Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Microbiology

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

|

Microbiology (from Ancient Greek μῑκρος (mīkros) 'small' βίος (bíos) 'life' and -λογία (-logía) 'study of') is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular (single-celled), multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or acellular (lacking cells).[1][2] Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, protistology, mycology, immunology, and parasitology.

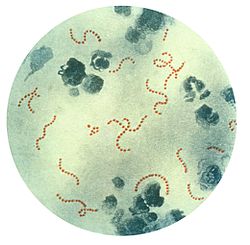

The organisms that constitute the microbial world are characterized as either prokaryotes or eukaryotes; Eukaryotic microorganisms possess membrane-bound organelles and include fungi and protists, whereas prokaryotic organisms are conventionally classified as lacking membrane-bound organelles and include Bacteria and Archaea.[3][4] Microbiologists traditionally relied on culture, staining, and microscopy for the isolation and identification of microorganisms. However, less than 1% of the microorganisms present in common environments can be cultured in isolation using current means.[5] With the emergence of biotechnology, Microbiologists currently rely on molecular biology tools such as DNA sequence-based identification, for example, the 16S rRNA gene sequence used for bacterial identification.

Viruses have been variably classified as organisms[6] because they have been considered either very simple microorganisms or very complex molecules. Prions, never considered microorganisms, have been investigated by virologists; however, as the clinical effects traced to them were originally presumed due to chronic viral infections, virologists took a search—discovering "infectious proteins".

The existence of microorganisms was predicted many centuries before they were first observed, for example by the Jains in India and by Marcus Terentius Varro in ancient Rome. The first recorded microscope observation was of the fruiting bodies of moulds, by Robert Hooke in 1666, but the Jesuit priest Athanasius Kircher was likely the first to see microbes, which he mentioned observing in milk and putrid material in 1658. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek is considered a father of microbiology as he observed and experimented with microscopic organisms in the 1670s, using simple microscopes of his design. Scientific microbiology developed in the 19th century through the work of Louis Pasteur and in medical microbiology Robert Koch.

History

[edit]

The existence of microorganisms was hypothesized for many centuries before their actual discovery. The existence of unseen microbiological life was postulated by Jainism which is based on Mahavira's teachings as early as 6th century BCE (599 BC - 527 BC).[7]: 24 Paul Dundas notes that Mahavira asserted the existence of unseen microbiological creatures living in earth, water, air and fire.[7]: 88 Jain scriptures describe nigodas which are sub-microscopic creatures living in large clusters and having a very short life, said to pervade every part of the universe, even in tissues of plants and flesh of animals.[8] The Roman Marcus Terentius Varro made references to microbes when he warned against locating a homestead in the vicinity of swamps "because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and thereby cause serious diseases."[9]

Persian scientists hypothesized the existence of microorganisms, such as Avicenna in his book The Canon of Medicine, Ibn Zuhr (also known as Avenzoar) who discovered scabies mites, and Al-Razi who gave the earliest known description of smallpox in his book The Virtuous Life (al-Hawi).[10] The tenth-century Taoist Baoshengjing describes "countless micro organic worms" which resemble vegetable seeds, which prompted Dutch sinologist Kristofer Schipper to claim that "the existence of harmful bacteria was known to the Chinese of the time."[11]

In 1546, Girolamo Fracastoro proposed that epidemic diseases were caused by transferable seedlike entities that could transmit infection by direct or indirect contact, or vehicle transmission.[12]

In 1676, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who lived most of his life in Delft, Netherlands, observed bacteria and other microorganisms using a single-lens microscope of his own design.[14][2] He is considered a father of microbiology as he used simple single-lensed microscopes of his own design.[14] While Van Leeuwenhoek is often cited as the first to observe microbes, Robert Hooke made his first recorded microscopic observation, of the fruiting bodies of moulds, in 1665.[15] It has, however, been suggested that a Jesuit priest called Athanasius Kircher was the first to observe microorganisms.[16]

Kircher was among the first to design magic lanterns for projection purposes, and so he was well acquainted with the properties of lenses.[16] He wrote "Concerning the wonderful structure of things in nature, investigated by Microscope" in 1646, stating "who would believe that vinegar and milk abound with an innumerable multitude of worms." He also noted that putrid material is full of innumerable creeping animalcules. He published his Scrutinium Pestis (Examination of the Plague) in 1658, stating correctly that the disease was caused by microbes, though what he saw was most likely red or white blood cells rather than the plague agent itself.[16]

The birth of bacteriology

[edit]

The field of bacteriology (later a subdiscipline of microbiology) was founded in the 19th century by Ferdinand Cohn, a botanist whose studies on algae and photosynthetic bacteria led him to describe several bacteria including Bacillus and Beggiatoa. Cohn was also the first to formulate a scheme for the taxonomic classification of bacteria, and to discover endospores.[17] Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch were contemporaries of Cohn, and are often considered to be the fathers of modern microbiology[16] and medical microbiology, respectively.[18] Pasteur is most famous for his series of experiments designed to disprove the then widely held theory of spontaneous generation, thereby solidifying microbiology's identity as a biological science.[19] One of his students, Adrien Certes, is considered the founder of marine microbiology.[20] Pasteur also designed methods for food preservation (pasteurization) and vaccines against several diseases such as anthrax, fowl cholera and rabies.[2] Koch is best known for his contributions to the germ theory of disease, proving that specific diseases were caused by specific pathogenic microorganisms. He developed a series of criteria that have become known as the Koch's postulates. Koch was one of the first scientists to focus on the isolation of bacteria in pure culture resulting in his description of several novel bacteria including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis.[2]

While Pasteur and Koch are often considered the founders of microbiology, their work did not accurately reflect the true diversity of the microbial world because of their exclusive focus on microorganisms having direct medical relevance. It was not until the late 19th century and the work of Martinus Beijerinck and Sergei Winogradsky that the true breadth of microbiology was revealed.[2] Beijerinck made two major contributions to microbiology: the discovery of viruses and the development of enrichment culture techniques.[21] While his work on the tobacco mosaic virus established the basic principles of virology, it was his development of enrichment culturing that had the most immediate impact on microbiology by allowing for the cultivation of a wide range of microbes with wildly different physiologies. Winogradsky was the first to develop the concept of chemolithotrophy and to thereby reveal the essential role played by microorganisms in geochemical processes.[22] He was responsible for the first isolation and description of both nitrifying and nitrogen-fixing bacteria.[2] French-Canadian microbiologist Felix d'Herelle co-discovered bacteriophages in 1917 and was one of the earliest applied microbiologists.[23]

Joseph Lister was the first to use phenol disinfectant on the open wounds of patients.[24]

Branches

[edit]

The branches of microbiology can be classified into applied sciences, or divided according to taxonomy, as is the case with bacteriology, mycology, protozoology, virology, phycology, and microbial ecology. There is considerable overlap between the specific branches of microbiology with each other and with other disciplines, and certain aspects of these branches can extend beyond the traditional scope of microbiology.[25][26] A pure research branch of microbiology is termed cellular microbiology.

Applications

[edit]While some people have fear of microbes due to the association of some microbes with various human diseases, many microbes are also responsible for numerous beneficial processes such as industrial fermentation (e.g. the production of alcohol, vinegar and dairy products) and antibiotic production. Scientists have also exploited their knowledge of microbes to produce biotechnologically important enzymes such as Taq polymerase,[27] reporter genes for use in other genetic systems and novel molecular biology techniques such as the yeast two-hybrid system.[28]

Bacteria can be used for the industrial production of amino acids. organic acids, vitamin, proteins, antibiotics and other commercially used metabolites which are produced by microorganisms. Corynebacterium glutamicum is one of the most important bacterial species with an annual production of more than two million tons of amino acids, mainly L-glutamate and L-lysine.[29] Since some bacteria have the ability to synthesize antibiotics, they are used for medicinal purposes, such as Streptomyces to make aminoglycoside antibiotics.[30]

A variety of biopolymers, such as polysaccharides, polyesters, and polyamides, are produced by microorganisms. Microorganisms are used for the biotechnological production of biopolymers with tailored properties suitable for high-value medical application such as tissue engineering and drug delivery. Microorganisms are for example used for the biosynthesis of xanthan, alginate, cellulose, cyanophycin, poly(gamma-glutamic acid), levan, hyaluronic acid, organic acids, oligosaccharides polysaccharide and polyhydroxyalkanoates.[31]

Microorganisms are beneficial for microbial biodegradation or bioremediation of domestic, agricultural and industrial wastes and subsurface pollution in soils, sediments and marine environments. The ability of each microorganism to degrade toxic waste depends on the nature of each contaminant. Since sites typically have multiple pollutant types, the most effective approach to microbial biodegradation is to use a mixture of bacterial and fungal species and strains, each specific to the biodegradation of one or more types of contaminants.[32]

Symbiotic microbial communities confer benefits to their human and animal hosts health including aiding digestion, producing beneficial vitamins and amino acids, and suppressing pathogenic microbes. Some benefit may be conferred by eating fermented foods, probiotics (bacteria potentially beneficial to the digestive system) or prebiotics (substances consumed to promote the growth of probiotic microorganisms).[33][34] The ways the microbiome influences human and animal health, as well as methods to influence the microbiome are active areas of research.[35]

Research has suggested that microorganisms could be useful in the treatment of cancer. Various strains of non-pathogenic clostridia can infiltrate and replicate within solid tumors. Clostridial vectors can be safely administered and their potential to deliver therapeutic proteins has been demonstrated in a variety of preclinical models.[36]

Some bacteria are used to study fundamental mechanisms. An example of model bacteria used to study motility[37] or the production of polysaccharides and development is Myxococcus xanthus.[38]

See also

[edit]- Professional organizations

- American Society for Microbiology

- Federation of European Microbiological Societies

- Society for Applied Microbiology

- Society for General Microbiology

- Journals

References

[edit]- ^ "Microbiology". Nature. Nature Portfolio (of Springer Nature). Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- ^ a b c d e f Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2006). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (13th ed.). Pearson Education. p. 1096. ISBN 978-0-321-73551-5.

- ^ Whitman WB (2015). Whitman WB, Rainey F, Kämpfer P, Trujillo M, Chun J, Devos P, Hedlund B, Dedysh S (eds.). Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. John Wiley and Sons. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.737.4970. doi:10.1002/9781118960608. ISBN 978-1-118-96060-8.

- ^ Pace NR (May 2006). "Time for a change". Nature. 441 (7091): 289. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..289P. doi:10.1038/441289a. PMID 16710401. S2CID 4431143.

- ^ Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH (March 1995). "Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation". Microbiological Reviews. 59 (1): 143–169. doi:10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. PMC 239358. PMID 7535888.

- ^ Rice G (2007-03-27). "Are Viruses Alive?". Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ a b Dundas P (2002). Hinnels J (ed.). The Jain. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26606-2.

- ^ Jaini P (1998). The Jaina Path of Purification. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 109. ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0.

- ^ Varro MT (1800). The three books of M. Terentius Varro concerning agriculture. Vol. 1. Charing Cross, London: At the University Press. p. xii.

- ^ "فى الحضارة الإسلامية - ديوان العرب" [Microbiology in Islam]. Diwanalarab.com (in Arabic). Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Huang, Shih-Shan Susan (2011). "Daoist Imagery of Body and Cosmos, Part 2: Body Worms and Internal Alchemy". Journal of Daoist Studies. 4 (1): 32–62. doi:10.1353/dao.2011.0001. ISSN 1941-5524. S2CID 57857037.

- ^ Fracastoro G (1930) [1546]. De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis [On Contagion and Contagious Diseases] (in Latin). Translated by Wright WC. New York: G.P. Putnam.

- ^ "RKI - Robert Koch - Robert Koch: One of the founders of microbiology".

- ^ a b Lane N (April 2015). "The unseen world: reflections on Leeuwenhoek (1677) 'Concerning little animals'". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 370 (1666) 20140344. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0344. PMC 4360124. PMID 25750239.

- ^ Gest H (2005). "The remarkable vision of Robert Hooke (1635-1703): first observer of the microbial world". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 48 (2): 266–272. doi:10.1353/pbm.2005.0053. PMID 15834198. S2CID 23998841.

- ^ a b c d Wainwright M (2003). An Alternative View of the Early History of Microbiology. Advances in Applied Microbiology. Vol. 52. pp. 333–55. doi:10.1016/S0065-2164(03)01013-X. ISBN 978-0-12-002654-8. PMID 12964250.

- ^ Drews G (1999). "Ferdinand Cohn, among the Founder of Microbiology". ASM News. 65 (8): 547.

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ Bordenave G (May 2003). "Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)". Microbes and Infection. 5 (6): 553–560. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00075-3. PMID 12758285.

- ^ Adler A, Dücker E (March 2018). "When Pasteurian Science Went to Sea: The Birth of Marine Microbiology". Journal of the History of Biology. 51 (1): 107–133. doi:10.1007/s10739-017-9477-8. PMID 28382585. S2CID 22211340.

- ^ Johnson J (2001) [1998]. "Martinus Willem Beijerinck". APSnet. American Phytopathological Society. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved May 2, 2010. Retrieved from Internet Archive January 12, 2014.

- ^ Paustian T, Roberts G (2009). "Beijerinck and Winogradsky Initiate the Field of Environmental Microbiology". Through the Microscope: A Look at All Things Small (3rd ed.). Textbook Consortia. § 1–14.

- ^ Keen EC (December 2012). "Felix d'Herelle and our microbial future". Future Microbiology. 7 (12): 1337–1339. doi:10.2217/fmb.12.115. PMID 23231482.

- ^ Lister BJ (August 2010). "The classic: On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. 1867". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 468 (8): 2012–2016. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1320-x. PMC 2895849. PMID 20361283.

- ^ "Branches of Microbiology". General MicroScience. 2017-01-13. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ^ Madigan MT, Martinko JM, Bender KS, Buckley DH, Stahl DA (2015). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (14th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-321-89739-8.

- ^ Gelfand DH (1989). "Taq DNA Polymerase". In Erlich HA (ed.). PCR Technology. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–22. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-20235-5_2. ISBN 978-1-349-20235-5. S2CID 100860897.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Uetz, Peter (December 2012). "Editorial for "The Yeast two-hybrid system"". Methods. 58 (4): 315–316. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.01.001. ISSN 1095-9130. PMID 23317557.

- ^ Burkovski A, ed. (2008). Corynebacteria: Genomics and Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-30-1. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ^ Fourmy D, Recht MI, Blanchard SC, Puglisi JD (November 1996). "Structure of the A site of Escherichia coli 16S ribosomal RNA complexed with an aminoglycoside antibiotic". Science. 274 (5291): 1367–1371. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1367F. doi:10.1126/science.274.5291.1367. PMID 8910275. S2CID 21602792.

- ^ Rehm BH, ed. (2008). Microbial Production of Biopolymers and Polymer Precursors: Applications and Perspectives. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-36-3. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ^ Diaz E, ed. (2008). Microbial Biodegradation: Genomics and Molecular Biology (1st ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-17-2. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ^ Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH (April 1999). "Probiotics and prebiotics: can regulating the activities of intestinal bacteria benefit health?". BMJ. 318 (7189): 999–1003. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7189.999. PMC 1115424. PMID 10195977.

- ^ Tannock GW, ed. (2005). Probiotics and Prebiotics: Scientific Aspects. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-01-1. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- ^ Wenner M (30 November 2007). "Humans Carry More Bacterial Cells than Human Ones". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ Mengesha A, Dubois L, Paesmans K, Wouters B, Lambin P, Theys J (2009). "Clostridia in Anti-tumor Therapy". In Brüggemann H, Gottschalk G (eds.). Clostridia: Molecular Biology in the Post-genomic Era. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-38-7.

- ^ Zusman DR, Scott AE, Yang Z, Kirby JR (November 2007). "Chemosensory pathways, motility and development in Myxococcus xanthus". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 5 (11): 862–872. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1770. PMID 17922045. S2CID 2340386.

- ^ Islam ST, Vergara Alvarez I, Saïdi F, Guiseppi A, Vinogradov E, Sharma G, et al. (June 2020). "Modulation of bacterial multicellularity via spatio-specific polysaccharide secretion". PLOS Biology. 18 (6) e3000728. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000728. PMC 7310880. PMID 32516311.

Further reading

[edit]- Kreft JU, Plugge CM, Grimm V, Prats C, Leveau JH, Banitz T, et al. (November 2013). "Mighty small: Observing and modeling individual microbes becomes big science". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (45): 18027–18028. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11018027K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317472110. PMC 3831448. PMID 24194530.

- Madigan MT, Martinko JM, Bender KS, Buckley DH, Stahl DA (2015-06-05). Brock Biology of Microorganisms, Global Edition. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-1-292-06831-2.

External links

[edit] Media related to Microbiology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Microbiology at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Microbiology at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Microbiology at Wikiquote- nature.com Latest Research, reviews and news on microbiology

- Microbes.info is a microbiology information portal containing a vast collection of resources including articles, news, frequently asked questions, and links pertaining to the field of microbiology.

- Microbiology on In Our Time at the BBC

- Immunology, Bacteriology, Virology, Parasitology, Mycology and Infectious Disease

- Annual Review of Microbiology Archived 2009-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

Microbiology

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Microbiology is the scientific study of microorganisms, which encompass a diverse array of entities too small to be seen with the naked eye without magnification. These include prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea, eukaryotic microorganisms like fungi, protozoa, and algae, as well as acellular infectious agents including viruses.[2] Cellular microorganisms are predominantly unicellular and range in size from about 0.2 to 10 micrometers, while viruses are smaller, typically 20–300 nanometers in diameter, distinguishing them from larger, multicellular organisms studied in macrobiology.[8][9][10] The scope of microbiology extends across multiple disciplines, examining the morphology, physiology, genetics, ecology, and evolution of these entities. This field explores how microorganisms structure themselves at the cellular level, their metabolic processes and growth requirements, genetic mechanisms including mutation and gene transfer, interactions within ecosystems, and adaptive changes over time.[11][12] Unlike macrobiology, which focuses on visible plants, animals, and fungi, microbiology delves into the invisible world that underpins biological processes at a microscopic scale.[13] Central to microbiology are principles highlighting the ubiquity of microorganisms, which inhabit virtually all environments on Earth, from air and soil to water and extreme conditions such as high temperatures, acidity, or salinity.[14][15] They play essential roles in nutrient cycling, such as nitrogen fixation and decomposition; cause diseases through pathogenesis; and form symbiotic relationships that benefit hosts, like mutualistic associations in plant roots.[16][17] These principles underscore the profound impact of microbes on global ecosystems and human health.Classification of Microorganisms

Microorganisms are classified primarily based on their cellular structure, genetic composition, and evolutionary relationships, with the three-domain system providing the foundational framework for cellular life. Proposed by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler, and Mark Wheelis, this system divides all cellular organisms into three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya, reflecting deep phylogenetic divergences revealed through ribosomal RNA sequencing. Bacteria and Archaea are prokaryotes, lacking a membrane-bound nucleus and typically featuring circular DNA in a nucleoid region, while Eukarya are eukaryotes, characterized by a true nucleus enclosing linear chromosomes and membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts.[18] Prokaryotic cell walls differ markedly: bacterial walls contain peptidoglycan, a polymer unique to that domain, whereas archaeal walls often consist of pseudopeptidoglycan or proteins like S-layers, and eukaryotic microbial walls may include chitin in fungi or cellulose in algae.[8] Within the Bacteria domain, classification often relies on morphological and staining properties, such as Gram staining, which differentiates Gram-positive bacteria (with thick peptidoglycan layers retaining crystal violet dye, appearing purple) from Gram-negative bacteria (with thin peptidoglycan and an outer lipopolysaccharide membrane, appearing pink after counterstaining).[19] Bacterial shapes include cocci (spherical, e.g., Staphylococcus aureus), bacilli (rod-shaped, e.g., Escherichia coli), and spirilla (spiral, e.g., Spirillum volutans), aiding in preliminary identification. Many archaea are extremophiles that thrive in harsh environments like hypersaline lakes or acidic hot springs; for instance, halophiles such as Haloarchaea accumulate high salt concentrations via compatible solutes, and thermophiles like Pyrococcus furiosus grow optimally above 100°C due to heat-stable enzymes.[20] Eukaryotic microorganisms encompass diverse groups. Fungi include unicellular yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which reproduce by budding and lack hyphae) and multicellular molds (e.g., Aspergillus species, forming filamentous hyphae with septa or aseptate structures). Protozoa are motile, heterotrophic unicellular eukaryotes classified by locomotion: amoebae (e.g., Entamoeba histolytica, using pseudopodia for movement and phagocytosis) and flagellates (e.g., Trypanosoma brucei, propelled by whip-like flagella and often parasitic).[21] Unicellular algae, photosynthetic eukaryotes, include diatoms (Bacillariophyta, with silica frustules) and green algae like Chlorella (Chlorophyta, storing starch and containing chlorophyll a and b).[21] Viruses, acellular entities, are classified separately using the Baltimore system, which groups them into seven classes based on nucleic acid type and replication mechanism. Developed by David Baltimore, this scheme distinguishes double-stranded DNA viruses (Group I, e.g., adenoviruses replicating in the nucleus), single-stranded DNA viruses (Group II, e.g., parvoviruses), double-stranded RNA viruses (Group III, e.g., reoviruses), positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses (Group IV, e.g., poliovirus directly translated by host ribosomes), negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses (Group V, e.g., influenza requiring RNA polymerase), single-stranded RNA reverse-transcribing viruses (Group VI, e.g., retroviruses like HIV using reverse transcriptase), and double-stranded DNA reverse-transcribing viruses (Group VII, e.g., hepatitis B). Microbial nomenclature follows the binomial system established by Carl Linnaeus, assigning each organism a genus and species epithet in italics (e.g., Escherichia coli for a Gram-negative bacillus). For bacteria, Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology serves as the authoritative reference, providing detailed taxonomic descriptions, phylogenetic data, and keys for identification based on phenotypic and genotypic traits.[22] Evolutionary relationships among microorganisms are elucidated through phylogenetic trees constructed from 16S rRNA gene sequences, a conserved molecular marker pioneered by Carl Woese, enabling the distinction of bacterial and archaeal lineages and revealing the tree of life. The endosymbiotic theory, advanced by Lynn Margulis, posits that eukaryotic organelles like mitochondria (derived from alphaproteobacteria) and chloroplasts (from cyanobacteria) originated from engulfed prokaryotes that evolved symbiotic relationships, supported by shared genetic and structural features such as circular DNA and double membranes.[23]History

Early Observations and Discoveries

Ancient civilizations demonstrated an early, albeit unconscious, engagement with microbial processes through fermentation. In ancient Egypt, around 1300–1500 BCE, bakers utilized yeast for leavened bread production, mixing dough with water and grains in pre-fermented mixtures that relied on natural microbial activity to rise and enhance texture.[24] Similarly, Sumerians and Babylonians, as early as 1800 BCE, harnessed fermentation to convert barley starch into sugar for beer production, a staple beverage documented in texts like the Hymn to Ninkasi, which outlines the brewing process involving mashing and straining.[25] These practices highlight humanity's inadvertent exploitation of microorganisms for food and drink preservation long before their existence was understood.[26] Associations between invisible agents and disease also emerged in antiquity. The Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460–377 BCE) rejected supernatural causes for illnesses, instead attributing epidemics, or pestilences, to "bad air" or miasma—poisonous vapors arising from decaying organic matter, identifiable by foul odors.[27] This miasma theory posited that corrupted environmental air infiltrated the body through pores, leading to disease, and influenced medical thought by emphasizing sanitation and environmental factors over divine intervention.[27] While not directly referencing microbes, these ideas laid preliminary groundwork for linking unseen environmental elements to health outcomes. The invention of the compound microscope in the late 16th century enabled direct visualization of microorganisms, marking a pivotal shift. Dutch draper and microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek refined single-lens microscopes in the 1670s, achieving magnifications up to 500 times, and became the first to observe and describe "animalcules"—tiny living creatures invisible to the naked eye.[6] In 1674, he examined pond water and identified protozoa, motile single-celled organisms darting through the sample, which he detailed in letters to the Royal Society.[6] In 1683, Leeuwenhoek examined scrapings from his own teeth, revealing swarms of even smaller, rod-shaped and spherical bacteria in dental plaque, which he described as vigorously moving "little animalcules" in his report to the Royal Society that year.[6] These observations provided the earliest documented evidence of bacteria and protozoa, fundamentally expanding perceptions of life's diversity.[6] Debates over spontaneous generation—the notion that life could arise from non-living matter—intensified with these discoveries. For centuries, it was widely believed that maggots emerged directly from decaying meat, exemplifying abiogenesis. In 1668, Italian physician Francesco Redi challenged this through controlled experiments: he placed meat in jars, some left open to the air (where flies laid eggs, producing maggots), others tightly sealed (showing no maggots), and a third set covered with gauze (preventing fly access but allowing air, again yielding no maggots).[28] Redi's work demonstrated that maggots developed from fly eggs, not spontaneous emergence, thus disproving abiogenesis for larger organisms and emphasizing the role of pre-existing life.[29] Extending these inquiries to microscopic scales, 18th-century experiments further contested spontaneous generation. In 1765, Italian priest and biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani boiled nutrient broth in flasks to kill potential organisms, then sealed them hermetically; no microbial growth occurred, even after prolonged incubation, while unsealed or inadequately boiled controls teemed with life.[28] Spallanzani concluded that boiling sterilized the broth and that sealing prevented contamination by airborne particles carrying life, refuting claims of spontaneous emergence in fluids.[30] Critics argued his methods excluded a "vital force" in air, but his rigorous approach strengthened empirical challenges to abiogenesis.[31] These foundational observations and experiments on microbial visibility and biogenesis set the stage for the eventual formulation of germ theory in the following century.Development of Key Concepts

The development of microbiology in the 19th century was profoundly shaped by the establishment of the germ theory of disease, which posited that specific microorganisms cause infectious diseases rather than arising spontaneously. Louis Pasteur's experiments in the 1860s provided critical evidence against spontaneous generation, using swan-necked flasks filled with nutrient broth that allowed air but trapped dust and microbes, demonstrating that microbial growth occurred only when the neck was broken.[32] These findings solidified the role of airborne microbes in fermentation and decay, laying the groundwork for germ theory. Additionally, Pasteur developed pasteurization in 1862, a heating process initially applied to wine and later to milk, which inhibited microbial spoilage without altering the product significantly.[33] Building on Pasteur's work, Robert Koch advanced microbiology through rigorous experimentation and methodological innovations in the late 19th century. In 1876, Koch isolated the anthrax bacillus (Bacillus anthracis) from infected cattle, using mouse inoculation to confirm its pathogenicity and demonstrating its spore-forming ability under microscopy.[34] He extended this approach in 1882 by identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the causative agent of tuberculosis, culturing it on solidified blood serum and staining it with methylene blue for visualization.[34] In 1883, during an outbreak in Egypt and India, Koch isolated Vibrio cholerae from cholera patients, linking it to waterborne transmission.[34] To systematize causal inference, Koch formulated his postulates in 1884, requiring that a pathogen be found in diseased but not healthy hosts, isolated and grown in pure culture, cause disease when inoculated into a healthy host, and be re-isolated from the infected host—criteria that became foundational for proving microbial etiology.[34] The birth of bacteriology as a distinct discipline owed much to Ferdinand Cohn's systematic classification efforts in the 1870s, where he organized bacteria into genera like Bacillus based on morphology, physiology, and life cycles, treating them as botanical entities.[35] Cohn's work facilitated the recognition of bacteria as a coherent group, influencing subsequent researchers. Complementing this, Koch's development of pure culture techniques in the early 1880s, using nutrient agar plates to isolate individual bacterial colonies, enabled precise study of microbial traits without contamination, revolutionizing experimental bacteriology.[34] Links to vaccination and immunology emerged as precursors to modern microbiology. Edward Jenner's 1796 demonstration that cowpox inoculation protected against smallpox established the principle of vaccination, using a milder related virus to confer immunity.[36] Pasteur extended this concept with his 1885 rabies vaccine, attenuating the virus through serial passage in rabbits and administering post-exposure inoculations, successfully treating a boy bitten by a rabid dog and marking a milestone in active immunization.[37] Early 20th-century advancements shifted focus toward non-bacterial pathogens and antimicrobial agents. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky discovered the tobacco mosaic agent while studying diseased plants, finding that filtered sap retained infectivity despite removing bacteria, indicating a submicroscopic "contagium vivum fluidum" that challenged bacterial exclusivity in disease causation.[38] This laid the groundwork for virology. Meanwhile, Alexander Fleming's 1928 observation of a mold (Penicillium notatum) inhibiting Staphylococcus growth on a contaminated plate led to the identification of penicillin as the first antibiotic, offering a targeted weapon against bacterial infections.[39] In the same year, Arthur T. Henrici (1889–1943) published his monograph "Morphologic Variation and the Rate of Growth of Bacteria," demonstrating that the growth of bacteria in artificial culture is governed by the same laws that affect the development of multicellular organisms; the cells exhibit an embryonic form during a period of rapid growth, a mature or differentiated form during a period of slow growth or rest, and a senescent form during the period of death. The bacterial genus Henriciella is named in his honor.[40]Techniques and Methods

Microscopy and Visualization

Light microscopy serves as the foundational technique for visualizing microorganisms, employing compound microscopes that achieve a resolution of approximately 0.2 μm, sufficient to observe bacterial cells and basic structures.[41] These instruments utilize visible light and a series of lenses to magnify specimens up to 1,000 times. Common variants include brightfield microscopy, which provides high-contrast images of stained samples against a bright background; darkfield microscopy, which illuminates specimens from the side to highlight edges and motility on a dark field; and phase-contrast microscopy, which enhances contrast in unstained, live cells by exploiting differences in refractive index, making it ideal for observing dynamic processes in bacteria without killing them.[42] Staining techniques are essential to improve visibility and differentiation in light microscopy, as many microorganisms are transparent. The Gram staining method, developed by Christian Gram in 1884, differentiates bacteria based on cell wall composition: Gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet dye due to their thick peptidoglycan layer, appearing purple, while Gram-negative bacteria, with thinner peptidoglycan and an outer membrane, decolorize and counterstain pink with safranin.[19] For specific pathogens like mycobacteria, acid-fast staining targets lipid-rich cell walls that resist decolorization by acid-alcohol, allowing visualization of Mycobacterium species (e.g., those causing tuberculosis) as red rods against a blue background using carbol fuchsin dye.[43] Electron microscopy provides far higher resolution for detailed ultrastructural analysis, overcoming the limitations of light wavelengths. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), pioneered in the 1930s by Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll, uses a beam of electrons transmitted through ultrathin sections to reveal internal cellular components, achieving resolutions down to subnanometer scales (approximately 0.1 nm) for imaging organelles, viruses, and bacterial inclusions.[44] In contrast, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) scans the surface with electrons to produce three-dimensional topographical images of microbial exteriors, such as cell wall textures or biofilms, at resolutions around 1-10 nm, though it requires conductive coating to prevent charging.[45] Fluorescence microscopy enables specific labeling and dynamic imaging by exciting fluorochromes—molecules that emit light at longer wavelengths upon illumination. Common fluorochromes include DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), which binds to DNA and fluoresces blue, allowing visualization of bacterial nucleoids and total cell counts in live or fixed samples.[46] Advanced implementations, such as confocal fluorescence microscopy, use a pinhole to eliminate out-of-focus light, enabling optical sectioning for three-dimensional reconstructions of microbial communities or intracellular processes.[47] Despite these advances, microscopy in microbiology faces key limitations, including artifacts from sample preparation—such as shrinkage or distortion during fixation, dehydration, or embedding—that can alter apparent structures.[48] Additionally, motile microorganisms often require immobilization techniques, like embedding in agar or chemical fixation, to prevent movement that blurs images during observation.[49]Cultivation and Identification

Cultivation of microorganisms involves growing them in controlled laboratory environments using specialized media to support their proliferation and study. Culture media provide essential nutrients, such as carbon, nitrogen, and minerals, tailored to the metabolic needs of different microbes. Nutrient agar and broth serve as general-purpose media, containing peptones, beef extract, and sodium chloride to support the growth of a wide range of non-fastidious bacteria.[50] Selective media, like MacConkey agar, inhibit the growth of Gram-positive bacteria through bile salts and crystal violet while allowing Gram-negative enteric bacteria to proliferate, facilitating isolation from mixed samples.[51] Differential media, such as blood agar, distinguish microbes based on their reactions; for instance, hemolytic patterns on blood agar reveal alpha, beta, or gamma hemolysis produced by bacteria like Streptococcus species.[52] Cultivation techniques vary by oxygen requirements and isolation needs. Aerobic incubation exposes cultures to atmospheric oxygen in standard incubators at 35–37°C to promote growth of oxygen-dependent microbes, while anaerobic incubation uses gas packs or chambers to exclude oxygen for strict anaerobes, which lack defenses against oxidative stress.[53] Enrichment cultures selectively amplify rare or slow-growing microbes by using media with specific substrates, such as sulfate for sulfate-reducing bacteria, allowing them to outcompete dominant populations over time.[54] Pure culture isolation, pioneered by Robert Koch in the 1880s using agar plates, employs streak plating to dilute a sample across quadrants of an agar plate, yielding isolated colonies from single cells for subsequent study.[55] Identification of cultivated microbes combines phenotypic, serological, and genotypic approaches to confirm taxonomy and characteristics. Biochemical tests assess enzymatic activities; for example, the catalase test detects the enzyme that breaks down hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen (positive for Staphylococcus), while the oxidase test identifies cytochrome c oxidase activity (positive for Pseudomonas).[56] Serological methods use antigen-antibody reactions, such as agglutination or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), to detect specific microbial surface antigens or antibodies in serum, aiding in pathogen confirmation like Salmonella serotyping.[57] Molecular techniques, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the 16S rRNA gene followed by sequencing, provide precise phylogenetic identification by comparing sequences to databases, revolutionizing bacterial taxonomy since its adoption in the 1990s.[58] A major challenge in cultivation is that over 99% of environmental prokaryotes remain unculturable under standard lab conditions due to unknown growth requirements or dormancy, limiting direct study to a tiny fraction of microbial diversity.[59] Metagenomics addresses this by sequencing total DNA from environmental samples, enabling functional and taxonomic analysis of uncultured communities without isolation, as demonstrated in soil and ocean microbiome projects.[60] Handling microorganisms, especially pathogens, requires strict safety protocols outlined in biosafety levels (BSL) by the CDC. BSL-1 suits low-risk agents like non-pathogenic E. coli, emphasizing standard microbiological practices without special containment. BSL-2 adds biosafety cabinets and personal protective equipment for moderate-risk microbes like Salmonella, protecting against splashes and aerosols. BSL-3 incorporates directional airflow and respirators for agents causing serious airborne diseases, such as tuberculosis. BSL-4, used for high-risk pathogens like Ebola, demands full-body positive-pressure suits and Class III cabinets in isolated facilities to prevent any exposure.[61]| Biosafety Level | Risk Group | Key Features | Example Agents |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSL-1 | Low individual/community risk | Standard practices; no special containment | Non-pathogenic E. coli |

| BSL-2 | Moderate individual risk, low community risk | Biosafety cabinets; PPE; access control | Hepatitis B virus, Salmonella |

| BSL-3 | High individual risk, aerosol transmission; low community risk | Directional airflow; respirators; double-door entry | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, SARS-CoV-2 |

| BSL-4 | High individual/community risk; aerosol; no treatment | Positive-pressure suits; Class III cabinets; airlocks | Ebola virus, Marburg virus |