Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Magnet

View on Wikipedia

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

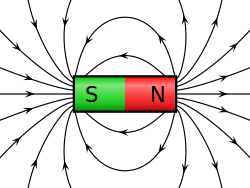

A magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field is invisible but is responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, such as iron, steel, nickel, cobalt, etc. and attracts or repels other magnets.

A permanent magnet is an object made from a material that is magnetized and creates its own persistent magnetic field. An everyday example is a refrigerator magnet used to hold notes on a refrigerator door. Materials that can be magnetized, which are also the ones that are strongly attracted to a magnet, are called ferromagnetic (or ferrimagnetic). These include the elements iron, nickel and cobalt and their alloys, some alloys of rare-earth metals, and some naturally occurring minerals such as lodestone. Although ferromagnetic (and ferrimagnetic) materials are the only ones attracted to a magnet strongly enough to be commonly considered magnetic, all other substances respond weakly to a magnetic field, by one of several other types of magnetism.

Ferromagnetic materials can be divided into magnetically "soft" materials like annealed iron, which can be magnetized but do not tend to stay magnetized, and magnetically "hard" materials, which do. Permanent magnets are made from "hard" ferromagnetic materials such as alnico and ferrite that are subjected to special processing in a strong magnetic field during manufacture to align their internal microcrystalline structure, making them very hard to demagnetize. To demagnetize a saturated magnet, a certain magnetic field must be applied, and this threshold depends on coercivity of the respective material. "Hard" materials have high coercivity, whereas "soft" materials have low coercivity. The overall strength of a magnet is measured by its magnetic moment or, alternatively, the total magnetic flux it produces. The local strength of magnetism in a material is measured by its magnetization.

An electromagnet is made from a coil of wire that acts as a magnet when an electric current passes through it but stops being a magnet when the current stops. Often, the coil is wrapped around a core of "soft" ferromagnetic material such as mild steel, which greatly enhances the magnetic field produced by the coil.

Discovery and development

[edit]Ancient people learned about magnetism from lodestones (or magnetite) which are naturally magnetized pieces of iron ore. The word magnet was adopted in Middle English from Latin magnetum "lodestone", ultimately from Greek μαγνῆτις [λίθος] (magnētis [lithos])[1] meaning "[stone] from Magnesia",[2] a place in Anatolia where lodestones were found (today Manisa in modern-day Turkey). Lodestones, suspended so they could turn, were the first magnetic compasses. The earliest known surviving descriptions of magnets and their properties are from Anatolia, India, and China around 2,500 years ago.[3][4][5] The properties of lodestones and their affinity for iron were written of by Pliny the Elder in his encyclopedia Naturalis Historia in the 1st century AD.[6]

In 11th century China, it was discovered that quenching red hot iron in the Earth's magnetic field would leave the iron permanently magnetized. This led to the development of the navigational compass, as described in Dream Pool Essays in 1088.[7][8] By the 12th to 13th centuries AD, magnetic compasses were used in navigation in China, Europe, the Arabian Peninsula and elsewhere.[9]

A straight iron magnet tends to demagnetize itself by its own magnetic field. To overcome this, the horseshoe magnet was invented by Daniel Bernoulli in 1743.[7][10] A horseshoe magnet avoids demagnetization by returning the magnetic field lines to the opposite pole.[11]

In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that a compass needle is deflected by a nearby electric current. In the same year André-Marie Ampère showed that iron can be magnetized by inserting it in an electrically fed solenoid.[12] This led William Sturgeon to develop an iron-cored electromagnet in 1824.[7] Joseph Henry further developed the electromagnet into a commercial product in 1830–1831, giving people access to strong magnetic fields for the first time. In 1831 he built an ore separator with an electromagnet capable of lifting 750 pounds (340 kg).[13]

Physics

[edit]Magnetic field

[edit]

The magnetic flux density (also called magnetic B field or just magnetic field, usually denoted by B) is a vector field. The magnetic B field vector at a given point in space is specified by two properties:

- Its direction, which is along the orientation of a compass needle.

- Its magnitude (also called strength), which is proportional to how strongly the compass needle orients along that direction.

In SI units, the strength of the magnetic B field is given in teslas.[14]

Magnetic moment

[edit]A magnet's magnetic moment (also called magnetic dipole moment and usually denoted μ) is a vector that characterizes the magnet's overall magnetic properties. For a bar magnet, the direction of the magnetic moment points from the magnet's south pole to its north pole,[15] and the magnitude relates to how strong and how far apart these poles are. In SI units, the magnetic moment is specified in terms of A·m2 (amperes times meters squared).

A magnet both produces its own magnetic field and responds to magnetic fields. The strength of the magnetic field it produces is at any given point proportional to the magnitude of its magnetic moment. In addition, when the magnet is put into an external magnetic field, produced by a different source, it is subject to a torque tending to orient the magnetic moment parallel to the field.[16] The amount of this torque is proportional both to the magnetic moment and the external field. A magnet may also be subject to a force driving it in one direction or another, according to the positions and orientations of the magnet and source. If the field is uniform in space, the magnet is subject to no net force, although it is subject to a torque.[17]

A wire in the shape of a circle with area A and carrying current I has a magnetic moment of magnitude equal to IA.

Magnetization

[edit]The magnetization of a magnetized material is the local value of its magnetic moment per unit volume, usually denoted M, with units A/m.[18] It is a vector field, rather than just a vector (like the magnetic moment), because different areas in a magnet can be magnetized with different directions and strengths (for example, because of domains, see below). A good bar magnet may have a magnetic moment of magnitude 0.1 A·m2 and a volume of 1 cm3, or 1×10−6 m3, and therefore an average magnetization magnitude is 100,000 A/m. Iron can have a magnetization of around a million amperes per meter. Such a large value explains why iron magnets are so effective at producing magnetic fields.

Modelling magnets

[edit]

Two different models exist for magnets: magnetic poles and atomic currents.

Although for many purposes it is convenient to think of a magnet as having distinct north and south magnetic poles, the concept of poles should not be taken literally: it is merely a way of referring to the two different ends of a magnet. The magnet does not have distinct north or south particles on opposing sides. If a bar magnet is broken into two pieces, in an attempt to separate the north and south poles, the result will be two bar magnets, each of which has both a north and south pole. However, a version of the magnetic-pole approach is used by professional magneticians to design permanent magnets.[citation needed]

In this approach, the divergence of the magnetization ∇·M inside a magnet is treated as a distribution of magnetic monopoles. This is a mathematical convenience and does not imply that there are actually monopoles in the magnet. If the magnetic-pole distribution is known, then the pole model gives the magnetic field H. Outside the magnet, the field B is proportional to H, while inside the magnetization must be added to H. An extension of this method that allows for internal magnetic charges is used in theories of ferromagnetism.

Another model is the Ampère model, where all magnetization is due to the effect of microscopic, or atomic, circular bound currents, also called Ampèrian currents, throughout the material. For a uniformly magnetized cylindrical bar magnet, the net effect of the microscopic bound currents is to make the magnet behave as if there is a macroscopic sheet of electric current flowing around the surface, with local flow direction normal to the cylinder axis.[19] Microscopic currents in atoms inside the material are generally canceled by currents in neighboring atoms, so only the surface makes a net contribution; shaving off the outer layer of a magnet will not destroy its magnetic field, but will leave a new surface of uncancelled currents from the circular currents throughout the material.[20] The right-hand rule tells which direction positively-charged current flows. However, current due to negatively-charged electricity is far more prevalent in practice.[citation needed][21]

Polarity

[edit]The north pole of a magnet is defined as the pole that, when the magnet is freely suspended, points towards the Earth's North Magnetic Pole in the Arctic (the magnetic and geographic poles do not coincide, see magnetic declination). Since opposite poles (north and south) attract, the North Magnetic Pole is actually the south pole of the Earth's magnetic field.[22][23][24][25] As a practical matter, to tell which pole of a magnet is north and which is south, it is not necessary to use the Earth's magnetic field at all. For example, one method would be to compare it to an electromagnet, whose poles can be identified by the right-hand rule. The magnetic field lines of a magnet are considered by convention to emerge from the magnet's north pole and reenter at the south pole.[25]

Magnetic materials

[edit]The term magnet is typically reserved for objects that produce their own persistent magnetic field even in the absence of an applied magnetic field. Only certain classes of materials can do this. Most materials, however, produce a magnetic field in response to an applied magnetic field – a phenomenon known as magnetism. There are several types of magnetism, and all materials exhibit at least one of them.

The overall magnetic behavior of a material can vary widely, depending on the structure of the material, particularly on its electron configuration. Several forms of magnetic behavior have been observed in different materials, including:

- Ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials are the ones normally thought of as magnetic; they are attracted to a magnet strongly enough that the attraction can be felt. These materials are the only ones that can retain magnetization and become magnets; a common example is a traditional refrigerator magnet. Ferrimagnetic materials, which include ferrites and the longest used and naturally occurring magnetic materials magnetite and lodestone, are similar to but weaker than ferromagnetics. The difference between ferro- and ferrimagnetic materials is related to their microscopic structure, as explained in Magnetism.

- Paramagnetic substances, such as platinum, aluminum, and oxygen, are weakly attracted to either pole of a magnet. This attraction is hundreds of thousands of times weaker than that of ferromagnetic materials, so it can only be detected by using sensitive instruments or using extremely strong magnets. Magnetic ferrofluids, although they are made of tiny ferromagnetic particles suspended in liquid, are sometimes considered paramagnetic since they cannot be magnetized.

- Diamagnetic means repelled by both poles. Compared to paramagnetic and ferromagnetic substances, diamagnetic substances, such as carbon, copper, water, and plastic, are even more weakly repelled by a magnet. The permeability of diamagnetic materials is less than the permeability of a vacuum. All substances not possessing one of the other types of magnetism are diamagnetic; this includes most substances. Although force on a diamagnetic object from an ordinary magnet is far too weak to be felt, using extremely strong superconducting magnets, diamagnetic objects such as pieces of lead and even mice[26] can be levitated, so they float in mid-air. Superconductors repel magnetic fields from their interior and are strongly diamagnetic.

There are various other types of magnetism, such as spin glass, superparamagnetism, superdiamagnetism, and metamagnetism.

Shape

[edit]The shape of a permanent magnet has a large influence on its magnetic properties. When a magnet is magnetized, a demagnetizing field will be created inside it. As the name suggests, the demagnetizing field will work to demagnetize the magnet, decreasing its magnetic properties. The strength of the demagnetizing field is proportional to the magnet's magnetization and shape, according to

Here, is called the demagnetizing factor, and has a different value depending on the magnet's shape. For example, if the magnet is a sphere, then .

The value of the demagnetizing factor also depends on the direction of the magnetization in relation to the magnet's shape. Since a sphere is symmetrical from all angles, the demagnetizing factor only has one value. But a magnet that is shaped like a long cylinder will yield two different demagnetizing factors, depending on if it's magnetized parallel to or perpendicular to its length.[16]

Common uses

[edit]

- Magnetic recording media: VHS tapes contain a reel of magnetic tape. The information that makes up the video and sound is encoded on the magnetic coating on the tape. Common audio cassettes also rely on magnetic tape. Similarly, in computers, floppy disks and hard disks record data on a thin magnetic coating.[27]

- Credit, debit, and automatic teller machine cards: All of these cards have a magnetic strip on one side. This strip encodes the information to contact an individual's financial institution and connect with their account(s).[28]

- Older types of televisions (non flat screen) and older large computer monitors: TV and computer screens containing a cathode-ray tube employ an electromagnet to guide electrons to the screen.[29]

- Sensor: Permanent magnets are useful components for fabricating magnetic sensors for the detection of motion, displacement, position, and so forth.[30]

- Speakers and microphones: Most speakers employ a permanent magnet and a current-carrying coil to convert electric energy (the signal) into mechanical energy (movement that creates the sound). The coil is wrapped around a bobbin attached to the speaker cone and carries the signal as changing current that interacts with the field of the permanent magnet. The voice coil feels a magnetic force and in response, moves the cone and pressurizes the neighboring air, thus generating sound. Dynamic microphones employ the same concept, but in reverse. A microphone has a diaphragm or membrane attached to a coil of wire. The coil rests inside a specially shaped magnet. When sound vibrates the membrane, the coil is vibrated as well. As the coil moves through the magnetic field, a voltage is induced across the coil. This voltage drives a current in the wire that is characteristic of the original sound.

- Electric guitars use magnetic pickups to transduce the vibration of guitar strings into electric current that can then be amplified. This is different from the principle behind the speaker and dynamic microphone because the vibrations are sensed directly by the magnet, and a diaphragm is not employed. The Hammond organ used a similar principle, with rotating tonewheels instead of strings.

- Electric motors and generators: Some electric motors rely upon a combination of an electromagnet and a permanent magnet, and, much like loudspeakers, they convert electric energy into mechanical energy. A generator is the reverse: it converts mechanical energy into electric energy by moving a conductor through a magnetic field.

- Medicine: Hospitals use magnetic resonance imaging to spot problems in a patient's organs without invasive surgery.

- Chemistry: Chemists use nuclear magnetic resonance to characterize synthesized compounds.

- Chucks are used in the metalworking field to hold objects. Magnets are also used in other types of fastening devices, such as the magnetic base, the magnetic clamp and the refrigerator magnet.

- Compasses: A compass (or mariner's compass) is a magnetized pointer free to align itself with a magnetic field, most commonly Earth's magnetic field.

- Art: Vinyl magnet sheets may be attached to paintings, photographs, and other ornamental articles, allowing them to be attached to refrigerators and other metal surfaces. Objects and paint can be applied directly to the magnet surface to create collage pieces of art. Metal magnetic boards, strips, doors, microwave ovens, dishwashers, cars, metal I beams, and any metal surface can be used magnetic vinyl art.

- Science projects: Many topic questions are based on magnets, including the repulsion of current-carrying wires, the effect of temperature, and motors involving magnets.[31]

- Toys: Given their ability to counteract the force of gravity at close range, magnets are often employed in children's toys, such as the Magnet Space Wheel and Levitron, to amusing effect.

- Refrigerator magnets are used to adorn kitchens, as a souvenir, or simply to hold a note or photo to the refrigerator door.

- Magnets can be used to make jewelry. Necklaces and bracelets can have a magnetic clasp, or may be constructed entirely from a linked series of magnets and ferrous beads.

- Magnets can pick up magnetic items (iron nails, staples, tacks, paper clips) that are either too small, too hard to reach, or too thin for fingers to hold. Some screwdrivers are magnetized for this purpose.

- Magnets can be used in scrap and salvage operations to separate magnetic metals (iron, cobalt, and nickel) from non-magnetic metals (aluminum, non-ferrous alloys, etc.). The same idea can be used in the so-called "magnet test", in which a car chassis is inspected with a magnet to detect areas repaired using fiberglass or plastic putty.

- Magnets are found in process industries, food manufacturing especially, in order to remove metal foreign bodies from materials entering the process (raw materials) or to detect a possible contamination at the end of the process and prior to packaging. They constitute an important layer of protection for the process equipment and for the final consumer.[32]

- Magnetic levitation transport, or maglev, is a form of transportation that suspends, guides and propels vehicles (especially trains) through electromagnetic force. Eliminating rolling resistance increases efficiency. The maximum recorded speed of a maglev train is 581 kilometers per hour (361 mph).

- Magnets may be used to serve as a fail-safe device for some cable connections. For example, the power cords of some laptops are magnetic to prevent accidental damage to the port when tripped over. The MagSafe power connection to the Apple MacBook is one such example.

Medical issues and safety

[edit]Because human tissues have a very low level of susceptibility to static magnetic fields, there is little mainstream scientific evidence showing a health effect associated with exposure to static fields. Dynamic magnetic fields may be a different issue, however; correlations between electromagnetic radiation and cancer rates have been postulated due to demographic correlations (see Electromagnetic radiation and health).

If a ferromagnetic foreign body is present in human tissue, an external magnetic field interacting with it can pose a serious safety risk.[33]

A different type of indirect magnetic health risk exists involving pacemakers. If a pacemaker has been embedded in a patient's chest (usually for the purpose of monitoring and regulating the heart for steady electrically induced beats), care should be taken to keep it away from magnetic fields. It is for this reason that a patient with the device installed cannot be tested with the use of a magnetic resonance imaging device.

Children sometimes swallow small magnets from toys, and this can be hazardous if two or more magnets are swallowed, as the magnets can pinch or puncture internal tissues.[34]

Magnetic imaging devices (e.g. MRIs) generate enormous magnetic fields, and therefore rooms intended to hold them exclude ferrous metals. Bringing objects made of ferrous metals (such as oxygen canisters) into such a room creates a severe safety risk, as those objects may be powerfully thrown about by the intense magnetic fields.

Magnetizing ferromagnets

[edit]Ferromagnetic materials can be magnetized in the following ways:

- Heating the object higher than its Curie temperature, allowing it to cool in a magnetic field and hammering it as it cools. This is the most effective method and is similar to the industrial processes used to create permanent magnets.

- Placing the item in an external magnetic field will result in the item retaining some of the magnetism on removal. Vibration has been shown to increase the effect. Ferrous materials aligned with the Earth's magnetic field that are subject to vibration (e.g., frame of a conveyor) have been shown to acquire significant residual magnetism. Likewise, striking a steel nail held by fingers in a N-S direction with a hammer will temporarily magnetize the nail.

- Stroking: An existing magnet is moved from one end of the item to the other repeatedly in the same direction (single touch method) or two magnets are moved outwards from the center of a third (double touch method).[35]

- Electric Current: The magnetic field produced by passing an electric current through a coil can get domains to line up. Once all of the domains are lined up, increasing the current will not increase the magnetization.[36]

Demagnetizing ferromagnets

[edit]Magnetized ferromagnetic materials can be demagnetized (or degaussed) in the following ways:

- Heating a magnet past its Curie temperature; the molecular motion destroys the alignment of the magnetic domains, completely demagnetizing it

- Placing the magnet in an alternating magnetic field with intensity above the material's coercivity and then either slowly drawing the magnet out or slowly decreasing the magnetic field to zero. This is the principle used in commercial demagnetizers to demagnetize tools, erase credit cards, hard disks, and degaussing coils used to demagnetize CRTs.

- Some demagnetization or reverse magnetization will occur if any part of the magnet is subjected to a reverse field above the magnetic material's coercivity.

- Demagnetization progressively occurs if the magnet is subjected to cyclic fields sufficient to move the magnet away from the linear part on the second quadrant of the B–H curve of the magnetic material (the demagnetization curve).

- Hammering or jarring: mechanical disturbance tends to randomize the magnetic domains and reduce magnetization of an object, but may cause unacceptable damage.

Types of permanent magnets

[edit]Magnetic metallic elements

[edit]Many materials have unpaired electron spins, and the majority of these materials are paramagnetic. When the spins interact with each other in such a way that the spins align spontaneously, the materials are called ferromagnetic (what is often loosely termed as magnetic). Because of the way their regular crystalline atomic structure causes their spins to interact, some metals are ferromagnetic when found in their natural states, as ores. These include iron ore (magnetite or lodestone), cobalt and nickel, as well as the rare earth metals gadolinium and dysprosium (when at a very low temperature). Such naturally occurring ferromagnets were used in the first experiments with magnetism. Technology has since expanded the availability of magnetic materials to include various man-made products, all based, however, on naturally magnetic elements.

Composites

[edit]

Ceramic, or ferrite, magnets are made of a sintered composite of powdered iron oxide and barium/strontium carbonate ceramic. Given the low cost of the materials and manufacturing methods, inexpensive magnets (or non-magnetized ferromagnetic cores, for use in electronic components such as portable AM radio antennas) of various shapes can be easily mass-produced. The resulting magnets are non-corroding but brittle and must be treated like other ceramics.

Alnico magnets are made by casting or sintering a combination of aluminium, nickel and cobalt with iron and small amounts of other elements added to enhance the properties of the magnet. Sintering offers superior mechanical characteristics, whereas casting delivers higher magnetic fields and allows for the design of intricate shapes. Alnico magnets resist corrosion and have physical properties more forgiving than ferrite, but not quite as desirable as a metal. Trade names for alloys in this family include: Alni, Alcomax, Hycomax, Columax, and Ticonal.[37]

Injection-molded magnets are a composite of various types of resin and magnetic powders, allowing parts of complex shapes to be manufactured by injection molding. The physical and magnetic properties of the product depend on the raw materials, but are generally lower in magnetic strength and resemble plastics in their physical properties.

Flexible magnet

[edit]Flexible magnets are composed of a high-coercivity ferromagnetic compound (usually ferric oxide) mixed with a resinous polymer binder.[38] This is extruded as a sheet and passed over a line of powerful cylindrical permanent magnets. These magnets are arranged in a stack with alternating magnetic poles facing up (N, S, N, S...) on a rotating shaft. This impresses the plastic sheet with the magnetic poles in an alternating line format. No electromagnetism is used to generate the magnets. The pole-to-pole distance is on the order of 5 mm, but varies with manufacturer. These magnets are lower in magnetic strength but can be very flexible, depending on the binder used.[39]

For magnetic compounds (e.g. Nd2Fe14B) that are vulnerable to a grain boundary corrosion problem it gives additional protection.[38]

Rare-earth magnets

[edit]

Rare earth (lanthanoid) elements have a partially occupied f electron shell (which can accommodate up to 14 electrons). The spin of these electrons can be aligned, resulting in very strong magnetic fields, and therefore, these elements are used in compact high-strength magnets where their higher price is not a concern. The most common types of rare-earth magnets are samarium–cobalt and neodymium–iron–boron (NIB) magnets.

Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) and single-chain magnets (SCMs)

[edit]In the 1990s, it was discovered that certain molecules containing paramagnetic metal ions are capable of storing a magnetic moment at very low temperatures. These are very different from conventional magnets that store information at a magnetic domain level and theoretically could provide a far denser storage medium than conventional magnets. In this direction, research on monolayers of SMMs is currently under way. Very briefly, the two main attributes of an SMM are:

- a large ground state spin value (S), which is provided by ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic coupling between the paramagnetic metal centres

- a negative value of the anisotropy of the zero field splitting (D)

Most SMMs contain manganese but can also be found with vanadium, iron, nickel and cobalt clusters. More recently, it has been found that some chain systems can also display a magnetization that persists for long times at higher temperatures. These systems have been called single-chain magnets.

Nano-structured magnets

[edit]Some nano-structured materials exhibit energy waves, called magnons, that coalesce into a common ground state in the manner of a Bose–Einstein condensate.[40][41]

Rare-earth-free permanent magnets

[edit]The United States Department of Energy has identified a need to find substitutes for rare-earth metals in permanent-magnet technology, and has begun funding such research. The Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) has sponsored a Rare Earth Alternatives in Critical Technologies (REACT) program to develop alternative materials. In 2011, ARPA-E awarded 31.6 million dollars to fund Rare-Earth Substitute projects.[42] Iron nitrides are promising materials for rare-earth free magnets.[43]

Costs

[edit]The current[update] cheapest permanent magnets, allowing for field strengths, are flexible and ceramic magnets, but these are also among the weakest types. The ferrite magnets are mainly low-cost magnets since they are made from cheap raw materials: iron oxide and Ba- or Sr-carbonate. However, a new low cost magnet, Mn–Al alloy,[38][non-primary source needed][44][45] has been developed and is now dominating the low-cost magnets field.[citation needed] It has a higher saturation magnetization than the ferrite magnets. It also has more favorable temperature coefficients, although it can be thermally unstable. Neodymium–iron–boron (NIB) magnets are among the strongest. These cost more per kilogram than most other magnetic materials but, owing to their intense field, are smaller and cheaper in many applications.[46]

Temperature

[edit]Temperature sensitivity varies, but when a magnet is heated to a temperature known as the Curie point, it loses all of its magnetism, even after cooling below that temperature. The magnets can often be remagnetized, however.

Additionally, some magnets are brittle and can fracture at high temperatures.

The maximum usable temperature is highest for alnico magnets at over 540 °C (1,000 °F), around 300 °C (570 °F) for ferrite and SmCo, about 140 °C (280 °F) for NIB and lower for flexible ceramics, but the exact numbers depend on the grade of material.

Electromagnets

[edit]An electromagnet, in its simplest form, is a wire that has been coiled into one or more loops, known as a solenoid. When electric current flows through the wire, a magnetic field is generated. It is concentrated near (and especially inside) the coil, and its field lines are very similar to those of a magnet. The orientation of this effective magnet is determined by the right hand rule. The magnetic moment and the magnetic field of the electromagnet are proportional to the number of loops of wire, to the cross-section of each loop, and to the current passing through the wire.[47]

If the coil of wire is wrapped around a material with no special magnetic properties (e.g., cardboard), it will tend to generate a very weak field. However, if it is wrapped around a soft ferromagnetic material, such as an iron nail, then the net field produced can result in a several hundred- to thousandfold increase of field strength.

Uses for electromagnets include particle accelerators, electric motors, junkyard cranes, and magnetic resonance imaging machines. Some applications involve configurations more than a simple magnetic dipole; for example, quadrupole and sextupole magnets are used to focus particle beams.

Units and calculations

[edit]For most engineering applications, MKS (rationalized) or SI (Système International) units are commonly used. Two other sets of units, Gaussian and CGS-EMU, are the same for magnetic properties and are commonly used in physics.[citation needed]

In all units, it is convenient to employ two types of magnetic field, B and H, as well as the magnetization M, defined as the magnetic moment per unit volume.

- The magnetic induction field B is given in SI units of teslas (T). B is the magnetic field whose time variation produces, by Faraday's Law, circulating electric fields (which the power companies sell). B also produces a deflection force on moving charged particles (as in TV tubes). The tesla is equivalent to the magnetic flux (in webers) per unit area (in meters squared), thus giving B the unit of a flux density. In CGS, the unit of B is the gauss (G). One tesla equals 104 G.

- The magnetic field H is given in SI units of ampere-turns per meter (A-turn/m). The turns appear because when H is produced by a current-carrying wire, its value is proportional to the number of turns of that wire. In CGS, the unit of H is the oersted (Oe). One A-turn/m equals 4π×10−3 Oe.

- The magnetization M is given in SI units of amperes per meter (A/m). In CGS, the unit of M is the oersted (Oe). One A/m equals 10−3 emu/cm3. A good permanent magnet can have a magnetization as large as a million amperes per meter.

- In SI units, the relation B = μ0(H + M) holds, where μ0 is the permeability of space, which equals 4π×10−7 T•m/A. In CGS, it is written as B = H + 4πM. (The pole approach gives μ0H in SI units. A μ0M term in SI must then supplement this μ0H to give the correct field within B, the magnet. It will agree with the field B calculated using Ampèrian currents).

Materials that are not permanent magnets usually satisfy the relation M = χH in SI, where χ is the (dimensionless) magnetic susceptibility. Most non-magnetic materials have a relatively small χ (on the order of a millionth), but soft magnets can have χ on the order of hundreds or thousands. For materials satisfying M = χH, we can also write B = μ0(1 + χ)H = μ0μrH = μH, where μr = 1 + χ is the (dimensionless) relative permeability and μ =μ0μr is the magnetic permeability. Both hard and soft magnets have a more complex, history-dependent, behavior described by what are called hysteresis loops, which give either B vs. H or M vs. H. In CGS, M = χH, but χSI = 4πχCGS, and μ = μr.

Caution: in part because there are not enough Roman and Greek symbols, there is no commonly agreed-upon symbol for magnetic pole strength and magnetic moment. The symbol m has been used for both pole strength (unit A•m, where here the upright m is for meter) and for magnetic moment (unit A•m2). The symbol μ has been used in some texts for magnetic permeability and in other texts for magnetic moment. We will use μ for magnetic permeability and m for magnetic moment. For pole strength, we will employ qm. For a bar magnet of cross-section A with uniform magnetization M along its axis, the pole strength is given by qm = MA, so that M can be thought of as a pole strength per unit area.

Fields of a magnet

[edit]

Far away from a magnet, the magnetic field created by that magnet is almost always described (to a good approximation) by a dipole field characterized by its total magnetic moment. This is true regardless of the shape of the magnet, so long as the magnetic moment is non-zero. One characteristic of a dipole field is that the strength of the field falls off inversely with the cube of the distance from the magnet's center.

Closer to the magnet, the magnetic field becomes more complicated and more dependent on the detailed shape and magnetization of the magnet. Formally, the field can be expressed as a multipole expansion: A dipole field, plus a quadrupole field, plus an octupole field, etc.

At close range, many different fields are possible. For example, for a long, skinny bar magnet with its north pole at one end and south pole at the other, the magnetic field near either end falls off inversely with the square of the distance from that pole.

Calculating the magnetic force

[edit]Pull force of a single magnet

[edit]The strength of a given magnet is sometimes given in terms of its pull force — its ability to pull ferromagnetic objects.[48] The pull force exerted by either an electromagnet or a permanent magnet with no air gap (i.e., the ferromagnetic object is in direct contact with the pole of the magnet[49]) is given by the Maxwell equation:[50]

- ,

where:

- F is force (SI unit: newton)

- A is the cross section of the area of the pole (in square meters)

- B is the magnetic induction exerted by the magnet.

This result can be easily derived using Gilbert model, which assumes that the pole of magnet is charged with magnetic monopoles that induces the same in the ferromagnetic object.

If a magnet is acting vertically, it can lift a mass m in kilograms given by the simple equation:

where g is the gravitational acceleration.

Force between two magnetic poles

[edit]Classically, the force between two magnetic poles is given by:[51]

where

- F is force (SI unit: newton)

- qm1 and qm2 are the magnitudes of magnetic poles (SI unit: ampere-meter)

- μ is the permeability of the intervening medium (SI unit: tesla meter per ampere, henry per meter or newton per ampere squared)

- r is the separation (SI unit: meter).

The pole description is useful to the engineers designing real-world magnets, but real magnets have a pole distribution more complex than a single north and south. Therefore, implementation of the pole idea is not simple. In some cases, one of the more complex formulae given below will be more useful.

Force between two nearby magnetized surfaces of area A

[edit]The mechanical force between two nearby magnetized surfaces can be calculated with the following equation. The equation is valid only for cases in which the effect of fringing is negligible and the volume of the air gap is much smaller than that of the magnetized material:[52][53]

where:

- A is the area of each surface, in m2

- H is their magnetizing field, in A/m

- μ0 is the permeability of space, which equals 4π×10−7 T•m/A

- B is the flux density, in T.

Force between two bar magnets

[edit]The force between two identical cylindrical bar magnets placed end to end at large distance is approximately:[dubious – discuss],[52]

where:

- B0 is the magnetic flux density very close to each pole, in T,

- A is the area of each pole, in m2,

- L is the length of each magnet, in m,

- R is the radius of each magnet, in m, and

- z is the separation between the two magnets, in m.

- relates the flux density at the pole to the magnetization of the magnet.

Note that all these formulations are based on Gilbert's model, which is usable in relatively great distances. In other models (e.g., Ampère's model), a more complicated formulation is used that sometimes cannot be solved analytically. In these cases, numerical methods must be used.

Force between two cylindrical magnets

[edit]For two cylindrical magnets with radius and length , with their magnetic dipole aligned, the force can be asymptotically approximated at large distance by,[54]

where is the magnetization of the magnets and is the gap between the magnets. A measurement of the magnetic flux density very close to the magnet is related to approximately by the formula

The effective magnetic dipole can be written as

Where is the volume of the magnet. For a cylinder, this is .

When , the point dipole approximation is obtained,

which matches the expression of the force between two magnetic dipoles.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Platonis Opera Archived 2018-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, Meyer and Zeller, 1839, p. 989.

- ^ The location of Magnesia is debated; it could be the region in mainland Greece or Magnesia ad Sipylum. See, for example, "Magnet". Language Hat blog. 28 May 2005. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Fowler, Michael (1997). "Historical Beginnings of Theories of Electricity and Magnetism". Archived from the original on 2008-03-15. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ Vowles, Hugh P. (1932). "Early Evolution of Power Engineering". Isis. 17 (2): 412–420 [419–20]. doi:10.1086/346662. S2CID 143949193.

- ^ Li Shu-hua (1954). "Origine de la Boussole II. Aimant et Boussole". Isis. 45 (2): 175–196. doi:10.1086/348315. JSTOR 227361. S2CID 143585290.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BOOK XXXIV. THE NATURAL HISTORY OF METALS., CHAP. 42.—THE METAL CALLED LIVE IRON Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine. Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved on 2011-05-17.

- ^ a b c Coey, J. M. D. (2009). Magnetism and magnetic materials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-511-68515-6. OCLC 664016090.

- ^ "Four Great Inventions of Ancient China". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Republic of South Africa. 2004-12-13. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Schmidl, Petra G. (1996–1997). "Two Early Arabic Sources On The Magnetic Compass" (PDF). Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies. 1: 81–132. doi:10.5617/jais.4547. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-24.

- ^ "The Seven Magnetic Moments - Modern Magnets". Trinity College Dublin. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Müller, Karl-Hartmut; Sawatzki, Simon; Gauß, Roland; Gutfleisch, Oliver (2021), Coey, J. M. D.; Parkin, Stuart S.P. (eds.), "Permanent Magnet Materials and Applications", Handbook of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Cham: Springer International Publishing, p. 1391, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63210-6_29, ISBN 978-3-030-63210-6, S2CID 244736617

- ^ Delaunay, Jean (2008). Ampère, André-Marie. Vol. 1. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 142–149.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Joseph Henry – Engineering Hall of Fame". Edison Tech Center. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 255–8. ISBN 0-13-805326-X. OCLC 40251748.

- ^ Knight, Jones, & Field, "College Physics" (2007) p. 815.

- ^ a b Cullity, B. D. & Graham, C. D. (2008). Introduction to Magnetic Materials (2 ed.). Wiley-IEEE Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-471-47741-9.

- ^ Boyer, Timothy H. (1988). "The Force on a Magnetic Dipole". American Journal of Physics. 56 (8): 688–692. Bibcode:1988AmJPh..56..688B. doi:10.1119/1.15501.

- ^ "Units for Magnetic Properties" (PDF). Lake Shore Cryotronics, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ^ Allen, Zachariah (1852). Philosophy of the Mechanics of Nature, and the Source and Modes of Action of Natural Motive-Power. D. Appleton and Company. p. 252.

- ^ Saslow, Wayne M. (2002). Electricity, Magnetism, and Light (3rd ed.). Academic Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-12-619455-5. Archived from the original on 2014-06-27.

- ^ "Right Hand Rule". PASCO scientific. 2024-08-01.

- ^ Serway, Raymond A.; Chris Vuille (2006). Essentials of college physics. USA: Cengage Learning. p. 493. ISBN 0-495-10619-4. Archived from the original on 2013-06-04.

- ^ Emiliani, Cesare (1992). Planet Earth: Cosmology, Geology, and the Evolution of Life and Environment. UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-521-40949-7. Archived from the original on 2016-12-24.

- ^ Manners, Joy (2000). Static Fields and Potentials. USA: CRC Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-7503-0718-8. Archived from the original on 2016-12-24.

- ^ a b Nave, Carl R. (2010). "Bar Magnet". Hyperphysics. Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, Georgia State Univ. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ Mice levitated in NASA lab Archived 2011-02-09 at the Wayback Machine. Livescience.com (2009-09-09). Retrieved on 2011-10-08.

- ^ Mallinson, John C. (1987). The foundations of magnetic recording (2nd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-466626-4.

- ^ "The stripe on a credit card". How Stuff Works. 27 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-06-24. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Electromagnetic deflection in a cathode ray tube, I". National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ FRADEN, JACOB (2004). HANDBOOK OF MODERN SENSORS (3rd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 55. ISBN 0-387-00750-4.

- ^ "Snacks about magnetism". The Exploratorium Science Snacks. Exploratorium. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Neodymium Magnets: Strength, design for tramp metal removal". Archived from the original on 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2016-12-05. Source on magnets in process industries

- ^ Schenck JF (2000). "Safety of strong, static magnetic fields". J Magn Reson Imaging. 12 (1): 2–19. doi:10.1002/1522-2586(200007)12:1<2::AID-JMRI2>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 10931560. S2CID 19976829.

- ^ Oestreich AE (2008). "Worldwide survey of damage from swallowing multiple magnets". Pediatr Radiol. 39 (2): 142–7. doi:10.1007/s00247-008-1059-7. PMID 19020871. S2CID 21306900.

- ^ McKenzie, A. E. E. (1961). Magnetism and electricity. Cambridge. pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Ferromagnetic Materials". Phares Electronics. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Brady, George Stuart; Henry R. Clauser; John A. Vaccari (2002). Materials Handbook: An Encyclopedia for Managers. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 577. ISBN 0-07-136076-X. Archived from the original on 2016-12-24.

- ^ a b c "Nanostructured Mn-Al Permanent Magnets (patent)". Retrieved 18 Feb 2017.

- ^ "Press release: Fridge magnet transformed". Riken. March 11, 2011. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017.

- ^ "Nanomagnets Bend The Rules". Archived from the original on December 7, 2005. Retrieved November 14, 2005.

- ^ Della Torre, E.; Bennett, L.; Watson, R. (2005). "Extension of the Bloch T3/2 Law to Magnetic Nanostructures: Bose-Einstein Condensation". Physical Review Letters. 94 (14) 147210. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..94n7210D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.147210. PMID 15904108.

- ^ "Research Funding for Rare Earth Free Permanent Magnets". ARPA-E. Archived from the original on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ By (2022-09-01). "Iron Nitrides: Powerful Magnets Without The Rare Earth Elements". Hackaday. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Keller, Thomas; Baker, Ian (2022-02-01). "Manganese-based permanent magnet materials". Progress in Materials Science. 124 100872. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2021.100872. ISSN 0079-6425.

- ^ An Overview of MnAl Permanent Magnets with a Study on Their Potential in Electrical Machines

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions Archived 2008-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Magnet sales & Mfct Co Inc. Retrieved on 2011-10-08.

- ^ Ruskell, Todd; Tipler, Paul A.; Mosca, Gene (2007). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4292-0410-1.

- ^ "How Much Will a Magnet Hold?". www.kjmagnetics.com. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ "Magnetic Pull Force Explained - What is Magnet Pull Force? | Dura Magnetics USA". 19 October 2016. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ Cardarelli, François (2008). Materials Handbook: A Concise Desktop Reference (Second ed.). Springer. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-84628-668-1. Archived from the original on 2016-12-24.

- ^ "Basic Relationships". Geophysics.ou.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-07-09. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ^ a b "Magnetic Fields and Forces". Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ "The force produced by a magnetic field". Archived from the original on 2010-03-17. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ^ David Vokoun; Marco Beleggia; Ludek Heller; Petr Sittner (2009). "Magnetostatic interactions and forces between cylindrical permanent magnets". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 321 (22): 3758–3763. Bibcode:2009JMMM..321.3758V. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.07.030. hdl:11380/1255408.

References

[edit]- "The Early History of the Permanent Magnet". Edward Neville Da Costa Andrade, Endeavour, Volume 17, Number 65, January 1958. Contains an excellent description of early methods of producing permanent magnets.

- "positive pole n". The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

- Wayne M. Saslow, Electricity, Magnetism, and Light, Academic (2002). ISBN 0-12-619455-6. Chapter 9 discusses magnets and their magnetic fields using the concept of magnetic poles, but it also gives evidence that magnetic poles do not really exist in ordinary matter. Chapters 10 and 11, following what appears to be a 19th-century approach, use the pole concept to obtain the laws describing the magnetism of electric currents.

- Edward P. Furlani, Permanent Magnet and Electromechanical Devices:Materials, Analysis and Applications, Academic Press Series in Electromagnetism (2001). ISBN 0-12-269951-3.

External links

[edit]- How magnets are made Archived 2013-03-16 at the Wayback Machine (video)

- Floating Ring Magnets, Bulletin of the IAPT, Volume 4, No. 6, 145 (June 2012). (Publication of the Indian Association of Physics Teachers).

- A brief history of electricity and magnetism Archived 2021-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

Magnet

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Discoveries

The earliest recorded observations of magnetic phenomena date back to ancient Greece, where the philosopher Thales of Miletus, around 600 BCE, noted that lodestone—a naturally magnetized form of magnetite—attracted iron filings and other pieces of iron, describing it as a form of animation in the stone itself.[8] This observation, preserved in later accounts by Aristotle, marked one of the first documented recognitions of magnetism as a distinct natural force, though Thales did not fully explain its mechanism. Independently, in ancient China during the Warring States period (circa 400–200 BCE), lodestone was employed in divination practices, with spoon-shaped devices placed on smooth surfaces to align with cosmic directions, symbolizing harmony with the universe; by the Han dynasty (around 200 BCE), these evolved into early magnetic compasses used for geomancy rather than navigation.[9] In the Roman era, Pliny the Elder provided a more detailed account of lodestone's properties in his encyclopedic work Natural History (completed in 77 CE), describing how the stone from Magnesia in Lydia attracted iron, could suspend iron rings in a chain-like fashion, and even influenced the construction of temples by repelling iron tools.[10] Pliny attributed the discovery to a shepherd named Magnes whose iron-nailed shoes stuck to the ground near such stones, blending empirical description with mythological elements, and he noted its use in detecting poisons or testing for iron in mixtures. Knowledge of these magnetic properties spread through trade and scholarship, reaching the Islamic world by the 9th century, where scholars described lodestone's attraction in technical treatises. By the medieval period in Europe, understanding of magnets was largely derived from Arabic translations and texts, such as those by Al-Ash'ari and later works on the qibla (direction to Mecca), which incorporated magnetic needles floating in water bowls for orientation.[11] This knowledge facilitated the adoption of the magnetic compass for maritime navigation in the Mediterranean by the 12th century, as evidenced in European portolan charts and navigation manuals like the Epistola de magnete (1269).[12] A pivotal advancement came in the early 17th century with English physician William Gilbert's De Magnete (1600), the first systematic scientific treatise on magnetism, where he conducted extensive experiments using a spherical lodestone (terrella) to model Earth's magnetic field and demonstrated that the planet itself acts as a giant magnet, explaining compass behavior.[13] Gilbert also clearly distinguished magnetism from the electric attraction produced by rubbed amber (elektron), classifying the former as a property of iron and loadstones involving directional alignment, while the latter was a temporary frictional effect limited to lighter substances; this separation laid foundational groundwork for modern physics.[14]Modern Developments

The modern era of magnetism began with Hans Christian Ørsted's groundbreaking discovery in 1820, when he observed that an electric current flowing through a wire caused a nearby compass needle to deflect, demonstrating the intimate connection between electricity and magnetism.[15] This experiment, conducted during a lecture in Copenhagen, marked the birth of electromagnetism as a unified field of study and inspired rapid advancements in the field.[16] Building on Ørsted's findings, André-Marie Ampère conducted extensive experiments in the 1820s to quantify the magnetic forces produced by electric currents. He established that parallel currents attract each other while antiparallel currents repel, formulating Ampère's law to describe these interactions mathematically.[16] Ampère's work also led to the definition of the ampere as the fundamental unit of electric current, based on the force between two current-carrying wires, a standard formalized later in the International System of Units.[16] In 1831, Michael Faraday advanced the field through his discovery of electromagnetic induction, showing that a changing magnetic field could induce an electric current in a nearby circuit.[17] Faraday's experiments with coils and moving magnets laid the foundation for electric generators and transformers, enabling the practical generation and distribution of electrical power on an industrial scale.[17] The theoretical unification of these phenomena culminated in the 1860s with James Clerk Maxwell's formulation of a set of equations that described electromagnetism as a single, coherent force.[18] Maxwell's equations predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves, including light, and provided the mathematical framework for subsequent technologies like radio and wireless communication.[18] The 20th century saw significant progress in permanent magnet materials, beginning with the development of Alnico alloys in the 1930s, which combined aluminum, nickel, cobalt, and iron to achieve higher magnetic strength and stability than earlier carbon steel magnets.[19] These cast magnets enabled more compact designs in electric motors and generators, revolutionizing applications in appliances and early electronics.[19] Concurrently, ferrite materials, composed of iron oxide combined with ceramic compounds like strontium or barium, emerged in the 1930s for soft magnetic applications but evolved into hard ferrites by the 1950s, offering cost-effective permanent magnets with good corrosion resistance for loudspeakers and motors.[20] Rare-earth magnets marked a leap in performance during the late 20th century. Samarium-cobalt (SmCo) magnets, developed in the 1960s, provided exceptional coercivity and temperature stability, making them ideal for aerospace and military applications where high reliability under extreme conditions was essential.[21] These magnets, particularly the SmCo5 formulation, achieved energy products up to 30 MGOe, surpassing previous materials and enabling miniaturization in devices.[21] In the 1980s, neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets were invented, offering even higher energy products—reaching 50 MGOe or more—and dominating consumer electronics, electric vehicles, and wind turbines due to their superior strength-to-weight ratio.[22] A pivotal milestone in superconducting magnets occurred in 1986 with the discovery of high-temperature superconductors, such as yttrium barium copper oxide (YBCO), which exhibit zero electrical resistance at temperatures above the boiling point of liquid nitrogen (77 K).[23] This breakthrough, awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1987, enabled more efficient and compact magnetic systems for MRI machines, particle accelerators, and power transmission, reducing reliance on costly liquid helium cooling.[23] In recent years, efforts to mitigate supply chain vulnerabilities from rare-earth elements have led to AI-accelerated discoveries of alternative permanent magnets. In 2024, the UK-based company Materials Nexus announced MagNex, an AI-designed rare-earth-free magnet composed of abundant elements like iron, nitrogen, and carbon, achieving magnetic performance comparable to traditional rare-earth magnets while being more sustainable and cost-effective for electric motors and renewable energy applications.[24] This innovation, developed using machine learning to screen millions of material combinations in weeks rather than decades, represents a high-impact step toward reducing global dependence on critical minerals.[24]Fundamental Concepts

Magnetic Fields

A magnetic field is defined as the region surrounding a magnet in which the magnetic influence of the magnet can be detected, manifesting as forces on other magnetic materials or moving charges. This invisible field can be visualized experimentally by sprinkling iron filings around a bar magnet, which align along the field's direction to reveal its patterns, or by using a compass needle that orients itself parallel to the field lines at any point.[25][26][27] Magnetic field lines provide a conventional representation of the field's direction and relative strength, emerging from the north pole of a magnet and curving to enter at the south pole, forming continuous closed loops. The direction of these lines indicates the path a free north pole would follow, while their density—closer spacing near the poles—corresponds to stronger field intensity.[28][29] A prominent natural example of a magnetic field is Earth's geomagnetic field, generated by dynamo action in the planet's molten outer core, which protects the surface from solar wind and enables navigation via compasses. This field approximates a dipole, with geomagnetic poles defined as the intersections of the best-fit dipole axis with Earth's surface (north geomagnetic pole at approximately 80.8°N, 72.8°W as of 2025). The magnetic poles, where the field lines are vertical, are near but distinct from the geographic poles, with the north magnetic pole at approximately 85.8°N, 139.3°E as of 2025; both are in the Arctic region but the magnetic pole is drifting toward Siberia.[30][31] The strength of magnetic fields is quantified in SI units as tesla (T), where 1 T equals 10,000 gauss (G) in the older cgs system, with Earth's surface field typically around 25 to 65 microtesla (0.25 to 0.65 G). The concept of field lines as a visualization tool originated with Michael Faraday in the 1830s, who introduced "lines of force" to depict the spatial distribution of magnetic effects based on his experiments with iron filings and compasses.[32][33]Magnetic Moments and Magnetization

The atomic magnetic moment originates from the intrinsic properties of electrons, specifically their orbital angular momentum and spin angular momentum. The orbital magnetic moment is given by , where is the electron charge, is the electron mass, and is the orbital angular momentum vector, while the spin magnetic moment is with for the electron spin -factor and the spin angular momentum vector.[34] The natural unit for these moments is the Bohr magneton, defined as J/T, which quantifies the scale of an electron's contribution to magnetism.[35] Magnetization represents the macroscopic magnetic strength of a material, defined as the total magnetic moment per unit volume, a vector quantity with units of amperes per meter (A/m).[36] It arises from the collective alignment of atomic magnetic moments within the material. In the context of magnetic fields, the magnetic induction (in tesla) relates to the magnetic field strength (in A/m) and magnetization via the equation , where H/m is the permeability of free space; this decomposition separates the contributions from external sources () and material response ().[37][38] For paramagnetic materials, where atomic moments align weakly with an applied field due to thermal disorder, the magnetization obeys Curie's law: , with the material-specific Curie constant and the absolute temperature in kelvin; this linear response diminishes inversely with temperature as thermal agitation randomizes the moments.[39] In contrast, ferromagnetic materials exhibit strong, cooperative alignment of moments, leading to hysteresis in the magnetization curve: as increases, saturates, but upon reducing to zero, a remnant magnetization persists due to domain pinning and exchange interactions, requiring a coercive field to reverse.[40] These atomic-scale moments, when aggregated, produce the observable magnetic field lines that characterize material behavior.[41]Polarity and Magnetic Poles

Magnets exhibit polarity through the presence of distinct north and south magnetic poles, which give rise to their directional behavior as dipoles. Unlike electric charges, which can exist in isolation as positive or negative monopoles, magnetic poles always occur in pairs: every north pole is accompanied by a corresponding south pole, and vice versa. This fundamental property ensures that magnets cannot be separated into isolated poles, a concept rooted in classical electromagnetism where magnetic field lines form closed loops without beginning or ending at a single point.[42][43] The convention for labeling magnetic poles dates to early observations using compasses, where the end of a magnet that aligns toward Earth's geographic North Pole is designated the north magnetic pole. In reality, this alignment occurs because Earth's geographic North Pole is near its magnetic south pole, attracting the north pole of the compass magnet. This nomenclature persists despite the underlying physics, facilitating consistent orientation in navigation and experiments. The interaction between magnetic poles follows an inverse-square law analogous to electrostatics; in the CGS electromagnetic unit system, the force between two poles of strengths and separated by distance is given by where is in dynes and is in emu units of pole strength (often simply called "units of pole"). Like poles repel, while opposite poles attract, reinforcing the dipole nature of magnets.[44][45][46] An illustrative demonstration of this indivisibility is breaking a bar magnet: instead of yielding isolated north and south poles (monopoles), the process creates two smaller magnets, each with its own north and south poles at the new ends. This occurs because the magnetization within the material reorients to maintain the dipole structure throughout. On a planetary scale, Earth's geomagnetic field also displays polarity and undergoes occasional reversals, where the north and south magnetic poles swap positions. These geomagnetic reversals happen irregularly, on average every few hundred thousand years, with the most recent occurring approximately 780,000 years ago; during such events, the field's intensity may weaken temporarily before stabilizing in the opposite orientation.[43][47][48]Magnetic Materials

Classification of Materials

Magnetic materials are classified based on their magnetic susceptibility, denoted as , which quantifies the degree of magnetization induced in a material by an applied magnetic field strength , according to the relation .[49] This classification arises from the response of atomic or molecular magnetic moments to external fields, categorizing materials into diamagnetic, paramagnetic, ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, and ferrimagnetic types.[5] Diamagnetic materials exhibit a weak repulsion from magnetic fields, characterized by a negative susceptibility (), typically on the order of to .[50] In these materials, all electrons are paired, resulting in no net magnetic moment, and the induced magnetization opposes the applied field.[49] Common examples include water, copper, and bismuth, which show no permanent magnetism and levitate slightly in strong magnetic fields due to this repulsive effect.[51] Paramagnetic materials display a weak attraction to magnetic fields, with a positive but small susceptibility (, typically to ), which follows Curie's law and vanishes without an external field.[50] Here, unpaired electrons or atoms produce random magnetic moments that align partially with the applied field, but thermal agitation limits the alignment.[49] Examples include aluminum, platinum, and liquid oxygen, which are only slightly drawn toward magnets and lose this property above certain temperatures.[51] Ferromagnetic materials show strong attraction to magnetic fields, with very high positive susceptibility () and the ability to retain permanent magnetization even after the field is removed, due to hysteresis in their magnetization curves.[5] This behavior stems from cooperative alignment of atomic moments below the Curie temperature, enabling spontaneous magnetization in domains.[49] Representative examples are iron, nickel, and cobalt, which can form magnets and exhibit significant magnetic effects at room temperature.[50] Antiferromagnetic materials feature ordered atomic magnetic moments that align in opposite directions, leading to internal cancellation and near-zero net magnetization, with susceptibility similar to paramagnets but showing a transition at the Néel temperature.[5] Examples include manganese oxide and chromium. Ferrimagnetic materials also have opposing alignments but with unequal moments, resulting in a net magnetization, as seen in ferrites like magnetite.[5] These types are distinguished by their spin ordering without the strong external response of ferromagnets.[52]Ferromagnetic Materials

Ferromagnetic materials are characterized by their ability to exhibit strong, spontaneous magnetization due to the alignment of atomic magnetic moments, enabling the creation of permanent magnets. This phenomenon arises from exchange interactions between neighboring atoms, leading to the formation of microscopic regions known as magnetic domains, where spins are aligned parallel within each domain but may point in different directions across domains. Pierre Weiss proposed the domain theory in 1907, suggesting that these domains minimize the material's magnetostatic energy, and an external magnetic field aligns them to produce net magnetization.[53] A key property is the Curie temperature (T_c), the critical point above which thermal agitation disrupts the aligned spins, causing the material to lose its ferromagnetic behavior and transition to paramagnetism. For pure iron, T_c is approximately 770°C (1043 K), above which it no longer retains permanent magnetism.[7] Saturation magnetization represents the maximum achievable magnetization when all domains are fully aligned, typically denoted as M_s; for iron, this value is about 1.7 × 10^6 A/m at room temperature, reflecting the density of aligned magnetic moments.[54] Coercivity (H_c) measures a material's resistance to demagnetization, defined as the reverse magnetic field strength required to reduce the magnetization to zero after saturation. High coercivity is essential for permanent magnets, as it ensures stability against external fields that could disrupt alignment.[55] Common examples include iron, which has a body-centered cubic crystal structure facilitating strong ferromagnetism; cobalt, with T_c around 1121°C and high saturation magnetization; and nickel, exhibiting T_c of about 358°C and used in alloys for enhanced properties.[7] These materials form the basis for most practical magnetic applications due to their robust ferromagnetic response.Paramagnetic and Diamagnetic Materials

Paramagnetic materials exhibit a weak attraction to external magnetic fields due to the presence of unpaired electrons in their atomic or molecular orbitals, which possess intrinsic magnetic moments that tend to align with the applied field.[56] However, thermal agitation at room temperature causes random orientations of these moments, limiting the overall alignment and resulting in a small, positive magnetic susceptibility that vanishes when the field is removed.[5] This behavior follows Curie's law, where the magnetization is inversely proportional to temperature.[57] A representative example is platinum, which has a volume magnetic susceptibility of approximately 2.28 × 10^{-4}, demonstrating its paramagnetic response.[58] Liquid oxygen provides a striking demonstration of paramagnetism, as its two unpaired electrons cause it to be attracted to the poles of a strong magnet when liquefied.[59] In contrast, diamagnetic materials produce a weak repulsion in response to an external magnetic field, arising from induced currents in atomic electron orbits that generate opposing magnetic moments, as dictated by Lenz's law.[60] This effect is universal to all materials, stemming from the orbital motion of electrons, but it is typically overshadowed by stronger paramagnetic or ferromagnetic responses in those substances.[57] The resulting magnetic susceptibility is small and negative. Bismuth exemplifies strong diamagnetism among elements, with a volume magnetic susceptibility of -1.66 × 10^{-4}, making it the most diamagnetic common metal.[61] Superconductors display perfect diamagnetism through the Meissner effect, where they expel all magnetic fields from their interior below the critical temperature, achieving a susceptibility of -1.[62] Diamagnetic properties enable applications in levitation demonstrations, such as suspending small objects like frogs or water droplets in strong magnetic fields using materials like graphite or bismuth to provide stabilizing repulsion.[63]Permanent Magnets

Principles of Operation

Permanent magnets operate by retaining a persistent magnetic field without the need for continuous external energy input, achieved through the alignment of microscopic magnetic domains within the material. In ferromagnetic materials, these domains consist of regions where atomic magnetic moments are spontaneously aligned, and during magnetization, an external field orients a significant fraction of these domains in a preferred direction, resulting in net magnetization. This alignment persists after the external field is removed due to the material's inherent resistance to demagnetization, enabling the magnet to produce a stable external field. A key property enabling this retention is remanence, denoted as , which is the magnetic flux density remaining in the material after the magnetizing field is reduced to zero. Measured in tesla (T), quantifies the intrinsic strength of the magnet's residual field and is determined from the hysteresis loop of the material. High remanence values indicate effective domain alignment and contribute to the magnet's ability to generate substantial flux in applications.[64] The behavior of permanent magnets under opposing fields is described by the demagnetization curve, which represents the second quadrant of the B-H hysteresis loop. This curve plots magnetic flux density against magnetic field strength (in amperes per meter), showing how the magnetization decreases as a reverse field is applied. It provides critical insight into the magnet's operating range, where points along the curve correspond to the field's response in practical circuits, with the knee of the curve indicating the onset of instability. The maximum energy product, , serves as a figure of merit for the magnet's stored magnetic energy density, calculated as the maximum value of the product on the demagnetization curve. Expressed in mega-gauss-oersteds (MGOe) in cgs units, it reflects the magnet's efficiency in converting material volume to useful magnetic work, with higher values allowing for more compact designs in devices like motors and sensors.[64] Maintaining the aligned domains against demagnetizing influences relies on stability factors such as shape anisotropy and crystal structure effects. Shape anisotropy arises from the geometry of the magnet, favoring magnetization along directions that minimize demagnetizing fields, such as the long axis in elongated forms, thereby enhancing resistance to reversal. Additionally, the crystal structure pins domain walls—boundaries between domains—through defects or grain boundaries, impeding their motion and preserving the overall alignment for sustained performance. Aligned domains are essential for achieving high and , as misalignment reduces net magnetization and overall efficacy.[65]Types and Compositions

Permanent magnets are categorized by their material composition and structure, which determine their magnetic properties such as remanence and coercivity. These include metallic alloys, ceramic ferrites, rare-earth compounds, polymer composites, nanostructured molecular systems, and emerging rare-earth-free alternatives. Each type leverages specific atomic arrangements to maintain magnetization after the removal of an external field, relying on the principle of remanence where domains align to resist demagnetization.[66] Metallic permanent magnets, such as Alnico alloys, consist primarily of aluminum (8–12%), nickel (15–26%), cobalt (5–24%), and iron (remainder), with minor additions of copper or titanium. Developed in the 1930s, Alnico magnets exhibit moderate magnetic strength due to their cast or sintered microstructures, which form elongated ferromagnetic domains during heat treatment and magnetic field alignment.[67][68] Ceramic or ferrite permanent magnets are based on strontium hexaferrite with the composition SrFe_{12}O_{19}, introduced in the 1950s. These oxide-based materials are highly corrosion-resistant owing to their stable ceramic structure, which features strong magnetocrystalline anisotropy from iron-oxygen bonds, enabling cost-effective production via sintering of powdered precursors.[69][70] Rare-earth permanent magnets include neodymium-iron-boron (Nd_{2}Fe_{14}B), discovered in 1984, which offers the highest commercial magnetic strength with remanence up to 1.4 T due to its tetragonal crystal structure enhancing exchange interactions between neodymium and iron atoms. Another variant, samarium-cobalt (SmCo_{5}), developed in the 1960s, provides superior temperature stability up to 350°C, attributed to the hexagonal structure's resistance to thermal disorder in samarium-cobalt intermetallic phases.[71][72] Composite permanent magnets, known as bonded magnets, incorporate magnetic powders—such as NdFeB, ferrite, or SmCo—mixed with polymer binders like nylon, epoxy, or polyphenylene sulfide (typically 2–10% by volume) to form flexible, isotropic structures. This composition allows for complex shapes via injection molding or extrusion, combining the powder's magnetic properties with the polymer's mechanical pliability for applications requiring non-brittle forms.[66][73] Nanostructured permanent magnets encompass single-molecule magnets (SMMs) and single-chain magnets (SCMs), where magnetic behavior arises from coordinated metal ions or organic radicals in molecular clusters or chains, respectively. SMMs, often based on transition metals like manganese or lanthanides, exhibit quantum tunneling of magnetization for potential quantum computing, while SCMs leverage one-dimensional spin chains for slow relaxation at the nanoscale.[74][75] Rare-earth-free permanent magnets include iron-nitride phases like α″-Fe_{16}N_{2}, advanced by Niron Magnetics in developments through 2025, which achieve high saturation magnetization from nitrogen-induced lattice distortion in iron without rare-earth elements. Additionally, compositions from Ames Laboratory in 2025, such as MnBi-based magnets, demonstrate coercivity that nearly doubles at 100°C, enabling stable performance in high-temperature environments.[76][77]Performance Factors

The performance of permanent magnets is primarily characterized by their magnetic strength, often quantified by the maximum energy product ((BH)_{\max}), which represents the maximum magnetic energy density a material can store. For neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, the highest commercially available energy product reaches 52 MGOe, enabling compact designs with high field strengths suitable for demanding applications.[78] This metric highlights NdFeB's superiority over other permanent magnet types, though achieving peak values requires optimized microstructures and alloy compositions. The shape of a permanent magnet significantly influences its effective performance through the demagnetization factor , a geometry-dependent parameter that accounts for internal field reductions due to the magnet's own magnetization. The effective magnetic field inside the material is given by , where is the applied field and is the magnetization; higher values (e.g., for thin or elongated shapes) lead to greater demagnetization and reduced overall efficiency.[79] Designers mitigate this by selecting geometries with low , such as long cylinders, to maximize operational stability. Temperature sensitivity is a critical limitation for permanent magnets, as thermal effects degrade magnetic properties. NdFeB magnets exhibit a remanence temperature coefficient of approximately -0.12%/°C, meaning their residual magnetization decreases linearly with rising temperature, potentially halving performance above 150°C without stabilization additives.[80] Maximum operating temperatures for standard NdFeB grades range from 80°C to 200°C, beyond which irreversible demagnetization occurs, necessitating alternatives like samarium-cobalt for high-heat environments.[81] Economic factors play a pivotal role in magnet selection and scalability. As of November 2025, NdFeB magnets cost around $60 per kg, driven by volatile rare earth prices, while ferrite magnets remain far more affordable at under $10 per kg, making them preferable for cost-sensitive, low-strength uses.[82] Supply chain vulnerabilities exacerbate NdFeB expenses, with over 90% of rare earths sourced from China, leading to export restrictions and price spikes amid geopolitical tensions. As of October 2025, China imposed new export controls on rare earth elements and magnets, further heightening these risks.[83][84] Corrosion resistance poses ongoing challenges, particularly for NdFeB magnets, which are prone to oxidation in humid or aggressive environments due to their reactive components. Protective coatings, such as nickel-copper-nickel plating or epoxy encapsulation, are essential to prevent degradation, extending service life but adding 5-10% to production costs.[85] Emerging rare-earth-free alternatives, like iron-nitride or manganese-based magnets, offer improved stability without coatings in some cases and can reduce costs through abundant raw materials.[86] The global permanent magnet market, valued at approximately $32 billion in 2025, is increasingly propelled by electric vehicle (EV) demand, where high-performance magnets enable efficient motors and account for over 40% of sector growth.[87] This expansion underscores the need for diversified supply chains to sustain innovation amid rising volumes projected to exceed 300,000 tons annually by 2030.Electromagnets

Construction and Principles