the Turkic peoples, who were mostly Buddhists at the time of the Islamic conquest, later converted to Islam and came to be regarded as the foremost Muslim warriors, to the extent of replacing the Arabs as the dominant peoples in the Dar al-Islam (House of Islam).[48]

Visigoth

[edit]During the migration period, the Germanic Visigoths had traveled from their homeland north of the Danube to settle in the Roman province of Hispania, creating a kingdom upon the wreckage of the Western Roman Empire.[49] The Visigothic state in Iberia was based around forces raised by the nobility whom the king could call out in the event of war.[50] The king had his gardingi and fideles loyal to himself, while the nobility had their bucellarii.[50] The Visigoths favored cavalry with their favorite tactics being to repeatedly charge a foe combined with feigned retreats.[50]

The Muslim conquest of most of Iberia in less than a decade does suggest serious deficiencies with the Visigothic kingdom, though the limited sources make it difficult to discern the precise reasons for the collapse of the Visigoths.[50]

Frankish

[edit]Another Germanic people who founded a state upon the ruins of the Western Roman Empire were the Franks who settled in Gaul.[50] Like the Visigoths, the Frankish cavalry played a "significant part" in their wars.[50] The Frankish kings expected all of their male subjects to perform three months of military service every year, and all serving under the king's banner were paid a regular salary.[50] Those called up for service had to provide their own weapons and horses, which contributed to the "militarisation of Frankish society".[50] At least part of the reason for the victories of Charles Martel was he could call up a force of experienced warriors when faced with Muslim raids.[50]

Campaigns

[edit]Conquest of the Levant: 634–641

[edit]The province of Syria was the first to be wrested from Byzantine control. Arab-Muslim raids that followed the Ridda Wars prompted the Byzantines to send a major expedition into southern Palestine, which was defeated by the Arab forces under command of Khalid ibn al-Walid at the Battle of Ajnadayn in 634.[51] Ibn al-Walid had converted to Islam around 627, becoming one of Muhammad's most successful generals.[52] Ibn al-Walid had been fighting in Iraq against the Sasanians when he led his force on a trek across the deserts to Syria to attack the Byzantines from the rear.[53] In the Battle of the Mud fought at or near Pella (Fahl) and nearby Scythopolis (Beisan), both in the Jordan Valley, in December 634 or January 635, the Arabs scored another victory.[54] After a siege of six months the Arabs took Damascus, but Emperor Heraclius later retook it.[54] At the battle of Yarmuk (636), the Arabs were victorious, defeating Heraclius.[55] Ibn al-Walid appears to have been the "real military leader" at Yarmuk "under the nominal command of others".[53] Syria was ordered to be abandoned to the Muslims with Heraclius reportedly saying: "Peace be with you Syria; what a beautiful land you will be for your enemy".[55] On the heels of their victory, the Arab armies took Damascus again in 636, with Baalbek, Homs, and Hama to follow soon afterwards.[51] However, other fortified towns continued to resist despite the rout of the imperial army and had to be conquered individually.[51] Jerusalem fell in 638, Caesarea in 640, while others held out until 641.[51]

After a two-year siege, the garrison of Jerusalem surrendered rather than starve to death; under the terms of the surrender Caliph Umar promised to tolerate the Christians of Jerusalem and not to turn churches into mosques.[56] True to his word, Umar allowed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to remain, with the caliph praying on a prayer rug outside of the church.[56] The loss to the Muslims of Jerusalem, the holiest city to Christians, proved to be the source of much resentment in Christendom. The city of Caesarea Maritima continued to withstand the Muslim siege—as it could be supplied by sea—until it was taken by assault in 640.[56]

In the mountains of Asia Minor, the Muslims enjoyed less success, with the Byzantines adopting the tactic of "shadowing warfare" — refusing to give battle to the Muslims, while the people retreated into castles and fortified towns when the Muslims invaded; instead, Byzantine forces ambushed Muslim raiders as they returned to Syria carrying plunder and people they had enslaved.[57] In the frontier area where Anatolia met Syria, the Byzantine state evacuated the entire population and laid waste to the countryside, creating a no man's land where any invading army would find no food.[57] For decades afterwards, a guerrilla war was waged by Christians in the hilly countryside of north-western Syria supported by the Byzantines.[58] At the same time, the Byzantines began a policy of launching raids via sea on the coast of the caliphate with the aim of forcing the Muslims to keep at least some of their forces to defend their coastlines, thus limiting the number of troops available for an invasion of Anatolia.[58] Unlike Syria with its plains and deserts — which favored the offensive — the mountainous terrain of Anatolia favored the defensive, and for centuries afterwards the line between Christian and Muslim lands ran along the border between Anatolia and Syria.[57]

Conquest of Egypt: 639–642

[edit]

The Byzantine province of Egypt held strategic importance for its grain production, naval yards, and as a base for further conquests in Africa.[51] The Muslim general Amr ibn al-As began the conquest of the province on his own initiative in 639.[59] The majority of the Byzantine forces in Egypt were locally raised Coptic forces, intended to serve more as a police force; since the vast majority of Egyptians lived in the Nile River valley, surrounded on both the eastern and western sides by desert, Egypt was felt to be a relatively secure province.[60] In December 639, Amr entered the Sinai with a large force and took Pelusium, on the edge of the Nile River valley, and then defeated a Byzantine counter-attack at Bibays.[61] Contrary to expectations, the Arabs did not head for Alexandria, the capital of Egypt, but instead for a major fortress known as Babylon located at what is now Cairo.[60] Amr was planning to divide the Nile River valley in two.[61] The Arab forces won a major victory at the Battle of Heliopolis in 640, but they found it difficult to advance further because major cities in the Nile Delta were protected by water and because Amr lacked the machinery to break down city fortifications.[62]

The Arabs laid siege to Babylon, and its starving garrison surrendered on 9 April 641.[61] Nevertheless, the province was scarcely urbanized and the defenders lost hope of receiving reinforcements from Constantinople when the emperor Heraclius died in 641.[63] Afterwards, the Arabs turned north into the Nile Delta and laid siege to Alexandria.[61] The last major center to fall into Arab hands was Alexandria, which capitulated in September 642.[64] According to Hugh Kennedy, "Of all the early Muslim conquests, that of Egypt was the swiftest and most complete. [...] Seldom in history can so massive a political change have happened so swiftly and been so long lasting."[65] In 644, the Arabs suffered a major defeat by the Caspian Sea when an invading Muslim army was almost wiped out by the cavalry of the Khazar Khanate, and, seeing a chance to take back Egypt, the Byzantines launched an amphibious attack which took back Alexandria for a short period of time.[61] Though most of Egypt is desert, the Nile Delta has some of the most productive and fertile farmland in the entire world, which had made Egypt the "granary" of the Byzantine empire.[61] Control of Egypt meant that the caliphate could weather droughts without the fear of famine, laying the basis for the future prosperity of the caliphate.[61]

Arab–Byzantine naval warfare

[edit]

The Byzantine Empire had traditionally dominated the Mediterranean and the Black Sea with major naval bases at Constantinople, Acre, Alexandria and Carthage.[61] In 652, the Arabs won their first victory at sea off Alexandria, which was followed by the temporary Muslim conquest of Cyprus.[61] As Yemen had been a center of maritime trade, Yemeni sailors were brought to Alexandria to start building an Islamic fleet for the Mediterranean.[66]

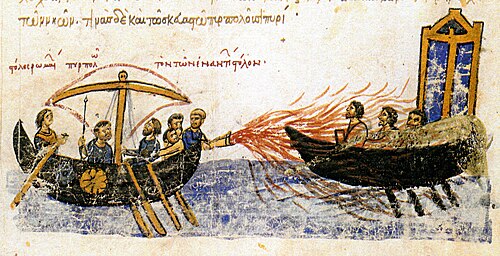

The Muslim fleet was based in Alexandria and used Acre, Tyre and Beirut as its forward bases.[66] The core of the fleet's sailors were Yemeni, but the shipwrights who built the ships were Iranian and Iraqi.[66] In the Battle of the Masts off Cape Chelidonia in Anatolia in 655, the Muslims defeated the Byzantine fleet in a series of boarding actions.[66] As a result, the Byzantines began a major expansion of their navy, which was matched by the Arabs, leading to a naval arms race.[66] From the early 8th century onward, the Muslim fleet would launch annual raids on the coastline on the Byzantine empire in Anatolia and Greece.[66]

As part of the arms race, both sides sought new technology to improve their warships. The Muslim warships had a larger forecastle, which was used to mount a stone-throwing engine.[66] The Byzantines invented Greek fire, an incendiary weapon that led the Muslims to cover their ships with water-soaked cotton.[67] A major problem for the Muslim fleet was the shortage of timber, which led the Muslims to seek qualitative instead of quantitative superiority by building bigger warships.[67] To save money, the Muslim shipwrights switched from the hull-first method of building ships to the frame-first method.[67]

Conquest of Mesopotamia and Persia: 633–651

[edit]

After an Arab incursion into Sasanian territories, the shah Yazdgerd III, who had just ascended the Persian throne, raised an army to resist the conquerors,[68] although many marzbans refused to help.[69] The Persians suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah in 636.[68] Little is known about the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah other than it lasted for several days by the banks of the river Euphrates in what is now Iraq and ended with the Persian force being annihilated.[70] Abolishing the Lakhmid Arab buffer state had forced the Persians to take over the desert defense themselves, leaving them overextended.[69]

As a result of al-Qadisiyyah, the Arab-Muslims gained control over the whole of Iraq, including Ctesiphon, the capital city of the Sassanids.[68] The Persians lacked sufficient forces to make use of the Zagros Mountains to stop the Arabs, having lost the prime of their army at al-Qadisiyyah.[70] The Persian forces withdrew over the Zagros, and the Arab army pursued them across the Iranian plateau, where the fate of the Sasanian Empire was sealed at the Battle of Nahavand in 642.[68] The crushing Muslim victory at Nahavand is known in the Muslim world as the "Victory of Victories".[69]

After Nahavand, the Persian state collapsed with Yezdegird III fleeing further east and various marzbans surrendering to the Arabs.[70] As the conquerors slowly covered the vast distances of Iran punctuated by hostile towns and fortresses, Yazdgerd III retreated, finally taking refuge in Khorasan, where he was assassinated by a local satrap in 651.[68] In the aftermath of their victory over the imperial army, the Muslims still had to contend with a collection of militarily weak but geographically inaccessible principalities of Persia.[51] It took decades to bring them all under control of the caliphate.[51] In what is now Afghanistan—a region where the authority of the shah was always disputed—the Muslims met fierce guerrilla resistance from the militant Buddhist tribes of the region.[71] Despite the complete Muslim triumph over Sasanid Iran as compared to the only partial defeat of the Byzantine Empire, the Muslims borrowed far more from the vanished Sassanian state than they ever did from the Byzantines.[72] However, for the Persians the defeat remained bitter. Some 400 years later, the Persian poet Ferdowsi lets Yazdgerd III speak in his popular poem Shahnameh (Book of Kings):

Damn this world, damn this time, damn this fate,

That uncivilized Arabs have come to

Make me a Muslim

Where are your valiant warriors and priests

Where are your hunting parties and your feats?

Where is that warlike mien and where are those

Great armies that destroyed our county's foes?

Count Iran as a ruin, as the lair

Of lions and leopards.

Look now and despair[73]

First Fitna: Fall of the Rashidun Caliphate

[edit]Right from the start of the caliphate, it was realized that there was a need to write down the sayings and story of Muhammad, which had been memorized by his followers before they all died.[74] Most people in Arabia were illiterate, and the Arabs had a strong culture of remembering history orally.[74] To preserve the story of Muhammad and to prevent any corruptions from entering the oral history, Abu Bakr had ordered scribes to write down the story of Muhammad as told to them by his followers, which was the origin of the Quran.[75] Disputes had emerged over which version of the Quran was the correct one and, by 644 different versions of the Quran were accepted in Damascus, Basra, Hims, and Kufa.[75] To settle the dispute, the Caliph Uthman had proclaimed the version of the Quran possessed by one of Muhammad's widows, Hafsa, to be the definitive and correct version, which offended some Muslims who held to the rival versions.[75] This, together with the favoritism shown by 'Uthman to his own clan, the Banu Umayya, in government appointments, led to a mutiny in Medina in 656 and 'Uthman's murder.[75]

Founding of the Umayyad Caliphate

[edit]Uthman's successor Ali was faced with a civil war, known to Muslims as the fitna, when the governor of Syria Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan revolted against him.[76] During this time, the first period of Muslim conquests stopped, as the armies of Islam turned against one another.[76] A group known as the Kharaji decided to end the civil war by assassinating the leaders of both sides.[76] However, the fitna ended in January 661 when Ali was killed by a kharaji assassin, allowing Mu'awiya to become caliph and found the Umayyad dynasty.[77] The fitna also marked the beginning of the split between Shia Muslims who supported Ali, and Sunni Muslims who opposed him.[76] Mu'awiya moved the capital of the caliphate from Medina to Damascus, which had a major effect on the politics and culture of the caliphate.[78] Mu'awiya followed the conquest of Iran by invading Central Asia and trying to finish off the Byzantine Empire by taking Constantinople.[79] In 670, a Muslim fleet seized Rhodes and then laid siege to Constantinople.[79] Nicolle wrote the siege of Constantinople from 670 to 677 was "more accurately" a blockade rather than a siege proper, which ended in failure as the "mighty" walls built by the Emperor Theodosius II in the 5th century proved their worth.[79]

The majority of the people in Syria remained Christian, and a substantial Jewish minority remained as well; both communities were to teach the Arabs much about science, trade and the arts.[79] The Umayyad caliphs are well-remembered for sponsoring a cultural "golden age" in Islamic history—for example, by building the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and for making Damascus into the capital of a "superpower" that stretched from Portugal to Central Asia, covering the vast territory from the Atlantic Ocean to the borders of China.[79]

Explanations for the Muslim armies' success

[edit]The rapidity of the early conquests has received various explanations.[80] Contemporary Christian writers conceived them as God's punishment visited on their fellow Christians for their sins.[81] Early Muslim historians viewed them as a reflection of the religious zeal of the conquerors and evidence of divine favor.[82] The theory that the conquests are explainable as an Arab migration triggered by economic pressures enjoyed popularity early in the 20th century but has largely fallen out of favor among historians, especially those who distinguish the migration from the conquests that preceded and enabled it.[83]

There are indications that the conquests started as initially disorganized pillaging raids launched partly by non-Muslim Arab tribes in the aftermath of the Ridda Wars and were soon extended into a war of conquest by the Rashidun caliphs,[84] although other scholars argue that the conquests were a planned military venture already underway during Muhammad's lifetime.[85] Fred Donner writes that the advent of Islam "revolutionized both the ideological bases and the political structures of the Arabian society, giving rise for the first time to a state capable of an expansionist movement."[86] According to Chase F. Robinson, it is likely that Muslim forces were often outnumbered, but unlike their opponents, they were fast, well coordinated and highly motivated.[87]

Another key reason was the weakness of the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, caused by the wars they had waged against each other in the preceding decades with alternating success.[88] It was aggravated by a plague that had struck densely populated areas and impeded conscription of new imperial troops, while the Arab armies could draw recruits from nomadic populations.[81] The Sasanian Empire, which had lost the latest round of hostilities with the Byzantines, was also affected by a crisis of confidence, and its elites suspected that the ruling dynasty had forfeited the favor of the gods.[81] The Arab military advantage was increased when Christianized Arab tribes who had served imperial armies as regular or auxiliary troops switched sides and joined the West Arabian coalition.[81] Arab commanders also made liberal use of agreements to spare lives and property of inhabitants in case of surrender and extended exemptions from paying tribute to groups who provided military services to the conquerors.[89] Additionally, the Byzantine persecution of Christians opposed to the Chalcedonian creed in Syria and Egypt alienated elements of those communities and made them more open to accommodation with the Arabs once it became clear that the latter would let them practice their faith undisturbed as long as they paid tribute.[90]

The conquests were further secured by the subsequent large-scale migration of Arabian peoples into the conquered lands.[91] Robert Hoyland argues that the failure of the Sasanian empire to recover was due in large part to the geographically and politically disconnected nature of Persia, which made coordinated action difficult once the established Sasanian rule collapsed.[92] Similarly, the difficult terrain of Anatolia made it difficult for the Byzantines to mount a large-scale attack to recover the lost lands, and their offensive action was largely limited to organizing guerrilla operations against the Arabs in the Levant.[92]

Conquest of Sindh: 711–714

[edit]Although there were sporadic incursions by Arab generals in the direction of India in the 660s and a small Arab garrison was established in the arid region of Makran in the 670s,[93] the first large-scale Arab campaign in the Indus valley occurred when the general Muhammad bin Qasim invaded Sindh in 711 after a coastal march through Makran.[94] Three years later the Arabs controlled all of the lower Indus valley.[94] Most of the towns seem to have submitted to Arab rule under peace treaties, although there was fierce resistance in other areas, including by the forces of Raja Dahir at the capital city Debal.[94][95] Arab incursions southward from Sindh were repulsed by the armies of Gurjara and Chalukya kingdoms, and further Islamic expansion was checked by the Rashtrakuta dynasty, which gained control of the region shortly after.[95]

Conquest of the Maghreb: 647–742

[edit]Arab forces began launching sporadic raiding expeditions into Cyrenaica (modern northeast Libya) and beyond soon after their conquest of Egypt.[96] Byzantine rule in northwest Africa at the time was largely confined to the coastal plains, while Berber kingdoms and tribes controlled the rest.[97] In 670 Arabs founded the settlement of Qayrawan, which gave them a forward base for further expansion.[97] Muslim historians credit the general Uqba ibn Nafi with subsequent conquest of lands extending to the Atlantic coast, although it appears to have been a temporary incursion.[97][98] The Berber king Kusayla and an enigmatic leader referred to as Kahina (prophetess or priestess) seem to have mounted effective, if short-lived resistance to Muslim rule at the end of the 7th century, but the sources do not give a clear picture of these events.[99] Arab forces were able to capture Carthage in 698 and Tangiers by 708.[99] After the fall of Tangiers, many Berbers joined the Muslim army.[98] In 740 Umayyad rule in the region was shaken by a major Berber revolt, which also involved Berber Kharijite Muslims.[100] After a series of defeats, the caliphate was finally able to crush the rebellion in 742, although local Berber dynasties continued to drift away from imperial control from that time on.[100]

Conquest of Hispania and Septimania: 711–721

[edit]

The Muslim conquest of Iberia is notable for the brevity and unreliability of the available sources.[101][102] After the Visigothic king of Spain Wittiza died in 710, the kingdom experienced a period of political division.[102] The Visigothic nobility was divided between the followers of Wittiza and his successor Roderic.[103] Akhila, Wittiza's son, had fled to Morocco after losing the succession struggle, and Muslim tradition states that he asked the Muslims to invade Spain.[103] Starting in the summer of 710, the Muslim forces in Morocco had launched several successful raids into Spain, which demonstrated the weakness of the Visigothic state.[104]

Taking advantage of the situation, the Muslim Berber commander, Tariq ibn Ziyad, who was stationed in Tangiers at the time, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar with an army of Arabs and Berbers in 711.[102] Most of the invasion force of 15,000 were Berbers, with the Arabs serving as an "elite" force.[104] Ziyad landed on the Rock of Gibraltar on 29 April 711.[71] After defeating Roderic at the river Guadalete on 19 July 711, Muslim forces advanced, capturing cities one after another.[101] The capital of Toledo surrendered peacefully.[104] Some of the cities surrendered with agreements to pay tribute and local aristocracy retained a measure of former influence.[102] The Spanish Jewish community welcomed the Muslims as liberators from the oppression of the Catholic Visigothic kings.[105]

In 712, another larger force of 18,000 from Morocco, led by Musa Ibn Nusayr, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to link up with Ziyad's force at Talavera.[105] The invasion seemed to have been on the initiative of Ziyad: the caliph, al-Walid, in Damascus reacted as if he was surprised to see him.[106] By 713 Iberia was almost entirely under Muslim control.[101] In 714, al-Walid summoned Ziyad to Damascus to explain his campaign in Spain, but Ziyad took his time travelling through North Africa and Palestine, and was finally imprisoned when he arrived in Damascus.[71] The events of the subsequent ten years, the details of which are obscure, included the capture of Barcelona and Narbonne, and a raid against Toulouse, followed by an expedition into Burgundy in 725.[101]

The last large-scale raid to the north ended with a Muslim defeat at the Battle of Tours at the hands of the Franks in 732.[101] The victory of the Franks, led by Charles Martel, over 'Abd al-Rahman Ibn 'Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi has often been misrepresented as the decisive battle that stopped the Muslim conquest of France, but the Umayyad force had been raiding Aquitaine with a particular interest in sacking churches and monasteries, not seeking its conquest.[107] The battle itself is a shadowy affair with the few sources describing it in poetic terms that are frustrating for the historian.[108] The battle occurred between 18 and 25 October 732 with the climax being an attack on the Muslim camp led by Martel that ended with al-Ghafiqi being killed and the Muslims withdrawing when night fell.[108] Martel's victory ended whatever plans there may have been to conquer France, but a series of Berber revolts in North Africa and in Spain against Arab rule may have played a greater role in ruling out conquests north of the Pyrenees.[108]

Conquest of Transoxiana: 673–751

[edit]

Transoxiana is the region northeast of Iran beyond the Amu Darya or Oxus River roughly corresponding with modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and parts of Kazakhstan. Initial incursions across the Oxus River were aimed at Bukhara (673) and Samarqand (675), and the results were limited to promises of tribute payments.[109] In 674, a Muslim force led by Ubaidullah Ibn Zayyad attacked Bukhara, the capital of Sogdia, which ended with the Sogdians agreeing to recognize the Umayadd caliph Mu'awiaya as their overlord and to pay tribute.[79]

In general, the campaigns in Central Asia were "hard fought" with the Buddhist Turkic peoples fiercely resisting efforts to incorporate them into the caliphate. China, which saw Central Asia as its own sphere of influence, particularly because of the economic importance of the Silk Road, supported the Turkic defenders.[79] Further advances were hindered for a quarter century by political upheavals within the Umayyad caliphate.[109] This was followed by a decade of rapid military progress under the leadership of the new governor of Khurasan, Qutayba ibn Muslim, which included the conquest of Bukhara and Samarqand in 706–712.[110] The expansion lost its momentum when Qutayba was killed during an army mutiny and the Arabs were placed on the defensive by an alliance of Sogdian and Türgesh forces with support from Tang China.[110] However, reinforcements from Syria helped turn the tide and most of the lost lands were reconquered by 741.[110] Muslim rule over Transoxania was consolidated in 751 when a Chinese-led army was defeated at the Battle of Talas.[111]

Expeditions into Afghanistan

[edit]Medieveal Islamic scholars divided the area of modern-day Afghanistan into two regions: the provinces of Khorasan and Sistan. Khorasan was the eastern satrapy of the Sasanian Empire, containing Balkh and Herat. Sistan included Ghazna, Zarang, Bost, Qandahar (also called al-Rukhkhaj or Zamindawar), Kabul, Kabulistan and Zabulistan.[112]

Before Muslim rule, the regions of Balkh (Bactria or Tokharistan), Herat and Sistan were under Sasanian rule. Further south in the Balkh region, in Bamiyan, indication of Sasanian authority diminishes, with a local dynasty apparently ruling from late antiquity, probably Hephthalites subject to the Yabghu of the Western Turkic Khaganate. While Herat was controlled by the Sasanians, its hinterlands were controlled by northern Hepthalites who continued to rule the Ghurid mountains and river valleys well into the Islamic era. Sistan was under Sasanian administration, but Qandahar remained out of Arab hands. Kabul and Zabulistan housed Indic religions, with the Zunbils and Kabul Shahis (for the most part) offering stiff resistance to Muslim rule for two centuries until the Saffarid and Ghaznavid conquests.[113] The Umayyad Caliphate regularly claimed nominal overlordship over the Zunbils and Kabul Shahis, and in 711 Qutayba ibn Muslim managed to force them to pay tribute.[114]

Other expeditions

[edit]Cyprus, Armenia, and Georgia

[edit]In 646 a Byzantine naval expedition was able to briefly recapture Alexandria.[115] The same year Mu'awiya, the governor of Syria and future founder of the Umayyad dynasty, ordered construction of a fleet.[115] Three years later it was put to use in a pillaging raid of Cyprus, followed by a raid in 650 that concluded with a treaty under which Cypriots surrendered many of their riches and slaves.[115] In 688 the island was made into a joint dominion of the caliphate and the Byzantine Empire under a pact which was to last for almost 300 years.[116]

In 639–640 Arab forces began to make advances into Armenia, which had been partitioned into a Byzantine province and a Sasanian province.[117] There is considerable disagreement among ancient and modern historians about events of the following years, and nominal control of the region may have passed several times between Arabs and Byzantines.[117] Although Muslim dominion was finally established by the time the Umayyads acceded to power in 661, it was not able to implant itself solidly in the country, and Armenia experienced a national and literary efflorescence over the next century.[117] As with Armenia, Arab advances into other lands of the Caucasus region, including Georgia, had as their end assurances of tribute payment and these principalities retained a large degree of autonomy.[118] This period also saw a series of clashes with the Khazar kingdom whose center of power was in the lower Volga steppes, and which vied with the caliphate over control of the Caucasus.[118]

Failed incursions into Byzantium and Afghanistan

[edit]

Other Muslim military ventures were met with outright failure. Despite a naval victory over the Byzantines in 654 at the Battle of the Masts, the subsequent attempt to besiege Constantinople was frustrated by a storm which damaged the Arab fleet.[119] Later sieges of Constantinople in 668–669 (674–678 according to other estimates) and 717–718 were thwarted with the help of the recently invented Greek fire.[120] In the east, although Arabs were able to establish control over most Sasanian-controlled areas of modern Afghanistan after the fall of Persia, the Kabul region resisted repeated attempts at invasion and would continue to do so until it was conquered by the Saffarids three centuries later.[121]

End of the conquests

[edit]By the time of the Abbasid Revolution in the middle of the 8th century, Muslim armies had come against a combination of natural barriers and powerful states that impeded any further military progress.[122] The wars produced diminishing returns in personal gains and fighters increasingly left the army for civilian occupations.[122] The priorities of the rulers also shifted from conquest of new lands to administration of the acquired empire.[122] Although the Abbasid era witnessed some new territorial gains, such as the conquests of Sicily, the period of rapid centralized expansion would now give way to an era when further spread of Islam would be slow and accomplished through the efforts of local dynasties, missionaries, and traders.[122]

Aftermath

[edit]

Significance

[edit]Nicolle writes that the series of Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries was "one of the most significant events in world history", leading to the creation of "a new civilisation", the Islamicised and Arabised Middle East.[123] Islam, which had previously been confined to Arabia, became a major world religion, while the synthesis of Arab, Byzantine, and Sasanian elements led to distinctive new styles of art and architecture emerging in the Middle East.[124] English historian Edward Gibbon writes in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

Under the last of the Umayyads, the Arabian empire extended two hundred days journey from east to west, from the confines of Tartary and India to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean ... We should vainly seek the indissoluble union and easy obedience that pervaded the government of Augustus and the Antonines; but the progress of Islam diffused over this ample space a general resemblance of manners and opinions. The language and laws of the Quran were studied with equal devotion at Samarcand and Seville: the Moor and the Indian embraced as countrymen and brothers in the pilgrimage of Mecca; and the Arabian language was adopted as the popular idiom in all the provinces to the westward of the Tigris.

Socio-political developments

[edit]The military victories of armies from the Arabian Peninsula heralded the expansion of Arab culture and religion. The conquests were followed by a large-scale migration of families and whole tribes from Arabia into the lands of the Middle East.[91] The conquering Arabs had already possessed a complex and sophisticated society.[91] Emigrants from Yemen brought with them agricultural, urban, and monarchical traditions; members of the Ghassanid and Lakhmid tribal confederations had experience collaborating with the empires.[91] The rank and file of the armies was drawn from both nomadic and sedentary tribes, while the leadership came mainly from the merchant class of the Hejaz.[91]

Two fundamental policies were implemented during the reign of the second caliph Umar (r. 634–644): the Bedouins would not be allowed to damage agricultural production of the conquered lands, and the leadership would cooperate with the local elites.[125] To that end, the Arab-Muslim armies were settled in segregated quarters or new garrison towns such as Basra, Kufa, and Fustat.[125] The latter two became the new administrative centers of Iraq and Egypt, respectively.[125] Soldiers were paid a stipend and prohibited from seizing lands.[125] Arab governors supervised collection and distribution of taxes but otherwise left the old religious and social order intact.[125] At first, many provinces retained a large degree of autonomy under the terms of agreements made with Arab commanders.[125]

As the time passed, the conquerors sought to increase their control over local affairs and make existing administrative machinery work for the new regime.[126] This involved several types of reorganization. In the Mediterranean region, city-states which traditionally governed themselves and their surrounding areas were replaced by a territorial bureaucracy separating town and rural administration.[127] In Egypt, fiscally independent estates and municipalities were abolished in favor of a simplified administrative system.[128] In the early 8th century, Syrian Arabs began to replace Coptic functionaries and communal levies gave way to individual taxation.[129] In Iran, the administrative reorganization and construction of protective walls prompted agglomeration of quarters and villages into large cities such as Isfahan, Qazvin, and Qum.[130] Local notables of Iran, who at first had almost complete autonomy, were incorporated into the central bureaucracy by the Abbasid period.[130] The similarity of Egyptian and Khurasanian official paperwork at the time of the caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) suggests a highly centralized empire-wide administration.[130]

New Arab settlements

[edit]

The society of new Arab settlements gradually became stratified into classes based on wealth and power.[131] It was also reorganized into new communal units that preserved clan and tribal names but were in fact only loosely based around old kinship bonds.[131] Arab settlers turned to civilian occupations and in eastern regions established themselves as a landed aristocracy.[131] At the same time, distinctions between the conquerors and local populations began to blur.[131] In Iran, the Arabs largely assimilated into local culture, adopting the Persian language and customs and marrying Persian women.[131] In Iraq, non-Arab settlers flocked to garrison towns.[131] Soldiers and administrators of the old regime came to seek their fortunes with the new masters, while slaves, laborers and peasants fled there seeking to escape the harsh conditions of life in the countryside.[131] Non-Arab converts to Islam were absorbed into the Arab-Muslim society through an adaptation of the tribal Arabian institution of clientage, in which protection of the powerful was exchanged for loyalty of the subordinates.[131] The clients (mawali) and their heirs were regarded as virtual members of the clan.[131] The clans became increasingly economically and socially stratified.[131] For example, while the noble clans of the Tamim tribe acquired Persian cavalry units as their mawali, other clans of the same tribe had slave laborers as theirs.[131] Slaves often became mawali of their former masters when they were freed.[131]

Contrary to the belief of earlier historians, there is no evidence of mass conversions to Islam in the immediate aftermath of the conquests.[132] The first groups to convert were Christian Arab tribes, although some of them retained their religion into the Abbasid era even while serving as troops of the caliphate.[132] They were followed by former elites of the Sasanian empire, whose conversion ratified their old privileges.[132] With time, the weakening of non-Muslim elites facilitated the breakdown of old communal ties and reinforced the incentives of conversion which promised economic advantages and social mobility.[132] By the beginning of the 8th century, conversions became a policy issue for the caliphate.[133] They were favored by religious activists, and many Arabs accepted the equality of Arabs and non-Arabs.[133] However, conversion was associated with economic and political advantages, and Muslim elites were reluctant to see their privileges diluted.[133] Public policy towards converts varied depending on the region and was changed by successive Umayyad caliphs.[133] These circumstances provoked opposition from non-Arab converts, whose ranks included many active soldiers, and helped set the stage for the civil war which ended with the fall of the Umayyad dynasty.[134]

Taxation policies and conversions to Islam

[edit]The Arab-Muslim conquests followed a general pattern of nomadic conquests of settled regions, whereby the conquering peoples became the new military elite and reached a compromise with the old elites by allowing them to retain local political, religious, and financial authority.[126] Peasants, workers, and merchants paid taxes, while members of the old and new elites collected them.[126] Payment of taxes, which for peasants often reached half of the value of their produce, was an economic burden as well as a mark of social inferiority.[126] Scholars differ in their assessment of relative tax burdens before and after the conquests. John Esposito states that in effect this meant lower taxes.[135] According to Bernard Lewis, available evidence suggests that the change from Byzantine to Arab rule was "welcomed by many among the subject peoples, who found the new yoke far lighter than the old, both in taxation and in other matters".[136] In contrast, Norman Stillman writes that although the tax burden of the Jews under early Islamic rule was comparable to that under previous rulers, Christians of the Byzantine Empire (though not Christians of the Persian empire, whose status was similar to that of the Jews) and Zoroastrians of Iran shouldered a considerably heavier burden in the immediate aftermath of the conquests.[137]

In the wake of the early conquests taxes could be levied on individuals, on the land, or as collective tribute.[138] During the first century of Islamic expansion, the words jizya and kharaj were used in all three senses, with context distinguishing between individual and land taxes.[139] Regional variations in taxation at first reflected the diversity of previous systems.[140] The Sasanian Empire had a general tax on land and a poll tax having several rates based on wealth, with an exemption for aristocracy.[140] This poll tax was adapted by Arab rulers, so that the aristocracy exemption was assumed by the new Arab-Muslim elite and shared by local aristocracy who converted to Islam.[141] The nature of Byzantine taxation remains partly unclear, but it appears to have been levied as a collective tribute on population centers and this practice was generally followed under the Arab rule in former Byzantine provinces.[140] Collection of taxes was delegated to autonomous local communities on the condition that the burden be divided among its members in the most equitable manner.[140] In most of Iran and Central Asia local rulers paid a fixed tribute and maintained their autonomy in tax collection.[140]

Tax evasion and reforms

[edit]Difficulties in tax collection soon appeared.[140] Egyptian Copts, who had been skilled in tax evasion since Roman times, were able to avoid paying the taxes by entering monasteries, which were initially exempt from taxation, or simply by leaving the district where they were registered.[140] This prompted imposition of taxes on monks and introduction of movement controls.[140] In Iraq, many peasants who had fallen behind with their tax payments converted to Islam and abandoned their land for Arab garrison towns in hope of escaping taxation.[142] Faced with a decline in agriculture and a treasury shortfall, the governor of Iraq, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, forced peasant converts to return to their lands and subjected them to the taxes again, effectively forbidding them from converting to Islam.[143] In Khorasan, a similar phenomenon forced the native aristocracy to compensate for the shortfall in tax collection out of their own pockets, and they responded by persecuting peasant converts and imposing heavier taxes on poor Muslims.[143]

The situation where conversion to Islam was penalized in an Islamic state could not last, and the Umayyad caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (r. 717–720) has been credited with changing the taxation system.[143] Modern historians doubt this account, although details of the transition to the system of taxation elaborated by Abbasid-era jurists are unclear.[143] Umar II ordered governors to cease collection of taxes from Muslim converts, but his successors obstructed this policy and some governors sought to stem the tide of conversions by introducing additional requirements such as circumcision and the ability to recite passages from the Quran.[144] Taxation-related grievances of non-Arab Muslims contributed to the opposition movements which resulted in the Abbasid Revolution.[145] Under the new system that was eventually established, kharaj came to be regarded as a tax levied on the land, regardless of the taxpayer's religion.[143] The poll-tax was no longer levied on Muslims, but the treasury did not necessarily suffer and converts did not gain as a result, since they had to pay zakat, which was probably instituted as a compulsory tax on Muslims around 730.[146] The terminology became specialized during the Abbasid era, so that kharaj no longer meant anything more than land tax, while the term jizya was restricted to the poll-tax on dhimmis.[143]

The influence of jizya on conversion has been a subject of scholarly debate.[147] Julius Wellhausen holds that the poll tax amounted to so little that exemption from it did not constitute sufficient economic motive for conversion.[148] Similarly, Thomas Arnold states that jizya was "too moderate" to constitute a burden, "seeing that it released them from the compulsory military service that was incumbent on their Muslim fellow subjects." He further adds that converts escaping taxation would have to pay the legal alms, zakat, that is annually levied on most kinds of movable and immovable property.[149] Other early 20th century scholars suggest that non-Muslims converted to Islam en masse in order to escape the poll tax, but this theory has been challenged by more recent research.[147] Daniel Dennett has shown that other factors, such as desire to retain social status, had greater influence on this choice in the early Islamic period.[147]

Sharia and non-Muslims

[edit]The Arab conquerors did not repeat the mistakes which had been made by the governments of the Byzantine and Sasanian empires, which had tried and failed to impose an official religion on subject populations, which had caused resentments that made the Muslim conquests more acceptable to them.[150] Instead, the rulers of the new empire generally respected the traditional middle-Eastern pattern of religious pluralism, which was not one of equality but rather of dominance by one group over the others.[150] After the end of military operations, which involved sacking of some monasteries and confiscation of Zoroastrian fire temples in Syria and Iraq, the early caliphate was characterized by religious tolerance and peoples of all ethnicities and religions blended in public life.[151] Before Muslims were ready to build mosques in Syria, they accepted Christian churches as holy places and shared them with local Christians.[132] In Iraq and Egypt, Muslim authorities cooperated with Christian religious leaders.[132] Numerous churches were repaired and new ones built during the Umayyad era.[152]

The first Umayyad caliph Muawiyah made deliberate efforts to convince those whom he had conquered that he was not opposed to their religion, and tried to enlist support from Christian Arab elites.[153] There is no evidence for public display of Islam by the state before the reign of Abd al-Malik (685–705), when Quranic verses and references to Muhammad suddenly became prominent on coins and official documents.[154] This change was motivated by a desire to unify the Muslim community after the second civil war and rally them against their chief common enemy, the Byzantine Empire.[154]

A further change of policy occurred during the reign of Umar II (717–720).[155] The disastrous failure of the siege of Constantinople in 718 which was accompanied by massive Arab casualties led to a spike of popular animosity among Muslims toward Byzantium and Christians in general.[155] At the same time, many Arab soldiers left the army for civilian occupations and they wished to emphasize their high social status among the conquered peoples.[155] These events prompted introduction of restrictions on non-Muslims, which, according to Hoyland, were modeled both on Byzantine curbs on Jews, starting with the Theodosian Code and later codes, which contained prohibitions against building new synagogues and giving testimony against Christians, and on Sassanid regulations that prescribed distinctive attire for different social classes.[155]

In the following decades Islamic jurists elaborated a legal framework in which other religions would have a protected but subordinate status.[154] Islamic law followed the Byzantine precedent of classifying subjects of the state according to their religion, in contrast to the Sasanian model which put more weight on social than on religious distinctions.[155] In theory, like the Byzantine empire, the caliphate placed severe restrictions on paganism, but in practice most non-Abrahamic communities of the former Sasanian territories were classified as possessors of a scripture (ahl al-kitab) and granted protected (dhimmi) status.[155]

Jews and Christians

[edit]In Islam, Christians and Jews are seen as "People of the Book" as the Muslims accept both Jesus Christ and the Jewish prophets as their own prophets, which accorded them a respect that was not reserved to the "heathen" peoples of Iran, Central Asia and India.[156] In places like the Levant and Egypt, both Christians and Jews were allowed to maintain their churches and synagogues and keep their own religious organizations in exchange for paying the jizya tax.[156] At times, the caliphs engaged in triumphalist gestures, like building the famous Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem from 690 to 692 on the site of the Jewish Second Temple, which had been destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD—though the use of Roman and Sassanian symbols of power in the mosque suggests its purpose was partly to celebrate the Arab victories over the two empires.[157]

Those Christians out of favor with the prevailing orthodoxy in the Roman Empire often preferred to live under Muslim rule as it meant the end of persecution.[158] As both the Jewish and Christian communities of the Levant and North Africa were better educated than their conquerors, they were often employed as civil servants in the early years of the caliphate.[79] However, a reported saying of Muhammad that "Two religions may not dwell together in Arabia" led to different policies being pursued in Arabia with conversion to Islam being imposed rather than merely encouraged.[158] With the notable exception of Yemen, where a large Jewish community existed right up until the middle of the 20th century, all of the Christian and Jewish communities in Arabia "completely disappeared".[158] The Jewish community of Yemen seems to have survived as Yemen was not regarded as part of Arabia proper in the same way that the Hejaz and the Nejd were.[158]

Mark R. Cohen writes that the jizya paid by Jews under Islamic rule provided a "surer guarantee of protection from non-Jewish hostility" than that possessed by Jews in the Latin West, where Jews "paid numerous and often unreasonably high and arbitrary taxes" in return for official protection, and where treatment of Jews was governed by charters which new rulers could alter at will upon accession or refuse to renew altogether.[159] The Pact of Umar, which stipulated that Muslims must "do battle to guard" the dhimmis and "put no burden on them greater than they can bear", was not always upheld, but it remained "a steadfast cornerstone of Islamic policy" into early modern times.[159]

Some Persians, now known as Parsees, fled to India to continue to follow the pre-Islamic traditions and religion of their homeland.[68]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Nile Green (12 December 2016). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780520294134.

- ^ M. A. Sabhan (8 March 1979). The 'Abbāsid Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780521295345.

- ^ Kaegi (1995), Donner (2014)

- ^ Hoyland (2014), Kennedy (2007)

- ^ Buchan, James (21 July 2007). "Children of empire". The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihad State, the Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd-al Malik and the collapse of the Umayyads. State University of New York Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- ^ Gardner, Hall; Kobtzeff, Oleg, eds. (2012). The Ashgate Research Companion to War: Origins and Prevention. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 208–209.

- ^ Rosenwein, Barbara H. (2004). A Short History of the Middle Ages. Ontario: Broadview Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-55111-290-9.

- ^ Jandora, John W. (1985). "The battle of the Yarmūk: A reconstruction". Journal of Asian History. 19 (1): 8–21. JSTOR 41930557.

- ^ Grant, Reg G. (2011). "Yarmuk". 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of World History. Universe Pub. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7893-2233-3.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 15.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d e f Nicolle (2009), p. 18.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 19.

- ^ Donner (2010), p. 45.

- ^ Armstrong (2002), p. 36.

- ^ Hawting (2000), p. 22.

- ^ Donner (2010), p. 48.

- ^ Donner (2010), p. 44.

- ^ Armstrong (2002), p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Nicolle (2009), p. 22.

- ^ Donner (2010), p. 52.

- ^ Theophanes, Chronicle, 317–327

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 217–227; Haldon (1997), 46; Baynes (1912), passim; Speck (1984), 178 - ^ a b Nicolle 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Foss, Clive (1975). "The Persians in Asia Minor and the end of antiquity". The English Historical Review. 90 (357): 721–747. doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721. JSTOR 567292.

- ^ Howard-Johnston, James (2006). East Rome, Sasanian Persia And the End of Antiquity: Historiographical And Historical Studies. Ashgate Publishing. p. xv. ISBN 978-0-86078-992-5.

- ^ Liska, George (1998). "Projection contra prediction: Alternative futures and options". Expanding Realism: The Historical Dimension of World Politics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8476-8680-3.

- ^ Kaegi (1995), p. 66

- ^ Nicolle (1994), p. 14

- ^ a b Hoyland 1997, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 26.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 28.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 30.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 33.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 37.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 38.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 41.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 43.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 44.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 45.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Nicolle (2009), pp. 46.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nicolle (2009), p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lapidus (2014), p. 49

- ^ Nicolle 2009, pp. 63.

- ^ a b Nicolle 2009, pp. 64.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 50.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 51.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 54.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 52.

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 52

- ^ Hoyland (2014), p. 70; in 641 according to Lapidus (2014), p. 49

- ^ a b Nicolle 2009, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nicolle 2009, p. 56.

- ^ Hoyland (2014), pp. 70–72

- ^ Hoyland (2014), pp. 73–75, Lapidus (2014), p. 49

- ^ Hoyland (2014), pp. 73–75; in 643 according to Lapidus (2014), p. 49

- ^ Kennedy (2007), p. 165

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicolle 2009, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 2009, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f Vaglieri (1977), pp. 60–61

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 58

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 59

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 66

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 60

- ^ Pagden (2008), p. 145–146

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 60-61

- ^ a b c d Nicolle (2009), p. 61

- ^ a b c d Nicolle (2009), p. 62

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 629

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 66-68

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nicolle (2009), p. 68

- ^ Donner (2014), pp. 3–7

- ^ a b c d Hoyland (2014), pp. 93–95

- ^ Donner (2014), p. 3, Hoyland (2014), p. 93

- ^ Donner (2014), p. 5, Hoyland (2014), p. 62

- ^ "The immediate outcome of the Muslim victories [in the Ridda Wars] was turmoil. Medina's victories led allied tribes to attack the non-aligned to compensate for their own losses. The pressure drove tribes [...] across the imperial frontiers. The Bakr tribe, which had defeated a Persian detachment in 606, joined forces with the Muslims and led them on a raid in southern Iraq [...] A similar spilling over of tribal raiding occurred on the Syrian frontiers. Abu Bakr encouraged these movements [...] What began as inter-tribal skirmishing to consolidate a political confederation in Arabia ended as a full-scale war against the two empires." Lapidus (2014), p. 48 See also Donner (2014), pp. 5–7

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 48, Hoyland (2014), p. 38

- ^ Donner (2014), p. 8

- ^ Robinson, Chase F. (2010). "The rise of Islam, 600 705". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge University Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780521838238.

it is probably safe to assume that Muslims were often outnumbered. Unlike their adversaries, however, Muslim armies were fast, agile, well coordinated and highly motivated.

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 50, Hoyland (2014), p. 93

- ^ Hoyland (2014), p. 97

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 50, Hoyland (2014), p. 97

- ^ a b c d e Lapidus (2014), p. 50

- ^ a b Hoyland (2014), p. 127

- ^ Hoyland (2014), p. 190

- ^ a b c T.W. Haig, C.E. Bosworth. Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Sind", vol. 9, p. 632

- ^ a b Hoyland (2014), pp. 192–194

- ^ Hoyland (2014), p. 78

- ^ a b c Hoyland (2014), pp. 124–126

- ^ a b G. Yver. Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Maghreb", vol. 5, p. 1189.

- ^ a b Hoyland (2014), pp. 142–145

- ^ a b Hoyland (2014), p. 180

- ^ a b c d e Évariste Lévi-Provençal. Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Al-Andalus", vol. 1, p. 492

- ^ a b c d Hoyland (2014), pp. 146–147

- ^ a b Nicolle 2009, pp. 65.

- ^ a b c Nicolle (2009), p. 71

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 65

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 71-72

- ^ Nicolle 2009, p. 72-73.

- ^ a b c Nicolle 2009, p. 75.

- ^ a b Daniel (2010), p. 456

- ^ a b c Daniel (2010), p. 457

- ^ Daniel (2010), p. 458

- ^ Nile Green (12 December 2016). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. Cambridge University Press. pp. 43, 44. ISBN 9780520294134.

- ^ Nile Green (12 December 2016). Afghanistan's Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44, 46–47. ISBN 9780520294134.

- ^ Lee, Jonathan L.; Sims Williams, Nicholas (2003). "Bactrian Inscription from Yakawlang sheds new light on history of Buddhism in Afghanistan". Silk Road Art and Archaeology. 9: 167.

- ^ a b c Hoyland (2014), pp. 90–93

- ^ "Cyprus — Government and society". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c M. Canard. Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Arminiya", vol. 1, pp. 636–637

- ^ a b C.E. Bosworth. Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Al-Qabq", vol. 4, pp. 343–344

- ^ Hoyland (2014), pp. 106–108

- ^ Hoyland (2014), pp. 108–109, 175–177

- ^ M. Longworth Dames. Encyclopedia of Islam 2nd ed, Brill. "Afghanistan", vol. 1, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d Hoyland (2014), p. 207

- ^ Nicolle 2009, pp. 91.

- ^ Nicolle 2009, pp. 80–84.

- ^ a b c d e f Lapidus (2014), p. 52

- ^ a b c d Lapidus (2014), p. 53

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 56

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 57

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 79

- ^ a b c Lapidus (2014), p. 58

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lapidus (2014), pp. 58–60

- ^ a b c d e f Lapidus (2014), pp. 60–61

- ^ a b c d Lapidus (2014), pp. 61–62

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 71

- ^ Esposito (1998), p. 34. "They replaced the conquered countries, indigenous rulers and armies, but preserved much of their government, bureaucracy, and culture. For many in the conquered territories, it was no more than an exchange of masters, one that brought peace to peoples demoralized and disaffected by the casualties and heavy taxation that resulted from the years of Byzantine-Persian warfare. Local communities were free to continue to follow their own way of life in internal, domestic affairs. In many ways, local populations found Muslim rule more flexible and tolerant than that of Byzantium and Persia. Religious communities were free to practice their faith to worship and be governed by their religious leaders and laws in such areas as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In exchange, they were required to pay tribute, a poll tax (jizya) that entitled them to Muslim protection from outside aggression and exempted them from military service. Thus, they were called the "protected ones" (dhimmi). In effect, this often meant lower taxes, greater local autonomy, rule by fellow Semites with closer linguistic and cultural ties than the hellenized, Greco-Roman élites of Byzantium, and greater religious freedom for Jews and indigenous Christians."

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (2002). Arabs in History. OUP Oxford. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-19280-31-08.

- ^ Stillman (1979), p. 28

- ^ Cahen (1965), p. 559

- ^ Cahen (1965), p. 560; Anver M. Emon, Religious Pluralism and Islamic Law: Dhimmis and Others in the Empire of Law, p. 98, note 3. Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199661633. Quote: "Some studies question the nearly synonymous use of the terms kharaj and jizya in the historical sources. The general view suggests that while the terms kharaj and jizya seem to have been used interchangeably in early historical sources, what they referred to in any given case depended on the linguistic context. If one finds references to "a kharaj on their heads," the reference was to a poll tax, despite the use of the term kharaj, which later became the term of art for land tax. Likewise, if one fins the phrase "jizya on their land," this referred to a land tax, despite the use of jizya which later come to refer to the poll tax. Early history therefore shows that although each term did not have a determinate technical meaning at first, the concepts of poll tax and land tax existed early in Islamic history." Denner, Conversion and the Poll Tax, 3–10; Ajiaz Hassan Qureshi, "The Terms Kharaj and Jizya and Their Implication," Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society 12 (1961): 27–38; Hossein Modarressi Rabatab'i, Kharaj in Islamic Law (London: Anchor Press Ltd, 1983).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cahen (1965), p. 560

- ^ Cahen (1965), p. 560; Hoyland (2014), p. 99

- ^ Cahen (1965), p. 560; Hoyland (2014), p. 199

- ^ a b c d e f Cahen (1965), p. 561

- ^ Hoyland (2014), p. 199

- ^ Hoyland (2014), pp. 201–202

- ^ Cahen (1965), p. 561; Hoyland (2014), p. 200

- ^ a b c Tramontana, Felicita (2013). "The Poll Tax and the Decline of the Christian Presence in the Palestinian Countryside in the 17th Century". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 56 (4–5): 631–652. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341337.

The (cor)relation between the payment of the poll-tax and conversion to Islam, has long been the subject of scholarly debate. At the beginning of the twentieth century scholars suggested that after the Muslim conquest the local populations converted en masse to evade the payment of the poll tax. This assumption has been challenged by subsequent research. Indeed Dennett's study clearly showed that the payment of the poll tax was not a sufficient reason to convert after the Muslim conquest and that other factors—such as the wish to retain social status—had greater influence. According to Inalcik the wish to evade payment of the jizya was an important incentive for conversion to Islam in the Balkans, but Anton Minkov has recently argued that taxation was only one of a number of motivations.

- ^ Dennett (1950), p. 10. "Wellhausen makes the assumption that the poll tax amounted to so little that exemption from it did not constitute sufficient economic motive for conversion."

- ^ Walker Arnold, Thomas (1913). Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith. Constable & Robinson Ltd. pp. 59.

... but this jizyah was too moderate to constitute a burden, seeing that it released them from the compulsory military service that was incumbent on their Muslim fellow-subjects. Conversion to Islam was certainly attended by a certain pecuniary advantage, but his former religion could have had but little hold on a convert who abandoned it merely to gain exemption from the jizyah; and now, instead of jizyah, the convert had to pay the legal alms, zakāt, annually levied on most kinds of movable and immovable property.

(online) - ^ a b Lewis, Bernard (2014). The Jews of Islam. Princeton University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781400820290.

- ^ Lapidus (2014), pp. 61, 153

- ^ Lapidus (2014), p. 156

- ^ Hoyland (2014), p. 130

- ^ a b c Hoyland (2014), p. 195

- ^ a b c d e f Hoyland (2014), pp. 196–198

- ^ a b Nicolle (2009), p. 84

- ^ Nicolle (2009), p. 81-82

- ^ a b c d Nicolle (2009), p. 85

- ^ a b Cohen (2008), pp. 72–73

General and cited sources

[edit]- Cahen, Claude (1965). Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469475.

- Cohen, Mark (2008). Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13931-9.