Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Absorption refrigerator

View on Wikipedia| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

An absorption refrigerator is a refrigerator that uses a heat source to provide the energy needed to drive the cooling process. Solar energy, burning a fossil fuel, waste heat from factories, and district heating systems are examples of heat sources that can be used.

An absorption refrigerator uses two coolants: the first coolant performs evaporative cooling and then is absorbed into the second coolant; heat is needed to reset the two coolants to their initial states.

Absorption refrigerators are commonly used in recreational vehicles (RVs), campers, and caravans because the heat required to power them can be provided by a propane fuel burner, by a low-voltage DC electric heater (from a battery or vehicle electrical system) or by a mains-powered electric heater. Absorption refrigerators can also be used to air-condition buildings using the waste heat from a gas turbine or water heater in the building. Using waste heat from a gas turbine makes the turbine very efficient because it first produces electricity, then hot water, and finally, air-conditioning—trigeneration.

Unlike more common vapor-compression refrigeration systems, an absorption refrigerator has no moving parts.

History

[edit]In the early years of the 20th century, the vapor absorption cycle using water-ammonia systems was popular and widely used, but after the development of the vapor compression cycle it lost much of its importance because of its low coefficient of performance (about one fifth of that of the vapor compression cycle).[citation needed] Absorption refrigerators are a popular alternative to regular compressor refrigerators where electricity is unreliable, costly, or unavailable, or where noise from the compressor is problematic; or where surplus heat is available.

In 1748 in Glasgow, William Cullen invented the basis for modern refrigeration, although he is not credited with a usable application. More on history of refrigeration can be found in the paragraph Refrigeration Research on page Refrigeration.

Absorption refrigeration uses the same principle as adsorption refrigeration, which was invented by Michael Faraday in 1821, but instead of using a solid adsorber, in an absorption system an absorber absorbs the refrigerant vapour into a liquid.

Absorption cooling was invented by the French scientist Ferdinand Carré in 1858.[1] The original design used water and sulphuric acid. In 1922, two students at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden, Baltzar von Platen and Carl Munters, enhanced the principle with a three-fluid configuration. This "Platen-Munters" design can operate without a pump.

Commercial production began in 1923 by the newly-formed company AB Arctic, which was bought by Electrolux in 1925. In the 1960s, absorption refrigeration saw a renaissance due to the substantial demand for refrigerators for caravans (travel trailers). AB Electrolux established a subsidiary in the United States, named Dometic Sales Corporation. The company marketed refrigerators for recreational vehicles (RVs) under the Dometic brand. In 2001, Electrolux sold most of its leisure products line to the venture-capital company EQT which created Dometic as a stand-alone company. Dometic still sold absorption fridges as of July 2025.[2]

In 1926, Albert Einstein and his former student Leó Szilárd proposed an alternative design known as the Einstein refrigerator.[3]

At the 2007 TED Conference, Adam Grosser presented his research of a new, very small, "intermittent absorption" vaccine refrigeration unit for use in third world countries. The refrigerator is a small unit placed over a campfire, that can later be used to cool 15 litres (3.3 imp gal; 4.0 US gal) of water to just above freezing for 24 hours in a 30 °C (86 °F) environment.[4] The concept was similar to an early refrigeration device known as an Icyball.

Principles

[edit]Common absorption refrigerators use a refrigerant with a very low boiling point (less than −18 °C (0 °F)) just like compressor refrigerators. Compression refrigerators typically use an HCFC or HFC, while absorption refrigerators typically use ammonia or water and need at least a second fluid able to absorb the coolant, the absorbent, respectively water (for ammonia) or brine (for water). Both types use evaporative cooling: when the refrigerant evaporates (boils), it takes some heat away with it, providing the cooling effect. The main difference between the two systems is the way the refrigerant is changed from a gas back into a liquid so that the cycle can repeat. An absorption refrigerator changes the gas back into a liquid using a method that needs only heat, and has no moving parts other than the fluids.

The absorption cooling cycle can be described in three phases:

- Evaporation: A liquid refrigerant evaporates in a low partial pressure environment, thus extracting heat from its surroundings (e.g. the refrigerator's compartment). Because of the low partial pressure, the temperature needed for evaporation is also low.

- Absorption: The second fluid, in a depleted state, sucks out the now gaseous refrigerant, thus providing the low partial pressure. This produces a refrigerant-saturated liquid which then flows to the next step:

- Regeneration: The refrigerant-saturated liquid is heated, causing the refrigerant to evaporate out.

- The evaporation occurs at the lower end of a narrow tube; the bubbles of refrigerant gas push the refrigerant-depleted liquid into a higher chamber, from which it will flow by gravity to the absorption chamber.

- The hot gaseous refrigerant passes through a heat exchanger, transferring its heat outside the system (such as to surrounding ambient-temperature air), and condenses at a higher place. The condensed (liquid) refrigerant will then flow by gravity to supply the evaporation phase.

The system thus silently provides for the mechanical circulation of the liquid without a usual pump. A third fluid, gaseous, is usually added to avoid pressure concerns when condensation occurs (see below).

In comparison, a compressor based heat pump works by pumping refrigerant gas from an evaporator to a condenser. This reduces the pressure and boiling temperature in the evaporator and increases the pressure and condensing temperature in the condenser. Energy from an electric motor or internal combustion engine is required to operate the compressor pump. Compressing the refrigerant uses this energy to do work on the gas, increasing its temperature. The warm, high pressure gas then enters the condenser where it undergoes a phase change to a liquid, releasing heat to the condenser's surroundings. Warm liquid refrigerant moves from the high pressure condenser to the low pressure evaporator via an expansion valve, also known as a throttling valve or a Joule-Thomson valve. The expansion valve partially vaporizes the refrigerant cooling it via evaporative cooling and the resulting vapor is cooled via expansive cooling. (This is a combination of Joule-Thomson cooling and work done by the expanding gas, both at the expense of the internal energy of the gas) The cold, low pressure liquid refrigerant will now absorb heat from the evaporator's surroundings and vaporize. The resulting gas enters the compressor and the cycle begins again.

Simple salt and water system

[edit]A simple absorption refrigeration system common in large commercial plants uses a solution of lithium bromide or lithium chloride salt and water. Water under low pressure is evaporated from the coils that are to be chilled. The water is absorbed by a lithium bromide/water solution. The system drives the water out of the lithium bromide solution with heat.[5]

Water spray absorption refrigeration

[edit]

Another variant uses air, water, and a salt water solution. The intake of warm, moist air is passed through a sprayed solution of salt water. The spray lowers the humidity but does not significantly change the temperature. The less humid, warm air is then passed through an evaporative cooler, consisting of a spray of fresh water, which cools and re-humidifies the air. Humidity is removed from the cooled air with another spray of salt solution, providing the outlet of cool, dry air.

The salt solution is regenerated by heating it under low pressure, causing water to evaporate. The water evaporated from the salt solution is re-condensed, and rerouted back to the evaporative cooler.

Single pressure absorption refrigeration

[edit]

1. Hydrogen enters the pipe with liquid ammonia

2. Ammonia and hydrogen enter the inner compartment. Volume increase causes a decrease in the partial pressure of the liquid ammonia. The ammonia evaporates, taking heat from the liquid ammonia (ΔHVap) lowering its temperature. Heat flows from the hotter interior of the refrigerator to the colder liquid, promoting further evaporation.

3. Ammonia and hydrogen return from the inner compartment, ammonia returns to absorber and dissolves in water. Hydrogen is free to rise.

4. Ammonia gas condensation (passive cooling).

5. Hot ammonia gas.

6. Heat insulation and distillation of ammonia gas from water.

7. Electric heat source.

8. Absorber vessel (water and ammonia solution).

A single-pressure absorption refrigerator takes advantage of the fact that a liquid's evaporation rate depends upon the partial pressure of the vapor above the liquid and goes up with lower partial pressure. While having the same total pressure throughout the system, the refrigerator maintains a low partial pressure of the refrigerant (therefore high evaporation rate) in the part of the system that draws heat out of the low-temperature interior of the refrigerator, but maintains the refrigerant at high partial pressure (therefore low evaporation rate) in the part of the system that expels heat to the ambient-temperature air outside the refrigerator.

The refrigerator uses three substances: ammonia, hydrogen gas, and water. The cycle is closed, with all hydrogen, water and ammonia collected and endlessly reused. The system is pressurized to raise the boiling point of ammonia higher than the temperature of the condenser coil (the coil which transfers heat to the air outside the refrigerator, by being hotter than the outside air.) This pressure is typically 14–16 standard atmospheres (1,400–1,600 kPa) putting the dew point of ammonia at about 35 °C (95 °F).

The cooling cycle starts with liquid ammonia at room temperature entering the evaporator. The volume of the evaporator is greater than the volume of the liquid, with the excess space occupied by a mixture of gaseous ammonia and hydrogen. The presence of hydrogen lowers the partial pressure of the ammonia gas, thus lowering the evaporation point of the liquid below the temperature of the refrigerator's interior. Ammonia evaporates, taking a small amount of heat from the liquid and lowering the liquid's temperature. It continues to evaporate, while the large enthalpy of vaporization (heat) flows from the warmer refrigerator interior to the cooler liquid ammonia and then to more ammonia gas.

In the next two steps, the ammonia gas is separated from the hydrogen so it can be reused.

- The ammonia (gas) and hydrogen (gas) mixture flows through a pipe from the evaporator into the absorber. In the absorber, this mixture of gases contacts water (technically, a weak solution of ammonia in water). The gaseous ammonia dissolves in the water, while the hydrogen, which doesn't, collects at the top of the absorber, leaving the now-strong ammonia-and-water solution at the bottom. The hydrogen is now separate while the ammonia is now dissolved in the water.

- The next step separates the ammonia and water. The ammonia/water solution flows to the generator (boiler), where heat is applied to boil off the ammonia, leaving most of the water (which has a higher boiling point) behind. Some water vapor and bubbles remain mixed with the ammonia; this water is removed in the final separation step, by passing it through the separator, an uphill series of twisted pipes with minor obstacles to pop the bubbles, allowing the water vapor to condense and drain back to the generator.

The pure ammonia gas then enters the condenser. In this heat exchanger, the hot ammonia gas transfers its heat to the outside air, which is below the boiling point of the full-pressure ammonia, and therefore condenses. The condensed (liquid) ammonia flows down to be mixed with the hydrogen gas released from the absorption step, repeating the cycle.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Granryd, Eric; Palm, Björn (2005), "4-3", Refrigerating engineering, Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology

- ^ "RV Refrigerators". Archived from the original on 2025-07-11. Retrieved 2025-09-03.

- ^ US 1781541, Einstein & Szilárd, "Refrigeration", issued 1930-11-11

- ^ Grosser, Adam (Feb 2007). "Adam Grosser and his sustainable fridge". TED. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ^ Sapali, S. N (11 February 2009). "Lithium Bromide Absorption Refrigeration System". Textbook Of Refrigeration And Air-Conditioning. New Delhi: PHI learning. p. 258. ISBN 978-81-203-3360-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Levy, A.; Kosloff, R. (2012). "Quantum Absorption Refrigerator". Phys. Rev. Lett. 108 (7) 070604. arXiv:1109.0728. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108g0604L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.070604. PMID 22401189. S2CID 6981288.

External links

[edit]- Absorption Heat Pumps (Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy).

- Arizona Energy Explanation with diagrams

- Lithium-Bromide / Water Cycle – Absorption Refrigeration for Campus Cooling at BYU.

- American National Standards Institute. "AHRI standard 560–2000 for absorption refrigerators" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2012-03-31.

Absorption refrigerator

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Basic Principle

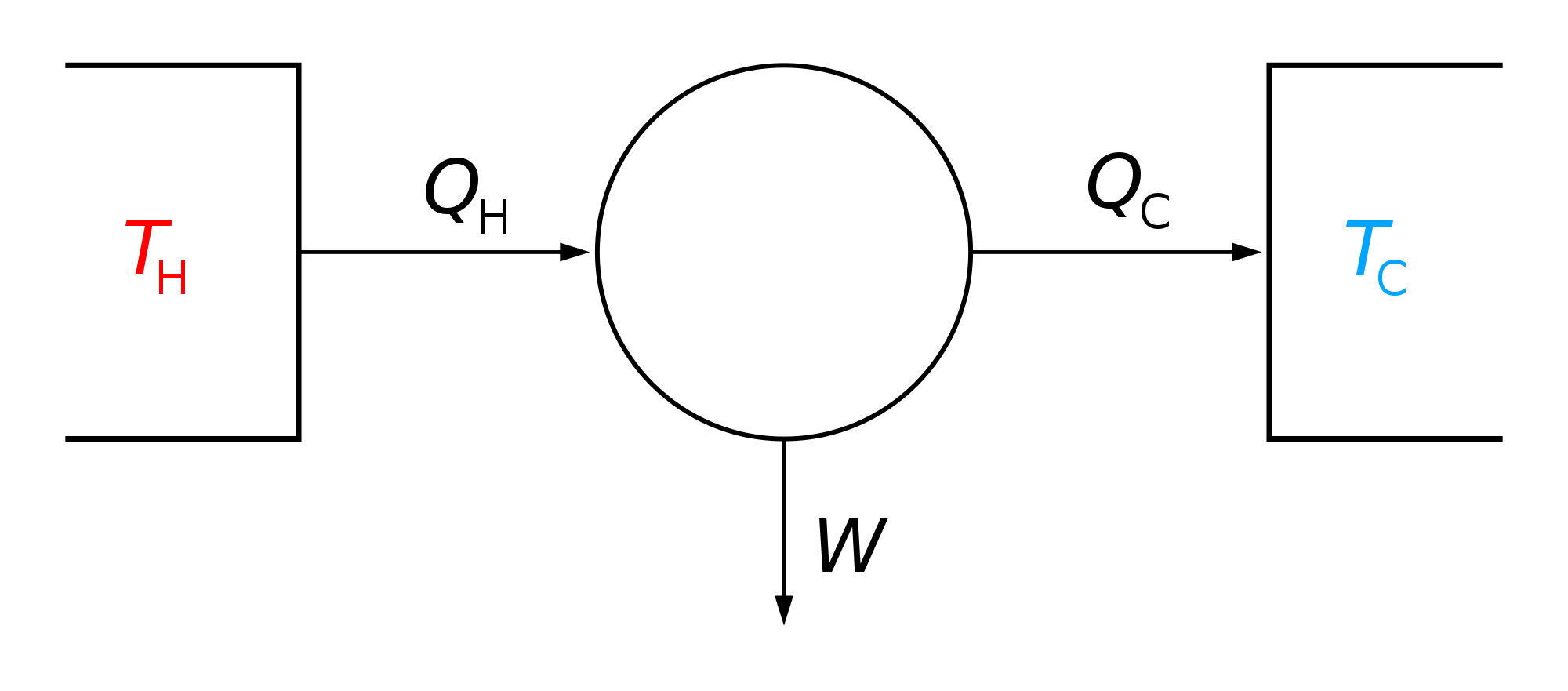

An absorption refrigerator operates on a heat-driven thermodynamic cycle that achieves cooling through the absorption and desorption of a refrigerant in a liquid absorbent, without relying on mechanical compression. In this system, a refrigerant vapor, such as ammonia, is absorbed into a liquid absorbent, typically water, forming a solution; heat is then applied to separate the refrigerant, allowing it to circulate and produce cooling effects.[1] This process contrasts with conventional vapor-compression refrigerators, which use electrical energy to power a compressor, by instead utilizing thermal energy as the primary driver.[5] The cycle consists of four main processes. In the generation stage, heat supplied to the generator causes desorption, releasing refrigerant vapor from the absorbent solution. The vapor then travels to the condenser, where it cools and condenses into a liquid, rejecting heat to the surroundings. Next, in the evaporator, the liquid refrigerant expands and evaporates at low pressure, absorbing heat from the cooled space to provide refrigeration. Finally, the refrigerant vapor is reabsorbed into the weakened absorbent in the absorber, completing the cycle and preparing the solution for recirculation via a small pump.[6] This mechanism enables the use of low-grade heat sources, such as natural gas, solar thermal energy, or industrial waste heat, to drive the refrigeration process, making it suitable for applications where electricity is limited or costly.[1] The basic schematic includes a generator for desorption, an absorber for reabsorption, a condenser for liquefaction, an evaporator for cooling, and a solution pump to maintain circulation, all interconnected in a closed loop.[7]Key Components

The absorption refrigerator operates through a network of interconnected components that facilitate the separation, circulation, and recombination of refrigerant and absorbent in a closed-loop configuration. The primary elements include the generator, absorber, condenser, evaporator, solution pump, and heat exchangers, each performing a specific function to enable heat-driven cooling without mechanical compression.[8] The generator, often heated by an external source such as steam or waste heat, desorbs refrigerant vapor from the absorbent-refrigerant solution by elevating its temperature, typically to 55–225°C depending on the system design; the resulting weak solution (depleted of refrigerant) is then directed back to the absorber.[8] The absorber mixes the incoming refrigerant vapor with the weak solution under cooling conditions, forming a strong solution that releases heat to an external sink; this process relies on the affinity between the refrigerant and absorbent to achieve efficient absorption.[8] In the condenser, the pure refrigerant vapor from the generator is cooled—often to 25–50°C—and liquefied, rejecting latent heat to the surroundings before flowing to the evaporator.[8] The evaporator allows the liquid refrigerant to expand and vaporize at low pressure (around 0–15°C), absorbing heat from the cooled space to produce the refrigeration effect, after which the vapor proceeds to the absorber.[8] The solution pump circulates the strong solution from the absorber to the generator, requiring minimal energy input compared to vapor compression systems.[8] Heat exchangers, such as solution heat exchangers, enhance overall efficiency by transferring heat between the strong and weak solutions, potentially increasing the coefficient of performance (COP) by 44–66% through thermal recovery.[8] Construction materials for these components are selected for compatibility with the working fluids and operational pressures. In ammonia-based systems, pressure vessels and piping are typically fabricated from steel, as ammonia is incompatible with copper or brass, ensuring durability and preventing corrosion when combined with corrosion inhibitors like sodium chromate.[2] For water-lithium bromide systems, corrosion-resistant alloys are employed to mitigate degradation from the hygroscopic absorbent.[8] These components integrate into a sealed, closed-loop system where the refrigerant and absorbent continuously cycle without external replenishment, maintaining system integrity. A still or rectifier is often incorporated at the generator outlet to purify the refrigerant vapor by separating impurities (e.g., water in ammonia systems), preventing contamination in downstream components and improving efficiency.[8] Safety features are essential, particularly in ammonia-based systems due to the refrigerant's toxicity and pressure risks. Pressure relief valves are standard on pressure vessels to automatically vent excess pressure, preventing ruptures and ensuring compliance with safety standards. Additional measures, such as excess flow valves and leak detection, may be integrated to contain potential releases.[9]History

Invention and Early Development

The absorption refrigerator was first invented by French engineer Edmond Carré in 1850, who developed an intermittent machine using water as the refrigerant and sulfuric acid as the absorbent.[10] This pioneering device marked the beginning of absorption-based cooling through a chemical process, though it required manual reheating for each cycle and was limited in practicality. Building on this, Edmond's brother Ferdinand Carré developed the first practical ammonia-water absorption system in 1858.[11] This system utilized ammonia as the refrigerant and water as the absorbent, enabling more efficient production of artificial cold. Ferdinand Carré refined the design in the late 1850s, achieving continuous operation that reduced manual intervention and improved reliability. He secured a French patent for the ammonia-water machine in 1859 and a U.S. patent in 1860 (No. 30,201), which described an apparatus capable of producing ice at rates up to 200 kg per hour in industrial scales.[12][13] Further enhancements in the 1860s included adaptations for greater efficiency, such as integrating agitators inspired by earlier vacuum systems to optimize fluid circulation, allowing for more automatic operation powered by external heat sources, though early versions still required some manual oversight.[12] The technology gained public attention through demonstrations, notably at the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition, where Ferdinand Carré's apparatus was exhibited for producing artificial cold and ice, highlighting its potential for commercial applications like food preservation during the American Civil War era. Despite these innovations, early absorption refrigerators faced substantial challenges, including low thermal efficiency—often requiring excessive heat input for modest cooling output—and persistent need for manual intervention in charging and regenerating the absorbent, which hindered scalability and led to limited adoption outside specialized industrial settings by the late 19th century.[14][12]Commercialization and Modern Advancements

In the 1910s and 1920s, Albert Einstein and Leó Szilárd collaborated on developing an innovative absorption refrigerator design that eliminated the need for mechanical pumps, addressing the noise issues associated with compressor-based systems of the era.[4] Their partnership began after Einstein, motivated by reports of fatal accidents from leaking mechanical refrigerators, sought a safer alternative; they filed a patent application in Germany on December 16, 1926, followed by filings in the UK and US, culminating in US Patent 1,781,541 granted in 1930.[15] This pump-free system relied on natural circulation driven by heat and gravity, using ammonia as the refrigerant, water as the absorbent, and butane as an auxiliary gas to enhance efficiency without moving parts.[16] Commercialization gained momentum in the late 1920s through Servel Inc., which licensed and produced gas-fired absorption refrigerators for household use, capitalizing on the design's quiet operation and fuel flexibility.[17] By 1927, Servel had partnered with Electrolux to manufacture these models in the US, achieving widespread adoption as they offered a reliable alternative to electric units during a period of limited electrification.[18] Popularity peaked in the 1930s, with Servel selling millions of units before the dominance of cheaper, more efficient electric compression refrigerators in the 1940s led to a decline in market share.[19] Following World War II, absorption refrigerators experienced a revival in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly for off-grid applications such as recreational vehicles (RVs) and boats, where access to electricity was unreliable.[20] Manufacturers like Electrolux and its Dometic brand developed compact, propane-powered models that operated without external power, enabling cooling in remote settings and boosting the RV industry's growth.[21] These units, often with capacities around 6-12 cubic feet, became standard in mobile applications by the mid-1960s due to their durability and multi-fuel compatibility.[22] Modern advancements since the 2000s have focused on enhancing efficiency and sustainability, including integration with solar thermal systems to utilize renewable heat sources for cooling.[23] Double-effect cycles, which employ two generators to achieve coefficients of performance (COP) up to 1.2-1.4—nearly double that of single-effect systems—have been refined for higher thermal efficiency, particularly in large-scale chillers.[24] Research into alternative absorbents, such as ionic liquids and biomass-derived solvents, aims to reduce toxicity and global warming potential compared to traditional ammonia-water or lithium bromide pairs, with studies demonstrating stable performance at lower environmental impact.[25] In the 2020s, developments in waste heat recovery have targeted data centers, where absorption systems capture low-grade exhaust heat (around 40-60°C) to drive cooling, achieving significant energy savings in hybrid setups and supporting sustainable operations in high-density facilities.[26]Thermodynamic Principles

Absorption Cycle

The absorption refrigeration cycle operates through four primary stages that facilitate cooling without mechanical compression, relying instead on thermal energy to drive the separation and recombination of a refrigerant-absorbent mixture. In the generation stage, heat is supplied to the generator, inducing an endothermic desorption process where the refrigerant vaporizes and separates from the absorbent solution, concentrating the absorbent. This vapor is then directed to the condenser. The absorption stage follows, where the refrigerant vapor, after cooling, is reabsorbed into the dilute absorbent solution in the absorber, an exothermic mixing process that releases heat to the surroundings. The condensation stage involves the refrigerant vapor releasing its latent heat to condense into a liquid at higher pressure. Finally, in the evaporation stage, the liquid refrigerant expands and evaporates at low pressure in the evaporator, absorbing latent heat from the cooled space to produce the refrigeration effect.[27][2] The performance of the cycle is quantified by the coefficient of performance (COP), defined as the ratio of the cooling provided to the total energy input: where is the heat absorbed in the evaporator (cooling capacity), is the heat supplied to the generator, and is the work input from the solution pump, which is often negligible compared to due to the low pressure differentials. Typical COP values for single-effect systems range from 0.6 to 0.75, reflecting the cycle's reliance on heat rather than work.[28][2] Irreversibilities in the cycle arise from processes such as non-equilibrium heat and mass transfer, mixing, and temperature gradients, leading to entropy generation that can be analyzed through the entropy balance equation for each component: , where accounts for irreversibilities, and exergy losses are given by with as the ambient temperature. The highest entropy generation typically occurs in the generator and absorber due to the heat of mixing and separation.[29][27] The cycle's pressure-temperature relationships are depicted on a temperature-entropy (T-s) diagram, where isobars represent constant pressure lines for the refrigerant and solution paths. Standard multi-pressure operations (typically two levels) maintain low pressure in the evaporator and absorber to enable evaporation at low temperatures, while high pressure prevails in the generator and condenser to facilitate desorption and condensation at elevated temperatures; this setup follows isobaric processes on the T-s diagram, with entropy increasing during absorption and decreasing during generation. In contrast, single-pressure variants, such as diffusion absorption cycles, operate at uniform pressure using an auxiliary inert gas to aid refrigerant diffusion, simplifying the system but often at reduced efficiency, as shown by flatter isobars on the T-s plot.[27][30][2] Heat exchangers play a crucial role in enhancing cycle efficiency by recovering sensible heat between the hot concentrated solution leaving the generator and the cool dilute solution entering it, thereby minimizing exergy losses from temperature mismatches and reducing the required generator heat input. These exchangers, often solution-to-solution types, operate on principles of counterflow to approach ideal effectiveness, lowering overall irreversibilities by up to 20-30% in optimized systems.[29][28]Working Fluids and Their Properties

The working fluids in absorption refrigerators consist of a refrigerant-absorbent pair, where the refrigerant is volatile and the absorbent has a strong affinity for it, enabling the cycle's absorption and desorption processes.[31] The most widely used pairs are ammonia-water and lithium bromide-water, selected for their thermodynamic compatibility with low-grade heat sources. Ammonia-water (NH₃-H₂O) operates at higher pressures, making it suitable for compact, small-scale units such as domestic or portable refrigerators. Ammonia serves as the refrigerant due to its low boiling point (-33°C at atmospheric pressure) and high latent heat of vaporization (approximately 1370 kJ/kg), while water acts as the absorbent with high solubility for ammonia across a wide temperature range (-80°C to 180°C).[31] The pair's vapor-liquid equilibrium follows solubility curves modeled by equations like those from Patek and Klomfar (1995), showing ammonia concentrations up to 40% by weight without phase separation.[31] However, the mixture requires rectification in the generator to remove water vapor, as residual water can freeze in the evaporator and reduce efficiency; this adds complexity but allows operation down to -50°C evaporation temperatures.[32] Regarding safety, ammonia is toxic (irritation threshold at 25 ppm) and flammable in air concentrations of 15-28%, necessitating robust containment, though its global warming potential (GWP) is 0 and ozone depletion potential (ODP) is 0. Corrosivity is moderate, primarily affecting copper but manageable with steel alloys.[33] The circulation ratio (mass flow of solution to refrigerant) is low, typically 2-10, minimizing pumping requirements while maintaining efficient heat transfer.[34] In contrast, lithium bromide-water (LiBr-H₂O) is favored for large-scale chillers operating under vacuum (evaporator pressures around 0.8-1 kPa), with water as the refrigerant and lithium bromide as the non-volatile absorbent. The solution's low vapor pressure, governed by Dühring's rule and models from Conde (2014), allows evaporation temperatures as low as 5°C without compression.[31] Solubility is high up to 70% LiBr by weight, but crystallization risks occur below 55% concentration at temperatures under 10°C, limiting use to chilled water applications above 5°C.[35] Toxicity is low, as both components are non-flammable and environmentally benign (GWP=0 for water), though LiBr's corrosivity to carbon steel and copper requires inhibitors like lithium chromate or molybdates.[31] Operating temperatures span 20-100°C, ideal for waste heat or solar-driven systems, with a high circulation ratio of 10-25, increasing solution pumping power but enabling effective absorption.[36][2] Alternative pairs include ammonia with salts like lithium nitrate (NH₃-LiNO₃) for reduced circulation ratios (around 8-10) and organic fluids such as methanol-LiBr for mid-temperature ranges, though these are less common due to stability issues.[31] Selection criteria prioritize the pair's operating temperature range to match heat source and sink (e.g., 80-100°C for single-effect cycles), circulation ratio to balance pumping versus absorption efficiency, and rectification needs to prevent evaporator fouling.[37] Environmental and safety factors, including toxicity and corrosivity, further guide choices, with non-toxic options preferred for indoor applications.[33] Emerging research as of 2025 explores ionic liquids (ILs) as absorbents, paired with ammonia or water, to address limitations of traditional fluids. Examples include [EMIM][OAc] with ammonia, offering tunable solubility via NRTL models, low vapor pressure, and operation at 25-60°C without crystallization.[31] ILs exhibit low toxicity, negligible flammability, and reduced corrosivity compared to LiBr, with environmental benefits from high thermal stability and recyclability, potentially improving COP by 20-30% in compact systems.[38] Zeolite-based solid absorbents, such as 13X or SAPO-34 with water, are under investigation for hybrid absorption-adsorption cycles, providing high uptake (up to 0.3 kg/kg) at low pressures but requiring further scaling for refrigeration efficiency.[39]| Property | Ammonia-Water | Lithium Bromide-Water | Ionic Liquids (e.g., NH₃-[EMIM][OAc]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Pressure | High (5-20 bar) | Vacuum (0.01-0.1 bar) | Moderate (1-10 bar) |

| Temperature Range | -80 to 180°C | 20 to 100°C | 25 to 60°C |

| Circulation Ratio | 2-10 | 10-25 | 10-15 |

| Toxicity | High (ammonia) | Low | Low |

| Corrosivity | Moderate | High | Low |

| GWP | 0 | 0 | 0 (negligible) |