Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of Roman deities

View on Wikipedia

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

| Related topics |

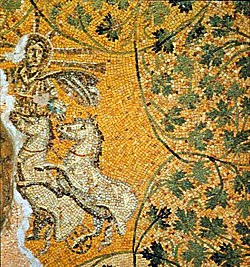

The Roman deities most widely known today are those the Romans identified with Greek counterparts, integrating Greek myths, iconography, and sometimes religious practices into Roman culture, including Latin literature, Roman art, and religious life as it was experienced throughout the Roman Empire. Many of the Romans' own gods remain obscure, known only by name and sometimes function, through inscriptions and texts that are often fragmentary. This is particularly true of those gods belonging to the archaic religion of the Romans dating back to the era of kings, the so-called "religion of Numa", which was perpetuated or revived over the centuries. Some archaic deities have Italic or Etruscan counterparts, as identified both by ancient sources and by modern scholars. Throughout the Empire, the deities of peoples in the provinces were given new theological interpretations in light of functions or attributes they shared with Roman deities.

A survey of theological groups as constructed by the Romans themselves is followed by an extensive alphabetical list[1] concluding with examples of common epithets shared by multiple divinities.

Collectives

[edit]Even in invocations, which generally required precise naming, the Romans sometimes spoke of gods as groups or collectives rather than naming them as individuals. Some groups, such as the Camenae and Parcae, were thought of as a limited number of individual deities, even though the number of these might not be given consistently in all periods and all texts. Others are numberless collectives.

Spatial tripartition

[edit]Varro grouped the gods broadly into three divisions of heaven, earth, and underworld:

- di superi, the gods above or heavenly gods, whose altars were designated as altaria.[2]

- di terrestres, "terrestrial gods," whose altars were designated as arae.

- di inferi, the gods below, that is, the gods of the underworld, infernal or chthonic gods, whose altars were foci, fire pits or specially constructed hearths.

More common is a dualistic contrast between superi and inferi.

Triads

[edit]- Archaic Triad: Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus.

- Capitoline Triad: Jupiter, Juno, Minerva.[3]

- Plebeian or Aventine Triad: Ceres, Liber, Libera, dating to 493 BC.[4]

Groupings of twelve

[edit]Lectisternium of 217 BC

[edit]A lectisternium is a banquet for the gods, at which they appear as images seated on couches, as if present and participating. In describing the lectisternium of the Twelve Great gods in 217 BC, the Augustan historian Livy places the deities in gender-balanced pairs:[5]

Divine male-female complements such as these, as well as the anthropomorphic influence of Greek mythology, contributed to a tendency in Latin literature to represent the gods as "married" couples or (as in the case of Venus and Mars) lovers.[citation needed]

Dii Consentes

[edit]Varro uses the name Dii Consentes for twelve deities whose gilded images stood in the forum. These were also placed in six male-female pairs.[6] Although individual names are not listed, they are assumed to be the deities of the lectisternium. A fragment from Ennius, within whose lifetime the lectisternium occurred, lists the same twelve deities by name, though in a different order from that of Livy: Juno, Vesta, Minerva, Ceres, Diana, Venus, Mars, Mercurius, Jove, Neptunus, Vulcanus, Apollo.[7]

The Dii Consentes are sometimes seen as the Roman equivalent of the Greek Olympians. The meaning of Consentes is subject to interpretation, but is usually taken to mean that they form a council or consensus of deities.

Di Flaminales

[edit]The three deities cultivated by the major flamens were:[8]

The twelve deities attended by the minor flamens were:

- Carmentis

- Ceres

- Falacer

- Flora

- Furrina

- Palatua

- Pomona

- Portunus

- Vulcan

- Volturnus

- two other deities whose names are not known[9]

Di selecti

[edit]Varro[10] gives a list of twenty principal gods of Roman religion:

Sabine gods

[edit]Varro, who was himself of Sabine origin, gives a list of Sabine gods who were adopted by the Romans:[11]

Elsewhere, Varro claims Sol Indiges – who had a sacred grove at Lavinium – as Sabine but at the same time equates him with Apollo.[13][14] Of those listed, he writes, "several names have their roots in both languages, as trees that grow on a property line creep into both fields. Saturn, for instance, can be said to have another origin here, and so too Diana."[c]

Varro makes various claims for Sabine origins throughout his works, some more plausible than others, and his list should not be taken at face value.[15] But the importance of the Sabines in the early cultural formation of Rome is evidenced, for instance, by the bride abduction of the Sabine women by Romulus's men, and in the Sabine ethnicity of Numa Pompilius, second king of Rome, to whom are attributed many of Rome's religious and legal institutions.[16] Varro says that the altars to most of these gods were established at Rome by King Tatius as the result of a vow (votum).[d]

Indigitamenta

[edit]The indigitamenta are deities known only or primarily as a name; they may be minor entities, or epithets of major gods. Lists of deities were kept by the College of Pontiffs to assure that the correct names were invoked for public prayers. The books of the Pontiffs are lost, known only through scattered passages in Latin literature. The most extensive lists are provided by the Church Fathers who sought systematically to debunk Roman religion while drawing on the theological works of Varro, also surviving only in quoted or referenced fragments. W.H. Roscher collated the standard modern list of indigitamenta,[17] though other scholars may differ with him on some points.

Di indigetes and novensiles

[edit]The di indigetes were thought by Georg Wissowa to be Rome's indigenous deities, in contrast to the di novensides or novensiles, "newcomer gods". No ancient source, however, poses this dichotomy, which is not generally accepted among scholars of the 21st century. The meaning of the epithet indiges (singular) has no scholarly consensus, and noven may mean "nine" (novem) rather than "new".

Alphabetical list

[edit]A

[edit]

- Abundantia, divine personification of abundance and prosperity.

- Acca Larentia, a diva of complex meaning and origin in whose honor the Larentalia was held.

- Acis, god of the Acis River in Sicily.

- Aerecura, goddess possibly of Celtic origin, associated with the underworld and identified with Proserpina.

- Aequitas, divine personification of fairness.

- Aesculapius, the Roman equivalent of Asclepius, god of health and medicine.

- Aeternitas, goddess and personification of eternity.

- Agenoria, goddess and personification of activity.

- Aion (Latin spelling Aeon), Hellenistic god of cyclical or unbounded time, related to the concepts of aevum or saeculum

- Aius Locutius, divine voice that warned the Romans of the imminent Gallic invasion.

- Alernus or Elernus (possibly Helernus), an archaic god whose sacred grove (lucus) was near the Tiber river. He is named definitively only by Ovid.[18] The grove was the birthplace of the nymph Cardea, and despite the obscurity of the god, the state priests still carried out sacred rites (sacra) there in the time of Augustus.[19] Alernus may have been a chthonic god, if a black ox was the correct sacrificial offering to him, since dark victims were offered to underworld gods.[20] Dumézil wanted to make him a god of beans.[21]

- Angerona, goddess who relieved people from pain and sorrow.

- Angitia, goddess associated with snakes and Medea.

- Anna Perenna, early goddess of the "circle of the year", her festival was celebrated March 15.

- Annona, the divine personification of the grain supply to the city of Rome.

- Antevorta, goddess of the future and one of the Camenae; also called Porrima.

- Apollo, god of poetry, music, and oracles. Twin brother of Diana and one of the Dii Consentes.

- Arimanius, an obscure Mithraic god.

- Aura, often plural Aurae, "the Breezes".

- Aurora, goddess of the dawn.

- Averruncus, a god propitiated to avert calamity.

B

[edit]

- Bacchus, god of wine, sensual pleasures, and truth, originally a cult title for the Greek Dionysus and identified with the Roman Liber.

- Bellona or Duellona, war goddess.

- Bona Dea, the "women's goddess"[22] with functions pertaining to fertility, healing, and chastity.

- Bonus Eventus, divine personification of "Good Outcome".

- Bubona, goddess of cattle.

C

[edit]- Caca, an archaic fire goddess and "proto-Vesta";[23] the sister of Cacus.

- Cacus, originally an ancient god of fire, later regarded as a giant.

- Caelus, god of the sky before Jupiter.

- Camenae, goddesses with various attributes including fresh water, prophecy, and childbirth. There were four of them: Carmenta, Egeria, Antevorta, and Postvorta.

- Cardea, goddess of the hinge (cardo), identified by Ovid with Carna (below)

- Carmenta, goddess of childbirth and prophecy, and assigned a flamen minor. The leader of the Camenae.

- Carmentes, two goddesses of childbirth: Antevorta and Postvorta or Porrima, future and past.

- Carna, goddess who preserved the health of the heart and other internal organs.

- Ceres, goddess of the harvest and mother of Proserpina, and one of the Dii Consentes. The Roman equivalent of Demeter [Greek goddess].

- Clementia, goddess of forgiveness and mercy.

- Cloacina, goddess who presided over the system of sewers in Rome; identified with Venus.

- Concordia, goddess of agreement, understanding, and marital harmony.

- Consus, chthonic god protecting grain storage.

- Cupid, Roman god of love. The son of Venus, and equivalent to Greek Eros.

- Cura, personification of care and concern who according to a single source[24] created humans from clay.

- Cybele, an imported tutelary goddess often identified with Magna Mater

D

[edit]- Dea Dia, goddess of growth.

- Dea Tacita ("The Silent Goddess"), a goddess of the dead; later equated with the earth goddess Larenta.

- Dea Tertiana and Dea Quartana, the sister goddesses of tertian and quartan fevers. Presumably daughters or sisters of Dea Febris.

- Decima, minor goddess and one of the Parcae (Roman equivalent of the Moirai). The measurer of the thread of life, her Greek equivalent was Lachesis.

- Devera or Deverra, goddess who ruled over the brooms used to purify temples in preparation for various worship services, sacrifices and celebrations; she protected midwives and women in labor.

- Diana, goddess of the hunt, the moon, virginity, and childbirth, twin sister of Apollo and one of the Dii Consentes.

- Diana Nemorensis, local version of Diana. The Roman equivalent of Artemis [Greek goddess]

- Discordia, personification of discord and strife. The Roman equivalent of Eris [Greek goddess]

- Dius Fidius, god of oaths, associated with Jupiter.

- Di inferi, deities associated with death and the underworld.

- Disciplina, personification of discipline.

- Dis Pater or Dispater, god of wealth and the underworld; perhaps a translation of Greek Plouton (Pluto).

E

[edit]

- Egeria, water nymph or goddess, later considered one of the Camenae.

- Empanda or Panda, a goddess whose temple never closed to those in need.

- Epona, Gallo-Roman goddess of horses and horsemanship, usually assumed to be of Celtic origin.

F

[edit]- Falacer, obscure god. He was assigned a minor flamen.

- Fama, goddess of fame and rumor.

- Fascinus, phallic god who protected from invidia (envy) and the evil eye.

- Fauna, goddess of prophecy, but perhaps a title of other goddesses such as Maia.

- Faunus, god of flocks.

- Faustitas, goddess who protected herd and livestock.

- Febris, goddess of fevers, with the power to cause or prevent fevers and malaria. Accompanied by Dea Tertiana and Dea Quartiana.

- Februus, god of Etruscan origin for whom the month of February was named; concerned with purification

- Fecunditas, personification of fertility.

- Felicitas, personification of good luck and success.

- Ferentina, patron goddess of the city Ferentinum, Latium, protector of the Latin commonwealth.

- Feronia, goddess concerned with wilderness, plebeians, freedmen, and liberty in a general sense. She was also an Underworld goddess.

- Fides, personification of loyalty.

- Flora, goddess of flowers, was assigned a flamen minor.

- Fornax, goddess probably conceived of to explain the Fornacalia, "Oven Festival."

- Fontus or Fons, god of wells and springs.

- Fortuna, goddess of fortune.

- Fufluns, god of wine, natural growth and health. He was adopted from Etruscan religion.

- Fulgora, personification of lightning.

- Furrina, goddess whose functions are mostly unknown, but in archaic times important enough to be assigned a flamen.

G

[edit]- Genius, the tutelary spirit or divinity of each individual

- Gratiae, Roman term for the Charites or Graces.

H

[edit]

- Hercules, god of strength, whose worship was derived from the Greek hero Heracles but took on a distinctly Roman character.

- Hermaphroditus, an androgynous Greek god whose mythology was imported into Latin literature.

- Honos, a divine personification of honor.

- Hora, the wife of Quirinus.

I

[edit]- Indiges, the deified Aeneas.

- Intercidona, minor goddess of childbirth; invoked to keep evil spirits away from the child; symbolised by a cleaver.

- Inuus, god of fertility and sexual intercourse, protector of livestock.

- Invidia, goddess of envy and wrongdoing.

J

[edit]

- Janus, double-faced or two-headed god of beginnings and endings and of doors.

- Juno, Queen of the gods, goddess of matrimony, and one of the Dii Consentes. Equivalent to Greek Hera.

- Jupiter, King of the gods, god of storms, lightning, sky, and one of the Dii Consentes; was assigned a flamen maior. Equivalent to Greek Zeus.

- Justitia, goddess of justice.

- Juturna, goddess of fountains, wells, and springs.

- Juventas, goddess of youth.

L

[edit]- Lares, household gods.

- Latona, goddess of light.

- Laverna, patroness of thieves, con men and charlatans.

- Lemures, the malevolent dead.

- Levana, goddess of the rite through which fathers accepted newborn babies as their own.

- Letum, personification of death.[citation needed]

- Liber, a god of male fertility, viniculture and freedom, assimilated to Roman Bacchus and Greek Dionysus.

- Libera, Liber's female equivalent, assimilated to Roman Proserpina and Greek Persephone.

- Liberalitas, goddess or personification of generosity.

- Libertas, goddess or personification of freedom.

- Libitina, goddess of death, corpses and funerals.

- Lua, goddess to whom soldiers sacrificed captured weapons, probably a consort of Saturn.

- Lucina, goddess of childbirth, but often as an aspect of Juno.

- Luna, goddess of the moon.

- Lupercus, god of shepherds and wolves; as the god of the Lupercalia, his identity is obscure, but he is sometimes identified with the Greek god Pan.

- Lympha, often plural lymphae, a water deity assimilated to the Greek nymphs.

M

[edit]

- Mana Genita, goddess of infant mortality

- Manes, the souls of the dead who came to be seen as household deities.

- Mania, the consort of the Etruscan underworld god Mantus, and perhaps to be identified with the tenebrous Mater Larum; not to be confused with the Greek Maniae.

- Mantus, an Etruscan god of the dead and ruler of the underworld.

- Mars, god of war and father of Romulus, the founder of Rome; one of the Archaic Triad assigned a flamen maior; lover of Venus; one of the Dii Consentes. Greek equivalent-Ares.

- Mater Matuta, goddess of dawn and childbirth, patroness of mariners.

- Meditrina, goddess of healing, introduced to account for the festival of Meditrinalia.

- Mefitis or Mephitis, goddess and personification of poisonous gases and volcanic vapours.

- Mellona or Mellonia, goddess of bees and bee-keeping.

- Mena or Mene, goddess of fertility and menstruation.

- Mercury, messenger of the gods and bearer of souls to the underworld, and one of the Dii Consentes. Roman counterpart of the Greek god Hermes.

- Minerva, goddess of wisdom, war, the arts, industries and trades, and one of the Dii Consentes. Roman equivalent of the Greek goddess Athena.

- Mithras, god worshipped in the Roman empire; popular with soldiers.

- Molae, daughters of Mars, probably goddesses of grinding of the grain.

- Moneta, minor goddess of memory, equivalent to the Greek Mnemosyne. Also used as an epithet of Juno.

- Mors, personification of death and equivalent of the Greek Thanatos.

- Morta, minor goddess of death and one of the Parcae (Roman equivalent of the Moirai). The cutter of the thread of life, her Greek equivalent was Atropos.

- Murcia or Murtia, a little-known goddess who was associated with the myrtle, and in other sources was called a goddess of sloth and laziness (both interpretations arising from false etymologies of her name). Later equated with Venus in the form of Venus Murcia.

- Mutunus Tutunus, a phallic god.

N

[edit]

- Naenia, goddess of funerary lament.

- Nascio, personification of the act of birth.

- Necessitas, goddess of destiny, the Roman equivalent of Ananke.

- Nemesis, goddess of revenge (Greek), adopted as an Imperial deity of retribution.

- Neptune, god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses, and one of the Dii Consentes. Greek equivalent is Poseidon.

- Nerio, ancient war goddess and the personification of valor. The consort of Mars.

- Neverita, presumed a goddess, and associated with Consus and Neptune in the Etrusco-Roman zodiac of Martianus Capella but otherwise unknown.[25]

- Nixi, also di nixi, dii nixi, or Nixae, goddesses of childbirth.

- Nona, minor goddess, one of the Parcae (Roman equivalent of the Moirai). The spinner of the thread of life, her Greek equivalent was Clotho.

- Nortia a Roman-adopted Etruscan goddess of fate, destiny, and chance from the city of Volsinii, where a nail was driven into a wall of her temple as part a new-year ceremony.

- Nox, goddess of night, derived from the Greek Nyx.

O

[edit]- Ops or Opis, goddess of resources or plenty.

- Orcus, a god of the underworld and punisher of broken oaths.

P

[edit]- Palatua, obscure goddess who guarded the Palatine Hill. She was assigned a flamen minor.

- Pales, deity of shepherds, flocks and livestock.

- Panda, see Empanda.

- Parcae, the three fates.

- Pax, goddess of peace; equivalent of Greek Eirene.

- Penates or Di Penates, household gods.

- Picumnus, minor god of fertility, agriculture, matrimony, infants and children.

- Picus, Italic woodpecker god with oracular powers.

- Pietas, goddess of duty; personification of the Roman virtue pietas.

- Pilumnus, minor guardian god, concerned with the protection of infants at birth.

- Pluto, Greek Plouton, a name for the ruler of the dead popularized through the mystery religions and Greek philosophy, sometimes used in Latin literature and identified with Dis pater or Orcus.

- Pomona, goddess of fruit trees, gardens and orchards; assigned a flamen minor.

- Porrima, goddess of the future. Also called Antevorta. One of the Carmentes and the Camenae.

- Portunus, god of keys, doors, and livestock, he was assigned a flamen minor.

- Postverta or Prorsa Postverta, goddess of childbirth and the past, one of the two Carmentes (other being Porrima).

- Priapus, phallic guardian of gardens, originally Greek.

- Proserpina, Queen of the Dead, goddess of spring and a grain-goddess, the Roman equivalent of the Greek Persephone.

- Providentia, goddess of forethought.

- Pudicitia, goddess and personification of chastity, one of the Roman virtues. Her Greek equivalent was Aidôs.

Q

[edit]- Querquetulanae, nymphs of the oak.

- Quirinus, Sabine god identified with Mars; Romulus, the founder of Rome, was deified as Quirinus after his death. Quirinus was a war god and a god of the Roman people and state, and was assigned a flamen maior; he was one of the Archaic Triad gods.

- Quiritis, goddess of motherhood. Originally Sabine or pre-Roman, she was later equated with Juno.

R

[edit]- Robigo or Robigus, a god or goddess who personified grain disease and protected crops.

- Roma, personification of the Roman state.

- Rumina, goddess who protected breastfeeding mothers.

S

[edit]

- Salacia, goddess of seawater, wife of Neptune.

- Salus, goddess of the public welfare of the Roman people; came to be equated with the Greek Hygieia.

- Sancus, god of loyalty, honesty, and oaths.

- Saturn, a titan, god of harvest and agriculture, the father of Jupiter, Neptune, Juno, and Pluto.

- Scotus, god of darkness (Di inferi); brother of Terra, lover of Nox and opposite Dis. Greek Erebos; deep, shadow and one of the primordial deities.

- Securitas, goddess of security, especially the security of the Roman empire.

- Senectus, god of old age. His Greek equivalent is Geras.

- Silvanus, god of woodlands and forests.

- Sol/Sol Invictus, sun god.

- Somnus, god of sleep; equates with the Greek Hypnos.

- Soranus, a god later subsumed by Apollo in the form Apollo Soranus. An Underworld god.

- Sors, god of luck.

- Spes, goddess of hope.

- Stata Mater, goddess who protected against fires. Sometimes equated with Vesta.

- Sterquilinus ("Manure"), god of fertilizer. Also known as Stercutus, Sterculius, Straculius, Struculius.

- Suadela, goddess of persuasion, her Greek equivalent was Peitho.

- Summanus, god of nocturnal thunder.

- Sulis Minerva, a conflation of the Celtic goddess Sulis and Minerva

T

[edit]- Talasius, a god of marriage

- Tellumo or Tellurus, male counterpart of Tellus.

- Tempestas, a goddess of storms or sudden weather, usually plural as the Tempestates

- Terra Mater or Tellus, goddess of the earth and land. The Greek equivalent is Gaea, mother of titans, consort of Caelus (Uranus).

- Terminus, the rustic god of boundaries.

- Tiberinus, river god; deity of the Tiber river.

- Tibertus, god of the river Anio, a tributary of the Tiber.

- Tranquillitas, goddess of peace and tranquility.

- Trivia, goddess of crossroads and magic, equated with Hecate.

V

[edit]

- Vacuna, ancient Sabine goddess of rest after harvest who protected the farmers' sheep; later identified with Nike and worshipped as a war goddess.

- Vagitanus, or Vaticanus, opens the newborn's mouth for its first cry.

- Vediovus or Veiovis, obscure god, a sort of anti-Jupiter, as the meaning of his name suggests. May be a god of the underworld.

- Venilia or Venelia, sea goddess, wife of Neptune or Faunus.[citation needed]

- Venti, the winds, equivalent to the Greek Anemoi: North wind Aquilo(n) or Septentrio (Greek Boreas); South wind Auster (Greek Notus); East wind Vulturnus (Eurus); West wind Favonius (Zephyrus); Northwest wind Caurus or Corus (see minor winds).

- Venus, goddess of love, beauty, sexuality, and gardens; mother of the founding hero Aeneas; one of the Dii Consentes.

- Veritas, goddess and personification of the Roman virtue of veritas or truth.

- Verminus, god of cattle worms.

- Vertumnus, Vortumnus or Vertimnus, god of the seasons, and of gardens and fruit trees.

- Vesta, goddess of the hearth, the Roman state, and the sacred fire; one of the Dii Consentes.

- Vica Pota, goddess of victory and competitions.

- Victoria, goddess of victory.

- Viduus, god who separated the soul and body after death.

- Virbius, a forest god, the reborn Hippolytus.

- Virtus, god or goddess of military strength, personification of the Roman virtue of virtus.

- Volturnus, god of water, was assigned a flamen minor. Not to be confused with Vulturnus.

- Voluptas, goddess of pleasure.

- Vulcan, god of the forge, fire, and blacksmiths, husband to Venus, and one of the Dii Consentes, was assigned a flamen minor.

Titles and honorifics

[edit]Certain honorifics and titles could be shared by different gods, divine personifications, demi-gods and divi (deified mortals).

Augustus and Augusta

[edit]Augustus, "the elevated or august one" (masculine form) is an honorific and title awarded to Octavian in recognition of his unique status, the extraordinary range of his powers, and the apparent divine approval of his principate. After his death and deification, the title was awarded to each of his successors. It also became a near ubiquitous title or honour for various minor local deities, including the Lares Augusti of local communities, and obscure provincial deities such as the North African Marazgu Augustus. This extension of an Imperial honorific to major and minor deities of Rome and her provinces is considered a ground-level feature of Imperial cult.

Augusta, the feminine form, is an honorific and title associated with the development and dissemination of Imperial cult as applied to Roman Empresses, whether living, deceased or deified as divae. The first Augusta was Livia, wife of Octavian, and the title is then shared by various state goddesses including Bona Dea, Ceres, Juno, Minerva, and Ops; by many minor or local goddesses; and by the female personifications of Imperial virtues such as Pax and Victoria.

Bonus and Bona

[edit]The epithet Bonus, "the Good," is used in Imperial ideology with abstract deities such as Bona Fortuna ("Good Fortune"), Bona Mens ("Good Thinking" or "Sound Mind"), and Bona Spes ("Valid Hope," perhaps to be translated as "Optimism"). During the Republic, the epithet may be most prominent with Bona Dea, "the Good Goddess" whose rites were celebrated by women. Bonus Eventus, "Good Outcome", was one of Varro's twelve agricultural deities, and later represented success in general.[26]

Caelestis

[edit]From the middle Imperial period, the title Caelestis, "Heavenly" or "Celestial" is attached to several goddesses embodying aspects of a single, supreme Heavenly Goddess. [citation needed] The Dea Caelestis was identified with the constellation Virgo ("The Virgin"), who holds the divine balance of justice. In the Metamorphoses of Apuleius,[27] the protagonist Lucius prays to the Hellenistic Egyptian goddess Isis as Regina Caeli, "Queen of Heaven", who is said to manifest also as Ceres, "the original nurturing parent"; Heavenly Venus (Venus Caelestis); the "sister of Phoebus", that is, Diana or Artemis as she is worshipped at Ephesus; or Proserpina as the triple goddess of the underworld. Juno Caelestis was the Romanised form of the Carthaginian Tanit.[28]

Grammatically, the form Caelestis can also be a masculine word, but the equivalent function for a male deity is usually expressed through syncretization with Caelus, as in Caelus Aeternus Iuppiter, "Jupiter the Eternal Sky."

Invictus

[edit]

Invictus ("Unconquered, Invincible") was in use as a divine epithet by the early 3rd century BC. In the Imperial period, it expressed the invincibility of deities embraced officially, such as Jupiter, Mars, Hercules, and Sol. On coins, calendars, and other inscriptions, Mercury, Saturn, Silvanus, Fons, Serapis, Sabazius, Apollo, and the Genius are also found as Invictus. Cicero considers it a normal epithet for Jupiter, in regard to whom it is probably a synonym for Omnipotens. It is also used in the Mithraic mysteries.[30]

Mater and Pater

[edit]Mater ("Mother") was an honorific that respected a goddess's maternal authority and functions, and not necessarily "motherhood" per se. Early examples included Terra Mater (Mother Earth) and the Mater Larum (Mother of the Lares). Vesta, a goddess of chastity usually conceived of as a virgin, was honored as Mater. A goddess known as Stata Mater was a compital deity credited with preventing fires in the city.[31]

From the middle Imperial era, the reigning Empress becomes Mater castrorum et senatus et patriae, the symbolic Mother of military camps, the senate, and the fatherland. The Gallic and Germanic cavalry (auxilia) of the Roman Imperial army regularly set up altars to the "Mothers of the Field" (Campestres, from campus, "field," with the title Matres or Matronae).[32] See also Magna Mater (Great Mother) following.

Gods were called Pater ("Father") to signify their preeminence and paternal care, and the filial respect owed to them. Pater was found as an epithet of Dis, Jupiter, Mars, and Liber, among others.

Magna Mater

[edit]"The Great Mother" was a title given to Cybele in her Roman cult. Some Roman literary sources accord the same title to Maia and other goddesses.[33]

See also

[edit]- Classical planets

- Indigitamenta – Lists of Roman deities kept by the College of Pontiffs.

- Interpretato graeca – Comparison of Ancient Greek to other ancient polytheistic religions.

- List of Greek deities

- List of Mesopatamian deities

- List of Metamorphoses characters

- List of Roman agricultural deities

- List of Roman birth and childhood deities

- Reconstructionist Roman religion

- Roman imperial cult

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Or Novensiles: the spelling -d- for -l- is characteristic of the Sabine language.

- ^ For Fides, see also Semo Sancus or Dius Fidius.

- ^ Latin: e quis nonnulla nomina in utraque lingua habent radices, ut arbores quae in confinio natae in utroque agro serpunt: potest enim Saturnus hic de alia causa esse dictus atque in Sabinis, et sic Diana.

- ^ Tatius is said by Varro to have dedicated altars to "Ops, Flora, Vediovis, and Saturn; to Sol, Luna, Vulcan, and Summanus; and likewise to Larunda, Terminus, Quirinus, Vortumnus, the Lares, Diana, and Lucina."

References

[edit]- ^ Robert Schilling, "Roman Gods," Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992, from the French edition of 1981), pp. 75 online and 77 (note 49). Unless otherwise noted, citations of primary sources are Schilling's.

- ^ Varro, Divine Antiquities, book 5, frg. 65; see also Livy 1.32.9; Paulus apud Festus, p. 27; Servius Danielis, note to Aeneid 5.54; Lactantius Placidus, note to Statius, Theb. 4.459–60.

- ^ Livy, 1.38.7, 1.55.1–6.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus 6.17.2

- ^ Livy, 22.10.9.

- ^ Varro, De re rustica 1.1.4: eos urbanos, quorum imagines ad forum auratae stant, sex mares et feminae totidem.

- ^ Ennius, Annales frg. 62, in J. Vahlen, Ennianae Poesis Reliquiae (Leipzig, 1903, 2nd ed.). Ennius's list appears in poetic form, and the word order may be dictated by the metrical constraints of dactylic hexameter.

- ^ "Flamen | Encyclopedia.com".

- ^ Forsythe, Gary, A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War, University of California Press, August, 2006

- ^ As recorded by Augustine of Hippo, De civitate Dei 7.2.

- ^ Varro, De Lingua Latina 5.74

- ^ Woodard, Roger D. Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman cult. p 184.[when?]

- ^ Varro. De lingua latina. 5.68.

- ^ Rehak, Paul (2006). Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the northern Campus Martius. University of Wisconsin Press. p 94.

- ^ Clark, Anna. (2007). Divine Qualities: Cult and community in republican Rome. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp 37–38;

Dench, Emma. (2005). Romulus' Asylum: Roman Identities from the Age of Alexander to the Age of Hadrian. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp 317–318. - ^ Fowler, W.W. (1922). The Religious Experience of the Roman People. London, UK. p 108.

- ^ W.H. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie (Leipzig: Teubner, 1890–94), vol. 2, pt. 1, pp. 187–233.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 2.67 and 6.105 (1988 Teubner edition).

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 6.106.

- ^ This depends on a proposed emendation of Aternus to Alernus in an entry from Festus, p. 83 in the edition of Lindsay. At Fasti 2.67, a reading of Avernus, though possible, makes no geographical sense. See discussion of this deity by Matthew Robinson, A Commentary on Ovid's Fasti, Book 2 (Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 100–101.

- ^ As noted by Robinson, Commentary, p. 101; Georges Dumézil, Fêtes romaines d'été et d'automne (1975), pp. 225ff., taking the name as Helernus in association with Latin holus, holera, "vegetables." The risks and "excessive fluidity" inherent in Dumézil's reconstructions of lost mythologies were noted by Robert Schilling, "The Religion of the Roman Republic: A Review of Recent Studies," in Roman and European Mythologies, pp. 87–88, and specifically in regard to the myth of Carna as a context for the supposed Helernus.

- ^ Dea feminarum: Macrobius, Saturnalia I.12.28.

- ^ Marko Marinčič, "Roman Archaeology in Vergil's Arcadia (Vergil Eclogue 4; Aeneid 8; Livy 1.7), in Clio and the Poets: Augustan Poetry and the Traditions of Ancient Historiography (Brill, 2002), p. 158.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 220; compare Prometheus.

- ^ de Grummond, N. T., and Simon, E., (Editors) The religion of the Etruscans, University of Texas Press, 2006, p.200

- ^ Hendrik H.J. Brouwer, Bona Dea: The Sources and a Description of the Cult pp. 245–246.

- ^ Apuleius, Metamorphoses 11.2.

- ^ Benko, Stephen, The virgin goddess: studies in the pagan and Christian roots of mariology, Brill, 2004, pp. 112–114: see also pp. 31, 51.

- ^ CIL 03, 11008"A soldier of the Legio I Adiutrix [dedicated this] to the Unconquered God" (Deo Invicto / Ulpius Sabinus / miles legio/nis primae / (A)diutricis).

- ^ Steven Ernst Hijmans, Sol: The Sun in the Art and Religions of Rome (diss., University of Groningen 2009), p. 18, with citations from the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

- ^ Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), pp. 156–157.

- ^ R.W. Davies, "The Training Grounds of the Roman Cavalry," Archaeological Journal 125 (1968), p. 73 et passim.

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.12.16–33. Cited in H.H.J. Brouwer, Bona Dea: The Sources and a Description of the Cult (Brill, 1989), pp. 240, 241.

List of Roman deities

View on GrokipediaBackground and Classification

Overview of the Roman Pantheon

The Roman pantheon consisted of a diverse array of divine powers known as numina, which were originally impersonal, animistic forces associated with natural phenomena, places, and human activities, gradually personified into more defined deities over time.[5] These numina represented the sacred essence inherent in the world, invoked through precise rituals rather than elaborate myths, reflecting an early emphasis on orthopraxy over orthodoxy.[6] Under the influence of Greek culture, particularly from the late Republic onward, many of these forces evolved into anthropomorphic gods with human-like forms, attributes, and narratives, facilitating a syncretic integration of Hellenistic elements into Italic traditions.[5] Historically, Roman worship of these deities traced back to archaic Italic practices in the pre-Republican period, where kings served as chief priests overseeing rudimentary cults tied to agriculture, fertility, and community protection.[6] During the Republic, the system formalized into a state religion managed by specialized priesthoods, with temples and festivals reinforcing civic order and military success.[5] By the Imperial era, the pantheon expanded to incorporate the imperial cult, deifying emperors as divine intermediaries, which integrated personal rulers into the collective worship and symbolized the empire's unity and continuity.[5] Central to Roman polytheism was the distinction between state-sponsored public religion and private household cults, with the former emphasizing collective prosperity through augury, sacrifices, and prodigies interpreted by officials to divine the gods' will.[5] Augury, involving the observation of bird flights and other signs, was essential for validating political and military decisions, while public rituals like animal offerings at temples maintained harmony with the divine (pax deorum).[6] In daily life, deities permeated both spheres: household cults venerated ancestral spirits and protective forces through domestic altars and offerings, ensuring personal and familial well-being alongside the broader societal obligations.[5] The pantheon's hierarchy divided deities into supreme gods (di maiores), who oversaw major cosmic and civic domains, lesser gods (di minores) linked to specific locales or functions, and abstract personifications embodying virtues or forces like fortune or concord.[5] This structure lacked a rigid monotheistic supremacy, allowing for an inclusive polytheism where new numina could be adopted without displacing established ones, adapting to cultural expansions and societal needs.[6]Indigenous, Adopted, and Deified Deities

The Roman pantheon encompassed deities of diverse origins, reflecting the city's expansion and cultural exchanges. Indigenous deities were those native to Latium and central Italy, often embodying local agricultural cycles, natural features, and communal rituals without direct equivalents in other traditions. Adopted deities entered the pantheon through conquest, trade, or diplomatic ties, undergoing processes of syncretism such as interpretatio graeca, where Roman gods were equated with Greek counterparts to facilitate integration. Deified mortals, or divi, represented a unique category achieved via apotheosis, typically reserved for exemplary leaders whose elevation reinforced political legitimacy and required formal ritual validation.[7] Indigenous deities formed the core of early Roman religion, rooted in the Italic landscape and tied to pastoral and agrarian life. Janus, the god of beginnings, transitions, and doorways, symbolized Rome's foundational duality and presided over entrances in both domestic and public spheres, with his temple's gates opening for war and closing for peace. Vesta, goddess of the hearth and home, safeguarded the eternal flame in her circular temple, representing communal stability and the sanctity of the state's stores; her cult emphasized purity and was tended by virgin priestesses. These figures, along with others like the Lares (household protectors) and agricultural deities such as Tellus (earth), lacked elaborate mythologies but were invoked in daily rituals to ensure fertility and protection, distinguishing them from later imports.[8] Adopted deities enriched the pantheon through selective incorporation from neighboring cultures, often prompted by crises or oracles. From Etruria, Rome absorbed divinatory practices and deities like Tinia (equated with Jupiter) and Uni (Juno), influencing temple architecture and augury; for instance, the triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva in Etruscan temples at Veii prefigured Roman Capitoline worship. Greek influences via interpretatio graeca were profound, equating Roman Mars with Greek Ares and Minerva with Athena, while Apollo was introduced directly during a 433 BC plague, with a temple vowed on the Capitoline to avert the epidemic. Eastern deities arrived later, exemplified by the Magna Mater (Cybele), a Phrygian mother goddess brought to Rome in 204 BC amid the Second Punic War following Sibylline prophecies; her cult, including ecstatic rites by eunuch priests (Galli), was established on the Palatine but restricted to avoid disrupting Roman mores. These adoptions blended foreign attributes with Roman cult practices, expanding the pantheon's scope without erasing native elements.[9][10][11] Deified mortals underwent apotheosis, transforming historical figures into gods through senatorial decree, often justified by omens and public sentiment. The process began with Romulus, Rome's legendary founder, who, after his mysterious disappearance in a storm, was proclaimed Quirinus by the senate; Proculus Julius announced his divine ascent, and a cult was established with a flamen and temple on the Quirinal Hill. Julius Caesar's deification in 42 BC marked the imperial precedent: following his assassination, the senate, influenced by Antony's funeral oration and sightings of a comet (sidus Iulium) as a divine sign, declared him divus Julius, ordering a temple and flamen Divi Iulii. Augustus followed in 14 CE, with similar senate approval after his death, including eagle release symbolizing soul ascension and integration into the Julian cult. Criteria for deification emphasized exemplary service, posthumous omens (e.g., prodigies or apparitions), senatorial ratification via consecratio, and the creation of a state cult with priests, altars, and festivals to perpetuate the figure's influence. This practice, extending to select emperors, blurred human and divine realms, serving as a tool for dynastic continuity.[12][13][14]Categories: Indigetes, Novensiles, and Indigitamenta

In Roman religion, deities were classified into ritual and theological categories to facilitate proper invocation and worship, ensuring the maintenance of pax deorum (peace with the gods) through precise priestly procedures. These classifications, preserved in the libri pontificales (pontifical books), distinguished between ancient native gods and later introductions, while also providing specialized formularies for minor or aspectual deities. The pontifices (pontiffs) and augurs played central roles in compiling and applying these categories, drawing on ancient traditions to adapt rituals to Rome's evolving needs during the Republic and Empire.[15] The di indigetes (or dii indigetes) represented the indigenous gods of early Rome, considered the foundational numina tied to the city's origins, territory, and core functions such as agriculture, war, and state protection. These deities, often functional and localized within the pomerium (sacred city boundary), had established cults, temples, and fixed invocation names, reflecting the practical, animistic roots of Roman religion before Greek influences introduced anthropomorphism. Examples include Jupiter (sky and oaths), Juno (marriage and state), Minerva (crafts and wisdom), Mars (war and agriculture), Quirinus (citizen assembly), Janus (beginnings and gates), Vesta (hearth), and Terminus (boundaries). According to scholarly analysis of ancient sources, the pontifices listed around 30 such gods, linked to Numa Pompilius's calendar reforms. Livy references them in the formula for devotio (self-sacrifice in battle), invoking the di indigetes alongside other powers to avert disaster.[15] In contrast, the di novensiles (or dii novensides, meaning "newly settled" gods) encompassed deities adopted later, often from foreign origins, who were granted indiges status after state recognition through temples or Sibylline consultations. These gods addressed emerging needs like healing, trade, and military alliances during Rome's expansion, typically established outside the pomerium initially and invoked in crises. Notable examples include Apollo (healing and prophecy), whose temple was vowed in 433 BC amid a plague and dedicated in 431 BC as Apollo Medicus; Hercules (strength and commerce); Castor and Pollux (victory in battle); Diana (hunting); Mercury (commerce); Neptune (sea); and Magna Mater (Cybele, state protection). Livy describes Apollo's adoption via the Sibylline Books during the epidemic, marking a key instance of integrating a Greek deity into Roman worship. The di novensiles appear in the same devotio formula as the indigetes, highlighting their complementary role in state rituals.[15] The indigitamenta consisted of specialized lists or epithets for minor deities, aspects of major gods, or functional numina, compiled by the pontifices for exact ritual invocation to avoid offending the divine through imprecise address. These formularies, preserved in priestly books and numbering in the hundreds, emphasized the animistic precision of Roman piety, targeting specific actions like plowing, door-opening, or childbirth. Examples include Forculus (doorposts), Limentinus (thresholds), and Cardea (hinges) for household protection; Vervactor (first plowing) and Redarator (second plowing) for agriculture; Juno Lucina (childbirth); and Jupiter Feretrius (treaties). Varro, as cited by Augustine, detailed such door deities in his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum, underscoring their role in daily and state rites. Ovid's Fasti and Gellius's Noctes Atticae further illustrate their use in prayers and sacrifices, with the pontifices ensuring adherence to maintain ritual efficacy.[15]Groupings and Collectives

Spatial and Conceptual Tripartitions

In early Roman religion, the pantheon was organized according to a spatial tripartition that divided the cosmos into three realms: the heavens, the earth, and the underworld. This structure, articulated by the antiquarian Marcus Terentius Varro in his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum, categorized the gods as di superi (heavenly gods, such as Jupiter, whose altars were elevated altaria), di terrestres (earthly gods, including Tellus or Magna Mater, honored on ground-level arae), and di inferi (underworld gods, like Dis Pater or Pluto, offered sacrifices in subterranean favisae). This division influenced temple architecture, such as triple-celled designs symbolizing the realms, and public vows that invoked deities from all three for holistic protection against celestial, terrestrial, and chthonic threats.[16] Parallel to this spatial framework, Roman deities were grouped in conceptual tripartitions based on societal and cosmic functions, rooted in Indo-European traditions and adapted through Italic influences. The archaic triad of Jupiter (embodying sovereignty, law, and priestly authority), Mars (warfare and martial prowess), and Quirinus (agriculture, fertility, and communal prosperity) exemplified this, representing the three Indo-European functions: magical-juridical rule, physical force, and production/sustenance, as analyzed by Georges Dumézil.[17] Quirinus, often linked to the deified Romulus, underscored the productive class's role in community stability, while Mars bridged war and agrarian renewal through rituals like the October Horse sacrifice.[16] These groupings originated in pre-Republican cults, drawing from Sabine traditions (e.g., Quirinus as a Sabine war-agriculture deity) and Etruscan ritual practices that emphasized functional hierarchies in state worship.[18] A notable conceptual variant focused on the agricultural cycle, uniting Ceres (goddess of grain and growth), Libera (goddess of fertility and the underworld), and Liber (deity of wine, seeds, and vegetative liberation) to symbolize sowing, growth, and harvest. This triad reflected Rome's agrarian foundations, with joint festivals invoking their collective power for bountiful yields, distinct from but complementary to the civic functions of the archaic triad.[19] These tripartitions evolved in the Republican era, shaping state religion by integrating local and foreign elements; for instance, the archaic functional model influenced the Capitoline Triad (Jupiter, Juno, Minerva), which incorporated Etruscan temple cults while preserving triadic balance for imperial legitimacy.[20]Sacred Triads

In Roman religion, sacred triads were groups of three deities worshipped collectively in temples and state cults, often reflecting social, political, or functional divisions within society. These triads underscored the structured nature of Roman polytheism, where deities were honored together to symbolize harmony among key aspects of communal life, such as governance, agriculture, and protection. The most prominent triads emerged during the early Republic, integrating indigenous Italic gods with influences from Etruscan and Greek traditions, and were central to public rituals and temple dedications.[21] The Archaic Triad, consisting of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus, represented the foundational structure of early Roman society: sovereignty (Jupiter), military prowess (Mars), and the assembled citizen body (Quirinus). This grouping is attested from the era of Romulus through the Etruscan kings, forming the original Capitoline pantheon before later modifications. It symbolized the Indo-European tripartite division of functions in archaic Roman religion, with the deities sharing a temple on the Capitoline Hill that predated the Republic's formal establishment.[22][23] The Capitoline Triad, comprising Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno Regina, and Minerva, became the preeminent state cult following the temple's dedication in 509 BCE on the Capitoline Hill, marking the transition to republican governance after the expulsion of the monarchy. Jupiter embodied supreme authority and the sky, Juno protected marriage and the state, and Minerva oversaw wisdom, crafts, and strategic warfare; together, they occupied three cellae within the temple, reinforcing Rome's imperial and civic identity. This triad supplanted the earlier Archaic configuration, integrating Etruscan influences while centralizing religious authority in the city's most sacred precinct.[21][24] The Plebeian Triad of Ceres, Liber, and Libera focused on agricultural abundance, wine production, and fertility, serving as patrons of the lower classes during a period of social tension. Vowed in 496 BCE amid a severe famine and dedicated in 493 BCE on the Aventine Hill by consul Spurius Cassius, the temple became a hub for plebeian religious and political activities, housing aediles' offices, legal archives, and fines collected for assaults on magistrates. This triad, equated with Greek Demeter, Dionysus, and Kore, symbolized plebeian autonomy and integration into state religion, particularly after the first plebeian secession, and featured Greek-style frescoes and reliefs that highlighted its cultural synthesis.[25][26] Beyond these core urban triads, localized groups like the one at the Nemi grove—uniting Diana Nemorensis (goddess of the hunt and wilderness), Egeria (a water nymph associated with healing springs), and Virbius (a woodland deity linked to exile and renewal)—illustrated regional variations in worship. This triad, centered in the Arician sanctuary from the Bronze Age through the early Empire, emphasized Diana's multifaceted roles in nature, midwifery, and the underworld, attracting devotees from across Latium and influencing colonial cults in Roman provinces where similar groupings adapted to local Italic traditions.[27]Groups of Twelve Deities

In Roman religion, groups of twelve deities represented a collective of major gods analogous to the Greek Twelve Olympians, emphasizing cosmic and civic harmony through their paired male-female structure. These groupings emerged prominently during times of crisis, such as the Second Punic War, when the Roman state sought divine favor against external threats. The most notable instance was the lectisternium of 217 BC, a ritual banquet ordered by the Sibylline Books following the defeat at Lake Trasimene, where couches (lecti) were prepared for the gods as if they were dining guests.[28] The lectisternium honored twelve deities in six pairs over three days, curated by the decemviri sacris faciundis: Jupiter with Juno, Neptune with Minerva, Mars with Venus, Apollo with Diana, Vulcan with Vesta, and Mercury with Ceres. This event marked the first public lectisternium for such a comprehensive group, integrating both indigenous Roman gods and those adopted from Greek and Etruscan traditions, and it set a precedent for state-sponsored rituals to avert calamity.[29][28] The Dii Consentes, or "Consenting Gods," formalized this grouping as the core pantheon of twelve major deities—six male and six female—whose harmonious counsel symbolized the stability of the Roman state. Listed by the poet Ennius in the late 3rd century BC, the standard roster included Juno, Vesta, Minerva, Ceres, Diana, Venus, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Neptune, Vulcan, and Apollo, often arranged in the same pairs as the 217 BC lectisternium. Gilded statues of these gods were erected in the Roman Forum shortly after the ritual, initially near the Temple of Saturn, and later housed in the Portico Dii Consentes on the Capitoline slope, where they were visible to the public and invoked during oaths and treaties to ensure mutual consent and protection.[30] Variations in the lists occasionally substituted Dis Pater (god of the underworld) or Liber (god of fertility and wine) for Apollo or Vesta, reflecting regional or contextual emphases, though the core Ennian enumeration remained dominant in state worship. The concept of consentes deities traced back to Etruscan influences, where Arnobius records that the Etruscans identified twelve gods—six male and six female—as consentes and complices, deities who "rose and set together" like celestial bodies, underscoring their interconnected roles in divination and cosmology.[30] These groups held profound significance as guarantors of Roman prosperity and defense, with the Dii Consentes invoked in diplomatic treaties and public vows to bind parties under divine oversight. Annual rites, including lectisternia and processions, perpetuated their cult, reinforcing the idea of divine consensus as a model for political unity and averting discord during crises.[28]Di Flaminales

The Di Flaminales refer to the fifteen principal deities of the Roman pantheon, each served by a dedicated flamen, a specialized priest responsible for their exclusive cult and rituals. These priests formed one of the oldest colleges in Roman religion, emphasizing the worship of major gods through daily sacrifices, festivals, and public ceremonies tied to the Roman calendar. The system underscored the Romans' structured approach to divine appeasement, with flamens performing offerings that maintained cosmic order and state prosperity.[31] Among the Di Flaminales, the three most prominent were the flamines maiores, patrician priests assigned to the Archaic Triad of deities. The Flamen Dialis served Jupiter, the king of the gods, and was subject to the most stringent taboos to preserve ritual purity, including prohibitions against riding horses, touching iron, tying knots in his clothing, viewing corpses or armed men, or leaving the city boundaries overnight; he was also forbidden from seeing the sea, even from a distance, and his wife, the Flaminica Dialis, played an integral role in rituals, with her death necessitating his resignation.[31][32] The Flamen Martialis oversaw Mars, god of war and agriculture, conducting sacrifices during military campaigns and festivals like the Equirria; his taboos were less severe but included similar patrician restrictions on conduct.[31] The Flamen Quirinalis attended to Quirinus, often identified as the deified Romulus, performing rites at the Quirinal Hill and during the Robigalia to protect crops, with duties involving public prayers and processions.[31][33] The twelve flamines minores, typically plebeian and established later in the Republic, served lesser but vital deities associated with fertility, boundaries, and natural forces. These priests emerged by the late Republic, handling specialized festivals and sacrifices, such as the Flamen Floralis leading the Floral Games in honor of Flora or the Flamen Volcanalis overseeing Vulcan's rites during the Volcanalia to avert fires.[34][35] The institution of the flamens originated in the archaic period, traditionally attributed to King Numa Pompilius, who appointed the initial three major flamens to formalize worship of the state's core deities; the full complement of fifteen developed over time through pontifical expansions.[36] By the Imperial era, several flaminate offices had lapsed or become vacant, such as the Flamen Dialis, which remained unoccupied for over seventy years from 87 BCE until its revival under Emperor Julian in the 4th century CE, reflecting shifts toward imperial cults and reduced emphasis on traditional priesthoods.[31] Flamens played a key role in the Roman calendar, marking dies religiosi with sacrifices— for instance, the Flamen Cerialis conducted the Fordicidia for Ceres and Tellus on April 15, invoking earth fertility— and integrating into major festivals like the Consualia or Volturnalia to ensure agricultural and seasonal harmony.[35] The complete list of the fifteen Di Flaminales and their flamens, based on ancient attestations, includes the following:| Flamen | Deity |

|---|---|

| Dialis | Jupiter |

| Martialis | Mars |

| Quirinalis | Quirinus |

| Carmentalis | Carmenta |

| Cerialis | Ceres (with rites for Tellus) |

| Falacer | Falacer |

| Floralis | Flora |

| Furrinalis | Furrina |

| Palatualis | Palatua |

| Pomonalis | Pomona |

| Portunalis | Portunus |

| Volcanalis | Vulcan |

| Volturnalis | Volturnus |

| Consualis | Consus |

| Virbialis | Virbius |

Di Selecti and Other Specialized Groupings

The di selecti, or "selected gods," refer to a category of principal deities in Roman religion identified by the antiquarian Marcus Terentius Varro in his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum, where he enumerates twenty gods distinguished by their temples and prominent roles in public worship. These included Janus, Jupiter, Saturn, the Genius, Mercury, Apollo, Mars, Vulcan, Neptune, Sol, Tellus, Luna, Ceres, Juno, Diana, Minerva, Venus, Vesta, Liber, and Libera, selected for their explicit functions and invocability by name in rituals, contrasting with more obscure indigitamenta.[38] In practice, the concept extended to temporary selections of deities for special vows during military crises, where generals or the Senate chose specific gods to honor in exchange for victory, as seen in Virgil's Aeneid where Evander invokes local Arcadian deities like Hercules alongside Fauns and Nymphs during Aeneas's alliance against the Latins.[39] Historical records from the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE) illustrate this, with vows made to select gods such as Apollo and Proserpina after defeats like Cannae, promising temples or games to secure divine aid amid existential threats. Beyond the di selecti, Roman religion distinguished between di publici, the state-sponsored gods of the civic pantheon whose cults were maintained by magistrates and priests for communal prosperity, and di privati, household deities venerated in domestic rituals by families and individuals.[40] The di publici encompassed major figures like Jupiter Optimus Maximus and Mars, with temples and festivals funded by the res publica to ensure Rome's welfare, while di privati focused on Lares, Penates, and ancestral Manes, honored through private altars and offerings to protect the domus.[40] This division reflected the contractual nature of Roman piety, where public rites reinforced social order and private ones sustained familial bonds, though overlaps occurred in shared practices like the Parentalia festival.[41] Specialized groupings included the di inferi, the chthonic deities of the underworld, invoked to appease the realm of the dead and ensure safe passage for souls.[42] Chief among them were Dis Pater (ruler of the underworld), Proserpina (his consort), and the collective Manes (deified ancestors), worshiped through somber rites like the Feralia to avoid their wrath, distinct from the di superi of the celestial sphere.[42] Archaeological evidence from funerary altars and inscriptions confirms their role in purification rituals, emphasizing euphemistic invocations to maintain harmony with these "gods below."[43] Other context-specific collectives comprised the dii novensiles, a group of nine deities granted authority by Jupiter to wield thunderbolts, symbolizing selective divine power in cosmic order.[44] Their obscure origins link to Etruscan influences, with invocations during storms or oaths, and they were integrated into funerary contexts through the novendiale, a nine-day rite of purification following death to honor the deceased and avert pollution.[44] Similarly, the di termini protected territorial boundaries, embodied primarily by Terminus, the god of limits, whose cult involved annual sacrifices at boundary stones to safeguard property and empire.[45] Ovid describes these rites in the Fasti, where farmers offered cakes and grain to Terminus, underscoring the deity's unyielding nature—even Jupiter yielded a temple corner to him—reflecting Roman emphasis on inviolable borders.[45]Sabine and Early Italic Deities

The integration of Sabine deities into the Roman pantheon is traditionally traced to the legendary synoecism following the abduction of Sabine women by Romulus and the subsequent alliance with King Titus Tatius around 753 BC, a process that facilitated the adoption of several Sabine cults into Roman religious practice.[46] Varro, a scholar of Sabine origin writing in the first century BC, lists key Sabine gods incorporated by the Romans, emphasizing their role in early communal rituals and emphasizing agricultural and protective functions.[46] Among these, Ops emerged as a goddess of abundance and earth fertility, invoked in agricultural cycles and listed in Varro's indigitamenta as a core deity tied to Roman prosperity.[46] Feronia, revered by Sabines for her associations with freedom, wildlife, health, and rural abundance, received worship in extramural sanctuaries near Rome, reflecting her Italic roots in woodland and emancipatory rites.[46] Strenia, a Sabine goddess of physical vigor and strenuous effort, was linked to New Year observances and the bestowal of strength, with her cult possibly influencing private Roman rituals for endurance in labor.[46] Etruscan influences on the Roman pantheon became prominent during the early Republic (c. 509–300 BC), as Rome absorbed Etruscan religious structures, including the Capitoline Triad. Tinia, the Etruscan sky and thunder god equivalent to Jupiter, served as the supreme deity, often depicted wielding lightning bolts and overseeing oaths and justice in Etruscan iconography. Uni, Tinia's consort and counterpart to Juno, embodied marriage, fertility, and state protection, with her cult integrated into Roman practices through shared temple dedications on the Capitoline Hill. Menrva, the Etruscan goddess of wisdom, crafts, medicine, and strategic warfare (analogous to Minerva), contributed to Roman intellectual and martial cults, evidenced by her inclusion in the triad's rituals and Etruscan-influenced augury traditions adopted by Roman priests. This adoption process involved translating Etruscan divine attributes into Latin equivalents, fostering a syncretic framework that elevated Rome's state religion. Other Early Italic deities from regions like Samnium and Falerii further enriched the pantheon through conquest and cultural exchange in the mid-Republic. Angitia, originating from Marsi and Samnite cults near Lake Fucinus, was a goddess of snake-charming, healing, and magic, invoked against poisons and serpents; her worship persisted in Italic enclaves and intersected with Roman narratives of sorceresses like Medea, though she remained peripheral to core Roman temples.[47] Nortia, an Etruscan-Italic deity of fate, destiny, and time from Volscian and Faliscan traditions, was honored in rituals involving nailed inscriptions to fix outcomes, with her attributes partially syncretized into Roman concepts of Fortuna during expansions into central Italy.[48] These figures highlight the pantheon's expansion via evocatio, a Roman ritual to transfer enemy gods, blending local Italic healing and prognostic elements into broader imperial worship. Syncretism of Sabine and Early Italic deities manifested in Roman festivals that preserved pre-urban agricultural and protective rites. The Robigalia, held on April 25 to avert crop blight through dog sacrifice at the Robigo grove, incorporated Italic elements from Sabine and Latin countryside cults, emphasizing communal appeals to avert mildew and ensure harvest vitality as an ancient Italic inheritance. Such observances underscore how ethnic integrations post-753 BC legend not only diversified the pantheon but also embedded Italic rural piety into Rome's civic calendar, promoting unity across conquered territories.[46]Alphabetical List of Deities

A

Abundantia was a Roman goddess embodying prosperity and abundance, particularly in the context of agricultural plenty and wealth. She emerged as a prominent figure in the Imperial cult, symbolizing the benevolence of the emperor and the empire's enduring fertility, often invoked to ensure bountiful harvests and economic stability. Abundantia is frequently depicted in Roman art and coinage holding a cornucopia overflowing with fruits and grains, a motif that underscored her role in promoting material well-being during the late Republic and early Empire.[49][50] Acca Larentia, also known as Acca Larentia, held a revered place in Roman mythology as the mythical nurse who raised the twin founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, after they were abandoned. Deified posthumously, she was venerated as an earth mother figure associated with fertility and the nurturing aspects of the land, reflecting her protective role in the city's foundational legends. Her primary festival, the Larentalia, occurred on December 23, during which Romans honored her with offerings and rituals at her supposed tomb near the Velabrum, emphasizing themes of maternal care and subterranean abundance. Aeternitas personified eternity and permanence in Roman religion, representing the unending duration of the state, the city of Rome, and later the imperial dynasty. Her cult originated in the late Republic, where she was invoked to safeguard the longevity of Roman institutions, and gained heightened significance under the emperors, who linked her to their own perpetual rule and the empire's stability. Aeternitas appeared on coinage and monuments from the Augustan period onward, often shown with symbols like the globe, phoenix, or the heads of Sol and Luna to denote cosmic endurance.[51][52] Aius Locutius, a minor prophetic deity, was honored by the Romans for manifesting as a speaking voice or "talking stone" that warned of the Gallic invasion in 390 BC, alerting the city to impending danger despite initial neglect by officials. This event led to the establishment of a small shrine in his honor on the Capitoline Hill, acknowledging his role as a god of speech and timely revelation in the indigitamenta tradition of specialized divine functions. Though obscure, Aius Locutius exemplified the Roman tendency to deify specific omens or interventions during crises.[53][54] Angerona served as the goddess of silence and the safeguarding of secrets in Roman worship, believed to protect the hidden name of Rome, which was thought to hold the city's mystical power against enemies. Her festival, the Angeronalia, took place on December 21, involving rituals that sought her aid in alleviating ailments like jaw pain and sore throats, symbolized by her image with a bound mouth or finger to lips. Representations of Angerona, such as ancient statues, emphasized her role in enforcing discretion and averting harm through quietude.[55] Anna Perenna embodied the cyclical passage of the year and the attainment of a long life, functioning as a deity of renewal and the annual return of seasons in Roman religious practice. Her festival on March 15 featured communal picnics and offerings along the Tiber River, where participants reclined and enjoyed makeshift tents, possibly reflecting Sabine influences from early Italic traditions. Anna Perenna's worship highlighted themes of longevity and the joyous progression of time, tying into broader Roman concerns with prosperity across the calendar year.[56][57] Annona represented the personification of Rome's grain supply, crucial for the sustenance of the urban populace and tied to the state's efforts in provisioning the plebeians. Temples dedicated to her date from the third century BC, such as the one near the Porta Capena, where she was honored for ensuring stable food distribution amid potential shortages. Annona's iconography on coins and reliefs often showed her with a cornucopia and modius, underscoring her connection to imperial welfare policies and agricultural imports from provinces like Egypt.[58][59] Apollo, adopted into Roman religion from Greek traditions during the mid-fifth century BC, presided over prophecy, music, healing, and the arts, becoming a major deity by the Republic's height. His temple on the Palatine Hill, dedicated in 433 BC following a plague, marked his integration as a protector against disease and a patron of civic order, later elevated by Augustus as a symbol of imperial renewal. Apollo's worship involved ludi Apollinares games and oracular consultations, reflecting his enduring influence in both public and private Roman life.[60][61] Astraea stood as the goddess of justice and innocence, mythically departing from earth at the end of the Golden Age to become the constellation Virgo, signaling humanity's descent into corruption during the Iron Age. In Roman lore, drawn from Hesiodic and Ovidian traditions, she embodied the ideal of a pure, equitable world lost to vice, with her return anticipated in prophetic visions of renewal. Astraea's celestial association reinforced her role as a distant arbiter of moral order.[62] Aurora personified the dawn in Roman mythology, depicted as a winged goddess driving a chariot across the sky to herald the sun's arrival, sister to Sol and Luna. Her daily renewal symbolized the eternal cycle of light overcoming darkness, often portrayed in art with rosy fingers scattering dew and opening the gates of heaven. Aurora's narratives, including her abduction of mortals like Tithonus, highlighted themes of beauty, transience, and the inexorable march of time.[63][64]B

Bacchus was the Roman god of wine, agriculture, fertility, ecstasy, and theater, often identified with the Greek Dionysus. His worship emphasized the transformative power of wine in both agricultural cycles and ritual celebrations, promoting themes of liberation and communal joy. The Liberalia festival, held on March 17, honored Bacchus (also known as Liber Pater) with offerings of cakes and wine, marking the transition to spring planting and the freeing of young men from paternal authority. The Bacchanalia, more ecstatic rites introduced from southern Italy around 200 BC, involved music, dance, and communal intoxication but were suppressed by the Senate in 186 BC due to concerns over moral corruption and political subversion, resulting in thousands of arrests and executions as documented by Livy. Bellona served as the Roman goddess of war, embodying violent conflict, destruction, and military fervor, frequently depicted armed with a sword and shield. Her cult originated in early Italic traditions and was integral to Roman military religion, where she accompanied Mars in battle. The Temple of Bellona, located in the Campus Martius outside the pomerium, functioned as a key site for senatorial declarations of war and reception of foreign ambassadors, underscoring her role in state decisions on conflict. Priests of Bellona, known as Bellonarii, performed frenzied rituals involving self-flagellation and prophecy during wartime, heightening the goddess's association with battle madness; she was also invoked in evocatio ceremonies to lure enemy deities to the Roman side, as seen in practices during sieges.[65][66] Bona Dea, meaning "the Good Goddess," was a secretive Roman deity linked to fertility, chastity, healing, and the protection of the Roman state, particularly revered by women as a guardian of matronly virtues. Her cult was exclusively for women, with men strictly forbidden from participation or even viewing the rites, reflecting ancient taboos on gender segregation in sacred spaces; this exclusivity famously led to the scandal involving Publius Clodius Pulcher in 62 BC, who disguised himself to infiltrate the festival at Julius Caesar's house. The primary festival occurred on May 1 at the home of the presiding magistrate, involving nocturnal sacrifices, music, and wine disguised as milk to maintain ritual purity, overseen by the Vestal Virgins. Bona Dea was sometimes identified with Fauna, daughter of Faunus, or Terra, the earth goddess, symbolizing her ties to natural fertility and subterranean forces.[67] Borvo (also Bormo) was a Gaulish healing god adopted into Roman worship, particularly at thermal springs where his cult emphasized therapeutic waters for ailments like rheumatism and skin conditions. Syncretized with Apollo as Apollo Borvo, he represented the bubbling, boiling vitality of mineral springs, with inscriptions attesting to dedications at sites like Aix-les-Bains and Barbotan-les-Thermes in Gaul. Worship involved offerings at sanctuaries near hot springs, blending Celtic reverence for natural healing loci with Roman imperial cults of health and renewal.C

Cacus was a fire-breathing giant and monstrous figure in Roman mythology, depicted as the son of the god Vulcan and inhabitant of a cave on the Aventine Hill. According to Virgil's account in the Aeneid, Cacus terrorized the local herds by stealing cattle from the hero Hercules, dragging the animals backward into his lair to conceal his theft, but Hercules discovered the ruse, blocked the cave exits, and strangled the giant in retaliation, symbolizing the triumph over destructive fire and chaos. This myth, rooted in earlier Italic traditions, underscores themes of order prevailing against primal disorder, with Cacus representing volcanic or infernal forces akin to his father's domain.[68] Cardea, a minor Roman goddess associated with door hinges and thresholds, was invoked for protection against evil spirits and to safeguard children from nocturnal threats like witches. In Ovid's Fasti, she originates as a nymph who catches the eye of Janus; to escape his advances, she pledges fidelity but receives a whitethorn branch (hawthorn) as a magical token, empowering her to open and close doors while warding off harm with its purifying properties. As part of the indigitamenta—the detailed Roman list of divine functions—Cardea embodied the liminal space of the household entrance, ensuring security and transition.[69] Castor and Pollux, the twin gods known as the Dioscuri, were patrons of cavalry, hospitality, and equestrian endeavors in Roman religion, often appearing as youthful horsemen aiding warriors in battle. Their cult gained prominence after the Battle of Lake Regillus in 496 BCE, where they reportedly manifested to announce Roman victory over the Latin league, leading to the dedication of their temple in the Forum in 484 BCE by Aulus Postumius. The annual festival on July 15 commemorated this event with the Transvectio equitum, a procession of knights reviewing their ranks, reinforcing their role as protectors of Rome's military elite. Ceres, the Roman goddess of grain, agriculture, and fertility, presided over the growth and harvest of crops, serving as a central figure in plebeian worship and food security. Her temple on the Aventine Hill, dedicated in 493 BCE amid tensions between patricians and plebeians, formed the core of the Aventine triad alongside Liber and Libera, establishing a distinct plebeian cult space influenced by Greek Eleusinian mysteries. The Cerealia festival in April featured games and rituals to ensure bountiful yields, with her myths emphasizing maternal protection of the earth's bounty, as seen in Ovid's accounts of her search for Proserpina. Cloacina, the goddess of the sewers and purification, oversaw the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's ancient drainage system engineered under the kings, symbolizing civic cleanliness and renewal. Her shrine, located at the point where the sacred spear of Titus Tatius met Romulus's blood during their reconciliation, was later rededicated as Venus Cloacina, blending her chthonic role with Venus's purifying aspects after the Sabine-Roman union. This site, adorned with a statue and offerings, highlighted the mythological foundation of Rome's infrastructure as a divine gift for urban health. Consus, an archaic god of stored grain and hidden counsel, represented the underground storage of harvests and strategic secrecy in agriculture and warfare.[70] His festivals, the Consualia on August 21 and December 15, involved unveiling his altar in the Circus Maximus for sacrifices and races of horses and mules, linking him to the founding myth of the Rape of the Sabine Women, where Romulus used his games to lure the Sabines.[70] These events, described by Ovid, emphasized fertility and equine vitality, with the altar's concealment underscoring Consus's chthonic, protective nature.[71] Cupid, the god of desire and erotic love, was commonly portrayed as the winged son of Venus, armed with a bow and arrows that ignited passion in gods and mortals alike. In classical texts like Apuleius's Metamorphoses, he emerges as a central figure in the tale of Cupid and Psyche, where his forbidden love for the mortal Psyche defies Venus's jealousy, evolving from the Greek Eros into a symbol of uncontrollable longing. Ovid's Ars Amatoria further depicts him as a mischievous archer, whose influence permeates Roman poetry on affection and seduction.D