Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Philhellenism

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Greek. (May 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Philhellenism ("the love of Greek culture") was an intellectual movement prominent mostly at the turn of the 19th century. It contributed to the sentiments that led Europeans such as Lord Byron, Charles Nicolas Fabvier and Richard Church to advocate for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire.

The later 19th-century European philhellenism was largely to be found among the Classicists. The study of it falls under Classical Reception Studies and is a continuation of the Classical tradition.

Antiquity

[edit]

In antiquity, the term philhellene ("the admirer of Greeks and everything Greek"), from the (Greek: φιλέλλην, from φίλος - philos, "friend", "lover" + Ἕλλην - Hellen, "Greek")[1] was used to describe both non-Greeks who were fond of ancient Greek culture and Greeks who patriotically upheld their culture. The Liddell-Scott Greek-English Lexicon defines 'philhellene' as "fond of the Hellenes, mostly of foreign princes, as Amasis; of Parthian kings[...]; also of Hellenic tyrants, as Jason of Pherae and generally of Hellenic (Greek) patriots.[1] According to Xenophon, an honorable Greek should also be a philhellene.[2]

Some examples:

- Evagoras of Cyprus[3] and Philip II were both called "philhellenes" by Isocrates[4]

- The early rulers of the Parthian Empire, starting with Mithridates I (r. 171–132 BC), used the title of philhellenes on their coins, which was a political act done in order to establish friendly relations with their Greek subjects.[5]

- Following the example of the Parthians, Tigranes adopted the title of Philhellene (friend of the Greeks). The layout of his capital Tigranocerta was an example of Greek architecture.

Roman philhellenes

[edit]The literate upper classes of Ancient Rome were increasingly Hellenized in their culture during the 3rd century BC.[6][7][8]

Among Romans the career of Titus Quinctius Flamininus (died 174 BC), who appeared at the Isthmian Games in Corinth in 196 BC and proclaimed the freedom of the Greek states, was fluent in Greek, stood out, according to Livy, as a great admirer of Greek culture. The Greeks hailed him as their liberator.[9] There were some Romans during the late Republic, who were distinctly anti-Greek, resenting the increasing influence of Greek culture on Roman life, an example being the Roman Censor, Cato the Elder and Cato the Younger, who lived during the "Greek invasion" of Rome but towards the later years of his life he eventually became a philhellene after his stay in Rhodes.[10]

The lyric poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus, often anglicized as Horace, was another philhellene. He is notable for his words, "Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit et artis intulit agresti Latio" (Conquered Greece took captive her savage conqueror and brought her arts into rustic Latium), meaning that after the conquest of Greece the defeated Greeks created a cultural hegemony over the Romans.[citation needed]

Horace's contemporary lyric poets, Virgil and Ovid, both produced magnum opuses (the Aeneid and the Metamorphoses, respectively) which were substantially founded upon Hellenic references and culture. Additionally, Virgil's Eclogues were inspired by Theocritus' earlier pastoral poetry in his idylls. The Aeneid, Virgil's story of Rome's founding myth, notably shares several similarities with Homer's earlier epics, particularly the Odyssey, one of which being both his epic and the Odyssey follow a demigod protagonist's military voyage after the Trojan War. It also was influenced by Homer's Iliad; for example, the ekphrasis of Achilles' divine shield from his mother, Thetis, was mirrored by the ekphrasis of Aeneas' divine shield from his mother, Venus.[11] Ovid's work was perhaps even more influenced by ancient Greek culture than Virgil; his Metamorphoses were inspired by the Greek epic tradition and metamorphosis poetry in the Hellenistic tradition, and its content was derived to a large extent from Greek myth and folklore, including the Trojan War. Ovid's treatment of Greek myths was so impactful for later Philhellenism, especially during the Renaissance, that the well-known versions of some myths are actually Ovid's versions (e.g. Echo and Narcissus). Soon after these writers, other Roman lyric poets such as Lucan (inspired by Greek epics with his Pharsalia) or Persius (heavily inspired by Horace with his Life) continued to exhibit strong interests and admirations for Greek literary, artistic, and religious culture.

Roman emperors known for their philhellenism include Nero, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius and Julian the Apostate.

Modern times

[edit]

In the period of political reaction and repression after the fall of Napoleon, when the liberal-minded, educated and prosperous middle and upper classes of European societies found the Romantic nationalism of 1789–1792 repressed by the restoration of absolute monarchy at home, the idea of the re-creation of a Greek state on the very territories that were sanctified by their view of Antiquity—which was reflected even in the furnishings of their own parlors and the contents of their bookcases—offered an ideal, set at a romantic distance. Under these conditions, the Greek uprising constituted a source of inspiration and expectations that could never actually be fulfilled, disappointing what Paul Cartledge called "the Victorian self-identification with the Glory that was Greece".[12] American higher education was fundamentally transformed by the rising admiration of and identification with ancient Greece in the 1830s and afterward.[13]

Another popular subject of interest in Greek culture at the turn of the 19th century was the shadowy Scythian philosopher Anacharsis, who lived in the 6th century BC. The new prominence of Anacharsis was sparked by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy's fanciful Travels of Anacharsis the Younger in Greece (1788), a learned imaginary travel journal, one of the first historical novels, which a modern scholar has called "the encyclopedia of the new cult of the antique" in the late 18th century. It had a high impact on the growth of philhellenism in France: the book went through many editions, was reprinted in the United States and was translated into German and other languages. It later inspired European sympathy for the Greek War of Independence and spawned sequels and imitations throughout the 19th century.

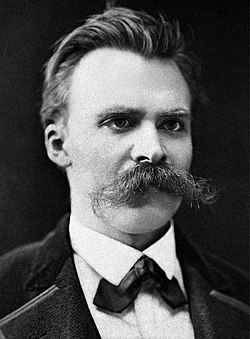

In German culture the first phase of philhellenism can be traced in the careers and writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, one of the inventors of art history, Friedrich August Wolf, who inaugurated modern Homeric scholarship with his Prolegomena ad Homerum (1795) and the enlightened bureaucrat Wilhelm von Humboldt. It was also in this context that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Hölderlin were to compose poetry and prose in the field of literature, elevating Hellenic themes in their works. One of the most renowned German philhellenes of the 19th century was Friedrich Nietzsche.[14] In the German states, the private obsession with ancient Greece took public forms, institutionalizing an elite philhellene ethos through the Gymnasium, to revitalize German education at home, and providing on two occasions high-minded philhellene German princes ignorant of modern-day Greek realities, to be Greek sovereigns.[16]

During the later 19th century the new studies of archaeology and anthropology began to offer a quite separate view of ancient Greece, which had previously been experienced second-hand only through Greek literature, Greek sculpture and architecture.[17] Twentieth-century heirs of the 19th-century view of an unchanging, immortal quality of "Greekness" are typified in J. C. Lawson's Modern Greek Folklore and Ancient Greek Religion (1910) or R. and E. Blum's The Dangerous Hour: The lore of crisis and mystery in rural Greece (1970).[18]

According to the Classicist Paul Cartledge, they "represent this ideological construction of Greekness as an essence, a Classicizing essence to be sure, impervious to such historic changes as that from paganism to Orthodox Christianity, or from subsistence peasant agriculture to more or less internationally market-driven capitalist farming."[18]

The Philhellenic movement led to the introduction of Classics or Classical studies as a key element in education, introduced in the Gymnasien in Prussia. In England the main proponent of Classics in schools was Thomas Arnold, headmaster at Rugby School.[citation needed]

Nikos Dimou's The Misfortune to be Greek[19] argues that the Philhellenes' expectation for the modern Greek people to live up to their ancestors' allegedly glorious past has always been a burden upon the Greeks themselves.[18] In particular, Western Philhellenism focused exclusively on the heritage of Classical Greece, while negating or rejecting the heritage of the Byzantine Empire and the Greek Orthodox Church, which for the Greek people are at least as important.

Art

[edit]Philhellenism also created a renewed interest in the artistic movement of Neoclassicism, which idealized fifth-century Classical Greek art and architecture,[20] very much at second hand, through the writings of the first generation of art historians, like Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.

The groundswell of the Philhellenic movement was result of two generations of intrepid artists and amateur treasure-seekers, from Stuart and Revett, who published their measured drawings as The Antiquities of Athens and culminating with the removal of sculptures from Aegina and the Parthenon (the Elgin Marbles), works that inspired the British Philhellenes, many of whom, however, deplored their removal.

Greek War of Independence and later

[edit]Many well-known philhellenes supported the Greek Independence Movement such as Shelley, Thomas Moore, Leigh Hunt, Cam Hobhouse, Walter Savage Landor and Jeremy Bentham.[21]

Some, notably Lord Byron, even took up arms to join the Greek revolutionaries. Many more financed the revolution or contributed through their artistic work.

Throughout the 19th century, philhellenes continued to support Greece politically and militarily. For example, Ricciotti Garibaldi led a volunteer expedition (Garibaldini) in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897.[22] A group of Garibaldini, headed by the Greek poet Lorentzos Mavilis, fought also with the Greek side during the Balkan Wars.

-

Depiction of Philhellenes in Greece in 1822

-

List of philhellenes who contributed during the Greek War of Independence (National Historical Museum). The first two columns from the left are the names of those having died.

-

Louis Dupré's depiction of Greek irregulars hoisting the flag at Salona

-

Panagiotis Kephalas plants the flag of liberty upon the walls of Tripolizza (Siege of Tripolitsa)" by Peter von Hess

-

A statue of Lord Byron in Athens

Notable 20th- and 21st-century philhellenes

[edit]- Albert Einstein, a German-born theoretical physicist widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest physicists of all time[23][24]

- Stephen Fry, English actor and writer[25]

- Giuseppe Garibaldi II, Italian soldier and revolutionary, grandson of Giuseppe Garibaldi and son of Ricciotti Garibaldi[22]

- Ricciotti Garibaldi, Italian soldier, son of Giuseppe Garibaldi[22]

- David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[26]

- Matthias Laurenz Gräff, austrian-greek painter, historian and politician (representative of the austrian governing party NEOS for Greece and whole Cyprus)[27][28][29]

- Boris Johnson, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom[30]

- Dilys Powell, film critic, author of several books about Greece, and president of the Classical Association 1966–1967

- Gough Whitlam, 21st Prime Minister of Australia[31]

- Christopher Hitchens, British-American author and journalist[32]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "φιλ-έλλην". A Greek-English Lexicon. Tufts University. Archived from the original on 2021-09-17. Retrieved 2021-09-17 – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ "Xenophon "Agesilaus" (7.4)". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- ^ "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, page 54 (V. 2)". Archived from the original on 2005-12-31. Retrieved 2006-03-06.

- ^ "Search Tools". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Dąbrowa 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Balsdon, J. P. V. D. (1979). Romans and Aliens. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd. pp. 30–58. ISBN 0715610430.

- ^ A. Momigliano, 1975. Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenization.

- ^ A. Wardman, 1976. Rome's debt to Greece.

- ^ A modern assessment is E. Badian, 1970. Titus Quinctius Flamininus: Philhellenism and Realpolitik0

- ^ "Plutarch • Life of Cato the Younger". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-08.

- ^ Kotkin, Joshua (2001). "Shields of Contradiction and Direction: Ekphrasis in the Iliad and the Aeneid" (PDF). The McGill Journal of Classical Studies. 1: 11–16.

- ^ Cartledge

- ^ Winterer, Caroline (2002). The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780-1910. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ a b Whitling, Frederick (2009). "Memory, history and the classical tradition". European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire. 16 (2): 235–253. doi:10.1080/13507480902767644. ISSN 1350-7486. S2CID 144461534.

- ^ Jaspers, Karl (1997-10-24). Nietzsche: An Introduction to the Understanding of His Philosophical Activity. JHU Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-8018-5779-9.

- ^ The history of pedagogically conservative philhellenism in German high academic culture has been examined in Suzanne L. Marchand, Down from Olympus: Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750–1970 (Princeton University Press, 1996); she begins with Winckelmann, Wolf and von Humboldt.

- ^ S. L. Marchand, 1992. Archaeology and Cultural Politics in Germany, 1800–1965: The Decline of Philhellenism (University of Chicago).

- ^ a b c Cartledge, Paul. "The Greeks and Anthropology." Anthropology Today, vol. 10, no. 3, 1994, pp. 3–6. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2783476. Accessed 9 June 2023.

- ^ Η δυστυχία του να είσαι Έλληνας, 1975.

- ^ It often selected for its favoured models third- and second-century sculptures that were actually Hellenistic in origin, and appreciated through the lens of Roman copies: see Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Antique Sculpture 1500–1900 (1981).

- ^ Roessel, David (2001-11-29). In Byron's Shadow: Modern Greece in the English and American Imagination. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198032908.

- ^ a b c Gilles Pécout, "Philhellenism in Italy: political friendship and the Italian volunteers in the Mediterranean in the nineteenth century", Journal of Modern Italian Studies 9:4:405–427 (2004) doi:10.1080/1354571042000296380

- ^ Tucci, Nicolo (15 November 1947). "The Great Foreigner". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 2021-01-01.

- ^ "Classics" (PDF). Stanford University.

- ^ Stephen Fry [@stephenfry] (April 21, 2021). "Truly, one of the great honours of my life. With thanks to the Ambassador, to President Sakellaropoulou and to the people of Greece" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Stavridis, Stavros T. (2019-07-09). "Hail, Lloyd George". The National Herald. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2021-08-13.

- ^ POETS Radio. Irene Gavala, Exclusive interview | Matthias Laurenz Graeff | Ζωγραφίζοντας., 2018

- ^ Matthias Laurenz Gräff, NEOS Repräsentant für Griechenland im Interview – Hephaestus Wien

- ^ NEOS International, Representative Matthias Laurenz Gräff

- ^ "Will Boris Johnson right our colonial wrongs and return the Elgin Marbles? Don't make me laugh". Independent. 13 November 2019.

- ^ "Former Australian MP, and noted philhellene Gough Whitlam passes". The TOC. 2014-10-21. Archived from the original on 2020-07-04. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ "Philhellene Writer Christopher Hitchens Passes Away". 20 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

References

[edit]- Paul Cartledge, Clare College Cambridge, "The Greeks and Anthropology" Archived 2006-10-22 at the Wayback Machine in Classics Ireland 2 (Dublin 1995)

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2012). "The Arsacid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–432. ISBN 978-0-19-987575-7. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

Further reading

[edit]- Thomas Cahill, Sailing the Wine-Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter (Nan A. Talese, 2003)

- Stella Ghervas, « Le philhellénisme d'inspiration conservatrice en Europe et en Russie », in Peuples, Etats et nations dans le Sud-Est de l'Europe, (Bucarest, Ed. Anima, 2004.)

- Stella Ghervas, « Le philhellénisme russe : union d'amour ou d'intérêt? », in Regards sur le philhellénisme, (Genève, Mission permanente de la Grèce auprès de l'ONU, 2008).

- Stella Ghervas, Réinventer la tradition. Alexandre Stourdza et l'Europe de la Sainte-Alliance (Paris, Honoré Champion, 2008). ISBN 978-2-7453-1669-1

- Konstantinou, Evangelos: Graecomania and Philhellenism, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2010, retrieved: December 17, 2012.

- Emile Malakis, French travellers in Greece (1770–1820): An early phase of French Philhellenism

- Suzanne L. Marchand, 1996. Down from Olympus : Archaeology and Philhellenism in Germany, 1750–1970

- M. Byron Raizis, 1971. American poets and the Greek revolution, 1821–1828;: A study in Byronic philhellenism (Institute of Balkan Studies)

- Terence J. B Spencer, 1973. Fair Greece! Sad relic: Literary philhellenism from Shakespeare to Byron

- Caroline Winterer, 2002. The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910. Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

[edit]Philhellenism

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Origins

Etymology and Conceptual Framework

The term philhellenism originates from the Ancient Greek compound φιλέλλην (philéllēn), formed by φίλος (phílos, denoting "loving," "dear," or "friend") and Ἕλλην (Hellḗn, referring to a Greek person or the collective Hellenes).[2] [10] This etymology yields a literal meaning of "lover of Greeks" or "friend of the Greeks," with the English noun philhellenism first attested in 1830 to describe affinity for Greek causes, though the root concept predates this by centuries in classical usage.[11] In antiquity, philhellene applied primarily to non-Greeks exhibiting fondness for Hellenic culture, customs, or alliances, as evidenced by its application to figures like Macedonian king Alexander I (r. 498–454 BCE), whom Herodotus described as proving his philhellenism through aid to Greeks against Persian incursions at the Olympic Games of 498 BCE.[3] Conceptually, philhellenism frames a non-native appreciation and emulation of Greek intellectual, artistic, and civic traditions, often driven by recognition of their causal role in advancing rational inquiry, aesthetic innovation, and self-governance.[12] This admiration historically manifested in cultural borrowing—such as Roman elites adopting Greek philosophy and rhetoric—or political support, where philhellenes positioned Greek models as exemplars of freedom and individual agency against autocratic foes.[13] Unlike mere aesthetic Hellenophilia, philhellenism implies active endorsement, including material or ideological aid, rooted in empirical perceptions of Greek achievements like the democratic experiments of 5th-century Athens or Hellenistic cosmopolitanism under Alexander the Great's successors.[14] Its framework thus privileges causal realism: Greek cultural exports succeeded through superior adaptability and intellectual rigor, attracting outsiders without coercive imposition, a dynamic observable from Persian satraps' defections to Roman paideia integration.[12]Distinction from Hellenophilia and Related Terms

Philhellenism specifically refers to an admiration for Greek culture, people, and language that often translates into active political or material support for Greek causes, most prominently exemplified by the international movement aiding Greece's independence from the Ottoman Empire during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), in which over 1,000 foreign volunteers participated, including figures like Lord Byron who died in 1824 at Missolonghi. This term, rooted in ancient usage for non-Greeks favoring Hellenic interests—such as Roman elites adopting Greek customs in the 2nd century BCE—gained its modern connotation through Enlightenment-era advocacy that framed Greek liberation as a restoration of classical liberty, influencing diplomatic pressures on European powers leading to the 1827 Treaty of London.[15][5] Hellenophilia, by contrast, encompasses a broader, more passive affinity for Greek heritage, encompassing scholarly, artistic, or personal enthusiasm for ancient philosophy, literature, and science without requiring advocacy or intervention in contemporary Greek affairs; for instance, 19th-century German classicists like Johann Joachim Winckelmann promoted Greek aesthetics as ideals of beauty, influencing neoclassical art movements across Europe from the 1750s onward, yet without direct involvement in political struggles. The term, less historically anchored than philhellenism, appears in mid-20th-century discourse to critique overemphasis on Greek contributions to fields like mathematics and astronomy, sometimes implying a bias that undervalues parallel developments in non-Western civilizations, as argued in analyses of historiography from the 1990s. While dictionaries occasionally list the terms as synonyms, philhellenism's activist legacy distinguishes it, particularly in contexts where cultural appreciation did not extend to risking life or fortune for Greek sovereignty.[16][17] Related concepts include Hellenism, which denotes the dissemination and dominance of Greek culture in the Hellenistic period following Alexander the Great's conquests (336–323 BCE), affecting over 20 successor kingdoms and blending with local traditions, rather than external admiration; and Graecophilia, an older synonym for cultural fondness akin to hellenophilia but tied to Renaissance recoveries of Greek texts, such as the 1453 fall of Constantinople prompting Byzantine scholars to bring manuscripts to Italy. Terms like hellenomania critique excessive or uncritical idealization, as in Romantic exaggerations of ancient Greece's purity, while opposites such as mishellenism describe anti-Greek sentiments, evident in Ottoman-era portrayals of Greeks as rebellious subjects unfit for autonomy. These distinctions underscore philhellenism's unique blend of cultural reverence and pragmatic solidarity, grounded in verifiable historical actions rather than abstract sentiment.[12]Philhellenism in Antiquity

Early Non-Greek Admirers

The earliest documented instances of non-Greek rulers explicitly identifying as philhellenes occurred among the Arsacid kings of Parthia, an Iranian nomadic confederation that established an empire in the 3rd century BCE following the decline of Seleucid control in the region.[18] These rulers, originating from the Parni tribe east of the Caspian Sea, encountered and incorporated elements of Greek culture through conquests of Hellenistic settlements in Mesopotamia and Iran.[19] Mithridates I (r. 171–138 BCE), the fourth Arsacid king, exemplified this admiration by adopting the epithet Philhellene ("lover of Greeks") on his coinage, particularly in regions like Margiana, to foster loyalty among Greek-speaking subjects.[20] His military campaigns captured major Hellenistic centers such as Seleucia on the Tigris in 141 BCE, where he integrated local Greek elites rather than suppressing them, blending Parthian governance with Hellenistic administrative practices.[18] This policy reflected a pragmatic appreciation for Greek urban organization, art, and coinage standards, evident in Parthian drachms mimicking Seleucid designs while featuring Arsacid iconography.[21] Subsequent early Arsacid rulers continued this philhellenism to legitimize their rule over diverse populations, employing Greek script on inscriptions and patronizing Hellenistic-style architecture in cities like Nisa.[22] Despite their Iranian heritage and Zoroastrian traditions, these kings' adoption of Greek cultural markers served to stabilize conquests in former Seleucid territories, marking a distinct non-Greek engagement with Hellenism distinct from the Roman variant.[23] This approach, however, sometimes clashed with Parthian nobility's preferences for nomadic traditions, highlighting the strategic rather than ideological nature of their admiration.[24]Roman Imperial Philhellenism

Roman imperial philhellenism built upon the Republic's cultural assimilation of Greece after the conquest of 146 BC, with emperors actively promoting Hellenic traditions through patronage, policy, and personal affinity. This era saw the empire's elite embracing Greek language, philosophy, literature, and arts, as Roman children were often educated by Greek tutors and the upper classes composed works in Greek.[25] Emperors adopted Greek gods by syncretism, renaming Zeus as Jupiter while incorporating Hellenistic mythology into state religion and iconography.[25] Nero (r. 54–68 AD) demonstrated philhellenism by traveling to Greece in 66 AD, participating in musical and athletic contests, and proclaiming the "freedom" of Achaia at the Isthmian Games in Corinth on November 28, 66 AD, which exempted the province from taxes but retained Roman administrative control as a gesture of cultural favor.[26] This act, motivated by Nero's self-identification as a performer in Greek festivals, underscored his admiration for Hellenic artistic and civic ideals despite underlying political pragmatism.[27] Hadrian (r. 117–138 AD) epitomized imperial philhellenism through his philhellenic policies and architectural legacy in Greece. In 131/132 AD, he founded the Panhellenion, a league of select Greek cities (initially around 33 members, expanding to over 50) headquartered in Athens, which organized quadrennial sacrifices to Zeus Olympios, Panhellenic games, and cultural exchanges to evoke classical unity.[28] Hadrian visited Athens thrice, completing the Temple of Olympian Zeus in 131 AD after six centuries of construction, erecting the Arch of Hadrian, and funding aqueducts, libraries, and stadium renovations, thereby elevating Athens as a cultural capital.[29] Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 AD), influenced by Stoicism—a philosophy rooted in Greek thinkers like Epictetus—wrote his personal reflections, the Meditations, entirely in Koine Greek during military campaigns, reflecting deep engagement with Hellenic ethical and cosmological ideas.[30] In the 4th century, Julian (r. 361–363 AD) pursued a revival of Hellenic paganism, authoring works like Against the Galileans to defend Greek philosophy and polytheism against Christianity, while reforming temples and promoting Neoplatonism as imperial ideology.[31] These efforts highlight philhellenism's persistence amid the empire's religious shifts, though Julian's short reign limited lasting impact.Medieval and Early Modern Contexts

Byzantine Self-Perception and External Views

The inhabitants of the Byzantine Empire predominantly identified as Romaioi (Romans), emphasizing their continuity with the Roman imperial tradition rather than ancient Hellenic paganism, a self-perception rooted in the empire's foundation by Constantine I in 330 CE and reinforced through legal, administrative, and religious structures.[32] This Roman identity persisted across centuries, with terms like Hellenes largely avoided until the late Byzantine period due to their association with pre-Christian polytheism, as evidenced in chronicles and theological texts that prioritized Orthodox Christian universality over ethnic Hellenism.[33] However, Byzantine elites preserved and engaged with classical Greek literature through paideia (education), fostering a cultural Hellenism that informed rhetoric, philosophy, and historiography without overt self-identification as such until the Palaiologan era (1261–1453), when scholars like Manuel Chrysoloras began reclaiming Hellene to denote linguistic and intellectual descent from antiquity amid territorial losses.[34] Externally, Latin Westerners increasingly perceived Byzantines as Graeci (Greeks) from the 11th century onward, distinguishing them from "true" Romans and often portraying them with stereotypes of effeminacy, deceit, or theological deviation, as seen in Crusader accounts post-1204 sack of Constantinople that highlighted cultural divergences like Byzantine adherence to Greek rites over Latin customs.[35] Islamic chroniclers, such as those under the Abbasid caliphate, referred to Byzantines as Rum (Romans), acknowledging their imperial legacy while noting Greek linguistic dominance, but without admiration for Hellenic classics, viewing them instead through a lens of rivalry and shared Abrahamic scriptural traditions.[36] This external framing as "Greeks" by Europeans laid groundwork for later philhellenic idealization of Byzantine heirs as cultural repositories, though contemporary medieval views prioritized geopolitical and religious antagonism over classical heritage appreciation.[37]Renaissance Revival and Humanist Philhellenism

The revival of interest in ancient Greek culture during the Renaissance began in the late 14th century, as Italian humanists sought direct access to Greek texts beyond Latin translations and medieval intermediaries. In 1397, Coluccio Salutati, chancellor of Florence, invited the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras to teach Greek at the Studium Florentinum, marking the first formal instruction in the language in Western Europe.[38] Chrysoloras, a diplomat and philologist, authored the Erotemata, a foundational Greek grammar that facilitated learning among Latin scholars, and emphasized the superiority of Greek literature for eloquence and philosophy.[39] This initiative fostered early philhellenic sentiments, with humanists viewing ancient Greek works—such as those of Homer, Plato, and Demosthenes—as models of rhetorical and ethical excellence, contrasting them with scholastic reliance on Aristotle via Arabic sources.[40] The Council of Florence in 1438–1439 accelerated this trend, as Byzantine delegates, including Georgios Gemistos Plethon, engaged Western audiences with Platonic philosophy amid efforts to reconcile Eastern and Western churches. Plethon's comparative lectures on Plato and Aristotle, delivered to figures like Cosimo de' Medici, critiqued Aristotelian dominance and advocated a return to Platonic idealism, inspiring the founding of the Platonic Academy in Florence under Marsilio Ficino by 1462.[41] Plethon's vision of a Hellenic revival, blending pagan philosophy with Christian elements, appealed to humanists disillusioned with medieval theology, positioning ancient Greece as a cultural progenitor of intellectual freedom and civic humanism.[42] Basilios Bessarion, another council participant who later converted to Catholicism, amassed over 600 Greek manuscripts and donated them to Venice in 1468, establishing a library that preserved and disseminated Hellenistic texts.[43] The fall of Constantinople in 1453 prompted a larger exodus of Greek scholars to Italy, intensifying philhellenic humanism; figures like John Argyropoulos lectured on Aristotle and Plato in Florence from 1456, training a generation including Angelo Poliziano.[44] Humanists such as Leonardo Bruni translated Greek historians like Xenophon and Procopius, integrating Hellenic ideals of republicanism and oratory into Italian political thought, while viewing Byzantine Greeks as custodians of authentic classical heritage.[45] This era's philhellenism was pragmatic rather than romanticized, driven by textual recovery and linguistic competence, yet it elevated ancient Greece as a benchmark for moral and intellectual renewal, influencing art, education, and philosophy without idealizing contemporary Greeks.[46]Enlightenment and Neoclassical Foundations

Intellectual and Philosophical Underpinnings

The Enlightenment's intellectual revival of classical antiquity positioned ancient Greece as a foundational model for rational inquiry, republican governance, and aesthetic perfection, laying philosophical groundwork for philhellenism by contrasting Greek achievements with medieval decline and Oriental despotism. Thinkers drew on Greek philosophy—particularly Socrates' embodiment of reason, virtue, and critical examination of authority—as a counter to religious dogma, viewing it as an archetype for human emancipation through knowledge.[47] Montesquieu, in The Spirit of the Laws (1748), analyzed Greek republics like Athens as virtue-sustaining entities limited by small territories and communal spirit, crediting them with originating democratic forms while noting their vulnerability to ambition and expansion.[48] Voltaire echoed this by emulating Greek tragedians in his own plays, such as Oedipe (1718), and praising ancient Greek wit for challenging superstition, though he critiqued their historical narratives as laced with myth.[49] These analyses framed Greece not merely as historical artifact but as causal exemplar of liberty emerging from civic virtue and intellectual freedom, influencing later views of modern Greeks as potential restorers of that legacy. Aesthetic philosophy further entrenched philhellenism through Johann Joachim Winckelmann's History of the Art of Antiquity (1764), which elevated Greek sculpture over Roman copies by attributing to it "noble simplicity and calm grandeur"—an ideal born of freedom, climate, and harmonious proportion rather than imperial excess.[50] Winckelmann argued Greek art reflected a unified cultural evolution from primitive to perfected forms, embodying ethical and physical beauty as products of democratic liberty, thus providing a metaphysical rationale for emulating Greece in modern ethics and aesthetics.[51] This Neoclassical paradigm, rooted in Enlightenment empiricism, rejected Baroque excess for Greek restraint, positing art as moral instruction and Greece as the empirical peak of human capability, untainted by later corruptions.[52] Such underpinnings emphasized causal links between Greek political freedom and cultural excellence, fostering a philosophical narrative that modern decline stemmed from abandoning classical principles—a view that propelled philhellenism toward active intervention by portraying Ottoman rule as antithetical to rational progress.[53] Critics like Edward Gibbon extended this by tracing Europe's heritage to Greco-Roman antiquity, reinforcing Greece's role as secular progenitor of Enlightenment values over Christian interruption.[52] This framework, while idealizing Greece empirically through texts and artifacts, overlooked internal Greek divisions and slavery, prioritizing first-principles admiration for its rational innovations.Artistic and Architectural Expressions

Johann Joachim Winckelmann's Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (1764) encapsulated philhellenic admiration by proclaiming ancient Greek art as the zenith of human achievement, characterized by "noble simplicity and calm grandeur," and advocated its imitation to revive modern aesthetics from Baroque excesses.[54] This treatise redirected artistic focus from Roman to Greek exemplars, influencing sculptors and painters to prioritize idealized human forms, contrapposto poses, and mythological subjects drawn from Hellenic sources, as seen in early neoclassical works emphasizing harmony and restraint over ornamentation.[55] Empirical documentation amplified these ideals through James Stuart and Nicholas Revett's The Antiquities of Athens (1762), the first precise survey of classical Greek architecture, featuring measured drawings of the Parthenon and other monuments that enabled faithful replication of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders.[56] This publication, sponsored by the Society of Dilettanti, fueled architectural philhellenism by providing architects with authentic Greek proportions and details, distinct from Roman adaptations via Vitruvius.[57] Notable expressions included the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin (designed 1788–1791 by Carl Gotthard Langhans), explicitly modeled on the Athens Propylaea to evoke democratic virtues, and British structures by "Athenian" Stuart, such as the Temple of Piety at Gunnersbury Park (c. 1760s) and restorations incorporating Greek motifs.[58] These designs reflected philhellenic aspirations for public edifices symbolizing enlightenment rationality and civic order, with symmetrical facades, pediments, and colonnades mirroring temple forms to honor Greek contributions to philosophy and governance.[59]Philhellenism in the 19th Century

Prelude to the Greek War of Independence

The intellectual roots of 19th-century philhellenism, which fueled European sympathy for Greek independence, trace to the Enlightenment's revival of classical antiquity, particularly through neoclassicism's emphasis on ancient Greek ideals of liberty, democracy, and aesthetics as models for modern society. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, often credited as a foundational figure, argued in his 1755 essay Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke that Greek art represented the highest form of beauty and nobility, superior to Roman imitations, thereby igniting a pan-European fascination with Hellenic culture that extended beyond scholarship to political aspirations.[60] His comprehensive Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (1764) further systematized this view, portraying Greece as the origin of civilized values and inspiring collectors, artists, and travelers to seek direct engagement with its legacy, despite the Ottoman overlay.[4] This neoclassical framework, disseminated via academies and publications across Germany, France, and Britain, began decoupling admiration for ancient achievements from disdain for contemporary "degeneracy," gradually framing modern Greeks as heirs deserving restoration. By the early 19th century, Romanticism infused philhellenism with nationalist fervor and emotional identification, linking ancient heroism to the plight of Ottoman-subjugated Greeks and aligning their cause with post-Napoleonic liberation movements. British poet Lord Byron's travels through Greece in 1809–1810, amid ruins like those at Athens and Missolonghi, profoundly shaped this shift; his Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (published in two cantos, 1812 and 1816) vividly contrasted classical splendor with current desolation under Turkish rule, evoking widespread lament for Greece's "fallen" state and priming readers for revolutionary advocacy.[60] Similarly, Percy Bysshe Shelley's Hellas (1822, conceived pre-war) mythologized Greek resurgence as a universal triumph of freedom, drawing on Aeschylus and Pindar to bridge antiquity and modernity.[4] European travel literature, including accounts from the extended Grand Tour, amplified these sentiments by documenting Greek resilience amid oppression—such as in Edward Dodwell's A Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece (1819)—fostering a narrative of cultural continuity that resonated with liberal elites.[61] These currents converged with practical precursors to revolt, including the secret Filiki Etaireia (Society of Friends), founded on September 14, 1814, in Odessa by Greek merchants and intellectuals like Nikolaos Skoufas, aiming to orchestrate independence through clandestine networks spanning Europe and the diaspora.[60] Though primarily Greek-led, the society's appeals drew tacit philhellenic encouragement from sympathetic Western contacts, building on earlier failed uprisings like the Orlov Revolt (1770–1771), which had publicized Greek aspirations during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). By 1821, this intellectual and organizational prelude had cultivated sufficient public opinion in Protestant and Catholic Europe—particularly in Germany, Britain, and France—for the revolution's outbreak on March 25, 1821, in the Danubian Principalities and Peloponnese to elicit immediate, if unofficial, backing, manifesting in funds, volunteers, and diplomatic pressure.[4] Philhellenism thus transitioned from aesthetic reverence to causal support, viewing Greek liberation as a moral imperative to reclaim Europe's "cradle" from "barbarism," though tempered by realistic assessments of modern Greeks' martial disorganization.[60]Support During the War: Figures, Aid, and Motivations

Prominent British poet Lord George Gordon Byron emerged as a leading philhellene figure, arriving in Cephalonia on August 3, 1823, aboard the ship Hercules, where he organized military efforts and provided personal funds exceeding £4,000 (equivalent to modern millions) to support Greek forces against the Ottomans.[62] Byron's involvement unified fractious Greek leaders temporarily and boosted international morale, though he succumbed to fever on April 19, 1824, at Missolonghi, becoming a martyr symbol for the cause.[63] Other notable volunteers included Scottish officer Thomas Gordon, who participated in naval actions, and French general Charles Nicolas Fabvier, who led expeditions such as the 1823 raid on Nafplio.[7] Up to 1,200 foreign fighters from across Europe joined Greek irregulars, forming battalions that fought in key battles despite limited overall military impact.[3] Financial aid proved crucial, with the London Philhellenic Committee, founded in March 1823 by figures like Edward Blaquiere and Jeremy Bentham, coordinating relief efforts including provisions, weapons, and loans totaling millions of pounds—specifically £800,000 in 1824 and £2,000,000 in 1825—to sustain the provisional Greek government amid Ottoman blockades.[64] In the United States, philhellene groups outfitted eight ships carrying cargo valued under $138,000, including the Tontine ($13,856) and Levant ($8,547), delivering food, clothing, and munitions, though some shipments were intercepted or diverted.[65] These contributions supplemented Greek internal resources strained by civil strife and funded orphan relief, with American donors arranging adoptions for war-displaced children.[66] Motivations stemmed from Enlightenment-era admiration for classical Greece, viewing the revolution as a rebirth of ancient liberty against Ottoman "despotism," fueled by reports of massacres like Chios in 1822 that evoked humanitarian outrage.[60] Philhellenes, often products of classical education, saw parallels between Greek struggles and contemporary liberal ideals of self-determination, with religious dimensions framing it as Christian resistance to Muslim rule.[67] Figures like Byron were driven by romantic individualism and anti-tyrannical fervor, prioritizing cultural regeneration over pragmatic geopolitics, though some critiqued the idealized view ignoring Byzantine discontinuities.[68] This support amplified propaganda in Europe, swaying public opinion despite governmental reluctance.[69]  harboring romantic ideals of aiding the descendants of ancient Hellenes in reclaiming their classical heritage, only to confront a fragmented society marked by factionalism and self-interest. Local leaders, often klephts (mountain bandits) or primates (wealthy landowners), prioritized personal vendettas and plunder over unified strategy, leading to chronic disorganization in military efforts.[70] This reality clashed with expectations, as volunteers like the Germans in the Peloponnese encountered illiterate fighters more akin to medieval guerrillas than Periclean citizens, prompting early disillusionment.[71] Greek infighting escalated into full civil wars between 1823 and 1825, dividing forces between mainland klephts and islanders while Ottoman-Egyptian armies advanced unopposed. Philhellenes such as Edward Trelawny and John William Bowden witnessed or were entangled in these conflicts, with some caught mediating futilely between rival chieftains like Theodoros Kolokotronis and Alexandros Mavrokordatos.[72] Lord Byron, arriving in Missolonghi in January 1824, expressed frustration in letters over the "eternal squabbles" among Greek leaders, viewing their disunity as a primary obstacle to effective resistance against Ottoman forces.[73] Atrocities committed by Greek revolutionaries further eroded philhellene enthusiasm, exemplified by the massacre at Tripolitsa in October 1821, where an estimated 8,000 to 30,000 Ottoman civilians, including women and children, were slaughtered after the city's fall. British philhellene Thomas Gordon, present during the event, condemned the indiscriminate killings as barbaric, protesting to Greek commanders who dismissed foreign objections.[74] Such acts, while initially justified by some as retaliation for Ottoman reprisals, alienated observers and fueled criticism in Europe, with accounts highlighting the moral hazards of involvement.[75] The harsh physical realities of campaigning compounded these political disillusionments, with disease claiming far more lives than combat. Epidemics of malaria, typhus, and dysentery ravaged volunteer camps due to unsanitary conditions and inadequate medical care; for instance, Lord Byron succumbed to fever—possibly a malarial relapse—on April 19, 1824, after just months in Greece.[76] Of approximately 1,000 to 1,200 foreign volunteers, hundreds perished from illness, including many Germans who either succumbed in the field or perished en route home, underscoring the lethal toll beyond battlefield heroics.[70] [71] Financial aid raised by philhellenic committees in Europe, totaling tens of thousands of pounds, was frequently mismanaged or embezzled by Greek factions, eroding trust and leading to scandals that discredited the cause abroad. Returning survivors, including disillusioned figures like Karl von Normann-Ehrenfels, published scathing memoirs decrying the revolution's chaos, though their critiques were often overshadowed by the narrative of ultimate Greek success.[72] Despite these setbacks, a core of dedicated philhellenes persisted, contributing to key victories like the naval Battle of Navarino in 1827, yet the era's realities tempered the movement's idealism with pragmatic recognition of Greece's entrenched divisions.[71]20th- and 21st-Century Developments

Institutional and Academic Continuations

The foreign archaeological schools established in Athens during the 19th century have served as enduring institutional embodiments of philhellenism, maintaining focused research on ancient Greek civilization into the 20th and 21st centuries through excavations, scholarly training, and cultural preservation efforts. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), founded in 1881, emerged as the largest U.S.-based overseas center for classical studies, resuming extensive fieldwork post-World War II, including major digs at sites like Corinth and the Athenian Agora, while offering fellowships that trained generations of archaeologists and classicists.[77] By the Cold War era, the ASCSA aligned with U.S. cultural diplomacy in Greece, supporting stabilization initiatives amid political turmoil and emphasizing the continuity of Greek heritage to counter ideological threats.[78] Its Gennadius Library, established in 1922, expanded to house over 150,000 volumes on Greek history and culture, facilitating interdisciplinary research that bridges ancient and modern Hellenism.[77] Similarly, the British School at Athens (BSA), operational since 1886, perpetuated philhellenic scholarship through systematic archaeological surveys and publications, such as the Annual of the British School at Athens, which documented findings from sites like Knossos into the late 20th century. In the 21st century, the BSA has hosted conferences explicitly examining philhellenism's historical role, including a 2023 international event on British philhellenism and the Greek Revolution, co-organized with Greek institutions to foster global academic dialogue on Hellenic legacies.[79] These efforts, alongside collaborations with Greek authorities, underscore the BSA's role in sustaining British admiration for Greek antiquity amid evolving geopolitical contexts.[80] Academic continuations extend to specialized centers and honors recognizing philhellenic contributions. Harvard University's Center for Hellenic Studies, established in 1958 and operating a branch in Greece since 1992, conducts workshops on philhellenism's enduring influence, analyzing its impact on modern Greek identity formation through classical reception studies.[81] In recognition of such work, Greece has instituted modern observances like Philhellenism Day (March 25), honoring 20th- and 21st-century scholars; in 2021, U.S. archaeologists Jack Davis, Sharon Stocker, and Charles Williams received awards for excavations revealing Bronze Age Greek sites, exemplifying how empirical archaeological pursuits sustain philhellenic ideals.[82] These institutions collectively prioritize verifiable data from digs and texts, resisting politicized narratives by grounding interpretations in material evidence, though their foreign-led structures have occasionally sparked debates over interpretive authority in Greek historiography.[4]Political and Cultural Manifestations Post-WWII

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, philhellenism manifested politically through U.S. foreign policy initiatives that invoked ancient Greece's democratic legacy to counter communist expansion. The Truman Doctrine, announced on March 12, 1947, committed $400 million in military and economic aid to Greece and Turkey, explicitly framing Greece as the "cradle of democracy" threatened by Soviet-backed insurgents during the Greek Civil War (1946–1949).[83][84] This rhetoric renewed 19th-century American philhellenism, adapting it to Cold War containment strategy, as evidenced by appeals from archaeologists like Carl Blegen, who in mid-1940s writings urged U.S. support to preserve Greece's classical heritage against totalitarianism.[84] The Marshall Plan (1948 onward) extended this by allocating funds for cultural preservation, including $200,000 for reconstructing the Stoa of Attalos in Athens, tying economic stabilization to symbolic restoration of Hellenic monuments.[84] Diplomatically, Greek antiquities served as instruments of philhellenic goodwill in U.S.-Greece relations starting in the late 1940s. Greek officials gifted artifacts, such as vases and sculptures, to American presidents and dignitaries—including items presented to Harry Truman—to underscore shared civilizational roots and foster alliance-building amid NATO's formation (Greece joined in 1952).[85][86] These exchanges, documented in presidential collections, reflected a strategic cultural diplomacy that leveraged philhellenism to legitimize Western intervention, though critics later noted they commodified heritage for geopolitical ends.[85] Culturally, post-WWII philhellenism evolved into "neo-philhellenism," emphasizing Greece's unbroken cultural continuity and the Greek diaspora's role in global advocacy, as articulated in academic analyses of the era.[87] In the U.S. and Europe, Cold War narratives recast Hellenism as an ideological bulwark, with institutions like the American School of Classical Studies at Athens promoting excavations and publications that aligned archaeological work with anti-communist democracy promotion.[84] This period saw sustained academic engagement, including U.S.-funded missions like the Allied Mission for Observing Greek Elections (1946), which reinforced philhellenic ideals of fair governance rooted in classical precedents, though such efforts were pragmatically driven by strategic interests rather than pure altruism.[84] By the late 20th century, manifestations included tourism booms and educational programs highlighting Greece's heritage, but these often prioritized marketable antiquity over modern complexities.[87]Criticisms, Controversies, and Debates

Romantic Idealization Versus Historical Continuity

Philhellenes in the early 19th century often romanticized modern Greeks as direct, unadulterated heirs to classical antiquity, envisioning their liberation from Ottoman rule as a revival of Periclean democracy and Homeric heroism, while downplaying intervening historical transformations such as the Byzantine Empire and Islamic influences.[88] This idealization, rooted in Winckelmann's neoclassical aesthetics and reinforced by poets like Byron, portrayed contemporary Greece as a "damsel in distress" awaiting Western rescue to reclaim its ancient splendor, yet it frequently ignored empirical divergences in language, religion, and social structure.[89] Upon arrival, many philhellenes expressed disillusionment, decrying modern Greeks as culturally "degenerate" or "Orientalized" due to perceived laziness, corruption, and deviation from classical norms, which fueled misohellenism—a counter-movement questioning the ethnic and cultural continuity between ancient and modern populations.[90][91] In contrast, historical and scientific evidence substantiates significant continuity between ancient and modern Greeks across genetic, linguistic, and cultural dimensions, challenging the philhellenic narrative's selective romanticism. Genetic analyses of ancient DNA from Mycenaean burials (circa 1700–1200 BCE) reveal that modern Greeks derive approximately 70–80% of their ancestry from Bronze Age populations in the Aegean, with minimal dilution from later Slavic or Anatolian migrations, as confirmed by autosomal DNA comparisons showing closer affinity to Mycenaeans than to contemporaneous Minoans.[92][93] Linguistically, modern Greek evolved continuously from ancient dialects through Koine Greek during the Hellenistic and Byzantine eras, retaining core vocabulary, grammar, and syntax—evident in shared terms like demos (people) and polis (city-state)—with Byzantine scholars preserving classical texts that informed the post-independence revival.[94] Culturally, Orthodox Christianity served as a conduit for classical heritage, integrating pagan philosophical traditions into patristic theology and folk customs, while archaeological continuity in settlement patterns and material culture from antiquity through the Ottoman period underscores demographic persistence in core regions like the Peloponnese and Attica.[95] The tension between romantic idealization and historical continuity highlights philhellenism's role in perpetuating a bifurcated view of Greek history, often sidelining the Byzantine "middle ages" as a cultural rupture to emphasize a direct classical-to-modern link that justified intervention.[96] Critics argue this projection not only bred unrealistic expectations—leading to philhellenes like Edward Blaquière lamenting the "Asiatic" traits in Greek irregulars—but also imposed Western standards that undervalued indigenous resilience, such as the klephtic traditions of resistance that echoed ancient guerrilla tactics without classical pomp.[91] Empirical historiography, however, counters such disillusionment by demonstrating causal links: Ottoman millet system preserved Greek Orthodox identity, limiting assimilation and enabling linguistic evolution, thus affirming continuity over rupture.[97] This debate persists in assessing philhellenism's legacy, where its motivational idealism accelerated independence in 1830 despite factual mismatches, yet risked cultural chauvinism by prioritizing aesthetic fantasy over verifiable heritage.[4]Associations with Orientalism and Cultural Looting

Philhellenism has been associated with Orientalism, particularly in postcolonial critiques, where it is portrayed as reinforcing Western binaries between a civilized, classical "Europe" embodied by ancient Greece and a despotic "Orient" represented by Ottoman rule over modern Greeks. Edward Said's framework in Orientalism (1978) implies that philhellenic admiration detached Greece from its Eastern context, framing Ottoman Turks as alien oppressors whose removal would restore a purportedly European heritage, thereby justifying intervention as a civilizing mission.[98] This view posits philhellenism as complicit in imperial discourse, with European supporters viewing modern Greeks not as authentic heirs but as degraded remnants needing Western rescue to revive classical purity, a narrative that overlooked Byzantine and Ottoman cultural continuities in Greece.[99] However, such interpretations, while influential in academia, have faced criticism for conflating philhellenic enthusiasm—rooted in Enlightenment neoclassicism—with broader colonial exploitation; philhellenes often emphasized Greek exceptionalism precisely to distinguish them from Oriental stereotypes applied to other Eastern peoples.[100] In Germany, for instance, philhellenism and Orientalism initially overlapped in Romantic scholarship but diverged by the mid-19th century, as classicists prioritized Greek purity over Semitic or Persian influences, marginalizing "Oriental" elements in Hellenic studies to maintain a Eurocentric canon.[101] This selective focus contributed to a cultural narrative where philhellenism served national identity formation, as in Bavarian philhellenes who supported Greek independence while advancing German claims to classical heritage, sometimes at the expense of acknowledging Eastern admixtures in Greek antiquity.[102] The philhellenic fervor also intersected with cultural looting, as European collectors and archaeologists, motivated by neoclassical admiration, acquired Greek antiquities amid the instability of Ottoman rule and the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830). During the war, chaotic sieges and uprisings led to documented plundering of sites like the Acropolis, where fragments of ancient sculptures were fragmented or removed, with some artifacts ending up in Western collections under the guise of preservation.[103] Philhellenes such as the British historian George Finlay amassed extensive private collections of Greek vases, inscriptions, and bronzes in the 1820s–1830s, often purchasing from local markets fed by wartime excavations or sales, contributing to the depletion of on-site contexts.[104] Similarly, German philhellene Ludwig Ross, who participated in independence efforts, conducted excavations in Athens and exported artifacts like metopes to Munich, exemplifying how philhellenic fieldwork blurred into extractive practices justified as scholarly salvage from "barbarian" threats.[105] This era's "antiquities rush" reflected international competition for cultural prestige, with philhellenic networks facilitating the flow of objects to European museums; for example, British and French diplomats pre-dating the war, influenced by philhellenic ideals, secured permissions from Ottoman authorities for removals like the Parthenon Marbles (1801–1812), setting precedents for later wartime acquisitions.[106] While proponents argued these actions protected heritage from destruction—citing Ottoman neglect or war damage—critics note the lack of consent from Greek communities and the prioritization of Western display over local retention, fueling ongoing repatriation debates.[107] Empirical records indicate that between 1820 and 1830, hundreds of artifacts, including Cycladic figurines and Attic pottery, entered private philhellene collections via opportunistic digs, with minimal reinvestment in Greek institutions until the post-independence Bavarian regency formalized but continued exports.[108]Impact on Greek Historiography and Identity

Philhellenism significantly shaped modern Greek national identity by promoting the notion of direct cultural and ethnic continuity between ancient Hellas and the revolutionaries of the 1820s, portraying the latter as direct heirs to classical civilization whose liberation would revive antiquity's glory.[109] This narrative, embraced by European sympathizers during the Greek War of Independence, encouraged Greek nationalists to adopt classical nomenclature in administration, education, and public life—such as reviving ancient-derived terms for institutions and restoring classical toponyms—thereby forging a Hellenic self-image detached from Ottoman influences and aligned with Western ideals of progress.[109][95] In historiography, philhellenism initially fostered a selective focus on classical antiquity as the core of Greek history, marginalizing the Byzantine and Ottoman eras as periods of interruption or decline rather than integral phases of continuity.[109] Early post-independence works, such as those by Greek scholars in the 1830s, idealized ancient models for modern society, constructing a teleological narrative where the War of Independence represented a regeneration of ancient virtues.[109] This approach, influenced by philhellenic rhetoric, contributed to an initial discontinuity in national history, later addressed by historian Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos in his multi-volume History of the Greek Nation (1860–1874), which synthesized Byzantine and medieval elements into a unified ethnic lineage to counter foreign skepticism about modern Greeks' worthiness as ancient descendants.[109] The philhellenic emphasis on ancient primacy reinforced a Eurocentric identity for Greece, positioning it as the foundational cradle of Western civilization and justifying claims to cultural artifacts like the Parthenon Marbles, while embedding national pride in classical achievements over more recent historical complexities.[109] However, this framework has drawn critique for oversimplifying causal historical developments, as philhellenic advocacy often prioritized romantic ideological appeals—such as Homer's epics as prolegomena to independence—over empirical assessment of medieval transformations in Greek society.[110] British philhellene George Finlay's extensive histories, spanning from antiquity to the 19th century, exemplified this by integrating modern events into a classical continuum, influencing subsequent Greek scholarship despite his outsider perspective.[91] Overall, philhellenism's legacy in Greek historiography and identity lies in its role as a catalytic ideology for nation-building, though one that selectively curated historical memory to align with contemporaneous European intellectual currents.[109]Legacy and Broader Influence

Effects on Western Civilization and Nationalism

Philhellenism reinforced the perception of ancient Greece as the foundational cradle of Western civilization, emphasizing its contributions to democracy, philosophy, and aesthetics in European and American intellectual life. During the 19th century, the movement popularized neoclassical styles in architecture, sculpture, and literature, drawing directly from Greek models to symbolize Enlightenment ideals of reason and liberty. For instance, philhellenic enthusiasm led to widespread adoption of Greek-inspired educational curricula across Europe, where figures like Johann Joachim Winckelmann had earlier advocated for Greek art as the pinnacle of human achievement, influencing institutions from Prussian gymnasia to American colleges. This cultural revival not only preserved classical texts through translations and excavations but also positioned Greece as a moral exemplar, countering perceptions of Ottoman rule as antithetical to civilized progress.[111][4] In terms of nationalism, philhellenism provided a template for linking ancient heritage to modern self-determination, inspiring European nationalists to invoke classical antiquity for legitimizing their own ethnic and civic identities. The Greek War of Independence (1821–1830), bolstered by philhellene volunteers and funds, demonstrated nationalism's efficacy against imperial decay, challenging the Concert of Europe and emboldening revolts in Belgium (1830) and Poland (1830–1831) by framing liberation as a reclamation of historical glory. In Germany, while philhellenism initially clashed with emerging Germanic ethnic nationalism— as Humboldt's classical humanism sought to transcend medieval traditions— it ultimately infused cultural nationalism with Hellenic universalism, evident in the use of Greek motifs in unification symbolism post-1871. Similarly, in the United States, philhellenism aligned ancient Greece with republican virtues, reinforcing Manifest Destiny narratives that equated American expansion with Periclean Athens. This interplay elevated heritage-based nationalism, though it often idealized a selective, pre-Christian Greek past at the expense of Byzantine continuities.[112][113][114]Contributions to Greek Independence and Modern State-Building

Philhellenes provided direct military support during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830) through the arrival of approximately 500 to 1,000 foreign volunteers from Western Europe and the United States, who fought alongside Greek revolutionaries against Ottoman forces.[115] These volunteers participated in key engagements, such as the Battle of Peta in July 1822, where a philhellene-led battalion suffered heavy losses due to tactical inexperience, highlighting both their commitment and limitations in combat effectiveness. Around 400 philhellenes perished in the conflict, contributing to the war effort despite often disorganized integration with Greek irregular forces.[116] Financial aid from philhellenic organizations proved crucial for sustaining the revolution. The London Greek Committee, formed in 1823, coordinated subscriptions for military supplies and facilitated Greece's first international loan of £472,000 in February 1824, with approximately £278,000 disbursed to fund arms, ships, and provisional government operations amid Ottoman sieges.[117] Prominent individuals like Lord Byron amplified these efforts; arriving in Greece in 1823, he personally donated £4,000 (equivalent to about £332,000 in modern terms) to procure vessels and supplies for the revolutionary cause at Missolonghi.[118] Such contributions helped prevent total collapse during crises like the Egyptian intervention in 1825–1826. Beyond battlefield and fiscal support, philhellenism exerted moral and diplomatic pressure that influenced European powers to intervene decisively. Public campaigns in Britain, France, and Germany romanticized the Greek struggle as a rebirth of classical liberty, fostering sympathy that pressured governments despite initial neutrality; this culminated in the Battle of Navarino on October 20, 1827, where allied fleets destroyed the Ottoman-Egyptian armada, shifting the war's momentum toward Greek victory.[3] The movement's advocacy ensured international recognition of Greek autonomy via the Treaty of Constantinople in 1832, establishing the modern Kingdom of Greece under Bavarian Prince Otto as its first monarch.[119] In state-building after independence, philhellenes continued aiding institutional development by promoting European-style reforms and providing expertise. Figures like Richard Church, a British philhellene, served as commander of Greek forces post-1827, helping professionalize the military and integrate it into the new state's framework. Philhellenic networks influenced the drafting of Greece's 1844 constitution, emphasizing liberal principles drawn from Western models, while ongoing loans and investments from sympathizers stabilized the economy and facilitated infrastructure projects aligned with Enlightenment ideals of modernization.[1] This external support, though sometimes paternalistic, bridged Greece's transition from revolutionary chaos to a sovereign entity oriented toward European integration.[4]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/philhellene