Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Plastid

View on Wikipedia

A plastid is a membrane-bound organelle found in the cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. Plastids are considered to be intracellular endosymbiotic cyanobacteria.[1]

Examples of plastids include chloroplasts (used for photosynthesis); chromoplasts (used for synthesis and storage of pigments); leucoplasts (non-pigmented plastids, some of which can differentiate); and apicoplasts (non-photosynthetic plastids of apicomplexa derived from secondary endosymbiosis).

A permanent primary endosymbiosis event occurred about 1.5 billion years ago in the Archaeplastida clade—land plants, red algae, green algae and glaucophytes—probably with a cyanobiont, a symbiotic cyanobacteria related to the genus Gloeomargarita.[2][3] Another primary endosymbiosis event occurred later, between 140 and 90 million years ago, in the photosynthetic plastids Paulinella amoeboids of the cyanobacteria genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, or the "PS-clade".[4][5] Secondary and tertiary endosymbiosis events have also occurred in a wide variety of organisms; and some organisms developed the capacity to sequester ingested plastids—a process known as kleptoplasty.

A. F. W. Schimper[6][a] was the first to name, describe, and provide a clear definition of plastids, which possess a double-stranded DNA molecule that long has been thought of as circular in shape, like that of the circular chromosome of prokaryotic cells—but now, perhaps not; (see "..a linear shape"). Plastids are sites for manufacturing and storing pigments and other important chemical compounds used by the cells of autotrophic eukaryotes. Some contain biological pigments such as used in photosynthesis or which determine a cell's color. Plastids in organisms that have lost their photosynthetic properties are highly useful for manufacturing molecules like the isoprenoids.[8]

In land plants

[edit]

Chloroplasts, proplastids, and differentiation

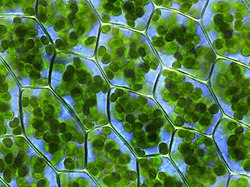

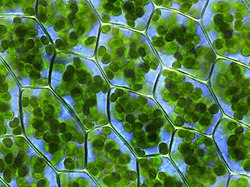

[edit]In land plants, the plastids that contain chlorophyll can perform photosynthesis, thereby creating internal chemical energy from external sunlight energy while capturing carbon from Earth's atmosphere and furnishing the atmosphere with life-giving oxygen. These are the chlorophyll-plastids—and they are named chloroplasts; (see top graphic).

Other plastids can synthesize fatty acids and terpenes, which may be used to produce energy or as raw material to synthesize other molecules. For example, plastid epidermal cells manufacture the components of the tissue system known as plant cuticle, including its epicuticular wax, from palmitic acid—which itself is synthesized in the chloroplasts of the mesophyll tissue. Plastids function to store different components including starches, fats, and proteins.[9]

All plastids are derived from proplastids (also named proplasts[10]), which are present in the meristematic regions of the plant. Proplastids and young chloroplasts typically divide by binary fission, but more mature chloroplasts also have this capacity.

Plant proplastids (undifferentiated plastids) may differentiate into several forms, depending upon which function they perform in the cell, (see top graphic). They may develop into any of the following variants:[11]

- Chloroplasts: typically green plastids that perform photosynthesis.

- Etioplasts: precursors of chloroplasts.

- Chromoplasts: coloured plastids that synthesize and store pigments.

- Gerontoplasts: plastids that control the dismantling of the photosynthetic apparatus during plant senescence.

- Leucoplasts: colourless plastids that synthesize monoterpenes.

Leucoplasts differentiate into even more specialized plastids, such as:

- the aleuroplasts;

- Amyloplasts: storing starch and detecting gravity—for maintaining geotropism.

- Elaioplasts: storing fats.

- Proteinoplasts: storing and modifying protein.

- or Tannosomes: synthesizing and producing tannins and polyphenols.

Depending on their morphology and target function, plastids have the ability to differentiate or redifferentiate between these and other forms.

Plastomes and Chloroplast DNA/ RNA; plastid DNA and plastid nucleoids

[edit]Each plastid creates multiple copies of its own unique genome, or plastome, (from 'plastid genome')—which for a chlorophyll plastid (or chloroplast) is equivalent to a 'chloroplast genome', or a 'chloroplast DNA'.[12][13] The number of genome copies produced per plastid is variable, ranging from 1000 or more in rapidly dividing new cells, encompassing only a few plastids, down to 100 or less in mature cells, encompassing numerous plastids.

A plastome typically contains a genome that encodes transfer ribonucleic acids (tRNA)s and ribosomal ribonucleic acids (rRNAs). It also contains proteins involved in photosynthesis and plastid gene transcription and translation. But these proteins represent only a small fraction of the total protein set-up necessary to build and maintain any particular type of plastid. Nuclear genes (in the cell nucleus of a plant) encode the vast majority of plastid proteins; and the expression of nuclear and plastid genes is co-regulated to coordinate the development and differention of plastids.

Many plastids, particularly those responsible for photosynthesis, possess numerous internal membrane layers. Plastid DNA exists as protein-DNA complexes associated as localized regions within the plastid's inner envelope membrane; and these complexes are called 'plastid nucleoids'. Unlike the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell, a plastid nucleoid is not surrounded by a nuclear membrane. The region of each nucleoid may contain more than 10 copies of the plastid DNA.

Where the proplastid (undifferentiated plastid) contains a single nucleoid region located near the centre of the proplastid, the developing (or differentiating) plastid has many nucleoids localized at the periphery of the plastid and bound to the inner envelope membrane. During the development/ differentiation of proplastids to chloroplasts—and when plastids are differentiating from one type to another—nucleoids change in morphology, size, and location within the organelle. The remodelling of plastid nucleoids is believed to occur by modifications to the abundance of and the composition of nucleoid proteins.

In normal plant cells long thin protuberances called stromules sometimes form—extending from the plastid body into the cell cytosol while interconnecting several plastids. Proteins and smaller molecules can move around and through the stromules. Comparatively, in the laboratory, most cultured cells—which are large compared to normal plant cells—produce very long and abundant stromules that extend to the cell periphery.

In 2014, evidence was found of the possible loss of plastid genome in Rafflesia lagascae, a non-photosynthetic parasitic flowering plant, and in Polytomella, a genus of non-photosynthetic green algae. Extensive searches for plastid genes in both taxons yielded no results, but concluding that their plastomes are entirely missing is still disputed.[14] Some scientists argue that plastid genome loss is unlikely since even these non-photosynthetic plastids contain genes necessary to complete various biosynthetic pathways including heme biosynthesis.[14][15]

Even with any loss of plastid genome in Rafflesiaceae, the plastids still occur there as "shells" without DNA content,[16] which is reminiscent of hydrogenosomes in various organisms.

In algae and protists

[edit]Plastid types in algae and protists include:

- Chloroplasts: found in green algae (plants) and other organisms that derived their genomes from green algae.

- Muroplasts: also known as cyanoplasts or cyanelles, the plastids of glaucophyte algae are similar to plant chloroplasts, excepting they have a peptidoglycan cell wall that is similar to that of bacteria.

- Rhodoplasts: the red plastids found in red algae, which allows them to photosynthesize down to marine depths of 268 m.[11] The chloroplasts of plants differ from rhodoplasts in their ability to synthesize starch, which is stored in the form of granules within the plastids. In red algae, floridean starch is synthesized and stored outside the plastids in the cytosol.[17]

- Secondary and tertiary plastids: from endosymbiosis of green algae and red algae.

- Leucoplast: in algae, the term is used for all unpigmented plastids. Their function differs from the leucoplasts of plants.

- Apicoplast: the non-photosynthetic plastids of Apicomplexa derived from secondary endosymbiosis.

The plastid of photosynthetic Paulinella species is often referred to as the 'cyanelle' or chromatophore, and is used in photosynthesis.[18][19] It had a much more recent endosymbiotic event, in the range of 140–90 million years ago, which is the only other known primary endosymbiosis event of cyanobacteria.[20][21]

Etioplasts, amyloplasts and chromoplasts are plant-specific and do not occur in algae.[citation needed] Plastids in algae and hornworts may also differ from plant plastids in that they contain pyrenoids.[22]

Inheritance

[edit]In reproducing, most plants inherit their plastids from only one parent. In general, angiosperms inherit plastids from the female gamete, where many gymnosperms inherit plastids from the male pollen. Algae also inherit plastids from just one parent. Thus the plastid DNA of the other parent is completely lost.

In normal intraspecific crossings—resulting in normal hybrids of one species—the inheriting of plastid DNA appears to be strictly uniparental; i.e., from the female. In interspecific hybridisations, however, the inheriting is apparently more erratic. Although plastids are inherited mainly from the female in interspecific hybridisations, there are many reports of hybrids of flowering plants producing plastids from the male. Approximately 20% of angiosperms, including alfalfa (Medicago sativa), normally show biparental inheriting of plastids.[23]

DNA damage and repair

[edit]The plastid DNA of maize seedlings is subjected to increasing damage as the seedlings develop.[24] The DNA damage is due to oxidative environments created by photo-oxidative reactions and photosynthetic/ respiratory electron transfer. Some DNA molecules are repaired but DNA with unrepaired damage is apparently degraded to non-functional fragments.

DNA repair proteins are encoded by the cell's nuclear genome and then translocated to plastids where they maintain genome stability/ integrity by repairing the plastid's DNA.[25] For example, in chloroplasts of the moss Physcomitrella patens, a protein employed in DNA mismatch repair (Msh1) interacts with proteins employed in recombinational repair (RecA and RecG) to maintain plastid genome stability.[26]

Origin

[edit]Plastids are thought to be descended from endosymbiotic cyanobacteria. The primary endosymbiotic event of the Archaeplastida is hypothesized to have occurred around 1.5 billion years ago[27] and enabled eukaryotes to carry out oxygenic photosynthesis.[28] Three evolutionary lineages in the Archaeplastida have since emerged in which the plastids are named differently: chloroplasts in green algae and/or plants, rhodoplasts in red algae, and muroplasts in the glaucophytes. The plastids differ both in their pigmentation and in their ultrastructure. For example, chloroplasts in plants and green algae have lost all phycobilisomes, the light harvesting complexes found in cyanobacteria, red algae and glaucophytes, but instead contain stroma and grana thylakoids. The glaucocystophycean plastid—in contrast to chloroplasts and rhodoplasts—is still surrounded by the remains of the cyanobacterial cell wall. All these primary plastids are surrounded by two membranes.

The plastid of photosynthetic Paulinella species is often referred to as the 'cyanelle' or chromatophore, and had a much more recent endosymbiotic event about 90–140 million years ago; it is the only known primary endosymbiosis event of cyanobacteria outside of the Archaeplastida.[18][19] The plastid belongs to the "PS-clade" (of the cyanobacteria genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus), which is a different sister clade to the plastids belonging to the Archaeplastida.[4][5]

In contrast to primary plastids derived from primary endosymbiosis of a prokaryoctyic cyanobacteria, complex plastids originated by secondary endosymbiosis in which a eukaryotic organism engulfed another eukaryotic organism that contained a primary plastid.[29] When a eukaryote engulfs a red or a green alga and retains the algal plastid, that plastid is typically surrounded by more than two membranes. In some cases these plastids may be reduced in their metabolic and/or photosynthetic capacity. Algae with complex plastids derived by secondary endosymbiosis of a red alga include the heterokonts, haptophytes, cryptomonads, and most dinoflagellates (= rhodoplasts). Those that endosymbiosed a green alga include the euglenids and chlorarachniophytes (= chloroplasts). The Apicomplexa, a phylum of obligate parasitic alveolates including the causative agents of malaria (Plasmodium spp.), toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii), and many other human or animal diseases also harbor a complex plastid (although this organelle has been lost in some apicomplexans, such as Cryptosporidium parvum, which causes cryptosporidiosis). The 'apicoplast' is no longer capable of photosynthesis, but is an essential organelle, and a promising target for antiparasitic drug development.

Some dinoflagellates and sea slugs, in particular of the genus Elysia, take up algae as food and keep the plastid of the digested alga to profit from the photosynthesis; after a while, the plastids are also digested. This process is known as kleptoplasty, from the Greek, kleptes (κλέπτης), thief.

Plastid development cycle

[edit]

In 1977 J.M Whatley proposed a plastid development cycle which said that plastid development is not always unidirectional but is instead a complicated cyclic process. Proplastids are the precursor of the more differentiated forms of plastids, as shown in the diagram to the right.[30]

See also

[edit]- Mitochondrion – Organelle in eukaryotic cells responsible for respiration

- Cytoskeleton – Network of filamentous proteins that forms the internal framework of cells

- Photosymbiosis – Type of symbiotic relationship

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sometimes Ernst Haeckel is credited to coin the term plastid, but his "plastid" includes nucleated cells and anucleated "cytodes"[7] and thus totally different concept from the plastid in modern literature.

References

[edit]- ^ Sato N (2007). "Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids". In Wise RR, Hoober JK (eds.). The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 23. Springer Netherlands. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ^ Moore KR, Magnabosco C, Momper L, Gold DA, Bosak T, Fournier GP (2019). "An Expanded Ribosomal Phylogeny of Cyanobacteria Supports a Deep Placement of Plastids". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 1612. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01612. PMC 6640209. PMID 31354692.

- ^ Vries, Jan de; Gould, Sven B. (2018-01-15). "The monoplastidic bottleneck in algae and plant evolution". Journal of Cell Science. 131 (2): jcs203414. doi:10.1242/jcs.203414. ISSN 0021-9533. PMID 28893840.

- ^ a b Marin, Birger; Nowack, Eva CM; Glöckner, Gernot; Melkonian, Michael (2007-06-05). "The ancestor of the Paulinella chromatophore obtained a carboxysomal operon by horizontal gene transfer from a Nitrococcus-like γ-proteobacterium". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 85. Bibcode:2007BMCEE...7...85M. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-85. PMC 1904183. PMID 17550603.

- ^ a b Ochoa de Alda, Jesús A. G.; Esteban, Rocío; Diago, María Luz; Houmard, Jean (2014-01-29). "The plastid ancestor originated among one of the major cyanobacterial lineages". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4937. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4937O. doi:10.1038/ncomms5937. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 25222494.

- ^ Schimper, A.F.W. (1882) "Ueber die Gestalten der Stärkebildner und Farbkörper" Botanisches Centralblatt 12(5): 175–178.

- ^ Haeckel, E. (1866) "Morphologische Individuen erster Ordnung: Plastiden oder Plasmastücke" in his Generelle Morphologie der Organismen Bd. 1, pp. 269–289

- ^ Picozoans Are Algae After All: Study | The Scientist Magazine®

- ^ Kolattukudy, P.E. (1996) "Biosynthetic pathways of cutin and waxes, and their sensitivity to environmental stresses", pp. 83–108 in: Plant Cuticles. G. Kerstiens (ed.), BIOS Scientific publishers Ltd., Oxford

- ^ Azevedo J, Courtois F, Hakimi MA, Demarsy E, Lagrange T, Alcaraz JP, Jaiswal P, Maréchal-Drouard L, Lerbs-Mache S (2008-07-01). "Intraplastidial trafficking of a phage-type RNA polymerase is mediated by a thylakoid RING-H2 protein". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105 (26): 9123–9128. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800909105. PMC 2449375. PMID 18567673.

- ^ a b Wise, Robert R. (2006). "The Diversity of Plastid Form and Function". The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol. 23. Springer. pp. 3–26. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_1. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ^ Wicke, S; Schneeweiss, GM; dePamphilis, CW; Müller, KF; Quandt, D (2011). "The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function". Plant Molecular Biology. 76 (3–5): 273–297. Bibcode:2011PMolB..76..273W. doi:10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. PMC 3104136. PMID 21424877.

- ^ Wicke, S; Naumann, J (2018). "Molecular evolution of plastid genomes in parasitic flowering plants". Advances in Botanical Research. 85: 315–347. doi:10.1016/bs.abr.2017.11.014. ISBN 9780128134573.

- ^ a b "Plants Without Plastid Genomes". The Scientist. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ^ Barbrook AC, Howe CJ, Purton S (February 2006). "Why are plastid genomes retained in non-photosynthetic organisms?". Trends in Plant Science. 11 (2): 101–8. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.004. PMID 16406301.

- ^ "DNA of Giant 'Corpse Flower' Parasite Surprises Biologists". April 2021.

- ^ Viola R, Nyvall P, Pedersén M (July 2001). "The unique features of starch metabolism in red algae". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 268 (1474): 1417–22. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1644. PMC 1088757. PMID 11429143.

- ^ a b Lhee, Duckhyun; Ha, Ji-San; Kim, Sunju; Park, Myung Gil; Bhattacharya, Debashish; Yoon, Hwan Su (2019-02-22). "Evolutionary dynamics of the chromatophore genome in three photosynthetic Paulinella species - Scientific Reports". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 2560. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.2560L. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-38621-8. PMC 6384880. PMID 30796245.

- ^ a b Gabr, Arwa; Grossman, Arthur R.; Bhattacharya, Debashish (2020-05-05). Palenik, B. (ed.). "Paulinella , a model for understanding plastid primary endosymbiosis". Journal of Phycology. 56 (4). Wiley: 837–843. Bibcode:2020JPcgy..56..837G. doi:10.1111/jpy.13003. ISSN 0022-3646. PMC 7734844. PMID 32289879.

- ^ Sánchez-Baracaldo, Patricia; Raven, John A.; Pisani, Davide; Knoll, Andrew H. (2017-09-12). "Early photosynthetic eukaryotes inhabited low-salinity habitats". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (37): E7737 – E7745. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E7737S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1620089114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5603991. PMID 28808007.

- ^ Luis Delaye; Cecilio Valadez-Cano; Bernardo Pérez-Zamorano (15 March 2016). "How Really Ancient Is Paulinella Chromatophora?". PLOS Currents. 8. doi:10.1371/CURRENTS.TOL.E68A099364BB1A1E129A17B4E06B0C6B. ISSN 2157-3999. PMC 4866557. PMID 28515968. Wikidata Q36374426.

- ^ Robison, T. A., Oh, Z. G., Lafferty, D., Xu, X., Villarreal, J. C. A., Gunn, L. H., Li, F.-W. (3 January 2025). "Hornworts reveal a spatial model for pyrenoid-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in land plants". Nature Plants. 11 (1). Nature Publishing Group: 63–73. doi:10.1038/s41477-024-01871-0. ISSN 2055-0278. PMID 39753956.

- ^ Zhang Q (March 2010). "Why does biparental plastid inheritance revive in angiosperms?". Journal of Plant Research. 123 (2): 201–6. Bibcode:2010JPlR..123..201Z. doi:10.1007/s10265-009-0291-z. PMID 20052516. S2CID 5108244.

- ^ Kumar RA, Oldenburg DJ, Bendich AJ (December 2014). "Changes in DNA damage, molecular integrity, and copy number for plastid DNA and mitochondrial DNA during maize development". Journal of Experimental Botany. 65 (22): 6425–39. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru359. PMC 4246179. PMID 25261192.

- ^ Oldenburg DJ, Bendich AJ (2015). "DNA maintenance in plastids and mitochondria of plants". Frontiers in Plant Science. 6: 883. Bibcode:2015FrPS....6..883O. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00883. PMC 4624840. PMID 26579143.

- ^ Odahara M, Kishita Y, Sekine Y (August 2017). "MSH1 maintains organelle genome stability and genetically interacts with RECA and RECG in the moss Physcomitrella patens". The Plant Journal. 91 (3): 455–465. Bibcode:2017PlJ....91..455O. doi:10.1111/tpj.13573. PMID 28407383.

- ^ Ochoa de Alda JA, Esteban R, Diago ML, Houmard J (September 2014). "The plastid ancestor originated among one of the major cyanobacterial lineages". Nature Communications. 5: 4937. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4937O. doi:10.1038/ncomms5937. PMID 25222494.

- ^ Hedges SB, Blair JE, Venturi ML, Shoe JL (January 2004). "A molecular timescale of eukaryote evolution and the rise of complex multicellular life". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 4: 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-2. PMC 341452. PMID 15005799.

- ^ Chan CX, Bhattachary D (2010). "The Origin of Plastids". Nature Education. 3 (9): 84.

- ^ Whatley, Jean M. (1978). "A Suggested Cycle of Plastid Developmental Interrelationships". The New Phytologist. 80 (3): 489–502. Bibcode:1978NewPh..80..489W. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1978.tb01581.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2431207.

Further reading

[edit]- Hanson MR, Köhler RH. "A Novel View of Chloroplast Structure". Plant Physiology Online. Archived from the original on 2005-06-14.

- Wycliffe P, Sitbon F, Wernersson J, Ezcurra I, Ellerström M, Rask L (October 2005). "Continuous expression in tobacco leaves of a Brassica napus PEND homologue blocks differentiation of plastids and development of palisade cells". The Plant Journal. 44 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02482.x. PMID 16167891.

- Birky CW (2001). "The inheritance of genes in mitochondria and chloroplasts: laws, mechanisms, and models" (PDF). Annual Review of Genetics. 35: 125–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090231. PMID 11700280. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Chan CX, Bhattacharya D (2010). "The origins of plastids". Nature Education. 3 (9): 84.

- Bhattacharya D, ed. (1997). Origins of Algae and their Plastids. New York: Springer-Verlag/Wein. ISBN 978-3-211-83036-9.

- Gould SB, Waller RF, McFadden GI (2008). "Plastid evolution". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 59 (1): 491–517. Bibcode:2008AnRPB..59..491G. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092915. PMID 18315522. S2CID 30458113.

- Keeling PJ (March 2010). "The endosymbiotic origin, diversification and fate of plastids". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 365 (1541): 729–48. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0103. PMC 2817223. PMID 20124341.

External links

[edit]- Transplastomic plants for biocontainment (biological confinement of transgenes) — Co-extra research project on coexistence and traceability of GM and non-GM supply chains

- Tree of Life Eukaryotes