Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

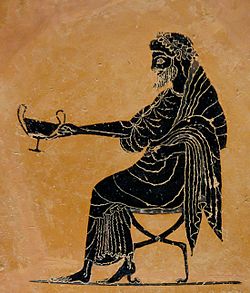

Dionysus

View on Wikipedia

| DionysusBacchus | |

|---|---|

| Member of the Twelve Olympians | |

Second-century Roman statue of Dionysus, after a Hellenistic model (ex-coll. Cardinal Richelieu, Louvre)[1] | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Animals | Bull, panther, tiger or lion, goat, snake, leopard |

| Symbol | Thyrsus, grapevine, ivy, theatrical masks, phallus |

| Festivals | Bacchanalia (Roman), Dionysia |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Zeus and Semele |

| Spouse | Ariadne |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman | Bacchus |

| Egyptian | Osiris |

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (/daɪ.əˈnaɪ.səs/ ⓘ; Ancient Greek: Διόνυσος Diónysos) is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre.[2][3] He was also known as Bacchus (/ˈbækəs/ or /ˈbɑːkəs/; Ancient Greek: Βάκχος Bacchos) by the Greeks (a name later adopted by the Romans) for a frenzy he is said to induce called baccheia.[4] His wine, music, and ecstatic dance were considered to free his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subvert the oppressive restraints of the powerful.[5] His thyrsus, a fennel-stem sceptre, sometimes wound with ivy and dripping with honey, is both a beneficent wand and a weapon used to destroy those who oppose his cult and the freedoms he represents.[6] Those who partake of his mysteries are believed to become possessed and empowered by the god himself.[7]

His origins are uncertain, and his cults took many forms; some are described by ancient sources as Thracian, others as Greek.[8][9][10] In Orphism, he was variously a son of Zeus and Persephone; a chthonic or underworld aspect of Zeus; or the twice-born son of Zeus and the mortal Semele. The Eleusinian Mysteries identify him with Iacchus, the son or husband of Demeter. Most accounts say he was born in Thrace, traveled abroad, and arrived in Greece as a foreigner. His attribute of "foreignness" as an arriving outsider-god may be inherent and essential to his cults, as he is a god of epiphany, sometimes called "the god who comes".[11]

Wine was a religious focus in the cult of Dionysus and was his earthly incarnation.[12] Wine could ease suffering, bring joy, and inspire divine madness.[13] Festivals of Dionysus included the performance of sacred dramas enacting his myths, the initial driving force behind the development of theatre in Western culture.[14] The cult of Dionysus is also a "cult of the souls"; his maenads feed the dead through blood-offerings, and he acts as a divine communicant between the living and the dead.[15] He is sometimes categorised as a dying-and-rising god.[16] Scholars note parallels between Dionysus and Jesus as dying-and-rising gods, though key differences and contexts complicate direct comparisons.

Romans identified Bacchus with their own Liber Pater, "the free Father" of the Liberalia festival, patron of viniculture, wine and male fertility, and guardian of the traditions, rituals and freedoms attached to coming of age and citizenship, but the Roman state treated independent, popular festivals of Bacchus (Bacchanalia) as subversive, partly because their free mixing of classes and genders transgressed traditional social and moral constraints. Celebration of the Bacchanalia was made a capital offence, except in the toned-down forms and greatly diminished congregations approved and supervised by the State. Festivals of Bacchus were merged with those of Liber and Dionysus.

Name

[edit]Etymology

[edit]

The dio- prefix in Ancient Greek Διόνυσος (Diónūsos; [di.ó.nyː.sos]) has been associated since antiquity with Zeus (genitive Dios), and the variants of the name seem to point to an original *Dios-nysos.[17] The earliest attestation is the Mycenaean Greek dative form 𐀇𐀺𐀝𐀰 (di-wo-nu-so),[18][17] featured on two tablets that had been found at Mycenaean Pylos and dated to the twelfth or thirteenth century BC. At that time, there could be no certainty on whether this was indeed a theonym,[19][20] but the 1989–90 Greek-Swedish Excavations at Kastelli Hill, Chania, unearthed, inter alia, four artefacts bearing Linear B inscriptions; among them, the inscription on item KH Gq 5 is thought to confirm Dionysus's early worship.[21] In Mycenaean Greek the form of Zeus is di-wo.[22] The second element -nūsos is of unknown origin.[17] It is perhaps associated with Mount Nysa, the birthplace of the god in Greek mythology, where he was nursed by nymphs (the Nysiads),[23] although Pherecydes of Syros had postulated nũsa as an archaic word for "tree" by the sixth century BC.[24][25] On a vase of Sophilos the Nysiads are named νύσαι (nusae).[26] Kretschmer asserted that νύση (nusē) is a Thracian word that has the same meaning as νύμφη (nýmphē), a word similar with νυός (nuos) (daughter in law, or bride, I-E *snusós, Sanskr. snusā).[27] He suggested that the male form is νῦσος (nūsos) and this would make Dionysus the "son of Zeus".[26] Jane Ellen Harrison believed that the name Dionysus means "young Zeus".[28] Robert S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name, since all attempts to find an Indo-European etymology are doubtful.[18][17]

Meaning and variants

[edit]Later variants include Dionūsos and Diōnūsos in Boeotia; Dien(n)ūsos in Thessaly; Deonūsos and Deunūsos in Ionia; and Dinnūsos in Aeolia, besides other variants. A Dio- prefix is found in other names, such as that of the Dioscures, and may derive from Dios, the genitive of the name of Zeus.[29]

Nonnus, in his Dionysiaca, writes that the name Dionysus means "Zeus-limp" and that Hermes named the new born Dionysus this, "because Zeus while he carried his burden lifted one foot with a limp from the weight of his thigh, and nysos in Syracusan language means limping".[30] In his note to these lines, W. H. D. Rouse writes "It need hardly be said that these etymologies are wrong".[30] The Suda, a Byzantine encyclopedia based on classical sources, states that Dionysus was so named "from accomplishing [διανύειν] for each of those who live the wild life. Or from providing [διανοεῖν] everything for those who live the wild life."[31]

Origins

[edit]

Academics in the nineteenth century, using study of philology and comparative mythology, often regarded Dionysus as a foreign deity who was only reluctantly accepted into the standard Greek pantheon at a relatively late date, based on his myths which often involve this theme—a god who spends much of his time on earth abroad, and struggles for acceptance when he returns to Greece. However, more recent evidence has shown that Dionysus was in fact one of the earliest gods attested in mainland Greek culture.[13] The earliest written records of Dionysus worship come from Mycenaean Greece, specifically in and around the Palace of Nestor in Pylos, dated to around 1300 BC.[32] The details of any religion surrounding Dionysus in this period are scant, and most evidence comes in the form only of his name, written as di-wo-nu-su-jo ("Dionysoio" = 'of Dionysus') in Linear B, preserved on fragments of clay tablets that indicate a connection to offerings or payments of wine, which was described as being "of Dionysus". References have also been uncovered to "women of Oinoa", the "place of wine", who may correspond to the Dionysian women of later periods.[32]

Other Mycenaean records from Pylos record the worship of a god named Eleuther, who was the son of Zeus, and to whom oxen were sacrificed. The link to both Zeus and oxen, as well as etymological links between the name Eleuther or Eleutheros with the Latin name Liber Pater, indicates that this may have been another name for Dionysus. According to Károly Kerényi, these clues suggest that even in the thirteenth century BC, the core religion of Dionysus was in place, as were his important myths. At Knossos in Minoan Crete, men were often given the name "Pentheus", who is a figure in later Dionysian myth and which also means "suffering". Kerényi argued that to give such a name to one's child implies a strong religious connection, potentially not the separate character of Pentheus who suffers at the hands of Dionysus's followers in later myths, but as an epithet of Dionysus himself, whose mythology describes a god who must endure suffering before triumphing over it. According to Kerényi, the title of "man who suffers" likely originally referred to the god himself, only being applied to distinct characters as the myth developed.[32]

The oldest known image of Dionysus accompanied by his name is found on a dinos by the Attic potter Sophilos around 570 BC and is located in the British Museum.[33] By the seventh century, iconography found on pottery shows that Dionysus was already worshiped as more than just a god associated with wine. He was associated with weddings, death, sacrifice, and sexuality, and his retinue of satyrs and dancers was already established. A common theme in these early depictions was the metamorphosis, at the hand of the god, of his followers into hybrid creatures, usually represented by both tame and wild satyrs, representing the transition from civilised life back to nature as a means of escape.[13]

A Mycenaean variant of Bacchus was thought to have been "a divine child" abandoned by his mother and eventually raised by "nymphs, goddesses, or even animals."[34]

Epithets

[edit]

Dionysus was variably known with the following epithets:

Acratophorus, Ἀκρατοφόρος ("giver of unmixed wine"), at Phigaleia in Arcadia.[35]

Adoneus, a rare archaism in Roman literature, a Latinised form of Adonis, used as epithet for Bacchus.[37]

Aegobolus Αἰγοβόλος ("goat-shooter") at Potniae, in Boeotia.[38]

Aesymnetes Αἰσυμνήτης ("ruler" or "lord") at Aroë and Patrae in Achaea.

Agrios Ἄγριος ("wild"), in Macedonia.

Androgynos Ἀνδρόγυνος ("androgynous"), refers to the god assuming both the active, masculine and passive, feminine role during intercourse with male lovers.[39][40]

Anthroporraistes, Ἀνθρωπορραίστης ("man-destroyer"), a title of Dionysus at Tenedos.[41]

Bassareus, Βασσαρεύς a Thracian name for Dionysus, which derives from bassaris or "fox-skin", which item was worn by his cultists in their mysteries.[42][43]

Bougenes, Βουγενής or Βοηγενής ("borne by a cow"), in the Mysteries of Lerna.[44][45]

Braetes, Βραίτης ("related to beer") at Thrace.[46]

Brisaeus, Βρισαῖος, a surname of Dionysus, derived either from mount Brisa in Lesbos or from a nymph Brisa, who was said to have brought up the god.[47]

Briseus, Βρῑσεύς ("he who prevails") in Smyrna.[48][49]

Bromios Βρόμιος ("roaring", as of the wind, primarily relating to the central death/resurrection element of the myth,[50] but also the god's transformations into lion and bull,[51] and the boisterousness of those who drink alcohol. Also cognate with the "roar of thunder", which refers to Dionysus's father, Zeus "the thunderer".[52])

Choiropsalas χοιροψάλας ("pig-plucker": Greek χοῖρος = "pig", also used as a slang term for the female genitalia). A reference to Dionysus's role as a fertility deity.[53][54]

Chthonios Χθόνιος ("the subterranean")[55]

Cistophorus Κιστοφόρος ("basket-bearer, ivy-bearer"), Alludes To baskets being sacred to the god.[56][57]

Dasyllius Δασύλλιος ("frequenting the woods") at Megara.[58]

Dimetor Διμήτωρ ("twice-born") Refers to Dionysus's two births.[56][59][60][61]

Dendrites Δενδρίτης ("of the trees"), as a fertility god.[62]

Dithyrambos, Διθύραμβος used at his festivals, referring to his premature birth.

Eleuthereus Ἐλευθερεύς ("of Eleutherae").[63]

Endendros ("he in the tree").[64]

Enorches ("with balls"),[65] with reference to his fertility, or "in the testicles" in reference to Zeus's sewing the baby Dionysus "into his thigh", understood to mean his testicles).[66] Used at Samos according to Hesyichius,[67] or Lesbos according to the scholiast on Lycophron's Alexandra.[68]

Eridromos ("good-running"), in Nonnus's Dionysiaca.[69]

Erikryptos Ἐρίκρυπτος ("completely hidden"), in Macedonia.

Euaster (Εὐαστήρ), from the cry "euae".[70]

Euius (Euios), from the cry "euae" in lyric passages, and in Euripides's play, The Bacchae.[71]

Iacchus, Ἴακχος a possible epithet of Dionysus, associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries. In Eleusis, he is known as a son of Zeus and Demeter. The name "Iacchus" may come from the Ιακχος (Iakchos), a hymn sung in honor of Dionysus.

Indoletes, Ἰνδολέτης, meaning slayer/killer of Indians. Due to his campaign against the Indians.[72]

Isodaetes, Ισοδαίτης, meaning "he who distributes equal portions", cult epithet also shared with Helios.[73]

Kemilius, Κεμήλιος (kemas: "young deer, pricket").[74][75]

Liknites ("he of the winnowing fan"), as a fertility god connected with mystery religions. A winnowing fan was used to separate the chaff from the grain.

Lenaius, Ληναῖος ("god of the wine-press") [76]

Lyaeus, or Lyaios (Λυαῖος, "deliverer", literally "loosener"), one who releases from care and anxiety.[77]

Lysius, Λύσιος ("delivering, releasing"). At Thebes there was a temple of Dionysus Lysius.[78][79][80]

Melanaigis Μελάναιγις ("of the black goatskin") at the Apaturia festival.

Morychus Μόρυχος ("smeared"); in Sicily, because his icon was smeared with wine lees at the vintage.[81][82]

Mystes Μύστης ("of the mysteries") at Korythio in Arcadia.[83][84]

Nysian Nύσιος, according to Philostratus, he was called like this by the ancient Indians.[85] Most probably, because according to legend he founded the city of Nysa.[86][87][88]

Oeneus, Οἰνεύς ("wine-dark") as god of the wine press.[89][90]

Omadios, Ωμάδιος ("eating raw flesh"[91]); Eusebius writes in Preparation for the Gospel that Euelpis of Carystus states that in Chios and Tenedos they did human sacrifice to Dionysus Omadios.[92][93][94]

Patroos, Πατρῷος ("paternal") at Megara.[58]

Phallen , Φαλλήν (probably "related to the phallus"), at Lesbos.[95][96]

Phleus ("related to the bloοm of a plant").[97][98][99]

Pseudanor, Ψευδάνωρ (literally "false man", referring to his feminine qualities), in Macedonia.

Pericionius, Περικιόνιος ("climbing the column (ivy)", a name of Dionysus at Thebes.[100]

Semeleios[101] (Semeleius or Semeleus),[102] an obscure epithet meaning 'He of the Earth', 'son of Semele'.[103][104][105][106] Also appears in the expression Semeleios Iakchus plutodotas ("Son of Semele, Iakchus, wealth-giver").[107]

Skyllitas, Σκυλλίτας ("related to the vine-branch") at Kos.[108][109]

Sykites, Συκίτης ("related to figs"), at Laconia.[110]

Taurophagus, Ταυροφάγος ("bull eating").[111]

Tauros Ταῦρος ("a bull"), occurs as a surname of Dionysus.[112]

Theoinus, Θέοινος (wine-god of a festival in Attica).[113][114][115]

Τhyiοn, Θυίων ("from the festival of Dionysus 'Thyia' (Θυῐα) at Elis").[116][117]

Thyllophorus, Θυλλοφόρος ("bearing leaves"), at Kos.[118][119]

In the Greek pantheon, Dionysus (along with Zeus) absorbs the role of Sabazios, a Thracian/Phrygian deity. In the Roman pantheon, Sabazius became an alternative name for Bacchus.[120]

Worship and festivals in Greece

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

The worship of Dionysus had become firmly established by the seventh century BC.[121] He may have been worshiped as early as c. 1500–1100 BC by Mycenaean Greeks;[122][21] and traces of Dionysian-type cult have also been found in ancient Minoan Crete.[32]

Dionysia

[edit]The Dionysia, Haloa, Ascolia and Lenaia festivals were dedicated to Dionysus.[123] The Rural Dionysia (or Lesser Dionysia) was one of the oldest festivals dedicated to Dionysus, begun in Attica, and probably celebrated the cultivation of wines. It was held during the winter month of Poseideon (the time surrounding the winter solstice, modern December or January). The Rural Dionysia centered on a procession, during which participants carried phalluses, long loaves of bread, jars of water and wine as well as other offerings, and young girls carried baskets. The procession was followed by a series of dramatic performances and drama competitions.[124]

The City Dionysia (or Greater Dionysia) took place in urban centers such as Athens and Eleusis, and was a later development, probably beginning during the sixth century BC. Held three months after the Rural Dionysia, the Greater festival fell near the spring equinox in the month of Elaphebolion (modern March or April). The procession of the City Dionysia was similar to that of the rural celebrations, but more elaborate, and led by participants carrying a wooden statue of Dionysus, and including sacrificial bulls and ornately dressed choruses. The dramatic competitions of the Greater Dionysia also featured more noteworthy poets and playwrights, and prizes for both dramatists and actors in multiple categories.[124][14]

Anthesteria

[edit]The Anthesteria (Ἀνθεστήρια) was an Athenian festival that celebrated the beginning of spring. It spanned three days: Pithoigia (Πιθοίγια, "Jar-Opening"), Choes (Χοαί, "The Pouring") and Chythroi (Χύτροι "The Pots").[125] It was said the dead arose from the underworld during the span of the festival. Along with the souls of the dead, the Keres also wandered through the city and had to be banished when the festival ended.[126] On the first day, Wine vats were opened.[127] The wine was opened and mixed in honour of the god.[128] The rooms and the drinking vessels were adorned with flowers along with children over three years of age.[125]

On the second day, a solemn ritual for Dionysus occurred along with drinking. People dressed up, sometimes as members of Dionysus's entourage, and visited others. Choes was also the occasion of a solemn and secret ceremony in one of the sanctuaries of Dionysus in the Lenaeum, which was closed for the rest of the year. The basilissa (or basilinna), wife of the basileus, underwent a symbolic ceremonial marriage to the god, possibly representing a Hieros gamos. The basilissa was assisted by fourteen Athenian matrons (called Gerarai) who were chosen by the basileus and sworn to secrecy.[125][129]

The last day was dedicated to the dead. Offerings were also offered to Hermes, due to his connection to the underworld. It was considered a day of merrymaking.[125] Some poured Libations on the tombs of deceased relatives. Chythroi ended with a ritual cry intended to order the souls of the dead to return to the underworld.[129] Keres were also banished from the festival on the last day.[126]

To protect themselves from evil, people chewed leaves of whitethorn and smeared their doors with tar to protect themselves. The festival also allowed servants and slaves to participate in the festivities.[125][126]

Bacchic Mysteries

[edit]

The central religious cult of Dionysus is known as the Bacchic or Dionysian Mysteries. The exact origin of this religion is unknown, though Orpheus was said to have invented the mysteries of Dionysus.[130] Evidence suggests that many sources and rituals typically considered to be part of the similar Orphic Mysteries actually belong to Dionysian mysteries.[13] Some scholars have suggested that, additionally, there is no difference between the Dionysian mysteries and the mysteries of Persephone, but that these were all facets of the same mystery religion, and that Dionysus and Persephone both had important roles in it.[13][131] Previously considered to have been a primarily rural and fringe part of Greek religion, the major urban center of Athens played an important role in the development and spread of the Bacchic mysteries.[13]

The Bacchic mysteries served an important role in creating ritual traditions for transitions in people's lives; originally primarily for men and male sexuality, but later also created space for ritualising women's changing roles and celebrating changes of status in a woman's life. This was often symbolised by a meeting with the gods who rule over death and change, such as Hades and Persephone, but also with Dionysus's mother Semele, who probably served a role related to initiation into the mysteries.[13]

The religion of Dionysus often included rituals involving the sacrifice of goats or bulls, and at least some participants and dancers wore wooden masks associated with the god. In some instances, records show the god participating in the ritual via a masked and clothed pillar, pole, or tree, while his worshipers eat bread and drink wine. The significance of masks and goats to the worship of Dionysus seems to date back to the earliest days of his worship, and these symbols have been found together at a Minoan tomb near Phaistos in Crete.[32]

Eleusinian Mysteries

[edit]

As early as the fifth century BC, Dionysus became identified with Iacchus, a minor deity from the tradition of the Eleusinian Mysteries.[132] This association may have arisen because of the homophony of the names Iacchus and Bacchus. Two black-figure lekythoi (c. 500 BC), possibly represent the earliest evidence for such an association. The nearly-identical vases, one in Berlin,[133] the other in Rome,[134] depict Dionysus, along with the inscription IAKXNE, a possible miswriting of IAKXE.[135] More early evidence can be found in the works of the fifth-century BC Athenian tragedians Sophocles and Euripides.[136] In Sophocles's Antigone (c. 441 BC), an ode to Dionysus begins by addressing Dionysus as the "God of many names" (πολυώνυμε), who rules over the glens of Demeter's Eleusis, and ends by identifying him with "Iacchus the Giver", who leads "the chorus of the stars whose breath is fire" and whose "attendant Thyiads" dance in "night-long frenzy".[137] And in a fragment from a lost play, Sophocles describes Nysa, Dionysus's traditional place of nurture: "From here I caught sight of Nysa, haunt of Bacchus, famed among mortals, which Iacchus of the bull's horns counts as his beloved nurse".[138] In Euripides's Bacchae (c. 405 BC), a messenger, describing the Bacchic revelries on mount Cithaeron, associates Iacchus with Bromius, another of the names of Dionysus, saying, they "began to wave the thyrsos ... calling on Iacchus, the son of Zeus, Bromius, with united voice."[139]

An inscription found on a stone stele (c. 340 BC), found at Delphi, contains a paean to Dionysus, which describes his travels.[140] From Thebes, where he was born, he first went to Delphi where he displayed his "starry body", and with "Delphian girls" took his "place on the folds of Parnassus",[141] then next to Eleusis, where he is called "Iacchus":

- And in your hand brandishing your night-

- lighting flame, with god-possessed frenzy

- you went to the vales of Eleusis

- ...

- where the whole people of Hellas'

- land, alongside your own native witnesses

- of the holy mysteries, calls upon you

- as Iacchus: for mortals from their pains

- you have opened a haven without toils.[142]

Strabo, says that Greeks "give the name 'Iacchus' not only to Dionysus but also to the leader-in-chief of the mysteries".[143] In particular, Iacchus was identified with the Orphic Dionysus, who was a son of Persephone.[144] Sophocles mentions "Iacchus of the bull's horns", and according to the first-century BC historian Diodorus Siculus, it was this older Dionysus who was represented in paintings and sculptures with horns, because he "excelled in sagacity and was the first to attempt the yoking of oxen and by their aid to effect the sowing of the seed".[145] Arrian, the second-century Greek historian, wrote that it was to this Dionysus, the son of Zeus and Persephone, "not the Theban Dionysus, that the mystic chant 'Iacchus' is sung".[146] The second-century poet Lucian also referred to the "dismemberment of Iacchus".[147]

The fourth- or fifth-century poet Nonnus associated the name Iacchus with the "third" Dionysus. He described the Athenian celebrations given to the first Dionysus Zagreus, son of Persephone, the second Dionysus Bromios, son of Semele, and the third Dionysus Iacchus:

- They [the Athenians] honoured him as a god next after the son of Persephone, and after Semele's son; they established sacrifices for Dionysos late born and Dionysos first born, and third they chanted a new hymn for Iacchos. In these three celebrations Athens held high revel; in the dance lately made, the Athenians beat the step in honour of Zagreus and Bromios and Iacchos all together.[148]

By some accounts, Iacchus was the husband of Demeter.[149] Several other sources identify Iacchus as Demeter's son.[150] The earliest such source, a fourth-century BC vase fragment at Oxford, shows Demeter holding the child Dionysus on her lap.[151] By the first-century BC, Demeter suckling Iacchus had become such a common motif, that the Latin poet Lucretius could use it as an apparently recognisable example of a lover's euphemism.[152] A scholiast on the second-century AD Aristides, explicitly names Demeter as Iacchus's mother.[153]

Orphism

[edit]

In the Orphic tradition, the "first Dionysus" was the son of Zeus and Persephone, and was dismembered by the Titans before being reborn.[154] Dionysus was the patron god of the Orphics, who they connected to death and immortality, and he symbolised the one who guides the process of reincarnation.[155]

This Orphic Dionysus is sometimes referred to with the alternate name Zagreus (Ancient Greek: Ζαγρεύς). The earliest mentions of this name in literature describe him as a partner of Gaia and call him the highest god. Aeschylus linked Zagreus with Hades, as either Hades's son or Hades himself.[156] Noting "Hades' identity as Zeus' katachthonios alter ego", Timothy Gantz thought it likely that Zagreus, originally, perhaps, the son of Hades and Persephone, later merged with the Orphic Dionysus, the son of Zeus and Persephone.[157] However, no known Orphic sources use the name "Zagreus" to refer to the Orphic Dionysus. It is possible that the association between the two was known by the third century BC, when the poet Callimachus may have written about it in a now-lost source.[158] Callimachus, as well as his contemporary Euphorion, told the story of the dismemberment of the infant Dionysus,[159] and Byzantine sources quote Callimachus as referring to the birth of a "Dionysos Zagreus", explaining that Zagreus was the poets' name for the chthonic aspect of Dionysus.[160] The earliest definitive reference to the belief that Zagreus is another name for the Orphic Dionysus is found in the late first century writings of Plutarch.[161] The fifth century Greek poet Nonnus's Dionysiaca tells the story of this Orphic Dionysus, in which Nonnus calls him the "older Dionysos ... illfated Zagreus",[162] "Zagreus the horned baby",[163] "Zagreus, the first Dionysos",[164] "Zagreus the ancient Dionysos",[165] and "Dionysos Zagreus".[166]

Worship and festivals in Rome

[edit]Bacchus was most often known by that name in Rome and other locales in the Republic and Empire, although many "often called him Dionysus."[167]

Liber and importation to Rome

[edit]

The mystery cult of Bacchus was brought to Rome from the Greek culture of southern Italy or by way of Greek-influenced Etruria. It was established around 200 BC in the Aventine grove of Stimula by a priestess from Campania, near the temple where Liber Pater ("the Free Father") had a State-sanctioned, popular cult. Liber was a native Roman god of wine, fertility, and prophecy, patron of Rome's plebeians (citizen-commoners), and one of the members of the Aventine Triad, along with his mother Ceres and sister or consort Libera. A temple to the Triad was erected on the Aventine Hill in 493 BC, along with the institution of celebrating the festival of Liberalia. The worship of the Triad gradually took on more and more Greek influence, and by 205 BC, Liber and Libera had been formally identified with Bacchus and Proserpina.[168] Liber was often interchangeably identified with Dionysus and his mythology, though this identification was not universally accepted.[169] Cicero insisted on the "non-identity of Liber and Dionysus" and described Liber and Libera as children of Ceres.[170]

Liber, like his Aventine companions, carried various aspects of his older cults into official Roman religion. He protected various aspects of agriculture and fertility, including the vine and the "soft seed" of its grapes, wine and wine vessels, and male fertility and virility.[170] Pliny called Liber "the first to establish the practice of buying and selling; he also invented the diadem, the emblem of royalty, and the triumphal procession."[171] Roman mosaics and sarcophagi attest to various representations of a Dionysus-like exotic triumphal procession. In Roman and Greek literary sources from the late Republic and Imperial era, several notable triumphs feature similar, distinctively "Bacchic" processional elements, recalling the supposedly historic "Triumph of Liber".[172]

Liber and Dionysus may have had a connection that predated Classical Greece and Rome, in the form of the Mycenaean god Eleutheros, who shared the lineage and iconography of Dionysus but whose name has the same meaning as Liber.[32] Before the importation of the Greek cults, Liber was already strongly associated with Bacchic symbols and values, including wine and uninhibited freedom, as well as the subversion of the powerful. Several depictions from the late Republic era feature processions, depicting the "Triumph of Liber".[172]

Bacchanalia

[edit]

In Rome, the most well-known festivals of Bacchus were the Bacchanalia, based on the earlier Greek Dionysia festivals. These Bacchic rituals were said to have included omophagic practices, such as pulling live animals apart and eating the whole of them raw. This practice served not only as a reenactment of the infant death and rebirth of Bacchus, but also as a means by which Bacchic practitioners produced "enthusiasm": etymologically, to let a god enter the practitioner's body or to have her become one with Bacchus.[173][174]

In Livy's account (late 1st century BC), the Bacchic mysteries were a novelty at Rome; originally restricted to women and held only three times a year, they were corrupted by an Etruscan-Greek version, and thereafter drunken, disinhibited men and women of all ages and social classes cavorted in a sexual free-for-all five times a month. Livy relates their various outrages against Rome's civil and religious laws and traditional morality (mos maiorum); a secretive, subversive and potentially revolutionary counter-culture. Livy's sources, and his own account of the cult, probably drew heavily on the Roman dramatic genre known as "Satyr plays", based on Greek originals.[175][176] The cult was suppressed by the State with great ferocity; of the 7,000 arrested, most were executed. Modern scholarship treats much of Livy's account with skepticism; more certainly, a Senatorial edict, the Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus (186 BC) was distributed throughout Roman and allied Italy. It banned the former Bacchic cult organisations. Each meeting must seek prior senatorial approval through a praetor. No more than three women and two men were allowed at any one meeting, and those who defied the edict risked the death penalty.

Bacchus was conscripted into the official Roman pantheon as an aspect of Liber, and his festival was inserted into the Liberalia. In Roman culture, Liber, Bacchus and Dionysus became virtually interchangeable equivalents. Thanks to his mythology involving travels and struggles on earth, Bacchus became euhemerised as a historical hero, conqueror, and founder of cities. He was a patron deity and founding hero at Leptis Magna, birthplace of the emperor Septimius Severus, who promoted his cult. In some Roman sources, the ritual procession of Bacchus in a tiger-drawn chariot, surrounded by maenads, satyrs and drunkards, commemorates the god's triumphant return from the conquest of India. Pliny believed this to be the historical prototype for the Roman Triumph.[177]

Post-classical worship

[edit]Late Antiquity

[edit]

In the Neoplatonist philosophy and religion of Late Antiquity, the Olympian gods were sometimes considered to number 12 based on their spheres of influence. For example, according to Sallustius, "Jupiter, Neptune, and Vulcan fabricate the world; Ceres, Juno, and Diana animate it; Mercury, Venus, and Apollo harmonise it; and, lastly, Vesta, Minerva, and Mars preside over it with a guarding power."[178] The multitude of other gods, in this belief system, subsist within the primary gods, and Sallustius taught that Bacchus subsisted in Jupiter.[178]

In the Orphic tradition, a saying was supposedly given by an oracle of Apollo that stated "Zeus, Hades, [and] Helios-Dionysus" were "three gods in one godhead". This statement apparently conflated Dionysus not only with Hades, but also his father Zeus, and implied a particularly close identification with the sun-god Helios. When quoting this in his Hymn to King Helios, Emperor Julian substituted Dionysus's name with that of Serapis, whose Egyptian counterpart Osiris was also identified with Dionysus.

Worship from the Middle Ages to the Modern period

[edit]

Three centuries after the reign of Theodosius I which saw the outlawing of pagan worship across the Roman Empire, the 692 Quinisext Council in Constantinople felt it necessary to warn Christians against participating in persisting rural worship of Dionysus, specifically mentioning and prohibiting the feast day Brumalia, "the public dances of women", ritual cross-dressing, the wearing of Dionysiac masks, and the invoking of Bacchus's name when "squeez[ing] out the wine in the presses" or "when pouring out wine into jars".[179]

According to the Lanercost chronicle, during Easter in 1282 in Scotland, the parish priest of Inverkeithing led young women in a dance in honor of Priapus and Father Liber, commonly identified with Dionysus. The priest danced and sang at the front, carrying a representation of the phallus on a pole. He was killed by a Christian mob later that year.[180] Historian C. S. Watkins believes that Richard of Durham, the author of the chronicle, identified an occurrence of apotropaic magic (by making use of his knowledge of ancient Greek religion), rather than recording an actual case of the survival of a pagan ritual.[181]

In the eighteenth century, Hellfire Clubs appeared in Britain and Ireland. Though activities varied between the clubs, some of them were very pagan, and included shrines and sacrifices. Dionysus was one of the most popular deities, alongside deities like Venus and Flora. Today one can still see the statue of Dionysus left behind in the Hellfire Caves.[182]

In 1820, Ephraim Lyon founded the Church of Bacchus in Eastford, Connecticut. He declared himself High Priest, and added local drunks to the list of membership. He maintained that those who died as members would go to a Bacchanalia for their afterlife.[183]

Modern pagan and polytheist groups often include worship of Dionysus in their traditions and practices, most prominently groups which have sought to revive Hellenic polytheism, such as the Supreme Council of Ethnic Hellenes (YSEE).[184] In addition to libations of wine, modern worshipers of Dionysus offer the god grape vines, ivy, and various forms of incense, particularly styrax.[185] They may also celebrate Roman festivals such as the Liberalia (17 March, close to the Spring Equinox) or Bacchanalia (Various dates), and various Greek festivals such as the Anthesteria, Lenaia, and the Greater and Lesser Dionysias, the dates of which are calculated by the lunar calendar.[186]

Identification with other gods

[edit]Osiris

[edit]

In the Greek interpretation of the Egyptian pantheon, Dionysus was often identified with Osiris.[187] Stories of the dismembering of Osiris and his re-assembly and resurrection by Isis closely parallel those of the Orphic Dionysus and Demeter.[188] According to Diodorus Siculus,[189] as early as the fifth century BC, the two gods had been syncretised as a single deity known as Dionysus-Osiris. The most notable record of this belief is found in Herodotus's 'Histories'.[190] Plutarch was of the same opinion, recording his belief that Osiris and Dionysus were identical and stating that anyone familiar with the secret rituals associated with the two gods would recognise obvious parallels between them, noting that the myths of their dismembering and their associated public symbols constituted sufficient additional evidence to prove that they were, in fact the same god worshiped by the two cultures under different names.[191]

Other syncretic Greco-Egyptian deities arose out of this conflation, including with the gods Serapis and Hermanubis. Serapis was believed to be both Hades and Osiris, and the Roman Emperor Julian considered him the same as Dionysus as well. Dionysus-Osiris was particularly popular in Ptolemaic Egypt, as the Ptolemies claimed descent from Dionysus, and as Pharaohs they had claim to the lineage of Osiris.[192] This association was most notable during a deification ceremony where Mark Antony became Dionysus-Osiris, alongside Cleopatra as Isis-Aphrodite.[193]

Egyptian myths about Priapus said that the Titans conspired against Osiris, killed him, divided his body into equal parts, and "slipped them secretly out of the house". All but Osiris's penis, which since none of them "was willing to take it with him", they threw into the river. Isis, Osiris's wife, hunted down and killed the Titans, reassembled Osiris's body parts "into the shape of a human figure", and gave them "to the priests with orders that they pay Osiris the honours of a god". But since she was unable to recover the penis she ordered the priests "to pay to it the honours of a god and to set it up in their temples in an erect position."[194]

Hades

[edit]

The fifth–fourth century BC philosopher Heraclitus, unifying opposites, declared that Hades and Dionysus, the very essence of indestructible life (zoë), are the same god.[195] Among other evidence, Karl Kerényi notes in his book[196] that the Homeric Hymn "To Demeter",[197] votive marble images[198] and epithets[199] all link Hades to being Dionysus. He also notes that the grieving goddess Demeter refused to drink wine, as she states that it would be against themis (the very nature of order and justice) for her to drink wine, which is the gift of Dionysus, after Persephone's abduction because of this association; indicating that Hades may in fact have been a "cover name" for the underworld Dionysus.[200] He suggests that this dual identity may have been familiar to those who came into contact with the Mysteries.[201] One of the epithets of Dionysus was "Chthonios", meaning "the subterranean".[202]

Evidence for a cult connection is quite extensive, particularly in southern Italy, especially when considering the heavy involvement of death symbolism included in Dionysian worship.[203] Statues of Dionysus[204][205] found in the Ploutonion at Eleusis give further evidence as the statues found bear a striking resemblance to the statue of Eubouleus, also called Aides Kyanochaites (Hades of the flowing dark hair),[206][207][208] known as the youthful depiction of the Lord of the Underworld. The statue of Eubouleus is described as being radiant but disclosing a strange inner darkness.[209][207] Ancient portrayals show Dionysus holding in his hand the kantharos, a wine-jar with large handles, and occupying the place where one would expect to see Hades. Archaic artist Xenocles portrayed on one side of a vase, Zeus, Poseidon and Hades, each with his emblems of power; with Hades's head turned back to front and, on the other side, Dionysus striding forward to meet his bride Persephone, with the kantharos in his hand, against a background of grapes.[210] Dionysus also shared several epithets with Hades such as Chthonios, Eubouleus and Euclius.

Both Hades and Dionysus were associated with a divine tripartite deity with Zeus.[211][212] Zeus, like Dionysus, was occasionally believed to have an underworld form, closely identified with Hades, to the point that they were occasionally thought of as the same god.[212]

According to Marguerite Rigoglioso, Hades is Dionysus, and this dual god was believed by the Eleusinian tradition to have impregnated Persephone. This would bring the Eleusinian in harmony with the myth in which Zeus, not Hades, impregnated Persephone to bear the first Dionysus. Rigoglioso argues that taken together, these myths suggest a belief that is that, with Persephone, Zeus/Hades/Dionysus created (in terms quoted from Kerényi) "a second, a little Dionysus", who is also a "subterranean Zeus".[212] The unification of Hades, Zeus, and Dionysus as a single tripartite god was used to represent the birth, death and resurrection of a deity and to unify the 'shining' realm of Zeus and the dark underworld realm of Hades.[211] According to Rosemarie Taylor-Perry,[211][212]

it is often mentioned that Zeus, Hades and Dionysus were all attributed to being the exact same god ... Being a tripartite deity Hades is also Zeus, doubling as being the Sky God or Zeus, Hades abducts his 'daughter' and paramour Persephone. The taking of Kore by Hades is the act which allows the conception and birth of a second integrating force: Iacchos (Zagreus-Dionysus), also known as Liknites, the helpless infant form of that Deity who is the unifier of the dark underworld (chthonic) realm of Hades and the Olympian ("Shining") one of Zeus.

Sabazios and Yahweh

[edit]

The Phrygian god Sabazios was alternately identified with Zeus or with Dionysus. The Byzantine Greek encyclopedia, Suda (c. tenth century), stated:[215]

Sabazios ... is the same as Dionysos. He acquired this form of address from the rite pertaining to him; for the barbarians call the bacchic cry "sabazein". Hence some of the Greeks too follow suit and call the cry "sabasmos"; thereby Dionysos [becomes] Sabazios. They also used to call "saboi" those places that had been dedicated to him and his Bacchantes ... Demosthenes [in the speech] "On Behalf of Ktesiphon" [mentions them]. Some say that Saboi is the term for those who are dedicated to Sabazios, that is to Dionysos, just as those [dedicated] to Bakkhos [are] Bakkhoi. They say that Sabazios and Dionysos are the same. Thus some also say that the Greeks call the Bakkhoi Saboi.

Strabo, in the first century, linked Sabazios with Zagreus among Phrygian ministers and attendants of the sacred rites of Rhea and Dionysos.[216] Strabo's Sicilian contemporary, Diodorus Siculus, conflated Sabazios with the secret Dionysus, born of Zeus and Persephone,[217] However, this connection is not supported by any surviving inscriptions, which are entirely to Zeus Sabazios.[218]

Several ancient sources record an apparently widespread belief in the classical world that the god worshiped by the Jewish people, Yahweh, was identifiable as Dionysus or Liber via his identification with Sabazios. Tacitus, Lydus, Cornelius Labeo, and Plutarch all either made this association, or discussed it as an extant belief (though some, like Tacitus, specifically brought it up in order to reject it). According to Plutarch, one of the reasons for the identification is that Jews were reported to hail their god with the words "Euoe" and "Sabi", a cry typically associated with the worship of Sabazius. According to scholar Sean M. McDonough, it is possible that Plutarch's sources had confused the cry of "Iao Sabaoth" (typically used by Greek speakers in reference to Yahweh) with the Sabazian cry of "Euoe Saboe", originating the confusion and conflation of the two deities. The cry of "Sabi" could also have been conflated with the Jewish term "sabbath", adding to the evidence the ancients saw that Yahweh and Dionysus/Sabazius were the same deity. Further bolstering this connection would have been coins used by the Maccabees that included imagery linked to the worship of Dionysus such as grapes, vine leaves, and cups. However the belief that the Jewish god was identical with Dionysus/Sabazius was widespread enough that a coin dated to 55 BC depicting a kneeling king was labelled "Bacchus Judaeus" (BACCHIVS IVDAEVS), and in 139 BC praetor Cornelius Scipio Hispalus deported Jewish people for attempting to "infect the Roman customs with the cult of Jupiter Sabazius".[219]

Mythology

[edit]

Various different accounts and traditions existed in the ancient world regarding the parentage, birth, and life of Dionysus on earth, complicated by his several rebirths. By the first century BC, some mythographers had attempted to harmonise the various accounts of Dionysus's birth into a single narrative involving not only multiple births, but two or three distinct manifestations of the god on earth throughout history in different lifetimes. The historian Diodorus Siculus said that according to "some writers of myths" there were two gods named Dionysus, an older one, who was the son of Zeus and Persephone,[221] but that the "younger one also inherited the deeds of the older, and so the men of later times, being unaware of the truth and being deceived because of the identity of their names thought there had been but one Dionysus."[222] He also said that Dionysus "was thought to have two forms ... the ancient one having a long beard, because all men in early times wore long beards, and the younger one being long-haired, youthful and effeminate and young."[223]

Though the varying genealogy of Dionysus was mentioned in many works of classical literature, only a few contain the actual narrative myths surrounding the events of his multiple births. These include the first century BC Bibliotheca historica by Greek historian Diodorus, which describes the birth and deeds of the three incarnations of Dionysus;[224] the brief birth narrative given by the first century AD Roman author Hyginus, which describes a double birth for Dionysus; and a longer account in the form of Greek poet Nonnus's epic Dionysiaca, which discusses three incarnations of Dionysus similar to Diodorus's account, but which focuses on the life of the third Dionysus, born to Zeus and Semele.

First birth

[edit]Though Diodorus mentions some traditions which state an older, Indian or Egyptian Dionysus existed who invented wine, no narratives are given of his birth or life among mortals, and most traditions ascribe the invention of wine and travels through India to the last Dionysus. According to Diodorus, Dionysus was originally the son of Zeus and Persephone (or alternately, Zeus and Demeter). This is the same horned Dionysus described by Hyginus and Nonnus in later accounts, and the Dionysus worshiped by the Orphics, who was dismembered by the Titans and then reborn. Nonnus calls this Dionysus Zagreus, while Diodorus says he is also considered identical with Sabazius.[225] However, unlike Hyginus and Nonnus, Diodorus does not provide a birth narrative for this incarnation of the god. It was this Dionysus who was said to have taught mortals how to use oxen to plow the fields, rather than doing so by hand. His worshipers were said to have honored him for this by depicting him with horns.[225]

The Greek poet Nonnus gives a birth narrative for Dionysus in his late fourth or early fifth century AD epic Dionysiaca. In it, he described how Zeus "intended to make a new Dionysos grow up, a bullshaped copy of the older Dionysos" who was the Egyptian god Osiris. (Dionysiaca 4)[227] Zeus took the shape of a serpent ("drakon"), and "ravished the maidenhood of unwedded Persephoneia." According to Nonnus, though Persephone was "the consort of the blackrobed king of the underworld", she remained a virgin, and had been hidden in a cave by her mother to avoid the many gods who were her suitors, because "all that dwelt in Olympos were bewitched by this one girl, rivals in love for the marriageable maid." (Dionysiaca 5)[228] After her union with Zeus, Persephone's womb "swelled with living fruit", and she gave birth to a horned baby, named Zagreus. Zagreus, despite his infancy, was able to climb onto the throne of Zeus and brandish his lightning bolts, marking him as Zeus's heir. Hera saw this and alerted the Titans, who smeared their faces with chalk and ambushed the infant Zagreus "while he contemplated his changeling countenance reflected in a mirror." They attacked him. However, according to Nonnus, "where his limbs had been cut piecemeal by the Titan steel, the end of his life was the beginning of a new life as Dionysos." He began to change into many different forms in which he returned the attack, including Zeus, Cronus, a baby, and "a mad youth with the flower of the first down marking his rounded chin with black." He then transformed into several animals to attack the assembled Titans, including a lion, a wild horse, a horned serpent, a tiger, and, finally, a bull. Hera intervened, killing the bull with a shout, and the Titans finally slaughtered him and cut him into pieces. Zeus attacked the Titans and had them imprisoned in Tartaros. This caused the mother of the Titans, Gaia, to suffer, and her symptoms were seen across the whole world, resulting in fires and floods, and boiling seas. Zeus took pity on her, and in order to cool down the burning land, he caused great rains to flood the world. (Dionysiaca 6)[229]

Interpretation

[edit]

In the Orphic tradition, Dionysus was, in part, a god associated with the underworld. As a result, the Orphics considered him the son of Persephone, and believed that he had been dismembered by the Titans and then reborn. The earliest attestation of this myth of the dismemberment and rebirth of Dionysus comes from the 1st century BC, in the works of Philodemus and Diodorus Siculus.[230] Later, Neoplatonists such as Damascius and Olympiodorus added a number of further elements to the myth, including the punishment of the Titans by Zeus for their act, their destruction by a thunderbolt from his hand, and the subsequent birth of humankind from their ashes; however, whether any of these elements were part of the original myth is the subject of debate among scholars.[231] The dismemberment of Dionysus (the sparagmos) has often been considered the most important myth of Orphism.[232]

Many modern sources identify this "Orphic Dionysus" with the god Zagreus, though this name does not seem to have been used by any of the ancient Orphics, who simply called him Dionysus.[233] As pieced together from various ancient sources, the reconstructed story, usually given by modern scholars, goes as follows.[234] Zeus had intercourse with Persephone in the form of a serpent, producing Dionysus. The infant was taken to Mount Ida, where, like the infant Zeus, he was guarded by the dancing Curetes. Zeus intended Dionysus to be his successor as ruler of the cosmos, but a jealous Hera incited the Titans to kill the child. Damascius claims that he was mocked by the Titans, who gave him a fennel stalk (thyrsus) in place of his rightful scepter.[235]

Diodorus relates that Dionysus is the son of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, and that his birth narrative is an allegory for the generative power of the gods at work in nature.[236] When the "Sons of Gaia" (i.e. the Titans) boiled Dionysus following his birth, Demeter gathered together his remains, allowing his rebirth. Diodorus noted the symbolism this myth held for its adherents: Dionysus, god of the vine, was born from the gods of the rain and the earth. He was torn apart and boiled by the sons of Gaia, or "earth born", symbolising the harvesting and wine-making process. Just as the remains of the bare vines are returned to the earth to restore its fruitfulness, the remains of the young Dionysus were returned to Demeter allowing him to be born again.[225]

Second birth

[edit]

The birth narrative given by Gaius Julius Hyginus (c. 64 BC – 17 AD) in Fabulae 167, agrees with the Orphic tradition that Liber (Dionysus) was originally the son of Jove (Zeus) and Proserpine (Persephone). Hyginus writes that Liber was torn apart by the Titans, so Jove took the fragments of his heart and put them into a drink which he gave to Semele, the daughter of Harmonia and Cadmus, king and founder of Thebes. This resulted in Semele becoming pregnant. Juno appeared to Semele in the form of her nurse, Beroe, and told her: "Daughter, ask Jove to come to you as he comes to Juno, so you may know what pleasure it is to sleep with a god." When Semele requested that Jove do so, she was killed by a thunderbolt. Jove then took the infant Liber from her womb, and put him in the care of Nysus. Hyginus states that "for this reason he is called Dionysus, and also the one with two mothers" (dimētōr).[237]

Nonnus describes how, when life was rejuvenated after the flood, it was lacking in revelry in the absence of Dionysus. "The Seasons, those daughters of the lichtgang, still joyless, plaited garlands for the gods only of meadow-grass. For Wine was lacking. Without Bacchos to inspire the dance, its grace was only half complete and quite without profit; it charmed only the eyes of the company, when the circling dancer moved in twists and turns with a tumult of footsteps, having only nods for words, hand for mouth, fingers for voice." Zeus declared that he would send his son Dionysus to teach mortals how to grow grapes and make wine, to alleviate their toil, war, and suffering. After he became protector of humanity, Zeus promises, Dionysus would struggle on earth, but be received "by the bright upper air to shine beside Zeus and to share the courses of the stars." (Dionysiaca 7).[238]

The mortal princess Semele then had a dream, in which Zeus destroyed a fruit tree with a bolt of lightning, but did not harm the fruit. He sent a bird to bring him one of the fruits, and sewed it into his thigh, so that he would be both mother and father to the new Dionysus. She saw the bull-shaped figure of a man emerge from his thigh, and then came to the realisation that she herself had been the tree. Her father Cadmus, fearful of the prophetic dream, instructed Semele to make sacrifices to Zeus.[239] Semele became a priestess of the god and, on one occasion, she was observed by Zeus as she slaughtered a bull at his altar and afterwards swam in the river Asopus to cleanse herself of the blood. Flying over the scene in the guise of an eagle, Zeus fell in love with Semele and repeatedly visited her secretly.[240] The first time he came to Semele in her bed, he was adorned with various symbols of Dionysus. He transformed into a snake, and "Zeus made long wooing, and shouted "Euoi!" as if the winepress were near, as he begat his son who would love the cry." Immediately, Semele's bed and chambers were overgrown with vines and flowers, and the earth laughed. Zeus then spoke to Semele, revealing his true identity, and telling her to be happy: "you bring forth a son who shall not die, and you I will call immortal. Happy woman! you have conceived a son who will make mortals forget their troubles, you shall bring forth joy for gods and men." (Dionysiaca 7).[239]

During her pregnancy, Semele rejoiced in the knowledge that her son would be divine. She dressed herself in garlands of flowers and wreathes of ivy, and would run barefoot to the meadows and forests to frolic whenever she heard music. Hera became envious and feared that Zeus would replace her with Semele as queen of Olympus. She went to Semele in the guise of an old woman who had been Cadmus's wet nurse. She made Semele jealous of the attention Zeus gave to Hera, compared with their own brief liaison and provoked her to request Zeus to appear before her in his full godhood. Semele prayed to Zeus that he show himself. Zeus answered her prayers but warned her that no other mortals had ever seen him as he held his lightning bolts. Semele reached out to touch them and was burnt to ash. (Dionysiaca 8).[241] But the infant Dionysus survived, and Zeus rescued him from the flames, sewing him into his thigh. "So the rounded thigh in labour became female, and the boy too soon born was brought forth, but not in a mother's way, having passed from a mother's womb to a father's." (Dionysiaca 9). At his birth, he had a pair of horns shaped like a crescent moon. The Seasons crowned him with ivy and flowers, and wrapped horned snakes around his own horns.[242]

An alternate birth narrative is given by Diodorus from the Egyptian tradition. In it, Dionysus is the son of Ammon, who Diodorus regards both as the creator god and a quasi-historical king of Libya. Ammon had married the goddess Rhea, but he had an affair with Amaltheia, who bore Dionysus. Ammon feared Rhea's wrath if she were to discover the child, so he took the infant Dionysus to Nysa (Dionysus's traditional childhood home). Ammon brought Dionysus into a cave where he was to be cared for by Nysa, a daughter of the hero Aristaeus.[225] Dionysus grew famous due to his skill in the arts, his beauty, and his strength. It was said that he discovered the art of winemaking during his boyhood. His fame brought him to the attention of Rhea, who was furious with Ammon for his deception. She attempted to bring Dionysus under her own power but, unable to do so, she left Ammon and married Cronus.[225]

Interpretation

[edit]

Even in antiquity, the account of Dionysus's birth to a mortal woman led some to argue that he had been a historical figure who became deified over time, a suggestion of Euhemerism (an explanation of mythic events having roots in mortal history) often applied to demi-gods. The 4th-century Roman emperor and philosopher Julian encountered examples of this belief, and wrote arguments against it. In his letter To the Cynic Heracleios, Julian wrote "I have heard many people say that Dionysus was a mortal man because he was born of Semele and that he became a god through his knowledge of theurgy and the Mysteries, and like our lord Heracles for his royal virtue was translated to Olympus by his father Zeus." However, to Julian, the myth of Dionysus's birth (and that of Heracles) stood as an allegory for a deeper spiritual truth. The birth of Dionysus, Julian argues, was "no birth but a divine manifestation" to Semele, who foresaw that a physical manifestation of the god Dionysus would soon appear. However, Semele was impatient for the god to come, and began revealing his mysteries too early; for her transgression, she was struck down by Zeus. When Zeus decided it was time to impose a new order on humanity, for it to "pass from the nomadic to a more civilized mode of life", he sent his son Dionysus from India as a god made visible, spreading his worship and giving the vine as a symbol of his manifestation among mortals. In Julian's interpretation, the Greeks "called Semele the mother of Dionysus because of the prediction that she had made, but also because the god honored her as having been the first prophetess of his advent while it was yet to be." The allegorical myth of the birth of Dionysus, per Julian, was developed to express both the history of these events and encapsulate the truth of his birth outside the generative processes of the mortal world, but entering into it, though his true birth was directly from Zeus along into the intelligible realm.[12]

Infancy

[edit]

According to Nonnus, Zeus gave the infant Dionysus to the care of Hermes. Hermes gave Dionysus to the Lamides, or daughters of Lamos, who were river nymphs. But Hera drove the Lamides mad and caused them to attack Dionysus, who was rescued by Hermes. Hermes next brought the infant to Ino for fostering by her attendant Mystis, who taught him the rites of the mysteries (Dionysiaca 9). In Apollodorus's account, Hermes instructed Ino to raise Dionysus as a girl, to hide him from Hera's wrath.[243] However, Hera found him, and vowed to destroy the house with a flood; however, Hermes again rescued Dionysus, this time bringing him to the mountains of Lydia. Hermes adopted the form of Phanes, most ancient of the gods, and so Hera bowed before him and let him pass. Hermes gave the infant to the goddess Rhea, who cared for him through his adolescence.[242]

Another version is that Dionysus was taken to the rain-nymphs of Nysa, who nourished his infancy and childhood, and for their care Zeus rewarded them by placing them as the Hyades among the stars (see Hyades star cluster). In yet another version of the myth, he is raised by his cousin Macris on the island of Euboea.[244]

Dionysus in Greek mythology is a god of foreign origin, and while Mount Nysa is a mythological location, it is invariably set far away to the east or to the south. The Homeric Hymn 1 to Dionysus places it "far from Phoenicia, near to the Egyptian stream".[245] Others placed it in Anatolia, or in Libya ("away in the west beside a great ocean"), in Ethiopia (Herodotus), or Arabia (Diodorus Siculus).[246] According to Herodotus:

As it is, the Greek story has it that no sooner was Dionysus born than Zeus sewed him up in his thigh and carried him away to Nysa in Ethiopia beyond Egypt; and as for Pan, the Greeks do not know what became of him after his birth. It is therefore plain to me that the Greeks learned the names of these two gods later than the names of all the others, and trace the birth of both to the time when they gained the knowledge.

— Herodotus, Histories 2.146.2

The Bibliotheca seems to be following Pherecydes, who relates how the infant Dionysus, god of the grapevine, was nursed by the rain-nymphs, the Hyades at Nysa. Young Dionysus was also said to have been one of the many famous pupils of the centaur Chiron. According to Ptolemy Chennus in the Library of Photius, "Dionysus was loved by Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances, the bacchic rites and initiations."[247]

Travels and invention of wine

[edit]

When Dionysus grew up, he discovered the culture of the vine and the mode of extracting its precious juice, being the first to do so;[248] but Hera struck him with madness, and drove him forth a wanderer through various parts of the earth. In Phrygia the goddess Cybele, better known to the Greeks as Rhea, cured him and taught him her religious rites, and he set out on a progress through Asia teaching the people the cultivation of the vine. The most famous part of his wanderings is his expedition to India, which is said to have lasted several years. According to a legend, when Alexander the Great reached a city called Nysa near the Indus river, the locals said that their city was founded by Dionysus in the distant past and their city was dedicated to the god Dionysus.[249] These travels took something of the form of military conquests; according to Diodorus Siculus he conquered the whole world except for Britain and Ethiopia.[250]

Another myth according to Nonnus involves Ampelus, a satyr, who was loved by Dionysus. As related by Ovid, Ampelus became the constellation Vindemitor, or the "grape-gatherer":[251]

... not so will the Grape-gatherer escape thee. The origin of that constellation also can be briefly told. 'Tis said that the unshorn Ampelus, son of a nymph and a satyr, was loved by Bacchus on the Ismarian hills. Upon him the god bestowed a vine that trailed from an elm's leafy boughs, and still the vine takes from the boy its name. While he rashly culled the gaudy grapes upon a branch, he tumbled down; Liber bore the lost youth to the stars."

Another story of Ampelus was related by Nonnus: in an accident foreseen by Dionysus, the youth was killed while riding a bull maddened by the sting of a gadfly sent by Selene, the goddess of the Moon. The Fates granted Ampelus a second life as a vine, from which Dionysus squeezed the first wine.[252]

Return to Greece

[edit]

Returning in triumph to Greece after his travels in Asia, Dionysus came to be considered the founder of the triumphal procession. He undertook efforts to introduce his religion into Greece, but was opposed by rulers who feared it, on account of the disorders and madness it brought with it.

In one myth, adapted in Euripides's play The Bacchae, Dionysus returns to his birthplace, Thebes, which is ruled by his cousin Pentheus. Pentheus, as well as his mother Agave and his aunts Ino and Autonoe, disbelieve Dionysus's divine birth. Despite the warnings of the blind prophet Tiresias, they deny his worship and denounce him for inspiring the women of Thebes to madness.

Dionysus uses his divine powers to drive Pentheus insane, then invites him to spy on the ecstatic rituals of the Maenads, in the woods of Mount Cithaeron. Pentheus, hoping to witness a sexual orgy, hides himself in a tree. The Maenads spot him; maddened by Dionysus, they take him to be a mountain-dwelling lion and attack him with their bare hands. Pentheus's aunts and his mother Agave are among them, and they rip him limb from limb. Agave mounts his head on a pike and takes the trophy to her father Cadmus.

Euripides's description of this sparagmos was as follows:

"But she was foaming at the mouth, her eyes rolled all around; her mind was mindless now. Held by the god, she paid the man no heed. She grabbed his left arm just below the elbow: wedging her foot against the victim's ribs she ripped his shoulder off – not by mere force; the god made easy everything they touch. On his right arm worked Ino, ripping flesh; Autonoë and the mob of maenads griped him, screaming as one. While he had breath, he cried, but they were whooping victory calls. One took an arm, a foot another, boot and all. They stripped his torso bare, staining their nails with blood, then tossed balls of flesh around. Pentheus' body lies in fragments now: on the hard rocks, and mingled with the leaves buried in the woodland, hard to find. His mother stumbled across his head: poor head! She grabbed it, and fixed it on her thyrsus, like a lions's, to wave in joyful triumph at her hunt."[254]

The madness passes. Dionysus arrives in his true, divine form, banishes Agave and her sisters, and transforms Cadmus and his wife Harmonia into serpents. Only Tiresias is spared.[255]

In the Iliad, when King Lycurgus of Thrace heard that Dionysus was in his kingdom, he imprisoned Dionysus's followers, the Maenads. Dionysus fled and took refuge with Thetis, and sent a drought which stirred the people to revolt. The god then drove King Lycurgus insane and had him slice his own son into pieces with an axe in the belief that he was a patch of ivy, a plant holy to Dionysus. An oracle then claimed that the land would stay dry and barren as long as Lycurgus lived, and his people had him drawn and quartered. Appeased by the king's death, Dionysus lifted the curse.[256][257] In an alternative version, sometimes depicted in art, Lycurgus tries to kill Ambrosia, a follower of Dionysus, who was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king and slowly strangled him.[258]

Captivity and escape

[edit]

The Homeric Hymn 7 to Dionysus recounts how, while he sat on the seashore, some sailors spotted him, believing him a prince. They attempted to kidnap him and sail away to sell him for ransom or into slavery. No rope would bind him. The god turned into a fierce lion and unleashed a bear on board, killing all in his path. Those who jumped ship were mercifully turned into dolphins. The only survivor was the helmsman, Acoetes, who recognised the god and tried to stop his sailors from the start.[259]

In a similar story, Dionysus hired a Tyrrhenian pirate ship to sail from Icaria to Naxos. When he was aboard, they sailed not to Naxos but to Asia, intending to sell him as a slave. This time the god turned the mast and oars into snakes, and filled the vessel with ivy and the sound of flutes so that the sailors went mad and, leaping into the sea, were turned into dolphins. In Ovid's Metamorphoses, Bacchus begins this story as a young child found by the pirates but transforms to a divine adult when on board.

Many of the myths involve Dionysus defending his godhead against skeptics. Malcolm Bull notes that "It is a measure of Bacchus's ambiguous position in classical mythology that he, unlike the other Olympians, had to use a boat to travel to and from the islands with which he is associated".[260] Paola Corrente notes that in many sources, the incident with the pirates happens towards the end of Dionysus's time among mortals. In that sense, it serves as final proof of his divinity and is often followed by his descent into Hades to retrieve his mother, both of whom can then ascend into heaven to live alongside the other Olympian gods.[16]

Descent to the underworld

[edit]

Pausanias, in book II of his Description of Greece, describes two variant traditions regarding Dionysus's katabasis, or descent into the underworld. Both describe how Dionysus entered into the afterlife to rescue his mother Semele, and bring her to her rightful place on Olympus. To do so, he had to contend with the hell dog Cerberus, which was restrained for him by Heracles. After retrieving Semele, Dionysus emerged with her from the unfathomable waters of a lagoon on the coast of the Argolid near the prehistoric site of Lerna, according to the local tradition.[263] This mythic event was commemorated with a yearly nighttime festival, the details of which were held secret by the local religion. According to Paola Corrente, the emergence of Dionysus from the waters of the lagoon may signify a form of rebirth for both him and Semele as they reemerged from the underworld.[16][264] A variant of this myth forms the basis of Aristophanes's comedy The Frogs.[16]

According to the Christian writer Clement of Alexandria, Dionysus was guided in his journey by Prosymnus or Polymnus, who requested, as his reward, to be Dionysus's lover. Prosymnus died before Dionysus could honor his pledge, so to satisfy Prosymnus's shade, Dionysus fashioned a phallus from a fig branch and penetrated himself with it at Prosymnus's tomb.[265][266] This story survives in full only in Christian sources, whose aim was to discredit pagan mythology, but it appears to have also served to explain the origin of secret objects used by the Dionysian Mysteries.[267]

This same myth of Dionysus's descent to the underworld is related by both Diodorus Siculus in his first century BC work Bibliotheca historica, and Pseudo-Apollodorus in the third book of his first century AD work Bibliotheca. In the latter, Apollodorus tells how after having been hidden away from Hera's wrath, Dionysus traveled the world opposing those who denied his godhood, finally proving it when he transformed his pirate captors into dolphins. After this, the culmination of his life on earth was his descent to retrieve his mother from the underworld. He renamed his mother Thyone, and ascended with her to heaven, where she became a goddess.[268] In this variant of the myth, it is implied that Dionysus must prove his godhood to mortals and then also legitimised his place on Olympus by proving his lineage and elevating his mother to divine status, before taking his place among the Olympic gods.[16]

Secondary myths

[edit]Midas's golden touch

[edit]

Dionysus discovered that his old school master and foster father, Silenus, had gone missing. The old man had wandered away drunk, and was found by some peasants who carried him to their king Midas (alternatively, he passed out in Midas's rose garden). The king recognised him hospitably, feasting him for ten days and nights while Silenus entertained with stories and songs. On the eleventh day, Midas brought Silenus back to Dionysus. Dionysus offered the king his choice of reward.

Midas asked that whatever he might touch would turn to gold. Dionysus consented, though was sorry that he had not made a better choice. Midas rejoiced in his new power, which he hastened to put to the test. He touched and turned to gold an oak twig and a stone, but his joy vanished when he found that his bread, meat, and wine also turned to gold. Later, when his daughter embraced him, she too turned to gold.

The horrified king strove to divest the Midas Touch, and he prayed to Dionysus to save him from starvation. The god consented, telling Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. As he did so, the power passed into them, and the river sands turned gold: this etiological myth explained the gold sands of the Pactolus.

Love affairs

[edit]

When Theseus abandoned Ariadne sleeping on Naxos, Dionysus found and married her. They had a son named Oenopion, but she committed suicide or was killed by Perseus. In some variants, Dionysus had her crown put into the heavens as the constellation Corona; in others, he descended into Hades to restore her to the gods on Olympus. Another account claims Dionysus ordered Theseus to abandon Ariadne on the island of Naxos, for Dionysus had seen her as Theseus carried her onto the ship and had decided to marry her.[citation needed] Psalacantha, a nymph, promised to help Dionysus court Ariadne in exchange for his sexual favours; but Dionysus refused, so Psalacantha advised Ariadne against going with him. For this Dionysus turned her into the plant with the same name.[269]

Dionysus fell in love with a nymph named Nicaea, in some versions by Eros's binding. Nicaea however was a sworn virgin and scorned his attempts to court her. So one day, while she was away, he replaced the water in the spring from which she used to drink with wine. Intoxicated, Nicaea passed out, and Dionysus raped her in her sleep. When she woke up and realised what had happened, she sought him out to harm him, but she never found him. She gave birth to his sons Telete, Satyrus, and others. Dionysus named the ancient city of Nicaea after her.[270]

In Nonnus's Dionysiaca, Eros made Dionysus fall in love with Aura, a virgin companion of Artemis, as part of a ploy to punish Aura for having insulted Artemis. Dionysus used the same trick as with Nicaea to get her fall asleep, tied her up, and then raped her. Aura tried to kill herself, with little success. When she gave birth to twin sons by Dionysus, Iacchus and another boy, she ate one twin before drowning herself in the Sangarius river.[271]

Also in the Dionysiaca, Nonnus relates how Dionysus fell in love with a handsome satyr named Ampelos, who was killed by Selene due to him challenging her. On his death, Dionysus changed him into the first grapevine.[272] Elsewhere in the same epic, Dionysus arrives in Thrace to punish the impious king Sithon who slays all of his daughter Pallene's suitors; after a brief wrestling match with the princess herself, he defeats her, kills Sithon and beds the maiden.[273]

Other myths

[edit]

Another account about Dionysus's parentage indicates that he is the son of Zeus and Gê (Gaia), also named Themelê (foundation), corrupted into Semele.[274][275]

When Hephaestus bound Hera to a magical chair, Dionysus got him drunk and brought him back to Olympus after he passed out.[citation needed]

During the Gigantomachy, Dionysus killed the giant Eurytus with his thyrsus.

A third descent by Dionysus to Hades is invented by Aristophanes in his comedy The Frogs. Dionysus, as patron of the Athenian dramatic festival, the Dionysia, wants to bring back to life one of the great tragedians. After a poetry slam, Aeschylus is chosen in preference to Euripides.

Callirrhoe was a Calydonian woman who scorned Coresus, a priest of Dionysus, who threatened to afflict all the women of Calydon with insanity (see Maenad). The priest was ordered to sacrifice Callirhoe but he killed himself instead. Callirhoe threw herself into a well which was later named after her.[citation needed]

Dionysus also sent a fox that was fated never to be caught in Thebes. Creon, king of Thebes, sent Amphitryon to catch and kill the fox. Amphitryon obtained from Cephalus the dog that his wife Procris had received from Minos, which was fated to catch whatever it pursued.[citation needed]

Hyginus relates that Dionysus once gave human speech to a donkey. The donkey then proceeded to challenge Priapus in a contest about which between them had the better penis; the donkey lost. Priapus killed the donkey, but Dionysus placed him among the stars, above the Crab.[276][277]

Children

[edit]The following is a list of Dionysus's offspring, by various mothers. Beside each offspring, the earliest source to record the parentage is given, along with the century to which the source (in some cases approximately) dates.

| Offspring | Mother | Source | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Charites | Aphrodite | Servius | 4th/5th cent. AD | [278] |

| Coronis | Nonnus | 5th cent. AD | [279] | |

| Ceramus | Ariadne | Paus. | 2nd cent. AD | [280] |

| Enyeus | [281] | |||

| Oenopion, Staphylus, Thoas | Apollod. | 1st/2nd cent. AD | [282] | |

| Euanthes, Tauropolis, Latramys | Schol. Ap. Rh. | [283] | ||

| Peparethus | Apollod. | 1st/2nd cent. AD | [284] | |

| Maron | Euripides | 5th cent. BC | [285] | |

| Phlias | Hyg. Fab. | 1st cent. AD | [286] | |

| Carmanor | Alexirrhoe | Ps.-Plut. Fluv. | 2nd cent. AD | [287] |

| Iacchus | Aura | Nonnus | 5th cent. AD | [288] |

| Unnamed twin brother | Nonnus | 5th cent. AD | [289] | |

| Medus | Alphesiboea | Ps.-Plut. Fluv. | 2nd cent. AD | [290] |

| Phlias | Araethyrea | Paus. | 2nd cent. AD | [291] |

| Chthonophyle | [292] | |||

| Priapus | Aphrodite | Paus. | 2nd cent. AD | [293] |

| Chione | Schol. Theoc. | [294] | ||

| Percote | [295] | |||

| Telete | Nicaea | Nonnus | 5th cent. AD | [296] |

| Satyrus, Other unnamed sons | Memnon of Heraclea | 1st cent. AD | [297] | |

| Narcaeus | Physcoa | Paus. | 2nd cent. AD | [298] |

| Methe | No mother mentioned | Anacreon | 6th cent. AD | [299] |

| Sabazius | [300] | |||

| Thysa | Strabo | 1st cent. AD | [301] | |

| Pasithea | Nonnus | 5th cent. AD | [302] | |

| Phanus | Apollod. | 1st/2nd cent. AD | [303] |

Iconography and depictions

[edit]Symbols

[edit]