Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Environmental degradation

View on Wikipedia

Environmental degradation is the deterioration of the environment through depletion of resources such as quality of air, water and soil; the destruction of ecosystems; habitat destruction; the extinction of wildlife; and pollution. It is defined as any change or disturbance to the environment perceived to be deleterious or undesirable.[1][2] The environmental degradation process amplifies the impact of environmental issues which leave lasting impacts on the environment.[citation needed]

Environmental degradation is one of the ten threats officially cautioned by the High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change of the United Nations. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction defines environmental degradation as "the reduction of the capacity of the environment to meet social and ecological objectives, and needs".[3]

Environmental degradation comes in many types. When natural habitats are destroyed or natural resources are depleted, the environment is degraded; direct environmental degradation, such as deforestation, which is readily visible; this can be caused by more indirect process, such as the build up of plastic pollution over time or the buildup of greenhouse gases that causes tipping points in the climate system. Efforts to counteract this problem include environmental protection and environmental resources management. Mismanagement that leads to degradation can also lead to environmental conflict where communities organize in opposition to the forces that mismanaged the environment.

Biodiversity loss

[edit]

Scientists assert that human activity has pushed the earth into a sixth mass extinction event.[4][5] The loss of biodiversity has been attributed in particular to human overpopulation, continued human population growth and overconsumption of natural resources by the world's wealthy.[6][7] A 2020 report by the World Wildlife Fund found that human activity – specifically overconsumption, population growth and intensive farming – has destroyed 68% of vertebrate wildlife since 1970.[8] The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, published by the United Nation's IPBES in 2019, posits that roughly one million species of plants and animals face extinction from anthropogenic causes, such as expanding human land use for industrial agriculture and livestock rearing, along with overfishing.[9][10][11]

Since the establishment of agriculture over 11,000 years ago, humans have altered roughly 70% of the Earth's land surface, with the global biomass of vegetation being reduced by half, and terrestrial animal communities seeing a decline in biodiversity greater than 20% on average.[12][13] A 2021 study says that just 3% of the planet's terrestrial surface is ecologically and faunally intact, meaning areas with healthy populations of native animal species and little to no human footprint. Many of these intact ecosystems were in areas inhabited by indigenous peoples.[14][15] With 3.2 billion people affected globally, degradation affects over 30% of the world's land area and 40% of land in developing countries.[16]

The implications of these losses for human livelihoods and wellbeing have raised serious concerns. With regard to the agriculture sector for example, The State of the World's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture, published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2019,[17] states that "countries report that many species that contribute to vital ecosystem services, including pollinators, the natural enemies of pests, soil organisms and wild food species, are in decline as a consequence of the destruction and degradation of habitats, overexploitation, pollution and other threats" and that "key ecosystems that deliver numerous services essential to food and agriculture, including supply of freshwater, protection against hazards and provision of habitat for species such as fish and pollinators, are declining."[18]

Impacts of environmental degradation on women's livelihoods

[edit]On the way biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation impact livelihoods, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations finds also that in contexts of degraded lands and ecosystems in rural areas, both girls and women bear heavier workloads.

Women's livelihoods, health, food and nutrition security, access to water and energy, and coping abilities are all disproportionately affected by environmental degradation. Environmental pressures and shocks, particularly in rural areas, force women to deal with the aftermath, greatly increasing their load of unpaid care work. Also, as limited natural resources grow even scarcer due to climate change, women and girls must also walk further to collect food, water or firewood, which heightens their risk of being subjected to gender-based violence.[19]

This implies, for example, longer journeys to get primary necessities and greater exposure to the risks of human trafficking, rape, and sexual violence.[20]

Water degradation

[edit]

One major component of environmental degradation is the depletion of the resource of fresh water on Earth.[22] Approximately only 2.5% of all of the water on Earth is fresh water, with the rest being salt water. 69% of fresh water is frozen in ice caps located on Antarctica and Greenland, so only 30% of the 2.5% of fresh water is available for consumption.[23] Fresh water is an exceptionally important resource, since life on Earth is ultimately dependent on it. Water transports nutrients, minerals and chemicals within the biosphere to all forms of life, sustains both plants and animals, and moulds the surface of the Earth with transportation and deposition of materials.[24]

The current top three uses of fresh water account for 95% of its consumption; approximately 85% is used for irrigation of farmland, golf courses, and parks, 6% is used for domestic purposes such as indoor bathing uses and outdoor garden and lawn use, and 4% is used for industrial purposes such as processing, washing, and cooling in manufacturing centres.[25] It is estimated that one in three people over the entire globe are already facing water shortages, almost one-fifth of the world population live in areas of physical water scarcity, and almost one quarter of the world's population live in a developing country that lacks the necessary infrastructure to use water from available rivers and aquifers. Water scarcity is an increasing problem due to many foreseen issues in the future including population growth, increased urbanization, higher standards of living, and climate change.[23]

Industrial and domestic sewage, pesticides, fertilizers, plankton blooms, silt, oils, chemical residues, radioactive material, and other pollutants are some of the most frequent water pollutants. These have a huge negative impact on the water and can cause degradation in various levels.[19]

Climate change and temperature

[edit]Climate change affects the Earth's water supply in a large number of ways. It is predicted that the mean global temperature will rise in the coming years due to a number of forces affecting the climate. The amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) will rise, and both of these will influence water resources; evaporation depends strongly on temperature and moisture availability which can ultimately affect the amount of water available to replenish groundwater supplies.

Transpiration from plants can be affected by a rise in atmospheric CO2, which can decrease their use of water, but can also raise their use of water from possible increases of leaf area. Temperature rise can reduce the snow season in the winter and increase the intensity of the melting snow leading to peak runoff of this, affecting soil moisture, flood and drought risks, and storage capacities depending on the area.[26]

Warmer winter temperatures cause a decrease in snowpack, which can result in diminished water resources during summer. This is especially important at mid-latitudes and in mountain regions that depend on glacial runoff to replenish their river systems and groundwater supplies, making these areas increasingly vulnerable to water shortages over time; an increase in temperature will initially result in a rapid rise in water melting from glaciers in the summer, followed by a retreat in glaciers and a decrease in the melt and consequently the water supply every year as the size of these glaciers get smaller and smaller.[23]

Thermal expansion of water and increased melting of oceanic glaciers from an increase in temperature gives way to a rise in sea level. This can affect the freshwater supply to coastal areas as well. As river mouths and deltas with higher salinity get pushed further inland, an intrusion of saltwater results in an increase of salinity in reservoirs and aquifers.[25] Sea-level rise may also consequently be caused by a depletion of groundwater,[27] as climate change can affect the hydrologic cycle in a number of ways. Uneven distributions of increased temperatures and increased precipitation around the globe results in water surpluses and deficits,[26] but a global decrease in groundwater suggests a rise in sea level, even after meltwater and thermal expansion were accounted for,[27] which can provide a positive feedback to the problems sea-level rise causes to fresh-water supply.

A rise in air temperature results in a rise in water temperature, which is also very significant in water degradation as the water would become more susceptible to bacterial growth. An increase in water temperature can also affect ecosystems greatly because of a species' sensitivity to temperature, and also by inducing changes in a body of water's self-purification system from decreased amounts of dissolved oxygen in the water due to rises in temperature.[23]

Climate change and precipitation

[edit]A rise in global temperatures is also predicted to correlate with an increase in global precipitation but because of increased runoff, floods, increased rates of soil erosion, and mass movement of land, a decline in water quality is probable, because while water will carry more nutrients it will also carry more contaminants.[23] While most of the attention about climate change is directed towards global warming and greenhouse effect, some of the most severe effects of climate change are likely to be from changes in precipitation, evapotranspiration, runoff, and soil moisture. It is generally expected that, on average, global precipitation will increase, with some areas receiving increases and some decreases.

Climate models show that while some regions should expect an increase in precipitation,[26] such as in the tropics and higher latitudes, other areas are expected to see a decrease, such as in the subtropics. This will ultimately cause a latitudinal variation in water distribution.[23] The areas receiving more precipitation are also expected to receive this increase during their winter and actually become drier during their summer,[26] creating even more of a variation of precipitation distribution. Naturally, the distribution of precipitation across the planet is very uneven, causing constant variations in water availability in respective locations.

Changes in precipitation affect the timing and magnitude of floods and droughts, shift runoff processes, and alter groundwater recharge rates. Vegetation patterns and growth rates will be directly affected by shifts in precipitation amount and distribution, which will in turn affect agriculture as well as natural ecosystems. Decreased precipitation will deprive areas of water causing water tables to fall and reservoirs of wetlands, rivers, and lakes to empty.[26] In addition, a possible increase in evaporation and evapotranspiration will result, depending on the accompanied rise in temperature.[25] Groundwater reserves will be depleted, and the remaining water has a greater chance of being of poor quality from saline or contaminants on the land surface.[23]

Climate change is resulting into a very high rate of land degradation causing enhanced desertification and nutrient deficient soils. The menace of land degradation is increasing by the day and has been characterized as a major global threat. According to Global Assessment of Land Degradation and Improvement (GLADA) a quarter of land area around the globe can now be marked as degraded. Land degradation is supposed to influence lives of 1.5 billion people and 15 billion tons of fertile soil is lost every year due to anthropogenic activities and climate change.[28]

Population growth

[edit]

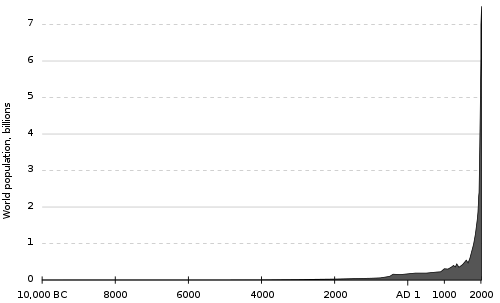

The human population on Earth is expanding rapidly, which together with even more rapid economic growth is the main cause of the degradation of the environment.[29] Humanity's appetite for resources is disrupting the environment's natural equilibrium. Production industries are venting smoke into the atmosphere and discharging chemicals that are polluting water resources. The smoke includes detrimental gases such as carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide. The high levels of pollution in the atmosphere form layers that are eventually absorbed into the atmosphere. Organic compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) have generated an opening in the ozone layer, which admits higher levels of ultraviolet radiation, putting the globe at risk.

The available fresh water being affected by the climate is also being stretched across an ever-increasing global population. It is estimated that almost a quarter of the global population is living in an area that is using more than 20% of their renewable water supply; water use will rise with population while the water supply is also being aggravated by decreases in streamflow and groundwater caused by climate change. Even though some areas may see an increase in freshwater supply from an uneven distribution of precipitation increase, an increased use of water supply is expected.[30]

An increased population means increased withdrawals from the water supply for domestic, agricultural, and industrial uses, the largest of these being agriculture,[31] believed to be the major non-climate driver of environmental change and water deterioration. The next 50 years will likely be the last period of rapid agricultural expansion, but the larger and wealthier population over this time will demand more agriculture.[32]

Population increase over the last two decades, at least in the United States, has also been accompanied by a shift to an increase in urban areas from rural areas,[33] which concentrates the demand for water into certain areas, and puts stress on the fresh water supply from industrial and human contaminants.[23] Urbanization causes overcrowding and increasingly unsanitary living conditions, especially in developing countries, which in turn exposes an increasingly number of people to disease. About 79% of the world's population is in developing countries, which lack access to sanitary water and sewer systems, giving rises to disease and deaths from contaminated water and increased numbers of disease-carrying insects.[34]

Agriculture

[edit]

Agriculture is dependent on available soil moisture, which is directly affected by climate dynamics, with precipitation being the input in this system and various processes being the output, such as evapotranspiration, surface runoff, drainage, and percolation into groundwater. Changes in climate, especially the changes in precipitation and evapotranspiration predicted by climate models, will directly affect soil moisture, surface runoff, and groundwater recharge.

In areas with decreasing precipitation as predicted by the climate models, soil moisture may be substantially reduced.[26] With this in mind, agriculture in most areas already needs irrigation, which depletes fresh water supplies both by the physical use of the water and the degradation agriculture causes to the water. Irrigation increases salt and nutrient content in areas that would not normally be affected, and damages streams and rivers from damming and removal of water. Fertilizer enters both human and livestock waste streams that eventually enter groundwater, while nitrogen, phosphorus, and other chemicals from fertilizer can acidify both soils and water. Certain agricultural demands may increase more than others with an increasingly wealthier global population, and meat is one commodity expected to double global food demand by 2050,[32] which directly affects the global supply of fresh water. Cows need water to drink, more if the temperature is high and humidity is low, and more if the production system the cow is in is extensive, since finding food takes more effort. Water is needed in the processing of the meat, and also in the production of feed for the livestock. Manure can contaminate bodies of freshwater, and slaughterhouses, depending on how well they are managed, contribute waste such as blood, fat, hair, and other bodily contents to supplies of fresh water.[36]

The transfer of water from agricultural to urban and suburban use raises concerns about agricultural sustainability, rural socioeconomic decline, food security, an increased carbon footprint from imported food, and decreased foreign trade balance.[31] The depletion of fresh water, as applied to more specific and populated areas, increases fresh water scarcity among the population and also makes populations susceptible to economic, social, and political conflict in a number of ways; rising sea levels forces migration from coastal areas to other areas farther inland, pushing populations closer together breaching borders and other geographical patterns, and agricultural surpluses and deficits from the availability of water induce trade problems and economies of certain areas.[30] Climate change is an important cause of involuntary migration and forced displacement[37] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, global greenhouse gas emissions from animal agriculture exceeds that of transportation.[38]

Water management

[edit]

Water management is the process of planning, developing, and managing water resources across all water applications, in terms of both quantity and quality." Water management is supported and guided by institutions, infrastructure, incentives, and information systems.[39]

The issue of the depletion of fresh water has stimulated increased efforts in water management.[24] While water management systems are often flexible, adaptation to new hydrologic conditions may be very costly.[26] Preventative approaches are necessary to avoid high costs of inefficiency and the need for rehabilitation of water supplies,[24] and innovations to decrease overall demand may be important in planning water sustainability.[31]

Water supply systems, as they exist now, were based on the assumptions of the current climate, and built to accommodate existing river flows and flood frequencies. Reservoirs are operated based on past hydrologic records, and irrigation systems on historical temperature, water availability, and crop water requirements; these may not be a reliable guide to the future. Re-examining engineering designs, operations, optimizations, and planning, as well as re-evaluating legal, technical, and economic approaches to manage water resources are very important for the future of water management in response to water degradation. Another approach is water privatization; despite its economic and cultural effects, service quality and overall quality of the water can be more easily controlled and distributed. Rationality and sustainability is appropriate, and requires limits to overexploitation and pollution and efforts in conservation.[24]

Consumption increases

[edit]As the world's population increases, it is accompanied by an increase in population demand for natural resources. With the need for more production increases comes more damage to the environments and ecosystems in which those resources are housed. According to United Nations' population growth predictions, there could be up to 170 million more births by 2070. The need for more fuel, energy, food, buildings, and water sources grows with the number of people on the planet.

However, the scale of environmental degradation is not only determined by population growth but also by consumption patterns and resource efficiency. Industrialized nations, with higher per capita consumption rates, often have a disproportionately large environmental footprint compared to less developed regions. Efforts to adopt sustainable development practices, including renewable energy, recycling, and waste reduction, could mitigate some of the environmental impacts of increased consumption. Furthermore, promoting circular economies and transitioning to low-impact technologies are critical.

Deforestation

[edit]As the need for new agricultural areas and road construction increases, the deforestation processes stay in effect. Deforestation is the "removal of forest or stand of trees from land that is converted to non-forest use." (Wikipedia-Deforestation). Since the 1960s, nearly 50% of tropical forests have been destroyed, but this process is not limited to tropical forest areas. Europe's forests are also destroyed by livestock, insects, diseases, invasive species, and other human activities. Many of the world's terrestrial biodiversity can be found living in different types of forests. Tearing down these areas for increased consumption directly decreases the world's biodiversity of plant and animal species native to those areas.

Along with destroying habitats and ecosystems, decreasing the world's forest contributes to the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. By taking away forested areas, we are limiting the amount of carbon reservoirs, limiting it to the largest ones: the atmosphere and oceans. While one of the biggest reasons for deforestation is agriculture use for the world's food supply, removing trees from landscapes also increases erosion rates in areas, making it harder to produce crops in those soil types.

Adaption to Degradation

[edit]Frogs manage the level of salt in their bodies.[40][41][42][43][44][45] Though, all frogs will die in salty enough water. The most tolerant frog, the Crab-eating frog, can tolerate up to 75% salinity of seawater, and can live long term in 2/3s salinity of seawater.[46] Many populations of frogs are not adapting fast enough to survive the increase in saline conditions.[47][48][49][50] Many populations of species of frogs are currently adapting to tolerate higher salinity across various environments.[51][52][53][54] The amount of salt that a frog is able to tolerate at a specific time is different from the amount of salt they are able to tolerate long term, and the different life stages usually don't have the same amount of salt tolerance, with embryos the least salt tolerant, and the tadpoles of some frogs the most salt tolerant.[55][56] Salt can also cause bottlenecks in local populations of frogs, as many frogs die from exposure, reducing genetic diversity, which can exacerbate impacts of disease for the population.[57]

Increasing salinity is driven by human-led freshwater salinization, such as from runoff from icing roadways, from pollutants from agriculture, from mining contaminants, and from the intrusions of seas as sea levels rise.[58] Some frog's adaptation is due to naturally slightly saline ecosystems, such as brackish water in estuaries or mangrove swamps.[59] Some kinds of salt may affect frogs differently than other kinds of salt, but because road salt and saltwater intrusion are the most common kinds of salt exposure, sodium chloride is the most well studied salt with regard to its effects on frogs.[60] The Crab-eating frog, and some of its relatives, are the most well known examples of frogs with high salt tolerance. They are unique among frogs for eating a lot of crabs (when in coastal environments), and appear to be the frogs best able to tolerate salty conditions. The American green tree frog has an ecotype which is better adapted to the salty conditions of the brackish swamps of the Atlantic coasts of the US than their relatives inland in freshwater conditions. The Eurasian green toad, the Natterjack toad, and the cane toad also show salt tolerance. Some populations of the wood frog through exposure to road salts show some adaptations toward salt tolerance. The Spiny toad from Western Europe is more salt tolerant in inland than coastal populations, which is possibly due to inland individuals just being larger from having to burn less energy dealing with salt stress.

Changes in salinity also go hand in hand with other changes to an ecosystem that are harmful to the frogs. The combined effects of heat stress and salt stress on many populations of frogs are worse than either stress acting alone. Additionally, some populations of wood frogs from salty water show worse reflexes and lower activity levels than their freshwater counterparts, which may make them more vulnerable to predation than freshwater frogs. Male wood frogs raised in salty pools also can experience dangerous amounts of edema, or swelling with water, after overwintering.[61] Wood frogs are well studied due to their predictable mass breedings, large numbers, and wide range, as well as the abundance of roads which freeze over next to potential breeding pools.[62][63]

One important way frogs in general deal with salty conditions is by upregulating the genes for hormones which help transport salt across osmotic membranes, such as angiotensin II and aldosterone (used by Crab-eating frogs),[64] or arginine vasotocin (used by cane toads).[65] In crab eating frogs, these genes have been shown to be expressed in the skin, the kidney, and the bladder, where frogs do most of their water exchange.[66] Another method is to increase production of osmolytes such as glycerol or urea to help absorb more water into their cells to better balance the osmotic pressure.[67][68] One way some populations of frogs are dealing with salt is simply to produce larger eggs, because larger larvae tolerate salt better.[69] Another is modification of ion transporter in the cell and vacuole walls, to better remove salts from the cells.[70] The proteins which make cells structured also show changes, specifically weakening, to allow the cytoskeleton to be more flexible and better deal with the physical stresses from salt exposure.[71] Experimentally, eggs exposed to salt in wood frogs, lead to frogs and tadpoles which are better adapted to tolerate the salt, when compared to frogs hatched from freshwater-raised eggs.[72]

The mechanisms which frogs use to tolerate salty water are also observed in different species. The Tiger salamander and the Spotted salamander also have some salt tolerance.[73][74] The adaptations to saltwater seen in frogs are similar to those in fishes moving between salt and freshwater, such as killifish.[75] Glycerol is used as an osmolyte by even yeasts, insects, and plants (see salt tolerance of crops).[76] Urea in higher amounts in the cells of some mammals which have evolved to live in saltwater.[77] Fishes are especially comparable because they share a level of skin permeability with amphibians.[78]

See also

[edit]- Anthropocene

- Environmental change

- Environmental issues

- Ecological collapse

- Ecological crisis

- Ecologically sustainable development

- Eco-socialism

- Exploitation of natural resources

- Human impact on the environment

- I=PAT

- Restoration ecology

- United Nations Decade on Biodiversity

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- World Resources Institute (WRI)

References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, D. L.; Ambrose, S. H.; Bassett, T. J.; Bowen, M. L.; Crummey, D. E.; Isaacson, J. S.; Johnson, D. N.; Lamb, P.; Saul, M.; Winter-Nelson, A. E. (1 May 1997). "Meanings of Environmental Terms". Journal of Environmental Quality. 26 (3): 581–589. Bibcode:1997JEnvQ..26..581J. doi:10.2134/jeq1997.00472425002600030002x.

- ^ Yeganeh, Kia Hamid (1 January 2020). "A typology of sources, manifestations, and implications of environmental degradation". Management of Environmental Quality. 31 (3): 765–783. Bibcode:2020MEnvQ..31..765Y. doi:10.1108/MEQ-02-2019-0036.

- ^ "Terminology". The International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. 2004-03-31. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-9299-8.

- ^ Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342.

Moreover, we have unleashed a mass extinction event, the sixth in roughly 540 million years, wherein many current life forms could be annihilated or at least committed to extinction by the end of this century.

- ^ Pimm, S. L.; Jenkins, C. N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T. M.; Gittleman, J. L.; Joppa, L. N.; Raven, P. H.; Roberts, C. M.; Sexton, J. O. (30 May 2014). "The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection" (PDF). Science. 344 (6187) 1246752. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. PMID 24876501. S2CID 206552746.

The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption.

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dirzo, Rodolfo (23 May 2017). "Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines". PNAS. 114 (30): E6089 – E6096. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E6089C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704949114. PMC 5544311. PMID 28696295.

Much less frequently mentioned are, however, the ultimate drivers of those immediate causes of biotic destruction, namely, human overpopulation and continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich. These drivers, all of which trace to the fiction that perpetual growth can occur on a finite planet, are themselves increasing rapidly.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (September 9, 2020). "Humans exploiting and destroying nature on unprecedented scale – report". The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Plumer, Brad (May 6, 2019). "Humans Are Speeding Extinction and Altering the Natural World at an 'Unprecedented' Pace". The New York Times. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

Human actions threaten more species with global extinction now than ever before," the report concludes, estimating that "around 1 million species already face extinction, many within decades, unless action is taken.

- ^ Vidal, John (March 15, 2019). "The Rapid Decline Of The Natural World Is A Crisis Even Bigger Than Climate Change". The Huffington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

"The food system is the root of the problem. The cost of ecological degradation is not considered in the price we pay for food, yet we are still subsidizing fisheries and agriculture." - Mark Rounsevell

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (May 6, 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Beattie, Andrew; Ceballos, Gerardo; Crist, Eileen; Diamond, Joan; Dirzo, Rodolfo; Ehrlich, Anne H.; Harte, John; Harte, Mary Ellen; Pyke, Graham; Raven, Peter H.; Ripple, William J.; Saltré, Frédérik; Turnbull, Christine; Wackernagel, Mathis; Blumstein, Daniel T. (2021). "Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 1. Bibcode:2021FrCS....1.5419B. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2020.615419.

- ^ Specktor, Brandon (January 15, 2021). "The planet is dying faster than we thought". Live Science. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (April 15, 2021). "Just 3% of world's ecosystems remain intact, study suggests". The Guardian. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Plumptre, Andrew J.; Baisero, Daniele; et al. (2021). "Where Might We Find Ecologically Intact Communities?". Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 4. Bibcode:2021FrFGC...4.6635P. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2021.626635. hdl:10261/242175.

- ^ Bekele, Adugna Eneyew; Drabik, Dusan; Dries, Liesbeth; Heijman, Wim (30 January 2021). "Large-scale land investments, household displacement, and the effect on land degradation in semiarid agro-pastoral areas of Ethiopia". Land Degradation & Development. 32 (2): 777–791. Bibcode:2021LDeDe..32..777B. doi:10.1002/ldr.3756.

- ^ The State of the World's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture (PDF). Rome: FAO. 2019. ISBN 978-92-5-131270-4.

- ^ In brief − The state of the World's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture (PDF). FAO. 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2019. Alt URL

- ^ a b "Empower Women - Impact of climate change, environmental degradation and natural disasters on women's livelihoods". EmpowerWomen. 28 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ Women's leadership and gender equality in climate action and disaster risk reduction in Africa − A call for action. Accra: FAO & The African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb7431en. ISBN 978-92-5-135234-2. S2CID 243488592.

- ^ "In Africa, War Over Water Looms As Ethiopia Nears Completion Of Nile River Dam". NPR. 27 February 2018.

- ^ Warner, K.; Hamza, H.; Oliver-Smith, A.; Renaud, F.; Julca, A. (December 2010). "Climate change, environmental degradation and migration". Natural Hazards. 55 (3): 689–715. Bibcode:2010NatHa..55..689W. doi:10.1007/s11069-009-9419-7. S2CID 144843784.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Water." Archived 2011-12-06 at the Wayback Machine Climate Institute. Web. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ^ a b c d Young, Gordon J., James Dooge, and John C. Rodda. Global Water Resource Issues. Cambridge UP, 2004.

- ^ a b c Frederick, Kenneth D., and David C. Major. "Climate Change and Water Resources." Climatic Change 37.1 (1997): p 7-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ragab, Ragab, and Christel Prudhomme. "Soil and Water: Climate Change and Water Resources Management in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions: Prospective Challenges for the 21st Century". Biosystems Engineering 81.1 (2002): p 3-34.

- ^ a b Konikow, Leonard F. "Contribution of Global Groundwater Depletion since 1990 to Sea-level Rise". Geophysical Research Letters 38.17 (2011).

- ^ Arora, Naveen Kumar (2019-06-01). "Impact of climate change on agriculture production and its sustainable solutions". Environmental Sustainability. 2 (2): 95–96. Bibcode:2019ESust...2...95A. doi:10.1007/s42398-019-00078-w. ISSN 2523-8922.

- ^ Cafaro, Philip (2022). "Reducing Human Numbers and the Size of our Economies is Necessary to Avoid a Mass Extinction and Share Earth Justly with Other Species". Philosophia. 50 (5): 2263–2282. doi:10.1007/s11406-022-00497-w. S2CID 247433264.

- ^ a b Raleigh, Clionadh, and Henrik Urdal. "Climate Change, Environmental Degradation, and Armed Conflict." Political Geography 26.6 (2007): 674–94.

- ^ a b c MacDonald, Glen M. "Water, Climate Change, and Sustainability in the Southwest". PNAS 107.50 (2010): p 56-62.

- ^ a b Tilman, David, Joseph Fargione, Brian Wolff, Carla D'Antonio, Andrew Dobson, Robert Howarth, David Scindler, William Schlesinger, Danielle Simberloff, and Deborah Swackhamer. "Forecasting Agriculturally Driven Global Environmental Change". Science 292.5515 (2011): p 281-84.

- ^ Wallach, Bret. Understanding the Cultural Landscape. New York; Guilford, 2005.

- ^ [1] Archived 2017-12-17 at the Wayback Machine. Powell, Fannetta. "Environmental Degradation and Human Disease". Lecture. SlideBoom. 2009. Web. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Butler, Rhett A. (31 March 2021). "Global forest loss increases in 2020". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. ● Data from "Indicators of Forest Extent / Forest Loss". World Resources Institute. 4 April 2024. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Chart in section titled "Annual rates of global tree cover loss have risen since 2000".

- ^ "Environmental Implications of the Global Demand for Red Meat"[permanent dead link]. Web. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ^ Bogumil Terminski, Environmentally-Induced Displacement. Theoretical Frameworks and Current Challenges cedem.ulg.ac.be Archived 2013-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wang, George C. (April 9, 2017). "Go vegan, save the planet". CNN. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ^ "Water Resource Management: our essential guide to water resource management objectives, policy & strategies". www.aquatechtrade.com. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ ''Molecular mechanisms of local adaptation for salt-tolerance in a treefrog - PubMed." Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655636/

- ^ R. Relyea, B. Mattes, C. Schermerhorn, and I. Shepard, "Freshwater salinization and the evolved tolerance of amphibians," Ecol. Evol., vol. 14, no. 3, p. e11069, 2024, doi: 10.1002/ece3.11069.

- ^ L. Lorrain-Soligon et al., "Salty surprises: Developmental and behavioral responses to environmental salinity reveal higher tolerance of inland rather than coastal Bufo spinosus tadpoles," Environ. Res., vol. 264, no. Pt 2, p. 120401, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120401.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ R. Relyea, B. Mattes, C. Schermerhorn, and I. Shepard, "Freshwater salinization and the evolved tolerance of amphibians," Ecol. Evol., vol. 14, no. 3, p. e11069, 2024, doi: 10.1002/ece3.11069.

- ^ L. Lorrain-Soligon et al., "Salty surprises: Developmental and behavioral responses to environmental salinity reveal higher tolerance of inland rather than coastal Bufo spinosus tadpoles," Environ. Res., vol. 264, no. Pt 2, p. 120401, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120401.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ R. Relyea, B. Mattes, C. Schermerhorn, and I. Shepard, "Freshwater salinization and the evolved tolerance of amphibians," Ecol. Evol., vol. 14, no. 3, p. e11069, 2024, doi: 10.1002/ece3.11069.

- ^ L. Lorrain-Soligon et al., "Salty surprises: Developmental and behavioral responses to environmental salinity reveal higher tolerance of inland rather than coastal Bufo spinosus tadpoles," Environ. Res., vol. 264, no. Pt 2, p. 120401, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120401.

- ^ R. Relyea, B. Mattes, C. Schermerhorn, and I. Shepard, "Freshwater salinization and the evolved tolerance of amphibians," Ecol. Evol., vol. 14, no. 3, p. e11069, 2024, doi: 10.1002/ece3.11069.

- ^ L. Lorrain-Soligon et al., "Salty surprises: Developmental and behavioral responses to environmental salinity reveal higher tolerance of inland rather than coastal Bufo spinosus tadpoles," Environ. Res., vol. 264, no. Pt 2, p. 120401, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120401.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ L. M. Conner et al., "Population origin and heritable effects mediate road salt toxicity and thermal stress in an amphibian," Chemosphere, vol. 357, p. 141978, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141978.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ L. Lorrain-Soligon et al., "Salty surprises: Developmental and behavioral responses to environmental salinity reveal higher tolerance of inland rather than coastal Bufo spinosus tadpoles," Environ. Res., vol. 264, no. Pt 2, p. 120401, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120401.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ ''Molecular mechanisms of local adaptation for salt-tolerance in a treefrog - PubMed." Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655636/

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ Y. Shao et al., "Transcriptomes reveal the genetic mechanisms underlying ionic regulatory adaptations to salt in the crab-eating frog," Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 17551, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1038/srep17551.

- ^ S. P. Brady, S. J. Kang, Z. S. Wang, C. D. Layne, and R. Calsbeek, "Freshwater salinization leads to sluggish, bloated frogs and small, cramped embryos but adaptive countergradient variation in eggs," Integr. Comp. Biol., p. icaf008, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1093/icb/icaf008.

- ^ R. Relyea, B. Mattes, C. Schermerhorn, and I. Shepard, "Freshwater salinization and the evolved tolerance of amphibians," Ecol. Evol., vol. 14, no. 3, p. e11069, 2024, doi: 10.1002/ece3.11069.

- ^ L. Lorrain-Soligon et al., "Salty surprises: Developmental and behavioral responses to environmental salinity reveal higher tolerance of inland rather than coastal Bufo spinosus tadpoles," Environ. Res., vol. 264, no. Pt 2, p. 120401, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.120401.

- ^ ''Molecular mechanisms of local adaptation for salt-tolerance in a treefrog - PubMed." Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655636/

- ^ ''Molecular mechanisms of local adaptation for salt-tolerance in a treefrog - PubMed." Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655636/

- ^ ''Molecular mechanisms of local adaptation for salt-tolerance in a treefrog - PubMed." Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655636/

- ^ ''Molecular mechanisms of local adaptation for salt-tolerance in a treefrog - PubMed." Accessed: Mar. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33655636/

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of the World's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture − In Brief, FAO, FAO. Get the Lead Out: The Poisoning Threat From Tainted Hunting ...

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of the World's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture − In Brief, FAO, FAO. Get the Lead Out: The Poisoning Threat From Tainted Hunting ...

External links

[edit]- Ecology of Increasing Disease Population growth and environmental degradation

- "Reintegrating Land and Livestock." Union of Concerned Scientists

- "Deforestation and Forest Degradation." IUCN, 7 July 2022.

- Environmental Change in the Kalahari: Integrated Land Degradation Studies for Nonequilibrium Dryland Environments in the Annals of the Association of American Geographers

- Public Daily Brief Threat: Environmental Degradation

- Focus: Environmental degradation is contributing to health threats worldwide Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Systems-Water Reactors

- Herndon and Gibbon Lieutenants United States Navy The First North American Explorers of the Amazon Valley, by Historian Normand E. Klare. Actual Reports from the explorers are compared with present Amazon Basin conditions.

- World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations.

- Environmental Degradation Index by Jha & Murthy (for 174 countries)

Environmental degradation

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Conceptual Framework

Core Definition and Scope

Environmental degradation denotes the deterioration of the natural environment through the depletion of resources such as air, water, and soil; the destruction of ecosystems; and the impairment of biodiversity, which collectively diminishes the capacity of ecosystems to provide essential services like clean water filtration, carbon sequestration, and habitat support.[10][11] This process often manifests as long-term reductions in environmental quality, measurable through indicators including soil nutrient loss, species extinction rates, and pollutant concentrations exceeding natural baselines.[12] The scope of environmental degradation extends beyond isolated incidents to systemic changes affecting biotic and abiotic components of ecosystems, including land degradation via erosion and desertification, water contamination from industrial effluents and agricultural runoff, air pollution from emissions of particulate matter and greenhouse gases, and biodiversity decline through habitat fragmentation and overexploitation.[13][14] These elements interact causally; for instance, deforestation not only reduces tree cover—global losses reached 420 million hectares between 1990 and 2020—but also exacerbates soil erosion and alters hydrological cycles, amplifying downstream degradation.[15] While natural processes like volcanic eruptions or wildfires can contribute to temporary environmental alterations, the term predominantly applies to anthropogenic accelerations that exceed natural recovery rates, as evidenced by human-induced factors accounting for over 75% of terrestrial biodiversity loss since 1970.[16][17] Quantifying scope requires empirical metrics, such as the Environmental Performance Index, which tracks degradation via variables like ecosystem vitality and environmental health, revealing that 71% of countries experienced worsening trends in at least one category from 2012 to 2022.[18] This breadth underscores degradation's role in undermining human welfare, including reduced agricultural productivity—global crop yields declined by up to 20% in degraded soils—and heightened vulnerability to extreme weather, without conflating it with reversible natural fluctuations.[19][20]Causal Models like IPAT

The IPAT model, expressed as I = P × A × T, quantifies environmental impact (I) as the multiplicative product of population size (P), affluence (A, measured as per capita consumption or GDP), and technology (T, defined as the environmental impact per unit of consumption).[21] Formulated by Paul R. Ehrlich and John P. Holdren in 1971, the equation aimed to dissect the drivers of ecological strain amid rapid postwar population and economic growth, emphasizing that impacts intensify unless technological efficiencies offset expansions in population and consumption.[22] Ehrlich and Holdren applied it to predict resource depletion and pollution trajectories, arguing that affluent societies' high consumption amplifies per capita effects far beyond those in low-income regions.[23] In practice, IPAT has informed analyses of degradation metrics like CO2 emissions and land use change; for instance, decompositions attribute roughly 30-50% of historical emissions growth to population, 20-40% to affluence, and the remainder to technology's varying efficiency.[23][24] The model's multiplicative structure highlights causal realism: even modest population or affluence increases can exponentially elevate impacts if technology fails to decouple them, as observed in global deforestation rates correlating with GDP per capita rises since 1970.[21] Empirical extensions, such as in ecological economics, use IPAT to simulate scenarios where stabilizing population below 10 billion by 2100 could halve projected biodiversity loss under constant affluence-technology assumptions.[25] Critics contend IPAT oversimplifies by assuming fixed elasticities and ignoring synergies, such as policy or cultural factors modulating T, leading to interpretive pitfalls like overattributing blame to population without disaggregating consumption disparities.[23] It treats variables as independent, yet affluence often drives technological innovation, confounding isolation of effects; moreover, definitional ambiguities in T—encompassing efficiency gains but also rebound effects from cheaper resources—undermine precise forecasting.[21] Some analyses fault it for underemphasizing institutional drivers of degradation in developing contexts, where poverty exacerbates local impacts despite low global affluence shares.[25] To address these, the STIRPAT extension (Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence, and Technology), developed by York, Rosa, and Dietz in 2003, reformulates IPAT as a logarithmic regression model (ln I = a + b ln P + c ln A + d ln T + e), enabling statistical hypothesis testing, non-proportional effects, and incorporation of covariates like urbanization.[26] STIRPAT regressions on panel data from 1970-2020 consistently affirm positive elasticities for P and A (often 0.5-1.0) against emissions, with T showing weaker decoupling in high-income nations, supporting IPAT's core logic while allowing empirical falsification.[27] These models underscore that absolute reductions in degradation require curbing P and A growth, as technological offsets have historically yielded only relative improvements, not sufficiency against observed trends like a 50% rise in global material footprint since 2000.[26][23]Historical Development

Pre-Modern Patterns

Environmental degradation in pre-modern societies often stemmed from agricultural intensification, urbanization, and resource extraction to support growing populations, resulting in localized deforestation, soil erosion, and salinization that constrained long-term sustainability. In ancient Mesopotamia, irrigation systems expanded arable land along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers from around 4000 BCE, but poor drainage led to progressive soil salinization as evaporated irrigation water left behind mineral salts, reducing crop yields. By 2400–1700 BCE, Sumerian records indicate barley production declined from an average of 30–40 kor per hectare to under 20 kor, contributing to the shift from wheat to more salt-tolerant barley and eventual abandonment of southern farmlands.[28][29] In the Mediterranean basin, civilizations such as those in Greece and Rome accelerated deforestation for timber, agriculture, and shipbuilding, with proxy evidence from pollen cores showing widespread clearance of oak and pine forests by 1000 BCE in regions like northwest Syria's Ghab Valley. Roman expansion from the 3rd century BCE onward cleared vast tracts for villas, mines, and fleets—consuming an estimated 1–2 million cubic meters of wood annually at peak—exacerbating soil erosion on hillsides and silting rivers, which diminished agricultural productivity and expanded malarial wetlands through stagnant marshes.[30][31][32] Among the Maya of the Yucatán lowlands, population growth to over 5 million by 800 CE drove slash-and-burn agriculture that deforested up to 40–60% of bajos (seasonal wetlands), increasing erosion and transforming them into unproductive swamps, which compounded drought vulnerability during the Terminal Classic period (ca. 800–900 CE). While direct causation of societal collapse remains debated—some lake core analyses show no peak deforestation correlating with abandonment—lidar surveys and soil studies confirm habitat loss amplified water scarcity and food insecurity.[33][34] On isolated Easter Island (Rapa Nui), Polynesian settlers felled palm-dominated forests for canoes, agriculture, and statues by around 1600 CE, leading to total tree extinction and severe soil erosion that halved arable land; however, archaeological re-evaluations indicate gradual adaptation rather than abrupt ecocide-induced collapse prior to European contact in 1722, with population stabilizing at 2,000–3,000 through diversified fishing and horticulture.[36][37][38] These patterns illustrate recurring causal dynamics: population-driven resource demands outpacing regeneration, yielding feedback loops of declining fertility and localized societal stress, though external factors like climate variability often co-determined outcomes.[39][40]Industrial Era Acceleration

The Industrial Revolution, commencing in Britain around 1760 and spreading across Europe and North America by the early 19th century, initiated a profound acceleration in environmental degradation through the mechanization of production, reliance on coal as a primary energy source, and rapid urbanization. This era shifted economies from agrarian systems to factory-based manufacturing, exponentially increasing resource extraction and waste generation. Fossil fuel combustion for steam engines and iron production released vast quantities of sulfur dioxide, particulate matter, and carbon dioxide, while land clearance for agriculture, timber, and infrastructure expanded to support growing industrial demands. Empirical records indicate that atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations began a sustained rise after 1750, exceeding pre-industrial levels by over 50 percent by the late 20th century, with initial acceleration tied to coal's dominance in energy supply.[41] Air pollution intensified markedly, as coal-fired factories and locomotives emitted black smoke laden with soot and acids, degrading urban atmospheres. In Britain, coal consumption surged from approximately 10 million tons annually in 1800 to over 100 million tons by 1850, correlating with elevated respiratory disease rates and premature mortality in industrial cities. London's air quality deteriorated progressively through the 19th century, with smog events foreshadowing the lethal 1952 episode that killed thousands, rooted in unchecked coal burning for heating and power. Water bodies suffered similarly, as untreated effluents from textile mills, tanneries, and metalworks—containing dyes, heavy metals, and organic waste—were discharged directly into rivers, rendering them oxygen-depleted and toxic. In 19th-century New England, for instance, waterways powering mills became dumping grounds, fostering bacterial proliferation and fish kills that disrupted local ecosystems.[42][43] Deforestation rates escalated to meet timber needs for shipbuilding, railroads, and charcoal production in early iron smelting, exacerbating soil erosion and habitat fragmentation. Britain's woodlands, already strained, were largely depleted by the mid-18th century, compelling a pivot to coal and imports, while continental Europe's forests faced intensified logging during the 19th century's infrastructural boom. Globally, forest clearance averaged 19 million hectares per decade from 1700 to 1850, with industrial expansion amplifying this through demand for construction materials and fuel. Nitrous oxide levels, linked to early fertilizer use and biomass burning, rose about 20 percent from pre-industrial baselines by the era's close, contributing to nascent atmospheric changes. These pressures, driven by causal chains of technological adoption and population concentration in industrial hubs, laid foundational patterns of degradation that persisted and scaled in subsequent decades.[44][45][46][7]Post-1950 Global Trends

Since 1950, global environmental degradation has intensified markedly, driven by population growth from approximately 2.5 billion to over 8 billion people, alongside rapid industrialization, urbanization, and expansion of agriculture and resource extraction. This period, often termed the "Great Acceleration," saw exponential rises in human impacts on ecosystems, with metrics across deforestation, biodiversity loss, soil erosion, and pollution reflecting net declines in environmental integrity despite localized improvements in wealthier nations through regulatory measures. Empirical data from satellite observations and long-term monitoring indicate that while some developed regions achieved partial reversals—such as reduced sulfur dioxide emissions—the overall global trajectory involved widespread habitat conversion and resource depletion, outpacing natural recovery rates.[47][48] Deforestation rates, which were minimal in the 1950s, accelerated sharply from the 1970s onward, particularly in tropical regions like the Amazon, where annual losses escalated due to logging, agriculture, and infrastructure development. Globally, net forest loss averaged 4.7 million hectares per year between 2010 and 2020, though gross deforestation exceeded this due to offsetting reforestation in temperate zones; tropical primary forest loss alone contributed to over half of global tree cover reduction since 2000, totaling around 517 million hectares from 2001 to 2024. Half of the world's historical forest loss—equivalent to one-third of original cover over 10,000 years—occurred in the 20th century, with post-1950 drivers including conversion to cropland and pastures, which now occupy 31% of habitable land.[46][49][50] Biodiversity metrics reveal severe declines, with monitored vertebrate populations averaging a 69-73% drop since 1970, attributed to habitat fragmentation, overexploitation, and pollution; for instance, insect populations fell by about 45% globally in the same timeframe, while around half of tracked species showed net losses despite gains in some managed areas. Soil degradation affected an estimated 500 million hectares in Africa alone since 1950, with global trends showing accelerated erosion and nutrient depletion from intensified farming, reducing arable land productivity and contributing to desertification in drylands covering 40% of Earth's surface. Water scarcity and pollution worsened with freshwater use rising steeply until plateauing post-2000, as untreated wastewater and agricultural runoff eutrophied waterways, though regulatory interventions in Europe and North America curbed some contaminants like phosphorus since the 1970s.[47][51][52] Air quality trends exhibited divergence: particulate matter (PM2.5) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentrations peaked in industrialized nations mid-century before declining due to clean air acts—e.g., SO2 emissions fell globally post-2000—but attributable deaths from outdoor pollution rose 89-124% from 1960 to 2009, driven by surges in Asia where rapid urbanization outstripped controls. Plastic pollution, negligible in 1950, exploded to over 450 million tonnes produced annually by the 2020s, with mismanaged waste entering oceans and soils at rates implying persistence for centuries. These trends underscore causal links to human activity scales, where empirical reversals remain confined to high-income contexts with strong institutions, while developing regions bore disproportionate burdens amid economic catch-up.[53][54][55]Primary Drivers

Population Growth

Population growth exerts pressure on environmental systems primarily through its role as a multiplicative factor in the IPAT equation, where environmental impact equals population multiplied by affluence and the inverse efficiency of technology. This framework, originating from analyses in the 1970s, posits that each additional person scales total resource consumption and waste generation, amplifying degradation even as per capita impacts may fluctuate due to technological advancements. Empirical studies confirm that population increases correlate with heightened environmental strain, including soil erosion, water overuse, and habitat fragmentation, particularly in regions with rapid demographic expansion.[56][57] The global population has surged from about 2.5 billion in 1950 to 8 billion by November 15, 2022, driven by declining mortality rates from medical progress and agricultural yields from the Green Revolution. This postwar acceleration, with annual growth peaking at over 2% in the 1960s, coincided with intensified land conversion for agriculture and urbanization, contributing to an estimated 20-30% of tropical deforestation attributable to expanding human settlement and farming needs. In developing countries, where most growth occurs, high fertility rates—averaging 4-5 children per woman in sub-Saharan Africa as of 2023—exacerbate local degradation, such as aquifer depletion and biodiversity hotspots encroachment, as populations double every 20-30 years in affected areas.[58][59][57] United Nations projections from the 2022 revision anticipate continued growth to 9.7 billion by 2050 and a peak of 10.4 billion around 2086, after which fertility declines below replacement levels in most regions could stabilize numbers. However, this trajectory implies sustained demand for resources; for instance, a 25% population rise from current levels could necessitate equivalent increases in food production, risking further soil nutrient depletion and pesticide runoff unless yields intensify dramatically. Peer-reviewed analyses highlight that without corresponding efficiency gains, such growth sustains upward pressure on carbon emissions and freshwater extraction, with population accounting for 30-50% of variance in cross-national environmental indicators like deforestation rates. In high-income nations, where populations are stable or declining, immigration sustains numbers and offsets aging demographics, indirectly perpetuating consumption-driven impacts.[60][61][62]Affluence and Consumption Patterns

Affluence, as conceptualized in the IPAT framework, refers to per capita economic activity—typically measured by GDP per capita—which correlates with heightened resource consumption and waste generation, thereby amplifying environmental pressures beyond mere population effects.[21] Empirical analyses of the IPAT model indicate that affluence drives disproportionate impacts through expanded demand for energy, materials, and land-intensive goods, with historical data showing that even stable population and affluence levels contribute to degradation absent technological offsets.[63] For instance, rising incomes facilitate shifts in consumption patterns toward high-impact items such as processed foods, private vehicles, and electronics, which entail extensive upstream resource extraction and downstream pollution.[25] Global statistics underscore this linkage: in 2017, the material footprint per capita in high-income countries reached 26.3 metric tons, over twice the world average of 12.2 metric tons and approximately 13 times that of low-income nations, reflecting intensified extraction of biomass, fossil fuels, metals, and minerals to sustain affluent lifestyles.[64] Similarly, per capita carbon emissions exhibit stark inequality, with the wealthiest 10% of the global population responsible for emissions 50 times higher than the poorest 10%, driven by luxury consumption including air travel and energy-intensive housing.[65] These patterns persist despite efficiency gains, as rebound effects—where cost savings from technology spur further consumption—often negate reductions in resource intensity.[66] While the Environmental Kuznets Curve posits that environmental degradation initially rises with affluence before declining at higher income levels due to regulatory and technological responses, empirical evidence is inconsistent across indicators and regions.[67] For local pollutants like sulfur dioxide in OECD countries, an inverted U-shape holds, with per capita emissions peaking around $8,000–$10,000 GDP and then falling as incomes exceed $20,000.[68] However, for global issues such as CO2 emissions and material use, decoupling remains largely relative rather than absolute, with offshored production masking domestic gains; only 49 countries achieved emissions decoupling from GDP growth by 2020, predominantly high-income ones, while most developing economies continue coupling.[69] [70] Thus, affluent consumption sustains cumulative global degradation, as wealth-driven demand outpaces localized mitigations.[71]Technology and Land-Use Changes

Technological advancements have historically amplified environmental degradation by enabling more intensive resource extraction and conversion of natural ecosystems into human-dominated landscapes, as conceptualized in the IPAT equation where technology (T) modulates impact per unit of population and affluence.[56] Industrial innovations during the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, such as steam engines and coal combustion, markedly increased air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions through fossil fuel dependency, with global CO2 emissions rising from negligible pre-industrial levels to over 2 billion metric tons annually by 1900.[72] Similarly, extractive technologies like hydraulic fracturing since the 2000s have expanded access to oil and gas reserves, boosting production but contributing to water contamination and methane leaks, with U.S. unconventional gas extraction alone adding 0.3-1.9% to global emissions in its early years. Land-use changes, often propelled by technological progress in agriculture and infrastructure, have transformed approximately 32% of the global terrestrial surface between 1960 and 2019, far exceeding prior estimates by a factor of four.[73] Agricultural mechanization and chemical inputs during the Green Revolution (circa 1960-1980) tripled cereal production in developing countries but induced widespread soil degradation, including erosion and salinization affecting 23% of irrigated lands in regions like India due to over-fertilization and monocropping.[74] Urbanization, facilitated by road networks and construction machinery, has seen global urban land expand at twice the rate of population growth since 1990, converting 1.2 million square kilometers of rural land by 2030 projections and exacerbating habitat fragmentation and impervious surface runoff that impairs watershed functions.[75][76] These dynamics illustrate a causal chain where technology decouples production from traditional limits, permitting affluence-driven expansion that outpaces ecological carrying capacity, though efficiency gains in some sectors have occasionally offset portions of the impact without halting net degradation.[77] For instance, fertilizer runoff from intensified farming has eutrophied water bodies worldwide, with dead zones in coastal areas expanding from 50 in 1970 to over 400 by 2008, directly tied to synthetic nitrogen application rising from 11 million tons in 1960 to 100 million tons by 2000.[78] Empirical assessments underscore that such land-use shifts, while boosting economic output, impose persistent costs like reduced soil organic matter and biodiversity loss, with cropland expansion alone accounting for 6% growth in affected areas from 1992 to 2020.[79]Key Manifestations

Deforestation and Habitat Loss

Deforestation refers to the permanent conversion of forested land to non-forest uses, such as agriculture or urban development, while habitat loss encompasses the broader degradation or fragmentation of ecosystems that support wildlife. Globally, approximately 10 million hectares of forest are lost annually through deforestation, according to United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates based on national reporting and remote sensing data.[46] This rate has declined from higher levels in previous decades, with net forest loss dropping from 7.8 million hectares per year in the 1990s to around 4.7 million hectares in the 2010s, though gross loss remains substantial due to ongoing clearing offset partially by afforestation efforts. Habitat loss, often a direct consequence of deforestation, is the primary driver of biodiversity decline, affecting 85% of threatened species as identified by the World Wildlife Fund through assessments of habitat conversion pressures.[80] The principal causes of deforestation are agricultural expansion and commercial logging, accounting for over 90% of permanent forest loss in empirical analyses spanning 1840 to recent decades. Commodity-driven agriculture, including cattle ranching, soybean cultivation, and palm oil production, dominates, with studies attributing 96% of historical deforestation to shifting land for food and fiber production.[81] Urbanization, mining, and infrastructure contribute smaller shares, typically under 10%, while wildfires and selective logging cause temporary canopy loss that may not qualify as full deforestation under FAO definitions but exacerbates habitat fragmentation.[82] Habitat loss extends beyond forests to grasslands and wetlands, driven similarly by land conversion for intensive farming, which utilizes 40% of habitable land and correlates with population density increases in econometric models.[83] Tropical regions bear the brunt of deforestation, with Latin America accounting for 59% and Southeast Asia 28% of global losses between 2001 and recent years, per satellite monitoring. In 2024, tropical primary rainforest loss reached a record 6.7 million hectares, largely from fires but with persistent commodity pressures in Brazil and Indonesia.[84] Brazil reported 1.7 million hectares of annual deforestation in the 2015-2020 period, primarily for soy and beef, while Indonesia's losses link to palm oil estates.[85] Habitat loss metrics show parallel trends, with 75% of terrestrial environments altered, leading to average 69% declines in monitored vertebrate populations since 1970, as quantified in the WWF Living Planet Index using time-series population data.[86] These patterns reflect causal links to expanding agricultural frontiers, where empirical evidence prioritizes direct land-use change over indirect factors like policy or climate variability alone.[81]Soil Erosion and Desertification

Soil erosion involves the detachment, transport, and deposition of soil particles, primarily by water and wind, leading to the loss of fertile topsoil essential for agriculture and ecosystems. Natural rates of erosion occur over geological timescales, but anthropogenic acceleration—through practices like tillage, monocropping, and removal of vegetative cover—has intensified the process, with global estimates indicating an annual soil loss of approximately 35.9 petagrams (35.9 billion metric tons) as of 2012, a figure revised downward from prior higher assessments based on improved modeling of rainfall erosivity and land cover.[87] This erosion diminishes soil structure, organic matter, and nutrient content, rendering land less productive and increasing sedimentation in waterways.[88] Desertification, distinct yet often linked to erosion, denotes the long-term deterioration of land in arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid regions, transforming once-productive areas into desert-like conditions through reduced biological and economic productivity. Defined by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) as primarily human-induced, it arises from factors such as overgrazing, which compacts soil and exposes it to erosive forces; improper irrigation leading to salinization; and deforestation that eliminates root systems stabilizing soil.[89] Unlike transient drought, desertification reflects persistent degradation, with vegetation loss exacerbating wind erosion and feedback loops of bare soil heating and further inhibiting regrowth.[90] Human activities drive the majority of both phenomena, with agricultural mismanagement— including excessive plowing and livestock densities beyond carrying capacity—accounting for much of the acceleration, rather than climate variability alone. Peer-reviewed analyses emphasize that poor land-use practices, such as converting natural vegetation to cropland without conservation measures, directly cause structural instability and particle detachment.[91] In drylands, overexploitation for subsistence farming amplifies these effects, as seen in models integrating socioeconomic drivers like population pressure on marginal lands.[92] Globally, land degradation linked to erosion and desertification affects about 1.66 billion hectares, exceeding 10% of the Earth's land surface, with over 60% impacting agricultural areas according to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) assessments.[93] The UNCCD reports that up to 40% of the world's land is degraded, home to 3.2 billion people, with annual soil losses contributing to broader productivity declines.[94] Regional hotspots include the Sahel in Africa, where overgrazing has expanded degraded zones by millions of hectares since the mid-20th century, and parts of Central Asia, underscoring the causal primacy of unsustainable practices over climatic shifts in empirical trend data.[95]Water Scarcity and Pollution

Water scarcity arises when demand exceeds available supply, often exacerbated by overextraction for agriculture, industry, and urban use, leading to depleted aquifers and reduced river flows. Globally, nearly two-thirds of the population experiences acute water scarcity for at least one month annually, with roughly half facing severe scarcity for part of the year. As of 2025, one in four people—approximately 2 billion—lack access to safely managed drinking water services. Physical scarcity predominates in arid regions, while economic scarcity stems from inadequate infrastructure, but human activities like irrigation, which consumes 70% of freshwater withdrawals, accelerate depletion in both cases.[96][97][98] Aquifer depletion exemplifies scarcity's progression, with groundwater levels declining in 71% of monitored systems worldwide, accelerating in many due to pumping rates outpacing recharge. In 36% of aquifer systems, declines exceed 0.1 meters per year, and in drier cropland regions like California's Central Valley, losses surpass 0.5 meters annually in some areas. Major aquifers, such as the U.S. High Plains and Ogallala, have seen water levels drop over 100 feet since pre-development, reducing saturated thickness by more than half in parts. Such depletion, driven by agricultural demand, threatens long-term availability, as 21 of 37 major global aquifers deplete faster than replenishment.[99][100][101] Water pollution compounds scarcity by rendering supplies unusable, with untreated wastewater—80% of global industrial and domestic discharge—contaminating rivers, lakes, and groundwater. Approximately 2 million tons of waste enter waterways daily, including pathogens, nutrients, and heavy metals, with pathogen pollution most severe in Asia. Half of the world's countries report degraded freshwater ecosystems, influenced by land-use changes and climate shifts, affecting river flows in 402 basins—a fivefold rise since 2000. Plastic leakage adds 19-23 million tonnes annually to aquatic systems, primarily via rivers, where 1,000 key waterways account for 80% of emissions.[102][103][104][105] Agricultural runoff, carrying fertilizers and pesticides, eutrophies water bodies, while industrial effluents introduce toxins; for instance, only one in ten liters of treated wastewater is reused globally, with half still polluting surface waters. Pollution aggravates scarcity in over 2,000 sub-basins, tripling affected areas when combined with overuse projections. In regions like South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, untreated sewage and mining discharges have rendered rivers ecologically dead, reducing biodiversity and potable volumes. Empirical assessments link these degradations to health risks for 3 billion people in data-scarce areas, underscoring gaps in monitoring that mask full extent.[106][107][108][109]Air Quality Degradation