Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Liquid

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

Liquid is a state of matter with a definite volume but no fixed shape. When resting in a container, liquids typically adapt to the shape of the container.[note 1] Liquids are nearly incompressible, maintaining their volume even under pressure. The density of a liquid is usually close to that of a solid, and much higher than that of a gas. Liquids are a form of condensed matter alongside solids, and a form of fluid alongside gases.

A liquid is composed of atoms or molecules held together by intermolecular bonds of intermediate strength. These forces allow the particles to move around one another while remaining closely packed. In contrast, solids have particles that are tightly bound by strong intermolecular forces, limiting their movement to small vibrations in fixed positions. Gases, on the other hand, consist of widely spaced, freely moving particles with only weak intermolecular forces.

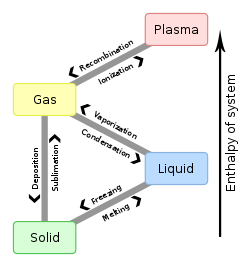

As temperature increases, the molecules in a liquid vibrate more intensely, causing the distances between them to increase. At the boiling point, the cohesive forces between the molecules are no longer sufficient to keep them together, and the liquid transitions into a gaseous state. Conversely, as temperature decreases, the distance between molecules shrinks. At the freezing point, the molecules typically arrange into a structured order in a process called crystallization, and the liquid transitions into a solid state.

Although liquid water is abundant on Earth, this state of matter is actually the least common in the known universe, because liquids require a relatively narrow temperature/pressure range to exist. Most known matter in the universe is either gaseous (as interstellar clouds) or plasma (as stars).

Examples

[edit]Only two elements are liquid at standard conditions for temperature and pressure: mercury and bromine. Four more elements have melting points slightly above room temperature: francium, caesium, gallium and rubidium.[1]

Pure substances that are liquid under normal conditions include water, ethanol and many other organic solvents. Liquid water is of vital importance in chemistry and biology, and it is necessary for all known forms of life.[2][3] Inorganic liquids in this category include inorganic nonaqueous solvents and many acids.

Mixtures that are liquid at room temperature include alloys such as galinstan (a gallium-indium-tin alloy that melts at −19 °C or −2 °F) and some amalgams (alloys involving mercury).[4] Certain mixtures, such as the sodium-potassium metal alloy NaK, are liquid at room temperature even though the individual elements are solid under the same conditions (see eutectic mixture).[5] Everyday liquid mixtures include aqueous solutions like household bleach, other mixtures of different substances such as mineral oil and gasoline, emulsions like vinaigrette or mayonnaise, suspensions like blood, and colloids like paint and milk.

Many gases can be liquefied by cooling, producing liquids such as liquid oxygen, liquid nitrogen, liquid hydrogen and liquid helium. However, not all gases can be liquefied at atmospheric pressure. Carbon dioxide, for example, solidifies directly into dry ice rather than becoming a liquid, and it can only be liquified at pressures above 5.1 atm.[6] Most liquids solidify as the temperature is decreased further. Liquid helium is exceptional in that it does not become solid even at absolute zero (0 K) under standard pressure due to its quantum properties.[7]

Properties

[edit]Volume

[edit]

Quantities of liquids are measured in units of volume. These include the SI unit cubic metre (m3) and its divisions, in particular the cubic decimeter, more commonly called the litre (1 dm3 = 1 L = 0.001 m3), and the cubic centimetre, also called millilitre (1 cm3 = 1 mL = 0.001 L = 10−6 m3).[8]

The volume of a quantity of liquid is fixed by its temperature and pressure. Liquids generally expand when heated, and contract when cooled. Water between 0 °C and 4 °C is a notable exception.[9]

On the other hand, liquids have little compressibility. Water, for example, will compress by only 46.4 parts per million for every unit increase in atmospheric pressure (bar).[10] At around 4000 bar (400 megapascals or 58,000 psi) of pressure at room temperature water experiences only an 11% decrease in volume.[11] Incompressibility makes liquids suitable for transmitting hydraulic power, because a change in pressure at one point in a liquid is transmitted undiminished to every other part of the liquid and very little energy is lost in the form of compression.[12]

However, the negligible compressibility does lead to other phenomena. The banging of pipes, called water hammer, occurs when a valve is suddenly closed, creating a huge pressure-spike at the valve that travels backward through the system at just under the speed of sound. Another phenomenon caused by liquid's incompressibility is cavitation. Because liquids have little elasticity they can literally be pulled apart in areas of high turbulence or dramatic change in direction, such as the trailing edge of a boat propeller or a sharp corner in a pipe. A liquid in an area of low pressure (vacuum) vaporizes and forms bubbles, which then collapse as they enter high pressure areas. This causes liquid to fill the cavities left by the bubbles with tremendous localized force, eroding any adjacent solid surface.[13]

Pressure and buoyancy

[edit]In a gravitational field, liquids exert pressure on the sides of a container as well as on anything within the liquid itself. This pressure is transmitted in all directions and increases with depth. If a liquid is at rest in a uniform gravitational field, the pressure at depth is given by[14]

where:

- is the pressure at the surface

- is the density of the liquid, assumed uniform with depth

- is the gravitational acceleration

For a body of water open to the air, would be the atmospheric pressure.

Static liquids in uniform gravitational fields also exhibit the phenomenon of buoyancy, where objects immersed in the liquid experience a net force due to the pressure variation with depth. The magnitude of the force is equal to the weight of the liquid displaced by the object, and the direction of the force depends on the average density of the immersed object. If the density is smaller than that of the liquid, the buoyant force points upward and the object floats, whereas if the density is larger, the buoyant force points downward and the object sinks. This is known as Archimedes' principle.[15]

Surfaces

[edit]

Unless the volume of a liquid exactly matches the volume of its container, one or more surfaces are observed. The presence of a surface introduces new phenomena which are not present in a bulk liquid. This is because a molecule at a surface possesses bonds with other liquid molecules only on the inner side of the surface, which implies a net force pulling surface molecules inward. Equivalently, this force can be described in terms of energy: there is a fixed amount of energy associated with forming a surface of a given area. This quantity is a material property called the surface tension, in units of energy per unit area (SI units: J/m2). Liquids with strong intermolecular forces tend to have large surface tensions.[16]

A practical implication of surface tension is that liquids tend to minimize their surface area, forming spherical drops and bubbles unless other constraints are present. Surface tension is responsible for a range of other phenomena as well, including surface waves, capillary action, wetting, and ripples. In liquids under nanoscale confinement, surface effects can play a dominating role since – compared with a macroscopic sample of liquid – a much greater fraction of molecules are located near a surface.

The surface tension of a liquid directly affects its wettability. Most common liquids have tensions ranging in the tens of mJ/m2, so droplets of oil, water, or glue can easily merge and adhere to other surfaces, whereas liquid metals such as mercury may have tensions ranging in the hundreds of mJ/m2, thus droplets do not combine easily and surfaces may only wet under specific conditions.

The surface tensions of common liquids occupy a relatively narrow range of values when exposed to changing conditions such as temperature, which contrasts strongly with the enormous variation seen in other mechanical properties, such as viscosity.[17]

Flow

[edit]

An important physical property characterizing the flow of liquids is viscosity. Intuitively, viscosity describes the resistance of a liquid to flow. More technically, viscosity measures the resistance of a liquid to deformation at a given rate, such as when it is being sheared at finite velocity.[18] A specific example is a liquid flowing through a pipe: in this case the liquid undergoes shear deformation since it flows more slowly near the walls of the pipe than near the center. As a result, it exhibits viscous resistance to flow. In order to maintain flow, an external force must be applied, such as a pressure difference between the ends of the pipe.

The viscosity of liquids decreases with increasing temperature.[19]

Precise control of viscosity is important in many applications, particularly the lubrication industry. One way to achieve such control is by blending two or more liquids of differing viscosities in precise ratios.[20] In addition, various additives exist which can modulate the temperature-dependence of the viscosity of lubricating oils. This capability is important since machinery often operate over a range of temperatures (see also viscosity index).[21]

The viscous behavior of a liquid can be either Newtonian or non-Newtonian. A Newtonian liquid exhibits a linear strain/stress curve, meaning its viscosity is independent of time, shear rate, or shear-rate history. Examples of Newtonian liquids include water, glycerin, motor oil, honey, or mercury. A non-Newtonian liquid is one where the viscosity is not independent of these factors and either thickens (increases in viscosity) or thins (decreases in viscosity) under shear. Examples of non-Newtonian liquids include ketchup, custard, or starch solutions.[22]

Sound propagation

[edit]The speed of sound in a liquid is given by where is the bulk modulus of the liquid and the density. As an example, water has a bulk modulus of about 2.2 GPa and a density of 1000 kg/m3, which gives c = 1.5 km/s.[23]

Microscopic structure

[edit]The microscopic structure of liquids is complex and historically has been the subject of intense research and debate.[24][25][26][27] Liquids consist of a dense, disordered packing of molecules. This contrasts with the other two common phases of matter, gases and solids. Although gases are disordered, the molecules are well-separated in space and interact primarily through molecule-molecule collisions. Conversely, although the molecules in solids are densely packed, they usually fall into a regular structure, such as a crystalline lattice (glasses are a notable exception).

Short-range ordering

[edit]

While liquids do not exhibit long-range ordering as in a crystalline lattice, they do possess short-range order, which persists over a few molecular diameters.[28][29]

In all liquids, excluded volume interactions induce short-range order in molecular positions (center-of-mass coordinates). Classical monatomic liquids like argon and krypton are the simplest examples. Such liquids can be modeled as disordered "heaps" of closely packed spheres, and the short-range order corresponds to the fact that nearest and next-nearest neighbors in a packing of spheres tend to be separated by integer multiples of the diameter.[30][31]

In most liquids, molecules are not spheres, and intermolecular forces possess a directionality, i.e., they depend on the relative orientation of molecules. As a result, there is short-ranged orientational order in addition to the positional order mentioned above. Orientational order is especially important in hydrogen-bonded liquids like water.[32][33] The strength and directional nature of hydrogen bonds drives the formation of local "networks" or "clusters" of molecules. Due to the relative importance of thermal fluctuations in liquids (compared with solids), these structures are highly dynamic, continuously deforming, breaking, and reforming.[30][32]

While ordinary liquids lack long-range order, some materials exhibit intermediate behavior. Liquid crystals, for example, flow like liquids but exhibit long-range orientational alignment of their molecules. Unlike solids, they lack long-range translational order, yet their anisotropic properties set them apart from conventional liquids. As a result, liquid crystals are considered a distinct state of matter. They are utilized in technologies such as liquid-crystal displays (LCDs).[34]

Energy and entropy

[edit]The microscopic features of liquids derive from an interplay between attractive intermolecular forces and entropic forces.[35]

The attractive forces tend to pull molecules close together, and along with short-range repulsive interactions, they are the dominant forces behind the regular structure of solids. The entropic forces are not "forces" in the mechanical sense; rather, they describe the tendency of a system to maximize its entropy at fixed energy (see microcanonical ensemble). Roughly speaking, entropic forces drive molecules apart from each other, maximizing the volume they occupy. Entropic forces dominant in gases and explain the tendency of gases to fill their containers. In liquids, by contrast, the intermolecular and entropic forces are comparable, so it is not possible to neglect one in favor of the other. Quantitatively, the binding energy between adjacent molecules is the same order of magnitude as the thermal energy .[36]

No small parameter

[edit]The competition between energy and entropy makes liquids difficult to model at the molecular level, as there is no idealized "reference state" that can serve as a starting point for tractable theoretical descriptions. Mathematically, there is no small parameter from which one can develop a systematic perturbation theory.[25] This situation contrasts with both gases and solids. For gases, the reference state is the ideal gas, and the density can be used as a small parameter to construct a theory of real (nonideal) gases (see virial expansion).[37] For crystalline solids, the reference state is a perfect crystalline lattice, and possible small parameters are thermal motions and lattice defects.[32]

Role of quantum mechanics

[edit]Like all known forms of matter, liquids are fundamentally quantum mechanical. However, under standard conditions (near room temperature and pressure), much of the macroscopic behavior of liquids can be understood in terms of classical mechanics.[36][38] The "classical picture" posits that the constituent molecules are discrete entities that interact through intermolecular forces according to Newton's laws of motion. As a result, their macroscopic properties can be described using classical statistical mechanics. While the intermolecular force law technically derives from quantum mechanics, it is usually understood as a model input to classical theory, obtained either from a fit to experimental data or from the classical limit of a quantum mechanical description.[39][28] An illustrative, though highly simplified example is a collection of spherical molecules interacting through a Lennard-Jones potential.[36]

| Liquid | Temperature (K) | (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H2) | 14.1 | 0.33 | 0.97 |

| Neon | 24.5 | 0.078 | 0.26 |

| Krypton | 116 | 0.018 | 0.046 |

| Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) | 250 | 0.009 | 0.017 |

For the classical limit to apply, a necessary condition is that the thermal de Broglie wavelength,

is small compared with the length scale under consideration.[36][40] Here, is the Planck constant and is the molecule's mass. Typical values of are about 0.01-0.1 nanometers (Table 1). Hence, a high-resolution model of liquid structure at the nanoscale may require quantum mechanical considerations. A notable example is hydrogen bonding in associated liquids like water,[41][42] where, due to the small mass of the proton, inherently quantum effects such as zero-point motion and tunneling are important.[43]

For a liquid to behave classically at the macroscopic level, must be small compared with the average distance between molecules.[36] That is,

Representative values of this ratio for a few liquids are given in Table 1. The conclusion is that quantum effects are important for liquids at low temperatures and with small molecular mass.[36][38] For dynamic processes, there is an additional timescale constraint:

where is the timescale of the process under consideration. For room-temperature liquids, the right-hand side is about 10−14 seconds, which generally means that time-dependent processes involving translational motion can be described classically.[36]

At extremely low temperatures, even the macroscopic behavior of certain liquids deviates from classical mechanics. Notable examples are hydrogen and helium. Due to their low temperature and mass, such liquids have a thermal de Broglie wavelength comparable to the average distance between molecules.[36]

Dynamic phenomena

[edit]The expression for the sound velocity of a liquid,

- ,

contains the bulk modulus K. If K is frequency-independent, then the liquid behaves as a linear medium, so that sound propagates without dissipation or mode coupling. In reality, all liquids show some dispersion: with increasing frequency, K crosses over from the low-frequency, liquid-like limit to the high-frequency, solid-like limit . In normal liquids, most of this crossover takes place at frequencies between GHz and THz, sometimes called hypersound.

At sub-GHz frequencies, a normal liquid cannot sustain shear waves: the zero-frequency limit of the shear modulus is 0. This is sometimes seen as the defining property of a liquid.[44][45] However, like the bulk modulus K, the shear modulus G is also frequency-dependent and exhibits a similar crossover at hypersound frequencies.

According to linear response theory, the Fourier transform of K or G describes how the system returns to equilibrium after an external perturbation; for this reason, the dispersion step in the GHz to THz region is also called relaxation. As a liquid is supercooled toward the glass transition, the structural relaxation time exponentially increases, which explains the viscoelastic behavior of glass-forming liquids.

Experimental methods

[edit]The absence of long-range order in liquids is mirrored by the absence of Bragg peaks in X-ray and neutron diffraction. Under normal conditions, the diffraction pattern has circular symmetry, expressing the isotropy of the liquid. Radially, the diffraction intensity smoothly oscillates. This can be described by the static structure factor , with wavenumber given by the wavelength of the probe (photon or neutron) and the Bragg angle . The oscillations of express the short-range order of the liquid, i.e., the correlations between a molecule and "shells" of nearest neighbors, next-nearest neighbors, and so on.

An equivalent representation of these correlations is the radial distribution function , which is related to the Fourier transform of .[30] It represents a spatial average of a temporal snapshot of pair correlations in the liquid.

Phase transitions

[edit]

At a temperature below the boiling point, any matter in liquid form will evaporate until reaching equilibrium with the reverse process of condensation of its vapor. At this point the vapor will condense at the same rate as the liquid evaporates. Thus, a liquid cannot exist permanently if the evaporated liquid is continually removed.[46] A liquid at or above its boiling point will normally boil, though superheating can prevent this in certain circumstances.

At a temperature below the freezing point, a liquid will tend to crystallize, changing to its solid form. Unlike the transition to gas, there is no equilibrium at this transition under constant pressure,[citation needed] so unless supercooling occurs, the liquid will eventually completely crystallize. However, this is only true under constant pressure, so that (for example) water and ice in a closed, strong container might reach an equilibrium where both phases coexist. For the opposite transition from solid to liquid, see melting.

The phase diagram explains why liquids do not exist in space or any other vacuum. Since the pressure is essentially zero (except on surfaces or interiors of planets and moons) water and other liquids exposed to space will either immediately boil or freeze depending on the temperature. In regions of space near the Earth, water will freeze if the sun is not shining directly on it and vaporize (sublime) as soon as it is in sunlight. If water exists as ice on the Moon, it can only exist in shadowed holes where the sun never shines and where the surrounding rock does not heat it up too much. At some point near the orbit of Saturn, the light from the Sun is too faint to sublime ice to water vapor. This is evident from the longevity of the ice that composes Saturn's rings.[47]

Solutions

[edit]Liquids can form solutions with gases, solids, and other liquids.

Two liquids are said to be miscible if they can form a solution in any proportion; otherwise they are immiscible. As an example, water and ethanol (drinking alcohol) are miscible whereas water and gasoline are immiscible.[48] In some cases a mixture of otherwise immiscible liquids can be stabilized to form an emulsion, where one liquid is dispersed throughout the other as microscopic droplets. Usually this requires the presence of a surfactant in order to stabilize the droplets. A familiar example of an emulsion is mayonnaise, which consists of a mixture of water and oil that is stabilized by lecithin, a substance found in egg yolks.[49]

Applications

[edit]

Lubrication

[edit]Liquids are useful as lubricants due to their ability to form a thin, freely flowing layer between solid materials. Lubricants such as oil are chosen for viscosity and flow characteristics that are suitable throughout the operating temperature range of the component. Oils are often used in engines, gear boxes, metalworking, and hydraulic systems for their good lubrication properties.[50]

Solvation

[edit]Many liquids are used as solvents, to dissolve other liquids or solids. Solutions are found in a wide variety of applications, including paints, sealants, and adhesives. Naphtha and acetone are used frequently in industry to clean oil, grease, and tar from parts and machinery. Body fluids are water-based solutions.

Surfactants are commonly found in soaps and detergents. Solvents like alcohol are often used as antimicrobials. They are found in cosmetics, inks, and liquid dye lasers. They are used in the food industry, in processes such as the extraction of vegetable oil.[51]

Cooling

[edit]Liquids tend to have better thermal conductivity than gases, and the ability to flow makes a liquid suitable for removing excess heat from mechanical components. The heat can be removed by channeling the liquid through a heat exchanger, such as a radiator, or the heat can be removed with the liquid during evaporation.[52] Water or glycol coolants are used to keep engines from overheating.[53] The coolants used in nuclear reactors include water or liquid metals, such as sodium or bismuth.[54] Liquid propellant films are used to cool the thrust chambers of rockets.[55] In machining, water and oils are used to remove the excess heat generated, which can quickly ruin both the work piece and the tooling. During perspiration, sweat removes heat from the human body by evaporating. In the heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning industry (HVAC), liquids such as water are used to transfer heat from one area to another.[56]

Cooking

[edit]Liquids are often used in cooking due to their excellent heat-transfer capabilities. In addition to thermal conduction, liquids transmit energy by convection. In particular, because warmer fluids expand and rise while cooler areas contract and sink, liquids with low kinematic viscosity tend to transfer heat through convection at a fairly constant temperature, making a liquid suitable for blanching, boiling, or frying. Even higher rates of heat transfer can be achieved by condensing a gas into a liquid. At the liquid's boiling point, all of the heat energy is used to cause the phase change from a liquid to a gas, without an accompanying increase in temperature, and is stored as chemical potential energy. When the gas condenses back into a liquid this excess heat-energy is released at a constant temperature. This phenomenon is used in processes such as steaming.

Distillation

[edit]Since liquids often have different boiling points, mixtures or solutions of liquids or gases can typically be separated by distillation, using heat, cold, vacuum, pressure, or other means. Distillation can be found in everything from the production of alcoholic beverages, to oil refineries, to the cryogenic distillation of gases such as argon, oxygen, nitrogen, neon, or xenon by liquefaction (cooling them below their individual boiling points).[57]

Hydraulics

[edit]Liquid is the primary component of hydraulic systems, which take advantage of Pascal's law to provide fluid power. Devices such as pumps and waterwheels have been used to change liquid motion into mechanical work since ancient times. Oils are forced through hydraulic pumps, which transmit this force to hydraulic cylinders. Hydraulics can be found in many applications, such as automotive brakes and transmissions, heavy equipment, and airplane control systems. Various hydraulic presses are used extensively in repair and manufacturing, for lifting, pressing, clamping and forming.[58]

Liquid metals

[edit]Liquid metals have several properties that are useful in sensing and actuation, particularly their electrical conductivity and ability to transmit forces (incompressibility). As freely flowing substances, liquid metals retain these bulk properties even under extreme deformation. For this reason, they have been proposed for use in soft robots and wearable healthcare devices, which must be able to operate under repeated deformation.[59][60] The metal gallium is considered to be a promising candidate for these applications as it is a liquid near room temperature, has low toxicity, and evaporates slowly.[61]

Miscellaneous

[edit]Liquids are sometimes used in measuring devices. A thermometer often uses the thermal expansion of liquids, such as mercury, combined with their ability to flow to indicate temperature. A manometer uses the weight of the liquid to indicate air pressure.[62]

The free surface of a rotating liquid forms a circular paraboloid and can therefore be used as a telescope. These are known as liquid-mirror telescopes.[63] They are significantly cheaper than conventional telescopes,[64] but can only point straight upward (zenith telescope). A common choice for the liquid is mercury.[citation needed]

Prediction of liquid properties

[edit]Methods for predicting liquid properties can be organized by their "scale" of description, that is, the length scales and time scales over which they apply.[65][66]

- Macroscopic methods use equations that directly model the large-scale behavior of liquids, such as their thermodynamic properties and flow behavior.

- Microscopic methods use equations that model the dynamics of individual molecules.

- Mesoscopic methods fall in between, combining elements of both continuum and particle-based models.

Macroscopic

[edit]Empirical correlations

[edit]Empirical correlations are simple mathematical expressions intended to approximate a liquid's properties over a range of experimental conditions, such as varying temperature and pressure.[67] They are constructed by fitting simple functional forms to experimental data. For example, the temperature-dependence of liquid viscosity is sometimes approximated by the function , where and are fitting constants.[68] Empirical correlations allow for extremely efficient estimates of physical properties, which can be useful in thermophysical simulations. However, they require high quality experimental data to obtain a good fit and cannot reliably extrapolate beyond the conditions covered by experiments.

Thermodynamic potentials

[edit]Thermodynamic potentials are functions that characterize the equilibrium state of a substance. An example is the Gibbs free energy , which is a function of pressure and temperature. Knowing any one thermodynamic potential is sufficient to compute all equilibrium properties of a substance, often simply by taking derivatives of .[37] Thus, a single correlation for can replace separate correlations for individual properties.[69][70] Conversely, a variety of experimental measurements (e.g., density, heat capacity, vapor pressure) can be incorporated into the same fit; in principle, this would allow one to predict hard-to-measure properties like heat capacity in terms of other, more readily available measurements (e.g., vapor pressure).[71]

Hydrodynamics

[edit]Hydrodynamic theories describe liquids in terms of space- and time-dependent macroscopic fields, such as density, velocity, and temperature. These fields obey partial differential equations, which can be linear or nonlinear.[72] Hydrodynamic theories are more general than equilibrium thermodynamic descriptions, which assume that liquids are approximately homogeneous and time-independent. The Navier-Stokes equations are a well-known example: they are partial differential equations giving the time evolution of density, velocity, and temperature of a viscous fluid. There are numerous methods for numerically solving the Navier-Stokes equations and its variants.[73][74]

Mesoscopic

[edit]Mesoscopic methods operate on length and time scales between the particle and continuum levels. For this reason, they combine elements of particle-based dynamics and continuum hydrodynamics.[65]

An example is the lattice Boltzmann method, which models a fluid as a collection of fictitious particles that exist on a lattice.[65] The particles evolve in time through streaming (straight-line motion) and collisions. Conceptually, it is based on the Boltzmann equation for dilute gases, where the dynamics of a molecule consists of free motion interrupted by discrete binary collisions, but it is also applied to liquids. Despite the analogy with individual molecular trajectories, it is a coarse-grained description that typically operates on length and time scales larger than those of true molecular dynamics (hence the notion of "fictitious" particles).

Other methods that combine elements of continuum and particle-level dynamics include smoothed-particle hydrodynamics,[75][76] dissipative particle dynamics,[77] and multiparticle collision dynamics.[78]

Microscopic

[edit]Microscopic simulation methods work directly with the equations of motion (classical or quantum) of the constituent molecules.

Classical molecular dynamics

[edit]Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulates liquids using Newton's law of motion; from Newton's second law (), the trajectories of molecules can be traced out explicitly and used to compute macroscopic liquid properties like density or viscosity. However, classical MD requires expressions for the intermolecular forces ("F" in Newton's second law). Usually, these must be approximated using experimental data or some other input.[28]

Ab initio (quantum) molecular dynamics

[edit]Ab initio quantum mechanical methods simulate liquids using only the laws of quantum mechanics and fundamental atomic constants.[39] In contrast with classical molecular dynamics, the intermolecular force fields are an output of the calculation, rather than an input based on experimental measurements or other considerations. In principle, ab initio methods can simulate the properties of a given liquid without any prior experimental data. However, they are very expensive computationally, especially for large molecules with internal structure.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ There is no fundamental principle requiring a liquid to conform to the shape of some container. If-and-when it does conform, it's because of fundamental principles such as balance of forces and the tendency of a fluid to yield to shear stress. The liquid remains a liquid even if it has no container at all, such as: droplets of water suspended in a cloud, a puddle of water on a flat tabletop, a stream of water from a fountain or pitcher, the oceans of a large watery planet, and so on. See also ullage motor.

References

[edit]- ^ Gray, Theodore; Mann, Nick (2012). The elements: a visual exploration of every known atom in the universe (1st paperback ed.). New York: Black Dog & Leventhal. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-57912-814-2.

- ^ Mottl, Michael J.; Glazer, Brian T.; Kaiser, Ralf I.; Meech, Karen J. (December 2007). "Water and astrobiology" (PDF). Geochemistry. 67 (4): 253–282. Bibcode:2007ChEG...67..253M. doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2007.09.002. ISSN 0009-2819.

- ^ Chyba, Christopher F.; Hand, Kevin P. (1 September 2005). "Astrobiology: The Study of the Living Universe". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 43 (1): 31–74. Bibcode:2005ARA&A..43...31C. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.43.051804.102202. eISSN 1545-4282. ISSN 0066-4146.

- ^ Surmann, Peter; Zeyat, Hanan (2005-10-15). "Voltammetric analysis using a self-renewable non-mercury electrode". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 383 (6). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1009–1013. doi:10.1007/s00216-005-0069-7. ISSN 1618-2642. PMID 16228199. S2CID 22732411.

- ^ Leonchuk, Sergei S.; Falchevskaya, Aleksandra S.; Nikolaev, Vitaly; Vinogradov, Vladimir V. (2022). "NaK alloy: underrated liquid metal". Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 10 (43). Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC): 22955–22976. doi:10.1039/d2ta06882f. ISSN 2050-7488. S2CID 252979251.

- ^ Silberberg 2009, pp. 448–449.

- ^ Wilks, J. (1967). The Properties of Liquid and Solid Helium. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-851245-7.

- ^ Knight, Randall D. (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: A Strategic Approach (With Modern Physics). Addison-Wesley. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-8053-2736-6.

- ^ Silberberg, Martin S. (2009). Chemistry: The Molecular Nature of Matter and Change. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-07-304859-8.

- ^ "Compressibility of Liquids". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Zhang, Wenwu (2011). Intelligent Energy Field Manufacturing: Interdisciplinary Process Innovations. CRC Press. p. 144.

- ^ Knight 2008, p. 454.

- ^ Gupta, S. C. (2006). Fluid Mechanics and Hydraulic Machines. Dorling-Kindersley. p. 85.

- ^ Knight 2008, p. 448.

- ^ Knight 2008, pp. 455–459.

- ^ Silberberg 2009, p. 457.

- ^ Edward Yu. Bormashenko (5 November 2018). Wetting of Real Surfaces. De Gruyter. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-3-11-058314-4.

- ^ Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. (1987). Fluid Mechanics (2nd ed.). Pergamon Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-08-033933-7.

- ^ Bird, R. Byron; Stewart, Warren E.; Lightfoot, Edwin N. (2007). Transport Phenomena (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-470-11539-8.

- ^ Zhmud, Boris (2014), "Viscosity Blending Equations" (PDF), Lube-Tech, 93

- ^ "Viscosity Index". UK: Anton Paar. Archived from the original on March 9, 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ Boukraa, Laid (2014). Honey in Traditional and Modern Medicine. CRC Press. pp. 22–24.

- ^ Taylor, John R. (2005). Classical Mechanics. University Science Books. pp. 727–729. ISBN 978-1-891389-22-1.

- ^ Chandler, David (2017-05-05). "From 50 Years Ago, the Birth of Modern Liquid-State Science". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 68 (1). Annual Reviews: 19–38. arXiv:1609.04837. Bibcode:2017ARPC...68...19C. doi:10.1146/annurev-physchem-052516-044941. ISSN 0066-426X. PMID 28375691. S2CID 37248336.

- ^ a b Trachenko, K; Brazhkin, V V (2015-12-22). "Collective modes and thermodynamics of the liquid state". Reports on Progress in Physics. 79 (1) 016502. IOP Publishing. arXiv:1512.06592. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/79/1/016502. ISSN 0034-4885. PMID 26696098. S2CID 42203015.

- ^ Ben-Naim, Arieh (2009). Molecular theory of water and aqueous solutions. Part 1, Understanding water. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-283-761-5. OCLC 696342117.

- ^ Pothoczki, Szilvia; Temleitner, László; Pusztai, László (2015-12-01). "Structure of Neat Liquids Consisting of (Perfect and Nearly) Tetrahedral Molecules". Chemical Reviews. 115 (24). American Chemical Society (ACS): 13308–13361. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00308. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 26624528.

- ^ a b c Maitland, Geoffrey C.; Rigby, Maurice; Smith, E. Brian; Wakeham, W. A. (1981). Intermolecular forces: their origin and determination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855611-X. OCLC 8139179.

- ^ Gallo, Paola; Rovere, Mauro (2021). Physics of liquid matter. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-68349-8. OCLC 1259588062.

- ^ a b c Chandler, David (1987). Introduction to modern statistical mechanics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504276-X. OCLC 13946448.

- ^ Finney, John L. (2013-02-22). "Bernal's road to random packing and the structure of liquids". Philosophical Magazine. 93 (31–33). Informa UK Limited: 3940–3969. Bibcode:2013PMag...93.3940F. doi:10.1080/14786435.2013.770179. ISSN 1478-6435. S2CID 55689631.

- ^ a b c Finney, J. L. (2015). Water: a very short introduction. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 48–52. ISBN 978-0-19-870872-8. OCLC 914537747.

- ^ Ludwig, Ralf (2005-07-11). "The Structure of Liquid Methanol". ChemPhysChem. 6 (7). Wiley: 1369–1375. doi:10.1002/cphc.200400663. ISSN 1439-4235. PMID 15991270.

- ^ Andrienko, Denis (October 2018). "Introduction to liquid crystals". Journal of Molecular Liquids. 267: 520–541. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.175. ISSN 0167-7322.

- ^ Chandler, David (2009-09-08). "Liquids: Condensed, disordered, and sometimes complex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (36): 15111–15112. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908029106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2741213. PMID 19805248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hansen, Jean-Pierre; McDonald, Ian R. (2013). Theory of simple liquids: with applications to soft matter. Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-387033-9. OCLC 855895733.

- ^ a b Kardar, Mehran (2007). Statistical physics of particles. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-87342-0. OCLC 148639922.

- ^ a b Gray, C. G.; Gubbins, Keith E.; Joslin, C. G. (1984–2011). Theory of molecular fluids. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855602-0. OCLC 10145548.

- ^ a b Marx, Dominik; Hutter, Jürg (2012). Ab initio molecular dynamics: basic theory and advanced methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89863-8. OCLC 869135580.

- ^ Fisher, I.Z. (1964), Statistical Theory of Liquids, The University of Chicago Press

- ^ Ceriotti, Michele; Cuny, Jérôme; Parrinello, Michele; Manolopoulos, David E. (2013-09-06). "Nuclear quantum effects and hydrogen bond fluctuations in water". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (39): 15591–15596. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11015591C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308560110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3785726. PMID 24014589.

- ^ Markland, Thomas E.; Ceriotti, Michele (2018-02-28). "Nuclear quantum effects enter the mainstream". Nature Reviews Chemistry. 2 (3) 0109. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. arXiv:1803.01037. doi:10.1038/s41570-017-0109. ISSN 2397-3358. S2CID 4938804.

- ^ Li, Xin-Zheng; Walker, Brent; Michaelides, Angelos (2011-04-04). "Quantum nature of the hydrogen bond". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (16): 6369–6373. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.6369L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016653108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3081025.

- ^ Born, Max (1940). "On the stability of crystal lattices". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 36 (2): 160–172. Bibcode:1940PCPS...36..160B. doi:10.1017/S0305004100017138. S2CID 104272002.

- ^ Born, Max (1939). "Thermodynamics of Crystals and Melting". Journal of Chemical Physics. 7 (8): 591–604. Bibcode:1939JChPh...7..591B. doi:10.1063/1.1750497. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15.

- ^ March, N.H.; Tosi, M.P. (2002). Introduction to Liquid State Physics. World Scientific. p. 7. Bibcode:2002ilsp.book.....M. doi:10.1142/4717. ISBN 978-981-3102-53-8.

- ^ Siegel, Ethan (2014-12-11). "Does water freeze or boil in space?". Starts With A Bang!. Retrieved 2022-02-10.

- ^ Silberberg 2009, pp. 188 and 502.

- ^ Miodownik, Mark (2019). Liquid rules: The Delightful and Dangerous Substances that Flow Through Our Lives. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-544-85019-4.

- ^ Mang, Theo; Dresel, Wilfried (2007). Lubricants and Lubrication. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-61033-4.

- ^ Wypych, George (2001). Handbook of Solvents. ChemTec Publishing. pp. 847–881. ISBN 978-1-895198-24-9.

- ^ Handbook of thermal conductivity of liquids and gases. Boca Raton Ann Arbor London [etc.]: CRC press. 1994. ISBN 978-0-8493-9345-7.

- ^ Erjavec, Jack (2005). Automotive Technology: A Systems Approach. Thomson/Delmar Learning. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-4018-4831-6.

- ^ Wendt, Gerald (1957). The prospects of nuclear power and technology. D. Van Nostrand Company. p. 266.

- ^ Huzel, Dieter K.; Huang, David H. (2000). Modern Engineering for Design of Liquid-Propellant Rocket Engines. Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics. Reston: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-56347-013-4.

- ^ Mull, Thomas E. (1998). HVAC principles and applications manual. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-044451-5.

- ^ Earle, R. L. (1983). Unit operations in food processing. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 56–62, 138–141. ISBN 0-08-025537-X. OCLC 8451210.

- ^ Mobley, R. Keith (1999). Fluid Power Dynamics. Elsevier. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-08-050662-3.

- ^ Dickey, Michael D. (2017-04-18). "Stretchable and Soft Electronics using Liquid Metals". Advanced Materials. 29 (27) 1606425. Wiley. Bibcode:2017AdM....2906425D. doi:10.1002/adma.201606425. ISSN 0935-9648. PMID 28417536. S2CID 205276487.

- ^ Cole, Tim; Khoshmanesh, Khashayar; Tang, Shi-Yang (2021-05-04). "Liquid Metal Enabled Biodevices". Advanced Intelligent Systems. 3 (7) 2000275. Wiley. doi:10.1002/aisy.202000275. ISSN 2640-4567. S2CID 235568215.

- ^ Tang, Shi-Yang; Tabor, Christopher; Kalantar-Zadeh, Kourosh; Dickey, Michael D. (2021-07-26). "Gallium Liquid Metal: The Devil's Elixir". Annual Review of Materials Research. 51 (1). Annual Reviews: 381–408. Bibcode:2021AnRMS..51..381T. doi:10.1146/annurev-matsci-080819-125403. ISSN 1531-7331. S2CID 236566966.

- ^ Liptak, Bela G. (2018). Instrument Engineers' Handbook, Volume Two: Process Control and Optimization. CRC Press. p. 807. ISBN 978-1-4200-6400-1.

- ^ Hickson, Paul; Borra, Ermanno F.; Cabanac, Remi; Content, Robert; Gibson, Brad K.; Walker, Gordon A. H. (1994). "UBC/Laval 2.7 meter liquid mirror telescope". The Astrophysical Journal. 436. American Astronomical Society: L201. arXiv:astro-ph/9406057. Bibcode:1994ApJ...436L.201H. doi:10.1086/187667. ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ Hickson, Paul; Racine, Réne (2007). "Image Quality of Liquid-Mirror Telescopes". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 119 (854). IOP Publishing: 456–465. Bibcode:2007PASP..119..456H. doi:10.1086/517619. ISSN 0004-6280. S2CID 120735632.

- ^ a b c Krüger, Timm; Kusumaatmaja, Halim; Kuzmin, Alexandr; Shardt, Orest; Silva, Goncalo; Viggen, Erlend Magnus (2016). The lattice Boltzmann method: principles and practice. Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-44649-3. OCLC 963198053.

- ^ Steinhauser, M. O. (2022). Computational multiscale modeling of fluids and solids: theory and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-98954-5. OCLC 1337924123.

- ^ Poling, Bruce E.; Prausnitz, J. M.; O'Connell, John P. (2001). The properties of gases and liquids. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-011682-2. OCLC 44712950.

- ^ Bird, R. Byron; Stewart, Warren E.; Lightfoot, Edwin N. (2007). Transport Phenomena (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-11539-8. Archived from the original on 2020-03-02. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ Span, R. (2000). Multiparameter Equations of State: An Accurate Source of Thermodynamic Property Data. Engineering online library. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-540-67311-8. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- ^ Huber, Marcia L.; Lemmon, Eric W.; Bell, Ian H.; McLinden, Mark O. (2022-06-22). "The NIST REFPROP Database for Highly Accurate Properties of Industrially Important Fluids". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 61 (42). American Chemical Society (ACS): 15449–15472. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.2c01427. ISSN 0888-5885. PMC 9619405. PMID 36329835. S2CID 249968848.

- ^ Tillner-Roth, Reiner; Friend, Daniel G. (1998). "A Helmholtz Free Energy Formulation of the Thermodynamic Properties of the Mixture {Water + Ammonia}". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 27 (1). AIP Publishing: 63–96. doi:10.1063/1.556015. ISSN 0047-2689.

- ^ Moffatt, H.K. (2015), "Fluid Dynamics", in Nicholas J. Higham; et al. (eds.), The Princeton Companion to Applied Mathematics, Princeton University Press, pp. 467–476

- ^ Wendt, John F.; Anderson, John D. Jr.; Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics (2008). Computational fluid dynamics: an introduction. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-85056-4. OCLC 656397653.

- ^ Pozrikidis, C. (2011). Introduction to theoretical and computational fluid dynamics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-990912-4. OCLC 812917029.

- ^ Monaghan, J J (2005-07-05). "Smoothed particle hydrodynamics". Reports on Progress in Physics. 68 (8). IOP Publishing: 1703–1759. Bibcode:2005RPPh...68.1703M. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/68/8/r01. ISSN 0034-4885. S2CID 5987481.

- ^ Lind, Steven J.; Rogers, Benedict D.; Stansby, Peter K. (2020). "Review of smoothed particle hydrodynamics: towards converged Lagrangian flow modelling". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 476 (2241) 20190801. The Royal Society. Bibcode:2020RSPSA.47690801L. doi:10.1098/rspa.2019.0801. ISSN 1364-5021. PMC 7544338. PMID 33071565. S2CID 221538477.

- ^ Español, Pep; Warren, Patrick B. (2017-04-21). "Perspective: Dissipative particle dynamics". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 146 (15). AIP Publishing: 150901. arXiv:1612.04574. Bibcode:2017JChPh.146o0901E. doi:10.1063/1.4979514. ISSN 0021-9606. PMID 28433024. S2CID 961922.

- ^ Gompper, G.; Ihle, T.; Kroll, D. M.; Winkler, R. G. (2009). "Multi-Particle Collision Dynamics: A Particle-Based Mesoscale Simulation Approach to the Hydrodynamics of Complex Fluids". Advanced Computer Simulation Approaches for Soft Matter Sciences III. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 1–87. arXiv:0808.2157. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-87706-6_1. ISBN 978-3-540-87705-9. S2CID 8433369.

Liquid

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and Examples

Definition and Key Characteristics

A liquid is a state of matter characterized as a nearly incompressible fluid that conforms to the shape of its container while maintaining a definite volume, positioning it as an intermediate phase between the rigid solid and the highly expansive gas states.[2][8] This behavior arises from the close packing of molecules with sufficient mobility to allow flow under applied forces, distinguishing liquids from the fixed shape of solids and the lack of volume retention in gases.[9] Key characteristics of liquids include their retention of a fixed volume under constant temperature and pressure, enabling them to occupy a specific amount of space regardless of container size, coupled with their inherent ability to flow and adapt to container geometry due to weak intermolecular forces relative to thermal energy.[9] Liquids exhibit strong resistance to compression, as their molecular spacing prevents significant volume reduction under moderate pressure, and they display surface tension, which minimizes surface area and leads to cohesive behaviors at interfaces.[10] The concept of the liquid state traces back to early philosophical observations, such as those by Aristotle in the 4th century BCE, who differentiated liquids from solids within his theory of four elements—earth, water, air, and fire—attributing fluidity to the relative mobility of elemental compositions.[11] Significant advancements occurred in the 19th century with the development of kinetic theory, pioneered by Rudolf Clausius and James Clerk Maxwell, which provided a molecular foundation for understanding fluid properties through statistical mechanics, initially focused on gases but foundational for later liquid state models.[12][13] Matter fundamentally exists in several states—solids with fixed shape and volume, liquids with fixed volume but adaptable shape, gases that expand to fill containers, and plasmas as ionized gases—each defined by the balance of kinetic energy and intermolecular interactions.[2]Common Liquids and Their Importance

Among elemental liquids, mercury stands out as the only metal that remains liquid at room temperature, exhibiting a silvery appearance and high density that has historically made it useful in thermometers and barometers despite its toxicity.[14] Bromine, a reddish-brown halogen, is another notable elemental liquid at standard conditions, valued for its reactivity in chemical synthesis and water treatment applications.[15] Molecular liquids are ubiquitous in everyday life and natural processes. Water, often called the universal solvent due to its ability to dissolve a wide range of substances, covers approximately 71% of Earth's surface and is fundamental to biological systems, serving as a medium for metabolic reactions, nutrient transport, and temperature regulation in organisms.[5][16] Ethanol, a simple alcohol, plays key roles as a solvent in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, a biofuel additive to reduce emissions, and a component in alcoholic beverages.[17] Oils, such as vegetable oils derived from plants, are essential in cooking for heat transfer and flavor enhancement, while mineral oils lubricate machinery and protect skin in personal care products.[18] The importance of these liquids extends across nature, industry, and daily life. Water's central role in life processes, from photosynthesis in plants to cellular functions in animals, underscores its indispensability for sustaining ecosystems and human health.[6] Hydrocarbons, liquid organic compounds like gasoline and diesel, power transportation and industry, providing efficient energy storage and contributing to modern economies.[19] Liquid crystals, intermediate states between liquids and solids, enable the functionality of liquid crystal displays (LCDs) in televisions, smartphones, and monitors by modulating light passage through electric fields.[20] Unique properties highlight the diversity of liquids. Liquid helium, when cooled below 2.17 K, exhibits superfluidity, flowing without viscosity and climbing container walls due to quantum effects, which aids low-temperature physics research.[21] Ionic liquids, salts that are molten at room temperature, serve as green solvents in chemical processes, offering low volatility and recyclability to minimize environmental impact compared to traditional organic solvents.[22]Macroscopic Properties

Density, Volume, and Compressibility

Liquids possess a well-defined volume under normal conditions, characterized by their density, which is defined as the mass per unit volume, .[23] This property distinguishes liquids from gases, which expand to fill their containers, and from solids, which maintain fixed shapes. For example, the density of water at 4°C and standard atmospheric pressure is approximately 1000 kg/m³, serving as a reference for many measurements.[24] Density in liquids typically decreases with increasing temperature due to thermal expansion, as the average intermolecular distances increase, leading to a larger volume for the same mass.[25] This variation is quantified through measurements at different temperatures, with most common liquids showing a consistent inverse relationship between density and temperature above their freezing points. One notable exception is water, which exhibits an anomalous density maximum at approximately 4°C under atmospheric pressure, where its density reaches about 999.97 kg/m³; below this temperature, density decreases as cooling continues toward the freezing point.[26] This behavior arises from structural changes in the hydrogen-bonded network and has significant implications for aquatic ecosystems, as it allows ice to float on water surfaces.[27] The near-constancy of liquid volume under pressure reflects their low compressibility compared to gases, where volume changes dramatically with pressure. Isothermal compressibility, defined as , quantifies this resistance to compression at constant temperature; for liquids, is typically on the order of to Pa, orders of magnitude smaller than for gases.[28] For water at room temperature, Pa.[29] This property ensures that liquids maintain structural integrity in applications like hydraulic systems. Thermal expansion in liquids is described by the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient, , which measures the fractional change in volume per unit temperature change at constant pressure.[30] Values of for typical liquids range from to K, indicating moderate expansion; for instance, ethanol has K near 20°C. In water's anomalous case, is negative between 0°C and 4°C, contributing to the density maximum.[31] The density of liquids directly underlies the principle of buoyancy, as articulated by Archimedes: the upward buoyant force on a submerged or partially submerged object equals the weight of the displaced fluid, given by , where is gravitational acceleration and is the volume of fluid displaced.[32] This force balances the object's weight for floating equilibrium when the object's density equals that of the liquid, explaining phenomena like ship flotation despite steel's higher density.[33]Viscosity, Flow, and Rheology

Viscosity quantifies the internal resistance of a liquid to shear stress, arising from intermolecular friction that opposes the relative motion of fluid layers. It is formally defined through Newton's law of viscosity, which states that the shear stress is proportional to the velocity gradient , expressed as , where is the dynamic viscosity coefficient.[34] This linear relationship holds for many common liquids under moderate shear rates, with units of viscosity in the SI system being pascal-seconds (Pa·s).[7] Liquid flow regimes are classified as laminar or turbulent based on the balance between inertial and viscous forces, predicted by the dimensionless Reynolds number , where is density, is characteristic velocity, is a length scale, and is viscosity.[35] In laminar flow, which predominates at low Reynolds numbers (typically for pipe flow), fluid particles move in smooth, parallel layers with viscous forces dominating.[36] Turbulent flow emerges at higher Reynolds numbers (often ), characterized by chaotic eddies and mixing, where inertia overwhelms viscosity and enhances momentum transfer.[36] The transition regime between these states depends on factors like pipe geometry but generally occurs around for cylindrical conduits.[35] Rheology encompasses the broader study of liquid deformation and flow under stress, distinguishing Newtonian fluids—where viscosity remains constant regardless of shear rate—from non-Newtonian fluids, whose viscosity varies with applied shear. Newtonian examples include water and most simple organic solvents, exhibiting predictable linear stress-strain behavior. Non-Newtonian liquids, common in biological and industrial contexts, include shear-thinning fluids like blood and polymer solutions, where viscosity decreases under increasing shear (e.g., blood flows more easily in narrow vessels), and shear-thickening fluids such as cornstarch suspensions, where viscosity increases with shear rate, leading to solid-like resistance under rapid stress.[37] These behaviors are modeled by power-law relations , with for shear-thinning and for shear-thickening. For steady, laminar flow of a Newtonian liquid through a straight, cylindrical tube, Poiseuille's law governs the volumetric flow rate , where is the tube radius, is the pressure difference, is viscosity, and is the tube length.[38] This equation highlights the strong dependence on radius (to the fourth power), making small changes in tube diameter profoundly affect flow, as derived from integrating the Navier-Stokes equations under no-slip boundary conditions.[39] Poiseuille's law applies strictly to incompressible, low-Reynolds-number flows and underpins applications like blood circulation modeling and microfluidic design.[38]Surface Tension and Interfaces

Surface tension is a property of liquids arising from the cohesive forces between molecules at the surface, quantified as the force per unit length, denoted by γ, that acts parallel to the surface to minimize its area. This results in phenomena such as the spherical shape of liquid droplets, where the surface contracts to achieve the lowest possible energy state.[40][41] The pressure difference across a curved liquid interface is described by the Young-Laplace equation: where ΔP is the pressure jump, and R₁ and R₂ are the principal radii of curvature. For a spherical droplet, this simplifies to ΔP = 2γ/R, explaining the higher internal pressure in small droplets compared to larger ones.[42][43] Capillary action occurs when surface tension drives a liquid up or down a narrow tube due to adhesive interactions with the tube walls, balanced against gravity. The height h of rise in a cylindrical tube is given by: where θ is the contact angle, ρ is the liquid density, g is gravitational acceleration, and r is the tube radius. Wetting liquids like water in glass (θ < 90°) rise, while non-wetting ones like mercury (θ > 90°) depress.[44][45] At liquid-liquid interfaces, such as oil and water, surface tension governs immiscibility and emulsion stability, with the interfacial tension being the difference in cohesive forces between the phases. Liquid-solid interfaces involve wetting characterized by the contact angle θ, where complete wetting (θ = 0°) spreads the liquid, and partial wetting (0° < θ < 180°) forms droplets. Gradients in surface tension, often due to temperature or concentration variations, induce the Marangoni effect, driving fluid flow from low to high tension regions, as seen in tear-like instabilities on wine surfaces.[46][47] Surface tension generally decreases with increasing temperature, as thermal energy weakens intermolecular forces; for water, it drops from about 72 mN/m at 20°C to 59 mN/m at 100°C. In soap bubbles, which have two surfaces, the excess pressure is ΔP = 4γ/R, and surfactants reduce γ to enable stable thin films, demonstrating surface tension's role in bubble formation and persistence.[48][43]Pressure Effects and Buoyancy

In liquids at rest, hydrostatic pressure increases linearly with depth due to the weight of the fluid above. The pressure at a depth below the surface is given by , where is the pressure at the surface, is the liquid density, and is the acceleration due to gravity.[49] This distribution assumes incompressible behavior and uniform density, though slight variations occur in practice.[50] Pascal's principle states that any change in pressure applied to an enclosed liquid is transmitted undiminished throughout the fluid and to the walls of its container.[51] This property enables the uniform force multiplication in hydraulic systems, where a small input force over a small area produces a larger output force over a larger area, as the pressure remains constant.[52] Buoyancy arises from the pressure difference on an immersed or floating object, resulting in an upward force equal to the weight of the displaced liquid, as described by Archimedes' principle.[53] An object floats if its average density is less than that of the liquid, sinks if greater, and remains suspended if equal, with the submerged volume adjusting to balance the weights.[32] For stability, the center of gravity of a floating object must lie below its center of buoyancy; otherwise, tilting produces a restoring torque that returns it to equilibrium, as seen in ship design where low placement of heavy cargo enhances this metacentric stability.[54][55] Under high pressure, liquids exhibit slight compressibility, leading to density increases that affect volume and pressure profiles. In deep ocean environments, water compressibility results in a density rise of about 4-5% at 10 km depth, influencing hydrostatic equilibrium and requiring corrections in pressure measurements.[56][57] In hydraulic systems, low compressibility ensures efficient pressure transmission and minimal energy loss, with fluids like mineral oils selected for bulk moduli exceeding 1.5 GPa to maintain performance under operational pressures up to hundreds of MPa.[58] Historically, Evangelista Torricelli demonstrated atmospheric pressure's role in supporting liquid columns in 1643 by inverting a mercury-filled tube into a dish, creating a vacuum above a 76 cm column balanced by air pressure, laying the foundation for barometers.[59]Thermal and Acoustic Properties

Liquids exhibit a range of thermal properties that govern their response to heat input, including specific heat capacity, thermal expansion, and thermal conductivity. The specific heat capacity at constant pressure, denoted , quantifies the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one unit mass of the liquid by one degree Kelvin without phase change, typically measured in J/(kg·K). For water at 25°C, is approximately 4180 J/(kg·K), which is notably higher than that of many other liquids like ethanol at around 2440 J/(kg·K).[60] Thermal expansion in liquids is characterized by the volume expansion coefficient , defined such that the relative change in volume is for a temperature change , reflecting the increase in molecular kinetic energy that weakens intermolecular forces. Unlike solids, liquids generally have higher values; for example, mercury has K at room temperature. Water displays an anomalous behavior in this property, contracting upon heating between 0°C and 4°C due to enhanced hydrogen bonding, resulting in a negative in that range, which contrasts with the positive expansion above 4°C.[31][61] Heat conduction within liquids follows Fourier's law, where the heat flux is proportional to the negative temperature gradient: , with being the thermal conductivity, typically on the order of 0.1–0.6 W/(m·K) for common liquids like water ( W/(m·K) at 20°C). This property arises from molecular collisions transferring kinetic energy, though liquids conduct heat less efficiently than metals due to weaker ordered structures. Additionally, liquids possess latent heats associated with phase changes: the latent heat of fusion is the energy per unit mass to melt a solid into liquid (e.g., 334 kJ/kg for water), while the latent heat of vaporization is the energy to convert liquid to vapor (e.g., 2260 kJ/kg for water at 100°C), both reflecting the energy to overcome intermolecular forces without temperature change.[62][60]/13%3A_Heat_and_Heat_Transfer/13.3%3A_Phase_Change_and_Latent_Heat) Acoustic properties of liquids involve the propagation and damping of sound waves, with the speed of sound given by , where is the bulk modulus (a measure of resistance to compression) and is density; for water, m/s at 20°C, significantly higher than in air due to stronger intermolecular forces yielding a larger . Sound attenuation in liquids occurs primarily through viscous effects, where internal friction dissipates wave energy as heat, with the classical Stokes' relation showing attenuation coefficient , being viscosity (as discussed in prior sections on rheology). Water's high specific heat and anomalous expansion contribute to its unique acoustic profile, enabling applications like ultrasound imaging and cleaning, where high-frequency waves (above 20 kHz) exploit cavitation in liquids for processes such as emulsification and medical diagnostics./Book%3A_University_Physics_I_-Mechanics_Sound_Oscillations_and_Waves(OpenStax)/17%3A_Sound/17.03%3A_Speed_of_Sound)[63][61][64]Microscopic Structure

Molecular Ordering and Intermolecular Forces

Liquids lack the long-range translational order of crystalline solids but display short-range molecular ordering, where neighboring molecules adopt preferred spatial arrangements over distances of a few molecular diameters. This local structure is quantitatively described by the radial distribution function , which represents the probability density of finding a pair of molecules separated by distance relative to a random distribution. Peaks in indicate regions of higher density due to intermolecular attractions, with the first peak typically corresponding to the nearest-neighbor shell and subsequent oscillations reflecting packing efficiency. Such functions are routinely obtained from scattering experiments, providing direct insight into the average local environment without assuming a periodic lattice.[65][66] A prominent example of short-range ordering occurs in liquid water, where each molecule forms a locally tetrahedral coordination with four neighbors through hydrogen bonds, resulting in distinct peaks in the oxygen-oxygen at approximately 2.8 Å and 4.5 Å. This arrangement arises from the directional nature of hydrogen bonds, creating transient open structures that persist on picosecond timescales despite thermal motion. In contrast to the rigid tetrahedral lattice of ice, liquid water's coordination is dynamic, with bond breaking and reforming allowing diffusion while maintaining local order.[67][68] The short-range ordering in liquids is governed by intermolecular forces, primarily van der Waals dispersion forces (induced dipole interactions), permanent dipole-dipole attractions, and hydrogen bonding in polar molecules. These forces promote cohesion, the attraction between like molecules that holds the liquid together, while adhesion refers to attractions between liquid molecules and unlike surfaces, influencing wetting behavior. For instance, strong hydrogen bonding in water enhances cohesion, leading to high surface tension, whereas weaker van der Waals forces dominate in nonpolar liquids like hydrocarbons. These interactions balance repulsive core potentials to yield the fluid-like density of liquids.[69][70] Compared to solids, which feature extended lattices with fixed positions, and gases, where molecules are too distant for significant correlations, liquids exhibit no long-range order but form transient clusters of locally ordered molecules that continually rearrange. These clusters, often 10–100 molecules in size, emerge from cooperative attractions and contribute to the liquid's viscosity without forming a stable network. In supercooled liquids cooled below their freezing point but remaining fluid, enhanced short-range ordering leads to the glass transition, where dynamics slow dramatically and the structure freezes into an amorphous solid-like state with persistent local motifs.[71][72] X-ray and neutron diffraction serve as primary experimental methods to probe pair correlations in liquids, with neutrons particularly sensitive to light elements like hydrogen due to isotopic contrast variation. In these techniques, the scattered intensity as a function of momentum transfer is Fourier-transformed to yield , revealing coordination numbers and bond lengths with atomic resolution. For example, neutron diffraction on liquid argon shows clear oscillations in up to several coordination shells, confirming the absence of periodicity beyond short ranges.[65][68]Thermodynamic Aspects of Liquid State

The liquid state is characterized by a delicate thermodynamic balance between energetic contributions from intermolecular interactions and entropic contributions from molecular positional freedom. The potential energy in liquids arises primarily from attractive and repulsive forces between molecules, which lower the internal energy compared to the ideal gas state while allowing for diffusive motion. This energy landscape is shaped by pairwise interactions, such as van der Waals forces, that stabilize the dense packing without the long-range order of solids. A key entropic factor stabilizing the liquid phase is the configurational entropy , which quantifies the multiplicity of accessible molecular configurations due to the absence of fixed lattice positions. Unlike the translational entropy dominating dilute gases, in liquids reflects the combinatorial possibilities of rearranging molecules within a constrained volume, often estimated through statistical mechanics as , where is the number of microstates. This entropy term, arising from the disordered yet correlated molecular arrangements, compensates for the energetic cost of density, preventing collapse to a solid or expansion to a gas. Intermolecular forces, briefly, modulate the depth of the potential wells that define these configurations. The thermodynamics of liquids defies simple approximations due to the absence of a small parameter for perturbation expansions, distinguishing them from gases (where low density enables ideal gas models) and solids (where harmonic oscillators suffice). Full statistical mechanical treatments are required, as interactions are neither weak nor separable into independent modes. The free volume theory addresses this by modeling molecular motion as diffusion within unoccupied space, where the available free volume per molecule determines transport and thermodynamic properties without relying on dilute or rigid limits. This approach highlights the intermediate nature of liquids, where density is comparable to solids but dynamics resemble gases.[73][74] The molar heat capacity at constant volume for liquids approximates per atom, akin to the Dulong-Petit value for solids, as vibrational modes dominate the energy storage, with translational and rotational contributions largely saturated. Deviations from this value occur due to anharmonic effects and subtle configurational rearrangements, leading to values slightly higher or lower depending on the liquid; for example, in simple liquids like argon, is about 2.8R at the triple point, reflecting partial excitation of anharmonic modes. The enthalpy of vaporization quantifies the energetic barrier to dispersing liquid molecules into vapor, typically on the order of 5–10 at the boiling temperature , underscoring the strength of cohesive interactions.[75][75] A distinctive thermodynamic indicator of the liquid state's emergence from the solid is the Lindemann criterion for melting, which posits that a crystal melts when the root-mean-square vibrational amplitude of atoms reaches approximately 10–15% of the nearest-neighbor distance. This threshold, derived from the onset of mechanical instability in the lattice, marks the transition where thermal fluctuations overwhelm harmonic restoring forces, allowing the system to access the higher-entropy liquid configurations without a small displacement parameter.[76]Quantum Mechanical Influences

In liquids composed of light elements at low temperatures, quantum mechanical effects become prominent, altering the classical behavior expected from molecular interactions. A quintessential example is superfluid helium-4 (^4He), where Bose-Einstein condensation (BEC) underlies the transition to a superfluid state. In this process, a macroscopic number of ^4He atoms, which are composite bosons with integer spin, occupy the lowest quantum energy state, leading to coherent quantum behavior observable on macroscopic scales. This phenomenon was first proposed by Fritz London in 1938 as the mechanism for superfluidity, linking the λ-transition to the degeneracy predicted by Bose-Einstein statistics. The persistence of helium as a liquid even at absolute zero under its own vapor pressure exemplifies the role of zero-point energy, arising from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. In ^4He, the light atomic mass and weak van der Waals forces result in a large zero-point motion that dominates the potential energy well, preventing the atoms from settling into a crystalline lattice. This quantum kinetic energy contribution is approximately seven times the depth of the interatomic potential, ensuring that solidification requires elevated pressures above 25 bar at 0 K.[77] Similarly, quantum tunneling and delocalization effects are evident in liquid para-hydrogen (p-H_2), a bosonic system where protons exhibit wave-like spreading. Path-integral simulations reveal that nuclear quantum effects lead to enhanced molecular delocalization, with wave packets showing non-classical diffusion and reduced effective viscosity compared to classical predictions.[78] In contrast, fermionic systems like liquid metals exhibit quantum influences through Fermi liquid theory, which describes the collective behavior of conduction electrons. Developed by Lev Landau in 1957, the theory posits that interacting fermions in metals such as sodium form quasiparticles that retain the properties of a non-interacting Fermi gas, albeit with renormalized parameters like effective mass. Experimental evidence includes deviations in plasma wave dispersion in liquid sodium, where the sharp Fermi surface leads to oscillatory potentials and enhanced long-range correlations beyond classical expectations.[79][80] The λ-transition in ^4He at 2.17 K marks the onset of superfluidity, characterized by a sharp peak in specific heat resembling the Greek letter λ, driven by the establishment of long-range quantum order via BEC. Below this temperature, the superfluid fraction increases, with zero viscosity and quantized vortex formation emerging as hallmarks of macroscopic quantum coherence. Path integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) simulations provide a powerful tool for probing these effects, treating particles as closed paths in imaginary time to compute properties like superfluid density through permutation exchanges, accurately reproducing the λ-point and phase diagram without approximations for bosonic liquids.[81][82]Experimental Probes of Structure

Scattering techniques provide essential insights into the microscopic structure of liquids by measuring density fluctuations and atomic correlations. X-ray scattering experiments yield the static structure factor S(q), from which the radial distribution function g(r) is derived via Fourier transform, quantifying pairwise atomic distances and local ordering in liquids like water, where peaks in g(r) correspond to first and second hydration shells at approximately 2.8 Å and 4.5 Å, respectively.[83] Neutron scattering complements this by exploiting isotopic contrasts to isolate contributions from specific atomic pairs, enabling precise mapping of intermolecular forces in complex liquids such as molten salts or alloys.[84] These methods reveal short-range order akin to that in solids but with diffusive broadening due to thermal motion. Inelastic variants of scattering extend probes to dynamics. Inelastic neutron scattering measures the dynamic structure factor S(q,ω), capturing phonon-like collective excitations and diffusion processes, with intermediate scattering functions indicating relaxation times on the order of picoseconds in simple liquids.[85] Similarly, inelastic X-ray scattering resolves momentum- and energy-dependent correlations, allowing real-space visualization of molecular motions via the Van Hove function, as demonstrated in studies of hydrogen bond breaking in liquid water.[86] Spectroscopic methods offer complementary views of liquid microstructure through molecular-level interactions. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) diffusometry, using pulsed field gradients, quantifies self-diffusion coefficients D, linking them to local viscosity and cage effects; in neat liquids, D values around 10^{-9} m²/s reflect barrier crossing in dense environments.[87] Raman and infrared (IR) spectroscopies detect vibrational spectra, where band positions and widths indicate bond strengths and anharmonicities; in liquid water, the asymmetric OH stretch at ~3400 cm⁻¹ broadens due to hydrogen bond diversity, distinguishing tetrahedral from disrupted structures.[88] Ultrafast spectroscopy captures transient structural changes. Femtosecond time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy, often at water-window energies, tracks core-level shifts following optical excitation, revealing solvation dynamics and charge redistribution in liquids on sub-picosecond scales.[89] For instance, in urea solutions, this technique observes femtosecond proton transfer, with spectral changes evidencing altered hydrogen bonding networks.[90] Additional probes focus on relaxation timescales tied to structure. Dielectric relaxation spectroscopy measures frequency-dependent permittivity to extract Debye relaxation times τ, probing dipole reorientation; in water, a primary τ ≈ 8.3 ps reflects cooperative H-bond dynamics, with faster sub-picosecond components from local librations.[91] Viscosity measurements, via rotational or capillary methods, indirectly inform structural timescales through Stokes-Einstein relations, where η ~ 1/D highlights caging effects in viscous liquids like glycerol.[92] Recent advancements leverage synchrotron and free-electron laser sources for real-time structural interrogation. High-brilliance synchrotron X-ray scattering enables sub-millisecond resolution of evolving microstructures, such as nanocrystal ordering in evaporating colloidal liquids.[93] Ultrafast techniques, integrating femtosecond pulses with scattering, overcome traditional limits, providing snapshots of non-equilibrium states in photoexcited liquids and advancing understanding of femtosecond-scale transients.[86]Phase Transitions

Solid-Liquid Transitions