Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to List of Spaniards.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of Spaniards

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

This list, in alphabetical order within categories, of notable hispanic people of Spanish heritage and descent born and raised in Spain, or of direct Spanish descent.

Note: The same person may appear under several headings.

| |||||

Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Spain. | |||||

Actors

[edit]

- Victoria Abril (born 1957)

- Georgina Amorós (born 1998)

- Elena Anaya (born 1975)

- Antonio Banderas (born 1960)

- Javier Bardem (born 1969)

- Pilar Bardem (1939–2021)

- Amparo Baró (1937–2015)

- Claudia Bassols (born 1979)

- Ana Belén (born 1951)

- Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey (born 1986)

- Miguel Bernardeau (born 1996)

- Juan Diego Botto (born 1975)

- Mario Casas (born 1986)

- Javier Cámara (born 1967)

- Inma Cuesta (born 1980)

- Mark Consuelos (born 1970)

- Úrsula Corberó (born 1989)

- Penélope Cruz (born 1974)

- Ana de Armas (born 1988)

- Carla Díaz (born 1998)

- Gabino Diego (born 1966)

- Lola Dueñas (1908–1983)

- Andrea Duro (born 1991)

- Paula Echevarría (born 1977)

- Itzan Escamilla (born 1997)

- Ester Expósito (born 2000)

- Angelines Fernández (1922–1994)

- Angy Fernández (born 1990)

- Bibiana Fernández (born 1954)

- Fernando Fernán Gómez (1921–2007)

- Alba Flores (born 1986)

- Elena Furiase (born 1988)

- Juan Luis Galiardo (1940–2012)

- Macarena García (born 1988)

- Sancho Gracia (1936–2012)

- Chus Lampreave (1930–2016)

- Alfredo Landa (1933–2013)

- Sergi López (actor) (born 1965)

- José Luis López Vázquez (1922–2009)

- Iván Massagué (born 1976)

- Carmen Maura (born 1945)

- Ana Milán (born 1973)

- Jordi Mollà (born 1968)

- Lina Morgan (1936–2015)

- Irene Montalà (born 1976)

- Sara Montiel (1928–2013)

- Abril Montilla Parra (born 2000)

- Paul Naschy (1934–2009)

- Najwa Nimri (born 1972)

- Eduardo Noriega (born 1973)

- Elsa Pataky (born 1976)

- María Pedraza (born 1996)

- Lucía Ramos (born 1991)

- Fernando Rey (1917–1994)

- Manu Ríos (born 1998)

- Blanca Romero (born 1976)

- Sara Sálamo (born 1992)

- Claudia Salas (born 1994)

- Marina Salas (born 1988)

- Fernando Sancho (1916–1990)

- Santiago Segura (born 1965)

- Miguel Ángel Silvestre (born 1982)

- Blanca Suárez (born 1988)

- Luis Tosar (born 1971)

- María Valverde (born 1986)

- Concha Velasco (1939–2023)

- Paz Vega (born 1976)

- Maribel Verdú (born 1970)

Artists

[edit]

- David Aja (born 1977), comics artist

- Leonardo Alenza (1807–1845), Romantic painter

- Hermenegildo Anglada (1871–1959), Catalan modernist painter

- Alonso Berruguete (c. 1488–1561), Spanish Renaissance painter and sculptor

- Pedro Berruguete (c. 1450–1504), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Aureliano de Beruete (1845–1912), painter

- Felipe Bigarny (c. 1475–1542), Spanish Renaissance sculptor

- María Blanchard (1881–1932), Cubist painter

- Lita Cabellut (born 1961), painter

- Eugenio Cajés (c. 1534–1574), Baroque painter

- Alonso Cano (1601–1667), Baroque painter

- Juan Caro de Tavira (fl. 17th century), painter

- Juan Carreño de Miranda (1614–1685), Baroque painter

- Ramon Casas (1866–1932), Catalan Modernist painter

- Antonio del Castillo (1616–1668), Baroque painter

- Charris (born 1962), painter

- Chumy Chúmez (1927–2003), cartoonist

- José de Creeft (1884–1982), Modernist sculptor and teacher

- Claudio Coello (1642–1693), Baroque painter

- Anabel Colazo (born 1993), illustrator and cartoonist

- Luis de la Cruz y Ríos (1776-1853) Spanish painter

- Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), Surrealist artist

- Óscar Domínguez (1906–1957), Surrealist artist

- Antonio María Esquivel (1806–1857), Romantic painter

- Joaquim Espalter (1809–1880), Orientalist painter

- Gregorio Fernández (1576–1636), Baroque sculptor

- Pasqual Ferry (born 1961), comics artist

- Marià Fortuny (1838–1874), Romantic painter

- Pablo Gargallo (1881–1934), Cubist sculptor

- Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926), Catalan Modernist architect and sculptor

- Francisco de Goya (1746–1828), Romantic painter and engraver

- Julio González (1876–1942), Cubist sculptor

- Eugenio Granell (1912–2001), Surrealist painter

- El Greco (1541–1614), Spanish Renaissance painter and sculptor

- Juan Gris (1887–1927), Cubist painter

- Carlos de Haes (1829–1898), Realist painter

- Francisco Herrera the Elder (1576–1656), painter

- Francisco Herrera the Younger (1622–1685), painter and architect

- Juan de Juanes (c. 1507–1579), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Antonio López (born 1936), Realist painter and sculptor

- José de Madrazo (1781–1859), Neoclassical painter

- Juan Bautista Maíno (1581–1649), Baroque painter

- Maruja Mallo (1902–1995), Surrealist painter

- Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (1612–1667), Baroque painter

- Pedro de Mena (1628–1688), Baroque sculptor

- Joaquin Mir (1873–1940), Catalan Modernist painter

- Joan Miró (1893–1983), Surrealist painter, sculptor and ceramist

- Juan Fernández Navarrete (1526–1579), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Isidre Nonell (1872–1911), Modernist painter

- Darío de Regoyos (1857–1913), Impressionist painter

- Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), Baroque painter

- Lluís Rigalt (1814–1894), Romantic painter

- Diego de Siloé (c. 1495–1563), Spanish Renaissance architect and sculptor

- Joaquín Sorolla (1863–1923), Impressionist painter

- Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618–1682), Baroque painter

- Pilar Nouvilas i Garrigolas (1854–1938), Spanish painter

- Bartolomé Ordóñez (c. 1480–1520), Spanish Renaissance sculptor

- Pedro Orrente (1580–1645), Baroque painter

- Rodrigo de Osona (c. 1440–c. 1518), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Carlos Pacheco (born 1961), comics artist

- Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (1553–1608), painter

- Laura Pérez Vernetti (born 1958), cartoonist and illustrator

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), painter and sculptor, co-founder of Cubism

- Francesc Ribalta (1565–1628), Baroque painter

- Luisa Roldán (1652–1706), Baroque sculptor

- Pedro Roldán (1624–1699), Baroque sculptor

- Julio Romero de Torres (1874–1930), Symbolist painter

- Eduardo Rosales (1836–1873), Purist painter

- Santiago Rusiñol (1861–1931), Catalan Modernist painter and poet

- Alonso Sánchez Coello (1531–1588), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Juan Sánchez Cotán (1560–1627), Baroque painter

- Antoni Tàpies (1923–2012), abstract Expressionist painter

- Trini Tinturé (1935–2024), cartoonist and illustrator

- Luis Tristán (c. 1585–1624), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Juan de Valdés Leal (1622–1690), Baroque painter

- Juan Van der Hamen (1596–1631), Romantic painter

- Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (1817–1870), Romantic painter

- Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Baroque painter

- Jenaro Pérez Villaamil (1807–1854), painter

- Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina (1505–1537), Spanish Renaissance painter

- Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945), painter

- Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1644), Baroque painter

Explorers and conquerors

[edit]

- Lope de Aguirre (1511–1561), soldier and adventurer, explored the Amazon River looking for El Dorado

- Diego de Almagro (1475–1538), explorer and conquistador, first European in Chile

- Luis de Moscoso Alvarado (1505–1551), explorer and conquistador.

- Juan Bautista de Anza (1736–1788), soldier and explorer, founded San Francisco, California

- Sebastián de Belalcázar (1480–1551), first explorer in search of El Dorado in 1535 and conqueror of Ecuador and southern Colombia (Presidencia of Quito), founded Quito 1534, Cali 1536, Pasto 1537, and Popayán 1537

- Fray Tomás de Berlanga (1487–1551), bishop of Panama, discovered the Galápagos Islands

- Juan Bermúdez (1450–1520), explorer and skier, discovered the Bermuda Islands

- Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c. 1490–c. 1559), first European to explore the southwestern of what is now the United States (1528–1536), also explored South America (1540–1542)

- Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (1499–1543), explorer, discovered California

- Andrés Dorantes de Carranza (ca. 1500–1550), explorer and one of the four last survivors of the Narváez expedition.

- Gabriel de Castilla (1577–1620), sailor; in 1603 he became probably the first man ever to sight Antarctica[citation needed]

- Cosme Damián Churruca (1761–1805), explorer, astronomer and naval officer, mapped the Strait of Magellan (1788–1789)

- Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (c. 1510–1554), explored New Mexico and other parts of the southwest of what is now the United States (1540–1542)

- Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), conquistador of the Aztec Empire, explorer of Baja California Peninsula

- Juan Sebastián Elcano (1476–1526), explorer and sailor, first man to circumnavigate the world

- Gaspar de Espinosa (1467/1477–1537), soldier and explorer, first European to reach the coast of Nicaragua, co-founder of Panama City

- Diego Duque de Estrada (1589–1647), soldier, explorer, writer

- Salvador Fidalgo (1756–1803), naval officer and cartographer, explored Alaska in 1790, he named Cordova, Port Gravina, and Valdez

- Miguel López de Legazpi (1502–1572), explored and conquered the Philippine Islands in 1565

- Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475–1519), first European to sight the Pacific Ocean, founder of Darién

- Francisco de Orellana (c. 1500–c. 1549), first European to explore the Amazon River

- Pedrarias Dávila (Pedro Arias de Ávila, 1440–1531), conquistador, founder of Panama and governor of Nicaragua

- Francisco Pizarro (1471–1541), conqueror of the Inca Empire in Peru

- Juan Ponce de León (1460–1521), first European to explore Florida (1513); founded the first European settlement in Puerto Rico (1508)

- Alonso del Castillo Maldonado (died c. 1540), explorer and one of the four last survivors of the Narváez expedition.

- Gaspar de Portolà (c. 1717–aft. 1784), explorer, founder of Monterey, California

- Bartolomé Ruiz (c. 1482–1532), first European to explore Ecuador; pilot for Pizarro and Columbus

- Hernando de Soto (1500–1542), explorer and conquistador, first European to explore the plains of eastern North America; discovered the Mississippi River and the Ohio River

- Pedro de Valdivia (c. 1500–1554), conquistador of Chile, founder of Santiago, Concepción, and Valdivia

- Pedro de los Ríos y Gutiérrez de Aguayo (died 1547), Royal Spanish governor of Castilla del Oro

- Vicente Yáñez Pinzón (c. 1461?–1514), explorer and sailor, first European to reach the coast of Brazil

- Amaro Rodríguez Felipe (c. 1678–1747), pirate

- Isabel de Urquiola (1854–1911), explorer

Film directors

[edit]

- Pedro Almodóvar (born 1949)

- Alejandro Amenábar (born 1972)

- Montxo Armendáriz (born 1949)

- Carlos Atanes (born 1971)

- Juanma Bajo Ulloa (born 1967)

- Jaume Balagueró (born 1968)

- Juan Antonio Bardem (1922–2002)

- Juan Antonio Bayona (born 1975)

- Icíar Bollaín (born 1967)

- José Luis Borau (1929–2012)

- Luis Buñuel (1900–1983)

- Mario Camus (1935–2021)

- Segundo de Chomón (1871–1929)

- Isabel Coixet (born 1962)

- Helena Cortesina (1903–1984)

- Agustín Díaz Yanes (born 1950)

- Víctor Erice (1940)

- Arantxa Echevarría (1968)

- Fernando Fernán Gómez (1921–2007)

- Amparo Fortuny

- Jesús Franco (1930–2013)

- José Luis Garci (born 1944)

- Luis García Berlanga (1921–2010)

- Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón (born 1942)

- Álex de la Iglesia (born 1965)

- Fernando León de Aranoa (born 1968)

- Bigas Luna (1946–2013)

- Ana Mariscal (1923–1995)

- Basilio Martín Patino (1930–2017)

- Julio Médem (born 1958)

- Pilar Miró (1940–1997)

- Josefina Molina (born 1936)

- Paul Naschy (1934–2009)

- Amando de Ossorio (1918–2001)

- Ventura Pons (1945–2024)

- Gracia Querejeta (1962)

- Clara Roquet (1988)

- José Luis Sáenz de Heredia (1911–1992)

- Carlos Saura (1932–2023)

- Santiago Segura (born 1965)

- David Trueba (born 1969)

- Fernando Trueba (born 1955)

- Agustí Villaronga (1953–2023)

- Benito Zambrano (born 1964)

- Lydia Zimmermann (born 1966)

- Iván Zulueta (1943–2009)

Leaders and politicians

[edit]Medieval ancestors

[edit]

- Liuvigild (519-586) was a Visigothic king of Hispania and Septimania from 567 to 586.

- Pelayo of Asturias (690–737), founding king of the Kingdom of Asturias

- Abd-ar-Rahman III (891–961), Emir (912–929) and Caliph of Córdoba (929–961)

- Al-Mansur (c. 938–1002), de facto ruler of Muslim Al-Andalus in late 10th and early 11th centuries

- Alfonso X of Castile (1221–1284)

Modern

[edit]

- Isabella of Castile, the Catholic (1451–1504), Queen of Castile and León (1474–1504, with Ferdinand)

- Ferdinand II, the Catholic (1452–1516), King of Aragon (1479–1516), Castile and León (1474–1504, with Isabella), Sicily (1479–1516), Naples (1504–1516) and Valencia (1479–1516)

- Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436–1517), cardinal, statesman, and regent of Spain

- Juana of Castile, frequently called "the Mad", queen of Castile and León; daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand

- Charles V (1500–1558), Holy Roman Emperor (1530–1556 but did not formally abdicate until 1558), ruler of the Burgundian territories (1506–1555), King of Spain (1516–1556), King of Naples and Sicily (1516–1554), Archduke of Austria (1519–1521), King of the Romans (or German King); often referred to as "Carlos V", but he ruled officially as "Carlos I", hence "Charles I of Spain"

- Philip II (1526–1598), King of Spain (1556–1598)

- Philip V (1683–1746), King of Spain (1700–1746)

- Charles III (1716–1788), King of Spain (1759–1788)

- Ferdinand VII (1784–1833), King of Spain (1813–1833)

- Manuel Godoy y Álvarez de Faria Ríos (1767-1851), First Secretary of State of the Kingdom from 1792 to 1797, 1st Prince of the Peace, 1st Duke of Alcudia, 1st Duke of Sueca, 1st Baron of Mascalbó

- Manuel de Aróstegui Sáenz de Olamendi (1758–1813), liberal Spanish politician[1]

Contemporary

[edit]

- Leopoldo O'Donnell y Jorris, (1809–1867), general and Prime Minister (1856; 1858–1863; 1864–1866); 1st Duke of Tetuán

- Juan Prim (1814–1870), general, liberal leader, revolutionary and statesman

- Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (1828–1897), Prime Minister

- Práxedes Mateo Sagasta (1825–1903), eight times Prime Minister

- Fernando de los Ríos Urruti (1879–1949) was a Minister of Justice, Minister of State, and a Spanish Politician.

- 20th and 21st centuries:

- Manuel Azaña (1880–1940), Premier (twice) and President during the Second Spanish Republic

- José María Aznar (born 1953), Prime Minister (1996–2004)

- Josep Borrell (born 1947), President of the European Parliament (2004–2007)

- Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo (1926–2008), Prime Minister (1981–1982)

- Santiago Carrillo (1915–2012), the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) from 1960 to 1982

- Buenaventura Durruti (1896–1936), anarchist leader

- Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Army general and president, ruled Spain for 36 years as "Caudillo" (1939–1975)

- María Teresa Fernández de la Vega (born 1949), Spanish Socialist Workers' Party politician and the first female Vice President

- Felipe González (born 1942), Prime Minister (1982–1996)

- Sara Giménez Giménez (born 1977), president, Fundación Secretariado Gitano

- Dolores Ibárruri (1895–1989), known as "La Pasionaria", leader of the Spanish Civil War and communist politician

- Eugenio Montero Ríos (1832–1914) Spanish Prime Minister and President of the Senate of Spain.

- Juan Carlos I (born 1938), King of Spain (1975–2014)

- Federica Montseny (1905–1994), Minister of Health (1936–1937) and anarchist - first woman to be a minister in Spanish History

- José Antonio Primo de Rivera (1903–1936)

- Mariano Rajoy (born 1955), Prime Minister (2011–2018)

- Rodrigo Rato (born 1949), managing director of the IMF since 2004

- Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba (1951–2019), Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Education, Minister of the Interior and Minister of Defence

- Benjamín Rubio (1925–2007), trade unionist

- Pedro Sánchez (born 1972), Prime Minister (2018–present)

- Ana Sigüenza (born c. 1957), general secretary of the CNT (2000–2003) and anarchist - first woman to be secretary general of a national trade union centre in Spain

- Adolfo Suárez (1932–2014), Prime Minister (1976–1981)

- Javier Solana (born 1942), Secretary General of NATO (1995–1999) and High Representative (since 1999) of the CFSP of the Council of the European Union

- José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (born 1960), Prime Minister (2004–2011)

- Felipe VI (born 1968), King of Spain since 2014

Literature

[edit]

- Rafael Alberti (1902–1999), poet, Cervantes Prize laureate (1983)

- Vicente Aleixandre (1888–1984), poet, Nobel Prize laureate (1977)

- Concepción Arenal (1820–1893), writer and feminist

- Matilde Asensi (1962), writer

- Lola Badia (1951), philologist, medievalist

- Elia Barceló (1957), writer

- Pío Baroja (1872–1956), novelist of the Generation of '98

- Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer (1836–1870), romantic poet and tale writer

- Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (994-1091), poet

- Antonio Buero Vallejo (1916–2000), playwright of the Generation of '36

- Carmen de Burgos (1867–1932), writer and journalist

- Fernán Caballero (1796–1877), writer and novelist

- Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600–1681), playwright and poet of the Spanish Golden Age

- Clara Campoamor (1888–1972), essayist and politician

- Victoria Camps (born 1941), essayist and philosopher

- Inmaculada Casal (born 1964), journalist and television presenter

- Sofía Casanova (1861–1958), novelist, poet and journalist

- Rosalía de Castro (1837–1885), romanticist and poet

- Camilo José Cela (1916–2002), novelist, Nobel Prize laureate (1989)

- Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), novelist, poet and playwright, author of Don Quixote (1605 and 1615)

- Rosa Chacel (1898–1994), writer, poet and essayist

- Carmen Conde Abellán (1907–1996), writer

- Carolina Coronado (1820–1911), poet

- Miguel Delibes (1920–2010), novelist, Cervantes Prize laureate (1993)

- María Dueñas (born 1964), writer and professor

- José Echegaray (1832–1916), dramatist, Nobel Prize laureate (1904)

- Concha Espina (1869–1955), poet, writer and journalist

- Cristina Fernández Cubas (born 1945), writer and journalist

- Amanda Figueras, journalist and writer

- Gloria Fuertes (1917–1998), poet and writer

- Federico García Lorca (1898–1936), poet and dramatist of the Generation of '27

- Alicia Giménez Bartlett (born 1951), writer

- Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda (1814–1873), writer

- Luis de Góngora (1561–1627), lyric poet considered to be among the most prominent Spanish poets of all time

- Almudena Grandes (1960–2021), writer

- Jorge Guillén (1893–1984), poet, Cervantes Prize laureate (1976), four-time Nobel Prize nominee

- Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881–1958), poet, Nobel Prize laureate (1956)

- John of the Cross (1542–1591), mystic poet

- Carmen Laforet (1921–2004), writer

- María de la O Lejárraga (1874-1974), feminist writer, dramatist, translator and politician

- María Teresa León (1903–1988), writer and novelist

- Elvira Lindo (born 1962), writer and journalist

- Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (1744–1811), main figure of the Spanish Age of Enlightenment, philosopher, statesman, poet and essayist

- Antonio Machado (1875–1939), leading poet of the Generation of '98

- Salvador de Madariaga (1886–1978), essayist and two-time Nobel Prize nominee

- Jorge Manrique (1440–1479), major Castilian poet

- Juan Marsé (1933–2020), novelist and Cervantes prize laureate

- Carmen Martín Gaite (1925–2000), writer

- Ana María Matute (1925–2014), writer

- Eduardo Mendoza (born 1943), novelist and Cervantes prize laureate

- Sara Mesa (born 1976), writer

- María Moliner (1900–1981), librarian and lexicographer

- Rosa Montero (born 1951), writer and journalist

- Cristina Morales (born 1985), writer

- Juliana Morell (1594–1653), poet and humanist

- Julia Navarro (born 1953), writer

- Margarita Nelken (1898–1966), writer, essayist and feminist

- Emilia Pardo Bazán (1851–1921), writer of prose and poetry who introduced naturalism and feminist ideas to Spanish literature

- Ánxeles Penas (born 1943), poet

- Benito Pérez Galdós (1843–1920), realist novelist considered by some to be second only to Cervantes in stature as a Spanish novelist

- Arturo Pérez-Reverte (born 1951), best-selling novelist and journalist, member of the Royal Spanish Academy

- Marta Pessarrodona (born 1941), Spanish poet, literary critic, essayist, biographer

- Francesc Pi i Margall (1824–1901), romanticist writer who was briefly president of the short-lived First Spanish Republic

- Berta Piñán (born 1963), writer, poet, politician

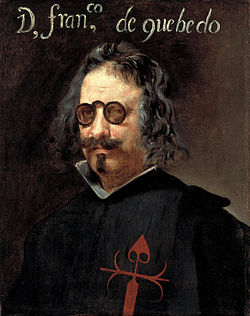

- Francisco de Quevedo (1580–1645), novelist, essayist and poet, master of Conceptism

- Carme Riera (born 1948), novelist and essayist

- Mercedes Salisachs (1916–2014), writer

- Clara Sánchez (born 1955), writer

- Marta Sanz (born 1967), writer

- Enrique Tierno Galván (1918–1986), essayist and lawyer who served as Mayor of Madrid from 1979 to 1986

- Josefina de la Torre (1907–2002), writer

- Àxel Torres (born 1983), sports (football) journalist

- Maruja Torres (born 1943), journalist and writer

- Esther Tusquets (1936–2012), writer

- Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936), Basque essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca

- Ramón María del Valle-Inclán (1866–1936), radical dramatist, novelist and member of the Generation of '98

- Garcilaso de la Vega (1501–1536), Renaissance poet who was influential in introducing Italian Renaissance verse forms, poetic techniques, and themes to Spain

- "El Inca" Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616), born Gómez Suárez de Figueroa, first mestizo author in Spanish language, known for his chronicles of Inca history

- Félix Lope de Vega (1562–1635), one of the key literary figures of the Spanish Golden Age

- María Zambrano (1904–1991), writer and philosopher

- María de Zayas y Sotomayor (1590–1660), female novelist of the Spanish Golden Age, and one of the first Spanish feminist authors

Military

[edit]

- 3rd Duke of Alba (Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 1507–1582), general and governor of the Spanish Netherlands (1567–1573)

- Diego García de Paredes (1466–1534), soldier and duellist, he never commanded an army or rose to the position of a general, but he was a notable figure in the wars, when personal prowess had still a considerable share in deciding combat.

- Diego de los Ríos (1850–1911) Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines

- Don Juan de Austria (1547–1578), general and admiral; defeated Müezzinzade Ali Pasha in the Battle of Lepanto (1571)

- Blas de Lezo (1687–1741), admiral; leading 6 warships and 3.700 men, defeated a British invasion force of 28.000 troops and 186 warships, during the Siege of Cartagena in 1741

- Álvaro de Bazán, 1st Marquis of Santa Cruz (1526–1588), admiral

- Francisco Javier Castaños, 1st Duke of Bailén (1758–1852), general; he defeated Dupont in the Battle of Bailén (1808)

- El Cid (Rodrigo 'Ruy' Díaz de Vivar, c. 1045–1099), knight and hero

- Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, "El Gran Capitán" (1453–1515), general and strategist of Early modern warfare

- Luis de Córdova y Córdova (1706– 1796), admiral. During the Anglo-Spanish War captured two merchant convoys totalling 79 ships.

- Francisco Franco (1892–1975), general; from 1939 caudillo and formal Head of State of Spain

- Manuel Alberto Freire de Andrade y Armijo (1767–1835), Spanish cavalry officer and general officer during the Peninsular War, and later Defense Minister

- Bernardo de Gálvez (1746–1786), Field Marshal and governor of Louisiana, Spanish hero of the American Revolution

- Juan Martín Díez, "El Empecinado" (1775–1825), head of guerrilla bands promoted to Brigadier-General of cavalry during the Peninsular War

- Casto Méndez Núñez (1830–1880), admiral

- Pedro Navarro, Count of Oliveto (c. 1460–1528), prominent general

- Álvaro de Navia Osorio y Vigil, Marqués de Santa Cruz de Marcenado, (1684–1732), general, author of the treatise Reflexiones Militares (Military Reflections)

- Pablo Morillo y Morillo (1775–1837), Count of Cartagena and Marquess of La Puerta, a.k.a. El Pacificador (The Peace Maker) was a Spanish general who fought in the napoleonic wars and hispanoamerican war of independence.

- Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma (1545–1592), Spanish general and military governor of the Spanish Netherlands

- Francisco Pérez de Grandallana (1774–1841), brigadier of the Royal Spanish Navy

- Ambrosio Spinola, marqués de los Balbases (1569–1630), general

- Fernando Villaamil (1845–1898), naval officer, designer of the first destroyer

Models

[edit]

- Esther Cañadas (born 1977)

- Verónica Homs (born 1980)

- Jon Kortajarena (born 1985)

- Sheila Marquez (born 1985)

- Judit Mascó (born 1969)

- Blanca Padilla (born 1995)

- Marina Pérez (born 1984)

- Inés Sastre (born 1973)

Musicians

[edit]Classical

[edit]

- Isaac Albéniz (1860–1909), composer

- Salvador Bacarisse (1898–1963), composer

- Pablo Casals (1876–1973), cello player and conductor

- Juan de Espinosa (d. 1528), composer and music theorist

- Manuel de Falla (1876–1946), composer

- Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos (1933–2014), conductor

- Enrique Granados (1867–1916), composer

- Enrique Jordá (1911–1996), conductor, music director of the San Francisco Symphony (1954–1963)

- Francisco Lara (born 1968), composer and conductor

- Alicia de Larrocha (1923–2009), pianist

- Vicente Martín y Soler (1754–1806), composer

- Sofía Noel (1915–2011), Belgian-born soprano and ethnomusicologist

- Luis de Pablo (1930–2021), composer

- Blas de Laserna, composer

- María Teresa Oller (1920–2018), composer and folklorist

- Eugenia Osterberger (1852–1932), Galician pianist and composer

- Joaquín Rodrigo (1901–1999), composer and pianist, known for his Concierto de Aranjuez

- Gaspar Sanz (1640–1710), composer, dominate figure of Spanish baroque music

- Jordi Savall (born 1941), early and baroque music conductor and viol player

- Andrés Segovia (1893–1987), classical guitarist

- Ángel Sola (1859–1910), bandurrista

- Antonio Soler (1729–1783), composer, known for his harpsichord sonatas

- Francisco Tárrega (1852–1909), composer and classical guitarist

- Joaquín Turina (1882–1949), composer

- Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611), most famous composer of the 16th century (late Renaissance) in Spain

- Paco de Lucía (1947–2014), flamenco guitarist and composer; regarded as one of the finest guitarists in the world and the greatest living guitarist of the flamenco genre

Opera singers

[edit]

- Victoria de los Ángeles (1923–2005), soprano

- Maite Arruabarrena (born 1964), mezzo-soprano

- Ainhoa Arteta (born 1964), soprano

- Teresa Berganza (1935–2022), mezzo-soprano

- Montserrat Caballé (1933–2018), soprano

- Avelina Carrera (1871–1939), soprano from Barcelona

- Nancy Fabiola Herrera (born 19??), mezzo-soprano

- José Carreras (born 1946), one of The Three Tenors

- Antonio Cortis (1891–1952), tenor

- Plácido Domingo (born 1941), one of The Three Tenors

- Manuel del Pópulo Vicente García (1775–1832), tenor

- María Gay (1879–1943), mezzo-soprano

- Alfredo Kraus (1927–1999), tenor

- Hipólito Lázaro (1887–1974), tenor

- Carlos Marín (1968-2021), baritone, member of operatic quartet Il Divo

- María José Montiel (born 1968), mezzo-soprano

- María Orán (1943–2018), soprano

- Adelina Patti (1843–1919), coloratura soprano

- Conchita Supervía (1895–1936), mezzo-soprano

- Francisco Viñas (1863–1933), tenor

Singers

[edit]

- Edward Aguilera (born 1976), Menudo singer

- Dolores Agujetas (born 1960), flamenco singer

- Alaska (born 1963), pop-rock singer

- Pablo Alborán (born 1989), singer

- Eva Amaral (born 1972), pop and folk rock singer

- Ana Belén (born 1951), singer and actress

- David Bisbal (born 1979), singer-songwriter

- Miguel Bosé (born 1956), pop singer

- Nino Bravo (1944–1973), singer

- Camarón de la Isla (1950–1992), flamenco singer, real name José Monje Cruz

- Luz Casal (born 1958), pop singer

- Estrellita Castro (1908–1983), singer and actress

- Montse Cortés (born 1972), flamenco singer

- Rocío Dúrcal (1944–2006), singer

- Manolo Escobar (1931–2013), singer

- Manolo García (born 1955), singer-songwriter

- Enrique Iglesias (born 1975), pop singer

- Julio Iglesias (born 1943), singer

- Antonio José (born 1995), singer

- Rocío Jurado (1946–2006), singer

- Gloria Lasso (1922–2005), singer

- Lola Flores (1923–1995), singer and flamenco dancer

- Lolita Flores (born 1958), singer and actress

- Dani Martín (born 1977), singer

- Víctor Manuel (born 1947), singer

- Shakira (born 1977), singer

- Abraham Mateo (born 1998), singer

- Alba Molina (born 1978), Flamenco singer

- Amaia Montero (born 1976) pop singer

- Lola Montes, (1898-1983), Spanish singer

- Sara Montiel (1928–2013), singer and actress, real name María Antonia Abad

- Carlos Núñez (born 1971), bagpipes and Galician (Celtic) music performer

- Aitana Ocaña Morales (born 1999), spanish singer-songwriter

- Amaia Romero (born 1999),spanish singer-songwriter

- Paloma San Basilio, singer

- Jordi Savall (born 1941), film music composer

- José Luis Perales (born 1945), singer

- Camilo Sesto (1946–2019), singer

- Isabel Pantoja (born 1956), singer

- Niña Pastori, (born María Rosa García García in 1978), flamenco singer

- José Luis Perales (born 1945), singer

- Raphael (born 1943), pop singer

- Rosalía (born 1992), singer-songwriter

- Joaquín Sabina (born 1949), singer-songwriter

- Marta Sanchez (born 1966), singer-songwriter

- Alejandro Sanz (born 1968), pop singer

- Joan Manuel Serrat (born 1943), Catalan singer-songwriter

- Chanel Terrero (born 1991), singer

- Ana Torroja (born 1959), pop rock singer

- Enrique Urquijo (1960–1999), founder of the band Los Secretos with his brother Álvaro, lead voice and composer

Philosophers and humanists

[edit]

- Alfonso X of Castile (1221–1284), "El Sabio" ("The Wise")

- Francisco de Enzinas (1518–1552), humanist and translator of the New Testament

- Francisco Giner de los Ríos (1839–1915), philosopher, educator and one of the most influential Spanish intellectuals at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

- Baltasar Gracián (1601–1658), author of El Criticón, influenced European philosophers such as Schopenhauer

- Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484–1566), humanist, advocate of the rights of Native Americans

- Ramon Llull (1232–1315), philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, and Christian apologist from the Kingdom of Majorca. Inventor of a philosophical system known as the Art and a precursor of the computer, pioneer of computation theory.

- Salvador de Madariaga (1886–1978), humanist, co-founder of the College of Europe (1949)

- Gregorio Marañón (1887–1960), humanist and medical scientist, important intellectual of the 20th century in Spain

- Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo (1856–1912), philologist, historian and erudite

- Julián Marías (1914–2005), philosopher; wrote the History of Philosophy

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869–1968), philologist, historian and erudite member of Generation of '98

- Antonio de Nebrija (1441–1522), scholar, published the first grammar of the Spanish language (Gramática Castellana, 1492), which was the first grammar produced of any Romance language

- Rocío Orsi (1976–2014), philosopher, professor

- José Ortega y Gasset (1883–1955), philosopher, social and political thinker, author of The Revolt of the Masses (1930)

- Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590), Franciscan missionary, researched Nahua culture and Nahuatl language and compiled an unparalleled work in Spanish and Náhuatl

- George Santayana (1863–1952), philosopher, taught at Harvard, author of The Sense of Beauty (1896) and The Life of Reason (1905–1906)

- Fernando Savater (born 1947), philosopher and essayist, known for his writings on ethics

- Francisco Suárez (1548–1617), one of the most influential scholastics after Thomas Aquinas

- Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936), existentialist writer and literary theoretician

- Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540), prominent figure of Renaissance humanism, taught at Leuven and Oxford (while tutor to Mary Tudor)

- Xavier Zubiri (1889–1983), philosopher, critic of classical metaphysics

Religion

[edit]

- Maria Pilar Bruguera Sábat (1906–1994), Roman Catholic nun and physician

- Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436–1517), religious reformer, bishop, cardinal and statesman

- St Dominic of Guzmán (1170–1221), founder of the Order of Preachers

- St Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636), bishop, humanist and doctor of the Church

- St Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), founder of the Society of Jesus

- St John of Avila (1500–1569), priest, preacher, theologian and mystic

- St John of the Cross (1542–1591), mystic and monastic reformer, doctor of the Church

- Saints Nunilo and Alodia (died c. 842/51), child martyrs

- Vicente Enrique y Tarancón (1907–1994), bishop, cardinal and president of the Spanish Episcopal Conference

- St Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), mystic and monastic reformer, doctor of the Church

- Tomás de Torquemada (1420–1498), Grand Inquisitor

- St Joaquina Vedruna (1783–1854), founder of the Carmelite Sisters of the Charity

- St Vincent Martyr (died c. 304), deacon martyr

- St. Toribio de Mogrovejo (1538–1606), prelate of the Catholic Church who served as the Archbishop of Lima from 1579 until his death

- St Francis Xavier (1506–1552), missionary and co-founder of the Society of Jesus

- Peter of Saint Joseph Betancur (1626–1667), missionary in Guatemala

- José de Anchieta (1534–1597), missionary in Brazil; founder of city São Paulo and co-founder of city Rio de Janeiro

- Bernardo de Alderete (1565–1641), canon of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba

- Ángela María de la Concepción (1649-1690), nun, mystical writer, and reformer; founder of Monasterio de las trinitarias de El Toboso and of the Trinitarias contemplativas

Science and technology

[edit]

- José de Acosta (1540–1600), one of the first naturalists and anthropologists of the Americas

- Alex Aguilar (born 1957), professor of Animal Biology at the University of Barcelona

- Susana Agustí (graduated 1982), biological oceanographer, educator

- José María Algué (1856–1930), meteorologist, inventor of the barocyclometer, the nephoscope, and the microseismograph

- Rafael Alvarado Ballester (1924–2001)

- Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont (1553–1613), registered design for steam-powered water pump for use in mines (1606)

- Francisco Javier de Balmis (1753–1819), physician, leader of the first international vaccination campaign in history

- Ignacio Barraquer (1884–1965), leading ophthalmologist, pioneer of cataract surgery

- José Ignacio Barraquer (1916–1998), leading ophthalmologist, father of modern refractive surgery; invented the microkeratome and the cryolathe, developed the surgical procedures of keratomileusis and keratophakia

- Agustín de Betancourt (1758–1824), engineer, worked in many rangs from steam engines and balloons to structural engineering and supervised the planning and construction of Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, Nizhny Novgorod, and other Russian cities

- Pino Caballero Gil (born 1968), computer scientist

- Ángel Cabrera (1879–1960), naturalist, investigated South American fauna

- Blas Cabrera (1878–1945), physicist, worked in the domain of experimental physics with focus in the magnetic properties of matter

- Nicolás Cabrera (1913–1989), physicist, did important work on the theories of crystal growth and the oxidisation of metals

- Santiago Calatrava (born 1951), architect, sculptor and structural engineer

- Pedro Carlos Cavadas Rodríguez (born 1965), pioneering surgeon

- Juan de la Cierva (1895–1936), aeronautical engineer, pioneer of flying with rotary wings, inventor of the autogyro

- Juan Ignacio Cirac Sasturain (born 1965), one of the pioneers of the field of quantum computing and quantum information theory

- Josep Comas i Solà (1868–1937), astronomer, discovered the periodic comet 32P/Comas Solá and 11 asteroids, and in 1907 observed limb darkening of Saturn's moon Titan (the first evidence that the body had an atmosphere)

- Jerónimo Cortés (c. 1560 - c. 1611), mathematician, astronomer, naturalist and Valencian compiler

- Carmen Domínguez (born 1969), glaciologist

- Pedro Duque (born 1963), astronaut and veteran of two space missions

- Fausto de Elhúyar (1755–1833), chemist, joint discoverer of tungsten with his brother Juan José de Elhúyar in 1783

- Bernardo Hernández (born 1970), entrepreneur, leading figure in technology

- Francisco Hernández (1514–1587), botanicist, carried out important research about the Mexican flora

- Jorge Juan y Santacilia (1713–1773), mathematician and naval officer. Determined that the Earth is not perfectly spherical but is oblat. Also measured the heights of the Andes mountains using a barometer.

- Carlos Jiménez Díaz (1898–1967), doctor and researcher, leading figure in pathology

- Asunción Linares (1921–2005), paleontologist

- Gregorio Marañón (1887–1960), doctor and researcher, leading figure in endocrinology

- Rafael Mas Hernández (1950–2003), geographer

- Narcís Monturiol (1818–1885), physicist and inventor, pioneer of underwater navigation and first machine powered submarine

- José Celestino Bruno Mutis (1732–1808), botanicist, doctor, philosopher and mathematician, carried out relevant research about the American flora, founded one of the first astronomic observatories in America (1762)

- Severo Ochoa (1905–1993), doctor and biochemist, achieved the synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA), Nobel prize laureate (1959)

- Mateu Orfila (1787–1853), doctor and chemist, father of modern toxicology, leading figure in forensic toxicology

- Joan Oró (1923–2004), biochemist, carried out important research about the origin of life, he worked with NASA on the Viking missions

- Isaac Peral (1851–1895), engineer and sailor, designer of the first fully operative military submarine

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934), father of Neuroscience, Nobel prize laureate (1906)

- Julio Rey Pastor (1888–1962), mathematician, leading figure in geometry

- Wifredo Ricart (1897–1974), engineer, designer and executive manager in the automotive industry

- Andrés Manuel del Río (1764–1849), geologist and chemist, discovered vanadium (as vanadinite) in 1801

- Pío del Río Hortega (1882–1945), neuroscientist, discoverer of the microglia or Hortega cell

- Josef de Mendoza y Ríos (1761–1816) was a Spanish astronomer and mathematician of the 18th century, famous for his work on navigation.

- Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente (1928–1980), naturalist, leading figure in ornithology, ethology, ecology and science divulgation

- Enrique Rojas Montes (born 1949)

- Margarita Salas (1938–2019), biochemist, molecular geneticist and researcher

- Miguel Sarrias Domingo (1930–2002) was medical director of the Institut Guttmann in Barcelona.

- Miguel Servet (1511–1553), scientist, surgeon and humanist; first European to describe pulmonary circulation

- María Dolores Soria (1948–2004), paleontologist, researcher, professor, and biologist

- Esteban Terradas i Illa (1883–1950), mathematician, physicist and engineer

- Leonardo Torres Quevedo (1852–1936), engineer and computer scientist, pioneer of automated calculation machines, inventor of El Ajedrecista, pioneer of radio control, designer of the three-lobed non-rigid Astra-Torres airship and the funicular over the Niagara Falls

- Eduardo Torroja (1899–1961), civil engineer, structural architect, world-famous specialist in concrete structures

- Josep Trueta (1897–1977), doctor, his new method for treatment of open wounds and fractures helped save many lives during World War II

- Antonio de Ulloa (1716–1795), scientist, soldier and author; joint discoverer of element platinum with Jorge Juan y Santacilia (1713–1773)

- Arnold of Villanova (c. 1235–1311), alchemist and physician, he discovered carbon monoxide and pure alcohol

Social scientists

[edit]

- Gurutzi Arregi (1936–2020), Basque ethnographer

- Martín de Azpilicueta (1492–1586), economist, member of the School of Salamanca, precursor of the quantitative theory of money

- Mercedes Bengoechea (born 1952), feminist sociolinguist, professor

- Agustín Blánquez Fraile (1883–1965], historian and latinist

- Manuel Castells (born 1942), sociologist, author of trilogy The Information Age

- María Ángeles Durán (born 1942), sociologist and economist

- Manuel Fernández López (1947–2014)

- Salvador Giner (1934–2019), sociologist, he had researched on social theory, sociology of culture and modern industrial society

- Jesús Huerta de Soto (born 1956), major Austrian School economist

- Juan José Linz (1926–2013), Sterling Professor of Political and Social Science at Yale; Prince of Asturias Award (1987) and Johan Skytte Prize (1996) laureate

- Pilar Acosta Martínez (1938–2006), prehistorian and archeologist

- Patricia Mayayo (born 1967), art historian

- Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz (1893–1984), historian, prominent specialist in medieval Spanish history

- Juan Uría Ríu (1891–1979), historian

- Joseph de la Vega (1650–1692), businessman, wrote Confusion of Confusions (1688), first book on stock markets

- Francisco de Vitoria (c. 1480/86–1546), member of the School of Salamanca, precursor of international law theory

Sports

[edit]Athletics

[edit]- Ruth Beitia, (born 1979), women's high jump gold medalist at the 2016 Olympics

- Fermín Cacho Ruiz (born 1969), 1500 metres gold (1992 Olympics) and silver (1996 Olympics) medalist

- Daniel Plaza, 20 km race walk gold medalist (1992 Olympics)

Basketball

[edit]

- Antonio Díaz-Miguel (1933–2000), coach, enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1997

- Pau Gasol (born 1980), FC Barcelona and Los Angeles Lakers player, 2001–02 NBA Rookie of the Year Award winner; 2006 FIBA W.C. MVP

- Marc Gasol (born 1985), player for Memphis Grizzlies (2008–2019) and Toronto Raptors (2019–present)

- Fernando Martín (1962–1989), Estudiantes, Real Madrid and Portland Trail Blazers player

- Jan Martín (born 1984), German-Israeli-Spanish basketball player

- Juan Carlos Navarro (born 1980), FC Barcelona and Memphis Grizzlies player

Boxing

[edit]- Pedro Carrasco (1943–2001), 1967 European Lightweight Champion; 1971 WBC's World Lightweight Champion

- Javier Castillejo (born 1968), two-time WBC World Jr. Middleweight Champion and one-time WBA Middleweight champion

MMA

[edit]- Ilia Topuria (Born Jan 21, 1997) - UFC Former featherweight world champion and current lightweight world champion.

Cycling

[edit]

- Federico Martín Bahamontes (1928–2023), 1959 Tour de France winner

- Alberto Contador (born 1982), three-time Tour de France (2007,2009,2010), 2008 Giro d'Italia, 2008 Vuelta a España winner

- Pedro Delgado (born 1960), 1988 Tour de France winner

- Óscar Freire (born 1976), three-time World Cycling Champion (1999, 2001, 2004)

- José Manuel Fuente (1945–1996), twice Vuelta a España winner (1972, 1974), second in Giro d'Italia (1972), third in Tour de France (1973)

- Roberto Heras (born 1974), three-time Vuelta a España winner (2000, 2003, 2004)

- Miguel Indurain (born 1964), gold medalist (1996 Olympics), 1995 World Time-Trial Champion, World Hour recordman (1994), five consecutive times Tour de France winner (1991–1995), twice Giro d'Italia winner (1992, 1993)

- Joan Llaneras (born 1969), gold medalist (2000 Olympics), silver medalist (2004 Olympics), seven-time World Points race or Madison Track Cycling Champion (1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2006, 2007)

- Luis Ocaña (1945–1994), 1973 Tour de France winner

- Abraham Olano (born 1970), 1995 World Cycling Champion and 1998 World Time-Trial Champion

- Óscar Pereiro (born 1977), 2006 Tour de France winner

- Samuel Sánchez (born 1978), Beijing 2008 Olympic Road Race Gold Medal

- Carlos Sastre (born 1975), 2008 Tour de France winner

- Joane Somarriba (born 1972), three-time Grande Boucle winner (2000, 2001, 2003)

- Guillermo Timoner (1926–2023), six-time World Motor paced Track Cycling Champion (1955, 1959, 1960, 1962, 1964, 1965)

Football (soccer)

[edit]

- Paulino Alcántara (1896-1964) Football legend and FC Barcelona player and manager

- Iker Casillas (born 1981), goalkeeper and Real Madrid; captain of Spain's team that won UEFA Euro 2008, the 2010 FIFA World Cup and Euro 2012

- Francisco Gento (1933–2022), Real Madrid player; winner of six UEFA Champions League

- Raúl González (born 1977), first player to reach 50 goals in UEFA Champions League

- Xavi Hernández (born 1980), midfielder and FC Barcelona player; UEFA Euro 2008 MVP

- Andrés Iniesta (born 1984), midfielder and FC Barcelona player; scored the winning goal at the 2010 FIFA World Cup Final; UEFA Euro 2012 MVP

- Alexia Putellas (born 1994), FC Barcelona Femení midfielder and two-time Ballon d'Or Féminin winner

- Fernando Torres (born 1984), striker and Chelsea player; scored the winning goal at the Euro 2008 Final; winner of Golden Boot at Euro 2012

- David Villa (born 1981), striker and FC Barcelona player; Spain's all-time top goalscorer

- Andoni Zubizarreta (born 1961), Spanish international

- Gerard Piqué (born 1987), central defender for FC Barcelona and Spain; part of the national team that won the 2010 FIFA World Cup and UEFA Euro 2012

- Pako Ayestarán (born 1963), football manager known for his roles at Liverpool F.C. (2005 UEFA Champions League winners) and Valencia CF

Golf

[edit]- Severiano Ballesteros (1957–2011), winner of five major championships

- Sergio García (born 1980), winner of a major championship

- Miguel Ángel Jiménez (born 1964), winner of 13 European Tour titles winner

- José María Olazábal (born 1966), winner of two major championships

- Jon Rahm (born 1994), the first Spanish golfer to win the US Open (2021) and winner of 12 other tournaments

Motor sports

[edit]

- Fernando Alonso (born 1981), 2005 and 2006 Formula One World Champion

- Jaime Alguersuari (born 1990), 2008 British Formula Three champion

- Álvaro Bautista (born 1984), motorcycle racing raider, 125cc champion of the World in 2006

- Carlos Checa (born 1972), GP motorcycle racing rider and Superbike World Champion in 2011

- Marc Coma (born 1976), won the Dakar Rally in 2006

- Àlex Crivillé (born 1970), 500cc GP motorcycle racing World Champion in 1999

- Marc Gené (born 1974), Formula One driver

- Jorge Lorenzo (born 1987), 2006 and 2007 GP motorcycle racing 250cc World Champion, 2010, 2012, and 2015 MotoGP World Champion

- Marc Márquez (born 1993), Grand Prix motorcycle road racer, and is the 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2017 Moto GP World Champion

- Jorge Martínez Aspar (born 1962), GP motorcycle racing rider, four-time World Champion

- Pedro Martínez de la Rosa (born 1971), Formula One driver

- Ángel Nieto (1947–2017), GP motorcycle racing rider, 12+1 times World Champion

- Daniel Pedrosa (born 1985), youngest GP motorcycle racing World Champion of 125cc and 250cc

- Carlos Sainz (born 1962), 1990 and 1992 World Rally Champion and 4-times Dakar Rally winner

- Carlos Sainz Jr. (born 1994), Formula One driver

Rugby union

[edit]- Oriol Ripol, professional rugby union player for Worcester Warriors; considered the greatest Spaniard to ever play the game

- Cédric Garcia, professional rugby player for Aviron Bayonnais

Tennis

[edit]

- Carlos Alcaraz (born 2003), 5 Grand Slam titles winner and former World Number 1

- Galo Blanco (born 1976), professional tennis player

- Sergi Bruguera (born 1971), 1993 and 1994 French Open Men's Singles Champion

- Àlex Corretja (born 1974), 1998 ATP Tour World Champion

- Albert Costa (born 1975), 2002 French Open Men's Singles Champion

- Juan Carlos Ferrero (born 1980), 2003 French Open Men's Singles Champion, former World Number 1

- Andrés Gimeno (1937–2019), 1972 French Open Men's Singles Champion

- Conchita Martínez (born 1972), 1994 Wimbledon Women's Singles Champion

- Carlos Moyá (born 1976), 1998 French Open Men's Singles Champion, former World Number 1

- Garbiñe Muguruza (born 1993), 2016 French Open and 2017 Wimbledon Women's Singles Champion

- Rafael Nadal (born 1986), former World Number 1, winner of 22 Grand Slam titles (including a record 14-times French Open titles), 2008 Olympics and 2016 Olympics gold medallist

- Manuel Orantes (born 1949), 1975 U.S. Open Men's Singles Champion

- Virginia Ruano Pascual (born 1973), eight Grand Slam Doubles titles winner

- Arantxa Sánchez Vicario (born 1971), ten Grand Slam titles winner (four singles, six doubles), former World Number 1

- Emilio Sánchez Vicario (born 1965), three Grand Slam Doubles titles winner

- Javier Sánchez Vicario, professional tennis player, brother of Aranxta

- Manuel Santana (1938–2021), 5 Grand Slam titles winner (four singles, one doubles)

- Fernando Verdasco Carmona (born 1983), professional tennis player

Triathlon

[edit]- Francisco Javier Gómez Noya (born 1983), triathlon silver (London 2012) medalist; four times ITU Triathlon world champion

Others

[edit]

- Georgina Rodríguez (born 1994), influencer

- Graciano Canteli, diplomat

- Charo (birth year debated), actress, singer, and flamenco guitarist, known for her TV appearances in the 1970s & 1980s

- Carlos Dominguez Cidon (1959–2009), chef

- Pilar Civeira, professor of medicine in Pamplona

- Charo Sádaba, professor of advertising in Pamplona

- María Josefa Cerrato Rodríguez (1897–1981), first woman veterinarian

- José Andrés (born 1969), chef

- Ferran Adrià (born 1962), chef

- Joaquín Cortés (born 1969), dancer

- Lola Greco (born 1964), dancer and choreographer

- Rosario Hernández Diéguez (1916–1936), newspaper hawker and trade unionist

- Juan March Ordinas (1880–1962), politician and businessman

- Francisco Mesa, electrical engineer

- Ana Morales (born 1982), flamenco dancer and choreographer

- Amancio Ortega Gaona (born 1936), entrepreneur

- Pepita de Oliva (1830–1871), dancer

- Ana María Pérez del Campo (born 1936), lawyer, feminist

- Juan Pujol, alias Garbo (1912–1988), double agent who played a key role in the success of D-Day towards the end of World War II

- Tamara Rojo (born 1974), prima ballerina of the London's Royal Ballet (since 2000); Prince of Asturias Award of Arts laureate (2005)

- Aurora Rodríguez Carballeira (1879–1955), woman who murdered her teenage daughter, conceived as a eugenics experiment

- Diego Salcedo (1575–1644), first Spaniard killed by Puerto Rican Taínos

- Elbira Zipitria (1906–1982), Spanish-Basque educator, promoter of the Basque language

- Edmond de Bries (1897 – c.1936 or 1950), Spanish female impersonator, actor, and cuplé singer

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Aróstegui Sáenz de Olamendi, Manuel - Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia". aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus (in Basque). Retrieved 7 May 2024.

External links

[edit]List of Spaniards

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Creative Arts

Visual artists and architects

Spanish visual artists and architects have profoundly influenced Western art through innovations in realism, expressionism, and organic forms, with key figures emerging during the Siglo de Oro and extending into the 20th century.[8]- El Greco (1541–1614): Greek-born painter who settled in Toledo, Spain, in 1577, known for elongated figures and dramatic lighting in works like The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586–1588), blending Mannerist and Byzantine styles.[9]

- Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664): Master of chiaroscuro and monastic portraiture, producing austere religious scenes such as The Defence of Cádiz Against the English (1634), emphasizing tactile realism in the Baroque tradition.[10]

- Diego Velázquez (1599–1660): Court painter to Philip IV, renowned for Las Meninas (1656), which innovated spatial depth and naturalistic depiction, marking a pinnacle of Spanish Golden Age portraiture.[11]

- Francisco Goya (1746–1828): Transitioned from Rococo to proto-Romanticism, creating The Third of May 1808 (1814) to depict the horrors of war with raw emotional intensity and social critique.[8]

- Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926): Architect of Catalan Modernisme, designed the Sagrada Família basilica (construction begun 1882, ongoing), integrating Gothic and Art Nouveau elements with nature-inspired organic curves.[12]

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973): Co-founder of Cubism, produced Guernica (1937) as a monumental anti-war mural using fragmented forms to convey the bombing's chaos.[13]

- Joan Miró (1893–1983): Surrealist painter and sculptor, featured dreamlike symbols in The Tilled Field (1923–1924), drawing from Catalan landscapes and subconscious imagery.[12]

- Salvador Dalí (1904–1989): Surrealist icon, depicted melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory (1931), exploring psychological time and the irrational through hyper-realistic technique.[13]

Writers and literary figures

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547–1616) authored Don Quixote, with Part I published in 1605 and Part II in 1615, pioneering the modern novel through its satire of chivalric romances and examination of idealism clashing with empirical reality, as the protagonist's delusions highlight causal disconnects between perception and worldly outcomes.[14][15] This narrative innovation, including self-referential elements and deep psychological insight into human folly, exerted lasting causal influence on literary realism and character interiority in Western fiction.[16] Félix Lope de Vega (1562–1635) composed over 1,500 plays and numerous poems, reforming Spanish drama by inventing the comedia nueva, a flexible structure prioritizing audience engagement over classical unities, which integrated themes of honor, love, and social causality to reflect 17th-century Spanish life.[17] His prolific output standardized vernacular theatrical forms, enabling broader linguistic experimentation and influencing subsequent playwrights by emphasizing plot-driven realism over rigid formalism.[18] Francisco de Quevedo (1580–1645) mastered conceptismo, a concise, intellectually dense style in poetry and prose, while producing theological treatises like La providencia that probed moral causality and human vanity through satirical visions critiquing societal decay.[19] His works, blending Stoic influences with sharp wit, advanced philosophical undertones in literature by causally linking individual vice to broader ethical decline, though his picaresque elements faced criticism for perpetuating cynical views of human nature unbound by empirical reform.[20] Miguel de Unamuno (1864–1936) explored existential tensions between faith, reason, and national identity in novels like Niebla (1914) and essays such as The Tragic Sense of Life (1913), prefiguring 20th-century existentialism by dissecting the causal futility of rationalism against innate human hunger for immortality and meaning.[21] His narrative innovations, including the "nivola" form where characters challenge authorial control, underscored philosophical realism in depicting internal conflicts driving personal and cultural crises, influencing later Spanish thought despite critiques of his idealism overriding verifiable historical data.[22] Federico García Lorca (1898–1936) blended surrealist poetry and folk-inspired plays like Blood Wedding (1933), drawing from Andalusian traditions to evoke primal passions and social constraints, with his Generation of '27 affiliation introducing European avant-garde elements to Spanish verse.[23] Lorca's lyrical intensity causally amplified themes of repressed desire versus communal norms, impacting global theater through symbolic depth, though his execution during the Spanish Civil War amplified romanticized views of his oeuvre at the expense of rigorous textual analysis.[24] Javier Marías (1951–2022) crafted intricate novels such as Your Face Tomorrow trilogy (2002–2007), weaving espionage with meditations on memory, deception, and moral causality, extending narrative time through digressive prose that mirrors real-world contingency over contrived plots.[25] His stylistic precision, prioritizing unspoken implications and historical veracity, revitalized contemporary Spanish fiction by critiquing ideological distortions in 20th-century narratives, earning acclaim for philosophical subtlety amid biases in post-Franco literary circles favoring overt political allegory.[26]Entertainment

Actors

Antonio Banderas, born José Antonio Domínguez Bandera on August 10, 1960, in Málaga, rose to international prominence through roles in Pedro Almodóvar's early films before transitioning to Hollywood, portraying Zorro in The Mask of Zorro (1998), which earned him a Golden Globe nomination and contributed to the film's $250 million global box office.[27] He received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor for his leading role in Pain and Glory (2019), directed by Almodóvar, highlighting his return to Spanish cinema with critical acclaim for embodying a semi-autobiographical director.[28] Banderas also debuted on Broadway in Nine (2003), earning a Tony Award nomination for his musical performance.[27] Javier Bardem, born March 1, 1969, in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his chilling depiction of assassin Anton Chigurh in the Coen brothers' No Country for Old Men (2007), a performance noted for its psychological intensity and philosophical undertones, grossing over $160 million worldwide.[29] Bardem earned additional Oscar nominations for Best Actor in Before Night Falls (2000) as Cuban poet Reinaldo Arenas and Biutiful (2010) as a terminally ill father navigating moral dilemmas.[29] His theatre work includes early stage appearances in Madrid productions, grounding his film career in classical training.[30] Penélope Cruz, born April 28, 1974, in Alcobendas, Madrid, achieved a historic milestone as the first Spanish actress to win an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role as volatile artist María Elena in Woody Allen's Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), praised for capturing fiery passion amid romantic entanglements.[31] Cruz's breakthrough in English-language films included Vanilla Sky (2001), but her Spanish origins shone in Almodóvar collaborations like Volver (2006), earning her a Goya Award and Cannes Best Actress honor.[31] She began in Spanish television and theatre, performing in youth-oriented series and stage musicals before international stardom.[32] Francisco Rabal, born March 8, 1926, in Águilas, Murcia, and deceased in 2001, starred in over 200 films, including Luis Buñuel's Viridiana (1961), which won the Palme d'Or at Cannes for its satirical critique of charity and class, showcasing Rabal's nuanced portrayal of a blind beggar.[32] Known for embodying marginalized figures during Franco-era cinema, he received a Honorary Goya Award in 1998 for lifetime achievement in Spanish film.[33] Fernando Rey, born September 20, 1917, in A Coruña, and deceased in 1994, appeared in more than 200 films across Europe, notably as the corrupt official in Buñuel's The French Connection (1971), earning a BAFTA nomination, and in Viridiana (1961) as the estate owner.[32] His theatre career spanned classical Spanish works, contributing to post-war cultural revival, with international recognition for bridging arthouse and mainstream cinema.[34] Luis Tosar, born October 13, 1971, in Cospeito, Lugo, gained acclaim for intense roles like the kidnapper in Take My Eyes (2003), winning a Goya Award for Best Actor, and the boxer in Celda 211 (2009), which secured another Goya and European Film Award.[33] His television work includes the series El Reino, but his filmography emphasizes gritty realism in Spanish thrillers, with over 70 credits reflecting endurance in domestic and international markets.[35]Film directors

Spanish film directors have shaped global cinema through surrealist experimentation, allegorical critiques of authoritarianism, and post-dictatorship explorations of identity and desire, often overcoming Franco-era censorship (1939–1975) via symbolic narratives that evaded official scrutiny.[36][37] Directors like Luis Buñuel pioneered irrationalist techniques in the early 20th century, while later figures such as Carlos Saura documented societal tensions under dictatorship, and Pedro Almodóvar's post-1975 works achieved commercial success amid thematic boldness. Luis Buñuel (1900–1983), born in Calanda, Aragon, directed landmark surrealist films including Un Chien Andalou (1929), co-scripted with Salvador Dalí, featuring shocking imagery like eye-slicing to challenge bourgeois norms and rationality.[38] His Spanish productions, such as Viridiana (1961), satirized Catholic hypocrisy and feudalism, winning the Cannes Palme d'Or but prompting Vatican condemnation and Francoist bans for perceived blasphemy.[38] Buñuel's oeuvre influenced subsequent filmmakers by prioritizing subconscious drives over linear plots, though his later Mexican and French works diluted direct ties to Spanish production.[39] Carlos Saura (1932–2023), from Madrid, navigated Francoist censorship with introspective dramas like Cría Cuervos (1976), which allegorically addressed repression and won the Cannes Jury Prize, reflecting empirical observations of psychological scars from civil war and dictatorship.[40] His flamenco trilogy—Blood Wedding (1981), Carmen (1983), and El Amor Brujo (1986)—blended dance with narrative to revive cultural traditions suppressed under regime orthodoxy, earning Cannes awards and an Oscar nomination for Carmen.[41] Saura's 40+ films secured four Oscar nominations and multiple Berlin Silver Bears, underscoring his role in transitioning Spanish cinema toward uncensored realism post-1975.[40][42] Pedro Almodóvar (born 1949 in Calzada de Calatrava), emblematic of the post-Franco movida madrileña cultural explosion, directed melodramas like All About My Mother (1999), which grossed $67 million worldwide and won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2000 for its layered portrayal of grief and performance.[43][44] His 28 directed features aggregate over $425 million in global box office, with stylistic hallmarks including vibrant palettes and frank depictions of sexuality that initially provoked conservative backlash but garnered five Goyas and Cannes Best Director for Volver (2006).[43][44] Almodóvar's influences trace to Buñuel's irreverence, adapted to critique lingering machismo and familial dysfunction in democratized Spain.[45] Alejandro Amenábar (born 1972 in Santiago, Chile, but raised in Madrid from infancy), debuted with thriller Thesis (1996), winning seven Goya Awards including Best Director for its tense examination of snuff films and media ethics.[46] His The Others (2001) achieved $209 million box office on psychological horror, starring Nicole Kidman, while The Sea Inside (2004) earned the 2005 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, based on Ramón Sampedro's real euthanasia case, highlighting tensions between autonomy and institutional control.[47] Amenábar's genre versatility, from sci-fi in Open Your Eyes (1997) to historical drama in While at War (2019), reflects Spanish cinema's post-1990s internationalization, with 14 Goyas underscoring critical and commercial viability.[46][48] Other contributors include Víctor Erice (born 1940), whose The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) subtly evoked Francoist isolation through a child's lens, earning San Sebastián Golden Seashell amid regime-end pressures.[49] These directors' outputs, measured by awards (e.g., 60+ international for Amenábar) and revenues, demonstrate causal links between historical constraints and innovative storytelling, prioritizing empirical human conditions over ideological conformity.[48]Models and fashion figures

Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972), born in Getaria, Spain, established his haute couture house in Paris in 1937, pioneering architectural silhouettes such as the balloon skirt and baby doll dress that redefined women's fashion in the mid-20th century.[50] His designs drew from Spanish cultural elements like matador suits and religious vestments, emphasizing volume, structure, and technical innovation over fleeting trends, which influenced contemporaries like Christian Dior, who called him "the master of us all."[51] Balenciaga's atelier produced over 20,000 custom garments until closing in 1968, prioritizing craftsmanship amid post-World War II fabric shortages.[52] Francisco Rabaneda y Cuervo, professionally known as Paco Rabanne (1934–2016), born in San Sebastián, Spain, revolutionized ready-to-wear with metallic and plastic-based collections after relocating to France following the Spanish Civil War.[53] His 1966 debut of chainmail dresses and space-age materials challenged traditional textiles, achieving commercial success through licensing deals that expanded his brand's valuation into billions by the 21st century.[54] Manolo Blahnik (born 1942 in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain) has dominated luxury footwear since launching his label in London in 1970, with signature pointed-toe pumps worn by figures like Diana, Princess of Wales, generating annual revenues exceeding €100 million through over 100 global boutiques.[53] His designs emphasize artisanal construction and exaggerated forms, sustaining influence despite criticisms of high pricing amid fast fashion's rise.[55] Judit Mascó (born 1969 in Barcelona) emerged as a top model in the 1980s, securing campaigns for brands like Larios and featuring in calendars that sold millions of copies from 1996 to 2004, while hosting Spain's Supermodel TV series in 2006–2007.[56] Her 30-year career highlighted endurance in an industry favoring youth, with over 1,600 documented appearances emphasizing natural aging over retouched ideals.[57] Esther Cañadas (born 1971 in Alicante) gained international prominence in the 1990s through runway shows for Versace and Victoria's Secret, amassing a portfolio of editorial covers that underscored Spain's contribution to supermodel diversity amid globalization.[58] Jon Kortajarena (born 1985 in Bilbao), a leading male model since 2003, has fronted campaigns for Tom Ford and Yves Saint Laurent, walking over 500 shows and boosting male fashion's commercial viability with earnings from endorsements exceeding multimillion-dollar figures annually.[58]Music

Classical composers

Tomás Luis de Victoria (c. 1548–1611) stands as the preeminent Spanish composer of the Renaissance, renowned for his sacred polyphonic works including over 20 masses and numerous motets that exemplify advanced counterpoint techniques derived from Flemish influences adapted to Spanish liturgical traditions.[59] His Officium Defunctorum (1605), composed for the funeral of Empress Maria, remains a cornerstone of choral repertoire, with recordings by ensembles like The Sixteen highlighting its somber modal harmonies and structural innovations in text expression.[60] Isaac Albéniz (1860–1909) pioneered nationalist piano composition, incorporating Spanish folk rhythms and regional dances into virtuoso suites, most notably Iberia (1906–1909), a four-book collection evoking Andalusian and Catalan landscapes through impressionistic harmonies and idiomatic guitar-inspired techniques.[61] Despite critiques of its technical demands limiting early performances, Iberia has endured, with orchestral transcriptions by conductors like Enrique Arbós facilitating broader concert hall adoption and over 100 recordings by 2020.[62] Enrique Granados (1867–1916) advanced Spanish musical nationalism via piano works infused with folk elements, such as the Goyescas suite (1911), which draws on Goya's paintings for dramatic, lyrical structures blending salon intimacy with symphonic depth.[63] His chamber adaptations, including string quartets, reveal counterpoint rooted in 19th-century Romanticism, though some contemporaries noted their sentimental excess compared to stricter classical forms; nonetheless, Goyescas has seen frequent revivals, with 50 major recordings since 1950.[64] Manuel de Falla (1876–1946) fused Andalusian flamenco idioms with orchestral innovation in ballets like El amor brujo (1915), featuring the iconic "Ritual Fire Dance" that employs modal scales and percussive rhythms for evocative storytelling.[65] His chamber works, such as the Concerto for Harpsichord (1926), demonstrate neoclassical restraint influenced by Stravinsky, yet faced postwar critiques for perceived conservatism amid avant-garde shifts; performances persist globally, with over 200 orchestral renditions documented by 2020.[66] Joaquín Rodrigo (1901–1999), blind from age three, composed guitar-centric orchestral pieces like Concierto de Aranjuez (1939), which integrates folk-inspired themes with lush impressionism, achieving over 1,000 recordings and annual festival performances emphasizing its adagio's emotional resonance.[67] While praised for accessibility, detractors have highlighted formulaic repetitions in his oeuvre, yet his structural innovations in concerto form, drawing on Spanish guitar traditions, solidified his legacy in 20th-century repertoire.[68]Opera singers

Montserrat Caballé (1933–2018), a Catalan soprano renowned for her mastery of bel canto repertoire, debuted internationally in 1965 at Carnegie Hall substituting for Marilyn Horne in Donizetti's La Favorita, showcasing her exceptional vocal range spanning three octaves and crystalline high notes.[69] She performed nearly 100 roles across Italian, German, and French operas, including collaborations with Luciano Pavarotti in productions like Massenet's Le Cid at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1970s, and recorded over 80 operatic titles, earning Grammy Awards for interpretations emphasizing lyrical precision and endurance in roles like Norma and Lucrezia Borgia.[70] Caballé's technique highlighted flawless trills and dynamic control, though later career vocal health concerns arose from pushing dramatic roles beyond her lyric strengths.[71] Plácido Domingo (born 1941), born in Madrid and initially a tenor before transitioning to baritone in 2010 to preserve vocal longevity, has sung over 150 roles in more than 4,000 performances at venues including La Scala and the Zarzuela Theatre, excelling in Verdi and Puccini works like Otello (debut 1974 at New York City Opera) and Simon Boccanegra.[72] His versatility extended to French, German, and Spanish zarzuela repertoire, with recordings of over 100 complete operas demonstrating robust endurance and interpretive depth in dramatic narratives.[73] This shift addressed age-related strain on his tenor register, allowing sustained engagements into his 80s while maintaining power in baritone lines.[74] Alfredo Kraus (1927–1999), a Canary Islands-born tenor specializing in bel canto, performed 43 operas including Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia and Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, noted for elegant phrasing, firm tone, and breath control that sustained a career from the 1950s to the 1990s without major vocal decline.[75] He debuted at La Scala in 1956 as Almaviva and recorded Spanish composers' works, emphasizing stylistic purity over volume in lyric roles at houses like the Lyric Opera of Chicago.[76] Victoria de los Ángeles (1923–2005), a lyric soprano from Barcelona, debuted at the Liceu in 1944 as Mimi in La Bohème and gained acclaim for over 35 leading roles in operas like Carmen and Madama Butterfly, with a timbre suited to Spanish vocal music and recitals interpreting librettos with emotional realism.[77] Her Paris Opera debut in 1949 as Marguerite in Faust led to Metropolitan Opera engagements from 1951, where she prioritized vocal health through selective repertoire, avoiding heavier dramatic parts.[78] José Carreras (born 1946), a Catalan tenor, rose to prominence in the 1970s with roles in Puccini's La Bohème and Verdi's Un ballo in maschera at La Scala and Covent Garden, performing with technical agility in bel canto and verismo styles before health challenges from leukemia in 1988 prompted a refined, lighter approach post-recovery.[79] He contributed to The Three Tenors concerts, highlighting interpretive focus on character psychology in over 60 operatic roles.[80] Teresa Berganza (1933–2022), a mezzo-soprano from Madrid, excelled in Mozart and Rossini operas like Le nozze di Figaro and La Cenerentola, debuting at the Aix-en-Provence Festival in 1957 and performing at the Metropolitan Opera with precise coloratura and dramatic presence in trouser roles.[80] Her career emphasized bel canto agility and textual clarity, recording extensively while maintaining vocal consistency into advanced age.[81]Popular singers and musicians