Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

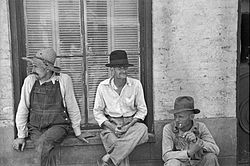

Redneck

View on Wikipedia

Redneck is a derogatory term mainly applied to white Americans perceived to be crass and unsophisticated, closely associated with rural whites of the southern United States.[1][2] Its meaning possibly stems from the sunburn found on farmers' necks dating back to the late 19th century.[3] Authors Joseph Flora and Lucinda MacKethan describe the stereotype as follows:

- Redneck is a derogatory term currently applied to some lower-class and working-class southerners. The term, which came into common usage in the 1930s, is derived from the redneck's beginnings as a "yeoman farmer" whose neck would burn as they toiled in the fields. These yeoman farmers settled along the Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina coasts.[4]

Its modern usage is similar in meaning to cracker (especially regarding Texas, Georgia, and Florida), hillbilly (especially regarding Appalachia and the Ozarks),[5] and white trash (but without the last term's suggestions of immorality).[6][7][8] In Britain, the Cambridge Dictionary definition states: "A poor, white person without education, esp. one living in the countryside in the southern US, who is believed to have prejudiced ideas and beliefs. This word is usually considered offensive."[9] People from the white South sometimes jocularly call themselves "rednecks" as insider humor.[10]

Some people claim that the term’s origin is that during the West Virginia Mine Wars of the early 1920s, workers organizing for labor rights donned red bandanas, worn tied around their necks, as they marched up Blair Mountain in a pivotal confrontation. The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum commemorates their struggle for fair wages. A monument in front of the George Buckley Community Center in Marmet, WV, part of the "Courage in the Hollers Project" of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum depicts the silhouettes of four mine workers cut from steel plate, wearing bright red bandanas around their necks or holding them in their hands.[11][12] However, the term was used as early as 1830 to refer to white rural Southern laborers[13], so although the 1920s wearers of red bandanas may have used the term, they did not originate it.

By the 1970s, the term had become offensive slang, its meaning expanded to include racism, loutishness, and opposition to modern ways.[14]

Patrick Huber, in his monograph A Short History of Redneck: The Fashioning of a Southern White Masculine Identity, emphasized the theme of masculinity in the 20th-century expansion of the term, noting: "The redneck has been stereotyped in the media and popular culture as a poor, dirty, uneducated, and racist Southern white man."[15]

19th and early 20th centuries

[edit]Political term for poor farmers

[edit]The term originally characterized farmers that had a red neck, caused by sunburn from long hours working in the fields. A citation from provides a definition as "poorer inhabitants of the rural districts ... men who work in the field, as a matter of course, generally have their skin stained red and burnt by the sun, and especially is this true of the back of their necks".[16] Hats were usually worn and they protected that wearer's head from the sun, but also provided psychological protection by shading the face from close scrutiny.[17] The back of the neck however was more exposed to the sun and allowed closer scrutiny about the person's background in the same way callused working hands could not be easily covered.

By 1900, "rednecks" was in common use to designate the political factions inside the Democratic Party comprising poor white farmers in the South.[18] The same group was also often called the "wool hat boys" (for they opposed the rich men, who wore expensive silk hats). A newspaper notice in Mississippi in August 1891 called on rednecks to rally at the polls at the upcoming primary election:[19]

Primary on the 25th.

And the "rednecks" will be there.

And the "Yaller-heels" will be there, also.

And the "hayseeds" and "gray dillers", they'll be there, too.

And the "subordinates" and "subalterns" will be there to rebuke their slanderers and traducers.

And the men who pay ten, twenty, thirty, etc. etc. per cent on borrowed money will be on hand, and they'll remember it, too.

By , the political supporters of the Mississippi Democratic Party politician James K. Vardaman—chiefly poor white farmers—began to describe themselves proudly as "rednecks", even to the point of wearing red neckerchiefs to political rallies and picnics.[20]

Linguist Sterling Eisiminger, based on the testimony of informants from the Southern United States, speculated that the prevalence of pellagra in the region during the Great Depression may have contributed to the rise in popularity of the term; red, inflamed skin is one of the first symptoms of that disorder to appear.[21]

Coal miners

[edit]

The term "redneck" in the early 20th century was occasionally used in reference to American coal miner union members who wore red bandanas for solidarity. The sense of "a union man" dates at least to the 1910s and was especially popular during the 1920s and 1930s in the coal-producing regions of West Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.[22] It was also used by union strikers to describe poor white strikebreakers.[23]

Late 20th and early 21st centuries

[edit]Writers Edward Abbey and Dave Foreman also use "redneck" as a political call to mobilize poor rural white Southerners. "In Defense of the Redneck" was a popular essay by Ed Abbey. One popular early Earth First! bumper sticker was "Rednecks for Wilderness". Murray Bookchin, an urban leftist and social ecologist, objected strongly to Earth First!'s use of the term as "at the very least, insensitive".[24] However, many Southerners have proudly embraced the term as a self-identifier.[25][26] Similarly to Earth First!'s use, the self-described "anti-racist, pro-gun, pro-labor" group Redneck Revolt have used the term to signal its roots in the rural white working-class and celebration of what member Max Neely described as "redneck culture".[27]

As political epithet

[edit]According to Chapman and Kipfer in their "Dictionary of American Slang", by 1975 the term had expanded in meaning beyond the poor Southerner to refer to "a bigoted and conventional person, a loutish ultra-conservative".[28] For example, in 1960 John Bartlow Martin expressed Senator John F. Kennedy should not enter the Indiana Democratic presidential primary because the state was "redneck conservative country". Indiana, he told Kennedy, was a state "suspicious of foreign entanglements, conservative in fiscal policy, and with a strong overlay of Southern segregationist sentiment".[29] Writer William Safire observed that it is often used to attack white Southern conservatives, and more broadly to degrade working class and rural whites that are perceived by urban progressives to be insufficiently progressive.[30] At the same time, some white Southerners have reappropriated the word, using it with pride and defiance as a self-identifier.[31]

In popular culture

[edit]- Johnny Russell was nominated for a Grammy Award in for his recording of "Rednecks, White Socks and Blue Ribbon Beer". Further songs referencing rednecks include "Longhaired Redneck" by David Allan Coe, "Rednecks" by Randy Newman, "Redneck Friend" by Jackson Browne, "Redneck Woman" by Gretchen Wilson, "Redneck Yacht Club" by Craig Morgan, "Redneck" by Lamb of God, "Redneck Crazy" by Tyler Farr, "Red Neckin' Love Makin' Night" by Conway Twitty, "Up Against The Wall Redneck Mother" by Jerry Jeff Walker, "Your Redneck Past" by Ben Folds Five, "American Idiot" by Green Day, and "Picture to Burn" by Taylor Swift.

- Comedian Jeff Foxworthy's comedy album You Might Be a Redneck If... cajoled listeners to evaluate their own behavior in the context of stereotypical redneck behavior.

- The Swedish band Rednex adopted the name as a misspelling of "rednecks."

Outside the United States

[edit]Historical Scottish Covenanter usage

[edit]In Scotland in the 1640s, the Covenanters rejected rule by bishops, often signing manifestos using their own blood. Some wore red cloth around their neck to signify their position, and were called rednecks by the Scottish ruling class to denote that they were the rebels in what came to be known as The Bishop's War that preceded the rise of Cromwell.[32][33] Eventually, the term began to mean simply "Presbyterian", especially in communities along the Scottish border. Because of the large number of Scottish immigrants in the pre-revolutionary American South, some historians have suggested that this may be the origin of the term in the United States.[34]

Dictionaries document the earliest American citation of the term's use for Presbyterians in , as "a name bestowed upon the Presbyterians of Fayetteville (North Carolina)".[16][33]

South Africa

[edit]An Afrikaans term which translates literally as "redneck", rooinek, is used as a disparaging term for English South Africans, in reference to their supposed naïveté as later arrivals in the region in failing to protect themselves from the sun.[35]

See also

[edit]- Bogan, Australian term

- Chav, British term

- Class discrimination

- Culture of the Southern United States

- Country (identity)

- Çomar, Turkish term

- Florida cracker

- Georgia cracker

- Hillbilly

- List of ethnic slurs

- Old Stock Americans

- Plain Folk of the Old South

- Redlegs – poor whites that live on Barbados and a few other Caribbean islands

- Stereotypes of white Americans

- West Texas Rednecks

- White trash

- Yokel

- Redneck Revolt

References

[edit]- ^ Harold Wentworth, and Stuart Berg Flexner, Dictionary of American Slang (1975) p. 424.

- ^ "Redneck – Definition and More". Merriam Webster. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Huber, 1995.

- ^ The Redneck Stereotype, The Companion to Southern Literature

- ^ Harkins, Anthony (2005-10-13). Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon. Oxford University Press. p. 39. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195189506.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-518950-6.

- ^ Wray (2006) p. x.

- ^ Ernest Cashmore and James Jennings, eds. Racism: essential readings (2001) p. 36.

- ^ Jim Goad, The Redneck Manifesto: How Hillbillies, Hicks, and White Trash Became America's Scapegoats (1998) pp. 17–19.

- ^ "redneck". Cambridge Dictionary.

- ^ John Morreall (2011). Comic Relief: A Comprehensive Philosophy of Humor. John Wiley & Sons. p. 106. ISBN 9781444358292.

- ^ "Do You Know Where the Word "Redneck" Comes From? Mine Wars Museum Opens, Revives Lost Labor History". 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Courage in the Hollers".

- ^ "redneck". Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2025-08-17.

- ^ Robert L. Chapman, Dictionary of American Slang (1995) p. 459; William Safire, Safire's New Political Dictionary (1993) pp. 653-54; Tom Dalzell, The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English: J–Z (2005) 2:1603.

- ^ Huber, Patrick (1995). "A short history of Redneck: The fashioning of a southern white masculine identity". Southern Cultures. 1 (2): 145–166. doi:10.1353/scu.1995.0074. S2CID 143996001.

- ^ a b Frederic Gomes Cassidy & Joan Houston Hall, Dictionary of American Regional English VOL.IV (2002) p. 531. ISBN 978-0674008847

- ^ Elaine Stone (2018). The Dynamics of Fashion. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 254. ISBN 9781501324000. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ Kirwan, Albert D. (1951). Revolt of the Rednecks: Mississippi Politics, 1876-1925. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. ISBN 9780813134284.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Patrick Huber; Kathleen Drowne (2001). "Redneck: A New Discovery". American Speech. 76 (4): 434–437. doi:10.1215/00031283-76-4-434.

- ^ Kirwan (1951), p. 212.

- ^ Sterling Eisiminger (Autumn 1984). "Redneck". American Speech. 59 (3): 284. doi:10.2307/454514. JSTOR 454514.

- ^ Patrick Huber, "Red Necks and Red Bandanas: Appalachian Coal Miners and the Coloring of Union Identity, 1912–1936", Western Folklore, Winter 2006.

- ^ James Green (2015). The Devil Is Here in These Hills: West Virginia's Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom. New York: Grove Press. p. 380. ISBN 9780802124654.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray; Foreman, Dave. Defending the Earth: A Dialogue Between Murray Bookchin and Dave Foreman. South End Press. 1991. p. 95.

- ^ Kyff, Rob (August 3, 2007). "Embrace Slurs, Reclaim Pride". Hartford Courant. p. D.10. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

Many southerners have adopted the disparaging term redneck as a banner of pride.

- ^ Page, Clarence (July 18, 1989). "'Redneck' is not a word that a politician should take lightly". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 27, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Watt, Cecilia Saixue (11 July 2017). "Redneck Revolt: the armed leftwing group that wants to stamp out fascism". theguardian.com. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ Robert L. Chapman and Barbara Ann Kipfer, Dictionary of American Slang (3rd ed. 1995) p. 459.

- ^ Ray E. Boomhower (2015). John Bartlow Martin: A Voice for the Underdog. Indiana UP. p. 273. ISBN 9780253016188.

- ^ William Safire, Safire's political dictionary (2008) p. 612

- ^ Goad, The Redneck Manifesto: How Hillbillies, Hicks, and White Trash Became America's Scapegoats (1998) p. 18

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett. (1989) Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b redneck (1989); Oxford English Dictionary second edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Herman, Arthur, How the Scots Invented the Modern World. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2001, p. 235.

- ^ Jean Bedford, A Dictionary of South African English, Oxford

Further reading

[edit]- Abbey, Edward. "In Defense of the Redneck", from Abbey's Road: Take the Other. (E. P. Dutton, 1979)

- Ferrence, Matthew, "You Are and You Ain't: Story and Literature as Redneck Resistance", Journal of Appalachian Studies, 18 (2012), 113–30.

- Goad, Jim. The Redneck Manifesto: How Hillbillies, Hicks, and White Trash Became America's Scapegoats (Simon & Schuster, 1997).

- Harkins, Anthony. Hillbilly: A cultural history of an American icon (2003).

- Huber, Patrick. "A short history of Redneck: The fashioning of a southern white masculine identity." Southern Cultures 1#2 (1995): 145–166. online

- Jarosz, Lucy, and Victoria Lawson. "'Sophisticated people versus rednecks': Economic restructuring and class difference in America's West." Antipode 34#1 (2002): 8-27.

- Shirley, Carla D. "'You might be a redneck if ... ' Boundary Work among Rural, Southern Whites." Social forces 89#1 (2010): 35–61. in JSTOR

- West, Stephen A. From Yeoman to Redneck in the South Carolina Upcountry, 1850–1915 (2008)

- Weston, Ruth D. "The Redneck Hero in the Postmodern World", South Carolina Review, (Spring 1993)

- Wilson, Charles R. and William Ferris, eds. Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, (1989)

- Wray, Matt. Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness (2006)

External links

[edit]- Poor Whites in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (history)